Version Changes

Revised. Amendments from Version 1

We have revised the manuscript to address the comments and suggestions made by the reviewers. 1. In the Abstract: Background section, we have added costeffectiveness of child undernutrition treatment as one of the main aims of the review. 2. We have added a summary of results on cost-effectiveness of child undernutrition treatment in the Abstract: Results section. 3. We have included an explanation and justification of why we only included studies assessing treatment interventions in the Introduction section. 4. We have clarified the descriptive analysis approach used to assess the cost drivers in the statistical analysis section. 5. We have reworded our statement explaining the percentage of studies conducted per country and region in the subsection “Studies by region and continent.” 6. In the subsection “Economic evaluation by perspective” we have defined and described each perspective analysed and presented. 7. In the subsection “Community volunteers’ perspective” we have added information on an article “Puett et al. 2013” which also considers costs for community-based management of acute malnutrition (CMAM) delivered by community volunteers. 8. In Table 5 and Table 6, we have added the percentage (%) total mean cost per direct medical and non-medical costs for the health providers and program perspectives. 9. In the subsection CMAM we have added information on the average cost per child for the CMAM implemented in the community versus facility-based programs. 10. In the subsection “Limitations” we have added information on the challenges experienced comparing or standardizing costs and cost structures across settings and information on the most common principles that studies did not adhere to. 11. In the conclusion section, we have added recommendations on the need for studies to generate cost estimates of integrated programs from government delivered programs and the need to adhere to GHCC guidelines for comprehensive secondary analysis.

Abstract

Background: Undernutrition remains highly prevalent in low- and middle-income countries, with sub-Saharan Africa and Southern Asia accounting for majority of the cases. Apart from the health and human capacity impacts on children affected by malnutrition, there are significant economic impacts to households and service providers. The aim of this study was to determine the current state of knowledge on costs and cost-effectiveness of child undernutrition treatment to households, health providers, organizations and governments in low and middle-income countries (LMICs).

Methods: We conducted a systematic review of peer-reviewed studies in LMICs up to September 2019. We searched online databases including PubMed-Medline, Embase, Popline, Econlit and Web of Science. We identified additional articles through bibliographic citation searches. Only articles including costs of child undernutrition treatment were included.

Results: We identified a total of 6436 articles, and only 50 met the eligibility criteria. Most included studies adopted institutional/program (45%) and health provider (38%) perspectives. The studies varied in the interventions studied and costing methods used with treatment costs reported ranging between US$0.44 and US$1344 per child. The main cost drivers were personnel, therapeutic food and productivity loss. We also assessed the cost effectiveness of community-based management of malnutrition programs (CMAM). Cost per disability adjusted life year (DALY) averted for a CMAM program integrated into existing health services in Malawi was $42. Overall, cost per DALY averted for CMAM ranged between US$26 and US$53, which was much lower than facility-based management (US$1344).

Conclusion: There is a need to assess the burden of direct and indirect costs of child undernutrition to households and communities in order to plan, identify cost-effective solutions and address issues of cost that may limit delivery, uptake and effectiveness. Standardized methods and reporting in economic evaluations would facilitate interpretation and provide a means for comparing costs and cost-effectiveness of interventions.

Keywords: Economic burden, cost, cost effectiveness analysis, undernutrition, malnutrition, community-based, low and middle-income countries

Introduction

Malnutrition (undernutrition, overweight and micronutrient deficiencies) is a major underlying factor for mortality, morbidity and poor child development 1, 2. Undernutrition is associated with lower achievement in education, reduced employment achievement and health status in adulthood and low birthweight in offspring, creating an intergenerational cycle 2, 3. Worse effects in children are experienced during their first 1000 days, owing to their higher nutritional requirements and fragile nature 4, 5. Only a small fraction of these deficits is reversible during childhood and adolescence, especially if the children remain in impoverished environments 5, 6.

Despite efforts by national and international organizations, malnutrition rates remain alarmingly high. Undernutrition is estimated to cause approximately half of all under five deaths, close to 3.1 million deaths annually 4. Moderate and severe stunting and wasting affected close to 155 million and 17 million under five children, respectively, by 2016 7. The highest prevalence of wasting is in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), with sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia accounting for majority of cases 4. Poverty, adverse climatic conditions, policies, corruption, social cultural and religious factors are major contributing factors to the high prevalence of child undernutrition in sub-Saharan Africa 8.

Until recently, all children suffering from severe acute malnutrition (SAM) were treated as inpatients, which was a major limitation due to inaccessibility of health facilities 1, 9. In 2007, the World Health Organization (WHO) endorsed community-based management of acute malnutrition (CMAM) to treat uncomplicated SAM cases and moderate acute malnutrition (MAM) cases in the community 10. CMAM constitutes community mobilization, treating uncomplicated SAM and MAM cases as outpatients with ready-to-use therapeutic food (RUTF) and antimicrobials to treat infections 11. Cases with medical complications are still recommended to be admitted to inpatient units and are discharged to outpatient care once stabilized and feeding adequately, rather than full nutritional rehabilitation being conducted in the inpatient setting.

Economic impact

While there is a lot of research ongoing on the health and human impacts of child undernutrition, there is paucity of information on the economic impacts that necessitate further exploration. The long-term effects of undernutrition on the child’s economic potential translate to a reduction in national productivity 12. Studies show that children affected by malnutrition in early life risk losing a significant percentage of their lifetime earnings 13. For instance, a 1% less attained height is estimated to contribute to a reduction of 2.4% earnings in adulthood 13.

Malnutrition is responsible for an 11% yearly Gross National Product (GNP) loss in Africa and Asia 14. These economic losses are largely due to provider costs of treating undernutrition and its associated infections, reduced educational performance and lower agricultural activity 15. Thus, undernutrition is a major setback towards poverty eradication and attainment of sustainable development goals (SDGs). Support for nutrition interventions is an investment for the future. For instance, attainment of the 40% stunting reduction target by the World Health Assembly by 2025 could result in a cumulative addition Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of US$7 billion in Uganda 13.

Costs incurred by households with undernourished children have largely been ignored although such costs may exceed costs to the government 15, 16. This is predominantly due to the high expenditure on health care (out-of-pocket costs) during malnutrition treatment and indirect costs, including the opportunity cost of time spent away from normal duties while taking care of the sick children or attending clinics 15. To cover these costs, families may borrow or sell assets and be highly dependent on other family members and the community, majorly affecting their economic productivity.

The aim of this systematic review was to determine the current state of knowledge on the costs and cost-effectiveness of child undernutrition treatment(s) to households, health providers, organizations and governments in LMICs. The findings will inform health researchers, policy makers, non-governmental organisations and the private sector to plan, identify cost-effective solutions and address issues of cost to providers and households that may limit delivery, uptake and effectiveness. We only included studies that assessed the cost of treatment interventions (for children with anthropometrically defined wasting or kwashiorkor). Interventions ranging from supplementary feeding for children with moderate acute malnutrition and therapeutic feeding and other treatments for children with severe acute malnutrition, including during community-based management of severe acute malnutrition (CMAM) as well as facility-based outpatient and inpatient treatment. We excluded prevention interventions, screening and treating micronutrient deficiencies as they are broader topics worthy of their own reviews.

Methods

Information sources

This systematic review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines 17. We conducted a literature search for all studies published in English or French up to September 2019 in the following electronic databases; PubMed-Medline, Embase, Popline, Econlit and Web of Science. We also sought additional published articles through Google Scholar and bibliographic citation searches.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We included articles that (1) were published in English or French; (2) involved treatment interventions for anthropometric undernutrition; (3) had children (below 18 years) as the sample in the study; (4) had cost components or involved economic evaluation and; (5) were conducted in low and middle-income countries.

We excluded articles that did not meet our criteria in two stages. At the initial stage (by title and abstracts) if the study involved an adult population, was done in a high-income country, included overweight/obesity or involved micronutrient deficiencies with no anthropometric undernutrition. At the second stage (full article review) if the article was a study protocol, had reported global cost estimates of child undernutrition treatment or was a review article.

Search strategy

We used the National Health Service Centre for Reviews and Dissemination 18 recommendations to develop a search strategy where the review question was broken down to search terms ( Table 1). We also used Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms in addition to the main search terms. We combined the search terms using Boolean operators such as “AND” and “OR” as necessary.

Table 1. Search terms as included in the databases.

| (cost OR “financial burden” OR “economic burden” OR “financial cost” OR “economic cost” OR expens* OR expend* OR spending)

AND (malnutrition OR undernutrition OR undernourish* OR malnourish* OR wasting OR “wasted” OR SAM OR MAM OR “Severe Acute Malnutrition” OR “Moderate Acute Malnutrition” OR kwashiorkor OR “nutritional oedema” OR “nutritional edema") AND (child OR children OR baby OR babies OR infant OR infants) |

Screening of articles

We exported and combined articles retrieved from the different databases in Endnote X8 19 to remove duplicates. We used the Rayyan web app 20 for screening of the articles. Two reviewers screened the titles and abstracts independently. We resolved disagreements by consensus. The process was repeated for full article review until relevant articles were selected.

