Abstract

Background and Aims

Sex-based differences are known to significantly contribute to patient outcomes of chronic disease however the role of patient sex in cirrhosis is unclear. We aim to study the relationship between patient sex and cirrhosis.

Methods

We analyzed a cohort of 20,045 patients with cirrhosis using a Chicago-wide electronic health record database that was linked with the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) and the state death registry cause of death data. Adjusted Cox survival analyses and competing risk analyses were performed to obtain sub-distribution hazard ratios for liver-related cause of death.

Results

Female and male patients had similar age, racial distribution, insurance status, and comorbidity status by Elixhauser score. Females had high rates of cholestatic liver disease (17.1% vs 6.2%, p<0.001) and NASH (29.8% vs 21.2% p<0.001) than males. They were less likely to have portal hypertensive complications and had lower peak MELD-Na scores during follow up. Female sex was associated with a decreased hazard of all-cause mortality (aHR 0.85, 95% CI [0.80–0.90]). This effect was attenuated when liver-related mortality was examined (sHR 0.93 95% CI [0.87, 1.00]). No significant difference was noted for women who were ‘ever listed’ in competing risk analyses for either all-cause mortality (sHR 1.09, 95% CI [0.88, 1.35]) or liver-related death (sHR 1.12 95% CI [0.87, 1.43]) despite lower rates of listing (7.5% vs 9.8%, p<0.001) and transplant (3.5% vs 5.2%, p<0.001).

Conclusions

In this longitudinal study of patients with cirrhosis, female sex was associated with a survival advantage likely driven by lower rates of non-liver related death. Women had no difference in risk of liver related death despite lower rates of listing and transplantation.

Keywords: cirrhosis, outcomes, gender, female, disparities

Lay summary

Patient sex is an important contributor in many chronic diseases, including cirrhosis. Prior studies have suggested that female sex is associated with worse outcomes. We analyzed a cohort of 20,045 patients with cirrhosis using a Chicago-wide electronic health record database. Using multivariate competing risk analyses, we found that female sex in cirrhosis is actually associated with a lower risk of all-cause mortality and has no association with liver related mortality. Our findings are novel because we show that women with cirrhosis have a similar risk of liver related death as compared to their male counterparts, despite lower rates of listing and transplantation.

Introduction

Cirrhosis is a leading cause of death estimated to affect more than 600,000 people every year[1,2]. Patient sex is universally recognized as an important contributor to the etiology, epidemiology, and severity of the clinical courses for patients with cirrhosis [3–5]. Although patient sex is a non-modifiable risk factor, understanding its effect is important for risk stratification and ensuring that disparities in care can be addressed equitably.

Despite its importance, the relationship between patient sex and outcomes of patients with cirrhosis remains unclear. A recent study in a large sample of hospitalized patients with cirrhosis found that women were 14% less likely to die while hospitalized[6]. This analysis was limited in that it could not track outcomes post discharge and patient sex itself has been associated with admission to the hospital, potentially introducing selection bias[7–9]. Another large national sample of outpatients with cirrhosis in England found that women were 16% less likely to suffer all-cause mortality. However, this analysis could not adjust for non-liver comorbidities which are known to have different distributions between men and women and may influence non-liver related death[10–12].

Other analyses done among the highly selected patients who are listed for liver transplantation may suggest that women have higher waitlist mortality, higher rates of organ declines, and higher rates of delisting[13–18]. Unfortunately these studies suffer from selection bias inherent to the listing process and lack generalizability to all patients with cirrhosis because only a small fraction of patients with cirrhosis undergo transplant evaluation and waitlisting[1,19]. These studies of waitlisted patients also suffer from outcome ascertainment bias because no follow up data are captured after delisting, an event that has been noted to be more common in women[14].

The HealthLNK database is a multicenter, population-based database of electronic health records (EHR) from six large health systems in the Chicago area and captures over 2.4 million unique patients[20]. This dataset is linked with UNOS as well as the state death registry. Thus, we used this longitudinal data source that follows patients across episodes of care to study the relationship between patient sex and cirrhosis.

Patients and methods

Data sources

Three databases were linked for this study, the HealthLNK Data repository, the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) database and the Social Security Death Master File[20].

The HealthLNK database is a deduplicated, repository of EHR data from six healthcare institutions in greater metropolitan Chicago area. These institutions include five major academic healthcare systems: Northwestern Medicine, University of Chicago Hospitals and Clinic, Rush University Medical Center, University of Illinois at Chicago Medical Center, and Loyola University Medical Center; and one large county health system, Cook County Health and Hospitals System. HealthLNK comprises a wealth of data from approximately 2.4 million patients and spans healthcare encounters from January 1,2006 to December 31, 2012 [21]. Patient data including demographics, procedure codes, diagnostic codes, medications, and laboratory values were abstracted from inpatient, outpatient, and emergency department encounters.

The UNOS database comprises national registry data of all patients waitlisted for organ transplantation in the US. Death dates and death certificate data were gathered from the Social Security Death Master File for the state of Illinois. Patients who visited multiple centers or who were in multiple databases were linked and deduplicated using a privacy preserving algorithm as previously published[20]. Records were de-identified prior to analysis.

Primary Outcome and Ascertainment

The primary outcome was mortality. For models unadjusted for competing risks, all-cause mortality was used. For competing risk models, liver-related mortality was the primary outcome and compared to the same analysis with all-cause mortality. Death certificates were manually reviewed for cause of death. This death certificate review was performed as previously published using defined rules (see supplement 1)[22]. Cause of death was classified as liver-related, non-descript, or non-liver related. Liver-related deaths were further sub-classified into “Infectious”, “Bleeding”, “Oncologic”, “Varices”, “Portal Hypertensive Complications”, and “Other” [22]. For the purposes of this paper, “Bleeding” was amalgamated in the “Other” category and “Varices” were amalgamated into the “Portal Hypertensive Complication” category.

