Abstract

Introduction

Competence in endoscopic haemostasis for acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding (AUGIB) is typically expected upon completion of gastroenterology training. However, training in haemostasis is currently variable without a structured training pathway. We conducted a national gastroenterology trainee survey on haemostasis exposure and on attitudes and barriers to training.

Methods

A 24-item electronic survey was distributed to UK gastroenterology trainees covering the following domains: demographics, training setup, attitudes and barriers, confidence in managing AUGIB independently and exposure to individual haemostatic modalities (supervised and independent). Responses were analysed by region and training grade to assess potential variation in training.

Results

A total of 181 trainees completed the questionnaire (response rate 33.5%). There was significant variation in AUGIB training setup across the UK (p<0.001), with 22.7% of trainees declaring no access to structured or ad hoc training. 31.5% expressed confidence in managing AUGIB independently; this varied by trainee grade (0% of first-year specialty trainees (ST3s) to 60.7% of final-years (ST7s)) and by training setup (p=0.001). ST7 trainees reported lack of experience with independently applying glue (86%), Hemospray (54%), heater probe (36%) and variceal banding (36%). Overall, 88% of trainees desired additional haemostasis training and 89% indicated support for a national certification process to ensure competence in AUGIB.

Conclusion

AUGIB training in the UK is variable. The majority of gastroenterology trainees lacked confidence in haemostasis management and desired additional training. Training provision should be urgently reviewed to ensure that trainees receive adequate haemostasis exposure and are competent by completion of training.

Keywords: gastrointestinal bleeding, bleeding peptic ulcer, oesophageal varices, gastrointestinal haemorrhage

Significance of this study.

What is already known on this topic

Acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding (AUGIB) is a common gastrointestinal emergency. The condition is typically managed by gastroenterologists, who are expected to participate in on-call rotas on completion of training.

What this study adds

There is vast variation in AUGIB training. The majority of gastroenterology trainees do not feel confident in independently managing AUGIB and expressed a desire for additional training to improve confidence.

How might it impact on clinical practice in the foreseeable future

We may need to consider restructuring how we teach trainees to manage an acute gastrointestinal bleed in the UK. This may include simulation-based training, acute upper gastrointestinal bleed courses as well as developing quality assurance measures to ensure competency is reached.

Introduction

Acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding (AUGIB) is a common gastrointestinal emergency with an estimated mortality rate of 8%–14%.1–3 The condition is typically managed by gastroenterologists, who are expected to participate in on-call rotas on completion of training. A recent national survey in 2014 highlighted that 77% of gastroenterology units across the UK had a dedicated out of hours AUGIB service.4 The structure on how this service is delivered remains at the discretion of the individual units, with some reliant solely on a consultant on-call rota, while others formally involve trainee participation with supervision available as required.

From a competency perspective, trainees are assumed to be competent at managing AUGIB on completion of training. However, a structured training programme for AUGIB haemostasis currently does not exist in the UK. In contrast, under the oversight of the Joint Advisory Group on Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (JAG),5 certification pathways have been implemented for upper and lower gastrointestinal endoscopy, which require endoscopists to provide robust evidence of competence before being credentialed for independent, unsupervised practice.6 These standards not only serve as a competency safeguard for patients, but also provide quality assurance of training by placing onus on training programmes to ensure adequate training provision. Indeed, a UK survey published in 2015 reported a decline over time in trainee exposure to AUGIB, with 23% of trainees reporting that they would not feel competent in AUGIB haemostasis by completion of training.7

Recently, the UK has announced reforms in gastroenterology training under the Shape of Training Review, which plans to reduce specialist training from 5 to 4 years.8 This has raised concerns among gastroenterology trainees with regard to endoscopy exposure and whether competence in core endoscopic skillsets is achievable before completion of training. Given the lack of structured training in AUGIB and the proposed changes to training, there is an urgent need to review AUGIB training provision in the UK.

We therefore conducted a national gastroenterology trainee survey on haemostasis exposure and on attitudes and barriers to training. Our specific aims and objectives included the following:

Study exposure to endotherapy during gastroenterology training, and whether this varied nationally.

