Supplemental Digital Content is available in the text.

Background:

Toxic shock syndrome (TSS) is an underrecognized but highly fatal cause of septic shock in postoperative patients. Although it may present with no overt source of infection, its course is devastating and rapidly progressive. Surgeon awareness is needed to recognize and treat this condition appropriately. In this paper, we aim to describe a case of postoperative TSS, present a systematic review of the literature, and provide an overview of the disease for the surgeon.

Methods:

A systematic review of the literature between 1978 and 2018 was performed according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines using the keywords “toxic shock syndrome” and “surgery.” Variables of interest were collected in each report.

Results:

A total of 298 reports were screened, and 67 reports describing 96 individual patients met inclusion criteria. Six reports described a streptococcal cause, although the vast majority attributed TSS to Staphylococcus aureus (SA). The mortality in our review was 9.4%, although 24% of patients suffered some manner of permanent complication. TSS presented at a median of 4 days postoperatively, with most cases occurring within 10 days.

Conclusions:

Surgeons must maintain a high index of suspicion for postoperative TSS. Our review demonstrates that TSS should not be excluded despite young patient age, patient health, or relative simplicity of a procedure. Symptoms such as fever, rash, pain out of proportion to examination, and diarrhea or emesis should raise concern for TSS and prompt exploration and cultures even of benign-appearing postoperative wounds.

INTRODUCTION

Septic shock is a serious condition, carrying a mortality of up to 50% and representing the second leading cause of deaths in noncardiac intensive care units (ICUs).1,2 First reported in 1978, toxic shock syndrome (TSS) is a particularly insidious subtype of septic shock.3 Although less well-known, it carries a significant mortality rate, higher even than meningococcal septicemia.4 Unlike classic presentations of sepsis, patients with TSS often lack evidence of an overt infection or even bacteremia. Nonetheless, they may rapidly progress to shock and multiorgan failure. The systemic inflammatory response is predominantly caused by exotoxins and enterotoxins that are produced by pathologic strains of bacteria—most commonly SA and beta-hemolytic group A Streptococcus (GAS) species.4

Although there is some awareness of TSS among health-care professionals and even the general public, early reports have led to an association between TSS and the prolonged use of tampons. Changes in tampon manufacturing led to a decrease in the incidence of menstrual TSS, with menstrual TSS accounting for only 55% of TSS in women in the United States by 1986.5 Indeed, 1 French surveillance study in 2008 demonstrated that 65% of staphylococcal TSS cases were nonmenstrual and that these carried a mortality of 22% compared to 0% in menstrual TSS.6

As the epidemiology of TSS has evolved over the recent decades, the relative rate of TSS has risen in postoperative patients.7 Given the paucity of typical signs of sepsis in TSS, its rapid progression, and the high mortality conveyed by this condition, the aim of this paper is to provide an overview of this syndrome as it may present in patients after surgery. We present a case describing our experience with postoperative TSS and a systematic review of the literature.

Patient Presentation

A 57-year-old man with a history of hypertension and daily tobacco use first presented to our institution with a basal cell carcinoma of the frontal and parietal scalp (Fig. 1A). He underwent en bloc excision resulting in a significant calvarial defect requiring titanium mesh cranioplasty and anterolateral thigh (ALT) fasciocutaneous, perforator flap from the right thigh for soft tissue coverage (Fig. 1B and C). The ALT donor site could not be completely closed, so split-thickness skin grafts from the right medial thigh were used. The patient received 3 perioperative doses of cefazolin over the course of 24 hours. The donor site was dressed with Xeroform, Kerlix gauze, and a compressive wrap. The gauze and wrap was removed on postoperative day 5; the Xeroform was left in place over the split-thickness skin graft donor site until the skin reepithelialized. His postoperative course was unremarkable and on postoperative day 7 he was discharged.

Fig. 1.

Initial patient presentation and surgery. A, Preoperative image demonstrating fungating scalp mass. B, Defect following excision of mass and titanium mesh cranioplasty. C, Postoperative image demonstrating ALT flap coverage of defect with a single drain in place.

On postoperative day 9, the patient presented to the emergency department with a 24-hour history of fevers, severe pain on the right lower extremity, and emesis. His mental status was at baseline. On physical examination, he was found to have a fever of 103°F and mean arterial pressures less than 65 mm Hg. Physical examination of the patient’s ALT flap was unremarkable. The right thigh donor site demonstrated mild erythema and edema around the wound margins, but was without any purulent drainage or tissue necrosis. Hypotension was unresponsive to a total of 6 L of intravenous (IV) fluid. Blood cultures were drawn, and he was started on broad-spectrum IV antibiotics. He required emergent intubation in the emergency department and was admitted to the ICU where he required the maximum dose of vasopressors. His lactate peaked at 4.6 mmol/L; his white blood cell count (WBC) at the end of the day of his admission was 32 × 103 cells/μL (up from 10 × 103 cells/μL that same morning). Imaging demonstrated some soft tissue swelling in the right thigh but no fluid collections or evidence of gas along fascial planes. A bedside incision and drainage of his right thigh donor site revealed only viable muscle and subcutaneous tissue without evidence of purulent drainage.

Over the following days, the patient suffered 1 pulseless electrical activity arrest and significant multiorgan dysfunction: his WBC peaked at 51 × 103 cells/μL, urine production fell to 15 mL/h with rising creatinine (0.5 to 4.4 mg/dL), and creatine phosphokinase levels rose to 1,890 U/L. However, with supportive care and antimicrobial treatment, he gradually improved, and on the third day after admission was successfully weaned off vasopressors and extubated. Withdrawal of vasopressors resulted in return of the free flap Doppler signal and right foot (lost due to pressor requirements); however, the left foot remained ischemic.

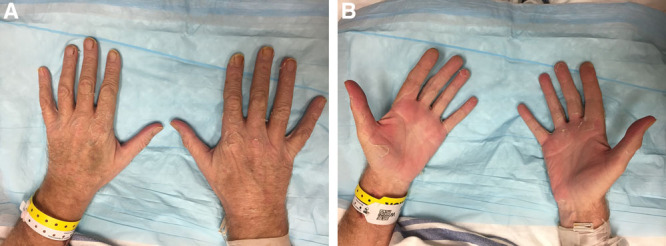

Blood cultures were persistently negative for growth of organisms. The patient experienced desquamation of the palms of his hands (Fig. 2) and the soles of his feet on the 19th day after admission. He underwent a left below-knee amputation on the 25th day after admission. He was discharged 34 days after admission and was in good health at last follow-up.

Fig. 2.

Desquamation occurred approximately 19 days after surgery. A and B demonstrate the patient’s hands with panel B showing desquamation of the palms. The patient had removed some of the desquamated skin on his palms when the pictures were taken.

