Abstract

Purpose

Adipose derived mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are hypothesized to supplement tissues with growth factors essential for regeneration and neovascularization. The purpose of this study was to determine the effect of MSCs with respect to neoangiogenesis when seeded onto a decellularized nerve allograft in a rat sciatic defect model.

Methods

Allograft nerves were harvested from Sprague-Dawley rats and decellularized. MSCs were obtained from Lewis rats. 10mm sciatic nerve defects in Lewis rats were reconstructed with reversed autograft nerves, decellularized allografts, decellularized allografts seeded with undifferentiated MSC or decellularized allografts seeded with differentiated MSCs. At 16 weeks, the vascular surface area and volume were evaluated.

Results

The vascular surface area in normal nerves (34.9±5.7%.), autografts (29.5±8.7%), allografts seeded with differentiated (38.9±7.0%) and undifferentiated MSCs (29.2±3.4%) did not significantly differ from each other. Unseeded allografts (21.2±6.2%) had a significantly lower vascular surface area percentage than normal non-operated nerves (13.7%, p=0.001) and allografts seeded with differentiated MSCs (17.8%, p=0.001). Although the vascular surface area was significantly correlated to the vascular volume (r=0.416; p=0.008), no significant differences were found between groups concerning vascular volumes. The vascularization pattern in allografts seeded with MSCs consisted of an extensive non-aligned network of micro-vessels with a centripetal pattern, while the vessels in autografts and normal nerves were more longitudinally aligned with longitudinal inosculation patterns.

Conclusions

Neoangiogenesis of decellularized allograft nerve was enhanced by stem cell seeding, in particular by differentiated MSCs. The pattern of vascularization was different between processed allograft nerves seeded with MSCs compared to autograft nerves.

INTRODUCTION

Compared to decellularized allografts or bioabsorbable synthetic conduits, autograft nerves continue to result in superior functional outcomes after peripheral nerve repair. One hypothesis for autografts superiority is the ability of autografts to revascularize. 1–3 Revascularization of injured tissue is an essential process in tissue regeneration as it relieves injury-induced hypoxia at the regeneration site while facilitating the delivery of nutrients and cells essential for the regeneration process. 4 Revascularization occurs as early as 2 days after nerve injury and precedes the axonal regeneration. 5,6 Hypoxia in peripheral nerves causes macrophages to secrete vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), which induces (neo)angiogenesis and facilitates trophic factors to arrive at the regeneration site. 7 The endothelial cells of newly formed blood vessels have a directional function by guiding Schwann cells across the nerve-gap, which direct the regenerating axons in the correct direction. 6,8 A sufficient volume of well-organized newly formed vessels in both nerve stumps is requisite for a functional outcome after peripheral nerve repair and has been confirmed in several animal-models. 3,9,10 Improved revascularization and diminished duration of avascularity has been suggested to prevent central fibrosis or necrosis in autografts compared to decellularized allografts, especially in large nerve gaps.11–14 Improved vascularization could therefore lead to improved nerve regeneration in decellularized allografts.

In order to improve vascularization, numerous studies have evaluated the addition of VEGF to nerve reconstructions. Although some studies demonstrated improved vascularization by the addition of VEGF, they failed to prove any benefit of VEGF with respect to functional outcomes demonstrating that the addition of a single growth factor was insufficient to replicate the complex angiogenesis cascade. 15–19

Adipose derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs), when seeded onto allograft decellularized nerves, result in the production of neurotrophic and angiogenic factors, one of which is VEGF. 20 While the exact role of MSCs (structural vs immunomodulatory) continues to be defined, it has been demonstrated that MSCs have a finite lifespan, stimulate tissue repair via release of trophic factors and produce proteins and cytokines that stimulate tissue regeneration with immunomodulatory effects. 20–25 MSCs differentiated into Schwann-like cells (differentiated MSCs) in vitro lead to increased gene expressions of angiogenic (VEGF) and neurotrophic genes when compared to undifferentiated MSCs 20,22,26,27 and are considered nerve regeneration catalysts. 19 The disadvantages of differentiating MSC include the extra preparation time, expense and extra handling of the cells. The effect of differentiation thus needs to be carefully investigated.

In order to equal the results of nerve autografts, efforts have been recently made to optimize the quality of decellularized allografts. 28 To improve their outcomes a non-traumatic dynamic seeding strategy has been developed to seed undifferentiated and differentiated MSCs to the allograft surfaces, which survive up to a month in vivo. 29 Furthermore, differences in gene expression levels (and thus growth factors produced) have been elucidated between differentiate and undifferentiated MSCs, and demonstrated that differentiated MSCs in particular showed enhanced expressions of VEGF after interacting with the outer surface of the decellularized allografts. 25,32

The purpose of this study was to either substantiate or invalidate the hypothesis whether the previously demonstrated different gene expression profiles of differentiated and undifferentiated MSCs would lead to different levels and patterns of vascularization when dynamically seeded onto processed/decellularized nerve allografts, in comparison to unseeded allografts and autografts.

