Dear Sir:

Risk factors of acute ischemic stroke (AIS) are well-recognised [1], but the relative importance of each contributing risk factor has evolved. Analysing the regional trends of these cardiovascular risk factors will enable the development of more targeted strategies to tackle AIS and reduce morbidity and disability. Few studies have evaluated inter-ethnic risk factor trends within a single co-localised population [2], especially amongst Asians, who have a different risk factor profile and consequently, stroke mechanisms [3]. Singapore is uniquely placed to contribute to the understanding of these trends, given our multi-ethnic population (Supplementary Table 1).

The Singapore Stroke Registry (SSR) is an active nationwide prospective registry collecting data of stroke cases from all public hospitals in Singapore [4]. Our study explored the interethnic trends of incidence and risk factors of AIS cases over a 12-year period using the SSR. These findings can be applied to the development of targeted strategies for the prevention of AIS both locally and regionally.

A total of 60,325 AIS cases from 2005 to 2016 were analysed in 3-year quartiles with direct age standardisation using the 2005 to 2007 Singapore resident population as reference. Data was stratified into ethnic groups based on the Singapore Census classification: Chinese, Malay, Indian, or others: which comprises multiple different ethnic groups, a tiny proportion of the population, and thus were not analysed separately. Prevalence of risk factors amongst AIS cases was analysed within each time-period for each subgroup. Trends were analysed using Poisson, logistic, linear, or Cox regression, depending on the specific variables analysed.

There was a 11.6% decrease in the age-standardised incidence rate (ASIR) of AIS from 2005–2007 to 2014–2016 (Table 1). The decrease in ASIR was observed in both sexes (males 5.9%; females 19.1%). Stratifying by ethnic group, the ASIR had decreased in both Chinese (15.0%) and Indians (11.2%), but increased by 11.5% in Malays, and specifically, by 20.2% in Malay males. Amongst ≥65-year-old cases, the crude incidence rate decreased by 19.1%, as compared to <65-year-old cases, which saw a 31.6% increase.

Table 1.

CIR and ASIR of acute ischemic stroke, per 100,000 person-years (95% CI)

| 2005-2007 |

2008-2010 |

2011-2013 |

2014-2016 |

P |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | CIR | ASIR | No. | CIR | ASIR | No. | CIR | ASIR | No. | CIR | ASIR | CIR | ASIR | |||

| All | 13,384 | 126.5 (124.4-128.7) | 126.5 (124.4-128.7) | 13,866 | 124.4 (122.3-126.4) | 113.9 (112.0-115.8) | 15,448 | 134.9 (132.8-137.0) | 111.3 (109.5-113.0) | 17,627 | 150.6 (148.3-152.8) | 111.8 (110.1-113.4) | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| Sex | ||||||||||||||||

| Male | 7,394 | 141.0 (137.8-144.2) | 141.0 (137.8-144.2) | 7,729 | 140.3 (137.2-143.4) | 128.0 (125.2-130.9) | 8,919 | 158.1 (154.9-161.4) | 130.1 (127.3-132.8) | 10,310 | 179.3 (175.9-182.8) | 132.7 (130.1-135.3) | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| Female | 5,990 | 112.3 (109.5-115.2) | 112.3 (109.5-115.2) | 6,137 | 108.8 (106.1-111.5) | 99.8 (97.3-102.3) | 6,529 | 112.3 (109.6-115.1) | 92.5 (90.3-94.8) | 7,317 | 122.8 (120.0-125.6) | 90.8 (88.7-92.9) | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| Ethnic group | ||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 10,380 | 130.2 (127.8-132.8) | 130.2 (127.8-132.8) | 10,601 | 127.9 (125.5-130.4) | 115.5 (113.3-117.7) | 11,572 | 136.2 (133.8-138.7) | 110.3 (108.2-112.3) | 13,216 | 152.0 (149.4-154.5) | 110.7 (108.7-112.6) | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| Male | 5,630 | 143.1 (139.4-146.9) | 143.1 (139.4-146.9) | 5,911 | 145.2 (141.5-148.9) | 130.0 (126.7-133.3) | 6,669 | 160.4 (156.6-164.3) | 128.6 (125.5-131.8) | 7,696 | 181.3 (177.3-185.4) | 130.7 (127.7-133.7) | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| Female | 4,750 | 117.7 (114.3-121.0) | 117.7 (114.3-121.0) | 4,690 | 111.2 (108.1-114.4) | 101.0 (98.1-103.9) | 4,903 | 113.0 (109.9-116.2) | 92.0 (89.4-94.5) | 5,520 | 124.0 (120.7-127.2) | 90.7 (88.3-93.1) | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| Malay | 1,735 | 119.1 (113.5-124.8) | 119.1 (113.5-124.8) | 2,066 | 137.8 (131.9-143.8) | 124.5 (119.1-129.9) | 2,542 | 166.3 (159.8-172.7) | 136.2 (130.8-141.6) | 2,813 | 179.9 (173.3-186.6) | 132.8 (127.6-137.9) | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| Male | 950 | 130.5 (122.2-138.8) | 130.5 (122.2-138.8) | 1,101 | 147.4 (138.7-156.1) | 133.8 (125.8-141.7) | 1,431 | 188.0 (178.3-197.8) | 155.6 (147.4-163.9) | 1,634 | 210.1 (199.9-220.3) | 156.8 (148.8-164.8) | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| Female | 785 | 107.7 (100.1-115.2) | 107.7 (100.1-115.2) | 965 | 128.3 (120.2-136.4) | 114.7 (107.5-122.0) | 1,111 | 144.7 (136.2-153.2) | 116.8 (109.7-123.8) | 1,179 | 150.0 (141.5-158.6) | 108.4 (101.9-114.9) | <0.001 | 0.151 | ||