METHODS

We performed a systematic review of the literature to assess reports of TSS after surgery. We searched the PubMed databased using the phrase “toxic shock syndrome” (title) and “surgery” (all fields). We also performed a manual search using the phrase “toxic shock syndrome after surgery.” The criteria for “surgery” that were applied included any procedure that disrupted the epithelial/mucosal barrier by way of intentional instrumentation. Cases of TSS that occurred more than 60 days after surgery were excluded. Non-English language articles and commentaries were excluded. Cases of TSS due to the sole use of nasal packing, facial peels, or burns were excluded. Descriptive statistics and figures were generated using GraphPad Prism version 7.00 for Mac OS X, GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA.

RESULTS

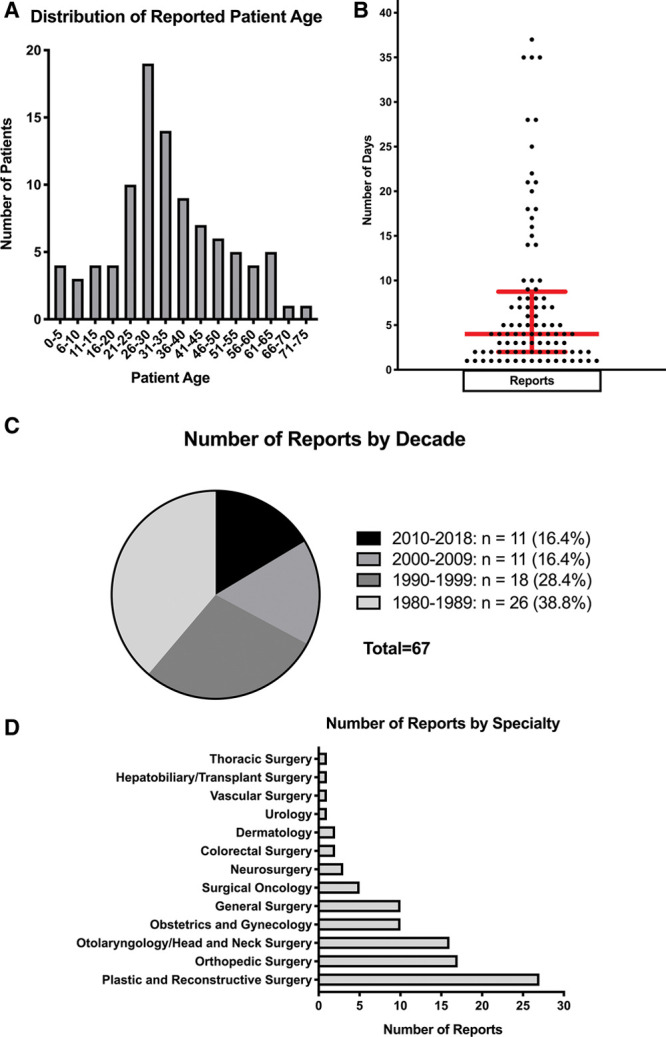

Two hundred ninety-four titles were identified through PubMed. Four additional unique titles were identified through a manual search. All 298 titles were screened, and 222 titles were excluded based on predetermined criteria. The remaining 76 articles were reviewed in-depth. (see Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/PRSGO/B271.) Nine titles were excluded following this in-depth review. Reasons for exclusion included the comorbid presence of necrotizing fasciitis, unclear timelines or outcomes, and unclear relation between TSS and a surgical procedure. A total of 67 articles describing 96 patients were included in our qualitative review (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Descriptive statistics of collected variables. A, Frequency distribution of patient age (in 5-year increments). Most patients were between 21 and 40 years of age. B, Distribution of days to onset of TSS symptoms or admission. The red bars represent the median (4 days) ± the interquartile range (6.75 days). C, Number of reports by decade. Most reports were published within the first decade since recognition of TSS. D, Frequency distribution of surgical procedure specialties preceding onset of TSS.

In our review series, 38 (39.6%) patients were men and 58 (60.4%) were women. The mean reported patient age was 34.1 years with an SD of 15.5 years and a range from 4 to 73 years; the most commonly reported age group was that between 26 and 30 years of age (Fig. 4A). The median number of postoperative days to onset of symptoms or hospital admission for TSS was 4 days, with an interquartile range of 6.75 days and a range from 1 to 44 days (Fig. 4B). Of the 96 patients, 73 (76%) did not suffer permanent complications. The remaining 23 (24%) patients suffered permanent complications, including additional procedures (eg, hysterectomy, cholecystectomy, skin grafting), amputations, reduced range of motion at a joint, or eventual death (Table 1). Nine (9.38%) patients in our review series eventually expired due to TSS (Table 1). The medical histories of 59 (61.5%) patients were considered noncontributory by the authors of their respective reports (Table 1). An even number of reports of postoperative TSS were published in the past 2 decades (excluding the case presented herein), 19 (28.4%) reports were published between 1990 and 1999, and 26 (38.8%) reports were published between 1980 and 1989 (Fig. 4C). Most of the surgical procedures preceding onset of TSS fell within the domain of plastic surgery, followed by orthopedic surgery and otolaryngology, respectively (Fig. 4D).

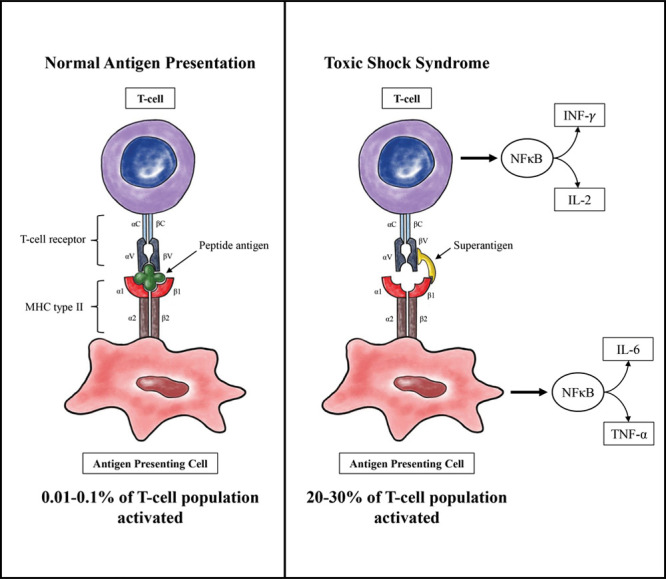

Fig. 4.

Schematic of normal T-cell activation and abnormal T-cell activation induced by superantigen. Note that more inflammatory markers are secreted downstream than are shown in the figure.

Table 1.

