Abstract

Purpose

The Finnish National Esophago-Gastric Cancer Cohort (FINEGO) was established with the aim of identifying factors that could contribute to improved outcomes in oesophago-gastric cancer. The aim of this study is to describe the patients with gastric cancer included in FINEGO.

Participants

A total of 10 457 patients with gastric cancer or tumour diagnosis in the Finnish Cancer Registry or the Finnish Patient Registry during 1987–2016 were included in the cohort, with follow-up from Causes of Death Registry until 31 December 2016. All of the participants were at least 18 years of age, and had undergone either resectional or endoscopic mucosal surgery with curative or palliative intent.

Findings to date

Of the 10 457 patients, 90.1% were identified to have cancer in both cancer and patient registries. In all, the median age was 70 at the time of surgery, 54.5% of the patients were men and 64.4% had no comorbidities. Education data were available for 31.1% of the patients, of whom the majority had had <12 years of formal education. Of the 7798 with cancer staging data available, 41.1% had a local cancer. Adenocarcinoma was the most common (94.2%) histological type. Almost all patients underwent open gastrectomy and 214% in hospitals with annual volume of more than 30 gastrectomies per year. A total of 8561 deaths occurred during the study period, of which 6474 were due to oesophago-gastric cancers. The 5-year survival was 34.6% and 5-year cancer-specific survival was 39.7%.

Future plans

The data in FINEGO can be currently used for registry-based research but is being expanded by data extraction from patient records and scanning of histological samples from the Finnish biobanks. Initially, we are planning on studies on the national trends in treatment and mortality, and studies on the demographic factors and their influence on survival.

Keywords: surgery, gastrointestinal tumours, gastroenterology, adult oncology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The main strength of the study is the population-based design with complete and accurate ascertainment of all patients diagnosed with gastric cancer in Finland, counteracting selection bias.

The follow-up of participants is complete.

The main limitations are the exclusion of patients not undergoing surgery and registry information lag of up to 2 years.

Some registry-based variables, such as laparoscopic surgery or neoadjuvant therapy are of questionable quality and should be interpreted cautiously before validation studies.

The dataset will be complemented with patient records and histological slides collection to allow a wide variety of research questions.

Introduction

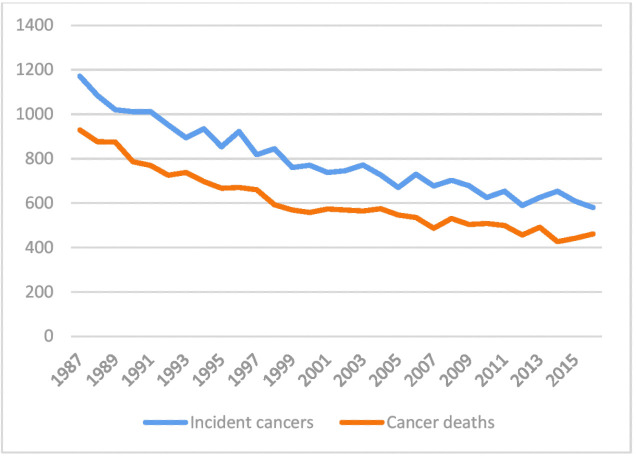

Gastric cancer is the third leading cause of cancer death worldwide.1 Gastric cancer incidence is slowly decreasing,2 also in Finland (figure 1),3 but the incident cancers are often diagnosed at a late stage.4 The dominant histological type is adenocarcinoma, and only less than 5% of all gastric cancers represent other histological types.5 The standard treatment of gastric cancer is surgery, in certain stages accompanied by neoadjuvant or perioperative therapy.4 6 Even after curative surgery, gastric cancers have poor survival.4 7

Figure 1.

The number of incident gastric cancers and gastric cancer deaths, according to the Finnish Cancer Registry.3

However, there are many unclear topics and gaps of knowledge in the treatment of gastric cancer, such as whether high hospital or surgeon volumes, or oncological treatment improve gastric cancer survival,8 whether certain anastomotic techniques are associated with less postoperative complications,9 10 and whether Siewert II gastric cardia cancer should be resected by oesophagectomy or gastrectomy,11 to name a few. The population-based nationwide cohort would be the ideal study design to evaluate these questions,12 as randomised controls would be either unfeasible, or would need to include a very large amount of patients.

