Abstract

Background:

Little is known about the longitudinal course of mood symptoms and functioning in youth who are at high risk for bipolar disorder (BD). Identifying distinct course trajectories and predictors of those trajectories may help refine treatment approaches.

Methods:

This study examined the longitudinal course of mood symptoms and functioning ratings in 126 youth at high risk for BD based on family history and early mood symptoms. Participants were enrolled in a randomized trial of family-focused therapy and followed longitudinally (mean 2.0 years, SD = 53.6 weeks).

Results:

Using latent class growth analyses (LCGA), we observed three mood trajectories. All youth started the study with current, active mood symptoms. Following the index mood episode, there was a “significantly improving course” (n=41, 32.5% of sample), a “moderately symptomatic course” (n=21, 16.7%), and a “predominantly symptomatic course” (n=64, 50.8%) at follow-up. More severe depression, anxiety, and suicidality at the study’s baseline were associated with a poorer course of illness. LCGA also revealed three trajectories of global functioning that closely corresponded to symptom trajectories; however, fewer youth exhibited functional recovery than exhibited symptomatic recovery.

Limitations:

Mood trajectories were assessed within the context of a treatment trial. Ratings of mood and functioning were based on retrospective recall.

Conclusions:

This study suggests considerable heterogeneity in the course trajectories of youth at high risk for BD, with a significant proportion showing long-term remission of symptoms. Treatments that enhance psychosocial functioning may be just as important as those that ameliorate symptoms in the early stages of BD.

Keywords: illness course, prognosis, pediatric, depression, mania, familial risk

1. Introduction

Between 50 – 66% of adults with bipolar disorder (BD) report illness onset prior to the age of 18, with prodromal symptoms emerging as early as 10 years before the full expression of the disorder (Perils et al., 2004). BD has a significant impact on psychosocial functioning and quality of life even when patients are in symptomatic remission (Gitlin and Miklowitz, 2017). Significant efforts have been undertaken to identify early clinical, biological, and genetic markers of risk for the illness (Birmaher et al., 2018; Hafeman et al., 2017; Luby and Navsaria, 2010; Post et al., 2010).

Youths at high risk (HR) for BD are commonly identified by (1) the presence of subsyndromal or syndromal hypomanic episodes that do not meet full DSM-5 duration criteria for bipolar I/II disorder (American Psychiatric Association, 2013); and/or (2) having at least one first or second-degree relative with a lifetime history of bipolar I or II disorder (Axelson et al., 2015). The combination of a family history and significant but subthreshold multi-symptom hypomanic intervals, commonly operationalized as other specified bipolar and related disorder (OSBRD) in DSM-5 (or in DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 2000), BD not otherwise specified [NOS]), is associated with a 46-59% rate of conversion to BD I or II over 1.5-5 years, compared to 2% in the general population (Axelson et al., 2011; Hafeman et al., 2017). Identifying populations of youth who are at high risk for BD is an important step toward developing early interventions to prevent or delay illness onset.

Few studies have examined the longitudinal trajectory of depressive or manic/ hypomanic symptoms in HR youth or predictors of these course trajectories. In two longitudinal studies of youth with bipolar I, II or NOS disorder, four distinct illness trajectories were identified over 2-4 years: predominantly euthymic (remitted) over time (24%-30% of youths), ill at baseline with a significantly improving symptom course (11-19% of youths), moderately symptomatic (i.e., euthymic between 45-50% of the time; 26-35% of BD youths), and predominantly ill over time (22-33% of youth) (Birmaher et al., 2014; Weintraub et al., 2020). In both studies, more severe baseline mood symptoms and suicidal ideation were associated with poorer courses of illness. Of note, a significant proportion of youth (i.e., the 41-43% who were either predominantly euthymic or were ill with a significantly improving course) in these studies had continuous remissions over 2-4 years. These studies suggest that there are distinct symptomatic courses of early-onset BD (Birmaher et al., 2014). The symptomatic courses of youth at high-risk for BD remains unclear, however. Identifying distinct course trajectories and predictors of those trajectories will help clarify long-term outcomes for these youth and may help refine treatment approaches.

The course of functional recovery following a mood episode in high risk youth is also unclear. Previous cross-sectional studies have also indicated that high risk youth have similar levels of psychosocial functioning (e.g., academic performance, social functioning) as youth with BD I and II and poorer functioning than youth without mood disturbances (Birmaher et al., 2014; Findling et al., 2010). Longitudinal studies in adult BD samples have found that full functional recovery is less frequent than symptomatic recovery in the year following a mood episode (Gitlin et al., 2011; Keck et al., 1998). Determining whether symptomatic course trajectories correspond to psychosocial functioning trajectories in HR youth can provide insights into the processes of mood episode recovery and help refine treatment approaches.

