“The answer my friend is blowing in the wind. The answer is blowing in the wind.”

(Bob Dylan, 1963)

1. Introduction

1.1. How many ways are there to rehabilitate tourism?

The Covid-19 pandemic has had a powerful and varied impact on the tourism industry. This research note, composed in July 2020, half a year after the outbreak of the pandemic, aims: a) to outline national Covid-19 exit strategies for tourism; b) to compare, analyze, and synthesize the current strategies; and c) to assess whether the strategies proposed by the UNWTO (UN World Tourism Organization) have been adopted by different countries, as no study produced thus far has considered both the strategies and their adoption. This note's broader goal is to better understand the pandemic's impact not only on the tourism industry but on policy implementation on the global level.

2. Literature review

2.1. Covid-19 and the tourism industry

The Covid-19 pandemic has negatively impacted the many different sectors of tourism (Gössling et al., 2020; Hall et al., 2020), ultimately causing the industry to shut down for months. Though various efforts have been made since June 2020 to reopen the industry, most sectors continue to struggle and the UNWTO (2020a) has acknowledged tourism as one of the hardest hit industries (Dolnicar & Zare, 2020; Gössling et al., 2020).

Crises are regular occurrences in tourism (Dolnicar & Zare, 2020; Gössling et al., 2020). Many destinations are affected by natural and human-made crises and, over the years, have developed tactics and strategies of resilience and mitigation (Ritchie & Jiang, 2019). The crisis stemming from the Covid-19 pandemic, however, has been different and unique in many ways. First, the decline in travel, hospitality and tourism has been world-wide (UNWTO, 2020b). Second, the economic collapse has been more dramatic. Third, the ongoing crisis has the potential to cause fundamental modifications in many tourism segments (Dolnicar & Zare, 2020). And fourth, the end of the crisis is nowhere in sight. Only recently, Yang et al. (2020) developed a ‘dynamic stochastic general equilibrium’ (DSGE) model to understand the effect of the pandemic on global tourism. The model's application to Covid-19 reflects a decline in tourism demand in response to rising health risk.

A review of the current literature on Covid-19's impact on the tourism industry reveals that the bulk of the texts that have been published thus far can be described as opinion papers or research notes. For example, the special issue of Tourism Geographies on the subject contains more than 30 works on the ways in which the pandemic events of 2020 could contribute to a transformation of the tourism industry. Additional works have also been published in other journals from the field of tourism (such as Annals of Tourism Research, Journal of Travel Research, and Journal of Sustainable Tourism) and other fields (such as economics). Only a few papers have been written using an empirical method (such as Yang et al., 2020; Gössling et al., 2020), and none have discussed an evidence-based policy for tourism in light of the Covid-19 crisis.

2.2. Evidence-based policy and national tourism policy

Public decision makers and the social sciences have not had close relationships as policy decisions are derived primarily from politics and governments rather than from facts, research, and empirical models. Moreover, knowledge is understood and applied in various ways by different decision makers looking through their own lenses (Head, 2007).

Another challenge to the idea of ‘evidence-based policy’ is the difficulty of combining new-found networks, research-based data, models, inter-displinary research and new partnerships to the conventional forms of policy development. As a result, national policies are often affected by political and other issues (Agranoff & McGuire, 2003; Osborne & Brown, 2005).

First published in April 2020, the UNWTO's policy for supporting jobs and economies through travel and tourism includes a call for action to mitigate the socio-economic impact of Covid-19 and to accelerate recovery (UNWTO, 2020c). This research note analyzes the adoption of this policy in national recovery plans and examines its limitations as an evidence-based policy.

