Abstract

We analyzed the spread of the COVID-19 epidemic in 6 metropolitan regions with similar demographic characteristics, daytime commuting population and business activities: the New York metropolitan area, the Île-de-France region, the Greater London county, Bruxelles-Capital, the Community of Madrid and the Lombardy region. The highest mortality rates 30-days after the onset of the epidemic were recorded in New York (81.2 x 100,000) and Madrid (77.1 x 100,000). Lombardy mortality rate is below average (41.4 per 100,000), and it is the only situation in which the capital of the region (Milan) has not been heavily impacted by the epidemic wave. Our study analyzed the role played by containment measures and the positive contribution offered by the hospital care system. (www.actabiomedica.it)

Keywords: COVID-19, Mortality, Metropolitan regions, Hospital care system

Introduction

As history taught us, many airborne transmitted diseases - causing large epidemics - spread along trade routes and had the most dramatic effects in large urban areas in terms of infections, incidence and mortality. As it happened during the Black Death, a centripetal trend is even recurring nowadays (1), with the COVID-19 pandemic that, as of the 14th of April 2020, has surpassed 2 million notified cases (although these data largely underestimate the real situation) and 120,000 confirmed deaths, affecting large metropolitan areas for the most part (2). A precise track of the infection spread, across different geographical areas, is complicated by the globalization that, also, greatly improve the risks posed by trade routes (3), people gathering (4) and work activities (5).

Therefore, it is not by chance that in industrialized countries the diffusion of SARS-CoV-2 had a greater effect in the areas surrounding large urban centers (6): as London, Paris, New York, Madrid, Bruxelles and Milan amongst others. All these cities share similar characteristics and well-established commercial exchanges with China, where the virus dissemination started between the end of 2019 and January 2020.

Preventive actions have changed from the past: in addition to quarantine, health authorities took advantage from limitations of mobility (7), lockdown measures, the establishment of “red zones” (8), contact tracing (6), home fiduciary isolation (9) and the availability of new technologies (10), together with an adequate risk communication (11,12). These measures acquire a crucial importance considering the current lack of treatment and vaccinations.

With respect to the past centuries, the healthcare systems, and in particular hospitals with intensive care capacity, played an important role in saving lives but were also an important mean of infection dissemination (13), as it happened with the SARS epidemic (14), and at the beginning of the COVID-19 epidemic (15). The infection of patients and healthcare workers in the hospitals of Codogno and Casalpusterlengo – which were the first sites in which cases of local Italian transmission were confirmed (16) – showed how COVID-19 has a high tendency of diffusion in healthcare environments (hospitals) and residential care (nursing homes), that incidentally host individuals that are frail and at high risk (of older age and/or affected by chronic conditions).

This epidemiological study, conducted within the School of Public Health of Vita-Salute San Raffaele University, analyzes six geographical settings that include relevant metropolitan areas, and aims at evaluating the diffusion of COVID-19 and its mortality, to assess the reaction of healthcare systems, and lastly, to estimate the dynamics spread of the epidemic and the efficacy of the healthcare measures implemented.

Methods

For each included metropolitan area, we built a profile which included administrative, demographic and social characteristics (the latter was estimated in terms of daytime commuting population). We retreived the number of available hospital beds, with a focus on intensive care units, and the measures implemented by health authorities to cope with the epidemic. With respect to COVID-19, we analyzed the number of deaths and draw mortality curves, starting with the day during which the first 3 deaths were declared in each area. Furthermore, we analyzed mortality rate at the level of regional and metropolitan areas, to evaluate centripetal trend of the epidemic. Finally, we analyzed in details the case of Lombardy and in particular the metropolitan area of Milan due to its peculiar features, and because its mortality rates has been considered to be abnormal (17). Additionally, we examined the containment measures implemented by the healthcare authorities to reduce the inter-human transmission. Moreover, we reported the number of patients admitted, for COVID-19, to two Italian National Institutes for Scientific Research (IRCCS), since the beginning of the epidemic to date. Moreover, we anonymously retrieved their residence.

