Abstract

Background

Hyperactivation of the RAS-RAF-MEK-ERK signaling pathway is exploited by glioma cells to promote their growth and evade apoptosis. MEK activation in tumor cells can increase replication of ICP34.5-deleted herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1), but paradoxically its activation in tumor-associated macrophages promotes a pro-inflammatory signaling that can inhibit virus replication and propagation. Here we investigated the effect of blocking MEK signaling in conjunction with oncolytic HSV-1 (oHSV) for brain tumors.

Methods

Infected glioma cells co-cultured with microglia or macrophages treated with or without trametinib were used to test trametinib effect on macrophages/microglia. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, western blotting, and flow cytometry were utilized to evaluate the effect of the combination therapy. Pharmacokinetic (PK) analysis of mouse plasma and brain tissue was used to evaluate trametinib delivery to the CNS. Intracranial human and mouse glioma-bearing immune deficient and immune competent mice were used to evaluate the antitumor efficacy.

Result

Oncolytic HSV treatment rescued trametinib-mediated feedback reactivation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway in glioma. In vivo, PK analysis revealed enhanced blood–brain barrier penetration of trametinib after oHSV treatment. Treatment by trametinib, a MEK kinase inhibitor, led to a significant reduction in microglia- and macrophage-derived tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) secretion in response to oHSV treatment and increased survival of glioma-bearing mice. Despite the reduced TNFα production observed in vivo, the combination treatment activated CD8+ T-cell mediated immunity and increased survival in a glioma-bearing immune-competent mouse model.

Conclusion

This study provides a rationale for combining oHSV with trametinib for the treatment of brain tumors.

Keywords: glioblastoma (GBM), oncolytic herpes simplex virus-1 (oHSV), RAS-RAF-MEK-ERK signaling, trametinib, tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα)

Key Points.

1. HSV therapy significantly increases blood–brain barrier penetration of trametinib.

2. HSV treatment could revert trametinib-induced feedback reactivation of MEK signaling.

3. Trametinib treatment reduces oHSV therapy–induced inflammatory TNFα secretion and enhances T-cell dependent antitumor immunity.

Importance of the Study.

Glioblastoma (GBM) has limited therapeutic options, primarily due to poor drug penetration into the CNS. Oncolytic viruses are now being evaluated in clinical trials for GBM. Although activation of the RAS-RAF-MEK-ERK signaling pathway is common in GBM, trametinib, the FDA-approved MEK kinase inhibitor, has limited utility for brain tumors due to its poor CNS penetrance. Here we show that oHSV treatment increases trametinib penetration into the brain of glioma-bearing mice and enhances animal survival. Trametinib treatment in conjunction with oHSV therapy also activated T-cell dependent antitumor immunity. Our study highlights the effectiveness utilizing MEK kinase inhibitors in conjunction with oHSV-based therapy for the treatment of GBM.

Compared with other cancers which have considerably benefited from therapeutic advancements, glioblastomas (GBMs) remain resistant to traditional therapies and patient outcome remains dismal.1 Oncolytic HSV (oHSV) therapy has emerged as an attractive treatment option for therapy-resistant cancers, and several oncolytic vectors are currently being investigated for safety and efficacy in patients diagnosed with GBM.2,3 In the wake of these advancements, investigating the impact of virotherapy in the setting of chemotherapy is important to guide researchers and clinicians on how to maximize therapeutic benefit while minimizing toxicity.4 Trametinib is an FDA-approved MEK1/2 kinase inhibitor for the treatment of metastatic melanoma patients harboring a BRAFV600E/K mutation, either as a monotherapy or in combination with dabrafenib.5 While RAF mutations are a rare event in GBM, activation of the RAS-RAF-MEK-ERK signaling cascade via loss of or mutations in neurofibromin 1 (NF1) or upstream receptor tyrosine kinases are a frequent event in these tumors,6 thus targeting this pathway could be beneficial. However, poor CNS penetration of trametinib has limited its clinical use for intracranial malignancies.7

In addition to tumor cells, macrophages have also been shown to rely on an activated MEK/ERK signaling pathway during infection and specifically in the context of an lipopolysaccharide-induced pro-inflammatory response. Interestingly, oHSV therapy for glioma has been shown to induce macrophage infiltration to the tumor bed, resulting in their activation and release of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα). In this context, macrophages have shown the potential to promote tumor growth, invasion, and angiogenesis, as well as result in virus clearance.8 The impact of combining trametinib with oHSV as a treatment for intracranial GBM has not been explored to our knowledge.

In this study, we found that oHSV therapy increased blood–brain barrier (BBB) penetration of trametinib. Combination of trametinib and oHSV improved antitumor efficacy in 3 different animal models. Interestingly, despite a reduction in pro-inflammatory TNFα secretion, the combination therapy improved antitumor immunity in a syngeneic mouse model. To our knowledge, this is the first report investigating the impact of oHSV therapy on CNS drug penetration and implies the utilization of oncolytic viruses to enhance the delivery of BBB impermeable agents.