The present study examined whether there are distinguishable course patterns among youth at high risk for BD over a 3-year period. Participants were recruited to take part in a randomized trial of family-focused therapy for high-risk youth (FFT-HR) compared to standard psychoeducational care (Miklowitz et al., 2020). Using latent class growth modeling (LCGM), we identified longitudinal mood trajectory “classes” in HR youth based on up to 3 years of postrandomization follow-up. Next, we examined the association between baseline demographic, clinical, and family variables and course trajectory class membership. Finally, we used LCGM to identify trajectories of psychosocial functioning scores over the same time period, and examined whether youth with specific mood trajectories (e.g., a predominantly euthymic course) had corresponding patterns of global functioning (e.g., stably high levels of social and academic performance). Based on our previous work on the course patterns of adolescents with BD I or II, we expected four trajectories of mood symptoms (Weintraub et al., 2020). We hypothesized that more severe baseline mood symptoms, suicidal ideation, and anxiety would predict more continuously symptomatic courses of illness. Finally, we expected functional trajectories to correspond to symptom trajectories, although we predicted that full functional recovery would be less likely than full symptom recovery.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

The study enrolled youth between the ages of 9 and 17 years. Inclusion criteria included: (1) meeting for a lifetime DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 2000) and, later, DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) criteria for OSBRD (see below for operationalization), cyclothymia, or major depressive disorder (MDD); (2) having at least one first- or second-degree relative with a lifetime history of BD I or II by DSM-IV; (3) current affective symptoms, measured as either >11 on the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) over the past week or >29 on the Child Depression Rating Scale (CDRS) over the past two weeks (Poznanski and Mokros, 1996; Young et al., 1978); and (4) willingness for the youth and at least one caregiver to engage in family treatment. OSBRD was operationalized based on the criteria used in the Course and Outcome of Bipolar Youth (COBY) study (Birmaher et al., 2009): distinct 1-3 day periods of elevated, expansive or irritable mood plus two (three, if irritable only) DSM symptoms of mania that caused a change in functioning for a minimum of 10 days in the child’s lifetime. Exclusion criteria included a diagnosis of bipolar I/II disorder, autism spectrum disorder, or a current substance use disorder. Each participant received a full diagnostic evaluation from study psychologists and study psychiatrists; however, pharmacotherapy was not a requirement for participation. When participants opted for pharmacotherapy, study psychiatrists treating participants followed a pharmacotherapy algorithm designed for this population (Schneck et al., 2017).

2.2. Procedures

The study was conducted at three settings – University of California, Los Angeles, School of Medicine; University of Colorado, Boulder (Department of Psychology outpatient clinic); and Stanford University School of Medicine. After giving informed consent/assent to participate, youths were assessed for DSM-IV diagnoses using the semi-structured Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia, Present and Lifetime Version (KSADS-PL) (Chambers et al., 1985; Kaufman et al., 1997). At least one parent/caregiver was also interviewed using the K-SADS-PL, with final item ratings based on a consensus between the youth’s and the parent’s report. First- and second-degree relatives of the child were assessed through direct interview using the MINI-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (Sheehan et al., 1998) or, when the relative was not available, through secondary reports of available relatives using the Family History Screen Instrument (Weissman et al., 2000). All sites used MA/PhDlevel assessors who were trained and reliable in the assessment measures. Inter-rater reliability across sites for K-SADS mania and depression subscales were 0.84 and 0.74, respectively.

Following baseline assessments, participants were randomized, single blind, into either 12 sessions of family-focused therapy for high-risk youth (FFT-HR) over 4 months, consisting of psychoeducation, communication enhancement training, and problem-solving; or 6 sessions (3 family, 3 individual) of psychoeducation over 4 months (called enhanced care, or EC; Miklowitz et al., 2017). The first follow-up assessment occurred at post-treatment (4 months) and then at 8 and 12 months and every 6 months thereafter, up to 48 months following randomization. Study outcome assessments were conducted in-person by an independent evaluator who was unaware of the participants’ psychosocial treatment conditions.

2.3. Outcome Assessments

At baseline and each follow-up assessment, an independent evaluator administered the Adolescent Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation (A-LIFE) (Keller et al., 1987) to measure the severity of depression, mania, and hypomania symptoms for each interval. The A-LIFE’s Psychiatric Status Ratings (PSRs) are given weekly for each symptom cluster, and range from 1 (asymptomatic) to 6 (fully syndromal). The youth and at least one caregiver were assessed separately, with final ratings based on consensus between the two reports. To help youth and parents remember moods changes retrospectively, participants were provided with a calendar and asked to use “landmark events” (e.g., birthday, holidays, school breaks) to trace mood states over week-to-week intervals. Euthymic mood was defined as PSR depression, mania, and hypomania scale scores ≤ 2 (i.e., no more than 1 or 2 symptoms present in a mild degree). Subsyndromal symptoms were defined as PSR scores of 3 or 4, and syndromal symptoms as PSR scores ≥ 5 (i.e., patient would meet DSM criteria for a depressive or manic/hypomanic episode).

The Clinical Global Assessment Scale (CGAS) was used at the baseline and each follow-up assessment to rate youths’ overall functioning (Shaffer et al., 1983). At each assessment, independent evaluators rated the youths’ most severe past functioning (i.e., at baseline, the level of functioning during the most severe week of symptoms in the past 4 months or, at follow-up, since the previous assessment).

We measured socioeconomic status (SES) using the Hollingshead Scale (Hollingshead, 1975). At baseline, youth participants rated the Scale for Child Anxiety-Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED; Birmaher et al., 1997) and the Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire (Reynolds, 1987). The youth’s primary caregiver also rated their own mood symptom severity at baseline using the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS; Rush et al., 2003).

