Abstract

Objectives:

To determine progestin-only pill (POP) use at 3 and 6 months postpartum among women who chose POPs at the postpartum visit.

Study Design:

Secondary data analysis of a prospective observational study with telephone interviews at 3 and 6 months postpartum to assess contraceptive use.

Results:

Of 440 women who attended the postpartum visit, 92 (20.9%) chose POPs. Current POP use was 44/84 (52.4%) at 3 months, 33/76 (43.4%) at 6 months, and 32/76 (42.1%) at both 3- and 6-month follow-up assessments.

Conclusion:

About half of women who plan POP use at the postpartum visit are not using this method at 3 months after delivery.

Implications:

About half of women with a prescription for progestin-only pills will be not using this method at 3 months postpartum; further understanding of continued sexual activity and breastfeeding may clarify pregnancy risk for those not reporting modern contraception use during the postpartum period.

Keywords: postpartum contraception, progestin-only pills, hormonal contraception, breastfeeding

1.0. Introduction

Clinicians often prescribe progestin-only pills (POPs) in the postpartum period either as a woman’s preferred method or as a bridge to estrogen-containing contraception as POPs are well-tolerated, have few contraindications, and are safe in lactating women [1–4]. While short-acting hormonal methods generally decrease rapid repeat pregnancies, the specific contribution from POPs can be difficult to measure as they are frequently categorized with combined oral contraceptive pills, patches, and rings [2,5]. However, one study demonstrated that a plan for postpartum POP use was associated with an increased risk of rapid repeat pregnancy when compared with any other reversible method, including no method at all [6]. The retrospective nature of that study limited assessment of actual POP use after prescription. In this study, we aim to investigate POP use at 3 and 6 months postpartum among women who planned POPs at the postpartum visit.

2.0. Materials and Methods

We conducted a secondary analysis using data from a prospective observational study assessing outcomes before and after the University of California, Davis Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology changed routine scheduling of the postpartum visit from 6 weeks to 2 to 3 weeks after delivery [7]. Briefly, we enrolled women who delivered at our institution, planned to return for postpartum care, and wanted to delay a subsequent pregnancy for at least one year. We excluded women who required assisted reproductive technologies to achieve the index pregnancy, planned vasectomy, underwent a permanent contraceptive procedure or hysterectomy, or had an intrauterine device (IUD) or implant placed during the delivery hospitalization. Participants reported their postpartum plan for contraception on a baseline survey completed during pregnancy. We reviewed the electronic medical record (EMR) for contraception plan at post-delivery hospital discharge, POP prescription at discharge, and the method selected at the postpartum visit. We contacted participants at 3 and 6 months after delivery to obtain information about contraception use, repeat pregnancies, and breastfeeding. The University of California, Davis Institutional Review Board approved this study, and all participants gave informed consent.

For this analysis, we evaluated the primary outcome of reported POP use at 3 and 6 months after delivery among women who chose POPs at the postpartum visit as documented in the EMR. Secondary outcomes included other contraceptive methods used (including combined oral contraceptives) and repeat pregnancies within 6 months postpartum. Additionally, we evaluated predictors of POP use, including decision for POPs during pregnancy or prior to hospital discharge, timing of postpartum visit scheduling (i.e. 6 weeks or 2–3 weeks after delivery), and breastfeeding status (i.e. none, partial, or exclusive).

We used REDCap electronic data system for data management [8] and SPSS 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) to perform descriptive statistics and comparisons between groups with Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables and t test for continuous variables.

3.0. Results

Of 440 women who attended a postpartum visit, 92 (20.9%) chose POPs per EMR documentation. All individuals desiring POPs received a prescription, either at hospital discharge (n=35, 38.0%) or postpartum visit (n=57, 62.0%). Other chosen methods most commonly included condoms (24.3%), none (21.8%), and hormonal IUD (13.4%). We had follow-up information for 84 (91.3%) participants at 3 months and 76 (82.6%) participants at 6 months postpartum. Demographics, obstetric characteristics, and breastfeeding status of POP users are presented in Table 1. All participants planned to breastfeed after delivery.