Materials and Methods

Cells and Viruses

Human glioma cell lines (U251T3 and U87ΔEGFR), Vero, murine BV2 microglia cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Gibco BRL) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. Murine RAW264.7 macrophages were maintained in Roswell Park Memorial Institute medium supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum. Patient-derived primary GBM cells (GBM30, GBM8, GBM12, GBM28, and GBM43) were maintained as tumor spheres in DMEM/F-12 supplemented with 2% B27 without vitamin A, human epidermal growth factor (EGF) (20 ng/mL), and basic fibroblast growth factor (20 ng/mL). The details about source and short tandem repeat profiling of cells is described in the Supplementary Material. For oHSV, we used rHSVQ and rHSVQ-IE4/5-luciferase (rHSVQ-Luc), which are both disrupted in the UL39 locus and deleted for both copies of the ICP34.5 gene; rHSVQ-Luc also contains the luciferase transgene under the HSV-1 IE4/5 promoter.9 Viral stocks were generated and titered on Vero cells via standard plaque forming unit assays as previously described.9 Primary murine bone marrow–derived macrophages (BMDMs) were isolated as previously described8 and details of BMDM generation are described in the Supplementary Material.

Quantitative Virus Spread by Cytation 5 Live Imaging

Virus-encoded green fluorescent protein (GFP) expression was monitored every 2 hours for 24 hours using the Cytation 5 live plate reader/imager (BioTek Instruments) (details are described in the Supplementary Material).

Viral Replication Assay

The number of infectious particles present was determined by performing a standard plaque formation assay on Vero cells as described8 (details are in the Supplementary Material).

Western Blot and ELISA Assays

Cell lysates were fractionated by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. Blocked membranes were then incubated with antibodies against phosphorylated MEK, total MEK, phosphorylated extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), total ERK, caspase-8, cleaved poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) (Cell Signaling Technology), glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Abcam), horseradish peroxidase (HRP)–conjugated secondary anti-mouse antibody (GE Healthcare), and HRP-conjugated secondary goat anti-rabbit antibody (Dako). All antibodies were diluted 1:1000 and the immunoreactive bands were visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence (GE Healthcare). Co-culture assay and quantification of murine TNFα by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was performed as previously described8 and murine TNFα was quantified in cell supernatants using the murine TNFα DuoSet ELISA kit (R&D Systems) per manufacturer’s recommendations.

Animal Surgery

All animal experiments were housed and performed in accordance with and approval of the Subcommittee on Research Animal Care of the Ohio State University and the Animal Welfare Committee at University of Texas Health Science Center. Intracranial glioma cells were implanted as previously described8 (details are in the Supplementary Material). In vivo virus propagation was measured by the IVIS Lumina Series III Pre-clinical In Vivo Imaging System (Perkin Elmer) as previously described8 (details are in the Supplementary Material).

Pharmacokinetic Analysis

Pharmacokinetic (PK) analyses of mouse plasma and brain tissue in glioma-bearing mice were conducted using a liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) system (Thermo Fisher Scientific). PK analysis of the whole blood data was performed using Phoenix 7.0 (Certara) modeling software. Detailed methods for LC-MS/MS are provided in the Supplementary Material.

Statistics

To compare 2 independent treatments for continuous endpoints such as viral titers and cell viability assay, a Student’s t-test was used. When multiple pairwise comparisons were made, one-way ANOVA was used. To evaluate the synergistic interaction between trametinib and oHSV, an interaction contrast or two-way ANOVA model was applied. Synergistic effect indicates that the combined treatment produced an effect (vs control) greater than the additive effect of 2 single treatments (vs control, respectively). A log-rank test was used to compare survival curves for survival data and a Cox regression model was used to evaluate the synergistic interaction between trametinib and oHSV on survival data. P-values were adjusted for multiple comparisons by Holms’s procedure. A P-value of 0.05 or less was considered significant.

Results

Trametinib Treated Macrophages and Microglial Cells Have a Reduced Pro-Inflammatory Antiviral Response

