ABSTRACT

The chief registrar (CR) scheme allows registrars to gain clinical leadership and quality improvement skills. Some regions have low uptake and non-physician CRs are uncommon. This study aims to establish the reasons behind this in one such region. A survey was distributed at two events in a low uptake area; a Royal College of Physicians update in medicine day and a general medicine teaching day.

One-hundred and ninety-one clinicians responded; including 103 (53.9%) higher specialty trainees (ST3+) and 74 (38.7%) consultants. Seventy-two (44.5%) respondents were interested or unsure about applying for the role. Several misconceptions were observed, including a need for prior management experience or training in general internal medicine. Fifty (41.3%) respondents, who were not interested in applying, listed not knowing ‘what the role entails’ as influencing their decision.

There was significant interest in the CR role, however, misconceptions were common. Improved information regarding the role may improve recruitment both in areas of low uptake and when attracting applicants from non-physician specialties.

KEYWORDS: Chief registrar, leadership, quality improvement

Introduction

The Royal College of Physicians (RCP) chief registrar (CR) scheme was developed following the Future Hospital Commission report to develop leadership skills among senior medical trainees.1 The first cohort started in September 2016 with subsequent cohorts starting annually. In the 2018 cohort, there were 56 CRs nationwide including both physician trainees and trainees from other specialties.

The scheme is open to higher specialty trainees (HSTs) at ST4 or above. It can be undertaken over 12–18 months and can be completed as an in-programme (IP) or an out-of-programme (OOP) experience. CRs continue to undertake clinical work while 40–50% of their time is dedicated to CR scheme activity. Five modules of specifically tailored training are provided by the RCP education team, lasting 2 days each. CRs are mentored by senior leaders within their host organisation to aid their development and provide support and guidance. There has been an independent evaluation undertaken by the Health Services Management Centre at the University of Birmingham demonstrating significant benefit for both the trust and the CR.2

Uptake of the CR scheme in the West Midlands has been limited so far. In the first and second cohorts of CRs, only a single trust had a CR in post. In the 2018 cohort, four trusts had a CR, however several posts throughout the region were unfilled and competition for each post was limited. Anecdotally, there appear to be significant misconceptions of the CR scheme among both trainees and consultants. This is to be expected considering the varied opportunities available for trainees to undertake leadership roles.

We sought to establish what trainees and consultants understood about the scheme and to provide information to address any misconceptions in an attempt to reduce barriers to trainees applying to become a CR. This is relevant not only to our own region and other areas of low uptake but may also assist the RCP in rolling out the scheme to non-physician trainees.

Methods

A survey was used to assess knowledge of the CR role and factors that influence applications for the post. The survey consisted of multiple-choice questions and a free-text box asking what responders thought the role involved and any other additional comments.

The survey was distributed at two separate events. The first was at the RCP update in medicine meeting in Birmingham, November 2018. This event can be attended by anyone but is primarily focused on the educational needs of HSTs training in general internal medicine (GIM) and consultants in physician specialties. Paper surveys were distributed to delegates on arrival, placed on tables and handed out at a CR information stand.

The survey was distributed a second time at the GIM regional teaching day at University Hospital Birmingham, December 2018. This event is part of an educational programme attended by registrars training in GIM in the West Midlands. Attendance at four such events per year is mandatory. Both paper and electronic surveys (Google forms) were circulated.

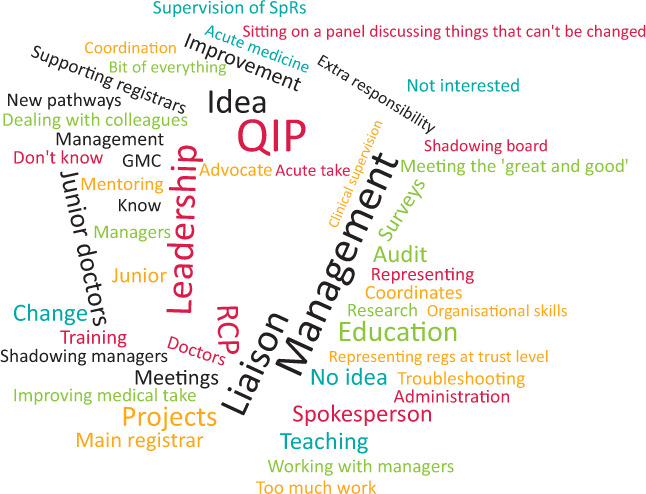

Objective survey responses were displayed in graphical form. A word cloud where the size of the font corresponds to the frequency of the reply ie more frequently used terms appear larger.

Following the second survey distribution a presentation was given at the GIM regional teaching day describing the CR scheme to remove misconceptions, descriptions of projects undertaken by the authors (2018 CR cohort) and early success stories. An opportunity was given to discuss the role with CRs following this or later via email. The number of CRs and rate of successful appointments in 2018/19 and 2019/20 was provided by the RCP.