2.4. Statistical Analyses

We first conducted two separate analyses of latent class growth modeling (LCGM) in Mplus (Muthén and Muthén, 2005) to (1) identify separable trajectories of euthymic mood and, separately (2) identify separable trajectories of Children’s Global Functioning in the sample (Jung and Wickrama, 2008; Muthén and Muthén, 2005). For the LCGM of mood trajectories, we aggregated the week-by-week PSR mood scores collected at each study assessment – baseline, 4, 8, and 12 months (covering the prior 4 months) and 18, 24, 30, and 36 months (covering the prior 6 months). Following the methods of COBY and our previous study (Birmaher et al., 2014; Weintraub et al., 2020), we then calculated the percentage of weeks that participants were euthymic (PSR ≤ 2) for each of these assessment intervals. For the LCGM analysis of functional trajectories, we used the CGAS ratings of the most severe past episode gathered at baseline and each follow-up assessment over the 3 years. Of note, months 42-48 were excluded in this study because of significant attrition at these time points, which led to less than 10% covariance coverage between PSRs within participants across time points. The Mplus default requires at least 10% covariance coverage in order to use the missing data estimation algorithm.

To determine the final number of course trajectory classes for each LCGM, we started by examining the model fit of a one class model and sequentially added another class into the model, comparing the model fit to the model with one fewer class. The final number of classes for the LCGM was decided based on (1) successful convergence and replicability of the model when reexamined with a greater number of random starts (2) the model with the smallest Bayesian information criteria and a significant bootstrap likelihood ratio test (BLRT). The BLRT tests whether the model’s fit is significantly improved from the model with one fewer class, and performs as the best fit index for latent class growth models in Mplus (Nylund et al., 2007). Full information maximum likelihood (FIML; the default in Mplus) was used to handle missing data, which uses all available data to estimate parameters and assigns each participant with any available data to the class with the highest posterior probability of membership. Upon finding the best fitting model for the LCGMs, the latent class assignment for each participant was extracted.

Next, using univariate analyses of variance and chi-square tests, we compared the mood classes on baseline demographic variables (i.e., age, sex, race, ethnicity, SES) and longitudinal treatment and clinical variables (i.e., psychosocial treatment condition, weeks of follow-up, number of study visits, percentages of time with at least subthreshold PSR depression or mania/hypomania symptoms, and mean PSR mood symptom ratings). Second, we compared groups on baseline clinical variables (depression and mania severity, suicidal ideation, comorbid diagnoses, and medications at baseline and follow-up) and baseline parental depressive symptom severity. Finally, the correspondence of mood class membership to global functioning class membership was examined using a X2 test.

3. Results

Data were obtained from 127 participants who consented to the study, 75 of whom met lifetime criteria for MDD and 52 of whom met criteria for OSBRD. The mean age at study entry was 13.2 years (SD = 2.6); 64.6% were female, 18.1% were non-White, and 11.3% were Hispanic. The mean SES score was 46.0 (SD = 9.8), which corresponds to middle to uppermiddle class status. Baseline Psychiatric Status Ratings (PSRs) on the A-LIFE were available for 126 of 127 participants. Longitudinal PSR data were available for 112 participants at 4 months, 96 at 8 months, 87 at 12 months, 70 at 18 months, 60 at 24 months, 40 at 30 months, and 34 at 36 months (mean follow-up = 100 weeks, SD = 53.6). The latent classification analyses were constrained to the first 36 months of follow-up because of the small number of participants with 42-month (n = 24) or 48-month (n = 12) data. More information on the study design, sample, and treatment results are available in a previous publication (Miklowitz et al., 2020).

3.1. Latent Classification Analyses of Longitudinal Mood Scores

The aggregated PSR mood scores at each study assessment were examined over the first three years of the study. A three-class model best fit the data (see Figure 1 for mood trajectories). The BLRTs indicated a significant log-likelihood difference between the two-class and one-class model (log-likelihood = 69.28, p < 0.001) and between the 3-class and 2-class model (log-likelihood = 39.44, p < 0.001), indicating a significantly better fit for each successive model. The BLRT for the four-class model could not be calculated because the log-likelihood value for the 3-class model was larger than the value for the 4-class model. Compared to the other models, the 3-class model also had the lowest Bayesian information criteria value, which is also indicative of better model fit.

Figure 1.

Latent classes of euthymic mood over three years

Class 1 (“significantly improving course”; n = 41, 32.5% of the sample) describes participants who began the study with less than 10% of the previous four months in euthymic states and showed near-continuous improvement to ~70-80% euthymia by the end of the three years. Overall, participants in class 1 were euthymic for 52.4% (SD = 14.9) of the study weeks. Class 2 (“moderately symptomatic course”; n = 21, 16.7%) consisted of participants who maintained subsyndromal or syndromal mood symptoms during about 40% of the study period, and were euthymic about 59.5% (SD = 19.8) of that time. Class 3 (“predominantly symptomatic course”; n = 64, 50.8%) represented participants who, like class 1, were euthymic for less than 10% of the previous 4 months prior to study entry; these participants continued to exhibit subsyndromal or syndromal mood symptoms for the majority (M = 84.9%, SD = 15.1) of the weeks of follow-up.