Results

First, we describe the characteristics of the six metropolitan areas in terms of demographic data, increase in daytime population, and healthcare:

New York – We analyzed the metropolitan area of New York City, with five boroughs (Manhattan, The Bronx, Queens, Brooklyn and Staten Island), a population of 8,388,748 and density of 10,715 people/km2 (18). Manhattan is the most densely populated, with 26,821.6 inhabitants/km2 (19), and an increase of daytime population of 1,499,757 commuters (20). In New York City there are 23,000 hospital beds (21) (2.74 per 1,000 inhabitants), which increased to 38,400 since to the COVID-19 epidemic (22) (4.57 per 1,000 residents, 67% increase). At the beginning of the epidemic, 2,449 intensive care beds were available in New York City (23), and increased of 62% (total available 3,965) by 10th April 2020 (24). Table 1 shows mortality data starting from the beginning of the epidemic (15th March 2020) (25).

Table 1.

Cumulative mortality rate (x 100,000) in the six metropolitan areas analyzed

| Area | Population x 1,000 | Beginning of the epidemic* | Increase of beds in intensive care units | Number of deaths | Cumulative mortality rate° |

| New York City | 8,623 | 15th March | 67.0% | 7,429 | 81.2 |

| Community of Madrid | 6,662 | 06th March | 115.6% | 5,136 | 77.1 |

| Bruxelles-Capital | 1,209 | 11st March | 40.0% | 587 | 48.6 |

| Lombardy (Milan) | 10,088 | 23rd February | 114.0% | 4,178 | 41.4 |

| Ile-de-France (Paris) | 12,278 | 11st March | 109.0% | 3,040 | 26.9 |

| Greater London | 9,304 | 7th March | 19.8% | 2,193 | 23.0 |

*Considered as the day during which the first 3 deaths were recorded; °Considered the 30th day since the beginning of the epidemic

Bruxelles – The Bruxelles-Capital Region has a population of 1,208,542 people and a population density of 7,489 people/km2 (26). The central area includes the city of Bruxelles (181,726 inhabitants, and population density of 5,570 people/km2) (27), and 324,000 people commute there every day, in addition to the city residents and the European Commission visitors (28). Bruxelles-Capital Region has an availability of 6.74 hospital beds per 1,000 population (29). In Belgium, 1,900 intensive care beds increased by 40% during the epidemic (11th March 2020) (30).

Community of Madrid – The Community of Madrid has 6,661,949 inhabitants and a population density of 829.84 people/km2 (31,32). The metropolitan area of Madrid has 3,266,126 inhabitants and a population density of 5,265 people/km2, in addition it receives around 345,000 workers daily and 27,000 turists (33). In 2017 the region had 20,458 hospital beds (3.14 per 1,000 people), among public and private structures (34). The 800 intensive care beds of the region increased to 1,725 to treat patients affected by COVID-19 (35). To cope with the high number of patients during the epidemic, the Ifema field hospital has been built, and it can accommodate 5,000 beds in 9 pavilions (35). On the 1st April 2020 the number of hospitalized people in the region of Madrid reached a peak value with 15,227 occupied hospital bed and 1,528 patients in intensive care units (35). On 1st of April 2020, the Ifema hospital hosted 930 patients, 16 of which in intensive care beds. Table 1 shows mortality data starting from the beginning of the epidemic (6th March 2020) (35).

Île-De-France (Paris region) – We analyzed the region of Île-de-France, with 8 Département, a total population of 12,278,210 (18% of metropolitan France population) and a population density of 1,022.25 people/km2 (36). It includes the city of Paris, divided into 20 arrondissement, with 2,148,271 inhabitants and a population density of 20,382 people/km2 (37), with a daytime increase in population of 570,000 people commuting from Île -de-France (38). Île-de-France counts 5.94 hospital beds per 1,000 inhabitants (2014 update). In 2018 the region had 1,275 intensive care beds (471 in Paris (39)), that increased by 109% to 1,390 (40) since the beginning of the epidemic. This was achieved by increasing the 3,000 intensive care beds that were already available in the region, which is sustained by private healthcare hospitals by 23.4% (39). Table 1 shows mortality data starting from the beginning of the epidemic (11th March 2020) (41).

Greater London – The county of Greater London has 8,899,375 and a population density of 5,671/km2. Inner London forms the central part of Greater London with 12 boroughs and the City of London; it has 3 million residents (42) and a density of population of 9,404/km2). The daytime population creases by a million of commuters daily (42). In Greater London there are 21,361 NHS hospital beds open overnight, 1,507 of which are reserved for intensive care (43). To cope with the increase in patients due to the epidemic, private hospitals signed an agreement to provide more than 2,000 hospital beds, and 250 between operating rooms and intensive care beds (44). Furthermore, the “NHS Nightingale Hospital London” has been temporarily set up in the ExCeL convention center. It hosts 500 intensive care beds, but it can receive up to 4,000 patients (45). Thanks to this measure, the total number of hospital beds increased by 12.9%, and the number of intensive care beds increased by 49.8%. Table 1 shows mortality data starting from the beginning of the epidemic (7th March 2020) (46).

