Abstract

Objectives

Individuals with obesity especially excessive visceral adiposity have high risk for incident hypertension. Recently, a new algorithm named relative fat mass (RFM) was introduced to define obesity. Our aim was to investigate whether it can predict hypertension in Chinese population and to compare its predictive power with traditional indices including body mass index (BMI), waist circumference (WC) and waist-to-height ratio (WHtR).

Design

A 6-year prospective study.

Setting

Nine provinces (Hei Long Jiang, Liao Ning, Jiang Su, Shan Dong, He Nan, Hu Bei, Hu Nan, Guang Xi and Gui Zhou) in China.

Participants

Those without hypertension in 2009 survey and respond in 2015 survey.

Intervention

Logistic regression were performed to investigate the association between RFM and incident hypertension. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was performed to compare the predictive ability of these indices and define their optimal cut-off values.

Main outcome measures

Incident hypertension in 2015.

Results

The prevalence of incident hypertension in 2015 based on RFM quartiles were 14.8%, 21.2%, 26.8% and 35.2%, respectively (p for trend <0.001). In overall population, the OR for the highest quartile compared with the lowest quartile for RFM was 2.032 (1.567–2.634) in the fully adjusted model. In ROC analysis, RFM and WHtR had the highest area under the curve (AUC) value in both sexes but did not show statistical significance when compared with AUC value of BMI and WC in men and AUC value of WC in women. The performance of the prediction model based on RFM was comparable to that of BMI, WC or WHtR.

Conclusions

RFM can be a powerful indictor for predicting incident hypertension in Chinese population, but it does not show superiority over BMI, WC and WHtR in predictive power.

Keywords: hypertension, diabetes & endocrinology, public health, nutrition, epidemiology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Our study was the first study to reveal whether the newly invented RFM algorithm can independently predict incident hypertension in Chinese population and compare its predicting power with traditional obesity-related indices.

We used a nationally representative sample and a prospective design to investigate the predictive power of RFM for incident hypertension.

Physical examinations and biomarker measurements were only carried out atbaseline and the follow-up recordings were lacking in this study.

We can’t validate and evaluate the performance of the RFM algorithm in estimating body fat percentage in our study population, which hinders the further interpretation of our results.

Introduction

During the last three decades, hypertension has been the leading cause for all-cause deaths worldwide.1 An international survey indicated that the incident rate of hypertension was 40.8% in their multinational study population.2 In China, 23.2% of adult population had hypertension and another 41.3% were in a prehypertension state; however, only 46.9% were aware of the diagnosis and minority were effectively controlled in those who were diagnosed.3 Statistics present the grim reality; there is no doubt that blood pressure-related morbidity and mortality will exert a huge burden. Thus, despite improvement in hypertension diagnosis and treatment, implementing effective measures to identify people at risk and prevent the incident of hypertension is extremely important.

Obesity is a significant risk factor for hypertension; various studies in different ethnic groups have shown this association.4 For example, the Framingham heart indicated that 34% of hypertension in men and 62% of hypertension in women can be ascribed to overweight and obesity.5 However, weight loss intervention can significantly lower the blood pressure and serve as an effective method for the primary prevention of hypertension.6 7 Currently, when considering the deleterious effect of obesity, excessive intra-abdominal or visceral adipose tissue rather than subcutaneous fat were regarded as the main cause for hypertension and other cardiometabolic abnormalities.8–11 Thus, a proper assessment of excessive adiposity (defined as the body fat percentage ≥25% in men and ≥35% in women according to the Western Pacific Regional Office and global WHO reference standards12)) especially central adiposity can effectively identify those at high risk for hypertension.

Body fat mass can be quantified with MRI, CT and dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA). However, due to the high cost and limited availability, they are not ideal for large-scale epidemiological screening. In this context, anthropometric indices are widely used to assess body fatness and identifying individuals at risk of cardiometabolic diseases. Currently, there is no consensus about the best anthropometric index in predicting hypertension. Traditional indices such as body mass index (BMI), waist circumference (WC) and waist-to-height ratio (WHtR) have been applied to assessing the risk of incident hypertension in Chinese population by several studies, and most of them revealed WHtR showed better performance when compared with BMI or WC.13–16 Moreover, another six adiposity measures including conicity index, lipid accumulation product (LAP), visceral adipose index, a body shape index and the body adiposity index were also used to evaluate the hypertension risk; however, only LAP showed superiority when compared with traditional indices17–20; despite this, the equations of these indexes are relatively complex with numerous terms needed. Recently, a simple new algorithm named relative fat mass (RFM) had been introduced by Woolcott et al21 to estimate whole-body fat percentage among adult individuals; they proved it was highly correlated with abdominal obesity and can better predict whole-body fat percentage than BMI, which was validated by DXA. Moreover, the main component of RFM equation is height-to-waist ratio, which is the converse form of WHtR. Thus, RFM shows great potential in cardiometabolic or hypertension risk assessment. In this study, we performed a 6-year prospective study by using data from the China Health and Nutrition Survey, attempting to investigate whether RFM could be a better anthropometric index for hypertension risk prediction in Chinese population and contribute to the prevention of hypertension.

Method

Study subjects

The China Health and Nutrition Survey (CHNS) is an ongoing open cohort aiming at examining the health and nutritional condition and its influencing factors of the participants. To date, 10 rounds of survey (1989, 1991, 1993, 1997, 2000, 2004, 2006, 2009, 2011 and 2015) have been conducted. It was colaunched by Carolina Population Center at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the National Institute for Nutrition and Health at the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. All participants signed an informed consent form during the survey. The cohort profile provides detailed information on this survey.22

Appropriate sample size was calculated using the OpenEpi software program (http://www.openepi.com/SampleSize/SSCohort.htm) before initiating the study. Considering 5% level of significance for a two-sided test, 80% power, unexposed/exposed ratio of 1.3, percent of unexposed with outcome=15 and percent of exposed with outcome=33 according to the results from the China hypertension survey,9 the estimated sample size required was at least 198 subjects.

