Abstract

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a novel disease caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV)-2 virus that was first detected in December of 2019 in Wuhan, China, and has rapidly spread worldwide. The search for a suitable vaccine as well as effective therapeutics for the treatment of COVID-19 is underway. Drug repurposing screens provide a useful and effective solution for identifying potential therapeutics against SARS-CoV-2. For example, the experimental drug remdesivir, originally developed for Ebola virus infections, has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration as an emergency use treatment of COVID-19. However, the efficacy and toxicity of this drug need further improvements. In this review, we discuss recent findings on the pathology of coronaviruses and the drug targets for the treatment of COVID-19. Both SARS-CoV-2–specific inhibitors and broad-spectrum anticoronavirus drugs against SARS-CoV, Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus, and SARS-CoV-2 will be valuable additions to the anti–SARS-CoV-2 armament. A multitarget treatment approach with synergistic drug combinations containing different mechanisms of action may be a practical therapeutic strategy for the treatment of severe COVID-19.

SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT

Understanding the biology and pathology of RNA viruses is critical to accomplish the challenging task of developing vaccines and therapeutics against SARS-CoV-2. This review highlights the anti–SARS-CoV-2 drug targets and therapeutic development strategies for COVID-19 treatment.

Introduction

Coronaviruses are enveloped, single-stranded, positive-sensed RNA viruses belonging to the family Coronaviridae with genomes ranging from 26 to 32 kb in length. Several known strains of coronaviruses such as OC43, HKU, 229E5, and NL63 are pathogenic to humans and associated with mild common cold symptoms (D. E. Gordon et al., preprint, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.22.002386). However, in the past two decades, three notable coronaviruses of the pandemic scale have emerged and produced severe clinical symptoms, including acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). In 2002, the coronavirus strain SARS-CoV, named for causing severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), originated in the Guangdong province of China (Drosten et al., 2003). In 2012, another coronavirus with reported clinical similarity to SARS-CoV was first detected in Saudi Arabia and later identified as Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) (Zaki et al., 2012). SARS-CoV resulted in more than 8000 human infections and 774 deaths in 37 countries between 2002 and 2003 (Lu et al., 2020) before disappearing from the population due to stringent quarantine precautions. MERS-CoV infections, however, are a continued threat to global health. Since September 2012, there have been 2494 laboratory-confirmed cases and 858 fatalities, including 38 deaths after a single introduction into South Korea (Lu et al., 2020). Despite significant efforts, vaccines and effective drugs for the prevention or treatment of either SARS-CoV or MERS-CoV are still not available.

In December 2019, a new virus initially called the 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) emerged in the city of Wuhan, China. It produced clinical symptoms that included fever, dry cough, dyspnea, headache, pneumonia with potentially progressive respiratory failure owing to alveolar damage, and even death (Zhou et al., 2020). Because sequence analysis of this novel coronavirus identified it as closely related to the SARS-CoV strain from 2002 to 2003, the World Health Organization renamed the new virus as SARS-CoV-2 in February 2020. The disease caused by SARS-CoV-2 has been named coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Like SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV infections, ARDS can be induced in severe cases of COVID-19. ARDS is largely mediated through the significant release of proinflammatory cytokines that results in a cytokine storm, which likely triggers multiorgan failure and contributes to increased death rates (Li et al., 2020). Dependent on several factors such as preexisting conditions and the immune response, severe disease can precipitate pathophysiological effects on the heart, kidney, liver, and central nervous system. Examples include myocardial injury, arrhythmias, increased risk of myocardial infarction, liver dysfunction, kidney failure, neurologic complications such as ataxia, seizures, neuralgia, acute cerebrovascular disease, and encephalopathy (see Zaim et al. (2020) for an in depth review). In addition, SARS-CoV-2 may have tropism toward tissues other than the lungs, which could contribute to disease exacerbation (Puelles et al., 2020).

Genome sequencing and phylogenetic analyses have confirmed that SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, and SARS-CoV-2 are all zoonotic diseases that originated from bat coronaviruses leading to infections in humans either directly or indirectly through an intermediate host (Lu et al., 2020). Unfortunately, predicting the zoonotic potential of newly detected viruses has been severely hindered by a lack of functional data for viral sequences in these animals (Letko et al., 2020). Unlike SARS-CoV or MERS-CoV, where transmissions mainly occur in a nosocomial manner, SARS-CoV-2 appears to spread more efficiently, as viral shedding may also occur in asymptomatic individuals prior to the onset of symptoms. Asymptomatic transmission increases its pandemic potential severalfold (Tu et al., 2020). Indeed, COVID-19 was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization on March 11, 2020, because there was a dramatic and exponential increase in the number of cases and deaths associated with the disease within several months. Currently, close to the end of June 2020, there are over 10 million cases worldwide with over 500,000 deaths. Treatment options for COVID-19 are limited while several vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 are in the works. On April 29, 2020, the US National Institutes of Health announced that remdesivir, an experimental drug originally developed as an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRP) inhibitor against Ebola virus (EBOV), showed positive efficacy in a clinical phase 3 trial for COVID-19. Hospitalized patients with COVID-19 treated with remdesivir shortened the time to recovery by 31% (from 15 to 11 days). On May 1, 2020, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) granted emergency use authorization of remdesivir for treatment of COVID-19, while a formal approval is still pending.

Overview of SARS-CoV-2 Genome and Protein Constituents

SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, and SARS-CoV-2 belong to the Betacoronavirus genus, whose genomes typically contain 5′-methylated caps at the N terminus and a 3′-poly-A tail at the C terminus with a highly conserved order of genes related to replication/transcription and structural components. The replication and transcription–related gene is translated into two large nonstructural polyproteins by two distinct but overlapping open reading frames translated by ribosomal frameshifting (Tu et al., 2020). The overlapping open reading frame, composing two-thirds of the coronavirus genome, encodes the large replicase polyproteins 1a and 1b, which are cleaved by papain-like cysteine protease and 3C-like serine protease (3CLpro, also called Mpro). This cleavage produces 16 nonstructural proteins (NSPs) including important enzymes involved in the transcription and replication of coronaviruses such as RdRP, helicase (Nsp13), and exonuclease (Nsp14) (Tang et al., 2020). The 3′ one-third of the coronavirus genome is translated from subgenomic RNAs and encodes the structural proteins spike (S), envelope (E), and membrane (M) that constitute the viral coat and the nucleocapsid (N) protein that packages the viral genome (Tu et al., 2020). These structural proteins are essential for virus–host cell binding and virus assembly. Upon translation, the S, E, and M structural proteins are inserted into the rough endoplasmic reticulum to travel along the secretory pathway to the endoplasmic reticulum–Golgi apparatus intermediate compartment or coronavirus particle assembly and subsequent release from the cell via exocytosis (Tang et al., 2020).

Viral Entry Through the Binding of SARS-CoV-2 Spike Proteins to Angiotensin Converting Enzyme 2 Receptor

The S proteins of SARS-CoV, required for viral entry into the host target cell, are synthesized as inactive precursors and become activated only upon proteolysis (Gierer et al., 2013). The S protein has two functional domains called S1 and S2. S1 contains an N-terminal domain and a receptor-binding domain (RBD). The receptor-binding motif (RBM) is located within the carboxy-terminal half of the RBD and contains residues that enable attachment of the S protein to a host cell receptor (Letko et al., 2020). The S2 subunit drives the fusion of viral and host membrane subsequent to cleavage, or “priming,” by cellular proteases. SARS-CoV is known to gain entry into permissive host cells through interactions of the SARS-CoV S protein RBD with the cell surface receptor angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) 2 (Wang et al., 2008). ACE2 is a negative regulator of the renin-angiotensin system and counterbalances the function of ACE, thereby maintaining blood pressure homeostasis (Kuba et al., 2005). It was shown in animal models that ACE2 promotes anti-inflammation, antifibrosis, and vasodilation, whereas ACE promotes proinflammation, fibrosis, vasoconstriction, and severe lung injury (Kuba et al., 2005). Furthermore, through S protein binding, SARS-CoV downregulates ACE2 receptor, and therefore this process not only leads to viral entry but also potentially contributes to severe lung injury, as the ACE2 pathway has protective functions in many organs. Since 83% of ACE2-expressing cells are alveolar epithelial type II cells and these cells contain high levels of multiple viral process-related genes, including regulatory genes for viral processes, viral life cycle, viral assembly, and viral genome replication, they can facilitate coronaviral replication in the lung (Y. Zhao et al., preprint, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.01.26.919985). Sequence analysis showed that SARS-CoV-2 genome is very similar to SARS-CoV with a only a few differences in their complement of 3′ open reading frames that do not encode structural proteins (D. E. Gordon et al., preprint, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.22.002386). Specifically, the S proteins of SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV share 76.5% identity in amino acid sequences and have a high degree of homology (Xu et al., 2020b). SARS-CoV-2 also uses ACE2 as a cellular entry receptor because, in cells that are otherwise not susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 infection, overexpressing human or bat ACE2 mediates SARS-CoV-2 infection and replication (Hoffmann et al., 2020a; Zhou et al., 2020). In addition, SARS-CoV-2 does not use other receptors such as dipeptidyl peptidase 4, used by MERS-CoV, or the human aminopeptidase N used by human coronavirus strain 229E (Ou et al., 2020; Zhou et al., 2020). Several groups have now identified the RBD in SARS-CoV-2 and have confirmed by biochemical analyses as well as crystal structure prediction analyses that this domain binds strongly to both human and bat ACE2 receptor with a binding affinity significantly higher than that of SARS-CoV to the ACE2 receptor (Tai et al., 2020; Wan et al., 2020; Wrapp et al., 2020; Xu et al., 2020b). There has been much speculation that the high affinity binding of SARS-CoV-2 to ACE2 could mediate the increased potential for transmissibility and severity of infection. For instance, the coronavirus strain NL63 also uses the same ACE2 receptor for entry into the host cell as SARS-CoV, but the virus entry and outcome are vastly different, with SARS resulting in severe respiratory distress and NL63 resulting in only a mild respiratory infection (Mathewson et al., 2008). This led the authors to suggest that a lower-affinity interaction with NL63 for ACE2 may partially explain the different pathologic consequences of infection. It has been speculated that in addition to the ACE2 receptor, SARS-CoV-2 could employ other receptors for host cell entry. For example, the S protein of SARS-CoV-2 has a conserved RGD motif known to bind integrins, which is not found in other coronaviruses (Sigrist et al., 2020). This motif lies within the RBD of the S proteins of SARS-CoV-2, close to the ACE2 receptor-binding region (Sigrist et al., 2020). SARS-CoV-2 S protein can also interact with sialic acid receptors of the cells in the upper airways similar to MERS-CoV (E. Milanetti et al., preprint, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.24.006197). Although the functional importance of integrins or sialic acid receptors in mediating SARS-CoV-2 S protein entry remains to be determined, these may potentially increase cell tropism, viral pathogenicity, and transmission of SARS-CoV-2.