Lombardy (Milan Region) – The Lombardy Region, with a population of 10,060,574 people and a population density of 422 inhabitants per km2. The central metropolitan area of Milan, which consists of the city of Milan and other 133 municipalities, with a total of 3,250,315 inhabitants and a population density of 2,063 inhabitants per km2 (47), in addition to 1,441,409 people that commute every day. The Lombardy Region consists of several highly populated areas in proximity to Milan (Bergamo, Brescia, Monza, etc). The intensive care beds available were 723 at the onset of the epidemic, which increased to a total of 1,547 beds reserved for patients affected by COVID-19 after 30 days. This resulted in an increment of 113.9%, and it includes only 10 of the potential 500 additional beds allocated in the Milano Fiera pavilions. Table 1 shows mortality data (48) starting from the beginning of the epidemic (23rd February) (49).

Figure 1 represents the epidemic progress in the six areas via cumulative daily mortality rate. We decided to put the analytic comparison at day 30 from the beginning of the outbreak (when 3 deaths were reported), due to the different chronological development in each zone: day 30 is the time at which we calculated the mortality rates for each area (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Cumulative daily mortality rate in the six areas

Since China issued the first warnings about the COVID-19 outbreak, European and USA health authorities planned new preventive measures in order to avoid the spread of the virus. These actions (as health check-points in airports, quarantine for people arriving from Hubei region, contact tracing and isolation) proved to be inefficient in the prevention of a massive implication of the major metropolitan areas of the western world. Italy was the first European country to declare endemic cases, and it was the first country to report outbreaks in Lombardy and Veneto regions (50). Table 2 describes the most relevant actions taken by the Government from February 21st to April 4th 2020. Similar measures were also adopted by the local Governments of the administrative areas analyzed in this report. One of the measures implemented was the increase in the number of hospital beds and intensive care beds, as the normal hospital capacity was not able to host the number of COVID-19 cases requiring hospitalization.

Table 2.

Health protection measures against COVID-19 in Lombardy Region, 21 February – 4 April 2020

| Date | Public Health Measures | Authority |

| 21 February 2020 | Mandatory supervised quarantine for 14 days for all individuals who have come into close contact with confirmed cases of disease; Mandatory communication to the Health Department from anyone who has entered Italy from high-risk of COVID-19 areas, followed by quarantine and active surveillance. |

Ministry of Health |

| 23 February 2020 | Red zones in 11 municipalities in Lombardy Region: adoption of an adequate and proportionate containment and management measures in areas with >1 person positive to COVID-19 with unknown source of transmission. | National Government |

| 23 February 2020 | Development of a toll-free number for population | Lombardy Region |

| 08 March 2020 | Lock-down: avoid any movement of people except for motivated by proven work needs or situations of necessity (health, food and assistance); | National Government |

| 08 March 2020 |

|

Lombardy Region |

| 09 March 2020 | Public communication campaign on social network #fermiamoloinsieme | Lombardy Region |

| 11 March 2020 | Suspension of all commercial activities non-indispensable for production. | National Government |

| 23 March 2020 |

|

Lombardy Region |

| 30 March 2020 | Further identification of day-care structure to isolate asymptomatic or low symptomatic subjects | Lombardy Region |

| 4 April 2020 | Use of face mask (or other supply) for the whole population | Lombardy Region |

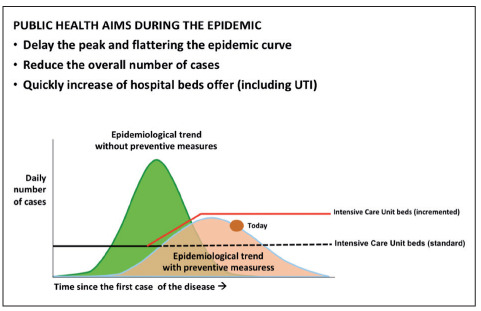

As an example, we reported the cases of the Lombardy region and Greater London areas – as these two entities have similar healthcare systems – in which the public health authorities arranged agreements with private hospitals in order to face the increased demand for healthcare assistance. Figure 2 shows the flattening of the epidemic curve as a result of public health interventions, with the increase of the hospital capacity, variously needed, in all the different areas analyzed.