METHODS

This study was approved by the IACUC institutional review committee and our Institutional Review Board (IACUC protocol A2464-00). A 10 mm segment of the right sciatic nerve of 20 Lewis rats (Envigo, USA) was excised and was replaced with either (i) a reversed autograft, (ii) a processed/decellularized nerve allograft, (iii) a processed/decellularized nerve allograft seeded with undifferentiated MSCs or (iv) a processed/decellularized nerve allograft seeded with differentiated MSCs. All four groups were sacrificed after 16 weeks to determine and compare degree and patterns of revascularization of the nerves. The 16 week survival period was chosen based on previous research indicating 16 weeks is the time period in which nerve regeneration matures. 33

Nerve allograft harvest and processing

Ten Sprague-Dawley rats (Envigo, Madison, WI, USA) weighing 250–350 grams served as donors of 20 sciatic nerve segments of approximately 15 mm each. Sprague-Dawley rats were used to obtain a major histocompatibility complex mismatch with the recipient Lewis rats, in order to mimic a clinical setting in which allogenous donor nerves will be used. 34,35 The rats were anesthetized in an isoflurane induction chamber and euthanized with an overdose of pentobarbital once asleep. Both sciatic nerves were carefully dissected with sharp dissecting scissors under an operating microscope (Zeiss OpMi6, Carl Zeiss Surgical GmbH, Oberkochen, Germany). Directly after their harvest, the obtained sciatic nerve segments were processed/decellularized according to a previously published five-day protocol that includes multiple washing steps and emerging in elastase. 28 Sterilization of the nerve segments was obtained with γ-irradiation.

Stem cell preparation and differentiation

In accordance with a future clinical trial in which the MSCs will be harvested from a patient, MSCs were harvested from the inguinal fat pad of an inbred Lewis rat and processed per Kingham and colleagues protocol. 36 The obtained MSCs were cultured in previously described cell culture conditions. 37–39 The MSCs complied with the criteria for MSCs, defined by the International Society for Cellular Therapy previously: they were plastic adherent and multi-potent and expressed canonical MSC-markers like CD44 (88.2%) and CD90 (88.3%) while markers such as CD34 and CD45 were absent. 30,40

Cell culture

The obtained MSCs were cultured in growth medium that contained α-MEM (Advanced MEM (1x); Life Technologies Corporation, NY, USA), 5% platelet lysate (PLTMax®; Mill Creek Life Sciences, MN, USA), 1% Penicillin/Streptomycin (Penicillin-Streptomycin (10.000 U/mL; Life Technologies Corporation, NY, USA), 1% GlutaMAX (GlutaMAX Supplement 100X; Life Technologies Corporation, NY, USA) and 0.2% Heparin (Heparin Sodium Injection, USP, 1.000 USP units per mL; Fresenius Kabi, IL, USA).

Differentiation of MSCs

The differentiation of MSCs into Schwann cell-like cells was performed and verified according to a previously described protocol. This protocol has shown to morphologically change 81.5% of the MSCs exposed to the differentiation medium into a typical spindle-like shape and lets approximately 40–45% of the exposed MSCs express glial cell marker GFAP, Schwann cell marker S100 and neurotrophin receptor p75.36 After two preparatory steps with ß-mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich corp., MO, USA) and all-trans-retinoic acid (1:1000, dilution of stock; Sigma-Aldrich Corp., MO, USA), a differentiation cocktail was introduced to their growth medium. This differentiation cocktail consisted of Forskolin (Sigma-Aldrich corp., MO, USA), basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF; PeproTech, NJ, USA), platelet derived growth factor (PDGF-AA; PeproTech, NJ, USA), and neuregulin-1 ß1 (NRG1-b1; R&D systems Inc, MN, USA).

According to the protocol, MSCs differentiation was verified by immunocytochemistry for S100, GFAP and neurotrophin receptor p75 (Rabbit anti-S100, mouse anti-GFAP and rabbit anti-p75 NTR; all ThermoFisher Scientific, MA, USA). Secondary antibodies goat-anti rabbit FITC and goat anti-mouse Cyanine-3 (both ThermoFisher Scientific, MA, USA) were used to visualize the expression of the before-mentioned markers in differentiated MSCs. Undifferentiated MSC and Schwann cells were used as respectively negative and positive control.

Stem cell seeding

The decellularized allografts were dynamically seeded with 1×10^6 undifferentiated or differentiated MSCs for 12 hours at 37°C. Previous testing has shown that this is the most efficient seeding duration, leading to a seeding efficiency of 80% to 95% respectively. 30,31

Surgical procedure

Twenty male inbred Lewis rats (Envigo, Madison, WI, USA) weighing 250–300 gram, served as recipient rats. The surgical procedure was performed as previously described. 41 The 10 mm section of the sciatic nerve was reversed in the autograft group. The processed allografts, either unseeded, seeded with undifferentiated MSC or seeded with differentiated MSCs, were used to reconstruct a 10 mm sciatic nerve gap in the other three groups. No immunosuppression was administered postoperatively.

Non-survival procedure – measurements

During the non-survival procedures after 16 weeks, all rats (n=5) of each group were anesthetized in an isoflurane induction chamber. Once asleep, the rats were euthanized with an overdose of pentobarbital.

