Abstract

Background

While financial distress is commonly recognized in cancer patients, it may be more prevalent in younger adults who are not protected by factors such as savings, pensions, Medicare and Social Security benefits. We sought to evaluate disparities in overall and financial distress in cancer patients as a function of age.

Patients and Methods

This was a single center cross-sectional study of patients with solid malignancies requiring cancer therapy. The patient questionnaire included demographics, financial concerns, and measures of distress and financial distress. Data analyses compared patients in three age groups (young: <50, middle-age: 50–64, and elderly: ≥ 65 years of age).

Results

This cohort included 119 patients with cancer (median age, 62; 52% female; 84% white; 100% insured; 36% income ≥$75,000). Significant financial concerns included Rent/Mortgage (p=0.003) and Buying food (p=0.032). Impact of Events Scale results revealed significant distress in 73% young, 64% middle-age, and 44% elderly. The mean Distress Thermometer score for young was 6.1 (standard deviation [SD] =2.9), middle-age 5.4 (SD=2.6) and elderly 4.4 (SD=3.3). Young patients were more likely than elderly to have a higher IES distress score (p=0.016) and distress thermometer score (p=0.048). The mean InCharge score was lowest (indicating greatest financial distress) in the young group and progressed with age: 5.0 (SD=1.9), 5.7 (SD=2.7), and 7.4 (SD=1.9) (p= <0.001). Multivariable analyses revealed the relationship between financial distress and overall distress was strongest in the middle-age group; as the distress thermometer rises by 1 point, the InCharge scores decreases by .52 (P<0.001).

Discussion

This pilot study has important implications for cancer survivors as it describes the pervasive issue of financial distress in cancer patients with insurance, particularly in young and middle-age patients. The cost of cancer treatments is relevant to current patients and survivors along the continuum of cancer treatment.

Conclusions

Distress and financial distress are more common in young and middle-age cancer patients. There are various factors, including employment, insurance, access to paid sick leave, children and education, etc. that affect younger and middle-aged adults, and are less of a potential stressor for elderly individuals.

BACKGROUND

Cancer is an expensive and stressful disease. Since it is often treated as a chronic disease involving long and sometimes recurring courses of treatments, medical bills can quickly accumulate. Cancer patients face greater out-of-pocket (OOP) costs than their healthy peers, and this is true for both nonelderly patients1, 2 and Medicare beneficiaries. The estimates for cancer patients whose OOP costs exceed 20% of their income (indicating a high OOP burden) is 13.4% in the adult nonelderly population1 and 27.6% among Medicare enrollees3, while a representative all-age study found the level to be 11%4. Financial issues may vary based on age. While elderly patients may have lower fixed incomes, the financial protection of Medicare and Social Security may provide less costly securities than nonelderly cancer patients who may be dependent upon employment for health insurance and income. However, traditional Medicare does not have an OOP maximum, and therefore the millions of beneficiaries without supplemental insurance are at increased risk for financial distress as a result of a cancer diagnosis5. The American Cancer Society reports that 53% of the 15.5 million cancer survivors are aged 69 and younger6, which highlights the need to support this population.

The length and intensity of treatment may result in loss of earnings for the patient or their caregiver7. Concerns surrounding employment affect working-age patients, although the importance of job security, career development decisions and retirement will vary with age and dependency of spouses and children8. A recent review described three domains of financial hardship: material conditions, psychological response, and/ or coping behaviors9. Our paper focuses on the psychological response and provides age-related context for potential deficits of material conditions and coping behaviors as a result of financial distress.

Our previous analysis of cancer patients found significant levels of financial distress (29%) and overall distress (65%), and that these constructs were interrelated10. For example, with every one-point increase in financial wellness, the overall distress score fell by .727 points. This association was direct, as well as indirectly mediated by emotional distress which accounted for 24% of the overall effect. In the present study, we extended this work to understand how age may be associated with both financial and overall distress. Since financial concerns and responsibilities change throughout life, we looked at three age groups (young: <50, middle-age: 50–64, and elderly: ≥ 65 years of age).

METHODS

This study included a convenience sample of cancer patients at a National Cancer Institute–designated comprehensive cancer center, recruited through outpatient medical oncology and psychiatry clinics. All eligible cancer patients were aged ≥18 and currently taking, had previously taken, or were consulting with their physician to begin taking anticancer medications.

The study involved one survey which patients completed in clinic. We received a Waiver of Documentation of Informed Consent, and therefore patients were kept anonymous and we did not access medical charts to verify any responses or collect incomplete information. The survey, which was amended slightly after the first 60 patients, included demographics along with the validated measurements outlined below. This study was conducted in two phases of 60 patients each from September 2013 – April 2014, and was approved by the Fox Chase Cancer Center Institutional Review Board.

PATIENT CHARACTERISTICS

Self-reported demographics included age, gender, race and ethnicity, level of education, annual household income, marital status, homeowner status, employment status, and disease and treatment history (Phase 2 only).

AGE GROUPS

Literature review, along with consideration of changing priorities at different stages of life, helped us to develop age groups to frame our analysis. Our “young” group includes ages 18–49, the group most likely to be working, raising a family, and potentially not yet worried about retirement. “Middle-age” includes patients aged 50–64 who are less likely to have dependent children. These patients are more likely to be preparing for retirement, which may impact their willingness to use savings or go into debt to pay for treatments. These first two groups will also be collectively characterized as “working-age” Our final group, “elderly,” are patients aged 65 and older. These patients are least likely to be working and raising children. While they are most likely to be on a fixed income from social security, pensions, and 401(k) payouts, they are also most likely to be provided basic health insurance through Medicare. These age groups are especially relevant as cancer and its treatments, along with physical and emotional side-effects, can make it difficult to maintain work responsibilities, which may result in job loss and subsequent loss of health insurance11.

CONCERNS

A list of common expenses selected by the study team including housing, bills, food, and medical expenses (Phase 2 only) were presented and patients were prompted to indicate any of their financial concerns. Patients could alternatively select “no concerns about expenses.”

