Abstract

STUDY QUESTION

How has the timing of women’s reproductive events (including ages at menarche, first birth, and natural menopause, and the number of children) changed across birth years, racial/ethnic groups and educational levels?

SUMMARY ANSWER

Women who were born in recent generations (1970–84 vs before 1930) or those who with higher education levels had menarche a year earlier, experienced a higher prevalence of nulliparity and had their first child at a later age.

WHAT IS KNOWN ALREADY

The timing of key reproductive events, such as menarche and menopause, is not only indicative of current health status but is linked to the risk of adverse hormone-related health outcomes in later life. Variations of reproductive indices across different birth years, race/ethnicity and socioeconomic positions have not been described comprehensively.

STUDY DESIGN, SIZE, DURATION

Individual-level data from 23 observational studies that contributed to the International Collaboration for a Life Course Approach to Reproductive Health and Chronic Disease Events (InterLACE) consortium were included.

PARTICIPANTS/MATERIALS, SETTING, METHODS

Altogether 505 147 women were included. Overall estimates for reproductive indices were obtained using a two-stage process: individual-level data from each study were analysed separately using generalised linear models. These estimates were then combined using random-effects meta-analyses.

MAIN RESULTS AND THE ROLE OF CHANCE

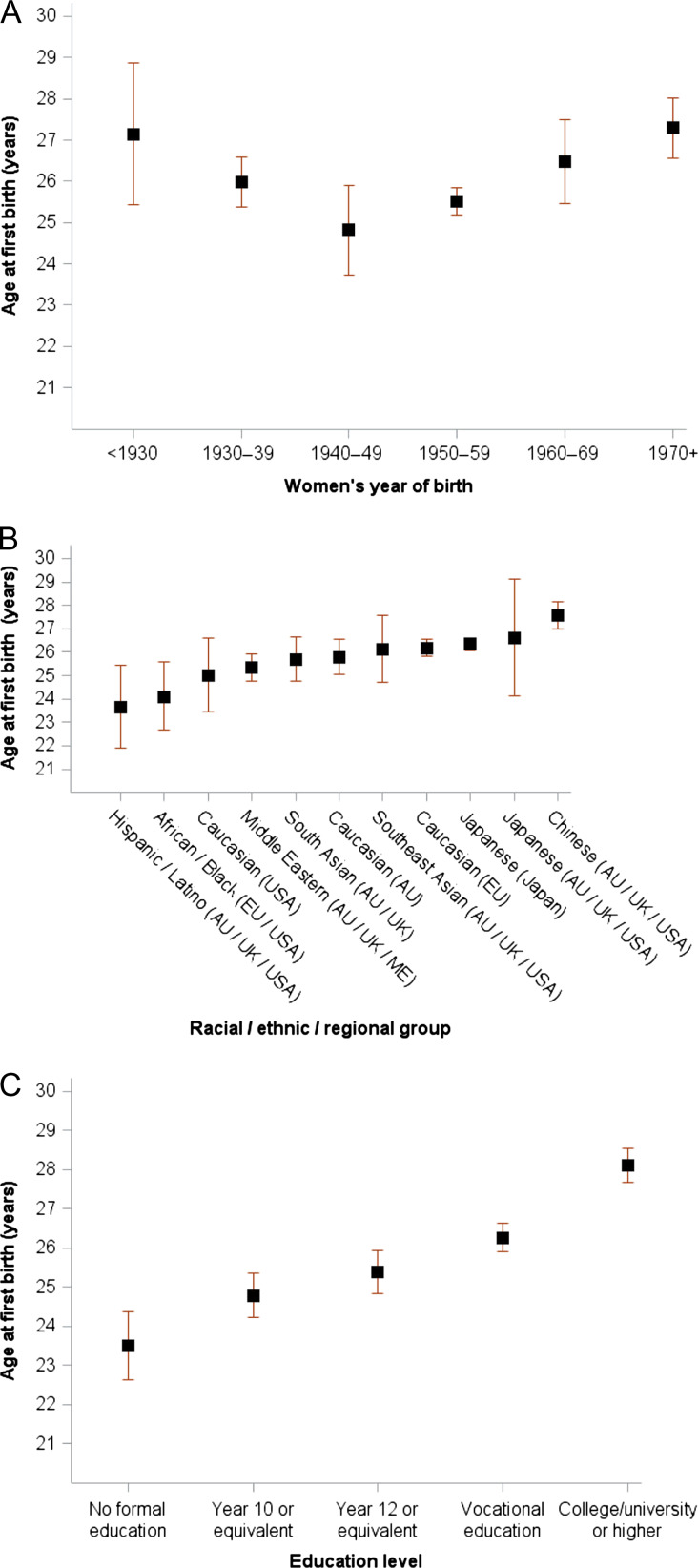

Mean ages were 12.9 years at menarche, 25.7 years at first birth, and 50.5 years at natural menopause, with significant between-study heterogeneity (I2 > 99%). A linear trend was observed across birth year for mean age at menarche, with women born from 1970 to 1984 having menarche one year earlier (12.6 years) than women born before 1930 (13.5 years) (P for trend = 0.0014). The prevalence of nulliparity rose progressively from 14% of women born from 1940–49 to 22% of women born 1970–84 (P = 0.003); similarly, the mean age at first birth rose from 24.8 to 27.3 years (P = 0.0016). Women with higher education levels had fewer children, later first birth, and later menopause than women with lower education levels. After adjusting for birth year and education level, substantial variation was present for all reproductive events across racial/ethnic/regional groups (all P values < 0.005).

LIMITATIONS, REASONS FOR CAUTION

Variations of study design, data collection methods, and sample selection across studies, as well as retrospectively reported age at menarche, age at first birth may cause some bias.

WIDER IMPLICATIONS OF THE FINDINGS

This global consortium study found robust evidence on variations in reproductive indices for women born in the 20th century that appear to have both biological and social origins.

STUDY FUNDING/COMPETING INTEREST(S)

InterLACE project is funded by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council project grant (APP1027196). GDM is supported by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council Principal Research Fellowship (APP1121844).

Keywords: reproductive events, age at menarche, first birth, age at menopause, number of children

Introduction

Reproductive health is integral to women’s overall health and wellbeing and has consequences over the life course. The timing of key reproductive events, such as menarche and menopause, is not only indicative of current health status but is linked to the risk of adverse hormone-related health outcomes in later life, including breast cancer, endometrial cancer, type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease (Atsma et al., 2006; Parkin, 2011; Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer, 2012; Brand et al., 2013; Charalampopoulos et al., 2014; Janghorbani et al., 2014; Muka et al., 2017). Identifying key variations in the occurrence and timing of reproductive events across and within populations assists with understanding the impact of socioeconomic changes (e.g. cohort effects and socioeconomic disparities) as well as cultural/environmental exposures and genetic effects (e.g. race/ethnicity and residential country) on women and has implications for the provision of health services and preventive health strategies.

A previous World Health Organisation (WHO) multicentre hospital-based study, and meta-analyses of community-based studies, concluded that a typical woman had menarche at age 14, her first birth at 22, and reached natural menopause at age 49–50 years, with a substantial international variation in the timing of these events (Morabia and Costanza, 1998; Thomas et al., 2001; Schoenaker et al., 2014). Variations across birth years indicate that age at menarche is declining and that more recent generations have delayed childbirth (Hosokawa et al., 2012; Mathews and Hamilton, 2016; Morris et al., 2011), but such trends have not been demonstrated consistently across countries (Juul et al., 2006; Rubin et al., 2009). Available studies of women with complete reproductive histories have lacked data on racial/ethnic diversity, as well as comparative data across cohorts. Socioeconomic differentials are also evident for parity, age at first birth, and possibly age at menopause; however, the degree and significance of these differentials vary from country to country according to its level of economic development, and within each country from generation to generation of women (dos Santos Silva and Beral, 1997).

The International Collaboration for a Life Course Approach to Reproductive Health and Chronic Disease Events (InterLACE) has pooled individual-level data from 10 countries. This global consortium provides unparalleled statistical power and comparative information on reproductive events across birth years and diverse racial/ethnic groups. Our objective was to describe the variability in the occurrence and timing of women’s reproductive events (including age at menarche, first birth, and natural menopause, and the number of children) within and between study populations as well as by birth year, racial/ethnic/regional groups, and education level. If there are substantial variations by these factors, it may point to the potential role of cohort effects, cultural/environmental exposures and genetic effects, and other influences such as secular trends in education level over time.

