Abstract

The cardiovascular system is affected broadly by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection. Both direct viral infection and indirect injury resulting from inflammation, endothelial activation, and microvascular thrombosis occur in the context of coronavirus disease 2019. What determines the extent of cardiovascular injury is the amount of viral inoculum, the magnitude of the host immune response, and the presence of co-morbidities. Myocardial injury occurs in approximately one-quarter of hospitalized patients and is associated with a greater need for mechanical ventilator support and higher hospital mortality. The central pathophysiology underlying cardiovascular injury is the interplay between virus binding to the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptor and the impact this action has on the renin-angiotensin system, the body’s innate immune response, and the vascular response to cytokine production. The purpose of this review was to describe the mechanisms underlying cardiovascular injury, including that of thromboembolic disease and arrhythmia, and to discuss their clinical sequelae.

Key Words: arrhythmia, COVID-19, myocardial injury, SARS-CoV-2, thrombosis

Abbreviations and Acronyms: ACE2, angiotensin-converting enzyme 2; ADAM-17, a disintegrin and metalloproteinase domain 17; Ang, angiotensin; ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; CI, confidence interval; CMR, cardiac magnetic resonance; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; CVD, cardiovascular disease; CYP, cytochrome P450; DVT, deep venous thrombosis; HCQ, hydroxychloroquine; hERG, human ether-a-go-go related gene; IL, interleukin; MI, myocardial infarction; OR, odds ratio; RNA, ribonucleic acid; SARS, severe acute respiratory syndrome; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; STEMI, ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction; TMPRSS2, transmembrane serine protease 2; TNF, tumor necrosis factor

Central Illustration

Highlights

-

•

The cardiovascular system is affected in diverse ways by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection (COVID-19).

-

•

Myocardial injury can be detected in ∼25% of hospitalized patients with COVID-19 and is associated with an increased risk of mortality.

-

•

Described mechanisms of myocardial injury in patients with COVID-19 include oxygen supply–demand imbalance, direct viral myocardial invasion, inflammation, coronary plaque rupture with acute myocardial infarction, microvascular thrombosis, and adrenergic stress.

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death worldwide, accounting for 17.8 million deaths in 2017 (1). As a percentage of deaths, communicable diseases, such as that from infection, have been decreasing over the past 2 decades while those from noncommunicable diseases, such as CVD and cancer, have been increasing. At the time of this writing, almost 10 million people worldwide have confirmed severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection, and close to 500,000 have died of the disease. Although originally believed to be a syndrome characterized by acute lung injury, respiratory failure, and death, it is now apparent that severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is further characterized by exuberant cytokinemia, with resultant endothelial inflammation, microvascular thrombosis, and multiorgan failure (2).

Involvement of the cardiovascular system is common in COVID-19 (3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8). Somewhere between one-fifth and one-third of hospitalized patients will have evidence of myocardial injury, defined as the presence of elevated cardiac troponin levels at the time of admission (9, 10, 11, 12). Such patients are generally older and have a higher prevalence of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, coronary artery disease, and heart failure than those with normal troponin levels. Myocardial injury is associated with a greater need for mechanical ventilatory support and higher in-hospital mortality.

The purpose of the current review was to describe the mechanisms producing cardiovascular damage among hospitalized patients with severe COVID-19 infection, including that of thromboembolic disease and arrhythmia, and to discuss their clinical sequelae.

Pathophysiology of Cardiovascular Involvement in COVID-19

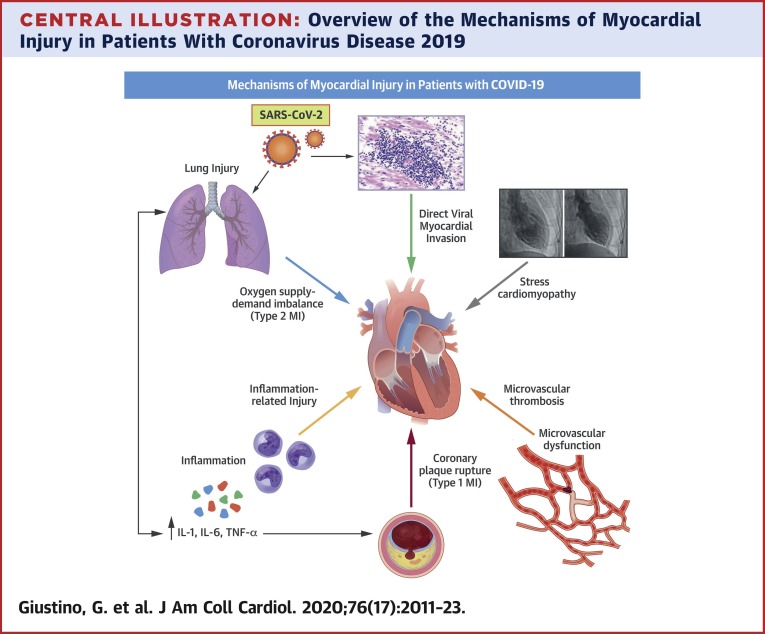

The cardiovascular system is affected broadly by SARS-CoV-2 infection (Central Illustration ). Both direct viral infection and indirect injury resulting from inflammation, endothelial activation, and microvascular thrombosis occur in the context of COVID-19. What determines the extent of CVD is the amount of viral inoculum, the magnitude of the host immune response, and the presence of co-morbidities.

Central Illustration.

Overview of the Mechanisms of Myocardial Injury in Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019

Myocardial injury in the setting of COVID-19 is frequent and associated with poor prognosis. The mechanisms through which COVID-19 can cause myocardial injury are heterogeneous and include oxygen supply–demand imbalance, microvascular and macrovascular thrombosis, inflammation-related injury, stress-induced cardiomyopathy, and direct viral invasion of the myocardium.

COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019; IL = interleukin; MI = myocardial infarction; SARS-CoV-2 = severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; TNF = tumor necrosis factor.

Direct viral myocardial invasion

SARS-CoV-2 is a single-stranded ribonucleic acid (RNA) virus whose outer membrane spike protein (S protein) binds with high affinity to the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor (13). ACE2 serves as a master regulator of the renin-angiotensin system by metabolizing the vasoconstricting and pro-inflammatory angiotensin II (Ang II) to the vasodilating peptide angiotensin 1-7. While binding to ACE2, SARS-CoV-2 uses a host protease, transmembrane protease serine 2 (TMPRSS2), to prime the S protein and facilitate cell entry (14). Once inside the cell, the virus uses the host machinery to translate RNA into polypeptides, including an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase that the virus uses to replicate its own RNA. After synthesis of structural proteins and particle assembly, new virus is released from the cell by exocytosis. Host cells may be disabled or destroyed in the process, potentially triggering an innate immune response (15).

ACE2 and TMPRSS2 are co-expressed in a number of tissues, including the heart, lung, gut smooth muscle, liver, kidney, and immune cells (15). In an autopsy study of patients who died of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), 7 (35%) of 20 hearts were shown to harbor the related coronavirus SARS-CoV (16). Given the extensive homology of SARS-CoV-1 and SARS-CoV-2, and the intensity of SARS-CoV-2 binding to ACE2, it is reasonable to presume that SARS-CoV-2 directly invades human myocardium. To date, there have been only a few reports confirming the presence of viral inclusion bodies or the identification of SARS-CoV-2 genomic RNA from myocardial tissue taken from biopsy-proven COVID-19 myocarditis cases (17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22). In a report of 104 patients with COVID-19 infection who developed acute heart failure and underwent endomyocardial biopsy, 5 were positive for the SARS-CoV-2 genome in the myocardial tissue and associated with typical features of myocarditis, including pronounced intramyocardial inflammation, microvascular thrombosis, and myocardial necrosis. More recently, in a larger autopsy series of consecutive patients, SARS-CoV-2 positivity in cardiac tissues could be documented in 24 (61.5%) of 39 patients (23). Interestingly, cardiac tissues of patients with high viral load in the myocardium had higher expression of proinflammatory cytokines, but this finding was not associated with greater inflammatory cell infiltrates.

