Abstract

Background.

The beginning of 2020 has been marked by a historic event of worldwide importance: the Coronavirus pandemic. This emergency has resulted in severe global problems affecting areas such as healthcare and the social and economic fields. What about crime?

Purpose of the work.

The purpose of this work is to reflect about Italy and its crime rate at the time of Coronavirus.

Methods.

Some crimes will be analysed (the “conventional” ones only, ruling out health-related offences) in the light of data resulting from Ministries and Europol reports, as well as from newspapers and news.

Results and conclusions.

The outcome will be explained, and some criminological remarks will be added. (www.actabiomedica.it)

Keywords: COVID-19, pandemic, crime rate, Italy

Background and aim of the work

Since the 21st of February, Italy has been facing the fight against the pandemic caused by SARS-CoV-2.

It is not up to us provide health and epidemiological data, which are continuously evolving. What we will focus on is the fact that we are tackling an event of overall social impact, which results in social distancing as the main strategy to follow and to apply. Social distancing means restricting people and their freedom to move as well as the closure of a large number of shops and businesses, as requested by the latest Italian Law Decrees and provisions. These restrictions have had, and are still having, while we are writing this paper, a great impact both on our lives and on those of criminals.

Aim and methods of the work

The purpose of this work is to reflect on the great impact caused by social distancing, by using government statistical data, Europol reports, information from the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime Agency, newspapers and news, in order to highlight how some crimes are changing during this pandemic.

Results

Nothing is more dynamic than crime, able to rapidly adapt to the changes of society, while trying to take advantage of them (1). In other words, delinquency seems to follow the economic and social growth of modern societies, replicating their mechanisms (2).

With regard to the data published so far, according to the Ministry of Interior, the overall number of crimes committed in Italy has dropped significantly in March (3).

The conventional crimes against property have decreased (we will focus on less conventional crimes like fraud attempts on the Internet later in this paper).

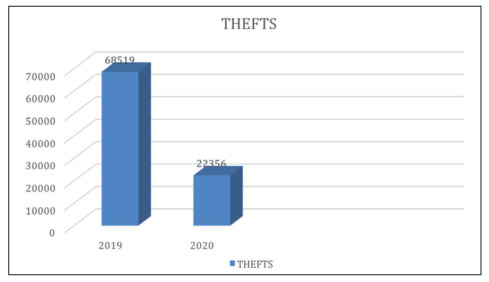

Thefts have shifted from 68.519 to 22.356, an overall reduction of 67,4%. Stealing is undoubtedly more difficult, when people are forced to stay at home all the time; purse snatching has become difficult too, since there are less people moving around and those who are, are bound to keep at least one meter distance from each other.

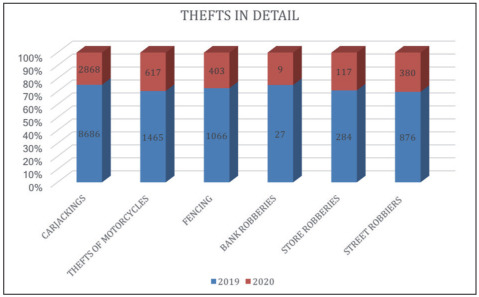

Carjacking and thefts of motorcycles have decreased as well (carjacking: from 8.686 to 2.868; thefts of motorcycles from 1.465 to 617): this is probably due to the constant presence of police patrols on the streets.

Logically, the receipt of stolen goods has dropped too (from 1.066 to 403).

The same may be said for robberies: bank robberies have decreased from 27 to 9 cases; store robberies from 284 to 117 and street robberies from 876 to 380.

These data are not surprising if we consider the Rational Choice Theory that Baker applied to criminology (4). In this historical period, committing crimes against property is not convenient. There are certainly more risks than economic advantages. Situational prevention experts state the same: a criminal choice also includes the analysis of the environment and is focused on the crime setting which is currently unfavorable because of increased controls, both formal and informal (5).

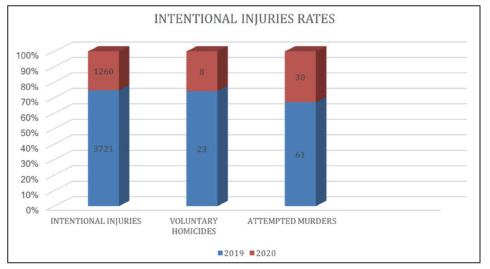

Intentional injuries as well show a downward trend (from 3.721 to 1.260). If the lockdown is reducing the number of young adult gatherings on one side, it also reduces the potential conflicts facilitated by alcohol or drugs (6), on the other.