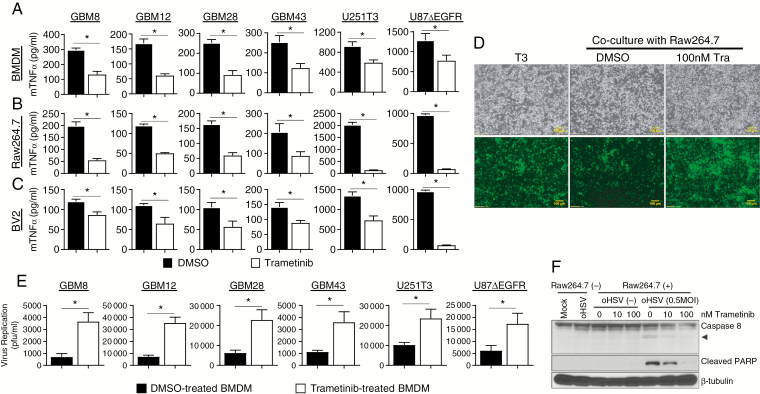

We have previously shown that macrophages and microglia (collectively referred to as effector cells here) secrete TNFα in response to infected glioma cells.8 To evaluate if trametinib treatment modulated the TNFα response in the context of oHSV therapy, patient derived primary GBM cells and glioma cell lines infected with or without oHSV for 1 hour were overlaid with macrophages or microglial cells pretreated with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) or trametinib for 1 hour. Twenty-four hours later, TNFα secretion by primary murine BMDMs, Raw264.7 macrophages, or BV2 microglial cells was measured by ELISA. Measurement of TNFα secretion in the co-cultures revealed a significant reduction when effector cells were pretreated with trametinib (Fig. 1A–C), without any evidence of toxicity toward treated effector cells (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Trametinib treatment modulates macrophage and microglia anti-viral responses. (A‒C) TNFα release from BMDM (A), Raw264.7 (B), and BV2 (C) pretreated with or without trametinib (100 nM for 1 h), and then overlaid on the indicated primary GBM or glioma cell lines treated with saline or rHSVQ (MOI = 0.1), n = 3/group. (D‒E) Impact of trametinib on macrophage mediated virus clearance. (D) Fluorescent microscopy images of GFP-positive U251T3 human glioma cells, infected with rHSVQ (MOI = 0.01) for 1 h. After thorough washing to remove unbound virus particles, glioma cells were overlaid with DMSO or trametinib pretreated macrophage for 24 hours. Data shown are bright field and fluorescence microscopic images (bottom) of GFP-positive oHSV-infected cells 48 hours post infection. All bars are 100 μm for ×10 magnification images. (E) Quantification of virus yield from patient derived primary GBM and glioma cell lines infected with oHSV alone or co-cultured with primary BMDM cells. Briefly both cells and media were harvested 48 hours after overlay with DMSO or trametinib treated BMDM cells and viral titers were determined by standard plaque forming assay. Data shown are mean virus titer ±SD. *P < 0.05; n = 3/group. (F) Western blot analysis of co-cultures of U251T3 glioma cells with Raw264.7 macrophage cells pretreated with trametinib. U251T3 glioma cells were treated with/without rHSVQ (MOI = 0.5) for 1 h and then overlaid with macrophages pretreated with DMSO or trametinib overnight. Twenty-four hours post overlay, cells were harvested and cell lysates were probed with antibodies against caspase-8 and cleaved PARP. Βeta-tubulin was used as a loading control. Caspase-8 antibody can detect both total and cleaved forms of caspase-8. Arrow head indicates cleaved active form of caspase-8.

The presence of TNFα in the tumor microenvironment has been previously identified as a major barrier to oncolytic virus replication and therapeutic efficacy.8 Therefore, we next evaluated the impact of trametinib on oHSV infection in glioma cells co-cultured with macrophages in vitro. In this study, we used HSV-1 derived oHSV, rHSVQ.9 Human glioma cells infected with oHSV (multiplicity of infection [MOI] = 0.01) were overlaid with control or trametinib-treated murine Raw264.7 macrophages and cultured for 48 hours. Fluorescence microscopy was used to image oHSV-infected cells based on GFP expression (Fig. 1D). Consistent with previous reports, the addition of macrophages to infected glioma cells visibly reduced GFP+ cells. However, this effect was significantly rescued when macrophages were pretreated with trametinib. Similarly, quantification of oHSV-infected glioma cells co-cultured with BMDMs pretreated with or without trametinib revealed a significant increase in oHSV replication upon trametinib treatment (P < 0.001; Fig. 1E).

Infected cell apoptosis by macrophage- or microglia-secreted TNFα is one of the major pathways exploited by human cells to limit HSV-1 spread.8 Thus we examined the effect of trametinib and oHSV treatment on glioma cell apoptosis. Consistent with increased TNFα secretion, when infected glioma cells were co-cultured with macrophages there was an increase in cleaved PARP and cleaved caspase-8 (Fig. 1F). When macrophages were treated with trametinib, however, the apoptotic response in infected glioma cells was diminished. Collectively, these findings suggest that the reduction in TNFα expression and secretion by macrophages treated with trametinib resulted in the suppression of macrophage-mediated apoptotic cell death in oHSV-infected glioma cells, thus increasing virus replication in vitro.

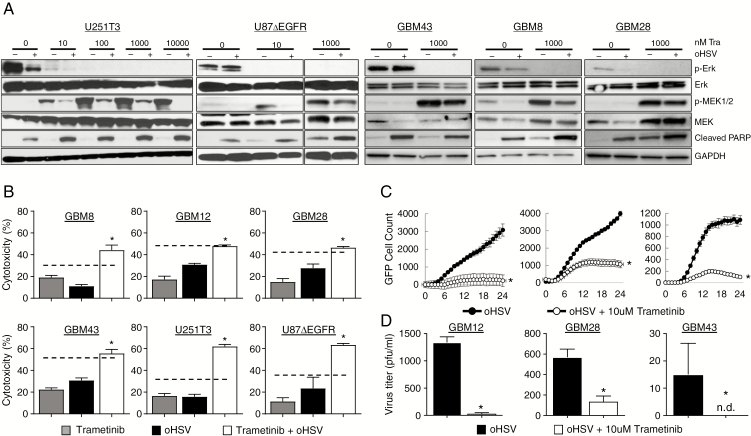

Trametinib Treatment of Glioma Cells Inhibits MEK Signaling and Suppresses Virus Spread

In order to evaluate the impact of trametinib on infected glioma cells in the absence of effector cells, we measured changes in MEK signaling by western blot. Glioma cells were infected with oHSV for 1 h and then treated with the indicated dose of trametinib. Inhibition of MEK1/2 activity by trametinib resulted in an inhibition of the phosphorylation and activation of the downstream ERK kinase pro-survival pathway (Fig. 2A). Interestingly, trametinib treatment resulted in a feedback reactivation of the MEK kinase signaling pathway, as evidenced by increased phosphorylation of MEK following trametinib treatment. This rebound MEK activation has been implicated in the development of resistance to MEK inhibition.10 Importantly, glioma cells co-treated with trametinib and oHSV reduced this feedback activation in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

