Graphical abstract

Abbreviations: BaP, benzo[a]pyrene; HPHC, harmful and potentially harmful constituents; NAB, N’-nitrosoanabasine; NAT, N’-nitrosoanatabine; NNK, 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-bipyridyl)-1-butanone; NNN, N’-nitrosonornicotine; PAH, polyaromatic hydrocarbons; PG, propyleneglycol; RS, reducing sugars; TA, total alkaloids; TCM, total collected matter; TSNA, tobacco specific nitrosamines

Keywords: Waterpipe, Waterpipe aerosols, ISO 22486, Aldehydes, Formaldehyde, Charcoals for waterpipe

Highlights

-

•

ISO 22486 to be complemented with real conditions for the evaluation of waterpipe.

-

•

Charcoal is the main contributor to CO and BaP in waterpipe aerosols.

-

•

Correlation between sugars content in tobaccos and formaldehyde yields in aerosols.

Abstract

This study analyzed commercial waterpipe tobacco products in accordance with the newly developed ISO 22486 as well as with commercial waterpipes and charcoals using the ISO 22486 puffing regime for comparison. The aerosols from these products were analyzed for their nicotine, humectant, tobacco specific nitrosamine, carbonyl, benzo[a]pyrene, and metal yields. Significant differences were observed among the waterpipe tobacco products when analyzed in accordance with the ISO standard 22486 and with different commercial waterpipes and charcoals. The concentrations of CO and benzo[a]pyrene observed in the consumers’ configuration using the ISO 22486 puffing regime (with lit charcoal) were higher than those obtained with the ISO standard using electrical heating, with the yields for carbonyl compounds being lower or higher. The use of the recently published ISO standard for generating water pipe tobacco aerosols should be complemented with analysis by using the consumers’ configuration. The necessity for this was demonstrated by the differences in CO and benzo[a]pyrene yields in the present work. It appears that the temperature (280°C) selected for electrical heating of waterpipe tobacco products in ISO 22486 is somewhat lower than that obtained with commercial charcoals, resulting in a generally lower yield of nicotine and total collected matter. In addition, there is a need to evaluate the contribution of commercial charcoals to the concentration of constituents in waterpipe aerosols. This is particularly true for compounds resulting from charcoal combustion, such as CO and benzo[a]pyrene.

1. Introduction

Waterpipe smoking has historically been a traditional form of smoking among men in Middle Eastern countries. Although the the Arabian Peninsula and Middle East [1] still have the highest prevalence of waterpipe smoking, it has become more popular in other parts of the world [2], including the USA [3], the UK [4], and Russia [5]. There are two general categories of waterpipe tobacco: unflavored (with plain and dry tobacco) or flavored (with added humectants [such as glycerine and propylene glycol], honey or molasses, and flavors). Because of its high moisture content, flavored waterpipe tobacco does not burn in a self-sustaining manner as does the tobacco in cigarettes. It requires an external heat source, usually coal in the form of briquettes, which is placed on top of the waterpipe tobacco. Waterpipe tobacco is consumed through shishas/hookas, which comprise—in addition to the head with tobacco and coal—a body, water bowl, hose, and mouthpiece [2].

On the basis of the observed behavior of waterpipe smokers, a standardized puffing protocol, sometimes called the Beirut method smoking protocol, has been proposed by Shihadeh et al. [6]. This puffing protocol has been widely used for generating aerosol from waterpipe tobacco and has provided data on the harmful and potentially harmful constituents (HPHC) present in the mainstream smoke of waterpipe tobacco [[7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12]]. The same puffing protocol was used, with very slight modifications, for developing the ISO standard 22486 [13], which provides the specifications for an analytical waterpipe puffing machine. This standard employs electrical heating of waterpipe tobacco at a temperature of 280℃—instead of the charcoal heating used by waterpipe tobacco users with traditional waterpipes—as well as a standardized laboratory waterpipe, consisting of a glass bottle with a fixed volume of water and plastic tubes, to replace the commercial waterpipe device.

The goal of this work was to analyze the yields of selected aerosol constituents obtained by using the standardized ISO puffing analytical smoking machine with a range of commercial waterpipe tobacco products. This study also aimed to compare these yields with those obtained with the same products under the same puffing conditions, but with the consumers’ configuration, to understand the limitations of the recently developed ISO standard [13] as well as the influence of the different elements of commercial waterpipes. It is known, for example, that the charcoal used to heat waterpipe tobacco is the primary source of a number of HPHCs in waterpipe tobaccos’ aerosols, including CO [14,15], polyaromatic hydrocarbons (PAH) [[15], [16], [17]], and metals [18].

2. Methods

2.1. Samples

Eleven samples of commercial waterpipe tobacco, five waterpipes, and four charcoals were bought from a retailer in Egypt, the United Arab Emirates, and Switzerland between January and February 2019. The list of products is provided in the supplementary material.

2.2. Procedure

The analyses were performed at ALS Analytical Services GmbH, Hamburg Germany, between March and May 2019. Aerosols from all waterpipe tobacco products were generated in accordance with the protocol described in ISO 22486 [13], by using a Borgwaldt Shisha smoking machine connected to a standard laboratory waterpipe from Borgwaldt, with 175 puffs of 530 mL each, taken every 20 s (puff duration, 2.6 s). For each session, 10 g of tobacco and between one and four pieces of charcoal briquettes (depending on size and to cover as much as possible the whole surface of the waterpipe device charcoal support piece) were used. In addition, the aerosols of all waterpipe tobacco products were also generated by using commercial charcoals and waterpipes (according to the matrix shown in Table 3) by using a Borgwaldt Shisha smoking machine and the same puffing regimen as that described above. The combinations of waterpipe tobaccos, waterpipe devices and commercial charcoals were selected in order to represent potential use by consumers in the selected countries (Egypt, United Arab Emirates and Switzerland).

Table 3.