Figure 2.

Epidemiological trend and public health measures (“flattening” the curve)

We decided to investigate further the Lombardy case, as it was the first to be described in the press and to be of great scientific interest for its alleged excess of deaths (45). The crude fatality rate (number of deaths/number of notified cases) is largely affected by the number of the tests performed and its results are not significant, so we analyzed the mortality rate (Table 1). It showed that, besides the higher number of deaths and the delay of the start of the epidemic in the different areas, the trend documented in the Lombardy region is significantly lower than three areas with the highest mortality (New York, Madrid and Bruxelles). Lombardy region is slightly higher than Paris and London, even though it has a wider surface area.

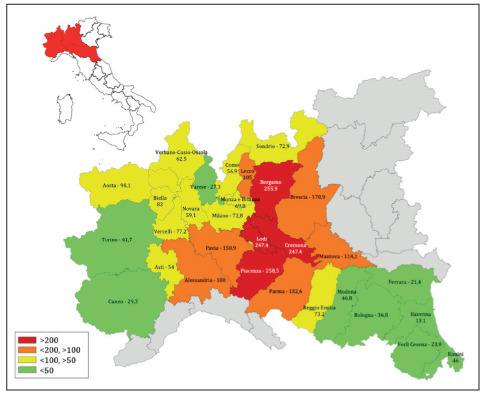

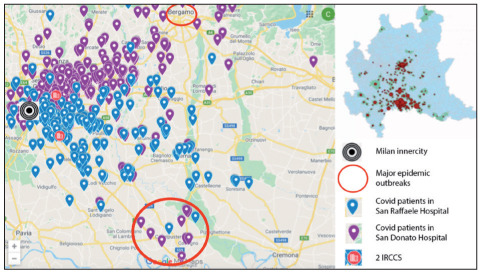

We believe that such trend recorded in the Lombardy region – despite the earlier start of the epidemic – is due to the fact that the metropolitan area of Milan has never been heavily hit by the epidemic wave, as clearly shown considering mortality rates in the provinces of Lombardy ad surrounding regions (Figure 3) (51). As an example, we took into account the domicile of 1,058 COVID-19 patients admitted to two National Institutes for Scientific Research (IRCCS), situated just outside the areas in which the two outbreaks took place, 50 kilometers outside of Milan (Figure 4). The data shows that most of these patients came from areas located between the cities involved by the first outbreaks and the city of Milan. This suggest that these two hospitals (as well as the others in the metropolitan area of Milan) have not payed a role as multiplier of SARS-CoV-2 infections as probably happened in smaller-sized hospitals - as for instance hospitals of Lodi and Codogno - in the first phase of the epidemic.

Figure 3.

Cumulative mortality rate per 100,000 population in the Provinces of four Regions of Northern Italy, last update 17th April 2020

Figure 4.

Geographic distribution of COVID cases requiring hospitalization in two major hospitals of Milan (IRCCS)

Possible bias

The six areas analyzed have similar economic characteristics, healthcare standards and COVID-19 surveillance data collection procedures, which allowed us to make a reliable comparison of data. The choice of these areas followed administrative borders and the availability of the disaggregated mortality data. If only focusing on the metropolitan area of Milan (3.2 million inhabitants), mortality rates would have been about 45% lower (data not shown); if a wider area including only the provinces surrounding Milan (Monza, Bergamo and Lodi) had been evaluated (area of 5.5 million inhabitants), the mortality rate would have been comparable to the regional data (data not shown).

Our analysis considered daily COVID-19 mortality rates derived by national surveillance statistics, which are more reliable than infection notifications (confirmed cases). Indeed, notified cases data are largely lower compared to the reality, and highly variable depending on different swab strategies and criteria adopted in different regions (52). Although it cannot be ruled out that a portion of the deaths caused by COVID-19 went undiagnosed, we believe that this possible bias, estimated at 17% (53), is similar in the other five areas (as suggested by international press reports) thereby it doesn’t greatly affect the final assertion of our comparative study.

