Abstract

In attempts to reduce the spread of COVID-19 among high-risk inflammatory bowel disease patients, many gastroenterology practices have recently gone ‘virtual’, using telemedicine technologies to care for their patients. In efforts to support this transition and improve approachability, social media platforms have been used to deliver telemedicine services with significant success. However, the patient perspective on this use of social media has largely been ignored. This study provides a baseline patient perspective on social media usage to help inform clinicians on which methods of telemedicine delivery will be best suited to their patient populations.

KEYWORDS: Social media, telemedicine, patient perspective, COVID-19, inflammatory bowel disease

Introduction

Telemedicine is a broad term that encompasses the delivery of healthcare services through communication technologies.1 In attempts to reduce the spread of COVID-19 among high-risk inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients, many gastroenterology practices have recently gone ‘virtual’, using telemedicine technologies to care for their patients. In efforts to make the transition to telemedicine easier and more approachable, social media platforms have been used to deliver telemedicine services with significant success.2 Due to the almost universal prevalence of social media in the developed world, it provides a convenient means of healthcare delivery that requires minimal patient training.3

However, despite being informed by evidence-based medicine, the patient perspective on this transition has largely been ignored. This may lead to negative consequences, such as reduced patient compliance and satisfaction, ultimately producing worse clinical outcomes.4,5 Therefore, it is imperative that this novel form of healthcare delivery is aligned with patient wishes as well as being accessible and intuitive to use. This study provides a baseline patient perspective on social media usage, the types of social media telemedicine interactions desired, and concerns over using social media for telemedicine. These data were collected before COVID-19 was declared a pandemic by the WHO and could inform clinicians on which methods of telemedicine delivery may be best suited to their patient populations, thus allowing the creation of a novel digital healthcare delivery system that is effective and welcomed during the pandemic and in the longer term.

Methods

A voluntary, anonymous questionnaire was offered to patients with IBD attending specialist inflammatory bowel disease outpatient clinics at St George's Hospital, London from November 2019 to February 2020. The questionnaire consisted of questions with multiple choice answers as well as ‘Other’ free text answers where patients could express unique responses. This method enabled collection of high-yield quantitative and qualitative data, ensuring the full patient perspective was captured. The questionnaire collected data on current social media usage and perspectives on the use of social media as a delivery platform for telemedicine. Convenience sampling was used, and informed consent was gained from all participants. Descriptive statistics were used to present the results.

Results

112 patients completed the questionnaire. 44.6% were male, mean age was 47 years and average time since diagnosis was 12 years. 50 patients (44.6%) had Crohn's disease, 46 (41.1%) had ulcerative colitis, and 16 patients (14.3%) were unsure of their IBD subtype.