Select Variables from Case Reports Meeting Inclusion Criteria of Our Systematic Review

| Study | Year | Patient Age | Patient Sex | Surgical Procedure | Days to Onset | Complications/Additional Procedures | Mortality | Culture Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elkbuli et al18 | 2018 | 31 | F | Cesarean section | 17 | Hysterectomy and bilateral salpingectomy | No | Clostridium sordellii |

| Tomura et al8 | 2017 | 35 | M | Right lumbar melanoma excision | 6 | None | No | – |

| Komuro et al61 | 2017 | 33 | F | Cesarean section | 37 | None | No | – |

| Suga et al62 | 2016 | 40 | F | Mastectomy, SLNB, and immediate subpectoral implant-based reconstruction | 10 | None | No | – |

| 54 | F | Mastectomy, SLNB, and immediate subpectoral implant-based reconstruction | 8 | None | No | – | ||

| Chan et al63 | 2015 | 5 | F | Open reduction and K-wiring of lateral condyle fracture | 14 | None | No | Pin sites grew enterotoxin A, G, I, and TSST-1-producing SA |

| Rimawi et al64 | 2014 | 23 | F | Cesarean section | 7 | Hysterectomy | No | Alpha-toxin-producing Clostridium septicum |

| Yadav et al65 | 2014 | 25 | M | Inguinal hernia repair | 2 | None | No | – |

| Shimizu et al66 | 2014 | 46 | M | ORIF and fasciotomy for left tibia/fibula fracture | 21 | None | No | – |

| Hung and Rajeev20 | 2013 | 24 | F | Total thyroidectomy | 2 | None | No | – |

| Al-ajmi et al16 | 2012 | 39 | F | Laparoscopic left salpingectomy | 1 | – | Yes | Blood grew GAS |

| 31 | F | Elective tubal ligation | 1 | Bilateral salpingectomy | No | Intraperitoneal fluid grew GAS | ||

| Tare et al67 | 2010 | 36 | F | Left mastectomy with DIEP flap reconstruction | 8 | – | Yes | Wound fluid grew TSST-1-producing MRSA |

| Vendemia and Rohde43 | 2009 | 55 | F | Right tissue expander placement with AlloDerm | 35 | None | No | Periprosthetic wound culture grew TSST-1-producing SA |

| Shoji et al68 | 2007 | 61 | M | Thoracotomy with mediastinal lymph node dissection | 5 | None | No | – |

| Jarrahy et al69 | 2007 | 47 | F | Abdominoplasty | 44 | Anterior wall MI, heart failure, bilateral sensorineural hearing loss | No | Drain fluid grew SA |

| Kastl et al70 | 2007 | 35 | M | Rectal mucosal biopsy | 1 | None | No | Rectal swab grew pyogenic exotoxin (SpeA, B, F, G, J)-producing GAS |

| Strenge et al39 | 2006 | 45 | M | Excision of ganglion cyst | 3 | None | No | Wound cultures grew SA |

| Agerson and Wilkins21 | 2005 | 40 | F | TRAM flap reconstruction of right breast; right salpingo-oophorectomy; left tubal ligation | 15 | None | No | Abdominal wall abscess grew GAS and Klebsiella |

| Goksugur et al71 | 2003 | 52 | M | Laparotomy with lymph node sampling | 2 | None | No | Blood and wound cultures grew SA |

| Odom et al72 | 2001 | 56 | F | L2 corpectomy with L1 to L3 interbody fusion and debridement of abscess | 2 | None | No | Abscess grew SA* |

| Gwan-Nulla et al73 | 2001 | 48 | M | Sigmoid colectomy with end colostomy | 18 | None | No | Wound culture grew SA |

| Chadwell et al41 | 2001 | 47 | M | Bilateral polypectomy, total ethmoidectomy, sphenoidotomy, frontal sinusotomy, and right antrostomy | 18 | None | No | Nasal stents and blood cultures grew TSST-1-producing SA |

| Umeda et al11 | 2000 | 27 | F | Suction-assisted lipectomy | 2 | Meshed skin autograft over 22% TBSA due to repeat debridement | No | Wound cultures grew SA |

| Rutishauser et al22 | 1999 | 43 | M | Elective herniotomy | 2 | Right orchiectomy | No | Wound cultures grew GAS |

| 55 | F | Tetanus vaccine administration | 4 | None | No | Blood cultures grew GAS | ||

| Kato et al74 | 1999 | 23 | F | Internal fixation of humerus fracture | 4 | Reduced elbow ROM | No | Wound grew enterotoxin C and TSST-1-producing SA |

| Birdsall et al75 | 1999 | 14 | F | Closed reduction of proximal humerus and fixation with K wires | 14 | None | No | Blood and wound cultures grew TSST-1-producing SA |

| Kotlarz et al76 | 1998 | 62 | F | Mastoidectomy | 3 | None | No | Wound cultures grew enterotoxin B-producing SA |

| Holm and Mühlbauer44 | 1998 | 58 | F | Bilateral exchange of silicone implants (subglandular) | 4 | None | No | 2-mL periprosthetic fluid grew SA |

| Bitti et al19 | 1997 | 29 | F | Cesarean section | 2 | - | Yes | Intraperitoneal cultures grew Clostridium sordellii |

| Younis et al77 | 1996 | 5 | M | Functional endonasal sinus surgery | 10 | None | No | Direct sinus cultures grew toxin-producing SA |

| 7 | F | Functional endonasal sinus surgery | 5 | None | No | Direct sinus cultures grew toxin-producing SA | ||

| 32 | M | Functional endonasal sinus surgery | 35 | None | No | Blood and sinus cultures grew toxin-producing SA | ||

| 8 | M | Functional endonasal sinus surgery | 7 | None | No | Blood and sinus cultures grew toxin-producing SA | ||

| 27 | M | Functional endonasal sinus surgery | 10 | None | No | Direct sinus cultures grew toxin-producing SA | ||

| Mills and Swiontkowski23 | 1996 | 29 | M | Tibial hardware removal | 2 | - | Yes | Bullous fluid grew 3+ GAS |

| Grimes et al78 | 1995 | 4 | F | Removal of Steinmann pins from iliac crest | 9 | - | Yes | Wound cultures grew SA |

| 4 | F | Right femoral valgus osteotomy | 22 | None | No | Pin sites grew SA | ||

| Poblete et al45 | 1995 | 21 | F | Elective augmentation mammaplasty (subglandular) | 6 | Bilateral transmetacarpal amputations; bilateral BKAs | No | Blood cultures grew enterotoxin B-producing SA |

| Graham et al13 | 1995 | 42 | F | Oophorectomy | 2 | None | No | 12 out of 12 patients had negative blood cultures |