Vascular preservation

A longitudinal incision over the abdomen exposed the abdominal organs. The aorta and inferior vena cava were dissected carefully. A catheter was placed and fixed inside the aorta over which 10 cc of saline was administered to flush the vasculature. Yellow Microfil® (Flow Tech inc., Carver, Massachusetts, USA) was administered by aortic infusion until both toenail matrixes were colored, which required at least 19 mL of Microfil®.15 After 90 minutes of curing, the sciatic nerves were dissected and cleared in 5 days by immersing them in graded series of ethyl alcohol (25% - 50% - 75% - 95%) and a final day in methyl salicylate.

Vascular surface area

To optimize the accuracy of the measured level of revascularization, the vascular surface area and the vascular volume were obtained. The nerve samples were stretched by suturing both ends onto a solid holder. While in a petri dish with methyl salicylate, detailed pictures of the nerve were obtained with a Canon 5D Mark III camera, a Canon 65 mm Macro lens and a Canon Twin Lite Macro strobe light source. Polarized light was used to reduce reflections and a 1:1 magnification was used to ensure consistency of the pictures. To correct for the 3D structure of the nerve sample and the surface area that alters depending on the angle of observation, two pictures of each nerve sample were obtained 180 degrees rotated (i.e. front and back of nerve). The solid holder provided a clear distinction between the front and the back of the nerve sample. The pictures were blinded before analysis. Using Image Pro Plus Software, the total nerve area and the total vessel area were marked and measured and a vessel/nerve area ratio was calculated of each picture taken. The ratios of the two pictures (i.e. front and back of the nerve) were averaged. The obtained photographs also enabled the subjective assessment of the alignment of the preserved vasculature. 42

Vascular volume

With a micro-CT (Inveon Multiple Modality PET/CT scanner, Siemens Medical Solutions USA, Inc., Knoxville, TN), a CT scan was obtained from the nerve samples with an effective pixel size of 9.91μm. As the microfil was more radiopaque than the rest of the nerve, the volume of the total nerve and the volume of the vasculature could be measured with Analyze 12.0 software (AnalyzeDirect, Inc., Overland Park, KS, USA). Eventually, vessel/nerve volume ratios were calculated for each scan.42

Correlations

The correlation between the vascular surface area and volume measurements was obtained to determine whether the methods are complementary to each other.

Statistical analysis

The outcome measures were analyzed with one-way ANOVA, with Bonferroni correction for post-hoc multiple comparisons. Correlations were analyzed with the Pearson’s correlation test. Data are expressed as the mean ±SD. The level of statistical significance was set at α=0.05.

