Abstract

Sepsis is defined as a dysregulated inflammatory response, which ultimately results from a perturbed interaction of both an altered immune system and the biomass and virulence of involved pathogens. This response has been tied to the intestinal microbiota, as the microbiota and its associated metabolites play an essential role in regulating the host immune response to infection. In turn, critical illness as well as necessary healthcare treatments result in a collapse of the intestinal microbiota diversity and a subsequent loss of health-promoting short chain fatty acids, such as butyrate, leading to the development of a maladaptive pathobiome. These perturbations of the microbiota contribute to the dysregulated immune response and organ failure associated with sepsis. Several case series have reported the ability of fecal microbiota transplant (FMT) to restore the host immune response and aid in recovery of septic patients. Additionally, animal studies have revealed the mechanism of FMT rescue in sepsis is likely related to the ability of FMT to restore butyrate producing bacteria and alter the innate immune response aiding in pathogen clearance. However, several studies have reported lethal complications associated with FMT, including bacteremia. Therefore, FMT in the treatment of sepsis is and should remain investigational until a more detailed mechanism of how FMT restores the host immune response in sepsis is determined, allowing for the development of more fine-tuned microbiota therapies.

Introduction

The microbiome consists of all the microbial organisms that colonize the human body, including the skin, mouth, genitourinary track, lung and gastrointestinal tract, each site maintaining a specialized microbial community structure, membership and function. Every bacterial species within the microbiome contains its own unique genome and cumulatively the microbiome contains significantly more genetic diversity than the entire human genome.1 The sheer amount of genetic diversity of the microbiota results in the unique ability of the microbiota to adapt to varying environments and contribute to numerous biological processes and may explain why variations in the microbiota have been associated with both the state of health as well as disease. Microbiota consist of bacteria, archea, viruses and fungi. When studying the organisms that make up the microbiome, which today is mostly focused on bacteria, the microbiome can be characterized based on its overall structure and function. The structure is typically reported based on next generation sequencing which has allowed researchers to better define the communities of bacteria that cannot be characterized with standard culture techniques.2,3 Structure is typically reported by describing the individual bacteria taxa that are present as well as the overall diversity of bacterial species that exists within the microbiota of interest. The function of the microbiome is highly specific to the particular niche and describes the biological processes that the members of the microbiome contribute.4 It can be inferred from sequencing data or directly measured through the use of metabolomics. Functional analysis includes how the microbiota shape various metabolites such as short chain fatty acids(SCFAs) and bile acids within the intestines.2,3 The intestinal microbiota play an important role in the production of SCFAs (butyrate, acetate, and propionate) from fermentable, dietary carbohydrates.5 The interplay of these metabolites can have a significant effect on the immune system, allowing for dysregulation in processes like sepsis and correction during microbial restoration. Overall, the community structure and function of the intestinal microbiota is strongly shaped by its environment and alterations to both can have a profound impact on the host’s response to infection, trauma, burn injury and critical illness itself.6,7

The emerging role of the microbiome in sepsis

Sepsis is generally defined as organ dysfunction secondary to a dysregulated immune response to infection.8 This complex and perturbed interaction is a function of both an altered host immune system and the biomass and virulence of the pathogens involved. When discussing the pathobiology of the “dysregulated immune response to infection” it is important to recognize that “virulence” or harmfulness (in this case the ensuing organ failure) is neither a property of the pathogen nor of the host, but rather it is a property of their interaction9. Under this conceptual framework, the microbiome and its vulnerability during the index insult and its treatment, plays an essential role in shaping both the host immune system and the pathogens that can drive a septic immune response.10

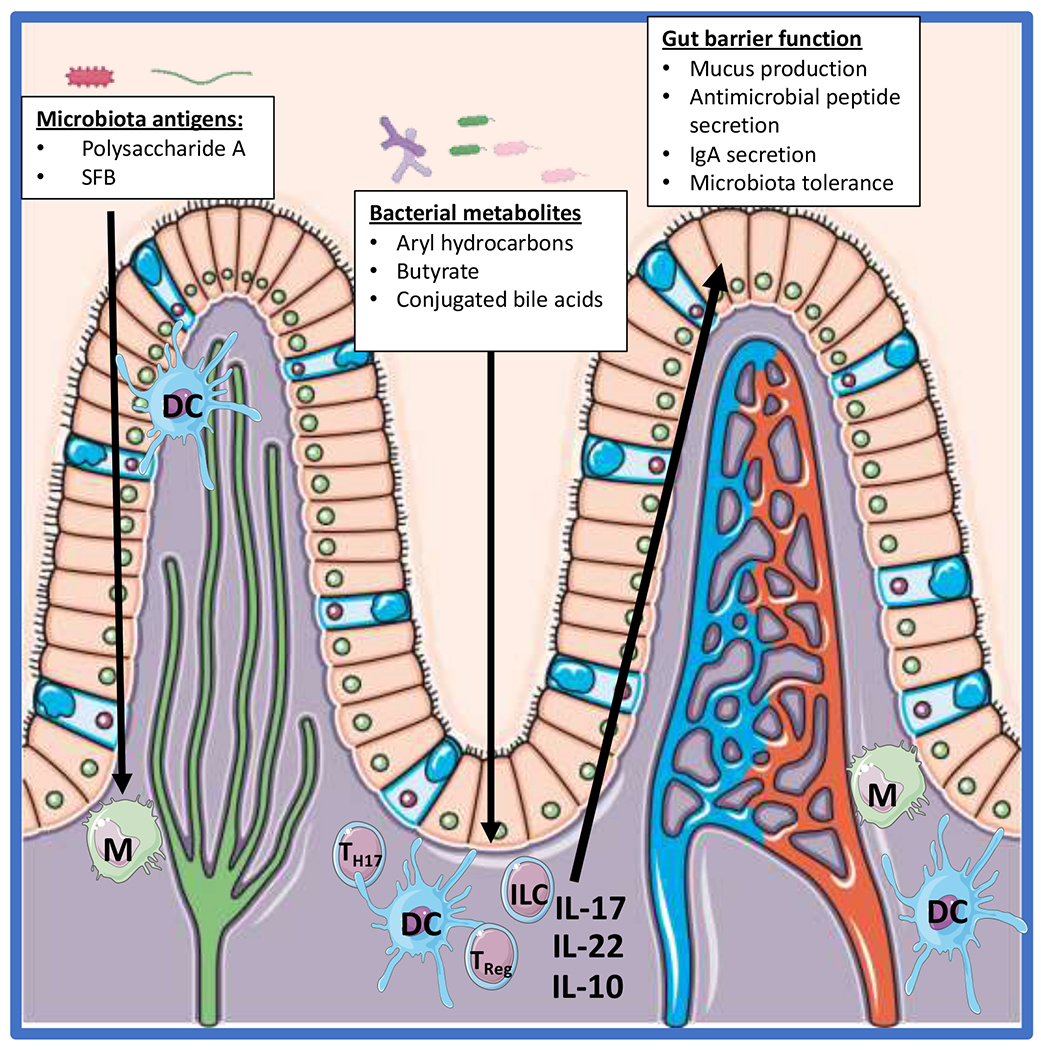

The intestinal microbiome shapes the host immune system through several mechanisms. Alterations in the microbiota composition have been shown to have profound impacts on the development of immune cell subsets including T-cells, B-cells, and macrophages.6,11 The microbiota influences the immune system via two main mechanisms: through the production of metabolites and the exposure of the host to bacterial components (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Host microbiota interaction and its impact on the immune system.

The immune cells within the intestinal tract interact with bacterial antigens from the microbiota and/or interact with metabolites produced by the microbiota. These interactions in turn alter the profile of the immune system which can alter how the host responds to pathogens and are responsible for maintaining the gut barrier. SFB = segmented filamentous bacteria, M = Macrophage, DC = dendritic cell, Treg = T regulatory cell, ILC = innate lymphoid cell.