Data extraction

We collected all relevant information required for analysis using a data extraction template designed in Microsoft Excel 2013. We extracted details on author, year of publication, country, data year, number of children, age range of the children, the study perspective, the time horizon (period between data collection and analysis), type of economic evaluation conducted, analytical approach used, intervention/s studied, comparator/s, cost per DALYs, cost per life years saved, cost per case averted, incremental cost effectiveness ratio (ICER), direct medical costs, direct non-medical costs, indirect costs, total costs, coping strategies and cost drivers.

Quality assessment of the studies

We assessed the quality of the included studies using the Global Health Cost Consortium (GHCC) guidelines 21. The GHCC guidelines consist of 17 items within four main sections designed to evaluate costing studies: 1) study design and scope, 2) service and resource use measurement, 3) valuation and pricing, 4) analyzing and presenting results. Each item was rated by the extent of reporting in the following categories: “1=satisfied” or “0=not satisfied” and “X=not applicable”. For each reviewed study, the “not applicable” rating was acceptable for three items in the GHCC guidelines: “Amortization of capital costs”, “Discounting and inflation” and “use of shadow prices”. This was because amortization of capital costs, discounting and inflation only applies for studies reporting costs over a period of more than one year while use of shadow prices applies for studies valuing inputs without market prices. The total number of articles reporting by each item was then summed up.

Cost and cost-effectiveness analysis

We classified the extracted cost data into direct medical, direct non-medical and indirect costs. The direct medical costs included expenditure on medication (drugs and diagnostic tests), supplementary feeds (therapeutic food), capital (buildings, equipment and supplies), personnel (staff salaries) and administrative costs (training, monitoring and supervision of activities and consultation fees). Direct non-medical costs included travel, food expenses for caregivers and any other person accompanying them and costs incurred to cover household chores usually done by the families. Indirect costs included the opportunity cost of time the guardians or caregivers spent away from their daily productive routine. We also reviewed data on the cost-effectiveness of CMAM compared to facility based management of malnutrition. We extracted data on cost per DALY gained/averted, cost per life year saved and cost per child treated/recovered from the included studies.

Statistical analysis

We used R version 3.4.1 22 for all statistical analyses. We converted all costs to US dollars using a currency converter 23 for each data year reported. We reported the means, medians and ranges of the direct and indirect costs according to the perspectives adopted by the included studies. The mean and median costs reported were used to assess the main cost drivers for each perspective. We also reviewed coping strategies reported by the included articles. A comprehensive meta-analysis for comparison of costs across the included studies was not done due to hetereogeneity in the costing methods and the interventions assessed.

Results

Search results

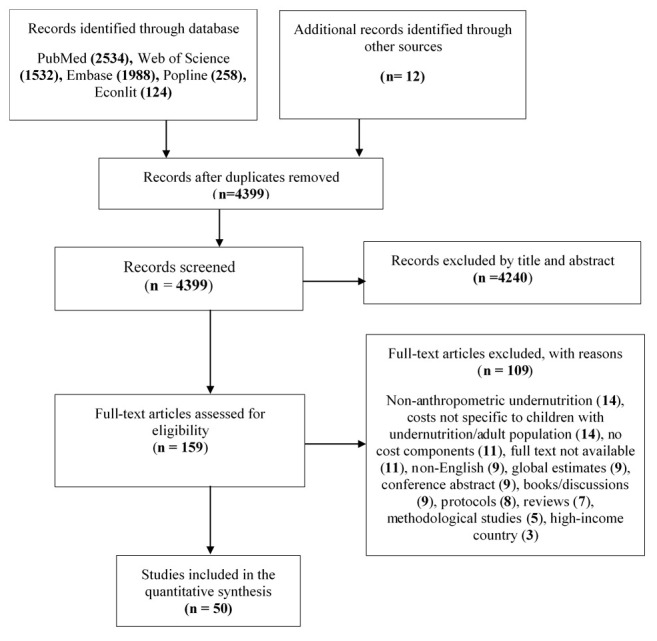

The literature search yielded 6436 articles: 6424 titles and abstracts through database searching and an additional 12 records through bibliographic citation searches. A total of 4399 articles (excluding duplicates) were selected for title and abstract evaluation. Full-text articles were then obtained for the 159 articles considered potentially eligible for inclusion and full-text articles were obtained; 50 of which met the inclusion criteria ( Table 2). We excluded 109 articles after full article review, mostly with no anthopometric undernutrition or no cost components. Figure 1 shows the flow of selection and inclusion of the studies.

Table 2. Characteristics of the included studies in the review.

| No | Author | Year | Country | Study design | Type of

economic evaluation |

Perspective

of study |

Analytical

approach |

Intervention | Sample

size(n) |

Age

(months) |

Economic

Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Abdul-Latif et al. 31 | 2014 | Ghana | Retrospective

cross-sectional study |

Cost analysis | Societal | Activity-

based costing |

Community-based

management of SAM |

40 | 6 to 59 | Cost per child:

$805.36 |

| 2 | Ackatia et al. 32 | 2015 | Mali | Cluster

randomized trial |

Cost analysis | Provider | NR | Supplementary feeds

(community-based) a) RUSF b) CSB++ c) Locally processed, fortified flour (Misola) d) LMF |

a)344;

b)349; c)307; d)284; |

6 to 35 | Cost of

supplements;: a) $0.38 for 92g b) $0.22 for 127g c) $0.21 for 125 g d) LMF =$0.18 for 129 g. |

| 3 | Akram et al. 33 | 2016 | Pakistan | Retrospective

cohort |

Cost analysis | Program | NR | Nutritional rehabilitation

(home based-high density diet, parental counselling & monitoring) |

123 | 15.5 ± 8.5 | Total cost

per child for rehabilitation: $34.31 100g of high density diet cost $0.22 |

| 4 | Ashworth et al. 34 | 1997 | Bangladesh | Longitudinal,

prospective and controlled trial |

Cost-

effectiveness |

Institutional

& parental |

Bottom-up

approach |

a) Inpatient

management b) Day care c) Domiciliary |

437 | 12 to 60 | a) $159

b) $63.8 c) $38.8 |

| 5 | Bachmann 35 | 2009 | Zambia | Decision analytical

modelling |

Cost-

effectiveness |

Healthcare

care providers |

Modelling

approach |

Community-based

therapeutic care (CTC) vs hypothetical no treatment |

2523 | <60 | Mean cost per

child was $203 CTC cost $53 per DALY gained and $ 1760 per life year saved |

| 6 | Bai 36 | 1972 | India | Prospective cohort | Cost analysis | Hospital and

families |

NR | Domiciliary

management of PEM (special diet) |

25 | <60 | Hospital costs Rs.

525 Parent costs = Rs. 100–150 |

| 7 | Bagriansky et al. 29 | 2014 | Cambodia | Model study

of economic losses due to malnutrition |

Government | Modelling

approach |

- | - | Economic losses

due to; Wasting = $18.8 Underweight = $22.3 Stunting = $128 |

||

| 8 | Bredow et al. 37 | 1994 | Jamaica | Prospective cohort | Cost analysis | Healthcare

care providers |

NR | Community based

approach to treatment of SAM (dietary advice, antibotics, anthelminthics & vitamin supplements) |

36 | <36 | Medication cost

US$14 per child for every six months Milk and fat food cost US$2 |

| 9 | Chapko et al. 38 | 1994 | Niger | Randomized

clinical trial |

Cost analysis | Healthcare

care providers |

Bottom-up

approach |

Hospital vs ambulatory

nutitional rehabilitation |

100 | 5 to 28 | a) Hospital= 760

FCFA/patient/day b) Ambulatory = 720 FCFA/patient/ day The mean cost for; a) Hospital rehabilitation = 22881 FCFA b) Ambulatory = 10387 FCFA |

| 10 | Cobb et al. 39 | 2013 | South Africa | Retrospective

cohort |

Cost analysis | Program | Bottom-up

approach |

WHO Nutritional care

plans a) NCP-B for MAM b) NCP-C + NCP-B for SAM |

Total= 113

MAM (88) SAM (25) |

6 to 168 | The cost per child

(MAM) = $66.56 The cost per child (SAM) = $211.04 |

| 11 | Colombatti et al. 40 | 2008 | Guinea Bissau | Prospective cohort | Cost analysis | Health care

provider |

NR | Outpatient treatment +

locally produced food |

2642 | 51.6 | The overall cost of

the intervention was €13,448 |

| 12 | Daga et al. 41 | 2010 | India | Prospective cohort

study |

Cost analysis | Bottom-up | Treatment using drugs | 111 | 1 to >60 | The average cost

per patient was $4 |

|

| 13 | Fernandez et al. 42 | 1991 | Peru | Observational | Cost analysis | Program | Bottom-up | Nutrition rehabilitation