-

Evaluate quality and provision in AUGIB training, as measured using the study outcomes of:

Confidence in managing AUGIB independently.

Endotherapy experience according to level of training.

Identify barriers to training.

Assess trainee opinion or support for structured training/certification in AUGIB.

Methods

Study design

A prospective electronic survey was distributed to UK gastroenterology trainees via the British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) and regional trainee representatives. The survey was anonymous and approved by the BSG Endoscopy Committee. Data collection was open over a 5-week period (1 March 2019 to 6 April 2019) and two reminder emails were sent to encourage participation. The survey was also promoted through the BSG website.

Survey format

The survey (online supplementary figure 1) comprised a 24-item question panel which were broadly categorisable within the following domains:

flgastro-2019-101345supp001.pdf (272.9KB, pdf)

Trainee demographics.

Training experience.

Availability of training.

Barriers and attitudes to training.

Exposure to individual haemostatic modalities (with and without supervision).

Responses were collected using a Likert-scale ordinal format. Training grades collected ranged from specialist trainee (ST) year 3–7, with ST3 referring to the first year of gastroenterology training and ST7 as the final year.

Study outcomes

The primary outcome studied was whether trainees felt confident in managing AUGIB independently. This was derived from the question: ‘Do you feel confident with managing AUGIB independently?’. Responses collected on a 5-point Likert scale (ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree) were recategorised into a binary category of yes (strongly agree or agree) or no (disagree or strongly disagree), with neutral responses removed from this section of analysis.

The secondary outcomes explored the potential barriers to AUGIB training and the trainee’s opinion on the benefit of compulsory certification for AUGIB certification. Further secondary outcomes were the number of AUGIB procedural numbers. This was defined as the number of hands-on lifetime procedures. For specific haemostasis modalities, this was stipulated to refer to the number of cases requiring therapy, for instance, a patient requiring multiple clips and epinephrine injections would count as one procedure for clip and one for epinephrine injection. Independent procedures referred to those without in-room trainer supervision.

Statistical analysis

All Likert-scale responses were converted to an ordinal numerical scale to facilitate analysis, that is, strongly disagree: 1, strongly agree: 5. Responses were also analysed according to trainee agreement (4 or 5) or non-agreement (scores 1–2) with a statement. The questionnaire was analysed according to trainee perceptions on quality of training and barriers to training, with comparisons made between categorical variables using the χ2 test. Confidence was graded as not confident if scored 1–2 and confident if scored 4–5. Neutral responses were removed from this analysis. For this, the following factors were considered: training region, number of lists per week, JAG certification, trainee grade. Deaneries were categorised by Local Education Training Board into the following regions9: Northern Ireland, Scotland, Wales and four English regions (North, Midlands and East, London, South). For the analysis the North and South of England were separated by the midland deaneries. A p value of 0.05 or less was considered statistically significant. All analyses were undertaken using SPSS V.25.

Results

Survey respondents

A total of 181 trainees completed the questionnaire, giving a response rate of 33.5% (181/540). Trainee grades comprised: ST3—29 (16.0%), ST4—30 (16.6%), ST5—44 (24.3%), ST6—50 (27.6%) and ST7—28 (15.5%). Trainees were from the following regions: England (London—56, Midlands and East—55, North—16, South—12), Scotland 30, Wales 8, Ireland 4. There were no significant differences in trainee grades by region (p=0.261). The majority of respondents (84.5%) had been awarded JAG certification in upper gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy.

Access to training

Training setup

Overall, 22.7% of trainees reported having no structured training in AUGIB, 50.3% having access to ad hoc training defined as any form of training which had no structured pattern, 6.6% reporting daily access to AUGIB/inpatient lists and 20.4% receiving training as part of an AUGIB on-call rota. Across the UK, there was significant variation in access to endotherapy training (p<0.001) (table 1 and online supplementary figure).

Table 1.