Materials and Methods

Ethical approval

Participants in each of the included studies were recruited and provided consent according to the approved protocols of the Institutional Review Board or the Human Research Ethics Committee at each relevant institution.

Study populations

InterLACE has brought together a total of 25 observational studies of women’s health, of which eight are cross-sectional, and 17 include longitudinal data. Detailed descriptions of the InterLACE collaboration, the included studies and the harmonisation process to combine data at the individual-level have been published previously (Mishra et al., 2013, 2016). Briefly, observational studies, which had collected prospective or retrospective survey data on women’s reproductive health across the lifespan (such as ages at menarche, first birth, and natural menopause), sociodemographic and lifestyle factors, and chronic disease events, could contribute data to the InterLACE consortium, regardless of the sample size and ethnic background of participants. Each study contributed individual-level data. Key variables were harmonised into the simplest level of detail that would incorporate information from as many as studies as possible. Overall, anonymised data from over 537 000 women were pooled from Australia (n = 53 299), Europe (n = 427 089, including UK n = 343 155), USA (n = 5444), Middle-East (n = 597), and Japan (n = 50 774).

Of the 25 studies, the San Francisco Midlife Women’s Health Study (n = 347) and the Japanese Midlife Women’s Health Study (n = 847) were excluded as data on age at menarche and/or age at natural menopause are not currently available, with 23 studies included in the present study. Around 6% of the women (n = 30 862) who did not have data on both age at menarche and age at natural menopause were excluded, leaving 505 147 women for the pooled analyses (Table I). The analysis sample for each reproductive marker was different depending on whether the events had occurred or not and was further adjusted for relevant covariates, including birth year, race/ethnicity/region, education level, smoking status and BMI. The percentages of women with missing covariate data were relatively small (<3%).

Table I.

Study-specific characteristics on age at baseline, age at last follow-up and women’s year of birth for 23 studies included in the InterLACE Consortium (N = 505 147).

| Age at baseline | Age at last follow-up* | Women’s year of birth | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <1930 | 1930–39 | 1940–49 | 1950–59 | 1960–69 | ≥1970 | |||||

| Study | Country | N | Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) |

| Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health (ALSWH 1946–51) | Australia | 12 223 | 47.6 (46.3, 48.9) | 63.6 (62.1, 65.3) | N/A | N/A | 9041 (74.0) | 3182 (26.0) | N/A | N/A |

| Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health (ALSWH 1973–78) | Australia | 9585 | 39.6# (38.4, 40.9) | 39.6 (38.4, 40.9) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 9585 (100) |

| Healthy Aging of Women Study (HOW) | Australia | 520 | 55.0 (53.0, 57.0) | 62.0 (60.0, 65.5) | N/A | N/A | 460 (88.5) | 60 (11.5) | N/A | N/A |

| Melbourne Collaborative Cohort Study (MCCS) | Australia | 24 423 | 55.2 (47.6, 62.4) | 64.4 (56.9, 71.1) | 6006 (24.6) | 8247 (33.8) | 7744 (31.7) | 2425 (9.9) | 1 (0.0) | N/A |

| Danish Nurse Cohort Study (DNCS) | Denmark | 28 573 | 50.0 (47.0, 58.0) | 63.0 (49.0, 70.0) | 4085 (14.3) | 7561 (26.5) | 10 278 (36.0) | 6649 (23.3) | N/A | N/A |

| Women’s Lifestyle and Health Study (WLHS) | Sweden | 48 691 | 40.0 (35.0, 45.0) | 48.0 (43.0, 54.0) | N/A | N/A | 19 531 (40.1) | 23 883 (49.1) | 5277 (10.8) | N/A |

| French Three-City Study (French 3 C) | France | 4255 | 73.9 (69.9, 78.3) | 73.9 (69.9, 78.3) | 3071 (72.2) | 1184 (27.8) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| MRC National Survey of Health and Development (NSHD) | UK | 1898 | 47.0# (47.0, 47.0) | 54.0 (54.0, 54.0) | N/A | N/A | 1898 (100) | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| National Child Development Study (NCDS) | UK | 6752 | 50.0# (50.0, 50.0) | 55.0 (55.0, 55.0) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 6752 (100) | N/A | N/A |

| 1970 British Cohort Study (BCS70) | UK | 3468 | 42.0# (42.0, 42.0) | 42.0 (42.0, 42.0) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 3468 (100) |

| English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA) | UK | 6364 | 57.0 (51.0, 66.0) | 65.0 (58.0, 74.0) | 861 (13.5) | 1411 (22.2) | 2059 (32.4) | 1858 (29.2) | 162 (2.5) | 13 (0.2) |

| UK Women’s Cohort Study (UKWCS) | UK | 34 771 | 51.0 (44.7, 59.4) | 53.5 (46.8, 61.9) | 2937 (8.4) | 8032 (23.1) | 12 515 (36.0) | 11 067 (31.8) | 219 (0.6) | 1 (0.0) |

| Whitehall II Study (WHITEHALL) | UK | 1779 | 47.0 (41.0, 52.0) | 63.8 (59.0, 69.6) | 1 (0.1) | 909 (51.1) | 762 (42.8) | 107 (6.0) | N/A | N/A |

| Southall And Brent Revisited (SABRE) | UK | 485 | 57.0 (53.0, 60.0) | 61.0 (56.0, 72.0) | 97 (20.0) | 324 (66.8) | 64 (13.2) | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Hilo Women’s Health Study (HILO) | USA | 975 | 51.0 (46.1, 55.6) | 51.0 (46.1, 55.6) | N/A | 3 (0.3) | 262 (26.9) | 507 (52.0) | 203 (20.8) | N/A |

| Study of Women’s Health across the Nation (SWAN) | USA | 3284 | 46.0 (44.0, 48.0) | 54.0 (52.0, 57.0) | N/A | N/A | 1302 (39.6) | 1982 (60.4) | N/A | N/A |

| Seattle Midlife Women’s Health Study (SMWHS) | USA | 507 | 41.2 (38.0, 44.4) | 44.8 (40.2, 49.7) | N/A | 23 (4.5) | 227 (44.8) | 257 (50.7) | N/A | N/A |

| Decisions at Menopause Study (DAMES–USA) | USA | 293 | 50.0 (48.0, 53.0) | 50.0 (48.0, 53.0) | N/A | N/A | 109 (37.2) | 184 (62.8) | N/A | N/A |

| Decisions at Menopause Study (DAME–Lebanon) | Lebanon | 298 | 50.0 (48.0, 53.0) | 50.0 (48.0, 53.0) | N/A | N/A | 231 (77.5) | 67 (22.5) | N/A | N/A |

| Decisions at Menopause Study (DAMES–Spain) | Spain | 298 | 50.0 (47.0, 53.0) | 50.0 (47.0, 53.0) | N/A | N/A | 87 (29.2) | 211 (70.8) | N/A | N/A |

| Decisions at Menopause Study (DAMES–Morocco) | Morocco | 273 | 49.0 (46.0, 52.0) | 49.0 (46.0, 52.0) | N/A | N/A | 143 (52.4) | 130 (47.6) | N/A | N/A |

| Japanese Nurses’ Health Study (JNHS) | Japan | 47 745 | 42.0 (36.0, 48.0) | 42.0 (36.0, 48.0) | 1 (0.0) | 118 (0.2) | 4993 (10.5) | 15 979 (33.5) | 20 457 (42.8) | 6197 (13.0) |

| UK Biobank (UK Biobank) | UK | 267 687 | 58.0 (50.0, 63.0) | 58.0 (50.0, 63.0) | N/A | 9012 (3.4) | 113 913 (42.6) | 89 372 (33.4) | 55 306 (20.7) | 84 (0.0) |

| Overall | 505 147 | 52.0 (45.0, 61.0) | 55.0 (47.0, 63.0) | 17 059 (3.4) | 36 824 (7.3) | 185 619 (36.7) | 164 672 (32.6) | 81 625 (16.2) | 19 348 (3.8) | |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; N/A, not applicable.

*Age at last follow-up was only based on the data availability to the International Collaboration for a Life Course Approach to Reproductive Health and Chronic Disease Events (InterLACE) consortium.