Voluntary homicides have dropped too, shifting from 23 to 8, while attempted murders have shifted from 61 to 30. We should bear in mind that homicide rates have been decreasing in general (except the domestic murders (7)), but a 65% reduction is nevertheless meaningful.

This may result from the lockdown, but also from a ceasefire between criminal organisations, which are ready to benefit from this adverse economic framework, while avoiding as much as possible to attract the police’s attention. Future data will supply us with some responses to our assumptions.

Finally, the reduction of 77% of the exploitation of prostitution rate is not surprising either: it concerns a crime based on the possibility for people to move and whose frequency the fear of contagion has certainly lowered.

The crimes concerning the supply of illegal drugs have experienced a reduction as well (of 42%). Complaints for drug dealing have decreased from 1.801 to 1.030 (March 2020): our assumption is that the lockdown has helped reduce the movement of drugs too.

The Italian situation is likely very similar to that of other countries dealing with Coronavirus.

According to a report by the Marshall Project (8), some American cities are experiencing a remarkable reduction of crime. In San Francisco, for example, the overall reduction equals 42%, with a decrease of robberies of 60% since the beginning of the lockdown. In Los Angeles, thefts have dropped by 15%, robberies by 22%. Since these data refer to March (before the lockdown got stricter), this decrease is expected to be even more significant from now on (9).

Figure 1.

Figure 2.

Figure 3.

The same may be said for Great Britain where predatory crimes have dropped by 20% since the beginning of the limitations. This rate too will probably increase since the lockdown (10) is expected to continue.

The Global Initiative Against Transnational Crime Report (11), published in March 2020, reported news relating to other countries, that could indicate how our reality will transform in the future.

According to this report, since police and policymakers are currently focused on more urgent matters, some criminal groups may identify new objectives and modalities to operate in the realm of illegal markets, such as drug production and trafficking. As reported by the news, in some countries criminal networks have been capitalizing on the disruption caused by the pandemic.

Moreover, organized-crime groups, which have been embedded in the healthcare sector for a long time, have quickly identified opportunities to exploit the sector; cybercrime is rapidly becoming a risk that could have long-term implications for the growth of criminal markets.

Authorities in Iran, Ukraine and Azerbaijan have intercepted some attempts to smuggle essential stocks of medical face masks and hand sanitizers. In Italy, the police have seized counterfeit face masks in several regions of our country. Advertisements for face masks can be found on Dark Web forums and on hundreds of sites on the open web.

According to the INTERPOL-coordinated Operation Pangea of March 2020, authorities from 90 countries have been taking collective actions against the illicit online sale of medicines and medical products, resulting in 121 arrests worldwide and in the seizure of potentially dangerous pharmaceuticals worth more than $14 million.

INTERPOL has issued a warning against frauds, in order to prevent people from being tricked into buying non-existent medical supplies, while making payments to accounts controlled by criminals. It is estimated that millions of dollars have already been lost by the victims of such frauds. Again, an investigation carried out in Italy in 2018 revealed that ambulances controlled by the ‘Ndrangheta were riddled with inadequacies, including defective gearboxes, broken brakes and lights, and that they lacked crucial equipment.

Good news is that, due to the lockdown, a long-hunted mafia boss – Cesare Cordi of the ‘Ndrangheta – was arrested by the Italian police for contravening lockdown restrictions.

This report concludes that cybercrime and internet-related crimes offer an enormous potential for criminal groups of any size and scale, as a way to replace the income lost from their traditional criminal activities.

Considerations

According to the data just analysed, Coronavirus has undoubtedly led to a reduction in the number of voluntary crimes. This is quite positive.

Nevertheless, the following considerations are due.

The data about crimes refer to reported cases and, as it is well known in criminology, reflect just a part of the overall criminality that often remains unrevealed.

We are referring to that dark number that mainly concerns predatory crimes, the ones that are currently decreasing (12).

We can assume that, at present, people are reluctant to report offences, because this would mean they did not respect the restrictions. If not necessary for insurance purposes, complaints can be postponed.

There are, however, other types of offences which need to be considered such as crimes against family.

Literature shows how difficult it is for a victim to report those crimes. The real risk is to make things worse and increase the perpetrator’s rage (13).

This type of crime may not currently be decreasing and the cases, which are not being reported, may surface after the pandemic. This, however, is just a simple assumption, to be verified with data as soon as the lockdown will be reduced.