The Finnish registry data are known to be of high quality with high completeness.13 To facilitate surgical research with appropriate in-depth clinical variables, we started a national collaborative with the aim to create a population-based cohort on gastric cancer in Finland with extensive data collection from the nationwide registries and patient records. The collaborative and the cohort was named The Finnish National Esophago-Gastric Cancer Cohort (FINEGO).14

In this cohort profile, we describe the registry data on 10 457 patients with gastric cancer included in FINEGO. Patients with oesophageal cancer are described in a separate study.

Cohort description

FINEGO is a population-based, nationwide, retrospective cohort study of all surgically treated patients with oesophageal and gastric cancer in Finland since 1987. Senior surgeons, oncologists, pathologists and statisticians are involved in the collaborative group, representing the six Finnish hospitals and the related universities actively participating in surgical treatment and research of oesophago-gastric cancer.

The inclusion criteria of the study were:

Age at least 18 years at the time of cancer diagnosis.

Primary cancer of epithelial origin in the oesophagus, cardia or stomach.

Surgical treatment given for cancer, including all types of surgery or endoscopic resection.

However, as there is a possibility of misclassification in the registries, the data collection was somewhat broader. All cancers of any origin were included during the registry data collection to avoid excluding misclassified patients. Furthermore, patients with unclear tumour diagnoses undergoing surgical resection were also included to reduce selection bias. All patients without surgical treatment were excluded from the cohort.

For this manuscript, only gastric cancers are included.

Data sources

The data were collected from the Finnish Cancer Registry, Finnish Patient Registry and Statistics Finland. The immutable, 11-digit personal identification number assigned to each resident in the country was used to combine the registry data.15 Personal identity number contains information on date of birth and sex, and was used to derive age information.

The Finnish Cancer Registry provided data on incident cancers, including topography or cancer location, histology, cancer stage (local, locally advanced, advanced), and whether chemotherapy, radiotherapy or surgical treatment was given.

The Finnish Patient Registry has data on admission and discharge dates, operations codes, diagnosis codes and the hospital or healthcare unit identification number where these codes were assigned. These data were used to identify incident cancers and patients receiving surgical treatment, as well as for calculating comorbidities and annual hospital volume of gastric cancer surgery. Comorbidities were defined using the well-validated Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) not including gastric cancer, by retrieving diagnoses before index admission for surgery.16 Neoadjuvant therapy codes were used to find patients undergoing neoadjuvant or perioperative treatment. The annual hospital volume was assessed by calculating the number of gastrectomies for the study patients during the year of surgery in the hospital the patient was operated in.

Statistics Finland provided data on the dates and causes of death, which are 100% and >99% complete, respectively. Education registry had information on education starting from year 1970 and it was used for obtaining the highest education grade of the patients.

Incident cancers were identified from cancer registry records and patient registry, using the relevant topographic in the cancer registry, and International Classification of Diseases-9 (ICD-9) and ICD-10 codes in the patient registry.14 The patient had to have cancer diagnosis in either of the registries, to ensure complete identification. Surgical codes concerning gastrectomy or endoscopic mucosal surgery were then searched in the Patient Registry to identify patients undergoing surgical treatment.14

Statistics

The demographic factors were tabulated and Kaplan-Meier curves were calculated according to the life table method.17 The endpoints were all-cause mortality and cancer-specific mortality, defined as mortality for oesophago-gastric cancers to reduce misclassification bias, which is common especially for gastric cardia cancer.18

Patient and public involvement

Patients or public were not involved in the development of the research question and study design or conducting the present study.

Findings to date

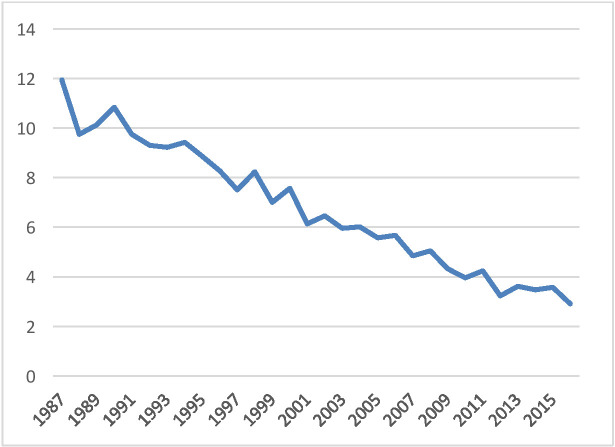

A total of 10 457 patients were surgically treated for gastric cancer in Finland during years 1987–2016. This is almost 40% more than the initial estimate of 7500 patients.14 As seen in figure 2, majority of the patients were operated during the first half of the study period, beginning with almost 12 operated patients with gastric cancer per 100 000 population in 1987 and linearly declining to less than 2/100 000 population in the whole country in 2016. According to the official statistics, also the number of incident gastric cancer cases and deaths decreased during the study period (figure 1).3

Figure 2.

