Abstract

Background

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the NHS has implemented significant workforce changes to manage the increased and changing demand on healthcare services. We aimed to investigate the impact of redeployment on the wellbeing of doctors as well as highlighting ways to improve.

Methods

We conducted a survey at three NHS trusts over 2 weeks asking redeployed doctors to rate their morale, work–life balance and perceived support and safety, and to voice concerns.

Results

172 redeployed doctors responded to the survey. 66.3% felt confident in their new role, 65.7% felt satisfied or neutral with their new role and only 31.4% felt stressed at work. 66.3% felt valued by their team and 79% felt valued by the general public. 64.5% had noticed an increase in the length of breaks and 89% felt their rotas provided sufficient respite. 55.2% did not feel confident in the guidance from Public Health England/Wales on using personal protective equipment (PPE) and 54.7% did not feel safe while wearing PPE. The three most common concerns were training opportunities, PPE and family health.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that morale is higher than might be expected with doctors feeling valued, confident and well rested in their new role. Concerns about training opportunities/career progression, PPE and family safety need to be addressed.

KEYWORDS: Wellbeing, redeployed, COVID-19, morale, training

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to unprecedented pressures on healthcare systems across the world.1 Globally, the effect of an increase in demand on healthcare services as a result of the large number of individuals presenting with COVID-19, and the resultant stretching of resources, has presented a major challenge for health services. In response to this, hospitals have had to implement many significant changes in the way the workforce is managed. Specifically, across many hospital trusts in the UK, doctors have been redeployed from their usual positions into COVID-19-specific roles, been moved away from elective specialty work, and have had their working patterns changed.

COVID-19 is likely to have ongoing effects on the NHS for years to come;2 therefore it is important to keep doctors physically, mentally, and emotionally supported through the pandemic. In addition to the usual pressures of working as a doctor within the NHS, doctors who have been redeployed in response to the pandemic have faced further challenges. These include working in unfamiliar environments, last minute rota changes – which can sometimes be frequent – and fewer specialist training opportunities, which resulted in concerns about career progression. It is essential to identify and address these issues in order to ensure that we protect the wellbeing of healthcare staff. By looking after the physical and mental health of staff, healthcare systems can build a sustainable service, with a workforce that can deliver high quality care and maintain productivity.3,4

Health Education England's 2019 Pearson report highlights the importance of promoting and supporting the wellbeing of NHS staff.5 It references several key factors for the wellbeing of healthcare workers, including morale, work–life balance, support, autonomy and safety; failure to optimise these can lead to fatigue and burnout. Currently, there is a paucity of data on how redeployment affects the wellbeing of doctors during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Our study aimed to address this lack of information. A comprehensive survey, designed around the key principles found in the Pearson report, was used to gain insight into the wellbeing of doctors redeployed for COVID-19.5 An analysis of its findings has allowed us to suggest avenues to pursue to improve support.

Methods

This was a cross-sectional study that involved distributing a questionnaire across three major UK trusts – the Royal Free London NHS Foundation Trust (RFL), University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (UCLH), and Cardiff and Vale University Health Board (CAV) – for two weeks from 22 April 2020 to 6 May 2020. The questionnaire was designed by a multidisciplinary team of clinicians, including medical education directors, wellbeing advisors, junior doctors and consultants. The questionnaire was composed of six sections, covering demographics, morale, work–life balance, support, safety and concerns. Morale was further broken down into confidence, satisfaction, stress and value (from team and from the public). An ordinal Likert scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) was used to rate morale and level of support. Work–life balance was explored by asking about the effect of work on the length of breaks, sleep and exercise. In addition, respondents selected their key concerns from a list of 10 factors formulated by the authors, and had a free-text option to communicate any others. Respondents were also asked to give free-text suggestions on how to make them feel safer at work and how to improve their wellbeing.

A link to the questionnaire was distributed to all doctors in the COVID-19 workforce. Redeployment was defined as being moved from their usual role to any new role. Doctors that had not been redeployed were excluded from analysis. Consent for the use of anonymised data was gained from every participant. Formal ethical approval was not sought as the study was considered by all hospitals to be a service improvement project.

Free text comments were analysed by the authors to create central themes using the grounded theory approach.