Study population and Covariates

After approval by the Institutional Review Board at Northwestern University, all patients age 18 or older with an ICD-9 code for cirrhosis between January 1,2006 and December 31,2012 were identified. Patients were included if they had one of the three cirrhosis Ninth Revision of International Classification of Diseases and Health Related Problems (ICD-9) codes (571.2, 571.5, or 571.6) similar to prior studies.[21,23,24] Model for End Stage Liver Disease Sodium (MELD-Na) scores were calculated with serum creatinine, bilirubin, INR, and sodium using the standard method from the OPTN. For patients missing any component lab values, future values were used for MELD-Na calculation. The maximum time span allowed between labs for one calculation was 30 days. If multiple scores were available, the peak score during the study was used for analysis (“max MELD-Na score”). If no scores were available from the electronic health records (EHR) and patients were listed for transplant, biological MELD-Na was manually calculated from UNOS data. Organ allocation during this era was determined by MELD score, but because MELD-Na better adjusts for the risk of death, especially in patients with lower scores who are often female, it was used compare risk of death between men and women[25,26]. Etiologies and complications of cirrhosis were defined by combinations of diagnosis and procedure codes as previously described in the literature (see supplement 2) [27–35]. Similar to clinical practice, we allowed patients to have multiple etiologies of cirrhosis if they qualified based on diagnosis code. We felt that this would allow for optimal statistical adjustment for the additive risk of multiple liver related conditions. The one exception to this was a diagnosis of Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) cirrhosis which we defined as the patients who were included due to a diagnosis of non-alcoholic cirrhosis and who did not have any code for Hepatitis C virus (HCV), Hepatitis B Virus (HBV), biliary cirrhosis, autoimmune hepatitis, Wilsons, or hemochromatosis (see supplement 2). The Elixhauser comorbidity index, widely used to determine the burden of concurrent comorbidities from diagnosis codes, was calculated for all patients. It was modified to remove diagnosis codes used for other liver related variables similar to past publications (see supplement 2) [21,24,36,37]. Portal hypertensive complications such as ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, varices, or variceal bleeding were defined based on presence of diagnosis or procedure code at any time during follow up. Female and male sex was abstracted from the medical record of the participating sites.

Statistical analysis

Demographics were compared using chi-squared and t tests for categorical and continuous variables respectively. All-cause mortality was compared in univariate analysis via Kaplan-Meier plots with log rank testing, and in multivariate analysis with Cox proportional hazards modeling (adjusting for age, race, insurance status, Elixhauser score, presence of portal hypertensive complications, presence of hepatocellular carcinoma, and etiology of cirrhosis). Time at risk for survival analyses was defined as time from inclusion to either death or transplant with censoring at the end of the study (December 31,2012). Competing risk analysis was performed in two steps. The first modeled the risk of all-cause mortality with transplant as a competing risk. The second modeled the risk of for liver-related death while treating other causes of death and transplant as competing risks. Competing risk analysis was performed using Fine-Gray methodology[38,39]. The above analyses were stratified by missingness of MELD-Na score and “ever-listed” for transplant. For complete case analysis, lack of MELD-Na measurement (yes/no) was used as a covariate in the adjusted model to include patients without MELD-Na measurement while peak MELD-Na was used in stratified analyses. Adjusted cumulative incidence plots for the full cohort were produced from the competing risk model based on mean cohort characteristics for continuous variables and reference values for categorical variables. Specifically, these plots model the different outcomes by patient sex for a white patient with the mean cohort age, mean Elixhauser Index, who has public insurance, with compensated cirrhosis and non-missing MELD-Na. Given the high prevalence of HCV in the cohort, this was chosen as the etiology for the models. A sensitivity analysis was performed that excluded patients on warfarin to examine the potential for falsely elevated MELD-Na score not related to liver dysfunction. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data processing and analysis was performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) and RStudio version 1.2.1578 with R packages icd, tableone, comorbidity, crr, and cmprsk[39–41].

Results

Population characteristics

During the study period, 20,091 patients met the inclusion criteria of whom 46 patients were missing sex data (0.2%) leaving 20,045 patients for analysis. Patient characteristics are listed in Table 1. Of these patients 8,544 (43%) were female. Overall, female patients were of similar age, racial distribution, insurance status, and comorbidity status by Elixhauser score. Although the top etiology of cirrhosis in both groups was Hepatitis C virus (HCV), women patients had higher rates of Cholestatic disease (1,457; 17.1% vs 708; 6.2%, p<0.001), Autoimmune hepatitis (531; 6.2% vs 166; 1.4%, p<0.001), and Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) related cirrhosis (2,545; 29.8% vs 2,442; 21.2%, p<0.001). In contrast, men had higher rates of alcohol related cirrhosis (4,779; 41.6% vs 1,840; 21.5% p<0.001), peak MELD-Na during follow up (mean peak MELD-Na 19.0 vs 17.2, p<0.001), rates of HCC (1,992; 17.3% vs 820; 9.6%, p<0.001) and portal hypertensive complications such as ascites, variceal bleeding, or hepatic encephalopathy (see Table 1, p<0.001 for all). A higher proportion of female patients had persistently low MELD-Na (never above 15: 2,149, 52.2% vs 2,754; 43.1%, p<0.001). Additionally, female patients were less likely to have received the necessary labs for calculation of a MELD-Na score (missing in 4,424; 51.8% vs 5,108; 44.4% p<0.001).

Table 1.

Cohort Demographics

| Full Cohort | At least one MELD-Na score | Ever-listed | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | p | Male | Female | p | Male | Female | p | ||

| n | 11501 | 8544 | 6393 | 4120 | 1106 | 634 | ||||

| Age (mean (SD))# | 56.5 (11.2) | 58.0 (12.4) | <0.001 | 55.7 (10.9) | 57.2 (12.0) | <0.001 | 55.6 (9.8) | 55.9 (10.5) | 0.511 | |

| Mean Days of follow up time* # | 883 | 991 | <0.001 | 872 | 1000 | <0.001 | 820 | 1024 | <0.001 | |

| Race n (%)^ | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.451 | |||||||

| White | 5278 (45.9) | 3835 (44.9) | 2728 (42.7) | 1753 (42.5) | 698 (63.1) | 407 (64.2) | ||||

| Black | 2354 (20.5) | 2064 (24.2) | 1259 (19.7) | 972 (23.6) | 85 (7.7) | 58 (9.1) | ||||

| Hispanic | 2000 (17.4) | 1272 (14.9) | 1307 (20.4) | 730 (17.7) | 132 (11.9) | 79 (12.5) | ||||

| Asian | 318 (2.8) | 209 (2.4) | 187 (2.9) | 104 (2.5) | 35 (3.2) | 18 (2.8) | ||||

| Other | 1551 (13.5) | 1164 (13.6) | 912 (14.3) | 561 (13.6) | 156 (14.1) | 72 (11.4) | ||||

| Insurance n (%)^ | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.235 | |||||||

| Medicare/Medicaid | 5418 (47.1) | 4592 (53.7) | 2834 (44.3) | 2126 (51.6) | 615 (55.6) | 368 (58.0) | ||||

| Private | 3946 (34.3) | 2900 (33.9) | 1973 (30.9) | 1271 (30.8) | 423 (38.2) | 219 (34.5) | ||||

| Other | 2137 (18.6) | 1052 (12.3) | 1586 (24.8) | 723 (17.5) | 68 (6.1) | 47 (7.4) | ||||

