Abstract

Uterine rupture is a serious public health concern that causes high maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality in the developing world. Few of the studies conducted in Ethiopia show a high discrepancy in the prevalence of uterine rupture, which ranges between 1.6 and 16.7%. There also lacks a national study on this issue in Ethiopia. This systematic and meta-analysis, therefore, was conducted to assess the prevalence and determinants of uterine rupture in Ethiopia. We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines for systematic review and meta-analysis of studies. All observational published studies were retrieved using relevant search terms in Google scholar, African Journals Online, CINHAL, HINARI, Science Direct, Cochrane Library, EMBASE and PubMed (Medline) databases. Newcastle–Ottawa assessment checklist for observational studies was used for critical appraisal of the included articles. The meta-analysis was done with STATA version 14 software. The I2 test statistics were used to assess heterogeneity among included studies, and publication bias was assessed using Begg's and Egger's tests. Odds ratio (OR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI) was presented using forest plots. A total of twelve studies were included in this study. The pooled prevalence of uterine rupture was 3.98% (95% CI 3.02, 4.95). The highest (7.82%) and lowest (1.53%) prevalence were identified in Amhara and Southern Nations, Nationality and Peoples Region (SNNPR), respectively. Determinants of uterine rupture were urban residence (OR = 0.15 (95% CI 0.09, 0.23)), primipara (OR = 0.12 (95% CI 0.06, 0.27)), previous cesarean section (OR = 3.23 (95% CI 2.12, 4.92)), obstructed labor(OR = 12.21 (95% CI 6.01, 24.82)), and partograph utilization (OR = 0.12 (95% CI 0.09, 0.17)). Almost one in twenty-five mothers had uterine rupture in Ethiopia. Urban residence, primiparity, previous cesarean section, obstructed labor and partograph utilization were significantly associated with uterine rupture. Therefore, intervention programs should address the identified factors to reduce the prevalence of uterine rupture.

Subject terms: Health care, Medical research, Risk factors

Introduction

Uterine rupture is a tearing of the gravid uterine wall during pregnancy or delivery commonly on its lower part1–3. The tear can extend to the uterine serosa and may involve the bladder and broad ligament4,5. Disruption of uterine wall displaces the fetus into the abdomen, causes severe asphyxia and perinatal death and may necessitate massive transfusion or hysterectomy because of massive maternal bleeding4,6.

Uterine rupture is a rare 0.07%7 obstetric complication worldwide8 but it is a serious life-threatening which can adversely affect subsequent pregnancies9, and associated with significant and high maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality. It is one of the major public health concerns2,10 with 33% of maternal fatality rate and 52% of perinatal mortality rate11,12. The prevalence of uterine rupture in Ethiopia is higher (16.68%)2,13,14 compared to 1.3% in less developed countries7. Moreover, maternal morbidity and mortality are important public health issues in Ethiopia15,16.

Previous studies reported several factors that were associated with uterine rupture. The main reason for uterine rupture is the rapid increase in the number of previous cesarean deliveries. Additionally, factors like induction of labor, birth weight, gestational age and maternal characteristics were also associated with uterine rupture11–13,17–19. Women who had a previous cesarean section and whose labor was induced with uterotonic drugs also have an increased risk of uterine rupture and its subsequent complications20–22. Trial of labor after cesarean section (TOLAC) has comparable complication23,24 for most pregnancies with history of previous cesarean section25, although it has a high success rate26. However, recent reports showed that the rate of TOLAC is reducing27, despite the increasing rate of cesarean section globally28.

Identification of the factors associated with uterine rupture is one of the interventions to reduce the problem. Additionally, prompt diagnosis and timely identification of high-risk women, prompt diagnosis was also recommended29. Additionally, a more vigilant approach to prevent prolonged and obstructed labor, use of partograph30, quick referral to a well-equipped center and prevention of other obstetrics complications14 are key strategies to prevent uterine rupture.

Only few studies were conducted in Ethiopia on the prevalence of uterine rupture, although most of them focused on limited geographical areas. Therefore, we conducted this systematic review and meta-analysis to assess the pooled prevalence and determinants of uterine rupture in Ethiopia. The findings of the study will help to design effective strategies on the prevention strategies of uterine rupture in limited resource settings.

Methods

Search strategy and study selection

We conducted this systematic review and meta-analysis of all observational published studies to assess the pooled prevalence and determinants of uterine rupture in Ethiopia. Retrieving of the included studies was done in different databases such as Google scholar, African Journals Online, CINHAL, HINARI, Science Direct, Cochrane Library, EMBASE and PubMed (Medline) without restricting the study period. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) guideline was strictly followed during systematic review and meta-analysis31.

A combination of search terms that best describe the study variables were used to retrieve articles. These include risk factors, determinants, predictors, factors, magnitude, prevalence, incidence, uterine rupture, laparotomy, hysterectomy, and Ethiopia. The terms were combined using "OR' and "AND" Boolean operators. Additionally, reference list of the already identified articles were checked to find additional eligible articles but were missed during the initial searching.

Inclusion criteria

Study design All observational studies were included.

Study period Studies conducted until August 2018 were included.

Participants Women who had given birth at least once before data collection period of the included studies.

Language Only articles written in English language were included.

Publication status All studies regardless of publication status were considered.

