Abstract

Background

In June 2018, San Francisco voters upheld the first comprehensive prohibition on sales of flavoured tobacco products (all products including menthol, everywhere in the city with no exceptions).

Methods

This paper used data collected by the San Francisco Department of Public Health as part of its implementation and enforcement of San Francisco’s city-wide ban on the sale of flavoured tobacco products. Every licensed tobacco retailer was visited and inspected. The San Francisco Department of Public Health and volunteers conducted an educational campaign from September 2018 to December 2018, including emailing all licensed tobacco retailers about the law, mailing a fact sheet poster, conducting four listening sessions and visiting permitted tobacco retailers to educate them about the law and solicit questions.

Results

Compliance inspections started in December 2018, which found that compliance was 17%. Compliance increased in January 2019 and averaged 80% between January 2019 and December 2019. After the phase-in period, all retailers were visited as part of routine inspections. This effort resulted in 80% compliance.

Conclusion

Including retailer education prior to enforcement can result in compliance with a comprehensive ban on the sale of menthol and other flavoured tobacco products.

INTRODUCTION

Eighty per cent of youth and young adults initiate tobacco use with a flavoured product.1 While the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act (FSPTCA) granted the Food and Drug Administration2 (FDA) authority to prohibit the use of characterising flavours in all tobacco products in 2009, the FDA has not moved beyond the prohibition on characterising flavours in cigarettes and smokeless tobacco included in the Act. While only the FDA can regulate the products themselves, the FSPTCA allows local regulation of the sale of tobacco products. In response to concerns over the appeal of flavoured tobacco products, several cities and counties enacted restrictions on the sale of flavoured tobacco products, often making exceptions for menthol flavoured products, allowing sales in ‘adult only’ stores, or imposing geographical restrictions, such as not allowing sales of flavoured tobacco products near schools.3

In Massachusetts jurisdictions that implemented partial flavour bans excluding menthol and adult-only establishments (bars, vape shops and tobacconists) between July 2015 and March 2017, the availability of banned products fell by 27% to 86%, depending on the city.4–6 In New York City, which exempted menthol, after initial opposition (including an unsuccessful lawsuit),7 sales of banned flavoured tobacco products declined by 87% following enforcement in November 2010, and averaging 95% compliance between November 2010 and February 2015.7,8 (The New York law excluded e-cigarettes, which were not defined as tobacco products under New York City law and exempted eight existing tobacco bars (bars that generated at least 10% of their income from on-site tobacco sales and the rental of on-site humidors).) In Minneapolis and St. Paul, the number of convenience and grocery stores that sold flavoured tobacco dropped substantially following the implementation of each city’s policy to restrict flavoured tobacco product sales, excluding menthol, to adult-only tobacco stores.9 In July 2016, Chicago, Illinois, became the first major US city to ban menthol cigarette sales within 500 feet of schools, but only 57% of stores were compliant as of in June 2017, 1 year later.10 Implementation of flavoured tobacco product sales restrictions in Massachusetts and New York City were followed by significant reductions in youth use of both flavoured and non-flavoured tobacco.5,8 Flavoured tobacco sales restrictions also were followed by statistically significant reductions in all tobacco use by youth in Providence, Rhode Island.11

While smoking rates declined among adolescents and young adults from 2004 to 2010, declines did not occur among menthol cigarette users.12 Among all racial and ethnic groups, menthol use is highest among African-Americans. 12 Prohibiting sales of flavoured tobacco may mitigate these disparities, but most early flavour restrictions exempted menthol. In Ontario, Canada, 1 year after a ban on sales of menthol cigarettes, 63% of daily menthol users and 62% of occasional menthol users made quit attempts, significantly more than non-menthol users.13 Adjusting for socio-demographics and cigarettes/day, the odds of making a quit attempt (adjusted OR (AOR) 1.25, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.50) and successful quitting (AOR 1.62, 95% CI 1.08 to 2.42) among daily menthol users increased significantly compared with non-menthol users.13

In June 2017 the San Francisco Board of Supervisors unanimously passed the first law prohibiting sales of menthol and other flavoured tobacco products anywhere in the city.14 The idea of including menthol grew out of efforts by the African-American Tobacco Control Leadership Council.14

The law prohibits the sale of any flavoured ‘tobacco product’, with ‘tobacco product’ defined as:

(1) any product containing, made or derived from tobacco or nicotine that is intended for human consumption, whether smoked, heated, chewed, absorbed, dissolved, inhaled, snorted or sniffed or ingested by any other means, including but not limited to, cigarettes, cigars, little cigars, chewing tobacco, pipe tobacco, bidis or snuff; (2) any device or component, part or accessory that delivers nicotine alone or combined with other substances to the person using the device, including but not limited to electronic cigarettes, cigars or pipes, whether or not the device or component is sold separately.