SARS-CoV-2, ACE2, and inflammation

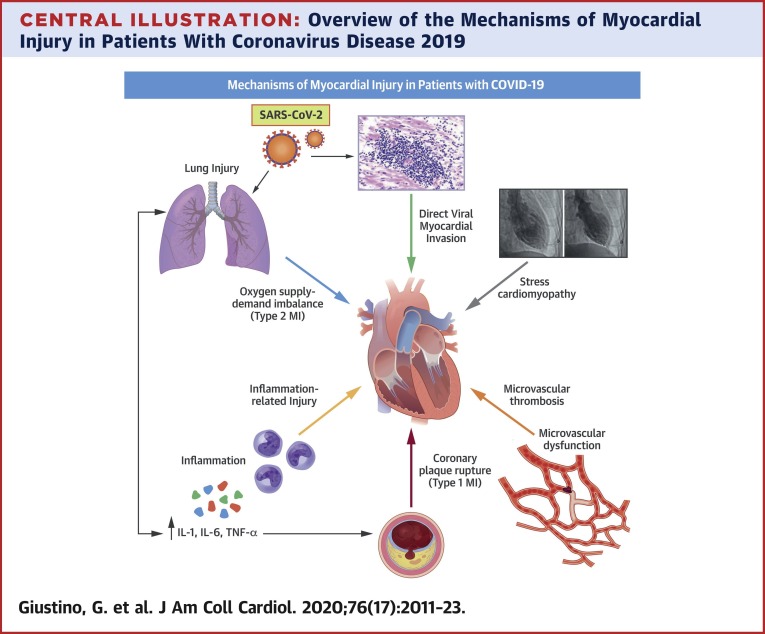

Macrophages are a key component of the innate immune system, and they are a major source of the inflammatory cytokine tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α. Their activation is driven by a disintegrin and metalloproteinase domain 17 (ADAM-17), a transmembrane protease, which is also responsible for the proteolysis and ectodomain shedding of ACE2 (24,25). In the setting of SARS-CoV-2 infection, membrane-bound ACE2 is internalized, leading to decreased receptor density. Because ACE2 is primarily responsible for the conversion of Ang II to angiotensin 1-7, the loss of ACE2 receptor density and down-regulation of ACE2 activity leads to an accumulation of Ang II (Figure 1 ). In turn, increased binding of Ang II to the Ang II type 1 receptor triggers a signaling cascade that leads to ADAM-17 phosphorylation and enhanced catalytic activity (13,24). Activated ADAM-17 increases ACE2 shedding, resulting in further reductions of Ang II clearance, increased Ang II–mediated inflammatory responses, and a vicious positive feedback cycle.

Figure 1.

Interaction Between SARS-CoV-2, ACE2 Transmembrane Protein, and Ang II Levels in Patients With COVID-19

In severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection, the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) transmembrane protein is internalized, leading to decreased receptor density. The loss of ACE2 receptor density and down-regulation of ACE2 activity leads to an accumulation of angiotensin II (Ang II), which exerts vasoconstrictor, profibrotic, and proinflammatory effects. Image created with BioRender. Ang 1-7 = angiotensin 1-7; COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019.

Giving the key role of the ACE2 receptor in the pathophysiology of COVID-19, some have postulated both in favor and against a potential protective benefit of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors. In a large observational study including >10,000 patients who were tested for COVID-19 in the New York University Langone Health electronic health record, treatment with ACE inhibitors or angiotensin-receptor blockers was not associated with a higher incidence of COVID-19 infection or with the likelihood of severe illness (defined as intensive care, mechanical ventilation, or death) among patients who tested positive (26). Similar findings were observed in a large case control study in the Lombardy region of Italy (27). More recently, in a randomized controlled trial testing the role of ramipril in elderly patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement, treatment with ramipril had no effect on the incidence of COVID-19 in the study cohort (11 cases of 102 patients enrolled) (28). Multiple randomized controlled trials are testing whether continuing or interrupting treatment with ACE inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers has an effect on the clinical outcomes of patients with COVID-19 (NCT04338009; NCT04364893).

Endothelial activation and thrombosis

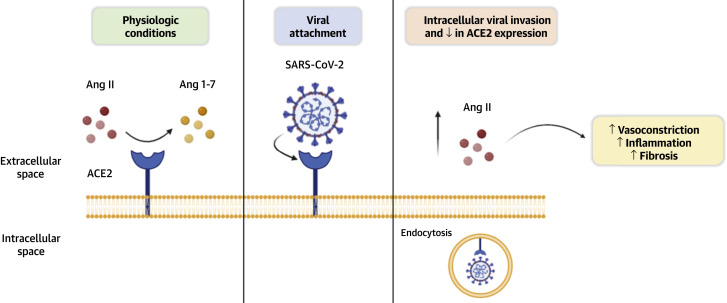

ACE2 is expressed extensively throughout the circulatory system. Vascular smooth muscle co-expresses the ACE2 receptor and TMPRSS2 (15). Similarly, both arterial and venous endothelial cells are characterized by high levels of ACE2 receptor expression (29). Viral replication in localized tissue incites innate immune responses characterized by the release of interferon-γ, resulting in macrophage activation to the M1 phenotype. The subsequent release of interleukin (IL)-1β and IL-6 promotes endothelial activation with the expression of cell adhesion molecules. Inflamed and dysfunctional endothelium soon becomes proadhesive and prothrombotic with increased expression of tissue factor and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (Figure 2 ) (30). In addition, significant elevations in von Willebrand factor levels have been observed in patients with severe COVID-19 infection, which suggest ongoing endothelial activation and damage (31,32). Histological studies have shown evidence of endotheliitis caused by SARS-CoV-2 infection (33).

Figure 2.

Endothelial Activation, Inflammation, and Thrombosis in COVID-19

Inflammatory cytokines and excessive Ang II activity lead to endothelial activation, which is associated with a prothrombotic phenotype and increased endothelial permeability. In addition, SARS-CoV-2 has been shown to directly invade endothelial cells and cause endotheliitis. Image created with BioRender.com. PAI = plasminogen activator inhibitor; TF = tissue factor; vWF = von Willebrand factor; other abbreviations as in Figure 1.

Acute coronary syndromes (type 1 myocardial infarction)

Myocardial infarction (MI) caused by atherosclerotic disease with plaque disruption is termed type 1 MI (34). Several potential mechanisms contribute to the high risk of plaque destabilization and link systemic viral infection with acute coronary ischemic syndromes (35). Viral products known as pathogen-associated molecular patterns entering the systemic circulation activate immune receptors on cells in existing atherosclerotic plaques and predispose to plaque rupture (36). Such pathogen-associated molecular patterns are also believed to activate the inflammasome and result in conversion of nascent pro-cytokines into biologically active cytokines (37). Infection and inflammation can also lead to dysregulation of coronary vascular endothelial function and cause vasoconstriction and thrombosis (38).