Exclusion criteria

Studies which we couldn’t access texts after three emails to the cross ponding authors were excluded.

Outcome measure

Prevalence uterine rupture was the main outcome of this systematic review and meta-analysis. The pooled prevalence of uterine rupture was determined considering studies in which the status of uterus after delivery was reported. Additionally, determinants of uterine rupture among mothers were the outcome of this study.

Data extraction

Data for this study were extracted from the included articles using data extraction checklist. Data extraction was made using Microsoft Excel sheet. Two of the authors (AAA and LBZ) participated in extracting data from the included studies. The data extraction checklist contains variables like author name, publication year, study design, sample size, and exposure characteristics that included the prevalence, partograph utilization, augmentation, residence, obstructed labor, previous Caesarean section (C/S) and antenatal care visit (ANC).

Quality assessment

An intensive assessment of all articles included in this study was done by the two authors (AAA, MSB, KAG and LBZ). Newcastle–Ottawa assessment checklist32 for observational studies was used to assess the quality of each study included in this research. The tool has three sections. The first section was on methodological assessment and rated out of five stars, and the second section was on comparability evaluation and was rated out of three stars. The third section of the quality assessment tool was on assessing statistical analysis and outcome for each included study. There was a joint discussion between the authors for uncertainty, and the mean quality score was used to decide the quality of the included studies in the meta-analysis. Finally, studies scored ≥ 6 were grouped as having high quality.

Statistical analysis, risk of bias and heterogeneity

Important data extracted from each primary (original) study through Microsoft Excel were exported to STATA version 14 software for analysis. Then, standard for each included studies was computed using Binomial distribution formula. To determine the pooled estimate metan STATA command was computed considering random-effect model. Forest plots with 95% confidence interval (CI) were used to present the findings of the study. The weight of each study is described by the size of each box, whereas the crossed line shows the CI at 95%. Publication bias was also assessed using Egger’s and Begg’s tests, and a p-value of less than 0.05 was used to declare its statistical significance33,34. Due to the presence of heterogeneity among33, subgroup analysis was computed considering the geographical region in which the studies were conducted.

Results

Selection of included studies

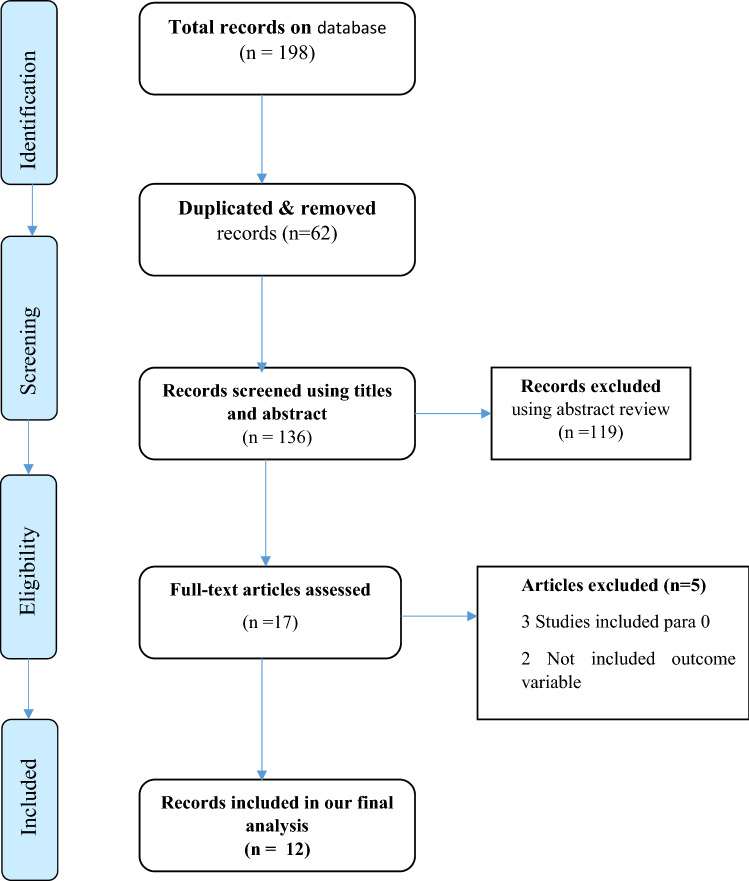

Database search resulted in a total of 198 research articles. Duplicated studies (n = 62) through their titles and abstracts were removed. Studies that passed abstract review were also screened using their title. Finally, a total of twelve studies were included in the current systematic review and meta-analysis (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA diagram showing studies utilized for systematic and meta-analysis of uterine rupture in Ethiopia.

