Abstract

Objective

This extension study of the Phase III, randomized, placebo-controlled Belimumab International SLE Study (BLISS)-52 and BLISS-76 studies allowed non-US patients with SLE to continue belimumab treatment, in order to evaluate its long-term safety and tolerability including organ damage accrual.

Methods

In this multicentre, long-term extension study (GlaxoSmithKline Study BEL112234) patients received i.v. belimumab every 4 weeks plus standard therapy. Adverse events (AEs) were assessed monthly and safety-associated laboratory parameters were assessed at regular intervals. Organ damage (SLICC/ACR Damage Index) was assessed every 48 weeks. The study continued until belimumab was commercially available, with a subsequent 8-week follow-up period.

Results

A total of 738 patients entered the extension study and 735/738 (99.6%) received one or more doses of belimumab. Annual incidence of AEs, including serious and severe AEs, remained stable or declined over time. Sixty-nine (9.4%) patients experienced an AE resulting in discontinuation of belimumab or withdrawal from the study. Eleven deaths occurred (and two during post-treatment follow-up), including one (cardiogenic shock) considered possibly related to belimumab. Laboratory parameters generally remained stable. The mean (s.d.) SLICC/ACR Damage Index score was 0.6 (1.02) at baseline (prior to the first dose of belimumab) and remained stable. At study year 8, 57/65 (87.7%) patients had no change in SLICC/ACR Damage Index score from baseline, indicating low organ damage accrual.

Conclusion

Belimumab displayed a stable safety profile with no new safety signals. There was minimal organ damage progression over 8 years.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov, https://clinicaltrials.gov, NCT00424476 (BLISS-52), NCT00410384 (BLISS-76), NCT00732940 (BEL112232), NCT00712933 (BEL112234).

Keywords: belimumab, long-term treatment, organ damage, safety, systemic lupus erythematosus

Rheumatology key messages

An open-label extension study in non-US patients with SLE demonstrated long-term belimumab safety.

No new safety concerns were observed with up to 8 years of belimumab treatment or follow-up.

Organ damage progression was minimal in patients with SLE, including those with high disease activity.

Introduction

SLE is a multisystem autoimmune disease associated with the presence of pathogenic autoantibodies and the overexpression of B cell-activating factor, formerly known as B-lymphocyte stimulator [1, 2]. Self-reactive antibodies mediate tissue damage in multiple organs [3], often in the form of acute flares [4], which if left untreated can lead to fatal complications, including renal failure [5].

SLE treatments include low-dose CS and antimalarial medications for mild disease, with high-dose CS and immunosuppressive medications for moderate-to-severe disease [6]. Although these treatments have improved the long-term survival for SLE [7], patients are at risk of developing irreversible organ damage due to high disease activity (HDA) [4, 8] and long-term use of CS and immunosuppressants [9–11]. Prevention of long-term organ damage is therefore a key unmet need in SLE.

Belimumab is a human IgG1-λ monoclonal antibody that binds soluble B-lymphocyte stimulator, a B cell survival factor. Belimumab inhibits the survival of B cells, including autoreactive B cells, and reduces their differentiation into Ig-producing plasma cells [12–14].

Belimumab efficacy vs placebo in adults with active, autoantibody-positive SLE receiving standard therapy (standard of care, SoC) has been demonstrated with s.c. [15] and i.v. [16–18] formulations over 52 [15, 17, 18] and 76 weeks [16]. Patients who completed Belimumab International SLE Study (BLISS)-52 (BEL110752; NCT00424476) [17] or BLISS-76 (BEL110751; NCT00410384) [16] were eligible to continue open-label treatment with belimumab i.v. in two long-term extension (LTE) studies: BEL112233 (NCT00724867) for patients within the USA and BEL112234 (NCT0071293) for those outside the USA.

We present the results of the BEL112234 LTE study, which evaluated belimumab safety and tolerability and assessed long-term organ damage accrual.

Methods

Study design

This was an open-label, multicentre, LTE study (BEL112234; NCT00712933) of belimumab i.v. (30 May 2008 to 9 December 2016) of non-US patients with SLE who completed BLISS-52 [17] or BLISS-76 [16] (supplementary Fig. S1, available at Rheumatology online). A Mexico National Amendment allowed enrolment of five patients from the 52-week belimumab s.c. study (BEL112232; NCT00732940) [15] still receiving treatment at the time of study termination. Key exclusion criteria included: clinical evidence of significant, unstable or uncontrolled, acute or chronic disease not due to SLE; having an adverse event (AE) in the Phase III study that could put the patient at undue risk; or development of any other disease, laboratory abnormality or condition rendering the patient unsuitable.

This study was designed to have a 48-week study year; therefore, the study years do not align with calendar years.

The first dose of belimumab must have been administered within 2–8 weeks after the last treatment dose in the parent studies. Patients who received 1 mg/kg belimumab i.v. in the parent studies received the same dose in the LTE study until marketing approval was obtained for 10 mg/kg belimumab i.v., at which time their dose was increased to 10 mg/kg. Placebo-treated patients in the parent study received 10 mg/kg belimumab i.v. throughout this extension study. Patients in BEL112232 crossed over to 10 mg/kg belimumab i.v. Patients received belimumab i.v. every 28 days over a 1-h period and continued existing SoC, adjusted as clinically appropriate. Study completion was defined as continuation in this extension study until belimumab became commercially available in the patient’s country.

