Abstract

Objectives

To determine whether patients with early rheumatoid arthritis (ERA) have cardiovascular disease (CVD) that is modifiable with disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD) therapy, comparing first-line etanercept (ETN) + methotrexate (MTX) with MTX strategy.

Methods

Patients from a phase IV ERA trial randomised to ETN+MTX or MTX strategy±month 6 escalation to ETN+MTX, and with no CVD and maximum one traditional risk factor underwent cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR) at baseline, years 1 and 2. Thirty matched controls underwent CMR. Primary outcome measure was aortic distensibility (AD) between controls and ERA, and baseline to year 1 AD change in ERA. Secondary analyses between and within ERA groups performed. Additional outcome measures included left ventricular (LV) mass and myocardial extracellular volume (ECV).

Results

Eighty-one patients recruited. In ERA versus controls, respectively, baseline (geometric mean, 95% CI) AD was significantly lower (3.0×10−3 mm Hg−1 (2.7–3.3) vs 4.4×10−3 mm Hg−1 (3.7–5.2), p<0.001); LV mass significantly lower (78.2 g (74.0–82.7), n=81 vs 92.9 g (84.8–101.7), n=30, p<0.01); and ECV increased (27.1% (26.4–27.9), n=78 vs 24.9% (23.8–26.1), n=30, p<0.01). Across all patients, AD improved significantly from baseline to year 1 (3.0×10−3 mm Hg−1 (2.7–3.4) to 3.6×10–3 mm Hg−1 (3.1–4.1), respectively, p<0.01), maintained at year 2. The improvement in AD did not differ between the two treatment arms and disease activity state (Disease Activity Score with 28 joint count)-erythrocyte sedimentation rate-defined responders versus non-responders.

Conclusion

We report the first evidence of vascular and myocardial abnormalities in an ERA randomised controlled trial cohort and show improvement with DMARD therapy. The type of DMARD (first-line tumour necrosis factor-inhibitors or MTX) and clinical response to therapy did not affect CVD markers.

Trial registration number

ISRCTN: ISRCTN89222125; ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT01295151.

Keywords: cardiovascular diseases, arthritis, rheumatoid, tumor necrosis factors, atherosclerosis, magnetic resonance imaging

Key messages.

What is already known about this subject?

Epidemiological studies have shown reduction in cardiovascular (CV) events coinciding with contemporary management of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and clinical imaging studies have illustrated abnormal CV measures, mainly in established RA, with varying association to poor prognosis factors of RA.

What does this study add?

This first study of an early RA, treatment-naïve randomised controlled trial cohort with no known CV history and maximum of one traditional risk factor (excluding diabetes) reveals abnormal vascular stiffness (which has been shown to predict major CV events independently of traditional clinical risk scoring models in patients without known cardiovascular disease (CVD)) and evidence of diffuse myocardial fibrosis and reduced left ventricular mass.

First-line etanercept with methotrexate, or initial methotrexate-treat-to-target strategy improved vascular stiffness. However, RA treatment response and cumulative disease activity do not appear to add to this improvement in vascular stiffness.

Key messages.

How might this impact on clinical practice or future developments?

These data imply benefits of therapy beyond suppression of systemic inflammation, likely suggesting cardiometabolic changes and targeted effects on key immune mediators of CVD.

This study builds on the concept of targeted therapeutics in atherosclerosis, whereby immune modulating treatment may be personalised in stratified patients with RA to not only improve joint specific outcome, but also CVD.

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is associated with up to threefold increased mortality compared with the general population. This is largely due to increased frequency of premature cardiovascular disease (CVD), notably atherosclerosis and heart failure.1 2 This excess risk is as high as that of patients with major CVD risk factors such as type 2 diabetes mellitus3 and is considered independent of and incremental to traditional cardiovascular (CV) risk factors.4

In addition to traditional risk factors, notably, hypertension, smoking and high cholesterol,5 the heightened CV risk in RA is thought to be mediated by inflammation.4 In the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis, identification of key immune mediators and pathways6 has informed recent proof-of-concept randomised controlled trials (RCT).7 Such insights support the concept of shared immune mechanisms and raise the possibility that RA immune-modulating therapies may also influence CVD pathogenesis.

The modest overall CVD event rate in RA8 has necessitated studies employing imaging-based surrogate markers of CVD. These have illustrated improvement in CVD with RA disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD) therapy, including biological DMARDs (bDMARDs) such as tumour necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFi) bDMARD9 but translation to clinical practice has been limited. Of the various modalities, cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR) offers the most sensitive tool for the assessment of CVD, with the advantage of providing multiparametric anatomical, functional, perfusion and tissue characteristic assessment.10

This study was originally coined the Coronary Artery Disease in Early RA study but designed as a wider CArdiovascular Disease Evaluation in RA,11 a first bolt-on study to a parent RCT in an early RA (ERA) inception cohort.12 The objectives are to evaluate whether patients with treatment-naive ERA demonstrate myocardial and vascular changes on CMR compared with controls; whether abnormalities are modifiable over a 1-year period with DMARD strategies and maintained over 2 years; and whether the type of intervention (standard of care methotrexate (MTX)-treat to target (MTX-TT)13) or TNFi and MTX) affects extent of change in CV abnormality.

Methods

All participants provided written informed consent. Detailed trial protocols for both the parent RCT (called ‘VEDERA’)12 and this study11 have been published.

Participants

Patients were recruited between February 2012 and November 2015. Consecutive patients diagnosed with new-onset RA according to American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism 2010 criteria14 were invited to enrol into the VEDERA RCT and this substudy. The principal eligibility criteria included: no previous DMARD exposure, symptom duration ≤12 months, at least moderate disease activity (Disease Activity Score with 28 joint count (DAS28-ESR) ≥ 3.2) and one poor prognostic factor (positive rheumatoid factor±anticitrullinated protein antibody±abnormal ultrasound power Doppler in any joint) and a maximum of one traditional CVD risk factor. Diabetes mellitus was excluded in all patients.

