Abstract

Background

Food insecurity is a public health concern that affects health and quality of life, but its association with cardiometabolic risk is not well established. Thus, this systematic review evaluated the association between food insecurity and cardiometabolic risk factors in adults and the elderly.

Methods

Search was conducted according to the PRISMA protocol using Scielo, LILACS and PubMed databases. We included original articles published in Portuguese, English, and Spanish, which assessed the association between food insecurity and cardiometabolic risk factors in adults and the elderly. The search identified 877 articles but only 11 were included in the review.

Results

Food insecurity was directly associated with cardiometabolic risk (excess weight, hypertension, dyslipidemias, diabetes, and stress) after adjusting for interfering factors. A limitation of the cross-sectional study design is that the cause-effect relation between food insecurity and cardiometabolic risk cannot be established.

Conclusions

We conclude that food insecurity has a direct relationship with cardiometabolic risk factors, especially excess weight, hypertension, and dyslipidemias. The identification of food insecurity as health problems can contribute to the implementation of efficient public policies for the prevention and control of chronic diseases.

Protocol registration

This review was registered on PROSPERO-International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews – CRD4201911549.

Food security is defined as the physical and economic access to safe and nutritious food that meets individual and household needs for the promotion and maintenance of health. Failure to satisfy the Human Right to Adequate Food and Food Sovereignty results in food insecurity. In 2017, 10.9% of the world's population was food insecure and concomitantly, the prevalence of obesity increased from 11.7% in 2012 to 13.2% in 2016 [1].

A direct measure of food insecurity through perception was first developed by researchers of Cornell University [2]. This method was later applied in the US census [3]. The Household Food Security Survey of the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) measures the possibility of running out of food before affording to buy more. This tool also considers severe food deprivation, where adults and children go all day without eating [4]. Food insecurity can be measured indirectly through indicators such as anthropometry [5], food consumption [6], food expenditure [7] and imposition of food patterns that do not respect cultural diversity [8].

Food insecurity has significant impact on nutritional status, food consumption, and food access. Furthermore, studies have shown that food insecure individuals tend to consume less whole grains and more refined carbohydrates and sodium, increasing the risk of morbidity and mortality [9,10]. Thus, food insecurity could be related to risk of developing chronic cardiometabolic diseases, such as obesity, diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemias [9,11-13].

Overall, the present systematic review aimed to evaluate the association between food insecurity and cardiometabolic risk factors in adults and the elderly.

METHODOLOGY

The guiding question employed was “Is food insecurity directly associated with cardiometabolic risk factors in adults and the elderly?”. The question is based on increasing prevalence of food insecurity worldwide at the same time that chronic diseases such as obesity and related cardiometabolic risk factors [1].

Protocol and registration

This systematic review was conducted according to the PRISMA protocol-Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis [14] and was registered on PROSPERO-International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews-CRD42019115493.

Inclusion criteria

We included original articles published in Portuguese, English, and Spanish, which assessed the association between food insecurity and cardiometabolic risk factors in adults and the elderly. Only articles indexed in Scielo, LILACS and PubMed databases were considered. Also, no restriction was placed on the year of publication. The references of the articles were searched, and other articles not identified in the initial search were included (reverse citation search).