Selected constituents in waterpipe product aerosols generated by using commercial waterpipe devices and charcoals and the ISO 22486 puffing regime.

| Constituent | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water pipe tobacco | T1 | T1 | T2 | T3 | T5 | T6 | T7 | T8 | T9 | T10 | T11 |

| Waterpipe device | D1 | D1 | D1 | D2 | D2 | D3 | D3 | D4 | D5 | D5 | D5 |

| Charcoal | C1 | C2 | C1 | C1 | C1 | C3 | C4 | C4 | C3 | C4 | C3 |

| TCM (mg/session) | 4526 | 2827 | 3862 | 3404 | 11990 | 472 | 380 | 1438 | 688 | 544 | 3433 |

| Water (mg/session) | 2757.3 | 1799.3 | 2064.6 | 2169.0 | 9794.1 | 344.1 | 259.9 | 364.0 | 442.8 | 224.2 | 1998.9 |

| Nicotine (mg/session) | 2.74 | 2.00 | 3.04 | 7.68 | 4.98 | <0.5 | 2.19 | 4.76 | 5.20 | 13.40 | 4.59 |

| PG (mg/session) | 48.0 | 47.4 | 101.0 | 76.6 | 181.1 | <4 | <4 | 400 | <4 | <4 | <4 |

| Glycerol (mg/session) | 1271.0 | 775.8 | 1126.4 | 718.4 | 585.5 | 19.2 | <3 | 423 | 21.3 | 53.1 | 786.5 |

| CO (mg/session) | 124.5 | 228.9 | 119.0 | 148.0 | 157.1 | 153.2 | 99.0 | 135 | 473 | 186.2 | 311.9 |

| Formaldehyde (μg/session) | 986.2 | 768.7 | 1171.4 | 1025.4 | 1238.5 | 75.1 | 68.8 | 807 | 141.2 | 170.0 | 395.5 |

| Acetaldehyde (μg/session) | 1055.7 | 785.4 | 1458.8 | 1992.1 | 2953.1 | 89.2 | 533.5 | 747 | 985.4 | 1233.8 | 1099.4 |

| Acetone (μg/session) | 618.8 | 491.3 | 869.0 | 920.2 | 658.8 | <12 | 109.2 | 676 | 341.1 | 481.6 | 573.4 |

| Acrolein (μg/session) | 318.3 | 169.6 | 401.7 | 379.8 | 424.1 | <12 | <12 | 112 | 68.5 | 80.6 | 177.2 |

| Propionaldehyde (μg/session) | 145.2 | 99.4 | 319.4 | 244.7 | 334.6 | <12 | <12 | 72 | 73.7 | 143.0 | 109.5 |

| Crotonaldehyde (μg/session) | <12 | <12 | <12 | <12 | <12 | <12 | <12 | <12 | <12 | <12 | <12 |

| 2-Butanone (μg/session) | <18 | <18 | <18 | <18 | <18 | <18 | <18 | <18 | <18 | <18 | <18 |

| Butyraldehyde (μg/session) | <35 | <35 | <35 | <35 | <35 | <35 | <35 | <35 | <35 | <35 | <35 |

| B[a]P (μg/session) | 7.2 | 17.0 | 4.7 | 2.6 | 2.3 | 1.7 | 5.2 | 4.2 | 43.6 | 96.8 | 23.7 |

| Arsenic (μg/session) | <0.16 | <0.16 | <0.16 | <0.16 | <0.16 | <0.16 | <0.16 | <0.16 | <0.16 | <0.16 | <0.16 |

| Lead (μg/session) | 1.93 | 6.45 | 1.55 | 6.00 | 8.80 | <0.16 | 0.84 | <0.16 | <0.16 | <0.16 | <0.16 |

| Cadmium (μg/session) | <0.16 | <0.16 | <0.16 | <0.16 | <0.16 | <0.16 | <0.16 | <0.16 | <0.16 | <0.16 | <0.16 |

| Nickel (μg/session) | 0.60 | 3.65 | 1.12 | 3.88 | 4.16 | <0.16 | <0.16 | <0.16 | <0.16 | <0.16 | <0.16 |

| Chrome (μg/session) | <0.16 | <0.16 | <0.16 | <0.16 | <0.16 | <0.16 | <0.16 | <0.16 | <0.16 | <0.16 | <0.16 |

| Selenium (μg/session) | <0.16 | <0.16 | <0.16 | <0.16 | <0.16 | <0.16 | <0.16 | <0.16 | <0.16 | <0.16 | <0.16 |

| NNN (μg/session) | <0.08 | <0.08 | <0.08 | <0.08 | <0.08 | <0.08 | <0.08 | <0.08 | 0.63 | 12.09 | 0.10 |

| NAT (μg/session) | <0.08 | <0.08 | <0.08 | <0.08 | <0.08 | <0.08 | 0.09 | <0.08 | 0.21 | 2.36 | <0.08 |

| NAB (μg/session) | <0.08 | <0.08 | <0.08 | <0.08 | <0.08 | <0.08 | <0.08 | <0.08 | <0.08 | <0.08 | <0.08 |

| NNK (μg/session) | <0.08 | <0.08 | <0.08 | <0.08 | <0.08 | <0.08 | <0.08 | <0.08 | <0.08 | 2.40 | <0.08 |

The limits of quantification correspond to the limits expressed per an amount of 35 puffs. Results below the limit of quantification were considered null in the sum of the five groups of 35 puffs (one session corresponds to 175 puffs).

Five groups of 35 puffs, totaling 175 puffs, generated in accordance with the protocol described in ISO 22486, were collected for further analysis of HPHCs. For analysis of CO, five groups of 30 puffs were collected in order to allow some time for measuring CO concentrations between the groups of puffs. Nicotine was analyzed by gas chromatography with flame ionization detector (GC-FID) in accordance with ISO standard 10315 [19]; CO was analyzed by near-infrared spectroscopy in accordance with ISO standard 8454 [20]. Carbonyls were trapped in liquid impingers, derivatized with 2,4-dinotrophenylhydrazine, and analyzed by liquid chromatography with ultraviolet detection (LC-UV) in accordance with CORESTA CRM 86 [21]. Tobacco-specific nitrosamines (TSNA) were analyzed by LC–tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS) in accordance with ISO 19290 [22]. Benzo[a]pyrene (B[a]P) was analyzed by LC with fluorescence detector (LC-FLD). Metals were analyzed by inductively coupled plasma MS (ICP-MS), and glycerol and propylene glycol by GC-FID.