Table 1:

Characteristics of progestin-only pill (POP) users and non-users at 3- and 6-months postpartum among those who chose POPs at the postpartum visit

| Characteristic | Postpartum | 3 months postpartum | 6 months postpartum | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| visit (n=92) | POP use (n=44) | Non-POP use (n=40) | p-value | POP use (n=33) | Non-POP use (n=43) | p-value | |

| Age | 29.6±4.6 | 29.1 ±4.8 | 30.1 ±4.3 | 0.32 | 29.1 ±4.8 | 29.6 ±4.4 | 0.66 |

| Hispanic or Latina ethnicity | 24 (26.1) | 13 (29.5) | 11 (27.5) | 1.0 | 8 (24.2) | 11 (25.6) | 1.0 |

| White race | 66 (71.7) | 35 (79.5) | 27 (67.5) | 0.23 | 28 (84.8) | 28 (65.1) | 0.07 |

| College graduate or higher | 58 (63.0) | 29 (65.9) | 26 (65.0) | 1.0 | 23 (69.7) | 27 (62.8) | 0.63 |

| Full-time employment | 59 (64.1) | 29 (65.9) | 25 (62.5) | 0.82 | 22 (66.7) | 27 (62.8) | 0.81 |

| Private insurance | 76 (82.6) | 37 (84.1) | 34 (85.0) | 1.0 | 28 (84.8) | 37 (86.0) | 1.0 |

| Living with partner | 84 (91.3) | 41 (93.2) | 36 (90.0) | 0.70 | 32 (97.0) | 37 (86.0) | 0.13 |

| Parity ≥2 | 34 (37.0) | 17 (38.6) | 15 (37.5) | 1.0 | 11 (33.3) | 18 (41.9) | 0.48 |

| Prior miscarriage | 24 (6.1) | 11 (25.0) | 10 (25.0) | 1.0 | 9 (27.3) | 9 (20.9) | 0.59 |

| Prior induced abortion | 18 (19.6) | 8 (18.2) | 8 (20.0) | 1.0 | 5 (15.2) | 9 (20.9) | 0.57 |

| Index pregnancy planned | 64 (69.6) | 31 (70.5) | 27 (67.5) | 0.82 | 26 (78.8) | 27 (62.8) | 0.21 |

| Intend POPs during antepartum care | 40 (43.5) | 22 (50.0) | 15 (37.5) | 0.28 | 19 (57.6) | 16 (37.2) | 0.11 |

| Intend POPs at hospital discharge | 58 (63.0) | 24 (54.5) | 27 (67.5) | 0.27 | 19 (57.6) | 29 (67.4) | 0.47 |

| Received POP prescription at discharge | 35 (38.0) | 13 (29.5) | 15 (37.5) | 0.49 | 12 (36.4) | 15 (34.9) | 1.0 |

| Scheduled 6-week postpartum visit | 49 (53.3) | 26 (59.1) | 19 (47.5) | 0.38 | 20 (60.6) | 20 (46.5) | 0.25 |

| Breastfeeding status | |||||||

| Exclusive breastfeeding | 73 (79.3) | 22 (50.0) | 22 (55.0) | 0.67 | 13 (39.4) | 17 (38.6) | 1.0 |

| Any breastfeeding | 92 (100.0) | 35 (79.5) | 33 (82.5) | 0.79 | 20 (60.6) | 27 (62.8) | 1.0 |

Data shown as mean ± standard deviation or n (%)