SARS-CoV-2 Has Multiple Viral Entry Mechanisms

In general, coronaviruses deliver their genomes to the host cytosol by two known methods: directly fusing with the plasma membrane at the cell surface in a pH-independent manner or utilizing the host cell’s endocytic machinery in which the endocytosed virions are subjected to an activation step in the endosome. Endocytic activation is typically mediated by the acidic endosomal pH, resulting in the fusion of the viral and endosomal membranes and release of the viral genome into the cytosol (Wang et al., 2008). Fusion with the cell membrane requires that the S2 domain of the S protein be primed by cellular proteases at the S’ site. SARS-CoV is known to be able to enter host cells by directly fusing with the host membrane as well as through the endosomal pathway via cathepsin B and L (Matsuyama et al., 2010). SARS-CoV can also use the cell surface protease transmembrane protease serine type 2 (TMPRSS2) that belongs to the type II transmembrane serine protease family. Although SARS-CoV utilizes both host cell entry pathways, it appears that the TMPRSS2 pathway is the major route of infection of SARS-CoV in the lungs. However, in the absence of TMPRSS2, SARS-CoV can also employ the endosomal late entry route for infection, as SARS-CoV viral spread is still detected in the alveoli of TMPRSS2 knockout mice (Iwata-Yoshikawa et al., 2019). Unlike other soluble serine proteases, TMPRSS2 is anchored on the plasma membrane and localized with ACE2 receptors on the surface of airway epithelial cells (Shulla et al., 2011). This colocalization makes the lungs particularly susceptible to infection. TMPRSS2 cleavage of S protein might also promote viral spread and pathogenesis by diminishing viral recognition by neutralizing antibodies. The cleavage of S protein can result in shedding of SARS S protein fragments that could act as antibody decoys (Glowacka et al., 2011). Although TMPRSS2 affects the entry of virus but not the other phases of virus replication, only a small amount of S protein needs to be cleaved to enable viral or cell-cell membrane fusion, even when minute or undetectable amounts of ACE2 is available (Shulla et al., 2011). In keeping with this, the expression and distribution of TMPRSS2, but not ACE2, correlates with SARS-CoV infection in the lungs. SARS-CoV studies have shown that TMPRSS2 cleaves the S protein after receptor binding, which causes conformational changes that expose the S’ cleavage site (Glowacka et al., 2011). This confers a great advantage to the viral protein by protecting the activating cleavage site from premature proteolysis and yet ensuring that efficient cleavage occurs upon binding to the receptor on target cells (Shulla et al., 2011). Similarly, in the case of SARS-CoV-2, the host cell TMPRSS2 primes the S protein and enhances entry and infection (Hoffmann et al., 2020a; Matsuyama et al., 2020). SARS-CoV-2 may also use other host proteases such as trypsin for S protein activation (Ou et al., 2020). Similar to SARS-CoV, SARS-CoV-2 can also enter host cells through the endosomal pathway via cathepsins (Hoffmann et al., 2020a; Ou et al., 2020). Unlike SARS-CoV, the S protein of SARS-CoV-2 has a furin cleavage site at the S1/S2 boundary similar to MERS-CoV (Hoffmann et al., 2020a; Walls et al., 2020), which likely sensitizes S proteins to the subsequent activating proteolysis occurring on susceptible target cells, facilitates virus entry and infection, and potentially increases viral transmissibility (Qing and Gallagher, 2020). Since SARS-CoV-2 can be activated by an extensive range of proteases, and given that a varied number of proteases exist on the cell surface of different cell types, SARS-CoV-2 has the capacity to infect a wide range of cells (Tang et al., 2020). Thus, it is an opportunistic virus that can use multiple pathways of host cell entry and infection. It is conceivable that successful treatment of COVID-19 may require a cocktail of drugs that target multiple mechanisms of action as historically seen for the treatment of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection; see the review by Maeda et al. (2019).

Drug Development Strategies

For negative-sense RNA viruses, approved therapies are currently available only for rabies virus, respiratory syncytial virus, and influenza virus (Hoenen et al., 2019). Since there are many functional similarities between SARS-CoV, SARS-CoV-2, and MERS-CoV, it is reasonable to screen drugs that were even moderately effective against SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV for SARS-CoV-2. These broad-spectrum anticoronavirus drugs could also be used against future emerging coronavirus infections. In particular, any such drugs that have an IC50 in the low nanomolar range (preferably less than 100 nM) with high efficacy in inhibiting viral infection in vitro would be most advantageous. Drug repurposing has been used in response to emerging infectious diseases to rapidly identify potential therapeutics. If FDA-approved drugs currently on the market for other diseases demonstrate anti–SARS-CoV-2 activity, they could be repurposed for COVID-19 treatment. Several groups have identified compounds with anti–SARS-CoV-2 activity by repurposing select FDA-approved drugs (Choy et al., 2020; Jeon et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020b). In addition, high-throughput drug repurposing screens have also been successfully used to identify such compounds (Table 1). The National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences also provides an online open science data portal for COVID-19 drug repurposing (https://ncats.nih.gov/expertise/covid19-open-data-portal; K. R. Brimacombe et al., preprint, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.04.135046).

TABLE 1.

High-throughput drug repurposing screens against SARS-CoV-2

| Cell line | Assay type | Strain of SARS-CoV-2 | Library screened | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caco-2 | CPE | Unspecified | 5632 compounds, including 3488 compounds that have undergone clinical investigationsa | B. Ellinger et al., preprint, DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-23951/v/v1 |

| Vero E6 | Primary screen: CPE Follow-up: N protein immuno-fluorescence |

HKU-001a in 1’ screen USA-WA1/2020 for follow-up | LOPAC 1280 and ReFRAME librarya | L. Riva et al., preprint, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.16.044016 |

| Vero E6 | CPE | BavPat1 strain | Prestwick Chemical Library (1520 approved drugs) | F. Touret et al., preprint, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.03.023846 |

CPE, cytopathic effect.

Proprietary library.

For compound screening with large-scale libraries and molecular target-based assays, biosafety level (BSL)-2 laboratories are commonly used. These assays take longer to develop but are usually without risk of infectivity to humans and are capable of higher throughput than live SARS-CoV-2 virus assays requiring BSL-3 facilities. However, the efficacy of active compounds identified from such high-throughput screening needs to be confirmed with live SARS-CoV-2 virus assays done in the BSL-3 environment. For example, virus pseudoparticles that contain viral structural proteins without the viral genome can be used to assay viral entry mechanisms. Cell lines expressing viral replicons that contain portions of the viral genome with reporter genes but without viral structure genes can also be used to assay viral replication mechanisms. These nonviral assays used for viral entry or replication are not infectious and can be used in a BSL-2 facility for screening large compound collections. This strategy has been used to screen compounds for BSL-3/4 viruses such as EBOV (Tscherne et al., 2010; Kouznetsova et al., 2014), Lassa virus (Cubitt et al., 2020), SARS, and MERS-CoV (de Wilde et al., 2014; Dyall et al., 2014). Recently, Letko et al. (2020) showed chimeric S proteins containing RBD of SARS-CoV-2 can confer receptor specificity to the full S protein sequence. This approach of nonconventional pseudotyping method is cost effective and can provide a faster way to screen viral-host interactions.

