Abstract

Testing SARS-CoV-2 viral loads in wastewater has recently emerged as a method of tracking the prevalence of the virus and an early-warning tool for predicting outbreaks in the future. This study reports SARS-CoV-2 viral load in wastewater influents and treated effluents of 11 wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs), as well as untreated wastewater from 38 various locations, in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) in May and June 2020. Composite samples collected over twenty-four hours were thermally deactivated for safety, followed by viral concentration using ultrafiltration, RNA extraction using commercially available kits, and viral quantification using RT-qPCR. Furthermore, estimates of the prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in different regions were simulated using Monte Carlo. Results showed that the viral load in wastewater influents from these WWTPs ranged from 7.50E+02 to over 3.40E+04 viral gene copies/L with some plants having no detectable viral RNA by RT-qPCR. The virus was also detected in 85% of untreated wastewater samples taken from different locations across the country, with viral loads in positive samples ranging between 2.86E+02 and over 2.90E+04 gene copies/L. It was also observed that the precautionary measures implemented by the UAE government correlated with a drop in the measured viral load in wastewater samples, which were in line with the reduction of COVID-19 cases reported in the population. Importantly, none of the 11 WWTPs' effluents tested positive during the entire sampling period, indicating that the treatment technologies used in the UAE are efficient in degrading SARS-CoV-2, and confirming the safety of treated re-used water in the country. SARS-CoV-2 wastewater testing has the potential to aid in monitoring or predicting an outbreak location and can shed light on the extent viral spread at the community level.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, Wastewater, Detection, Quantification, Surveillance, UAE

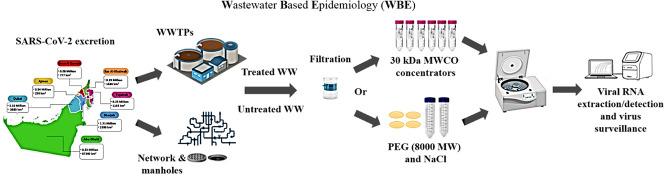

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Coronaviruses (CoVs), which range from 60 to 220 nm in size, are enveloped positive-sense single-stranded ribonucleic acid (RNA) viruses with club-like spikes on their surface, and infect a wide range of hosts including birds and mammals. They were first identified in the mid-1960s, and have traditionally been associated with the common cold in humans. More recently, they gained significant medical importance due to the emergence of three deadly zoonotic strains: (i) severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) in 2002 (mortality rate 11%), (ii) Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) in 2012 (mortality rate 35%), and (iii) SARS-CoV-2 in 2019 (mortality rate still being determined, but estimated at 2–3%) (Randazzo et al., 2020a; Yang et al., 2020; Chen and Li, 2020; World Health Organization (WHO), 2003; World Health Organization (WHO), 2019). CoVs have more detrimental impacts on immunocompromised and elderly individuals and have the potential to create worldwide outbreaks (Chang et al., 2020). The first cases of SARS-CoV-2 infections occurred in either late November or early December 2019, and quickly spread until the World Health Organization (WHO) declared it a Public Health Emergency of International Concern on January 30th 2020, and a pandemic on March 11th 2020. Despite international efforts to contain the virus using various policies, it is still posing a serious global challenge today (Kitajima et al., 2020; Hart and Halden, 2020). Scientists attribute the difficulty in managing the outbreak to a long incubation period (~5 days) and viral shedding and transmission by asymptomatic infected individuals (Xu et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2020).

Most of what we know about viral shedding comes from studies that quantify SARS-CoV-2 in pharyngeal or nasopharyngeal swabs, with very little work done to understand the shedding of this virus in stool. A limited number of studies have shown that the shedding period of SARS-CoV-2 in stool samples varies considerably, and can still be detected up to 27.9 ± 10.7 days after infection in some cases (Xu et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2020a). The major transmission routes of SARS-CoV-2 have been shown to be through aerosol droplets, person to person contact, and contaminated surfaces (Wu et al., 2020a; Xiao et al., 2020; Hindson, 2020; Tang et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020). Some studies demonstrated that the virus can replicate in cells that line the human digestive tract, and that a significant number of COVID-19 patients have detectable levels of viral RNA in their stool (Lescure et al., 2020; Wölfel et al., 2020; Foladori et al., 2020). In some cases, the number of viral gene copies in one gram of stool ranges from ~104 to 108 genomes (Lescure et al., 2020; Wölfel et al., 2020; Foladori et al., 2020). Even though the virus is detectable in the stool of COVID-19 patients, there is limited evidence that it is infectious, as only one study to date has demonstrated this to be the case, while another study demonstrated that it was not possible to isolate infectious viruses from the stool of COVID-19 patients (Lescure et al., 2020; Wölfel et al., 2020; Foladori et al., 2020). These findings indicate that SARS-CoV-2 could be detected in the municipal wastewater of a region containing infected individuals. Furthermore, it also means that monitoring the virus in municipal wastewater represents an effective low-cost method to track infections in the population.

Wastewater monitoring has been a successful method of tracking emerging contaminants and circulating antimicrobial/antibiotic resistance genes (Choi et al., 2018; Lorenzo and Picó, 2019; Mercan et al., 2019). Furthermore, monitoring different types of viruses, such as Hepatitis A, Noroviruses, and Rotavirus, in wastewater has also been used as a surveillance technique to investigate the distribution of these viruses in a community, a practice termed water-based epidemiology (WBE) (Hellmér et al., 2014; Santiso-Bellón et al., 2020). It is thus possible that WBE and the environmental surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater could help track the outbreak in a certain region and identify regions with infected asymptomatic individuals.

Carrying out SARS-CoV-2 testing to identify and quarantine affected individuals is a good strategy for managing this outbreak in countries with testing capabilities and capacities, and is the method used here in the UAE. However, it is a reactionary strategy that can only be deployed after a case is reported clinically, and by then it is likely that the virus has been spreading through a population at a significant level. In contrast, detecting and quantifying SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater covers a larger portion of the population as it essentially tests everyone who contributed to the wastewater sample analyzed (Messina, 2020; Mehrotra et al., n.d.). If successful, it would be a way of mass testing and could lead to early detection before infections manifest as clinical cases or hospital admissions. Recent peer-reviewed and non-peer-reviewed studies published by several groups in the Netherlands, the USA, France, Spain, Italy, Australia, and Turkey have demonstrated that the idea of tracking infection rates by measuring the viral load in wastewater is feasible, cost-effective, and efficient (Randazzo et al., 2020a; Hata and Honda, 2020; Ahmed et al., 2020; Mallapaty, 2020; Nemudryi et al., 2020). The authors believe that the viral concentration in wastewater is a good predictor of the number of infected individuals in the population of the United Arab Emirates (UAE), including asymptomatic cases that would otherwise remain undetected. Most importantly, monitoring wastewater could be used as a way of tracking the prevalence of the virus and become an early-warning tool for new outbreaks in the future. Consequently, the main objectives of this study were: (i) to detect the presence of SARS-CoV-2 virus in municipal (untreated) wastewater and treated effluents of wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) in the UAE; (ii) to quantify the viral concentration in viral gene copies per liter; and (iii) to explore whether these measurements mirror infections in the population in order to comment on the utility of this method to track the epidemiology of the disease. Thus far, the frequency and degree of testing individuals and wastewater samples achieved in the UAE have been replicated only in a few other jurisdictions. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to detect and quantify SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater in the region.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Wastewater and treated effluent sampling