The combination effect of trametinib and oHSV on glioma cells. (A) Western blot analysis of the indicated cells treated with rHSVQ in the presence or absence of trametinib. The indicated patient derived primary GBM and glioma cells were infected with 0.1 MOI of rHSVQ. One hour post oHSV infection, unbound virus was removed and treated with the indicated concentration of trametinib (0.1‒10 μM). Sixteen hours post treatment, cells were harvested and cell lysates were probed with antibodies against pERK, pMEK1/2, total MEK1/2, total ERK, and cleaved PARP. Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase was used as a loading control. (B) Effects of trametinib and oHSV on glioma cell killing. The indicated cells were infected with oHSV or PBS for 1 hour, followed by treatment with trametinib (10 μM) or DMSO. Seventy-two hours later, cell viability was measured via standard MTT assay. Data shown are mean % of cell death ±SD and analyzed by the paired Student’s t-test (n = 3/group). Dotted line indicates the predicted additive cell killing. (C) Comparison of virus spread in cultures of the indicated glioma cells treated with rHSVQ in the presence or absence of trametinib over time. The indicated glioma cells were infected with rHSVQ and GFP expression was monitored every 2 hours for 24 hours utilizing the Cytation 5 live imaging system. GFP object count was quantified and graphed as an average of 4 wells per treatment group. Data shown are average counts of GFP positive cells ±SD over time. (D) Both cells and media were collected 48 hours post virus infection and virus titers were measured by standard plaque forming assay. Data shown are median titers ±SD (n = 3/group). (N.D. is not detectable).

To evaluate the effect of trametinib in combination with oHSV on glioma cell survival, we measured the viability of the indicated glioma cells treated with either agent alone or in combination. Consistent with the significantly reduced reactivation of the pro-survival MEK signaling pathway, glioma cells treated with both trametinib and oHSV showed significantly greater cytotoxicity compared with cells treated with either agent alone. The combination of the 2 agents was either additive or greater than the predicted additive effect of the 2 individual agents (dotted line) (Fig. 2B). To evaluate if trametinib treatment increased virus replication directly in tumor cells, glioma cells were infected with oHSV and treated with either DMSO or the indicated concentration of trametinib. Viral spread was followed in cultures through quantification of virus-encoded GFP using Cytation 5 Live Cell Imaging over time (Fig. 2C). Additionally, viral replication was measured by a standard plaque forming assay 48 hours post infection (Fig. 2D). Consistent with the known significance of hyperactivated MEK signaling in promoting viral spread,11 we observed reduced virus spread and replication in glioma cells treated with trametinib (Fig. 2C–D). Together, these results suggest that trametinib treatment increases glioma cell sensitivity to trametinib-mediated cell death (Fig. 2).

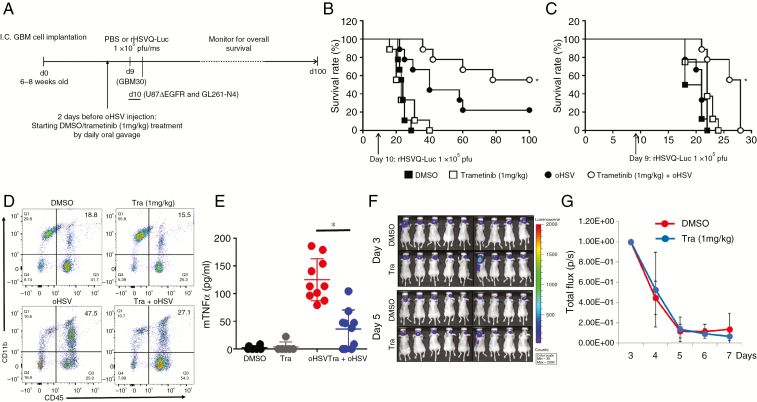

Combination Treatment of Trametinib and oHSV Increases Therapeutic Efficacy In Vivo Independently of Its Effects on Macrophages

While trametinib treatment reduced macrophage inflammatory response to infected cells and increased virus replication in glioma cells co-cultured with macrophage treated cells, it also reduced virus spread when glioma cells were treated with trametinib directly. Since trametinib is thought to poorly penetrate the BBB, we rationalized that its treatment would reduce antiviral inflammatory signaling and provide an oncolytic benefit in vivo. To examine the effect of this combination on tumor growth in vivo, athymic nude mice bearing intracranial tumors (U87ΔEGFR or GBM 30) were treated as shown in the schematic in Fig. 3A. Kaplan–Meier curves revealed a significant improvement in median survival of mice treated with trametinib plus oHSV compared with either agent alone for both tumor models (Fig. 3B–C). Next we investigated the impact of trametinib treatment on the tumor microenvironment of virus-treated glioma-bearing mice. Briefly, mice bearing intracranial glioma were treated as shown in Fig. 3A, brains were harvested, and the tumor-bearing hemispheres were analyzed for infiltrating monocyte derived macrophages (CD45+CD11bhi) by flow cytometry. Consistent with the reduced antiviral response of trametinib treated effector cells (Fig. 1), mice treated with oHSV showed a significant increase in tumor infiltrating monocyte derived macrophages compared with control mice (Fig. 3D, bottom left panel compared with top left panel). Additionally, while trametinib alone had only a modest effect on this tumor infiltrating population compared with control (Fig. 3D, top right panel compared with top left panel), mice receiving both trametinib and oHSV had a significant reduction in the total number of tumor infiltrating monocyte derived macrophages (Fig. 3D, bottom right panel compared with bottom left panel). Consistent with its anti-inflammatory properties, there was a 3.67-fold reduction of TNFα expression in tumors treated with both oHSV and trametinib (Fig. 3E). Reduced antiviral TNFα production along with reduced macrophage infiltration in oHSV treated tumors in nude mice can result in increased viral propagation.12 To evaluate the changes in virus propagation after trametinib treatment in vivo over time, we measured virus-encoded luciferase expression using bioluminescence imaging13 (Fig. 3F–G). Surprisingly, despite a significant reduction in macrophage infiltration and TNFα production (Fig. 3D–E), we observed no significant difference in virus propagation in response to trametinib treatment (Fig. 3F–G), indicating that the effect of trametinib on glioma-bearing mouse survival was independent of increased viral propagation in trametinib treated mice.