RESULTS

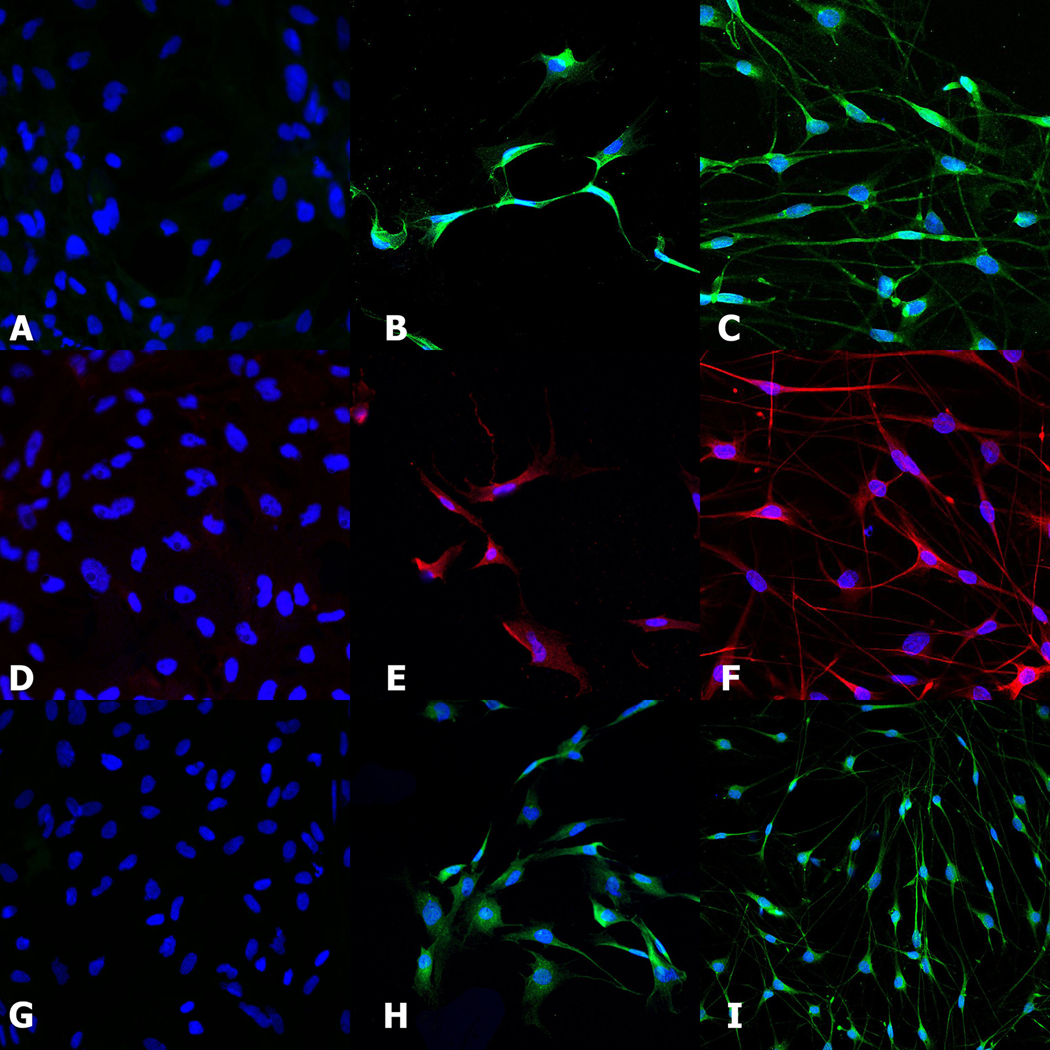

Differentiation of MSCs into Schwann-like cells

Differentiated MSCs all adjusted morphologically to a spindle-like shape and demonstrated expression of Schwann cell markers S100, GFAP and NTR p75, which is in accordance with Schwann cells (Figure 1) and previous studies.

Figure 1.

Differentiation of MSCs into Schwann-like cells was confirmed by comparing the expression of Schwann cell markers S100 (A-B-C), GFAP (D-E-F) and NTR p75 (G-H-I) in the differentiated MSCs(B-E-H) to the expression in Schwann cells (C-F-I) and undifferentiated MSCs (A-D-G).

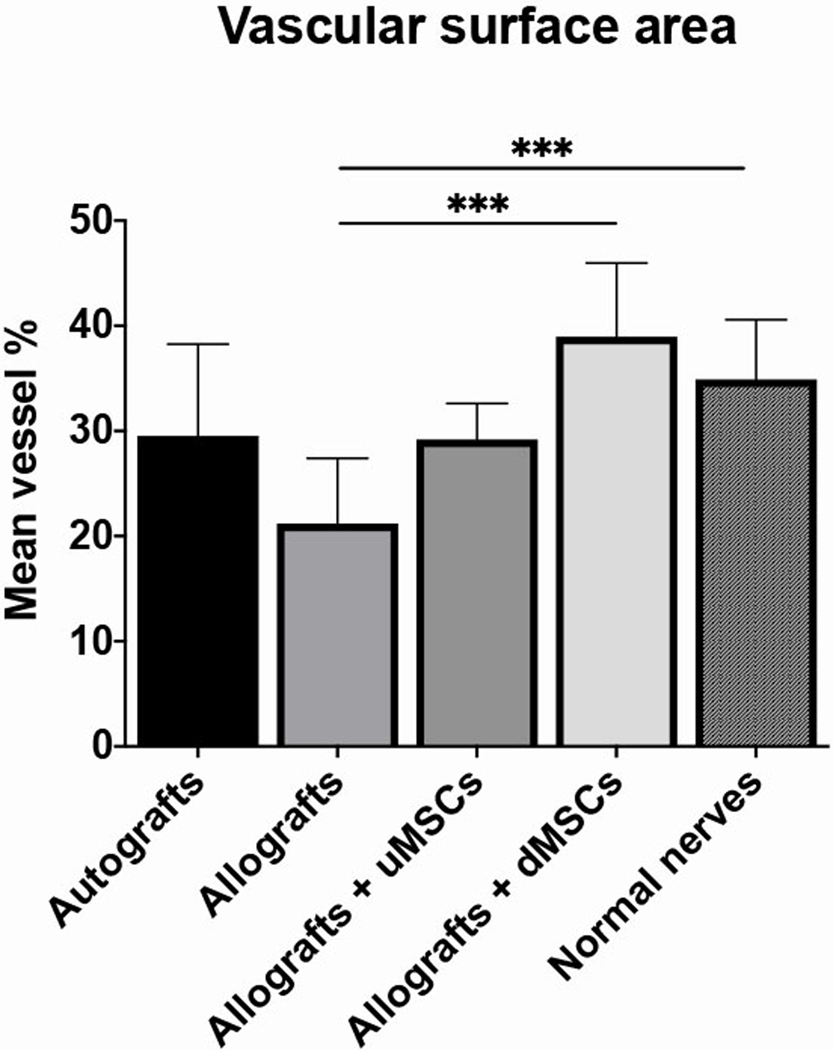

Vascular surface area

Non-operated nerves had a vascular surface area percentage of 34.9±5.7%. Of the four studied groups, the vascular surface area was highest in the group that received allografts seeded with differentiated MSCs (38.9±7.0%), followed by the group with autografts (29.5±8.7%) and the group with allografts seeded with undifferentiated MSC (29.2±3.4%). Unseeded allografts (21.2±6.2%) had a significantly lower mean vascular surface area percentage than normal non-operated nerves (13.7%, p=0.001) and allografts seeded with differentiated MSCs (17.8%, p=0.001) (Figure 2 and 3).