Results

Response rates

Following data collection at the regional RCP update and the GIM training day, 191 responses were completed. Seventy-seven per cent were in paper form and 23% electronic. Fifty-five per cent of responders were registrars in training (ST3 or above) and 39% were consultants (Table 1). Due to the nature of the RCP update and GIM training days, 99% of those completing the surveys were working within a medical specialty.

Table 1.

Respondent grade

| Grade | n (%) |

|---|---|

| ST3–ST5 | 72 (37.7) |

| ST6 and above | 31 (16.2) |

| Consultant | 74 (38.7) |

| Other | 14 (7.3) |

Perceptions of eligibility and impact on clinical training

A majority of respondents, 78%, had heard of the chief registrar role before. One of the most common beliefs (59%) was that only trainees performing GIM could apply to the role, with a further 23% thinking only final-year trainees could apply. Many also responded that the CR role is only applicable to those with management experience or future leadership aspirations (40%; Table 2).

Table 2.

Questions relating to applications for the role

| Question | Response | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Who can apply for the rolea,b | Only final-year SpRs | 39 (22.7) |

| Only SpRs doing GIM as part of their training | 102 (59.3) | |

| Only SpRs with experience of ‘management’ | 46 (26.7) | |

| Only SpRs with ambitions to be ‘senior medical leaders’ | 68 (39.5) | |

| Would you be interested in applying for the rolea | Yes | 28 (17.3) |

| No | 90 (55.6) | |

| Unsure | 44 (27.2) | |

| If not interested in applying for the role, what has influenced your decisiona,b | My trust of choice did not offer the role | 13 (10.7) |

| I wasn't aware the role existed | 20 (16.5) | |

| I don't know what the role entails | 50 (41.3) | |

| Unlikely to be successful | 11 (9.1) | |

| It would harm my clinical training | 7 (5.8) | |

| Training programme director unsupportive | 4 (3.3) | |

| Would you prefer to do the role in programme or out of programmea | In programme | 74 (68.5) |

| Out of programme | 19 (17.6) | |

| Unsure or not interested | 15 (13.9) | |

| What information would you find usefula,b | Examples of ‘a day in the life’ of a chief registrar | 92 (80) |

| More information on the application process | 57 (49.6) | |

| Examples of skills developed as a chief registrar | 86 (74.8) | |

| More information on the training provided by the RCP | 65 (56.5) |

a = response rates to each question varied, therefore percentages vary between questions;

b = questions permitted respondents to select multiple responses; GIM = general internal medicine; RCP = Royal College of Physicians; SpR = specialist registrar.

Less than half of respondents (45%) knew that applicants could choose to complete the post either IP or OOP, with 39% answering that it increases training and 18% stating that it did not. Despite these answers, there appeared to be recognition that the CR post occurred alongside clinical work with only 9% thinking otherwise. Fewer still stated that harm to their clinical training would be a reason not to be interested in a CR post (6%; Table 2).

Applications to the role in the future

When considering applying for future posts, almost half of registrars indicated they were either interested (17%) or unsure (27%) about the CR role. Although a group reported they had researched the role and were not interested, they were uncommon (12%) compared to those that didn't know what the role entails (41%; Table 2).

Perceptions of the content of the role

A free text question asking what respondents thought the role involved, and any other additional comments are displayed using a word cloud (Fig 1). Many of the responses correctly identified what the role involves (eg quality improvement, leadership and management), however, several answers indicated the role had an education/teaching or research component. Although there may be research or education elements to the role, this would depend on the projects an individual CR chooses to do, as there is no expectation to complete either as part of the role.

Fig 1.

Word cloud of free text responses to ‘What do you think the role [of chief registrar] involves?’ Free text responses that were more common are represented by larger font size. GMC = General Medical Council; QIP = quality improvement project; RCP = Royal College of Physicians; regs = registrars; SpR = specialist registrar.

This question also highlighted some negative comments regarding the role including ‘sitting on a panel discussing things that can't be changed’ and ‘meeting the great and the good’.

Appointments

Comparing recruitment in the West Midlands between 2018/19 and 2019/20 there were four and seven chief registrars, respectively. The rate of successful appointments was 4/7 (57%) and 7/11 (64%), respectively. The programme grew nationally from 56 to 71 CRs in the same period.

Discussion

The survey data described above demonstrates that more than three-quarters of those surveyed were aware of the role, suggesting that it is now widely recognised among doctors working in medical specialties. However, a significant number of misconceptions and uncertainty regarding the CR role remain. Uncertainty regarding the job role was potentially a major barrier to applications in the West Midlands which is likely to be representative of other low uptake regions.