Usury is another sector that may cause concerns. The data provided by our Minister of the Interior show a shift from 9 to 11 cases during March 2020. Statistically, these numbers are not so significant, but they still represent a bad indicator. Due to the economic crisis, criminal infiltrations in production and commercial activities may be facilitated.

The economic crisis of 2008 showed the concrete risk for companies and business owners to collapse and that people owning a great amount of money, which might have been collected illegally (14), benefitted from the precarious situation.

As highlighted in the recent Europol report, the greatest area of concern is that of cybercrimes (15).

According to Italian data, complaints about cybercrimes are decreasing by 66% (from 985 to 389 reports).

However, victims of this type of crime, are not immediately aware of the cyber-attack, but tend to realize the damage much later.

The most worrying are cyber-attacks targeting healthcare facilities and critical infrastructures.

What happened in the Czech Republic is emblematic. The Brno University Hospital was hit by a cyberattack on the 12th and 13th of March, causing an immediate computer shutdown (Europol report).

Another report issued by the Global Initiative Against Transnational Crime emphasized that healthcare facilities are not only at risk of cyber-attacks, but also of criminal infiltrations and increasing corruption (16).

The number of frauds against vulnerable people is growing as well. This type of crime is carried out with different methods. At present, the sectors of pharmaceutical and hygienic products are the ones to focus on.

According to Europol, during the pandemic, goods for 13 million euros and 44 million products have been seized (counterfeited or non-compliant products), 123 people have been arrested, and 2.500 e-commerce sites have been shut down. This long-studied form of crime seems to be a new challenge in the fight against Coronavirus (17).

We conclude with a brief overview on the increasing so-called “online hate speeches”.

Some people who are angry and frustrated because of this pandemic have expressed their feelings online, through racist comments against people or countries they consider to be the real cause of this worldwide emergency. Hate speeches are not something new in criminology (18), but this attitude is apparently increasing and worsening, if one considers that we are experiencing a situation which should rather call for a greater collective solidarity.

In addition, some speeches posted on Facebook made by mayors, councillors and Presidents of the Region are marked by violent words addressing, in this case, anyone violating the lockdown (19).

A very last comment concerns crimes strictly associated with Coronavirus, such as people contravening the lockdown measures, especially those who have been quarantined because they tested positive.

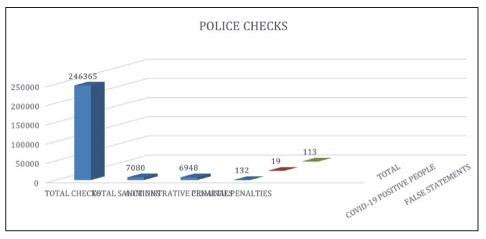

On April 1st, 2020, according to ministerial data, 246.365 people were stopped by the police all over the national territory. The police issued 7.080 sanctions (20). Most of the sanctions were administrative, while 132 were criminal penalties, out of which 19 were issued to people who tested positive for Coronavirus and were breaking the quarantine; 113 citizens made false statements.

These are significant numbers, which may likely increase by the time this lockdown is over. This means that we might face an actual legal “post Coronavirus”.

People who tested positive for Coronavirus should be asked why they decided to break the quarantine, in order to understand the criminogenesis.

The reasons for violating restrictions may be different. Is it about ignoring the risk? Is it a conscious choice of people who have nothing to lose? What about the lack of responsibility towards others? Does the choice result from a general confusion about the legislation (Anomie Theory (21)) or just from missing “collective empathy”?

It is hard to give an answer right now, since the analysis of individual cases is currently poor and insufficient, but the lack of responsibility towards others, if confirmed, would indicate the absence of individual and social empathy.

Conclusions

One of the criticisms pointed out by epidemiologists and virologists about the reliability of the data related to the spread of the Coronavirus, is that it would be better not to comment on daily numbers. This holds for criminology too: one month is not enough to speak about significant statistical trends.

Figure 4.

This being said, conventional crimes as of March 2020, are indeed decreasing, which is good.

The bad news is that new types of crime, such as cybercrimes, are arising. But there are also criminals benefitting from the Covid-19 emergency, taking advantage from the fear and the needs of the citizens. These types of crimes are particularly hateful and lead to a double victimisation.

Moreover, crime is rapidly adapting to the current situation.