Despite these multiple plaque-destabilizing mechanisms through which COVID-19 could precipitate acute coronary syndromes, the clinical frequency of this occurrence and the relative preponderance of one mechanism over another remain uncertain. One of the primary reasons for this uncertainty is the relative infrequency of performing diagnostic angiography in the setting of COVID-19 due to appropriate concerns regarding the safety of health care workers. To minimize the transmission of this contagious virus, cardiac catheterization with coronary angiography has been performed in a relatively small proportion of patients with symptoms and electrocardiographic evidence of acute myocardial injury. The diagnostic confirmation of COVID-19 using real-time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction assays obtained from nasopharyngeal swabs can often take hours or days. Delaying catheterization while waiting for test results in patients with uncertain COVID-19 status exceeds the time frame within which primary revascularization is beneficial for myocardial salvage. Consequently, urgent coronary angiography and percutaneous revascularization have been reserved only for patients with ST-segment elevation acute MI (STEMI) in specific settings and are usually avoided in non-STEMI cases, as recommended by professional societies (39, 40, 41).

Supply–demand imbalance (type 2 MI)

MI resulting from an imbalance between myocardial oxygen supply and demand is classified as type 2 MI (34). In particular, 4 specific mechanisms in the context of COVID-19 seem relevant: 1) fixed coronary atherosclerosis limiting myocardial perfusion; 2) endothelial dysfunction within the coronary microcirculation; 3) severe systemic hypertension resulting from elevated circulating Ang II levels and intense arteriolar vasoconstriction; and 4) hypoxemia resulting from acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) or from in situ pulmonary vascular thrombosis. In the setting of sepsis, lung injury, and respiratory failure, severe physiological stress can be associated with elevations in biomarkers of myocardial strain and injury (42, 43, 44). Individuals with atherosclerosis are susceptible to myocardial ischemia and infarction in the setting of systemic inflammatory states and severe infections, including H1N1 influenza and coronavirus pneumonia (8,45,46). Infection in general, and pneumonia in particular, can disrupt the balance between myocardial oxygen supply and demand. The physiological demands triggered by systemic infection can be so great that this supply–demand imbalance may exist even in the absence of atherothrombotic plaques. It is challenging to distinguish patients with non-STEMI from those with myocarditis or demand-based myocardial injury in the setting of fever, tachycardia, or hypoxemia due to ARDS. It is very likely that multiple concurrent mechanisms of myocardial injury overlap within individual patients.

Pre-hospital death in CVD (type 3 MI)

Suspicion of MI without the ability to obtain biomarker confirmation is termed type 3 MI. During the surge of COVID-19, patients avoided hospital-based care (47, 48, 49, 50, 51). Therefore, sudden death and unexplained death at home in persons with known coronary heart disease suspected of having COVID-19 could have been secondary to type 3 MI.

Myocardial injury resulting from severe systemic inflammation

Severe systemic inflammation is a postulated cause of myocardial injury in cases of COVID-19 (52). Patients with sepsis-associated cardiomyopathy have an inflammatory profile, characterized by high circulating levels of a number of cytokines, including IL-6 and TNF-α (53). In vitro exposure to IL-6 reduced cultured rat cardiomyocyte contractility (54), and administration of recombinant TNF-α in a canine model produced left ventricular systolic dysfunction (55). The mediators of these toxic responses include modulation of calcium channel activity (56, 57, 58), and nitric oxide production, which is believed to govern myocardial depression in systemic hyperinflammatory states, including sepsis. Compounding these adverse responses is the potential for several antiviral drugs to cause mitochondrial dysfunction and cardiotoxicity (59).

Incidence and Clinical Impact of Myocardial Injury in COVID-19

The incidence of major cardiovascular events, including both types 1 and 2 MI, increases in association with respiratory infections and carries a poor prognosis (8). In the setting of COVID-19, a substantial proportion of hospitalized patients exhibit signs of myocardial injury based on biomarkers and electrocardiographic or imaging criteria (3,4,7,9,10,12,60). Significant variation exists in myocardial injury definitions used in published reports (Table 1 ). Myocardial injury has been defined as any evidence of serum troponin elevations (with variations in the troponin assay used) with or without accompanying electrocardiographic or echocardiographic evidence of acute ischemia (3,4,7,9,10,60). The incidence ranges between 7% and 40%, reflecting the significant heterogeneity of the definitions used and the population studied. Irrespective of its definition, myocardial injury has been consistently associated with increased risk of in-hospital complications and mortality. Cardiac troponin elevation correlates with higher levels of inflammatory biomarkers (e.g., ferritin, IL-6, C-reactive protein), coagulation biomarkers (e.g., D-dimer), and the severity of hypoxemia and respiratory illness (e.g., lower partial arterial pressure of oxygen/fraction of inspired oxygen ratio and need for mechanical ventilation).

Table 1.

Selected Studies (With Sample Size ≥100 Patients) Reporting the Incidence and Association of Myocardial Injury With Mortality in Patients With COVID-19

| First Author (Ref. #) | Country | No. | Definition of Myocardial Injury | Incidence | Age∗ (yrs) | Male | Impact of Myocardial Injury on Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lala et al. (10) | United States | 2,736 | Serum levels of TnI >0.03 ng/ml | 985/2,736 (36%) | 66 | 59.6% | TnI elevations >0.03–0.09 ng/ml and >0.09 ng/ml were both associated with increased risk of in-hospital mortality after multivariable adjustment (adjusted OR: 1.75; 95% CI: 1.37–2.24, and adjusted OR: 3.03; 95% CI: 2.42-3.80, respectively) |

| Shi et al. (60) | China | 671 | Serum levels of TnI >99th percentile URL | Not reported | 63 | 48.0% | TnI elevations >0.026 ng/ml were strongly associated with increased risk of in-hospital mortality (adjusted OR: 4.56; 95% CI: 1.28–16.28) |

| Shi et al. (4) | China | 416 | Serum levels of TnI >99th percentile URL | 82/416 (19.7%) | 64 | 49.3% | TnI elevations were associated with increased risk of mortality (51.2% vs. 4.5%), ARDS (58.5% vs. 14.7%), AKI (8.5% vs. 0.3%), and coagulopathy (7.3% vs. 1.8%) TnI elevations were associated with increased risk of in-hospital mortality after multivariable adjustment (adjusted HR: 3.41; 95% CI: 1.62–7.16) |

| Guo et al. (3) | China | 187 | Serum levels of TnT >99th percentile URL | 52/187 (27.8%) | 58.5 | 48.7% | Associated with increased risk of mortality (59.6% vs. 8.9%), ARDS (57.7% vs. 11.9%), VT/VF (17.3% vs. 1.5%), AKI (36.8% vs. 4.7%), and coagulopathy (65.8% vs. 20.0%) Mortality associated with myocardial injury was increased among those with pre-existing cardiovascular disease |

| Zhou et al. (5) | China | 191 | High-sensitivity cardiac TnI >28 pg/ml | 24/45 (17%) | 56 | 62% | Associated with increased risk of in-hospital mortality (univariate OR: 80.07; 95% CI: 10.34–620.36) |

AKI = acute kidney injury; ARDS = acute respiratory distress syndrome; CI = confidence interval; COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019; HR = hazard ratio; OR = odds ratio; TnI = troponin I; URL = upper reference limit; VF = ventricular fibrillation; VT = ventricular tachycardia.

Mean or median, as reported.