Participants in classes 1 and 3 showed significantly improved euthymic mood by the end of the study compared to their baselines (ps < 0.01). Class 2 showed no significant change in mood over time. Youth in the predominantly symptomatic group (class 3) had the greatest percentage of time with sub-to-full threshold depressive or (hypo)manic symptoms (15.1% of weeks) compared to the other two classes (47.6% in class 1 and 40.5% in class 2). Within the overall sample, 18 (14.2%) youth converted to full threshold BD – four in class 1, three in class 2 and eleven in class 3. One additional youth in class 3 converted to schizoaffective disorder.

3.2. Demographic Correlates of Mood Class Membership

Demographic variables stratified by class membership are shown in Table 1. Participants’ ages, family SES, sex, and race were not associated with class membership. However, there was a greater proportion of Hispanic youths in the predominantly symptomatic group (n=18, 28.1%) compared to the group that had a significantly improving course (n=4, 9.8% in class 1) or the group with moderately symptomatic course (n=1, 4.8% in class 2).

Table 1.

Demographics and longitudinal clinical characteristics by class assignment

| Class 1: Significantly improving course (n = 41) |

Class 2: Moderately symptomatic course (n = 21) |

Class 3: Predominantly symptomatic course (n = 64) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | p | ES | |

| Age (years) | 13.5 | 2.7 | 12.7 | 2.1 | 13.2 | 2.6 | 0.55 | 0.01 |

| Hollingshead SES | 48.1 | 9.3 | 45.9 | 8.6 | 44.6 | 10.4 | 0.23 | 0.03 |

| N | % | N | % | N | % | p | ES | |

| Female | 24 | 58.5 | 12 | 57.1 | 46 | 71.9 | 0.27 | 0.15 |

| Non white | 9 | 22.0 | 2 | 9.5 | 12 | 18.8 | 0.68 | 0.17 |

| Hispanic | 4 | 9.8a | 1 | 4.8a | 18 | 28.1b | 0.01 | 0.26 |

| Longitudinal Clinical Characteristics | ||||||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | p | ES | |

| Weeks of follow-up | 106.8 | 45.8 | 118.4 | 52.5 | 95.9 | 53.9 | 0.19 | 0.03 |

| Psychotherapy visits | 9.0 | 3.6 | 8.2 | 3.6 | 7.6 | 4.2 | 0.22 | 0.03 |

| Medication visits | 5.5 | 5.3 | 6.0 | 5.6 | 6.0 | 6.0 | 0.88 | 0.00 |

| Percent of time: | ||||||||

| Euthymic | 52.4a | 14.9 | 59.5a | 19.8 | 15.1b | 15.2 | <0.001 | 0.62 |

| Sub- to full-threshold depressive sxs | 42.2a | 16.8 | 36.7a | 20.7 | 80.5b | 17.9 | <0.001 | 0.56 |

| Sub- to full-threshold manic sxs | 9.2a | 12.8 | 6.1a | 7.2 | 18.3b | 27.3 | 0.02 | 0.06 |

Note: Each superscript letter within a row denotes classes whose column proportions or means do not significantly differ from each other at the p<0.05 level.

PSR = Psychiatric Status Rating; SES = socioeconomic status; Sxs = Symptoms; ES = effect size (partial eta squared for ANOVA and Cramer’s V for chi-square)

3.3. Baseline Clinical Variables and Psychosocial Functioning

Baseline clinical and psychosocial functioning variables, stratified by mood symptom class membership, are presented in Table 2. Youths with a predominantly symptomatic course (class 3) had more severe baseline depressive symptoms compared to youths with a significantly improving course (class 1) and a moderately symptomatic course (class 2) (F(2,123) = 9.43, p < 0.001). Additionally, youths in class 3 had more severe suicidal ideation (F(2,111) = 6.92, p = 0.001) and greater anxiety severity on the SCARED at baseline (F(2,113) = 5.86, p = 0.004). Further, youths with comorbid anxiety disorders were more likely to have a predominantly symptomatic course than an improving or moderately symptomatic course (X2(2) = 8.48, p = 0.01). No other comorbid disorder distinguished among the trajectory classes.

Table 2.

Baseline clinical variables based on class assignment

| Class 1: Significantly improving course (n = 41) |

Class 2: Moderately symptomatic course (n = 21) |

Class 3: Predominantly symptomatic course (n = 64) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | p | ES | |

| Youth Symptom Severity | ||||||||

| Child Depression Rating Scale | 42.3a | 12.8 | 41.4a | 11.4 | 52.6b | 14.9 | <0.001 | 0.13 |

| Young Mania Rating Scale | 11.2 | 7.0 | 12.9 | 6.8 | 13.4 | 7.6 | 0.34 | 0.02 |

| Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire | 30.5a | 17.8 | 26.6a | 18.9 | 44.1b | 24.7 | 0.01 | 0.11 |

| Childhood Anxiety Related Disorders (SCARED) |

27.4a | 16.1 | 20.6a | 14.8 | 34.4b | 16.6 | 0.004 | 0.09 |

| Parent Symptom Severity | ||||||||

| Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS) | 25.3 | 6.1 | 24.5 | 7.7 | 26.9 | 6.3 | 0.28 | 0.02 |