Description of included studies

The characteristics of all included studies were presented in Table 1. Except one study, which used a retrospective cohort study design34, eight were cross-sectional studies3,15,35–40 and there were case–control studies41–43. This study included studies conducted from 1995 to 2018 on uterine rupture in Ethiopia. From this, four were conducted in Amhara region3,35,37,44, three were in Oromia region36,38,40, and two were conducted in SNNPR34,39. From the cross-sectional and retrospective studies, a total of 40,012 participants were included, observational studies and was used as the sample of in determining the pooled prevalence of uterine rupture. Additionally, 340 cases and 850 controls were included from case–control studies for the factor analysis, in addition to the sample used for prevalence estimation (Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptions of the studies utilized in the meta-analysis.

| Study ID | Study design | Prevalence | Sample | Region | Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Admassu et al.35 | Cross-sectional | 3.8 | 1830 | Amhara | 9 |

| Chamiso et al.36 | Cross-sectional | 2.6 | 2185 | Oromia | 9 |

| Akine Eshete34 | Retrospective cohort | 1.8 | 2498 | SNNPR | 8 |

| Getahun14 | Cross-sectional | 16.68 | 750 | Amhara | 8 |

| Aliyu3 | Cross-sectional | 9.5 | 854 | Amhara | 6 |

| Astatikie et al.15 | Cross-sectional | 2.44 | 10,379 | Amhara | 9 |

| Woldeyes et al.38 | Cross-sectional | 1.6 | 2737 | Oromia | 7 |

| Alemayehu40 | Cross-sectional | 3.7 | 10,270 | Oromia | 6 |

| Mengistie39 | Cross-sectional | 1.6 | 8509 | SNNPR | 7 |

Prevalence of uterine rupture in Ethiopia

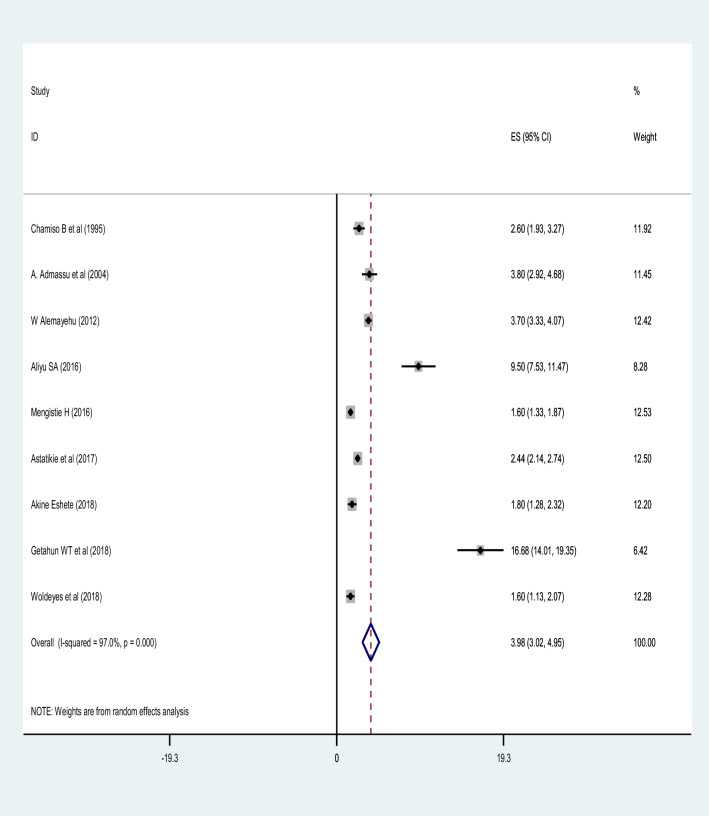

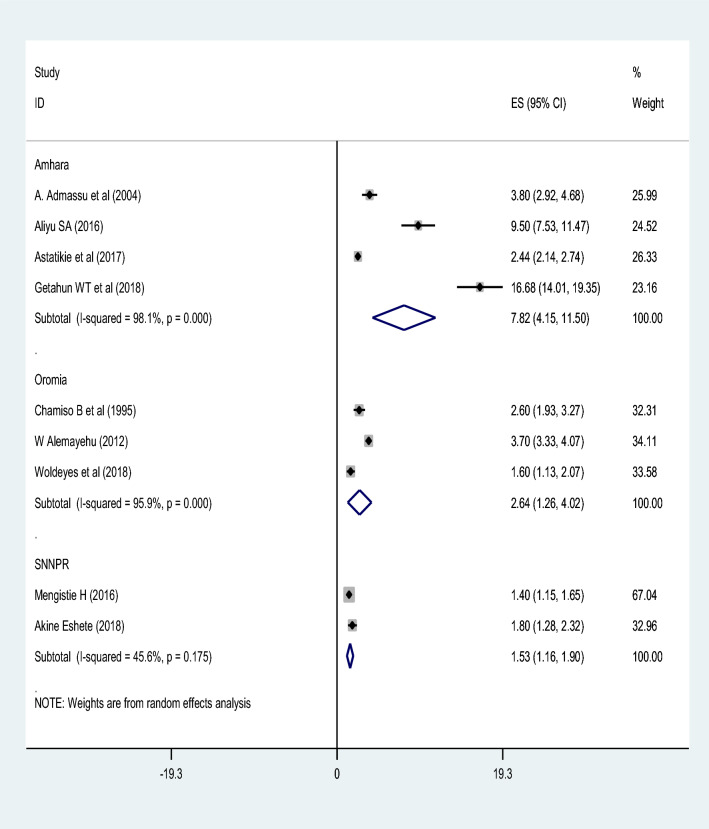

The prevalence of uterine rupture using the included studies ranged from 1.4 to 16.68%38,40. The pooled prevalence of uterine rupture in Ethiopia was 3.98% (95% CI 3.02, 4.95). The random-effect model was used to analyze the pooled prevalence, however, a high and significant heterogeneity among the included studies (I2 = 97.3%; P-value ≤ 0.001) was observed (Fig. 2). Based on the subgroup analysis by study region, the highest prevalence of uterine rupture was in Amhara region 7.82% (95% CI 4.15, 11.50) and the lowest was in SNNPR 1.53% (95% CI 1.16, 1.90). However, there was significant heterogeneity in the included studies. Trim and fill meta-analysis was also conducted (Fig. 3).