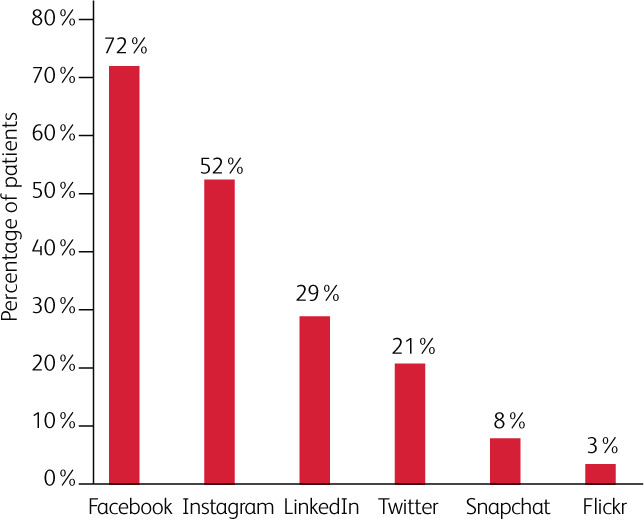

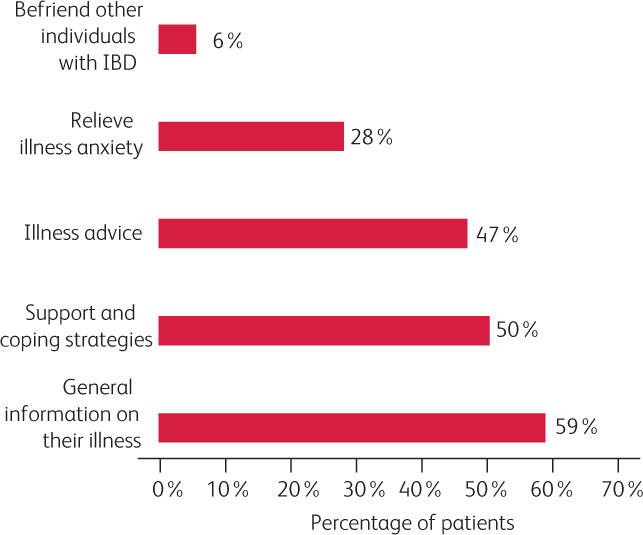

110 patients (98.2%) had access to a device that could access the internet, with 74 patients (66.7%) able to access the internet anywhere via smartphone. 93 patients (83.0%) used social media. Facebook and Instagram were the most popular applications, with 81 (72.3%) and 58 (51.7%) users, respectively (Fig 1). However, only 32 (28.6%) patients used social media in connection with their IBD. Of these, 19 patients (59.4%) used it for general information about their condition, 16 (50%) used it for support and coping strategies, 15 (46.9%) used it to get illness advice, 9 (28.1%) used it to relieve illness anxiety, and two (6.3%) used it to befriend other individuals with IBD (Fig 2).

Fig 1.

Social media use in inflammatory bowel disease patients.

Fig 2.

Reasons inflammatory bowel disease patients currently use social media in their disease management.

81 patients (72.3%) stated that they would like telemedicine delivered over social media, allowing healthcare professionals to interact with them. Half of the patients (49.1%) thought that direct one-to-one contact with a gastroenterologist via social media would be desirable, and 46 patients (41.1%) wanted a gastroenterologist to answer patient questions in a dedicated social media group (Table 1).

Table 1.

Types of interactions patients would like with their physician over social media

| What extent would you like a physician to be able to interact with you via social media? | Number of patients who responded ‘yes’ (percentage) |

|---|---|

| Be able to interact on a one-to-one basis if you request it | 55 (49.1%) |

| Be able to read and answer patient questions in dedicated social media groups | 46 (41.1%) |

| Be able to give information to specific social media groups | 37 (33.0%) |

| Be able to join specific groups and interact with any group member | 35 (31.3%) |

| Be able to interact and view your information on social media sites where other members could do the same | 35 (31.3%) |

| Have no interaction at all | 31 (27.7%) |

Only a small number of patients had concerns regarding the use of telemedicine delivered via social media. The most commonly reported concerns were that their medical condition would not be effectively treated (9.8%), or that the quality of care provided would be inadequate (8.9%) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Patient reasons against using social media delivered telemedicine

| Reasons why you would not like social media delivered telemedicine | Number of patients who responded ‘yes’ (percentage) |

|---|---|

| Don't believe your medical condition will be effectively treated | 11 (9.8%) |

| Don't believe quality of care provided will be adequate | 10 (8.9%) |

| Don't believe personal patient data will be adequately protected | 10 (8.9%) |

| Not confident enough with your ability to use telemedicine software | 4 (3.6%) |

Discussion

The majority of patients with IBD are active on social media and nearly one third already use it for their IBD. Most would welcome the integration of social-media-delivered telemedicine into the management of their IBD and some platforms have already begun offering these services. In addition to allowing communication between the physician and patient, social media is being used for a variety of health-related activities. One study by Pérez-Pérez et al revealed that IBD patients use Twitter to connect with each other to discuss symptoms and treatments, as well as seek to guidance from organisations such as Crohn's and Colitis UK.6 Another study described how the online IBD community uses social media to advocate against the stigma faced by IBD patients and to raise disease awareness.7 These studies suggest that IBD patients have already taken the initial steps towards integrating their health with social media platforms. As the COVID-19 pandemic continues, further steps towards integration may occur as more gastroenterologists and patients begin using telemedicine services. This transition could provide many benefits, including increasing treatment efficiency, allowing for more timely communication and reducing the cost of healthcare delivery. This was emphasised in a systematic review by Patel et al highlighting the many positive clinical outcomes of using social media in chronic disease care.2