Both the number of CRs and the rate of successful appointments numerically increased in the West Midlands in the year following this survey. However, as the programme has also grown, it is not possible to attribute this difference to the publicity provided by this survey or associated presentations.

The most concerning responses were those that suggested the role was only applicable to those with higher management ambitions, including more than one-third of respondents. Several responses also suggested participation in managerial duties to be a waste of time, such as ‘meeting the great and good’ or ‘sitting on panel discussing things that can't be changed’. Fortunately, such negative comments were much less common than more positive responses. This is potentially less specific to the individual CR role, but instead driven by cynicism towards those in management roles. Such responses also likely reflect frustration with current challenges in the working environment, and those perceived to be responsible. A consultant role incorporates more than just clinical work, but is also a leadership role, even in the absence of a formal position in the trust management. There is emerging evidence that clinicians undertaking senior leadership roles within a trust are associated with better quality of care.3,4

Free text responses also highlighted many accurate components of the role including quality improvement and leadership, albeit with a few more benign misconceptions such as ‘General Medical Council (GMC)’, ‘spokesperson’ and ‘teaching’. This suggests that although a core understanding of the role is held by many, there are still significant misconceptions to dispel. It seems clear that more detail regarding the role and what CRs spend their time doing may help potential applicants come to a decision.

Although the present study has captured a large number of doctors within medical specialties, they are based within the West Midlands, an area with lower uptake compared to other deaneries. Therefore, the misconceptions seen may be more prevalent compared to the rest of the UK.

Other leadership development opportunities are available within the NHS. The Faculty of Medical Leadership and Management (FMLM) National Medical Director's Clinical Fellow Scheme provides an OOP experience.5 Fellows are seconded from their employing trust for 12 months to a variety of healthcare affiliated organisations including NHS England, the GMC and Bupa, among others. Therefore, there is no clinical work undertaken during the fellowship and it cannot be counted as time towards training. These schemes are excellent at providing exposure to senior leadership and developing skills in healthcare policy, strategy and project management. However, as a result they provide less exposure to frontline healthcare leadership and quality improvement.

The RCP flexible portfolio training scheme is an alternative opportunity to develop leadership skills.6 This is an integrated pathway for ST3 registrars to spend a day per week undertaking non-clinical project work of which quality improvement is an option. Trainees remain in the scheme for at least 1 year, although they are able to continue subject to receiving a satisfactory annual review of competency progression (ARCP) outcome. This provides a very clinically orientated experience with the additional benefit of protected time to develop. Compared with the CR scheme, the flexible portfolio provides less protected time, and there is less focus on clinical leadership.

Given these alternative schemes, it is important that communication regarding the CR scheme clarifies the differences between them. Following the survey data described above, we have presented on the CR role at regional GIM training and specialty training days, and met with potential applicants for 2019–2020, educational leads and programme directors to explain the role. CR posts in the West Midlands for 2019–2020 have increased, as have the rate of successful appointments in the year following this survey.

Conclusions and future recommendations

To further disseminate the CR scheme in regions of low uptake and potentially also among non-medical specialties, it is important to provide more information. Details of the CR role such as examples of projects undertaken, generic skills developed and ‘a day in the life’ style insights may help potential candidates better appraise the scheme. Dispelling common myths regarding who the role is intended for may also help to attract a broader range of interested candidates.

Our presented data results from clinicians in medical specialties. Therefore, although the conclusions drawn from it may be applicable to non-medical specialties, to drive increased uptake from that group, non-medical specialties should be surveyed separately.

We believe that the CR role will continue to increase in popularity and provide an excellent opportunity for future senior clinicians to develop management and leadership skills. Through providing more information, we believe the CR role can be embedded in an increasing number of trusts nationally.

References

- 1.Future Hospital Commission Future hospital: caring for medical patients. A report from the Future Hospital Commission to the Royal College of Physicians. London: Royal College of Physicians; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Exworthy M, Snelling I. Evaluation of the RCP's Chief Registrar programme. Birmingham: University of Birmingham; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goodall AH. Physician-leaders and hospital performance: Is there an association? Soc Sci Med 2011;73:535–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clay-Williams R, Ludlow K, Testa L, Li Z, Braithwaite J. Medical leadership, a systematic narrative review: do hospitals and healthcare organisations perform better when led by doctors? BMJ Open 2017;7:e014474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Faculty of Medical Leadership and Management National Medical Director's Clinical Fellow Scheme. FMLM; www.fmlm.ac.uk/programme-services/individual-support/national-medical-directors-clinical-fellow-scheme [Accessed 16 May 2019]. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Royal College of Physicians Flexible portfolio training pathways. RCP; www.rcplondon.ac.uk/projects/outputs/flexible-portfolio-training-pathways [Accessed 16 May 2019]. [Google Scholar]