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM® SPSS V26.0. Kruskal–Wallis test was used to compare differences in responses between hospitals; Chi-squared test of independence was used to examine the relationship between confidence in Public Health England/Public Health Wales (PHE/PHW) guidance on personal protective equipment (PPE) and feeling safe in PPE; Mann-Whitney U test was used to examine the relation between confidence in PHE/PHW PPE guidance and feeling confident, satisfied, stressed at work.

Results

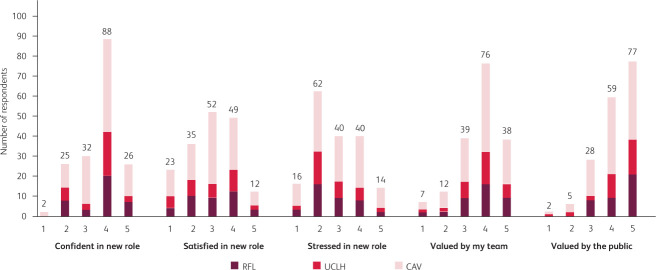

Over the two-week period, we received 222 completed questionnaires from a total of 1,193 (18.6%) doctors contacted. 50 respondents had not been redeployed and were excluded. Therefore, a total of 172 responses were used for analysis. Responses varied between hospital trusts and were the highest from CAV with 100 respondents (58.1%) vs 38 (22.1%) from RFL and 34 (19.8%) from UCLH. Respondents were from a range of grades: 72 foundation trainees (42%), 45 core/specialty trainees 1–3 (24%), 39 higher specialty trainees 4–7 (23%) and 19 consultants (11%). Respondents were redeployed from 34 different specialities to new roles (Fig 1).

Fig 1.

Areas of redeployment.

Morale

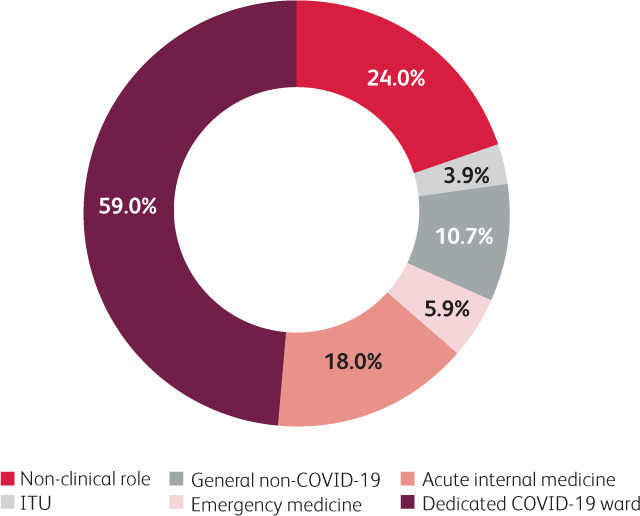

Of the doctors surveyed, 114 (66.3%) felt confident in their new role; only 54 (31.4%) felt stressed at work; 114 (66.3%) felt valued by their team; 136 (79%) felt valued by the general public; and 113 (65.7%) felt either satisfied or neutral with their new role (Fig 2). There was no statistically significant difference in responses between any of the hospitals for any of the categories.

Fig 2.

Morale of redeployed doctors. Doctors were asked to what extent they agreed with the statements given. Responses were recorded on an ordinal Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neutral, 4 = agree, 5 = strongly agree). CAV = Cardiff and Vale University Health Board; RFL = Royal Free London NHS Foundation Trust; UCLH = University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust.