Fig. 3.

Impact of trametinib on antitumor efficacy of oHSV in vivo. (A) Schematic representation of animal survival study. (B‒C) Kaplan‒Meier survival curve of mice bearing intracranial tumors treated with DMSO or trametinib and treated with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) or oHSV. Briefly, athymic nude mice bearing intracranial human glioma cells (B‒C) were treated with either DMSO or trametinib (1 mg/kg) by daily oral gavage. Two days after the initiation of gavage (10 days post tumor implantation for U87ΔEGFR) and 9 days post tumor implantation for GBM30), mice were treated with PBS or rHSVQ-Luc (1 × 105 pfu) by intratumoral injection (n = 10/each groups for B‒C). Data shown are Kaplan‒Meier survival curves of mice treated with oHSV and/or trametinib. *P < 0.05 compared with mice receiving single treatment of oHSV. The arrows indicate the time of treatment with oHSV. (D‒G) Intracranial glioma (U87ΔEGFR) bearing mice were treated with DMSO or trametinib (1 mg/kg) by daily oral gavage, starting from day 8 post tumor cell implantation. Ten days post tumor cell implantation, mice were injected with rHSVQ-Luc by direct intratumoral injection. (D) Three days post virus injection, tumor-bearing hemispheres were analyzed for CD11bhigh/CD45+ monocyte derived macrophage infiltration and activation by flow cytometry. Data shown are a representative scatter plot showing CD11bhigh/CD45+ monocyte derived macrophage infiltration in vivo. (E) TNFα levels in brain hemispheres of mice treated with oHSV and trametinib. Twenty-four hours post oHSV injection, tumor-bearing brain hemispheres were homogenized and the supernatants were analyzed for murine TNFα by ELISA (DMSO and trametinib, n = 6; oHSV and trametinib plus oHSV, n = 10). Combination treatment with trametinib and oHSV significantly suppressed murine TNFα compared with oHSV alone. (F‒G) Trametinib effect on virus replication over time. (F) Representative bioluminescence images of mice treated with rHSVQ-Luc showing virus-encoded luciferase activity in mice treated with trametinib or DMSO at the indicated days post virus injection. (G) Quantification of images shown in F, Data shown are mean ±SD of quantification of total flux in each mouse, (n = 9/group).

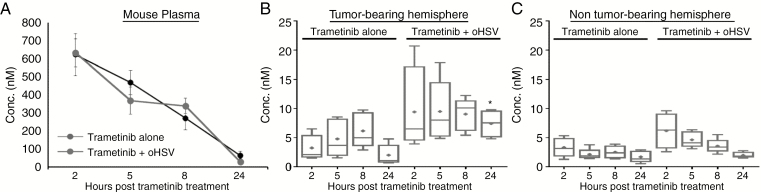

Oncolytic HSV Therapy Enhances Trametinib CNS Penetration

Trametinib has been shown to be a poor BBB permeant drug, with limited brain distribution in mouse models.14 Treatment of brain tumors by oHSV increases endothelial activation in vivo, implying that it could increase penetration of drugs otherwise inaccessible to the central nervous system (CNS).15 Thus, we next evaluated the effect of oHSV infection on CNS penetration of trametinib by LC-MS/MS (Fig. 4A–C). While there was no obvious difference in plasma concentrations of trametinib in mice treated with or without oHSV (Fig. 4A), a significant increase in trametinib concentrations was observed in tumor-bearing brain hemispheres 24 hours after the final trametinib treatment (trametinib concentration in tumor-bearing brain hemisphere: mean values of 20.03 nM vs 74.38 nM; 3.71-fold increase, P < 0.0001, at 24 h) (Fig. 4B). Importantly, this effect was limited to the tumor-bearing brain hemisphere, and there were no significant differences in the distribution of trametinib in the non–tumor bearing brain hemispheres of mice (mean values of 16.56 nM vs 19.89 nM between trametinib alone and trametinib plus oHSV) (Fig. 4C). We next performed a PK analysis of the whole blood data using Phoenix 7.0 Modeling Software; comparative analysis of the PK parameter outputs are summarized in Table 1. The brain-to-plasma percent ratios were calculated using the equation AUCBrain / AUCPlasma *100. These results demonstrate that the addition of oHSV to the trametinib dosing regimen increased the percentage of trametinib distributed to the glioma-bearing brain hemisphere from 18.9% to 132% of plasma exposure (Table 1). There was no difference in trametinib distribution in the non–tumor bearing hemisphere when oHSV was added to the dosing regimen; however, oHSV does appear to shift the PK profile, where the maximum brain-to-plasma concentrations (Cmax) are increased by 49.6% in the tumor bearing hemisphere and 91.2% in the non-tumor bearing hemisphere (Table 1). Additionally, this PK analysis shows there is no difference in trametinib exposure when comparing normal versus tumor burdened tissue in the absence of oHSV; however, when oHSV is added, the trametinib brain-to-plasma percent exposure in the tumor increases by nearly 600%.

Fig. 4.

Impact of oHSV therapy on trametinib brain tumor penetration in vivo. Nude mice bearing intracranial U87ΔEGFR human gliomas were treated as described above. Three days post virus injection, mice were sacrificed at the indicated time following the fifth trametinib treatment and plasma and both brain hemispheres were harvested (n = 5 mice/group). Trametinib concentration in plasma and brain was quantified by LC-MS/MS assay. Concentration-time plot of main PK trametinib in mouse plasma (A), tumor-bearing brain hemisphere (B), and non-tumor-bearing brain hemisphere (C). *P < 0.05 compared with mice treated with single treatment with oHSV.