Conflict of interest:

Each author declares that he or she has no commercial associations (e.g. consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangement etc.) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article

References

- 1.Travaini G, Viggiani C. Cyber Crime: un futuro di maggiori rischi, ma anche di maggiori protezioni. Supplemento Harvard Business Review Italia. 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 2. http://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/criminalita-organizzata_%28Enciclopedia-del-Novecento%29/ [Google Scholar]

- 3. http://www.interno.gov.it/it/notizie/emergenza-coronavirus-ridotti-spostamenti-netto-calo-i-reati . [Google Scholar]

- 4.Becker G. Crime and Punishment: An Economic Approach 1974: 1-54 in, Essays in the Economics of Crime and Punishment, National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clarke R.V. Situational Crime Prevention: Successful Case Studies (second edition), Ronald V. Clarke Editor, 1997; Cornish D. B, Clarke R. V. G. The reasoning criminal: Rational choice perspectives on offending. New York: Springer-Verlag, 1986; Lombardi M, Giuntarelli P, Veraldi R. Sociologia dello spazio, dell’ambiente e del territorio; Milano: Franco Angeli, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gatti U, Soellner R, Schadee H.M.A, Verde A, Rocca G. Rocca G, Verde A, Schadee H.M.A, Gatti U. Effects of delinquency on alcoholuse among juveniles in Europe: Results from the ISRD-Study. Eur J. Crim Policy Rev. 2013;19:153–170. (2014) Uso di alcol, delinquenza e vittimizzazione tra i giovani in Europa: analisi preliminare dei risultati di una ricerca multicentrica internazionale (ISRD-2) 2014; Rassegna Italiana di Criminologia; 1: 18-29) [Google Scholar]

- 7.Merzagora I, Battistini A, Caruso P, Mottale N, Pleuteri L, Travaini G. Mariticide in Milan between 1990 and 2017: A criminological and medico-legal analysis. Medico-Legal Journal. 2019;87 doi: 10.1177/0025817219866113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. https://www.themarshallproject.org/2020/03/27/as-coronavirus-surges-crime-declines-in-some-cities . [Google Scholar]

- 9. https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2020-03-27/coronavirus-crime-lapd-reports-drop-march . [Google Scholar]

- 10. https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2020/mar/26/coronavirus-crisis-leads-to-precipitous-drop-in-recorded . [Google Scholar]

- 11. https://globalinitiative.net/initiatives/covid-crime-watch/ [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doorewaard C, Vettori B, Barbagli M, Colombo A, Savona E. The Dark Figure Of Crime And Its Impact On The Criminal Justice System. Le statistiche sulla criminalità in ambito internazionale, europeo e nazionale. Fonti e tecniche di analisi con SPSS; Milano LED Edizioni Universitarie. Sociologia della devianza. 2014, 2010, 2003 Bologna, Il Mulino, Bologna. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Travaini G, Caruso P, Beringheli E, Merzagora I. Criminological Treatment of Abusing Partners; in Balloni A, Sette R. Handbook of Research on trends and Issues in Crime Prevention Regabilitation and victim support; USA, IGI Global. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Blasio G, Menon C, Merzagora I, Mugellini G, Amadasi A, Travaini G. Down and out in Italian Towns: measuring the impact of economic downturns on crime. Suicide Risk and the Economic Crisis: An Exploratory Analysis of the Case of Milan. Banca d’Italia Paper. Plos One. 2013, 2016;11(12):925. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0166244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. https://www.europol.europa.eu/publications-documents/pandemic-profiteering-how-criminals-exploit-covid-19-crisis . [Google Scholar]

- 16. https://globalinitiative.net/initiatives/covid-crime-watch/ [Google Scholar]

- 17.Di Nicola A, Martini E, Baratto G, Antonopoulos G, Boriero D, Da Col W, Zabyelina Y. Fakecare. Developing expertise against the online trade of fake medicines by producing and disseminating knowledge, counterstrategies and tools across the E.U; 2015; eCrime, University of Trento. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Travaini G, Caruso P, Merzagora I. The north stand amnesics. sentiment analysis of an anti-semitic episode occured during an italian football match | [Gli smemorati della curva nord. sentiment analysis di un episodio antisemita in ambito calcistico]; Rassegna Italiana di Criminologia. 2019;3 [Google Scholar]

- 19. https://www.milanotoday.it/attualita/coronavirus/sindaco-linda-colombo-facebook.html . [Google Scholar]

- 20. http://www.rainews.it/dl/rainews/articoli/Coronavirus-controlli-Viminale-e7ba222d-e3bd-4548-8dc9-b6d23100db5d.html . [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ponti G, Merzagora I. Compendio di Criminologia; Milano, Cortina Editore, 2008. [Google Scholar]