POP: progestin-only pill

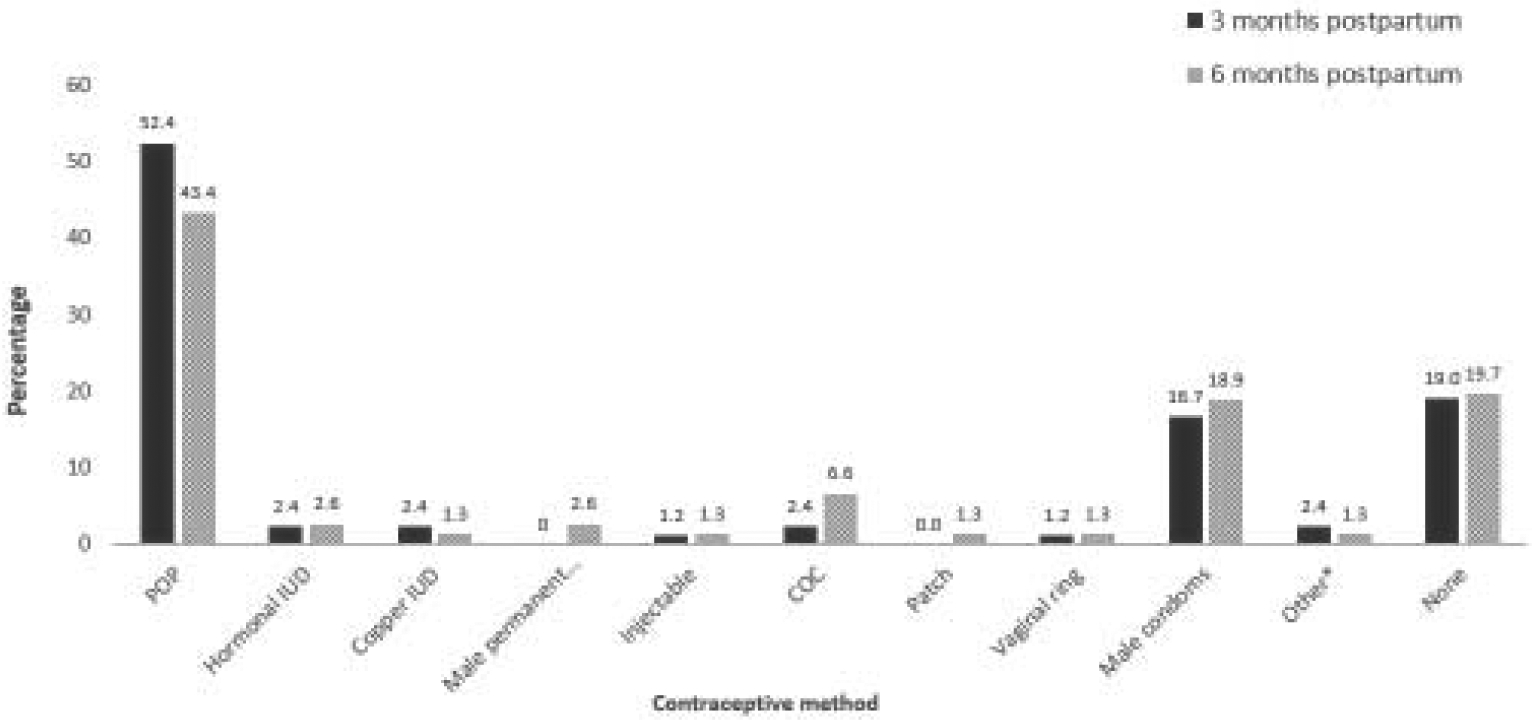

At follow-up, 44 (52.4%) and 33 (43.4%) participants reported POP use at 3- and 6-months postpartum, respectively (Figure 1). Among 76 participants with data from both 3- and 6-month interviews, 32 (42.1%) reported POP use at both assessments. For participants not reporting POP use, commonly used methods included condom use (18.9%) or no method (19.7%) by the 6-month interview (Figure 1). Two participants became pregnant within 6 months postpartum (one POP and one condom user).

Figure 1:

Contraceptive method reported at 3 and 6 months after delivery among women choosing progestin-only pills at the postpartum visit

POP=progestin-only pill; IUD= intrauterine device; COC=combined oral contraceptive pill; *Other includes withdrawal (n=1) and natural family planning (n=1) at 3-months follow-up and spermicide (n=1) at 6-months follow-up

Antepartum plan for POPs, plan for POP at hospital discharge, POP prescription at discharge, timing of postpartum visit scheduling, and breastfeeding status did not predict POP use at 3 or 6 months postpartum (Table 1).