Number of surgically treated patients with gastric cancer per 100 000 population between 1987 and 2016.

The vast majority of patients (90.1%) were identified to have cancer in both patient and cancer registry, while 7.4% had cancer or unclear tumour diagnosis in the patient registry only, and 2.5% had cancer diagnosis in the cancer registry only (table 1).

Table 1.

Identification of the patients with gastric cancer by source registry

| Patients’ number (%) |

|

| Total | 10 457 (100) |

| Cancer diagnosis in both hospital discharge registry and cancer registry | 9421 (90.1) |

| Cancer diagnosis in only hospital discharge registry | 699 (6.7) |

| Cancer diagnosis in only cancer registry | 265 (2.5) |

| Unclear tumour diagnosis and surgery code in hospital discharge registry | 72 (0.7) |

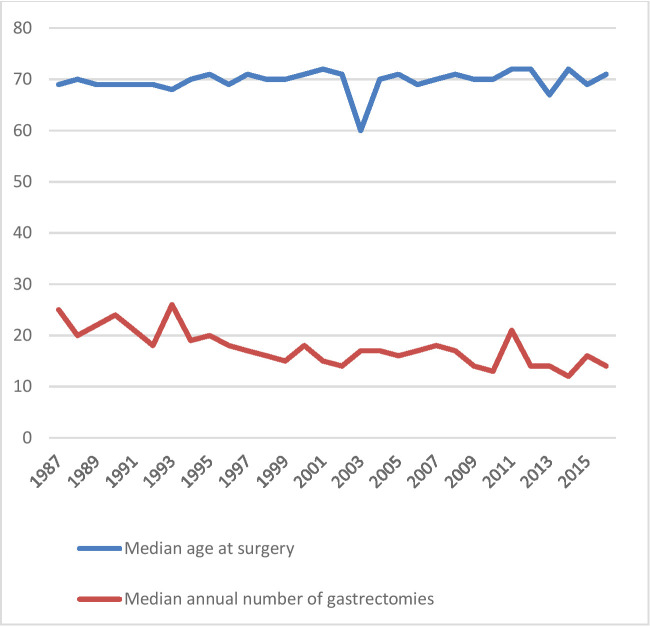

Table 2 summarises the demographic variables of the patients. The median age at the time of operation during the whole study period was 70.0 years, and remained quite constant over time (figure 3). The proportion of men was 54.5% (n=5695). Education data were lacking in 68.9% (7,207) of the patients, and of those with data available, the majority had less than 12 years of formal education. Most of the patients had CCI of 0 at the time of operation (n=6731, 64.6%), while 2408 (23.0%) had CCI of 1 and 1318 (12.6%) had CCI of 2 or more.

Table 2.

Demographics of the surgically treated patients with gastric cancer in Finland 1987–2016

| Patients’ number (%) |

|

| Total | 10 457 (100) |

| Age at surgery (years) | |

| ≤50 | 1017 (9.7) |

| 51–60 | 1605 (15.3) |

| 61–70 | 2856 (27.3) |

| 71–80 | 3479 (33.3) |

| >80 | 1500 (14.3) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 5695 (54.5) |

| Female | 4762 (45.5) |

| Education (years) | |

| ≤12 | 1960 (18.7) |

| 13–15 | 994 (9.5) |

| >15 | 296 (2.8) |

| Missing | 7207 (68.9) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | |

| 0 | 6731 (64.4) |

| 1 | 2408 (23.0) |

| 2 | 892 (8.5) |

| 3 | 287 (2.7) |

| ≥4 | 139 (1.3) |

| Stage | |

| Local | 3208 (30.7) |

| Locally advanced | 2146 (20.5) |

| Advanced | 2444 (23.4) |

| Unclear | 1995 (18.3) |

| Missing | 744 (7.1) |

| Histology | |

| Adenocarcinoma | 9154 (87.6) |

| Other | 559 (5.3) |

| Missing | 744 (7.1) |

Figure 3.