| 64 | F | Lumbar sympathectomy | 2 | None | No | |||

| 15 | M | Patellar realignment | 5 | None | No | |||

| 40 | F | Hysterectomy | 4 | None | No | |||

| 28 | M | Excision of navicular bone | 4 | None | No | |||

| 45 | F | Cholecystectomy | 8 | None | No | |||

| 48 | F | Cholecystectomy | 9 | None | No | |||

| 26 | M | Pilonidal cystectomy | 5 | None | No | |||

| 61 | F | Breast biopsy | 2 | None | No | |||

| 26 | F | Chest tube placemen | 4 | None | No | |||

| 29 | M | Nasal septoplasty | 1 | None | No | |||

| 66 | M | Percutaneous angioplasty | 1 | None | No | |||

| Cederna79 | 1995 | 47 | F | TRAM flap reconstruction of left breast | 7 | 33% of TRAM flap lost; latissimus flap required for coverage | No | Small amounts of serous fluid from breast and abdomen grew SA |

| Miller36 | 1994 | 45 | M | L1 laminectomy and discectomy | 3 | None | No | Serosanguinous fluid in deep tissue layer yielded light growth of SA |

| Rhee et al10 | 1994 | 36 | F | Abdominoplasty with suction-assisted lipectomy | 3 | None | No | Wound and drain cultures grew SA |

| 43 | F | Suction-assisted lipectomy | 4 | None | No | – | ||

| Abram et al42 | 1994 | 30 | M | Functional endonasal sinus surgery | 1 | None | No | Nasal cultures grew SA |

| 32 | F | Functional endonasal sinus surgery | 1 | None | No | Nasal cultures grew SA | ||

| 14 | F | Second-stage endonasal clean-out | 1 | None | No | Nasal and throat cultures grew SA | ||

| 25 | F | Functional endonasal sinus surgery | 21 | None | No | Throat cultures grew SA | ||

| 8 | M | Second-stage endonasal clean-out | 5 | None | No | Nasal cultures grew SA† | ||

| Miller et al80 | 1994 | 61 | F | Endoscopic bilateral ethmoidectomy, sphenoidotomy, maxillary antrostomy, and septoplasty | 25 | None | No | Sinus cultures grew SA |

| Bosley et al9 | 1993 | 14 | F | Mole excision | 1 | Cardiac arrest, PE | Yes | Wound culture grew TSST-1-producing SA |

| Gosain and Larson48 | 1992 | 33 | F | Bilateral breast reconstruction with latissimus dorsi musculocutaneous flaps; immediate silicone implants | 28 | None | No | – |

| Shlasko et al12 | 1991 | 29 | M | Pilonidal cystectomy | 3 | None | No | – |

| Croall et al81 | 1989 | 27 | M | MCL repair | 8 | None | No | Synovial fluid grew enterotoxin B-producing SA |

| Frame et al82 | 1988 | 17 | M | Prominent ear correction | 3 | – | – | Wound cultures grew TSST-1-producing SA |

| Tobin et al47 | 1987 | 39 | F | Left permanent prosthesis, right mastectomy with immediate implant-based reconstruction | 5 | None | No | Wound cultures grew TSST-1-producing SA |

| 57 | F | L subpectoral tissue expander | 3 | None | No | – | ||

| 29 | F | Herniorrhaphy and septorhinoplasty | 1 | None | No | Nasal cultures grew TSST-1-producing SA | ||

| Grayson and Saldana32 | 1987 | 20 | M | Tenolysis of FDS and FDP | 35 | None | No | Wound fluid grew enterotoxin B-producing SA |

| Murphy et al83 | 1987 | 40 | F | Lumpectomy | 2 | None | No | Wound discharge grew enterotoxin C-producing SA |

| Dreghorn et al84 | 1987 | 26 | M | Repair of MCL | 5 | Reduced ROM at knee | No | Synovial fluid grew SA |

| Jacobson and Kasworm33 | 1986 | 27 | F | Septoplasty | 1 | Right BKA, left Syme’s amputation, Volkmann’s contracture of left forearm | No | Vaginal and maxillary sinus cultures grew TSST-1-producing SA |

| 34 | M | Septoplasty | 1 | None | No | – | ||

| 29 | F | Septoplasty | 1 | None | No | Nasal cultures grew SA | ||

| Wagner and Toback40 | 1986 | 26 | F | Septoplasty | 2 | None | No | Nasal cultures grew SA |

| Giesecke and Arnander46 | 1986 | 33 | F | Bilateral primary augmentation mammoplasty (subglandular) | 2 | None | No | Periprosthetic fluid grew enterotoxin F-producing SA |

| Vanderheyden et al85 | 1986 | 30 | F | Cesarean section | 5 | None | No | – |

| Smith et al34 | 1986 | 30 | M | Extensor tenosynovectomy and side-to-side juncture (EDC ring to small finger) | 4 | None | No | Wound cultures grew TSST-1-producing SA |

| Shaffer et al86 | 1986 | 44 | M | Orthotopic liver transplant and right adrenalectomy | 16 | None | No | Wound cultures grew SA |

| Farber et al15 | 1984 | 19 | M | Arthroscopy | 1 | Cardiopulmonary arrest requiring bypass | Yes | Synovial fluid grew exotoxin C-producing SA |

| Beck et al87 | 1984 | 73 | M | Cholecystectomy | 28 | – | Yes | Small sinus tract grew enterotoxin F-producing SA |

| Spotkov et al88 | 1984 | 21 | F | Diagnostic laparotomy for bleeding cyst of corpus luteum | 7 | None | No | Wound drainage grew enterotoxin A, F-producing SA |

| Toback et al89 | 1983 | 21 | M | Septorhinoplasty | 1 | None | No | Nasal cultures grew SA |

| Aganaba et al35 | 1983 | 26 | M | Orchidectomy | 4 | None | No | Deep wound culture grew enterotoxin F-producing SA |

| Moyer et al90 | 1983 | 18 | F | Patellar shaving procedure | 3 | None | No | Synovial cultures grew SA |

| 60 | M | Arthrotomy and patellectomy | 2 | Cholecystectomy | No | Synovial cultures grew SA | ||

| Bresler91 | 1983 | 35 | F | Removal of R breast implant | 7 | None | No | Periprosthetic fluid grew SA |

| Barnett et al92 | 1983 | 32 | F | Right subglandular breast prosthesis exchange | 7 | None | No | Periprosthetic fluid grew SA |

| Thomas et al93 | 1982 | 25 | F | Submucous resection and rhinoplasty | 1 | None | No | – |

| Bartlett et al94 | 1982 | 31 | F | Removal of granulation tissue (bilateral augmentation incisions failed to heal) | 1 | – | Yes | – |

| 53 | F | Vesico-urethral suspension | 4 | None | No | Suture abscess grew SA | ||

| McClelland et al95 | 1982 | 36 | M | Wide excision with STSG | 20 | None | No | – |

| Knudsen et al96 | 1981 | 21 | F | Bilateral primary augmentation mammoplasty | 4 | None | No | Right breast cavity grew SA |

| Silver et al97 | 1981 | 34 | M | Amputation of left index finger due to trauma | 3 | None | No | 0.25 cc serous fluid expressed from incision grew SA |

*Blood cultures eventually grew SA, but this was too remote from onset of toxic shock symptoms.