| N | % | N | % | N | % | p | ES | |

| Mood Diagnosis | 0.31 | 0.14 | ||||||

| Major Depression | 28 | 68.3 | 11 | 52.4 | 35 | 54.7 | ||

| BD NOS | 13 | 31.7 | 10 | 57.6 | 29 | 45.3 | ||

| Comorbid Disorders | ||||||||

| Anxiety Disorder | 20 | 48.8a | 9 | 42.9a | 47 | 73.4b | 0.008 | 0.28 |

| ADHD | 15 | 36.6 | 8 | 38.1 | 25 | 39.1 | 0.97 | 0.02 |

| CD/ODD | 11 | 26.8 | 6 | 28.6 | 15 | 23.4 | 0.87 | 0.05 |

| Eating Disorder | 2 | 4.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 3.1 | 0.58 | 0.09 |

| OCD | 4 | 9.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 9 | 14.1 | 0.18 | 0.16 |

| PTSD | 2 | 4.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.6 | 0.41 | 0.12 |

| Medications | ||||||||

| Anticonvulsant | 4 | 9.8 | 3 | 14.3 | 10 | 15.6 | 0.69 | 0.08 |

| Antidepressant | 16 | 39.0 | 7 | 33.3 | 24 | 37.5 | 0.90 | 0.04 |

| Antipsychotic | 11 | 26.8 | 3 | 14.3 | 16 | 25.0 | 0.52 | 0.10 |

| Anxiolytic | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 4.8 | 3 | 4.7 | 0.37 | 0.13 |

| Lithium | 1 | 2.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.35 | 0.13 |

| Stimulant | 11 | 26.8 | 1 | 4.8 | 13 | 20.3 | 0.12 | 0.18 |

| No psychotropics | 17 | 41.5 | 12 | 57.1 | 27 | 42.2 | 0.43 | 0.11 |

| Global Assessment of Functioning | <0.001 | 0.33 | ||||||

| Class 1 – Significant functional improvement | 10 | 24.4a | 1 | 4.8b | 1 | 1.6b | ||

| Class 2 – Moderate functioning | 19 | 46.3a | 12 | 57.1a | 15 | 23.4b | ||

| Class 3 – Functionally impaired | 12 | 29.3a | 8 | 38.1a | 47 | 73.4b | ||

Note: Each superscript letter within a row denotes classes whose column proportions or means do not significantly differ from each other at the p<0.05 level.

ADHD = Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder; CD/ODD = Conduct Disorder/Oppositional Defiant Disorder; OCD = Obsessive Compulsive Disorder; PTSD = Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

There were no differences between classes on baseline (hypo)manic symptom severity (PSR ratings), age of onset of first mood symptoms, or high-risk diagnosis (OSBRD or MDD). Participants in the three classes did not differ in the likelihood of being assigned to FFT or enhanced care or in the number of protocol-based psychotherapy visits. They also did not differ in medication exposure across medication classes (i.e., anticonvulsant, antidepressants, antipsychotics, anxiolytics, lithium, and stimulants) at study entry. Finally, baseline parental depressive symptom severity (based on the QIDS) did not differ between classes.

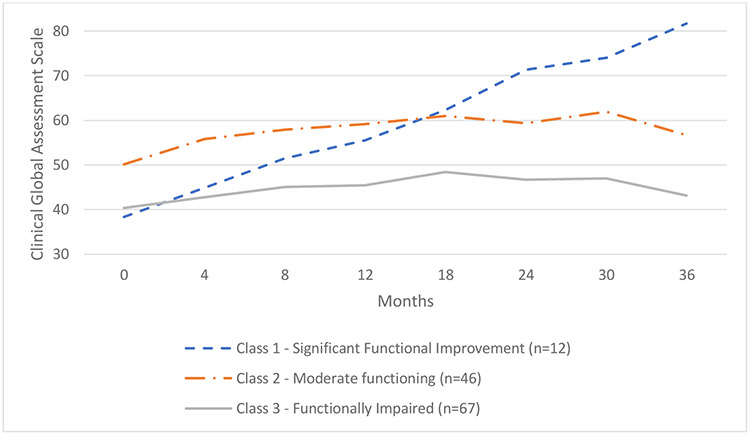

3.4. Latent Classes of Global Assessment of Functioning

The CGAS global functioning scores were examined at each study follow-up assessment. Baseline CGAS data were available on 125 of the 127 participants. Paralleling the symptom data, a three-class model best fit the CGAS trajectory data (Figure 2). The BLRTs indicated a significant log-likelihood difference between the two-class and one-class model (log-likelihood = 59.59, p < 0.001) and between the three-class and two-class model (log-likelihood = 17.47, p < 0.001), indicating a significantly better fit for each successive model. The BLRT for the four-class model did not have significantly better fit than the three-class model (log-likelihood = 8.96, p = 0.07). Compared to the other models, the 3-class model also had the lowest Bayesian information criterion value.

Figure 2.