Clinical sites remained blinded to treatment until results of the parent study were made public. The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki [19]. All sites maintained ethics committee and institutional review board approval, and all patients provided written informed consent.

Safety assessments

AEs and serious AEs (SAEs) were assessed at each visit and reported until 8 weeks after the last belimumab dose (follow-up visit). Laboratory evaluations, including haematology, chemistry, routine urinalysis, serum IgG and immunogenicity testing, occurred at regular intervals. Changes in CS dose (daily prednisone equivalent dose) were reported at weeks 24 and 48. The SLICC/ACR Damage Index (SDI) was assessed every 48 weeks and at exit visit [20]. A subgroup analysis was conducted in patients with HDA, defined as those who were anti-dsDNA positive (⩾30 IU/ml) and hypocomplementaemic [low complement (C) 3 (<0.9 g/l) and/or low C4 (<0.16 g/l)] at baseline. Patients were also analysed by subgroups of the Safety of Estrogens in Lupus Erythematosus National Assessment-SLEDAI (SELENA-SLEDAI) [21] to examine the impact of baseline disease severity on organ damage accrual. Because patients with SLE diagnosed in childhood are known to have more rapid organ damage accrual compared with patients diagnosed in adulthood [22], a post hoc subgroup analysis was conducted to evaluate SDI changes in patients aged <18 vs ⩾18 years at time of SLE diagnosis and having an SLE diagnosis <10 years. Additional post hoc subgroup analyses of SDI were conducted on categorical changes in SDI score (no change, +1, +2, +3) per yearly interval.

Data were not collected after the follow-up visit for patients who withdrew from treatment or the study.

Data analyses

Because this was an open-label extension study, no formal statistical hypothesis testing was performed and all analyses were exploratory. Safety analyses, including SDI scores, were performed using descriptive statistics. Continuous variables were summarized by mean (s.d.), median, 25th and 75th percentiles and minimum/maximum values. Categorical variables were summarized with frequency counts and percentages. AE data are presented by incidence (percentage of patients who reported one or more AE) and rate [events per 100 patient-years (PYs)]. Except for SDI (described below), missing data were not imputed. All data summaries and analyses were performed using SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). All analyses were conducted for the modified intent-to-treat population (mITT), defined as all patients who received one or more belimumab dose in the extension study.

Baseline was defined as the last available value prior to belimumab treatment initiation. For patients randomized to belimumab in the parent studies, baseline was defined as the last available assessment prior to first belimumab dose in the parent study. For patients randomized to placebo in the parent study, baseline was defined as the last assessment prior to the first belimumab dose in this extension study. This assignment of baseline was used to align years of belimumab exposure between patients originally randomized to belimumab and those originally randomized to placebo in the parent studies.

Baseline SDI included extension study day 0 values for placebo-treated patients in the parent study and the last pre-treatment value in the parent study for patients originally treated with belimumab. Because SDI should never decrease, an item level reduction was replaced by carrying forward the worst (highest) observation (WOCF). The SDI total score utilized WOCF-imputed items.

Results

Study population

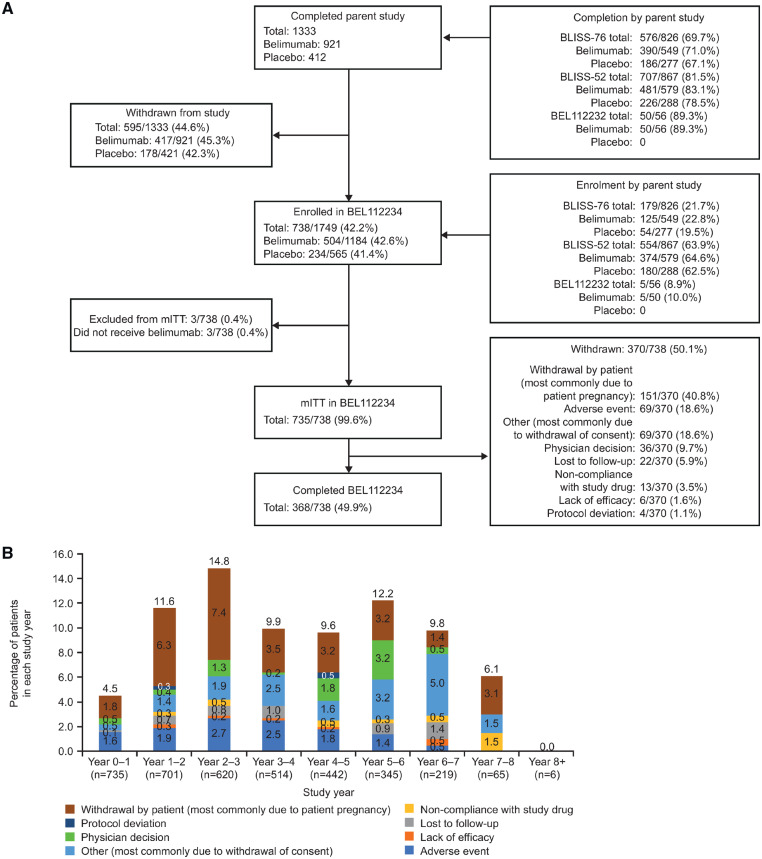

Overall, 738 patients entered the extension study to receive belimumab treatment (Fig. 1A), of whom 735 (99.6%) received one or more belimumab dose (mITT); 368/738 (49.9%) completed the study and 370/738 (50.1%) withdrew (Fig. 1A). Patient self-withdrawal (n = 151, 40.8%, most commonly due to patient pregnancy or planning for pregnancy), AEs (n = 69, 18.6%) and ‘other’ (n = 69, 18.6%) were the most common reasons for withdrawal (Fig. 1A;supplementary Table S1, available at Rheumatology online). The percentage of patients who withdrew from the study did not exceed 15% in any given study year (Fig. 1B). The study continued for 8 years for a total belimumab exposure of 3352 PYs.