The waterpipe tobacco products were also analyzed for nicotine content by GC-FID, propylene glycol and glycerol content by GC-FID, and nitrosamine content by LC–MS/MS in accordance with ISO 22303 [23]; reducing sugar and total alkaloid content by continuous flow analysis in accordance with ISO 15154 [24] and ISO 15152 [25], respectively; and metal content by ICP/MS. One replicate per analysis was performed.

3. Results

3.1. Waterpipe tobacco

The results of analysis of the water pipe tobacco products are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Results of analysis of waterpipe tobacco.

| Constituent | Water pipe tobacco product |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | T6 | T7 | T8 | T9 | T10 | T11 | |

| Glycerol (%) | 38.3 | 42.0 | 36.3 | 26.6 | 32.1 | 1.1 | 23.3 | 2.5 | 0.8 | 39.1 |

| PG (%) | 0.92 | 2.45 | 1.34 | 4.45 | <0.2 | <0.2 | 8.47 | <0.2 | <0.2 | <0.2 |

| Nicotine (%) | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.12 | 0.07 | 0.23 | 0.10 | 0.25 | 0.28 | 0.11 |

| TA (%) | <0.20 | <0.20 | <0.20 | <0.20 | <0.20 | 0.37 | <0.20 | 0.37 | 0.60 | <0.20 |

| RS (%) | 21.5 | 17.8 | 31.8 | 27.5 | 28.7 | 22.3 | 34.2 | 23.4 | 16.8 | 22.3 |

| Water (%) | 13.2 | 11.0 | 13.1 | 12.8 | 13.7 | 17.1 | 10.1 | 19.1 | 14.1 | 14.5 |

| Arsenic (mg/kg) | 0.025 | 0.029 | 0.039 | 0.018 | 0.012 | 0.136 | 0.023 | 0.153 | 0.282 | 0.015 |

| Lead (mg/kg) | 0.079 | 0.089 | 0.135 | 0.099 | 0.054 | 0.274 | 0.063 | 0.308 | 0.570 | 0.047 |

| Cadmium (mg/kg) | 0.343 | 0.184 | 0.253 | 0.325 | 0.310 | 0.226 | 0.270 | 0.253 | 0.158 | 0.227 |

| Nickel (mg/kg) | 0.196 | 0.063 | 0.416 | 0.221 | 0.113 | 1.296 | 0.134 | 1.418 | 2.099 | 0.169 |

| Chrome (mg/kg) | 0.212 | 0.069 | 0.365 | 0.104 | 0.072 | 1.315 | 0.095 | 0.939 | 1.626 | 0.331 |

| Selenium (mg/kg) | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.088 | <0.01 | 0.048 | 0.106 | <0.01 |

| Mercury (mg/kg) | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| NNN (mg/kg) | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | 0.39 | <0.05 | 1.3 | 18.2 | <0.05 |

| NAT (mg/kg) | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | 0.32 | <0.05 | 0.53 | 4.8 | 0.053 |

| NAB (mg/kg) | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | 0.052 | 2.8 | <0.05 |

| NNK (mg/kg) | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | 0.08 | <0.05 | 0.19 | 3.3 | <0.05 |

All results are provided as is (without correction of water content).

Three products contained essentially no humectants (T7, T9, and T10), while the other waterpipe tobacco products contained 30–40 % of humectants, with glycerol being the main or only humectant. The levels of nicotine were about 0.1 % and 0.2–0.3 %, respectively, in waterpipe tobacco products with and without humectants. The level of reducing sugars was determined from the levels of reducing sugars contained in tobacco (mainly glucose and fructose) as well as any possibly added sugars in the products.

The levels of elements in the evaluated waterpipe tobacco products were generally in line with those observed in waterpipe tobacco samples by other authors [8,26], with the exception of tobacco products T7, T9, and T10 — these tobacco products contain essentially no humectants and, therefore, possibly have a higher tobacco content than the other waterpipe tobacco products. The variation of results observed for the concentrations of elements among the waterpipe tobacco products is a consequence of the origin [27,28] of the tobacco used in the waterpipe products as well as the amount of tobacco (assuming it is the main source of the elements) in the product.

The levels of TSNAs were below the limit of quantification (LOQ) in most samples, with the exception of the three products that did not contain humectants. The higher TSNA levels in some products are attributable to a combination of higher tobacco content in those products and possibly the use of different tobacco blends: Burley and dark tobacco have a higher TSNA content than flue-cured Virginia tobacco [29,30].

3.2. Waterpipe tobaccos aerosols

Table 2 presents the results of analysis of the waterpipe products aerosols generated in accordance with the ISO standard [13] by using an electrical heater at 280℃. Table 3 presents the results obtained by using commercial waterpipe devices and charcoals with the same puffing regimen.

Table 2.