Work–life balance

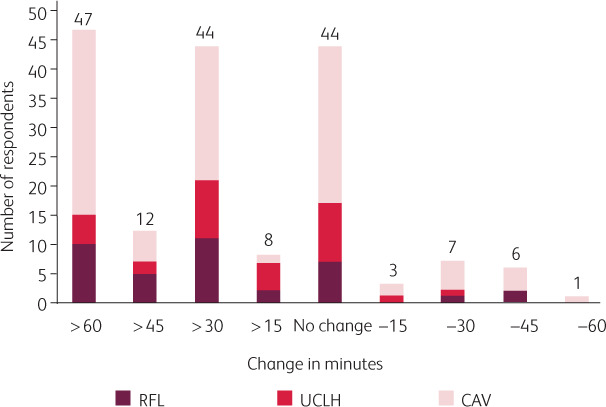

The majority of doctors surveyed (n=111, 64.5%) reported an increase in the length of breaks they had during day shifts, with 47 (27.3%) having over 60-minutes increase (Fig 3). Furthermore, 153 (89%) redeployed doctors felt that their rotas provided sufficient respite between shifts. For 98 (57%) respondents there was no change in the duration of sleep, although 60 (34.9%) reported a reduction in theirs. 67 (39%) respondents noticed a decrease in the amount of exercise they were able to do over a week.

Fig 3.

Change in breaks after redeployment. Doctors were asked whether the duration of their breaks increased or decreased compared to previous rotations. CAV = Cardiff and Vale University Health Board; RFL = Royal Free London NHS Foundation Trust; UCLH = University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust.

Support

Only half of doctors (n=83, 48.3%) reported feeling supported by hospital administration. Even fewer felt supported by their supervisors: 60 (34.9%) and 46 (26.7%) for clinical supervisors and educational supervisors respectively.

Safety

Only 142 (82.6%) respondents felt that they were adequately trained to use PPE, which included a combination of classroom ‘donning and doffing’ 113 (65.7%), fit testing 114 (66.3%), fit checking 36 (20.9%), and online resources 62 (36%). However, over half of respondents (n=95, 55.2%) did not feel confident in the PHE/PHW PPE guidance and 94 (54.7%) of redeployed doctors did not feel safe while wearing PPE. There was also no statistically significant difference between the hospitals. There was a statistically significant relationship between confidence in PHE/PHW PPE guidance and feeling safe in PPE: X2 (1, N=168)=47.226, p<0.001. Clinicians who felt confident with the PPE guidance were more likely to report feeling safe, and the reverse is true for those who were not confident in PPE guidance. We also found that respondents who were confident in the PHE/PHW PPE guidance felt significantly more confident in (u=2927.5, n=172, p=0.015) and satisfied with (u=2939, n=172, p=0.022) their new roles, but interestingly there was no significant effect on feeling stressed, (u=4140.5, n=172, p=0.122) (Table 1). We noted that 39 (22.7%) believed they were at an increased risk of being involved in an adverse event because they were working beyond their level of competence. When asked to give a free text response to ‘what would make you feel safer?’, common themes included provision of PPE as per the World Health Organization's (WHO) guidance, changing/showering facilities, and a daily supply of scrubs.

Table 1.

The relationship between confidence in public health PPE guidance and feeling confident, satisfied, and stressed at work

| Mean rating of doctors confident in PPE guidance | Mean rating of doctors not confident in PPE guidance | p values | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Confidence in workplace | 3.83 (SD±0.88) | 3.48 (SD±0.99) | 0.015 |

| Satisfaction in workplace | 3.17 (SD±1.17) | 2.76 (SD±1.10) | 0.022 |

| Stress in workplace | 2.70 (SD±1.11) | 2.97 (SD±1.13) | 0.122 |

Mean values were calculated based on Likert scale responses (1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neutral, 4 = agree, 5 = strongly agree).

Concerns

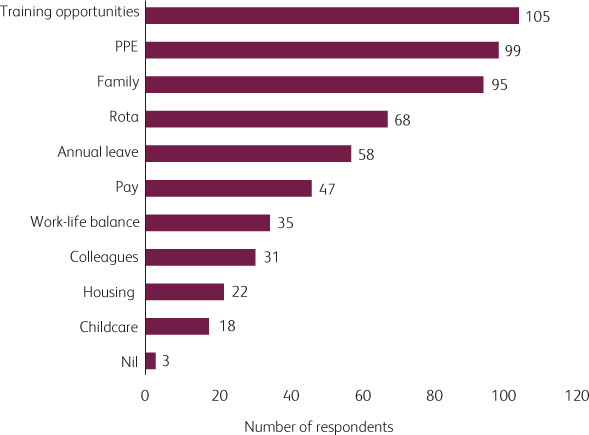

The three most common concerns were training opportunities (n=105, 61%), PPE (n=99, 57.6%), and family (n=95, 55.2%) (Fig 4). In addition to selecting from the list provided, all respondents were asked to give a free text response to ‘what could improve your wellbeing?’; key themes in the response included some of the areas already captured, such as PPE and training opportunities, but some new thoughts also emerged, including platforms to raise concerns and autonomy with rota decisions.