Therapeutic targets for COVID-19 can be directed toward the SARS-CoV-2 virus and its proteins or the host cell targets. Prevention of virus-host associations can fall in either of the two categories. Drugs targeting viral proteins have a major advantage, as they could potentially have higher specificity against the virus while having minimal adverse effects on humans. However, drug resistance may develop rapidly after treatment, particularly in RNA viruses where mutations occur frequently. Conversely, therapeutics targeting host cells may slow the development of drug resistance, as mutations in host cells are relatively rare (Hoenen et al., 2019). Importantly, drugs targeting host cells have greater potential for adverse effects. Possible treatment options under investigation for the prevention and control of SARS-CoV-2 infections in both categories are discussed below.

SARS-CoV-2 Viral Entry Inhibitors

Antibodies.

Neutralizing antibodies can be used to prevent viral cell surface receptor binding to block viral entry. After viral entry, the viral replication cycle concludes in the assembly and budding of new viral progeny at the host cell surface (Murin et al., 2019). These processes can be disrupted by neutralizing antibodies that bind to the viral glycoprotein to block viral egress (Murin et al., 2019). Thus, neutralizing antibodies can prevent viral entry as well as viral release, thereby blocking the infection of neighboring cells. In vitro neutralization assays followed by in vivo protection in an animal model was the standard workflow for choosing neutralizing antibodies against filoviruses such as EBOV, which emerged as an outbreak in 2014 in West Africa (Saphire et al., 2018). A glycoprotein-targeting cocktail of antibodies rather than a single antibody design against EBOV was shown to be superior and is currently being used in areas of outbreaks (Hoenen et al., 2019). Similarly, several anti-influenza monoclonal antibodies are currently in various stages of clinical development, and most are directed toward the viral hemagglutinin glycoprotein (Corti et al., 2017). For both EBOV and influenza, some broadly reactive antibodies lacking in vitro neutralizing activity have shown in vivo efficacy under prophylactic settings, and thus, there is not a precise correlation between in vitro activities and in vivo protection (Corti et al., 2017; Tian et al., 2020). Neutralizing antibodies designed against SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV could potentially be effective against SARS-CoV-2. Several monoclonal antibodies targeting S protein of SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV have shown promising results in neutralizing infection in both in vitro and rodent models (Shanmugaraj et al., 2020). Since the structures of SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, and MERS-CoV S protein and monoclonal antibody interaction sites have been determined, neutralizing antibodies against S protein of SARS-CoV-2 promises to be a viable therapeutic option.

Convalescent plasma therapy using plasma from patients recovered from COVID-19 to treat severe cases of COVID-19 has shown positive results. Convalescent plasma contains neutralizing antibodies specifically against the SARS-CoV-2 virus and confers passive immunity to the recipient, thereby improving clinical outcomes when used prophylactically and in infected patients (Casadevall and Pirofski, 2020). RBD-specific monoclonal antibodies derived from SARS-CoV-2–infected individuals was shown to have neutralizing activities against both pseudoviruses bearing the S protein as well as live SARS-CoV-2 viruses (B. Ju et al., preprint, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.21.990770). Treatment with convalescent plasma was shown to be successful in a small cohort of patients (Duan et al., 2020; Shen et al., 2020). Clinical trials are currently underway to determine whether COVID-19 convalescent plasma or “hyperimmune plasma” might be an effective treatment therapy for COVID-19. The Takeda Pharmaceutical Company has announced investigation into a new plasma derived therapy named TAK-888 that involves removing plasma from COVID-19 survivors and extracting coronavirus-specific antibodies to stimulate a potent immune response against SARS-CoV-2 in infected patients (Barlow et al., 2020).

Proteins, Peptides, Small Molecule Compounds, and Drugs.

Viral entry can also be blocked by proteins, peptides, or small molecule compounds that bind to the viral S protein, thereby preventing the interaction of virus and host membrane. Recombinant soluble ACE2, which lacks the membrane anchor and can circulate in small amounts in the blood, can act as a decoy to bind SARS-CoV-2 S proteins and thus prevent viral entry (C. Lei et al., preprint, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.02.01.929976). Clinical grade human recombinant soluble ACE2 was shown to successfully inhibit SARS-CoV-2 infection in engineered human blood vessel organoids and human kidney organoids (Monteil et al., 2020). Studies also show that soluble human ACE2 can significantly decrease SARS-CoV-2 viral entry (Ou et al., 2020) and recombinant proteins designed against the RBD of S protein of SARS-CoV-2 can successfully block entry of virus into cells (Tai et al., 2020; G. Zhang et al., preprint, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.19.999318). Another class of proteins that may be useful in blocking viral entry into cells are lectins, which bind specific carbohydrate structures but lack intrinsic enzymatic activity (Mitchell et al., 2017). Lectins may inhibit viral entry and subsequent replication by interacting with coronavirus S proteins that are heavily glycosylated (Mitchell et al., 2017). Griffithsin is a lectin protein isolated from marine red algae and has proven antiviral properties (Mori et al., 2005). Griffithsin can potently inhibit viral entry by binding to the S glycoprotein and prevent SARS-CoV infection both in vitro and in vivo with minimal cytotoxic effects (O’Keefe et al., 2010). Similarly, griffithsin was shown to inhibit MERS-CoV infectivity and production in vitro with no significant cytotoxicity (Millet et al., 2016). Another lectin protein known as Urtica dioica agglutinin (UDA) was shown to significantly decrease mortality rates in a mouse model of SARS-CoV infection and was able to impede viral entry and replication (Day et al., 2009; Kumaki et al., 2011). However, UDA requires higher concentrations than griffithsin to achieve similar inhibitions of viral infections (O’Keefe et al., 2010), and high doses of UDA have toxic effects in mice (Kumaki et al., 2011). Based on these in vitro as well as preclinical results, griffithsin may well prove to be an effective SARS-CoV-2 entry inhibitor.

Peptides can also be designed against the highly conserved heptad repeat region located in the S2 subunit of the S protein, which can interfere with viral and host cellular membrane fusion. A lipopeptide, EK1C4, exhibited highly potent inhibitory activity against SARS-CoV-2 S protein–mediated membrane fusion in vitro and in vivo (Xia et al., 2020). Small molecules that block the binding of S protein to ACE2 can also be investigated as therapeutics for COVID-19 treatment. For example, the cysteine-cysteine chemokine receptor 5 antagonist maraviroc, which was approved in 2007 for the treatment of HIV infections, blocks HIV from binding to its coreceptor cysteine-cysteine chemokine receptor 5. Thus, a specific ACE2 inhibitor may be developed that blocks the binding of SARS-CoV-2 S protein to ACE2.

Additionally, the inhibitors of host cell proteases such as TMPRSS2, furin, and cathepsin that prime viral structure proteins for membrane fusion may also prevent SARS-CoV-2 entry. Developing these types of inhibitors as therapeutics may present challenges due to differentially expressed proteases in different tissues. Therefore, developing a broad-spectrum protease inhibitor against SARS-CoV-2 might be beneficial. For example, the TMPRSS2 inhibitor camostat mesylate can block the entry of SARS-CoV-2 into Calu-3 human lung epithelial cells (Hoffmann et al., 2020a), but a combination of camostat mesylate and cathepsin B/L inhibitor E-64d is required to completely block viral entry into Caco-2 cells (Hoffmann et al., 2020a). Nafamostat is another example of a serine protease inhibitor that can inhibit SARS-CoV-2 entry and infection (Hoffmann et al., 2020b; Wang et al., 2020a). However, compared with camostat mesylate, nafamostat blocks viral entry and replication with significantly greater efficacy (Hoffmann et al., 2020b; J. H. Shrimp et al., preprint, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.23.167544). Nafamostat, approved as a treatment of pancreatitis in Japan and Germany with no major adverse effects, may also have anti-inflammatory properties that could aid patients with COVID-19 (Hoffmann et al., 2020b); clinical trials will determine its suitability as a COVID-19 therapeutic (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Clinical therapies for COVID-19

| Compound/treatment | Target | Phase | ClinicalTrials.gov identifier | Approved for other clinical treatment | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Camostat mesilate | Serine proteases, e.g., TMPRSS2 | Phase 1/2 | NCT04321096 | Acute pancreatitis (Japan) | Ongoing |

| Chlorpromazine | Clathrin-mediated endocytosis | Phase 1/2 | NCT04354805 | Schizophrenia, manic depression, nausea, anxiety | Not yet recruiting |

| Phase 3 | NCT04366739 | Not yet recruiting | |||

| Ciclesonide, an inhaled corticosteroid | Viral nonstructural protein 15 encoding an endonuclease and host process | Phase 2 | NCT04330586 | Asthma and allergic rhinitis (Schaffner and Skoner, 2009) | Not yet recruiting |

| Favipiravir (Avigan) with tocilizumab | RdRp | Not applicable | NCT04310228 | Influenza (Japan) | Ongoing |

| IL-6 | |||||

| Hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine | Antiviral properties unclear | Various | Multiple | Malaria, autoimmune diseases (e.g., lupus, rheumatoid arthritis) | Varies |

| Interferon-α1b nasal drops | Host immune response to virus | Phase 3 | NCT04320238 | None | Ongoing |

| Ivermectin | Viral transport into host nucleus | Varies | Multiple | Antiparasitic | Ongoing |