Latent classes of global functioning over three years

Class 1 (“Significant functional improvement;” n = 12, 9.6% of the sample) contained participants who began the study with “major functional impairment in several areas” based on CGAS classifications (CGAS range of 31-40; M = 38.38, SD = 9.23) and showed substantial functional improvement, ending the study with “good functioning” (CGAS range of 81-90; M = 81.74, SD = 11.45). Class 2 (“Moderate functioning;” n = 46, 36.8%) consisted of participants who began the study with a “moderate degree of interference in functioning” (CGAS range of 41-50; M = 50.14, SD = 8.53) and ended the study with “variable functioning with sporadic difficulties” (CGAS score of 51-60; M = 56.64, SD = 10.83). Class 3 (“Significantly functionally impaired;” n = 67, 53.6%) represented participants who began the study with major functional impairment in several areas (M = 40.34, SD = 6.79) and ended the study with a moderate degree of interference in functioning (M = 43.16, SD = 8.87).

Mood class membership significantly corresponded to global functioning class membership (χ2 (4) = 30.99, p < 0.001; see Table 2). The significantly improving mood trajectory class had the highest proportion of youth who also had significant functional improvement. Of the 12 in the significant functional improvement class, 10 were classified in the significantly improving mood class (10 of 12; 83.3%). Conversely, the majority of youth in the predominantly symptomatic mood course had a functionally impaired course (47 of 64; 73.4%). The predominantly symptomatic mood course also had the lowest proportion of its youth who were classified as having moderate functioning (15 of 64; 23.4%).

4. Discussion

Using latent class growth analysis (LCGA), we examined whether distinct trajectories of mood symptoms and global functioning could be identified among youth at clinical and familial high risk for BD. We identified three mood trajectories based on the percentage of weeks that youth met criteria for euthymic mood on PSR ratings. Two of the groups started the study with less than 10% of the previous 4 months in euthymic states. The first group (class 1) represented 32.5% of the sample, and showed significant symptomatic improvement over the follow-up. A second group (class 3) consisted of 50.8% of the youth who were predominantly symptomatic throughout the study period. The final group (class 2; 16.7%) maintained moderate levels of mood symptoms (~40-60% euthymic) throughout the follow-up. More severe depressive symptoms, suicidal ideation, and comorbid anxiety disorders at baseline were the most closely associated with poorer courses of illness.

Contrary to our predictions, the fourth mood trajectory that was found in previous examinations of pediatric bipolar disorders (a predominantly euthymic group) did not emerge in this sample (Birmaher et al., 2014; Weintraub et al., 2020). It is unclear whether this fourth group does not exist in high-risk, mostly depressed youth or whether the eligibility criteria for the study (e.g., requirement of current active symptoms) ruled them out. However, 33% of the sample (Class 1) showed significant improvement within the first 8 months of follow-up and then maintained a primarily euthymic state throughout the study. The remaining two-thirds of the participants had significant mood symptoms for the majority of the follow-up period.

Functioning scores followed similar trajectories as mood symptoms, with youth following a significant functional improvement course (9.6%), a moderate functioning course (36.8%), and a functionally impaired course (53.6%). Interestingly, significant functional improvement was only achieved by about 10% of the sample, despite 33% of the overall sample showing significant symptomatic improvement. These findings suggest that many of the youth who recovery symptomatically may not achieve full functional recovery, or that functional recovery takes longer than symptomatic recovery, as has been observed in adults with BD (Keck et al., 1998). Some researchers have suggested that mood episodes create cognitive “scars” that delay recovery of functioning (Cullen et al., 2016; Just et al., 2001), a process that may begin in the early phases of illness. Treatments that enhance psychosocial functioning may be just as important as those that ameliorate symptoms in the early stages of BD.

The subgroup with a predominantly symptomatic course had more severe depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation at baseline. They also disproportionately had the poorest functional course over the study. Together, these findings suggest that greater depressive severity and suicidal ideation (as opposed to manic symptoms) have a larger impact on the course of illness, which is consistent with our previous study in adolescents with BD I and II (Weintraub et al., 2020). Depressive symptoms are consistently found to be one of the strongest predictors of a worse course of illness for individuals with mood difficulties (Birmaher et al., 2014; DelBello et al., 2007; Goldberg et al., 2009; Nolen et al., 2004). Failing to treat depression to remission is associated with poorer courses of illness and decreased response to treatment (Birmaher, 2014; Rush, 2007). These findings suggest the importance of developing more efficacious methods of fully stabilizing depressive symptoms in the early stages of mood disorder.

Diagnoses of anxiety disorder (based on the K-SADS-PL) and anxiety severity (based on self-report) were both linked to poorer symptomatic and functional course. Rates of comorbid anxiety were elevated compared to other samples of youth at high risk for BD (60% in this study vs. ~30-40% in the COBY and Pittsburgh Bipolar Studies; Axelson et al., 2011; Hafeman et al., 2013). Anxiety is a common phenotypic expression in individuals at familial risk for BD Duffy et al., 2018), and is associated with increased risk of conversion to full-threshold BD in adolescents (Nery et al., 2020). Together, anxiety appears to be an important intervention target for youth at risk for BD. Even in the context of family therapy, anxiety comorbid with pediatric BD is associated with more time with mood symptoms and greater family conflict over a twoyear period (Weintraub et al., 2019). It is possible that anxiety may interfere with the efficacy of family treatment due to avoidance of treatment skills (e.g., communication, problem-solving). Further research is needed to determine why anxiety is associated with poorer longitudinal course of illness and if more intensive pharmacotherapy (e.g., adjunctive SSRIs) or other skillsbased treatments (e.g., cognitive-behavioral therapy) can better manage comorbid anxiety in this population.