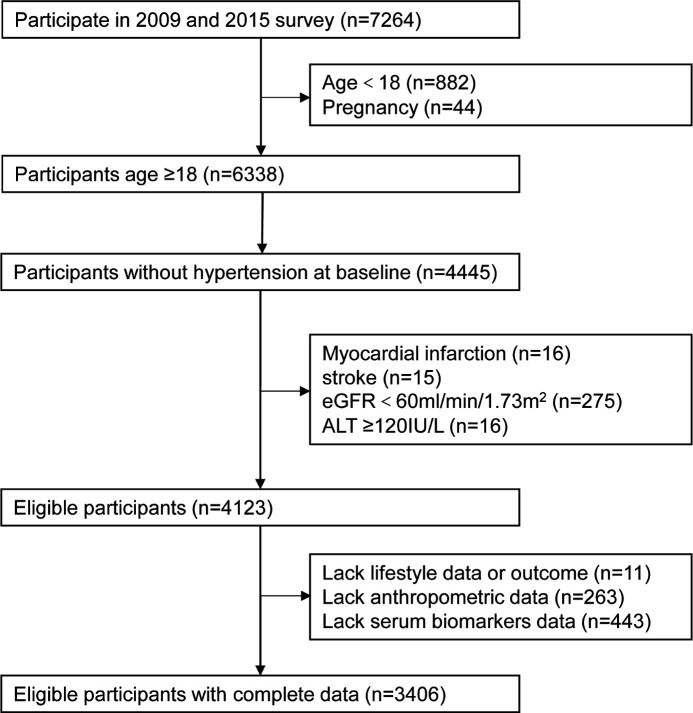

In this study, we conducted a prospective study among people aged more than 18 years by using the data form the 2009 and 2015 CHNS survey. Subjects who participated in both the 2009 and 2015 survey were enrolled in this study, those who did not have hypertension in 2009 were set as baseline sample and the presence of incident hypertension in 2015 was defined as the outcome. First, we excluded subjects aged less than 18 years or pregnancy and those who were hypertensive at baseline. Then, those who had history of myocardial infarction or stroke, chronic kidney disease (estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR)<60 mL/min/1.73 m2), serve hepatic dysfunction (alanine aminotransfease (ALT) ≥120 IU/L) were excluded. Last, subjects who lack data about smoking, drinking, outcome and anthropometric measurement were excluded. Meanwhile, those who have missing data on biomarkers (n=443) were also excluded. Finally, 3406 participants were included in our study (figure 1); thus, the sample of this study was sufficient. Compared with those who were included in the study, those who were excluded owing to missing data were slightly younger, and there was a slightly higher percentage of males; there were no statistically significant differences between the two groups in BMI, WC and biochemical parameters at baseline and in the incidence of hypertension at the final follow-up.

Figure 1.

The flow chart of sample selection from the China Health and Nutrition Survey.

Data collection

Characteristics of the participants including general personal characteristics, smoking status, alcohol consumption and medical history were obtained by using face-to-face interview. Current smoker was defined as positive answers to the question ‘Have you ever smoke? Are you still smoking?’. Alcohol consumer was defined as positive answers to ‘In the past year, have you ever drunk beer, liquor or wine? How often do you consume alcohol?’. Each individual’s height and weight were measured by the investigators according to the standard of protocol; height was measured without shoes to the nearest 0.1 cm using a portable stadiometer; body weight was measured with subjects wearing light clothing without shoes to the nearest 0.1 kg on a calibrated digital scale; BMI was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in metres. When measuring WC, the tape was applied horizontally midway between the lower rib margin and the iliac crest. WHtR was WC in centimetres divided by height in centimetres. RFM was calculated by using the following formula23:

Blood pressure was determined in duplicate to improve accuracy, and the average of the values was reported as the final results. For blood collection, participants were asked to fast for 6–8 hours. Blood was collected in EDTA-3K anticoagulant tube, then centrifuged at 3000 g for 15 min to separate plasma from blood cells. Plasma samples were stored in cryovial at −70°C condition, and whole blood samples were stored at 2–8°C condition. Whole blood was used for testing of glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) by chromatography. Plasma was tested for ALT, triglycerides (TGs), total cholesterol (TC), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), uric acid, creatinine (Cr) and insulin by using automated biochemistry analyser. ALT was tested by high-performance liquid chromatography method. HDL-C and LDL-C were determined by enzymatic method. TGs were determined by CHOD-PAP method, and TC was determined by GPO-PAP method. Uric acid was determined by enzymatic colorimetric method. Glucose was determined by GOD-PAP method. Insulin was determined by radioimmunology method. Estimated glomerular filtration rate was calculated by using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation.24