Fig. 1.

Patient recruitment and attrition

Patient disposition (A) and withdrawals per study year (B) of the six patients who were reported as withdrawing due to lack of efficacy; details are only available for three patients. These patients were withdrawn by their physicians due to disease flare ups.

Patient demographics and baseline characteristics are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient demographics and baseline characteristics in mITT population

| Demographic/baseline characteristics | Total (N = 735) |

|---|---|

| Female, n (%) | 695 (94.6) |

| Age, mean (s.d.), years | 37.2 (11.2) |

| Age at diagnosis, n (%) | |

| ≥18 years | 554 (75.4) |

| <18 years | 32 (4.4) |

| Missing | 149 (20.3) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |

| Hispanic or Latino | 315 (42.9) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 420 (57.1) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| Black or African American/African heritage | 18 (2.4) |

| Native American or Alaska Native | 225 (30.6) |

| Asian | 214 (29.1) |

| White | 278 (37.8) |

| Mixed race | 2 (0.3) |

| Median SLE disease duration, years (min, max) | 4.5 (0, 37) |

| BILAG of SLE clinics organ domain involvement, n (%)a | |

| ≥1A or 2B | 324 (44.1) |

| ≥1A | 107 (14.6) |

| ≥2B | 531 (72.2) |

| No A or B | 171 (23.3) |

| SELENA-SLEDAI category, n (%) | |

| ≤9 | 446 (60.7) |

| ≥10 | 284 (38.6) |

| Missing | 5 (0.7) |

| SELENA-SLEDAI, mean (s.d.)b | 8.3 (4.3)c |

| ≥1 SELENA-SLEDAI flare index flare, n (%)d | 107 (14.6) |

| ≥1 severe SELENA-SLEDAI flare index flare, n (%)d | 4 (0.5) |

| Physician’s Global Assessment score, mean (s.d.) | 1.19 (0.6) |

| SDI score, mean (s.d.) | 0.6 (1.0)e |

| SDI category, n (%) | |

| 0 | 461 (62.7) |

| ≥1 | 267 (36.3) |

| Missing | 7 (1.0) |

| Concomitant medication, n (%)a | |

| Antimalarials | 474 (64.5) |

| Immunosuppressants | 323 (43.9) |

| CS | 690 (93.9) |

| Average daily prednisone dose, n (%)f | |

| 0 | 43 (5.9) |

| ≤7.5 mg/day | 227 (30.9) |

| >7.5 mg/day to ≤40 mg/day | 462 (62.9) |

| >40 mg/day | 1 (0.1) |

| Missing | 2 (0.3) |

| Complement (C) level, n (%) | |

| Low C3 (<0.9 g/l) and/or low C4 (<0.16 g/l) | 488 (66.4) |

| Anti-dsDNA | |

| Positive (≥30 IU/ml), n (%) | 528 (71.8) |

| Mean (s.d.), IU/ml | 140.5 (62.4) |

| ANA | |

| Positive (≥80 titre), n (%) | 683 (93.6)c |

| Mean (s.d.) | 838.1 (485.3) |

| IgG, n (%) | |

| <Lower limit of normal (6.94 g/l) | 6 (0.8) |

| >Upper limit of normal (16.18 g/l) | 334 (45.4) |

May be counted in more than one category.

SELENA-SLEDAI scored differently in Study BEL112232: category not assigned for these patients.

Data missing for n = 5.

Duration of assessment was the duration between the last two visits within the parent study (placebo-treated patients), or between screening and day 0 in the parent study (belimumab-treated patients).

Data missing for n = 7.

CS dose converted to daily prednisone equivalent. mITT: modified intent-to-treat population; SDI: SLICC/ACR Damage Index; SELENA-SLEDAI: Safety of Estrogens In Lupus Erythematosus National Assessment-SLEDAI.

Demographics and baseline characteristics in the HDA subpopulation (n = 404, 55.0% of mITT) were comparable to those of the mITT population, except for complement levels and anti-dsDNA positivity (supplementary Table S2, available at Rheumatology online).