# ALSWH 1973–78 cohort was first surveyed in 1996 (age 18–23) and was followed every 3–4 years until 2015 (age 37–42). Information on age at menarche was collected in 2000, and fertility history was collected at regular follow-ups. The current study included 9585 women who had available data on age at menarche or had participated in the midlife survey in 2015 and used their midlife age as baseline age. NSHD (1946 British Birth Cohort) and NCDS (1958 British Birth Cohort) collected prospective information on age at menarche and fertility history at regular follow-ups. In NSHD, age of menopause was collected first in 1989 (age 43), annually 47–54 years and at 60–64 years. In NCDS, information on age of menopause was obtained in 2008 (age 50). These survey years around midlife (age 47 and age 50, respectively) were therefore used as baseline. Similarly, for the BCS70 (1970 British Cohort study), we included 3468 women who had completed the latest survey in 2012 and used age 42 as baseline age.

Reproductive events

Questions on reproductive events were conceptually similar across studies, although the exact wording differed. Information on age at menarche, age at first birth (live birth), and parity (number of children or live births) were collected prospectively in three British birth cohort studies (MRC National Survey of Health and Development, National Child Development Study, and 1970 British Cohort Study), but were retrospectively assessed in all other studies. Information on age at menopause was obtained prospectively where possible. Age at natural menopause was defined as the age at the final menstrual period (confirmed after 12 months of cessation of menses) and was distinct from the cessation of menses due to radiation treatment, bilateral oophorectomy, or hysterectomy. When age at natural menopause was reported at multiple surveys in longitudinal studies, the response to the last available survey was used to ensure the final menstrual age was identified (Mishra et al., 2016).

Factors assessed for variability

Variability in reproductive events was assessed according to women’s year of birth, racial/ethnic/regional groups, and education levels. Birth year ranged from 1900 to 1984 and was categorised as born before 1930, 1930–39, 1940–49, 1950–59, 1960–69 and 1970 onwards. Race/ethnicity was derived from self-identified racial/ethnic background reported in 13 studies. For the remaining studies, race/ethnicity was defined based on the reported country of birth, the language spoken at home, or the country where the study was conducted (residency) (Mishra et al., 2016). For instance, although InterLACE currently has no studies from China, a group of women – who were categorised as Chinese as per above – were Chinese living or born in Australia (AU), UK and USA. Accordingly racial/ethnic/regional groups were identified as Caucasian (AU), Caucasian (Europe), Caucasian (USA), African/Black (Europe/USA), Japanese (AU/UK/USA – only nine Japanese from AU), Japanese (Japan), Chinese (AU/UK/USA), South Asian (AU/UK), Southeast Asian (AU/UK/USA), Middle Eastern (AU/UK/Middle East – one-third from AU/UK), Hispanic/Latino (AU/UK/USA), and Other (including Aboriginal, Pacific Islander, Native American, Hawaiian and mixed) (Mishra et al., 2016). Education level was harmonised as no formal education, year 10 or equivalent, year 12 or equivalent, trade/certificate/diploma or vocational education, and college/university or higher.

Statistical analysis

Although individual participant data were available for all studies, it was not possible to use multilevel mixed models to obtain aggregate estimates across the studies because the data were very unbalanced. For example, all participants in some studies were born in the same decade, or in other studies, all participants belonged to the same racial/ethnic/regional group. Instead, a two-stage method of analysis was used.

In the first stage, the data from each study were analysed separately, using relevant design weights if available (Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health 1946–51 and 1973–78 cohorts) and appropriate generalised linear models. In each study, the crude mean ages at menarche, first birth, and natural menopause were estimated, and further stratified by birth year, race/ethnicity/region, and (with exception for age at menarche) education level and adjusted for relevant covariates (described below) using linear regression models. The decade of the woman’s year of birth and race/ethnicity/region were included as covariates in all models. In addition, the level of education was included in the model for age at first birth; while the model for age at natural menopause included level of education, smoking status (never, past and current smoker), and BMI (underweight, normal, overweight and obese) at the baseline survey. Age at menarche and parity were further included in the models for age at menopause only for studies with data on both variables. The distribution of parity and the median number of children for parous women were also reported for each study. The proportions of women with no children (nulliparity) were also stratified by these key factors.

In the second stage, the crude mean estimates from each study were combined using random-effects meta-analysis (with study as the random effect) to obtain overall pooled estimates, with the forest plots presented in Fig. 1. The adjusted mean ages at menarche, first birth, and menopause and the proportions of nulliparity (unadjusted) were also combined from each study using random-effects meta-analyses by women’s year of birth, racial/ethnic/regional group, and education level (Figs 2–5). In other words, for each category of the covariates (year of birth, racial/ethnic/regional group and education level) the figures show the study-specific means of the outcome variables pooled from studies with available data. Between-study heterogeneity was assessed using chi-square (Cochrane Q) and I2 statistics (Higgins et al., 2003; Palmer and Sterne, 2016).

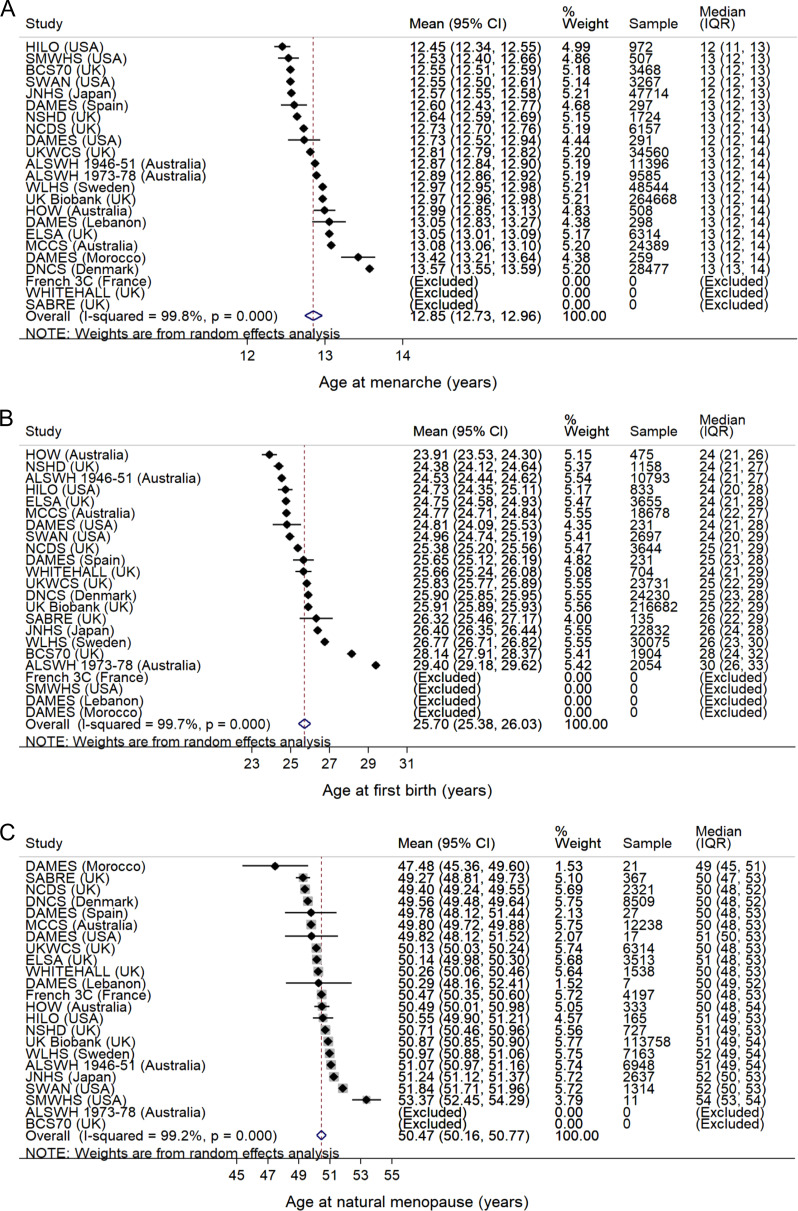

Figure 1.

Mean ages at (A) menarche (n = 493 395), (B) first birth (among parous women, n = 384 925) and (C) natural menopause (among postmenopausal women, n = 172 125) in the InterLACE Consortium. Mean ages were estimated in each study (accounting for design weights if available), and the estimates from each study were combined using random-effects meta-analysis. Median (interquartile range, IQR) ages were also presented for each study. Data on age at first birth were only included in the analysis from women aged ≥40 years at last follow-up and data on age at natural menopause only from women aged ≥55 years at last follow-up.