The largest available outcomes study of myocardial injury is a multicenter retrospective analysis from a health care system in New York City (10). A total of 2,736 patients were included, of whom 985 patients (36%) had evidence of myocardial injury at the time of presentation, based on any elevation of cardiac troponin I above the upper limit of normal (0.03 ng/ml). Patients experiencing myocardial injury were older than those without troponin increases and had more co-morbidities, but only ∼30.0% had a history of coronary artery disease. After adjusting for baseline confounders, troponin elevations >0.03 to 0.09 ng/ml and >0.09 ng/ml were both associated with increased risk of in-hospital mortality (adjusted odds ratio [OR]: 1.75; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.37 to 2.24, and adjusted OR: 3.03; 95% CI: 2.42 to 3.80, respectively). Similar findings were also reported in another large single-center study from China of 671 patients (60). Of note, the area under the receiver-operating characteristic curve of initial cardiac troponin I for predicting in-hospital mortality was 0.92 (95% CI: 0.87 to 0.96; sensitivity: 0.86; specificity: 0.86) with a cutoff concentration of cardiac troponin I of 0.026 ng/ml. After multivariable adjustment, cardiac troponin I elevations >0.026 ng/ml were strongly associated with increased risk of in-hospital mortality (adjusted OR: 4.56; 95% CI: 1.28 to 16.28). Of note, in this study, other cardiac biomarkers were associated with increased risk of in-hospital mortality, including creatine-kinase myocardial band elevations and N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide elevations (20).

The presentation of COVID-19–related myocardial injury is atypical. Most patients with myocardial injury do not have previously diagnosed CVD and frequently present without chest pain (3,4). Myocardial injury and other manifestations of end-organ damage appear to occur later (>14 days) after the onset of initial symptoms, possibly reflecting a more advanced stage of the disease. At the present time, it remains uncertain whether myocardial injury is simply a marker of disease severity or directly contributes to COVID-19 morbidity and mortality. Most available studies do not include echocardiographic data, and therefore the prevalence and severity of left ventricular dysfunction associated with myocardial injury are unknown. In several modest-sized studies reporting the echocardiographic findings in patients with COVID-19, the most common echocardiographic abnormalities were right ventricular dilatation and right ventricular dysfunction, with only a small percentage of patients having left ventricular systolic dysfunction (61, 62, 63). Also poorly defined is the true incidence of type 1 MI. In an 18-patient case series of COVID-19 STEMI, 14 patients had focal ST-segment elevations and 4 had diffuse ST-segment elevations (64). Focal ST-segment elevation was associated with greater left ventricular dysfunction and regional wall motion abnormalities. Only 9 patients underwent diagnostic coronary angiography, of whom 6 (67%) had obstructive coronary artery disease. Patients with type 1 MI had higher levels of troponin and D-dimer but lower in-hospital mortality compared with those with nonischemic myocardial injury. A high prevalence of nonobstructive disease in patients with COVID-19 presenting with ST-segment elevation on electrocardiography was also shown in a larger series of 28 patients who underwent invasive coronary angiography in northern Italy (65).

Takotsubo or stress-induced cardiomyopathy is another potential mechanism of myocardial injury in the setting of COVID-19. A single-center study from New York City included 118 consecutive patients with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 infection who underwent formal transthoracic echocardiographic evaluation; 5 (4.2%) had imaging features compatible with a diagnosis of takotsubo cardiomyopathy (i.e., circumferential hypokinesis or akinesis of the apical and mid-wall segments without a discrete epicardial coronary artery distribution) (66). Of note, all patients were male and had higher degrees of cardiac troponin elevations compared with patients with myocardial injury without features of takotsubo cardiomyopathy on transthoracic echocardiography. Patients with myocardial injury and features of takotsubo cardiomyopathy had higher rates of in-hospital mortality and major complications from COVID-19 compared with patients without myocardial injury.

The precise incidence of confirmed acute myocarditis at the time of symptomatic COVID-19 infection is currently unclear and mostly limited to case reports in the literature (19,22,67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72). However, in a prospective cohort study conducted in Germany of 100 patients recently recovered from COVID-19 who underwent cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging at a median time interval of 71 days since infection, CMR revealed cardiac involvement in nearly 80% of patients and ongoing myocardial inflammation in 60%. CMR abnormalities included low left ventricular ejection fraction, greater left ventricular volumes, raised native T1 and T2, late gadolinium enhancement, and pericardial enhancement (73). Of note, these findings correlated with higher levels of high-sensitivity troponin and active lymphocytic inflammation on endomyocardial biopsy specimens. These findings support the need for ongoing investigation and longitudinal follow-up to evaluate the long-term cardiac consequences of COVID-19.

Thromboembolic and Pulmonary Vascular Disease

The most catastrophic consequences of COVID-19 are ARDS and sudden death. Among patients with respiratory failure, profound gas exchange abnormalities with relatively preserved pulmonary mechanics have raised questions about pulmonary vascular involvement. Thromboembolic disease is increasingly recognized as a key contributor to the rapid decline of hospitalized patients with severe COVID-19 (74,75).

Venous and arterial thromboembolism pathogenesis

There are several postulated mechanisms by which thrombotic disease inclusive of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary thromboembolism may occur at increased frequency in the setting of acute COVID-19 (74). These include inflammation, hypoxia, off-target therapeutic effects, and consequences of hospital care. As discussed previously, excessive inflammation, endothelial activation, and stasis predispose to both arterial and venous thrombosis. Hypoxia, a defining feature of moderate or severe COVID-19, decreases S protein production and increases risk of thrombosis (76). In addition, the high incidence of supraventricular tachyarrhythmias may contribute to the observed high incidence of arterial thromboembolism despite adequate thromboembolic prophylaxis (77,78). It is speculated that certain investigational or repurposed drugs such as hydroxychloroquine (HCQ), antiretroviral therapies, and immunomodulatory biologics alter thrombotic risk and may produce adverse drug–drug interactions (74). Bevacizumab is an investigational monoclonal antibody that binds to vascular endothelial growth factor and is being used to treat COVID-19. The use of bevacizumab is associated with increased risk of thrombotic events, including MI, DVT, and stroke (79). Conversely, even though HCQ may increase arrhythmic risk, its use may have some beneficial antithrombotic properties, particularly against antiphospholipid antibodies (80). Due to limited resources, dispersed staffing, and social distancing policies, patients may receive varying levels of care and treatment while in the hospital. Routine prophylaxis for thromboembolism prevention may not be uniform, for example, in attempts to avoid risk of exposure.

Incidence and association with outcomes

The true incidence of thromboembolic disease is unknown. Collections of case reports and small case series support that thrombotic complications of COVID-19 are common (81, 82, 83, 84, 85). Among 184 intensive care unit patients with COVID-19 in the Netherlands, the cumulative incidence of acute pulmonary embolism, DVT, ischemic stroke, MI, or systemic arterial embolism was 31% (95% CI: 20% to 41%), and pulmonary embolism was the most frequent thrombotic complication (n = 25) (83). Among patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China, there was a similar 25% incidence of VTE among 81 intensive care unit patients, 8 of whom died (84). Finally, in a propensity-matched comparison between 150 patients with COVID-19 ARDS and 145 non–COVID-19 ARDS patients, those with COVID-19 had more thromboembolic events, in particular more pulmonary thromboembolism (11.7% vs. 2.1%; p < 0.008) (85). All these reports showed an association between elevated inflammatory markers, especially D-dimer and fibrinogen, with thromboembolic disease and higher mortality.

Reports describing arterial thromboembolic events in patients with COVID-19 are limited to small case series at the present time. In a retrospective single-center study from Wuhan, China, the incidence of acute cerebrovascular events among hospitalized patients with COVID-19 and severe infection was ∼5% (86). Interestingly, Oxley et al. (87) recently reported a case series from New York City of 5 young patients presenting with large-vessel occlusion ischemic stroke and positive for COVID-19 infection over a 2-week period. In comparison, the same institution treated every 2 weeks over the previous 12 months, on average, 0.73 patients <50 years of age with large-vessel stroke. Similar trends have been observed also in terms of acute limb ischemia. In a single-center case series, 20 patients hospitalized for COVID-19 developed acute limb ischemia over a 3-month period (88). This represented a significant increase in limb ischemia over the previous year (16% vs. 2% in early 2019).