Regional differences in access to AUGIB training

| No structured training (%) | Access to ad hoc training (%) | Daily access to inpatient/ AUGIB list (%) |

Training as part of an on call AUGIB rota (%) | |

| Ireland | 0.0 | 25.0 | 25.0 | 50.0 |

| London | 28.6 | 39.3 | 8.9 | 23.2 |

| Midlands | 25.5 | 47.3 | 5.5 | 21.8 |

| North | 12.5 | 56.3 | 6.3 | 25.0 |

| Scotland | 20.0 | 70.0 | 3.3 | 6.7 |

| South | 25.0 | 50.0 | 0.0 | 25.0 |

| Wales | 0.0 | 75.0 | 12.5 | 12.5 |

| Total | 22.7 | 50.3 | 6.6 | 20.4 |

AUGIB, acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding.

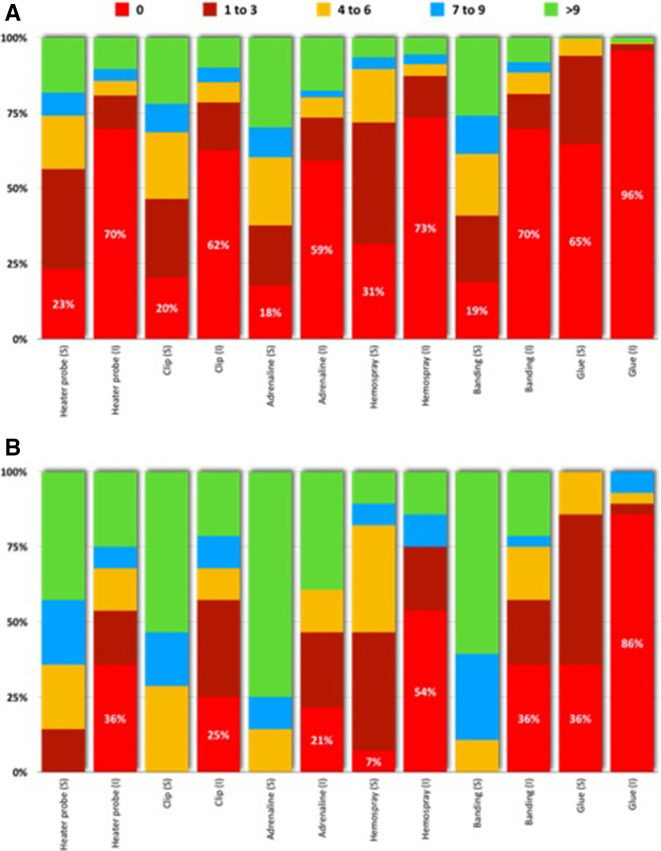

Exposure to haemostatic modalities

The frequency distribution of trainee exposure to individual haemostatic modalities is presented in figure 1A. Across all trainees, 65% reported having performed no glue procedures under supervision, with 96% lacking independent exposure to glue. At least 20% of respondents had yet to apply clips (20%), heater probe (23%) and Hemospray (31%) under trainer supervision, with higher proportions yet to perform these procedures independently. In the subgroup of ST7 respondents (figure 1B), 36% had not performed glue procedures under supervision. This subgroup indicated lack of experience with independently applying glue (86%), Hemospray (54%), heater probe (36%) and variceal banding (36%). ST7 trainees had most experience with epinephrine, with 75% and 43% of trainees reporting experience with at least 10 supervised and independent cases, respectively. The distribution of haemostatic procedures (both in terms of supervised and independent cases) did not vary significantly between the training regions.

Figure 1.

Distribution of haemostatic procedures performed under supervision (S) and independently without supervision (I), presented for the entire cohort (A) and for ST7 trainees (B).

Trainee confidence in endotherapy

In total, 31.5% of trainees expressed confidence in managing AUGIB independently (figure 2). This outcome varied by training grade (p<0.001), with rates increasing from 0% of ST3s to 60.7% of ST7s (figure 1), but not by region (p=0.213). On univariable analysis, trainee confidence also varied according by access to AUGIB training (p=0.001). Confidence rates ranged from 23.1% (ad hoc training), 24.4% for those with no access to structured training, 41.7% (daily access to AUGIB training), to 56.8% (training as part of AUGIB rota). 88% of trainees expressed a desire for additional haemostasis training.