The immune system is equipped with germ-line encoded pathogen recognition receptors (PRR) that not only play an essential role in host pathogen interaction by the innate immune system but are essential to how the host interacts with the microbiota. One of the earliest discoveries of the influence of microbiota antigens and its impact on the host was the role of polysaccharide A (PSA) from Bacteroidetes Fragilis and its influence on the host immune system12,13. It was determined that PSA interacts with TLR2 on DCs within the gut lamina propria which in turn increase IL-10 production by T cells and enhance peripheral T regulatory cells. Thereby the presence of Bacteroidetes Fragilis is associated with gut health and has been associated with maintaining immune tolerance to the microbiota. Another important host-microbiota antigen associated interaction occurs with Segmented Filamentous Bacteria (SFB)14. Presentation of SFB antigen by dendritic cells within the lamina propria result in the increased presence of Th17 cells within the intestine which in turn are essential for maintaining gut homeostasis through their ability to stimulate mucus production and antimicrobial peptide secretion, both of which are essential for maintaining the gut barrier15. In a similar light, several studies have demonstrated that depletion of the gut microbiota results in intestinal macrophages that have a more pro-inflammatory phenotype suggesting that the presence of microbiota antigens helps maintain tolerance of the lamina propria immune cells16–18.

Microbiota metabolites have also been shown to shape the host immune response in several manners19. SCFAs and butyrate are the most widely studied metabolites that have been shown to influence the host immune response. Butyrate has been demonstrated to impact the profile Treg cells, intestinal macrophages, and bone marrow derived macrophages16,20,21. Butyrate can function either by acting through G-protein coupled receptors22,23 or function as a histone deacetylase inhibitor16,24,25 both of which alter the gene expression profile of the aforementioned immune cells and impact how they respond to microbial stimuli. In addition to SCFAs, aryl hydrocarbons are produced by the microbiota and play an important role of in host-microbiota interactions26. Deficiency of aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) or aryl hydrocarbons results in alterations in the intestinal microbiota composition and reduction in antimicrobial peptide production27,28. In particular innate lymphoid cells within the gut rely on aryl hydrocarbons and AHR for their expansion and production of IL-2227. IL-22 expression by innate lymphoid cells is essential for the production of antimicrobial peptide secretion by the host. Conjugated bile acids represent another bacterial metabolite that have been demonstrated to impact the host immune response and will be discussed later on this review.

In summary, the depletion of the microbiota has been shown to alter how immune cells respond to infectious insults typically resulting in a pro-inflammatory phenotype.29 Maintaining a healthy intestinal microbiota and normal levels of SCFA result in a more tolerant immune system. Particularly, a healthy concentration of short chain fatty acids via their production by an intact microbiota can directly influence the functional profile of immune cells resulting in their improved ability to clear and eliminate pathogens.

Butyrate’s influence on gene expression profiles in both intestinal epithelial cells as well as immune cells has been established to occur through its ability to act as a histone deacetylase inhibitor.25 As a result, butyrate has also been shown to increase the microbiocidal activity of macrophages, enhance the activity of intestinal T-regulatory cells, and improve survival in the setting of bacterial pneumonia by aiding in resolution of inflammation.16,20,21,30

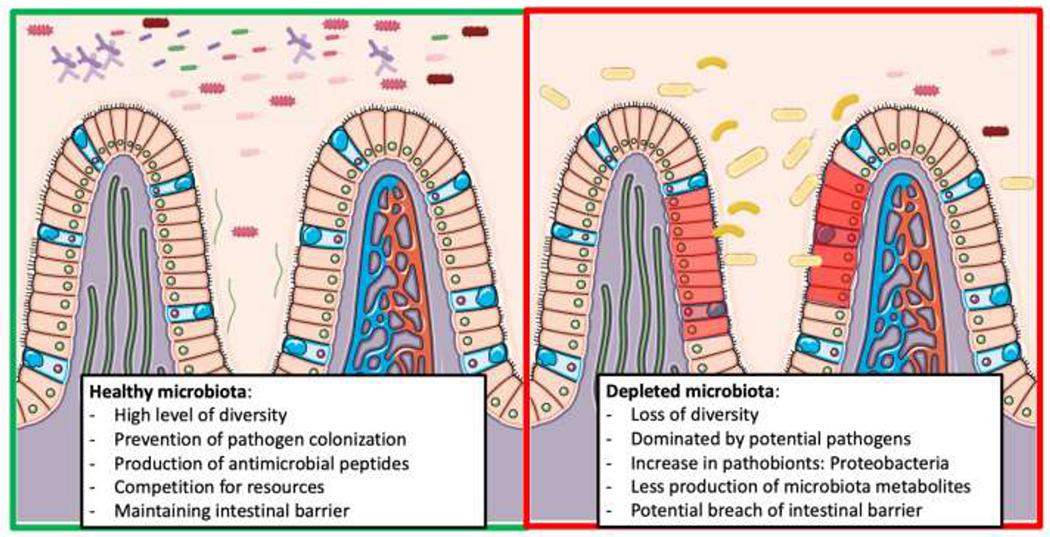

The intestinal microbiome also plays an essential role in combatting colonization of the epithelium by potential pathogens (Figure 2). The microbiota stimulates the production of IgA, defensins, and antibacterial peptides by the host which in turn inhibit colonization of potential pathogens.31 Bacteria associated with a healthy microbiome will also produce antimicrobial peptides, bacteriocins, targeting pathogens.32 Additionally, the bacteria within the microbiome can prevent pathogen colonization through competition for limited resources within a particular niche.33

Figure 2: Impact of sepsis/critical illness on the the microbiota and the role of the microbiota in preventing pathogen colonization.

Loss of microbiota diversity can lead to a rise in pathogen colonization and alter the intestinal barrier.

During critical illness, the healthy microbiome is replaced by a low-diversity pathobiome.10 This is likely a result of the loss of the health promoting microbiota through major alterations in the intestinal microenvironment due to both perturbations in host physiology due to the illness itself as well as due to the result of its treatment.34 Critical illness has routinely been shown to result in a loss of intestinal microbiota diversity and in turn a reduction in the SCFAs produced by the intestinal microbiota.35,36 When critical illness induced alterations to the microbiota are combined with the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics, the typical homeostasis between the host immune system and the intestinal microbiota is lost and the ability of the microbiota to prevent pathogen colonization is greatly impaired. These findings may explain why prior antibiotic exposure has been associated with increased risk for development of infectious complications and sepsis.37,38 In a retrospective study of 516 hospitals, prior admission with exposure to antibiotics was associated with a 65% increase in the likelihood of developing severe sepsis within 90 days of discharge.37 In a similar manner, a prospective study found that prior antibiotic exposure was associated with a significant increase in the incidence of postoperative complications.38 Both of these studies implicate that antibiotic induced alterations to the microbiota predispose patients to developing infectious complications and sepsis.

These compounding effects of host physiology in the setting of critical illness and antibiotic exposure may also explain the phenomenon of late-onset sepsis. The improvement of our ability to recognize and treat acute infection as well as our ability to manage and treat complex medical conditions has resulted in a major shift in patients suffering and dying from sepsis.39 The term late onset sepsis refers to the delay in mortality we are now seeing in patients who are admitted to the hospital with sepsis. Over two-thirds of patients diagnosed with sepsis are dying after 72 hours of admission. The majority of these deaths occur after several weeks in the hospital, and amongst the patients with a delay in mortality, the most common cause of death is persistent organ failure or nosocomial infection.40 The most common underlying cause of death in patients with sepsis is an underlying chronic condition (cancer, chronic heart disease, chronic lung disease).39 The underlying pathology of late onset sepsis may be related to the compounding impact of prolonged medical treatments, chronic illness, and critical care on the microbiota. Prolonged exposure to multiple stressors such as poor nutrition, antibiotics, or the physiologic stress of critical illness itself, can result in increased pathogen colonization and susceptibility to infection. The ability of the intestinal microbiome to recover in the face of these insults may directly influence the course and outcome of sepsis by allowing the health-promoting effects of the microbiota to maintain the host’s ability to prevent pathogen colonization and the host’s immune systems’ ability to clear infections.