Management

Prevention and management of thromboembolic disease in patients with COVID-19 consists of prophylaxis and systemic anticoagulation, respectively. A summary of the recommendations endorsed by the National Institutes of Health is reported in Table 2 (89). Heparin and low-molecular-weight heparin have theoretical benefits over vitamin K antagonists and direct oral anticoagulants (90, 91, 92, 93). Heparin possesses specific anti-inflammatory properties being able to down-regulate IL-6. Their use may be particularly helpful in the context of COVID-19 because they bind the S protein of SARS-CoV-2, but in the absence of direct comparisons between low-molecular-weight heparin and oral anticoagulants, their superiority cannot be confirmed (92,93). Animal models of ARDS have identified fibrin deposition in the pulmonary vasculature, leading some to explore treating patients with thrombolytic therapy (94,95). Small cases series of tissue plasminogen activator use in severe COVID-19 describe initial but nonsustained improvement in partial arterial pressure of oxygen/fraction of inspired oxygen ratios (96). Use of tissue plasminogen activator at our institution resulted in improved oxygenation, ventilation, and shock in 4 patients 55 to 65 years of age with refractory respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation and shock, who exhibited evidence of elevated dead-space ventilation (97). This suggests that pulmonary microvascular and macrovascular thrombi may drive the pathophysiology of certain ARDS phenotypes of COVID-19 (97,98).

Table 2.

Key Recommendations for Antithrombotic Therapies in Hospitalized Patients With COVID-19 From the National Institutes of Health (89)

| Laboratory testing |

| In hospitalized patients with COVID-19, hematologic and coagulation parameters are commonly measured, although there are currently insufficient data to recommend for or against using these data to guide management decisions |

| Chronic anticoagulant and antiplatelet therapies |

| Patients who are receiving anticoagulant or antiplatelet therapies for underlying conditions should continue these medications if they receive a diagnosis of COVID-19 |

| VTE prophylaxis and screening |

| Hospitalized adults with COVID-19 should receive VTE prophylaxis per the standard of care for other hospitalized adults |

| Anticoagulant or antiplatelet therapy should not be used to prevent arterial thrombosis outside of the usual standard of care for patients without COVID-19 |

| There are currently insufficient data to recommend for or against the use of thrombolytic agents or increasing anticoagulant doses for VTE prophylaxis in hospitalized COVID-19 patients outside the setting of a clinical trial |

| Hospitalized patients with COVID-19 should not routinely be discharged on VTE prophylaxis. Extended VTE prophylaxis can be considered in patients who are at low risk for bleeding and high risk for VTE |

| There are currently insufficient data to recommend for or against routine deep vein thrombosis screening in COVID-19 patients without signs or symptoms of VTE, regardless of the status of their coagulation markers |

| Treatment |

| Patients with COVID-19 who experience an incident thromboembolic event or who are highly suspected to have thromboembolic disease at a time when imaging is not possible should be managed with therapeutic doses of anticoagulant therapy as per the standard of care for patients without COVID-19 |

| Patients with COVID-19 who require extracorporeal membrane oxygenation or continuous renal replacement therapy or who have thrombosis of catheters or extracorporeal filters should be treated with antithrombotic therapy per the standard institutional protocols for those without COVID-19 |

COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019; VTE = venous thromboembolism.

Arrhythmic Manifestations of COVID-19

Arrhythmias are a common manifestation of CVD in patients with COVID-19. In a clinical case series of hospitalized patients in China, palpitations were an initial presenting symptom in 7.3%, and cardiac arrhythmias were reported in 16.7%, including 44.4% of intensive care unit patients (9). A study of 323 hospitalized patients reported arrhythmias to be present in 30.3% of the full cohort, and they were largely ubiquitous (96.2%) in the critically ill subgroup (99). Although most of these studies have been limited by a lack of specificity as to what constitutes “arrhythmias,” one single-center study of 187 patients identified malignant arrhythmias in 5.9% of hospitalized COVID-19 patients, with “malignant arrhythmias” being defined as rapid ventricular tachycardia lasting >30 s, inducing hemodynamic instability, or ventricular fibrillation (3).

Mechanisms underlying arrhythmias

There are several mechanisms by which arrhythmias may occur in COVID-19. First, as discussed earlier, between 19.7% and 27.8% of patients sustain myocardial injury (3,4). Once myocardial injury occurs, the incidence of arrhythmias increases substantially. Malignant arrhythmias occurred in 1.5% and 17.3% of patients without or with myocardial injury, respectively. Parenthetically, a related mechanism for cardiac arrhythmias is secondary to coronary syndromes leading to MI (64).

A second mechanism for arrhythmias in COVID-19 is electrical instability attendant with QT prolongation. This is of particular concern because infected individuals: 1) may develop hypokalemia or hypomagnesemia from either the disease itself (e.g., diarrhea), particularly in the critically ill, or with certain treatments, such as diuretic agents; and 2) several pharmacotherapies being repurposed to treat COVID-19 carry an inherent risk for QT prolongation and torsades de pointes. For the latter, agents that inhibit the human ether-a-go-go related gene (hERG)-K+ channel include both the antimalarial drugs chloroquine and HCQ, which have been shown in vitro to block infection by increasing the endosomal pH required for SARS-CoV-2 virus fusion to cells, and the protease inhibitors lopinavir and ritonavir, which interfere with viral RNA replication. Despite few data supporting HCQ (100), considerable interest has been garnered, often with concomitant use of the macrolide antibiotic azithromycin, which can also prolong the QT interval but via an hERG-independent mechanism. However, the efficacy of HCQ in the treatment of hospitalized patients with COVID-19 has recently been questioned by the preliminary results of the RECOVERY (Randomised Evaluation of COVID-19 Therapy; NCT04381936) trial, in which 1,542 patients were randomized to receive HCQ and compared with 3,132 patients randomized to usual care alone. There was no significant difference in the primary endpoint of 28-day mortality (25.7% HCQ vs. 23.5% usual care; hazard ratio: 1.11; 95% CI: 0.98 to 1.26; p = 0.10). Also, there was no evidence of beneficial effects with HCQ on hospital stay duration or other outcomes. Therefore, the use of HCQ in patients with COVID-19 is at the present not supported by any randomized controlled trial evidence.

The hyperinflammatory state characteristic of COVID-19 also promotes arrhythmias by direct electrophysiological effects of the cytokines on the myocardium (8). Inflammatory cytokines known to be up-regulated in COVID-19 prolong ventricular action potential duration by modulating the expression/activity of the cardiomyocyte K+ and Ca++ ion channels. Indeed, IL-6 inhibits hERG and prolongs ventricular action potential duration (101). Beyond these direct cardiac effects, inflammatory cytokines can provoke cardiac sympathetic system hyperactivation both centrally (an inflammatory reflex mediated by the hypothalamus) and peripherally (by activating the left stellate ganglia), in turn triggering life-threatening arrhythmias in the setting of long QT. Also, IL-6 inhibits cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4, thereby increasing the bioavailability of several QT-prolonging medications. Combined with the fact that HCQ and ritonavir directly inhibit CYP2D6 and CYP3A4, respectively, there is a potential for QT prolongation culminating in torsades de pointes (102).

Finally, rapidly worsening renal function and electrolyte abnormalities, which are often observed in patients with severe COVID-19 infection, may contribute to the genesis or deterioration of cardiac arrhythmias (103,104).