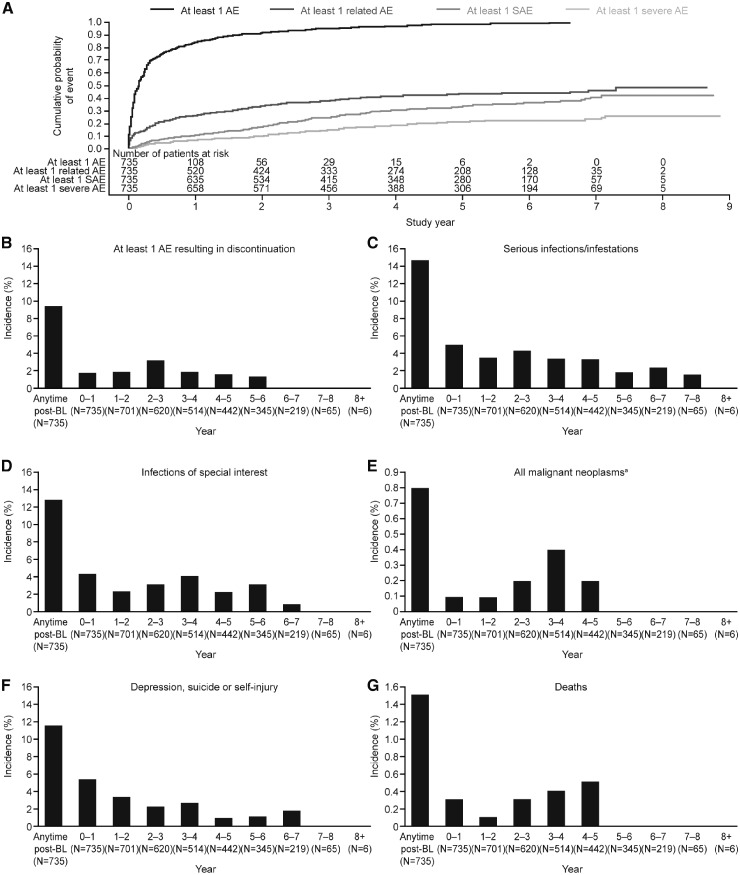

Adverse events

Overall, 706 (96.1%) patients experienced one or more AE (supplementary Table S3, available at Rheumatology online; Fig. 2) and 299 (40.7%) experienced an AE considered at least possibly related to belimumab treatment. The incidence of related AEs generally declined over the study period, from 26.4% in study year 0–1 to 6.2% in study year 7–8 (supplementary Table S3, available at Rheumatology online). Throughout the study, the annual AE incidence, including SAEs and severe AEs, remained stable or declined over time (supplementary Table S3, available at Rheumatology online); most AEs were mild or moderate in severity. According to incidence, the five most frequent AEs were headache (n = 205, 27.9%), nasopharyngitis (n = 155, 21.1%), diarrhoea (n = 143, 19.5%), arthralgia (n = 136, 18.5%) and influenza (n = 134, 18.2%) (supplementary Table S4, available at Rheumatology online). The most frequent AEs (occurring in ⩾10% of patients at any time post-baseline) either declined or stabilized over time, except for bacterial urinary tract infections, viral upper respiratory tract infections, cough and nasopharyngitis, which increased through study year 2–3 before stabilizing or decreasing from thereon (supplementary Table S4, available at Rheumatology online). The overall AE incidence in the HDA subpopulation was comparable to that in the mITT population: 389 (96.3%) patients experienced one or more AE and 167 (41.3%) experienced an AE considered at least possibly related to belimumab treatment. Myalgia (10.1%) and nausea (10.1%) were among the most frequent AEs within the HDA population in addition to those observed in the overall population.

Fig. 2.

Cumulative AE incidence over time

AE: adverse event; SAE: serious AE. aExcept non-melanoma skin cancer.

A severe (Grade 3 or 4) AE was experienced by 18.8% of patients, declining annually from 6.9% at study year 0–1 to 3.1% at study year 7–8 (supplementary Table S5, available at Rheumatology online). Thrombocytopaenia (1.1%) and lupus nephritis (1.0%) were the most frequently occurring severe AEs.

A total of 69 (9.4%) patients experienced one or more AE resulting in permanent belimumab discontinuation or withdrawal from the study (supplementary Table S3, available at Rheumatology online). Those occurring in two or more patients included lupus nephritis (n = 4, 0.5%), drug eruption, dyspnoea, bacterial pneumonia, pulmonary tuberculosis (cases occurred in Taiwan and the Philippines, where background incidence is high), SLE rash and urticaria, each experienced in two (0.3%) patients. Most patients who withdrew from the study because of an AE did so during the first 3 study years and none withdrew because of an AE beyond study year 5–6 (supplementary Table S3, available at Rheumatology online).

In the HDA subpopulation, 43 (10.6%) patients experienced one or more AE that resulted in permanent belimumab discontinuation or withdrawal from the study. Of these, the only AEs experienced by more than one patient were dyspnoea and pulmonary tuberculosis, each occurring in two (0.5%) patients. The incidence of remaining AEs resulting in discontinuation or withdrawal was 0.2%.

Within the mITT population, a total of 506 SAEs were reported by 231 (31.4%) patients. Of the most commonly reported SAEs (bacterial pneumonia, n = 14, 1.9%; lupus nephritis, n = 12, 1.6%; cellulitis, n = 12, 1.6%), none occurred in >2% of patients. SAEs were reported in 133 (32.9%) patients in the HDA subpopulation and the most frequently reported were lupus nephritis and bacterial pneumonia [each with seven (1.7%) patients].

During the study, 11 deaths (1.5% of patients) occurred (ischaemic stroke, cardiac arrest, bacterial pneumonia, acute pancreatitis, cardiogenic shock, sepsis, pneumonia, septic shock, thrombotic thrombocytopaenic purpura, pulmonary haemorrhage, respiratory distress), of which 7 were in the HDA population. An additional two deaths (intracranial haemorrhage and sepsis) occurred >8 weeks after the patients’ last belimumab dose. One death caused by cardiogenic shock (following a complication during surgery to repair a traumatic left tibial fracture in a patient with underlying pulmonary hypertension who developed intraoperative oxygen desaturation) was considered by the investigator as possibly related to belimumab. All other deaths were considered as not/probably not related by the investigator.