The law had an effective date of April 2018 to allow retailers time to sell existing inventory. However, the same day the mayor signed the law, RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company forced a referendum on the law, which suspended implementation. Despite a US$12 million campaign to repeal the law by RJ Reynolds (manufacturer of the leading menthol cigarette, Newport) and other tobacco companies, 68% of voters upheld the law in June 2018,14 indicating that the public was widely in favour of the flavour ban. (The health groups spent US$5 million defending the law.)15

The San Francisco Department of Public Health (SFDPH) began formal enforcement in April 2019 to allow time to issue the implementing regulations and educate retailers. During compliance inspections retailers were warned of the consequences of selling flavoured tobacco products, which included fines or having their license suspended. This paper summarises the implementation and enforcement efforts after the law went into effect and documents that compliance reached 80%.

METHODS

This paper used data collected by the SFDPH as part of its implementation and enforcement of San Francisco’s city-wide ban on the sale of flavoured tobacco products to describe the implementation programme and enforcement results. Every state licensed and San Francisco permitted tobacco retailer was visited and inspected.

Description of the program

The SFDPH Community Health Equity and Promotion Branch collaborates with the Environmental Health Branch to address tobacco-related issues. SFDPH, with input from the San Francisco Office of Economic and Workforce Development, created a website and developed an educational poster that was mailed to all retailers soon after voters upheld the law. In September 2018 to December 2018, in collaboration with volunteers from the San Francisco Tobacco-Free Coalition, SFDPH implemented an outreach programme to educate retailers and address questions and concerns about the law. Funding for the outreach programme and compliance inspections were part of the SFDPH budgeted tobacco control funds.

Between September 2018 and December 2018, SFDPH and San Francisco Tobacco-Free Coalition volunteers visited 672 of the 747 active licensed tobacco retailers to assess awareness of the new law and record questions about the law. The volunteers provided a poster (online supplementary figure S1), which was also mailed to each location; other SFDPH educational materials describing the law and examples of flavoured tobacco products appear in the online supplemental file. (The SFDPH Environmental Health Branch maintains the list of permitted tobacco retail locations.) Volunteers were trained beginning with a PowerPoint presentation (online supplemental file) explaining the law and describing the materials that were being provided to retailers describing the law, followed by practice sessions with SFDPH staff, including how to respond to questions the volunteers did not know how to answer.

Volunteers recorded the name of store, language preference for materials and store address. Volunteers were instructed to read the following standardised questions to the retailer: (1) ‘Do you have any questions or concerns about complying with the new tobacco law, or about the poster provided?’, (2) ‘Sometimes it isn’t clear if a product is a flavoured tobacco product. Do you have any products that you are unsure of?’ and (3) ‘Do you have any additional questions?’ Volunteers took photos of any products whose flavour status was considered uncertain by the retailer. Volunteers were instructed to observe, not ask and record whether they saw any menthol or flavoured products in the store while they were in the store. Information was recorded on an iPad while in the store, and responses were downloaded by SFDPH in order to provide any requested follow-up information.

Examples of products that were ‘questionably flavoured items’ that volunteers photographed included Swisher Sweets (the red foil pack) that has the word ‘Sweets’ in the brand name but did not otherwise identify the product as flavoured and Camel Crush, which retailers did not consider menthol because it did not have the word ‘menthol’ on the blue and black pack and because some retailers were not aware of the way Camel Crush works. (Camel Crush is a cigarette that contains a small blue menthol capsule within the filter. By squeezing the filter before or while smoking the cigarette, the capsule is crushed and releases the menthol into the filter.)

Compliance inspections then were conducted by SFDPH staff starting in December 2018 and serve as an official part of the retailers’ permit files. SFDPH presumes that a tobacco product is flavoured if its labelling, packaging or marketing include descriptive terms such as ‘spicy’ and ‘sweet’ that imply or evoke characterising flavours. For questionable products, inspection staff research the manufacturer’s website in addition to product packages to locate descriptions associated with a characterising flavour. Photos are taken or saved of the product, as well as a screen shot of the manufacturer’s website with the product description. There could be limitations in identifying a flavoured tobacco product based on how manufacturers change the packaging and online description, but, as of January 2020, all known flavoured products SFDPH had encountered mentioned the characterising flavour on the packaging or website description.

The SFDPH conducted in-store compliance inspections for 724 active tobacco licensed retailers between December 2018 and March 2019. Compliance was based on whether the inspector observed flavoured tobacco products in the store or if flavoured products were out of sight but still being sold. Retailers who were not compliant at the time of the inspection had an opportunity to self-certify that they had subsequently stopped sales of flavoured tobacco products by sending a text message to the SFDPH. These self-certifications were used by the SFDPH to prioritise subsequent compliance inspections. No citations were issued during this process.