| Indian | 960 | 105.8 (99.1-112.5) | 105.8 (99.1-112.5) | 975 | 96.1 (90.0-102.1) | 93.2 (87.4-99.1) | 1,067 | 101.5 (95.4-107.5) | 90.0 (84.5-95.5) | 1,272 | 119.5 (112.9-126.0) | 93.9 (88.6-99.2) | <0.001 | 0.002 | ||

| Male | 615 | 131.7 (121.3-142.1) | 131.7 (121.3-142.1) | 594 | 113.0 (103.9-122.1) | 112.1 (103.0-121.2) | 666 | 122.8 (113.5-132.1) | 112.3 (103.6-121.0) | 788 | 144.2 (134.1-154.2) | 118.3 (109.7-126.9) | <0.001 | 0.018 | ||

| Female | 345 | 78.3 (70.0-86.6) | 78.3 (70.0-86.6) | 381 | 77.8 (70.0-85.7) | 72.6 (65.2-79.9) | 401 | 78.7 (71.0-86.4) | 65.7 (59.2-72.3) | 484 | 93.4 (85.1-101.7) | 66.6 (60.5-72.8) | 0.015 | 0.054 | ||

| Age (yr) | ||||||||||||||||

| <65 | 4,950 | 51.0 (49.6-52.5) | 51.0 (49.6-52.5) | 5,507 | 54.2 (52.8-55.6) | 48.7 (47.4-50.0) | 6,374 | 61.8 (60.3-63.3) | 50.8 (49.5-52.0) | 6,932 | 67.1 (65.5-68.7) | 52.4 (51.1-53.6) | <0.001 | 0.017 | ||

| >65 | 8,434 | 958.4 (937.9-978.9) | 958.4 (937.9-978.9) | 8,359 | 849.2 (831.0-867.4) | 832.0 (814.2-849.8) | 9,074 | 799.0 (782.5-815.4) | 778.0 (762.0-794.0) | 10,695 | 775.6 (760.9-790.3) | 766.0 (751.5-780.5) | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

CIR, crude incidence rate; ASIR, age-standardised incidence rate; CI, confidence interval.