4.0. Discussion

We found that only half of women who choose POPs at the postpartum visit are using POPs at 3 and 6 months after delivery, which may account for the previously reported increased risk of rapid repeat pregnancy with this method [6]. Because we did not confirm when participants started POPs after their postpartum visit, we cannot determine if this finding reflects a true discontinuation rate or whether participants had accepted a prescription without intending to use POPs. We also noted that participants did not use POPs as a bridge to more effective modern contraception; instead, most reported using barrier or no method at follow-up.

A strength of this study is the high follow-up through 6 months postpartum and ability to assess changes in contraceptive use over time. In contrast, previous studies have relied on retrospective evaluation of POP prescriptions at a single reference timepoint for POP use during the postpartum course [5,6]. However, our study may be limited in its generalizability to other settings as most participants were educated, privately insured, and have demonstrated ability to follow up in clinic. In addition, breastfeeding status surveys did not provide enough information to distinguish between exclusive breastfeeding and lactational amenorrhea method (LAM). Some women may have met LAM criteria (i.e. nearly or exclusively breastfeeding, amenorrheic, and within 6 months postpartum [9]) but reported “none” as the contraceptive method. Lastly, we did not obtain data regarding continued sexual activity during follow-up, and some may have reported no contraceptive method use if not sexually active. Despite the relatively high rates of reported barrier or no contraceptive use, only two participants reported a repeat pregnancy. Additional studies assessing continued sexual activity and postpartum amenorrhea may clarify pregnancy risk, especially among breastfeeding women.

Counseling regarding pregnancy spacing and contraceptive method selection is an integral component of postpartum care [10]. Given the discrepancy between planned POP use at the postpartum visit and actual reported use at 3 and 6 months after delivery, our findings demonstrate the dynamic state of contraceptive method use in the postpartum period and emphasize the importance of ongoing follow-up to facilitate shared decision-making with individuals regarding their pregnancy risk and contraceptive method choice throughout the postpartum period.

Funding:

Research in this publication was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K23HD090323. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The other authors did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures: MDC serves on an Advisory Board for Merck & Co. and TherapeuticsMD and is a consultant for Estetra, Mayne, Medicines360, and Merck & Co. The Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of California, Davis, receives research funding for contraceptive research from Daré, HRA Pharma, Medicines360, and Sebela.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- [1].Curtis KM, Tepper NK, Jatlaoui TC, Berry-Bibee E, Horton LG, Zapata LB, et al. U.S. medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep 2016;65:1–104. 10.3109/14647273.2011.602520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Thurman AR, Hammond N, Brown HE, Roddy ME. Preventing repeat teen pregnancy: postpartum depot medroxyprogesterone acetate, oral contraceptive pills, or the patch? J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2007;20:61–5. 10.1016/j.jpag.2006.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Hall KS, Trussell J, Schwarz EB. Progestin-only contraceptive pill use among women in the United States. Contraception 2012;86:653–8. 10.1016/j.contraception.2012.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Taub RL, Jensen JT. Advances in contraception: new options for postpartum women. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2017;18:677–88. 10.1080/14656566.2017.1316370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Brunson MR, Klein DA, Olsen CH, Weir LF, Roberts TA. Postpartum contraception: initiation and effectiveness in a large universal healthcare system. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2017;217:55.e1–55.e9. 10.1016/j.ajog.2017.02.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Sackeim MG, Gurney EP, Koelper N, Sammel MD, Schreiber CA. Effect of contraceptive choice on rapid repeat pregnancy. Contraception 2019;99:184–6. 10.1016/j.contraception.2018.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Chen MJ, Hou MY, Hsia JK, Cansino CD, Melo J, Creinin MD. Long-acting reversible contraception initiation with a 2- to 3-week compared with a 6-week postpartum visit. Obstet Gynecol 2017;130:788–94. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42:377–81. 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Kennedy KI, Rivera R, McNeilly AS. Consensus statement on the use of breastfeeding as a family planning method. Contraception 1989;39:477–96. 10.1016/0010-7824(89)90103-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 736: Optimizing Postpartum Care. Obstet Gynecol 2018;131:e140–50. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]