As of 1 April 2019 routine enforcement started. If SFDPH inspectors observed flavoured tobacco products at routine inspections, they issued a Notice of Correction giving the business owner 72 hours to remove the flavoured products from the premise. If SFDPH returned after the 72 hours and observed flavoured products again, they issued a Notice of Violation and pursued a Tobacco Permit Suspension.

Ten businesses were permanently closed at time of inspection and were not counted in the total visits for compliance checks.

The online supplementary file contains more details on the compliance programme, including copies of frequently asked questions provided to retailers, warning letter and a non-exhaustive list of flavoured tobacco products.

RESULTS

Retailer survey

The most prevalent questions that were collected during the educational visits were related to the compliance deadline (online supplementary table S1), as well as which products the law prohibited (online supplementary table S2).

Compliance

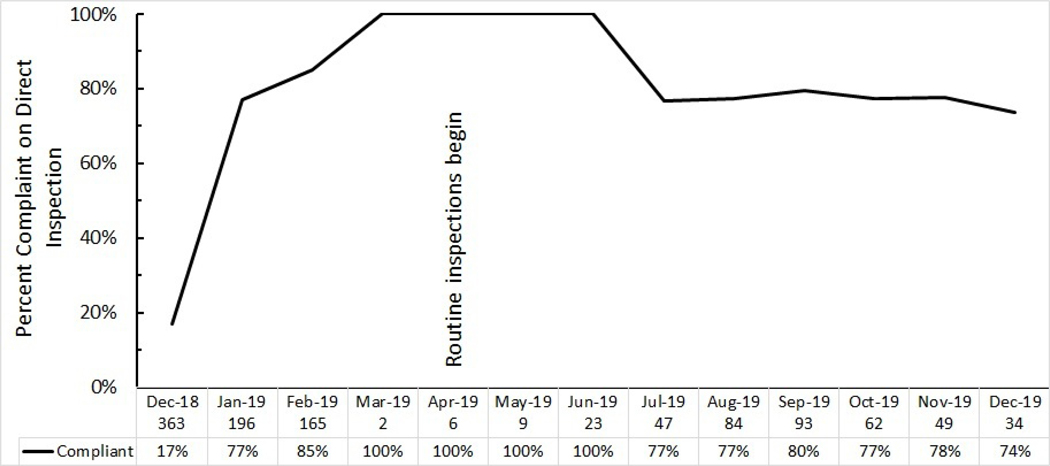

In December 2018, before enforcement started, 17% of stores inspected confirmed no flavoured tobacco (figure 1). Retailers were warned that they would be subject to permit suspension and/or administrative penalties if they did not come into compliance and were offered the opportunity to self-certify compliance by notifying the Department by text message when they had eliminated flavoured tobacco product sales and display. Routine inspections, which included the possibility of citations, started in April 2019. The SFDPH issued 83 Notices of Correction and 4 Notice of Violations between April 2019 and December 2019. Between January 2019 and December 2019, compliance was 80%.

Figure 1.

Retailer compliance to the San Francisco flavoured tobacco sales ban. Compliance was assessed based on in-store inspections. Numbers below the horizontal axis were number of retailers inspected each month by San Francisco Department of Public Health.

DISCUSSION

The 80% compliance observed in San Francisco was comparable or higher than observed in the earlier partial flavour bans.4–10,16After the initial retailer outreach and education phase, monitoring compliance has been included in the Department’s routine annual inspections, so the marginal cost for sustaining the programme is low. Self-certification of compliance by text following initial inspection is low cost and provides documentation to prioritise future inspections. The fact that San Francisco has mandatory tobacco retail licensing facilitated implementation because the Department knew which retailers to visit and the threat of a license suspension may have been a strong motivator for compliance. In January 2020, wholesalers were also covered by the law.

Limitations

Although volunteers were trained in a consistent manner with a PowerPoint and practice sessions, some volunteers probed with open-ended questions more than others, and some retailers were more open to talking than others. During some visits, owners or managers of the store were not present and clerks did not feel comfortable answering questions or language was a barrier. Compliance may be overestimated based on the approach used. Retailers may keep flavoured tobacco products out of sight that inspectors do not find. A strength of the study is that all licensed retailers (as opposed to a sample) were visited to assess compliance with the law.

Conclusion

The San Francisco experience demonstrates that compliance with a comprehensive city-wide prohibition on the sale of all flavoured tobacco products is possible and can be achieved if implemented in a way that is sensitive to the needs of retailers.