(education & child diet) |

54 | 1 to 36 | Cost per child =

$21 |

| 14 | Fronczak et al. 43 | 1993 | Bangladesh | Cross sectional | Cost analysis | Program | Bottom-up | Nutritional rehabilitation | 161 | 6 to 59 | Average cost per

child was $140 |

| 15 | Garg et al. 44 | 2018 | India | Randomized

clinical trial |

Cost analysis | Research &

government |

Price times

quantity approach |

Supplementary

feeding: a) Centrally produced RUTF (RUTF-C) b) Locally produced RUTF (RUTF-L) c) Augmented, energy dense, home prepared food (A-HPF) |

a) 124

b) 124 c) 123 |

6 to 59 | Research costs

per child: RUTF-C = $227 RUTF-L = $229 A-HPF = $238 Government costs: RUTF-C = $53 RUTF-L = $54 A-HPF = $61 |

| 16 | Ghoneim et al. 45 | 2004 | Egypt | Longitudinal,

prospective |

Cost analysis | Top-down

approach |

Nutrition rehabilitation

(nutrition education and diet) |

974 | 24 to 60 | Cost per child per

year was US$20.5 |

|

| 17 | Glenn P Jenkins 46 | 2013 | Uganda | Analytical

modelling |

Cost-

effectiveness |

Program | Modelling

approach |

Treatment with

therapeutic feed |

36907 | - | Cost per child

was $144.48 Cost per DALY gained was $36.27 |

| 18 | Goudet et al. 47 | 2018 | India | Cohort | Cost-

effectiveness |

Program &

household |

Activity-based

costing |

Aahar acute

malnutrition programme vs standard care |

12362 | 0 to 36 | Cost per child was

$27.11 Cost per death averted was $12360 Cost per DALY averted was $23 |

| 19 | Greco et al. 48 | 2006 | Uganda | Cohort | Cost analysis | Program | Bottom-up

approach |

Supplementary feeding

(locally available Ingredients) |

250–300 | 6 to 72 | The low-cost

porridge supplement (€2640/year/100 children) |

| 20 | Hoddinott et al. 25 | 2013 | a) DRC

b) Madagascar c) Ethiopia d) Uganda e) Tanzania f) Kenya g) Sudan h) Nigeria I) Yemen j) Nepal k) Bangladesh l) Pakistan m) India n) Vietnam o) Philippines p) Indonesia |

Model study | Benefit cost

ratios |

Government | Modelling

approach |

Reducing stunting

based on Bhutta et al. 2013 interventions |

a) DRC = 3.8

b) Madagascar = 9.8 c) Ethiopia = 10.6 d) Uganda = 13 e) Tanzania = 14.6 f) Kenya = 15.2 g) Sudan = 23 h) Nigeria = 24.4 I) Yemen = 28.6 j) Nepal = 12.9 k) Bangladesh = 17.9 l) Pakistan = 28.9 m) India = 38.6 n) Vietnam = 35.3 o) Philippines = 43.8 p) Indonesia = 47.7 |

||

| 21 | Hossain et al. 49 | 2009 | Bangladesh | Cohort | Cost analysis | Hospital and

program |

Bottom-up

approach |

WHO

recommendation(acute phase & nutritional rehab phase) |

171 | 23.5 ±

15.3 |

Food= $6.1

Medicines= $8.5 Total(US$ 14.6 per child |

| 22 | Isanaka et al. 50 | 2016 | Niger | Retrospective

cohort |

Cost analysis | Provider | Activity-based

costing and Ingredients approach |

Community-based

treatment of SAM (CMAM, integrated) |

16084 | <60 | Overall cost of the

CMAM program = €148.86 per child a) Outpatient treatment cost = €75.50/child b) Inpatient treatment cost = €134.57/child c) Management and administration costs were €40.38/child |

| 23 | Isanaka et al. 51 | 2019 | Mali | Cluster-

randomized trial |

Cost-

effectiveness |

Provider | Activity-based

costing |

Supplementary feeds:

a) RUTF b) CSB++ c) Misola d) Locally milled flour vse) Treatment of SAM only |

1264 | 6 to 35 | Cost per child:

a) $17.25 b) $8.10 c) $7.85 d) $8.50 e) 165Cost per DALY averted a) $347 b) $446 c) $490 d) $630 e) 142Cost per death averted a) $9821 b) $12435 c) $13146 d) $17486 e) 3974 |

| 24 | Kielman et al. 52 | 1978 | India | Longitudinal and

cross-sectional |

Cost-

effectiveness |

Program | Activity-based

costing |

a) Nutritional care

(NUT) b) Medical care (MC) c) NUT + MC d) Control |

2900 | <36 | Total service costs

per child: a) NUT = $23 b) MC villages = $9 c) NUT + MC = $21 d) Control villages = $8 Cost per death averted: a) NUT = $76 b) MC = $135 c) NUT + MC = $21 |

| 25 | King et al. 53 | 1978 | Haiti | Cost analysis | Program | - | Centers for prevention

and therapy for SAM |

Total annual cost

for the center = $4155 Cost per child is $10 |

|||

| 26 | Kittisakmontri

et al. 54 |

2016 | Thailand | Prospective cohort | Cost analysis | Hospital | Bottom-up

approach |

Hospitalization | 53 | 1 to 59

Mean age (26.8 ± 1.8) |

Total hospital

expenditures for: a) Stunted children = €524.05 b) Wasted = €576.08 c) Stunted and wasted = €1175.58 |

| 27 | Lagrone et al. 55 | 2010 | Malawi | Prospective,

observational |

Cost analysis | Ready-to-use

supplemental food |

2417 | 6 to 59 | Cost per child

treated was $5.39 |

||

| 28 | Lagrone et al. 56 | 2011 | Malawi | Prospective,

randomized, investigator blinded, controlled non- inferiority trial |

Cost analysis | Provider | Bottom-up | a) Fortified blended

flour (CSB++) b) Locally produced soy RUSF c) Imported soy/whey RUSF |

a) 948

b) 964 c) 978 |

6 to 59 | The cost of the

three foods was as follows: US$0.03 for CSB++, US$0.04 for soy RUSF, and US$0.07 for soy/ whey RUSF per 100 kcal (418 kJ) |

| 29 | Loevinsohn et al. 57 | 1997 | Philippines | Prospective study | Cost

effectiveness |

Government | Bottom-up

approach |

Vitamin A

supplementation |

a) Mild,

moderate and severe malnutrition = 2,358,824 b) Moderate and severe = 398,450 |

6 to 59 | Total costs:

a) Mild, moderate and severe malnutrition = $1034510 b) Moderate and severe malnutrition = $888659 Costs per death averted: a) Mild, moderate and severe malnutrition = $144.1 b) Moderate and severe = $257.2 |

| 30 | Marino et al. 58 | 2013 | South Africa | Retrospective

cohort |

Cost analysis | Hospital | Bottom-up

approach |

Energy dense ready-to-

use (RTU) infant feed vs fortified infant formula (PIF) |

2652 | <12

months |

a) Energy dense

RTU = €12.51 per day b) PIF + sunflower= €16.92 c) PIF + MCT oil = €19.61 |

| 31 | Matilsky et al. 59 | 2009 | Malawi | Randomized

clinical effectiveness trial |

Cost analysis | Provider | Bottom-up

approach |

Locally manufactured

milk/peanut fortified spreads (FS) Soy/peanut FS Corn/soy blended flour (CSB) |

6–60 | The cost of the

foods: Milk/peanut FS = US$0.16/1000 kJ Soy/peanut FS = US$ 0.08/1000 kJ CSB = US$0.04/1000 kJ |

|

| 32 | Medoua et al. 60 | 2016 | Cameroon | Comparative

efficacy trial |

Cost analysis | Provider | Bottom-up

approach |

Ready-to-use

supplemental food (RUSF) Corn–soya blend (CSB+) |

81 | 25–59 | Cost to treat a

child with: CSB+ = €3.48 RUSF = € 3.52 |

| 33 | Menon et al. 61 | 2016 | India | Model study | Cost analysis | Program | Program

experience approach |

Community based

management of SAM |

Estimated cost

per child was $200 |

||

| 34 | Melville et al. 62 | 1995 | Jamaica | Retrospective

cohort |

Cost analysis | Program | Bottom-up

approach |

Growth monitoring

Community volunteer program |

88 | < 36 | Total cost of the

program in the two years was $2740. The total cost per child was $31.1 |

| 35 | Moench-

Pfanner 30 |

2016 | Cambodia | Model study

of economic losses due to malnutrition |

Cost analysis | Government | Modelling

approach |

- | - | - | Economic losses

due to: Wasting = $7.4 Underweight = $12.3 Stunting = $120.3 |

| 36 | Ndekha et al. 63 | 2005 | Malawi | Randomized

controlled trial |

Cost analysis | Provider | Bottom-up

approach |

RUTF | 93 | 12 to 60 | Cost per child

$33 |

| 37 | Nkonki et al. 64 | 2017 | South Africa | Model study | Cost analysis | Provider

perspective |

Ingredients

approach |

Therapeutic feed and

community-based treatment of MAM |

- | - | Total costs:

Therapeutic feeding = $12549660 Community based management of MAM = $28213620 |

| 38 | Puett et al. 65 | 2013 | Bangladesh | Cross-sectional | Cost-

effectiveness |

Societal | Activity-based

costing |

Community-based

management of SAM delivered by community health workers (CMAM) vs inpatient treatment |