| Elixhauser score37 (mean (SD))$ | 4.03 (3.41) | 3.99 (3.58) | 0.463 | 4.24 (3.32) | 4.32 (3.47) | 0.246 | 5.17 (3.44) | 5.34 (3.55) | 0.316 | |

| Etiology n(%)^ | HCV | 5047 (43.9) | 3077 (36.0) | <0.001 | 2809 (43.9) | 1555 (37.7) | <0.001 | 537 (48.6) | 264 (41.6) | 0.006 |

| Alcohol | 4779 (41.6) | 1840 (21.5) | <0.001 | 3427 (53.6) | 1222 (29.7) | <0.001 | 630 (57.0) | 207 (32.6) | <0.001 | |

| NASH | 2442 (21.2) | 2545 (29.8) | <0.001 | 1007 (15.8) | 1034 (25.1) | <0.001 | 98 (8.9) | 127 (20.0) | <0.001 | |

| HBV | 1161 (10.1) | 483 (5.7) | <0.001 | 676 (10.6) | 256 (6.2) | <0.001 | 123 (11.1) | 26 (4.1) | <0.001 | |

| Cholestatic | 708 (6.2) | 1457 (17.1) | <0.001 | 393 (6.1) | 640 (5.5) | <0.001 | 183 (16.5) | 141 (22.2) | 0.004 | |

| Autoimmune | 166 (1.4) | 531 (6.2) | <0.001 | 102 (1.6) | 279 (6.8) | <0.001 | 21 (1.9) | 35 (5.5) | <0.001 | |

| Hemochromatosis | 108 (0.9) | 46 (0.5) | 0.002 | 48 (0.8) | 24 (0.6) | 0.368 | 7 (0.6) | 8 (1.3) | 0.273 | |

| Wilsons | 41 (0.4) | 36 (0.4) | 0.536 | 24 (0.4) | 23 (0.6) | 0.222 | 12 (1.1) | 14 (2.2) | 0.98 | |

| Complication n (%)^ | ||||||||||

| HCC | 1992 (17.3) | 820 (9.6) | <0.001 | 1346 (21.1) | 522 (12.7) | <0.001 | 454 (41.0) | 165 (26.0) | <0.001 | |

| Ascites | 4264 (37.1) | 2623 (30.7) | <0.001 | 2797 (43.8) | 1626 (39.5) | <0.001 | 725 (65.6) | 425 (67.0) | 0.564 | |

| Hepatic Encephalopathy | 4224 (36.7) | 2737 (32.0) | <0.001 | 2804 (43.9) | 1710 (41.5) | 0.02 | 772 (69.8) | 438 (69.1) | 0.8 | |

| Variceal status n (%)^ | <0.001 | 0.001 | 0.398 | |||||||

| No esophageal varices | 8002 (69.2) | 6342 (74.2) | 3987 (62.4) | 2710 (65.8) | 392 (35.4) | 245 (38.6) | ||||

| Varices without bleeding | 3110 (27.0) | 2000 (23.4) | 2217 (34.7) | 1310 (31.8) | 644 (58.2) | 349 (55.0) | ||||

| Variceal Bleeding | 389 (3.4) | 202 (2.4) | 189 (3.0) | 100 (2.4) | 70 (6.3) | 40 (6.3) | ||||

| MELD-Na | No MELD-Na Score n (%)^ | 5108 (44.4) | 4424 (51.8) | 0.001 | --- | --- | ---- | ---- | ||

| <15 during follow up n(%)^ | 2754 (43.1) | 2149 (52.2) | <0.001 | 2754 (43.1) | 2149 (52.2) | <0.001 | 257 (23.2) | 158 (24.9) | 0.462 | |

| Min MELD-NA (mean (SD))# | 13.42 (7.07) | 11.87 (6.38) | <0.001 | 13.42 (7.07) | 11.87 (6.38) | <0.001 | 12.54 (6.18) | 11.24 (5.30) | <0.001 | |

| Max MELD-NA (mean (SD))# | 19.03 (9.01) | 17.16 (9.12) | <0.001 | 19.03 (9.01) | 17.16 (9.12) | <0.001 | 23.82 (9.36) | 23.45 (9.37) | 0.433 | |

Time at risk was defined as time from first inclusion diagnosis code to the first of transplant, death, or study end.

Please see supplement for definitions of categories

T-test

Chi-Squared test

Unadjusted Analysis

On unadjusted analysis women had lower unadjusted mortality during the entire study period (2,145; 25.2% vs 3,546; 30.6%, p<0.001) and when limited to time at risk (2,102; 24.6% vs 3,442; 29.9%, p<0.001, Table 2). This effect persisted when adjusted for time at risk (9.1 vs 12.4 deaths per 100 person-years, p<0.0001 log rank test). Among patients who died, both female patients and male patients most commonly died of liver-related causes (liver related deaths: female 1,268; 14.8% vs male 2,180; 19.0%, p<0.001). When univariate analysis was performed among patients who had at least one MELD-Na score during follow-up, the above relationships continued to hold (Table 2).

Table 2.

Unadjusted Outcomes

| Full Cohort | At least one MELD-Na score | Ever-listed | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | p | Male | Female | p | Male | Female | p | ||

| n | 11501 | 8544 | 6393 | 4120 | 1106 | 634 | ||||

| Ever Listed n (%)# | 1130 (9.8) | 644 (7.5) | <0.001 | 1106 (17.3) | 634 (15.4) | 0.014 | --- | --- | ||

| Mean days to first delisting# | --- | --- | --- | --- | 569 | 740 | <0.001 | |||

| *Event at end of time at risk n (%)^ | <0.001 | 0.082 | ||||||||

| Alive | 7465 (64.9) | 6146 (71.9) | <0.001 | 3823 (59.8) | 2709 (65.8) | 272 (24.6) | 193 (30.4) | |||

| Liver related death | 2180 (19.0) | 1268 (14.8) | 1419 (22.2) | 756 (18.3) | 200 (18.1) | 113 (17.8) | ||||

| Non-liver related death | 851 (7.4) | 587 (6.9) | 498 (7.8) | 312 (7.6) | 29 (2.6) | 19 (3.0) | ||||

| Transplant | 594 (5.2) | 296 (3.5) | 581 (9.1) | 295 (7.2) | 581 (52.5) | 295 (46.5) | ||||

| Non-descript death | 411 (3.6) | 247 (2.9) | 72 (1.1) | 48 (1.2) | 24 (2.2) | 14 (2.2) | ||||

| Cause of Liver-Related death n (%)^ | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.001 | |||||||

| Infectious | 434 (12.6) | 315 (15.0) | 276 (13.9) | 189 (16.9) | 28 (14.0) | 25 (22.1) | ||||

| Oncologic | 578 (16.8) | 167 (7.9) | 400 (20.1) | 103 (9.2) | 54 (27.0) | 10 (8.8) | ||||

| Portal HTN | 212 (6.2) | 139 (6.6) | 145 (7.3) | 78 (7.0) | 14 (7.0) | 10 (8.8) | ||||

| Other | 956 (27.8) | 647 (30.8) | 598 (30.0) | 386 (34.6) | 104 (52.0) | 68 (60.2) | ||||

| *Gross Mortality n (%) | 3442 (29.9) | 2102 (24.6) | 1989 (31.1) | 1116 (27.1) | 253 (22.9) | 146 (23.0) | ||||

| *Mortality rate (per 100 patient years)# | 12.4 | 9.1 | <0.001 | 13 | 9.9 | <0.001 | 10.2 | 8.2 | 0.015 | |

Time at risk was defined as time from first inclusion diagnosis code to the first of transplant, death, or study end.