The median age at surgery and median annual volume of gastrectomies over time in Finland.

Cancer staging was available for 7798 (74.6%) patients. Of these 7798 patients, 41.1% had local cancer, 27.5% had locally advanced cancer and 31.3% had advanced cancer according to the cancer registry. Histology was available for 9713 patients, of whom the majority had adenocarcinoma (94.2%). More accurate definition of histomorphology was not reliably possible using registry data.

The details on treatment are summarised in table 3. The absolute majority underwent gastrectomy (n=10 140, 97.0%), including total and partial gastrectomies, followed by oesophagectomy, combined oesophagogastrectomy, and endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) or endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD), respectively. Minimally invasive (laparoscopic) approach was used in only 113 patients. Neoadjuvant or perioperative treatment was given to 1209 (11.6%) patients, with chemotherapy alone being the most common modality. The use of neoadjuvant or perioperative treatment increased from 8.3% in 1987–2006 to 24.6% in 2007–2016.

Table 3.

Treatment details of the patients with gastric cancer included in FINEGO

| Patients’ number (%) |

|

| Total | 10 457 (100) |

| Surgery type | |

| Gastrectomy | 10 140 (97.0) |

| Oesophagectomy | 145 (1.4) |

| Oesophagogastrectomy | 98 (0.9) |

| EMR or ESD | 74 (0.7) |

| Surgical approach | |

| Open | 10 270 (98.2) |

| Minimally invasive | 113 (1.1) |

| Not applicable | 74 (0.7) |

| Neoadjuvant or perioperative treatment | |

| None | 9248 (88.4) |

| Chemotherapy | 984 (9.4) |

| Radiotherapy | 55 (0.5) |

| Chemoradiotherapy | 170 (1.6) |

| Hospital volume of gastrectomy | |

| 1–10 per year | 2602 (24.9) |

| 11–20 per year | 3428 (32.8) |

| 21–30 per year | 1963 (18.8) |

| 31–81 per year | 2236 (21.4) |

| Not applicable or available | 228 (2.2) |

EMR, endoscopic mucosal resection; ESD, endoscopic submucosal dissection; FINEGO, Finnish National Esophago-Gastric Cancer Cohort.

Median annual hospital volume only decreased over time from over 20 gastrectomies per year to around 15 gastrectomies per year during the study period (figure 3), despite the strong decrease in the total number of gastrectomies in the country (figure 2). Of all patients, 2602 (24.9%) were operated in hospitals performing 1–10 gastrectomies per year, and 2236 (21.4%) in hospitals performing 31–81 gastrectomies per year (table 3).