Selected constituents in waterpipe product aerosols generated in accordance with the ISO standard 22486 [13].

| Constituent | Water pipe tobacco product |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | T2 | T3 | T5 | T6 | T7 | T8 | T9 | T10 | T11 | |

| TCM (mg/session) | 2750 | 2894 | 2148 | 790 | 2732 | 602 | 2900 | 822 | 572 | 2116 |

| Water (mg/session) | 1430.7 | 1564.5 | 1245.5 | 436.2 | 1580.5 | 372.5 | 1670.2 | 500.5 | 340.2 | 1203.6 |

| Nicotine (mg/session) | 1.84 | 2.64 | 4.45 | <0.5 | 1.25 | 3.82 | 3.63 | 7.43 | 10.91 | 2.83 |

| PG (mg/session) | 33.1 | 67.8 | 53.4 | 54.2 | <4 | <4 | 344.0 | <4 | <4 | <4 |

| Glycerol (mg/session) | 798.7 | 900.0 | 486.7 | 57.9 | 854.4 | 10 | 558.3 | 40.4 | 6.1 | 288.9 |

| CO (mg/sesssion) | <2 | <2 | 9 | 9.0 | 3.6 | 9.0 | 12.6 | 10.8 | 14.4 | 9.0 |

| Formaldehyde (μg/session) | 285.7 | 268.0 | 275.5 | 302.4 | 409.0 | 160.9 | 369.1 | 191.9 | 211.6 | 351.5 |

| Acetaldehyde (μg/session) | 318.1 | 241.5 | 549.2 | 868.8 | 325.9 | 1367.5 | 490.9 | 1100.3 | 1319.5 | 372.7 |

| Acetone (μg/session) | 135.8 | 257.2 | <12 | 275.2 | 202.2 | 197.5 | 34.8 | 221.3 | 301.2 | 157.3 |

| Acrolein (μg/session) | 58.3 | 97.0 | 87.6 | 115.7 | 88.6 | 34.6 | <12 | <12 | 40.6 | 62.5 |

| Propionaldehyde (μg/session) | 14.2 | <12 | <12 | 112.9 | <12 | 68.4 | <12 | <12 | 103.5 | <12 |

| Crotonaldehyde (μg/session) | <12 | <12 | <12 | <12 | <12 | <12 | <12 | <12 | <12 | <12 |

| 2-Butanone (μg/session) | <18 | <18 | <18 | <18 | <18 | <18 | <18 | <18 | <18 | <18 |

| Butyraldehyde (μg/session) | <35 | <35 | <35 | <35 | <35 | <35 | <35 | <35 | <35 | <35 |

| B[a]P (μg/session) | <1 | <1 | <1 | <1 | <1 | 4.8 | <1 | 5.2 | 17.8 | <1 |

| Arsenic (μg/session) | <0.16 | <0.16 | <0.16 | <0.16 | <0.16 | <0.16 | <0.16 | <0.16 | <0.16 | <0.16 |

| Lead (μg/session) | 8.49 | 9.64 | 13.39 | 2.39 | 4.21 | <0.16 | 4.85 | <0.16 | 0.44 | 2.46 |

| Cadmium (μg/session) | <0.16 | <0.16 | <0.16 | <0.16 | <0.16 | <0.16 | <0.16 | <0.16 | <0.16 | <0.16 |

| Nickel (μg/session) | 9.64 | 7.35 | 7.93 | 0.91 | 2.89 | <0.16 | 3.42 | <0.16 | 0.20 | 0.74 |

| Chrome (μg/session) | 0.28 | <0.16 | <0.16 | <0.16 | <0.16 | <0.16 | <0.16 | <0.16 | <0.16 | <0.16 |

| Selenium (μg/session) | 0.44 | <0.16 | <0.16 | <0.16 | <0.16 | <0.16 | <0.16 | <0.16 | <0.16 | <0.16 |

| NNN (μg/session) | <0.08 | <0.08 | <0.08 | <0.08 | <0.08 | 0.12 | <0.08 | 0.67 | 16.96 | <0.08 |

| NAT (μg/session) | <0.08 | <0.08 | <0.08 | <0.08 | <0.08 | 0.22 | <0.08 | 0.31 | 3.81 | <0.08 |

| NAB (μg/session) | <0.08 | <0.08 | <0.08 | <0.08 | <0.08 | <0.08 | <0.08 | <0.08 | 2.81 | <0.08 |

| NNK (μg/session) | <0.08 | <0.08 | <0.08 | <0.08 | <0.08 | <0.08 | <0.08 | <0.08 | 2.40 | <0.08 |

The limits of quantification correspond to the limits expressed per an amount of 35 puffs. Results below the limit of quantification were considered null in the sum of the five groups of 35 puffs.

The results of comparison of the aerosols of the same waterpipe tobacco products generated by using the analytical waterpipe machine and electrical heating in accordance with the ISO protocol [13] or by using commercial waterpipes and charcoals with ISO 22486 puffing regime were as follows:

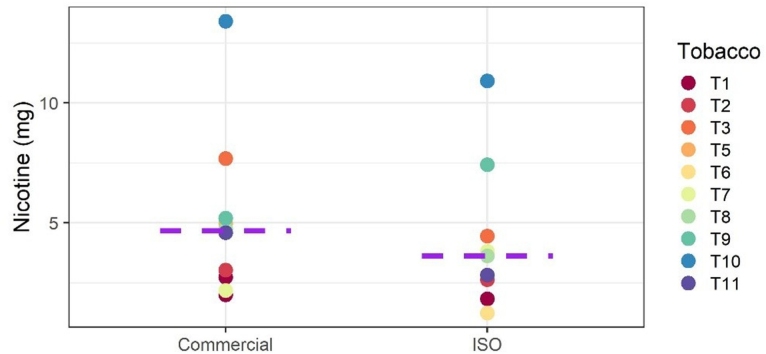

In most cases, the yields for nicotine and total collected matter (TCM) were higher in the aerosols generated by using the commercial waterpipes and charcoals than in those generated in accordance with the ISO protocol, with the following exceptions: Nicotine yields were lower with the commercial combinations T6/D3/C3, T7/D3/C4, and T11/D5/C3; TCM yields were lower with the commercial combination T6/D3/C3 and almost equivalent with T7/D3/C4 and T8/D4/C4. This might be the result of differences in temperature and retention in the bubbling water [31] (because of differences in total volume). This result is also illustrated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Nicotine yields in waterpipe tobacco product aerosols generated by using the commercial configuration (with commercial charcoals and waterpipedevices) or the ISO 22486 configuration (with an analytical waterpipe smoking machine).