3. Methods

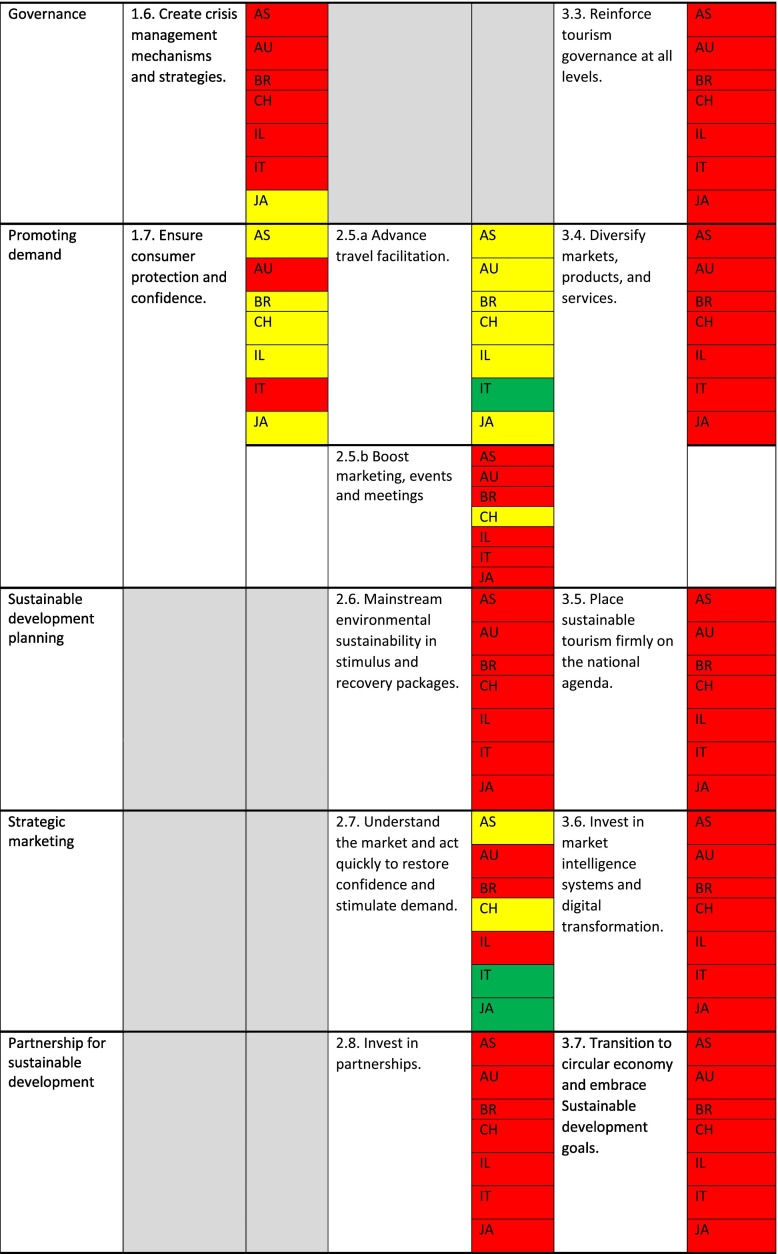

As a benchmark for our analysis of the national plans, conducted at the beginning of July 2020, we used the strategies and tactics recommended by the UNWTO.1 Table 2 presents the three main strategies and 23 criteria for dealing with the crisis in the tourism sector. The three recommended strategies are as follows: 1) crisis management and impact mitigation; 2) stimulus and recovery acceleration; and 3) preparing for tomorrow.

Table 2.

Adoption of the UNWTO's recovery strategies, by national recovery plan.

The seven countries surveyed were selected based on geographic dispersion, stages of the pandemic, sizes and shapes, past historical crises, and border status (open or closed) [see Table 1 ]. Unless otherwise indicated, the information below is based primarily on each country's reporting to the UNWTO regarding its national tourism policy.2

Table 1.

Countries and characteristics.

| Australia | Austria | Brazil | China | Israel | Italy | Japan | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geographic distribution | Pacific | Europe | America (South) | Asia | Middle East | Europe | Asia |

| Size of population | 25 M | 9 M | 209.5 M | 1439 M | 8.6 M | 60 M | 126 M |

| Beginning of national preventive steps | 03/20 | 03/20 | 03/20 | 01/20 | 03/20 | 02/20 | 02/20 |

| Number of confirmed cases/death (July 2020)a | 9059/106 | 18,500/700 | 2,000,000/78,000 | 84,900/4600 | 33,500/340 | 242,000/34,900 | 20,400/980 |

| Tourism as % of the GDPb, c, d (direct contribution) | 3.1 (2017) | 6.47 (2018) | 2.44 (2019) | 3.3 (2017) | 2.5 (2017) | 5.5 (2017) | 1.96 (2017) |

Each country's national recovery plan was analysed in accordance with UNWTO strategies and tactics, with specification regarding whether the criterion was met by the plan (using a yes/no/partially categorical ranking). The analysis was based on evaluation by the three authors, each of whom analysed both the UNWTO recommendations and each of the seven countries' current national tourism strategies and tactics. A comparison among the assessments of the three authors revealed whether each recommendation was implemented fully, partially, or not all. If not a definite “yes” or “no,” a criterion was classified as “partially” implemented.