Conclusions

We analyzed the COVID-19 epidemic trend in six areas, comparable from an economic, social and healthcare perspective, using reliable indicators, such as the cause of death. New York City (8.4mln. inh.) and Madrid (6.6mln. inh.) are the two metropolitan areas mostly affected by the epidemic, while the Lombardy region (10mln. inh.) – the first western area affected by the epidemic and, in theory, less prepared – recorded a high number of deaths (over 10,000) but a mortality rate lower than three out of the six regions considered, and a cumulative mortality rate on the 30th day about 50% lower than New York City and the Community of Madrid. One of the reasons contributing to these results, as mentioned earlier, could be that the epidemic has not yet hit the metropolitan area of Milan (3.2mln. inh.), but only smaller cities including Bergamo (1mil. inh.). Two factors could have contributed to the positive “defense” to the metropolitan area with the higher population density and commercial trades: firstly, the efficacy and the promptness (54) of containment and mitigation measures which resulted in increasing physical distancing and then in a reduction people gatherings ; secondly the effectiveness and safety of care provided by hospitals treating COVID-19 cases (47,48) (considering that hospitals were an important driving force of the transmission of this epidemic worldwide).

An additional refers to the general increase of hospital beds and intensive care beds that was achieved in a short time in all the examined areas, which allowed to face the emergency. In particular, the Lombardy Region (as also done by the Community of Madrid and Ile-de-France) more than doubled the number of beds, both ordinary hospital beds and for intensive care.

Finally, the two countries with a public healthcare system (Italy and UK), which recorded mortality rates below the average, arranged formal agreements with the private healthcare system. This aspect might have given an important contribution to the management of the emergency. Although emergency treatments were provided in all considered areas with the same models (apparently free of charge) in all six areas, the fact that the two countries with a public healthcare system achieved lower mortality rates could be due to the hospital system efficacy combined with the activity of territorial services. In conclusion, we can state that a “Lombardy case” did not occur in terms of a specific mortality excess; moreover, the rapid adaptation of the hospital network has been able to cope with a massive epidemic wave managing, to date, to limit its spread in the area with the highest population density.

A more complete analysis can be carried out for a longer follow up (45 or 60 days since the onset of the epidemic) in which it will be possible to better analyze, for all the six areas considered (and possibly others), the medium-term effect of the containment measures, the actions of primary health care, the ignition of further epidemic outbreaks and the overall management of the epidemic.

Conflict of interest:

Each author declares that he or she has no commercial associations (e.g. consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangement etc.) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article

Funding:

This paper is a preliminary activity among the EU Project n. 101003562 “Three Rapid Diagnostic tests (Point-of-Care) for COVID-19 Coronavirus, improving epidemic preparedness, and foster public health and socio-economic benefits - CORONADX” (Task 7.1) supported by the Europeam Commission (Horizon 2020, H2020-SC1-PHE-CORONAVIRUS-2020).

References

- 1.Boerner L, Severgnini B. Il commercio è alleato dei virus, lo dice la storia. 2020 https://www.lavoce.info/archives/64259/lo-dice-la-storia-il-commercio-e-alleato-dei-virus/ . Accessed 13 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization COVID-19 weekly surveillance report. 2020 http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/health-emergencies/coronavirus-covid-19/weekly-surveillance-report , 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sebastiani G. Il coronavirus ha viaggiato in autostrada? 2020 https://www.scienzainrete.it/articolo/coronavirus-ha-viaggiato-autostrada/giovanni-sebastiani/2020-04-09 . Accessed 13 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gatto M, Bertuzzo E, Mari L, et al. Spread dynamics of the covid-19 epidemic in Italy: effects of emergency containment measures. PNAS. 2020 doi: 10.1073/pnas.2004978117. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prem K, Liu Y, Russell TW, et al. The effect of control strategies to reduce social mixing on outcomes of the COVID-19 epidemic in Wuhan, China: a modelling study. Lancet Public Health. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30073-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilder-Smith A, Chiew CJ, Lee VJ. Can we contain the COVID-19 outbreak with the same measures as for SARS? Lancet Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30129-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kraemer MUG, Yang CH, Gutierrez B, et al. The effect of human mobility and control measures on the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Science. 2020 doi: 10.1126/science.abb4218. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Signorelli C, Scognamiglio T, Odone A. COVID-19 in Italy: impact of containment measures and prevalence estimates of infection in the general population. Acta Biomed. 2020;91(3-S):175–179. doi: 10.23750/abm.v91i3-S.9511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tang B, Wang X, Li Q, et al. Estimation of the Transmission Risk of the 2019-nCoV and Its Implication for Public Health Interventions. J Clin Med. 2020;9(2) doi: 10.3390/jcm9020462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mayor S. Covid-19: Researchers launch app to track spread of symptoms in the UK. BMJ. 2020;368:m1263. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gianfredi V, Odone A, Fiacchini D, Rosselli R, Battista T, Signorelli C. Trust and reputation management, branding, social media management nelle organizzazioni sanitarie: sfide e opportunità per la comunità igienistica italiana. J Prev Med Hyg. 2019;60(3):E108–E109. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gianfredi V, Grisci C, Nucci D, Parisi V, Moretti M. [Communication in health.] Recenti Prog Med. 2018;109(7):374–383. doi: 10.1701/2955.29706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gan WH, Lim JW, Koh D. Preventing intra-hospital infection and transmission of COVID-19 in healthcare workers. Saf Health Work. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.shaw.2020.03.001. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lau JT, Fung KS, Wong TW, et al. SARS transmission among hospital workers in Hong Kong. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10(2):280–286. doi: 10.3201/eid1002.030534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.European Centre for Disease prevention and Control . Stockholm; 25 March 2020. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: increased transmission in the EU/EEA and the UK – seventh update. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cereda D, Tirani M, Rovida F, et al. The early phase of the COVID-19 outbreak in Lombardy, Italy. Arvix. 2020 in press. [Google Scholar]