| Lopinavir + ritonavir (Kaletra) | 3CLpro | Phase 4 | NCT04252885 | HIV | Ongoing; preliminary results show no benefit beyond standard care (Baden and Rubin, 2020) |

| Lopinavir-ritonavir + ribavirin and interferon beta-1b | 3CLpro, viral polymerase, host immune response to virus | Phase 2 | NCT04276688 | HIV | Completed; significant improvement in outcomes (Hung et al., 2020) |

| Nafamostat | Serine protease | Phase 1 | NCT04352400 | Pancreatitis (Japan and Germany) | Not yet recruiting |

| Niclosamide | Viral and host processes | Phase 2 and 3 | NCT04345419 | Anthelminthic drug | Not yet recruiting |

| Nitazoxanide | Viral and host processes | Various | Multiple | Antiparasitic drug | Ongoing |

| Remdesivir | RdRp | Phase 3 | NCT04257656 | HIV | Terminated |

| NCT04252664 | Terminated | ||||

| NCT04292899 | Ongoing | ||||

| NCT04280705 | Ongoing | ||||

| Tocilizumab or sarilumaub | Human mAb that inhibits the IL-6 pathway by binding and blocking the IL-6 receptor | Various | Multiple | Multiple, including chimeric antigen receptor T cell–induced cytokine release syndrome, other autoimmune conditions (Barlow et al., 2020) | Ongoing |

| Umifenovir (Arbidol) | Viral membrane fusion of influenza a and b | Phase 4 | NCT04260594 | Influenza (Russia and China) | Not yet recruiting |

Viral entry may also be inhibited by umifenovir (also known as arbidol), which is approved for the treatment of influenza in Russia and China. Arbidol potently blocks SARS-CoV-2 entry into cells and inhibits postentry stages of infection (Wang et al., 2020b). The lower EC50 value of 4.11 μM against SARS-CoV-2 compared with influenza viruses gives arbidol the potential to be a clinically effective therapeutic against SARS-CoV-2 (Wang et al., 2020b). One clinical trial is set to determine the effectiveness of arbidol for the treatment of COVID-19–induced pneumonia (Table 2) and several others as a combination therapy. In addition, chlorpromazine, an FDA-approved antipsychotic and clathrin-dependent endocytosis inhibitor, also has anti–SARS-CoV-2 activity in vitro (M. Plaze et al., preprint, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.05.079608) and is currently under investigation as a potential therapeutic for COVID-19 (Table 2).

Viral Replication Inhibitors

Inhibitors of viral nucleic acid synthesis are the best represented class of antiviral drugs that suppress viral replication in host cells (Hoenen et al., 2019). The most successful 3CLpro inhibitor is lopinavir, a protease inhibitor used to treat HIV infections that is usually marketed as a ritonavir-boosted form (lopinavir-ritonavir) (Zumla et al., 2016). Preliminary in vitro studies with ritonavir on SARS-CoV-2 infection have not shown much promise (Choy et al., 2020). However, there are clinical trials underway to test the efficacy of this drug in humans (Table 2). Specifically repurposing any inhibitors designed against SARS-CoV or MERS-CoV 3CLpro for SARS-CoV-2 may prove challenging. Although there is a high degree of sequence conservation in the active sites of SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV 3CLpro enzymes, most SARS-CoV 3CLpro inhibitors are inactive against MERS-CoV, indicating other important structural differences (Needle et al., 2015).

RdRP is another target for SARS-CoV-2 drug development. The sequences encoding the structure of RdRP in SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, and SARS-CoV2 were found to be remarkably similar (Morse et al., 2020). Several RdRP inhibitors originally developed for other viruses are in active clinical trials to treat COVID-19 infections (Table 2). Remdesivir, a prodrug of an adenosine analog, was originally developed for the treatment of EBOV and has broad-spectrum antiviral activities against RNA viruses. Remdesivir successfully improved outcomes when used prophylactically and therapeutically in animal models of MERS-CoV (de Wit et al., 2020) as well as SARS (Sheahan et al., 2017). Treatment with remdesivir during early infection also showed significant clinical benefits in nonhuman primates infected with SARS-CoV-2 (Williamson et al., 2020). In patients with COVID-19, clinical improvements without adverse effects were noted in patients treated with remdesivir on a compassionate-use basis (Grein et al., 2020). In a randomized, controlled trial known as the Adaptive COVID-19 Treatment Trial, patients with COVID-19 who received remdesivir had significantly shorter recovery and mortality rates with no serious adverse events (Beigel et al., 2020). Due to these preliminary reports, FDA recently granted remdesivir emergency use authorization for the treatment of severely ill COVID-19 patients.

Other RdRP inhibitors include favipiravir and ribavirin. Favipiravir, a prodrug guanosine analog, is approved for the treatment of influenza in Japan and China. Favipiravir is not reported to have significant adverse effects; however, it may increase the risk for teratogenicity and embryotoxicity (Furuta et al., 2017). Ribavirin, another guanosine analog prodrug, is used for the treatment of severe respiratory syncytial virus infection, hepatitis C viral infection, and viral hemorrhagic fevers (Zumla et al., 2016; Tu et al., 2020). However, when used as a treatment for SARS-CoV infection in both preclinical (Day et al., 2009) and clinical settings (Stockman et al., 2006), ribavirin did not improve outcomes but instead had adverse effects. In addition, of these three drugs, only remdesivir has shown potent inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 infection in vitro (Choy et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020a). Therefore, pursuing specific SARS-CoV-2 RdRP inhibitors is a valid approach for COVID-19 drug development, but the efficacy and toxicities of these drugs will need to be closely scrutinized in clinical trials.

Recently, ivermectin was shown to potently inhibit SARS-CoV-2 in vitro with a single treatment (Caly et al., 2020). Ivermectin is an FDA-approved drug for the treatment of parasitic infections. However, its suitability as a COVID-19 treatment is currently being examined in several clinical trials, including one that will test asymptomatic patients (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04407507).

Four additional enzymes specific to SARS-CoV-2—helicase (Nsp13), 3′-5′ exonuclease (Nsp14), uridine-specific endoribonuclease (Nsp15), and RNA-cap methyltransferase (Nsp16)—may be considered as key targets for drug discovery (Gordon et al., 2020). In single-stranded positive-sense RNA viruses such as SARS-CoV-2, RNA helicases are essential for viral genome transcription and protein translation. Thus, inhibitors of viral helicases are attractive as therapeutic agents. At least one molecule inhibitor of SARS-CoV helicase without cell toxicity has been previously identified (Cho et al., 2015). However, despite significant efforts being made toward their development, helicase inhibitors are currently not available for clinical use (Briguglio et al., 2011). The SARS-CoV-2 exonuclease (Nsp14) cleaves nucleotides at 3′ end of RNA strand and is required for RNA replication (Romano et al., 2020). Uridine-specific endoribonuclease (Nsp15, EndoU) is an endoribonuclease that hydrolyzes single-stranded as well as double-stranded RNA at uridine residues. EndoU is highly conserved in all coronaviruses, which suggests its functional importance (Hackbart et al., 2020). Although its precise role in viral pathogenesis is not well established, it likely plays a role in evading host recognition (Deng and Baker, 2018). A recent study confirmed that EndoU contributes to delayed type I interferon response by cleaving 5′-polyuridines from negative-sense viral RNAs, which otherwise activate host immune sensors (Hackbart et al., 2020). There are currently no approved inhibitors for viral-specific 3′–5′ exonuclease or EndoU. In coronaviruses, RNA-cap methyltransferase (Nsp16) forms a complex with its cofactor Nsp10 (a 2-O-methyltransferase) for the addition of a cap to the 5′-end of viral RNA. This addition enables the virus to escape innate immune recognition in host cells as well as enhance viral RNA translation (Wang et al., 2015). Unfortunately, there are currently no effective inhibitors or approved drugs for these enzymes that may be used as targets for antiviral drug development.

Host Cell and Viral Targets for Antiviral Drug Development

Viral replication requires a number of cellular proteins and machinery. Inhibiting host cell protein function may effectively combat viral infection. These host targets include the host cell proteases TMPRSS2, furin, and cathepsin and ACE2 receptor discussed above. Additionally, the host cell autophagy pathway is used by some coronaviruses for viral replication and viral assembly. Since coronaviruses may hijack autophagy mechanisms for viral double membrane vesicle formation and replication, the inhibition of cellular autophagy may be a useful antiviral strategy (Abdoli et al., 2018; Yang and Shen, 2020). Although the drugs targeting host cell proteins are more likely to cause adverse effects, patients might tolerate a short 7–14-day treatment regimen. Other complicating factors for targeting host proteins is the redundancy of human cellular function pathways and variations in different cells or tissues, which may reduce correlations between in vitro and in vivo efficacy studies. This issue could be overcome by utilizing a drug combination therapy with different mechanisms of action such as that seen with the successful treatment of HIV; see the review by Maeda et al. (2019). Alternatively, a single drug with multiple activities against both viral targets and host viral replication machineries may be more effective in treating SARS-CoV-2 infection than drugs acting on one viral target. These drugs with polypharmacology against SARS-CoV-2 infection are discussed below.