1357 | 13 to 16 | Cost per death

averted: a) CMAM = $869 b) Inpatient = $45688 Cost per DALY averted: a) CMAM = $26 b) Inpatient = $1344 Cost per child treated: a) CMAM = $165 b) Inpatient = $1344 Cost per child recovered: a) CMAM = $180 b) Inpatient = $9149 |

| 39 | Purwestri et al. 66 | 2012 | Indonesia | Prospective cohort | Cost analysis | Institutional/

program |

Bottom-up

approach |

Community-based

daily program (semi urban area) vs weekly program (rural area) |

204 | Daily

program (30.9 ± 12.9) Weekly program (31.6 ± 13.9) |

Institutional costs

(per child): a) Daily program = $234.3 ± 156.9 b) Weekly program = $257.1± 152.3 Total social costs (volunteer & caregivers time) per child: a) Daily = $141.9 ± 103.7) b) Weekly = $74.7 ± 54.8) |

| 40 | Qureshy et al. 26 | 2013 | Indonesia | Modelling study | Cost-benefit

analysis |

Program | Modelling

approach |

Foetal and maternal

growth monitoring, micronutrient supplements & immunizations (Pyosandu) and block grants ( Generasi) |

306518 | Total program

cost is $114.8 million Cost per child = $ 18 Cost benefit ratio is 2.8 |

|

| 41 | Rogers et al. 67 | 2018 | Mali | Clinical cohort trial | Cost and cost

effectiveness |

Societal | Activity-based

costing |

a) CHW: screening

in the community + referral to outpatient clinics b) CHW: outpatient clinics only |

a) 617

b) 212 |

6 to 59 | Cost per child:

a) 244 b) 442 |

| 42 | Rogers et al. 68 | 2019 | Pakistan | Clinical cohort trial | Cost and cost

effectiveness |

Societal | Activity-based

costing |

a) LHW: screening

in the community + referral to outpatient clinics b) LHW: outpatient clinics only |

a) 425

b) 393 |

6 to 59 | Cost per child:

a) 291 b) 301 |

| 43 | Rogers et al. 69 | 2019 | Pakistan | Randomized

controlled trial |

Cost and cost

effectiveness |

Institutional | NR | a) SAM treatment only

b) SAM treatment + Aquatabs c) SAM treatment + flocculent disinfection d) SAM treatment + ceramic filters |

901 | 6 to 59 | Cost per child

treated: a) 256 b) 239 c) 290 d) 369 Cost per child recovered: a) 482 b) 318 c) 416 d) 522 ICER (Aquatabs vs SAM treatment only) = $24 |

| 44 | Sandige et al. 70 | 2004 | Malawi | Randomized

controlled trial |

Cost analysis | Provider | Bottom-up

approach |

a) RUTF (local)

b) RUTF (imported) |

260 | 12 to 60 | Cost per child:

a) $22 b) $55 |

| 45 | Sayyad-Neerkorn

et al. 71 |

2015 | Niger | Prospective cohort | Cost analysis | Provider | Bottom-up

approach |

a) SC+

b) LNS |

a) 845

b) 1122 |

a) 17.4

b) 15.2 |

Cost per child:

a) 154.8 b) 121.05 |

| 46 | Shekar et al. 28 | 2016 | DRC, Mali,

Nigeria and Togo |

Modelling study | Cost

effectiveness |

Government | Program

experience approach |

Cost of scaling up 10

Lancet interventions (Bhutta 2013) |

Cost per DALY

averted: DRC = $143 Mali = $ 178 Nigeria = $ 141 Togo = $127 Cost per life year saved: DRC = $226 Mali = $ 344 Nigeria = $ 292 Togo = $238 |

||

| 47 | Tekeste et al. 72 | 2012 | Ethiopia | Retrospective

cohort |

Cost-

effectiveness |

Societal

perspective |

Bottom-up

approach |

Community-based

therapeutic care (CTC) vs therapeutic feeding (TFC) |

306 | CTC

(41.42 ± 20.58) TFC (59.4 ± 47.8) |

The total cost per

child treated: a) CTC = $134.88 b) TFC = $284.56 Total institutional costs per child: a) TFC = $262.62 b) CTC = $128.58 Caretakers cost per child: a) CTC = $6.29 b) TFC = $ 21.93 |

| 48 | Waters et al. 73 | 2006 | Peru | Prospective | Cost

effectiveness |

a) Provider

b) Household |

Activity-based

costing |

Nutrition education

programme |

187 | 0 to 18 | Cost per child:

a) $15.37 b) $0.46 Cost per case averted = $ 138.50 Cost per death averted = $1952 |

| 49 | Whittaker et al. 74 | 1985 | South Africa | Retrospective

cohort |

Cost analysis | Program | Modelling

approach |

Philani Nutrition day

center for rehabilitation of undernourished children (SAM and MAM) |

42 | 0 to 84 | Total costs =

R29759 Overall cost per child/attendance= R2.42 Cost per child a) SAM = R194 b) MAM = R73 |

| 50 | Wilford et al. 75 | 2011 | Malawi | Decision analytical

modelling |

Cost-

effectiveness |

Program &

government |

Modelling

approach |

CMAM integrated into

existing health services (CMAM) vs non-CMAM |

2780 | <60 | Cost per DALY

averted (CMAM) = US$42 Cost per life saved (CMAM) = US$1365 Total cost for providing: a) CMAM cost was $470,703 b) Non-CMAM cost was $23,394 |

SAM, severe acute malnutrition; NR, not reported; RUSF, ready-to-use supplementary food; CSB, Corn-Soy Blend; LMF, locally milled flours; CTC, community-based therapeutic care; DALY, disability-adjusted life year; PEM, protein energy malnutrition; NCP, nutritional care plan; MAM, moderate acute malnutrition; RUTF, ready-to-use therapeutic food; A-HPF, augmented, energy dense, home prepared food; DRC, Democratic Republic of the Congo; CMAM, community-based management of acute malnutrition; NUT, nutritional care; MC, medical care; PIF, powdered infant formula; SC, Super Cereal; LNS, lipid-based nutritional supplement; FS, fortified spread; MCT, medium-chain triglyceride; CHW, Community Health Worker; LHW, Lady Health Worker; TFC, therapeutic center; ICER, incremental cost-effectiveness ratio.

Figure 1. Flowchart showing the search, selection and inclusion of studies.

Year of publication

The included articles were published between 1972 and 2019, with majority (66%) published from 2009. Of those published from 2009, 17 assessed the cost of supplementary feeds administered to children with MAM, while twelve studies assessed costs of implementation of CMAM programs in different regions, four of which compared CMAM to facility-based care of children with SAM. Studies published between 1972 and 1997 mainly focused on nutritional rehabilitation programs involving administration of supplementary feeds or special diets to children, parental counselling and monitoring. Two of these studies assessed the cost of inpatient treatment for children with malnutrition.

Studies by region and continent

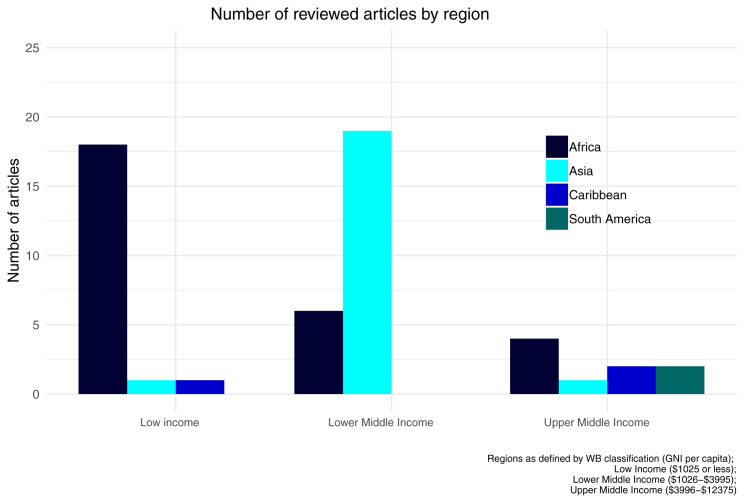

Overall, most studies were carried out in Africa (56%) and Asia (34%), while others were done in the Caribbean and South America ( Figure 2). With reference to the World Bank classification of countries 24, more than 75% of these studies were conducted in either low-income or lower middle economies (with Gross National Income per capita of less than $3996).

Figure 2. Number of articles by World Bank classification regions WB, World Bank; GNI, gross national income.

Perspective of the analysis

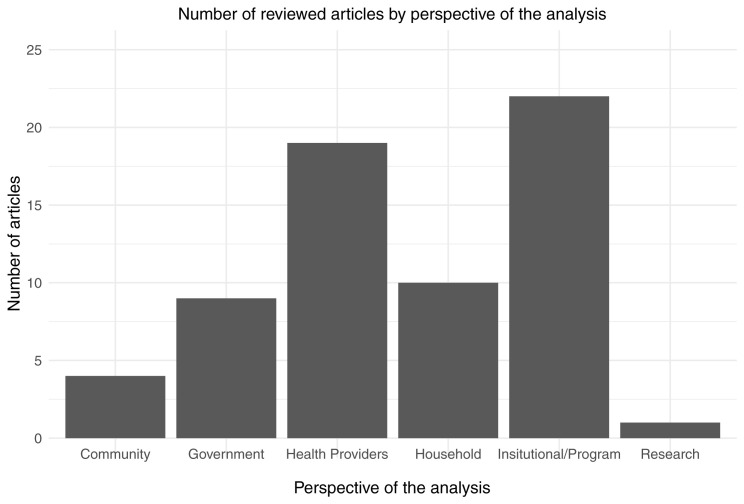

Perspective in economic evaluation describes the viewpoint adopted when deciding the scope of costs and benefits to be included 21. Studies in this review mostly adopted an institutional/program perspective (44%) or health provider perspective (38%) ( Figure 3). Nine studies reported costs from the government’s perspective, three of which modelled the costs of scaling up nutrition interventions to reduce stunting. Only ten studies included in this review assessed costs incurred during treatment of child undernutrition from more than one perspective ( Table 2).