4. Results

The results presented in Table 2 reflect significant disparity in the extent to which the three strategies were adopted. The UNWTO's first strategy of “Managing the Crisis and Mitigating the Impact” was embraced partially. Italy and Brazil fully adopted two tactics out of seven, and the other countries adopted only one (Japan and Australia) or none at all (Israel, China, Austria). The most widely adopted tactics were: 1.1 – “Incentivize job retention, sustain the self-employed, and protect the most vulnerable groups”; and 1.2 – “Support the liquidity of companies.” Each of these tactics were adopted fully by two countries and partially by four additional countries.

The second suggested strategy – “providing stimulus and accelerating recovery” – was also adopted by different countries to only a minor extent. Italy adopted four tactics out of nine, Japan and Austria each adopted one, and the remaining four countries fully adopted none. Accordingly, only tactics 2.2 (“review taxes, charges, and regulations impacting travel and tourism”) and 2.5.a (“advance travel facilitation”) were adopted fully or partially by at least six of the seven countries.

The UNWTO's third strategy of “Preparing for Tomorrow” was hardly implemented, as six of the seven countries considered adopted none of its recommendations, and Italy adopted only one of the seven [3.2]: “Invest in human capital and talent development by retaining employment.” Other environmental considerations [3.5; 3.7] were not adopted at all.

Of all the countries surveyed, Italy adopted the most recommendations, with seven of the 23 fully adopted and one partially adapted. Japan and Brazil adopted two fully (in addition to five partially), Australia and Austria each fully adopted one tactic (with Australia and Austria partially adopting eight and five, respectively), and the remaining two countries – Japan and Israel – have not fully implemented any of the policies recommended by the UNWTO.

To summarize, of the 161 possible recommendations (seven countries and 23 tactics), only 13 (8%) were fully implemented and only 37 were partially implemented (23. %). With regard to the third strategy, only one tactic was fully implemented by one country. Unfortunately, issues of sustainable development [3.5; 3.7], human capital [1.5; 2.4; 3.2], and governance [1.6; 3.3] were hardly addressed at all.

5. Discussion

This research note sought to address various ways of rehabilitating the tourism sector through an examination of different national tourism plans. With the decline of Covid-19 in some regions, tourism slowly began picking up and hotels, tourist attractions, restaurants, and transportation started to resume activity. However, a second wave in some regions has caused tourism activity to decline once again. This note is an initial attempt to analyze national policies, as they offer an evidence-based snapshot of a select sample of countries six months into the pandemic. A broader study including more countries, to be implemented after the recurring waves, has been planned in an effort to better understand national strategies. Continuation of this analysis, by gathering further data over the years to trace policy evolutions, will contribute to the current research on tourism development during and after the pandemic era.

In trying to achieve this note's broader goal of better understanding the pandemic's impact not only on the tourism industry but on policy implementation on the global level, we can forecast a shift from the “top-down” tactics suggested by major bodies and organizations to a strategy of “bottom-up” tactics. Local forces (countries, regions, cities) with specific tactics aimed at handling the crisis can be expected to assume control of the current crisis. This change will probably take place not only in the tourism arena but rather also in many different and diverse realms such as health, economics, education, and others.

That being the case, with regard to the question posed at the outset of this article (“how many ways are there to rehabilitate tourism”) and in the immortal words of Bob Dylan, we must conclude that at this stage of the game, without a doubt, “the answer…is blowing in the wind”.

6. Conclusions

First, it should be noted that the sampled countries, though different in many ways, have all yet to formalize comprehensive exit strategies and rehabilitation plans for their tourism sectors, and are, for the moment, implementing various tactical measures to contend with the current crisis as part of their national tourism policies. The general tendency in these countries appears to be to implement short-term local solutions, particularly as no country can unilaterally decide on inbound and outbound tourism.

Second, no single policy or strategy fits all, despite the UNTWO's recommendations, and each country has therefore adopted different dynamic plans. On the one hand, this is understandable, as each country has been impacted differently by the pandemic and has its own unique characteristics, as reflected in local politics, tourism networks and actors, society and culture (Head, 2007). On the other hand, without an international commitment to sustainable tourism, this sector will not become more resilient and better prepared for future crises (Hall et al., 2020).

Third, the UNWTO's strategy of “Preparing for Tomorrow” has not been adopted, as countries have tended to focus on local and short-term tactics for restarting tourism instead of on the long-term sustainable agenda (Gössling et al., 2020; Hall et al., 2020). Hall et al. (2020, p.1) have argued that “…. the selective nature of the effects of Covid-19 and the measures to contain it may lead to reorientation of tourism in some cases, but in others will contribute to policies reflecting the selfish nationalism of some countries,” reflecting the weakness of the UNWTO recommendations. As noted by Head (2007), policy decisions are derived not only from empirical models, facts, and research, but rather from political views, culture, and judgement.