Specific arrhythmias

Sinus tachycardia is common in COVID-19 but seems to simply reflect the acutely ill nature of these patients, rather than a specific effect on the sinus node. Similarly, bradyarrhythmias specific to COVID-19 have not been described. Our group has seen instances of atrioventricular block but in the setting of acute MI. With regard to “malignant arrhythmias,” there are few published details. Certainly, for patients with a history of myocardial scar who subsequently become infected with SARS-CoV-2, it would not be surprising for monomorphic ventricular tachycardia to occur secondary to the hyperadrenergic state of COVID-19. In the absence of a pre-existing scar, whether any such ventricular tachyarrhythmias are primary arrhythmic events amenable to intervention (e.g., antiarrhythmic medication or defibrillation) or simply terminal events in the context of severe metabolic/hemodynamic/hypoxic derangements is unknown (although our preliminary observations point to the latter). Finally, although not studied in any detail, we have observed atrial fibrillation and flutter in COVID-19, sometimes as a new-onset arrhythmia. The frequency and implication of atrial fibrillation in the prothrombotic environment of COVID-19 remain to be elucidated.

Perspective

As COVID-19 cases continue to increase, our understanding of the cardiovascular manifestations has evolved. Elderly patients with pre-existing CVD are particularly susceptible to experiencing severe COVID-19, type 2 MI, and death. What is less certain is why younger patients, including those without previously known CVD, experience type 2 MI with similar cardiovascular outcomes. Direct viral transmission and mutations enhancing infectivity certainly contribute to increased numbers of infected individuals, but the differentiator between severe disease and mild or asymptomatic infection likely lies with each individual’s immune response. Low levels of innate immunity, characterized by weak interferon production, coupled with robust cytokine production (e.g., IL-6, IL-1) lead to viral persistence and systemic inflammation (105). This is particularly true for elderly persons, the immunosuppressed, and a few younger individuals. We speculate that this impaired innate immune response becomes the missing link between infection, inflammation, thrombosis, and myocardial injury.

Conclusions

The cardiovascular system is broadly injured by SARS-CoV-2 infection. A summary of the mechanisms of myocardial injury discussed in the present paper are broadly summarized in the Central Illustration. Myocardial injury results in detectable increases in serum troponin, varying degrees of ventricular dysfunction, and relatively frequent cardiac arrhythmias. Whether these effects are simply associated with poor patient outcomes, including death, or directly contribute to patient mortality is as yet uncertain. The lingering impact that endothelial activation, hypercoagulability, microvascular thrombosis, and myocardial injury will have on long-term patient functional status and quality of life are similarly unknown and warrant further research on longitudinal follow-up studies.

Footnotes

Dr. Giustino has received consulting fees from Bristol Myers Squibb and Pfizer. Dr. Pinney has received consulting fees from Abbott, CareDx, Medtronic, and Procyrion. Dr. Lala has received speaker honoraria from Zoll, Inc. Dr. Reddy has served as a consultant for Abbott, Ablacon, Acutus Medical, Affera, Apama Medical, Aquaheart, Autonomix, Axon, Backbeat, BioSig, Biosense-Webster, Biotronik, Boston Scientific, Cardiofocus, Cardionomic, CardioNXT/AFTx, Circa Scientific, Corvia Medical, Dinova Nuomao, East End Medical, EBR, EPD, Epix Therapeutics, EpiEP, Eximo, Farapulse, Fire1, Impulse Dynamics, Javelin, Keystone Heart, LuxCath, Medlumics, Medtronic, Middlepeak, Nuvera, Philips, Stimda, Thermedical, Valcare, and VytronUS; and has equity in Ablacon, Acutus Medical, Affera, Apama Medical, Aquaheart, Autonomix, Backbeat, BioSig, Circa Scientific, Corvia Medical, Dinova Nuomao, East End Medical, EPD, Epix Therapeutics, EpiEP, Eximo, Farapulse, Fire1, Javelin, Keystone Heart, LuxCath, Manual Surgical Sciences, Medlumics, Middlepeak, Newpace, Nuvera, Surecor, Valcare, Vizara, and VytronUS (none relevant to the current paper). Dr. Mechanick has received honoraria for lectures and program development from Abbott Nutrition. Dr. Halperin has received consulting fees from Bayer AG HealthCare, Boehringer Ingelheim, Johnson & Johnson, and Ortho-McNeil-Janssen Pharmaceuticals; and has served as a member of the Executive Steering Committee for the MARINER trial comparing anticoagulant strategies. All other authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose. Muthiah Vaduganathan, MD, served as Guest Associate Editor for this paper. Deepak L. Bhatt, MD, MPH, served as Guest Editor-in-Chief for this paper.

The authors attest they are in compliance with human studies committees and animal welfare regulations of the authors’ institutions and Food and Drug Administration guidelines, including patient consent where appropriate. For more information, visit the JACCauthor instructions page.