DISTRESS MEASUREMENTS

We measured distress in two ways. First, the Impact of Events Scale12, a 15-item measure that evaluates the subjective impact of a traumatic stressor, which in this case was the participant’s cancer diagnosis and treatment. Self-report scores range from 0–75. While there is no unanimous cutoff for psychological distress, relevant literature has utilized a cutoff of 26 to indicate moderate to severe distress13.

Second, the NCCN Distress Thermometer asks patients to identify their overall psychosocial distress in the last week on a thermometer from 0 – 10. Ten indicates the highest level of distress14, and scores of four and greater are considered clinically meaningful15.

FINANCIAL DISTRESS MEASUREMENTS

Financial distress was measured using the InCharge Financial Distress/Financial Well-Being Scale (InCharge) which includes questions such as “How do you feel about your current financial situation?” and “How confident are you that you could find the money to pay for a financial emergency that costs about $1,000?” This 8-question instrument measures a latent construct representing responses to one’s financial state on a continuum ranging from a score of 1.0 (overwhelming financial distress) to 10 (highest level of financial well-being). Raw averaged scores from 1.0 – 4.0 inclusively represent high financial distress16.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Means were calculated for continuous variables and categorical variables were tabulated. We used t-tests to compare means, and chi-square statistic and Fisher’s exact test to compare categorical values. We performed several multiple linear regressions with robust standard errors using the distress and financial distress measures as outcomes of interest and age (<50, 50–64 and ≥65), gender, race, marital status, education, employment, income, and whether their cancer was metastatic as the independent variables. These analyses were performed using STATA (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

PATIENT CHARACTERISTICS

One hundred and twenty cancer patients completed the survey instrument, with 119 patients reporting their age on the survey and therefore included in this analysis. All participants reported having health insurance. The participants were split into three groups for analysis based on age, young (n=22), middle-age (n=47), and elderly (n=50). The three age cohorts were demographically most similar in female gender (p=1.00), the significant variations included marital status (p=0.029), employment (p<0.001), and whether the patient felt the need to continue working to pay for treatment (p<0.001). The remaining patient characteristics are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| Age <50 (n=22) | Age 50–64 (n=47) | Age ≥ 65 (n=50) | Overall (n=119) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | ||

| Age, years, mean (range) | 42 (22–49) | 58 (50–64) | 72 (65–87) | 61 (22–87) | |

| Gender | |||||

| Female | 11 (50) | 25 (53) | 26 (52) | 62 (52) | p=1.00 |

| Race | |||||

| White | 21 (95) | 37 (79) | 42 (84) | 100 (84) | p=0.526 |

| Black | 1 (5) | 6 (13) | 6 (12) | 13 (11) | |

| Other | 0 (0) | 4 (8) | 2 (4) | 6 (5) | |

| Marital Status | |||||

| Married/ domestic partnership | 12 (55) | 31 (66) | 35 (70) | 78 (66) | p=0.029 |

| Single | 7 (32) | 9 (19) | 2 (4) | 18 (15) | |

| Separated/ divorced | 3 (13) | 6 (13) | 8 (16) | 17 (14) | |

| Widowed | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 5 (10) | 6 (5) | |

| Residential Status | p=0.936 | ||||

| Homeowner | 16 (73) | 35 (75) | 40 (80) | 91 (76) | |

| Rents home | 4 (18) | 8 (17) | 7 (14) | 19 (16) | |

| Other | 2 (9) | 3 (6) | 3 (6) | 8 (7) | |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | |

| Education | p=0.079 | ||||

| Up to High School diploma/ GED/ VoTech | 6 (27) | 23 (49) | 28 (56) | 57 (48) | |

| Some college/ Associates degree | 9 (41) | 7 (15) | 7 (14) | 23 (19) | |

| Bachelor’s degree or greater | 7 (32) | 16 (34) | 15 (30) | 38 (32) | |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | |

| Employment | p<0.001 | ||||

| Retired | 0 (0) | 13 (28) | 39 (78) | 52 (44) | |

| Employed for wages | 13 (59) | 15 (32) | 9 (18) | 37 (31) | |

| Not working | 7 (32) | 17 (36) | 2 (4) | 26 (22) | |

| Missing | 2 (9) | 2 (4) | 0 (0) | 4 (3) | |

| Do you feel the need to continue working to pay for your treatment? | p<0.001* | ||||

| Yes | 15 (68) | 20 (43) | 10 (20) | 45 (38) | |

| No | 5 (23) | 25 (53) | 39 (78) | 69 (58) | |

| Missing | 2 (9) | 2 (4) | 1 (2) | 5 (4) | |

| Annual Household income | p=0.228 | ||||

| < $25,000 | 4 (18) | 9 (19) | 6 (12) | 19 (16) | |

| $25,000 - $74,999 | 8 (36) | 15 (32) | 24 (48) | 47 (39) | |

| ≥ $75,000 | 10 (46) | 21 (45) | 12 (24) | 43 (36) | |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 2 (4) | 8 (16) | 10 (9) | |

| Has health insurance | 22 (100) | 47 (100) | 50 (100) | 119 (100) | p=1.00 |

| I support myself financially* | 17 (77) | 44 (94) | 47 (94) | 108 (91) | p=0.077 |

| How long ago were you diagnosed? | |||||

| Less than 1 year ago | 7 (32) | 8 (17) | 7 (14) | 22 (18) | p=0.627 |

| 1 year to 3 years ago | 2 (9) | 8 (17) | 3 (6) | 13 (11) | |

| 3 years to 5 years ago | 1 (5) | 4 (8) | 5 (10) | 10 (8) | |

| More than 5 years ago | 4 (18) | 5 (11) | 6 (12) | 15 (13) | |

| Missing** | 8 (36) | 22 (47) | 29 (58) | 59 (50) | |

| Is your cancer metastatic | |||||

| Yes | 10 (46) | 17 (36) | 11 (22) | 38 (32) | p=0.097 |

| No | 4 (18) | 8 (17) | 10 (20) | 22 (18) | |

| Missing** | 8 (36) | 22 (47) | 29 (58) | 59 (50) | |

| If metastatic, how long ago did you learn that your cancer had metastasized? | |||||

| Less than 1 year ago | 4 (18) | 10 (21) | 3 (6) | 17 (14) | p=0.294 |

| 1 year to 3 years ago | 3 (14) | 4 (9) | 4 (8) | 11 (9) | |

| 3 years to 5 years ago | 0 (0) | 2 (4) | 3 (6) | 5 (4) | |

| More than 5 years ago | 3 (14) | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 5 (4) | |

| Not metastatic | 4 (18) | 8 (17) | 10 (20) | 22 (18) | |

| Missing** | 8 (36) | 22 (47) | 29 (58) | 59 (50) |

Note: All p values were calculated using Fisher’s exact test.