Chloroquine (CQ) or hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) is a well known FDA-approved antimalarial drug that can inhibit viral infections via multiple mechanisms. The mechanism of inhibition likely involves the prevention of endocytosis or rapid elevation of the endosomal pH and abrogation of virus-endosome fusion (Devaux et al., 2020). CQ/HCQ also has anti-inflammatory properties, which has led to its clinical use in conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, and sarcoidosis (Savarino et al., 2003). After the advent of SARS in 2003, Savarino et al. (2003) postulated that the antiviral as well as anti-inflammatory properties of CQ/HCQ might be beneficial for SARS treatment. In addition, viruses may engage host autophagic processes to enhance replication (Yang and Shen, 2020). Since CQ is a known inhibitor of autophagic flux, it may be beneficial in inhibiting viral replication. CQ was shown to be highly effective in the control of SARS-CoV-2 infection in vitro (Wang et al., 2020a). It can also potentially interfere with the terminal glycosylation of ACE2 receptor expression, thereby preventing SARS-CoV-2 receptor binding and subsequent spread of infection (Barlow et al., 2020). Andreani et al. (2020) found that HCQ significantly suppresses virus replication, and a combination of HCQ and azithromycin exhibits synergistic effects. However, the FDA has warned that the use of CQ/HCQ, particularly when used in conjunction with azithromycin, can cause abnormal heart rhythms such as QT interval prolongation and ventricular tachycardia. As of June 15, 2020, FDA has revoked the emergency use authorization of these drugs for the treatment of COVID-19. Several clinical trials are underway to test the efficacy of CQ/HCQ in different settings, although a few have been withdrawn. In addition, a drug repurposing screen performed in different cell lines indicates that viral entry in lung epithelial Calu-3 cells is pH-independent (M. Dittmar et al., preprint, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.19.161042). Therefore, CQ may not be effective as a treatment against SARS-CoV-2.

Emetine, approved for amoebiasis, has broad antiviral activity against Zika virus, EBOV, Dengue virus, human cytomegalovirus, and HIV in vitro and in vivo. Emetine may elicit cardiotoxic and myotoxic effects with high doses; however, its potency as an antiviral is significantly lower than doses that cause toxicity (Yang et al., 2018). Emetine can act on multiple mechanisms such as viral RdRp inhibition, host cell lysosomal function, and blocking viral protein synthesis via inhibition of host cell 40S ribosomal protein S14 (Yang et al., 2018). A combination of 6.25 μM remdesivir and 0.195 μM emetine showed synergistic effects in vitro against SARS-CoV-2 infection, but some of the compounds currently undergoing clinical trials such as ribavirin and favipiravir did not show clear antiviral effects (Choy et al., 2020). This suggests that combination therapy may be a superior therapeutic option for the treatment of COVID-19 due to synergistic effects.

Niclosamide, an antiparasitic drug approved by FDA, has shown great potential for repurposing to treat a variety of viral infections including SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV by targeting both host and viral components (Xu et al., 2020a). Preliminary studies showed that niclosamide has potent antiviral activity against SARS-CoV-2 in vitro with an IC50 of 0.28 μM (Jeon et al., 2020). In addition, niclosasmide exhibits very low toxicities in vitro and in vivo (Chen et al., 2018), making it an attractive candidate.

Nitazoxanide is another antiparasitic prodrug approved by FDA with antiviral properties and is reportedly well tolerated in patients. Although the mechanisms of viral inhibition are not well understood, it is thought to target host-regulated pathways and not viral machinery (Rossignol, 2016). In keeping with this, it was shown that nitazoxanide significantly inhibits EBOV in vitro by enhancing host antiviral responses (Jasenosky et al., 2019). An in vitro study determined that nitazoxanide can inhibit SARS-CoV-2 at low-micromolar concentrations with an EC50 value of 2.12 μM (Wang et al., 2020a). Several trials are currently ongoing to determine its clinical efficacy as a treatment of patients with COVID-19 or as a postexposure prophylaxis therapy.

Prophylactic Treatment of SARS-CoV-2 Infection

SARS-CoV-2 infects humans mainly through inhalation of virally contaminated aerosol droplets from infected subjects. Thus, nasal sprays containing agents that can neutralize the virus or block viral entry into host cells are one approach to prevent SARS-CoV-2 infection. There are preliminary reports that an antihistamine nasal spray can inhibit SARS-CoV-2 infection in vitro (G. Ferrer and J. Westover, preprint, DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-25854/v1). In rhesus monkeys, a nasal spray formulation of interferon-α2b was successful in decreasing the severity of SARS-CoV viral infection (Gao et al., 2005). Meng and colleagues also reported that a nasal drop formula of recombinant human interferon-α1b prevented SARS-CoV-2 infection in an open label clinical trial (Z. Meng et al., preprint, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.11.20061473). Additionally, it might be possible to achieve high local drug concentrations for drugs with low systemic distribution and/or dose limiting toxicity when delivered systemically. Therefore, nasal administration of drugs merits further studies as a useful strategy in preventing or reducing SARS-CoV-2 infection. Phytochemicals from naturally occurring plants, particularly lectins and polyphenols, might also prove to be valuable candidates as prophylactic or therapeutic treatment against SARS-CoV-2 (recently reviewed in Mani et al. (2020)).

Other Treatments in Clinical Trials for COVID-19

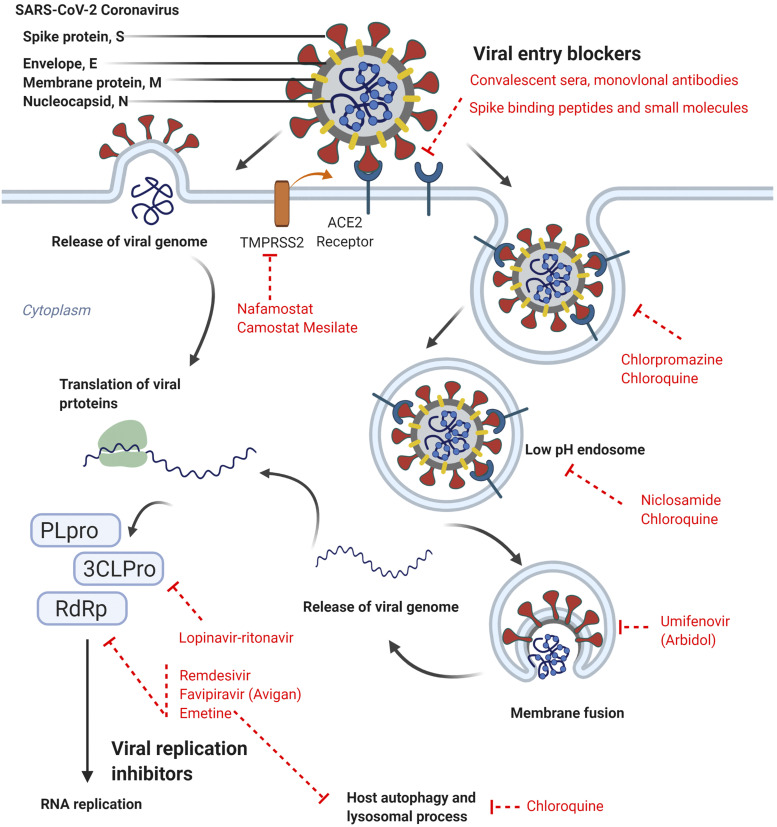

Several drugs that target viral life cycles directly as well as host biology are currently being investigated for COVID-19 and are summarized in Table 2 and depicted in Figure 1. As previously discussed, in patients with severe cases of COVID-19, excessive inflammatory responses and cytokine release likely contributes to the severity of disease stimulating lung and other systemic injuries. The early modulation of these responses may help reduce the risk of acute respiratory distress (Barlow et al., 2020). To this end, therapies such as inhibitory human monoclonal antibodies against cytokines such as interleukin-6 (IL-6) are also being considered to help diminish the severity of excessive physiologic response to SARS-CoV-2. The efficacy of glucocorticoids, such as methylprednisolone or dexamethasone, for the treatment of COVID-19 is yet to be determined. However, preliminary reports indicate that dexamethasone may be beneficial in critically ill patients with COVID-19 (P. Horby et al., preprint, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.22.20137273). In addition, ciclesonide, an inhaled corticosteroid might also prove an effective therapy as it has low cytotoxicity and can potently suppress SARS-CoV-2 growth in vitro (Jeon et al., 2020; S. Matsuyama et al., preprint, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.11.987016).

Fig. 1.

SARS-CoV-2 spike (S) protein binds the cell surface receptor ACE2 on host cells. Viral genome is delivered into the host cytosol by 1) directly fusing with the plasma membrane after being cleaved and activated by the serine protease TMPRSS2 or 2) using the host cell’s endocytic machinery in which the endocytosed virions are subjected to an activation step in the endosome. The viral genome also functions as the messenger RNA, which is translated into proteins, such as 3CLPro, papain-like cysteine protease (PLpro), and RdRp, by host cell machineries. The SARS-CoV-2 genome also encodes the structural proteins (S), envelope (E), membrane (M), and nucleocapsid (N). RdRP is essential for viral replication and therefore is an attractive target for anti–SARS-CoV-2 drugs. Drugs that are currently in clinical trials are shown here in red, along with their targets of viral life cycle or viral-host interactions. Figure created in BioRender.