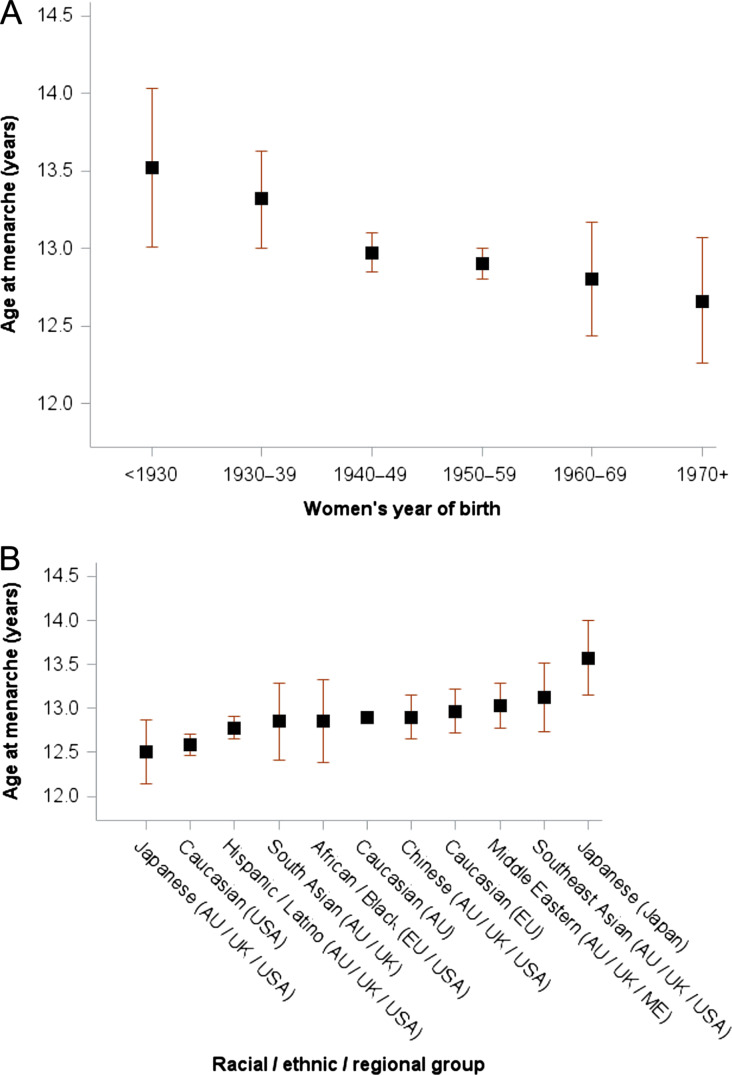

Figure 2.

Mean age at menarche (n = 493 395). Data are stratified by (A) year of birth (P for trend = 0.0014) and (B) racial/ethnic/regional group. Mean age at menarche was stratified by birth year and race/ethnicity/region in each study and mutually adjusted (i.e. birth year and race/ethnicity/region) using linear regression models (accounting for design weights if available), and the adjusted estimates from each study were combined using random-effects meta-analysis for each category of covariates.

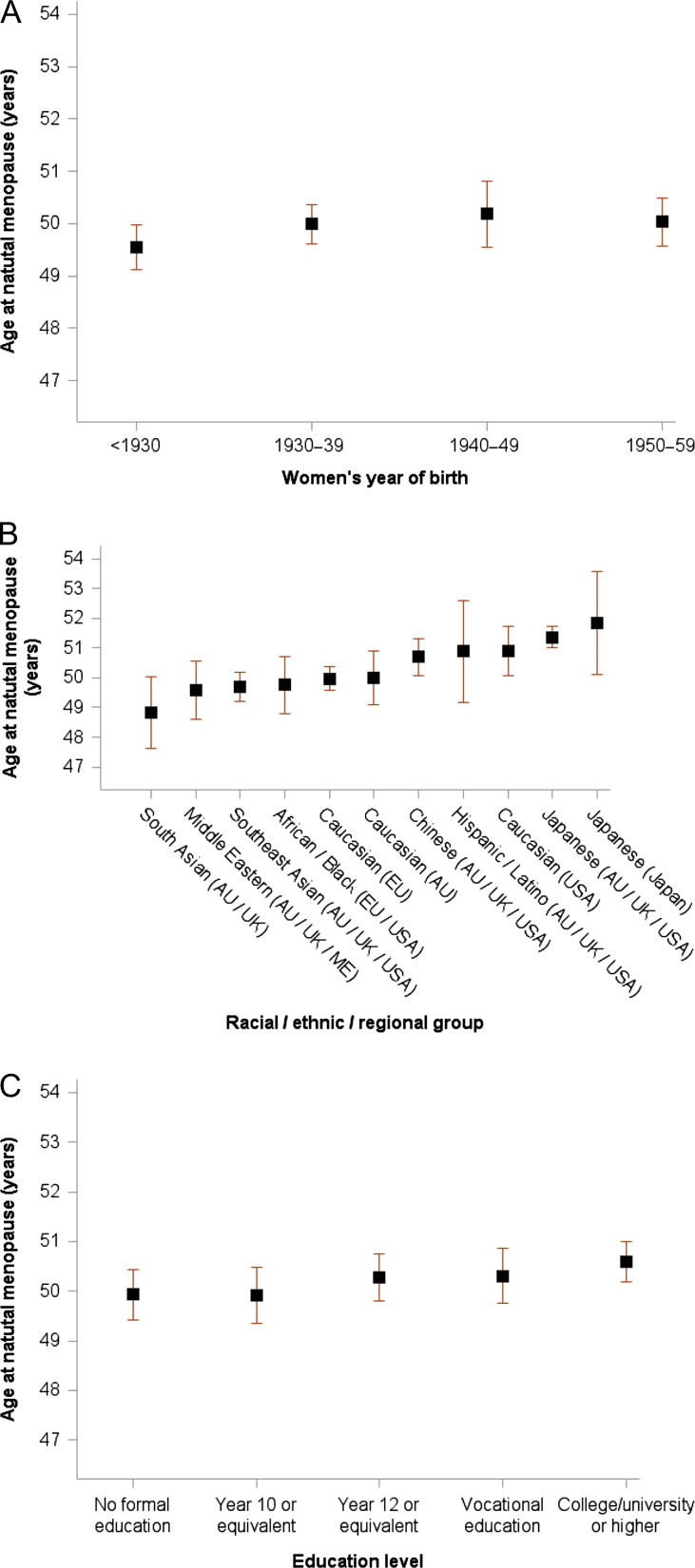

Figure 5.

Mean age at natural menopause among postmenopausal women aged ≥55 years at last follow-up (n = 172 125). Data are stratified by (A) year of birth (P for trend = 0.26), (B) racial/ethnic/regional group and (C) education level (P for trend = 0.012). Mean age at natural menopause was stratified by birth year, race/ethnicity/region and education level in each study and mutually adjusted (i.e. birth year, race/ethnicity/region and education level) and additionally adjusted for smoking status and BMI using linear regression models (accounting for design weights if available), and the adjusted estimates from each study were combined using random-effects meta-analysis for each category of covariate.

Eleven studies included women who were younger than 40 years at final follow-up, who could, therefore, still have experienced reproductive events, such as giving birth to their first child and particularly natural menopause, after this time point. To avoid this source of sample bias, data on parity and age at first birth were only included in the analysis from women aged ≥40 years at last follow-up and data on age at natural menopause only from women aged ≥55 years at last follow-up. A sensitivity analysis was performed using the first and the last reported age at menopause (where the reported age varied between different surveys). Survival analysis was also performed for each study with no restricted criteria on age at last follow-up and including pre- or perimenopausal women in the analysis (total sample = 373 154). Reported age at menopause was used as outcome, and women were censored at the age of medical interventions (e.g. hysterectomy or bilateral oophorectomy) that led to menopause, or age at loss to follow-up or the end of the study for women who were pre- or perimenopausal at the last follow-up. The study-specific mean estimates were then pooled using random-effects meta-analysis. Generalised linear models were performed using SAS version 9.4, and meta-analyses were performed using Stata version 14.0 (Palmer and Sterne, 2016)).