AEs of special interest

Eight (1.1%) patients experienced malignancies, including stage 0 cervical carcinoma (n = 2), non-melanoma skin cancer (n = 2), ductal breast carcinoma (n = 1), papillary thyroid cancer (n = 1), rectal adenocarcinoma (n = 1) and rectal cancer (n = 1). Incidence of malignancy (excluding non-melanoma skin cancer) was generally consistent across study years, peaking at study year 3–4 with two (0.4%) patients (supplementary Table S3, available at Rheumatology online). No malignancies were reported after study year 4–5.

Overall, 95 (12.9%) patients developed an infection of special interest including all potential and actual opportunistic infections as per GlaxoSmithKline adjudication (n = 12), tuberculosis (n = 4), herpes zoster (n = 63) and sepsis (n = 12). The incidence of infections of special interest was low, peaking at 4.4% in study year 0–1 and decreasing to 0.9% by study year 6–7, with none reported in study year 7–8 (supplementary Table S3, available at Rheumatology online).

Depression (including mood disorders), suicide and/or self-injury were reported in 86 (11.7%) patients, with incidence decreasing over the course of the study (supplementary Table S3, available at Rheumatology online). Most depression-related events (94.9%) were non-serious; serious depression was reported in four (0.5%) patients. A total of three suicidality/self-injury events (0.4%) occurred, all of which were serious (two suicide attempts and one suicidal ideation). There were no completed suicides.

Clinical and laboratory parameters

The incidence of Grade 3 and 4 haematology parameters, clinical parameters and urinalysis and IgG are displayed in supplementary Table S5, available at Rheumatology online. The only haematological parameter graded severe for ⩾10% of patients was lymphocyte count, in which 120 (23.9%) and 11 (2.2%) patients had Grade 3 or 4 severity, respectively. Of the 11 patients who had a Grade 4 lymphocyte value (none of whom had decreased IgG levels), 6 experienced a mild, non-serious, non-opportunistic infection and 1 experienced a serious infection (hepatitis A, classified as life-threatening and probably not related to study drug) within 30 days of observing the Grade 4 value. The percentage of patients with severe values for other haematology parameters did not exceed 5% during any given study year and the percentage of patients with severe values for liver function, electrolytes and other chemistry parameters did not exceed 3% in any given study year. Six (0.8%) patients had a Grade 3 or 4 IgG value and all six patients shifted from Grade 0 at baseline. Two of the six patients experienced a mild, non-serious, non-opportunistic infection within 30 days of observing the Grade 3 or 4 IgG value and none experienced a serious or severe infection.

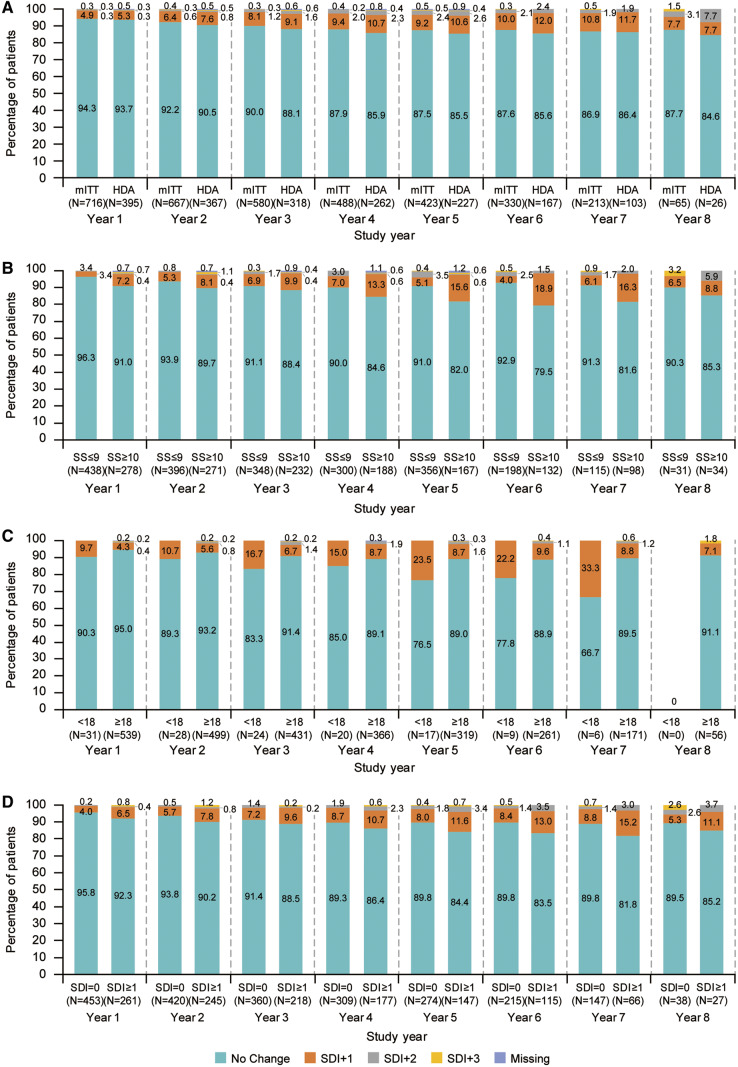

SDI

The mean (s.d.) SDI score in the mITT population was 0.6 (1.02) at baseline and remained stable, with 0.2 (0.56) mean change from baseline in SDI score at study year 8. By study year 8, 57/65 patients (87.7%) experienced no change in SDI score (Fig. 3A). The baseline SDI score in the HDA population was 0.6 (0.95), with mean change from baseline at study year 8 of 0.2 (0.59). By study year 8, 22/26 patients (84.6%) with HDA experienced no change in SDI score (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