This is a response to the prompt “Who do you receive financial support from?” This response was expanded in Phase 2 to include support from a spouse.

Participants in Phase 1 were not presented with these questions, they were added to the Phase 2 questionnaire.

CONCERNS

Fifty-four percent of elderly patients indicated no financial concerns, compared to slightly less than half (43%) of middle-age, and a quarter (27%) of the young cohort (p=0.106). The most commonly reported concerns were rent/mortgage (young: 45%, middle-age: 36%, elderly: 12%), paying other bills (young: 55%, middle-age: 43%, elderly: 28%), and medical expenses (young: 43%, middle-age: 32%, elderly: 43%). The significant concerns included rent/mortgage (p=0.003), recreational activities (p=0.030), and buying food (p=0.032). Other financial concerns are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Financial Concerns

| Indicated agreement with the following: | Age <50 (n=22) | Age 50–64 (n=47) | Age ≥ 65 (n=50) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (col%) | N (col%) | N (col%) | ||

| No concerns | 6 (27) | 20 (43) | 27 (54) | 0.106 |

| Student loan debt (for yourself or family) | 4 (18) | 4 (9) | 1 (2) | 0.035 |

| Rent/ Mortgage | 10 (45) | 17 (36) | 6 (12) | 0.003 |

| Paying other bills | 12 (55) | 20 (43) | 14 (28) | 0.078 |

| Buying food | 7 (32) | 10 (21) | 4 (8) | 0.032 |

| Childcare | 3 (14) | 3 (6) | 1 (2) | 0.106 |

| Clothing | 3 (14) | 6 (13) | 4 (8) | 0.688 |

| Recreational activities (ie: movies or vacation) | 6 (27) | 9 (19) | 3 (6) | 0.030 |

| Holidays (ie: gifts or food) | 5 (23) | 10 (21) | 3 (6) | 0.044 |

| Medical expenses | 6 (43) | 8 (32) | 9 (43) | 0.704 |

| Other | 0 (0) | 4 (9) | 5 (10) | 0.398 |

Note: All P values were calculated using Fisher’s exact test. Medical expenses was added to the list in Phase 2, so the sample sizes for this question include: young (n=14), middle-age (n=25) and elderly (n=21).