The immunophenotype of sepsis and the microbiology of pathogens causing immunosuppression

The immune response during sepsis remains poorly understood and attempts have been made to describe associated immunophenotypes26. The immunophenotype studies broadly focus on cell surface markers for phenotype characterization of the immune response during sepsis. A more recent study utilized single cell RNA sequencing to understand immunophenotypes associated with urosepsis and found a distinct population of monocytes that could distinguish patients with sepsis43. In general, the immunophenotype associated with sepsis includes impaired antigen presentation by monocytes as well as increased expression of inhibitory ligands PD-1 and PD-L1. Consistent with these findings, a postmortem study of patients with sepsis reveals evidence of depleted effector cells and increased expression of suppressive ligands consistent with immunosuppression.44 This has led to a focus on determining the etiology of the immunosuppression seen in sepsis and attempts have been made to reverse the immunosuppressive phenotype associated with the septic immune response.45 Many of these studies and theories fail to account for the ability of the causative pathogens themselves to subvert the host immune response and contribute to the immunophenotype associated with sepsis.46,47 Most septic patients have had a prolonged hospital course resulting in multiple antibiotic courses which significantly shifts their microbiome into a “pathobiome” of healthcare adapted pathogens.10 The composition, membership and function of the intestinal microbiome plays a key and causative role in the host immune response to infection was demonstrated in a recent mouse study of sepsis due to cecal ligation and puncture (CLP).45 In this study, genetically identical strains of mice obtained from different vendors had drastically different outcomes and expressed distinct immunophenotypes when subjected to CLP. The difference in response to CLP was attributed to differences in the microbiome as a result of being bred, raised and housed by different vendors.

To date, numerous studies have demonstrated the impact of the intestinal microbiota on the host response to pathogens.48 The microbiota directed immune response to pathogens has been demonstrated in the microbiota’s ability to influence myeloid cell development necessary for pathogen clearance, the microbiota directly increasing antiviral gene expression necessary for clearance of influenza, and the impact of viral infections on the intestinal microbiota that leave the host susceptible to secondary bacterial infection.49–52 As we begin to understand the emerging role of the microbiome in the occurrence, course and outcome of sepsis, it is becoming increasingly clear that alterations in the microbiome have a profound impact on the host immune response to infection.50,53–55 When the microbiota’s influence on the host’s ability to clear pathogens is viewed in conjunction with the distinct immunophenotypes associated with sepsis and septic outcomes, a microbiota dependent immunophenotype could potentially connect these two observations, and provide a deeper understanding of sepsis that is defined by host, microbiota, and pathogen interactions.41,43

The influence of the microbiome on organ dysfunction in sepsis

In the septic response, each organ system is affected in different, but significant ways. An organ’s response to the inflammatory burden may cause irreparable damage and lead to failure. Because the microbiome is tied so closely to the immune response and inflammatory burden, an individual’s microbiome can mediate an organ system’s response to sepsis.

The role of the gut-brain axis and the microbiota in septic encephalopathy

A large body of research has continued to unlock the dynamic interaction between the intestine and the nervous system which is best displayed by the complex enteric nervous system.56 The enteric nervous system is influenced by hypotholamic-pituitary axis (HPA), the autonomic nervous system, and the sympatho-adrenal axis. The communication from the brain to the gut has a direct impact on intestinal motility and digestion. Additionally, the gut has the ability to communicate with the nervous system via the enterochromaffin cells within the intestine which can signal to the central nervous system via direct interaction with enteric nerves.56 Additionally, alterations to the microbiota can result in significant behavioral changes to mice that correlate with changes to levels of neurotransmitters, particularly serotonin, induced by the microbiota.57,58 Additionally, bacterial metabolites have been shown to directly impact the development of neuroinflammation in the models of Parkinson’s disease.59 Given the relationship between the gut microbiota and chronic neurological and psychological diseases, it is feasible that similar microbiota associated mechanisms may influence the acute encephalopathy seen in sepsis.

Sepsis is known to lead to a dysregulated immune system with the release of inflammatory elements that cause neuroinflammation and brain dysfunction.60 Elevated levels of inflammatory cytokines such as TNFa and HMGB1 have been shown to result in a significant increase in neuroinflammation and neuronal cell apoptosis within the brain in the setting of sepsis60,61. The HPA has been found to be significantly altered in the setting of sepsis resulting In decreased levels of glucocorticoids and has led to the use of glucocorticoids in the treatment of sepsis.62,63 Additionally, the HPA plays an important role in the resolution of inflammation and dysregulation of the HPA may result in decreased glucocorticoid production and loss of inflammatory resolution. At this point it is clear that the increased inflammatory response associated with alterations in the microbiota may contribute to the neuroinflammation associated with sepsis; however, the microbiota may also alter the HPA and in turn impair the nervous systems ability to resolve inflammation and further perpetuate the neuronal inflammation associated with septic encephalopathy. For example, using murine models, Li and colleagues showed that indeed, a depleted microbiome contributes to worsened septic encephalopathy whereas microbiome restoration via a fecal transplant improves brain activity and decreases inflammatory mediators.64

The gut-liver axis and the microbiota in septic induced liver dysfunction

Similarly, liver injury in sepsis is influenced by the state of the microbiome. As there is direct vascular communication between the intestinal tract and biliary system, inflammatory mediators created by the gut microbiota pass easily to the liver. In order to understand the role of microbiota’s role in liver dysfunction in the setting of sepsis it is important to understand the dynamic relationship that occurs between the liver-gut-microbiota axis at steady state.

The communication between the liver and the gut has long been understood to occur between both the portal and systemic circulation.65 The most studied gut-liver communication is the enterohepatic circulation of bile acids which describes the production of primary bile acids (cholic acid and chenodeoxycholic acid) by the liver, their excretion into the gut for digestion of dietary fats, and their reabsorption within the intestines.65 Approximately 95% of bile acids are reabsorbed in the terminal ileum of the small intestine and transported back to the liver while the remaining 5% are converted to secondary bile acids by the colonic microbiota. Secondary bile acids, most commonly deoxycholic acid and lithochocholic acid, can then be reabsorbed directly into the portal system and returned to the liver. Secondary bile acids also have the ability to alter bile acid synthesis in the liver via binding to the nuclear Farnesoid X receptor (FXR) and FXR also has been shown to play a major role in regulating glucose and lipid metabolism of the host66–69. Additionally, FXR signaling has been shown to result in the production of antimicrobial peptides which in turn are essential for controlling gut permeability, preventing pathogen colonization, and maintaining intestinal barrier function.70 One example of bile acids inhibiting pathogen colonization is the secondary bile acid deoxycholic acid inhibiting C. difficile colonization and outgrowth71. In addition to impacting pathogen colonization, the bile acid microbiota interaction offers a mechanism by which the microbiota manipulates the host immune system. Studies have demonstrated that microbiota involved in bile acid conjugation directly impact intestinal Treg and Th17 cells, and loss of these microbiota species greatly impairs their development72,73. The bile acid and gut microbiota interaction provides another mechanism in which the host and gut microbiota engage in a symbiotic relationship that further impacts host susceptibility to pathogen colonization and immune systems’ ability to respond to infection.

In the setting of alcoholic and non-alcoholic liver disease, there is a known impact of intestinal permeability which can lead to further increase in the liver inflammation. Additionally, alterations in levels of primary bile acids in turn can impact FXR signaling which further impacts the production of bile acids, host metabolism, and production of antimicrobial peptides as described above.65 Despite the lack of consensus defining liver injury in sepsis, experimental data show that the liver is injured in early and late sepsis.74 In the septic state, or during other causes of increased gut permeability, microbe-associated molecular patterns and pathogen-associated molecular patterns are translocated at higher rates, adding to injury caused by inflammatory cytokines. Different microbiota strains affect this response by producing more virulent and inflammatory molecules. Gong and colleagues have shown that there is a disparate intestinal microbiome present in mice who are more sensitive to sepsis-induced liver injury versus mice that are resistant.75 When transplanted to new mice, these microbiome profiles conferred the same response: sensitivity to septic liver damage or protection from it.75 Given the dynamic relationship between the gut-liver-microbiota axis and its impact on the host immune system, it is clear that sepsis induced alterations to the microbiota can contribute to liver failure and liver failure can result in further alterations to the gut microbiota that result in impairment of the host immune system and increased pathogen colonization.