All follow up was defined as first inclusion to study end without censoring at transplant

T-test

Chi-Squared test

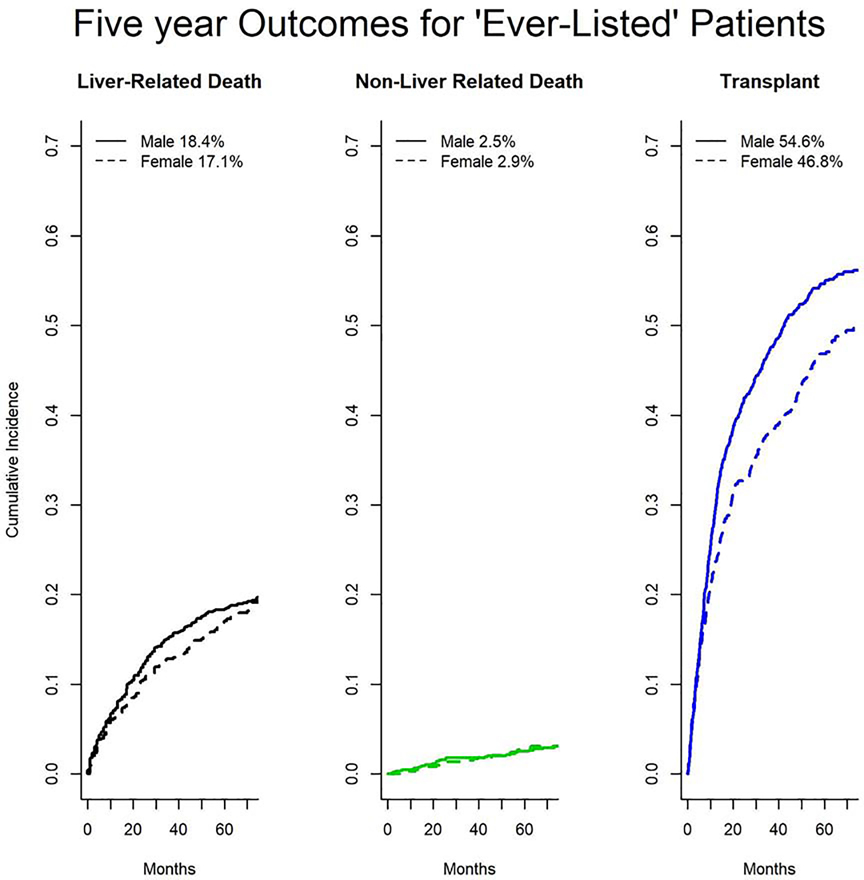

Only 1,774 (8.9%) of the cohort were “ever listed” during follow up. Women were less likely to be listed for transplant (644; 7.5% vs 1,130; 9.8% p<0.001). Of this group 1,740 (98%) had at least one MELD-Na score available during the study period. Among these patients women were more likely to be on the list for longer prior to an event (mean 740 days vs 569 days, p<0.001) but equally likely to be delisted without transplant (37% of men vs 40% of women, p=0.246).Women were less likely to undergo transplantation (296; 3.5% vs 594; 5.2%, p<0.001) but still had lower rates of death among patients who were ‘ever listed’ (Figure 1, 8.2 vs 10.2 deaths per 100 person-years, p=0.015). After taking into account transplant, women did not have significantly different unadjusted outcomes at the end of follow up (p=0.082).

Fig. 1. Cumulative Incidence of Outcomes Among Patients who were ‘Ever-Listed’ (n= 1,744).

With likelihood ratio testing, women have lower rates of transplant (p<0.005) but no difference in liver-related (p=0.73) or non-liver related (p=0.69) death among patients who were ‘ever listed’.