As part of the parent RCT,12 all patients were randomised on a 1:1 basis either to: first-line TNFi, etanercept (ETN) + MTX (15 mg weekly, optimised to 25 mg weekly by week 8); or first-line MTX-TT (MTX monotherapy 15 mg weekly increased to 25 mg weekly at 2 weeks with further protocolised csDMARD escalation if indicated). At week 24, MTX-TT patients escalated to ETN + MTX if they failed to achieve DAS28-ESR remission (DAS28-ESR≥2.6). At year 1, all patients on ETN stopped the TNFi and standard of care was maintained, with further 1-year observation period. Full details are included in the online supplementary file.

annrheumdis-2020-217653supp001.pdf (298.3KB, pdf)

Controls

Thirty healthy volunteers (controls) with no history or risk factors for CVD were matched to the first 30 study patients by age and sex (see online supplementary file for details) and underwent a single CMR scan.

CMR imaging

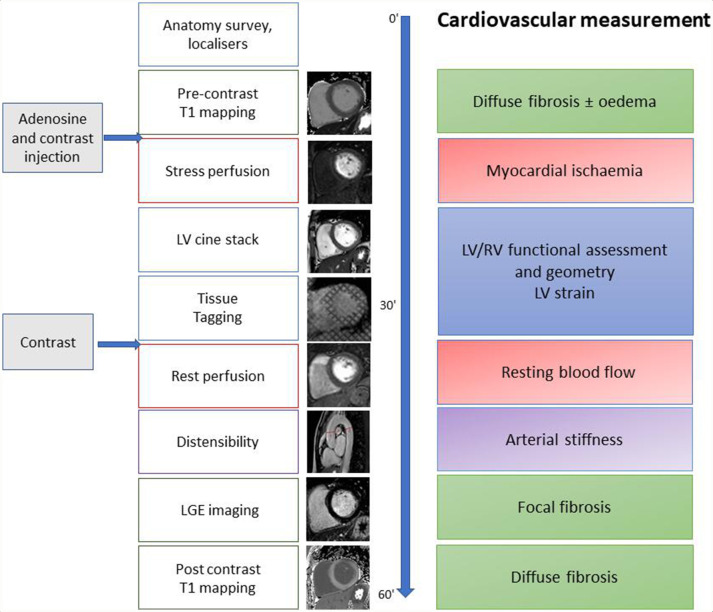

CMR scans were conducted at baseline (prior to the commencement of randomised treatment), 1 and 2 years after enrolment. All scans were performed on the same 3.0T system (Philips Achieva, Best, The Netherlands). The CMR protocol is illustrated in figure 1, summarised in the online supplementary file and has previously been described.11 15 CMR analysis was performed using CVI V.42 software (Circle Cardiovascular Imaging Calgary, Canada) by two assessors (GF, BE) both with 2 years of experience and supervised by a senior CMR expert (SP). The following measurements were made: aortic distensibility (AD), left ventricular (LV) volume and mass, native T1 and myocardial extracellular volume (ECV). Late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) and stress and rest perfusion images were visually assessed by the presence and distribution of hyperenhancement and inducible regional perfusion defects, respectively.

Figure 1.

Cardiac MRI protocol. LGE, late gadolinium enhancement; LV, left ventricular; RV, right ventricular.

Blinding

The CV radiographer and investigators who performed and analysed the scans, respectively, were blinded to treatment arm, specific treatment allocation and the RA clinical trial data over the entire study duration. Similarly, as previously reported for the parent RCT,12 RA clinical assessments were undertaken by blinded joint count assessors to inform the RA trial outcomes.

Statistical analysis

Outcome measures

The primary outcome measure was AD, as a measure of aortic stiffness. AD has been shown to predict CV outcomes in several conditions, including hypertension16 and asymptomatic patients with diabetes,17 and is highly reproducible.18 Secondary outcome measures included LV ejection fraction, LV mass, LV longitudinal strain (LVLS), peak left ventricular twist (PLVTw) and perfusion. Myocardial T1 and ECV were exploratory outcome measures.

Sample size calculation

Based on a previous study showing improved AD in patients with RA in response to interleukin (IL)-1 directed therapy,19 we proposed 2.46 as an effect size (representing 75% of the difference between treated and non-treated patients with RA previously reported19). Assuming an SD of 2.5, 5% significance level in a two-tailed independent samples t-test at 90% power, 25 patients would be required per group, ETN-MTX and MTX-TT (adjusting for 10% drop-out).

Analysis methods

For comparisons between study patient and control groups, two different analyses were conducted on the primary, secondary and exploratory outcomes. Directly matched patients and controls were compared using paired Student’s t-tests. To maximise the data available and reflect the resulting approximate matching, linear regression analyses are also presented for all outcomes at baseline including the 30 controls and all patients with ERA. Each analysis is presented unadjusted (with a single independent variable case/control) and adjusted (with independent variables case/control, age, sex, systolic blood pressure and pack years smoked).

For analysis of outcomes at 1-year and 2-year follow-up, analysis of covariance was adopted. The outcome at follow-up is linearly regressed on a grouping variable (defined below), first as an unadjusted analysis (exploring differences by subgroup in the outcome at 1 or 2 years), second adjusted for baseline value of the outcome and third, additionally adjusted for baseline value, age, sex, systolic blood pressure and, where appropriate, baseline DAS28-ESR.

The primary outcome, AD, was analysed using an intention-to-treat approach with multiple imputation (see online supplementary file) to address missing data. Treatment response was defined as achievement of DAS28-ESR remission (<2.6; the primary endpoint of the VEDERA RCT). Patients with missing DAS28 at week 48 due to reasons other than withdrawal for lack of efficacy (LOE) were first assumed to be responders in the analysis. Data were then reimputed and reanalysed assuming they were non-responders (no difference was identified).