Figure 2.

A forest plot describing the pooled prevalence of uterine rupture in Ethiopia.

Figure 3.

A forest plot shows the subgroup prevalence analysis of uterine rupture by study region.

Factors associated with uterine rupture

The current review identified different factors associated with uterine rupture in Ethiopia. Significantly associated factors were residence, parity, history of cesarean section, obstructed labor and partograph utilization.

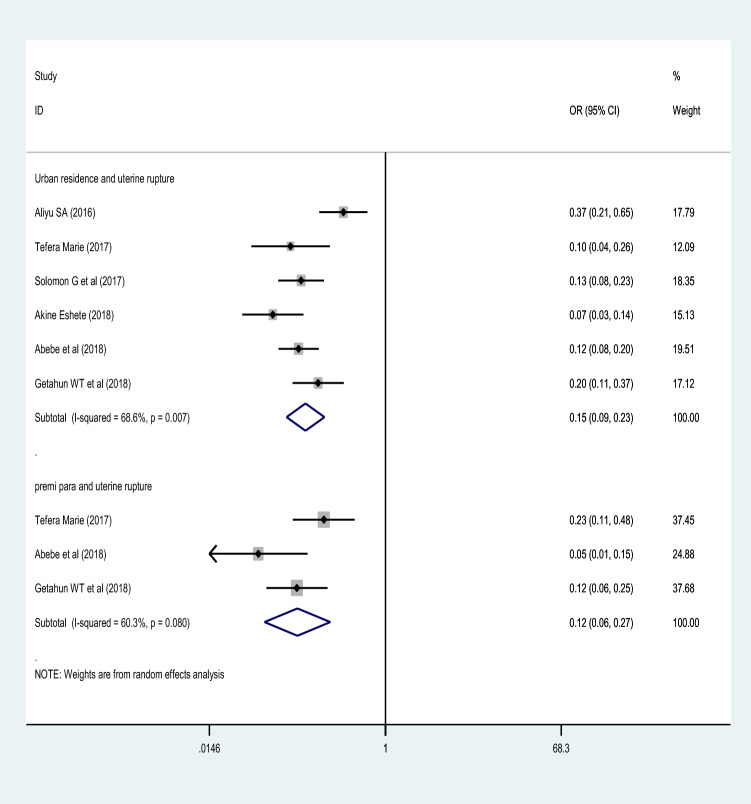

Maternal residence

The maternal residence was significantly associated with uterine rupture. Using the studies included in group of meta-analysis3,35,38,42–44, women who live in urban areas were 85% less likely to have uterine rupture (OR = 0.15 (95% CI 0.09, 0.23) compared to women living in rural areas. Random effect model of analysis was used. The heterogeneity test showed statistically significant heterogeneity; I2 = 68.6%, p-value = 0.007. However, there was no significant publication bias (Begg’s and Egger’s test for, and P-value = 0.598 and 0.851, respectively) (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

A forest plot describing the association of residence and parity with uterine rupture.

Parity

This group of analysis was conducted using three studies38,42,43. The meta-analysis finding showed parity as a strong predictor of uterine rupture. Women who were parity one were 88% less likely to have uterine rupture (OR = 0.12 (95% CI 0.06, 0.27)). There was no statistically significant heterogeneity among the included studies (I2 = 60.3%, p-value = 0.090) and no publication bias with Egger's and Begg's test of P-value = 0.964 and 0.602, respectively (Fig. 4).

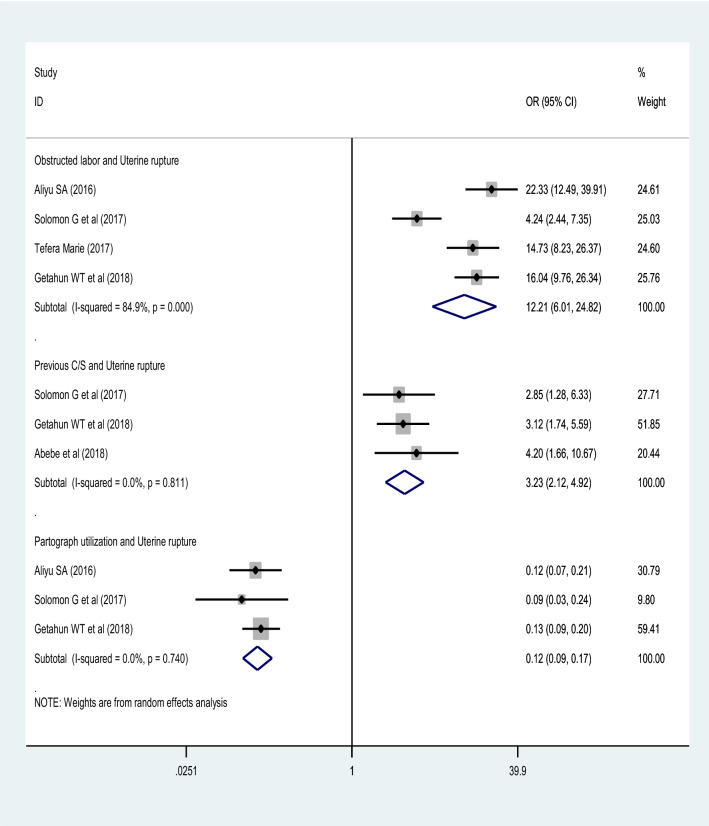

Previous cesarean section

A strong association was observed between previous cesarean section with uterine rupture. Women who had previous cesarean section were 3.23 times more likely to develop uterine rupture compared to those who had no such history (OR = 3.23 (95% CI 2.12, 4.92)). This was true for all studies included in this analysis38,43,44. Using the random effect model of analysis and the I2 statistics (0.0%), there was no significant heterogeneity (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