Definitions

Hypertension was defined as systolic blood pressure ≥140 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mm Hg, or subjects who have been reported diagnosed or treated with antihypertensive drugs. Diabetes was defined as previously diagnosed with diabetes or fasting blood glucose ≥7.0 mmol/L or HbA1c ≥6.5%. Hyperuricaemia means serum uric acid 420 μmol/L in men and>360 μmol/L in women. Dyslipidaemia was defined as the presence of any of the following lipid alterations: TG ≥1.70 mmol/L or TC ≥5.18 mmol/L or HDL-C <1.04 mmol/L or LDL-C ≥3.37 mmol/L.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables with a non-normal distribution were expressed as median (IQR), and categorical variables were expressed as percentages. Differences between groups were tested by Mann-Whitney U test for variables with skewed distributions and χ2-test for categorical variables. Logistic regression analysis was conducted to examine the association of RFM and incident hypertension. RFM was stratified into four quartiles according to sex-specific cut-point, OR and its 95% CI and was estimated by four models: (A) crude model; (B) adjusted for age and sex; (C) adjusted for age, sex, smoking and alcohol drinking; (D) additionally adjusted for uric acid, eGFR, ALT, TG, TC, HDL-C, LDL-C and fasting plasma glucose (FPG). Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analyses were conducted to compare the predictive power of RFM with traditional indices including BMI, WC and WHtR. In ROC analysis, we defined the appropriate cut-off point of each anthropometric index for the prediction of incident hypertension, by using these indices as test variable and hypertension in 2015 as state variable; the optimal cut-off values were determined by the maximising the Youden index. ROC analysis was also used to evaluate the performance of different models in predicting incident hypertension. The areas under the ROC curve of different indices were compared using the method developed by DeLong et al.25 Analyses were performed using SPSS V.19.0 and MedCalc V.18.2.1. Two-tailed p values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Patient and public involvement

There were no patients or public involved in study design, outcome measurement and results interpretation.

Results

Baseline characteristics of participants

There were 3406 eligible participants without hypertension at baseline. Baseline characteristics are shown in table 1. After 6 years of follow-up, 834 individuals developed hypertension. The incidence was 26.5% for men and 22.8% for women. As expected, those who developed hypertension showed a more adverse profile on cardiometabolic parameters—higher uric acid, ALT, FPG, TG, TC and LDL-C level and lower eGFR level.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of participates according to follow-up outcomes

| Incident hypertention | P value | ||

| No (n=2572) | Yes (n=834) | ||

| Age | 45.0 (37.0–54.0) | 52.0 (44.0–59.0) | <0.001 |

| Men/women | 1144/1428 | 413/421 | 0.012 |

| Alcohol consumer (%) | 32.9 | 38.8 | 0.002 |

| Smoking (%) | 0.303 | ||

| Current smoker | 28.7 | 30.6 | |

| Ex smoker | 2.0 | 2.6 | |

| Non-smoker | 69.3 | 66.8 | |

| Body weight (kg) | 57.7 (52.0–65.2) | 61.0 (54.3–68.9) | <0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.37 (20.50–24.58) | 23.80 (21.51–26.07) | <0.001 |

| WC (cm) | 80.0 (73.0–86.7) | 84.0 (77.9–90.0) | <0.001 |

| WHtR | 0.50 (0.46–0.54) | 0.52 (0.48–0.56) | <0.001 |

| RFM | 30.18 (23.75–36.70) | 30.83 (24.69–38.62) | <0.001 |

| SBP (mm Hg) | 116.0 (108.0–121.3) | 120.7 (114.9–128.7) | <0.001 |

| DBP (mm Hg) | 76.7 (70.0–80.0) | 80.0 (75.3–82.0) | <0.001 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 83.2 (74.7–93.2) | 80.4 (72.1–89.7) | <0.001 |

| Cr (μmol/L) | 82.0 (74.0–93.0) | 83.0 (75.0–93.0) | 0.394 |

| Uric acid (μmol/L) | 276.0 (225.0–338.8) | 290.0 (234.0–353.0) | 0.001 |

| ALT (U/L) | 18.0 (13.0–25.0) | 19.0 (14.0–28.0) | <0.001 |

| FPG (mmol/L) | 5.00 (4.63–5.45) | 5.15 (4.76–5.64) | <0.001 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 1.13 (0.78–1.73) | 1.31 (0.90–1.92) | <0.001 |

| TC (mmol/L) | 4.63 (4.05–5.27) | 4.87 (4.23–5.51) | <0.001 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.40 (1.18–1.64) | 1.40 (1.16–1.64) | 0.804 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 2.78 (2.26–3.38) | 2.98 (2.42–3.57) | <0.001 |

Categorical variables were presented as a number (percentage), continuous variables with a skewed distribution were presented as median (IQR). P values are for Mann-Whitney U test for or χ2 test.

ALT, alamine aminotransferase; BMI, body mass index; Cr, creatinine; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; RFM, relative fat mass; SBP, systolic blood pressure; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglyceride; WC, waist circumference; WHtR, waist-to-height ratio.

Baseline characteristics of the participants according to RFM quartiles are shown in table 2. The prevalence of cardiometabolic risk factors such as hyperuricaemia, dyslipidaemia and diabetes were increased in proportion to the quartiles of RFM.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of participates according to RFM

| Quartile 1 | Quartile 2 | Quartile 3 | Quartile 4 | P value | |

| n=853 | n=851 | n=853 | n=849 | ||

| Age | 41.0 (32.0–50.0) | 45.0 (38.0–54.0) | 49.0 (41.0–57.0) | 51.0 (42.0–58.0) | <0.001 |

| Men/women | 391/462 | 388/463 | 389/464 | 389/460 | 0.999 |

| Alcohol consumer (%) | 30.5 | 34.9 | 35.9 | 36.3 | 0.045 |

| Current smoker (%) | 29.5 | 29.3 | 29.1 | 28.9 | 0.301 |

| Body weight (kg) | 52.5 (47.8–57.6) | 57.0 (51.7–63.1) | 60.6 (55.0–67.3) | 66.4 (59.1–74.4) | <0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 19.96 (18.71–21.21) | 21.99 (20.84–23.25) | 23.63 (22.09–24.92) | 26.13 (24.12–27.75) | <0.001 |