Results

From the 23 studies, 505 147 women provided information on either age at menarche or natural menopause or both and were included in the analyses. Women had a median baseline age of 52 years, ranging from 40 to 74 years across studies (Table I). Except for the two contemporary cohorts of women born after 1970 and the French Three-City study of older adults, all studies included women born between 1940 and 1960, and this birth interval included the majority of women in InterLACE (69%). Several studies included women born earlier or later, with 11% of women across all studies born before 1940 and 20% after 1960. The majority of women in InterLACE had a Caucasian background (87%) (Table II), with Japanese women identified as another major group (9.7%), followed by African American/Black (1.3%) and South Asian (0.9%). Across studies, almost one in four women (24.3%) had at least college or university degree, 23.0% had trade/certificate/diploma or vocational education, 12.3% had completed year 12, 34.6% had completed year 10, and 5.8% had no formal education (data not shown).

Table II.

Study-specific distribution of racial/ethnic/regional groups across 23 studies included in the InterLACE Consortium (N = 505 147).

| Racial/ethnic/regional groups* | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | N | Caucasian (AU) n (%) | Caucasian (EU) n (%) | Caucasian (USA) n (%) | African/ Black (EU/USA) n (%) | Japanese (AU/UK/USA) n (%) | Japanese (Japan) n (%) | Chinese (AU/UK/USA) n (%) | South Asian (AU/UK) n (%) | Southeast Asian (AU/UK/USA) n (%) | Middle Eastern (AU/UK/ME) n (%) | Hispanic/ Latino (AU/UK/USA) n (%) | Other n (%) |

| ALSWH 1946–51 | 12 223 | 9602 (78.6) | 2034(16.6) | 83 (0.7) | N/A | 8 (0.1) | N/A | 43 (0.4) | 58 (0.5) | 172 (1.4) | 22 (0.2) | 33 (0.3) | 168 (1.4) |

| ALSWH 1973–78 | 9585 | 8921 (93.1) | 235 (2.5) | 20 (0.2) | N/A | 1 (0.0) | N/A | 50 (0.5) | 9 (0.1) | 131 (1.4) | 19 (0.2) | 15 (0.2) | 184 (1.9) |

| HOW | 520 | 431 (82.9) | 66 (12.7) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 3 (0.6) | N/A | N/A | 20 (3.8) |

| MCCS | 24 423 | 17 333 (71.0) | 7090 (29.0) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| DNCS | 28 573 | N/A | 28 573 (100) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| WLHS | 48 691 | N/A | 48 691 (100) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| French 3 C | 4255 | N/A | 3912 (91.9) | 9 (0.2) | 319 (7.5) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 15 (0.4) |

| NSHD | 1898 | N/A | 1898 (100) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| NCDS | 6752 | N/A | 6652 (98.5) | N/A | 26 (0.4) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 25 (0.4) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 49 (0.7) |

| BCS70 | 3468 | N/A | 3394 (97.9) | N/A | 9 (0.3) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 39 (1.1) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 26 (0.7) |

| ELSA | 6364 | N/A | 6175 (97.0) | N/A | 44 (0.7) | N/A | N/A | 1 (0.0) | 14 (0.2) | N/A | 2 (0.0) | 1 (0.0) | 127 (2.0) |

| UKWCS | 34 771 | N/A | 34 327 (98.7) | N/A | 53 (0.2) | N/A | N/A | 22 (0.1) | 164 (0.5) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 205 (0.6) |

| WHITEHALL | 1779 | N/A | 1567 (88.1) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 212 (11.9) |

| SABRE | 485 | N/A | 261 (53.8) | N/A | 128 (26.4) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 96 (19.8) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| HILO | 975 | N/A | N/A | 235 (24.1) | 1 (0.1) | 290 (29.7) | N/A | 9 (0.9) | N/A | 30 (3.1) | N/A | 9 (0.9) | 401 (41.1) |

| SWAN | 3284 | N/A | N/A | 1542 (47.0) | 928 (28.3) | 280 (8.5) | N/A | 250 (7.6) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 284 (8.6) | N/A |

| SMWHS | 507 | N/A | N/A | 391 (77.1) | 58 (11.4) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 6 (1.2) | 52 (10.3) |

| DAMES–USA | 293 | N/A | N/A | 276 (94.2) | 6 (2.0) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 3 (1.0) | 8 (2.7) |

| DAMES–Lebanon | 298 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 298 (100) | N/A | N/A |

| DAMES–Spain | 298 | N/A | 287 (96.3) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 11 (3.7) | N/A |

| DAMES–Morocco | 273 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 273 (100) | N/A | N/A |

| JNHS | 47 745 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 47 745 (100) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| UK Biobank | 267 687 | 470 (0.2) | 252 672 (94.4) | 974 (0.4) | 5130 (1.9) | 211 (0.1) | N/A | 964 (0.4) | 3980 (1.5) | 469 (0.2) | 351 (0.1) | 339 (0.1) | 2127 (0.8) |

| Overall | 505 147 | 36 757 (7.3) | 397 834 (78.8) | 3530 (0.7) | 6702 (1.3) | 790 (0.2) | 47 745 (9.5) | 1339 (0.3) | 4385 (0.9) | 805 (0.2) | 965 (0.2) | 701 (0.1) | 3594 (0.7) |

Abbreviations: AU, Australia; EU, Europe; ME, Middle East; N/A, not applicable.

*Race/ethnicity was derived from self-identified racial/ethnic background reported in 13 studies. For the remaining studies, race/ethnicity was defined based on the reported country of birth, the language spoken at home, or the country where the study was conducted (residency).

Age at menarche

Mean age at menarche for 493 395 women across 20 studies was 12.9 years (95% CI 12.7–13.0) with high heterogeneity evident between studies (I2 = 99.8%) (Fig. 1 A).

By year of birth

When mean age at menarche was stratified by year of birth (Fig. 2 A), the pooled analyses showed a significant linear trend for earlier age at menarche with the later birth year that remained after adjusting for race/ethnicity/region (P for trend = 0.0014). These adjusted results show that women born before 1930 had a mean age at menarche of 13.5 years (13.0–14.0), whereas women born from 1970 onwards (1970–84) experienced menarche an almost one year earlier at mean age 12.6 years (12.3–13.1). The proportion of women with early age at menarche (≤11 years, n = 91 528, 18.6%) also increased from 12.5% for women born before 1930 to 19.8% for those born from 1970 onwards.

By race/ethnicity/region

Age at menarche varied considerably across racial/ethnic/regional groups even after adjusting for birth year (Fig. 2B). For instance, Japanese women in the AU/UK/USA had the earliest mean age at menarche of 12.5 years (12.1–12.9), which was one year earlier than women in Japan who recorded the latest mean age at menarche (13.6 years, 13.2–14.0), but was similar to Caucasian women in the USA (12.6 years, 12.5–12.7).

Parity

Across the 21 studies with information on parity (n = 453 515), 16% of women reported having no children (nulliparity). Among parous women (n = 379 344), 15% had one child, 51% had two, and 34% had three or more (Table III), and the median number of children was 2 (Interquartile range 2–3).

Table III.