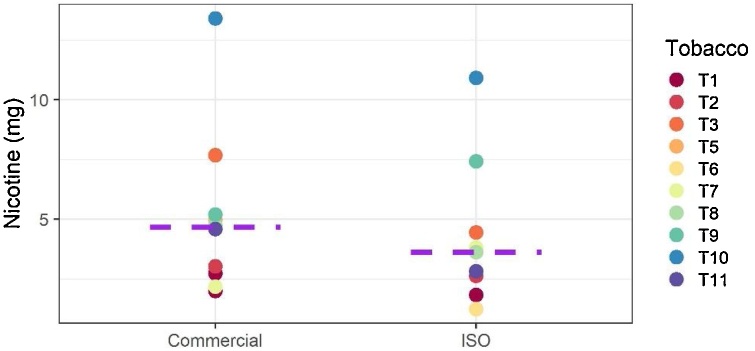

In all cases, CO yields were increased in aerosols generated by using commercial waterpipes and charcoals. While the CO yields obtained with the ISO analytical waterpipe smoking machine ranged from below the LOQ to 14.4 mg/session, those obtained with the waterpipes and charcoals ranged from 99 to 473 mg/session. Fig. 2 shows the comparison of CO yields between the ISO and commercial configurations. These results confirm what has been already observed: The charcoals used to heat waterpipe tobacco products are the main source of CO in the waterpipe products aerosols [7]. Monzer et al. [15] demonstrated that, when charcoal is substituted by electrical heating, the levels of CO and PAH are significantly reduced in waterpipe products aerosols. The CO concentration ranges observed with the commercial waterpipes and the ISO 22486 puffing regime in the present study are also in line with those reported previously [7].

Fig. 2.

CO yields in waterpipe tobacco product aerosols generated by using the commercial configuration (with commercial charcoal and waterpipes) or the ISO 22486 configuration (with an analytical waterpipe smoking machine).

We observed the same trend in the yield of B[a]P, which was in all cases higher in aerosols generated by using commercial waterpipes and charcoals than in those generated by using the ISO protocol. This is in line with previous results obtained with different types of charcoals and when comparing electrical and charcoal heating of waterpipe tobacco products [[15], [16], [17]].

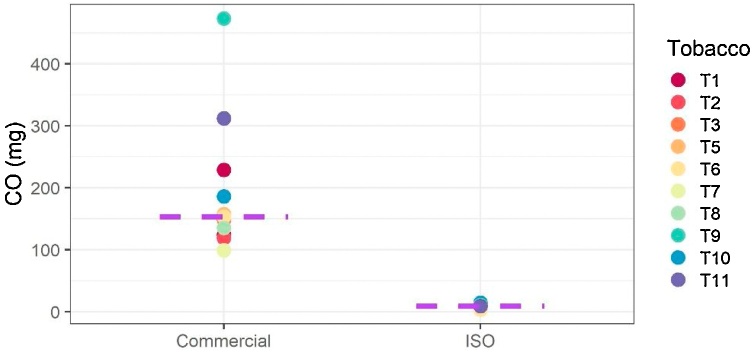

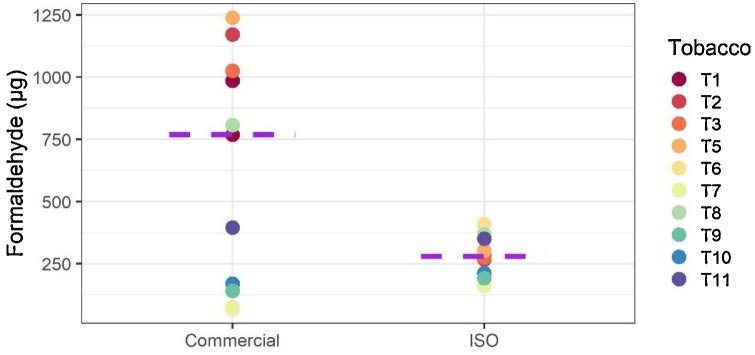

Aldehydes and ketones are produced upon thermal degradation of tobacco constituents such as sugars and cellulose [32] and have already been analyzed in waterpipe tobacco aerosols [7]. They can be generated at relatively low temperatures. Formaldehyde precursors, for example, decompose at about 250℃ [33]. Formaldehyde, in contrast to other aldehydes, can be formed in higher quantities from mono- and di-saccharides than from polysaccharides, such as the cellulose present in tobacco [32]. Our data showed a slight correlation between the levels of reducing sugars (essentially the monosaccharides glucose and fructose in tobacco) in the waterpipe tobacco products and the amount of formaldehyde in their aerosols, as illustrated in Fig. 3. However, reducing sugar levels were not correlated with acrolein yield and slightly negatively correlated with acetaldehyde yield. Schubert et al. [10] also demonstrated the role of humectants in the release of aldehydes and ketones in waterpipe product aerosols and observed that increasing amounts of humectants resulted in lower yields of these two products. In general, the range of values obtained in the present study is in line with previously published results [7,9].

Fig. 3.

Correlation between reducing sugars in waterpipe tobacco products and the formaldehyde yields (using the ISO 22486 protocol) in their aerosols.

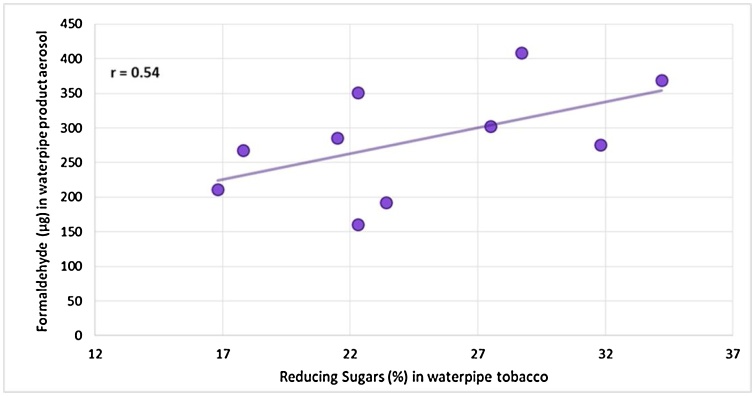

There was no systematic tendency in the carbonyl yields from aerosols generated by using the analytical waterpipe smoking machine or the commercial products (see also Fig. 4 for the results on formaldehyde yield). Aerosols from some commercial devices and charcoals showed a significant increase in the yields of carbonyl compounds (for example, devices D1 and D2, but not D3). It should be noted that, while the volume of water used in the analytical waterpipe aerosol machine prescribed by the ISO standard is standardized, this is not the case in commercial devices. It is also known that carbonyl compounds might be retained in the water bubbling volume and that the percentage of retention might be linked with the volume of water contained in the waterpipe device [31].