| WC (cm) | 70.0 (67.0–73.0) | 78.0 (75.0–80.0) | 84.0 (81.0–87.0) | 92.0 (88.5–96.5) | <0.001 |

| WHtR | 0.44 (0.42–0.45) | 0.48 (0.47–0.49) | 0.52 (0.51–0.53) | 0.57 (0.56–0.60) | <0.001 |

| SBP (mm Hg) | 110.7(102.8–120.0) | 117.3 (110.0–122.0) | 120.0 (110.0–125.3) | 120.0 (112.0–126.7) | <0.001 |

| DBP (mm Hg) | 73.3 (69.3–80.0) | 77.3 (70.0–80.7) | 79.3 (71.3–81.0) | 80.0 (73.3–82.0) | <0.001 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 86.5(76.5–96.2) | 81.9 (74.5–92.4) | 81.4 (73.3–90.6) | 80.7 (72.2–89.7) | <0.001 |

| Cr (μmol/L) | 83.0 (74.5–93.0) | 83.0 (75.0–93.0) | 82.0 (75.0–93.0) | 83.0 (74.0–93.0) | 0.914 |

| Uric acid (μmol/L) | 265.0 (219.0–324.0) | 275.0 (222.0–333.0) | 279.0 (230.0–338.0) | 303.0(244.5–372.0) | <0.001 |

| ALT (U/L) | 15.0 (11.0–22.0) | 17.0 (12.0–24.0) | 19.0 (14.0–26.0) | 22.0 (16.0–32.0) | <0.001 |

| FPG (mmol/L) | 4.89 (4.53–5.27) | 4.95 (4.62–5.38) | 5.07 (4.67–5.53) | 5.22 (4.84–5.76) | <0.001 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 0.94 (0.68–1.28) | 1.11 (0.77–1.65) | 1.25 (0.85–1.92) | 1.49 (1.03–2.46) | <0.001 |

| TC (mmol/L) | 4.40 (3.85–4.96) | 4.64 (4.10–5.34) | 4.79 (4.17–5.40) | 4.91 (4.30–5.57) | <0.001 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.47 (1.28–1.72) | 1.45 (1.22–1.69) | 1.39 (1.15–1.61) | 1.28 (1.09–1.50) | <0.001 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 2.58 (2.11–3.14) | 2.83 (2.29–3.43) | 2.91 (2.39–3.50) | 3.00 (2.47–3.61) | <0.001 |

| Hyperuricaemia (%) | 5.3 | 9.8 | 12.0 | 17.2 | <0.001* |

| Dyslipidaemia (%) | 32.5 | 49.2 | 57.6 | 69.4 | <0.001* |

| Diabetes (%) | 2.8 | 5.1 | 6.8 | 13.0 | <0.001* |

Categorical variables were presented as a number (percentage), and continuous variables with a skewed distribution were presented as medians (IQR). P values are for Kruskal-Wallis test or χ2 test.

*P values for linear trend across quartiles (linear tendency χ2 test).

ALT, alamine aminotransferase; BMI, body mass index; Cr, creatinine; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; RFM, relative fat mass; SBP, systolic blood pressure; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglyceride; WC, waist circumference; WHtR, waist-to-height ratio.

Association between RFM and incident hypertension

Table 3 shows the incidence of hypertension according to quartiles of RFM. Participants with high levels of RFM at baseline were more likely to develop hypertension during follow up, as incident cases of hypertension increased as the RFM increased (14.8%, 21.2%, 26.8% and 35.2% in the first, second, third and fourth quartiles, respectively). In unadjusted logistic regression models, compared with the first quartile of RFM levels, the ORs and 95% CI for incident hypertension in the second, the third and the fourth quartiles were 1.548 (1.205 to 1.989), 2.117 (1.662 to 2.698) and 3.137 (2.478 to 3.971), respectively (p for trend <0.001). After adjusted for age and sex (model 1) and age, sex, smoking and alcohol drinking (model 2), the associations remained significant. In the fully adjusted model considering additional potential confounders including uric acid, eGFR, ALT, TG, TC, HDL-C, LDL-C and FPG (model 3), the ORs and 95% CI for incident hypertension comparing the second, third and fourth quartiles to the first quartile of RFM levels were 1.266 (0.977 to 1.640), 1.513 (1.172 to 1.953) and 2.032 (1.567 to 2.634), respectively (p for trend <0.001).

Table 3.

ORs and 95% CIs for incident hypertension according to baseline quartiles of RFM

| Quartile 1 (n=853) |

Quartile 2 (n=851) |

Quartile 3 (n=853) |

Quartile 4 (n=849) |

P for trend | |

| Incident hypertention | 126 | 180 | 229 | 299 | <0.001 |

| Unadjusted | 1 | 1.548 (1.205 to 1.989) | 2.117 (1.662 to 2.698) | 3.137 (2.478 to 3.971) | <0.001 |

| Model 1 | 1 | 1.337 (1.035 to 1.728) | 1.662 (1.295 to 2.133) | 2.360 (1.849 to 3.013) | <0.001 |

| Model 2 | 1 | 1.320 (1.021 to 1.707) | 1.633 (1.272 to 2.098) | 2.321 (1.817 to 2.966) | <0.001 |

| Model 3 | 1 | 1.266 (0.977 to 1.640) | 1.513 (1.172 to 1.953) | 2.032 (1.567 to 2.634) | <0.001 |

Quartiles of RFM for men: first quartile ≤20.0, second quartile=20.1–23.4, third quartile=23.5–26.3 and fourth quartile ≥26.4.

Quartiles of RFM for women: first quartile ≤33.1, second quartile=33.2–36.7, third quartile=36.8–39.8 and fourth quartile ≥39.9.

Model 1: adjusted for age and sex.