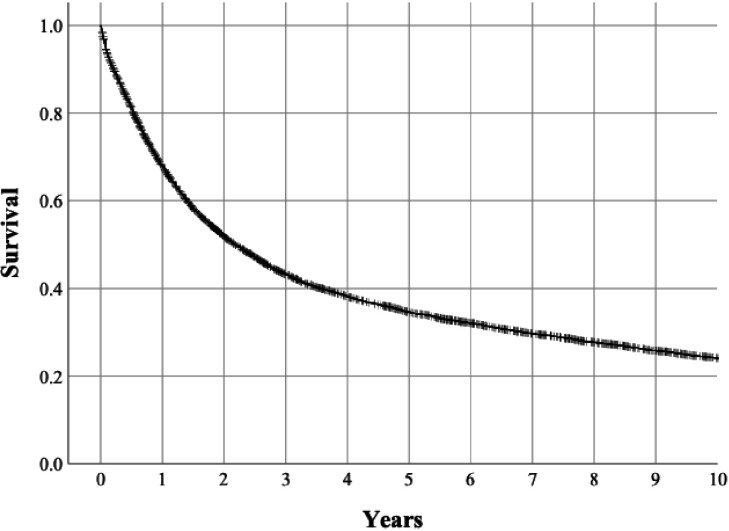

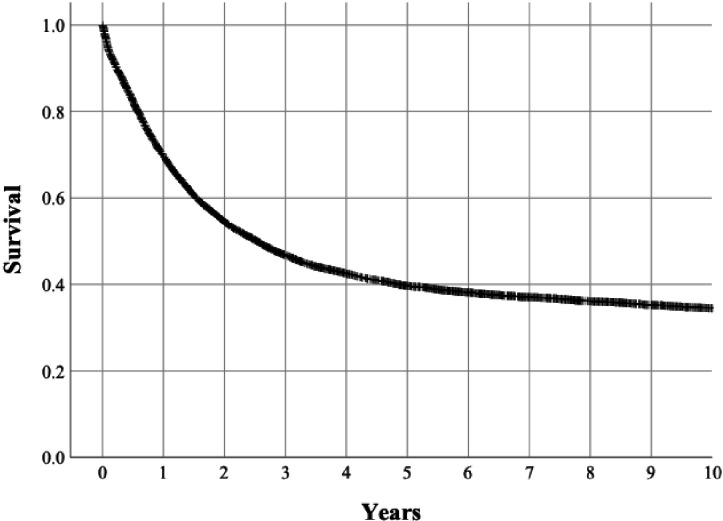

There were 8561 deaths during the study period, of which 6474 were due to oesophago-gastric cancer according to the causes of death registry. Of the 10 457 patients, 67.9% were alive at 1 year after surgery, 43.3 were alive at 3 years after surgery, 34.6% were alive at 5 years after surgery and 24.1% at 10 years after surgery (figure 4). For cancer-specific survival, the respective figures were 69.7% at 1 year after surgery, 46.8 at 3 years after surgery, 39.7% were alive at 5 years after surgery and 34.5% at 10 years after surgery (figure 5).

Figure 4.

Kaplan-Meier curve depicting 10-year all-cause mortality in the surgically treated patients with gastric cancer.

Figure 5.

Kaplan-Meier curve depicting 10-year cancer-specific mortality in the patients with gastric cancer.

Future plans

In its present form, the FINEGO cohort can be used for conducting epidemiological research including the above registry-based variables. The future studies using this data include a study on the trends of gastric cancer over time in Finland, as well as examining the influence of age, sex and comorbidities on the mortality of patients with gastric cancer. Annual hospital volume in relation to short-term and long-term mortality will also be assessed.

As the registry data are to be combined with the data currently being extracted from the individual patient records collected from all hospitals in Finland, we plan to validate the data reported by the registries against patient records. At the time of writing, approximately half of the records of patients with gastric cancer have been identified or collected, the minority of which have been declared as destroyed. The assessment of patient records for clinical variables will allow accurate estimation of the proportion missing records in the future. The variables extracted from the patient records are presented in online supplemental file 1. Furthermore, misclassification of cardia cancer diagnosis in the registries will be examined in relation to oesophagogastroscopy findings. After completion of clinical data retrieval from the patient records and pathology, we are planning a number of studies to assess postoperative complications and surgical factors such as anastomotic technique in relation to complications, as well as validation of previously identified histological risk factors of long-term gastric cancer mortality.19–21 The collection and evaluation of biobank samples for histological diagnoses is also gaining speed. The first update and extension of the cohort with 5 more years of registry data and consequent patient records and samples is planned for year 2022.

bmjopen-2020-039574supp001.pdf (59.5KB, pdf)

Strengths and limitations

This cohort profile describes the 10 457 patients with gastric cancer included in initial period 1987–2016 of the nationwide, population-based retrospective FINEGO Study.

There are multiple strengths to the FINEGO cohort. The large size of the cohort will make it one of the largest gastric cancer studies with patient records data and histological samples. Its population-based nationwide design together with patient identification from two separate, highly complete nationwide registries eliminates selection bias, and the planned collection and re-review of patient records and histological slides will be done to eliminate misclassification between gastric and oesophageal cancer. For mortality outcomes, the follow-up data are known to be 100% complete. Compared with the existing cohorts of gastric cancer, the majority of which are hospital-based multicentre cohorts originating from high-volume institutions, the present cohort adds real-life data from unselected patients operated at unselected institutions.

Possible limitations include the exclusion of non-operated patients with cancer. The data collection of non-operated patients was deemed unfeasible by the consortium due to their large number and the complicated application process for study permissions from each of the more than 200 primary care facilities separately. The retrospective design allows the collection of large surgical dataset, but might potentially limit data quality, especially on variables that have not been routinely reported, such as smoking, alcohol use, the number of lymph nodes collected or postoperative complications. Furthermore, the long time span of the study might be a limitation in some studies evaluating treatment effects on survival due to changes in patterns of treatment over time. Missing patient data due to missing or destroyed records might limit some analyses, but the high-quality registry data allow non-participation analysis along with the use of multiple imputation methods to overcome these issues.