Fig 4.

Main concerns of redeployed doctors.

Discussion

The results of this survey describe the state of wellbeing of redeployed doctors at three major UK trusts during the first peak of the pandemic.6 We demonstrated that most doctors reported high levels of wellbeing on several measures. This is perhaps an unexpected finding, as wellbeing was not as low as might be perceived by the general public.7,8 Our results indicated that all three hospitals followed the same trend, suggesting that this may be representative of the pattern of wellbeing across many hospitals in the UK. However, the results also identify key areas of concern that need to be addressed for ongoing improvement.

Despite recent evidence that doctors have felt undervalued, with widespread dissatisfaction and junior doctor strikes about working conditions in 2016,9 our findings indicate that doctors in the current climate feel very valued by the public and their team (Fig 2). Nationwide measures including positive media coverage, the weekly ‘Clap for Carers’ and food donations to hospitals give doctors recognition for the work they are doing.10,11 It is essential that healthcare systems ensure that their staff continue to feel valued, as feeling sufficient respect and appreciation for one's work is crucial to reduce the risk of work-related stress and mental health problems in doctors.12

Two-thirds of respondents felt confident with their new role (Fig 2). In this study, the majority of redeployed doctors were ward-based where treatment is largely supportive, including oxygen therapy, antibiotics, thromboprophylaxis and intravenous fluids. These are likely to be within the skill set of all doctors, which could explain why doctors feel confident in such roles. Trusts also implemented redeployment induction training prior to redeployment, which could have helped build confidence. Furthermore, early discussion of treatment escalation plans and ceiling of care helps to remove uncertainty and gives a clear plan in the event of deterioration.13 The confidence was mirrored by 77.3% of respondents not believing they were at an increased risk of adverse events due to working beyond their level of competence.

As the pandemic unfolded we saw other countries’ healthcare systems become overrun, with doctors working long shifts with high levels of fatigue.1 It has been previously reported that UK doctors are often unable to take breaks during shifts or finish at the appropriate time.14 Our data, however, shows that the majority (65%) of doctors actually noted an increase in the duration of their breaks and 89% felt their rota gives them sufficient respite. The combination of well-staffed rotas, suspension of elective work and decreasing non-COVID-19 hospital admissions likely contributed to doctors being able to take longer breaks.

All these factors can explain why only a third of respondents reported feeling stressed in their new role, compared with previous reports of significantly higher rates of stress (up to 80%).15 Despite a large proportion not currently feeling stressed, it is important to ensure there is provision for those who currently need it and develop further strategies to actively monitor and support doctors going forward, as they are susceptible to develop post-traumatic stress or moral injury over time.3,12 To ensure long-term positive mental health, measures such as formal debriefing sessions, access to clinical psychologists, and promoting mindfulness can aid doctors over the coming months.

Feeling safe at work is essential for healthcare workers.16 Concerns about PPE have been widespread throughout the NHS and have caused significant distress amongst all healthcare professionals.17 We have shown that PHE/PHW PPE guidance has a significant impact on the wellbeing of doctors. Almost half of doctors lacked confidence in the PPE guidance, which directly impacted how safe, confident and satisfied they felt at work. Analysis of free text comments highlighted concerns that the UK is not following WHO guidance on PPE usage with inappropriate eye protection, and use of plastic aprons instead of gowns.18,19 The lack of confidence in the public health guidance may be widespread as concerns have also been raised by ophthalmology practitioners in A&Es across the NHS.20 As some doctors do not feel safe in PPE, this may have knock-on effects on patients; doctors who do not feel safe may minimise patient contact, which could indirectly lead to patient harm. It should be noted that respondents’ perception of safety in PPE does not necessarily reflect the efficacy and safety of the PPE.21 Respondents did not feel safe in PPE despite high levels of training reported. Therefore, hospitals must ensure that not only do they supply adequate PPE and training, but also share clear evidence behind PPE choices and explain reasons for deviating from WHO guidelines. Greater transparency about this, for example via Q&A sessions, may alleviate some concerns and make doctors feel safer.