Study-specific distribution of number of children across 23 studies included in the InterLACE Consortium (N = 453 515)*.

| Number of children among parous women (n = 379 344) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | N | Nulliparity (%) | One child (%) | Two children (%) | Three or more children (%) | Median (IQR) |

| ALSWH 1946–51 | 11 781 | 7.2 | 9.2 | 42.8 | 48.0 | 2.0 (2.0, 3.0) |

| ALSWH 1973–78 | 2528 | 18.8 | 14.9 | 50.3 | 34.9 | 2.0 (2.0, 3.0) |

| HOW | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| MCCS | 24 396 | 14.0 | 9.7 | 36.6 | 53.8 | 3.0 (2.0, 3.0) |

| DNCS | 28 501 | 14.9 | 14.4 | 49.1 | 36.5 | 2.0 (2.0, 3.0) |

| WLHS | 41 365 | 9.7 | 14.8 | 49.6 | 35.6 | 2.0 (2.0, 3.0) |

| French 3 C | 3845 | 15.9 | 23.1 | 32.8 | 44.1 | 2.0 (2.0, 3.0) |

| NSHD | 1175 | 11.9 | 14.0 | 51.3 | 34.7 | 2.0 (2.0, 3.0) |

| NCDS | 3824 | 13.4 | 17.0 | 53.1 | 29.9 | 2.0 (2.0, 3.0) |

| BCS70 | 2598 | 21.3 | 21.8 | 54.5 | 23.7 | 2.0 (2.0, 2.0) |

| ELSA | 6111 | 12.7 | 18.5 | 45.7 | 35.8 | 2.0 (2.0, 3.0) |

| UKWCS | 27 385 | 13.2 | 15.7 | 50.1 | 34.2 | 2.0 (2.0, 3.0) |

| WHITEHALL | 1498 | 46.0 | 28.2 | 44.0 | 27.8 | 2.0 (1.0, 3.0) |

| SABRE | 159 | 10.7 | 18.3 | 28.2 | 53.5 | 3.0 (2.0, 4.0) |

| HILO | 955 | 12.3 | 18.1 | 43.2 | 38.7 | 2.0 (2.0, 3.0) |

| SWAN | 3244 | 16.7 | 19.9 | 40.5 | 39.7 | 2.0 (2.0, 3.0) |

| SMWHS | 390 | 25.9 | 23.5 | 42.6 | 33.9 | 2.0 (2.0, 3.0) |

| DAMES –USA | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| DAMES –Lebanon | 296 | 1.4 | 3.4 | 9.9 | 86.6 | 4.0 (3.0, 5.0) |

| DAMES –Spain | 298 | 22.5 | 17.8 | 54.1 | 28.1 | 2.0 (2.0, 3.0) |

| DAMES –Morocco | 273 | 7.0 | 5.5 | 9.8 | 84.7 | 4.0 (3.0, 6.0) |

| JNHS | 26 526 | 15.2 | 12.6 | 52.6 | 34.8 | 2.0 (2.0, 3.0) |

| UK Biobank | 266 367 | 18.5 | 16.4 | 53.9 | 29.7 | 2.0 (2.0, 3.0) |

| Overall | 453 515 | 16.4 | 15.4 | 51.0 | 33.6 | 2.0 (2.0, 3.0) |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; N/A, not applicable.

*Data on parity were only included in the analysis from women aged ≥40 years at last follow-up.

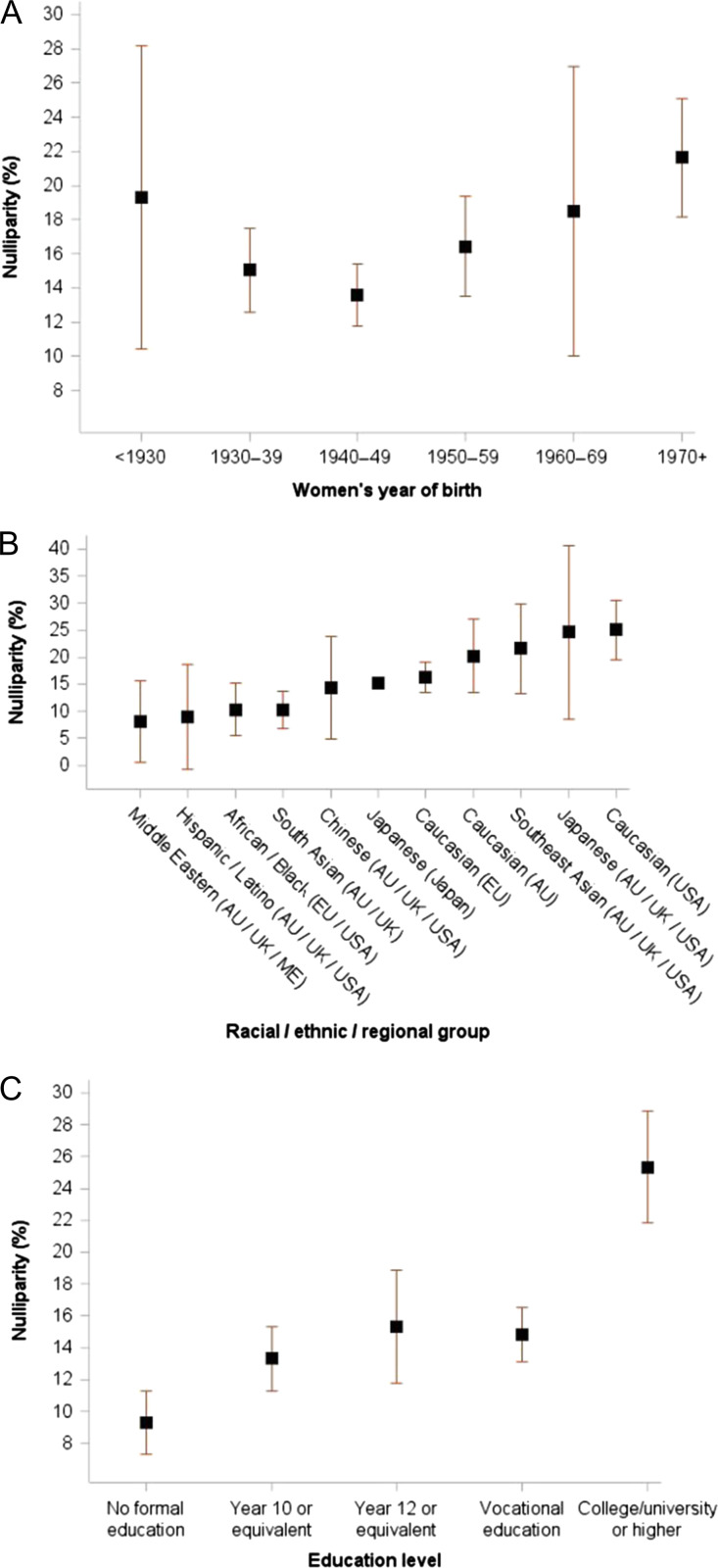

By year of birth

The proportion of nulliparous women stratified by year of birth suggests a shallow U-shape over time (Fig. 3 A). For women born before 1930 the proportion of nulliparity was 19.3%, which decreased to 13.6% for women born in 1940–49, and then increased with birth year to 21.6% for women born from 1970 onwards.

Figure 3.

Proportion of women with no children (nulliparity) among women aged ≥40 years at last follow-up (n = 453 515). Data are stratified by (A) year of birth (P for trend = 0.37), (B) racial/ethnic/regional group and (C) education level (P for trend = 0.0395). Proportion of nulliparity was stratified by birth year, race/ethnicity/region and education level in each study (accounting for design weights if available), and the unadjusted estimates from each study were combined using random-effects meta-analysis for each category of variables.

By race/ethnicity/region

Substantial variation in nulliparity was evident across racial/ethnic/regional groups (Fig. 3B). The lowest prevalence levels for nulliparity (8.1–10.3%) were seen for Middle Eastern, Hispanic/Latino, African American/Black and South Asian women.

By education level

Higher education levels were associated with nulliparity (P for trend = 0.04) (Fig. 3 C). One in four (25.3%) women with college/university were nulliparous, compared with 9.3% for those with no formal education.

Age at first birth

Mean age at first birth for 364 742 parous women across 19 studies was 25.7 years (25.4–26.0) with significant between-study heterogeneity (I2 = 99.7%) (Fig. 1B).

By year of birth

Age at first birth was statistically different across the mothers’ birth year groups even after adjusting for race/ethnicity/region and education level (Fig. 4 A). Similar to the U-shape evident for nulliparity, the adjusted results show mean age at first birth was 27.2 years (25.4–28.9) for women born before 1930 and decreased to 24.8 years (23.7–25.9) for women born in 1940–49. Across subsequent birth decades, the adjusted mean age at first birth was progressively delayed to reach 27.3 years (26.6–28.0) for women born from 1970 onwards.

Figure 4.

Mean age at first birth among parous women aged ≥40 years at last follow-up (n = 384 925). Data are stratified by (A) year of birth (P for trend = 0.87), (B) racial/ethnic/regional group and (C) education level (P for trend = 0.0031). Mean age at first birth was stratified by birth year, race/ethnicity/region and education level in each study and mutually adjusted (i.e. birth year, race/ethnicity/region and education level) using linear regression models (accounting for design weights if available), and the adjusted estimates from each study were combined using random-effects meta-analysis for each category of covariates.