Interval change in AD from baseline to year 1 analysis was assessed in a stepwise fashion as follows: change in AD from baseline to year 1 was evaluated in the whole RA group. AD at 1 year was compared between the following groups to understand the effect of RA DAS28 control and/or any independent drug effect: ETN-MTX (all patients) versus MTX-TT (all patients); combined ETN-MTX and MTX-TT (responders) versus combined ETN-MTX and MTX-TT (non-responders) adjusting for baseline DAS28ESR; ETN-MTX (responders) and ETN-MTX (non-responders) adjusting for baseline DAS28ESR; ETN-MTX (responders) and MTX-TT responders (no ETN exposure) adjusting for baseline DAS28ESR. Statistical analysis was performed using and R V.2.14.1 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Patient recruitment and numbers

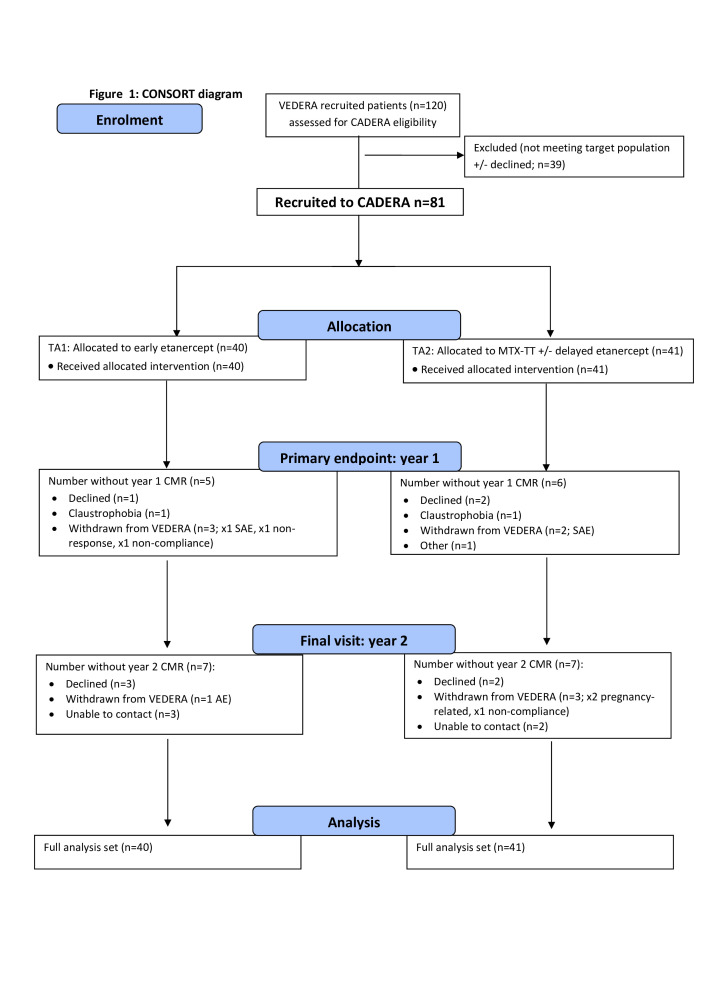

Eighty-two patients were enrolled and underwent baseline CMR. In one patient, no AD could be acquired (but they had all other assessments). Of the n=81 with complete baseline CMR, 71 underwent a 1-year scan and 57 a 2-year scan (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials diagram. Etanercept-methotrexate (ETN-MTX) = treatment arm 1; MTX-treat to target (TT) = treatment arm 2. TA1 year 1: n=20 responders; n=17 non-responders; 3 unknown. TA2 year 1: n=15 responders; n=21 non-responders; 5 unknown. AE, adverse event; CADREA, Coronary Artery Disease in Early RA; CMR, cardiovascular magnetic resonance; SAE, serious adverse event.

Withdrawals

Eleven patients did not have follow-up CMR at 1 year. One was withdrawn due to treatment non-compliance, one due to non-response and three due to treatment-related serious adverse events (AE). Three patients declined repeat CMR, two had claustrophobia and one patient moved away. At year 2, a further 14 patients were withdrawn, 1 due to treatment non-compliance, 1 due to a treatment-related AE and 2 pregnancy related. Five patients declined repeat CMR and five could not be contacted.

Baseline demographic data

Demographic data for the controls, ERA cohort and the two ERA treatment groups are presented in table 1 (and matched control and ERA in online supplementary table S1). The baseline characteristics were balanced across the two treatment groups with the exception of median pack years of smoking. Patients and controls were matched for age and sex. Online supplementary table S2 details the key demographic data relevant for the primary outcome, split by those with complete data for all outcomes and those that had at least one missing outcome. No notable differences were observed.

Table 1.

Summary of baseline demographic, disease activity and comorbidity data for controls and patients

| Variable | Controls n=30 | All patients with ERA n=81 | ETN-MTX n=40 | MTX-TT n=41 |

| Demographics* | ||||

| Female % (n/N) | 63 (19/30) | 69 (55/81) | 60 (24/40) | 76 (31/41) |

| Age, years median (IQR) | 54 (23) | 51 (21) | 48.5 (13.5) | 54 (23) |

| BMI, median (IQR) | 27.0 (7.1) | 24.9 (5.4) | 25.6 (5.5) | 24.6 (5.2) |

| RA profile, % (n/N) | ||||

| CCP positive | N/A | 84 (64/76) | 82 (31/38) | 87 (33/38) |

| RF positive | N/A | 75 (57/76) | 68 (26/38) | 82 (31/38) |

| RA disease activity profile, median (IQR) | n=77 | n=39 | n=38 | |

| Baseline DAS28 score | N/A | 5.3 (1.4) | 5.5 (1.6) | 5.3 (1.4) |

| ESR | N/A | 30 (30) | 31 (33.5) | 30 (28.3) |

| CRP | N/A | 8 (23) | 8 (27) | 8 (17.8) |

| Traditional CV risk factors, % (n/N; unless otherwise stated) | ||||

| Hypertension | N/A | 7 (6/81) | 3 (1/40) | 12 (5/41) |

| Hypercholesterolaemia | N/A | 2 (2/81) | 0 (0/40) | 5 (2/41) |

| Diabetes | 0 (0/30) | 0 (0/81) | 0 (0/40) | 0 (0/41) |

| Family history IHD | N/A | 5 (4/81) | 5 (2/40) | 5 (2/41) |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg median (IQR) | 120.5 (13.5) | 121 (26) | 122 (24.5) | 120 (23) |

| Pack years smoking, years median (IQR) | 0 (0.4) | 0.1 (10) | 0 (5.3) | 3 (17.5) |

| Smoking status | n=30 | n=76 | n=38 | n=38 |

| Current | 13 (4/30) | 22 (17) | 16 (6) | 29 (11) |

| Former | 17 (5/30) | 33 (25) | 29 (11) | 37 (14) |

| Never | 70 (21/30) | 45 (34) | 55 (21) | 34 (13) |

*Denominator that is less than n=81 indicates missing data (not retrieved as original imputation model included gender).