The role of the gut-lung axis and the microbiota in septic respiratory failure

Like encephalitis and liver injury, the lungs are affected by the microbiota in a so-called gut-lung axis. Through a complex set of interactions, alterations in the makeup of the microbiota influence immune and inflammatory balance in the lungs.76 Early treatment with antibiotics has been associated with the development of allergic airway disease implicating the intestinal microbiota in shaping the local immune cells of the lung.77 Previously thought to be sterile, the lung is known to harbor its own microbiota.78 However, the overall biomass of the lung microbiota is significantly lower than that of the intestines and colonization is believed to be transient for most organisms.79 Similar to the impact of the intestinal microbiota on the immune system, the lung microbiota is associated with alterations within the lung resident immune cells. Specific lung organisms such as non-pathogenic S. pneumoniae has been implicated in suppressing allergic airway disease in a Treg dependent manner.80 Studies of lungs following lung-transplant have shown that Firmicute and Proteobacteria dominant lung microbiota are associated with a more pro-inflammatory lung phenotype whereas Bacteroidetes dominant lung microbiota are associated with a tissue remodeling phenotype.81 These microbiota induced lung immune phenotypes may explain why changes in both the lung and intestinal microbiome of patients have been linked to the development of COPD.82 Additionally, some studies have associated the use of proton pump inhibitors, which alter the normal flora of the stomach, with an increase in pneumonia.83 Compositional changes to the microbiota both in the lung and gut can have downstream implications on respiratory function. The intestinal microbiota can exert its effects on the lung via its impact on the host immune system. In particular, fiber-induced alterations to both the lung and gut microbiota of mice resulting in increased resistance to allergic airway disease.84 Additionally, segmented filamentous bacteria (SFB) colonization has been shown to increase Th17 cells within the lung and protect against S. pneumonia lung infections.85

This relationship between the microbiota and the lungs persists in the septic state: a systematic review has shown that when administered to critically ill patients, probiotic supplements that promote favorable intestinal flora may actually help lower the incidence of ventilator associated pneumonia.86,87 A recent study also revealed that an association between the development of acute respiratory distress syndrome in septic patients with the enrichment of the lung microbiota with gut microbes.88 Further studies found that both increase in lung microbiota biomass and enrichment of the lung microbiota with gut microbes was associated with prolonged respiratory failure and duration of mechanical ventilation.89 The role of the gut microbiota in sepsis induced respiratory failure has been taken a step further in animal models. A depleted microbiome leads to faster mortality and higher pulmonary bacterial loads in mice after intranasal bacterial inoculation. Fecal transplant in these mice was able to confer protection against pulmonary infection.90

The organ failure associated with sepsis is a byproduct of the dysregulated inflammatory response which can directly damage end organs; however, the organ damage may also be related to alterations to the intestinal microbiota which can impact distant organs via their associated gut-axis. The impact of sepsis on these organs can further perpetuate the alterations to the microbiota associated with sepsis. Microbiota directed therapies in sepsis may mitigate the inflammatory insult and aid in the maintenance of function of end organs via both immune system dependent and independent mechanisms.

Fecal transplant, microbiota-directed therapies, and sepsis

Fecal microbiota transplant is a therapeutic method of reintroducing healthy microbes into the gastrointestinal tract via the administration of healthy donor feces. The method has been used for centuries, albeit in varying forms, to treat intestinal disorders such as food poisoning and dysentery.91 The earliest reported use of fecal transplants in medicine comes from China over 1700 years ago. In ancient China, ‘yellow soup’ was reportedly used to successfully treat food poisoning.92 Additionally, Bedouin groups would consume camel feces as a means of treating bacterial dysentery.93 Although he did not directly study fecal transplant, a more scientific inquiry of the microbiota was undertaken by Russian scientist and Nobel Laureate, Elie Metchnoff who was inspired by the longevity of Bulgarian farmers despite their poor living conditions.94 Metchnikoff hypothesized that by increasing the number of beneficial microbes living within the colon, one could improve health and longevity.94 These microbiome centric ideas continued to spread amongst European physicians in the 18th century and was highlighted by an entire book dedicated to therapeutic potential of human feces authored by Christian Paullini.95

More recently, FMT has seen a resurgence as a therapy to treat antibiotic-resistant Clostridium difficile infections (CDI). With the discovery of and increased use of antibiotic in modern medicine, visionaries such as Stanley Falkow reported concerns regarding the impact of antibiotics on the native gut flora and attempted to provide fecal transplant to restore the normal gut flora after antibiotic exposure.93 This idea eventually led to the successful treatment of pseudomembranous colitis seen in CDI in the late 1950s by Dr. Eiseman’s group at the University of Colorado.96 Several systematic reviews and society guidelines now recommend FMT for the treatment of resistant or recurrent CDI.97–99 In certain instances, FMT has actually been shown to be more successful than vancomycin at curing CDI.100

As FMT has gained clinical relevance, its use has been expanded beyond CDI. Patients with a range of immune modulating disorders are susceptible to intestinal bacterial dysregulation. Investigators have increasingly used FMT as a potential therapeutic option in these patients, particularly in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. FMT has proved beneficial at aiding recovery in immunotherapy colitis as well as eradication of colonized antibiotic resistant bacteria in patients with hematologic malignancies.101,102 Outside of the oncology realm, the PROFIT trial is currently examining the feasibility of FMT in patients with advanced cirrhosis and determining the effect of FMT on the global inflammatory burden of these patients.103 The increasing importance of the microbiota in health has led to further attempts to treat varying health conditions including autoimmune disease, metabolic syndromes, and sepsis.104

The goal of fecal microbiota transplant is to restore the normal microbiota structure and function to a healthy state. In doing this, the host metabolism, immune system, and ability to prevent colonization with pathogens will theoretically improve. FMT has been shown repeatedly to be an effective treatment for refractory C. difficile infections (CDI).105 It is believed that FMTs effectiveness is related several mechanisms including restoration of the normal microbiota diversity, outcompeting the offending Clostridium difficile species, restoring secondary bile acids that inhibit C. difficile germination, and directly inhibiting C. difficile growth.106 When it comes to engraftment of FMT, it is not clear the exact mechanism by which specific bacteria species within the FMT are able to engraft within the host; however, studies modeling microbiota engraftment in patients with CDI have shown that specific strains will engraft in a manner specific to bacterial species present in the recipient pre-FMT microbiota and specific to species present within the bacteria of the donor FMT.107 Further studies need to be done in order to understand the dynamics of engraftment associated with FMT.

In addition to the use of FMT for C. difficile, FMT has been shown to be effective at restoring fecal microbiota in the setting of bone marrow transplant (BMT).108 BMT patients are exposed to prolonged courses of antibiotics resulting in significant intestinal dysbiosis. By providing an autologous fecal microbiota transplant (aFMT) to BMT patients, the microbiota and microbiota-associated SCFAs can be restored to levels similar to pre-antibiotic treatments. The use of FMT in BMT has resulted in a reduction in colonization with antibiotic resistant pathogens and an improvement in outcomes.109–111 In support of these findings in BMT patients, aFMT transplant has been found to be the most expeditious way to restore native microbiota following antibiotic exposure.112 By restoring the microbiota from a diseased state to a healthy state, the microbiota can resume normal function and help maintain an equilibrium with the host.

Since the microbiome is disrupted during sepsis, contributing to multisystem organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS), researchers and clinicians have turned to FMT as an adjunct to sepsis management. In fact, FMT has been used successfully in several septic patients. In 2015, Li and colleagues published the first case report of FMT utilized to treat severe sepsis. Their report describes a patient with persistent sepsis and watery diarrhea for 30 days after a vagotomy, which persisted despite antibiotics and supportive care. Analysis revealed that the patient’s microbiome was severely disrupted. After donor FMT, the patient’s sepsis and diarrhea resolved. Repeat molecular testing showed that the patient’s microbiome had been reconstituted with healthy bacteria.113 In 2016, Wei and colleagues reported a similar series: two patients that were initially admitted for stroke management who developed septic shock, MODS, and watery diarrhea and were successfully treated with donor FMT.114 Wurm et al. has presented the most recent report of FMT use in septic patients. Their series includes three patients with SIRS physiology and large volume, persistent diarrhea associated with steroid and antibiotic use. One of the patients improved with cessation of antibiotics and a second succumbed to the sepsis and MODS. In the third, a FMT was performed after 42 days of diarrhea and SIRS with rapid resolution of the symptoms.115 From these cases, it seems that FMT may be a successful treatment at attenuating the inflammation and immunosuppression that occurs during the sepsis episode, particularly when the infections seem to originate from some type of intestinal disruption. One of the major limitations preventing more widespread use of FMT is the need for cessation of antibiotics.116 It is obviously difficult to obtain consensus on removal of antibiotics in a critically ill patient as they are often thought of as a crucial part of the treatment plan. Additionally, the results of FMT must be carefully interpreted in many of these cases, the inflammatory markers and the volume of diarrhea was decreasing prior to FMT. It should be noted that other microbiota-directed therapies exist including: prebiotics, probiotics, and synbiotics. Prebiotics attempt to provide a substrate such as fiber as a source for health promoting bacteria to grow and thrive.117.