Search, selection and evaluation of articles

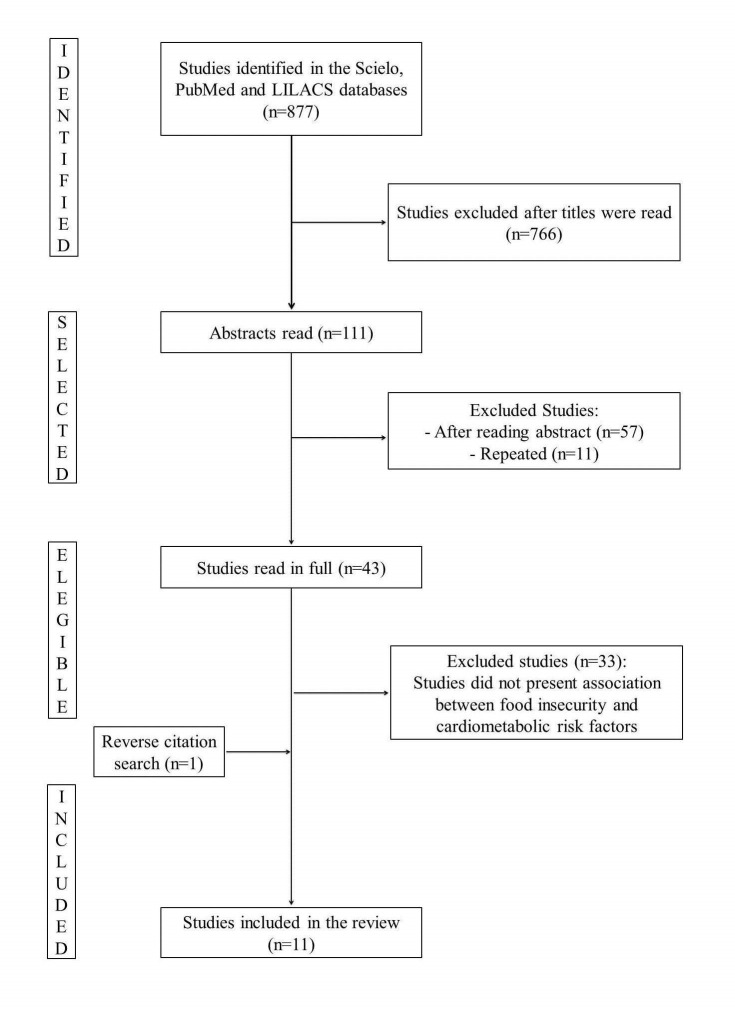

The search terms used were 'food security', 'food insecurity', 'diabetes', 'hypertension', 'metabolic syndrome', 'dyslipidemia', 'stress', 'waist circumference' and ' excess weight'. For the search, we used a combination of 'food security' OR ‘food insecurity’ AND other terms, to refine our search to the topic of interest, the relationship between food insecurity and cardiometabolic risk. The search produced 877 articles, however 766 were excluded after reading the titles. The abstracts of the remaining 111 articles were read. Then, 43 studies were selected for further reading. After reading the articles in full, 10 articles were selected. An additional article was selected after a reverse citation search, totaling 11 articles (Figure 1). The studies were evaluated by STROBE - Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology [15].

Figure 1.

Flowchart of article selection process.

RESULTS

We identified 11 cross-sectional studies published between 2006 and 2017, conducted in the United States [16-24], Mexico [25] and Malaysia [26]. In relation to study population, 54.5% (n = 6) of the studies were conducted with adults only [17-19,21,24,26], 36.4% (n = 4) with both adults and the elderly [16,20,22,23], and 9.1% (n = 1) with only the elderly [25].

The majority of the studies, 64% (n = 7), assessed food insecurity by the Household Food Security Survey (USDA) [16-19,22,24,26]. However, the studies presented a wide range of food insecurity assessment tools (Table 1).

Table 1.

Stratification of food insecurity according to the reviewed studies

| Author (year) | Stratification |

|---|---|

| Holben, Pheley (2006) [16] |

−* |

| Seligman et al (2007) [17] |

FS – No affirmative answer |

| Mild FI – 1 to 5 affirmative answers | |

| Severe FI – 6 to 10 affirmative answers | |

| Jilcott et al (2011) [18]; Berkowitz et al (2013; 2017) [19,24] |

FS – 0 to 2 affirmative answers |

| FI – 3 or more affirmative answers | |

| Pérez-Escamilla et al (2014) [25] |

FS – 0 |

| Mild FI – 1 to 3 points | |

| Moderate FI – 4 to 6 points | |

| Severe FI – 7 to 8 points | |

| Shariff et al (2014) [26] |

FS – 0 |

| FI – 1 to 8 points | |

| Irving, Njai, Siegel (2014) [20] |

FS – Answer was rarely or never |

| FI – Answer was always, usually or sometimes | |

| Moreno et al (2015) [22] |

FS – 0 to 1 affirmative answer |

| FI – 2 affirmative answers | |

| Shin et al (2015) [21]; Saiz Júnior et al (2016) [23] | An affirmative response to any of the FI assessment questions |

FS – food security, FI – food insecurity

*Stratification method was not disclosed.