†Stool testing was also positive for Clostridium difficile in the patient.

BKA, below-knee amputation; DIEP, deep inferior epigastric artery perforator; EDC, extensor digitorum communis; FDP, flexor digitorum profundus; FDS, flexor digitorum superficialis; GAS, group A Streptococci; MCL, medial collateral ligament; MI, myocardial infarction; ORIF, open reduction, internal fixation; ROM, range of motion; SA, Staphylococcus aureus; SLNB, sentinel lymph node biopsy; STSG, split-thickness skin graft; TBSA, total body surface area; TRAM, transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous.

DISCUSSION

The mortality rate in our review (9.38%) is lower than that of other reports; this may reflect publication bias and advances in ICU care over time. The average time between TSS diagnosis/treatment and death was 6.78 days, with a range from 12 hours to 18 days. Mortality tended to occur early (<2 days) when due to the shock itself or late (>14 days) due to systemic complications such as cardiopulmonary arrest. Notably, the surgical procedures that most commonly preceded TSS were those that extensively involved the skin (plastic surgery, orthopedic surgery) or mucosal surfaces (otolaryngology), suggesting that sites colonized with toxin-producing bacteria may result in presentation only after disruption of the integrity of the epithelial or mucosal barrier.

Although our patient suffered TSS after extensive surgery, it is important to note that postoperative TSS may present even after relatively simple procedures. Two papers describe TSS in patients following the removal of skin lesions.8,9 Suction-assisted lipectomy,10,11 pilonidal cyst excision,12,13 surgical biopsy,13,14 arthroscopy,15 and elective tubal ligation16 represent just some of the procedures in our review. Furthermore, our review of the literature demonstrates that patients affected by postoperative TSS are often young and in otherwise good health.

The virulence factors responsible for TSS are produced mainly by Gram-positive organisms, especially SA and GAS. However, they are also known to be produced by some Gram-negative bacteria, Mycoplasma spp., and certain viruses.4,17 In our series of postoperative TSS, most causative organisms, if identified, were GAS or SA—however, 2 reports described very virulent TSS following obstetrical procedures that led to the isolation of Clostridium sordellii.18,19 One of these patients died.19 Six reports included in our review reported cultures that grew beta-hemolytic Streptococcus.14,16,20–23 Streptococcal TSS carries a much higher mortality than staphylococcal TSS, with a mortality rate of up to 80% reported in some of the literature.4,24

Pathophysiology

Despite rapid deterioration, patients with TSS may not present with evidence of infection. This is because only a critical mass of toxin-producing bacteria with concomitant epithelial or mucosal disruption is needed. It is the toxins produced by the bacteria that cause the presentation as opposed to a runaway infection by any 1 microorganism.

The word exotoxin refers to virulence factors that are genetically encoded and secreted. They are usually heat labile (but not always, eg, SEB, a type of bacterial superantigen17) and are highly toxic. The term enterotoxin refers to exotoxins that have an effect on the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, thereby producing GI symptoms (a prominent feature in most cases of TSS). The causative toxins behind TSS are usually referred to as “superantigens,” a term first used in the 1980s to describe the mechanism by which streptococcal enterotoxin B stimulates T-cell populations.25 Nearly all superantigens are exotoxins, and most are also enterotoxins.26 Of note, the staphylococcal TSS toxin 1 (TSST-1) is responsible for nearly 95% of menstrual TSS and up to 50% of nonmenstrual TSS, making it the most common causative toxin.4,27

The pathogenicity of superantigens is due to the nonconventional activation of T-cells by antigen-presenting cells (APCs). Normally, APCs present processed peptide fragments to T-cell receptors (TCRs) by way of specific peptide-binding grooves in the major histocompatibility class II (MHC II) protein. This selective process results in the activation of only about 0.01% of the T-cell population.4 By contrast, superantigens bind as unprocessed proteins to both the MHC class II protein and TCR (Fig. 4). They are thought to bind to the variable Vβ region of the TCR (although some bind to the α chain), and bind distant from the normal peptide-binding groove on the MHC II protein.4,26,28 This results in the aberrant activation of up to 20%–30% of the T-cell population. Once a superantigen has cross-linked that T-cell and APC, there is a rapid increase in cytokine expression by both cell types. This is thought to be primarily due to the activation of nuclear factor κB.29

Superantigens are extremely potent, with human T-cell sensitivity noted at as little as 1 fg/mL in vitro.17 GI symptoms have been noted with ingestion of less than 1 μg of staphylococcal enterotoxin.30

Clinical Presentation

It has been suggested that the onset of postoperative TSS most commonly occurs by the second postoperative day.26,31 Our review demonstrated widespread variability in the timeline of postoperative TSS; though, Figure 3B shows that most cases became apparent within 10 days.

Of the 96 patients in our review, at least 52 were described as presenting with symptoms that included nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea. This highlights the enterotoxic nature of many superantigens. Furthermore, some manner of pain was frequently reported. For example, 2 reports described patients with severe hand and wrist pain following hand surgery, whereas another described nasal pain in a septoplasty patient.32–34 The pain in TSS has been described as severe and relentless, making it a common impetus for patients to seek medical attention.4

A benign-appearing wound is another common feature of postoperative TSS, and this frequently leads to a delay in diagnosis.4,26,28 Several case reports in our review explicitly noted the normal appearance of surgical wounds, even if these later grew the causative pathogen. For example, 1 report described a normal looking wound that eventually grew enterotoxin F-producing SA from deep swabs.35 Another described an unremarkable wound that yielded “light” growth of SA from minimal serosanguinous fluid within the deep tissue layers.36 Notably, the death of a 14-year-old girl was reported following TSS that developed after mole excision.9 The authors note that although the surgical wound appeared dry and normal, debrided tissue eventually grew TSST-1 producing SA.9

After onset of symptoms, multiorgan failure can occur within as little as 8–12 hours.4 Multiorgan failure is a prominent feature of the clinical case definitions proposed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. These were first developed in 1980 and have undergone only slight modifications, with the most recent update occurring in 2011.37 However, strict adherence to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention criteria may only identify the most severe cases of TSS. The authors noted that a changing understanding of TSS pathophysiology and presentation over time has demonstrated a wider range of severity than originally suggested and that advances in supportive care have likely begun to prevent the most severe manifestations of the disease.37