BMI, body mass index; CCP, cyclic-citrullinated peptide; CRP, C-reactive protein; DAS28, Disease Activity Score-28; ERA, early rheumatoid arthritis; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; ETN, etanercept; IHD, ischaemic heart disease; MTX, methotrexate; NA, not applicable; RF, rheumatoid factor; TA1, immediate ETN and MTX treatment; TA2, first-line MTX±additional csDMARD.

Primary objectives

Patients versus controls

The primary outcome measure AD was 50% lower in ERA compared with controls (geometric mean 3.0×10−3 mm Hg−1, n=81 vs 4.4 × 10−3 mm Hg−1, n=30, respectively; ratio control:ERA (95% CI) 1.5 (1.2 to 1.8), p<0.01), table 2. This difference remained statistically significant when adjusted for age, sex, systolic blood pressure and pack years smoked.

Table 2.

Unadjusted and adjusted cardiovascular magnetic resonance variables in controls versus early rheumatoid arthritis RA at baseline (unadjusted, or adjusted for age, sex, systolic blood pressure and pack years smoked)

| Outcome | n | Control Unadjusted geometric mean (95% CI) |

Cases Unadjusted geometric mean (95% CI) |

Control/case, unadjusted geometric mean ratio (95% CI) |

P value | Control/case, adjusted geometric mean ratio (95% CI) |

P value |

| AD (10−3 mm Hg−1) | 111 | 4.4 (3.7 to 5.2) | 3.00 (2.7 to 3.3) | 1.5 (1.2 to 1.8) | <0.01 | 1.5 (1.3 to 1.7) | <0.01 |

| LVEF (%) | 111 | 61.6 (59.7 to 63.7) | 60.3 (59.2 to 61.5) | 1.0 (1.0 to 1.1) | 0.27 | 1.0 (1.0 to 1.1) | 0.38 |

| LVLS (cm/s) | 106 | 1.1 (1.1 to 1.2) | 1.1 (1.1 to 1.2) | 1.0 (1.0 to 1.1) | 0.76 | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.1) | 0.95 |

| PLVTw (°) | 106 | 15.3 (13.9 to 16.9) | 15.1 (14.1 to 16.0) | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.2) | 0.71 | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.2) | 0.69 |

| LV mass (g) | 111 | 92.9 (84.8 to 101.7) | 78.2 (74.0 to 82.6) | 1.2 (1.1 to 1.3) | <0.01 | 1.2 (1.1 to 1.3) | 0.03 |

| Native T1 (ms) | 108 | 1201.8 (1187.2 to 1216.5) | 1183.1 (1174.0 to 1192.2) | 1.0 (1.0 to 1.0) | 0.03 | 1.0 (1.0 to 1.0) | 0.06 |

| ECV (%) | 108 | 24.9 (23.8 to 26.1) | 27.2 (26.4 to 27.9) | 0.9 (0.9 to 1.0) | <0.01 | 0.9 (0.9 to 1.0) | <0.01 |

AD, aortic distensibility; ECV, myocardial extracellular volume; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVLS, left ventricular longitudinal strain; LV mass, left ventricular mass; PLVTw, peak left ventricular twist.

LV mass was 20% lower in ERA than controls (p<0.01). ECV was 10% higher in ERA versus controls (p<0.01). These differences remained statistically significant when adjusted for age, sex, systolic blood pressure and pack years smoked. No significant differences were seen between ERA versus controls in the other secondary outcome measures (table 2).

Matched pairs analyses corroborated the substantive and statistically significant differences between the control and ERA groups for AD and ECV; with consistent magnitude and direction in difference for LV mass (online supplementary table S3).

Baseline to 1-year change

AD improved by 20% from baseline to year 1 across the whole ERA cohort (geometric mean 3.0×10−3 mm Hg−1 vs 3.6×10−3 mm Hg−1, respectively; year 1:baseline ratio (95% CI) 1.2 (1.1 to 1.3), (p<0.01)), table 3. Seven patients were hypertensive at baseline and all on medication. None had a change/escalation in antihypertensive therapy through the course of the study aside from one patient who had to stop due to an AE.

Table 3.

Summary of baseline to year 1 outcomes for the whole early rheumatoid arthritis group

| Outcome | Geometric mean (95% CI) Baseline |

Geometric mean (95% CI) 1 year |

Ratio (95% CI), P value |

| AD (10−3 mm Hg−1) | 3.0 (2.7 to 3.4) | 3.6 (3.1 to 4.1) | 1.2 (1.1 to 1.3), <0.01 |

| LVEF (%) | 60.3 (59.1 to 61.6) | 59.9 (58.5 to 61.5) | 1.0 (1.0 to 1.0), 0.54 |

| LVLS (cm/s) | 1.1 (1.1 to 1.2) | 1.1 (1.1 to 1.2) | 1.0 (1.0 to 1.1), 0.84 |

| PLVTw (°) | 14.9 (13.9 to 15.8) | 14.6 (13.7 to 15.7) | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.1), 0.69 |

| LV mass (g) | 78.2 (73.7 to 82.9) | 81.4 (76.3 to 86.9) | 1.0 (1.0 to 1.1), 0.01 |

| Native T1 (ms) | 1183.92 (1174.44 to 1193.48) | 1185.39 (1168.99 to 1202.02) | 1 (0.99 to 1.02), 0.87 |

| ECV (%) | 27.2 (26.4 to 28.1) | 26.4 (25.6 to 27.1) | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.0), 0.06 |

n=81 with imputation for missing baseline or follow-up values.