- 17.UCSC Coronavirus, le stime dei ricercatori: “In Italia almeno 2800 morti non dichiarati”. 2020 https://www.lastampa.it/topnews/primo-piano/2020/03/30/news/le-stime-dei-ricercatori-almeno-2800-morti-non-dichiarati-1.38653880 . Accessed 13 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 18.United States Census Explore Census Data. 2020 https://data.census.gov/cedsci/ . Accessed 13 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 19.United States Census . New York: New York County (Manhattan Borough); 2020. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/newyorkcountymanhattanboroughnewyork . Accessed 13 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 20.United States Census Commuter-Adjusted Population Estimates: ACS 2006-10. 2010 https://www.census.gov/library/working-papers/2010/demo/mckenzie-01.html . Accessed 13 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 21.New York State Department of Health Hospitals by Region/County and Service. 2020 https://profiles.health.ny.gov/hospital/county_or_region/region:new+york+metro+-+new+york+city . Accessed 13 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Melby C, Gu J, Rojanasakul M. Mapping New York City Hospital Beds as Coronavirus Cases Surge. 2020 https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/2020-new-york-coronavirus-outbreak-how-many-hospital-beds/ . Accessed 13 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 23.New York State Department of Health Hospitals by Region/County and Service. 2020 https://profiles.health.ny.gov/hospital/county_or_region/region:new+york+metro+-+new+york+city . [Google Scholar]

- 24.The City Coronavirus in New York City. 2020 https://projects.thecity.nyc/2020_03_covid-19-tracker/ . Accessed 13 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 25.NYC Health COVID-19: Data. 2020 https://www1.nyc.gov/site/doh/covid/covid-19-data.page . Accessed 15 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 26.European Commission Population: Demographic situation, languages and religions. 2019 https://eacea.ec.europa.eu/national-policies/eurydice/content/population-demographic-situation-languages-and-religions-7_en . Accessed 13 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 27.City population Bruxelles Municipality. 2019 https://www.citypopulation.de/en/belgium/bruxelles/_/21004__bruxelles/ . Accessed 13 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brussels Institute for Statistics and Analysis Key figures for the Brussels-Capital Region. 2017 http://statistics.brussels/figures/key-figures-for-the-region#.XpScEcgzZPZ . Accessed 13 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Federal Public Service The geographical distribution of accredited hospital beds. 2020 https://www.healthybelgium.be/en/key-data-in-healthcare/general-hospitals/organisation-of-the-hospital-landscape/categorisation-of-hospital-activities/the-geographical-distribution-of-accredited-hospital-beds . Accessed 13 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sciensano COVID-19 - Situation épidémiologique. 2020 https://epistat.wiv-isp.be/covid/ . Accessed 15 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Portal del Ayuntamiento de Madrid Portal web del Ayuntamiento de Madrid. 2019 https://www.madrid.es/portal/site/munimadrid# . Accessed 13 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Instituto Nacional de Estadistica Demografía y población. 2019 https://www.ine.es/ . Accessed 13 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Instituto Nacional de Estadistica Atlas de la movilidad residencia-trabajo en Comunidad de Madrid 2017. 2017 https://www.madrid.org/iestadis/fijas/estructu/general/territorio/atlasmovilidad2017/02_caract_gnral.html . Accessed 13 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ministerio de Sanidad de España Situación de COVID-19 en España. 2020 https://covid19.isciii.es/ . Accessed 13 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ministerio de Sanidad de España Situación de COVID-19 en España. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Institut National de la statistique et des études éeconomiques The National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies collects, analyses and disseminates information on the French economy and society. 2019 https://www.insee.fr/en/accueil . Accessed 13 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Institut National de la statistique et des études éeconomiques The National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies collects, analyses and disseminates information on the French economy and society. 2019 https://www.insee.fr/en/accueil . [Google Scholar]