By race/ethnicity/region

Substantial variability was evident for age at first birth across different racial/ethnic/regional groups (Fig. 4B) even after adjusting for year of birth and education level. First birth was reported at younger ages for Hispanic/Latino and African American/Black women (between 23.7 and 24.1 years), whereas Chinese women in AU/UK/USA reported an adjusted mean age at first birth of 27.6 years.

By education level

Higher education level was associated with later age at first birth, and this remained after adjusting for year of birth and race/ethnicity/region (Fig. 4 C), with each step up in education category corresponding to a delay of about one year (P for trend = 0.0028). For women with college/university degree, the adjusted mean age at first birth was 28.1 years (27.7–28.6), compared with 23.5 years (22.6–24.4) for women with no formal education.

Age at natural menopause

Mean age at natural menopause for 172 125 women reporting natural menopause across 21 studies was 50.5 years (50.2–50.8) with significant between-study heterogeneity (I2 = 99.2%) (Fig. 1 C). The pooled mean age at menopause using survival analysis was 50.9 years (50.6–51.2) (n = 373 154; data now shown). The subsequent results decribed below for different factors were after mutual adjustments and also adjusted for smoking status and BMI.

By year of birth

No clear trend was observed in variability in age at natural menopause according to birth year, and this remained the case after adjusting for covariates (P for trend = 0.22) (Fig. 5 A).

By race/ethnicity/region

Substantial variation was present in age at natural menopause across racial/ethnic/regional groups that remained after adjustment (Fig. 5B). Youngest mean ages at natural menopause occurred for South Asian (48.8 years), Middle Eastern, Southeast Asian and African American/Black women (between 49.6 and 49.8 years) which persisted after further adjusting for menarche and parity, whereas highest mean ages were observed for Japanese (USA/UK) (51.4 years) and Japanese (Japan) (51.9 years).

By education level

Age at natural menopause tended to occur later for women with higher education levels (P for trend = 0.012), even after adjusting for year of birth, race/ethnicity/region, smoking and body weight (Fig. 5 C). Women who received college/university education reporting an adjusted mean age at menopause of 50.6 years (50.2–51.0) compared with those who had no formal education reporting menopause at 49.9 years (49.4–50.4). The results remained after further adjustment for menarche and parity.

Discussion

In this global consortium study, individual-level data from over 500 000 women were used to analyse the variability in the timing of menarche, first birth and menopause by birth year, racial/ethnic/regional group and education level. On average women reached menarche at age 12.9 years, had their first birth at 25.7 years, and experienced natural menopause at 50.5 years. This study provides the most robust evidence currently available on variations in these key reproductive indices across sociodemographic groups, including adjustment for relevant covariates.

The variations by decade of birth year and education level point to cohort effects and socio-environmental influence (especially socioeconomic changes) on markers of reproductive health. The mean age at menarche declined progressively with birth year, by almost one year from 13.5 years for women born before the 1930s to 12.6 years for the youngest women in the study, born from 1970 to 1984. In contrast, however, a shallow U-shape was evident for both age at first birth and nulliparity which reached a minimum for women born in 1940–49, and then increased from age 24.8 years to over 27 years and from 14% to 22%, respectively, for women born from 1970 to 1984. This pattern reflects major economic and sociologic events. A higher proportion of nulliparity and higher age at first birth was evident during the great depression. In the decades after World War II, the rise in the level of educational attainment among women partly explains the trend to later childbearing and the secular decline in birth rates, with an increase in the proportion of nulliparous women for the most educated (college/university degree) compared with the least educated (no formal education) and a decline in the percentage with three or more children (data not shown). Women with higher education levels also tended to experience natural menopause at a later age, after accounting for established factors such as parity and smoking status.

The timing of reproductive events varied considerably by racial/ethnic/regional groups. These differences underscore the influence of cultural and early environmental exposures as well as biological/genetic factors on ages at menarche and menopause. For instance, Japanese women in AU/UK/USA had earlier ages at menarche (one year earlier) and menopause (half a year earlier) than their counterparts in Japan. Diet and lifestyle may partly explain the variations, as Japanese women living in the AU/UK/USA were more likely to be overweight (19.4% vs 11.1%) and obese (8.3% vs 1.8%) compared with those living in Japan. It should be noted that Japanese from Australia contributed only a small proportion of the data (n = 9) compared with UK and USA. Similarly, after adjusting for birth year and education, Caucasian women in the USA having higher prevalence of nulliparity, earlier age at menarche, and later age at menopause than Caucasian women in Europe or Australia also highlights the potential role of cultural and other environmental influences. In addition, the impact of migration on physical and mental health may play a role in relation to reproductive events, as the majority of non-Caucasian racial/ethnic groups in this study were the first or second-generation migrants living in Europe, Australia and USA.

The findings on the timing of the reproductive events are in broad agreement, within the margins of error, with estimates from a recent individual-participant meta-analysis of 117 epidemiological studies from 35 countries on breast cancer risk (Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer, 2012). That study found that cancer-free controls (over 300 000 women) had a mean age at menarche of 13.1 years (SD 1.7) and mean age at natural menopause of 49.3 years (SD 4.6). The evidence of decreased age at menarche over time identified from InterLACE is also consistent with other studies (Euling et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2009; Forman et al., 2013; Yang et al., 2017). The findings here also indicate that the variability in the timing of reproductive events is influenced by a range of social and environmental factors, such as birth year and education levels.

A number of limitations need to be acknowledged. Some differences in the study design, data collection methods, and sample selection may explain the observed variations across studies. For instance, the Whitehall II study from the UK comprised only women who were working for the civil service, with almost half reporting that they had no children. Similarly, the Japan Nurses Study was based on a sample from a single professional group. Furthermore, although prospective by design, most studies collected the information on menarche, age at first birth retrospectively (and in some cases age at menopause). Some recall and rounding errors in reporting these timings may have influenced our estimates. The bias is likely to be minimal since analysis using the first or the last reported age at menopause (where available) did not make any substantive difference to our results. Age at natural menopause obtained from repeated data in longitudinal studies was slightly later compared with studies in which it was reported retrospectively. However, it has been reported that women recall reproductive events, including age at first menses, with a high degree of accuracy. One validation study showed that nearly 80% of the women (mean age 42 years) precisely recalled their age at menarche to within one year of original menarche (55% within half a year of original menarche) (Must et al., 2002). In general, accuracy of recall is decreased with older age and lower education level. Another limitation is that the information on environmental chemicals (e.g. endocrine-disrupting chemicals) (Buttke et al., 2012; Grindler et al., 2015) and socioeconomic conditions during early life and adolescence, such as childhood growth and childhood adversities (e.g. abuse, stress, parental divorce, poverty and obesity) (Mishra et al., 2009; Boynton-Jarrett et al., 2013; Li et al., 2017), were not accounted for in this study, which may have significant impact on adult health behaviours as well as on the timing of menarche and menopause.

One strength of InterLACE is the access granted to individual-level data from international studies, which facilitates a detailed investigation of heterogeneity in reproductive events across and within studies without being subject to the potential for ecological fallacy. The use of individual-level data has enabled harmonisation of variables using common definitions, coding, and adjustment in the analysis. The scale of this study, which covers populations from Australia, Europe, North Africa, Middle East, USA and Japan, provides greater statistical power and diversity in the study sample than any individual study within InterLACE. This results in both more robust overall estimates and more detailed estimates for subpopulations, such as birth cohorts and racial/ethnic groups. It has women from a range of occupational backgrounds, from professional employment to unpaid work. In light of all these aspects, the results are likely to be generalisable to most mid-age women in high and some middle-income countries.

It should be noted that a single stage model could not be fitted to InterLACE data, as the data were highly unbalanced with respect to several of the key covariates. Instead, we used a two-stage method of analysis whereby the adjustment for confounders was made using individual-level data within each study at the first stage, and then the study-specific outcome means were pooled at the second stage, so that meta-analytic results were obtained for the main outcomes and the major factors affecting heterogeneity. Given the large number of participants in each study and the use of individual-level data for estimating the effect of covariates, it is reasonable to expect that if a one-stage analysis with similar assumptions had been possible, the results would have been very similar (Burke et al., 2017). This approach extends previous methods, where the similarity of results for one-stage and two-stage methods has been demonstrated for case–control studies (Stukel et al., 2001) and clinical trials (Berlin et al., 2002; Tierney et al., 2015).