Figure 2.

Confidence in acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding (AUGIB) management and demand for AUGIB training by grade of survey respondent.

Barriers to training

Trainees were asked to indicate their perceptions of barriers to training (table 2). The most commonly perceived barrier was the commitment to general internal medicine (eg, on-calls), which was reported in 93.4%, followed by the lack of structured training opportunities (85.6%) and non-participation on the AUGIB rota (75.7%). There were no significant differences in Likert scale responses by training region or grade (all p>0.05).

Table 2.

Perceived barriers to AUGIB training

| I consider the following to be a barrier to AUGIB training | Strongly disagree (%) | Disagree (%) | Neutral (%) | Agree (%) | Strongly agree (%) |

| Lack of structured training opportunities | 0.6 | 6.1 | 7.7 | 46.4 | 39.2 |

| Not being part of the AUGIB rota | 2.2 | 9.4 | 12.7 | 33.7 | 42.0 |

| Ad hoc service performed by consultant colleagues | 1.7 | 12.2 | 23.2 | 47.5 | 15.5 |

| Competing pressures from GI training/on call | 2.2 | 30.4 | 23.8 | 29.3 | 14.4 |

| Competing pressures from GIM training/on-call | 0.0 | 0.6 | 6.1 | 26.5 | 66.9 |

| I have no interest in managing AUGIB | 84.0 | 15.5 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 0.0 |

| Lack of courses/e-learning | 5.0 | 32.0 | 26.5 | 28.7 | 7.7 |

AUGIB, acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding; GI, gastrointestinal; GIM, general internal medicine.

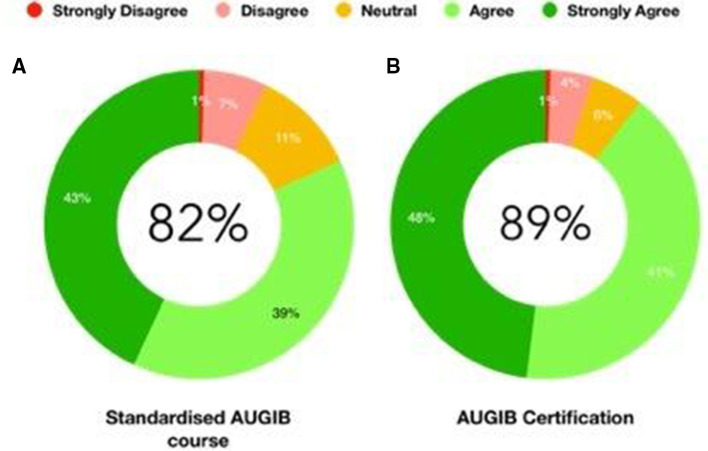

Potential solutions

Trainees were also surveyed on potential interventions to improve AUGIB training (figure 3). Overall, 82% supported the role of a national standardised AUGIB course. In total, 89% of trainees indicated that, assuming adequate training was made available, they would support a national certification process to ensure competency in AUGIB. Responses did not vary by region, although a statistically significant differences were noted by grade (p=0.04), with support for certification ranging between 82.0% (ST6), 84.1% (ST5), and >96% (ST3, ST4 and ST7s).

Figure 3.

Trainee support for (A) a standardised acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding (AUGIB) course, (B) certification in AUGIB.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first UK survey to assess gastroenterology trainee’s exposure to AUGIB and assess their confidence in managing AUGIB. The survey highlighted that 31.5% of trainees expressed confidence in managing AUGIB independently. This outcome varied by training grade, with rates increasing from 0% of early trainees (ST3s) to 60.7% of those at the end of training (ST7s).