AD, aortic distensibility; ECV, myocardial extracellular volume; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVLS, left ventricular longitudinal strain; LV mass, left ventricular mass; PLVTw, peak left ventricular twist.

LV mass geometric mean (95% CI) showed a modest, significant increase from baseline to 1 year (78.2 g/m2 (73.7 to 83.0) to 81.4 g/m2 (76.3 to 86.9); year 1:baseline ratio (95% CI) 1.0 (1.0 to 1.1), (p=0.01)). There were no significant changes in the other secondary outcome measures between baseline and 1-year follow-up (table 3).

Secondary objectives

Between the two treatment groups, there was no statistically significant difference in the change of AD from baseline to year 1 (table 4) or for the secondary outcome measures, LV mass and ECV (online supplementary tables S4 and S5, respectively). There were no differences between all responders and non-responders, and between first-line ETN +MTX responders and non-responders (all adjusted for baseline AD, age and sex; table 4). To clarify this apparent absence of effect of disease activity represented by response status, correlation analyses between AUC disease activity and AD at year 1 in the combined ERA group (online supplementary table S6), and between each treatment arm (online supplementary table S7) also did not identify an association. Comparison of first-line ETN +MTX responders with first-line MTX-TT responders (who therefore did not require ETN) indicated an unadjusted difference in geometric mean AD of 30% (0.7 (0.4 to 1.2)), 20% when adjusted for baseline AD (0.8 (0.5 to 1.2)), and 10% when adjusted for possible confounders (0.9 (0.60 to 1.18)), not statistically significant (table 4).

Table 4.

Aortic distensibility (AD) between baseline and year 1

| Comparison | AD (10−3 mm Hg−1) Geometric mean (95% CI), (unadjusted) |

Ratio (95% CI), P value | ||||

| Unadjusted | Adjusted 1 | Adjusted 2 | ||||

| Combined TA1 and TA2 (n=81) Baseline 1 year |

3.0 (2.7 to 3.4) 3.6 (3.1 to 4.1) | 1.2 (1.1 to 1.3), <0.01 | na | na | ||

| TA1 at 1 year (all n=40) |

TA2 at 1 year (all n=41) |

3.8 | 3.4 | 0.9 (0.7 to 1.2), 0.49 | 0.9 (0.7 to 1.2), 0.42 | 0.9 (0.8 to 1.2), 0.56 |

| Combined TA1 and TA2 at 1 year (non-responders n=38) |

Combined TA1 and TA2 at 1 year (responders n=43) | 3.5 | 3.6 | 1.0 (0.8 to 1.4), 0.87 | 1.0 (0.8 to 1.2), 0.79 | 1.0 (0.8 to 1.2), 0.86 |

| TA1 at 1 year (non-responders n=17) |

TA1 at 1 year (responders n=23) | 3.6 | 3.9 | 1.1 (0.7 to 1.6), 0.73 | 1.0 (0.7 to 1.3), 0.84 | 1.0 (0.7 to 1.3), 0.82 |

| TA1 at 1 year (responders n=23) |

TA2a at 1 year (responders n=13) | 3.9 | 2.8 | 0.7 (0.4 to 1.2), 0.19 | 0.8 (0.5 to 1.2), 0.29 | 0.9 (0.6 to 1.4), 0.56 |

Differences between groups, either unadjusted, adjusted for baseline AD or (additionally) adjusted for age, sex, systolic blood pressure and pack years smoking (±baseline Disease Activity Score with 28 joint count erythrocyte sedimentation rate (DAS28ESR) as applicable).

Response assumed for patients whose responder status at 48 weeks was unknown.

Adjusted 1, adjusted for baseline AD; Adjusted 2, adjusted for baseline AD, age, sex, systolic BP and pack years smoking (± baseline DAS28ESR as applicable); non-responders, patients with DAS28≥2.6 at 48 weeks; responders, patients with DAS28 <2.6 at 48 weeks; TA1, immediate etanercept (ETN) and methotrexate (MTX) treatment; TA2, first-line MTX ± additional conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; TA2a, TA2 patients that continued csDMARD and did not escalate to delayed ETN/MTX at week 24.

2-year outcomes

The geometric mean for AD improved by 10% from baseline to year 2 (3.0 × 10−3 mm Hg−1 vs 3.6×10−3 mm Hg−1, respectively; year 2:baseline ratio (95% CI) 1.1 (1.0 to 1.4), p=0.05; table 5). As in year 1 analysis, there were no differences between responders and non-responders (table 5). The increase in LV mass remained significant from baseline to year 2 follow-up (78.2 (73.7 to 82.9) 85.5 (79.0 to 92.6); ratio (95% CI) year 2:baseline 1.1 (1.0 to 1.2), p=0.02), online supplementary table S8. Of the other secondary outcome measures, PLVTw showed a 10% difference from baseline to 2-year follow-up; ratio year 2:baseline 1.1 (1.0, 1.2), (p=0.02), online supplementary table S8. There were no differences between the treatment arms. No other parameters showed statistically significant changes at 2-year follow-up (online supplementary table S8).

Table 5.