Despite these benefits, patients and physicians alike should be wary of relying solely upon social media platforms for medical information. Steinberg et al revealed that over 70% of YouTube videos providing information on prostate cancer were of ‘poor’ or only ‘fair’ quality based on their informational content, which may negatively impact the viewers due to the misinformation disseminated.8 Another study discovered significant discordance between medical information offered by Wikipedia articles and by peer-reviewed sources.9 This is worrisome as both platforms are highly viewed, and the consequences of these poorly regulated platforms may tarnish the reputation of more controlled future forms of social-media-delivered healthcare. In our study, the most common use of social media for disease management was to obtain general information on their IBD condition (59.4%). As a result, these patients may visit their gastroenterologist less frequently if their questions and concerns are addressed via social media platforms. This would reduce the cost of IBD management by decreasing the number of appointments and freeing up clinic space, allowing physicians to increase their patient loads. Furthermore, the majority of the patients surveyed use Facebook (72.3%) or Instagram (51.7%), making these the ideal applications to deliver telemedicine as more patients would be familiar with them, allowing for a smoother transition to a virtual environment.

Looking to the future, we asked patients what type of interactions they desire with their gastroenterologist via social-media-delivered telemedicine. Almost half of the patients (49.1%) expressed interest in direct, one-to-one consultations with a gastroenterologist via social media. This form of telemedicine is the most similar to traditional in-person clinic appointments – perhaps highlighting the patients’ desire for familiarity. The use of established social media platforms offers greater familiarity than other proprietary telemedicine software, and as a result may be more welcomed by the patients. Patients also displayed inclinations towards less resource-intensive telemedicine interactions. Many patients (41.1%) stated they would be happy with a gastroenterologist answering specific patient questions in social media groups dedicated to their disease. These questions and answers would be public (meaning all members of the social media group would be able to view them) and allow other IBD patients to benefit from viewing common concerns from other patients. Interestingly, fewer patients (33.0%) were happy with the idea of using social-media-delivered telemedicine to disseminate generalised information on disease management written by their physicians. This emphasises the fact that patients desire interactive communication with their physician, though this must be balanced with the cost-effectiveness of more generalised patient care. Furthermore, it will be important to consider patient and clinician expectations of the delivery of virtual healthcare. Patients may expect (or hope) that their conditions will be completely managed by telemedicine services. This may clash with the clinician's understanding of the limitations of virtual consultations, including the lack of physical examinations and ability to perform procedures. This can be mitigated through triage to ensure the patients have conditions suitable for management via telemedicine.

Although social media platforms benefit from increased patient familiarity and accessibility compared to other telemedicine delivery platforms, they come with some unique challenges. Due to the link between social media platforms and the users’ private lives, extra precautions will be required to ensure that patients have control over how much personal information their physicians can access. Some healthcare professionals may argue that access to a patient's personal life allows better patient monitoring, as well as more tailored disease management. However, the majority of patients (68.7%) stated that they did not want physicians to be able to view their personal information on social media sites, even if it was related to their care. Furthermore, 8.9% of patients did not believe that their patient data would be properly protected using social-media-delivered telemedicine. These sentiments were reflected in a cross-sectional survey performed in the Crohn's and Colitis internet-based cohort, where the most common concerns about using social media in disease management were patient privacy and confidentiality.10 Therefore, NHS service managers will need to consider the ethico-legal implications of relying on current social media platforms to prevent unwanted sharing of patient information – with the public as well as their physician. While appropriate security technology certainly exists, it will be important to consider how and where it is deployed within the social media platforms to ensure patient privacy.11

The most common patient concerns were that social-media-delivered telemedicine would be ineffective for their disease management and that the quality of care provided would be inadequate. Similar concerns regarding whether video consultations can provide adequate information for diagnosis and management of medical conditions have been highlighted in the past.3 However, despite these concerns, many studies have demonstrated the efficacy of telemedicine in successfully managing chronic conditions.2,12 One true weakness of telemedicine is its ineffectiveness in treating acute conditions which require immediate, lifesaving interventions. To this end, there will always be a need for in-person medical care. However, social-media-delivered telemedicine can provide a safe and effective adjunct and/or replacement to traditional clinics during the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as further into the future.