A forest plot describing the associations of obstructed labor, previous C/S, and partograph utilization with uterine rupture.

Obstructed labor

This systematic and meta-analysis included four studies3,38,42,44 to check the effect of obstructed labor on uterine rupture, and a significant association was observed. Women who were diagnosed for obstructed labor were more than twelve times more likely to have uterine rupture (OR = 12.21 (95% CI 6.01, 24.82)). The analysis was conducted using the random-effects model. The I2 statistics (84.9%) showed high heterogeneity, but Egger’s test showed no evidence of publication bias (p-value = 0.962) (Fig. 5).

Utilization of partograph

A significant association was also observed between partograph utilization and uterine rupture using data of three studies3,38,44. After a random effect model analysis, mothers whose labor were attended using partograph were 88% less likely to have uterine rupture (OR = 0.12 (95% CI 0.09, 0.17)). I2 test statistics (0.0%) showed no heterogeneity. Both Egger’s (p-value = 0.117) and Begg’s (p-value = 0.118) tests also showed no publication bias (Fig. 5).

Discussion

Reducing rates of primary cesarean section helps to reduce complications related to uterine rupture2. There is also an improvement in uterine rupture reduction with the implementation of nationally adopted guidelines on TOLAC46. Quality obstetric care, antenatal and family planning services with complete packages are important interventions in the reduction uterine rupture1,10,43.

In this study, we have estimated the national level of uterine rupture in Ethiopia. Our findings showed that the pooled prevalence of uterine rupture in Ethiopia was 3.98% with higher variability among regional states of the country, 1.53% in SNNPR to 7.82% in Amhara region. This estimated pooled prevalence of uterine rupture in Ethiopia is higher than nationwide studies conducted in western countries, 3.6 per 10,000 deliveries in Belgium46, 5.9 per 10,000 pregnancies in the Netherlands47, and 1.9 per 10,000 deliveries in United kingdom13. This much discrepancy and less prevalence of uterine rupture in developed countries1 might be due appropriate application of TOLAC to reduce repeated cesarean sections in developed countries4. Additionally, it could also be due to the higher prevalence of home delivery48, less optimal ANC attendance49, and delay in seeking healthcare services50,51.

In agreement with previous studies done in Ethiopia38,43 and Uganda52,53, this systematic review and meta-analysis study identified mothers who were residing in rural areas were more likely to face uterine rupture. The odds of uterine rupture were 85% times lower among urban residents compared with rural residents in this study. This might be due to the higher percentage of home birth in rural residents48 and their healthcare-seeking behavior depends usually on when complications arise.

Our finding also quantified obstructed labor as a strong determinant of uterine rupture in Ethiopia. Women who were diagnosed with obstructed labor were 12.21 times more likely to develop uterine rupture. Similarly, it is supported by previous studies in the same country in; Debre Markos37, Dessie53, and Bahir Dar54 and other nationwide studies outside the country in Uganda55, India29, Sweden14, Senegal and Mali56, and Niger57. This finding was also in line with a systematic review and meta-analysis in both developing and developed countries conducted by WHO58. This might be due to the higher teenage pregnancies in the corresponding countries secondary to low education attainment59 like in Ethiopia60, Uganda61, Niger62, India63 and Mali64 in which teenagers usually have less developed pelvic canal69–67 and have low ANC utilizations68,69.

This study also revealed women who were para one were 88% less likely to have uterine rupture than women with multiparity. This finding is supported by different prior studies in different countries in Ethiopia42, Norway8,69, Senegal and Mali56, Uganda51, and Israel70. It might be attributed to the fact as increasing parity increases the elasticity and strength of the uterine muscle (Myometrium) decreases38,71.

Likewise, previous cesarean section has been identified as a strong determinant of uterine rupture, women who had previous cesarean sections were more than 3 times more likely to be affected by uterine rupture. This finding was similar to others studied in Ethiopia42,53, Norway8, Globally58, USA71, and Nigeria72. Recent findings show the increasing uterine rupture goes through increasing cesarean section 29,73 due to prior uterine scar since the cesarean section alters the elasticity properties of the myometrium and collagen birefringence74 makes the uterus easily ruptured.

Women for whom partograph was utilized were 88% less likely to have uterine rupture than women who had no partograph during childbirth. This finding is in agreement with previous studies done in the same country, Ethiopia3,37,75. The reason behind might be that partograph predicts the possible complications of labor and helps to have timely decisions and interventions76. Uterine rupture is usually preceded by changes in uterine contractions77 prevented through proper partograph utilization78.