The beneficial impact of SCFAs on the immune system would make it logical that prebiotics may provide some benefit in the setting of sepsis. However, no direct study has been done evaluating the use of fiber in the setting of sepsis, although studies have demonstrated the ability of prebiotics to reduce infection in infants and currently the Society of Critical Care Medicine recommends the supplementation of fiber to all patients receiving enteral tube feeds118,119. Probiotics offer a microbiota directed therapy by providing individual colonies of health promoting bacteria in hopes of altering the microbiota. In the setting of infection, probiotics have only been found to be beneficial in a small subset of patients.86,87 Contrary to these beneficial effects, probiotics may impede the ability of refaunation of the intestinal microbiota following antibiotic therapy.112 Finally, the use of synbiotics combines a health promoting substrate such as fiber with the delivery of health promoting bacteria. Synbiotics have been shown to lower the rate of enteritis and ventilator associated pneumonia in patients with sepsis and have been shown to prevent the development of neonatal sepsis120,121. All of these microbiota-directed therapies provide insight to the ability of the microbiota to aid in improving response to infection. Further understanding of how these therapies shape the host microbiota and improve response to infection in the setting of sepsis need to be conducted; however, microbiota-directed therapies provide an exciting new avenue of potential treatments for septic patients.

Mechanism of FMT in sepsis

Our lab has recently demonstrated the ability of FMT to rescue mice from gut derived sepsis and bacterial peritonitis. Utilizing a four-member pathogen community (Enterococus Faecalis, Klebsiella Oxytoca, Serratia Marcescens, and Candida Albicans) isolated from a critically ill patient dying from sepsis, two separate animal models demonstrated the efficacy of FMT to restore the host immune system and result in recovery from lethal infection. In the gut derived sepsis model, the four-member pathogen community was injected into the cecum of mice after the mice underwent a partial hepatectomy. The stress from surgical injury resulted in dissemination of the pathogen community and death of the mice. The mortality was reversed with the administration of FMT from the cecum of a healthy mouse. To further understand the mechanism, mice were injected intraperitoneally with the 4-member pathogen community and subsequently rescued with FMT. Despite a difference in survival seen with administration of a FMT, intestinal microbiota structure was unchanged by administration of FMT. Functional studies revealed FMT resulted in an increase in butyrate producing bacteria. On the host side, genetic studies revealed that the pathogen community suppressed IRF3 expression, an innate immune pathway necessary for TLR signaling, and the expression of IRF3 was in turn restored by FMT. When IRF3 was deleted from the mouse model by genetically knocking it out, the FMT was no longer effective in rescuing mice from lethal bacterial peritonitis indicating that FMT was working by altering IRF3 expression. These studies reveal that FMT can alter the systemic immune response to infection by increasing the abundance of butyrate producing bacteria, which in turn restore IRF3 expression and clearance of the causative pathogens of the sepsis response.122

Complications of FMT and risk modification

Using FMT consisting of living microorganisms in critically ill, septic patients is not without risk especially considering the altered gut barrier function, co-morbidities and dyregulated immune response variability among this group of patients. The current rates of complication in the setting of CDI are low; however, several cases of death from aspiration, toxic megacolon, and most recently the development of MDR bacteremia after FMT have occurred and should result in some degree of pause.104,123 In a similar manner, a recent report found six ICU patients treated with probiotics developed subsequent Lactobacillus bacteremia.124 We currently do not fully understand which species of bacteria will engraft after FMT nor do we have an adequate method of screening donor samples for potential pathogenic bacteria. Therefore, delivering FMT in the setting of critical illness could result in significant and lethal complications. Several strategies for reducing the risk of FMT have been proposed: ensuring adequate donor fecal bacterial diversity, inclusion of butyrate-producing species, processing samples in anaerobic conditions, and targeted modification of screened and processed donor microbiota.64 Until we understand the exact mechanisms by which FMT can alter the immune system in the setting of sepsis to allow us to deliver therapy in a more controlled manner, FMT for sepsis should remain a theoretical and experimental approach to sepsis.

Conclusion

The intestinal microbiome plays an important role in the pathophysiology of sepsis as the microbiome shapes both the immune system and the consortia of pathogens that can emerge during the course of treatment. Fecal microbiota transplant can prevent pathogen colonization, restore the host immune system and drive clearance of pathogens in the setting of experimental sepsis in mice. Yet, FMT has inherent risks when administered to critically patients. Therefore, improved understandings of the mechanism by which an FMT can shape the host immune response and result in recovery in the setting of sepsis is needed. Future microbiota directed therapies may consists of restoration of bacterial metabolites such as butyrate or the delivery of specific bacterial communities capable of restoring specific microbiota functions necessary in restoring the host immune response and recovery from sepsis.

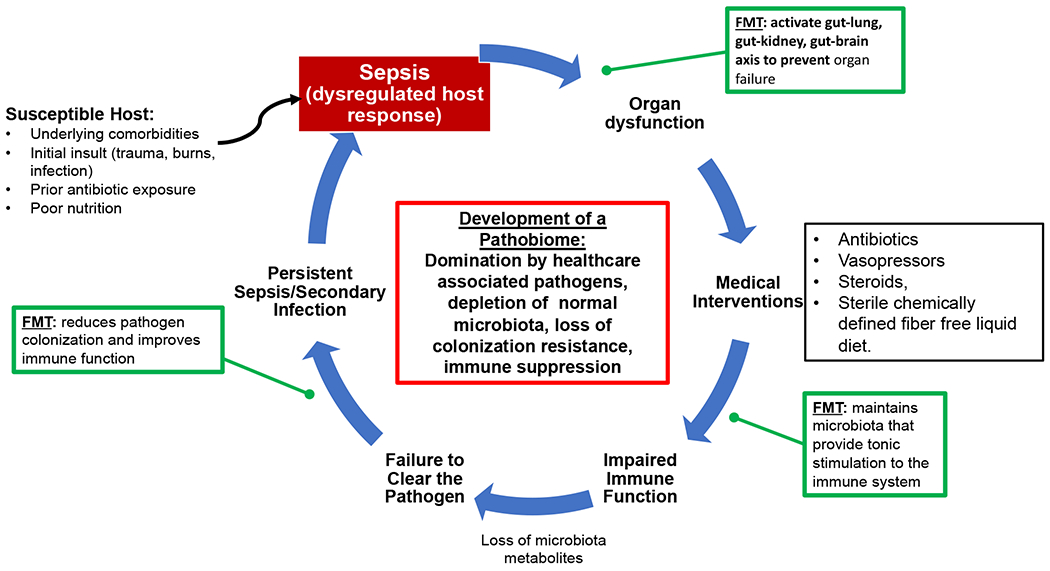

Figure 3: The potential role of microbiota directed therapies and FMT on sepsis.

The impact of sepsis on the microbiota and in turn the host immune system can be a perpetual cycle. Microbiota directed therapies such as FMT may one day provide points of interventions during the course of sepsis.

Acknowledgements

All authors have read the journal’s policy on conflicts of interest and the journal’s authorship agreement. Individual conflicts of interest are listed below:

RK – no conflicts of interest

JA – co-founder of Covira Surgical and is past consultant with Applied Medical. JA is also supported by a grant from National Institutes of Health (5R01GM062344-18)