Table 1.

Relevant comparative analysis of the PK parameters of trametinib. Parameters were estimated by curve fitting of all data and show trametinib brain-to-plasma % ratios for estimated area under the concentration-time curve (AUC) and maximum concentration (Cmax) PK parameters (n = 5, observation per time point)

| Brain-to-Plasma % Ratios for Trametinib PK parameters | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trametinib | Trametinib+oHSV | |||

| PK Parameter | Non-Tumor Bearing Mice Brain Hemisphere | Tumor-Bearing Mice Brain Hemisphere | Non-Tumor Bearing Mice Brain Hemisphere | Tumor-Bearing Mice Brain Hemisphere |

| AUC (h*fmol/μL) | 17.8 | 18.9 | 18.7 | 132 |

| C max (fmol/mg) | 5.12 | 10.0 | 9.79 | 15.0 |

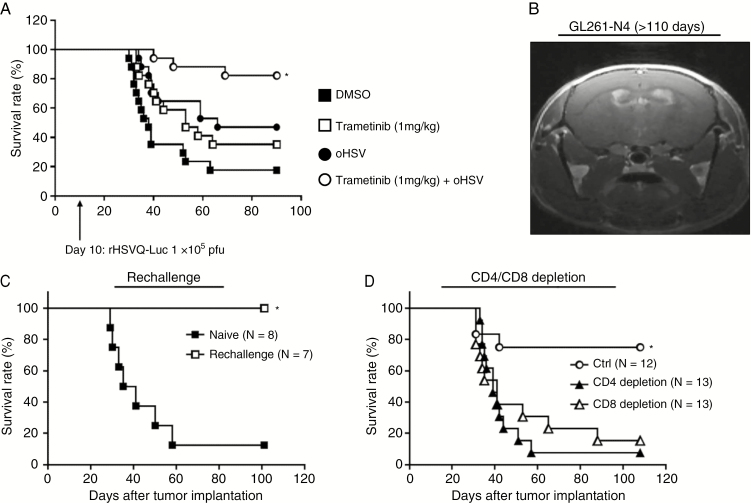

Combining Trametinib with oHSV Therapy Enhances T-cell Mediated Antitumor Efficacy

Collectively, our results showed increased brain penentration of trametinib and enhanced survival benefit of glioma-bearing immune deficient mice treated with trametinib and oHSV. Trametinib treatment also reduced macrophage-induced TNFα, a cytokine that has been implicated in neuroinflammation and glioma growth. However, TNFα has also been described as an important player in the development of antitumor immunity.16 Therefore, we evaluated therapeutic benefit of combining oHSV therapy with trametinib in immune competent mice bearing glioma. Fig. 5A shows Kaplan–Meier survival curves of mice bearing intracranial GL261-N4 glioma treated with oHSV and trametinib. Combination of trametinib with oHSV resulted in a significant improvement in survival compared with either therapy alone, with several mice surviving longer than 100 days post-tumor implantation (median survival: complete regression of 84.5% vs 66 days between oHSV + trametinib and oHSV, P = 0.0194; undetermined vs 53 days between oHSV + trametinib and trametinib alone, P = 0.0184; undetermined vs 38 days between oHSV + trametinib and PBS, P < 0.0001).

Fig. 5.

Combination treatment with trametinib and oHSV enhances T-cell mediated antitumor efficacy. (A) C57BL/6 mice bearing syngeneic murine glioma GL261-N4 cells were treated with either DMSO or trametinib (1 mg/kg) by daily oral gavage. Two days after initiation of gavage (10 days post tumor implantation), mice were treated with phosphate buffered saline or rHSVQ-Luc (1 × 105 pfu) by intratumoral injection (n = 17/each groups). Data shown are Kaplan‒Meier survival curves of mice treated with oHSV and/or trametinib. *P < 0.05 compared with mice receiving single treatment with oHSV. The arrows indicate the time of treatment of oHSV. (B) Representative MRI image of a C57BL/6 mouse treated with oHSV and trametinib in Fig. 5A 110 days after tumor cell implantation. (C) Mice treated with the combination trametinib and oHSV and surviving more than 100 days were rechallenged with a second intracranial GL261-N4 injection into the left hemisphere and compared with age matched naïve C57BL/6 mice (n = 7). Mice were monitored for up to 100 days and survival was analyzed by Kaplan–Meier. *P < 0.05. (D) Intracranial GL261-N4-bearing C57BL/6 mice were treated with trametinib and oHSV as described above as well as with isotype control, anti-CD4, or anti-CD8 depleting antibodies by intraperitoneal injection 2, 4, and 7 days post virus therapy (isotype control, n = 13; anti-CD4, n = 14; anti-CD8, n = 14). *P < 0.05 compared with CD4 or CD8 depletion.

Approximately 80% (14/17) of mice treated with both trametinib and oHSV survived longer than 100 days post tumor cell implantation with no visible signs of tumor burden, suggesting a complete eradication of the tumor. MRI of the surviving mice confirmed a complete response (Fig. 5B). To evaluate the possibility of memory T-cell generation to oHSV infection, we rechallenged the surviving mice with tumor cells administered to the contralateral hemisphere (Fig. 5C). While age matched control mice died of tumor burden, 100% of the treated mice that were rechallenged remained alive. This indicated a complete rejection of tumors in the surviving mice, and implied the development of a memory T-cell antitumor immunity. To evaluate the role of T cells in tumor rejection, we evaluated the therapeutic efficacy of combining trametinib and oHSV in mice with CD4 or CD8 T-cell depletion. Survival advantage of combination therapy with both trametinib and oHSV was reduced when mice were treated with T-cell depleting antibodies (Fig. 5D). Collectively, these results indicate that the survival benefit achieved by the combination of trametinib plus oHSV is dependent on both CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell subsets, which have the capacity to form a strong effector memory activation in the event of antigen re-exposure.