Limitations and strength of the study

There is no study on uterine rupture conducted in Ethiopia at national level before this systematic and meta-analysis. Therefore, it shows the problem at the country level. However, it has limitation that the included studies’ designs were cross sectional and case control. Because of this the temporal relationships of outcome variable with determinants cannot be established.

Conclusion

The pooled prevalence of uterine rupture in Ethiopia was high. Residence, partograph utilization, obstructed labor, previous C/S and parity were determinants of uterine rupture. The Ethiopian ministry of health should focus on preventing or reducing uterine rupture through facilitating and supervising of proper partograph utilization Moreover, unnecessary cesarean deliveries should be avoided. Additionally, intervention programs should also focus on the identified factors.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge all authors whose studies included in this research.

Abbreviations

- ANC

Antenatal care

- C/S

Cesarean section

- TOLAC

Trial of labor after cesarean section

- CI

Confidence interval

- OR

Odds ratio

- SNNPR

Southern Nations, Nationality and Peoples Region

- WHO

World Health Organization

- SE

Standard error

- PRISMA

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis

Author contributions

A.A.A. and L.B.Z. were involved in the design, selection of articles, data extraction, statistical analysis, and manuscript writing of this review whereas; K.A.G., M.S.B. and G.M.K. were involved in data extraction, statistical analysis, and reviewing and editing the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Data availability

All data utilized in this study are available from the corresponding upon request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Hofmeyr GJ, Say L, Gülmezoglu AM. WHO systematic review of maternal mortality and morbidity: The prevalence of uterine rupture. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2005;112:1221–1228. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00725.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Justus Hofmeyr G, Say L, Metin Gülmezoglu A. Systematic review: WHO systematic review of maternal mortality and morbidity: The prevalence of uterine rupture. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2005;112:1221–1228. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00725.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aliyu SA, Yizengaw TK, Lemma TB. Prevalence and associated factors of uterine rupture during labor among women who delivered in Debre Markos hospital north West Ethiopia. Intern. Med. 2016;6:1000222. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vandenberghe G, et al. Nationwide population-based cohort study of uterine rupture in Belgium: Results from the Belgian Obstetric Surveillance System. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e010415. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Metz, T.D., Berghella, V. & Barss, V.A. Trial of labor after cesarean delivery: Intrapartum management. U UpToDate, Post TW ur. UpToDate. Waltham, MA UpToDate (2019).