- 38.Institut National de la statistique et des études éeconomiques Les mobilités dans le Bassin parisien à trois âges de la vie : faire ses études, aller travailler, prendre sa retraite. 2019 https://www.insee.fr/fr/statistiques/4258068?sommaire=4258113 . Accessed 13 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ministère des Solidarités et de la Santé Nombre de lits de réanimation, de soins intensifs et de soins continus en France, fin 2013 et 2018. 2020 Accessed 13 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Agence régional de santé Ile-de-France (Siège) Coronavirus (Covid-19) : La lutte contre l’épidémie en Île-de-France. 2020 https://www.iledefrance.ars.sante.fr/coronavirus-covid-19-lars-ile-de-france-mobilisee . Accessed 13 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gouvernement France COVID-19 en France. 2020 https://www.gouvernement.fr/info-coronavirus/carte-et-donnees . Accessed 13 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 42.World Population Review London Population 2020. 2020 https://worldpopulationreview.com/world-cities/london-population/ . Accessed 15 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 43.NHS England Bed Availability and Occupancy Data – Overnight. 2020 https://www.england.nhs.uk/statistics/statistical-work-areas/bed-availability-and-occupancy/bed-data-overnight/ . Accessed 15 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Financial Times NHS enlists all English private hospitals to treat coronaviru. 2020 https://www.ft.com/content/c9a9be78-6b7b-11ea-89df-41bea055720b . Accessed 15 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 45.NHS England New NHS nightingale hospital to fight coronavirus. 2020 https://www.england.nhs.uk/2020/03/new-nhs-nightingale-hospital-to-fight-coronavirus/ . Accessed 15 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 46.NHS England COVID-19 Daily Deaths. 2020 https://www.england.nhs.uk/statistics/statistical-work-areas/covid-19-daily-deaths/ . Accessed 15 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Istituto Nazionale di Statistica (ISTAT) Popolazione residente al 1° gennaio. 2019 http://dati.istat.it/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=DCIS_POPRES1 . Accessed 13 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Odone A, Delmonte D, Scognamiglio T, Signorelli C. COVID-19 deaths in Lombardy. Lancet Public Health. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30099-2. published April 24, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dipartimento della Protezione Civile COVID-19 Italia-Monitoraggio della situazione. 2020 http://www.protezionecivile.gov.it/attivita-rischi/rischio-sanitario/emergenze/coronavirus . Accessed 15 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ministero della Salute Covid-19 - Situazione in Italia. 2020 http://www.salute.gov.it/portale/nuovocoronavirus/dettaglioContenutiNuovoCoronavirus.jsp?area=nuovoCoronavirus&id=5351&lingua=italiano&menu=vuoto . Accessed 13 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Emilia-Romagna Region Epidemia COVID-19. Aggiornamento del 17 aprile 2020 sui dati del giorno precedente. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 52.Romanò L, Pariani E, Biganzoli E, Castaldi S. The end of lockdown what next ? Acta Biomedica. 2020;91(2) doi: 10.23750/abm.v91i2.9605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rajgor DD, Lee MH, Archuleta S, Bagdasarian N, Quek SC. The many estimates of the COVID-19 case fatality rate. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30244-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gianfredi V, Balzarini F, Gola M, et al. Leadership in Public Health: Opportunities for Young Generations Within Scientific Associations and the Experience of the “Academy of Young Leaders”. Front Public Health. 2019;7:378. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2019.00378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]