Aortic distensibility (AD) baseline and 2 years

| Comparison | AD (10−3 mm Hg−1) Geometric mean (95% CI) (unadjusted) |

Ratio (95% CI), P value | ||||

| Unadjusted | Adjusted 1 | Adjusted 2 | ||||

| Combined TA1 and TA2 (n=81) Baseline 2 years |

3.0 (2.7 to 3.4) 3.6 (3.1 to 4.1) | 1.1 (1 to 1.4), 0.05 | na | na | ||

| TA1 at 2 years (all n=40) |

TA2 at 2 years (all n=41) |

3.7 | 3.4 | 0.9 (0.7 to 1.2), 0.59 | 0.9 (0.7 to 1.2), 0.6 | 0.9 (0.7 to 1.2), 0.65 |

| Combined TA1 and TA2 at 2 years (non-responders n=38) |

Combined TA1 and TA2 at 2 years (responders n=43) | 3.5 | 3.6 | 1.0 (0.8 to 1.4), 0.83 | 1.0 (0.8 to 1.4), 0.91 | 1.0 (0.7 to 1.4), 0.95 |

| TA1 at 2 years (non-responders n=17) |

TA1 at 2 years (responders n=23) | 3.5 | 3.8 | 1.1 (0.7 to 1.7), 0.75 | 1.1 (0.6 to 1.7), 0.83 | 1.1 (0.6 to 1.8), 0.83 |

| TA1 at 2 years (responders n=23) |

TA2a at 2 years (responders n=13) | 3.8 | 3.4 | 0.9 (0.6 to 1.4), 0.56 | 0.9 (0.6 to 1.5), 0.70 | 0.9 (0.5 to 1.6), 0.70 |

Differences between groups, either unadjusted, adjusted for baseline AD or (additionally) adjusted for age, sex, systolic blood pressure and pack years smoking (±baseline DAS28ESR as applicable).

Response assumed for patients whose responder status at 48 weeks was unknown.

AD, aortic distensibility (10-3mm Hg-1); Adjusted 1, adjusted for baseline AD; DAS28-ESR, Disease Activity Score-28 erythrocyte sedimentation rate; non-responders, patients with DAS28 >/=2.6 at 48 weeks; responders, patients with DAS28 <2.6 at 48 weeks; TA1, immediate etanercept (ETN) and methotrexate (MTX) treatment; TA2, first-line MTX ± additional conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (csDMARD); TA2a, TA2 patients that continued csDMARD and did not escalate to delayed ETN/MTX at week 24.

Ten patients with RA had abnormal findings on LGE imaging and/or follow-up CMR. In eight patients, inferior RV insertion point enhancement was seen (generally considered a non-specific finding) and in two patients there was septal enhancement. All patients had normal stress/rest perfusion with no regional inducible perfusion defects.

Discussion

We report on the first RCT-based study to assess the effect of contemporary RA treatment strategies on preclinical CVD in patients with treatment-naïve ERA and no history of CVD. At time of diagnosis, compared with controls, patients with ERA show reduced vascular distensibility (AD, a surrogate for increased risk of CVD), evidence of diffuse myocardial fibrosis (increased ECV) and reduced LV mass. Introduction of either of the tested RA DMARD strategies improved AD at 1-year and 2-year follow-up, and first-line ETN+MTX was not superior to initial MTX-TT. Treatment response and cumulative disease activity do not appear to add to this improvement in AD.

Previous observational studies in established RA have shown reduced AD19 20 and abnormal LV remodelling and function21 22 with improvement following therapy.9 23 Aside from one small study,24 none have reported on myocardial and vascular function in treatment-naive ERA and change with randomised RA treatments. This study capitalised on a real-life, ERA, DMARD and prior corticosteroid-naive RCT and interrogated multiple CV parameters. Patients had no history of CVD, no CV symptoms, were in NYHA Class 1 and those with diabetes mellitus and/or more than one CVD risk factor were excluded. All analyses were adjusted for age and gender, the principal drivers of vascular stiffness, and blood pressure and smoking where indicated.

The choice of AD as the primary endpoint in this study was based on its ability to predict major CV events independently of traditional clinical risk scoring models in patients without known CVD,17 25 its high reproducibility18 and previous use in a pilot study in RA.19 The predictive ability of AD is thus of particular advantage in this asymptomatic CVD population. The presence of abnormal vascular stiffness (adjusted for known risks including blood pressure) at the earliest stage of diagnosis of RA highlights the increased risk in this population.

Myocardial ECV is a measure of diffuse myocardial fibrosis and an indicator of adverse outcome in several forms of heart disease.26 Increased ECV has been reported in established RA.27 Our observation that ECV is already increased on diagnosis of ERA suggests a period of latent myocardial involvement before clinical presentation of RA. We observed non-ischaemic areas of focal fibrosis (LGE) in just over 10% of patients, although all except two had non-specific RV insertion point fibrosis only. A previous report in established RA reported much more common focal fibrosis (46%),27 suggesting progression of this finding over time in RA. Our observation of reduced LV mass at baseline adds to literature consistent with21 22 and in contrast to ours.28 29 Further investigation including cardiometabolic changes30 is needed to clarify these apparent contradictions. Measures of LV function and strain however were not impaired compared with the control population. These indices likely reflect the consequences of abnormal pathophysiological processes, which are more likely to affect patients with long-standing RA.27 This and, similarly, the absence of visual perfusion defects would be less likely to be captured in our asymptomatic cohort.

RA treatment (without addition of prognostic cardiac pharmacotherapy) improved CV abnormalities within a year of protocolised treatment, still evident at the end of year 2. AD improved (by 20% at year 1), which broadly translates to HRs of 1.12 (composite events) and 1.13 (non-fatal cardiac events), that is, reductions of 12% and 13%, respectively.25 The measured effect on AD was not confounded by any increase in antihypertensive medication during the study. Of the secondary outcomes (not powered for) ECV showed the greatest potential for improvement. Future larger, longitudinal studies in RA can confirm the basis for raised myocardial ECV, the prognostic implication and whether RA treatment improves ECV.

First-line ETN+MTX was not significantly superior to initial MTX-TT strategy in improving AD and there was no clear relationship between the improvement in vascular stiffness and RA response. Remission defined response status, aligned with the primary endpoint of the associated VEDERA RCT although holds potential weaknesses.12 However, we also did not identify an association with cumulative burden of disease activity, nor did change in AD correlate with change in ESR or CRP (data not shown). Previous studies to report on such associations have been contradictory.31 32 It is conceivable that an association may not be observed with arterial stiffening that is an integration of several processes of the structural and cellular elements of the vessel wall and not solely due to inflammation.