- 6.Bujold E, Gauthier RJ. Neonatal morbidity associated with uterine rupture: What are the risk factors? Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2002;186:311–314. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.119923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guise J-M, et al. Systematic review of the incidence and consequences of uterine rupture in women with previous caesarean section. BMJ. 2004;329:19. doi: 10.1136/bmj.329.7456.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Al-Zirqi I, Daltveit AK, Forsén L, Stray-Pedersen B, Vangen S. Risk factors for complete uterine rupture. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017;216:165–e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tanos V, Toney ZA. Uterine scar rupture—Prediction, prevention, diagnosis, and management. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2019;59:115–131. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2019.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fofie CO. A two year review of uterine rupture in a regional Hospital. Ghana Med. J. 2010;44(3):98–102. doi: 10.4314/gmj.v44i3.68892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaczmarczyk M, Sparén P, Terry P, Cnattingius S. Risk factors for uterine rupture and neonatal consequences of uterine rupture: A population-based study of successive pregnancies in Sweden. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2007;114:1208–1214. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2007.01484.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.El Joud DO, Prual A, Vangeenderhuysen C, Bouvier-Colle MH. Epidemiological features of uterine rupture in West Africa (MOMA study) Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol. 2002;16:108–114. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3016.2002.00414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fitzpatrick KE, et al. Uterine rupture by intended mode of delivery in the UK: A national case-control study. PLoS Med. 2012;9:e1001184. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Getahun WT, Solomon AA, Kassie FY, Kasaye HK, Denekew HT. Uterine rupture among mothers admitted for obstetrics care and associated factors in referral hospitals of Amhara regional state, institution-based cross-sectional study, Northern Ethiopia, 2013–2017. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0208470. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0208470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Astatikie G, Limenih MA, Kebede M. Maternal and fetal outcomes of uterine rupture and factors associated with maternal death secondary to uterine rupture. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17:117. doi: 10.1186/s12884-017-1302-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Organization, W. H. World Health Statistics 2016: Monitoring Health for the SDGs Sustainable Development Goals. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vogel JP, et al. Use of the Robson classification to assess caesarean section trends in 21 countries: A secondary analysis of two WHO multicountry surveys. Lancet Glob. Health. 2015;3:e260–e270. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)70094-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Betrán AP, et al. The increasing trend in caesarean section rates: Global, regional and national estimates: 1990–2014. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0148343. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0148343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Al-Zirqi I, Stray-Pedersen B, Forsén L, Daltveit A, Vangen S. Uterine rupture: Trends over 40 years. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2016;123:780–787. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.13394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Al-Zirqi I, Stray-Pedersen B, Forsén L, Vangen S. Uterine rupture after previous caesarean section. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2010;117:809–820. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2010.02533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith GCS, Pell JP, Pasupathy D, Dobbie R. Factors predisposing to perinatal death related to uterine rupture during attempted vaginal birth after caesarean section: Retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2004;329:375. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38160.634352.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aboyeji AP, Ijaiya MA, Yahaya UR. Ruptured uterus: A study of 100 consecutive cases in Ilorin, Nigeria. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2001;27:341–348. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2001.tb01283.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takeya, A. et al. Trial of labor after cesarean delivery (TOLAC) in Japan: rates and complications. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 1–7 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Meier PR, Porreco RP. Trial of labor following cesarean section: a two-year experience. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1982;144:671–678. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(82)90436-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lehmann S, Baghestan E, Børdahl PE, Muller Irgens L, Rasmussen SA. Trial of labor after cesarean section in risk pregnancies: A population-based cohort study. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2019;98:894–904. doi: 10.1111/aogs.13565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levin, G. et al. Trial of labor after cesarean in adolescents—A multicenter study. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. (2020). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Sharma A. Labour Room Emergencies. Berlin: Springer; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zelop C, Heffner LJ. The downside of cesarean delivery: Short-and long-term complications. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2004;47:386–393. doi: 10.1097/00003081-200406000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sinha M, et al. Uterine rupture: a seven year review at a tertiary care hospital in New Delhi, India. Indian J. Community Med. Off. Publ. Indian Assoc. Prev. Soc. Med. 2016;41:45. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.170966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Javed I, Bhutta S, Shoaib T. Role of partogram in preventing prolonged labour. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2007;57:408–411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Int. J. Surg. 2010;8:336–341. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Modesti PA, et al. Panethnic differences in blood pressure in Europe: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0147601. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0147601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eshete A, Mekonnen S, Getachew F. Prevalence and factors associated with rupture of gravid uterus and feto-maternal outcome: A one-year retrospective. Ethiop. Med. J. 2018;56:43–49. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Admassu A. Analysis of ruptured uterus in Debre Markos hospital, Ethiopia. East Afr. Med. J. 2004;81(1):52–5. doi: 10.4314/eamj.v81i1.8796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chamiso B. Rupture of pregnant uterus in Shashemene General Hospital, south Shoa, Ethiopia (a three year study of 57 cases) Ethiop. Med. J. 1995;33:251–257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Getahun WT, Solomon AA, Kassie FY, Kasaye HK, Denekew HT. Uterine rupture among mothers admitted for obstetrics care and associated factors in referral hospitals of Amhara regional state, institution-based cross-sectional study, Northern Ethiopia, 2013–2017. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:1–14. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0208470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Woldeyes WS, Asefa D, Muleta G. Incidence and determinants of severe maternal outcome in Jimma University teaching hospital, south-West Ethiopia: A prospective cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18:255. doi: 10.1186/s12884-018-1879-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mengistie H, Amenu D, Hiko D, Mengistie B. Maternal and perinatal outcomes of uterine rupture patients among mothers who delivered at Mizan Aman general hospital, SNNPR, south west Ethiopia; a five year retrospective hospital based study. MOJ Womens Health. 2016;2:13–23. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alemayehu W, Ballard K, Wright J. Primary repair of obstetric uterine rupture can be safely undertaken by non-specialist clinicians in rural Ethiopia: A case series of 386 women. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2013;120:505–508. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marie Bereka T, Mulat Aweke A, Eshetie Wondie T. Associated factors and outcome of uterine rupture at Suhul General Hospital, Shire Town, North West Tigray, Ethiopia 2016: A case-control study. Obstet. Gynecol. Int. 2017;2017:8272786. doi: 10.1155/2017/8272786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Abebe F, Mannekulih E, Megerso A, Idris A, Legese T. Determinants of uterine rupture among cases of Adama city public and private hospitals, Oromia, Ethiopia: A case control study. Reprod. Health. 2018;15(1):161. doi: 10.1186/s12978-018-0606-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gebre S, Negassi A. Risk factors for uterine rupture in Suhul General Hospital case control study. Electron. J. Biol. 2017;13:198–202. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Astatikie G, Limenih MA, Kebede M. Maternal and fetal outcomes of uterine rupture and factors associated with maternal death secondary to uterine rupture. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17:1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12884-017-1302-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Abebe F, Mannekulih E, Megerso A, Idris A, Legese T. Determinants of uterine rupture among cases of Adama city public and private hospitals, Oromia, Ethiopia: A case control study. Reprod. Health. 2018;15:161. doi: 10.1186/s12978-018-0606-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vandenberghe G, et al. Nationwide population-based cohort study of uterine rupture in Belgium: Results from the Belgian obstetric surveillance system. BMJ Open. 2016;6:1–8. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zwart JJ, et al. Uterine rupture in the Netherlands: a nationwide population-based cohort study. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2009;116:1069–1080. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2009.02136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kaewkiattikun K. Effects of immediate postpartum contraceptive counseling on long-acting reversible contraceptive use in adolescents. Adolesc. Health Med. Ther. 2017;8:115. doi: 10.2147/AHMT.S148434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tesfaye G, Loxton D, Chojenta C, Semahegn A, Smith R. Delayed initiation of antenatal care and associated factors in Ethiopia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod. Health. 2017;14:150. doi: 10.1186/s12978-017-0412-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tiruneh FN, Chuang K-Y, Chuang Y-C. Women’s autonomy and maternal healthcare service utilization in Ethiopia. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2017;17:718. doi: 10.1186/s12913-017-2670-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mukasa PK, et al. Uterine rupture in a teaching hospital in Mbarara, western Uganda, unmatched case-control study. Reprod. Health. 2013;10:29. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-10-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kadowa I. Ruptured uterus in rural Uganda: Prevalence, predisposing factors and outcomes. Singapore Med. J. 2010;51:35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Workie A, Getachew Y, Temesgen K, Kumar P. Determinants of uterine rupture in Dessie Referral Hospital, North East Ethiopia, 2016: Case control design. Int. J. Reprod. Contracept. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018;7:1712–1717. doi: 10.18203/2320-1770.ijrcog20181900. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ahmed DM, Mengistu TS, Endalamaw AG. Incidence and factors associated with outcomes of uterine rupture among women delivered at Felegehiwot referral hospital, Bahir Dar, Ethiopia: Cross sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;8:1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12884-018-2083-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Musaba MW, et al. Risk factors for obstructed labour in Eastern Uganda: A case control study. PLoS ONE. 2020;15:1–14. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0228856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Delafield R, Pirkle CM, Dumont A. Predictors of uterine rupture in a large sample of women in Senegal and Mali: Cross-sectional analysis of QUARITE trial data. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18:432. doi: 10.1186/s12884-018-2064-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Osemwenkha PA, Osaikhuwuomwan JA. A 10-year review of uterine rupture and its outcome in the University of Benin Teaching Hospital, Benin City. Niger. J. Surg. Sci. 2016;26:1. doi: 10.4103/1116-5898.196256. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Motomura K, et al. Incidence and outcomes of uterine rupture among women with prior caesarean section: WHO Multicountry Survey on Maternal and Newborn Health. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:1–9. doi: 10.1038/srep44093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mohr R, Carbajal J, Sharma BB. The influence of educational attainment on teenage pregnancy in low-income countries: A systematic literature review. J. Soc. Work Glob. Community. 2019;4:2. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Birhanu BE, Kebede DL, Kahsay AB, Belachew AB. Predictors of teenage pregnancy in Ethiopia: A multilevel analysis. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-6845-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Manzi, F. et al. Factors associated with teenage pregnancy and its effects in Kibuku Town Council, Kibuku District, Eastern Uganda: A cross sectional study. (2018).