DISTRESS MEASUREMENTS

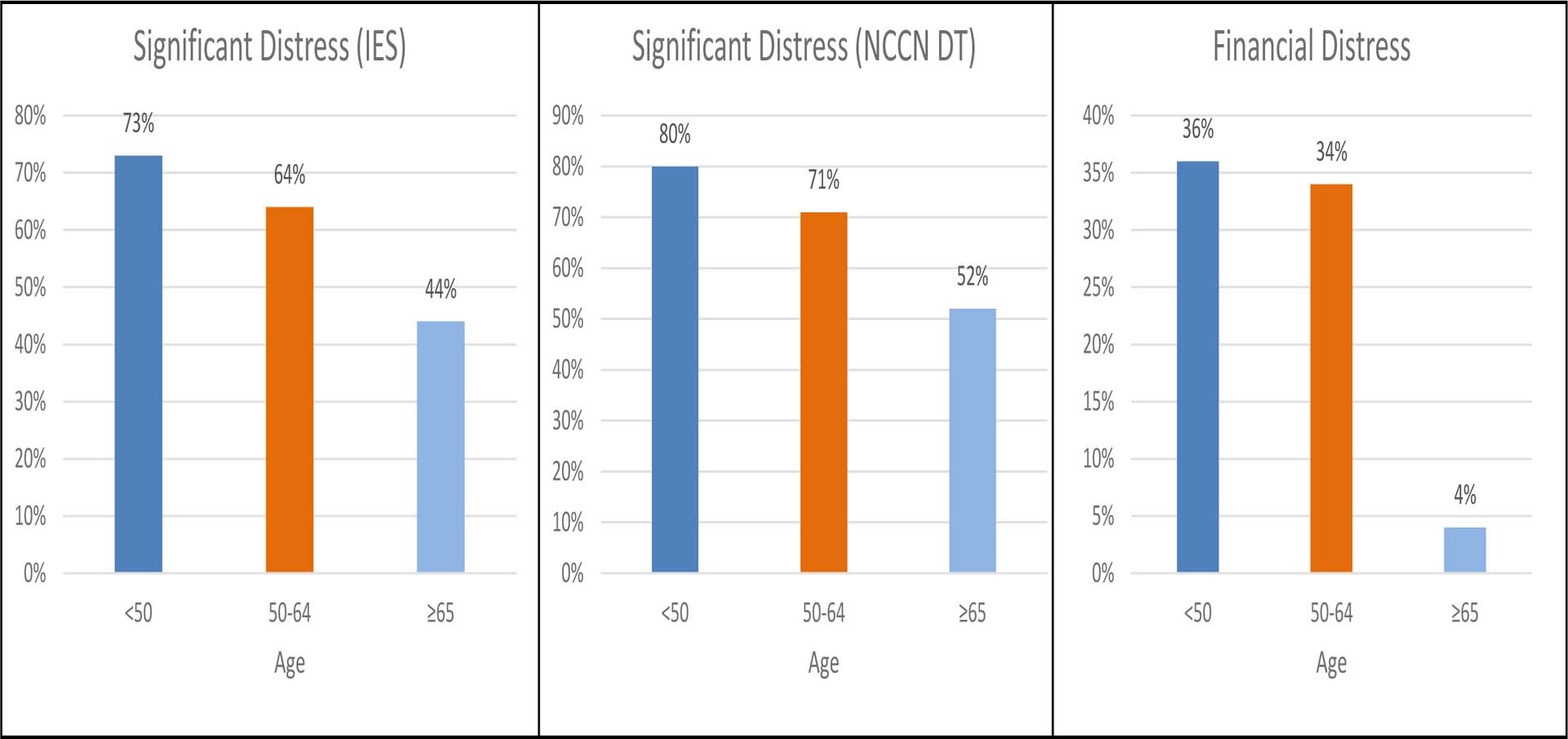

All patients responded to the Impact of Events Scale (n=119). Seventy-three percent (n=16) of the young group, 64% middle-age (n=30) and 44% elderly (n=22) reported scores indicating significant distress. One hundred and eight patients completed the NCCN Distress Thermometer. The mean score for young was 6.1 (standard deviation [SD] =2.9), middle-age 5.4 (SD=2.6) and elderly 4.4 (SD=3.3) (p=0.11 for joint test of three means). Sixteen young (80%), 30 middle-age (71%), and 24 elderly (52%) patients reported clinically meaningful Distress Thermometer scores (p=0.102). Young patients were more likely than elderly to have a higher Impact of Events distress score (p=0.016) and Distress Thermometer score (p=0.048). See Figure 1 for a comparison of distress and financial distress scores in the three cohorts.

Figure 1. Comparisons of significant results on distress and financial distress measures by age.

Note: Breakdown of percentage of patients in the younger, middle age, and older group who met or exceeded the cutoff for each instrument. NCCN DT [National Comprehensive Cancer Network Distress Thermometer]: scores of 4 and greater are indicative of significant distress. IES [Impact of Events Scale]: scores of 26 and greater indicate significant distress. InCharge [InCharge Financial Distress and Financial Well-being Scale]: scores of 4.0 and less indicate financial distress.

FINANCIAL DISTRESS MEASUREMENTS

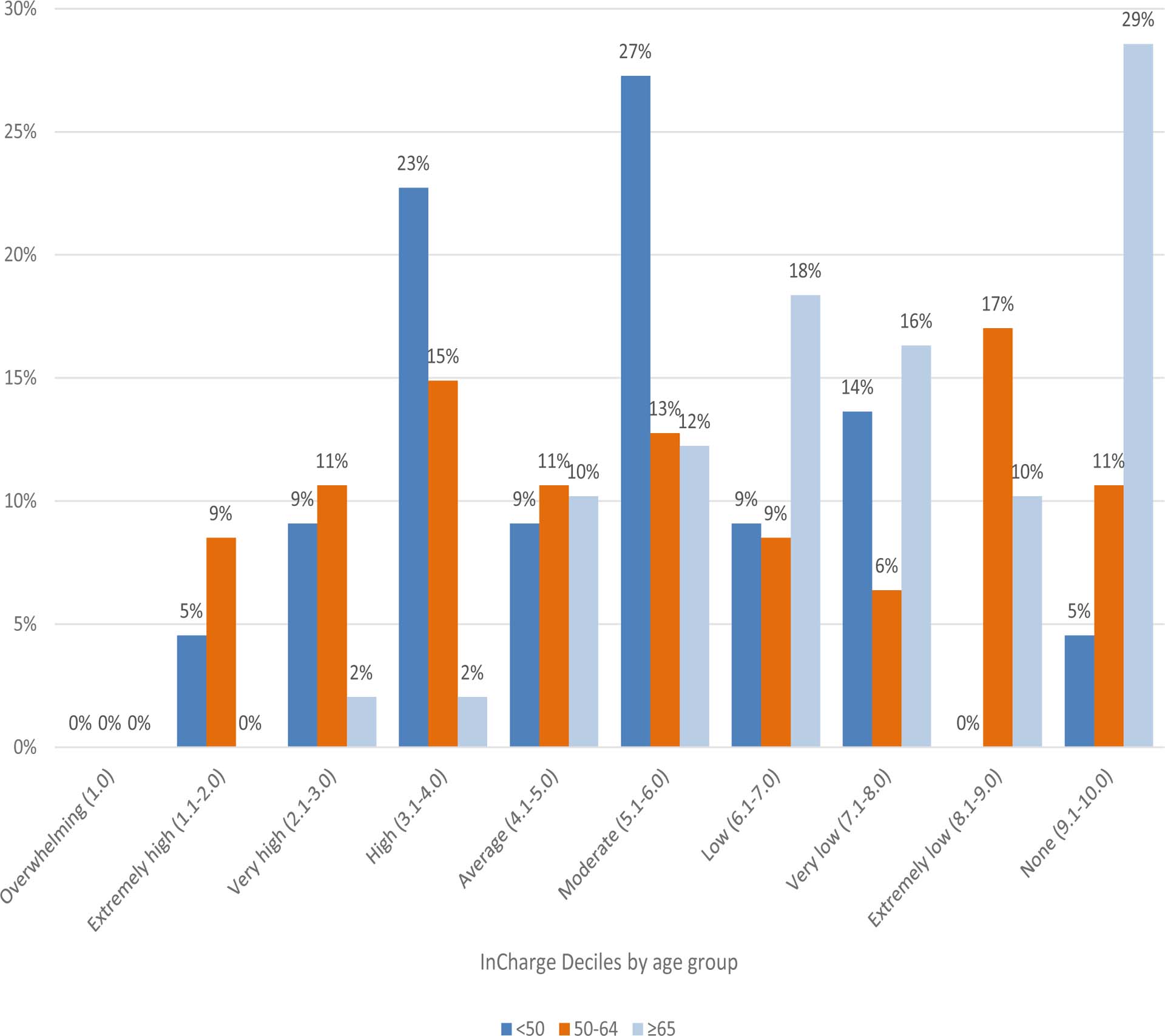

One hundred and eighteen patients responded to InCharge: 22 young, 47 middle-age, and 49 elderly patients. The mean score was lowest (indicating greatest financial distress) in the young group and progressed with age: 5.0 (SD=1.9), 5.7 (SD=2.7), and 7.4 (SD=1.9) (p= <0.001). Eight young (36%) and 16 middle-age (34%) patients reported a score categorized as “financial distress,” compared to only 4% (n=2) of elderly (p <0.001). See Figure 2 for a distribution of scores by normative category.