Municipal wastewater samples were collected from different locations in the UAE (Fig. S1). The samples included influents and effluents of 11 WWTPs (Table 1), as well as influents from various sewer access points (e.g. manholes located in neighborhoods) and pumping stations. These 11 WWTPs implement a series of treatment technologies including preliminary, primary, secondary (ASP/clarification), and tertiary (sand filtration, disinfection, chlorination) for the purpose of reusing treated water (TSE) for irrigating farmland and watering green spaces. Composite samples were collected over a 24-hour period using auto-samplers, and 250 mL of the composite samples were transferred to ISOLAB GmbH sterile polypropylene (PP) plastic bottles, preserved on ice, and transported to the Center for Membranes and Advanced Water Technology (CMAT) at Khalifa University of Science and Technology (Abu Dhabi, UAE). Viruses were thermally deactivated by immersing the bottles in a 60 °C water bath (WiseBath®, Witeg Labortechnik GmbH, Germany) for 90 min (Wu et al., 2020b; Rabenau et al., 2005; Pastorino et al., 2020a). Although this inactivation step might lead to some viral loss, it is an essential safety measure that minimizes the risk of SARS-CoV-2 transmission to laboratory personnel. Studies have demonstrated that thermal deactivation at lower temperatures, similar to the one chosen in this study, resulted in a non-infectious virus that could still be detected by RT-PCR based methods, while deactivation at much higher temperatures (92 °C) resulted in complete degradation of the virus so that detection was not possible by RT-PCR (Pastorino et al., 2020a; Pastorino et al., 2020b). After heat inactivation, the samples cooled down to 4 °C prior to filtration and viral concentration.

Table 1.

WWTP codes and respective capacities.

| WWTP code | Capacity (m3/day)a |

|---|---|

| A1 WWTP | 2.30E+04 |

| B1 WWTP | 2.20E+05 |

| B2 WWTP | 2.28E+05 |

| B3 WWTP | 2.41E+05 |

| B4 WWTP | 5.22E+03 |

| B5 WWTP | 7.92E+04 |

| B6 WWTP | 9.53E+04 |

| C1 WWTP | 3.17E+04 |

| D1 WWTP | 1.39E+05 |

| E1 WWTP | 2.24E+05 |

| F1 WWTP | 1.13E+05 |

Average values for the days where the wastewater samples were collected.

2.2. Wastewater sample filtration and RNA concentration

Previously deactivated samples were filtered through 0.22 μm Millipore Express® PLUS 33 mm polyethersulfone (PES) Millex® sterile syringe filters or 0.22 μm polystyrene (PS) Millipore Sigma™ sterile vacuum bottle-top filters connected to WELCH 2546C-02A vacuum pump (Gardner Denver Thomas, Inc.). This initial filtration was conducted to remove sediments, large particles, and bacteria present in the wastewater samples. The viruses in the filtrate were then concentrated using one of two methods that were published in preprints at the time this study was initiated.

In the first method, a sub-sample of the filtrate (50 mL) was concentrated using 30 kDa molecular weight cutoff (MWCO) Ultra-30 Amicon™ polypropylene (PP) concentration/spin column (15 mL columns with 7.6 cm2 filtration area, MilliporeSigma™) to a final volume of 250 to 400 μL. The concentrated sample was then transferred to a sterile 1.5 mL tube and stored at −20 °C overnight before the RNA extraction was conducted the following day.

In the second method, 8000 average molecular weight polyethylene glycol (PEG) was used to concentrate the viruses (Wu et al., 2020b). Briefly, 50 mL of the filtrate was transferred to a 50 mL conical tube, followed by the addition of PEG and NaCl to a final concentration of 8 and 1.8%, respectively. The sample was mixed on a nutator for 1 h in order to dissolve the PEG and NaCl and precipitate viruses. The sample was then centrifuged at 12,000 ×g using a fixed angle rotor for 2 h at 4 °C. The supernatant was poured off and the pellet was re-suspended in 1.5 mL of TRIzol (ThermoFisher Cat#15596).

2.3. Viral RNA extraction and qPCR analysis

Viral RNA was purified from the concentrated samples using ABIOpure Viral DNA/RNA Extraction kits (Alliance Bio Inc., Cat#M561VT50) according to the manufacturer instructions. Internal extraction control RNA provided with the RT-qPCR kit was added to the samples before the RNA extraction in order to verify the successful extraction in case of a negative SARS-CoV-2 result. RNA was eluted in a final volume of 40 μL of elution buffer. The viral load in the samples was determined by RT-qPCR using GENESIG COVID-19 kits (Primerdesign Ltd., Cat#Z-Path-2019-nCoV) according to the manufacturer instructions. The kit uses proprietary primers and probes that are directed against the SARS-CoV-2 RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRP) gene. The qPCR kit specification sheet states that the detection limit of the kit is 0.58 copies/μL, where 8 μL of input is used in a 20 μL reaction.

An Alternative RNA extraction protocol using TRIzol was also performed. Briefly, 300 μL of chloroform was added to the 1.5 mL of TRIzol re-suspended pellet. The mixture was vortexed for 1 min and incubated at room temperature for 3 min. Samples were then centrifuged at 12,000 ×g for 10 min at 4 °C, and the top aqueous layer was transferred to a clean tube. Isopropanol (1 mL) was added to the aqueous layer and the mixture was agitated by inverting the tube before incubation at room temperature for 10 min. The RNA was pelleted by centrifugation at 12,000 ×g for 15 min at 4 °C and washed once in 75% ethanol prior to resuspension in elution buffer (40 μL) from the ABIOpure Viral DNA/RNA Extraction kit. The two protocols described for viral concentration and RNA extraction (either ultrafiltration columns/RNA extraction kit or PEG/TRIzol) were selected and tested because they were the two methods that were reported for this type of work at the time these experiments were initiated in early April 2020 (Wu et al., 2020b; Medema et al., 2020a). The authors wanted to compare them to decide which methodology to adopt as wastewater sampling continued. All the data reported in the tables were obtained using the ultrafiltration method (Fig. 1a).

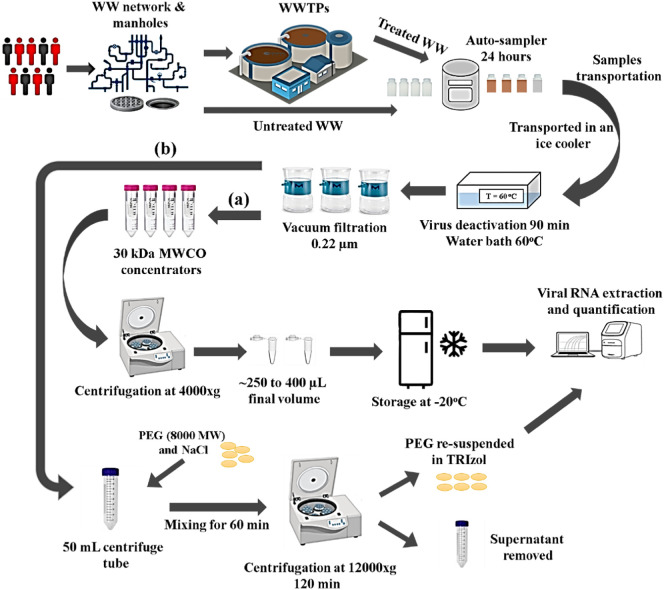

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the sample collection, virus deactivation, and RNA concentration and extraction (WWTPs: Wastewater treatment plants, WW: Wastewater) (a) viral concentration using ultrafiltration columns and (b) Viral concentration using PEG-mediated precipitation.