Percentage of patients with SDI changes at week 48 of each study year

Analyses are categorized by: (A) mITT and HDA populations, (B) baseline SELENA-SLEDAI score ≤9 or ≥10, (C) age at disease onset <18 or ≥18 years and (D) baseline SDI score 0 or ≥1. Data labels denote the number of patients in each group. HDA: high disease activity; mITT: modified intent-to-treat population; SDI: SLICC/ACR Damage Index; SELENA-SLEDAI: Safety of Estrogens In Lupus Erythematosus National Assessment-SLEDAI.

For SDI score by organ involvement, only the musculoskeletal organ system showed any change from baseline [mean (s.d.)], with an increase of 0.1 (0.24) at study year 8.

Baseline SDI scores were 0.6 (0.95) and 0.7 (1.13) in SELENA-SLEDAI ⩽9 and ⩾10 subgroups, respectively. Most patients within both subgroups experienced no change in SDI score throughout the study (Fig. 3B). The percentage of patients in the SELENA-SLEDAI ⩽9 subgroup who experienced no SDI worsening was ⩾90% per study year, whereas among the SELENA-SLEDAI ⩾10 subgroup, the percentage of patients with no worsening in SDI was slightly lower per study year, only exceeding 90% in study year 1. Baseline mean (s.d.) SDI scores in patients aged <18 and ⩾18 years at diagnosis were 0.5 (0.84) and 0.5 (0.85), respectively. While most patients in both subgroups experienced no SDI worsening, the proportion who did have SDI worsening was higher in patients aged <18 years at diagnosis, compared with older patients (Fig. 3C). Among patients with worsening, more in the ⩾18 years subgroup experienced SDI increases of +2 or +3, compared with those in the <18 years subgroup, who experienced SDI increases of +1 only. Furthermore, most patients in the subgroup analysis by SDI scores of 0 and ⩾1 at baseline experienced no SDI change [mean (s.d.) baseline score: 0 and 1.6 (1.08), respectively] (Fig. 3D).

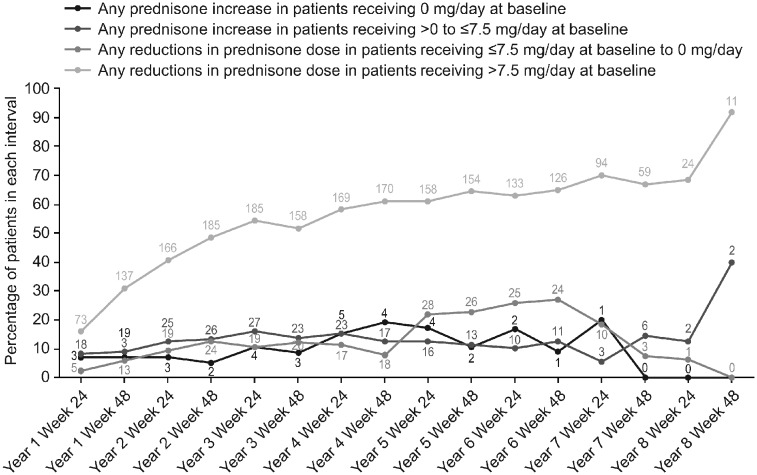

Steroid use

The percentage of patients with baseline prednisone dose >7.5 mg/day experiencing a reduction in prednisone dose increased or was maintained over time [study year 1, 136/442 patients (30.8%); study year 7, 59/87 patients (67.8%)]. A very low number of patients with baseline dose >0 to ⩽7.5 mg/day had an increase in prednisone dose [study year 1, 19/212 patients (8.9%); study year 7, 6/41 patients (14.6%)] (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Percentage of patients experiencing any change in prednisone dose from baseline

Lines and data labels indicate percentage and number of patients, respectively, who required a change in baseline prednisone dose at each time point.

Discussion

In this LTE study of belimumab i.v., the incidences of AEs, severe AEs, SAEs and AEs of special interest in the mITT and HDA populations were similar and generally remained stable or declined over time. No clinically relevant findings were noted regarding the rate of AEs, SAEs and AEs of special interest over the 8 years of belimumab exposure.

Overall, the incidences of AEs, SAEs and AEs of special interest leading to discontinuation were broadly similar to those of the belimumab Phase II continuation study; both studies showed a peak in AEs and SAEs at study year 1 and subsequent stabilization or decline through the remainder of the studies [23]. AE incidence was higher in the Phase II continuation study; however, duration of follow-up was longer in the continuation study and patients were slightly older at study entry (mean age 43 vs 37 years) and had a slightly longer disease duration (mean 8.8 vs 6.3 years), as well as a higher mean SELENA-SLEDAI (9.2 vs 8.3) compared with patients in this extension study [23]. The Phase II continuation study reported upper respiratory tract infections as the most frequent AE, whereas headache was the most frequently reported AE in this study and incidence of infections was low. Cellulitis and pneumonia were among the most frequently reported SAEs in both studies [23].