Less than 5% of staphylococcal TSS present with positive blood culture.4,38 One series of 12 patients who developed postoperative TSS did not show a single patient with positive blood cultures.13 Most commonly, SA was eventually isolated from the surgical wound,11,34,39 and sometimes from nasal40–42 or rectal14 swabs. If foreign bodies were involved in the initial surgery, tissue or fluid around the foreign body frequently grew SA. For example, in cases that involved breast prostheses, SA was frequently isolated from periprosthetic fluid.43–46 In contrast, streptococcal TSS more commonly presents with concomitant bacteremia.4 This was the case for 2 out of 6 reports of streptococcal TSS in our review.16,22

Lastly, a late but characteristic feature of TSS is a peeling rash known as desquamation. This classically occurs on the palms of the hands or the soles of the feet (Fig. 2); however, several case reports indicated that it may also develop on the trunk or over regions affected by rash.9,10 Although typically desquamation occurs within 10–21 days of symptom onset,4 there was widespread variability in our report ranging from 347 to 3548 days postoperatively. In the series of 12 postoperative TSS patients described earlier, 11 developed desquamation.13

Treatment

Treatment for TSS involves source control, supportive care, and antibiotic treatment. Source control is a principle that is particularly relevant to postoperative patients, as surgical wounds must be considered a potential source despite the lack of typical signs of infection.4 Once sepsis is diagnosed, antibiotic treatment should be started within an hour,26 and the requisite cultures should be acquired before this. We recommend that wound cultures accompany exploration of the wound early on in addition to standard blood cultures if a postoperative patient presents with symptoms suggestive of TSS. Initial surgical interventions should involve visual inspection for fascial involvement, debridement of any necrotic tissue, surgical biopsy for histopathology, and deep bacterial cultures.49 If packing or any foreign objects are present, they should be removed. If suspicion for staphylococcal TSS is high, a nasal swab may be considered.

Appropriate initial antibiotic therapy has been shown to reduce mortality in sepsis,50 and empiric therapy should be targeted at SA and GAS species. Given the potential for Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), vancomycin, or linezolid should be considered in cases of suspected staphylococcal TSS.51 Linezolid has the added benefit of reducing exotoxin release, including TSST-1.4,52 In cases of suspected streptococcal TSS, penicillin G remains an antibiotic of choice. This is because despite decades of use, Streptococcus pyogenes remains exquisitely sensitive to penicillin.4,49,53 In addition to linezolid, clindamycin, erythromycin, rifampin, and fluoroquinolones have all been demonstrated to reduce bacterial exotoxin release by up to 90%.51 Clindamycin is a common choice in combination with vancomycin or penicillin G.4,51

Resuscitation and supportive care should be performed according to current sepsis guidelines.54 This includes maintaining a target mean arterial pressure of 65 mm Hg in patients requiring vasopressors and administering at least 30 mL/kg of IV crystalloid within the first 3 hours.54

The IV administration (usually 1–2 g/kg) of polyclonal, neutralizing intravenous immune globulin (IVIG) has long been proposed as a potential adjunct in the treatment of TSS. These immunoglobulins can block the activation of T-cells by both staphylococcal and streptococcal superantigens,4 in addition to improving bacterial opsonization, phagocytosis, and destruction.49,55 An observational cohort study in 1999 reported a mortality benefit conveyed by IVIG in cases of streptococcal TSS,56 although this study may have been confounded by the fact that IVIG recipients were also more likely to receive surgery. Results from the INSTINCT trial, which was a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial, were published in 2017. They demonstrated no significant difference between the placebo and intervention groups with regard to both functional status and mortality.57 However, a recent meta-analysis demonstrated a reduction in mortality from 33.7% to 15.7% in patients with clindamycin-treated streptococcal TSS who received IVIG.58 Therefore, there may be a role for IVIG in streptococcal TSS, although further evidence is needed. The utility of IVIG in staphylococcal TSS has been even less well determined. There is currently a European, multicenter, placebo-controlled, randomized trial underway that aims to assess the utility of IVIG in pediatric patients with TSS.59 It hopes to enroll 156 patients and is expected to complete in 2022. Of note, the Infectious Disease Society of America has pointed to the heterogeneity between preparations of IVIG, which may result in variance between studies.49,60

CONCLUSIONS

TSS is a rapidly progressive, potentially fatal complication of surgery that frequently presents with a benign-appearing wound. As the incidence of gram-positive sepsis increases, and as MRSA colonization becomes more common in populations, surgeons must be aware of the potential subclinical presence of toxin-producing strains. Importantly, our review shows that TSS should not be excluded despite young patient age, patient health, or relative simplicity of a procedure. Symptoms such as fever, rash, pain out of proportion to examination, and diarrhea or emesis should prompt inclusion of TSS in the differential diagnosis. It is our hope that the case presented herein, and the systematic review, will aid surgeons in the earlier recognition and treatment of this dangerous syndrome.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Published online 29 May 2020.

Disclosure: The authors have no financial interest to declare in relation to the content of this article.