References

- 1.GBD 2017 Causes of Death Collaborators Global, regional, and national age-sex-specific mortality for 282 causes of death in 195 countries and territories, 1980-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392:1736–1788. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32203-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fauci A.S., Lane H.C., Redfield R.R. Covid-19—navigating the uncharted. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1268–1269. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe2002387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guo T., Fan Y., Chen M. Cardiovascular implications of fatal outcomes of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) JAMA Cardiol. 2020;27:1–8. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shi S., Qin M., Shen B. Association of cardiac injury with mortality in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;25:802–810. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.0950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhou F., Yu T., Du R. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen T., Wu D., Chen H. Clinical characteristics of 113 deceased patients with coronavirus disease 2019: retrospective study. BMJ. 2020;368:m1091. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smeeth L., Thomas S.L., Hall A.J., Hubbard R., Farrington P., Vallance P. Risk of myocardial infarction and stroke after acute infection or vaccination. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2611–2618. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang D., Hu B., Hu C. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323:1061–1069. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lala A., Johnson K.W., Januzzi J.L. Prevalence and impact of myocardial injury in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 infection. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76:533–546. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Richardson S., Hirsch J.S., Narasimhan M. Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the New York City area. JAMA. 2020;323:2052–2059. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bavishi C., Bonow R.O., Trivedi V., Abbott J.D., Messerli F.H., Bhatt D.L. Acute myocardial injury in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 infection: a review. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2020 Jun 6 doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2020.05.013. [E-pub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gheblawi M., Wang K., Viveiros A. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2: SARS-CoV-2 receptor and regulator of the renin-angiotensin system: celebrating the 20th anniversary of the discovery of ACE2. Circ Res. 2020;126:1456–1474. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.120.317015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Millet J.K., Whittaker G.R. Host cell proteases: critical determinants of coronavirus tropism and pathogenesis. Virus Res. 2015;202:120–134. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2014.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu P.P., Blet A., Smyth D., Li H. The science underlying COVID-19: implications for the cardiovascular system. Circulation. 2020;142:68–78. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.047549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oudit G.Y., Kassiri Z., Jiang C. SARS-coronavirus modulation of myocardial ACE2 expression and inflammation in patients with SARS. Eur J Clin Invest. 2009;39:618–625. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2009.02153.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim I.C., Kim J.Y., Kim H.A., Han S. COVID-19-related myocarditis in a 21-year-old female patient. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:1859. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meyer P., Degrauwe S., Van Delden C., Ghadri J.R., Templin C. Typical takotsubo syndrome triggered by SARS-CoV-2 infection. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:1860. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Inciardi R.M., Lupi L., Zaccone G. Cardiac involvement in a patient with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5:1–6. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tavazzi G., Pellegrini C., Maurelli M. Myocardial localization of coronavirus in COVID-19 cardiogenic shock. Eur J Heart Fail. 2020;22:911–915. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Escher F., Pietsch H., Aleshcheva G. Detection of viral SARS-CoV-2 genomes and histopathological changes in endomyocardial biopsies. ESC Heart Fail. 2020 Jun 12 doi: 10.1002/ehf2.12805. [E-pub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wenzel P., Kopp S., Gobel S. Evidence of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA in endomyocardial biopsies of patients with clinically suspected myocarditis tested negative for COVID-19 in nasopharyngeal swab. Cardiovasc Res. 2020;116:1661–1663. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvaa160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lindner D., Fitzek A., Brauninger H. Association of cardiac infection with SARS-CoV-2 in confirmed COVID-19 autopsy cases. JAMA Cardiol. 2020 Jul 27 doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.3551. [E-pub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scott A.J., O’Dea K.P., O’Callaghan D. Reactive oxygen species and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase mediate tumor necrosis factor alpha-converting enzyme (TACE/ADAM-17) activation in primary human monocytes. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:35466–35476. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.277434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patel V.B., Clarke N., Wang Z. Angiotensin II induced proteolytic cleavage of myocardial ACE2 is mediated by TACE/ADAM-17: a positive feedback mechanism in the RAS. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2014;66:167–176. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2013.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reynolds H.R., Adhikari S., Pulgarin C. Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors and risk of Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2441–2448. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2008975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mancia G., Rea F., Ludergnani M., Apolone G., Corrao G. Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system blockers and the risk of Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2431–2440. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2006923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Amat-Santos I.J., Santos-Martinez S., Lopez-Otero D. Ramipril in high-risk patients with COVID-19. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76:268–276. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.05.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hamming I., Cooper M.E., Haagmans B.L. The emerging role of ACE2 in physiology and disease. J Pathol. 2007;212:1–11. doi: 10.1002/path.2162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boisrame-Helms J., Kremer H., Schini-Kerth V., Meziani F. Endothelial dysfunction in sepsis. Curr Vasc Pharmacol. 2013;11:150–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Escher R., Breakey N., Lammle B. Severe COVID-19 infection associated with endothelial activation. Thromb Res. 2020;190:62. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zachariah U., Nair S.C., Goel A. Targeting raised von Willebrand factor levels and macrophage activation in severe COVID-19: consider low volume plasma exchange and low dose steroid. Thromb Res. 2020;192:2. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Varga Z., Flammer A.J., Steiger P. Endothelial cell infection and endotheliitis in COVID-19. Lancet. 2020;395:1417–1418. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30937-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thygesen K., Alpert J.S., Jaffe A.S. Fourth universal definition of myocardial infarction (2018) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:2231–2264. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.08.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Libby P., Loscalzo J., Ridker P.M. Inflammation, immunity, and infection in atherothrombosis: JACC Review Topic of the Week. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:2071–2081. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.08.1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mogensen T.H. Pathogen recognition and inflammatory signaling in innate immune defenses. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2009;22:240–273. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00046-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van de Veerdonk F.L., Netea M.G., Dinarello C.A., Joosten L.A. Inflammasome activation and IL-1beta and IL-18 processing during infection. Trends Immunol. 2011;32:110–116. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vallance P., Collier J., Bhagat K. Infection, inflammation, and infarction: does acute endothelial dysfunction provide a link? Lancet. 1997;349:1391–1392. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)09424-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Welt FGP, Shah P.B., Aronow H.D. Catheterization laboratory considerations during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic: from the ACC’s Interventional Council and SCAI. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:2372–2375. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mahmud E., Dauerman H.L., Welt F.G. Management of acute myocardial infarction during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020 Apr 21 doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.039. [E-pub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Szerlip M., Anwaruddin S., Aronow H.D. Considerations for cardiac catheterization laboratory procedures during the COVID-19 pandemic perspectives from the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions Emerging Leader Mentorship (SCAI ELM) Members and Graduates. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2020 Mar 25 doi: 10.1002/ccd.28887. [E-pub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lim W., Qushmaq I., Devereaux P.J. Elevated cardiac troponin measurements in critically ill patients. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:2446–2454. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.22.2446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sarkisian L., Saaby L., Poulsen T.S. Prognostic impact of myocardial injury related to various cardiac and noncardiac conditions. Am J Med. 2016;129:506–514.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sarkisian L., Saaby L., Poulsen T.S. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients with myocardial infarction, myocardial injury, and nonelevated troponins. Am J Med. 2016;129:446.e5–446.e21. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Harrington R.A. Targeting inflammation in coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1197–1198. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1709904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kwong J.C., Schwartz K.L., Campitelli M.A. Acute myocardial infarction after laboratory-confirmed influenza infection. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:345–353. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1702090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ebinger J.E., Shah P.K. Declining admissions for acute cardiovascular illness: the Covid-19 paradox. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76:289–291. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.05.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Metzler B., Siostrzonek P., Binder R.K., Bauer A., Reinstadler S.J. Decline of acute coronary syndrome admissions in Austria since the outbreak of COVID-19: the pandemic response causes cardiac collateral damage. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:1852–1853. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.De Rosa S., Spaccarotella C., Basso C. Reduction of hospitalizations for myocardial infarction in Italy in the COVID-19 era. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:2083–2088. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pessoa-Amorim G., Camm C.F., Gajendragadkar P. Admission of patients with STEMI since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. A survey by the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes. 2020;6:210–216. doi: 10.1093/ehjqcco/qcaa046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bhatt A.S., Moscone A., McElrath E.E. Fewer hospitalizations for acute cardiovascular conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76:280–288. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.05.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Qin C., Zhou L., Hu Z. Dysregulation of immune response in patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:762–768. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kumar A., Thota V., Dee L., Olson J., Uretz E., Parrillo J.E. Tumor necrosis factor alpha and interleukin 1beta are responsible for in vitro myocardial cell depression induced by human septic shock serum. J Exp Med. 1996;183:949–958. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.3.949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pathan N., Hemingway C.A., Alizadeh A.A. Role of interleukin 6 in myocardial dysfunction of meningococcal septic shock. Lancet. 2004;363:203–209. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15326-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Natanson C., Eichenholz P.W., Danner R.L. Endotoxin and tumor necrosis factor challenges in dogs simulate the cardiovascular profile of human septic shock. J Exp Med. 1989;169:823–832. doi: 10.1084/jem.169.3.823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Goldhaber J.I., Kim K.H., Natterson P.D., Lawrence T., Yang P., Weiss J.N. Effects of TNF-alpha on [Ca2+]i and contractility in isolated adult rabbit ventricular myocytes. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:H1449–H1455. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.271.4.H1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hobai I.A., Edgecomb J., LaBarge K., Colucci W.S. Dysregulation of intracellular calcium transporters in animal models of sepsis-induced cardiomyopathy. Shock. 2015;43:3–15. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Krown K.A., Yasui K., Brooker M.J. TNF alpha receptor expression in rat cardiac myocytes: TNF alpha inhibition of L-type Ca2+ current and Ca2+ transients. FEBS Lett. 1995;376:24–30. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)01238-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Varga Z.V., Ferdinandy P., Liaudet L., Pacher P. Drug-induced mitochondrial dysfunction and cardiotoxicity. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2015;309:H1453–H1467. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00554.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shi S., Qin M., Cai Y. Characteristics and clinical significance of myocardial injury in patients with severe coronavirus disease 2019. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:2070–2079. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sud K., Vogel B., Bohra C. Echocardiographic findings in patients with COVID-19 with significant myocardial injury. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2020;33:1054–1055. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2020.05.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mahmoud-Elsayed H.M., Moody W.E., Bradlow W.M. Echocardiographic findings in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. Can J Cardiol. 2020;36:1203–1207. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2020.05.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Szekely Y., Lichter Y., Taieb P. Spectrum of cardiac manifestations in COVID-19: a systematic echocardiographic study. Circulation. 2020;142:342–353. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.047971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bangalore S., Sharma A., Slotwiner A. ST-segment elevation in patients with Covid-19—a case series. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2478–2480. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2009020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Stefanini G.G., Montorfano M., Trabattoni D. ST-elevation myocardial infarction in patients with COVID-19: clinical and angiographic outcomes. Circulation. 2020;141:2113–2116. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.047525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Giustino G., Croft L.B., Oates C.P. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy in males with Covid-19. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76:628–629. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.05.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fried J.A., Ramasubbu K., Bhatt R. The variety of cardiovascular presentations of COVID-19. Circulation. 2020;141:1930–1936. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.047164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kesici S., Aykan H.H., Orhan D., Bayrakci B. Fulminant COVID-19-related myocarditis in an infant. Eur Heart J. 2020 doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Besler M.S., Arslan H. Acute myocarditis associated with COVID-19 infection. Am J Emerg Med. 2020 Jun 2 doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2020.05.100. [E-pub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sardari A., Tabarsi P., Borhany H., Mohiaddin R., Houshmand G. Myocarditis detected after COVID-19 recovery. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020 May 27 doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jeaa166. [E-pub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Luetkens J.A., Isaak A., Zimmer S. Diffuse myocardial inflammation in COVID-19 associated myocarditis detected by multiparametric cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020;13 doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.120.010897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Irabien-Ortiz A., Carreras-Mora J., Sionis A., Pamies J., Montiel J., Tauron M. Fulminant myocarditis due to COVID-19. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed) 2020;73:503–504. doi: 10.1016/j.rec.2020.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Puntmann V.O., Carerj M.L., Wieters I. Outcomes of cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging in patients recently recovered from coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) JAMA Cardiol. 2020 Jul 27 doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.3557. [E-pub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bikdeli B., Madhavan M.V., Jimenez D. COVID-19 and thrombotic or thromboembolic disease: implications for prevention, antithrombotic therapy, and follow-up: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:2950–2973. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kollias A., Kyriakoulis K.G., Dimakakos E., Poulakou G., Stergiou G.S., Syrigos K. Thromboembolic risk and anticoagulant therapy in COVID-19 patients: emerging evidence and call for action. Br J Haematol. 2020;189:846–847. doi: 10.1111/bjh.16727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Pilli V.S., Datta A., Afreen S., Catalano D., Szabo G., Majumder R. Hypoxia downregulates protein S expression. Blood. 2018;132:452–455. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-04-841585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kashi M., Jacquin A., Dakhil B. Severe arterial thrombosis associated with Covid-19 infection. Thromb Res. 2020;192:75–77. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.05.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lodigiani C., Iapichino G., Carenzo L. Venous and arterial thromboembolic complications in COVID-19 patients admitted to an academic hospital in Milan, Italy. Thromb Res. 2020;191:9–14. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Totzeck M., Mincu R.I., Rassaf T. Cardiovascular adverse events in patients with cancer treated with bevacizumab: a meta-analysis of more than 20 000 patients. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.117.006278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Olsen N.J., Schleich M.A., Karp D.R. Multifaceted effects of hydroxychloroquine in human disease. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2013;43:264–272. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2013.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Danzi G.B., Loffi M., Galeazzi G., Gherbesi E. Acute pulmonary embolism and COVID-19 pneumonia: a random association? Eur Heart J. 2020;41:1858. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Casey K., Iteen A., Nicolini R., Auten J. COVID-19 pneumonia with hemoptysis: acute segmental pulmonary emboli associated with novel coronavirus infection. Am J Emerg Med. 2020;38:1544.e1–1544.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2020.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Klok F.A., Kruip M., van der Meer N.J.M. Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19. Thromb Res. 2020;191:145–147. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Cui S., Chen S., Li X., Liu S., Wang F. Prevalence of venous thromboembolism in patients with severe novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18:1421–1424. doi: 10.1111/jth.14830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Helms J., Tacquard C., Severac F. High risk of thrombosis in patients with severe SARS-CoV-2 infection: a multicenter prospective cohort study. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:1089–1098. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06062-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Mao L., Jin H., Wang M. Neurologic manifestations of hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77:1–9. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Oxley T.J., Mocco J., Majidi S. Large-vessel stroke as a presenting feature of covid-19 in the young. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:e60. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2009787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Bellosta R., Luzzani L., Natalini G. Acute limb ischemia in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. J Vasc Surg. 2020 Apr 29 doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2020.04.483. [E-pub ahad of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines Panel Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Treatment Guidelines. National Institutes of Health. https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/ Available at: [PubMed]