The extracted RNA (8 μL) was used as an input in 20 μL qPCR reactions in 96-well plates on the Viia™ 7 Real-Time instrument by Applied Biosystems. Elution buffer (8 μL) was used a negative control. Standard curves were established using positive control standards provided in the kit. These standard curves were used to determine quantities (in gene copies/μL) from the cycle threshold (CT) values determined for each sample. Internal RNA extraction controls provided with the qPCR kit verified that water samples that tested negative for SARS-CoV-2 were not false negatives due to the RNA extraction procedure. All samples were tested in triplicate and the average quantities were reported in viral gene copies/L ± standard deviation. The schematic presentation of the complete process (i.e., sample filtration, concentration, and RNA extraction) is illustrated in Fig. 1. The viral load (viral gene copies/L of wastewater) was determined (Eq. (1)):

| (1) |

2.4. Projected SARS-CoV-2 infection prevalence – Monte Carlo simulation

The prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in a certain region was estimated using the measured viral loads in wastewater, the wastewater flow rate, the viral load in the stool of infected individuals, and the estimated daily production of stool per capita according to Eq. (2) (Ahmed et al., 2020):

| (2) |

where,

NIF: Estimated number of infected people in a specific location.

RQ: Viral load in wastewater (viral gene copies/L).

Q: Wastewater flow rate (L/day).

RF: Viral load in the stool (viral gene copies/g stool).

F: Daily production of stool per capita (g stool/capita.day).

ɛ: % of COVID-19 patients who shed virus in their stool.

Monte Carlo simulation was performed using the Oracle Crystal Ball (Version 11.1.2.4.850 Oracle©) Excel add-on to account for the variability observed in some of the factors in Eq. (2). The wastewater flow rate (Q) was determined from flow readings reported at each location (i.e. average values over 24-h period). The stool viral load (RF) in log10 was simulated as a log-normal distribution with a mean of 7.18 and STDEV of 0.67 (Lescure et al., 2020). Daily stool production per capita (F) (g/capita.day) was simulated as a log-normal distribution with a mean of 149 and STDEV of 95 as per the statistics reported for the high-income countries (Rose et al., 2015). The percentage of COVID-19 patients who shed virus in their stool (ɛ) was modeled as a uniform distribution from 0.29 to 0.55, as reported by the limited number of studies on this topic thus far (Wu et al., 2020a; Wang et al., 2020; Cheung et al., 2020). The reported data from the simulations were based on 50,000 calculations.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Comparison between virus concentration and RNA extraction protocols

At the time when the authors initiated this study, only two studies were reported in non-peer-reviewed pre-prints; one study utilized ultra-concentration columns for viral concentration followed by RNA kit extraction, while the other study used PEG to concentrate viruses followed by TRIzol extraction (Wu et al., 2020b; La Rosa et al., 2020a). Therefore, in order to assess the differences between these two methods and determine which one to use for our study, viruses from the same wastewater samples (50 mL) were concentrated using either PEG followed by RNA extraction with TRIzol or using a 30 kDa MWCO column followed by extraction using a viral RNA kit as described in the materials and methods. Quantification of the viral load was then performed identically on the RNA extracted from each method using RT-qPCR.

Different methods for wastewater virus concentration have been adopted by different groups around the world (Ahmed et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2020b; La Rosa et al., 2020a). The methods fall into three major categories and involve concentrating viruses using either (i) precipitation using chemicals such as PEG or Al(OH)3, followed by centrifugation (Randazzo et al., 2020a; Wu et al., 2020b; Randazzo et al., 2020b; La Rosa et al., 2020b), (ii) ultrafiltration columns with very low molecular weight cut-offs (Ahmed et al., 2020; Nemudryi et al., 2020; Medema et al., 2020a), or (iii) binding of viruses to electronegative membranes (Ahmed et al., 2020; Haramoto et al., 2020).

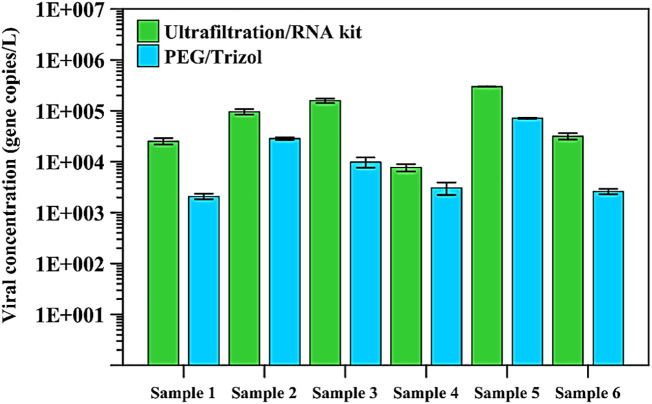

Using ultrafiltration columns in combination with the commercial RNA kits resulted in higher counts compared to using PEG and TRIzol (Fig. 2 ). Indeed, a reading of 31.7 gene copies/mL was determined using the ultrafiltration method compared to a reading of 2.6 gene copies/mL for the same sample using the PEG/TRIzol method. Consequently, all subsequent virus measurements in the wastewater samples were performed using the ultrafiltration and commercial RNA extraction kit method.

Fig. 2.

Viral load (average of triplicate measurements ± SD) in six SARS-CoV-2 positive wastewater samples determined by the two compared methods. ND – indicates a sample where no value could be determined because it is below the detection limit.

The PEG protocol tested here was used in the state of Massachusetts in late March 2020, with a significantly higher number of reported cases than what was reported in the UAE when the measurements reported here were performed. In the Massachusetts study, high counts ranging between 50 and 300 gene copies/mL were reported in the wastewater samples (Wu et al., 2020b). Precipitation-based methods that rely on chemicals such as PEG to concentrate viruses have a higher throughput since they are cheap and user-friendly compared to the expensive ultrafiltration column method that sometimes requires multiple rounds of centrifugation to concentrate the wastewater sample. However, using ultrafiltration columns in combination with commercial RNA extraction kits might represent a more sensitive approach, more suited to detecting lower concentrations of the virus in wastewater. The ultrafiltration method might be more appropriate for long term surveillance as well after the virus concentration drops below the detectable limit of the assay. Once that occurs, a more sensitive assay would be able to detect the resurgence of the virus sooner than a less sensitive method. More studies aimed at performing a comprehensive analysis of different virus concentration methods, including concentration using electronegative columns, which was not tested in this study. Those studies should also be performed using known virus concentration standards by research groups with access to Biosafety Level 3 facilities to cultivate the virus. These types of studies would conclusively determine the lower limits of detection in order to more precisely determine the sensitivity of these assays.

Both methods used have advantages and caveats (Ye et al., 2016). For example, one drawback of concentrating viruses using the ultrafiltration method is related to the fact that it is often difficult to concentrate all viruses from the sample, as some viruses are adsorbed to the solid phase in the wastewater sample and are thus pre-filtered when the sample is passed through the 0.2-μm filter. As more groups report the experimental protocols they used to make SARS-CoV-2 wastewater measurements, scientists need to come together to agree on standardizing the method used to perform this analysis. Whatever the method is chosen, there will always be a viral loss that results from different steps in the process. It is the author's opinion that the most important property of wastewater monitoring is sensitivity, reproducibility, precision, and not necessarily accuracy. At this point, the value of these measurements is to observe the change over time in order to gain insight into infection rates and kinetics in the population. Laboratories with access to BSL-3 labs will lead the way in determining which methods are best suited for this type of analysis in the future.