Model 2: adjusted for age, sex, smoking and alcohol drinking.

Model 3: adjusted for age, sex, smoking, alcohol drinking, uric acid, eGFR, ALT, TG, TC, HDL-C, LDL-C and FPG.

ALT, alamine aminotransferase; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; HDL-C, high-densitylipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; RFM, relative fat mass; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglyceride.

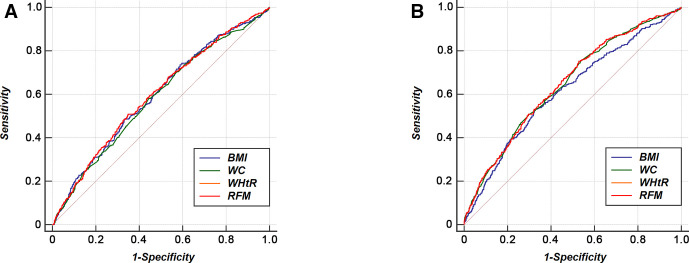

ROC curves for the incidence of hypertension

In logistic regression analysis, we demonstrated RFM can independently predict the onset of hypertension. Aiming at comparing its predictive power with traditional anthropometric indices and delineating their optimal cut-points, an ROC analysis was conducted (figure 2). In men, there were no significant differences in area under the curve (AUC) value of RFM as compared with that of WC and BMI (Bonferroni-adjusted p value >0.05). In women, RFM had higher AUC value than that of BMI (Bonferroni-adjusted p value=0.047) and comparable value to that of WC (Bonferroni-adjusted p value >0.05). In both sexes, there were no significant differences in AUC value of BMI as compared with that of WC (Bonferroni-adjusted p value >0.05). All indices had higher AUC value in women than in men (table 4).

Figure 2.

Receiver operating characteristic curves of BMI, WC, WHtR and RFM for incident hypertension. BMI, body mass index; RFM, relative fat mass; WC, waist circumference; WHtR, waist-to-height ratio.

Table 4.

AUCs for each anthropometric index in predicting hypertension

| Men | Women | |||

| AUC (95% CI) | P value | AUC (95% CI) | P value | |

| RFM | 0.597 (0.572 to 0.621) | <0.001 | 0.647 (0.625 to 0.669) | <0.001 |

| BMI | 0.593 (0.568 to 0.618) | <0.001 | 0.615 (0.592 to 0.637) | <0.001 |

| WC | 0.583 (0.558 to 0.608) | <0.001 | 0.644 (0.622 to 0.666) | <0.001 |

| WHtR | 0.597 (0.572 to 0.621) | <0.001 | 0.647 (0.625 to 0.669) | <0.001 |

AUC, area under the curve; BMI, body mass index; RFM, relative fat mass; WC, waist circumference; WHtR, waist-to-height ratio.

In male population, the optimal cut-off value was 24.67 for RFM, 23.74 for BMI, 82.95 for WC and 0.51 for WHtR. In female population, the optimal cut-off value was 35.73 for RFM, 23.83 for BMI, 77.15 for WC and 0.50 for WHtR. In both sexes, RFM and WHtR had the highest Youden index values for predicting hypertension (table 5).

Table 5.

Optimal cut-off points for each anthropometric index in predicting hypertension

| Men | Women | |||||||

| Cut-off | Sensitivity (%) | Specifity (%) | Youden index | Cut-off | Sensitivity (%) | Specifity (%) | Youden index | |

| RFM | 24.67 | 0.51 | 0.65 | 0.16 | 35.73 | 0.75 | 0.47 | 0.22 |

| BMI | 23.74 | 0.48 | 0.67 | 0.15 | 23.83 | 0.53 | 0.67 | 0.20 |

| WC | 82.95 | 0.58 | 0.56 | 0.14 | 77.15 | 0.76 | 0.46 | 0.22 |

| WHtR | 0.51 | 0.51 | 0.65 | 0.16 | 0.50 | 0.75 | 0.47 | 0.22 |

BMI, body mass index; RFM, relative fat mass; WC, waist circumference; WHtR, waist-to-height ratio.

Moreover, AUC was calculated for the regression models. The effect of each index of obesity plus other risk factors including age, smoking, alcohol drinking, uric acid, eGFR, ALT, TG, TC, HDL-C, LDL-C and FPG in predicting hypertension were evaluated. For both male and female population, there were no statistical differences among the AUC values of the four models when compared in a pairwise manner (all Bonferroni-adjusted p value >0.05) (table 6).

Table 6.

Performance of different models in predicting incident hypertension

| Men | Women | |||

| AUC (95% CI) | P value | AUC (95% CI) | P value | |

| RFM+other factors | 0.660 (0.636 to 0.684) | <0.001 | 0.697 (0.676 to 0.718) | <0.001 |

| BMI+other factors | 0.667 (0.643 to 0.690) | <0.001 | 0.702 (0.680 to 0.723) | <0.001 |

| WC+other factors | 0.660 (0.636 to 0.684) | <0.001 | 0.704 (0.683 to 0.725) | <0.001 |

| WHtR+other factors | 0.661 (0.637 to 0.685) | <0.001 | 0.698 (0.677 to 0.719) | <0.001 |

Other factors including age, smoking, alcohol drinking, uric acid, eGFR, ALT, TG, TC, HDL-C, LDL-C and FPG.

AUC, area under the curve; BMI, body mass index; RFM, relative fat mass figure legends; WC, waist circumference; WHtR, waist-to-height ratio.

Discussion

In our longitudinal study performed in initially non-hypersensitive individuals with 6 years of follow-up, we found an increased risk of incident hypertension across quartiles of RFM after adjusted for several known risk factors, which indicate RFM is an independent and practicable predictor of hypertension in Chinese population.