Figure 3. Number of articles by perspective of the analysis.

Type of economic evaluation and analytical approach

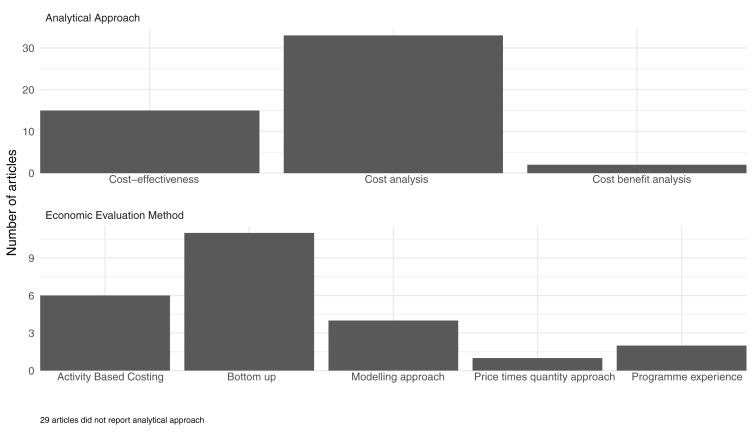

Studies included were cost analyses (n=33), cost-effectiveness studies (n=15) and cost benefit analyses (n=2). The cost analysis approach only measures costs without considering outcomes. The cost-effectiveness technique measures relative cost against effectiveness of the intervention, while cost-benefit analysis compares cost of intervention against benefits gained from the intervention. Eight of the cost-effectiveness analysis studies assessed the standard CMAM program compared to alternative treatment. The two cost-benefit analysis studies reported cost benefit ratios of interventions aimed at reducing stunting 25, 26.

The majority (22%) of these studies adopted the bottom-up approach to costing, while program experience and price times quantity approaches (6%) were the least used ( Figure 4). The bottom-up approach estimates total costs through the multiplication of unit costs by the quantities used 27. The programme experience approach utilizes cost data for each intervention from actual programs in operation while considering the delivery channels 28. Activity-based costing involves assignment of costs to departments or activities then to various services 21.

Figure 4. Number of articles by type of economic evaluation and analytical approach.

Economic evaluation by perspective

Government perspective. We defined this as costs incurred by the government for treatment of child undernutrition. We identified nine studies reporting these costs. Five of these studies modelled the economic consequences of undernutrition and the cost of scaling up stunting interventions in African and Asian countries. Among these, two studies explored the economic losses in Cambodia associated with 14 nutrition indicators of malnutrition including stunting, underweight and wasting 29, 30. The studies used a consequence model to estimate the value of economic losses due to increased child mortality, depressed future productivity, and excess healthcare expenditures attributable to malnutrition. On average, losses due to malnutrition accounted for more than 260 million USD annually; equivalent to approximately 1.5% of the Cambodian GDP. Notably, average annual losses due to stunting was higher (US$124 million) compared to underweight (US$17 million) and wasting (US$13 million). This was due to the high prevalence of stunted children in the country.

A study published in 2013 assessed the cost benefit analysis of interventions aimed at reducing stunting for 17 high burden countries 25. The benefit cost ratio for all the countries was greater than one and ranged between 3.5 (Democratic Republic of the Congo, DRC) to 48 (Indonesia), meaning that an equivalent of $US3.5 and $US48 in economic returns could be generated in DRC and Indonesia, respectively, for every dollar invested in programmes aimed at reducing stunting.

Cost-effectiveness analyses of nutrition-specific interventions was conducted using data from four African countries 28. The cost per DALY averted ranged between (US$127–US$178), which was below the established willingness to pay threshold in these countries, suggesting that scaling up these interventions was cost effective.

One study explored costs borne by the government during the implementation and integration of a CMAM program into existing health services 75. Findings from this study showed that the government covered only 10% of the total costs. These included administrative costs, inpatient costs for children who were referred to inpatient treatment and labor costs by the clinic staff and supervisors. The main driver of these costs were labor costs (US$12 per child).

Community volunteers perspective. We defined this as the direct and indirect costs incurred by community volunteers during the implementation of CMAM. The review identified five studies assessing these costs 31, 65– 68. Two studies conducted in Mali and Pakistan compared the cost effectiveness of treatment of uncomplicated SAM by community health workers (CHWs) to outpatient facility based programs 67, 68. The study in Mali reported that delivery of treatment by CHWs ($259 per child recovered) was more cost-effective compared to the outpatient facility care ($501 per child). The study in Pakistan, however, reported considerable uncertainity as to which method was more cost-effective as results of the sensitivity analyses showed small differences in costs and recovery rates between the two arms ( Table 3). In addition, a paper done in Bangladesh assessing the cost-effectiveness of CMAM delivered by CHWs found out that this was more cost-effective (US$26 per DALY averted) than inpatient treatment (US$1344 per DALY averted). Each CHWs was paid a monthly stipend of US$11.80 during this study 65

Table 3. Costs and cost-effectiveness of community-based management of severe acute malnutrition (CMAM integrated programs).

| Author;

year |

Country | Sample

size (n) |

Intervention | Outcome | Cost per child

(USD) |

Cost per

DALY averted/ gained (USD) |

Cost

per life year saved (USD) |

Cost per

death averted (USD) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Abdul-Latif

2014 31 |

Ghana | 40 | CMAM | NR | 805 | NR | NR | NR |

| 2. | Bachmann

2009 35 |

Zambia | 2523 | a) CMAM

b) Hypothetical no treatment |

Mortality:

a) 9.2% b) 20.8% |

203 | 53 (DALY

gained) |

1760 | NR |

| 3. | Goudet

et al. 2018 47 |

India | 12362 | a) Aahar acute

malnutrition program b) Standard of care |

Cured | 27 | 23 | 12360 | |

| 4. | Isanaka

et al. 2016 50 |

Niger | 16084 | CMAM | NR | 196 | NR | NR | NR |

| 5. | Isanaka

et al. 2019 51 |

Mali | 1264 | Treatment of MAM:

a) RUTF b) CSB++ c) Misola d) Locally milled flour Treatment of SAM only |

Reduced risk

of death: a) 15.4% b) 12.7% c) 11.9% d) 10.3% SAM: NR |

a) 17.25

b) 8.10 c) 7.85 d) 8.50 SAM: 165 |

a) 347

b) 446 c) 490 d) 630 SAM: 142 |

NR | a) 9821

b) 12435 c) 13146 d) 17486 SAM: 3974 |

| 6. | Puett

et al.

2013 65 |

Bangladesh | 1357 | a) CMAM

b) Inpatient treatment (“standard of care”) |

Recovery

rates: a) 91.9% b) 1.4% |

a) 165

b) 1344 |

a) 26

b) 1344 |

a) 869

b) 45688 |

|

| 7. | Purwestry

et al. 2012 66 |

Indonesia | a) 103

b) 101 |

a) CMAM (daily

supervision) b) CMAM (weekly supervision) |

Weight gain:

a) 3.7g/kg/day b) 2.2g/kg/day |

a) 376

b) 331 |

NR | NR | NR |

| 8. | Rogers

et al. 2018 67 |

Mali | a) 617

b) 212 |

a) CHW: screening/

treatment in community + referral to outpatient clinics b) CHW: outpatient clinics only |

Recovery

rates: a) 94.17% b) 88.21% |

Cost per child

treated a) 244 b) 442 Cost per child recovered: a) 259 b) 501 |

NR | NR | NR |

| 9. | Rogers

et al. 2019 68 |

Pakistan | a) 425

b) 393 |

a) LHW: screening/

treatment in community + referral to outpatient clinics b) LHW: outpatient clinics only |

Recovery

rates: a) 76% b) 82.3% |

Cost per child

treated: a) 291 b) 301 Cost per child recovered: a) 382 b) 383 ICER (control): 146 |

NR | NR | NR |

| 10 | Rogers

et al. 2019 69 |

Pakistan | 901 | a) SAM treatment only

b) SAM treatment + Aquatabs c) SAM treatment + flocculent disinfection d) SAM treatment + ceramic filters |

Recovery

rates a) 53.1% b) 75.2% c) 69.7% d) 70.7% |

Cost per child

treated: a) 256 b) 239 c) 290 d) 369 Cost per child recovered: a) 482 b) 318 c) 416 d) 522 ICER (Aquatabs) = $24 |

|||

| 11 | Tekeste

et al. 2012 72 |

Ethiopia | 306 | a) CMAM

b) Facility-based therapeutic care |

Cure rates

a) 94.3 % b) 95.36% |

a) 135

b) 285 |

NR | NR | NR |

| 12 | Wilford

et al.