Related Digital Media are available in the full-text version of the article on www.PRSGlobalOpen.com.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wheeler AP, Bernard GR.Treating patients with severe sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2008;340:207–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martin GS, Mannino DM, Eaton S, et al. The epidemiology of sepsis in the United States from 1979 through 2000. N Engl J Med. 2009;348:1546–1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Todd J, Fishaut M, Kapral F, et al. Toxic-shock syndrome associated with phage-group-i staphylococci. Lancet. 1978;2:1116–1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lappin E, Ferguson AJ.Gram-positive toxic shock syndromes. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009;9:281–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gaventa S, Reingold AL, Hightower AW, et al. Active surveillance for toxic shock syndrome in the United States, 1986. Rev Infect Dis. 1989;11suppl 1S28–S34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Descloux E, Perpoint T, Ferry T, et al. One in five mortality in non-menstrual toxic shock syndrome versus no mortality in menstrual cases in a balanced French series of 55 cases. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2008;27:37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hajjeh RA, Reingold A, Weil A, et al. Toxic shock syndrome in the United States: surveillance update, 1979–1996. Emerg Infect Dis. 1999;5:807–810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tomura Y, Osada SI, Akama T, et al. Case of toxic shock syndrome triggered by negative-pressure wound therapy. J Dermatol. 2017;44:e315–e316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bosley AR, Bluett NH, Sowden G.Toxic shock syndrome after elective minor dermatological surgery. BMJ. 1993;306:386–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rhee CA, Smith RJ, Jackson IT.Toxic shock syndrome associated with suction-assisted lipectomy. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1994;18:161–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Umeda T, Ohara H, Hayashi O, et al. Toxic shock syndrome after suction lipectomy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;106:204–207; discussion 208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shlasko E, Harris MT, Benjamin E, et al. Toxic shock syndrome after pilonidal cystectomy. Report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 1991;34:502–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Graham DR, O’Brien M, Hayes JM, et al. Postoperative toxic shock syndrome. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20:895–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kastl S, Horstkotte MA, Schäfer HJ, et al. “Anal angina”–pelvic sepsis and streptococcal toxic shock syndrome after rectoscopy and mucosal biopsy. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2008;23:225–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Farber BF, Broome CV, Hopkins CC.Fulminant hospital-acquired toxic shock syndrome. Am J Med. 1984;77:331–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Al-ajmi JA, Hill P, O’ Boyle C, et al. Group A streptococcus toxic shock syndrome: an outbreak report and review of the literature. J Infect Public Health. 2012;5:388–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fraser JD, Proft T.The bacterial superantigen and superantigen-like proteins. Immunol Rev. 2008;225:226–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elkbuli A, Diaz B, Ehrhardt JD, et al. Survival from clostridium toxic shock syndrome: case report and review of the literature. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2018;50:64–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bitti A, Mastrantonio P, Spigaglia P, et al. A fatal postpartum Clostridium sordelli associated toxic shock syndrome. J Clin Pathol. 1997;50:259–260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hung JA, Rajeev P.Streptococcal toxic shock syndrome following total thyroidectomy. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2013;95:457–460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Agerson AN, Wilkins EG.Streptococcal toxic shock syndrome after breast reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg. 2005;54:553–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rutishauser J, Funke G, Lütticken R, et al. Streptococcal toxic shock syndrome in two patients infected by a colonized surgeon. Infection. 1999;27:259–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mills WJ, Swiontkowski MF.Fatal group a streptococcal infection with toxic shock syndrome: complicating minor orthopedic trauma. J Orthop Trauma. 1996;10:149–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCormick JK, Yarwood JM, Schlievert PM.Toxic shock syndrome and bacterial superantigens: an update. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2001;55:77–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.White J, Herman A, Pullen AM, et al. The V beta-specific superantigen staphylococcal enterotoxin B: stimulation of mature T cells and clonal deletion in neonatal mice. Cell. 1989;56:27–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Silversides JA, Lappin E, Ferguson AJ.Staphylococcal toxic shock syndrome: mechanisms and management. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2010;12:392–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bohach GA, Fast DJ, Nelson RD, et al. Staphylococcal and streptococcal pyrogenic toxins involved in toxic shock syndrome and related illnesses. Crit Rev Microbiol. 1990;17:251–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pinchuk IV, Beswick EJ, Reyes VE.Staphylococcal enterotoxins. Toxins (Basel). 2010;2:2177–2197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Trede NS, Castigli E, Geha RS, et al. Microbial superantigens induce NF-kappa B in the human monocytic cell line THP-1. J Immunol. 1993;150:5604–5613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tranter HS.Foodborne staphylococcal illness. Lancet. 1990;336:1044–1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Strausbaugh LJ.Toxic shock syndrome. Postgrad Med. 1993;94:107–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grayson MJ, Saldana MJ.Toxic shock syndrome complicating surgery of the hand. J Hand Surg Am. 1987;12:1082–1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jacobson JA, Kasworm EM.Toxic shock syndrome after nasal surgery. Case reports and analysis of risk factors. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1986;112:329–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smith PA, Hankin FM, Louis DS.Postoperative toxic shock syndrome after reconstructive surgery of the hand. J Hand Surg Am. 1986;11:399–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aganaba T, Evans RP, O’Neill P.Toxic shock syndrome after orchidectomy. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1983;286:685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miller SD.Postoperative toxic shock syndrome after lumbar laminectomy in a male patient. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1994;19:1182–1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.DeVries AS, Lesher L, Schlievert PM, et al. Staphylococcal toxic shock syndrome 2000–2006: epidemiology, clinical features, and molecular characteristics. Diep BA, ed. PLoS One. 2011;6:e22997–e22998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Murray RJ.Recognition and management of Staphylococcus aureus toxin-mediated disease. Intern Med J. 2005;35suppl 2S106–S119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Strenge KB, Mangan DB, Idusuyi OB.Postoperative toxic shock syndrome after excision of a ganglion cyst from the ankle. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2006;45:275–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wagner R, Toback JM.Toxic shock syndrome following septoplasty using plastic septal splints. Laryngoscope. 1986;96:609–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chadwell JS, Gustafson LM, Tami TA.Toxic shock syndrome associated with frontal sinus stents. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;124:573–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Abram AC, Bellian KT, Giles WJ, et al. Toxic shock syndrome after functional endonasal sinus surgery: an all or none phenomenon? Laryngoscope. 1994;1048 pt 1927–931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vendemia N, Rohde C.Toxic shock syndrome after prosthetic breast reconstruction with alloderm. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124:173e–174e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Holm C, Mühlbauer W.Toxic shock syndrome in plastic surgery patients: case report and review of the literature. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1998;22:180–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Poblete JV, Rodgers JA, Wolfort FG.Toxic shock syndrome as a complication of breast prostheses. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;96:1702–1708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Giesecke J, Arnander C.Toxic shock syndrome after augmentation mammaplasty. Ann Plast Surg. 1986;17:532–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tobin G, Shaw RC, Goodpasture HC.Toxic shock syndrome following breast and nasal surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1987;80:111–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gosain AK, Larson DL.Toxic shock syndrome following latissimus dorsi musculocutaneous flap breast reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg. 1992;29:571–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schmitz M, Roux X, Huttner B, et al. Streptococcal toxic shock syndrome in the intensive care unit. Ann Intensive Care. 2018;8:88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.MacArthur RD, Miller M, Albertson T, et al. Adequacy of early empiric antibiotic treatment and survival in severe sepsis: experience from the MONARCS trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38:284–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gottlieb M, Long B, Koyfman A.The evaluation and management of toxic shock syndrome in the emergency department: a review of the literature. J Emerg Med. 2018;54:807–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Coyle EA, Cha R, Rybak MJ.Influences of linezolid, penicillin, and clindamycin, alone and in combination, on streptococcal pyrogenic exotoxin a release. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47:1752–1755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Macris MH, Hartman N, Murray B, et al. Studies of the continuing susceptibility of group A streptococcal strains to penicillin during eight decades. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1998;17:377–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rhodes A, Evans LE, Alhazzani W, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock: 2016. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43:304–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mouthon L, Kaveri SV, Spalter SH, et al. Mechanisms of action of intravenous immune globulin in immune-mediated diseases. Clin Exp Immunol. 1996;104suppl 13–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kaul R, McGeer A, Norrby-Teglund A, et al. Intravenous immunoglobulin therapy for streptococcal toxic shock syndrome--a comparative observational study. The Canadian Streptococcal Study Group. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;28:800–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Madsen MB, Hjortrup PB, Hansen MB, et al. Immunoglobulin G for patients with necrotising soft tissue infection (INSTINCT): a randomised, blinded, placebo-controlled trial. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43:1585–1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Parks T, Wilson C, Curtis N, et al. Polyspecific intravenous immunoglobulin in clindamycin-treated patients with streptococcal toxic shock syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;67:1434–1436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.ClinicalTrials.gov. Effectiveness of Intravenous Immunoglobulins (IVIG) in Toxic Shock Syndromes in Children (IGHN2). https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02899702. Accessed January 7, 2019