Multivariate analysis

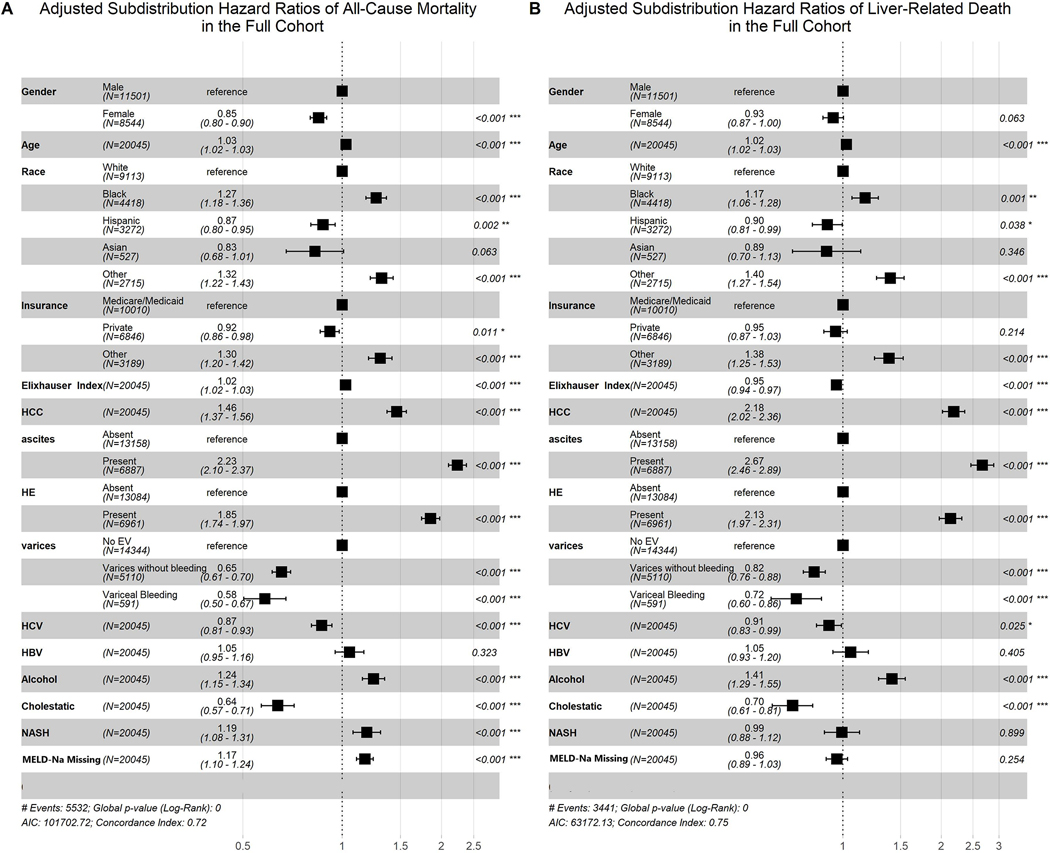

Of the 20,045 patients, 19,977 (99.6%) were included for Cox proportional hazard model of all-cause mortality. This analysis, adjusted for age, race, insurance status, Elixhauser score, presence of portal hypertensive complications, presence of hepatocellular carcinoma, missingness of MELD-Na measurement, and etiology of cirrhosis demonstrated that female sex was independently associated with a decreased hazard of all-cause mortality (aHR 0.84, 95% CI [0.79–0.88], p<0.001). This finding was similar when risk of all-cause mortality was adjusted for the competing risk of transplant (Figure 2A, sHR 0.85, 95% CI [0.80–0.90], p<0.001). Other findings for this competing risk model can be seen in Figure 2. All-cause mortality was also increased in association with older age, black race, unknown insurance status, presence of HCC, higher Elixhauser Index, presence of ascites, presence of encephalopathy, alcoholic liver disease, NASH, and lack of a MELD-Na measurement during follow up; the most significant protective associations were with Hispanic race, Asian race, known variceal status, HCV, and Cholestatic liver disease (Figure 2). The association of female sex and death was attenuated when liver related death was examined with the above covariates and treating transplant and non-liver related death as competing risks (Figure 2B, sHR 0.93, 95% CI [0.87–1.00], p=0.063). Adjusted cumulative incidence plots based on this analysis are shown in Figure 3.

Fig. 2. Competing risk analysis Among the Full Cohort.

Women have lower adjusted all-cause mortality than men (panel A, sHR 0.85 95% CI [0.80, 0.90], p<0.001) when adjusting for the competing risk of transplant and multiple variables (age, race, insurance status, Elixhauser Index, HCC, portal hypertensive complications, etiology of cirrhosis and missingness of MELD-Na). Women have no difference in Liver related death (panel B, sHR 0.93, 95% CI [0.87–1.00], p=0.063).

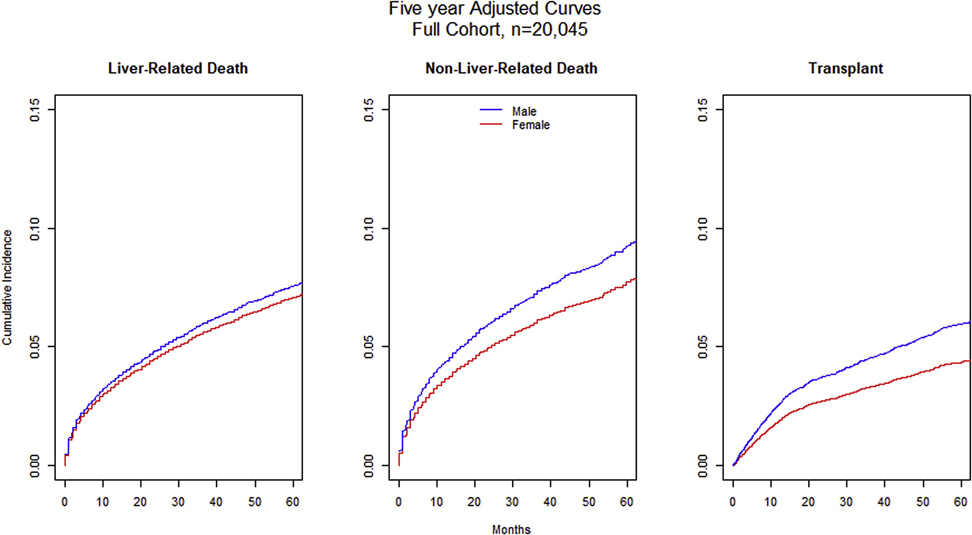

Fig 3. Adjusted Cumulative Incidence Curves for the Full cohort (n= 20,045).

Using competing risk analysis, women have lower rates of liver related death (sHr 0.93, 95% CI [0.87–1.00], p=0.063), non-liver-related death (sHR 0.83, 95% CI [0.74, 0.92], p<0.001), and transplant (sHR 0.73, 95% CI [0.63, 0.84], p<0.001).

The second analysis incorporated the covariates above but adjusted for MELD-Na score. It included 10,470 patients (52.2% of the first analysis) and again showed that female sex is associated with a significantly decreased hazard of all-cause mortality in the Cox model (aHR 0.90 95% CI [0.83–0.97], p=0.007) with a similar result when modeling all-cause mortality with transplant as a competing risk (sHR 0.93 95% CI [0.86–1.00], p=0.046). Similar to the first analysis, when liver-related death was modeled with the above covariates while treating transplant and non-liver related death as competing risk, the protective association of female sex was attenuated (sHR 1.00 95% CI [0.91 – 1.10], p=NS).