2011 75 |

Malawi | 2780 | a) CMAM integrated into

existing health services b) Existing health services (inpatient care) |

Mortality

a) 11.9% b)17.1% |

a) 165

b) 16.7 |

a) 42 | a) 1365 | NR |

DALY, disability-adjusted life year; USD, United States Dollars; NR: not reported; CMAM, community-based management of malnutrition; LHW, Lady Health Worker; CHW, Community Health Worker; RUTF, ready-to-use therapeutic feeding; SAM, severe acute malnutrition; CSB, corn soy blend; ICER, incremental cost-effectiveness ratio.

The other two studies conducted in Ghana 31 and Indonesia 66 reported indirect and transport costs incurred by community volunteers while implementing the CMAM program. The average costs were US$61 and $0.2 per child for indirect costs and transport costs, respectively.

Household perspective. We defined this as the direct and indirect costs incurred by families of children with undernutrition. Ten studies conducted between 1997 and 2019 reported costs from the household’s perspective. Nine studies considered interventions for children under the age of five years with SAM. The average cost per child to households ranged widely from US$0.5 in Peru 73 to US$82 in Bangladesh 65. The least costly study in Peru (2006) involved a nutritional education programme in which the households only incurred transportation and consultation costs; all other costs were incurred by the health facilities delivering the program. The Bangladesh study (2016) compared costs incurred during CMAM and inpatient treatment, with the latter being more costly to the households (US$82) per child treated.

Overall, the least costly treatments to households were those involving outpatient management, day care or CMAM programs, costing US$0.5–US$69 per child compared to traditional inpatient management (US$3.1–US$538). Among the direct medical costs, supplementary feeds was the highest cost driver ($14 per child) to the households, as reported by a study conducted in Ghana during the implementation of a CMAM program 31. Productivity loss was also higher in inpatient care than outpatient care due to the longer periods spent in health care facilities with their children during treatment ( Table 4). Overall, direct non-medical costs such as food (US$32) and indirect costs (US$21) were the main cost drivers to households.

Table 4. Cost per child per treatment in USD incurred by households.

| Outpatient (CMAM, day

care, domiciliary care) |

Inpatient management | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cost categories | Mean

(SD) |

Median

[IQR] |

N * | Mean

(SD) |

Median

[IQR] |

N * |

| Direct medical costs | ||||||

| Medication costs | - | - | 7.6 | 7.6 | 1 | |

| Supplementary feeding | 14.4 | 14.4 | 1 | - | - | - |

| Administrative costs | 0.4 | 0.4 | 1 | - | - | - |

| Direct non-medical costs | ||||||

| Transport costs | 1.9 (1.6) | 2.0 [0.7,2.4] | 4 | 2.9 (3.8) | 0.9 [0.7-4.1] | 3 |

| Food (non-medical) | 6.6 (7.5) | 4.0 [3,6] | 4 | 32.1 | 32.1 | 1 |

| Indirect costs (loss of income) | 18.9 (24.5) | 10.2 [3,22] | 6 | 16.6 (12.4) | 21.0 [11-23] | 3 |

USD, United States Dollars; CMAM, community management of acute malnutrition; SD, standard deviation; IQR, interquartile range; N*, number of articles included.

Health providers’ perspective. We defined this as the direct medical and direct non-medical costs incurred by institutions offering health services. Of the included studies, 19 reported costs from the health provider’s perspective. These studies assessed costs incurred due to provision of supplementary feeds for children with MAM, cost of outpatient treatment (CMAM, daycare management and domiciliary management) and costs of inpatient care. Costs borne by the providers included both direct medical and direct non-medical costs ( Table 5). The average cost per child per treatment ranged widely between the studies (US$4-US$811.31). The main driver of costs for the health providers were personnel costs (personnel wages and salaries).

Table 5. Cost per child per treatment in USD incurred by health providers.

| Cost categories | Mean (SD) | Percentage

of total mean costs |

Median [IQR] | N * |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct medical costs | ||||

| Personnel costs | 117 (226) | 50 | 35 [8-99] | 6 |

| Medication costs | 42 (65) | 18 | 20 [9-41] | 6 |

| Capital costs | 18 (13) | 7 | 19 [8-28] | 3 |

| Administrative costs | 18 (25) | 7 | 2 [1-34] | 3 |

| Supplementary feeding | 29 (36) | 12 | 16 [8-34] | 14 |

| Direct non-medical costs | ||||

| Transport costs | 9 (16) | 3 | 0.6 [0.3-14] | 3 |

USD, United States Dollars; SD, standard deviation; IQR, interquartile range; N*, number of articles included.

Program perspective. We defined this as the direct medical and direct non-medical costs incurred by non-health care organisations and institutions implementing programs aimed at managing child undernutrition. In total, 22 articles reported these costs. These programs included community-based management of malnutrition and nutrition rehabilitation centers set up for children with malnutrition. Costs incurred by these organizations included direct medical and direct non-medical costs ( Table 6). The costs incurred ranged from US$0.15 to US$449.56. The main drivers were personnel costs (personnel wages and salaries) and administrative costs (training costs, monitoring and mobilization costs).

Table 6. Costs per child per treatment in USD incurred by institutions/programs.

| Cost categories | Mean (SD) | Percentage

of total mean costs |

Median [IQR] | N * |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct medical costs | ||||

| Personnel costs | 120 (139) | 35 | 107 [23–160] | 12 |

| Medication costs | 33 (65) | 9 | 4 [2–20] | 5 |

| Capital costs | 28 (40) | 8 | 15 [4–18] | 9 |

| Administrative costs | 79 (138) | 23 | 20 [12–35] | 5 |

| Supplementary feeding | 45 (50) | 13 | 42 [5–64] | 15 |

| Direct non-medical costs | ||||

| Transport costs | 31 (44) | 9 | 24 [2–29] | 4 |

| Food (non-medical) | 6 (4) | 1 | 5 [2–10] | 2 |

USD, United States Dollars; SD, standard deviation; IQR, interquartile range; N*, number of articles included.

CMAM

The costs and cost-effectiveness of CMAM integrated programs for treatment of children under five with SAM were assessed in 12 studies published after 2009; seven of these were implemented in African countries and five in Asian countries. These costs included; personnel, supplementary feeding, transport and opportunity costs to households and community volunteers. The costs ranged from $135 in Ethiopia to $850 per child in Ghana. The main drivers of costs incurred were personnel costs, which were as high as $200 per child in Indonesia, and supplementary feeds, which ranged from $13 to $87 per child, the least costly feeds being made from locally available materials.

Additionally, four studies assessed the cost-effectiveness of the CMAM program 35, 65, 72, 75. Cost per disability adjusted life year (DALY) for the CMAM program ranged between US$26 and US$53, which was much lower compared to facility-based management (US$1344 per DALY averted) ( Table 3). Further, a study carried out in Malawi reveals that integration of a community-based program into existing health services is cost-effective 75. The study used a decision tree model to compare costs and effects of existing health services with CMAM and existing health services without CMAM. In this study, there were 342 less deaths in the CMAM implemented scenario compared to the non-implemented scenario. The resulting cost per DALY averted for adding CMAM in to existing health services was US$42, which was highly cost-effective.

Overall, cost per child for the CMAM programs implemented by community volunteers was $216 while CMAM implemented in traditional facility-based programs was $300 per child ( Table 3).

Productivity loss and coping strategies

In addition to direct health care costs such as drug costs and transport costs incurred by households due to malnutrition, families spend a lot of time away from their normal duties to seek treatment. Findings from one retrospective study done in rural Ghana to assess the costs of CMAM revealed that high costs were incurred by families to ensure normal running of household’s activities while seeking treatment 31. More than a third of the total household costs constituted the cost of employing people to take care of what the caregivers would have been doing if they were not seeking care. This was equivalent to US$16 per child treated in the program.

In addition, the huge financial burden to households leads to different coping mechanisms being adopted to mitigate necessary payment for healthcare for their children. A study done in Bangladesh reported that some of the households received food as gifts from their relatives and neighbours in order to meet the prescribed dietary requirements for their children after treatment 34.

Quality assessment of the studies

Among the 17 items in the GHCC guidelines ( Table 7), only nine items were either partially or fully met by more than 60% of the included studies. For instance, of the 50 studies, less than half stated the costing methods used and perspective of the analysis, which are important components in economic evaluations according to the guidelines. Further, only 18 studies conducted sensitivity analysis to characterize any uncertainity in the reported cost estimates.