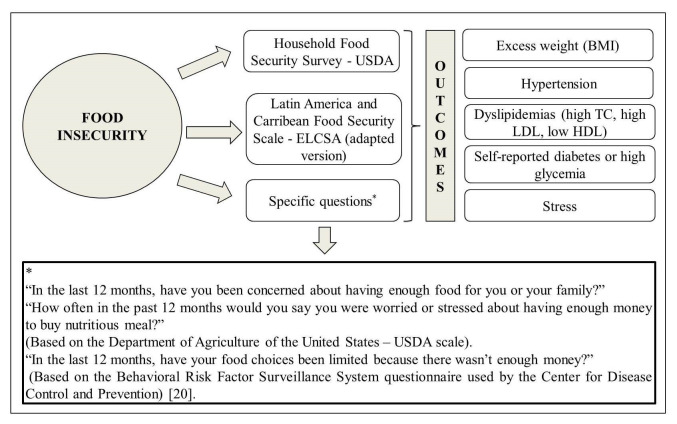

The studies evaluated the cardiometabolic risk through body weight excess according to the body mass index (BMI), high blood pressure (BP), high total cholesterol (TC), high LDL, low HDL, presence of diabetes or stress. In 73% (n = 8) of the articles, cardiometabolic risk was assessed by excess body weight and 64% (n = 7) by high BP. Food insecurity was directly associated with all evaluated cardiometabolic risk factors evaluated (Figure 2). The associations were maintained after adjusting for sociodemographic, economic and lifestyle characteristics. In contrast, three studies showed food insecurity was inversely associated with cardiometabolic risk factors, specifically, increased BP and LDL, metabolic syndrome and obesity in women. 22; 23; 26 The detailed results of the studies are described in Table 2.

Figure 2.

Graphical representation of the instruments used to evaluate food security and clinical outcomes in studies with adults and the elderly, 2018. BMI – body mass index, TC – total cholesterol, HDL – high density lipoprotein, LDL – low density lipoprotein

Table 2.

Evaluation of the association between food insecurity and cardiometabolic risk in adults and the elderly

| Author/Year |

Place/Sample |

Evaluation method |

Association between FI and CRM |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

FI |

CRM |

|||

| Holben, Pheley (2006) [16] |

United States, n = 2580 |

Household Food Security Survey – USDA |

-Excess weight (BMI) |

Obesity:>prevalence among insecure individuals |

| -High diastolic BP |

FI: Directly associated with o excess weight (BMI) in women |

|||

| -High TC | ||||

| -Self-reported Diabetes | ||||

|

Seligman et al (2007) [17] |

United States, n = 4423 |

Household Food Security Survey – USDA |

-Excess weight (BMI) |

Women with FI women:>occurrence of obesity in secure women or severe FI |

| -Self-reported diabetes |

Participants with severe FI>probability of having diabetes than food secure participants, after adjusting for socio-demographic factors, level of physical activity and BMI |

|||

| -High WC | ||||

| Jilcott et al (2011) [18] |

United States, n = 202 |

Household Food Security Survey – USDA |

-Excess weight (BMI) |

FI: Directly associated with excess weight (BMI) and perceived stress |

| -Stress | ||||

|

Berkowitz et al (2013) [19] |

United States, n = 2557 |

Household Food Security Survey – USDA |

-High BP |

FI: Directly associated with high glycemia and cholesterolemia, after adjusting for sociodemographic factors, smoking, BMI, diabetes duration, statin use and being under treatment. |