Concerns about family health were common in the survey responses. Isolating away from family members to protect their health is likely to deny doctors one of their main ways to cope with stress.22 Conversely, those who are still living with their family may feel stressed about the risk they are putting their families in, particularly if living with vulnerable individuals.23 Providing accommodation for those staff that want to isolate away from families has the potential to alleviate stress. Free text analysis also indicated that many doctors were concerned about the lack of showering/changing facilities and having to wash scrubs at home. We encourage hospitals to ensure there are sufficient changing/showering facilities on site and to provide a daily set of clean scrubs to minimise transmission of COVID-19 to household members.

The top concern identified was in training opportunities/career progression (61%). With exams and training courses cancelled, and elective services postponed, many clinicians are concerned about not having enough opportunities to continue their learning and meet training requirements for upcoming appraisals.24 This is despite many training bodies acknowledging the difficulties and introducing leniencies to training programmes.25 Educational and clinical supervisors play a fundamental role in supporting trainees through their career. However, we found that a significant proportion of respondents had not had any contact with their supervisors through the pandemic period. Perhaps this relates to supervisors themselves not feeling confident in proactively offering guidance. We recommend that medical education departments within hospitals encourage supervisors to support their trainees with reassurance and guidance about career progression. However, it should also be acknowledged that many supervisors were also redeployed and will be feeling similar anxieties and stresses to their trainees.

Regular scheduled teaching sessions are fundamental for the progression of doctors through training; however, with social distancing measures in place, much of traditional classroom teaching cannot take place. A valuable solution has been to host virtual teaching sessions where doctors can either join live or revisit at a later date. These sessions have been used during redeployment to train doctors in correct PPE use, teach up-to-date management of COVID-19 patients, and help trainees stay in touch with their programme. It would be beneficial to use these virtual teaching sessions to complement traditional methods beyond the pandemic as they have a particular benefit in including less than full time trainees or those working off site, who cannot always attend in person.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. Firstly, this is a cross-sectional study providing a snapshot of wellbeing over a two-week period; we recognise that the impact of adverse working environments may not become apparent for some time and that a longitudinal study would be best at capturing this. We also recognise that despite the three hospitals having similar patterns, this may not accurately reflect the pattern at all hospitals across the UK. A reason for this is that tertiary hospitals have a larger pool of doctors to pull onto a rota and smaller district general hospitals may not have this resource. Thirdly, responses were largely from ward-based redeployed doctors and may not be representative of doctors in critical care and other healthcare professionals who are in different environments with unique challenges. Although we had a large number of responses from a broad range of grades and specialties, the response rate was relatively low (18.6%). We appreciate that the response rate could bias these findings as doctors that have more time and feel less stressed may be more likely to respond to the survey.

Conclusion

Our study provides an important insight into the wellbeing of redeployed doctors during the COVID-19 pandemic. The findings suggest that amongst the doctors surveyed, morale is higher than expected with doctors feeling well rested during and in between shifts. However, we identified the following issues as key areas of concern that require attention: training opportunities/career progression, PPE and family safety. Specific recommendations include promoting contact with supervisors, regular online teaching, transparency and a dialogue over PPE decisions, and ensuring adequate supply of scrubs with onsite changing/showering facilities. These recommendations might help to minimise the adverse effects on doctors’ wellbeing due to redeployment in the context of further peaks in COVID-19 or subsequent pandemics. Moving forward, further work is needed to understand the long-term impact of redeployment on mental health and doctors redeployed to critical care and other healthcare professionals.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all the doctors who responded to our survey over the three sites and also those involved in helping to distribute the survey.