Based on our audit, we established more telephone clinics and expanded our advice line service to include more email communication in addition to telephone support. Since March 2020, all consultations have been carried out via telephone, with dedicated ‘hot’ clinics for any emergency face-to-face consultations. As the COVID-19 pandemic continues, longer-term plans are being made for ongoing telemedicine clinics.

Limitations

Single-centre data collection is a limitation as patient demographics, as well as technology access and attitudes, will inevitably differ across the UK. In addition, the generalisability of the results may be limited by the time since diagnosis (mean 12 years) and age of the respondents (mean 47 years old). Most patients in this age group did not grow up with the social media platforms currently available and therefore may express different perspectives on the use of social-media-delivered telemedicine than a newly diagnosed IBD patient in their twenties. Interestingly, a study by Szeto et al found that adolescents with IBD were less likely than adults with IBD to use social media for health-related activities, despite being intensely familiar with the platforms.13 These differences in patient preference should be accounted for when creating novel policies for digital healthcare. Convenience sampling was used, which is prone to sampling bias. Finally, patients may interpret sections of the questionnaire differently, may not answer truthfully, and due to the multiple-choice nature of the questions may not be able to fully express their opinions. However, this risk was partially mitigated by allowing free-text responses in addition to the multiple-choice answers.

Conclusion

Overall, the patient perspective on the use of social-media-delivered telemedicine in IBD management is positive, and a significant proportion of patients have already begun utilising these platforms in their disease management. Looking to the future, patients desire individualised care that mirrors their traditional in-person care, albeit in a virtual environment, and the use of technology to allow more fluid communication between patients and their physicians. Precautions will need to be taken to ensure patient privacy is maintained and that their conditions are being suitably managed virtually. Further research is required to investigate the optimal method to integrate social-media-delivered telemedicine into the delivery of IBD services. Ultimately, these patient preferences on the delivery of social media telemedicine will inform policy on how to best implement the safe and effective digital healthcare that our patients desire and need during these unprecedented times.

References

- 1.World Health Organization A health telematics policy in support of WHO's Health-For-All strategy for global health development: report of the WHO group consultation on health telematics, 11–16 December, Geneva. WHO, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patel R, Chang T, Greysen SR, et al. Social media use in chronic disease: a systematic review and novel taxonomy. Am J Med 2015;128:1335–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gogia SB, Maeder A, Mars M, et al. Unintended consequences of tele health and their possible solutions: contribution of the IMIA working group on telehealth. Yearb Med Inform 2016;1:41–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jimmy B, Jose J. Patient medication adherence: Measures in daily practice. Oman Med J 2011;26:155–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.House of Commons Health Committee Patient and public involvement in the NHS. Third report of session 2006–07. London: Stationery Office, 2007. https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm200607/cmselect/cmhealth/278/278i.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pérez-Pérez M, Pérez-Rodrí-guez G, Fdez-Riverola F, et al. Using twitter to understand the human bowel disease community: exploratory analysis of key topics. J Med Internet Res 2019;21:e12610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frohlich D. The social construction of inflammatory bowel disease using social media technologies. Health Commun 2016;31:1412–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steinberg PL, Wason S, Stern JM, et al. YouTube as a source of prostate cancer information. Urol J 2010;75:619–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hasty RT, Garbalosa RC, Barbato VA, et al. Wikipedia vs. peer-reviewed medical literature for information about the 10 most costly medical conditions. J Am Osteopath Assoc 2014;114:368–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reich J, Guo L, Groshek J, et al. Social media use and preferences in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2019;25:587–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hall J, McGraw D. For telehealth to succeed, privacy and security risks must be identified and addressed. Health Aff 2014:33:216–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oliveira TC, Branquinho MJ, Gonçalves L. State of the art in telemedicine – concepts, management, monitoring and evaluation of the telemedicine programme in Alentejo (Portugal). Stud Health Technol Inform 2012;179:29–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Szeto W, van der Bent A, Petty C, et al. Use of social media for health-related tasks by adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease: a step in the pathway of transition. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2018;24:1114–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]