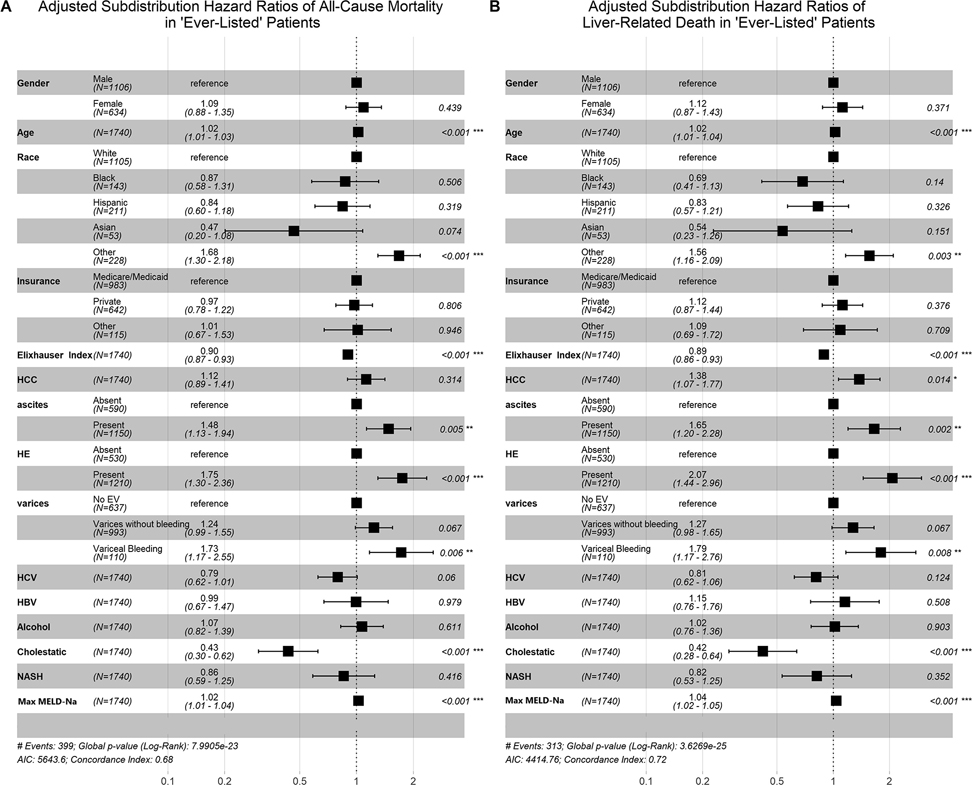

When the same procedure was performed on patients who were ‘ever listed’ for transplant and included all variables above, findings were similar. This analysis continued to show a similar magnitude of the protective association between female sex and all-cause mortality on survival analyses (aHR 0.93 95% CI [0.75 – 1.16] p=0.54). When adjusted for competing risk of transplant, women had a non-significant increase in hazard of all-cause mortality (Figure 4, sHR 1.09 95% CI [0.88 – 1.35] p=0.44) largely unchanged by examining liver-related death while treating transplantation and non-liver death as a competing risk (sHR 1.12 95% CI [0.87 – 1.43] p=0.37). . Among these listed patients, age, unknown race, portal hypertensive complications, HCC and MELD-Na were associated with an elevated risk of all-cause mortality (p<0.001 for all). When all three of the multivariate competing risk models above were performed with the same covariates but with transplantation as the outcome and treating death of any cause as a competing risk, women were less likely to be transplanted (p<0.001). In all three models, Schoenfeld residuals for patient sex were consistent with the proportional hazards assumption.

Fig. 4. Competing risk analysis Among Patients who were ‘Ever-Listed’.

There was no difference between patient sex and either all-cause mortality (Panel A, sHR 1.09 95% CI [0.88 – 1.35] p=0.44) or liver related death (Panel B, sHR 1.12 95% CI [0.87 – 1.43] p=0.37) among patients who were ‘ever-listed’ for transplant.

Sensitivity analysis

A sensitivity analysis was performed that excluded patients on warfarin to examine the potential for falsely elevated MELD-Na score not related to liver dysfunction. Among the full cohort, 1,430 (7.1%) of patients were on warfarin at some point during follow up. Female patients were no more likely to be on warfarin than male patients (p=0.96). When patients who were “ever on warfarin” were omitted from the above multivariate and competing risk analyses, there were no differences in the direction or magnitude of the results (data not shown).

On exploratory analysis, when we restricted inclusion to patients without HCC and who had at least one MELD-Na score and at least one portal hypertensive complication female sex was associated with an increased hazard of liver related death (sHR 1.14 95% CI [1.01, 1.29], p=0.03) but not all cause mortality (sHR 1.06 95% CI [0.96, 1.16]).

Given the paradoxical ‘protective’ association we found between presence of varices or variceal bleeding and death in the full cohort (Figure 2), we hypothesized that this effect actually represented patients who had access to screening and specialist care. We repeated the above analyses stratified by variceal status and found no difference in our results. Specifically, in patients without diagnosed varices, women had lower all-cause mortality (p<0.001), without difference in liver related mortality. Among the patients with varices that had not bled and among those who had a history of bleeding, there was a trend but no statistical difference in all-cause mortality or liver related death similar in size to the above analyses of patients with MELD-Na scores or ‘ever listed’ patients respectively. These analyses are limited by the small number of patients with variceal bleeding (n=591). Furthermore, when we looked at patients who were ‘ever listed’ and therefore presumably had adequate screening and access to care, variceal status had the expected detrimental association with mortality (Figure 4).

Discussion

In this large, city wide study, we examined the relationship between patient sex and outcomes in patients with cirrhosis. Our results support that women with cirrhosis have lower all-cause mortality but have similar rates of liver related death. Furthermore, we found that women had lower rates of transplant but did not have a difference in their all-cause or liver-related mortality compared to men. This may be appropriate given their lower portal hypertensive complication rate, lower MELD-Na score, and lower rate of HCC. Interestingly, when we performed a subanalysis among patients without HCC but who did have a portal hypertensive complication and who had at least one MELD-Na score, we did find a significant association between female sex and liver related death. Similarly, when we stratified by history of varices or variceal bleeding, a similar effect size was seen. Taken with the lack of difference in outcomes we found among those who were ‘ever listed’, this sub-analysis suggests that women in this group are less likely to survive to listing. Unfortunately the nature of our study cannot provide determination as to if this finding is because women are more likely to die due to portal hypertensive complications or whether they are less likely to be successfully listed. Overall, our findings suggest that among patients with cirrhosis in general, patient sex in itself is not associated with liver-related death after adjustment for disease severity. Conversely, we found that female sex had a protective association with non-liver related death.

Since we utilized a large population cohort, our findings most closely compare to other large population based studies. A recent study using the National Inpatient Sample noted a decrease in all-cause mortality among women in hospitalized patients with cirrhosis (aOR 0.86, p<0.001), a remarkably comparable effect size to our study[6]. Similarly, a population based cohort of patients with cirrhosis in the United Kingdom found that female sex had a significant protective association against all-cause mortality (aHR for females 0.84, 95% CI (0.77, 0.91))[10]. Due to the design of these studies, neither were adjusted for MELD-Na nor did they evaluate liver-related cause of death. Our findings are novel because we show that female patients with cirrhosis have a similar risk of liver related death as compared to their male counterparts after adjusting for non-liver related death and MELD-Na. The biological plausibility of this result is supported by the well-known association between male sex and poor outcomes in many non-liver related diseases[42,43].

Additionally, although the primary focus of this paper was on the general patient with cirrhosis, we also followed a subset of 1,774 patients who were ‘ever listed’ for transplant. Our results show no difference in the likelihood of all-cause mortality or liver-related death for this group despite a lower rate of listing and transplantation among women. Based on our observed all-cause mortality in the ‘ever listed’ patients (23.0% in women vs 22.9% in men), a post hoc power calculation to detect a difference at an a of 0.05 and 80% power would require 5.9 million listed patients perhaps implying there truly is no difference to be found in this group.