There were no differences between course trajectory classes in the proportion of youth treated with second generation antipsychotic agents, mood stabilizers, antidepressants or stimulants at study entry. Further, pharmacotherapy was not required for study participation. At baseline, a significant proportion of youth were not taking any psychotropic medications (44.1%). A little over one-third of the sample received antidepressant treatment (37.3%), and even fewer were prescribed mood stabilizers or antipsychotic medication (14.3% and 23.8%, respectively). It is encouraging that a large proportion of youth (~33%; class 1) showed significant mood and functional improvement. Youth with predominantly symptomatic courses (class 3), however, may benefit from more intensive pharmacotherapy than was provided in the study. The long-term efficacy of pharmacological treatments in stabilizing mood symptoms in youth at high risk for BD or for preventing illness onset should be investigated.

4.1. Limitations

The results of this study must be understood within the context of a treatment trial. It is difficult to determine the specific ways in which psychosocial and psychiatric treatments impacted the observed outcomes. Another limitation is that, by the end of the three-year study, data were available on about 27% of participants. While Mplus estimates parameters for missing data using FIML, it is unclear how the results may have been impacted by the missing data. It was also difficult to determine (possibly due to sample size limitations) what made the mood symptom classes 1 and 2 (significantly improving course and moderately symptomatic course), as these two groups did not show many differences on baseline psychiatric characteristics. Additionally, we were underpowered to compare classes on conversion to full threshold BD due to the low rate of conversion in the overall sample over the median of 2 years of follow-up (15%). Of note, youth with substance abuse and autism spectrum disorders were excluded, so these results do not generalize to these populations. Finally, recall and hindsight bias are a limitation of the study, particularly for measurement of mood and general functioning which assessing outcomes retrospectively over periods of up to 6 months.

5. Conclusion

This study found three distinct mood and functional trajectories over a three-year period in youth at high risk for BD. Greater depressive severity, suicidal ideation, and anxiety were predictive of poorer courses of illness. Characterizing the longitudinal mood trajectories for youth at familial and clinical high risk for BD can be clinically useful to patients and providers in developing personalized treatment approaches. Future treatment trials should select individuals based on predictor variables (e.g., baseline mood severity, suicidal ideation, comorbid anxiety) found to be associated with course patterns. These risk factors suggest the need for more intensive (or novel) pharmacotherapy and psychosocial treatment strategies. Additionally, developing treatments that improve psychosocial functioning, in addition to psychiatric symptoms, is necessary. Conversely, youth with milder mood symptoms and with minimal functional impairment may only require short courses of treatment with family psychoeducation. Tailoring treatment intensity to prognostic variables may prove to be a cost-effective approach to youth in the high-risk phases of BD.

Highlights.

Little is known about the longitudinal course of mood symptoms and functioning in youth who are at high risk for bipolar disorder (BD).

We analyzed mood and functional trajectories of youth at clinical and familial risk for BD over a three-year period.

Three longitudinal mood and functional trajectories were identified

More severe depressive, anxiety, and suicidality symptoms at the study’s baseline were associated with a more severe course of illness.

Fewer youth exhibited functional recovery than exhibited symptomatic recovery.

Acknowledgements:

The following individuals provided administrative support and study diagnostic or follow-up evaluations: Casey Armstrong, MA, Samantha Frey, BA, Brittany Matkevich, BA, and Natalie Witt, BA (UCLA School of Medicine); Tenah Acquaye, BA, Daniella DeGeorge, BA, Kathryn Goffin, BA, Jennifer Pearlstein, MA, and Aimee-Noelle Swanson, PhD (Stanford University); and Laura Anderson, MA, Addie Bortz, MA, Amethyst Brandin, BA, Anna Frye, BA, Luciana Massaro, MA BA, Zachary Millman, PhD, Izaskun Ripoll, MD, Rochelle Rofrano, BA, and Meagan Whitney, MA (University of Colorado, Boulder). The following clinicians provided study pharmacological or psychosocial treatments: Alissa Ellis PhD, Danielle Keenan-Miller, PhD, Eunice Kim, PhD, Sarah Marvin, PhD, and Jennifer Podell PhD (UCLA School of Medicine); Victoria Cosgrove, PhD, Priyanka Doshi, PsyD, Claire Dowdle, PsyD, Meghan Howe, LCSW MSW, Amy Friedman, LCSW, Jake Kelman, PsyD, Catherine Naclerio, PsyD, Casey O'Brien, PsyD, Donna Roybal, MD, Salena Schapp, PsyD, and Katherine Woicicki, PsyD (Stanford University); and Melissa Batt, MD, Emily Carol, PhD, Jasmine Fayeghi, PsyD, Elizabeth George, PhD, Christopher Hawkey, PhD, Daniel Johnson, PhD, Barbara Kessel, DO, Mikaela Kinnear, PhD, Daniel Leopold, MA, Jessica Lunsford-Avery, PhD, Susan Lurie, MD, Ryan Moroze, MD, MA, Dan Nguyen, MD, Andrea Pelletier-Baldelli, PhD, Christopher Rogers, MD, Lela Ross, MD and Dawn O. Taylor, PhD (University of Colorado, Boulder). Independent fidelity ratings of therapy sessions were provided by Eunice Y. Kim, PhD, UCLA School of Medicine. The following individuals provided consultation on study procedures, pharmacotherapy protocols: David Axelson, MD, Boris Birmaher, MD (University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, PA); Melissa DelBello, MD, MS (University of Cincinnati School of Medicine, Cincinnati, OH); Amy Garrett, PhD and Antonio Hardan, MD (Stanford University); Michael Gitlin, MD and Gerhard Helleman, PhD (UCLA School of Medicine); and Judy Garber, PhD (Vanderbilt University).