Figure 2: InCharge Financial Distress and Financial Well-being Scale Scores.

Note: The percent of patients whose averaged score fell in each decile are presented in this figure, separated by age: <50 years old, 50–64 years old, ≥65 years old. Raw calculated scores are divided by 8 (# of questions) to determine the average score, which is presented to 1 decimal point. Scores up to and including 4.0 represent financial distress. Normative descriptors are displayed to label each decile of scores.

MULTIVARIABLE ANALYSES

The results of the multivariable analyses are shown in Table 3. In separate models, both Impact of Events Scale distress and InCharge financial distress were associated with age when controlling for gender, race, marital status, education, employment, income and whether the cancer had metastasized. The association between age and Distress Thermometer did not remain statistically significant on multivariable analysis.

Table 3.

Linear Regression for various distress measurements

| InCharge | Impact of Events Scale | Distress Thermometer | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p | p | p | |||||||

| Age | |||||||||

| Young (<50) | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| Middle-age (50–64) | 0.74 | −0.47–1.95 | 0.23 | −7 | −16.03–2.02 | 0.13 | −1.34 | −3.02–0.34 | 0.12 |

| Elderly (≥65) | 1.52 | 0.03–3.01 | 0.05 | −12.8 | −24.01-(−1.59) | 0.03 | −1.38 | −3.43–0.66 | 0.18 |

| Gender | |||||||||

| Female | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| Male | −0.41 | −1.29–0.46 | 0.35 | −2.7 | −8.95–3.54 | 0.39 | −0.85 | −2.16–0.45 | 0.2 |

| Race | |||||||||

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| Black or African American | −1.25 | −3.22–0.72 | 0.21 | −10.3 | −24.4–3.78 | 0.15 | −0.35 | −3.39–2.69 | 0.82 |

| White | 14 | −1.67–1.96 | 0.88 | −15.33 | −27.66-(−3.01) | 0.02 | −1.33 | −4.14–1.49 | 0.35 |

| Marital | |||||||||

| Married/ Domestic Partner | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| Single/ Divorced/ Separated/ Widowed | 0.89 | −0.03–1.81 | 0.06 | 0.91 | −6.18–7.99 | 0.8 | 0.85 | −2.24–0.53 | 0.22 |

| Education | |||||||||

| Up to high school diploma/ GED/ VoTech | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| Some college/ Associates degree | 0.42 | −0.86–1.7 | 0.52 | −1.2 | −9.1–6.7 | 0.76 | −0.37 | −2.28–1.55 | 0.7 |

| Bachelors degree or greater | 0.28 | −0.69–1.26 | 0.57 | 1.08 | −6.43–8.59 | 0.78 | −0.55 | −2.01–0.9 | 0.45 |

| Employment | |||||||||

| Employed for wages/ Self-employed/ Homemaker | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| Retired/ Out of work but not looking for work | 0.86 | −0.52–2.23 | 0.22 | 2.46 | −6.84–11.76 | 0.6 | 0.39 | −1.34–2.12 | 0.66 |

| Unable to work/ Out of work and looking for work | −1.34 | −2.52-(−0.16) | 0.03 | 3.54 | −5.97–13.06 | 0.46 | 1.81 | 0.3–1.97 | 0.2 |

| Income | |||||||||

| Less than $25,000 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| $25,000 - $74,999 | 0.85 | −0.55–2.24 | 0.23 | −4.87 | −14.74–4.97 | 0.33 | −0.88 | −2.52–0.76 | 0.29 |

| $75,000 and greater | 1.88 | 0.27–3.49 | 0.02 | 0.8 | −10.61–12.21 | 0.89 | 0.18 | −1.61–1.97 | 0.84 |

| Metastasized | |||||||||

| NA | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| No | −0.6 | −1.93–0.72 | 0.37 | 3.4 | −5.09–11.89 | 0.43 | 0.31 | −1.64–2.25 | 0.76 |

| Yes | −0.02 | −0.95–0.91 | 0.96 | 0.49 | −6.64–7.62 | 0.89 | 0.38 | −0.94–1.7 | 0.57 |