| -High cholesterol | ||||

| -Diabetes | ||||

| Irving, Njai, Siegel (2014) [20] |

United States, n = 58 677 |

Question: |

-High BP |

FI: directly associated with hypertension, after adjusting for age, sex, race/ethnicity, level of education and poverty, health insurance coverage, marital status, and smoking. |

| “How often in the past 12 months would you say you were worried or stressed about having enough money to buy nutritious meals?” | ||||

| Pérez-Escamilla et al (2014) [25] |

Mexico, n = 32 320 |

Adopted version of the Latin America and Caribbean Food Security Scale |

-High BP |

FI mild, moderate and severe: directly associated with the presence of diabetes and hypertension in women |

| -Diabetes | ||||

| Shariff et al (2014) [26] |

Malaysia, n = 625 |

Household Food Security Survey – USDA |

-Excess weight (BMI) |

FI: Inversely associated with increased LDL, metabolic syndrome and obesity in women |

| -High BP | ||||

| -High TC, low HDL, high LDL | ||||

| -High WC | ||||

| -Metabolic syndrome (presence of 3 or more factors) | ||||

|

Moreno et al (2015) [22] |

United States, n = 250 |

Household Food Security Survey – USDA |

-Excess weight (BMI) |

FI: associated with BP and LDL |

| -High BP | ||||

| -High LDL | ||||

| -Diabetes | ||||

| Shin et al (2015) [21] |

United States, n = 1663 |

Questions |

-Excess weight (BMI) |

FI: Associated directly with low HDL among women, after adjusting for age, race, level of education, family income, smoking, alcohol intake and physical activity |

| -“In the last 12 months, have you been concerned about having enough food for you or your family?” | ||||

| -“In the last 12 months, have your food choices been limited because there wasn’t enough money?” |

-Dyslipidemia (high TC or low HDL) |

|||

| Saiz Júnior et al (2016) [23] |

United States, n = 2935 |

Question: |

-Excess weight (BMI) |

FI: Inversely associated with hypertension, TC and BMI |

| - “In the last 12 months, have you been concerned about having enough food for you or your family?” |

-High BP |

|||

| -High TC | ||||

| Berkowitz et al (2017) [24] | United States, n = 21 196 | Household Food Security Survey – USDA | -Excess weight (BMI) |

FI: directly associated with hypertension, diabetes, obesity, and LDL |

| -High BP | ||||

| -High LDL | ||||

| -Diabetes | ||||

FI – food insecurity, CRM – cardiometabolic risk markers, USDA – US Department of Agriculture, BMI – body mass index, BP – blood pressure, TC – total cholesterol, HDL – high density lipoprotein, LDL – low density lipoprotein, WC – waist circumference, ELCSA – Latin America and Caribbean Food Security Scale

The selected articles presented a median score of 18 points as regards quality (minimum = 14, maximum = 21).

DISCUSSION

Most of the studies presented association between food insecurity and cardiometabolic risk factors in adults and the elderly, regardless of interfering factors. In this context, some relevant issues can be discussed.

First, studies on the physical and economic access to food should not focus solely on identifying the absence of food but rather the inadequate access to the same, which may be related to chronic clinical outcomes. In fact, the analysis of socioeconomic factors can elucidate clinical outcomes since its deprivation can promote inadequate food consumption [27,28]. The consumption of high calorie foods has been shown to increase the risk of diabetes and arterial hypertension [29,30].

On the other hand, prolonged food deprivation may cause an inverse association between food insecurity and cardiometabolic risk factors because individuals in this situation lack food diversity and tend to reduce their portion size [31-33]. In turn, medical expenses related to cardiometabolic diseases can restrict the quantity and quality of healthy food consumed, which in turn increases the risk of food insecurity, when resources are limited. Accordingly, food insecurity and cardiometabolic risk can form a vicious cycle [34]. Moreover, stress increases cortisol concentrations, contributing to an increase in adiposity, possibly leading to obesity and altered blood pressure [29,30]. It is important to mention that similar results have been found in children and adolescents.