This experience can inform other localities and states that may be considering similar policies. An adequate period of in-person retailer education (3 months) followed up with compliance checks and subsequent active enforcement is essential to achieving high compliance. Providing a hard deadline (1 January 2019) was important because only 17% of retailers who received a compliance check prior to 1 January 2019 had stopped selling flavoured tobacco versus 80% of retailers who were inspected after 1 January 2019. The success lies on the fact that retailers received and understood the information in advance of the deadline. The substantial increase in compliance at time of check suggests that this was an adequate amount of time in order for San Francisco retailers to remove the products from their shelves. Other health departments charged with implementing similar laws should provide volunteers and retailers with a hard deadline for when retailers should get flavoured tobacco products off their shelves and prepare a list of frequently asked questionable products to share with volunteers and retailers.

Supplementary Material

What this paper adds.

Several jurisdictions have enacted partial bans on the sale of flavoured tobacco products (often excluding menthol), which has led to a reduced retail availability of banned products.

San Francisco passed the first comprehensive prohibition on the sale of flavoured tobacco products, including menthol, to all retailers without exception.

After a period of retailer education and enforcement, compliance reached 80% on average.

A comprehensive ban on the sale of all flavoured tobacco products can be successfully implemented through a combination of merchant education and systematic enforcement.

Acknowledgements

We thank Janine Young, Uzziel Prado and the SFDPH-EHB Tobacco and Smoking Program for leading the implementation of the educational and enforcement policies described in this paper.

Funding This work was supported in part by National Cancer Institute grant T32CA113710 (PV), Tobacco Related Disease Research Program High Impact Research Award 27IR-0042 (PML), the California Tobacco Control Program, California Department of Public Health (BG, DS, BC), California Department of Justice Grant for the Tobacco and Smoking Program (JC, AD) and National Institute on Drug Abuse grant R01DA043950 (SAG). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies.

Footnotes

Competing interests No, there are no competing interests.

Patient consent for publication Not required.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

REFERENCES

- 1.Truth Initiative. Widespread use of flavored products in young tobacco users, 2019. Available: https://truthinitiative.org/research/widespread-use-flavored-products-young-tobacco-users

- 2.Family smoking prevention and tobacco control act, PUB. L. No. 111–31, 123. Stat. 1776 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids. States & Localities That Have Restricted the Sale of Flavored Tobacco Products, 2020. Available: https://www.tobaccofreekids.org/assets/factsheets/0398.pdf [Accessed 4 Feb 2020].

- 4.Kingsley M, Song G, Robertson J, et al. Impact of flavoured tobacco restriction policies on flavoured product availability in Massachusetts. Tob Control 2020;29:tobaccocontrol-2018–054703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kingsley M, Setodji CM, Pane JD, et al. Short-Term impact of a flavored tobacco restriction: changes in youth tobacco use in a Massachusetts community. Am J Prev Med 2019;57:741–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kephart L, Setodji C, Pane J, et al. Evaluating tobacco retailer experience and compliance with a flavoured tobacco product restriction in Boston, Massachusetts: impact on product availability, advertisement and consumer demand. Tob Control 2019. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2019-055124. [Epub ahead of print: 14 Oct 2019]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown EM, Rogers T, Eggers ME, et al. Implementation of the new York City policy restricting sales of flavored Non-Cigarette tobacco products. Health Educ Behav 2019;46:782–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farley SM, Johns M. New York City flavoured tobacco product sales ban evaluation. Tob Control 2017;26:78–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brock B, Carlson SC, Leizinger A, et al. A tale of two cities: exploring the retail impact of flavoured tobacco restrictions in the twin cities of Minneapolis and Saint Paul, Minnesota. Tob Control 2019;28:176–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Czaplicki L, Cohen JE, Jones MR, et al. Compliance with the city of Chicago’s partial ban on menthol cigarette sales. Tob Control 2019;28:161–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pearlman DN, Arnold JA, Guardino GA, et al. Advancing tobacco control through point of sale policies, Providence, Rhode island. Prev Chronic Dis 2019;16:E129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Giovino GA, Villanti AC, Mowery PD, et al. Differential trends in cigarette smoking in the USA: is menthol slowing progress? Tob Control 2015;24:28–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chaiton MO, Nicolau I, Schwartz R, et al. Ban on menthol-flavoured tobacco products predicts cigarette cessation at 1 year: a population cohort study. Tob Control 2019. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054841. [Epub ahead of print: 30 May 2019]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang YT, Glantz S. San Francisco voters end the sale of flavored tobacco products despite strong industry opposition. Ann Intern Med 2018;169:708–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.City & County of San Francisco Ethics Commission. Campaign finance Dashboards–June 5, 2018 and November 6, 2018 elections, 2018. Available: https://sfethics.org/ethics/2018/03/campaign-finance-dashboards-june-5-2018-and-november-6-2018-elections.html [Accessed 18 Jan 2020].

- 16.Rogers T, Brown EM, McCrae TM, et al. Compliance with a sales policy on flavored Non-cigarette tobacco products. Tob Regul Sci 2017;3:84–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.