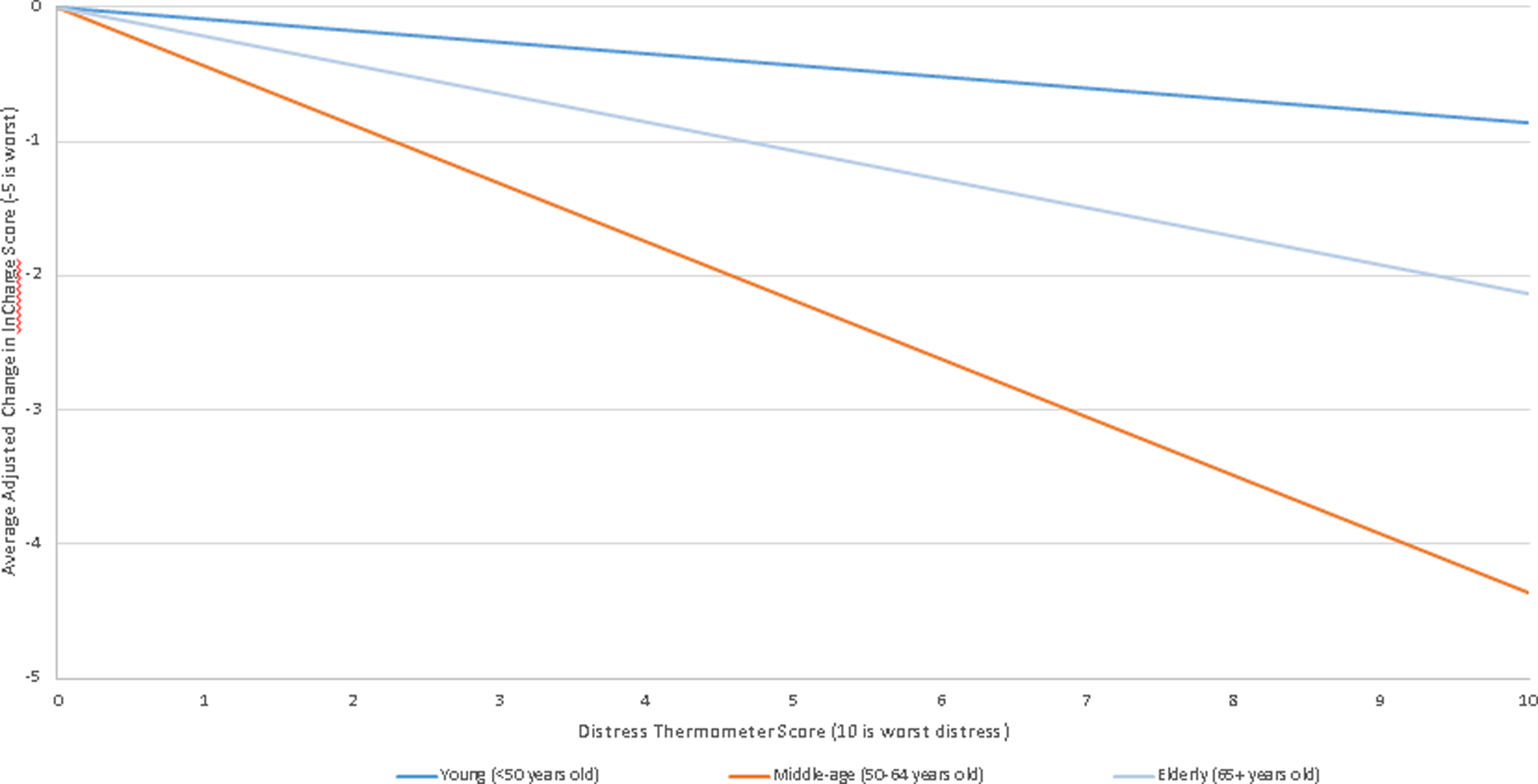

We found that the association between financial distress and overall distress (measured by the Distress Thermometer) varied based on age (Figure 3). Among middle-age patients, the financial distress score (Financial distress was measured using the InCharge Financial Distress/Financial Well-being scale, where scores range from 1.0 to 10.0 and a lower score indicates greater financial distress) decreased by 0.52 points for every one point increase in the Distress Thermometer (Distress Thermometer scores range from 0 (no distress) to 10 (most distress)) (p<0.001) indicating that worsening financial distress was associated with worsening overall distress (i.e. slope of −0.52 for adjusted regression of Financial Distress on Distress Thermometer). However, the association of Financial Distress with the Distress Thermometer among young patients was not statistically significant (adjusted regression slope of −0.09, p=0.581). For elderly patients, a one point increase in the Distress Thermometer decreased the Financial Distress score by 0.30 points (adjusted regression slope of −0.30, p=0.003). The difference in slopes comparing young to middle aged patients was statistically significant (−0.52 versus −0.09, p=0.027), but the difference in slopes comparing young to elderly patients was not statistically significant (−0.09 versus −0.30, p=0.23).

Figure 3. Association between financial distress (InCharge) and distress (Distress Thermometer) by age.

For each one point increase in Distress Thermometer (indicating increased distress), the financial distress score fell (indicating increased financial distress) at various rates based on age. The most significant results were in the middle-age group: the association between InCharge and Distress Thermometer was significant at p<0.001 and significant at p=0.027 when compared to the young group. There was a significant association between InCharge and Distress Thermometer in the elderly group (p=0.003), but there was no significance when compared to the young group (p=0.229).

DISCUSSION

In our group of oncology patients seen at an NCI-designated cancer center, we found significant differences among financial distress and overall distress based on age. The relationship between financial distress and distress was strongest in the middle-age group; as the distress thermometer rises by 1 point, the InCharge scores decrease by 0.52 (P<0.001). This means that for patients aged 50–64, an increased self-reported distress score on the Distress Thermometer was associated with a worse financial distress score on the InCharge. Middle-age patients reported high levels of financial concerns related to paying other bills (43%) and rent/mortgage (36%). In regard to medical expenses, the middle-age group reported the lowest levels of concern (32%) compared to 43% of each the young and elderly group. Financial concerns were reported at all income levels in our patients, indicating that income alone cannot protect against financial distress. All patients had health insurance and most were well-educated and relatively affluent, demonstrating that financial distress cannot simply be attributed to lack of resources. Financial distress is likely a byproduct of external factors, including the cost and burden of treatment, rather than personal socioeconomic resources. The present analysis revealed heightened levels of distress on both the Distress Thermometer and Impact of Events Scale as well as financial distress as measured by the InCharge in both the young and middle-age groups.

In review of relevant literature suggesting greater distress and/or financial distress in younger patients11, 17–19, our conclusions add a level of interconnectedness between the two constructs. Although a relatively small sample, our cross-sectional study population was recruited from multiple outpatient medical oncology clinics as well as our outpatient psychiatry department that treated patients with all cancer types. A recent systematic review of employment issues affecting young adult cancer survivors reported that the distress they face likely has its roots in the high cost of cancer treatments, with the complicating factors of personal mental and physical capability to work in order to earn wages and potentially secure health insurance20.