Fig. 4.

Formaldehyde yields in the waterpipe tobacco product aerosols generated by using the commercial configuration (with commercial charcoal and waterpipes) or the ISO 22486 configuration (with an analytical waterpipe smoking machine).

TSNA yields, when above the LOQ, were generally very similar in aerosols generated with the analytical waterpipe machine and the commercial waterpipes and charcoals. TSNAs can transfer into aerosols only by direct distillation, pyrorelease, or pyrosynthesis of tobacco [34] and cannot be sourced from charcoal.

In general, higher metals yields (Pb and Ni) were observed in the waterpipe tobacco aerosols generated with the analytical waterpipe machine. This is somewhat in contradiction with a previous observation that commercial charcoals can be the source of metals in waterpipe tobacco aerosols [18]. It should be noted that a previous study reported higher concentrations of Cd, Zn, and Pb in the body fluids of waterpipe tobacco consumers than in never smokers [35].

Upon comparing the same waterpipe tobacco product (T1) aerosols generated with the same device but by using two different charcoals, most compounds yields appeared to be lower with charcoal C2 (TCM, nicotine, glycerol, and aldehydes) than with charcoal C1, possibly because of the lower temperature applied to the waterpipe tobacco with charcoal C2. However, the concentrations of some other compounds that are essentially driven by the quality of the charcoal (such as CO, B[a]P, Pb, and Ni) were higher in the aerosol generated with C2 than in that generated with C1. As observed by other authors, differences in the quality of charcoal might result in differences in the yields of these compounds [16,17].

It is difficult to compare the present results on nicotine and HPHC yields in the waterpipe aerosols with those in other tobacco products [34,36]. While comparison of e-cigarette or heated tobacco product aerosols with mainstream cigarette smoke in terms of nicotine and HPHC yields has been widely practiced and is based on consumer behavior and daily consumption [37,38], such a comparison is less obvious in case of waterpipe tobacco products.

Some authors have compared a waterpipe session with cigarette smoking on the basis of nicotine and/or HPHC metabolite concentrations: Neergaard et al. [39] estimated, on the basis of urinary nicotine and cotinine levels, that a waterpipe session corresponds to about two cigarettes per day, while Cobb et al. [40]) did not observe any difference in terms of peak plasma nicotine levels between a waterpipe session and a cigarette. In case of CO, Cobb et al. [40] observed almost a four-fold higher exposure (based on carboxyhemoglobin) in waterpipe tobacco users than in cigarette smokers. Alternatively—on the basis of the nicotine yield from a single waterpipe session and a 1R6F reference cigarette [41]—according to the present results, one waterpipe session corresponds to smoking <1 to 7 cigarettes. There is clearly a need for better understanding of the behavior of waterpipe products consumers in order to allow comparison of such products with other tobacco products.

On the basis of the evolution of yields between the different puff blocks of 35 puffs (see Table 4), it appears that, in some cases, the waterpipe tobacco is essentially exhausted before the end of the five blocks of 35 puffs recommended in the ISO standard [13], especially when considering nicotine yield. There is also possibly a difference in the temperature applied to the tobacco between the electrical heating system used in the ISO standard (280°C) and the commercial waterpipes and charcoals. This is also the case between the two commercial combinations used with the same waterpipe tobacco product. This difference was also observed visually at the end of the aerosol generation process, in terms of the appearance of the remaining waterpipe tobacco: Some samples were dry, while some others still had a wet appearance.

Table 4.

Yields of selected compounds in individual blocks of 35 puffs.

| Sample | Compound | Puffs 1–35 | Puffs 36–70 | Puffs 71–105 | Puffs 106–140 | Puffs 141–175 | Puffs 1−175 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1D1C1 | TCM (mg) | 1034 | 1194 | 1224 | 616 | 458 | 4526 |

| Nicotine (mg) | 0.76 | 1.02 | 0.96 | < 0.5 | < 0.5 | 2.74 | |

| Glycerol (mg) | 241.0 | 331.2 | 382.2 | 177.1 | 139.5 | 1271 | |

| T1D1C2 | TCM (mg) | 356 | 1208 | 742 | 376 | 145 | 2827 |

| Nicotine (mg) | 1.20 | 0.80 | < 0.5 | < 0.5 | < 0.5 | 2.00 | |

| Glycerol (mg) | 80.1 | 341.0 | 212.6 | 99.8 | 42.3 | 775.8 | |

| T1Electrical | TCM (mg) | 204 | 621 | 773 | 557 | 595 | 2750 |

| Nicotine (mg) | < 0.5 | 1.26 | 0.58 | < 0.5 | < 0.5 | 1.84 | |

| Glycerol (mg) | 26.5 | 166.8 | 267.4 | 131.1 | 206.9 | 798.7 |

4. Discussion

An ISO standard 22486 [13] has recently been published, providing the specifications for a waterpipe laboratory smoking machine together with ISO-related technical specifications for determining nicotine, TCM [42], and CO [43] yields in waterpipe tobacco aerosols. The use of an electrical heater (which heats the waterpipe tobacco up to 280℃), standardized tubing and glass bottle, and standardized puffing conditions is aimed at allowing comparison of quality among different waterpipe tobacco products by reducing the contribution of other factors (especially the different types of charcoals that can be used to heat the waterpipe tobacco) on the aerosol. The temperature applied to the waterpipe tobacco products as well as the puffing conditions were selected by the ISO working group to be close to real-use conditions, keeping in mind that no smoking machine regimen can represent all human smoking behaviors. The need for measuring the contribution of charcoal burning to the CO yield in waterpipe tobacco aerosols was also recognized with the development of a specific method for CO measurement [44].