3.2. SARS-CoV-2 concentration in wastewater

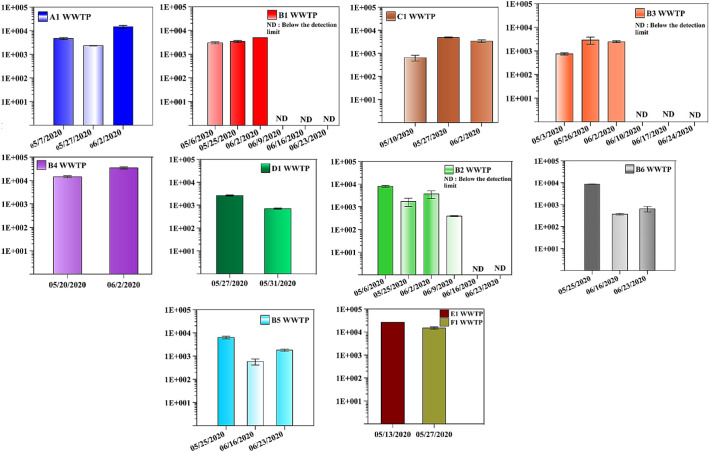

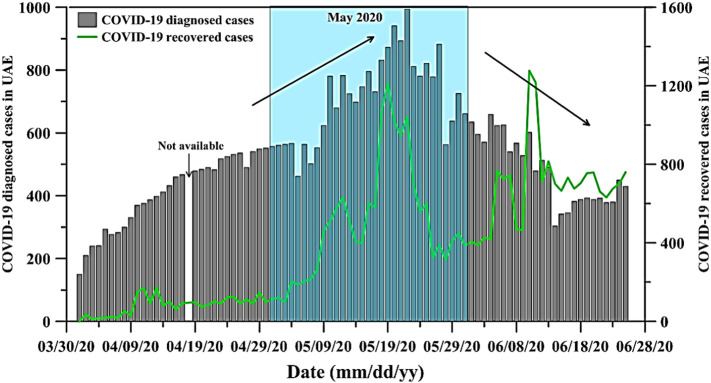

The viral loads in the 11 WWTPs and the 38 locations in the UAE are summarized in Fig. 3 and Table 2 , respectively. All 11 WWTPs' influents tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 on different dates (Fig. 3). Starting from early May 2020 and until early June 2020, 4 of the WWTPs (i.e. A1, B1, C1, and B3) showed a significant increase in SARS-CoV-2 viral load. For example, the viral load in A1 WWTP increased from 4.70E+03 ± 4.71E+02 gene copies/L on May 7th 2020 up to 1.48E+04 ± 2.09E+03 gene copies/L on June 2nd 2020 (Fig. 3). Similarly, B1 WWTP's influent had a viral load of 3.00E+03 ± 3.01E+02 gene copies/L on May 6th 2020 and 4.88E+03 ± 1.10E+01 gene copies/L on June 2nd 2020. The same trend was observed for the B4 WWTP starting from May 20th 2020 till June 2nd 2020 (Fig. 2). Conversely, D1 and B2 WWTPs showed a decrease in the viral load during the month of May 2020. For example, the viral load in the B2 WWTP's influent was 7.94E+03 ± 7.94E+02 gene copies/L on May 6th 2020 and decreased to 3.68E+03 ± 1.35E+03 gene copies/L on June 2nd 2020 (Fig. 3) whereas D1 WWTP viral load decreased from 2.61E+03 ± 1.46E+02 to 6.92E+02 ± 4.6E+01 between May 27th and May 31st 2020. During that same time, the number of SARS-CoV-2 diagnosed cases in the country increased as shown in Fig. 4 . The number of daily SARS-CoV-2 diagnosed cases during early May was approximately 550 patients, which increased to as high as 994 cases (May 22nd 2020). The fact that viral load numbers increased at some plants and went down in other plants indicated that tracking the epidemic through wastewater analyses could provide us with more comprehensive information than the total number of cases in the country. For example, the wastewater analyses of the B2 and D1 WWTPs suggested that these locations were most likely experiencing a decrease in the number of infected individuals, even while the country as a whole reported a higher number of cases. Taken together, these results reveal the great potential of these measurements to be used in monitoring any increase or decrease in infections for a specific geographical area. This was further validated by the significant reduction in SARS-CoV-2 viral load after the first quarter of June 2020. In fact, the wastewater viral loads were lower, as observed in the B1, B2, and B3 WWTPs, on June 9th, 10th, 16th, 17th, 23rd, and 24th 2020 (Fig. 3). This observation was in tune with the significant reduction in the number of daily diagnosed SARS-CoV-2 cases during the same period. In addition, there was a noticeable increase in the number of individuals that recovered from the SARS-CoV-2 in the UAE, as shown in Fig. 4.

Fig. 3.

Concentration profile of SARS-CoV-2 viral load in 11 WWTPs' influents in the UAE. X-axis: mm/dd/yy, y-axis: viral concentration (gene copies/L). ND – indicates a sample where no value could be determined because it is below the detection limit.

Table 2.

Concentration profile of SARS-CoV-2 viral load in 38 locations in the UAE during May and June 2020.

| Month | Location | Triplicate average viral concentrations (gene copies/L ± SD) |

|---|---|---|

| During May 2020 | Location 1 | 2.91E+04 ± 1.36E+02 |

| Location 2 | 2.90E+04 ± 1.20E+02 | |

| Location 3 | 2.78E+04 ± 4.66E+02 | |

| Location 4 | 2.72E+04 ± 1.08E+02 | |

| Location 5 | 1.64E+04 ± 1.03E+03 | |

| Location 6 | 7.43E+03 ± 8.26E+02 | |

| Location 7 | 5.79E+03 ± na | |

| Location 8 | 5.65E+03 ± na | |

| Location 9 | 3.54E+03 ± na | |

| Location 10 | 3.39E+03 ± na | |

| Location 11 | 2.11E+03 ± 2.94E+02 | |

| Location 12 | 1.84E+03 ± na | |

| Location 13 | 1.68E+03 ± na | |

| Location 14 | 1.49E+03 ± na | |

| Location 15 | 1.10E+03 ± na | |

| Location 16 | 7.78E+02 ± na | |

| Location 17 | 7.38E+02 ± na | |

| Location 18 | 5.70E+02 ± na | |

| Location 19 | 3.82E+02 ± 6.60E+01 | |

| Location 20 | 3.36E+02 ± 4.40E+01 | |

| Location 21 | 3.10E+02 ± 4.60E+01 | |

| Location 22 | 3.06E+02 ± na | |

| Location 23 | 2.12E+02 ± 4.20E+01 | |

| Location 24 | 1.90E+02 ± 4.00E+00 | |

| Location 25 | 1.06E+02 ± na | |

| Location 26 | ND | |

| During June 2020 | Location 27 | 2.23E+04 ± 5.59E+03 |

| Location 28 | 2.37E+03 ± 4.74E+02 | |

| Location 13 | 1.71E+03 ± 1.60E+01 | |

| Location 3 | 1.37E+03 ± 1.90E+02 | |

| Location 15 | 1.01E+03 ± 5.50E+01 | |

| Location 29 | 9.64E+02 ± 3.58E+02 | |

| Location 30 | 4.58E+02 ± 1.14E+02 | |

| Location 31 | 2.86E+02 ± 1.80E+01 | |

| Location 1 | ND | |

| Location 2 | ND | |

| Location 31 | ND | |

| Location 14 | ND | |

| Location 32 | ND | |

| Location 33 | ND | |

| Location 34 | ND | |

| Location 35 | ND | |

| Location 36 | ND | |

| Location 37 | ND | |

| Location 38 | ND |

na: not available.