Figure 2.

The vascular surface area outcomes of autografts, allografts, allografts seeded with undifferentiated MSC and allografts seeded with differentiated MSCs. The unseeded allografts showed a significantly lower mean vascular surface percentage than allografts seeded with differentiated MSCs and normal nerves (both p<0.001).

Error bars = standard deviation of the mean

undifferentiated MSC = undifferentiated Mesenchymal Stem Cells

differentiated MSCs = differentiated Mesenchymal Stem Cells

*** = p<0.001

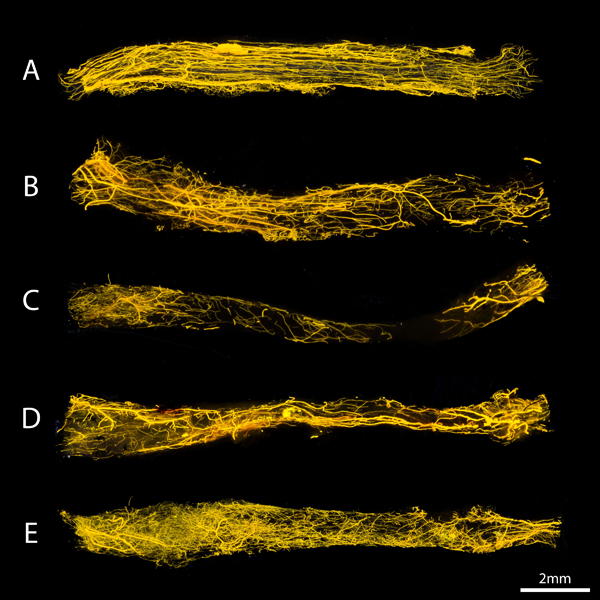

Figure 3.

Conventional images of the vasculature of a normal nerve (A) autografts (B), allografts (C), allografts seeded with undifferentiated MSC (D) and allografts seeded with differentiated MSCs (E). The nerves were positioned from proximal (left) to distal (right). The ingrowth of vessels seem to occurred from both nerve ends, but from proximal in particular. The structuring of the vessels was clearly less organized in our study groups compared to the control nerve.

Revascularization pattern

The vessels of normal, non-operated nerves aligned in the same longitudinal direction as the axons and the vasculature is equally distributed among the entire length of the nerve. The preserved vessels in autograft nerves seemed to be largely longitudinally aligned consistent with inosculation pattern of revascularization, but were less extensively present than in normal nerves. Unseeded allografts had less vascularization in general and demonstrated minimal if any vascularization in their mid-segment. In both MSC-seeded allograft groups, an extensive, non-aligned network of micro-vessels extended from the very proximal to the very distal graft end with a centripetal pattern of revascularization. In all groups, the ingrowth of vessels occurs from both nerve ends, but particularly from the proximal stump.

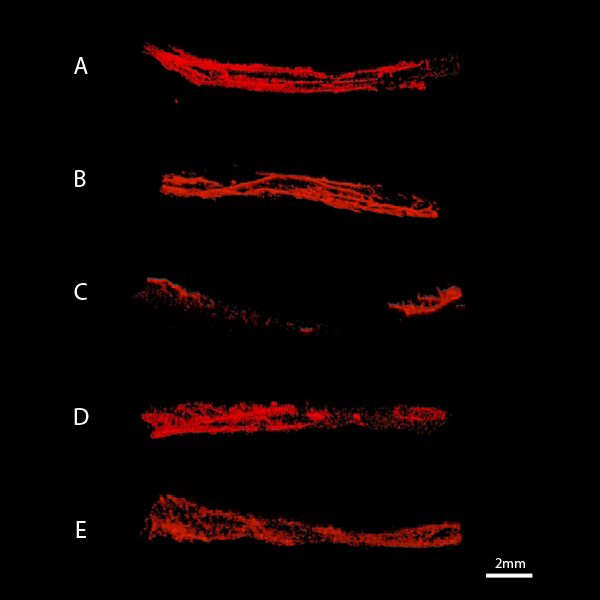

Vascular volume

The vascular volume measurements showed the same trend as the vascular surface area measurements; the allografts seeded with differentiated MSCs contained the highest vascular volume (4.6±3.6%), the outcomes of the autografts (3.78±0.7%) and the allografts seeded with undifferentiated MSC (3.4±0.2%) did not differ and the unseeded allografts scored the least (2.7±1.0%). ANOVA analysis between groups showed no statistically significant differences between the groups (F=0.916; p=0.455) (Figure 4 and 5).

Figure 4.

The vascular volume outcomes of autografts, allografts, allografts seeded with undifferentiated MSC and allografts seeded with differentiated MSCs. None of the differences between the groups was statistically significant.

Error bars = standard deviation of the mean

uMSC = undifferentiated Mesenchymal Stem Cells

dMSCs = differentiated Mesenchymal Stem Cells

Figure 5.

Snapshots of the obtained micro-CT scans that served for the volume measurements of normal nerves (A) autografts (B), allografts (C), allografts seeded with undifferentiated MSCs (D) and allografts seeded with differentiated MSCs (E). The nerves are positioned from proximal (left) to distal (right). The smallest vessels not detected by the micro-CT due to its effective pixel size.