The second point throws light on the instruments used for the assessment of food insecurity. Food insecurity can be measured by household food availability, dietary intake, anthropometric, socioeconomic, biochemical and clinical data. However, food insecurity scales based on perception are mostly utilized because they allow a direct classification and stratification of severity (mild, moderate, and severe) [35,36]. The American scale, considered “gold standard”, and the Latin America and Caribbean Food Security Scale, validated for the Mexican population, are instruments which provide information on the distribution, causes and consequences of food insecurity, most importantly, the magnitude of the same based on reliable and validated indicators [37].

In addition, associations established depend on the stratification and psychometric analyses of the answers and guiding questions. Furthermore, scales are direct indicators of food insecurity, thus can be used as monitoring tools. They also facilitate the identification of vulnerable groups [37]. However, scales only measure the perception of insecurity, leaving out the nutritional aspect of food insecurity.

In this sense, the evaluation of food insecurity considering the nutritional status of individuals could clarify controversial values reported in some studies [33,37,38]. On the other hand, scales predict household food insecurity than individual food insecurity. In this sense, future studies should focus on the measurement of individual food insecurity based on the stratification of socioeconomic factors since they can be contributing factors.

Regarding anthropometric markers used in the studies, we highlight BMI and waist circumference as simple, fast and inexpensive methods for assessing cardiometabolic risk. Moreover, these markers have a good association with adiposity.

We would like to discuss about age-groups distribution of the study samples. In fact, we adopted as selection criterion to search studies with adults and, or, elderly, based on the lack of global information addressing the relationship between food insecurity and cardiometabolic risk in these age-groups as well as on the hypothesis this would be more prevalent among older persons. In this sense, we found greater number of studies with adults, followed by studies with two age-groups and studies participating only elderly. However, the study outcomes were similar, with positive association between food insecurity and cardiometabolic risk factors, regardless of age sample. Our review indicates food insecurity as relevant factor in these two age-groups on developing chronic diseases, at least at the moment.

The strengths of this review are the use of secondary data from representative samples, and the measurement of food insecurity using “gold standard” tool, in its original or adapted version, by included studies. As limitation, all the included studies had cross-sectional design, so the cause-effect relation between food insecurity and cardiometabolic risk cannot be established. In addition, the scales do not allow an assessment of the nutritional aspect and the assessment of the situation of food insecurity is at the household level, while the cardiometabolic risk factors were assessed at the individual level. Therefore, longitudinal studies in humans that consider the nutritional dimension and the individual aspect would allow establishing a causal relationship between food insecurity and cardiometabolic risk.

CONCLUSIONS

Food insecurity has a direct relationship with cardiometabolic risk factors, especially excess weight, hypertension, and dyslipidemias, indicating the need to assess individual and household food insecurity. The identification of food insecurity as health problems can contribute to the implementation of efficient public policies for the prevention and control of chronic diseases.

Acknowledgment

We thank CAPES Foundation (Ministry of Education, Brazil, Financial Code 001), Minas Gerais State Research Foundation (FAPEMIG, State of Minas Gerais, Brazil), and the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq, Ministry of Science and Technology, Brazil) for supporting the related projects.

Footnotes

Funding: There is no funding to be declared.

Authorship contributions: Conception: ESM, SOL, SPA, HHMH, SEP. Realized the literature search, selection, extraction and analyze the data: ESM, SOL, SPA. Writing - preparation: ESM, SOL, SAP. Writing – review and editing: ESM, SOL, SAP, HHMH, RCGA, SEP. Provided methodological advice and critically revised the manuscript: HHMH, RCGA, SEP.