The present cohort was formed using cancer diagnoses in both cancer and patient registry. Most of the patients were identified in both registries, while less than 10% of the patients were not. It is plausible that some patients were not reported to the cancer registry, as the reporting is required by law but still on the clinicians’ responsibility. For those that had no cancer diagnosis in the patient registry but still had cancer reported to the cancer registry, the reasons might be more complicated as the discharge diagnoses are required to discharge a patient and forwarded automatically to the registry. It might be that these patients had an unclear tumour at the time of operation and the cancer was reported to the cancer registry at the time of histological confirmation, but the diagnosis was not updated in the patient records at any time. In the future, the reasons for missing diagnoses are to be examined in detail after the completion of the collection of patient records.

The median age at surgery for the patients with gastric cancer in the present study was quite constantly at 70 years, which is 3 years lower compared with surgically treated patients in a recent Swedish population-based study.7 The male predominance (54.5%) observed in this study was somewhat less prominent than in the Swedish study, where 58% of the gastric non-cardia adenocarcinoma and 76% of cardia carcinoma were men,7 as well as in a population-based study from the Netherlands where 61% were men.22 The patients had less comorbidity (64.4% had no comorbidities) in the present study, compared with the population-based Swedish (58%–65%)7 and Dutch studies (20%–41%).22 Taken together, the demographics of the gastric cancers in FINEGO are highly similar to other population-based studies in gastric cancer. Education data were missing for the majority due to the introduction of education registry in 1970, when the majority of the patients had already obtained their highest education.

According to the data provided by the cancer registry, the majority had local cancer, but also more than 30% had advanced cancer. Reflecting on the relatively good 5-year survival of 35% and taking into account the long study period it would be plausible that at least some of these patients might have had only local or locally advanced cancer at the time of the operation. It might be that such cancer might have been reported to the cancer registry not by the surgeon at operation, but only at the time of the recurrence by the oncologist, whereby a more advanced stage would have been registered. Histology was adenocarcinoma in the majority of the patients with histology data available (94%), as expected. Dividing the patients into intestinal and diffuse-type cancers was not possible with the available data, as the majority of the patients had a histomorphology code of adenocarcinoma not otherwise specified. We aim to validate the cancer registry staging data against the patient records collected from each individual to establish a view on the accuracy of cancer staging information after finishing the patient records and pathology data collection.

The majority of the patients underwent gastrectomy while oesophagectomy and combined oesophagogastrectomy were probably more frequently used in cardia cancer. There were only 113 laparoscopic resections in the cohort, compared with more than 10 000 open procedures. Gastric cancer is rarely diagnosed at early stage in Finland, and it was only recently shown that laparoscopic gastrectomy has oncologically comparable results to open resection in locally advanced cancer.23 24 The low number may also reflect the fact that no separate code exists for laparoscopic total gastrectomy in the NOMESCO-classification, which might result in a notable underestimation of laparoscopic procedures for gastric cancer. However, total gastrectomies may still be coded under ‘other laparoscopic gastrectomy’. The use of EMR and ESD was also low, but these emerging treatments for early-stage or intramucosal cancers only suitable for a minority of the patients are more and more used. Neoadjuvant and perioperative treatments became more common in Finland during the last 10 years of the study period, after the publication of several landmark trials.6 25 In the total cohort, 12% of the patients underwent neoadjuvant or perioperative therapy, which mostly was given as chemotherapy, with increase over time. As Finnish Cancer Registry relies on passive recording (clinician notifications) on oncological treatments, it is possible that some or even a majority of oncological treatments have not been recorded, resulting in a probable underestimation of oncological treatments. Due to registration of neoadjuvant treatment, there was no way to examine the use of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER-2)-related treatment using registry data. However, this is possible after finishing the data collection from the patient records.

During the study period, gastric cancer resections have been heavily centralised by governmental efforts. There were a total of 68 institutions that conducted gastrectomies during the study period, while in 2015 there were only 19 institutions. Due to the rapidly decreasing incidence of gastric cancer, the median annual hospital volume of gastrectomies has also decreased from 1987 to 2016. Low-centre volumes and gastric cancer becoming a relatively rare cancer might at least partly explain the slow adoption of minimally invasive gastrectomies in clinical practice.