These findings are significant for several reasons. First, they provide insight into the challenges and concerns working-age cancer patients and their families may face to afford care in an environment of rapidly rising costs. Our findings are consistent with those of other investigators. Kale and Carroll found that cancer survivors experiencing financial burden were more likely to be younger. These patients had greater worries about recurrence and cancer affecting their responsibilities, and also had lower overall physical and mental quality of life scores21. Second, other research has found that younger cancer survivors were more likely to have higher OOP costs and serious psychological distress22, 23, forgo treatment due to cost18, or experience financial distress4, 11, 24, 25. Another study of breast cancer patients found that being middle-aged (ages 46–64) was correlated with treatment nonadherence or financial hardship, and that overall, younger patients were more likely to experience financial hardship17. Additionally, a recent study comparing cancer survivors ages 18–64 to those 65 or older found that nonelderly survivors experienced more material (i.e. filing for bankruptcy, making financial sacrifices to pay for treatment, 28.4% v 13.8%) and psychological (i.e. worrying about paying large medical bills, 31.9% v 14.7%) financial hardship as a result of their cancer and treatment than elderly survivors8. In a study comparing types of cost-coping strategies, younger patients were more likely to decrease their expenses by utilizing care-altering methods (i.e. not filling prescriptions, reducing dosages, skipping appointments or procedures), rather than lifestyle-altering methods (i.e. reduced spending on leisure or basics, used savings, sold possessions), which could result in worse clinical outcomes25.

In addition to potentially having amassed greater savings and assets, older cancer patients are afforded protective economic benefits through Social Security and Medicare, which is not reliant on current employment11. Even in our relatively small sample, the majority of patients in the elderly group reported no financial concerns (54%), although almost one half (43%) did express a concern with medical expenses. An analysis of bankruptcy filings found that a cancer diagnosis made a person 2.65 times more likely to declare bankruptcy. Among cancer patients who filed for bankruptcy, 81% were aged 64 or younger, and each increased year of age reduced the risk of bankruptcy by 20%11. Furthermore, there is an association between filing for bankruptcy and poorer clinical outcomes26, underscoring the importance for clinicians in recognizing financial distress in their patients.

There are many factors that affect the financial stability of an individual or household during a cancer diagnosis. Younger patients are more likely to be employed, and a job loss or extended absence can lead to lost income and possible loss of health insurance. Spouses may struggle with balancing work-related responsibilities with their role as informal caregivers. Although our study did not ask about access to paid sick leave, the significant levels of financial burden reported by working-age patients supports the need for federal laws providing paid sick leave that can also be used for family care27–31. Stage III colorectal cancer patients who reported no access to sick leave also reported higher levels of numerous measures of financial burden than patients with paid sick leave: 28% borrowed money, 29% had difficulties making credit card payments, 50% reduced spending for food and clothing, and 57% reduced recreational spending31. While our patient respondents were generally affluent, well-educated, and insured, Veenstra et al. found that access to paid sick leave is a problem that affects more than just low-income workers or families with low socioeconomic status31. Many patients must take, potentially unpaid, time off work, in order to receive treatment for their cancer; compounding the probable high OOP expenses helps brew a perfect storm of financial burden and distress32.

While we did not ask or make any conclusions about our patients’ individual insurance coverage, it is likely that our patients in the elderly group had greater access to Medicare and were less likely to be reliant on employer-based insurance. Physicians must begin or continue to have difficult conversations regarding the costs of treatments with their patients. These conversations, along with patients understanding their own financial situation, can allow cancer patients to make more economically-informed decisions about their cancer care.

Our results should be interpreted within the limitations of this study. Since patients were approached in clinic after approval from their clinician, they were potentially less likely to be distressed than patients who clinicians did not give permission to approach. We recruited a small number of patients from our outpatient psychiatry clinic, and it is possible they were more distressed than the general outpatient population. Patients completed the survey on their own, but could consult with their family members or the research assistant if necessary. It is possible that the presence of family members could cause the patient to under- or overestimate emotional or financial concerns. The recruitment method utilized was a simple convenience sample, and no efforts were made to recruit patients of any specific demographic, including age. There was no additional insurance information collected, so we are unable to make any conclusions based upon type of insurance or level of coverage. The Comprehensive Score for Financial Toxicity (COST) measure had not yet been published33, 34 at the time of our study, so we did not use a cancer-specific instrument to measure financial distress. We did not collect information about the stage of cancer or time point in treatment, which were limitations due to the cross-sectional nature of the data. Regardless of these limitations, we demonstrate a high level of financial concerns, and that they may be higher among working-age patients. Specifically, we describe some of the additional economic, work-related, and familial strains that could burden a cancer patient of traditional working-age.

While universal screening for distress in cancer patients has been recommended14, 35–37, general uptake of this recommendation has been slow38. While there has not been a similar universal call for specific financial distress screening, a new cooperative group study (SWOG S1417) will focus on bringing a “financial health” assessment into the realm of routine clinical assessment for metastatic colorectal cancer39. Providers and institutions should be aware of the possibility that their working-age patients may experience these burdens at greater rates than their older patients, and specifically address these issues with working-age patients. Elderly patients may have economic protections through Medicare, pensions, and savings. Young patients may not have spouses or children who depend on them financially, and may be less concerned about using financial resources to pay for treatment rather than saving for retirement. The middle-age group may be the goldilocks group at the greatest risk for financial distress: most likely to have financial dependents, most concerned about saving for impending retirement and therefore less willing to go into medical debt, and perhaps less likely to have parents or family members that they could borrow money from. Future work on the topic should include robust data of patients’ insurance type to allow for conclusions to be made about financial distress as a result of specific insurance. Additionally, work comparing interventions based on age groups such as ours could help identify the best way to resolve distress and financial distress related to cancer and its treatments.

Funding:

This study was supported by Core Grant No. P30CA06927.

Footnotes

Author’s Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest: No authors report any conflict of interest.

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bernard DS, Farr SL, Fang Z. National estimates of out-of-pocket health care expenditure burdens among nonelderly adults with cancer: 2001 to 2008. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29: 2821–2826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Howard DH, Molinari NA, Thorpe KE. National estimates of medical costs incurred by nonelderly cancer patients. Cancer. 2004;100: 883–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davidoff AJ, Hill SC, Bernard D, Yabroff KR. The Affordable Care Act and Expanded Insurance Eligibility Among Nonelderly Adult Cancer Survivors. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2015;107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Banthin JS, Bernard DM. Changes in financial burdens for health care: National estimates for the population younger than 65 years, 1996 to 2003. Jama. 2006;296: 2712–2719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Narang AK, Nicholas LH. Out-of-Pocket Spending and Financial Burden Among Medicare Beneficiaries With Cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American Cancer Society. Cancer Treatment and Survivorship Facts & Figures 2016–2017. [accessed 3/24/17.