For developing the ISO standard, it was necessary to use a standardized temperature for electrically heating waterpipe tobacco. This temperature is generally lower than those obtained with commercial charcoals, if one considers the aerosol yields in terms of TCM, nicotine, and glycerol.

It is obvious that the charcoals quality and characteristics used by waterpipe consumers do result in increased levels of some compounds in the waterpipe aerosols. In our study, which was limited to 25 HPHCs, we observed a systematic increase in CO and B[a]P levels in the aerosols generated with commercial waterpipes and charcoals, relative to those obtained with the analytical waterpipe smoking machine by using the same puffing conditions. This trend has previously been reported by other authors in case of metals, CO, PAHs, and selected volatile organic compounds [8,18,26]. This means that the yields of compounds in aerosols generated by using the analytical waterpipe smoking machine should also be complemented with analysis of the charcoal in order to derive a full estimate of the HPHC content in waterpipe aerosols. This need was recognized by the ISO working group in charge of developing standards for waterpipe products, leading to the development of a specific method for measurement of CO yields resulting from the glowing of charcoal [44].

Funding

The research described in this article was funded by Philip Morris Products SA.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Guy Jaccard: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Donatien Tafin Djoko: Validation, Writing - review & editing. Alexandra Korneliou: Software, Formal analysis, Writing - review & editing. Maxim Belushkin: Supervision, Writing - review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors report no declarations of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxrep.2020.10.007.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Rastam S., Eissenberg T., Ibrahim I., Ward K.D., Khalil R., Maziak W. Comparative analysis of waterpipe and cigarette suppression of abstinence and craving symptoms. Addict. Behav. 2011;36:555–559. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization, Advisory Note; 2015. Waterpipe Tobacco Smoking: Health Effect, Research Nees and Recommended Actions for Regulators. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Soulakova J.N., Pham T., Owens V.L., Crockett L.J. Prevalence and factors associated with use of hookah tobacco among young adults in the U.S. Addict. Behav. 2018;85:21–25. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jawad M., Cheeseman H., Brose L.S. Waterpipe tobacco smoking prevalence among young people in Great Britain, 2013-2016. Eur. J. Public Health. 2018;28:548–552. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckx223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Galimov A., El Shahawy O., Unger J.B., Masagutov R., Sussman S. Hookah use among Russian adolescents: prevalence and correlates. Addict. Behav. 2019;90:258–264. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shihadeh A., Azar S., Antonios C., Haddad A. Towards a topographical model of narghile water-pipe cafe smoking: a pilot study in a high socioeconomic status neighborhood of Beirut, Lebanon. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2004;79:75–82. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2004.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shihadeh A., Schubert J., Klaiany J., El Sabban M., Luch A., Saliba N.A. Toxicant content, physical properties and biological activity of waterpipe tobacco smoke and its tobacco-free alternatives. Tob. Control. 2015;24(Suppl. 1):i22–i30. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schubert J., Müller F.D., Schmidt R., Luch A., Schulz T.G. Waterpipe smoke: source of toxic and carcinogenic VOCs, phenols and heavy metals? Arch. Toxicol. 2015;89:2129–2139. doi: 10.1007/s00204-014-1372-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Al Rashidi M., Shihadeh A., Saliba N.A. Volatile aldehydes in the mainstream smoke of the narghile waterpipe. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2008;46:3546–3549. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2008.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schubert J., Heinke V., Bewersdorff J., Luch A., Schulz T.G. Waterpipe smoking: the role of humectants in the release of toxic carbonyls. Arch. Toxicol. 2012;86:1309–1316. doi: 10.1007/s00204-012-0884-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Al-Kazwini A.T., Said A.J., Sdepanian S. Compartmental analysis of metals in waterpipe smoking technique. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:153. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1373-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sepetdjian E., Abdul Halim R., Salman R., Jaroudi E., Shihadeh A., Saliba N.A. Phenolic compounds in particles of mainstream waterpipe smoke. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2013;15:1107–1112. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nts255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.ISO . 2019. ISO 22486, Water Pipe Tobacco Smoking Machine -- Definitions and Standard Conditions. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brinkman M.C., Kim H., Buehler S.S., Adetona A.M., Gordon S.M., Clark P.I. Evidence of compensation among waterpipe smokers using harm reduction components. Tob. Control. 2020;29:15–23. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Monzer B., Sepetdjian E., Saliba N., Shihadeh A. Charcoal emissions as a source of CO and carcinogenic PAH in mainstream narghile waterpipe smoke. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2008;46:2991–2995. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2008.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nguyen T., Hlangothi D., Martinez R.A., Jacob D., Anthony K., Nance H. Charcoal burning as a source of polyaromatic hydrocarbons in waterpipe smoking. J. Environ. Sci. Health B. 2013;48:1097–1102. doi: 10.1080/03601234.2013.824300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sepetdjian E., Saliba N., Shihadeh A. Carcinogenic PAH in waterpipe charcoal products. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2010;48:3242–3245. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2010.08.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elsayed Y., Dalibalta S., Abu-Farha N. Chemical analysis and potential health risks of hookah charcoal. Sci. Total Environ. 2016;569-579:262–268. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.06.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.ISO . 2013. ISO 10315, Cigarettes-Determination of Nicotine in Smoke Condensates-gas-chromatographic Method. [Google Scholar]

- 20.ISO . 2007. ISO 8454, Cigarettes-Determination of Carbon Monoxide in the Vapour Phase of Cigarette smoke-NDIR Method. [Google Scholar]