- 62.Ahinkorah, B. O. Topic: prevalence and determinants of adolescent pregnancy among sexually active adolescent girls in Niger. J. Public Health 1–5 (2019).

- 63.Kumar S. Teenage marriages and induced abortion among women of reproductive age group (15–49 years) residing in an urbanized village of Delhi. Indian J. Youth Adolesc. Health. 2019;6:15–20. doi: 10.24321/2349.2880.201903. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Odimegwu C, Mkwananzi S. Factors associated with teenage pregnancy in sub-Sharan African factors associated with teen pregnancy in sub-Saharan Africa: A multi-country cross-sectional study. Afr. J. Reprod. Health. 2016;20:94–107. doi: 10.29063/ajrh2016/v20i3.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Isah AD, et al. Fibroid uterus: A case study. Am. Fam. Physician. 2017;08:725–736. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Barageine JK, Tumwesigye NM, Byamugisha JK, Almroth L, Faxelid E. Risk factors for obstetric fistula in Western Uganda: A case control study. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e112299. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shaikh S, Shaikh AH, Shaikh SAH, Isran B. Frequency of obstructed labor in teenage pregnancy. Nepal J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2012;7:37–40. doi: 10.3126/njog.v7i1.8834. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bako B, Barka E, Kullima AA. Prevalence, risk factors, and outcomes of obstructed labor at the University of Maiduguri Teaching Hospital, Maiduguri, Nigeria. Sahel Med. J. 2018;21:117. doi: 10.4103/1118-8561.242748. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Al-Zirqi I, Daltveit AK, Vangen S. Maternal outcome after complete uterine rupture. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2019;98:1024–1031. doi: 10.1111/aogs.13579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hochler H, et al. Grandmultiparity, maternal age, and the risk for uterine rupture—A multicenter cohort study. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2020;99:267–273. doi: 10.1111/aogs.13725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Vilchez G, et al. Contemporary epidemiology and novel predictors of uterine rupture: A nationwide population-based study. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2017;296:869–875. doi: 10.1007/s00404-017-4508-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Adegbola, O. & Odeseye, A. K. Uterine Rupture at Lagos University Teaching Hospital. (2017).

- 73.Chazotte C, Cohen WR. Catastrophic complications of previous cesarean section. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1990;163:738–742. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(90)91059-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Buhimschi CS, et al. The effect of dystocia and previous cesarean uterine scar on the tensile properties of the lower uterine segment. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2006;194:873–883. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Aliyu SA, Yizengaw TK, Lemma TB. Prevalence and associated factors of uterine rupture during labor among women who delivered in Debre Markos Hospital North West Ethiopia. Intern. Med. 2016;6:222. doi: 10.4172/2165-8048.1000222. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mathai M. The partograph for the prevention of obstructed labor. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2009;52:256–269. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0b013e3181a4f163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Vlemminx MWC, de Lau H, Oei SG. Tocogram characteristics of uterine rupture: A systematic review. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2017;295:17–26. doi: 10.1007/s00404-016-4214-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sanyal U, Goswami S, Mukhopadhyay P. The role of partograph in the outcome of spontaneous labor. Nepal J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2014;9:52–57. doi: 10.3126/njog.v9i1.11189. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data utilized in this study are available from the corresponding upon request.