The mortality rate observed in this study was 0.3/100 PYs, which compares favourably with that reported in patients with SLE (1.6/100 PYs) [24] and is similar to that reported in the 7-year interim analysis of the Phase II long-term continuation study (0.4/100 PYs) [23]. Although the incidence of psychiatric events was greater with belimumab compared with placebo in the parent studies [16, 17], the incidence of depression (including mood disorders) and suicidality/self-injury decreased over the course of this LTE study, suggesting there is no further concern associated with longer-term use of belimumab.

The overall rate of malignant neoplasms excluding non-melanoma skin cancer in this study was 0.2/100 PYs, which compares favourably with a background rate in patients with SLE of 0.53/100 PYs and a rate of 0.7/100 PYs observed in the Phase II continuation study [23, 25]. The only haematologic parameter for which ⩾10% of patients had either a Grade 3 or 4 value was lymphocyte count. This is expected for the study population, whose SLE disease activity, immunosuppressant and CS use are likely contributing factors.

An exception to the trend of generally declining incidences and rates of SAEs over the study duration was observed in study year 2–3. Severe AEs also increased in this time interval vs the previous interval. However, further evaluation at the preferred term level identified no concerns. Furthermore, the incidence of SAEs and severe AEs subsequently declined for the remainder of the study.

Organ damage accrual was low, with mean (s.d.) SDI change from baseline of 0.2 (0.56) in the mITT population at study year 8 and this was similar in the HDA subpopulation. The mean SDI increase from baseline in this study was generally smaller than in other SLE cohorts [26–29]. However, differences exist between these studies, including their duration and inclusion/exclusion criteria; the observational cohorts included a full spectrum of patients with SLE, whereas the BLISS parent studies excluded patients with severe lupus nephritis and central nervous system disease [16, 17]. Both manifestations may be associated with higher rates of organ damage accrual and exclusion of these patients likely led to lower rates of damage within this extension study than might otherwise have been observed. The steroid-sparing effect of belimumab, previously demonstrated within a pooled BLISS-52 and BLISS-76 analysis [30], may also explain the low rate of organ damage in this study.

Disease activity can affect the risk of future organ damage [28]. In this study, most patients in both SELENA-SLEDAI subgroups experienced no change in SDI, although in all study years more patients in the SELENA-SLEDAI ⩽9 subgroup had no change in SDI vs the ⩾10 subgroup. More patients without organ damage at baseline also had no change in SDI compared with those with an SDI score ⩾1. Bruce et al. hypothesized that although patients with previous organ damage accrual would generally be at greater risk of further damage than patients without prior affliction, exposure to belimumab (plus SoC) may attenuate such damage within at-risk populations [30].

Patients with childhood-onset SLE accrue organ damage earlier in the course of their disease compared with those with adult-onset SLE [22]. Although this study did not include patients aged <18 years, analysis by age at diagnosis showed that a higher proportion of patients aged ⩾18 years at diagnosis experienced no SDI worsening compared with younger patients.

A numerically greater percentage of patients experienced reductions in their daily prednisone dose to ⩽7.5 mg/day, vs those who increased their prednisone dose to >7.5 mg/day. Although there was no placebo comparator, these results provide further evidence of the steroid-sparing effect of belimumab.

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting these data. First, this LTE study had no placebo control group. Second, 41.1% of the mITT population initially received placebo within the parent BLISS studies; these patients may have had low disease activity and have been less likely to experience SDI progression, given that they maintained stable disease while receiving placebo plus SoC during the parent study. In addition, the impact of study withdrawals may have created responder bias.

The accumulation of PYs within this LTE study represents an opportunity to gather information relating to the long-term safety and tolerability of belimumab and further understand its safety profile. This study provides further evidence that belimumab is well tolerated as an add-on therapy to SoC in the treatment of SLE. No new safety concerns were revealed and the study provides evidence to alleviate concerns regarding suicidality and the potential increased risk of developing malignancies while receiving belimumab. This study also demonstrated minimal organ damage progression within the study population including the HDA subpopulation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

All authors were involved in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, and all authors approved the final version to be published. R.F.v.V. had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. B.J. and D.R. were responsible for study conception and design. R.F.v.V., S.V.N. and R.A.L. were responsible for the acquisition of data. R.F.v.V., S.V.N., R.A.L., M.T., A.H., A.A., B.J., M.-L.W., T.L., J.F. and D.R. were responsible for the analysis and interpretation of data. Medical writing assistance was provided by Emma Hargreaves, MA, and Katie White, PhD, of Fishawack Indicia Ltd, UK, and was funded by GlaxoSmithKline (GSK). GSK funded the study and medical writing assistance provided by Fishawack Indicia Ltd, UK. GSK designed, conducted and funded the study, contributed to the collection, analysis and interpretation of the data and supported the authors in the development of the manuscript. All authors, including those employed by GSK, approved the content of the submitted manuscript. GSK is committed to publicly disclosing the results of GSK-sponsored clinical research that evaluates GSK medicines and, as such, was involved in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Funding: The study was funded by GSK.