When considering obesity and hypertension, visceral adiposity mediates the progression from a normotensive to hypertensive. The most definitive evidence of this comes from the Dallas Heart Study, they measured adipose tissue through MRI scanner and demonstrated visceral adiposity but not total or subcutaneous adiposity was significantly associated with incident hypertension.26 Excessive abdominal adiposity can result in adipocyte dysfunction, which was accompanied by abnormal proinflammatory cytokines and adipocytokines secretion and increased concentration of circulating free fatty acids. These factors can contribute to vascular dysfunction and systemic insulin resistance, and then leading to increased activation of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system and increased sympathetic nervous system activity.27 Moreover, obesity can cause kidney injury. The compression of the kidneys by fat can induce inflammation and expansion of renal medullary extracellular matrix, inhibit renal tubular reabsorption and increase sodium reabsorption, leading to the development of low eGFR and further increases in blood pressure.28 Thus, indices that can give a precise assessment of fat mass especially visceral adiposity may improve the sensitivity and specificity in detecting individuals with increased cardiometabolic or hypertension risk.

The aim of developing the RFM algorithm was to better reflect estimates of whole-body fat percentage in clinical and epidemiological practice; it was proved to have higher sensitivity and lower rates of misclassification in obesity estimation when compared with BMI in US population by its developers and had been proved to be better than BMI in Mexican population.23 29 In predicting cardiometabolic risk, RFM also showed excellent performance. RFM had better discrimination power than BMI in identifying diabetes (AUC: 0.80 vs 0.76 for men and AUC: 0.79 vs 0.73 for women).23 In a cohort study, RFM was better than BMI in predicting incident severe liver disease and overall mortality.30 However, in our study performed in Chinese population, although we found RFM can be an effectively index in predicting hypertension, it was comparable with BMI in men and slightly better than BMI in women in predicting ability. Two reasons can account for this result. First, the outcome in our study was different from other current published cross-sectional or cohort study about RFM, although obesity participate and serve as critical role in the pathophysiological processes of all these outcome diseases, the confounding factors may be different from each other. Second, according to a recent study performed in Korean population, RFM tend to overestimated the body fat percentage in their study population and showed a better linear relationship with body fat percentage than BMI in men only. In ROC analysis, they found RFM was not superior to that of BMI in discriminating obese individuals.31 RFM was developed from Mexican-Americans, European-Americans and African-Americans. Meanwhile, Asian populations tend to have higher body fat percentage than Caucasians at the same BMI level.32Thus, the efficiency of the RFM algorithm for estimating body fat percentage in Chinese population is unknown and needs further validation study.

RFM and WHtR had the same AUC value in the ROC analysis. The optimal cut-off of WHtR in our study were 0.51 for men and 0.50 for women, similar to the recommendations suggested by various studies to define central obesity (WHtR>0.5); meanwhile, 0.5 had been demonstrated to be a good boundary value for men and women across ethnic groups in assessing diabetes and CVD risk.33–35 When the WHtR value was 0.5, the corresponding value for RFM were 24 for men and 36 for women, very close to the optimal cut-off of RFM in our study. Based on these, we can conclude that a high level of consistency existed between the current RFM equation and WHtR, and RFM can be an alternative to WHtR in predicting incident hypertension.

Overall, in our study, the ROC analysis of the single index in predicting incident hypertension revealed that WC or WHtR did not show significant superiority over BMI. Meanwhile, the AUCs calculated for the regression models in table 6 further demonstrated this. Indeed, as BMI does not distinguish fat mass from lean mass and does not reflect fat distribution,36 37 WC and index based on WC may give a better quantity of visceral fat. However, same as our study, some studies reported that no difference between BMI and WC/WHtR with regard to discriminating or predicting hypertension,38–42 and some reported BMI showed a better performance,43 44 which should be explained. Aside from the different methodology (such as ROC analysis, Cox regression and logistic regression) used to judge the performance, study design (cross-sectional and longitudinal) and covariates taken into consideration, we think two additional factors may explain the inconsistency between studies. First, the morphological characteristics of the study participants may account for this. In many circumstances especially in Asian populations, BMI and WC are highly correlated, there were studies reported that their ability were comparable in predicting abdominal adipose tissues,45 the high collinearity between BMI and WC-based indices may result in similar predictive power. Second, different inclusion criteria were applied in these studies, some included those with organ dysfunction such as myocardial infarction, heart failure and chronic kidney diseases. These diseases may lead to changes in haemodynamic load and total fluid volume that mediate the presence of hypertension, while BMI is sensitive to these changes and thus can provide information more than adiposity.

Our study has several strengths. First, our study was performed using nationally representative samples of the Chinese adult population, which were recruited from nine different provinces in China. Second, to our best knowledge, we were the first longitudinal study to investigate whether the current RFM algorithm can be applied in hypertension prediction in Chinese population and compare its predicting power with traditional obesity-related indices. Third, in baseline population, we excluded the individuals with history of myocardial infarction or stroke, as well as those with chronic kidney disease or liver dysfunction, which may affect the association between obesity and hypertension. This ensure the objectivity and accuracy of our research.