Importantly, in the ST7 subgroup, trainees lacked independent exposure particularly in the procedures of glue (86%), Hemospray (54%), banding (36%) and heater probe (36%). Considering that this subgroup would be imminently expected to complete training and participate in an on-call service, assessing and supporting the training needs of these trainees should be prioritised. Indeed, 82% of ST7s expressed a desire for further training in endotherapy with 89% of trainees expressing a desire for certification in AUGIB prior to Certificate of Completion of Training (CCT). Over 70% of trainees reported that a significant barrier to AUGIB training was lack of exposure to an AUGIB rota, which are usually consultant-led. This suggests that on-call consultants may have a positive role in AUGIB training by facilitating trainee exposure to ad hoc training by facilitating trainees to accompany them to urgent AUGIB procedures. Significantly, almost all trainees reported that being part of a general internal medical was a significant barrier to AUGIB training.

Our results are in keeping with the existing literature which highlight shortfalls in AUGIB management training. Data from 765 UK trainee portfolios revealed that 37.1% had not performed band ligation, 50.7% had not placed a clip and 54% had not used heater probe at the point of gastroscopy certification.10 Lack of access to training is a particular issue; data from Penny et al suggest that only 15% of AUGIB cases are performed by trainees, with the majority of these cases being low-risk.7 With quality training, high-risk procedures performed by senior trainees can have comparable survival rates to those performed by consultants.11

Exposure to the use of glue in controlling AUGIB was particularly poor. This is supported by the National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcomes and Deaths report which found that only 53% of consultant gastroenterologists were confident in using glue12 and data from the UK JAG Endoscopy Training System e-portfolio has demonstrated a lack self-reported glue procedures prior to CCT.13 This is of particular concern given that glue is the primary haemostatic modality for gastric variceal bleeding although could also reflect the relatively low uptake of this treatment modality in the UK.

Our study has several limitations. As with all surveys, this study carries an innate risk of selection bias. Despite our survey reaching over a third of UK gastroenterology trainees, there were some regions that were poorly represented such as North East England and the South, and it is possible for more junior grades to be under-represented. Next, procedural data were collected in categorical groupings rather than continuous format to facilitate survey completion. This precluded the option of aggregating supervised and independent procedures. We acknowledge this delineation to be potentially an arbitrary one, that is, that overlap may exist between supervised and independent procedures, as high-risk emergencies may be performed under supervision, even in the context of an experienced trainee. Furthermore, it is possible that senior trainees in particular are capable of performing bleeding therapy without consultant assistance (even if they feel underconfident) which may change the overall impression of the results. We also appreciate that the more senior trainees are probably the most important group in this study, due to their imminence of independent practice. Unfortunately, we were unable to detail the percentage of senior colleagues represented in this survey which we acknowledge as a limitation. Finally, while confidence in managing AUGIB was selected as a study outcome, we acknowledge that confidence does not equate to competence, which could not be assessed within the confines of this survey.

Moving forward, there have been proposals to create a dedicated training programme in therapeutic endoscopy.14 Simulation-based training is being piloted to expedite competency development in diagnostic gastroscopy15 as a precursor to haemostasis training. Collaborative endeavours between BSG and JAG have led to the development of standardised, quality-assured AUGIB courses aimed at delivering haemostasis theory and simulation-based training.16 These courses could be adapted in response to our survey results to accommodate areas of need, for example, glue and improve confidence. In line with other endoscopic modalities, plans are underway to develop a certification pathway in AUGIB haemostasis. This would be used in conjunction with the National Endoscopy Database infrastructure17 to ensure that accountability is placed on training programmes and endoscopy units to support competency development in a transparent manner. With the advent of Shape of Training reforms, these quality assurance measures are arguably necessary for the benefit of patients and trainees alike. Importantly, units should try and help facilitate further AUGIB exposure for trainees which may include, implementation of dedicated early morning slots and involvement in bleed rotas where possible. Finally, it is important to appreciate that in many units, newly appointed consultants have the opportunity to receive further AUGIB support and training from more senior colleagues, which may further help improve confidence in the management of an AUGIB.