Disclosure statement: R.F.v.V., S.V.N. and M.T. have received consulting fees and research support from GSK. R.A.L., B.J., and D.R. and are employed by GSK and own stock or stock options in GSK. T.L., J.F., M.-L.W. A.H. and A.A. were employed by GSK and owned stock or stock options in GSK at the time of the study.

References

- 1. Zhang J, Roschke V, Baker KP. et al. Cutting edge: a role for B lymphocyte stimulator in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Immunol 2001;166:6–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Arbuckle MR, McClain MT, Rubertone MV. et al. Development of autoantibodies before the clinical onset of systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med 2003;349:1526–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Diamond B, Bloom O, Al Abed Y. et al. Moving towards a cure: blocking pathogenic antibodies in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Intern Med 2011;269:36–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fernandez D, Kirou KA.. What causes lupus flares? Curr Rheumatol Rep 2016;18:14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kyttaris VC. Systemic lupus erythematosus: from genes to organ damage. Methods Mol Biol 2010:662:265–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yildirim-Toruner C, Diamond B.. Current and novel therapeutics in the treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2011;127:303–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lateef A, Petri M.. Unmet medical needs in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Res Ther 2012;14:S4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Stoll T, Sutcliffe N, Mach J, Klaghofer R, Isenberg D.. Analysis of the relationship between disease activity and damage in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus—a 5-yr prospective study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2004;43:1039–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Al Sawah S, Zhang X, Zhu B. et al. Effect of corticosteroid use by dose on the risk of developing organ damage over time in systemic lupus erythematosus—the Hopkins Lupus Cohort. Lupus. Sci Med 2015;2:e000066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zonana‐Nacach A, Barr SG, Magder LS, Petri M.. Damage in systemic lupus erythematosus and its association with corticosteroids. Arthritis Rheum 2000;43:1801–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Oglesby A, Shaul A, Pokora T. et al. Adverse event burden, resource use, and costs associated with immunosuppressant medications for the treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus: a systematic literature review. Int J Rheumatol 2013;2013:347520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Frieri M, Heuser W, Bliss J.. Efficacy of novel monoclonal antibody belimumab in the treatment of lupus nephritis. J Pharmacol Pharmacother 2015;6:71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Vincent FB, Morand EF, Schneider P, Mackay F.. The BAFF/APRIL system in SLE pathogenesis. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2014;10:365–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Baker KP, Edwards BM, Main SH. et al. Generation and characterization of LymphoStat‐B, a human monoclonal antibody that antagonizes the bioactivities of B lymphocyte stimulator. Arthritis Rheum 2003;48:3253–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Stohl W, Schwarting A, Okada M. et al. Efficacy and safety of subcutaneous belimumab in systemic lupus erythematosus: a fifty‐two-week randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study. Arthritis Rheumatol 2017;69:1016–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Furie R, Petri M, Zamani O. et al. A phase III, randomized, placebo‐controlled study of belimumab, a monoclonal antibody that inhibits B lymphocyte stimulator, in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 2011;63:3918–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Navarra SV, Guzmán RM, Gallacher AE. et al. Efficacy and safety of belimumab in patients with active systemic lupus erythematosus: a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2011;377:721–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zhang F, Bae SC, Bass D. et al. A pivotal phase III, randomised, placebo-controlled study of belimumab in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus located in China, Japan and South Korea. Ann Rheum Dis 2018;77:355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Medical Association. WMA Declaration of Helsinki—Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects 2013. https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-research-involving-human-subjects/ (27 June 2019, date last accessed). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20. Gladman DD, Goldsmith CH, Urowitz MB. et al. The Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics/American College of Rheumatology (SLICC/ACR) Damage Index for systemic lupus erythematosus international comparison. J Rheumatol 2000;27:373–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Petri M, Kim MY, Kalunian KC. et al. Combined oral contraceptives in women with systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med 2005;353:2550–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gutiérrez‐Suárez R, Ruperto N, Gastaldi R. et al. A proposal for a pediatric version of the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics/American College of Rheumatology Damage Index based on the analysis of 1,015 patients with juvenile‐onset systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:2989–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ginzler EM, Wallace DJ, Merrill JT. et al. Disease control and safety of belimumab plus standard therapy over 7 years in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol 2014;41:300–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bernatsky S, Boivin JF, Joseph L. et al. Mortality in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheumatol 2006;54:2550–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bernatsky S, Boivin J, Joseph L. et al. An international cohort study of cancer in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 2005;52:1481–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Alarcon G, Roseman J, McGwin G Jr. et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus in three ethnic groups. XX. Damage as a predictor of further damage. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2003;43:202–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Becker-Merok A, Nossent HC.. Damage accumulation in systemic lupus erythematosus and its relation to disease activity and mortality. J Rheumatol 2006;33:1570–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bruce IN, O’Keeffe AG, Farewell V. et al. Factors associated with damage accrual in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: results from the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics (SLICC) Inception Cohort. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:1706–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sutton EJ, Davidson JE, Bruce IN.. The Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics (SLICC) Damage Index: a systematic literature review. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2013;43:352–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bruce I, Urowitz M, Van Vollenhoven R. et al. Long-term organ damage accrual and safety in patients with SLE treated with belimumab plus standard of care. Lupus 2016;25:699–709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.