JC – no conflicts of interest

JD – no conflicts of interest

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Gilbert JA, Blaser MJ, Caporaso JG, Jansson JK, Lynch SV, Knight R. Current understanding of the human microbiome. Nat Med. 2018;24(4):392–400. doi: 10.1038/nm.4517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Young VB. The role of the microbiome in human health and disease: an introduction for clinicians. BMJ. 2017;356:j831. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allaband C, McDonald D, Vázquez-Baeza Y, et al. Microbiome 101: Studying, Analyzing, and Interpreting Gut Microbiome Data for Clinicians. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol Off Clin Pract J Am Gastroenterol Assoc. 2019;17(2):218–230. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.09.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klassen JL. Defining microbiome function. Nat Microbiol. 2018;3(8):864–869. doi: 10.1038/s41564-018-0189-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sonnenburg ED, Sonnenburg JL. Starving our Microbial Self: The Deleterious Consequences of a Diet Deficient in Microbiota-Accessible Carbohydrates. Cell Metab. 2014;20(5):779–786. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.07.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hooper LV, Littman DR, Macpherson AJ. Interactions Between the Microbiota and the Immune System. Science. 2012;336(6086):1268–1273. doi: 10.1126/science.1223490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heintz-Buschart A, Wilmes P. Human Gut Microbiome: Function Matters. Trends Microbiol. 2018;26(7):563–574. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2017.U.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, et al. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA. 2016;315(8):801. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Casadevall A, Pirofski LA. Host-pathogen interactions: redefining the basic concepts of virulence and pathogenicity. Infect Immun. 1999;67(8):3703–3713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alverdy JC, Krezalek MA. Collapse of the Microbiome, Emergence of the Pathobiome, and the Immunopathology of Sepsis: Crit Care Med. 2017;45(2):337–347. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rooks MG, Garrett WS. Gut microbiota, metabolites and host immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2016;16(6):341–352. doi: 10.1038/nri.2016.42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mazmanian SK, Liu CH, Tzianabos AO, Kasper DL. An Immunomodulatory Molecule of Symbiotic Bacteria Directs Maturation of the Host Immune System. Cell. 2005;122(1):107–118. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang Q, McLoughlin RM, Cobb BA, et al. A bacterial carbohydrate links innate and adaptive responses through Toll-like receptor 2. J Exp Med. 2006;203(13):2853–2863. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ivanov II, Atarashi K, Manel N, et al. Induction of Intestinal Th17 Cells by Segmented Filamentous Bacteria. Cell. 2009;139(3):485–498. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.09.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Okumura R, Takeda K. Roles of intestinal epithelial cells in the maintenance of gut homeostasis. Exp Mol Med. 2017;49(5):e338–e338. doi: 10.1038/emm.2017.20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chang PV, Hao L, Offermanns S, Medzhitov R. The microbial metabolite butyrate regulates intestinal macrophage function via histone deacetylase inhibition. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2014;111(6):2247–2252. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1322269111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim M, Galan C, Hill AA, et al. Critical Role for the Microbiota in CX3CR1+ Intestinal Mononuclear Phagocyte Regulation of Intestinal T Cell Responses. Immunity. 2018;49(1):151–163.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.05.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bain CC, Bravo-Blas A, Scott CL, et al. Constant replenishment from circulating monocytes maintains the macrophage pool in the intestine of adult mice. Nat Immunol. 2014;15(10):929–937. doi: 10.1038/ni.2967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Skelly AN, Sato Y, Kearney S, Honda K. Mining the microbiota for microbial and metabolite-based immunotherapies. Nat Rev Immunol. 2019;19(5):305–323. doi: 10.1038/s41577-019-0144-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schulthess J, Pandey S, Capitani M, et al. The Short Chain Fatty Acid Butyrate Imprints an Antimicrobial Program in Macrophages. Immunity. 2019;50(2):432–445.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.12.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arpaia N, Campbell C, Fan X, et al. Metabolites produced by commensal bacteria promote peripheral regulatory T-cell generation. Nature. 2013;504(7480):451–455. doi: 10.1038/nature12726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vinolo MAR, Rodrigues HG, Hatanaka E, Sato FT, Sampaio SC, Curi R. Suppressive effect of short-chain fatty acids on production of proinflammatory mediators by neutrophils. J Nutr Biochem. 2011;22(9):849–855. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2010.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith PM, Howitt MR, Panikov N, et al. The Microbial Metabolites, Short-Chain Fatty Acids, Regulate Colonic Treg Cell Homeostasis. Science. 2013;341(6145):569–573. doi: 10.1126/science.1241165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Furusawa Y, Obata Y, Fukuda S, et al. Commensal microbe-derived butyrate induces the differentiation of colonic regulatory T cells. Nature. 2013;504(7480):446–450. doi: 10.1038/nature12721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fellows R, Denizot J, Stellato C, et al. Microbiota derived short chain fatty acids promote histone crotonylation in the colon through histone deacetylases. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):105. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02651-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shinde R, McGaha TL. The Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor: Connecting Immunity to the Microenvironment. Trends Immunol. 2018;39(12):1005–1020. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2018.10.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li Y, Innocentin S, Withers DR, et al. Exogenous Stimuli Maintain Intraepithelial Lymphocytes via Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Activation. Cell. 2011;147(3):629–640. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.09.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kiss EA, Vonarbourg C, Kopfmann S, et al. Natural Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Ligands Control Organogenesis of Intestinal Lymphoid Follicles. Science. 2011;334(6062):1561–1565. doi: 10.1126/science.1214914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blander JM, Longman RS, Iliev ID, Sonnenberg GF, Artis D. Regulation of inflammation by microbiota interactions with the host. Nat Immunol. 2017;18(8):851–860. doi: 10.1038/ni.3780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chakraborty K, Raundhal M, Chen BB, et al. The mito-DAMP cardiolipin blocks IL-10 production causing persistent inflammation during bacterial pneumonia. Nat Commun. 2017;8(1):13944. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pickard JM, Zeng MY, Caruso R, Nύήez G. Gut microbiota: Role in pathogen colonization, immune responses, and inflammatory disease. Immunol Rev. 2017;279(l):70–89. doi: 10.1111/imr.12567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roelofs KG, Coyne MJ, Gentyala RR, Chatzidaki-Livanis M, Comstock LE. Bacteroidales Secreted Antimicrobial Proteins Target Surface Molecules Necessary for Gut Colonization and Mediate Competition In Vivo. mBio. 2016;7(4):e01055–16, /mbio/7/4/e01055–16.atom doi: 10.1128/mBio.01055-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sorbara MT, Pamer EG. Interbacterial mechanisms of colonization resistance and the strategies pathogens use to overcome them. Mucosal Immunol. 2019;12(l):1–9. doi: 10.1038/s41385-018-0053-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zaborin A, Smith D, Garfield K, et al. Membership and Behavior of Ultra-Low-Diversity Pathogen Communities Present in the Gut of Humans during Prolonged Critical Illness. Clemente J, Dominguez Bello MG, eds. mBio. 2014;5(5):e01361–14. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01361-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Akrami K, Sweeney DA. The microbiome of the critically ill patient: Curr Opin Crit Care. 2018;24(l):49–54. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0000000000000469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yamada T, Shimizu K, Ogura H, et al. Rapid and Sustained Long-Term Decrease of Fecal Short-Chain Fatty Acids in Critically III Patients With Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome. J Parenter Enter Nutr. 2015;39(5):569–577. doi: 10.1177/0148607114529596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baggs J, Jernigan JA, Halpin AL, Epstein L, Hatfield KM, McDonald LC. Risk of Subsequent Sepsis Within 90 Days After a Hospital Stay by Type of Antibiotic Exposure. Clin Infect Dis Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am. 2018;66(7):1004–1012. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guidry CA, Shah PM, Dietch ZC, et al. Recent Anti-Microbial Exposure Is Associated with More Complications after Elective Surgery. Surg Infect. 2018;19(5):473–479. doi: 10.1089/sur.2018.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rhee C, Jones TM, Hamad Y, et al. Prevalence, Underlying Causes, and Preventability of Sepsis-Associated Mortality in US Acute Care Hospitals. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(2):el87571. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.7571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Daviaud F, Grimaldi D, Dechartres A, et al. Timing and causes of death in septic shock. Ann Intensive Care. 2015;5(1):16. doi: 10.1186/sl3613-015-0058-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ferreira da Mota NV, Brunialti MKC, Santos SS, et al. Immunophenotyping of Monocytes During Human Sepsis Shows Impairment in Antigen Presentation: A Shift Toward Nonclassical Differentiation and Upregulation of FCyRi-Receptor. SHOCK. 2018;50(3):293–300. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000001078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rimmelé T, Payen D, Cantaluppi V, et al. Immune Cell Phenotype and Function in Sepsis: SHOCK. 2016;45(3):282–291. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reyes M, Filbin MR, Bhattacharyya RP, et al. An immune-cell signature of bacterial sepsis. Nat Med. 2020;26(3):333–340. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0752-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Boomer JS, To K, Chang KC, et al. Immunosuppression in Patients Who Die of Sepsis and Multiple Organ Failure.JAMA. 2011;306(23):2594. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fay KT, Klingensmith NJ, Chen C- W, et al. The gut microbiome alters immunophenotype and survival from sepsis. FASEB J Off Publ Fed Am Soc Exp Biol. 2019;33(10):11258–11269. doi: 10.1096/fj.201802188R [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Riquelme SA, Liimatta K, Wong Fok Lung T, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa Utilizes Host-Derived Itaconate to Redirect Its Metabolism to Promote Biofilm Formation. Cell Metab. Published online May 2020:S1550413120301996. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2020.04.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wu L Recognition of Host Immune Activation by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Science. 2005;309(5735):774–777.doi: 10.1126/science.1112422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thaiss CA, Zmora N, Levy M, Elinav E. The microbiome and innate immunity. Nature. 2016;535(7610):65–74. doi: 10.1038/naturel8847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gorjifard S, Goldszmid RS. Microbiota—myeloid cell crosstalk beyond the gut. J Leukoc Biol. 2016;100(5):865–879. doi: 10.1189/jlb.3RI0516-222R [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Abt MC, Osborne LC, Monticelli LA, et al. Commensal Bacteria Calibrate the Activation Threshold of Innate Antiviral Immunity. Immunity. 2012;37(1):158–170. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.04.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Haak BW, Littmann ER, Chaubard J- L, et al. Impact of gut colonization with butyrate producing microbiota on respiratory viral infection following allo-HCT. Blood. Published online April 19, 2018:blood-2018–01-828996. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-01-828996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sencio V, Barthelemy A, Tavares LP, et al. Gut Dysbiosis during Influenza Contributes to Pulmonary Pneumococcal Superinfection through Altered Short-Chain Fatty Acid Production. Cell Rep. 2020;30(9):2934–2947.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kamada N, Kim Y- G, Sham HP, et al. Regulated Virulence Controls the Ability of a Pathogen to Compete with the Gut Microbiota. Science. 2012;336(6086):1325–1329. doi: 10.1126/science.1222195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Khosravi A, Yanez A, Price JG, et al. Gut Microbiota Promote Hematopoiesis to Control Bacterial Infection. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;15(3):374–381. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.02.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sonnenberg GF, Monticelli LA, Alenghat T, et al. Innate Lymphoid Cells Promote Anatomical Containment of Lymphoid-Resident Commensal Bacteria. Science. 2012;336(6086):1321–1325. doi: 10.1126/science.1222551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mayer EA. Gut feelings: the emerging biology of gut-brain communication. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2011;12(8):453–466. doi: 10.1038/nrn3071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hsiao EY, McBride SW, Hsien S, et al. Microbiota Modulate Behavioral and Physiological Abnormalities Associated with Neurodevelopmental Disorders. Cell. 2013;155(7):1451–1463. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.11.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yano JM, Yu K, Donaldson GP, et al. Indigenous Bacteria from the Gut Microbiota Regulate Host Serotonin Biosynthesis. Cell. 2015;161(2):264–276. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.02.047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sampson TR, Debelius JW, Thron T, et al. Gut Microbiota Regulate Motor Deficits and Neuroinflammation in a Model of Parkinson’s Disease. Cell. 2016;167(6):1469–1480.el2. doi: 10.1016/j.cel1.2016.11.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ren C, Yao R- Q, Zhang H, Feng Y- W, Yao Y- M. Sepsis-associated encephalopathy: a vicious cycle of immunosuppression. J Neuroinflammation. 2020;17(1):14. doi: 10.1186/sl2974-020-1701-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Alexander JJ, Jacob A, Cunningham P, Hensley L, Quigg RJ. TNF is a key mediator of septic encephalopathy acting through its receptor, TNF receptor-1. Neurochem Int. 2008;52(3):447–456.doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2007.08.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Annane D, Bellissant E, Bollaert PE, Briegel J, Keh D, Kupfer Y. Corticosteroids for treating sepsis. Cochrane Emergency and Critical Care Group, ed. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. Published online December 3, 2015. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002243.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Annane D, Maxime V, Ibrahim F, Alvarez JC, Abe E, Boudou P. Diagnosis of Adrenal Insufficiency in Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006; 174(12): 1319–1326. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200509-13690C [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Li S, Lv J, Li J, et al. Intestinal microbiota impact sepsis associated encephalopathy via the vagus nerve. Neurosci Lett. 2018;662:98–104. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2017.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tripathi A, Debelius J, Brenner DA, et al. The gut-liver axis and the intersection with the microbiome. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;15(7):397–411. doi: 10.1038/s41575-018-0011-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wahlström A, Sayin SI, Marschall H- U, Backhed F. Intestinal Crosstalk between Bile Acids and Microbiota and Its Impact on Host Metabolism. Cell Metab. 2016;24(l):41–50. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zarrinpar A, Loomba R. Review article: the emerging interplay among the gastrointestinal tract, bile acids and incretins in the pathogenesis of diabetes and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;36(10):909–921. doi: 10.1111/apt.12084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sinai CJ, Tohkin M, Miyata M, Ward JM, Lambert G, Gonzalez FJ. Targeted Disruption of the Nuclear Receptor FXR/BAR Impairs Bile Acid and Lipid Homeostasis. Cell. 2000;102(6):731–744. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)00062-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Copple BL, Li T. Pharmacology of bile acid receptors: Evolution of bile acids from simple detergents to complex signaling molecules. Pharmacol Res. 2016;104:9–21. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2015.12.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Inagaki T, Moschetta A, Lee Y- K, et al. Regulation of antibacterial defense in the small intestine by the nuclear bile acid receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2006;103(10):3920–3925. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509592103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Buffie CG, Bucci V, Stein RR, et al. Precision microbiome reconstitution restores bile acid mediated resistance to Clostridium difficile. Nature. 2015;517(7533):205–208. doi: 10.1038/naturel3828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Song X, Sun X, Oh SF, et al. Microbial bile acid metabolites modulate gut RORy+ regulatory T cell homeostasis. Nature. 2020;577(7790):410–415. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1865-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hang S, Paik D, Yao L, et al. Bile acid metabolites control TH17 and Treg cell differentiation. Nature. 2019;576(7785):143–148. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1785-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nesseler N, Launey Y, Aninat C, Morel F, Malledant Y, Seguin P. Clinical review: The liver in sepsis. Crit Care Lond Engl. 2012;16(5):235. doi: 10.1186/ccll381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gong S, Yan Z, Liu Z, et al. Intestinal Microbiota Mediates the Susceptibility to Polymicrobial Sepsis-Induced Liver Injury by Granisetron Generation in Mice. Hepatol Baltim Md. 2019;69(4): 1751–1767. doi: 10.1002/hep.30361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Dang AT, Marsland BJ. Microbes, metabolites, and the gut-lung axis. Mucosal Immunol. 2019;12(4):843–850. doi: 10.1038/s41385-019-0160-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Arrieta M- C, Stiemsma LT, Dimitriu PA, et al. Early infancy microbial and metabolic alterations affect risk of childhood asthma. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7(307):307ral52–307ral52. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aab2271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dickson RP, Erb-Downward JR, Huffnagle GB. The role of the bacterial microbiome in lung disease. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2013;7(3):245–257. doi: 10.1586/ers.13.24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Budden KF, Gellatly SL, Wood DLA, et al. Emerging pathogenic links between microbiota and the gut-lung axis. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2017;15(l):55–63. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Thorburn AN, Foster PS, Gibson PG, Hansbro PM. Components of Streptococcus pneumoniae Suppress Allergic Airways Disease and NKT Cells by Inducing Regulatory T Cells. J Immunol. 2012;188(9):4611–4620. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bernasconi E, Pattaroni C, Koutsokera A, et al. Airway Microbiota Determines Innate Cell Inflammatory or Tissue Remodeling Profiles in Lung Transplantation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016; 194(10): 1252–1263. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201512-2424OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Rutten EPA, Lenaerts K, Buurman WA, Wouters EFM. Disturbed intestinal integrity in patients with COPD: effects of activities of daily living. Chest. 2014;145(2):245–252. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-0584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Laheij RJF, Sturkenboom MCJM, Hassing R-J, Dieleman J, Strieker BHC, Jansen JBMJ. Risk of community-acquired pneumonia and use of gastric acid-suppressive drugs. JAMA. 2004;292(16):1955–1960.doi: 10.1001/jama.292.16.1955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Trompette A, Gollwitzer ES, Yadava K, et al. Gut microbiota metabolism of dietary fiber influences allergic airway disease and hematopoiesis. Nat Med. 2014;20(2):159–166. doi: 10.1038/nm.3444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gauguet S, D’Ortona S, Ahnger-Pier K, et al. Intestinal Microbiota of Mice Influences Resistance to Staphylococcus aureus Pneumonia. McCormick BA, ed. Infect Immun. 