ND – indicates a sample where no value could be determined because it is below the detection limit.

Fig. 4.

Number of SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) diagnosed patients (grey bars) and infected individuals that recovered in the UAE (green line) (U. National Emergency Crisis and Disaster Management Authority, 2020). (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Importantly, none of the 11 WWTPs' treated effluents tested positive during the entire sampling period. This indicates that the wastewater treatment technologies implemented in the UAE are efficient in the removal of SARS-CoV-2, and confirms the safety of the treated re-used water across the country. In addition to the viral load observations in the 11 sampled WWTPs, the viral loads in 38 locations distributed across the UAE were evaluated and the data are summarized in Table 2. The results were similar to what was determined for samples from the 11 WWTPs during the months of May and June.

SARS-CoV-2 detection and quantification in wastewater influents have the potential to aid in the surveillance of asymptomatic and mild unreported cases, predict a possible outbreak location, and shed light on the extent of virus spread at the community level. Studies have predicted that the considerable rise in the number of SARS-CoV-2 diagnosed cases might be preceded by an elevation of SARS-CoV-2 concentration in wastewaters (Wurtzer et al., 2020). Indeed, several studies have explored the detection and quantification of SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater influents (Ahmed et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2020b; Medema et al., 2020a; La Rosa et al., 2020b; Vallejo et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2020c; Medema et al., 2020b). However, only a few studies have attempted to establish a correlation between the increase/decrease in the viral load in the wastewater influents and the number of infected patients (Randazzo et al., 2020a; Ahmed et al., 2020; Wurtzer et al., 2020; Vallejo et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2020c). For example, a recent study in Paris (France) demonstrated a correlation between an observed increase in SARS-CoV-2 viral load in 3 WWTP influents and a significant increase in the number of SARS-CoV-2 diagnosed cases in the region (Wurtzer et al., 2020). Their findings reported a viral load of 5.00E+05 genome units/L on March 5th 2020 and a total of 91 COVID-19 cases in Paris. These values increased rapidly to concentrations as high as 3.00E+06 genome units/L on April 9th 2020 with thousands of total reported COVID-19 cases on the same day. Nonetheless, with the effective lockdown and precautionary measures taken, SARS-CoV-2 diagnosed cases and viral load in the WWTP's influents showed a moderate drop. This observation is very similar to what was observed in the UAE and reported in this study. The precautionary measures imposed by the UAE government, including applying restrictions on social activities and limiting movement among others, seem to have contributed to the reduction of COVID-19 reported cases and a drop in the observed wastewater viral loads. As of June 16th 2020, 346 new COVID-19 cases were reported in the UAE, which is less than those reported on the same day of the preceding month (U. National Emergency Crisis and Disaster Management Authority, 2020). In another study carried out in the Murcia Region (Spain), the epidemiological data on COVID-19 revealed a tight correlation between the virus prevalence (cases per 1.00E+05 inhabitants) and the viral load in the WWTP's influents. Their study also confirmed that SARS-CoV-2 could be detected weeks before the initial confirmed case (Randazzo et al., 2020a).

These studies, together with our findings, provide strong evidence for the significance of environmental epidemiological surveillance in monitoring SARS-CoV-2 outbreaks, and for this surveillance method to be used as an early warning tool for possible outbreaks or “second waves”. This tool can help decision-makers in developing appropriate policies to manage outbreaks in a certain area. It can also help evaluate the effectiveness of these policies in reducing the widespread transmission of the virus. Although mass testing of inhabitants for SARS-CoV-2 is an excellent option for assessing the virus prevalence, wastewater surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 viral loads can also be a good indicator of the circumstances on the ground and could direct the mass testing efforts to specific geographic locations.

In epidemiology, the reproduction number is the number of individuals an infected person interacts with and infects. This number can be significantly reduced through infection mitigating policies that a jurisdiction implements (Guzzetta et al., 2020; Cao et al., 2020). The first COVID-19 case in the UAE was reported on January 29th 2020, and that person later recovered on February 9th 2020. The UAE government implemented a policy to cancel major events on February 28th 2020, followed by closing down schools and suspending flights from major airports on March 3rd and 26th 2020, respectively. The authorities in the UAE launched the nationwide disinfection campaign on March 26th 2020, during which both transportation and people's movements in the evening (from 8:00 pm to 6:00 am) were restricted (Straits Times, 2020a; Straits Times, 2020b). The first 24-hour lockdown was imposed on a district which is located in Dubai Emirate and houses the Emirate's famous gold and spice markets on Tuesday, March 31st 2020 (Straits Times, 2020a). On April 5th, the UAE authorities announced a two-week complete lockdown and later extended this lockdown further in an attempt to contain the COVID-19 pandemic. The majority of public transportation services were suspended in addition to a gradual termination of flights and complete closure of public venues, including malls and restaurants. The authorities also instructed both the public and private sectors to implement remote working for most staff and employees. Door-to-door screening and testing in some areas where the number of infections was high, mainly in Abu Dhabi, were also conducted. In addition, several drive-through COVID-19 testing facilities were established in collaboration with the Abu Dhabi Health Services Company (SEHA). Implementing these measures correlated with a reduction in the daily reported cases and a flattening of the infection curve in the UAE.

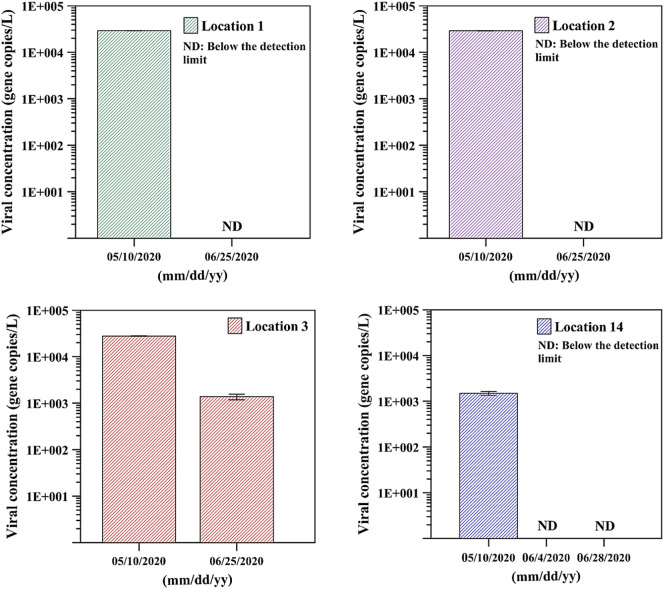

During this time that the curve was flattening, it was also observed that the measured viral load in wastewater also decreased. After the measures were implemented, cases kept on climbing until they peaked in May 2020. This observation was also mirrored by measurements of the viral load in wastewater. The possible impact of these measures was more obvious during June and July 2020. Indeed, as shown in Fig. 4, Fig. 5 , and Table 2, the viral load in wastewater was considerably higher in May 2020 in different locations across the UAE, which was in tune with the number of daily clinically diagnosed COVID-19 cases in the same month. However, during June 2020, the viral load in wastewater dropped below the detection limit of the assay, and no viral RNA was detected in many locations (Fig. 5). The number of COVID-19 patients was lower in June compared to May 2020. Indeed, in June there was a clear decrease in the number of daily diagnosed COVID-19 cases and an increase in the number of infected individuals that recovered (Fig. 4). Taken together, it seems that a correlation exists between the number of reported cases in the population and the viral load measured in wastewater.