- 21.CORESTA . 2018. CRM 86, Determination of Select Carbonyls in Tobacco and Tobacco Products by UHHPLC-MS/MS. [Google Scholar]

- 22.ISO . 2016. ISO 19290, Cigarettes-Determination of Tobacco Specific Nitrosamines in Mainstream Cigarettes Smoke-method Using LC-MS/MS. [Google Scholar]

- 23.ISO . 2008. ISO 22303, Determination of Tobacco Specific Nitrosamines-method Using Buffer Extraction. [Google Scholar]

- 24.ISO . 2003. ISO 15154, Tobacco -- Determination of the Content of Reducing Carbohydrates -- Continuous-flow Analysis Method. [Google Scholar]

- 25.ISO . 2003. ISO 15152, Tobacco -- Determination of the Content of Total Alkaloids As Nicotine -- Continuous-flow Analysis Method. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saadawi R., Landero Figueroa J.A., Hanley T., Caruso J. The hookah series part 1: total metal analysis in hookah tobacco (narghile, shisha) - an initial study. Anal. Methods. 2012;4:3604–3611. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Piadé J.J., Jaccard G., Dolka C., Belushkin M., Wajrock S. Differences in cadmium transfer from tobacco to cigarette smoke, compared to arsenic or lead. Toxicol. Rep. 2015;2:12–26. doi: 10.1016/j.toxrep.2014.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lugon-Moulin N., Martin F., Krauss M.R., Ramey P.B., Rossi L. Cadmium concentration in tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum L.) from different countries and its relationship with other elements. Chemosphere. 2006;63:1074–1086. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2005.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gunduz I., Kondylis A., Jaccard G., Renaud J.M., Hofer R., Ruffieux L., Gadani F. Tobacco-specific N-nitrosamines NNN and NNK levels in cigarette brands between 2000 and 2014. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2016;76:113–120. doi: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2016.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oldham M.J., Lion K.E., III, Phillips D.J., Morton M.J., Lusso M.F., Harris E.A., Jordan J.L., Franke J.E., Strickland J.A. Variability of TSNA in U.S. Tobacco and moist smokeless tobacco products. Toxicol. Rep. 2020;7:752–758. doi: 10.1016/j.toxrep.2020.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.El Hourani M., Salman R., Talih S., Saliba N.A., Shihadeh A. Does the bubbler scrub key toxicants from waterpipe tobacco smoke?: measurements and modeling of CO, NO, PAH, nicotine, and particulate matter uptake. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2020;33:727–730. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrestox.9b00521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Piadé J.J., Wajrock S., Jaccard G., Janeke G. Formation of mainstream cigarette smoke constituents prioritized by the World Health Organization - Yield patterns observed in market surveys, clustering and inverse correlations. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2013;55:329–347. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2013.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baker R.R. The generation of formaldehyde in cigarettes-Overview and recent experiments. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2006;44:1799–1822. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2006.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jaccard G., Kondylis A., Gunduz I., Pijnenburg J., Belushkin M. Investigation and comparison of the transfer of TSNA from tobacco to cigarette mainstream smoke and to the aerosol of a heated tobacco product, THS2.2. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2018;97:103–109. doi: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2018.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Khabour O.F., Alzoubi K.H., Al-Sheyab N.A., Azab M.A., Massadeh A.M., Alomary A.A., Eissenberg T.E. Plasma and saliva levels of three metals in waterpipe smokers: a case control study. Inhal. Toxicol. 2018;30:224–228. doi: 10.1080/08958378.2018.1500663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schlage W., Titz B., Iskandar A., Poussin C., van der Toorn M., Wong E.T., Pratte P., Maeder S., Schaller J.P., Pospisil P., Boue S., Vuillaume G., Leroy P., Martin F., Ivanov N.V., Peitsch M.C., Hoeng J. Comparing the preclinical risk profile of inhalable candidate and potential candidate modified risk tobacco products: a bridging use case. Toxicol. Rep. 2020;7:1187–1206. doi: 10.1016/j.toxrep.2020.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gee J., Prasad K., Slayford S., Gray A., Nother K., Cunningham A., Mavropoulou E., Proctor C. Assessment of tobacco heating product THP1.0. Part 8: study to determine puffing topography, mouth level exposure and consumption among Japanese users. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2018;93:84–91. doi: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2017.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Haziza C., de La Bourdonnaye G., Skiada D., Ancerewicz J., Baker G., Picavet P., Ludicke F. Evaluation of the Tobacco Heating System 2.2. Part 8: 5-Day randomized reduced exposure clinical study in Poland. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2016;81(Suppl. 2):S139–S150. doi: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2016.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Neergaard J., Singh P., Job J., Montgomery S. Waterpipe smoking and nicotine exposure: a review of the current evidence. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2007;9:987–994. doi: 10.1080/14622200701591591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cobb C.O., Shihadeh A., Weaver M.F., Eissenberg T. Waterpipe tobacco smoking and cigarette smoking: a direct comparison of toxicant exposure and subjective effects. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2011;13:78–87. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jaccard G., Djoko D.T., Korneliou A., Stabbert R., Belushkin M., Esposito M. Mainstream smoke constituents and in vitro toxicity comparative analysis of 3R4F and 1R6F reference cigarettes. Toxicol. Rep. 2019;6:222–231. doi: 10.1016/j.toxrep.2019.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.ISO . 2019. ISO/TS 22487, Water Pipe Tobacco — Determination of Total Collected Matter and Nicotine Using a Water Pipe Tobacco Smoking Machine. [Google Scholar]

- 43.ISO . 2019. ISO/TS 22491, Water Pipe Tobacco — Determination of Carbon Monoxide in the Vapour Phase of Water Pipe Tobacco Smoke — NDIR Method. [Google Scholar]

- 44.ISO . 2019. ISO/TS 22492, Water Pipe Tobacco Products — Determination of Carbon Monoxide Emission of Glowing Water Pipe Charcoal — NDIR Method. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.