- 7.Chirikos TN, Russell-Jacobs A, Cantor AB. Indirect economic effects of long-term breast cancer survival. Cancer Pract. 2002;10: 248–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yabroff KR, Dowling EC, Guy GP Jr., et al. Financial Hardship Associated With Cancer in the United States: Findings From a Population-Based Sample of Adult Cancer Survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34: 259–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Altice CK, Banegas MP, Tucker-Seeley RD, Yabroff KR. Financial Hardships Experienced by Cancer Survivors: A Systematic Review. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017;109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meeker CR, Geynisman DM, Egleston BL, et al. Relationships Among Financial Distress, Emotional Distress, and Overall Distress in Insured Patients With Cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramsey S, Blough D, Kirchhoff A, et al. Washington State cancer patients found to be at greater risk for bankruptcy than people without a cancer diagnosis. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32: 1143–1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Horowitz M, Wilner N, Alvarez W. Impact of Event Scale: a measure of subjective stress. Psychosom Med. 1979;41: 209–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Denigris J, Fisher K, Maley M, Nolan E. Perceived Quality of Work Life and Risk for Compassion Fatigue Among Oncology Nurses: A Mixed-Methods Study. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2016;43: E121–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holland JC, Jacobsen PB, Andersen B, et al. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Distress Management. Ft. Washingon, PA: National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jacobsen PB, Donovan KA, Trask PC, et al. Screening for psychologic distress in ambulatory cancer patients. Cancer. 2005;103: 1494–1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prawitz AD, Garman ET, Sorhaindo B, O’Neill B, Kim J, Drentea P. Incharge Financial Distress/ Financial Well-Being Scale: Development, Administration, and Score Interpretation. Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning. 2006;17. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jagsi R, Pottow JA, Griffith KA, et al. Long-term financial burden of breast cancer: experiences of a diverse cohort of survivors identified through population-based registries. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32: 1269–1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shankaran V, Jolly S, Blough D, Ramsey SD. Risk factors for financial hardship in patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy for colon cancer: a population-based exploratory analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30: 1608–1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zafar SY, Peppercorn JM, Schrag D, et al. The financial toxicity of cancer treatment: a pilot study assessing out-of-pocket expenses and the insured cancer patient’s experience. Oncologist. 2013;18: 381–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stone DS, Ganz PA, Pavlish C, Robbins WA. Young adult cancer survivors and work: a systematic review. J Cancer Surviv. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kale HP, Carroll NV. Self-reported financial burden of cancer care and its effect on physical and mental health-related quality of life among US cancer survivors. Cancer. 2016;122: 283–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Han X, Lin CC, Li C, et al. Association between serious psychological distress and health care use and expenditures by cancer history. Cancer. 2015;121: 614–622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arozullah AM, Calhoun EA, Wolf M, et al. The financial burden of cancer: estimates from a study of insured women with breast cancer. J Support Oncol. 2004;2: 271–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zafar SY, McNeil RB, Thomas CM, Lathan CS, Ayanian JZ, Provenzale D. Population-based assessment of cancer survivors’ financial burden and quality of life: a prospective cohort study. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11: 145–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nipp RD, Zullig LL, Samsa G, et al. Identifying cancer patients who alter care or lifestyle due to treatment-related financial distress. Psychooncology. 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ramsey SD, Bansal A, Fedorenko CR, et al. Financial Insolvency as a Risk Factor for Early Mortality Among Patients With Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34: 980–986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.American Public Health Association. Support for Paid Sick Leade and Family Leave Policies. Available from URL: https://www.apha.org/policies-and-advocacy/public-health-policy-statements/policy-database/2014/07/16/11/05/support-for-paid-sick-leave-and-family-leave-policies [accessed 8/5/16.

- 28.Gould E, Filion K, Green A. The Need for Paid Sick Days: The lack of a federal policy further erodes family economic security. Available from URL: http://www.epi.org/files/temp2011/BriefingPaper319-2.pdf [accessed 8/5/16.

- 29.Heymann J, Rho HJ, Schmitt J, Earle A. Contagion Nation: A Comparison of Paid Sick Day Policies in 22 Countries. Washington, DC: Center for Economic and Policy Research, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 30.DeRigne L, Stoddard-Dare P, Quinn L. Workers Without Paid Sick Leave Less Likely To Take Time Off For Illness Or Injury Compared To Those With Paid Sick Leave. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35: 520–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Veenstra CM, Regenbogen SE, Hawley ST, Abrahamse P, Banerjee M, Morris AM. Association of Paid Sick Leave With Job Retention and Financial Burden Among Working Patients With Colorectal Cancer. Jama. 2015;314: 2688–2690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sharp L, Timmons A. The financial impact of a cancer diagnosis: National Cancer Registry/Irish Cancer Society, 2010.

- 33.de Souza JA, Yap BJ, Hlubocky FJ, et al. The development of a financial toxicity patient-reported outcome in cancer: The COST measure. Cancer. 2014;120: 3245–3253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.de Souza JA, Yap BJ, Wroblewski K, et al. Measuring financial toxicity as a clinically relevant patient-reported outcome: The validation of the COmprehensive Score for financial Toxicity (COST). Cancer. 2017;123: 476–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Psychosocial Services to Cancer Patients/Families in a Community Setting Cancer Care for the Whole Patient: Meeting Psychosocial Health Needs. Washington DC: National Academies Press, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Howell D, Mayo S, Currie S, et al. Psychosocial health care needs assessment of adult cancer patients: a consensus-based guideline. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20: 3343–3354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.American College of Surgeons Commision on Cancer. Cancer Program Standards: Ensuring Patient-Centered Care, 2016.

- 38.Zebrack B, Kayser K, Sundstrom L, et al. Psychosocial distress screening implementation in cancer care: an analysis of adherence, responsiveness, and acceptability. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33: 1165–1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shankaran V, Ramsey S. Addressing the Financial Burden of Cancer Treatment: From Copay to Can’t Pay. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1: 273–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]