Fig. 5.

Viral load in wastewater in four different locations across the UAE during May and June 2020. ND – indicates a sample where no value could be determined because it is below the detection limit.

3.3. SARS-CoV-2 estimated prevalence based on wastewater measurements

Several months after the virus outbreak, many countries still cannot carry out enough SARS-CoV-2 tests to identify and isolate infected individuals in order to curb the epidemic. What makes the situation even more complex is that a significant amount of viral transmission is attributed to asymptomatic infected individuals or individuals with very mild symptoms (Arnold and Heaney, 2020; John, 2020; Thacker, 2020). This also means that the number of actual infections is underestimated. Thus, augmenting testing strategies using wastewater epidemiology data represents a promising new tool in estimating prevalence in a given location.

Different conclusions can be drawn from the wastewater analyses depending on how the data is processed, essentially achieving different levels of insight into the outbreak. At the first level, viral concentration in the wastewater (gene copies/L) is not very helpful on its own, though it can give you a good overview of how an outbreak is progressing from sampling the same area over time. This assumes that the flow of water through the area does not change much between sampling dates and viral load can inform on whether the outbreak is getting better or worse.

Importantly, different areas cannot be compared to each other using this first metric only. For instance, the viral load in viral gene copies/L for B4 WWTP gives an indication that the region served by this WWTP is significantly more affected than the region served by B2 WWTP, which showed a lower viral load in gene copies/L. However, the conclusions are very different when reporting the viral flow rate in gene copies per day. Reporting the results this way informs on the viral load running through a location over a given period of time, in this case, 24 h (gene copies/day). This can be determined by multiplying the viral concentration in wastewater by the flow-through of the sampled location (volume of wastewater that passed through the location during the sampling period, a 24-h day for example). This second metric is expressed in viral gene copies/day and is more useful as it should correlate directly with the number of infected people. In other words, a higher genome per day value means more infected people have contributed to the wastewater sampled in this area. When looking at the viral load in viral gene copies/day in the B2 WWTP compared to B4 WWTP region, the situation is worse in the B2 WWTP region. It is important to stress that the viral gene copies per day metric cannot inform on the actual number of infected individuals at this time. It allows for a direct comparison of two locations in order to determine which location has the highest number of infected individuals without specifying how many people are infected. This is based on an assumption that all the variability between individuals with regards to mass of stool produced per day and the viral load in the stool is similar between different areas so that the variability is canceled out when comparing different areas.

At the third level, another metric, the viral flow rate per capita can be calculated. This number can be determined by dividing the second metric above by the population in the sampled area, expressed in viral gene copies/capita.day. This third metric can inform on the infection rate in the sampled location, in order to compare two areas with regards to the percent of infected people. Again, an actual percentage cannot be calculated, but a comparison between two sampled locations can be made and a conclusion regarding which area would result in a larger percentage of positive COVID-19 tests if individuals were tested can be reached by the population served by a given WWTP (i.e. population equivalents).

Despite the current significant limitations in estimating the possible number of infected individuals from wastewater data, an analysis was performed using Monte Carlo simulations in order to provide estimates of the possible number of infected individuals and the results are shown in Table 3 . As illustrated, the Monte Carlo simulation estimates the number of infected people in B1 region to be around 1.21E+04 ± 5.52E+03 with lower and upper estimates of 6.20E+02 and 2.22E+04 infections, respectively. Furthermore, comparing the results obtained via the Monte Carlo simulation for the B2 and B4 regions with the results in Fig. 5 showed that B2 region had higher estimates of the number of the infected individuals (9.70E+03 ± 4.42E+03 compared to 2.22E+03 ± 1.02E+03 in B4) despite the lower viral load in viral gene copies/L when related to the B4 region. This shows that the use of proper representation of the data is crucial in this type of environmental surveillance of SARS-CoV-2.

Table 3.

Estimation of the number of SARS-CoV-2 infections obtained via the viral gene copies detected in wastewater and Monte Carlo simulation.

| Location (mm/dd/yy) |

Viral load (triplicate average gene copies/L ± SD) | Estimated number of infections |

Skewness | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± STDEV | Median | 95% Confidence interval (CI) | ||||

| B1 (06/02/2020) | 4.88E03 ± 0.10E+02 | 1.21E+04 ± 5.52E+03 | 1.14E+04 | 6.20E+02 | 2.22E+04 | 0.6201 |

| B2 (06/02/2020) | 3.68E+03 ± 1.34E+03 | 9.69E+03 ± 4.42E+03 | 9.12E+03 | 6.71E+02 | 1.78E+04 | 0.6087 |

| B3 (06/02/2020) | 2.43E+03 ± 2.16E+02 | 7.49E+03 ± 3.45E+03 | 7.07E+03 | 4.71E+02 | 1.39E+04 | 0.6402 |

| B4 (06/02/2020) | 3.44E+04 ± 3.53E+03 | 2.21E+03 ± 1.02E+03 | 2.10E+03 | 7.20E+02 | 5.05E+03 | 0.6188 |

4. Conclusions

This comprehensive study reports the first detection and quantification of SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater in the UAE. The concentration of SARS-CoV-2 viral gene copies was carried out via ultrafiltration columns with very low molecular weight cut-offs and extracted using commercial RNA kits. SARS-CoV-2 RNA was detected in wastewater influents of 11 WWTPs as well as untreated wastewater samples from 38 various locations. The SARS-CoV-2 viral concentration in these WWTP influents and locations were monitored during May and June 2020. A correlation was observed between the number of clinically reported COVID-19 diagnosed cases in the UAE and the wastewater measurements reported here. One of the main challenges that remain unsettled is the accurate estimation of the number of infected individuals in a population-based on SARS-CoV-2 genome concentrations detected and quantified in wastewater. This study attempted to provide an estimate in different regions using the Monte Carlo approach and the results were reported with 95% CI based on the simulated variables. As more groups around the world report results and communicate laboratory protocols used to make these measurements, a comprehensive comparison needs to be carried out in order for scientists to agree on standardized methods. Overall, this study showed the potential of detecting SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater as an early warning and prediction tool for the spread of the disease. This monitoring can help authorities take appropriate and prompt actions to contain any potential outbreak of COVID-19 in their communities.

The following is the supplementary data related to this article.

UAE map, city population, and area (Base map was modified according to authorization from Wang Ning, ProBizDs Editable maps).