The 5-year survival in the surgically treated patients with gastric cancer (34.6%) reflects that of the Swedish study (21%–44% in different 5-year periods),7 and is in fact much better than survival of the operated patients with stage I–III non-cardia gastric adenocarcinoma (15%–29% in the different time periods) in the Dutch study.22 This observation further supports the hypothesis that there might be some overestimation of cancer stage for gastric cancer in the Finnish Cancer Registry.

Taken together, this population-based, nationwide retrospective cohort study will provide new evidence regarding various unanswered questions in oesophageal and gastric cancer surgery by combining epidemiological and clinical data, as well as complement randomised clinical trials by assessing their findings in an unselected population.

Collaboration

All data from FINEGO presented in this article are stored by the research group on safe servers at University of Oulu, Finland, and handled confidentially. Currently, only the research team has access to the data. Data access to collaborators can be granted given that relevant government and health officials approve the collaborative study. Researchers interested in collaboration, for example joint efforts combining the dataset with other population-based studies, are welcome to contact Joonas Kauppila (joonas.kauppila@oulu.fi), principal investigator.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: JHK—study idea. JHK, PO, TR, TT, VT, MP, AV, JR, RK, JS, ES, TJK, V-MP, AR, SL and AK—concept and design. JHK, PO, TR, MP, JR, ES, TJK, V-MP, SL and AK—data collection tools development. JHK and MP—obtained permissions. JHK—obtained funding. JHK and PO—statistical analysis. JHK, PO, TR, TT, VT, MP, AV, JR, RK, JS, ES, TJK, V-MP, AR, SL and AK—interpretation. JHK—drafted the manuscript. JHK, PO, TR, TT, VT, MP, AV, JR, RK, JS, ES, TJK, V-MP, AR, SL and AK—critical revision for intellectual content and accepted submitted version. JHK—guarantor.

Funding: This work is supported by research grants from the Sigrid Jusélius Foundation (Sigrid Juséliuksen Säätiö), The Finnish Cancer Foundation (Syöpäsäätiö), Päivikki and Sakari Sohlberg Foundation and Orion Research Foundation (Orionin Tutkimussäätiö).

Disclaimer: The funding sources have no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data; preparation, review or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the study protocol for publication.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The study has been approved by ethical committee in Northern Osthrobothnia (EETMK 115/2016), The National Institute for Health and Welfare (THL/169/5.05.00), Statistics Finland (TK-53-1478-17) and the Office of the Data Protection Ombudsman (Dnro 506/402/17), Finland. Relevant local permissions and registrations were obtained from all the 21 hospital districts. Individual informed consent will not be sought from the patients whose data are used in this observational study. Obtaining the informed consent has been waived by the Finnish law. The study will be conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available upon reasonable request. Data may be obtained from a third party and are not publicly available. All data from FINEGO presented in this article are stored by the research group on safe servers at University of Oulu, Finland, and handled confidentially. Currently, only the research team has access to the data. Data access to collaborators can be granted given that relevant government and health officials approve the collaborative study. Researchers interested in collaboration, for example joint efforts combining the dataset with other population-based studies, are welcome to contact Joonas Kauppila (joonas.kauppila@oulu.fi), principal investigator.

Supplemental material This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

References

- 1., Fitzmaurice C, Allen C, et al. , Global Burden of Disease Cancer Collaboration . Global, regional, and National cancer incidence, mortality, years of life lost, years lived with disability, and Disability-Adjusted life-years for 32 cancer groups, 1990 to 2015: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study. JAMA Oncol 2017;3:524–48. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.5688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Luo G, Zhang Y, Guo P, et al. Global patterns and trends in stomach cancer incidence: age, period and birth cohort analysis. Int J Cancer 2017;141:1333–44. 10.1002/ijc.30835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Finnish cancer registry. Available: https://cancerregistry.fi/statistics/cancer-statistics/ [Accessed 5 Mar 2020].