Competing interests: The authors completed the ICMJE Unified Competing Interest form (available upon request from the corresponding author), and declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.FAO. FIDA, UNICEF, PMA, OMS. El estado de la seguridad alimentaria y la nutrición en el mundo: Fomentando la resiliencia climática en aras de la seguridad alimentaria y la nutrición. Roma: FAO; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Radimer KL, Olson CM, Greene JC, Campbell CC, Habicht JP.Understanding hunger and developing indicators to assess it in women and children. J Nutr Educ. 1992;24:36S-44S. 10.1016/S0022-3182(12)80137-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bickel G, Nord M, Price C, Hamilton W, Cook J. Measuring food security in the United States: guide to measuring household food security. Alexandria: Office of Analysis, Nutrition, and Evaluation, U. S. Department of Agriculture; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nord M, Jemison K, Bickel G.Measuring food security in the United States: Prevalence of food insecurity and hunger, by state, 1996-1998. Food Assist Nutr Res Report. 1999;2:1-20. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lang RMF, Almeida CCB, Taddei JAAC.Food and nutrition safety of children under two years of age in families of landless rural workers. Cien Saude Colet. 2011;16:3111-8. 10.1590/S1413-81232011000800011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Costa LV, Silva MMC, Braga MJ, Lírio VS.Factors associated with Brazilian food security in households in 2009. Econ Soc. 2014;23:373-94. 10.1590/S0104-06182014000200004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Costa LV, Gomes MFM, Lírio VS, Braga MJ.Agricultural productivity and food security of households in Brazilian metropolitan regions. Rev Econ Sociol Rural. 2013;51:661-80. 10.1590/S0103-20032013000400003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.CONSEA. Principles and guidelines for a food and nutrition security policy. Reference texts from the II National Conference on Food and Nutrition Security. Brasília, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morais DC, Dutra LV, Franceschini SCC, Priore SE.Food insecurity and anthropometric, dietary and social indicators in Brazilian studies: a systematic review. Cien Sauda Colet. 2014;19:1475-88. 10.1590/1413-81232014195.13012013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marín-León L, Segal-Corrêa AM, Panigassi G, Maranha LK, Sampaio MFA, Pérez-Escamilla R.Food insecurity perception in families with elderly in Campinas, São Paulo, Brazil. Cad Saude Publica. 2005;21:1433-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berkowitz SA, Fabreau GE.Food insecurity: What is the clinician’s role? CMAJ. 2015;187:1031-2. 10.1503/cmaj.150644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vasconcelos SML, Torres NCP, Silva PMC, et al. Food insecurity in households of patients with hypertension and diabetes. Int J Cardiovasc Sci. 2015;28:114-21. 10.5935/2359-4802.20150014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tait CA, L’Abbe´ MR, Smith PM, Rosella LC.The association between food insecurity and incident type 2 diabetes in Canada: A population-based cohort study. PLoS One. 2018;13:e195962. 10.1371/journal.pone.0195962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Galvão TF, Pansani TSA, Harrad D.Main items for reporting Systematic reviews and meta-analyzes: The PRISMA recommendation. Epidemiol Serv Saude. 2015;24:335-42. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Malta M, Cardoso LO, Bastos FI, Magnanini MMF, Silva CMFP.STROBE initiative: guidelines on reporting observational studies. Rev Saude Publica. 2010;44:559-65. 10.1590/S0034-89102010000300021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holben DH, Pheley AM.Diabetes risk and obesity in food insecure households in rural Appalachian Ohio. Prev Chronic Dis. 2006;3:A82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seligman HK, Bindman AB, Vittinghoff E, Kanaya AM, Kushel MB.Food insecurity is associated with diabetes mellitus: Results from the National Health Examination and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 1999–2002. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:1018-23. 10.1007/s11606-007-0192-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jilcott SB, Wall-Bassett ED, Burke SC, Moore JB.Associations between food insecurity, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits, and body mass index among adult females. J Am Diet Assoc. 2011;111:1741-5. 10.1016/j.jada.2011.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berkowitz SA, Bagget TP, Wxler DJ, Huskey KW, Wee CC.Food insecurity and metabolic control among U.S. Adults with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:3093-9. 