Table 7. Quality assessment of studies as highlighted in Global Health Cost Consortium (GHCC).

| Number of articles (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Principle | 1=Satisfied | 0=Not satisfied | Not

applicable* |

|

| Study design and scope | ||||

| 1 | Purpose, population & intervention | 50 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| 2 | Perspective | 22 (44) | 28 (56) | 0 (0) |

| 3 | Type of cost | 29 (58) | 21 (42) | 0 (0) |

| 4 | Unit costs | 46 (92) | 4 (8) | 0 (0) |

| 5 | Time (Data year/Time horizon) | 50 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Service use and resource use measurement | ||||

| 6 | Scope of inputs | 41 (82) | 9 (18) | 0 (0) |

| 7 | Costing method (costing approach) | 21 (42) | 29 (58) | 0 (0) |

| 8 | Sampling strategy | 50 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| 9 | Selection of data source | 35 (70) | 15 (30) | 0 (0) |

| 10 | Timing of data selection (prospective/retrospective) | 41 (82) | 9 (18) | 0 (0) |

| Valuation and pricing | ||||

| 11 | Sources of price data | 34 (68) | 16 (32) | 0 (0) |

| 12 | Amortization of capital costs | 11 (11) | 21 (30) | 17(59) |

| 13 | Discounting, inflation (where relevant) | 10 (20) | 23 (46) | 17 (34) |

| 14 | Use of shadow prices | 9 (18) | 6(12) | 35 (70) |

| Analyzing and presenting results | ||||

| 15 | Heterogeneity | 22 (44) | 28 (56) | 0 (0) |

| 16 | Sensitivity analysis | 18 (36) | 32 (64) | 0 (0) |

Discussion

This review gives a breakdown of direct and indirect costs borne by households, health providers, the community, institutions/programs and the government. The studies varied in the interventions studied and costing methods used, with studies reporting treatment costs between US$0.44 and US$1344 per child. The majority of the included studies were done in Africa and Asia. This could be explained by the high burden of child undernutrition in these regions 7, leading to numerous efforts to manage its cost and health implications. In line with the WHO recommendations on management of child undernutrition 76, included studies assessed interventions such as supplementary feeding for children with moderate acute malnutrition, nutritional rehabilitation and community management of severe acute malnutrition. Most included studies adopted the institutional/program (44%) and health provider (38%) perspectives, while only four adopted the community volunteers’ perspective.

Integration of outpatient and inpatient care for children with undernutrition was recommended after endorsement of CMAM in 2007. However, most of the studies reviewed compared cost outcomes of outpatient and inpatient care separately. This review identified only one study conducted in Malawi 75 assesing the costs of integrating CMAM into existing health services, concluding that it is cost-effective (US$42 per DALY averted). For generalizability and strengthening of this evidence to inform policy, there is need to conduct similar studies from a range of settings to assess cost-effectiveness of integrating CMAM into primary healthcare.

According to this review, substantial costs for health providers and programs were due to personnel, medication and therapeutic feeds. The costs of therapeutic feeds were high mainly because they were imported. This suggests that production of feeds using local ingredients could potentially reduce costs. Studies reporting from these perspectives mainly assessed the costs of implementing the CMAM program, whose key components are administration of supplementary feeds and involvement of CHWs for community mobilization 11 to ensure high coverage and timely detection of children with malnutrition.

Despite a major role played by CHWs during the implementation of CMAM, only two studies included in this review assessed the costs they incurred. This included transport costs ($0.2 per child) and indirect costs, which were as high as US$60 per child 31, 66. In these studies, compensation to the volunteers was done by the funding organisations only in form of food and household goods. These findings imply that to ensure effective and efficient implementation of the CMAM program in future, there is a need to consider more structured and better compensation methods for CHWs. This is in support of findings from a study conducted in Mali assessing the cost-effectiveness of treatment of uncomplicated SAM using CHWs and outpatient facilities. In this study, treatment using CHWs was cost-effective 67.

In addition to the out of pockets costs incurred by families with children affected by malnutrition, this review reveals that indirect costs were the main driver of costs, especially for those admitted to hospital. This could be explained by the longer duration of time spent away from normal duties to take care of children, resulting in lost income. This highlights the need for adoption of the CMAM program in more countries, which would contribute to early identification and treatment of malnutrition cases to avoid worsening of illness and prolonged inpatient hospital stays. In addition, medication costs incurred by families were also high, especially for children with SAM. This was mainly due to co-infections associated with acute malnutrition 77. Supplementary feeds and transport costs were also significant costs incurred by families due to undernutrition. Although feeds were mostly provided by organizations, the cost of preparing them fell on the caregivers. For instance, a third of total household costs in a study conducted in Ghana constituted the cost of preparing these feeds 31.

These costs highlight the huge financial implications to households attributable to undernutrition. For poor households, especially in low-income settings, this could be catastrophic as they are less equipped to endure the adverse impact on their income 78. This may result to borrowing from friends and family members, selling of assets and reliance on well-wishers as coping strategies towards these costs. Interviews conducted in households in rural Ghana indicated that families of children with malnutrition resulted in; cheaper treatment options for their sick children other than professional healthcare, reliance on other family members to pay medical costs and reliance on non-profit organizations for both food and medication. This was mainly due to lack of reliable sources of income for the parents 79. This highlights the need to identify affordable interventions for prevention and treatment of malnutrition in children, especially in these settings.

Additional findings from this review support previous findings that governments incur huge costs due to malnutrition 80. However, a study included in this review shows that investing in a set of nutritional interventions to reduce stunting is beneficial 25. The study showed that investing at least one dollar to reduce stunting could generate an average of US$18 worth of benefits in LMICs. This is consistent with findings from a previous review providing evidence of a reduction of 15% mortality due to stunting in children under five years if interventions were accessible at 90% coverage.

Limitations

This review had certain limitations. First, heterogeneity in the costing methods, interventions assessed and reporting of costs precluded a comprehensive comparison of costs and therefore, meta-analysis was inappropriate. Secondly, A limitation inherent in the available data was that there was a wide range of cost outcomes and unit measurements for some of the outcomes, cost categories for similar cost centres varied a lot among the studies. Thus, meta-analysis was inappropriate.

Thirdly, from our quality assessment of the included studies, less than half of the items on the GHCC guidelines were either partially or fully met by the included studies. For instance, most articles did not mention the perspective, costing approach used and did not conduct sensitivity analysis to characterise uncertainties in the reported costs outcomes Lastly, full texts that were neither in English nor French were not included in the review. Therefore, some relevant evidence might have been missed.

Conclusions

Integration of outpatient and inpatient care for children with undernutrition through the CMAM program has been recommended as it is more effective and cost-effective compared to traditional programs characterised by prolonged inpatient duration. However, this review reveals that many countries have not adopted the integrated CMAM program, hence studies still report cost outcomes of inpatient and outpatient care separately. This highlights the need for more countries to adopt the CMAM program to reduce cost implications. Further, cost studies need to shift towards evaluating integrated programs to provide insight into different and more cost-effective ways of delivering the CMAM program through primary healthcare.

Additionally, current cost estimates on integrated programs include substantial support from international organisations which may represent higher costs. Therefore, there is need for more studies to generate cost estimates of integrated programs from government delivered programs to represent the actual situation.

This review also reveals the paucity of data on the economic burden of undernutrition to households and communities. More studies are needed to assess this burden in order to assist in planning, identifying cost-effective solutions and addressing issues of cost that may limit delivery, uptake and effectiveness of interventions.

We also recommend that for easy and comprehensive secondary analysis all items as listed in the GHCC guidelines including explicitly stating the perspective of the analysis, costing methods used, conducting sensitivity analysis should be adhered to by authors. Further, for comprehensive comparison of the cost and cost-effectiveness of interventions or treatments used in studies, this review recommends a standardization of methods used and cost categories reported in economic evaluations as per the GHCC guidelines.

Data availability

Underlying data

Figshare: Cost and cost effectiveness analysis of treatment for child undernutrition in low and middle income countries: A systematic review-Dataset https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.11985873.v2 81

This project contains the following underlying data:

Dataset in CSV format

Data code book in PDF format

Reporting guidelines

Figshare: Cost and Cost effectiveness Analysis of Treatment for Child Undernutrition in Low and Middle Income Countries: A Systematic Review-PRISMA Checklist https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.11961153.v2 82

Data are available under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC-BY 4.0).

Funding Statement

This work was supported through the DELTAS Africa Initiative [DEL-15-003] and core awards to the KEMRI-Wellcome Trust Research Programme [203077]. The DELTAS Africa Initiative is an independent funding scheme of the African Academy of Sciences (AAS)'s Alliance for Accelerating Excellence in Science in Africa (AESA) and supported by the New Partnership for Africa's Development Planning and Coordinating Agency (NEPAD Agency) with funding from the Wellcome Trust [107769] and the UK government. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of AAS, NEPAD Agency, Wellcome Trust or the UK government.