References

- 1.Tanne JH, Hayasaki E, Zastrow M, et al. Covid-19: How doctors and healthcare systems are tackling coronavirus worldwide. BMJ 2020;368:m1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferguson NM, Laydon D, Nedjati-Gilani G, et al. Impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) to reduce COVID-19 mortality and healthcare demand. Imperial College London, 2020. Available from www.imperial.ac.uk/mrc-global-infectious-disease-analysis/covid-19/report-9-impact-of-npis-on-covid-19/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Greenberg N, Docherty M, Gnanapragasam S, Wessely S. Managing mental health challenges faced by healthcare workers during Covid-19 pandemic. BMJ 2020;368:m1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.West M, Coia D. UK-wide review of doctors and medical students wellbeing. General Medical Council; 2019. www.gmc-uk.org/about/how-we-work/corporate-strategy-plans-and-impact/supporting-a-profession-under-pressure/supporting-medical-students-and-doctors-wellbeing. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Health Education England NHS staff and learners’ mental wellbeing commission. HEE, 2019. Available from www.hee.nhs.uk/our-work/mental-wellbeing-report. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coronavirus (COVID-19) in the UK. https://coronavirus.data.gov.uk [Accessed 28 May, 2020].

- 7.Campbell D. Half of UK health workers suffering stress because of Covid-19. The Guardian, 23 April 2020. www.theguardian.com/society/2020/apr/23/half-of-uk-health-workers-suffering-stress-because-of-covid-19 [Accessed 28 May 2020].

- 8.Cuddy A. Doctors and coronavirus: ‘How can we not be afraid?’ BBC News, 17 April 2020. www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-52297156 [Accessed 28 May 2020].

- 9.Reid W. Enhancing junior doctors’ working lives – a progress report. Health Education England, 2017. https://hee.nhs.uk/sites/default/files/documents/Enhancing junior doctors working lives - a progress report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meals for the NHS. www.mealsforthenhs.com/ [Accessed 28 May 2020].

- 11.UK's ninth clap for carers. BBC News, 21 May 2020. www.bbc.co.uk/news/av/uk-52763673/coronavirus-uk-s-ninth-clap-for-carers [Accessed 28 May 2020]. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kinman G, Teoh K. What could make a difference to the mental health of UK doctors? A review of the research evidence. Society of Occupational Medicine, 2018. www.som.org.uk/sites/som.org.uk/files/What_could_make_a_difference_to_the_mental_health_of_UK_doctors_LTF_SOM.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 13.McIntosh L. Can the COVID-19 crisis strengthen our treatment escalation planning and resuscitation decision making? Age Ageing 2020;49:525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chatfield C, Rimmer A. Give us a break. BMJ 2019;364:l481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Royal College of Physicians Being a junior doctor: experiences from the front line of the NHS. RCP, 2016. Available from www.rcplondon.ac.uk/guidelines-policy/being-junior-doctor. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Health and Safety Executive Health and Safety at Work etc; Act 1974. www.hse.gov.uk/legislation/hswa.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robinson F. Self-protection: how NHS doctors are sourcing their own PPE. BMJ 2020;369:m1834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organization (WHO) Rational use of personal protective equipment for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and considerations during severe shortages. WHO, 2020. Available from www.who.int/publications/i/item/rational-use-of-personal-protective-equipment-for-coronavirus-disease-(covid-19)-and-considerations-during-severe-shortages. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Public Health England COVID-19 personal protective equipment (PPE). www.gov.uk/government/publications/wuhan-novel-coronavirus-infection-prevention-and-control/covid-19-personal-protective-equipment-ppe#ppe-guidance-by-healthcare-contex [Accessed 28 May 2020].

- 20.Minocha A, Sim SY, Than J, Vakros G. Survey of ophthalmology practitioners in A&E on current COVID-19 guidance at three major UK eye hospitals. Eye (Lond) 2020;4:1243–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hunter E, Price DA, Murphy E, et al. First experience of COVID-19 screening of health-care workers in England. Lancet 2020;395:e77–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Markwell AL, Wainer Z. The health and wellbeing of junior doctors: Insights from a national survey. Med J Aust 2009;191:441–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adams JG, Walls RM. Supporting the health care workforce during the COVID-19 global epidemic. JAMA 2020;323:1439–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Health Education England Supporting the COVID-19 response: Guidance regarding medical education and training. HEE, 2020. www.gmc-uk.org/news/news-archive/guidance-regarding-medical-education-and-training-supporting-the-covid-19-response. [Google Scholar]

- 25.General Medical Council Annual review of competency progression (ARCP). GMC, 2018. www.gmc-uk.org/education/reports-and-reviews/progression-reports/annual-review-of-competency-progression. [Google Scholar]