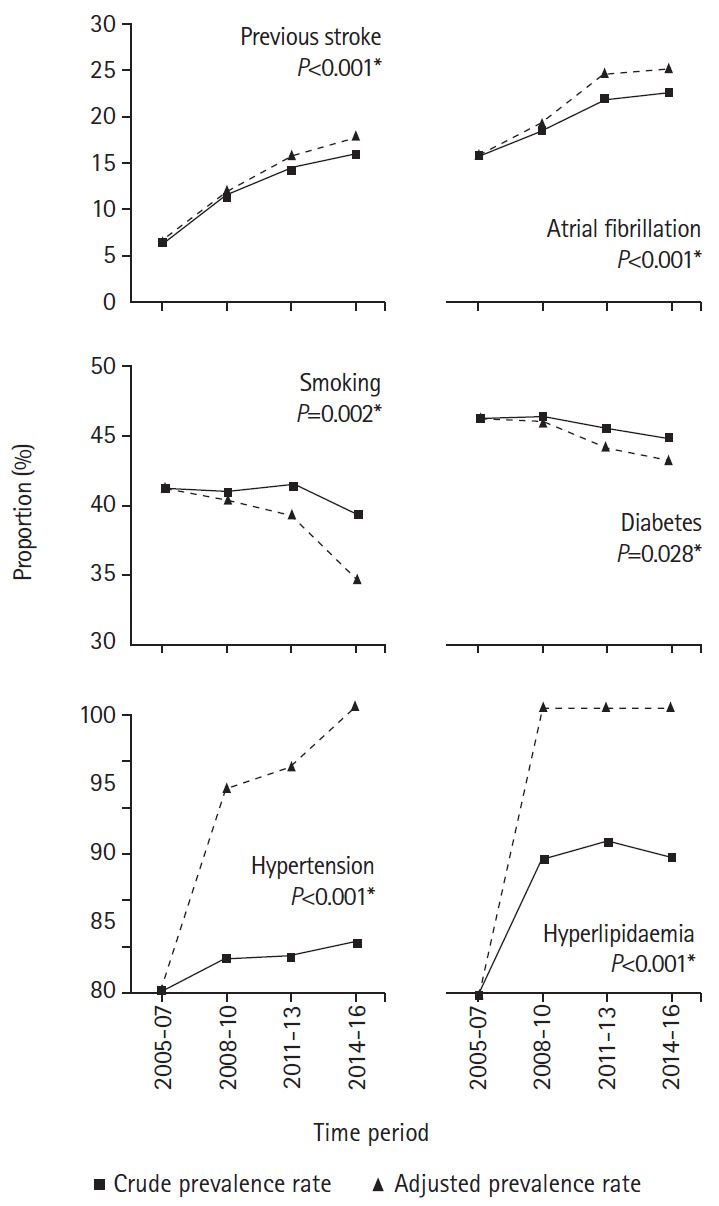

Amongst AIS risk factors (Figure 1), history of stroke (6.3% to 17.6%), atrial fibrillation (AF; 15.8% to 25.2%), hypertension (80.2% to 100%), and hyperlipidaemia (79.9% to 100%) have increased in prevalence after adjusting for age, sex, and ethnic group. In contrast, the adjusted prevalence of smoking (41.2% to 34.6%), and diabetes (46.2% to 43.2%) have decreased. In terms of ethnic variation, AF was strikingly more prevalent in Chinese and Malays with AIS, in contrast to Indians. However, in all three ethnic groups, AF showed an increasing prevalence over time (Chinese: 16.5% to 24.2%, P<0.001; Malays: 16.9% to 19.8%, P=0.011; Indians: 7.1% to 12.3%, P=0.001). We also observed that AF was more prevalent in females (ranging between 19.8% to 29.5%) than males (between 12.6% to 17.8%) across all time periods.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of risk factors for acute ischemic stroke over time. *This is shown as a % of the stroke population.

In subgroups that showed increased AIS incidence: <65-year-old patients and Malay males, there were risk factors that showed a different trend as compared to the general population of AIS cases. In <65-year-old AIS cases, the prevalence of smoking increased from 48.6% to 51.9% (P<0.001). Amongst Malay males with AIS, the prevalence of diabetes increased from 51.7% to 55.2% (P=0.022).

Our finding of a significant decrease in the overall incidence of AIS across a 12-year period from 2005 to 2016 is consistent with studies done in non-Asian and less heterogeneous populations [2]. This decrease can be attributed, in part, to reductions in the prevalence of smoking and diabetes, both being common risk factors for AIS, especially in Asia [5]. These trends are encouraging and worth further exploration to understand how stroke incidence can be further reduced, especially amongst Malays, which has seen an increase in incidence. In contrast to the general population of AIS cases, the increased prevalence of smoking and diabetes amongst younger cases and Malay males respectively may have contributed to the increased incidence of AIS in these subgroups and efforts should be made to tackle these worrying trends. Changes include increasing the legal smoking age from 18 to 21 in 2021 [6], and campaigns aiming to reduce sugar intake during the traditional Malay feasting periods of Ramadan and Hari Raya [7]. Effects of these changes should be evaluated, ensuring that such trends are reversed.

In the general population of AIS cases, the prevalence of AF, hypertension, hyperlipidaemia and previous stroke has increased. More attention should be given to these risk factors, and especially AF, given the striking jump in prevalence. The increase in AF prevalence in AIS cases might reflect changes in diagnostic techniques and increased use of technology such as implantable loop recorders and telemetry rather than a true increase in the general population. Furthermore, this trend could also reflect under-utilisation of anticoagulation [8]. Recent Asia-based studies have reported that patients are often prescribed reduced doses of anticoagulation off-label [9], or have lower compliance rates compared to Western populations [10]. These observations highlight a significant concern that whilst AF prevalence amongst AIS cases in Singapore is increasing, lack of anticoagulant utilisation, under-dosing and compliance issues may lead to increased thromboembolic complications. Further research should be done to ascertain barriers to effective anticoagulation.