Collectively, these data speak to several study findings33 34 indicating benefits of RA therapies not only include effect on systemic inflammation,35 but cardiometabolic profile36 and a targeted effect on key immune mediators of CVD. Similarly, a prospective cohort study suggested that after accounting for other risk factors and treatment response, subjects actively receiving bDMARDs experienced lower CV event risk, which was not observed in those who discontinued.37 The concept of targeted therapeutics in atherosclerosis is indirectly supported by seminal genetic and experimental studies and recent trials of blockade of IL-1 and MTX.6

These data have wider implications on RA management strategies including DMARD tapering. While this study was not designed to address this, by demonstrating improvement in CV markers, and until further data are available, this should be considered if contemplating drug tapering.

The principal limitation of our study is the use of surrogate markers for CV risk. However, early termination of a study that recruited over 3000 patients8 emphasises this reality in the investigation of CVD in RA. Also, a longer, observational evaluation would inform on the pathophysiological sequence of events in relation to RA disease course and future events. Our study was not designed to assess for the known deleterious effects of corticosteroid38 and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) comedication, however, equivalent corticosteroid usage across both treatment arms ensures balance in any possible interaction.12

In summary, this is a first RCT-derived longitudinal study in a new onset, treatment-naïve ERA cohort with no history of CVD. This study demonstrated the presence of CV abnormalities at the earliest stage of RA and the ability of RA therapy to improve vascular stiffness. This improvement was not however associated with response status and disease activity burden.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the patients for participating in this study. Also, the clinical rheumatology and cardiology staff at Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust for identifying patients. Gratitude to Petra Bijsterveld, senior research nurse for coordinating the cardiac MRI scans. Finally, the trials administration team led by James Goulding.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Josef S Smolen

Contributors: The trial was conceived by MHB, SP and SP. PB and EMAH were principal statisticians for this cardiovascular substudy and VEDERA, respectively. SP and MHB provided overall responsibility for the research methodology and statistical analysis plan. BE and GF were the the principal clinical fellows on this cardiovascular substudy and SH, RBD and Naragi were the clinical research fellows on VEDERA. MHB drafted the manuscript, with critical input from PB and SP. All authors had the opportunity to further revise the manuscript and approved the final version.

Funding: This study was supported through a National Institute for Health Research (Efficacy Mechanism Evaluation 11/117/27) grant. Pfizer supported the parent study, ‘VEDERA’, via an investigator sponsored research grant reference WS1092499. This article/paper/report presents independent research funded/supported by the National Institute for Health Research Leeds Biomedical Research Centre.

Disclaimer: The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Competing interests: PE has received consultant fees from AbbVie, BMS, Eli Lilly, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Samsung, Sandoz and UCB and received research grants paid to his employer from AbbVie, BMS, Pfizer, MSD and Roche. MHB has provided expert advice and received consultant fees from AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, EMD Serono, Pfizer, Roche, Sandoz, Sanofi and UCB and has received research grants paid to her employer from Pfizer Bristol-Myers Squibb, Roche, UCB.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The single-centre study was undertaken at Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust rheumatology and cardiology departments according to the Declaration of Helsinki, with approval from the National Research Ethics Service (Leeds (West) Research Ethics Committee (reference 10/H1307/138; Current Controlled Trials (registration number: ISRCTN50167738))).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available upon reasonable request. All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information. Additional data are available upon reasonable request.