10.2337/dc13-0570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Irving SM, Njai RS, Siegel PZ.Food insecurity and self-reported hypertension among hispanic, black, and white adults in 12 states, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2009. Prev Chronic Dis. 2014;11:E161. 10.5888/pcd11.140190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shin JI, Batista LE, Batista LE, Malecki KC, Nieto FJ.Food insecurity and dyslipidemia in a representative population-based sample in the US. Prev Med. 2015;77:186-90. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.05.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moreno G, Morales LS, Isiordia M, Jaimes FN, Tseng C, Noguera C, et al. Latinos with diabetes and food insecurity in an agricultural community. Med Care. 2015;53:423-9. 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saiz AM, Aul AM, Malecki KM, Bersch AJ, Bergmans RS, LeCaire TJ, et al. Food insecurity and cardiovascular health: findings from a statewide population health survey in Wisconsin. Prev Med. 2016;93:1-6. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.09.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berkowitz SA, Berkowitz TSZ, Meigs JB, Wexler DJ.Trends in food insecurity for adults with cardiometabolic disease in the United States: 2005-2012. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0179172. 10.1371/journal.pone.0179172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pérez-Scamilla R, Villalpando S, Shamah-Levy T, Mendez-Gomez Humaran I.Household food insecurity, diabetes and hypertension among Mexican adults: results from Ensanut 2012. Salud Publica Mex. 2014;56:62-70. 10.21149/spm.v56s1.5167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shariff ZM, Sulaiman N, Jalil RA, Yen WC, Yaw YH, Taib MN, et al. Food insecurity and the metabolic syndrome among women from low income communities in Malaysia. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2014;23:138-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Álvarez-Castaño LS, Goez-Rueda JD, Carreño-Aguirre C.Factores sociales y económicos asociados a la obesidad: los efectos de la inequidad y de la pobreza. Rev Gerenc Polit Salud. 2012;11:98-110. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Monteiro CA, Moubarac JC, Canhão G, Ng SW, Popklin B.Ultra-processed products are becoming dominant in the global food system. Obes Rev. 2013;14:21-8. 10.1111/obr.12107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hamelin AM, Beaudry M, Habicht JP.Characterization of household food insecurity in Québec: food and feelings. Soc Sci Med. 2002;54:119-32. 10.1016/S0277-9536(01)00013-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adrogué HJ, Madias NE.Sodium and potassium in the pathogenesis of hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1966-78. 10.1056/NEJMra064486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Champagne CM, Casey PH, Connell CL, Stuff JE, Gossett JM, Harsha DW, et al. Poverty and food intake in rural America: diet quality is lower in food insecure adults in the Mississippi delta. J Am Diet Assoc. 2007;107:1886-94. 10.1016/j.jada.2007.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kirkpatrick SI, Tarasuk V.Food insecurity is associated with nutrient inadequacies among Canadian adults and adolescents. J Nutr. 2008;138:604-12. 10.1093/jn/138.3.604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kepple AW, Segall-Corrêa AM.Conceptualizing and measuring food and nutrition security. Cien Saude Colet. 2011;16:187-99. 10.1590/S1413-81232011000100022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rocha NP, Milagres LC, Novaes JF, Franceschini SCC.Association between food and nutrition insecurity with cardiometabolic risk factors in childhood and adolescence: a systematic review. Rev Paul Pediatr. 2016;34:225-33. 10.1016/j.rpped.2015.08.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Segall-Corrêa AM.Food insecurity as measured by individual perceptions. Estud Av. 2007;21:143-54. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Melgar-Quinonez H, Hackett M.Measuring household food security: the global experience. Rev Nutr. 2008;21:27-37. 10.1590/S1415-52732008000700004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sperandio N, Morais DC, Priore SE.Perception scales of validated food insecurity: the experience of the countries in Latin America and the Caribbean. Cien Saude Colet. 2018;23:449-62. 10.1590/1413-81232018232.08562016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jones SJ, Frongillo EA.Food insecurity and subsequent weight gain in women. Public Health Nutr. 2007;10:145-51. 10.1017/S1368980007246737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]