There are also limitations of our study. First, we exclude 717 individuals from this study due to lack of data about the factors we needed in statistical analysis, which may cause selection bias. Second, medical history taking, physical examinations and biomarker measurements were only carried out at the baseline, but these parameters may change over time. For example, lifestyle intervention and pharmacotherapy can result in weight loss and ameliorate metabolic disorders in some high-risk individuals and reduce the risk of developing hypertension. However, we failed to take these factors into consideration in our study. Third, although the blood pressure was measured in duplicate, white-coat hypertension may exist and affected our judgement of the outcome. Fourth, as the nature of observational study, when investigating about the association between RFM and incident hypertension, it is possible that some unknown or unmeasured factors confounded the association; however, in our logistic analysis, we had adjusted the main confounding factors; we do not think residual confounding will materially alter our conclusion. Fifth, as the participants in our study did not undergo DXA test or other tests that can give an assessment about body component, we could not evaluate the performance and accuracy of the RFM algorithm in Chinese population; this hinder the further interpretation of our results.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study revealed that RFM is a powerful indicator to predict incident hypertension in Chinese population; the optimal cut-off of RFM was 24.67 and 35.73 for men and women, respectively; individuals above the cut-off level show higher risk for hypertension and deserve early intervention to prevent it. However, based on the AUC values in ROC analysis, RFM did not show better performance compared with traditional obesity indices.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research used data from the China Health and Nutrition Survey (CHNS) website. We would like to thank the National Institute of Nutrition and Food Safety, China Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Carolina Population Center, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, the NIH and the Fogarty International Center; we would also like to thank the teams from China-Japan Friendship Hospital, Ministry of Health, Chinese National Human Genome Center and Beijing Municipal Center for Disease Prevention and Control, as they launched or supported the CHNS survey and provided the data we used in this study.

Footnotes

Contributors: PY and XY contributed to the study conception and study design. PY, XY, TH and SH contributed to the data analysis and interpretation of the data. PY contributed to drafting the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This research was funded by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81570740) and National Key R&D Program of China (2016YFC0901203).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The survey was approved by the Institutional Review Committees of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, the National Institute of Nutrition and Food Safety and Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. All participants had signed the informed consent forms during the CHNS survey.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: All datasets generated for this study are included in the article.