Discussion

GBM is the most common and deadly primary brain malignancy in adults; patients diagnosed have a median survival of less than 2 years.1,17 Nearly all tumors recur and are often resistant to chemotherapy, leaving few options available to delay disease progression.18 The RAS-RAF-MEK-ERK pathway is one of the most frequently dysregulated signal transduction pathways in cancer and plays a critical role in tumorigenesis, cell proliferation, and inhibition of apoptosis. Although RAF mutations are a rare event in GBM, these tumors are known to be addicted to this mitogenic signaling cascade,7 and thus targeting this pathway for GBM tumors is a relevant choice. Inhibition of MEK signaling is an attractive therapeutic target and is currently under investigation. Reactivation of MEK signaling after treatment with trametinib, through the relief of a feedback control regulated by ERK kinase, remains a significant mechanisim of acquired resistance.19,20 Here we examined trametinib in combination with oHSV therapy and found that treatment with oHSV could resist the increased MEK activation that occurs in tumor cells after treatment with trametinib and result in a significant increase in tumor cell sensitization to MEK inhibition.

Trametinib treatment also resulted in a significant suppression of macrophage/microglia infiltration to the tumor bed, along with a reduction in TNFα secretion. Macrophages are among the first line of defense to an invading pathogen such as a virus,21 and are a major source of the pro-inflammatory cytokine, TNFα. While low dose TNFα can enhance antitumor efficacy,22,23 at high doses it is associated with toxicity.24 In a phase I clinical trial, systemic administration of TNFα in patients with advanced malignancy refractory to previous standard therapy was associated with a significant toxicity profile, with only 3 out of 57 evaluable patients demonstrating a partial tumor regression.22 Thus, the modulation of TNFα by trametinib might also control inflammation associated toxicity.

Interestingly, despite a reduction in inflammation, combination therapy significantly enhanced antitumor immunity in immune competent mice. Several studies have shown that activated mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling in cancer cells downregulates the expression of major histocompatibility complex I (MHC-I) on the tumor cell surface, enabling immune escape.25 MEK inhibition can circumvent this effect, resulting in increased MHC-I cell surface expression and activation of CD8+ cytotoxic lymphocytes.26 Therapy with oHSV also induces immunogenic activation in the tumor microenvironment, resulting in an antitumor immune response.27 Here we showed that combining trametinib with oHSV resulted in complete tumor regression in almost 80% of the mice. These long-term survivors then rejected subsequent tumor implantation. We went on to show that this survival benefit was dependent on both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, which also conveyed long-term protection as tumor growth was completely inhibited upon rechallenge in the surviving mice. MEK is an emerging target in cancer immunotherapy research, and preclinical studies have suggested that MEK inhibitors potentiate the antitumor T-cell response when used as both a monotherapy and in combination.26 For example, the combination of BRAF and MEK inhibition induces programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) expression on melanoma cells, sensitizing them to anti–PD-1 checkpoint blockade.28 Additional preclinical studies have also shown that trametinib combined with the BRAF inhibitor dabrafenib enhances antitumor immunity28 and synergizes with other immunotherapies. Thus, it would be interesting to test a triple combination including trametinib, oHSV, and immune checkpoint inhibition for the treatment of glioma.

Trametinib is known to have poor CNS penetrance and limited brain distribution in the intracranial glioma-bearing mice xenograft model.14 Thus, despite activation of RAS signaling in brain tumors, its clinical usage has been limited. Here we identified that oHSV therapy could enhance CNS penetration of trametinib, resulting in increased therapeutic efficacy. PK analysis of brain tissue from mice uncovered a significant increase in trametinib penetration and distribution in tumor bearing hemisphere after oHSV therapy. We recently showed that mice bearing intracranial gliomas treated with oHSV have increased endothelial cell activation and vascular leakiness in the brain.15 This is the first report to our knowledge that has shown increased BBB penetration of a drug with oHSV therapy. The results from this study are therefore directly applicable to current clinical testing, and will help guide researchers and clinicians for the development of future clinical programs.

Funding

This work was supported by R01 NS064607, R01 CA150153, and P01CA163205 (to Balveen Kaur) and the American Cancer Society/Joe & Jessie Crump Foundation and North Texas Pay-if Group (to Jessica Swanner).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the Pharmacoanalytical Shared Resource center (PhASR) within the James Comprehensive Cancer Center, all at The Ohio State University, for their services.

Conflict of interest statement. The authors disclose no potential conflicts of interest.

Authorship statement. Conceptualization, J.Y.Y. and B.K. Methodology and investigation, J.Y.Y., J.S., Y.O., M.N., F.P., Y. B., J.L, A.C.L. B.H., F.G., D.B., and H.Q. Data analysis, J.Y.Y., J.S., Y.O., M.N., F.P., J.L, A.C.L. D.B., M.P., D.G., T.J.L., and B.K. Writing, review, and editing, J.Y.Y. and B.K. All authors edited and reviewed manuscript.