The initial concern that women with cirrhosis had higher mortality and lower rate of transplant originated from a study that only examined listed patients and included patients from the pre-MELD era[13]. Although this study reported a 30% increased odds of the composite outcome of ‘death on the waitlist’ or ‘delisting due to being too sick’ for women using logistic regression, this method may not adequately adjust for time at risk and can overestimate effect size. In fact, their survival analysis found an effect size of more modest significance (aHR, 1.09; 95% CI, 1.02–1.17; P=.01) similar to our results.

Other studies have also struggled to find a true difference in outcomes between men and women after adequate adjustment. For instance one study that followed patients after delisting did not find a difference in death after delisting in women compared to men[17,44]. In another study, the increased mortality seen in women listed for transplant could be fully accounted for when adjusted for glomerular filtration rate (GFR)[16]. Similarly, female sex no longer conferred a harmful association in listed patients when adjusted for patient height[18]. Taken together, our results support the current literature that female sex itself does not confer an increased risk of liver related death. In clinical practice however, women are generally shorter than men and tend to be at risk for overestimation of GFR, hence conferring risk not by sex per se, but by attributes associated with female sex. Future studies should examine how these patient attributes can be taken into account to more accurately prioritize transplantation. Somewhat reassuringly, our study did not find a difference in rates of death despite lack of adjustment for either of those attributes.

Our study has several strengths and limitations. Although our cohort encompasses the full range of care for patients with cirrhosis, from diagnosis to decompensation, listing, delisting, death, and cause of death in a large multicenter dataset, it also suffers from the usual limitations known to ICD coding and retrospective analysis. Although these codes were not specifically validated in our database, , we used ICD based definitions similar to those validated in the multiple other databases, and we performed multiple adjusted analyses to adjust for confounders and competing risks[21,23,34,35,24,27–33]. Another instance of this can be seen in our analyses where presence of varices or variceal bleeding had a paradoxically protective association with mortality. We hypothesized that these codes were entered for patients who had access to specialist care and were undergoing variceal surveillance. We demonstrated that our findings on the relationship between female sex and outcomes still held even on stratified analyses which controlled for these access issues. We used a very large database that encompasses much of the Chicago area, however our data set does not span multiple UNOS regions. Since geography is known to heterogeneously affect disparities our results may not be generalizable to other regions in the country or world[17]. Some patients had missing labs to calculate a MELD-Na score. However, to prevent the introduction of bias, we did not use imputation or use of other missing data methods. Instead, ‘missing MELD’ was used as a covariate in our models when applicable to help adjust for this. Lastly, although on average we did not note different outcomes among men and women with cirrhosis, this effect could be different among selected subgroups, for example women with alcoholic liver disease. To offset this, we adjusted for etiologies of cirrhosis in our models.

In summary, we studied the influence of sex on outcomes in patients with cirrhosis. We found that female sex had no association with liver related mortality and a protective association with all-cause mortality. Using this large longitudinal database we also determined that despite lower rates of listing and transplantation, female candidates for liver transplantation did not have different outcomes. Although the protective association between female sex and outcomes in cirrhosis seem to be clear based on the literature and the results of our study, future studies among patients listed for transplant should be adjusted for post-delisting outcomes, patient height, and measured GFR.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments/Funding

Dr. Mazumder and Atiemo were supported by NIH grant T32DK077662 PI MM Abecassis

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors declare no conflicts of interest