- 90.Young E. The anti-inflammatory effects of heparin and related compounds. Thromb Res. 2008;122:743–752. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2006.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mummery R.S., Rider C.C. Characterization of the heparin-binding properties of IL-6. J Immunol. 2000;165:5671–5679. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.10.5671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.de Haan C.A., Li Z., te Lintelo E., Bosch B.J., Haijema B.J., Rottier P.J. Murine coronavirus with an extended host range uses heparan sulfate as an entry receptor. J Virol. 2005;79:14451–14456. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.22.14451-14456.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Belouzard S., Chu V.C., Whittaker G.R. Activation of the SARS coronavirus spike protein via sequential proteolytic cleavage at two distinct sites. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:5871–5876. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809524106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hardaway R.M., Williams C.H., Marvasti M. Prevention of adult respiratory distress syndrome with plasminogen activator in pigs. Crit Care Med. 1990;18:1413–1418. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199012000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Stringer K.A., Hybertson B.M., Cho O.J., Cohen Z., Repine J.E. Tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) inhibits interleukin-1 induced acute lung leak. Free Radic Biol Med. 1998;25:184–188. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(98)00047-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Wang J., Hajizadeh N., Moore E.E. Tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) treatment for COVID-19 associated acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS): a case series. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18:1752–1755. doi: 10.1111/jth.14828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Poor H.D., Ventetuolo C.E., Tolbert T. COVID-19 critical illness pathophysiology driven by diffuse pulmonary thrombi and pulmonary endothelial dysfunction responsive to thrombolysis. Clin Transl Med. 2020 Apr 21 doi: 10.1002/ctm2.44. [E-pub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ackermann M., Verleden S.E., Kuehnel M. Pulmonary vascular endothelialitis, thrombosis, and angiogenesis in Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:120–128. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2015432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hu L., Chen S., Fu Y. Risk factors associated with clinical outcomes in 323 COVID-19 hospitalized patients in Wuhan, China. Clin Infect Dis. 2020 May 3 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa539. [E-pub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Gautret P., Lagier J.C., Parola P. Hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin as a treatment of COVID-19: results of an open-label non-randomized clinical trial. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020;56:105949. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 101.Lazzerini P.E., Laghi-Pasini F., Boutjdir M., Capecchi P.L. Cardioimmunology of arrhythmias: the role of autoimmune and inflammatory cardiac channelopathies. Nat Rev Immunol. 2019;19:63–64. doi: 10.1038/s41577-018-0098-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Lazzerini P.E., Boutjdir M., Capecchi P.L. COVID-19, arrhythmic risk and inflammation: mind the gap! Circulation. 2020;142:7–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.047293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Hirsch J.S., Ng J.H., Ross D.W. Acute kidney injury in patients hospitalized with COVID-19. Kidney Int. 2020;98:209–218. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Batlle D., Soler M.J., Sparks M.A. Acute kidney injury in COVID-19: emerging evidence of a distinct pathophysiology. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;31:1380–1383. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2020040419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Blanco-Melo D., Nillson-Payant B.E., Liu W.-C. Imbalanced host response to SARS-CoV-2 drives development of COVID-19. Cell. 2020;181:1036–1045. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.04.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]