Vaccines for SARS-CoV-2

Treating COVID-19 with drugs or convalescent plasma does not confer immunity; hence, there remains an unmet need for immediate and long-term disease prevention in the form of a vaccine. According to the World Health Organization, there are over 100 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine candidates under preclinical development, including 1) DNA-based vaccines, which contain DNA encoding immunogen in plasmids; 2) inactivated whole virus vaccines, which are heat or chemically inactivated; 3) live-attenuated vaccines, which contain viable but weakened virus; 4) RNA-based vaccines, where an RNA encoding the immunogen is directly introduced into the host; 5) replicating and nonreplicating viral vector-based vaccines, where viral vectors are used to introduce DNA-encoding immunogenic into the host; 6) protein subunits, which contain portions of a pathogen; and 7) virus-like particle-based vaccines, which contain nonpathogenic virus-like nanoparticles similar in composition to the virus of interest (https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/draft-landscape-of-covid-19-candidate-vaccines). Several vaccines from these categories are also under clinical investigation. The types of vaccines and their platforms used are summarized in Table 3. The advantages and disadvantages of using different platforms of vaccines vary and are reviewed elsewhere (Amanat and Krammer, 2020).

TABLE 3.

Potential vaccines in clinical trials for COVID-19 as of June 29, 2020

Sources: who.int/publications/m/item/draft-landscape-of-covid-19-candidate-vaccines; clinicaltrials.gov; clinicaltrialsregister.eu.

| Vaccine category | Vaccine type | Vaccine developer | Phase | Vaccine identifier |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNA based | DNA plasmid + electroporation | Inovio Pharmaceuticals | Phase 1 | NCT04336410 |

| DNA vaccine, GX-19 | Genexine Consortium | Phase 1 | NCT04445389 | |

| Inactivated virus | Inactivated | Beijing Institute of Biologic Products | Phase 1/2 | ChiCTR2000032459 |

| Inactivated | Wuhan Institute of Biologic Products | Phase 1/2 | ChiCTR2000031809 | |

| Inactivated | Sinovac Research & Development Co., Ltd | Phase 1/2 | NCT04352608 | |

| Phase 1/2 | NCT04383574 | |||

| Inactivated | Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences | Phase 1/2 | NCT04412538 | |

| Nonreplicating viral vector | Adenovirus type 5 | CanSino Biologic Inc; preliminary results (Zhu et al., 2020) | Phase 1 | NCT04313127 |

| Beijing Institute of Biotechnology | Phase 2 | ChiCTR2000031781 | ||

| ChAdOx1-S | University of Oxford/AstraZeneca | Phase 3 Phase 2/3 | ISRCTN89951424 | |

| Phase 2/3 | 2020-001228-32 | |||

| Phase 1/2 | NCT04400838 | |||

| Phase 1/2 | 2020-001072-15 NCT04324606 | |||

| Adenoviral | Gamaleya Research Institute | Phase 1 Phase 1/2 | NCT04436471 | |

| NCT04437875 | ||||

| Adeno based | Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences | Phase 2 | NCT04341389 NCT04412538 | |

| Protein subunit | Recombinant SARS-CoV-2 trimeric S protein subunit | Clover Biopharmaceuticals Inc./GSK/Dynavax | Phase 1 | NCT04405908 |

| Recombinant protein (RBD dimer) | Anhui Zhifei Longcom Biologic Pharmacy Co., Ltd/The Second Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University/Beijing Chao Yang Hospital | Phase 1 | NCT04445194 | |

| Full length recombinant SARS CoV-2 glycoproteinnanoparticle vaccine adjuvanted with Matrix M | Novavax | Phase 1/2 | NCT04368988 | |

| RNA | Messenger RNA in lipid nanoparticle | Moderna/NIH/NIAID; related preclinical study (Corbett et al., 2020) | Phase 1 Phase 2 | NCT04283461 NCT04405076 |

| Messenger RNA in lipid nanoparticle | BioNTech/Fosun Pharma/Pfizer | Phase 1/2 | 2020-001038-36 | |

| Phase 1 | NCT04368728 | |||

| mRNA | Curevac | Phase 1 | NCT04449276 | |

| mRNA | People’s Liberation Army (PLA) Academy of Military Sciences/Walvax Biotech | Phase 1 | ChiCTR2000034112 | |

| Self-amplifying RNA in lipid nanoparticle | Imperial College London | Phase 1 | ISRCTN17072692 |

GSK, GlaxoSmithKline; NIAID, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; NIH, National Institutes of Health.

There are high expectations for these vaccines to be available for distribution within a year. Undoubtedly, an effective vaccine is the ultimate tool for COVID-19 disease prevention, but there are some important aspects to consider. SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV emerged almost 20 and 10 years ago, respectively. To this date, there are no approved vaccinations to prevent either of these diseases, although there are several candidates in the unlicensed preclinical stage. Effective vaccines are still not available for many infectious diseases such as malaria, HIV, EBOV, and Zika virus. Vaccine development typically takes 10–15 years and is associated with high costs (Zheng et al., 2018). In addition, rapid mutations arising in viral RNA could potentially render these vaccines ineffective. RNA viruses are known to mutate with high frequency, but thus far there do not seem to be many differences in the S protein amino acid residue sequences in emergent SARS-CoV-2 variants from different countries (Robson, 2020). Antibodies induced by vaccination could also potentially increase the risk and severity of disease in subsequent host-pathogen encounters (Kulkarni, 2020). The production of these antibodies may sometimes prove beneficial to the virus instead of the host by facilitating viral entry and replication in the target cell in a phenomenon known as antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE) of infection (Kulkarni, 2020). ADE has been noted in cases of dengue virus, HIV, respiratory syncytial virus, and influenza virus but has not been confirmed for SARS or EBOV (Kulkarni, 2020). However, preliminary results in animal models of SARS-CoV-2 infection are promising. In both rodents (K. S. Corbett et al., preprint, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.11.145920) and nonhuman primates (Gao et al., 2020), vaccinations against SARS-CoV-2 have shown protection without any observable ADE. In addition, positive outcomes have been noted in participants of small study in terms of tolerability and immunogenicity (Zhu et al., 2020).

Perspectives and Conclusion

Safe and effective viral therapeutics or vaccine development necessitates that data initially be obtained from preclinical in vitro or animal models. However, preclinically developed drug candidates often fail in human clinical trials (Seyhan, 2019). For example, remdesivir efficiently suppressed EBOV replication in vitro with nanomolar activity and also protected 100% of infected animals from mortality (Warren et al., 2016). However, these results were not recapitulated in humans for the treatment of EBOV infections, and the remdesivir treatment group was terminated due to low efficacy and increased toxicities (Mulangu et al., 2019). In general, viral infections are highly dependent on host cells. Therefore, successful clinical translation of SARS-CoV-2 drugs would require careful considerations of the testing platform. These might include suitable cell models for in vitro viral infection assays as well as human induced pluripotent stem cell–derived airway and gut organoids.

SARS-CoV infection was curtailed by rigorous isolation, but MERS-CoV infection is still a concern, albeit at lower infectious rate than SARS-CoV-2. SARS-CoV-2 infections present a clinical challenge as they are highly transmissible in part due to asymptomatic transmission. Therefore, the approach taken with SARS-CoV would certainly help curtail the spread of SARS-CoV-2, but with the current spread of disease, such large-scale isolation and quarantine efforts have proven difficult. Therefore, better therapeutic options are essential. Multitarget treatment approaches of drug combination therapy have been successful with HIV treatment and will likely be a viable therapeutic strategy for the treatment of COVID-19. Combination drug therapy has been extensively used for the treatment of HIV, cancer, and severe bacterial and fungal infections. Recently, patients with COVID-19 treated with the triple antiviral drug cocktail lopinavir-ritonavir-ribavirin with interferon beta-1b compared with lopinavir-ritonavir alone showed significant improvements in clinical outcomes (Hung et al., 2020). In addition, the combination drugs elicited no further side effects compared with the two-drug controls. Combination drug therapy may increase toxicity compared with single drug treatment. A meta-analysis of published trials evaluated the efficacy and toxicity of two-drug full dose combination therapy versus a single full dose drug for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (Felson et al., 1994). The study concluded that combination therapy led to a 9% patient withdrawal rate due to significant increases in adverse effects. Therefore, with combination therapy approaches, drugs with dose limiting toxicity as monotherapies can be used with lower individual drug doses, thereby reducing toxicity and synergistically enhancing therapeutic efficacy (Sun et al., 2016; Hoenen et al., 2019). As an example, several FDA-approved drugs found in a drug repurposing screen showed activity against EBOV but were not clinically useful, as their plasma concentrations were not high enough to inhibit infection in humans (Kouznetsova et al., 2014). However, drug combination therapy using three of these drugs at low concentrations was able to effectively block EBOV infection in vitro (Sun et al., 2017). Thus, synergistic drug combinations can be particularly useful for drug repurposing (Zheng et al., 2018). For COVID-19, drug combination therapies with multiple agents that have different mechanisms of action, including inhibition of viral entry and replication, as well as inhibition of host immune responses, would be a practical and useful approach for disease intervention.