- 60.Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59:e10–e52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Komuro H, Kato T, Okada S, et al. Toxic shock syndrome caused by suture abscess with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) with late onset after Caesarean section. IDCases. 2017;10:12–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Suga H, Shiraishi T, Takushima A, et al. Toxic shock syndrome caused by methicillin- resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) after expander-based breast reconstruction. Eplasty. 2016;16:e2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chan Y, Selvaratnam V, Garg N.Toxic shock syndrome post open reduction and Kirschner wire fixation of a humeral lateral condyle fracture. BMJ Case Re 2015;2015:bcr2015210090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rimawi B, Graybill W, Pierce J, et al. Necrotizing fasciitis and toxic shock syndrome from clostridium septicum following a term cesarean delivery. Case Reports Obstetrics Gynecol. 2014;2014:724302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yadav R, Bhattarai B, Gupta R, et al. Toxic shock syndrome following inguinal hernia repair: a rare condition. J Coll Medical Sci. 20149 doi:10.3126/jcmsn.v9i2.9689 [Google Scholar]

- 66.Shimizu T, Yamamoto Y, Hosoi T, et al. MRSA toxic shock syndrome associated with surgery for left leg fracture and co-morbid compartment syndrome. J Acute Dis. 2014;3:82–84. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tare M, Durcan J, Niranjan N.A case of toxic shock syndrome following a DIEP breast reconstruction. J Plastic Reconstr Aesthetic Surg. 2010;63:e261–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shoji F, Yoshino I, Osoegawa A, et al. Toxic shock syndrome following thoracic surgery for lung cancer: report of a case. Surg Today. 2007;37:587–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jarrahy R, Roostaeian J, Kaufman MR, et al. A rare case of staphylococcal toxic shock syndrome after abdominoplasty. Aesthet Surg J. 2007;27:162–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kastl S, Horstkotte MA, Schäfer H-J, et al. “Anal angina”--pelvic sepsis and streptococcal toxic shock syndrome after rectoscopy and mucosal biopsy. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2008;232225–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Goksugur N, Ozaras R, Tahan V, et al. Toxic shock syndrome due to Staphylococcus aureus sepsis following diagnostic laparotomy for Hodgkin’s disease. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003;17:732–733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Odom S, Stallard J, Pacheco H, et al. Postoperative staphylococcal toxic shock syndrome due to pre-existing staphylococcal infection: case report and review of the literature. Am Surg. 2001;67:745–747. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gwan–Nulla DN, Casal RS.Toxic shock syndrome associated with the use of the vacuum-assisted closure device. Ann Plas Surg. 2001;47:552–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kato N, Nemoto K, Amako M.Toxic shock syndrome after a closed comminuted fracture surgery at the distal end of the humerus. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 1999;8:165–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Birdsall P, Milne D.Toxic shock syndrome due to percutaneous Kirschner wires. Injury. 1999;30:509–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kotlarz J, Crane J.Toxic shock syndrome after mastoidectomy. Otolaryngology Head Neck Surg. 1998;118:701–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Younis R, Lazar R.Delayed toxic shock syndrome after functional endonasal sinus surgery. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1996;122:83–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Grimes J, Carpenter C, Reinker K.Toxic shock syndrome as a complication of orthopaedic surgery. J Pediatr Orthop. 1995;15:666–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Cederna J.Toxic shock syndrome after transverse rectus abdominis musculocutaneous flap breast reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg. 1995;34:73–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Miller S.Postoperative toxic shock syndrome after lumbar laminectomy in a male patient. Spine. 1994;19:1182–1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Croall J, Chaudhri S.Non-menstrual toxic shock syndrome complicating orthopaedic surgery. J Infect. 1989;18:195–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Frame J, Hackett M.Toxic shock syndrome after a minor surgical procedure. Lancet. 1988;1:1330–1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Murphy P, Holmes W, Wilson T, et al. Non-menstrual associated toxic shock syndrome. Ulster Med J. 1987;56:146–148. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Dreghorn C, Graham J, Rae P.Toxic shock syndrome following repair of a ligament of the knee. Injury. 1987;18:356–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Vanderheyden J, Renard J, Dehaen M, et al. Non-menstrual toxic shock syndrome. A case report and a review of non-menstrual toxic shock syndrome in Western Europe. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1986;22:243–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Shaffer D, Jenkins R, Karchmer A, et al. Toxic shock syndrome complicating orthotopic liver transplantation--a case report. Transplantation. 1986;42:434–437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Beck S, Fenton P, Rollinson P.A fatal case of toxic-shock syndrome following cholecystectomy. Medicine Sci Law. 1984;24:269–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Spotkov J, Ruskin J.Toxic shock syndrome with staphylococcal wound abscess after gynecologic surgery. South Med J. 1984;77:806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Toback J, Fayerman J.Toxic shock syndrome following septorhinoplasty. Implications for the head and neck surgeon. Arch Otolaryngol. 1983;109:627–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Moyer M, Edwards L, BergdollNosocomial toxic-shock syndrome in two patients after knee surgery. Am J Infect Control. 1983;11:83–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Bresler M.Toxic shock syndrome due to occult postoperative wound infection. West J Med. 1983;139:710–713. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Barnett A, Lavey E, Pearl R, et al. Toxic shock syndrome from an infected breast prosthesis. Ann Plast Surg. 1983;10:408–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Thomas S, Baird I, Frazier R.Toxic shock syndrome following submucous resection and rhinoplasty. JAMA. 1982;247:2402–2403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Bartlett P, Reingold A, Graham D, et al. Toxic shock syndrome associated with surgical wound infections. JAMA. 1982;247:1448–1450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.McClelland J, Craig C, Hall W.Toxic shock syndrome in a man. South Med J. 1982;75:1027–1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Knudsen F, Olesen A, Højbjerg T, et al. Toxic shock syndrome. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1981;282:399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Silver M, Simon G.Toxic shock syndrome in a male postoperative patient. J Trauma. 1981;21:650–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.