References

- 1. Avina-Zubieta JA, Thomas J, Sadatsafavi M, et al. . Risk of incident cardiovascular events in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Ann Rheum Dis 2012;71:1524–9. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nicola PJ, Crowson CS, Maradit-Kremers H, et al. . Contribution of congestive heart failure and ischemic heart disease to excess mortality in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:60–7. 10.1002/art.21560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Peters MJL, van Halm VP, Voskuyl AE, et al. . Does rheumatoid arthritis equal diabetes mellitus as an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease? A prospective study. Arthritis Rheum 2009;61:1571–9. 10.1002/art.24836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. del Rincón I, Polak JF, O'Leary DH, et al. . Systemic inflammation and cardiovascular risk factors predict rapid progression of atherosclerosis in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:1118–23. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-205058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Crowson CS, Rollefstad S, Ikdahl E, et al. . Impact of risk factors associated with cardiovascular outcomes in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2018;77:48–54. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-211735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zhao TX, Mallat Z. Targeting the immune system in atherosclerosis: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019;73:1691–706. 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.12.083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ridker PM, Everett BM, Thuren T, et al. . Antiinflammatory therapy with canakinumab for atherosclerotic disease. N Engl J Med 2017;377:1119–31. 10.1056/NEJMoa1707914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kitas GD, Nightingale P, Armitage J, et al. . A multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of atorvastatin for the primary prevention of cardiovascular events in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2019;71:1437–49. 10.1002/art.40892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ntusi NAB, Francis JM, Sever E, et al. . Anti-Tnf modulation reduces myocardial inflammation and improves cardiovascular function in systemic rheumatic diseases. Int J Cardiol 2018;270:253–9. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.06.099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fent GJ, Greenwood JP, Plein S, et al. . The role of non-invasive cardiovascular imaging in the assessment of cardiovascular risk in rheumatoid arthritis: where we are and where we need to be. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:1169–75. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Erhayiem B, Pavitt S, Baxter P, et al. . Coronary artery disease evaluation in rheumatoid arthritis (CADERA): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2014;15:411–36. 10.1186/1745-6215-15-436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Emery P, Horton S, Dumitru RB, et al. . Pragmatic randomised controlled trial of very early etanercept and MTX versus MTX with delayed etanercept in RA: the VEDERA trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2020;79:464–71. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-216539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Smolen JS, Breedveld FC, Burmester GR, et al. . Treating rheumatoid arthritis to target: 2014 update of the recommendations of an international Task force. Ann Rheum Dis 2016;75:3–15. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-207524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Aletaha D, Neogi T, Silman AJ, et al. . 2010 rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria: an American College of Rheumatology/European League against rheumatism collaborative initiative. Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69:1580–8. 10.1136/ard.2010.138461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Messroghli DR, Moon JC, Ferreira VM, et al. . Clinical recommendations for cardiovascular magnetic resonance mapping of T1, T2, T2* and extracellular volume: a consensus statement by the Society for cardiovascular magnetic resonance (SCMR) endorsed by the European association for cardiovascular imaging (EACVI). J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2017;19:1–24. 10.1186/s12968-017-0389-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Blacher J, Fournier V, Asmar R, et al. . Aortic pulse wave velocity as a marker of atherosclerosis in hypertension. Cardiovasc Rev Reports 2001;22:420–5. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Swoboda PP, Erhayiem B, Kan R, et al. . Cardiovascular magnetic resonance measures of aortic stiffness in asymptomatic patients with type 2 diabetes: association with glycaemic control and clinical outcomes. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2018;17:1–9. 10.1186/s12933-018-0681-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Graham-Brown MPM, Adenwalla SF, Lai FY, et al. . The reproducibility of cardiac magnetic resonance imaging measures of aortic stiffness and their relationship to cardiac structure in prevalent haemodialysis patients. Clin Kidney J 2018;11:864–73. 10.1093/ckj/sfy042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ikonomidis I, Lekakis JP, Nikolaou M, et al. . Inhibition of interleukin-1 by anakinra improves vascular and left ventricular function in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Circulation 2008;117:2662–9. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.731877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ntusi NAB, Piechnik SK, Francis JM, et al. . Subclinical myocardial inflammation and diffuse fibrosis are common in systemic sclerosis--a clinical study using myocardial T1-mapping and extracellular volume quantification. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2014;16:21. 10.1186/1532-429X-16-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Giles JT, Malayeri AA, Fernandes V, et al. . Left ventricular structure and function in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, as assessed by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. Arthritis Rheum 2010;62:940–51. 10.1002/art.27349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Myasoedova E, Davis JM, Crowson CS, et al. . Brief report: rheumatoid arthritis is associated with left ventricular concentric remodeling: results of a population-based cross-sectional study. Arthritis Rheum 2013;65:1713–8. 10.1002/art.37949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mavrogeni S, Markousis-Mavrogenis G, Koutsogeorgopoulou L, et al. . Cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging pattern at the time of diagnosis of treatment naïve patients with connective tissue diseases. Int J Cardiol 2017;236:151–6. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.01.104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Løgstrup BB, Masic D, Laurbjerg TB, et al. . Left ventricular function at two-year follow-up in treatment-naive rheumatoid arthritis patients is associated with anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody status: a cohort study. Scand J Rheumatol 2017;46:432–40. 10.1080/03009742.2016.1249941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Maroules CD, Khera A, Ayers C, et al. . Cardiovascular outcome associations among cardiovascular magnetic resonance measures of arterial stiffness: the Dallas heart study. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2014;16:1–9. 10.1186/1532-429X-16-33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mewton N, Liu CY, Croisille P, et al. . Assessment of myocardial fibrosis with cardiovascular magnetic resonance. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;57:891–903. 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.11.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ntusi NAB, Piechnik SK, Francis JM, et al. . Diffuse myocardial fibrosis and inflammation in rheumatoid arthritis: insights from CMR T1 mapping. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2015;8:526–36. 10.1016/j.jcmg.2014.12.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Aslam F, Bandeali SJ, Khan NA, et al. . Diastolic dysfunction in rheumatoid arthritis: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Arthritis Care Res 2013;65:534–43. 10.1002/acr.21861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Amigues I, Russo C, Giles JT, et al. . Myocardial Microvascular Dysfunction in Rheumatoid ArthritisQuantitation by 13N-Ammonia Positron Emission Tomography/Computed Tomography. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2019;12:e007495. 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.117.007495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Summers GD, Metsios GS, Stavropoulos-Kalinoglou A, et al. . Rheumatoid cachexia and cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2010;6:445–51. 10.1038/nrrheum.2010.105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kullo IJ, Seward JB, Bailey KR, et al. . C-Reactive protein is related to arterial wave reflection and stiffness in asymptomatic subjects from the community. Am J Hypertens 2005;18:1123–9. 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2005.03.730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Aznaouridis KA, Stefanadis CI. Inflammation and arterial function☆. Artery Res 2007;1:32–8. 10.1016/j.artres.2007.03.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Karpouzas GA, Ormseth SR, Hernandez E, et al. . Biologics may prevent cardiovascular events in rheumatoid arthritis by inhibiting coronary plaque formation and stabilizing high-risk lesions. Arthritis Rheumatol 2020. 10.1002/art.41293. [Epub ahead of print: 21 Apr 2020]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Greenberg JD, Kremer JM, Curtis JR, et al. . Tumour necrosis factor antagonist use and associated risk reduction of cardiovascular events among patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:576–82. 10.1136/ard.2010.129916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Solomon JJ, Ryu JH, Tazelaar HD, et al. . Fibrosing interstitial pneumonia predicts survival in patients with rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease (RA-ILD). Respir Med 2013;107:1247–52. 10.1016/j.rmed.2013.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gonzalez-Gay MA, Gonzalez-Juanatey C, Vazquez-Rodriguez TR. Insulin resistance in rheumatoid arthritis: The impact of the anti-TNF-α therapy: Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences : Annals of the new York Academy of sciences. Blackwell Publishing Inc, 2010: 153–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lee JL, Sinnathurai P, Buchbinder R, et al. . Biologics and cardiovascular events in inflammatory arthritis: a prospective national cohort study. Arthritis Res Ther 2018;20 10.1186/s13075-018-1669-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Davis JM, Maradit Kremers H, Crowson CS, et al. . Glucocorticoids and cardiovascular events in rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based cohort study. Arthritis Rheum 2007;56:820–30. 10.1002/art.22418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

annrheumdis-2020-217653supp001.pdf (298.3KB, pdf)