We report a significantly higher prevalence of AF amongst Chinese and Malays, as compared to Indians, in our population of AIS cases. There have been studies that suggest reduced prevalence of AF in Indians as compared to Chinese [11]. Larger population-wide studies in Indian communities will help to confirm this and identify possible causative reasons. Future comparative studies in these communities using genome-wide association study methodology might also uncover protective heritability factors against AF [12]. While the strengths of our study lie in its large number of cases and its multi-ethnic composition, it does have limitations. Importantly, the SSR does not classify AIS cases into stroke aetiology subtypes, limiting the analysis of specific reasons behind changes in incidence rates.

In conclusion, while there has been a decreasing incidence of AIS in Singapore in keeping with global trends, this trend is not observed in all subgroups. Our study highlights possible contributing factors, such as smoking in <65-year-old AIS cases, and diabetes in male Malay cases. AF has also been shown to be an increasingly important risk factor with clinical implications in different ethnic populations. Observations highlighted in our study could serve as important directions for improved strategies to tackle the growing stroke morbidity.

Footnotes

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

Supplementary materials

Supplementary materials related to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.5853/jos.2020.00878.

Demographic data of Singapore residents between 2005 and 2016

References

- 1.O’Donnell MJ, Chin SL, Rangarajan S, Xavier D, Liu L, Zhang H, et al. Global and regional effects of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with acute stroke in 32 countries (INTERSTROKE): a case-control study. Lancet. 2016;388:761–775. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30506-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wafa HA, Wolfe CD, Rudd A, Wang Y. Long-term trends in incidence and risk factors for ischaemic stroke subtypes: prospective population study of the South London Stroke Register. PLoS Med. 2018;15:e1002669. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ng WK, Goh KJ, George J, Tan CT, Biard A, Donnan GA. A comparative study of stroke subtypes between Asians and Caucasians in two hospital-based stroke registries. Neurol J Southeast Asia. 1998;3:19–26. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Venketasubramanian N, Chang HM, Chan BP, Young SH, Kong KH, Tang KF, et al. Countrywide stroke incidence, subtypes, management and outcome in a multiethnic Asian population: the Singapore Stroke Registry: methodology. Int J Stroke. 2015;10:767–769. doi: 10.1111/ijs.12472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ma RC, Chan JC. Type 2 diabetes in East Asians: similarities and differences with populations in Europe and the United States. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2013;1281:64–91. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Minimum legal age for smoking to be raised to 19 on Jan 1. CAN. https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/singapore/minimum-legal-age-smoking-tobacco-changes-19-jan-11069294. 2018. Accessed July 18, 2020.

- 7.Neo R. Mosques serve healthier food during iftar this Ramadan. The Straits Times. The Straits Times; https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/mosques-serve-healthier-food-during-iftar-this-ramadan. 2019. Accessed July 18, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mazurek M, Huisman MV, Rothman KJ, Paquette M, Teutsch C, Diener HC, et al. Regional differences in antithrombotic treatment for atrial fibrillation: insights from the GLORIA-AF phase II registry. Thromb Haemost. 2017;117:2376–2388. doi: 10.1160/TH17-08-0555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee SR, Lee YS, Park JS, Cha MJ, Kim TH, Park J, et al. Label adherence for non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants in a prospective cohort of Asian patients with atrial fibrillation. Yonsei Med J. 2019;60:277–284. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2019.60.3.277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tan BY, Leow AS, Teoh HL, Gopinathan A, Yang C, Paliwal PR, et al. High incidence of under-treated atrial fibrillation: perspectives from an Asian Stroke Endovascular Thrombectomy Registry. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2020;49:268–270. doi: 10.1007/s11239-019-02019-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nguyen TN, Hilmer SN, Cumming RG. Review of epidemiology and management of atrial fibrillation in developing countries. Int J Cardiol. 2013;167:2412–2420. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.01.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roselli C, Chaffin MD, Weng LC, Aeschbacher S, Ahlberg G, Albert CM, et al. Multi-ethnic genome-wide association study for atrial fibrillation. Nat Genet. 2018;50:1225–1233. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0133-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Demographic data of Singapore residents between 2005 and 2016