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Shadi W. Hasan: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - review & editing, Supervision, Validation. Yazan Ibrahim: Data curation, Writing - original draft, Investigation, Validation. Marianne Daou: Data curation, Writing - review & editing, Validation. Hussein Kannout: Data curation, Writing - review & editing, Validation. Nila Jan: Data curation, Writing - review & editing, Validation. Alvaro Lopes: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - review & editing, Validation. Habiba Alsafar: Methodology, Writing - review & editing, Supervision, Validation. Ahmed F. Yousef: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation, Writing - review & editing, Supervision, Validation.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to the Ministry of Interior (MOI) in Abu Dhabi (UAE) for their financial support (Award No. CPRA-2020-027), their immense efforts in coordination and bringing the teams at Khalifa University of Science and Technology (KU), Department of Energy (DOE) and Abu Dhabi Police (ADP) (Abu Dhabi – UAE) together in this successful collaboration. The collaborative efforts of the MOI, DOE and ADP under the umbrella of the National Emergency Crisis and Disaster Management Authority (NCEMA) in sample collection, handling and transportation are highly appreciated. We would also like to thank the Khalifa University Center for Membranes and Advanced Water Technology (CMAT), and the Center for Biotechnology (BTC). Finally, the contributions of Osama Alhamoudi, Aamer Alshehhi, Ismail Alhammadi, Ahmed Alafifi from ADP as well as Halawa Alshehhi, Malika Saif, Amna Alzaabi, Noora Taher from MOI are acknowledged.

Editor: Damia Barcelo

References

- Ahmed W., Angel N., Edson J., Bibby K., Bivins A., O’Brien J.W., Choi P.M., Kitajima M., Simpson S.L., Li J., Tscharke B., Verhagen R., Smith W.J.M., Zaugg J., Dierens L., Hugenholtz P., Thomas K.V., Mueller J.F. First confirmed detection of SARS-CoV-2 in untreated wastewater in Australia: a proof of concept for the wastewater surveillance of COVID-19 in the community. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;728:138764. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold A., Heaney K. WHO says asymptomatic COVID-19 transmission is ‘very rare,’ cut. 2020. https://www.thecut.com/2020/06/how-many-people-with-the-coronavirus-are-asymptomatic.html

- Cao Z., Zhang Q., Lu X., Pfeiffer D., Jia Z., Song H., Zeng D.D. Estimating the effective reproduction number of the 2019-nCoV in China. MedRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.01.27.20018952. 2020.01.27.20018952. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chang L., Yan Y., Wang L. Coronavirus disease 2019: coronaviruses and blood safety. Transfus. Med. Rev. 2020;S0887-7963(20):30014–30016. doi: 10.1016/j.tmrv.2020.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Li L. SARS-CoV-2: virus dynamics and host response. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020;20:515–516. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30235-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen N., Zhou M., Dong X., Qu J., Gong F., Han Y., Qiu Y., Wang J., Liu Y., Wei Y., Xia J., Yu T., Zhang X., Zhang L. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395:507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung K.S., Hung I.F.N., Chan P.P.Y., Lung K.C., Tso E., Liu R., Ng Y.Y., Chu M.Y., Chung T.W.H., Tam A.R., Yip C.C.Y., Leung K.-H., Fung A.Y.-F., Zhang R.R., Lin Y., Cheng H.M., Zhang A.J.X., To K.K.W., Chan K.-H., Yuen K.-Y., Leung W.K. 2020. Gastrointestinal Manifestations of SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Virus Load in Fecal Samples From a Hong Kong Cohort: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis, Gastroenterology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi P.M., Tscharke B.J., Donner E., O’Brien J.W., Grant S.C., Kaserzon S.L., Mackie R., O’Malley E., Crosbie N.D., Thomas K.V., Mueller J.F. Wastewater-based epidemiology biomarkers: past, present and future. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2018;105:453–469. doi: 10.1016/j.trac.2018.06.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Foladori P., Cutrupi F., Segata N., Manara S., Pinto F., Malpei F., Bruni L., La Rosa G. SARS-CoV-2 from faeces to wastewater treatment: what do we know? A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;743:140444. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzzetta G., Riccardo F., Marziano V., Poletti P., Trentini F., Bella A., Andrianou X., Del Manso M., Fabiani M., Bellino S. 2020. The Impact of a Nation-wide Lockdown on COVID-19 Transmissibility in Italy, ArXiv Prepr. [Google Scholar]

- Haramoto E., Malla B., Thakali O., Kitajima M. First environmental surveillance for the presence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in wastewater and river water in Japan. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;737:140405. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart O.E., Halden R.U. Computational analysis of SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19 surveillance by wastewater-based epidemiology locally and globally: feasibility, economy, opportunities and challenges. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;730:138875. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hata A., Honda R. Potential sensitivity of wastewater monitoring for SARS-CoV-2: comparison with norovirus cases. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020 doi: 10.1021/acs.est.0c02271. acs.est.0c02271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellmér M., Paxéus N., Magnius L., Enache L., Arnholm B., Johansson A., Bergström T., Norder H. Detection of pathogenic viruses in sewage provided early warnings of hepatitis a virus and norovirus outbreaks. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014;80:6771–6781. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01981-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hindson J. COVID-19: faecal–oral transmission? Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020;17:259. doi: 10.1038/s41575-020-0295-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John T. Iceland lab's Testing Suggests 50% of Coronavirus Cases Have no Symptoms, CNN. 2020. https://edition.cnn.com/2020/04/01/europe/iceland-testing-coronavirus-intl/index.html

- Kitajima M., Ahmed W., Bibby K., Carducci A., Gerba C.P., Hamilton K.A., Haramoto E., Rose J.B. SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater: state of the knowledge and research needs. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;139076 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Rosa G., Bonadonna L., Lucentini L., Kenmoe S., Suffredini E. Coronavirus in water environments: occurrence, persistence and concentration methods - a scoping review. Water Res. 2020;179:115899. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2020.115899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Rosa G., Iaconelli M., Mancini P., Bonanno Ferraro G., Veneri C., Bonadonna L., Lucentini L., Suffredini E. First detection of SARAS-CoV-2 in untreated wastewaters in Italy. MedRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.04.25.20079830. 2020.04.25.20079830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lescure F.-X., Bouadma L., Nguyen D., Parisey M., Wicky P.-H., Behillil S., Gaymard A., Bouscambert-Duchamp M., Donati F., Le Hingrat Q., Enouf V., Houhou-Fidouh N., Valette M., Mailles A., Lucet J.-C., Mentre F., Duval X., Descamps D., Malvy D., Timsit J.-F., Lina B., van-der- Werf S., Yazdanpanah Y. Clinical and virological data of the first cases of COVID-19 in Europe: a case series. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020;20:697–706. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30200-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo M., Picó Y. Wastewater-based epidemiology: current status and future prospects. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Heal. 2019;9:77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.coesh.2019.05.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mallapaty S. How sewage could reveal true scale of coronavirus outbreak. Nature. 2020;580:176–177. doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-00973-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medema G., Heijnen L., Elsinga G., Italiaander R., Brouwer A. Presence of SARS-coronavirus-2 in sewage. MedRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.03.29.20045880. 2020.03.29.20045880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medema G., Heijnen L., Elsinga G., Italiaander R., Brouwer A. Presence of SARS-Coronavirus-2 RNA in sewage and correlation with reported COVID-19 prevalence in the early stage of the epidemic in the Netherlands. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2020;7:511–516. doi: 10.1021/acs.estlett.0c00357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A. Mehrotra, D.A. Larsen, A.K. Jha, It's Time to Begin a National Wastewater Testing Program for Covid-19, (n.d.). https://www.statnews.com/2020/07/09/wastewater-testing-early-warning-covid-19-infection-communities/ (accessed August 20, 2020).