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

[version 2; peer review: 2 approved]

References

- 1. Müller O, Krawinkel M: Malnutrition and health in developing countries. CMAJ. 2005;173(3):279–86. 10.1503/cmaj.050342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Black RE, Allen LH, Bhutta ZA, et al. : Maternal and child undernutrition: global and regional exposures and health consequences. Lancet. 2008;371(9608):243–60. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61690-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Victora CG, Adair L, Fall C, et al. : Maternal and child undernutrition: consequences for adult health and human capital. Lancet. 2008;371(9609):340–57. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61692-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Black RE, Victora CG, Walker SP, et al. : Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet. 2013;382(9890):427–51. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60937-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Burgess A: Undernutrition in Adults and Children: causes, consequences and what we can do. South Sudan Medical Journal. 2008;1(2):18–22. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 6. McLachlan M: Tackling the child malnutrition problem: from what and why to how much and how. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr.LWW, 2006;43 Suppl 3:S38–46. 10.1097/01.mpg.0000255849.22777.69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. UNICEF: Levels and trends in child malnutrition UNICEF–WHO–World Bank Group joint child malnutrition estimates. 2015. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bain LE, Awah PK, Geraldine N, et al. : Malnutrition in Sub-Saharan Africa: burden, causes and prospects. Pan Afr Med J. 2013;15(1):120. 10.11604/pamj.2013.15.120.2535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. World Health Organization, UNICEF: Community-based management of severe acute malnutrition: a joint statement by the World Health Organization, the World Food Programme, the United Nations System Standing Committee on Nutrition and the United Nations Children's Fund.2007. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bahwere P, Binns P, Collins S, et al. : Community-based therapeutic care (CTC). A field manual.2006. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 11. World Health Organization: Updates on the management of severe acute malnutrition in infants and children.Geneva: World Health Organization.2013;55–9. Reference Source [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. African Union Commission, NEPAD, WFP, UN, Economic Commission for Africa: The cost of Hunger in Malawi: Social and Economic Impact of Child Undernutrition in Malawi. Implications on National Development and vision 2020.2015. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hoddinott J: The economics of reducing malnutrition in Sub-Saharan Africa.2016. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 14. Horton S, Steckel RH: Malnutrition: global economic losses attributable to malnutrition 1900–2000 and projections to 2050.How Much Have Global Problems Cost the Earth? A Scorecard from 1900 to 2050. 2013;2050:247–72. 10.1017/CBO9781139225793.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Global Panel: The cost of malnutrition. Why policy action is urgent. London (UK): Global panel on agriculture and food Systems for nutrition.2016. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 16. African Union Comission, NEPAD, WFP, UN, Economic Commission for Africa: The Cost of Hunger in Africa: Social and Economic Impact of Child Undernutrition in Egypt, Ethiopia, Swaziland and Uganda.2014. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 17. Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, et al. : Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4(1):1. 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, University of York, Akers J: Systematic reviews: CRD's guidance for undertaking reviews in health care.Centre for Reviews and Dissemination.2009. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 19. Clarivate Analytics: Endnote X8. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 20. Elmagarmid A, Fedorowicz Z, Hammady H, et al. : Rayyan: a systematic reviews web app for exploring and filtering searches for eligible studies for Cochrane Reviews.Evidence-Informed Public Health: Opportunities and Challenges Abstracts of the 22nd Cochrane Colloquium;2014;2014:21–6. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Global Health Cost Consortium: Reference Case for Estimating the Costs of Global Health Services and Interventions.2017. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 22. R Foundation for Statistical Computing: R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing.R Core Team.2016. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 23. fxtop.com: Currency conversion functions.2001. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 24. World Bank Group: World Bank Country and Lending Groups (Country Classification). 2020(accessed 10/03/2020 2020). Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hoddinott J, Alderman H, Behrman JR, et al. : The economic rationale for investing in stunting reduction. Matern Child Nutr. 2013;9 Suppl 2:69–82. 10.1111/mcn.12080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Qureshy LF, Alderman H, Rokx C, et al. : Positive returns: cost-benefit analysis of a stunting intervention in Indonesia. J Dev Effect. 2013;5(4):447–65. 10.1080/19439342.2013.848223 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jo C: Cost-of-illness studies: concepts, scopes, and methods. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2014;20(4):327–37. 10.3350/cmh.2014.20.4.327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Shekar M, Dayton Eberwein J, Kakietek J: The costs of stunting in South Asia and the benefits of public investments in nutrition. Matern Child Nutr. 2016;12 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):186–95. 10.1111/mcn.12281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bagriansky J, Champa N, Pak K, et al. : The economic consequences of malnutrition in Cambodia, more than 400 million US dollar lost annually. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2014;23(4):524–31. 10.6133/apjcn.2014.23.4.08 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Moench-Pfanner R, Silo S, Laillou A, et al. : The Economic Burden of Malnutrition in Pregnant Women and Children under 5 Years of Age in Cambodia. Nutrients. 2016;8(5): pii: E292. 10.3390/nu8050292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Abdul-Latif AMC, Nonvignon J: Economic cost of community-based management of severe acute malnutrition in a rural district in Ghana. Health. 2014;6(10):886–889. 10.4236/health.2014.610112 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ackatia-Armah RS, McDonald CM, Doumbia S, et al. : Malian children with moderate acute malnutrition who are treated with lipid-based dietary supplements have greater weight gains and recovery rates than those treated with locally produced cereal-legume products: a community-based, cluster-randomized trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;101(3):632–45. 10.3945/ajcn.113.069807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Akram DS, Suleman Y, Hanif HM: Home-based rehabilitation of severely malnourished children using indigenous high-density diet. J Pak Med Assoc. 2016;66(3):251–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ashworth A, Khanum S: Cost-effective treatment for severely malnourished children: what is the best approach? Health Policy Plan. 1997;12(2):115–21. 10.1093/heapol/12.2.115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bachmann MO: Cost effectiveness of community-based therapeutic care for children with severe acute malnutrition in Zambia: decision tree model. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2009;7(1):2. 10.1186/1478-7547-7-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bai KI: Teaching better nutrition by domiciliary management of cases of protein calorie malnutrition in rural areas (a longitudinal study of clinical and economical aspects). J Trop Pediatr Environ Child Health. 1972;18(4):307–12. 10.1093/tropej/18.4.307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bredow MT, Jackson AA: Community based, effective, low cost approach to the treatment of severe malnutrition in rural Jamaica. Arch Dis Child. 1994;71(4):297–303. 10.1136/adc.71.4.297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chapko MK, Prual A, Gamatie Y, et al. : Randomized clinical trial comparing hospital to ambulatory rehabilitation of malnourished children in Niger. J Trop Pediatr. 1994;40(4):225–30. 10.1093/tropej/40.4.225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Cobb GB, Bland RM: Nutritional supplementation: the additional costs of managing children infected with HIV in resource-constrained settings. Trop Med Int Health. 2013;18(1):45–52. 10.1111/tmi.12006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Colombatti R, Coin A, Bestagini P, et al. : A short-term intervention for the treatment of severe malnutrition in a post-conflict country: results of a survey in Guinea Bissau. Public Health Nutr. 2008;11(12):1357–64. 10.1017/S1368980008003297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Daga S, Verma B, Shahane S, et al. : Syndromic management of common illnesses in hospitalized children and neonates: a cost identification study. Indian J Pediatr. 2010;77(12):1383–6. 10.1007/s12098-010-0172-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Fernandez-Concha D, Gilman RH, Gilman JB: A home nutritional rehabilitation programme in a Peruvian peri-urban shanty town ( pueblo joven). Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1991;85(6):809–13. 10.1016/0035-9203(91)90465-b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Fronczak N, Amin S, Laston SL, et al. : An evaluation of community-based nutrition rehabilitation centers.International Centre for Diarrhoeal Diseases Research Bangladesh: Dhaka;1993. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 44. Garg CC, Mazumder S, Taneja S, et al. : Costing of three feeding regimens for home-based management of children with uncomplicated severe acute malnutrition from a randomised trial in India. BMJ Glob Health. 2018;3(2):e000702. 10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ghoneim EH, Hassan MH, Amine EK: An intervention programme for improving the nutritional status of children aged 2-5 years in Alexandria. East Mediterr Health J. 2004;10(6):828–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Jenkins GP: A cost-effectiveness analysis of acute malnutrition treatment using ready to use theraupetic foods.Cambridge Resources International INC: JDI Executive Programs.2013. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 47. Goudet S, Jayaraman A, Chanani S, et al. : Cost effectiveness of a community based prevention and treatment of acute malnutrition programme in Mumbai slums, India. PLoS One. 2018;13(11):e0205688. 10.1371/journal.pone.0205688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Greco L, Balungi J, Amono K, et al. : Effect of a low-cost food on the recovery and death rate of malnourished children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2006;43(4):512–7. 10.1097/01.mpg.0000239740.17606.49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hossain MI, Dodd NS, Ahmed T, et al. : Experience in managing severe malnutrition in a government tertiary treatment facility in Bangladesh. J Health Popul Nutr. 2009;27(1):72–9. 10.3329/jhpn.v27i1.3319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Isanaka S, Menzies NA, Sayyad J, et al. : Cost analysis of the treatment of severe acute malnutrition in West Africa. Matern Child Nutr. 2016;13(4):e12398. 10.1111/mcn.12398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Isanaka S, Barnhart DA, McDonald CM, et al. : Cost-effectiveness of community-based screening and treatment of moderate acute malnutrition in Mali. BMJ Glob Health. 2019;4(2):e001227. 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kielmann AA, Taylor CE, Parker RL: The Narangwal Nutrition Study: a summary review. Am J Clin Nutr. 1978;31(11):2040–57. 10.1093/ajcn/31.11.2040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. King KW, Fougere W, Webb RE, et al. : Preventive and therapeutic benefits in relation to cost: performance over 10 years of Mothercraft Centers in Haiti. Am J Clin Nutr. 1978;31(4):679–90. 10.1093/ajcn/31.4.679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kittisakmontri K, Sukhosa O: The financial burden of malnutrition in hospitalized pediatric patients under five years of age. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2016;15:38–43. 10.1016/j.clnesp.2016.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Lagrone L, Cole S, Schondelmeyer A, et al. : Locally produced ready-to-use supplementary food is an effective treatment of moderate acute malnutrition in an operational setting. Ann Trop Paediatr. 2010;30(2):103–8. 10.1179/146532810X12703901870651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]