The vascular surface area and the vascular volume measurements were significantly correlated (r=0.416; p=0.008).

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to determine whether the previously demonstrated different gene expression profiles of differentiated and undifferentiated MSCs would lead to different levels and patterns of vascularization when dynamically seeded onto processed/decellularized nerve allografts. Digital photography and micro-CT imaging allowed for the quantification and comparison of vascularity.

Neoangiogenesis has been previously quantified by counting of RECA-1 positive structures (immunohistochemical staining) and histomorphometric evaluation or the measurement of capillary density. 20,43–45 These methods unfortunately fall short when aiming to precisely quantify and describe vascularity volumes and vascularization patterns. An evaluation strategy in which both 2D and 3D measures can be reliably obtained was used in the current study in order to compare the effect of undifferentiated versus differentiated MSCs.42

With respect to vascularization, there was an increase in the vascular surface area of processed allografts when seeded with undifferentiated and differentiated MSCs. However, only the effect of differentiated MSCs was statistically significant, suggesting that differentiated MSCs enhance (neo)angiogenesis to a greater extent than undifferentiated MSC. The enhanced expression of neurotrophic and angiogenic genes of MSCs when differentiated into Schwann-like cells is the most likely mechanism of the superior degree of (neo)angiogenesis in processed nerve allografts seeded with differentiated MSCs. 19,20,22,25–27,32,36,46 The role of the growth factors in the differentiation medium that might become embedded in the extracellular matrix of the cells cannot be ruled out, but they are not specifically known to stimulate neoangiogenesis. 25 The vascularization in autograft nerves and normal non-operated nerves did not significantly differ from both stem-cell groups.

Revascularization in nerves is hypothesized to occur via two mechanisms: centripetal neovascularization (vessels sprouting into the graft from the surrounding tissues) and inosculation (vessels sprouting into the graft from both stump ends into the existing vascular tree). 47 In autografts, there is still an existing vascular tree surrounded by endothelial cells which is likely to increase the vascularization speed and improve the alignment of vessels which was demonstrated in this study.1 In processed allografts, all cellular debris has been removed, leaving no directions for ingrowing vessels. 28 In contrast to the longitudinal alignment of vessels in normal non-operated and autograft nerves, the vascularization of the stem cell-seeded nerve allografts consisted of an extensive network of micro-vessels distributed among the entire nerve that were not in line with the expected direction of axon regeneration (Figure 3). Combining the described differences in revascularization pattern, we hypothesize the predominant mechanism of revascularization in autografts is inosculation, leading to well-aligned and accelerated revascularization. Centripetal neovascularization was hypothetically the predominant mechanism of vascularization or at least had a greater share in the revascularization of allografts seeded with MSCs. Based on the timeline of angiogenic gene expression profiles in previous research32 and the known limited survivability of MSCs in vivo,29 both type of MSCs are expected to accelerated revascularization mainly in the first few days after seeding with a slowly diminishing effect up to 29 days.

The purpose of this study was to determine the effect of type of MSCs on enhancing vascularization of processed nerve allografts and to compare degree and pattern of vascularization to autograft and allograft nerves. It is thus underpowered to perform functional or histological analysis. Despite the small group size however, we were able to clearly demonstrate the effect of MSCs on vascularity. We successfully evaluated the vasculature of nerves in an accurate manner and were able to objectively quantify the amount of (neo)angiogenesis. A future study should focus on functional outcomes.

The effective pixel size of the used micro-CT may have caused a loss in the detection of the smallest vessels, particularly present in both stem cell groups. The CT-scans enabled us to fairly compare the volume of the bigger vessels in the operated nerve to that of the bigger vessels in the non-operated side, but it sub-optimally displayed the smaller vessels. This could partially mask the effect of stem cell seeding, as the MSCs seem to lead to the formation of small vessels in particular. For future research, it is advised to use a micro-CT scanner with a smaller effective pixel size. This is likely to increase the correlation between the vascular volume and the vascular surface area.

Although not part of the current study, the presented concept of seeding either differentiated or undifferentiated MSCs on the surface of decellularized nerve allografts is hypothesized to be clinically applicable. Off the shelve nerve allografts are already clinically available and potentially can be seeded with autologous MSCs, which are easily obtainable from the patient with peripheral nerve injury. If the hypothesized improved vascularity and functional outcome outweigh the extra delay in nerve repair that is necessary for cell-culture (1.5 week) has yet to be determined.

This study demonstrated that the vascularization of nerve grafts can be quantified and that both undifferentiated and differentiated MSCs enhance revascularization of processed nerve allografts.

CONCLUSION

The degree of vascularization of the processed/decellularized allograft nerves were improved by the addition of undifferentiated and differentiated MSCs, of which only the effect of differentiated MSCs was statistically significant. Revascularization of processed/decellularized allograft nerves with or without MSC was mainly via centripetal revascularization compared to revascularization in autograft nerves, which occurred via inosculation.

Acknowledgements

We thank Patricia F. Friedrich for assistance with the preparations of the experiments.