Fourth, information within the world of tourism is used in different ways by different actors and through various “lenses” (Head, 2007). As a result, there is more than one type of related ‘evidence’ (such as “political know-how”, empirical research, and professional practice) that can make a significant contribution to policy development, and the UNWTO's recommendations were not perceived as “evidence-based policy” and were not implemented by most countries. The situation faced by the UN's World Health Organization has been even more dramatic, with its data and recommendations being rejected as inadequate, non-transparent, and unbalanced.3 Also relevant in this context is Agranoff and McGuire's (2003) argument regarding the difficulties of addressing modern networks using traditional forms of systematic knowledge.

Consequently, the UNWTO needs to recognize that major differences exist in the tourism industries of its member states and that there is no single solution for all. Hale et al. (2020, p. 6) has summarized the challenge of heterogeneity in their Covid-19 tracker project (OxCGRT) as follows: “Like any policy intervention, their effect is likely to be highly contingent on local political and social contexts. These issues create substantial measurement difficulties when seeking to compare national responses in a systematic way.” A shared vision with a broad spectrum of tactics that could be achieved in diverse ways would probably be more suitable for the current time. Another conclusion is that local voices currently seem to possess better “know-how” regarding how to deal with the tourism industry of each specific country, region, and even city. For this reason, most member states are going it alone, without employing UNWTO strategies and recommendations.

The current UNWTO tourism recovery strategies are not evidence-based policies and provide only partial solutions to an international problem without an agreed-upon international base of data. Nonetheless, increased mutual understanding, shared objectives, and a new kind of evidence-based policy are critical needs of the tourism industry in the Covid-19 era.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgement

This research was conducted through The National Knowledge and Research Center for Emergency Readiness and funded by Israel Ministry of Science and Technology, Israel.

Biographies

Noga Collins-Kreiner is a Professor (PhD), in the Department of Geography and Environmental Studies at the University of Haifa, Israel. Her main research interests are: Pilgrimage, Religious Tourism, Heritage Tourism, Hiking, and Tourism Development and Management.

Yael Ram is a Senior Lecturer (PhD) in the Department of Tourism Studies at the Ashkelon Academic College, Israel. Her research interests focus on person–environment relations, sustainable consumer behaviours and low carbon mobilities.

Associate editor: Yang Yang

Footnotes

References

- Agranoff R., McGuire M. Georgetown University Press; 2003. Collaborative public management: New strategies for local governments. [Google Scholar]

- Dolnicar S., Zare S. COVID19 and Airbnb: Disrupting the disruptor. Annals of Tourism Research. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2020.102961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gössling S., Scott D., Hall C.M. Pandemics, tourism, and global change: A rapid assessment of Covid-19. Journal of Sustainable Tourism. 2020 doi: 10.1080/09669582.2020.1758708. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hale T., Webster S., Petherick A., Phillips T., Kira B. Blavatnik School of Government; 2020. Oxford covid-19 government response tracker.https://www.bsg.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2020-05/BSG-WP-2020-032-v6.0.pdf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall C.M., Scott D., Gössling S. Pandemics, transformations, and tourism: Be careful what you wish for. Tourism Geographies. 2020 doi: 10.1080/14616688.2020.1759. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Head B.W. Three lenses of evidence-based policy. The Australian Journal of Public Administration. 2007;67(1):1–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8500. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne S.P., Brown K. Routledge; 2005. Managing change and innovation in public service organizations. [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie B.W., Jiang Y. A review of research on tourism risk, crisis, and disaster management. Annals of Tourism Research. 2019;79 doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2019.102812. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- UNWTO . 2020. Impact assessment of the Covid-19 outbreak on international tourism.https://www.unwto.org/impact-assessment-of-the-covid-19-outbreak-oninternational-tourism [Google Scholar]

- UNWTO . 2020. International tourist arrivals could fall by 20–30% in 2020.https://www.unwto.org/news/international-tourism-arrivals-could-fall-in-2020 [Google Scholar]

- UNWTO . 2020. Supporting jobs and economies through travel & tourism: A call for action to mitigate the socio-economic impact of Covid-19 and accelerate recovery. (accessed July 7, 2020) [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y., Zang H., Chen X. Coronavirus pandemic and tourism: Dynamic stochastic general equilibrium modeling of infectious disease outbreak. Annals of Tourism Research. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2020.102913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]