2015;83(10):4003–4014. doi: 10.1128/1Al.00037-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.van Ruissen MCE, Bos LD, Dickson RP, Dondorp AM, Schultsz C, Schultz MJ. Manipulation of the microbiome in critical illness—probiotics as a preventive measure against ventilator-associated pneumonia. Intensive Care Med Exp. 2019;7(S1):37. doi: 10.1186/s40635-019-0238-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bo L, Li J, Tao T, et al. Probiotics for preventing ventilator-associated pneumonia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(10):CD009066. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009066.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Dickson RP, Singer BH, Newstead MW, et al. Enrichment of the lung microbiome with gut bacteria in sepsis and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Nat Microbiol. 2016; 1(10): 16113. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Dickson RP, Schultz MJ, van der Poll T, et al. Lung Microbiota Predict Clinical Outcomes in Critically III Patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. Published online January 24, 2020:rccm.201907–14870C. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201907-14870C [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Schuijt TJ, Lankelma JM, Scicluna BP, et al. The gut microbiota plays a protective role in the host defence against pneumococcal pneumonia. Gut. 2016;65(4):575–583. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Gaines S, Alverdy JC. Fecal Micobiota Transplantation to Treat Sepsis of Unclear Etiology. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(6):1106–1107. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Zhang F, Luo W, Shi Y, Fan Z, Ji G. Should We Standardize the 1,700-Year-Old Fecal Microbiota Transplantation?: Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107(11):1755. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.de Groot PF, Frissen MN, de Clercq NC, Nieuwdorp M. Fecal microbiota transplantation in metabolic syndrome: History, present and future. Gut Microbes. 2017;8(3):253–267. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2017.1293224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Podolsky SH. Metchnikoff and the microbiome. The Lancet. 2012;380(9856):1810–1811. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62018-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Petrof EO, Khoruts A. From Stool Transplants to Next-Generation Microbiota Therapeutics. Gastroenterology. 2014;146(6):1573–1582. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.01.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Eiseman B, Silen W, Bascom GS, Kauvar AJ. Fecal enema as an adjunct in the treatment of pseudomembranous enterocolitis. Surgery. 1958;44(5):854–859. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Mullish BH, Quraishi MN, Segal JP, et al. The use of faecal microbiota transplant as treatment for recurrent or refractory Clostridium difficile infection and other potential indications: joint British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) and Healthcare Infection Society (HIS) guidelines. Gut. 2018;67(11):1920–1941. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2018-316818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Cammarota G, laniro G, Tilg H, et al. European consensus conference on faecal microbiota transplantation in clinical practice. Gut. 2017;66(4):569–580. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-313017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Drekonja D, Reich J, Gezahegn S, et al. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation for Clostridium difficile Infection: A Systematic Review. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(9):630–638. doi: 10.7326/M14-2693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.van Nood E, Vrieze A, Nieuwdorp M, et al. Duodenal infusion of donor feces for recurrent Clostridium difficile. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(5):407–415. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1205037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Wang Y, Wiesnoski DH, Helmink BA, et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation for refractory immune checkpoint inhibitor-associated colitis. Nat Med. 2018;24(12):1804–1808. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0238-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Bilinski J, Grzesiowski P, Sorensen N, et al. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation in Patients With Blood Disorders Inhibits Gut Colonization With Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria: Results of a Prospective, Single-Center Study. Clin Infect Dis Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am. 2017;65(3):364–370. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Woodhouse CA, Patel VC, Goldenberg S, et al. PROFIT, a PROspective, randomised placebo controlled feasibility trial of Faecal mIcrobiota Transplantation in cirrhosis: study protocol for a single-blinded trial. BMJ Open. 2019;9(2):e023518. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Giles EM, D’AdamoGL, Forster SC. The future of faecal transplants. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2019;17(12):719–719. doi: 10.1038/s41579-019-0271-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Moore T, Rodriguez A, Bakken JS. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation: A Practical Update for the Infectious Disease Specialist. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58(4):541–545. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Pamer EG. Fecal microbiota transplantation: effectiveness, complexities, and lingering concerns. Mucosal Immunol. 2014;7(2):210–214. doi: 10.1038/mi.2013.117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Smillie CS, Sauk J, Gevers D, et al. Strain Tracking Reveals the Determinants of Bacterial Engraftment in the Fluman Gut Following Fecal Microbiota Transplantation. Cell Host Microbe. 2018;23(2):229–240.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2018.01.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Taur Y, Coyte K, Schluter J, et al. Reconstitution of the gut microbiota of antibiotic-treated patients by autologous fecal microbiota transplant. Sci Transl Med. 2018; 10(460):eaap9489. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aap9489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Adhi FI, Littmann ER, Taur Y, et al. Pre-Transplant Fecal Microbial Diversity Independently Predicts Critical Illness after Flematopoietic Cell Transplantation. Blood. 2019;134(Supplement_l):3264–3264. doi: 10.1182/blood-2019-124902 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Stoma I, Littmann ER, Peled JU, et al. Compositional flux within the intestinal microbiota and risk for bloodstream infection with gram-negative bacteria. Clin Infect Dis. Published online January 24, 2020:ciaa068. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Peled JU, Gomes ALC, Devlin SM, et al. Microbiota as Predictor of Mortality in Allogeneic Hematopoietic-Cell Transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(9):822–834. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1900623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Suez J, Zmora N, Zilberman-Schapira G, et al. Post-Antibiotic Gut Mucosal Microbiome Reconstitution Is Impaired by Probiotics and Improved by Autologous FMT. Cell. 2018; 174(6): 1406–1423.el6. doi: 10.1016/j.cel1.2018.08.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Li Q, Wang C, Tang C, et al. Successful treatment of severe sepsis and diarrhea after vagotomy utilizing fecal microbiota transplantation: a case report. Crit Care. 2015;19(1):37. doi: 10.1186/sl3054-015-0738-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Wei Y, Yang J, Wang J, et al. Successful treatment with fecal microbiota transplantation in patients with multiple organ dysfunction syndrome and diarrhea following severe sepsis. Crit Care. 2016;20(1):332. doi: 10.1186/sl3054-016-1491-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Wurm P, Spindelboeck W, Krause R, et al. Antibiotic-Associated Apoptotic Enterocolitis in the Absence of a Defined Pathogen: The Role of Intestinal Microbiota Depletion. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(6):e600–e606. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Klingensmith NJ, Coopersmith CM. Fecal microbiota transplantation for multiple organ dysfunction syndrome. Crit Care. 2016;20(1):398, s13054–016-1567-z. doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1567-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Holscher HD. Dietary fiber and prebiotics and the gastrointestinal microbiota. Gut Microbes. 2017;8(2):172–184. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2017.1290756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.McClave SA, Taylor BE, Martindale RG, et al. Guidelines for the Provision and Assessment of Nutrition Support Therapy in the Adult Critically Ill Patient: Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) and American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (A.S.P.E.N.). J Parenter Enter Nutr. 2016;40(2):159–211. doi: 10.1177/0148607115621863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Lohner S, Küllenberg D, Antes G, Decsi T, Meerpohl JJ. Prebiotics in healthy infants and children for prevention of acute infectious diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr Rev. 2014;72(8):523–531. doi: 10.1111/nure.12117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Panigrahi P, Parida S, Nanda NC, et al. A randomized synbiotic trial to prevent sepsis among infants in rural India. Nature. 2017;548(7668):407–412. doi: 10.1038/nature23480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Shimizu K, Yamada T, Ogura H, et al. Synbiotics modulate gut microbiota and reduce enteritis and ventilator-associated pneumonia in patients with sepsis: a randomized controlled trial. Crit Care. 2018;22(1):239. doi: 10.1186/s13054-018-2167-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Kim SM, DeFazio JR, Hyoju SK, et al. Fecal microbiota transplant rescues mice from human pathogen mediated sepsis by restoring systemic immunity. Nat Commun. 2020;Accepted for publication, pre-print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.DeFilipp Z, Bloom PP, Torres Soto M, et al. Drug-Resistant E. coli Bacteremia Transmitted by Fecal Microbiota Transplant. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(21):2043–2050. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1910437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Yelin I, Flett KB, Merakou C, et al. Genomic and epidemiological evidence of bacterial transmission from probiotic capsule to blood in ICU patients. Nat Med. 2019;25(11):1728– 1732. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0626-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]