Conclusion

This survey has highlighted variation in AUGIB training. The majority of trainees did not feel confident in independently managing AUGIB and expressed a desire for additional training to improve confidence. Further exposure to AUGIB and assessment of competencies may lead to an increase in confidence in managing AUGIB which we speculate may increase competence in AUGIB management.

Footnotes

Twitter: @Drkeithsiau

Contributors: JPS, KS, CK, PD and AJM designed the study. JPS, KS designed the survey, analysed the data and wrote the manuscript. AA helped with the statistical analysis. All authors contributed to critical revisions of the manuscript. AJM is the guarantor of the article.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available upon reasonable request.

References

- 1. Rockall TA, Logan RFA, Devlin HB, et al. . Incidence of and mortality from acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage in the United Kingdom. BMJ 1995;311:222–6. 10.1136/bmj.311.6999.222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Blatchford O, Davidson LA, Murray WR, et al. . Acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage in west of Scotland: case ascertainment study. BMJ 1997;315:510–4. 10.1136/bmj.315.7107.510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hearnshaw SA, Logan RFA, Lowe D, et al. . Acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding in the UK: patient characteristics, diagnoses and outcomes in the 2007 UK audit. Gut 2011;60:1327–35. 10.1136/gut.2010.228437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. NICE NICE support for commissioning for acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Siau K, Green JT, Hawkes ND, et al. . Impact of the Joint Advisory Group on Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (JAG) on endoscopy services in the UK and beyond. Frontline Gastroenterol 2019;10:93–106. 10.1136/flgastro-2018-100969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Siau K, Anderson J, Valori R, et al. . Certification of UK gastrointestinal endoscopists and variations between trainee specialties: results from the JETS e-portfolio. Endosc Int Open 2019;07:E551–60. 10.1055/a-0839-4476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Penny HA, Kurien M, Wong E, et al. . Changing trends in the UK management of upper GI bleeding: is there evidence of reduced UK training experience? Frontline Gastroenterol 2016;7:67–72. 10.1136/flgastro-2014-100537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Clough J, FitzPatrick M, Harvey P, et al. . Shape of training review: an impact assessment for UK gastroenterology trainees. Frontline Gastroenterol 2019;10:356–63. 10.1136/flgastro-2018-101168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. BMA Deaneries and HEE local offices. Available: https://www.bma.org.uk/advice/career/applying-for-training/find-your-deanery [Accessed 5 Oct 2019].

- 10. Siau K, Dunckley P, Anderson J, et al. . PTU-010 Exposure to endotherapy for upper gastrointestinal bleeding at the point of gastroscopy certification – is it sufficient? Gut 2017;66:A55. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mohammed N, Rehman A, Swinscoe M, et al. . Outcomes of acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding in relation to timing of endoscopy and the experience of endoscopist: a tertiary center experience. Endosc Int Open 2016;04:E282–6. 10.1055/s-0042-100193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Alleway R, Butt A, Freeth H, et al. . Improving the quality of healthcare time to get control? time to get control?.

- 13. Siau K, Morris AJ, Murugananthan A, et al. . Variation in exposure to endoscopic haemostasis for acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding during UK gastroenterology training. Frontline Gastroenterol 2020;11:436–40. 10.1136/flgastro-2019-101351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Anderson J, Lockett M. Training in therapeutic endoscopy: meeting present and future challenges. Frontline Gastroenterol 2019;10:135–40. 10.1136/flgastro-2018-101086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Khan R, Plahouras J, Johnston BC, et al. . Virtual reality simulation training for health professions trainees in gastrointestinal endoscopy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018;8:CD008237 10.1002/14651858.CD008237.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Siau K, Morris AJ. A call to arms for change: the UK strategy to improve standards of care in acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. United European Gastroenterol J 2019;7:449–50. 10.1177/2050640619828216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lee TJ, Siau K, Esmaily S, et al. . Development of a national automated endoscopy database: the United Kingdom national endoscopy database (NED). United European Gastroenterol J 2019;7:798–806. 10.1177/2050640619841539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

flgastro-2019-101345supp001.pdf (272.9KB, pdf)