- Mercan S., Kuloglu M., Asicioglu F. Monitoring of illicit drug consumption via wastewater: development, challenges, and future aspects. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Heal. 2019;9:64–72. doi: 10.1016/j.coesh.2019.05.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Messina S. 2020. Monitoring Human Waste: A Non-Invasive Early Warning Tool, Voices Bioeth. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nemudryi A., Nemudraia A., Surya K., Wiegand T., Buyukyoruk M., Wilkinson R., Wiedenheft B. Temporal detection and phylogenetic assessment of SARS-CoV-2 in municipal wastewater. MedRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.04.15.20066746. 2020.04.15.20066746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastorino B., Touret F., Gilles M., de Lamballerie X., Charrel R.N. Heat inactivation of different types of SARS-CoV-2 samples: what protocols for biosafety, molecular detection and serological diagnostics? Viruses. 2020;12:735. doi: 10.3390/v12070735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastorino B., Touret F., Gilles M., de Lamballerie X., Charrel R.N. Evaluation of heating and chemical protocols for inactivating SARS-CoV-2. BioRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.04.11.036855. 2020.04.11.036855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabenau H.F., Cinatl J., Morgenstern B., Bauer G., Preiser W., Doerr H.W. Stability and inactivation of SARS coronavirus. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 2005;194:1–6. doi: 10.1007/s00430-004-0219-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randazzo W., Truchado P., Cuevas-Ferrando E., Simón P., Allende A., Sánchez G. SARS-CoV-2 RNA in wastewater anticipated COVID-19 occurrence in a low prevalence area. Water Res. 2020;181:115942. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2020.115942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randazzo W., Cuevas-Ferrando E., Sanjuán R., Domingo-Calap P., Sánchez G. Metropolitan wastewater analysis for COVID-19 epidemiological surveillance. SSRN Electron. J. 2020;113621 doi: 10.1101/2020.04.23.20076679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose C., Parker A., Jefferson B., Cartmell E. The characterization of feces and urine: a review of the literature to inform advanced treatment technology. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015;45:1827–1879. doi: 10.1080/10643389.2014.1000761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santiso-Bellón C., Randazzo W., Pérez-Cataluña A., Vila-Vicent S., Gozalbo-Rovira R., Muñoz C., Buesa J., Sanchez G., Díaz J.R. Epidemiological surveillance of norovirus and rotavirus in sewage (2016–2017) in Valencia (Spain) Microorganisms. 2020;8:458. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms8030458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straits Times UAE Imposes First Lockdown on Historic District to Slow Coronavirus. 2020. https://www.straitstimes.com/world/middle-east/uae-imposes-first-lockdown-on-historic-district-to-slow-coronavirus

- Straits Times Coronavirus: UAE to Clear Streets for Disinfection Drive. 2020. https://www.straitstimes.com/world/middle-east/coronavirus-uae-to-clear-streets-for-disinfection-drive-bahrain-evacuates-citizens Bahrain evacuates citizens.

- Tang A., Tong Z.D., Wang H.L., Dai Y.X., Li K.F., Liu J.N., Wu W.J., Yuan C., Yu M.L., Li P., Yan J.B. Detection of novel coronavirus by RT-PCR in stool specimen from asymptomatic child, China. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020;26:6. doi: 10.3201/eid2606.200301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thacker T. Econ; Times: 2020. No Symptoms in 80% of Covid Cases Raise Concerns.https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/industry/healthcare/biotech/healthcare/no-symptoms-in-80-of-covid-cases-raise-concerns/articleshow/75260387.cms [Google Scholar]

- U. National Emergency Crisis and Disaster Management Authority UAE Coronavirus (COVID-19) updates. 2020. https://covid19.ncema.gov.ae/en

- Vallejo J.A., Rumbo-Feal S., Conde-Perez K., Lopez-Oriona A., Tarrio J., Reif R., Ladra S., Rodino-Janeiro B.K., Nasser M., Cid A., Veiga M.C., Acevedo A., Lamora C., Bou G., Cao R., Poza M. Highly predictive regression model of active cases of COVID-19 in a population by screening wastewater viral load. MedRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.07.02.20144865. 2020.07.02.20144865. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W., Xu Y., Gao R., Lu R., Han K., Wu G., Tan W. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in different types of clinical specimens. JAMA. 2020;323:1843–1844. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wölfel R., Corman V.M., Guggemos W., Seilmaier M., Zange S., Müller M.A., Niemeyer D., Jones T.C., Vollmar P., Rothe C., Hoelscher M., Bleicker T., Brünink S., Schneider J., Ehmann R., Zwirglmaier K., Drosten C., Wendtner C. Virological assessment of hospitalized patients with COVID-2019. Nature. 2020;581:465–469. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2196-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) Consensus document on the epidemiology of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), Geneva. 2003. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/70863

- World Health Organization (WHO) Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) fact sheet. 2019. https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/middle-east-respiratory-syndrome-coronavirus-(mers-cov

- Wu Y., Guo C., Tang L., Hong Z., Zhou J., Dong X., Yin H., Xiao Q., Tang Y., Qu X., Kuang L., Fang X., Mishra N., Lu J., Shan H., Jiang G., Huang X. Prolonged presence of SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA in faecal samples. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020;5:434–435. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30083-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu F., Xiao A., Zhang J., Gu X., Lee W.L., Kauffman K., Hanage W., Matus M., Ghaeli N., Endo N., Duvallet C., Moniz K., Erickson T., Chai P., Thompson J., Alm E. SARS-CoV-2 titers in wastewater are higher than expected from clinically confirmed cases. MedRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.04.05.20051540. 2020.04.05.20051540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu F., Xiao A., Zhang J., Moniz K., Endo N., Armas F., Bonneau R., Brown M.A., Bushman M., Chai P.R., Duvallet C., Erickson T.B., Foppe K., Ghaeli N., Gu X., Hanage W.P., Huang K.H., Lee W.L., Matus M., McElroy K.A., Nagler J., Rhode S.F., Santillana M., Tucker J.A., Wuertz S., Zhao S., Thompson J., Alm E.J. SARS-CoV-2 titers in wastewater foreshadow dynamics and clinical presentation of new COVID-19 cases. MedRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.06.15.20117747. 2020.06.15.20117747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wurtzer S., Marechal V., Mouchel J.-M., Maday Y., Teyssou R., Richard E., Almayrac J.L., Moulin L. Evaluation of lockdown impact on SARS-CoV-2 dynamics through viral genome quantification in Paris wastewaters. MedRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.04.12.20062679. 2020.04.12.20062679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao F., Tang M., Zheng X., Liu Y., Li X., Shan H. Evidence for gastrointestinal infection of SARS-CoV-2. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:1831–1833. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.02.055. e3. 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.02.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y., Li X., Zhu B., Liang H., Fang C., Gong Y., Guo Q., Sun X., Zhao D., Shen J., Zhang H., Liu H., Xia H., Tang J., Zhang K., Gong S. Characteristics of pediatric SARS-CoV-2 infection and potential evidence for persistent fecal viral shedding. Nat. Med. 2020;26:502–505. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0817-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y., Peng F., Wang R., Guan K., Jiang T., Xu G., Sun J., Chang C. The deadly coronaviruses: the 2003 SARS pandemic and the 2020 novel coronavirus epidemic in China. J. Autoimmun. 2020;109:102434. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2020.102434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye Y., Ellenberg R.M., Graham K.E., Wigginton K.R. Survivability, partitioning, and recovery of enveloped viruses in untreated municipal wastewater. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016;50:5077–5085. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.6b00876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

UAE map, city population, and area (Base map was modified according to authorization from Wang Ning, ProBizDs Editable maps).