Abbreviations

- ACE

angiotensin converting enzyme

- ADE

antibody-dependent enhancement

- ARDS

acute respiratory distress syndrome

- BSL

biosafety level

- 3CLpro

3C-like serine protease

- COVID-19

coronavirus disease 2019

- CQ

chloroquine

- EBOV

Ebola virus

- EndoU

uridine-specific endoribonuclease

- FDA

US Food and Drug Administration

- HIV

human immunodeficiency virus

- HCQ

hydroxychloroquine

- IL-6

interleukin-6

- MERS-CoV

Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus

- NSP

nonstructural protein

- RBD

receptor-binding domain

- RdRp

RNA-dependent RNA polymerase

- SARS

severe acute respiratory syndrome

- SARS-CoV

severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus

- TMPRSS2

transmembrane protease serine type 2

Authorship Contributions

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Shyr, Gorshkov, Chen, Zheng.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Programs of the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of National Institutes of Health (Grants ZIA-TR000018-01 and ZIA TR000422).

References

- Abdoli A, Alirezaei M, Mehrbod P, Forouzanfar F. (2018) Autophagy: the multi-purpose bridge in viral infections and host cells. Rev Med Virol 28:e1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amanat F, Krammer F. (2020) SARS-CoV-2 vaccines: status report. Immunity 52:583–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreani J, Le Bideau M, Duflot I, Jardot P, Rolland C, Boxberger M, Wurtz N, Rolain JM, Colson P, La Scola B, et al. (2020) In vitro testing of combined hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin on SARS-CoV-2 shows synergistic effect. Microb Pathog 145:104228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baden LR, Rubin EJ. (2020) Covid-19 - the search for effective therapy. N Engl J Med 382:1851–1852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow A, Landolf KM, Barlow B, Yeung SYA, Heavner JJ, Claassen CW, Heavner MS. (2020) Review of emerging pharmacotherapy for the treatment of coronavirus disease 2019. Pharmacotherapy 40:416–437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beigel JH, Tomashek KM, Dodd LE, Mehta AK, Zingman BS, Kalil AC, Hohmann E, Chu HY, Luetkemeyer A, Kline S, et al. ACTT-1 Study Group Members (2020) Remdesivir for the treatment of covid-19 - preliminary report. N Engl J Med DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa2007764 [published ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briguglio I, Piras S, Corona P, Carta A. (2011) Inhibition of RNA helicases of ssRNA(+) virus belonging to Flaviviridae, Coronaviridae and Picornaviridae families. Int J Med Chem 2011:213135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caly L, Druce JD, Catton MG, Jans DA, Wagstaff KM. (2020) The FDA-approved drug ivermectin inhibits the replication of SARS-CoV-2 in vitro. Antiviral Res 178:104787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casadevall A, Pirofski LA. (2020) The convalescent sera option for containing COVID-19. J Clin Invest 130:1545–1548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Mook RA, Jr., Premont RT, Wang J. (2018) Niclosamide: beyond an antihelminthic drug. Cell Signal 41:89–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho JB, Lee JM, Ahn HC, Jeong YJ. (2015) Identification of a novel small molecule inhibitor against SARS coronavirus helicase. J Microbiol Biotechnol 25:2007–2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choy KT, Wong AY, Kaewpreedee P, Sia SF, Chen D, Hui KPY, Chu DKW, Chan MCW, Cheung PP, Huang X, et al. (2020) Remdesivir, lopinavir, emetine, and homoharringtonine inhibit SARS-CoV-2 replication in vitro. Antiviral Res 178:104786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corti D, Cameroni E, Guarino B, Kallewaard NL, Zhu Q, Lanzavecchia A. (2017) Tackling influenza with broadly neutralizing antibodies. Curr Opin Virol 24:60–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cubitt B, Ortiz-Riano E, Cheng BY, Kim YJ, Yeh CD, Chen CZ, Southall NOE, Zheng W, Martinez-Sobrido L, de la Torre JC. (2020) A cell-based, infectious-free, platform to identify inhibitors of lassa virus ribonucleoprotein (vRNP) activity. Antiviral Res 173:104667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day CW, Baric R, Cai SX, Frieman M, Kumaki Y, Morrey JD, Smee DF, Barnard DL. (2009) A new mouse-adapted strain of SARS-CoV as a lethal model for evaluating antiviral agents in vitro and in vivo. Virology 395:210–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng X, Baker SC. (2018) An “Old” protein with a new story: coronavirus endoribonuclease is important for evading host antiviral defenses. Virology 517:157–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devaux CA, Rolain JM, Colson P, Raoult D. (2020) New insights on the antiviral effects of chloroquine against coronavirus: what to expect for COVID-19? Int J Antimicrob Agents 55:105938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wilde AH, Jochmans D, Posthuma CC, Zevenhoven-Dobbe JC, van Nieuwkoop S, Bestebroer TM, van den Hoogen BG, Neyts J, Snijder EJ. (2014) Screening of an FDA-approved compound library identifies four small-molecule inhibitors of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus replication in cell culture. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:4875–4884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit E, Feldmann F, Cronin J, Jordan R, Okumura A, Thomas T, Scott D, Cihlar T, Feldmann H. (2020) Prophylactic and therapeutic remdesivir (GS-5734) treatment in the rhesus macaque model of MERS-CoV infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 117:6771–6776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drosten C, Günther S, Preiser W, van der Werf S, Brodt HR, Becker S, Rabenau H, Panning M, Kolesnikova L, Fouchier RA, et al. (2003) Identification of a novel coronavirus in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N Engl J Med 348:1967–1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan K, Liu B, Li C, Zhang H, Yu T, Qu J, Zhou M, Chen L, Meng S, Hu Y, et al. (2020) Effectiveness of convalescent plasma therapy in severe COVID-19 patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 117:9490–9496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyall J, Coleman CM, Hart BJ, Venkataraman T, Holbrook MR, Kindrachuk J, Johnson RF, Olinger GG, Jr., Jahrling PB, Laidlaw M, et al. (2014) Repurposing of clinically developed drugs for treatment of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:4885–4893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felson DT, Anderson JJ, Meenan RF. (1994) The efficacy and toxicity of combination therapy in rheumatoid arthritis. A meta-analysis. Arthritis Rheum 37:1487–1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuta Y, Komeno T, Nakamura T. (2017) Favipiravir (T-705), a broad spectrum inhibitor of viral RNA polymerase. Proc Jpn Acad, Ser B, Phys Biol Sci 93:449–463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao H, Zhang LL, Wei Q, Duan ZJ, Tu XM, Yu ZA, Deng W, Zhang LP, Bao LL, Zhang B, et al. (2005) [Preventive and therapeutic effects of recombinant IFN-alpha2b nasal spray on SARS-CoV infection in Macaca mulata]. Zhonghua Shi Yan He Lin Chuang Bing Du Xue Za Zhi 19:207–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Q, Bao L, Mao H, Wang L, Xu K, Yang M, Li Y, Zhu L, Wang N, Lv Z, et al. (2020) Development of an inactivated vaccine candidate for SARS-CoV-2. Science 369:77–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gierer S, Bertram S, Kaup F, Wrensch F, Heurich A, Krämer-Kühl A, Welsch K, Winkler M, Meyer B, Drosten C, et al. (2013) The spike protein of the emerging betacoronavirus EMC uses a novel coronavirus receptor for entry, can be activated by TMPRSS2, and is targeted by neutralizing antibodies. J Virol 87:5502–5511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glowacka I, Bertram S, Müller MA, Allen P, Soilleux E, Pfefferle S, Steffen I, Tsegaye TS, He Y, Gnirss K, et al. (2011) Evidence that TMPRSS2 activates the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike protein for membrane fusion and reduces viral control by the humoral immune response. J Virol 85:4122–4134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grein J, Ohmagari N, Shin D, Diaz G, Asperges E, Castagna A, Feldt T, Green G, Green ML, Lescure FX, et al. (2020) Compassionate use of remdesivir for patients with severe covid-19. N Engl J Med 382:2327–2336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hackbart M, Deng X, Baker SC. (2020) Coronavirus endoribonuclease targets viral polyuridine sequences to evade activating host sensors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 117:8094–8103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoenen T, Groseth A, Feldmann H. (2019) Therapeutic strategies to target the Ebola virus life cycle. Nat Rev Microbiol 17:593–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann M, Kleine-Weber H, Schroeder S, Krüger N, Herrler T, Erichsen S, Schiergens TS, Herrler G, Wu NH, Nitsche A, et al. (2020a) SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell 181:271–280.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann M, Schroeder S, Kleine-Weber H, Müller MA, Drosten C, Pöhlmann S. (2020b) Nafamostat mesylate blocks activation of SARS-CoV-2: new treatment option for COVID-19. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 64:e00754-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung IF, Lung KC, Tso EY, Liu R, Chung TW, Chu MY, Ng YY, Lo J, Chan J, Tam AR, et al. (2020) Triple combination of interferon beta-1b, lopinavir-ritonavir, and ribavirin in the treatment of patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19: an open-label, randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet 395:1695–1704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata-Yoshikawa N, Okamura T, Shimizu Y, Hasegawa H, Takeda M, Nagata N. (2019) TMPRSS2 contributes to virus spread and immunopathology in the airways of murine models after coronavirus infection. J Virol 93:e01815-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasenosky LD, Cadena C, Mire CE, Borisevich V, Haridas V, Ranjbar S, Nambu A, Bavari S, Soloveva V, Sadukhan S, et al. (2019) The FDA-approved oral drug nitazoxanide amplifies host antiviral responses and inhibits Ebola virus. iScience 19:1279–1290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon S, Ko M, Lee J, Choi I, Byun SY, Park S, Shum D, Kim S. (2020) Identification of antiviral drug candidates against SARS-CoV-2 from FDA-approved drugs. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 64:e00819-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouznetsova J, Sun W, Martínez-Romero C, Tawa G, Shinn P, Chen CZ, Schimmer A, Sanderson P, McKew JC, Zheng W, et al. (2014) Identification of 53 compounds that block Ebola virus-like particle entry via a repurposing screen of approved drugs. Emerg Microbes Infect 3:e84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuba K, Imai Y, Rao S, Gao H, Guo F, Guan B, Huan Y, Yang P, Zhang Y, Deng W, et al. (2005) A crucial role of angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) in SARS coronavirus-induced lung injury. Nat Med 11:875–879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni R. (2020) Antibody-dependent enhancement of viral infections, in Dynamics of Immune Activation in Viral Diseases (Bramhachari PV. ed) pp 9–41, Springer, Singapore. [Google Scholar]