- 4.Van Cutsem E, Sagaert X, Topal B, et al. Gastric cancer. The Lancet 2016;388:2654–64. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30354-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferlay J, Shin H-R, Bray F, et al. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer 2010;127:2893–917. 10.1002/ijc.25516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cunningham D, Allum WH, Stenning SP, et al. Perioperative chemotherapy versus surgery alone for resectable gastroesophageal cancer. N Engl J Med 2006;355:11–20. 10.1056/NEJMoa055531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Asplund J, Kauppila JH, Mattsson F, et al. Survival trends in gastric adenocarcinoma: a population-based study in Sweden. Ann Surg Oncol 2018;25:2693–702. 10.1245/s10434-018-6627-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gottlieb-Vedi E, Mattsson F, Lagergren P, et al. Annual hospital volume of surgery for gastrointestinal cancer in relation to prognosis. Eur J Surg Oncol 2019;45:1839–46. 10.1016/j.ejso.2019.03.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seufert RM, Schmidt-Matthiesen A, Beyer A. Total gastrectomy and oesophagojejunostomy--a prospective randomized trial of hand-sutured versus mechanically stapled anastomoses. Br J Surg 1990;77:50–2. 10.1002/bjs.1800770118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takeyoshi I, Ohwada S, Ogawa T, et al. Esophageal anastomosis following gastrectomy for gastric cancer: comparison of hand-sewn and stapling technique. Hepatogastroenterology 2000;47:1026–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown AM, Giugliano DN, Berger AC, et al. Surgical approaches to adenocarcinoma of the gastroesophageal junction: the Siewert II conundrum. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2017;402:1153–8. 10.1007/s00423-017-1610-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thygesen LC, Ersbøll AK. When the entire population is the sample: strengths and limitations in register-based epidemiology. Eur J Epidemiol 2014;29:551–8. 10.1007/s10654-013-9873-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maret-Ouda J, Tao W, Wahlin K, et al. Nordic registry-based cohort studies: possibilities and pitfalls when combining Nordic registry data. Scand J Public Health 2017;45:14–19. 10.1177/1403494817702336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kauppila JH, Ohtonen P, Karttunen TJ, et al. Finnish national Esophago-Gastric cancer cohort (FINEGO) for studying outcomes after oesophageal and gastric cancer surgery: a protocol for a retrospective, population-based, nationwide cohort study in Finland. BMJ Open 2019;9:e024094. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ludvigsson JF, Otterblad-Olausson P, Pettersson BU, et al. The Swedish personal identity number: possibilities and pitfalls in healthcare and medical research. Eur J Epidemiol 2009;24:659–67. 10.1007/s10654-009-9350-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brusselaers N, Lagergren J. The Charlson comorbidity index in registry-based research. Methods Inf Med 2017;56:401–6. 10.3414/ME17-01-0051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cutler SJ, Ederer F. Maximum utilization of the life table method in analyzing survival. J Chronic Dis 1958;8:699–712. 10.1016/0021-9681(58)90126-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lindblad M, Ye W, Lindgren A, et al. Disparities in the classification of esophageal and cardia adenocarcinomas and their influence on reported incidence rates. Ann Surg 2006;243:479–85. 10.1097/01.sla.0000205825.34452.43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kemi NA, Eskuri M, Pohjanen V-M, et al. Histological assessment of stromal maturity as a prognostic factor in surgically treated gastric adenocarcinoma. Histopathology 2019;75:882–9. 10.1111/his.13934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kemi N, Eskuri M, Ikäläinen J, et al. Tumor budding and prognosis in gastric adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 2019;43:229–34. 10.1097/PAS.0000000000001181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kemi N, Eskuri M, Herva A, et al. Tumour-Stroma ratio and prognosis in gastric adenocarcinoma. Br J Cancer 2018;119:435–9. 10.1038/s41416-018-0202-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dassen AE, Lemmens VEPP, van de Poll-Franse LV, et al. Trends in incidence, treatment and survival of gastric adenocarcinoma between 1990 and 2007: a population-based study in the Netherlands. Eur J Cancer 2010;46:1101–10. 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beyer K, Baukloh A-K, Kamphues C, et al. Laparoscopic versus open gastrectomy for locally advanced gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. World J Surg Oncol 2019;17:68. 10.1186/s12957-019-1600-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yu J, Huang C, Sun Y, et al. Effect of laparoscopic vs open distal gastrectomy on 3-year disease-free survival in patients with locally advanced gastric cancer: the CLASS-01 randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2019;321:1983–92. 10.1001/jama.2019.5359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ychou M, Boige V, Pignon J-P, et al. Perioperative chemotherapy compared with surgery alone for resectable gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma: an FNCLCC and FFCD multicenter phase III trial. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:1715–21. 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.0597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2020-039574supp001.pdf (59.5KB, pdf)