References

- 1. Jo J, Wen PY. Antiangiogenic therapy of high-grade gliomas. Prog Neurol Surg. 2018;31:180–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Saha D, Wakimoto H, Rabkin SD. Oncolytic herpes simplex virus interactions with the host immune system. Curr Opin Virol. 2016;21:26–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sanchala DS, Bhatt LK, Prabhavalkar KS. Oncolytic herpes simplex viral therapy: a stride toward selective targeting of cancer cells. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Alvarez-Breckenridge C, Kaur B, Chiocca EA. Pharmacologic and chemical adjuvants in tumor virotherapy. Chem Rev. 2009;109(7):3125–3140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Long GV, Stroyakovskiy D, Gogas H, et al. Dabrafenib and trametinib versus dabrafenib and placebo for Val600 BRAF-mutant melanoma: a multicentre, double-blind, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;386(9992):444–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brennan CW, Verhaak RG, McKenna A, et al. ; TCGA Research Network The somatic genomic landscape of glioblastoma. Cell. 2013;155(2):462–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. de Gooijer MC, Zhang P, Weijer R, Buil LCM, Beijnen JH, van Tellingen O. The impact of P-glycoprotein and breast cancer resistance protein on the brain pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of a panel of MEK inhibitors. Int J Cancer. 2018;142(2):381–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Meisen WH, Wohleb ES, Jaime-Ramirez AC, et al. The impact of macrophage- and microglia-secreted TNFα on Oncolytic HSV-1 therapy in the glioblastoma tumor microenvironment. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21(14):3274–3285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Terada K, Wakimoto H, Tyminski E, Chiocca EA, Saeki Y. Development of a rapid method to generate multiple oncolytic HSV vectors and their in vivo evaluation using syngeneic mouse tumor models. Gene Ther. 2006;13(8):705–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Duncan JS, Whittle MC, Nakamura K, et al. Dynamic reprogramming of the kinome in response to targeted MEK inhibition in triple-negative breast cancer. Cell. 2012;149(2):307–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Farassati F, Yang AD, Lee PW. Oncogenes in Ras signalling pathway dictate host-cell permissiveness to herpes simplex virus 1. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3(8):745–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Delwar ZM, Kuo Y, Wen YH, Rennie PS, Jia W. Oncolytic virotherapy blockade by microglia and macrophages requires STAT1/3. Cancer Res. 2018;78(3):718–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Power-Grant O, Bruen C, Brennan L, Giblin L, Jakeman P, FitzGerald RJ. In vitro bioactive properties of intact and enzymatically hydrolysed whey protein: targeting the enteroinsular axis. Food Funct. 2015;6(3):972–980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Vaidhyanathan S, Mittapalli RK, Sarkaria JN, Elmquist WF. Factors influencing the CNS distribution of a novel MEK-1/2 inhibitor: implications for combination therapy for melanoma brain metastases. Drug Metab Dispos. 2014;42(8):1292–1300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hong B, Muili K, Bolyard C, et al. Suppression of HMGB1 released in the glioblastoma tumor microenvironment reduces tumoral edema. Mol Ther Oncolytics. 2019;12:93–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sivick KE, Desbien AL, Glickman LH, et al. Magnitude of therapeutic STING activation determines CD8(+) T cell-mediated anti-tumor immunity. Cell Rep. 2018; 25(11):3074–3085 e3075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Stupp R, Taillibert S, Kanner A, et al. Effect of tumor-treating fields plus maintenance temozolomide vs maintenance temozolomide alone on survival in patients with glioblastoma: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;318(23):2306–2316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jiang H, Alonso MM, Gomez-Manzano C, Piao Y, Fueyo J. Oncolytic viruses and DNA-repair machinery: overcoming chemoresistance of gliomas. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2006;6(11):1585–1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ballif BA, Blenis J. Molecular mechanisms mediating mammalian mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) kinase (MEK)-MAPK cell survival signals. Cell Growth Differ. 2001;12(8):397–408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Roberts PJ, Der CJ. Targeting the Raf-MEK-ERK mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade for the treatment of cancer. Oncogene. 2007;26(22):3291–3310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Aurelian L. Oncolytic viruses as immunotherapy: progress and remaining challenges. Onco Targets Ther. 2016;9:2627–2637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gamm H, Lindemann A, Mertelsmann R, Herrmann F. Phase I trial of recombinant human tumour necrosis factor alpha in patients with advanced malignancy. Eur J Cancer. 1991;27(7):856–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Johansson A, Hamzah J, Payne CJ, Ganss R. Tumor-targeted TNFα stabilizes tumor vessels and enhances active immunotherapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(20):7841–7846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Han ZQ, Assenberg M, Liu BL, et al. Development of a second-generation oncolytic Herpes simplex virus expressing TNFalpha for cancer therapy. J Gene Med. 2007;9(2):99–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Brea EJ, Oh CY, Manchado E, et al. Kinase regulation of human MHC class I molecule expression on cancer cells. Cancer Immunol Res. 2016;4(11):936–947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ebert PJR, Cheung J, Yang Y, et al. MAP kinase inhibition promotes T cell and anti-tumor activity in combination with PD-L1 checkpoint blockade. Immunity. 2016;44(3):609–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Saha D, Martuza RL, Rabkin SD. Oncolytic herpes simplex virus immunovirotherapy in combination with immune checkpoint blockade to treat glioblastoma. Immunotherapy. 2018;10(9):779–786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sanlorenzo M, Vujic I, Floris A, et al. BRAF and MEK inhibitors increase PD-1-positive melanoma cells leading to a potential lymphocyte-independent synergism with Anti-PD-1 antibody. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24(14):3377–3385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.