This study provided findings for the broad generation of women who have lived through a unique set of circumstances and now increasingly face the chronic diseases of older age. Although some women would have endured hardship in their early life, such as wartime food rationing, most participants experienced the relative prosperity of the post-war years. This was the first generation to have access to advanced birth control measures, including oral contraceptives, with concomitant social changes signified by their increasing participation in the workforce, higher educational attainment and delayed childbirth, as is exemplified by women in the study born since the 1970s. They thus provide an indication of what might be expected from the cohort of women now experiencing similar socioeconomic changes in developing countries, and also set a baseline of evidence about the timing of events along the reproductive axis to allow for comparison with the current generations of premenopausal women.

By identifying both variations in the timing of reproductive characteristics within and between populations and in relation to environmental factors, this global consortium study strengthens the evidence base on key reproductive indices that have implications for the provision of future health services. The results also advance understanding of the potential impact of social changes now occurring in low- and middle-income countries on women’s reproductive characteristics.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

All study teams would like to thank the participants for volunteering their time to be involved in the respective studies. The findings and views in this paper are not those from the original studies or their respective funding agencies.

Authors’ roles

The InterLACE Study Team provided study data and all contributed to comments and revisions of this manuscript.

Funding

InterLACE project is funded by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council project grant (APP1027196). G.D.M. is supported by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council Principal Research Fellowship (APP1121844). For each participating study, the list of funding sources is given in the online Supplementary Information.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

References

- Atsma F, Bartelink M-LE, Grobbee DE, van der Schouw YT. Postmenopausal status and early menopause as independent risk factors for cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis. Menopause 2006;13:265–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlin JA, Santanna J, Schmid CH, Szczech LA, Feldman HI, Anti-Lymphocyte Antibody Induction Therapy Study Group. Individual patient- versus group-level data meta-regressions for the investigation of treatment effect modifiers: ecological bias rears its ugly head. Stat Med 2002;21:371–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boynton-Jarrett R, Wright RJ, Putnam FW, Lividoti Hibert E, Michels KB, Forman MR, Rich-Edwards J. Childhood abuse and age at menarche. J Adolesc Health 2013;52:241–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand JS, van der Schouw YT, Onland-Moret NC, Sharp SJ, Ong KK, Khaw KT, Ardanaz E, Amiano P, Boeing H, Chirlaque MD et al. Age at menopause, reproductive life span, and type 2 diabetes risk: results from the EPIC-InterAct study. Diabetes Care 2013;36:1012–1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke DL, Ensor J, Riley RD. Meta-analysis using individual participant data: one-stage and two-stage approaches, and why they may differ. Stat Med 2017;36:855–875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buttke DE, Sircar K, Martin C. Exposures to endocrine-disrupting chemicals and age of menarche in adolescent girls in NHANES (2003–2008). Environ Health Perspect 2012;120:1613–1618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charalampopoulos D, McLoughlin A, Elks CE, Ong KK. Age at menarche and risks of all-cause and cardiovascular death: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol 2014;180:29–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer Menarche, menopause, and breast cancer risk: individual participant meta-analysis, including 118,964 women with breast cancer from 117 epidemiological studies. Lancet Oncol 2012;13:1141–1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- dos Santos Silva I, Beral V. Socioeconomic differences in reproductive behaviour. IARC Sci Publ 1997;138:285–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Euling SY, Herman-Giddens ME, Lee PA, Selevan SG, Juul A, Sørensen TI, Dunkel L, Himes JH, Teilmann G, Swan SH. Examination of US puberty-timing data from 1940 to 1994 for secular trends: panel findings. Pediatrics 2008;121:S172–S191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forman MR, Mangini LD, Thelus-Jean R, Hayward MD. Life-course origins of the ages at menarche and menopause. Adolesc Health Med Ther 2013;4:1–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grindler NM, Allsworth JE, Macones GA, Kannan K, Roehl KA, Cooper AR. Persistent organic pollutants and early menopause in U.S. women. PLoS One 2015;10:e0116057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003;327:557–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosokawa M, Imazeki S, Mizunuma H, Kubota T, Hayashi K. Secular trends in age at menarche and time to establish regular menstrual cycling in Japanese women born between 1930 and 1985. BMC Womens Health 2012;12:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janghorbani M, Mansourian M, Hosseini E. Systematic review and meta-analysis of age at menarche and risk of type 2 diabetes. Acta Diabetol 2014;51:519–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juul A, Teilmann G, Scheike T, Hertel NT, Holm K, Laursen EM, Main KM, Skakkebaek NE. Pubertal development in Danish children: comparison of recent European and US data. Int J Androl 2006;29:247–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Liu Q, Deng X, Chen Y, Liu S, Story M. Association between obesity and puberty timing: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2017;14:1266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B, Balkwill A, Cooper C, Roddam A, Brown A, Beral V. Reproductive history, hormonal factors and the incidence of hip and knee replacement for osteoarthritis in middle-aged women. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:1165–1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews TJ, Hamilton BE Mean age of mothers is on the rise: United States, 2000–2014; 2016; Available from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db232.htm [cited 2017 Dec 20]. [PubMed]

- Mishra GD, Anderson D, Schoenaker DA, Adami HO, Avis NE, Brown D, Bruinsma F, Brunner E, Cade JE, Crawford SL et al. InterLACE: a new international collaboration for a life course approach to women’s reproductive health and chronic disease events. Maturitas 2013;74::235–:240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra GD, Chung HF, Pandeya N, Dobson AJ, Jones L, Avis NE, Crawford SL, Gold EB, Brown D, Sievert LL et al. The InterLACE study: design, data harmonization and characteristics across 20 studies on women’s health. Maturitas 2016;92:176–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra GD, Cooper R, Tom SE, Kuh D. Early life circumstances and their impact on menarche and menopause. Womens Health (Lond) 2009;5:175–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morabia A, Costanza MC. International variability in ages at menarche, first livebirth, and menopause. Am J Epidemiol 1998;148:1195–1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris DH, Jones ME, Schoemaker MJ, Ashworth A, Swerdlow AJ. Secular trends in age at menarche in women in the UK born 1908–93: results from the Breakthrough Generations Study. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2011;25:394–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muka T, Asllanaj E, Avazverdi N, Jaspers L, Stringa N, Milic J, Ligthart S, Ikram MA, Laven JSE, Kavousi M et al. Age at natural menopause and risk of type 2 diabetes: a prospective cohort study. Diabetologia 2017;60:1951–1960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Must A, Phillips SM, Naumova EN, Blum M, Harris S, Dawson-Hughes B, Rand WM. Recall of early menstrual history and menarcheal body size: after 30 years, how well do women remember? Am J Epidemiol 2002;155:672–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer TM, Sterne JAC. Meta-analysis in Stata: An Updated Collection from the Stata Journal, 2nd edn TX: Stata Press, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Parkin D. Cancers attributable to reproductive factors in the UK in 2010. Br J Cancer 2011;105:S73–S76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin C, Maisonet M, Kieszak S, Monteilh C, Holmes A, Flanders D, Heron J, Golding J, McGeehin M, Marcus M. Timing of maturation and predictors of menarche in girls enrolled in a contemporary British cohort. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2009;23:492–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenaker DA, Jackson CA, Rowlands JV, Mishra GD. Socioeconomic position, lifestyle factors and age at natural menopause: a systematic review and meta-analyses of studies across six continents. Int J Epidemiol 2014;43:1542–1562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stukel TA, Demidenko E, Dykes J, Karagas MR. Two-stage methods for the analysis of pooled data. Stat Med 2001;20:2115–2130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas F, Renaud F, Benefice E, de Meeüs T, Guegan JF. International variability of ages at menarche and menopause: patterns and main determinants. Hum Biol 2001;73:271–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tierney JF, Vale C, Riley R, Smith CT, Stewart L, Clarke M, Rovers M. Individual Participant Data (IPD) Meta-analyses of Randomised Controlled Trials: guidance on their use. PLoS Med 2015;12:e1001855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Li L, Millwood IY, Peters SAE, Chen Y, Guo Y, Bian Z, Chen X, Chen L, Feng S et al. Age at menarche and risk of major cardiovascular diseases: evidence of birth cohort effects from a prospective study of 300,000 Chinese women. Int J Cardiol 2017;227:497–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.