We thank Eric Sheahan for obtaining the conventional photographs presented in this study.

Grant sponsor: NIH R01, ‘Bridging the gap: angiogenesis and stem cell seeding of processed nerve allograft’; Grant number: 1 RO1 NS102360–01A1

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure Statement

The authors have nothing to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zhu Z, Huang Y, Zou X, Zheng C, Liu J, Qiu L, et al. The vascularization pattern of acellular nerve allografts after nerve repair in Sprague-Dawley rats. Neurolog Res 2017;39:1014–1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Niu X, Liu X, Hu J, Jiang L. [Experimental research on revascularization of chemically extracted acellular allogenous nerve graft]. Zhongguo xiu fu chong jian wai ke za zhi = Zhongguo xiufu chongjian waike zazhi = Chin J Repar Reconstr Surg 2009;23:235–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Donzelli R, Capone C, Sgulo FG, Mariniello G, Maiuri F. Vascularized nerve grafts: an experimental study. Neurolog Res 2016;38:669–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wynn TA, Vannella KM. Macrophages in Tissue Repair, Regeneration, and Fibrosis. Immunity 2016;44:450–462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferretti A, Boschi E, Stefani A, Spiga S, Romanelli M, Lemmi M, et al. Angiogenesis and nerve regeneration in a model of human skin equivalent transplant. Life Sci 2003;73:1985–1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cutting CB, McCarthy JG. Comparison of residual osseous mass between vascularized and nonvascularized onlay bone transfers. Plast Reconstr Surg 1983;72:672–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caillaud M, Richard L, Vallat JM, Desmouliere A, Billet F. Peripheral nerve regeneration and intraneural revascularization. Neural Regen Res 2019;14:24–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parrinello S, Napoli I, Ribeiro S, Wingfield Digby P, Fedorova M, Parkinson DB, et al. EphB signaling directs peripheral nerve regeneration through Sox2-dependent Schwann cell sorting. Cell 2010;143:145–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhu Y, Liu S, Zhou S, Yu Z, Tian Z, Zhang C, et al. Vascularized versus nonvascularized facial nerve grafts using a new rabbit model. Plast Reconstr Surg 2015;135:331e–339e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iijima Y, Ajiki T, Murayama A, Takeshita K. Effect of Artificial Nerve Conduit Vascularization on Peripheral Nerve in a Necrotic Bed. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 2016;4:e665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.D’Arpa. Vascularized nerve “grafts”: just a graft or a worthwhile procedure? Plast Aesthet Res 2016;2:183–192. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sunderland S. Nerves and nerve injuries: Churchill Livingstone, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brooks D. The place of nerve-grafting in orthopaedic surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1955;37A:299–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seddon HJ. Nerve grafting. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1963;45:447–461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giusti G, Lee JY, Kremer T, Friedrich P, Bishop AT, Shin AY. The influence of vascularization of transplanted processed allograft nerve on return of motor function in rats. Microsurg 2016;36:134–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wongtrakul S, Bishop AT, Friedrich PF. Vascular endothelial growth factor promotion of neoangiogenesis in conventional nerve grafts. J Hand Surg 2002;27:277–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zor F, Deveci M, Kilic A, Ozdag MF, Kurt B, Sengezer M, et al. Effect of VEGF gene therapy and hyaluronic acid film sheath on peripheral nerve regeneration. Microsurg 2014;34:209–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nishida Y, Yamada Y, Kanemaru H, Ohazama A, Maeda T, Seo K. Vascularization via activation of VEGF-VEGFR signaling is essential for peripheral nerve regeneration. Biomed Res 2018;39:287–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoben G, Yan Y, Iyer N, Newton P, Hunter DA, Moore AM, et al. Comparison of acellular nerve allograft modification with Schwann cells or VEGF. Hand 2015;10:396–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kingham PJ, Kolar MK, Novikova LN, Novikov LN, Wiberg M. Stimulating the neurotrophic and angiogenic properties of human adipose-derived stem cells enhances nerve repair. Stem Cells & Develop 2014;23:741–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Orbay H, Uysal AC, Hyakusoku H, Mizuno H. Differentiated and undifferentiated adipose-derived stem cells improve function in rats with peripheral nerve gaps. JPRAS 2012;65:657–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tomita K, Madura T, Sakai Y, Yano K, Terenghi G, Hosokawa K. Glial differentiation of human adipose-derived stem cells: implications for cell-based transplantation therapy. Neurosci 2013;236:55–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Caplan AI. Adult mesenchymal stem cells: When, where and how. Stem Cells Int’l 2015;2015:628767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu Y, Zhang Z, Qin Y, Wu H, Lv Q, Chen X, et al. A new method for Schwann-like cell differentiation of adipose derived stem cells. Neurosci Ltrs 2013;551:79–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mathot F, Shin AY, Van Wijnen AJ. Targeted stimulation of MSCs in peripheral nerve repair. Gene 2019;710:17–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhao Z, Wang Y, Peng J, Ren Z, Zhan S, Liu Y, et al. Repair of nerve defect with acellular nerve graft supplemented by bone marrow stromal cells in mice. Microsurg 2011;31:388–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang Y, Luo H, Zhang Z, Lu Y, Huang X, Yang L, et al. A nerve graft constructed with xenogeneic acellular nerve matrix and autologous adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Biomat 2010;31:5312–5324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hundepool CA, Nijhuis TH, Kotsougiani D, Friedrich PF, Bishop AT, Shin AY. Optimizing decellularization techniques to create a new nerve allograft: an in vitro study using rodent nerve segments. Neurosurg Foc 2017;42:E4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rbia N, Bulstra LF, Thaler R, Hovius SER, van Wijnen AJ, Shin AY. In Vivo Survival of Mesenchymal Stromal Cell-Enhanced Decellularized Nerve Grafts for Segmental Peripheral Nerve Reconstruction. J Hand Surg 2019;44:514.e1–514.e11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mathot F, Rbia N, Bishop AT, Hovius SER, Van Wijnen AJ, Shin AY. Adhesion, distribution, and migration of differentiated and undifferentiated mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) seeded on nerve allografts. JPRAS 2019;pii:S1748–6815(19)30231–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rbia N, Bulstra LF, Bishop AT, van Wijnen AJ, Shin AY. A simple dynamic strategy to deliver stem cells to decellularized nerve allografts. Plast Reconstr Surg 2018;142:402–413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mathot F, Rbia N, Thaler R, Bishop AT, Van Wijnen AJ, Shin AY. Gene expression profiles of differentiated and undifferentiated adipose derived mesenchymal stem cells dynamically seeded onto a processed nerve allograft. Gene 2020;724:144–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tang P, Whiteman DR, Voigt C, Miller MC, Kim H. No difference in outcomes detected between decellular nerve allograft and cable autograft in rat sciatic nerve defects. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2019;101:e42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hudson TW, Zawko S, Deister C, Lundy S, Hu CY, Lee K, et al. Optimized acellular nerve graft is immunologically tolerated and supports regeneration. Tis Eng 2004;10:1641–1651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kumta S, Yip K, Roy N, Lee SK, Leung PC. Revascularisation of bone allografts following vascular bundle implantation: an experimental study in rats. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 1996;115:206–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kingham PJ, Kalbermatten DF, Mahay D, Armstrong SJ, Wiberg M, Terenghi G. Adipose-derived stem cells differentiate into a Schwann cell phenotype and promote neurite outgrowth in vitro. Exper Neurol 2007;207:267–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Crespo-Diaz R, Behfar A, Butler GW, Padley DJ, Sarr MG, Bartunek J, et al. Platelet lysate consisting of a natural repair proteome supports human mesenchymal stem cell proliferation and chromosomal stability. Cell Transpl 2011;20:797–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mader EK, Butler G, Dowdy SC, Mariani A, Knutson KL, Federspiel MJ, et al. Optimizing patient derived mesenchymal stem cells as virus carriers for a phase I clinical trial in ovarian cancer. J Transl Med 2013;11:20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mahmoudifar N, Doran PM. Osteogenic differentiation and osteochondral tissue engineering using human adipose-derived stem cells. Biotechnol Prog 2013;29:176–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dominici M, Le Blanc K, Mueller I, Slaper-Cortenbach I, Marini F, Krause D, et al. Minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. The International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement. Cytother 2006;8:315–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hundepool CA, Bulstra LF, Kotsougiani D, Friedrich PF, Hovius SER, Bishop AT, et al. Comparable functional motor outcomes after repair of peripheral nerve injury with an elastase-processed allograft in a rat sciatic nerve model. Microsurg 2018;38:772–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Saffari TM, Mathot F, Bishop AT, Shin AY. New methods for objective angiogenesis evaluation of rat nerves using microcomputed tomography scanning and conventional photography. Microsurg 2019, November 23 Doi: 10.1002/micr.30537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Perrien DS, Saleh MA, Takahashi K, Madhur MS, Harrison DG, Harris RC, et al. Novel methods for microCT-based analyses of vasculature in the renal cortex reveal a loss of perfusable arterioles and glomeruli in eNOS−/− mice. BMC Nephrol 2016;17:24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kline TL, Knudsen BE, Anderson JL, Vercnocke AJ, Jorgensen SM, Ritman EL. Anatomy of hepatic arteriolo-portal venular shunts evaluated by 3D micro-CT imaging. J Anat 2014;224:724–731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Giusti G, Lee JY, Kremer T, Friedrich P, Bishpo AT, Shin AY. The influence of vascularization of transplanted processed allograft nerve on return of motor function in rats. Microsurg 2016;36:134–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ladak A, Olson J, Tredget EE, Gordon T. Differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells to support peripheral nerve regeneration in a rat model. Exper Neurol 2011;228:242–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Best TJ, Mackinnon SE, Midha R, Hunter DA, Evans PJ. Revascularization of peripheral nerve autografts and allografts. Plast Reconstr Surg 1999;104:152–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe Y, Sasaki R, Matsumine H, Yamato M, Okano T. Undifferentiated and differentiated adipose-derived stem cells improve nerve regeneration in a rat model of facial nerve defect. J Tiss Eng Regen Med 2017;11:362–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]