References

- 1.GBD 2017 Risk Factor Collaborators Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 84 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet 2018;392:1923–94. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32225-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chow CK, Teo KK, Rangarajan S, et al. Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in rural and urban communities in high-, middle-, and low-income countries. JAMA 2013;310:959–68. 10.1001/jama.2013.184182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang Z, Chen Z, Zhang L, et al. Status of hypertension in China: results from the China hypertension survey, 2012-2015. Circulation 2018;137:2344–56. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.032380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lavie CJ, De Schutter A, Parto P, et al. Obesity and prevalence of cardiovascular diseases and Prognosis-The obesity paradox updated. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2016;58:537–47. 10.1016/j.pcad.2016.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilson PWF, D'Agostino RB, Sullivan L, et al. Overweight and obesity as determinants of cardiovascular risk: the Framingham experience. Arch Intern Med 2002;162:1867–72. 10.1001/archinte.162.16.1867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stevens VJ, Obarzanek E, Cook NR, et al. Long-Term weight loss and changes in blood pressure: results of the trials of hypertension prevention, phase II. Ann Intern Med 2001;134:1–11. 10.7326/0003-4819-134-1-200101020-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ma C, Avenell A, Bolland M, et al. Effects of weight loss interventions for adults who are obese on mortality, cardiovascular disease, and cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2017;359:j4849. 10.1136/bmj.j4849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hayashi T, Boyko EJ, Leonetti DL, et al. Visceral adiposity is an independent predictor of incident hypertension in Japanese Americans. Ann Intern Med 2004;140:992–1000. 10.7326/0003-4819-140-12-200406150-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hayashi T, Boyko EJ, McNeely MJ, et al. Visceral adiposity, not abdominal subcutaneous fat area, is associated with an increase in future insulin resistance in Japanese Americans. Diabetes 2008;57:1269–75. 10.2337/db07-1378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sullivan CA, Kahn SE, Fujimoto WY, et al. Change in intra-abdominal fat predicts the risk of hypertension in Japanese Americans. Hypertension 2015;66:134–40. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.04990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karlsson T, Rask-Andersen M, Pan G, et al. Contribution of genetics to visceral adiposity and its relation to cardiovascular and metabolic disease. Nat Med 2019;25:1390–5. 10.1038/s41591-019-0563-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Physical status: the use and interpretation of anthropometry. Report of a who expert Committee. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser 1995;854:1–452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cai L, Liu A, Zhang Y, et al. Waist-to-height ratio and cardiovascular risk factors among Chinese adults in Beijing. PLoS One 2013;8:e69298. 10.1371/journal.pone.0069298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dong J, Ni Y-Q, Chu X, et al. Association between the abdominal obesity anthropometric indicators and metabolic disorders in a Chinese population. Public Health 2016;131:3–10. 10.1016/j.puhe.2015.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Savva SC, Lamnisos D, Kafatos AG. Predicting cardiometabolic risk: waist-to-height ratio or BMI. A meta-analysis. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes 2013;6:403–19. 10.2147/DMSO.S34220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deng G, Yin L, Liu W, et al. Associations of anthropometric adiposity indexes with hypertension risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis including PURE-China. Medicine 2018;97:e13262. 10.1097/MD.0000000000013262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen X, Liu Y, Sun X, et al. Comparison of body mass index, waist circumference, conicity index, and waist-to-height ratio for predicting incidence of hypertension: the rural Chinese cohort study. J Hum Hypertens 2018;32:228–35. 10.1038/s41371-018-0033-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Song J, Zhao Y, Nie S, et al. The effect of lipid accumulation product and its interaction with other factors on hypertension risk in Chinese Han population: a cross-sectional study. PLoS One 2018;13:e0198105. 10.1371/journal.pone.0198105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hu L, Hu G, Huang X, et al. Different adiposity indices and their associations with hypertension among Chinese population from Jiangxi Province. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2020;20:115. 10.1186/s12872-020-01388-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tong Y, Han E. Associations between body shape, body adiposity and other indices: a case study of hypertension in Chinese children and adolescents. Ann Hum Biol 2019;46:460–6. 10.1080/03014460.2019.1688864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Woolcott OO, Bergman RN. Relative fat mass (RFM) as a new estimator of whole-body fat percentage ─ a cross-sectional study in American adult individuals. Sci Rep 2018;8:10980. 10.1038/s41598-018-29362-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Popkin BM, Du S, Zhai F, et al. Cohort Profile: The China Health and Nutrition Survey--monitoring and understanding socio-economic and health change in China, 1989-2011. Int J Epidemiol 2010;39:1435–40. 10.1093/ije/dyp322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Woolcott OO, Bergman RN, mass Rfat. Relative fat mass (RFM) as a new estimator of whole-body fat percentage ─ a cross-sectional study in American adult individuals. Sci Rep 2018;8:10980–80. 10.1038/s41598-018-29362-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 2009;150:604–12. 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.DeLong ER, DeLong DM, Clarke-Pearson DL. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonparametric approach. Biometrics 1988;44:837–45. 10.2307/2531595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chandra A, Neeland IJ, Berry JD, et al. The relationship of body mass and fat distribution with incident hypertension: observations from the Dallas heart study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;64:997–1002. 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.05.057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.DeMarco VG, Aroor AR, Sowers JR. The pathophysiology of hypertension in patients with obesity. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2014;10:364–76. 10.1038/nrendo.2014.44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hall JE, do Carmo JM, da Silva AA, et al. Obesity-Induced hypertension: interaction of neurohumoral and renal mechanisms. Circ Res 2015;116:991–1006. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.305697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guzmán-León AE, Velarde AG, Vidal-Salas M, et al. External validation of the relative fat mass (RFM) index in adults from north-west Mexico using different reference methods. PLoS One 2019;14:e0226767. 10.1371/journal.pone.0226767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Machado MV, Policarpo S, Coutinho J, et al. What is the role of the new index relative fat mass (RFM) in the assessment of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)? Obes Surg 2020;30:560–8. 10.1007/s11695-019-04213-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paek JK, Kim J, Kim K, et al. Usefulness of relative fat mass in estimating body adiposity in Korean adult population. Endocr J 2019;66:723–9. 10.1507/endocrj.EJ19-0064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Deurenberg P, Deurenberg-Yap M, Guricci S. Asians are different from Caucasians and from each other in their body mass index/body fat per cent relationship. Obes Rev 2002;3:141–6. 10.1046/j.1467-789X.2002.00065.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zeng Q, He Y, Dong S, et al. Optimal cut-off values of BMI, waist circumference and waist:height ratio for defining obesity in Chinese adults. Br J Nutr 2014;112:1735–44. 10.1017/S0007114514002657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ashwell M, Gibson S. Waist to height ratio is a simple and effective obesity screening tool for cardiovascular risk factors: analysis of data from the British National diet and nutrition survey of adults aged 19-64 years. Obes Facts 2009;2:97–103. 10.1159/000203363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Browning LM, Hsieh SD, Ashwell M. A systematic review of waist-to-height ratio as a screening tool for the prediction of cardiovascular disease and diabetes: 0·5 could be a suitable global boundary value. Nutr Res Rev 2010;23:247–69. 10.1017/S0954422410000144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nevill AM, Stewart AD, Olds T, et al. Relationship between adiposity and body size reveals limitations of BMI. Am J Phys Anthropol 2006;129:151–6. 10.1002/ajpa.20262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gómez-Ambrosi J, Silva C, Galofré JC, et al. Body mass index classification misses subjects with increased cardiometabolic risk factors related to elevated adiposity. Int J Obes 2012;36:286–94. 10.1038/ijo.2011.100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38., Nyamdorj R, Qiao Q, et al. , Decoda Study Group . Bmi compared with central obesity indicators in relation to diabetes and hypertension in Asians. Obesity 2008;16:1622–35. 10.1038/oby.2008.73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de Oliveira CM, Ulbrich AZ, Neves FS, et al. Association between anthropometric indicators of adiposity and hypertension in a Brazilian population: Baependi heart study. PLoS One 2017;12:e0185225. 10.1371/journal.pone.0185225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grootveld LR, Van Valkengoed IGM, Peters RJG, et al. The role of body weight, fat distribution and weight change in ethnic differences in the 9-year incidence of hypertension. J Hypertens 2014;32:990–7. 10.1097/HJH.0000000000000135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nyamdorj R, Qiao Q, Söderberg S, et al. Comparison of body mass index with waist circumference, waist-to-hip ratio, and waist-to-stature ratio as a predictor of hypertension incidence in Mauritius. J Hypertens 2008;26:866–70. 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3282f624b7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rezende AC, Souza LG, Jardim TV, et al. Is waist-to-height ratio the best predictive indicator of hypertension incidence? a cohort study. BMC Public Health 2018;18:281. 10.1186/s12889-018-5177-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li Y, Liu Y, He J, et al. The association of wrist circumference with hypertension in northeastern Chinese residents in comparison with other anthropometric obesity indices. PeerJ 2019;7:e7599. 10.7717/peerj.7599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lam BCC, Koh GCH, Chen C, et al. Comparison of body mass index (BMI), body adiposity index (BAI), waist circumference (wc), Waist-To-Hip ratio (WHR) and Waist-To-Height ratio (WHtR) as predictors of cardiovascular disease risk factors in an adult population in Singapore. PLoS One 2015;10:e0122985. 10.1371/journal.pone.0122985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Oka R, Miura K, Sakurai M, et al. Comparison of waist circumference with body mass index for predicting abdominal adipose tissue. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2009;83:100–5. 10.1016/j.diabres.2008.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.