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Scaglione S, Kliethermes S, Cao G, Shoham D, Durazo R, Luke A, et al. The Epidemiology of Cirrhosis in the United States. J Clin Gastroenterol 2015;49:690–6. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Murphy SL, Xu J, Kochanek KD, Curtin SC, Arias E. National Vital Statistics Reports Volume 66, Number 6, November 27, 2017. vol. 66. 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Guy J, Peters MG. Liver Disease in Women: The Influence of Gender on Epidemiology, Natural History, and Patient Outcomes. vol. 9 2013. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Parikh-Patel A, Gold EB, Worman H, Krivy KE, Gershwin ME. Risk factors for primary biliary cirrhosis in a cohort of patients from the United States. Hepatology 2001;33:16–21. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.21165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Lee WM, Squires RH, Nyberg SL, Doo E, Hoofnagle JH. Acute liver failure: Summary of a workshop. Hepatology, vol. 47, 2008, p. 1401–15. doi: 10.1002/hep.22177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Rubin jB, Sundaram V, Lai JC. Gender Differences among Patients Hospitalized with Cirrhosis in the United States. J Clin Gastroenterol 2019. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000001192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Silva MJ, Rosa M V., Nogueira PJ, Calinas F. Ten years of hospital admissions for liver cirrhosis in Portugal. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;27:1320–6. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Scaglione SJ, Metcalfe L, Kliethermes S, Vasilyev I, Tsang R, Caines A, et al. Early Hospital Readmissions and Mortality in Patients With Decompensated Cirrhosis Enrolled in a Large National Health Insurance Administrative Database. J Clin Gastroenterol 2017;51:839–44. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Rubin JB, Sinclair M, Rahimi RS, Tapper EB, Lai JC. Women on the liver transplantation waitlist are at increased risk of hospitalization compared to men. World J Gastroenterol 2019;25:980–8. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v25.i8.980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Ratib S, Fleming KM, Crooks Cj, Aithal GP, West J. 1 and 5 year survival estimates for people with cirrhosis of the liver in England, 1998–2009: A large population study. J Hepatol 2014;60:282–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Freedman VA, Wolf DA, Spillman BC. Disability-free life expectancy over 30 years: A growing female disadvantage in the US population. Am J Public Health 2016;106:1079–85. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Crimmins EM, Zhang Y, Saito Y. Trends over 4 decades in disability-free life expectancy in the United States. Am J Public Health 2016;106:1287–93. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Moylan CA, Brady CW, Johnson JL, Smith AD, Tuttle-Newhall JE, Muir AJ. Disparities in liver transplantation before and after introduction of the MELD score. JAMA - J Am Med Assoc 2008;300:2371–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Cullaro G, Sarkar M, Lai JC, Jennifer Lai CC. Sex-based disparities in delisting for being “too sick” for liver transplantation. Am J Transpl 2018;18:1214–9. doi: 10.1111/ajt.14608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Mindikoglu AL, Regev A, Seliger SL, Magder LS. Gender disparity in liver transplant waiting-list mortality: The importance of kidney function. Liver Transplant 2010;16:1147–57. doi: 10.1002/lt.22121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Mindikoglu AL, Emre SH, Magder LS. Impact of estimated liver volume and liver weight on gender disparity in liver transplantation. Liver Transplant 2013;19:89–95. doi: 10.1002/lt.23553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Mathur AK, Schaubel DE, Gong Q, Guidinger MK, Merion RM. Sex-based disparities in liver transplant rates in the United States. Am J T ransplant 2011;11:1435–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03498.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Lai JC, Terrault NA, Vittinghoff E, Biggins SW. Height contributes to the gender difference in wait-list mortality under the MELD-based liver allocation system. Am J Transplant 2010; 10:2659–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03326.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Kim WR, Lake JR, Smith JM, Schladt DP, Skeans MA, Noreen SM, et al. OPTN/SRTR 2017 Annual Data Report: Liver. Am J Transplant 2019;19:184–283. doi: 10.1111/ajt.15276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Kho AN, Cashy JP, Jackson KL, Pah AR, Goel S, Boehnke J, et al. Design and implementation of a privacy preserving electronic health record linkage tool in Chicago . J Am Med Inform Assoc 2015;22:1072–80. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocv038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Atiemo K, Skaro A, Maddur H, Zhao L, Montag S, VanWagner L, et al. Mortality Risk Factors Among Patients With Cirrhosis and a Low Model for End-Stage Liver Disease Sodium Score (<15): An Analysis of Liver Transplant Allocation Policy Using Aggregated Electronic Health Record Data. Am J Transplant 2017;17:2410–9. doi: 10.1111/ajt.14239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Mazumder NR, Atiemo K, Daud A, Kho A, Abecassis M, Levitsky J, et al. Patients with Persistently Low MELD-Na Scores Continue to be at Risk of Liver Related Death. Transplantation 2019:1. doi: 10.1097/tp.0000000000002997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Nehra MS, Ma Y, Clark C, Amarasingham R, Rockey DC, Singal AG. Use of administrative claims data for identifying patients with cirrhosis. J Clin Gastroenterol 2013;47:e50–4. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3182688d2f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Atiemo K, Mazumder N, Caicedo JC, Ganger D. Gordon EJ, Montag S, VanWagner LB, Maddur H, Goel S, Kho A, Abecassis MA, Zhoa LLD, Atiemo K, Mazumder NR, Caicedo JC, Ganger D, Gordon E, et al. The Hispanic Paradox in Patients with Liver Cirrhosis: Current Evidence from a Large Regional Retrospective Cohort Study. Transplantation 2019. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000002733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Biggins SW, Kim WR, Terrault NA, Saab S, Balan V, Schiano T, et al. Evidence-Based Incorporation of Serum Sodium Concentration Into MELD n.d. doi: 10.1053/j..gastro.2006.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Kamath P, Wiesner RH, Malinchoc M, Kremers W, Therneau TM, Kosberg CL, et al. A model to predict survival in patients with end-stage liver disease. Hepatology 2001; 33:464–70. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.22172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Chang EK, Yu CY, Clarke R, Hackbarth A, Sanders T, Esrailian E, et al. Defining a Patient Population With Cirrhosis. J Clin Gastroenterol 2016;50:889–94. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Goldberg D, Lewis J, Halpern S, Weiner M, Lo Re V III. Validation of three coding algorithms to identify patients with end-stage liver disease in an administrative database. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2012;21:765–9. doi: 10.1002/pds.3290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].KRAMER JR, DAVILA JA, MILLER ED, RICHARDSON P, GIORDANO TP, EL-SERAG HB. The validity of viral hepatitis and chronic liver disease diagnoses in Veterans Affairs administrative databases. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2007;27:274–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03572.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Kaplan DE, Dai F, Aytaman A, Baytarian M, Fox R, Hunt K, et al. Development and Performance of an Algorithm to Estimate the Child-Turcotte-Pugh Score From a National Electronic Healthcare Database. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;13:2333–2341.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Kaplan DE, Baytarian M, Kathryn BD, Rena Fox B, Kristel Hunt B, Astrid Knott B, et al. Recalibrating the Child-Turcotte-Pugh Score to Improve Prediction of Transplant-Free Survival in Patients with Cirrhosis. Dig Dis Sci 2016;61. doi: 10.1007/s10620-016-4239-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Goldberg DS, Lewis JD, Halpern SD, Weiner MG, Lo Re V III. Validation of a coding algorithm to identify patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in an administrative database. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2013;22:103–7. doi: 10.1002/pds.3367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Omino R, Mittal S, Kramer JR, Chayanupatkul M, Richardson P, Kanwal F. The Validity of HCC Diagnosis Codes in Chronic Hepatitis B Patients in the Veterans Health Administration. Dig Dis Sci 2017;62:1180–5. doi: 10.1007/s10620-017-4503-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Sada Y, Hou J, Richardson P, El-Serag H, Davila J. Validation of Case Finding Algorithms for Hepatocellular Cancer From Administrative Data and Electronic Health Records Using Natural Language Processing. Med Care 2016;54:e9–14. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182a30373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Niu B, Forde KA, Goldberg DS. Coding algorithms for identifying patients with cirrhosis and hepatitis B or C virus using administrative data. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2015;24:107–11. doi: 10.1002/pds.3721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, Fong A, Burnand B, Luthi JC, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care 2005;43:1130–9. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000182534.19832.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity Measures for Use with Administrative Data. Med Care 1998;36:8–27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Fine JP, Gray RJ. A Proportional Hazards Model for the Subdistribution of a Competing Risk. J Am Stat Assoc 1999;94:496. doi: 10.2307/2670170. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Gray RJ. A Class of $K$-Sample Tests for Comparing the Cumulative Incidence of a Competing Risk. Ann Stat 1988;16:1141–54. doi: 10.1214/aos/1176350951. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Wasey Jack O.. icd: Comorbidity Calculations and Tools for ICD-9 and ICD-10 Codes. R package version 3.3. 2018. https://cran.r-project.org/package=icd (accessed October 7, 2019). [Google Scholar]

- [41].Yoshida Kazuki and Bohn Justin. tableone: Create “Table 1” to Describe Baseline Characteristics. R package version 0.9.3. 2018. https://cran.r-project.org/package=tableone. [Google Scholar]

- [42].Mikkola TS, Gissler M, Merikukka M, Tuomikoski P, Ylikorkala O. Sex Differences in Age-Related Cardiovascular Mortality. PLoS One 2013;8. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Sex Regitz-Zagrosek V. and gender differences in health. Science & Society Series on Sex and Science. EMBO Rep 2012;13:596–603. doi: 10.1038/embor.2012.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Cullaro G, Sarkar M, Lai JC. Sex-based disparities in delisting for being “too sick” for liver transplantation. Am J Transplant 2018;18:1214–9. doi: 10.1111/ajt.14608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.