- Kumaki Y, Wandersee MK, Smith AJ, Zhou Y, Simmons G, Nelson NM, Bailey KW, Vest ZG, Li JK, Chan PK, et al. (2011) Inhibition of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus replication in a lethal SARS-CoV BALB/c mouse model by stinging nettle lectin, Urtica dioica agglutinin. Antiviral Res 90:22–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letko M, Marzi A, Munster V. (2020) Functional assessment of cell entry and receptor usage for SARS-CoV-2 and other lineage B betacoronaviruses. Nat Microbiol 5:562–569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Geng M, Peng Y, Meng L, Lu S. (2020) Molecular immune pathogenesis and diagnosis of COVID-19. J Pharm Anal 10:102–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu R, Zhao X, Li J, Niu P, Yang B, Wu H, Wang W, Song H, Huang B, Zhu N, et al. (2020) Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet 395:565–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda K, Das D, Kobayakawa T, Tamamura H, Takeuchi H. (2019) Discovery and development of anti-HIV therapeutic agents: progress towards improved HIV medication. Curr Top Med Chem 19:1621–1649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mani JS, Johnson JB, Steel JC, Broszczak DA, Neilsen PM, Walsh KB, Naiker M. (2020) Natural product-derived phytochemicals as potential agents against coronaviruses: a review. Virus Res 284:197989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathewson AC, Bishop A, Yao Y, Kemp F, Ren J, Chen H, Xu X, Berkhout B, van der Hoek L, Jones IM. (2008) Interaction of severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus and NL63 coronavirus spike proteins with angiotensin converting enzyme-2. J Gen Virol 89:2741–2745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuyama S, Nagata N, Shirato K, Kawase M, Takeda M, Taguchi F. (2010) Efficient activation of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike protein by the transmembrane protease TMPRSS2. J Virol 84:12658–12664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuyama S, Nao N, Shirato K, Kawase M, Saito S, Takayama I, Nagata N, Sekizuka T, Katoh H, Kato F, et al. (2020) Enhanced isolation of SARS-CoV-2 by TMPRSS2-expressing cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 117:7001–7003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millet JK, Séron K, Labitt RN, Danneels A, Palmer KE, Whittaker GR, Dubuisson J, Belouzard S. (2016) Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection is inhibited by griffithsin. Antiviral Res 133:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell CA, Ramessar K, O’Keefe BR. (2017) Antiviral lectins: selective inhibitors of viral entry. Antiviral Res 142:37–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteil V, Kwon H, Prado P, Hagelkruys A, Wimmer RA, Stahl M, Leopoldi A, Garreta E, Hurtado Del Pozo C, Prosper F, et al. (2020) Inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 infections in engineered human tissues using clinical-grade soluble human ACE2. Cell 181:905–913.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori T, O’Keefe BR, Sowder RC, II, Bringans S, Gardella R, Berg S, Cochran P, Turpin JA, Buckheit RW, Jr., McMahon JB, et al. (2005) Isolation and characterization of griffithsin, a novel HIV-inactivating protein, from the red alga Griffithsia sp. J Biol Chem 280:9345–9353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morse JS, Lalonde T, Xu S, Liu WR. (2020) Learning from the past: possible urgent prevention and treatment options for severe acute respiratory infections caused by 2019-nCoV. ChemBioChem 21:730–738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulangu S, Dodd LE, Davey RT, Jr., Tshiani Mbaya O, Proschan M, Mukadi D, Lusakibanza Manzo M, Nzolo D, Tshomba Oloma A, Ibanda A, et al. PALM Writing Group. PALM Consortium Study Team (2019) A randomized, controlled trial of Ebola virus disease therapeutics. N Engl J Med 381:2293–2303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murin CD, Wilson IA, Ward AB. (2019) Antibody responses to viral infections: a structural perspective across three different enveloped viruses. Nat Microbiol 4:734–747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Needle D, Lountos GT, Waugh DS. (2015) Structures of the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus 3C-like protease reveal insights into substrate specificity. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 71:1102–1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Keefe BR, Giomarelli B, Barnard DL, Shenoy SR, Chan PKS, McMahon JB, Palmer KE, Barnett BW, Meyerholz DK, Wohlford-Lenane CL, et al. (2010) Broad-spectrum in vitro activity and in vivo efficacy of the antiviral protein griffithsin against emerging viruses of the family Coronaviridae. J Virol 84:2511–2521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ou X, Liu Y, Lei X, Li P, Mi D, Ren L, Guo L, Guo R, Chen T, Hu J, et al. (2020) Characterization of spike glycoprotein of SARS-CoV-2 on virus entry and its immune cross-reactivity with SARS-CoV. Nat Commun 11:1620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puelles VG, Lutgehetmann M, Lindenmeyer MT, Sperhake JP, Wong MN, Allweiss L, Chilla S, Heinemann A, Wanner N, Liu S, et al. (2020) Multiorgan and renal tropism of SARS-CoV-2. N Engl J Med DOI: 10.1056/NEJMc2011400 [published ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qing E, Gallagher T. (2020) SARS coronavirus redux. Trends Immunol 41:271–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robson B. (2020) Computers and viral diseases. Preliminary bioinformatics studies on the design of a synthetic vaccine and a preventative peptidomimetic antagonist against the SARS-CoV-2 (2019-nCoV, COVID-19) coronavirus. Comput Biol Med 119:103670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romano M, Ruggiero A, Squeglia F, Maga G, Berisio R. (2020) A structural view of SARS-CoV-2 RNA replication machinery: RNA synthesis, proofreading and final capping. Cells 9:1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossignol JF. (2016) Nitazoxanide, a new drug candidate for the treatment of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J Infect Public Health 9:227–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saphire EO, Schendel SL, Gunn BM, Milligan JC, Alter G. (2018) Antibody-mediated protection against Ebola virus. Nat Immunol 19:1169–1178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savarino A, Boelaert JR, Cassone A, Majori G, Cauda R. (2003) Effects of chloroquine on viral infections: an old drug against today’s diseases? Lancet Infect Dis 3:722–727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaffner TJ, Skoner DP. (2009) Ciclesonide: a safe and effective inhaled corticosteroid for the treatment of asthma. J Asthma Allergy 2:25–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seyhan AA. (2019) Lost in translation: the valley of death across preclinical and clinical divide – identification of problems and overcoming obstacles. Transl Med Commun 4:18. [Google Scholar]

- Shanmugaraj B, Siriwattananon K, Wangkanont K, Phoolcharoen W. (2020) Perspectives on monoclonal antibody therapy as potential therapeutic intervention for Coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19). Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol 38:10–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheahan TP, Sims AC, Graham RL, Menachery VD, Gralinski LE, Case JB, Leist SR, Pyrc K, Feng JY, Trantcheva I, et al. (2017) Broad-spectrum antiviral GS-5734 inhibits both epidemic and zoonotic coronaviruses. Sci Transl Med 9:eaal3653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen C, Wang Z, Zhao F, Yang Y, Li J, Yuan J, Wang F, Li D, Yang M, Xing L, et al. (2020) Treatment of 5 critically ill patients with COVID-19 with convalescent plasma. JAMA 323:1582–1589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shulla A, Heald-Sargent T, Subramanya G, Zhao J, Perlman S, Gallagher T. (2011) A transmembrane serine protease is linked to the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus receptor and activates virus entry. J Virol 85:873–882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigrist CJ, Bridge A, Le Mercier P. (2020) A potential role for integrins in host cell entry by SARS-CoV-2. Antiviral Res 177:104759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockman LJ, Bellamy R, Garner P. (2006) SARS: systematic review of treatment effects. PLoS Med 3:e343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]