Role of Funding Sources:

Financial support for this study was provided by National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) grants R01MH093676, R01MH093666, R34MH077856, and R34MH117200. The sponsors named above did not have any role in the study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest:

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare. Dr. Weintraub receives research support from Aim for Mental Health and the Shear Family Foundation. Dr. Schneck receives research support from the NIMH and the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Treatment Extension Act. Dr. Walshaw has no disclosures. Dr. Chang is a consultant for Sunovion, Allergan, and Impel Neuropharma; he is also on the speakers’ bureau for Sunvion. Dr. Singh receives research support from Stanford’s Maternal Child Health Research Institute, National Institute of Mental Health, National Institute of Aging, Johnson and Johnson, Allergan, and the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation. She is on the advisory board for Sunovion, is a consultant for Google X and Limbix, and receives royalties from the American Psychiatric Association Publishing. Dr. Miklowitz has received research funding from the NIMH, Brain and Behavior Research Foundation, Attias Family Foundation, Danny Alberts Foundation, Carl and Roberta Deutsch Foundation, Kayne Family Foundation, Max Gray Foundation, American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, and AIM for Mental Health. He receives book royalties from Guilford Press and John Wiley & Sons.

References

- American Psychiatric Association, 2000. DSM-IV-TR: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, text revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association, 2013. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®). Am. Psychiatric Pub [Google Scholar]

- Axelson D, Birmaher B, Strober MA, Goldstein BI, Ha W, Gill MK, Goldstein TR, Yen S, Hower H, Hunt JI, 2011. Course of subthreshold bipolar disorder in youth: diagnostic progression from bipolar disorder not otherwise specified. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 50, 1001–1016. e1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axelson D, Goldstein B, Goldstein T, Monk K, Yu H, Hickey MB, Sakolsky D, Diler R, Hafeman D, Merranko J, 2015. Diagnostic precursors to bipolar disorder in offspring of parents with bipolar disorder: a longitudinal study. Am. J. Psychiatry 172, 638–646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmaher B, 2014. Improving remission and preventing relapse in youths with major depression. Am. Psychiatric Assoc [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmaher B, Axelson D, Goldstein B, Strober M, Gill MK, Hunt J, Houck P, Ha W, Iyengar S, Kim E, 2009. Four-year longitudinal course of children and adolescents with bipolar spectrum disorders: the Course and Outcome of Bipolar Youth (COBY) study. Am. J. Psychiatry 166, 795–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmaher B, Gill MK, Axelson DA, Goldstein BI, Goldstein TR, Yu H, Liao F, Iyengar S, Diler RS, Strober M, 2014. Longitudinal trajectories and associated baseline predictors in youths with bipolar spectrum disorders. Am. J. Psychiatry 171, 990–999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmaher B, Khetarpal S, Brent D, Cully M, Balach L, Kaufman J, Neer SM, 1997. The screen for child anxiety related emotional disorders (SCARED): Scale construction and psychometric characteristics. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 36, 545–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmaher B, Merranko JA, Goldstein TR, Gill MK, Goldstein BI, Hower H, Yen S, Hafeman D, Strober M, Diler RS, 2018. A risk calculator to predict the individual risk of conversion from subthreshold bipolar symptoms to bipolar disorder I or II in youth. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 57, 755–763. e754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers WJ, Puig-Antich J, Hirsch M, Paez P, Ambrosini PJ, Tabrizi MA, Davies M, 1985. The assessment of affective disorders in children and adolescents by semistructured interview: test-retest reliability of the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children, Present Episode Version. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 42, 696–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullen B, Ward J, Graham NA, Deary IJ, Pell JP, Smith DJ, Evans JJ, 2016. Prevalence and correlates of cognitive impairment in euthymic adults with bipolar disorder: a systematic review. J. Affect. Disorder 205, 165–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DelBello MP, Hanseman D, Adler CM, Fleck DE, Strakowski SM, 2007. Twelve-month outcome of adolescents with bipolar disorder following first hospitalization for a manic or mixed episode. Am. J. Psychiatry 164, 582–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy A, Goodday S, Keown-Stoneman C, Grof P, 2018. The emergent course of bipolar disorder: observations over two decades from the Canadian high-risk offspring cohort. Am. J. Psychiatry 176, 720–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Findling RL, Youngstrom EA, Fristad MA, Birmaher B, Kowatch RA, Arnold LE, Frazier TW, Axelson D, Ryan N, Demeter C, 2010. Characteristics of children with elevated symptoms of mania: the Longitudinal Assessment of Manic Symptoms (LAMS) study. J. Clin. Psychiatry 71, 1664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitlin MJ, Miklowitz DJ, 2017. The difficult lives of individuals with bipolar disorder: A review of functional outcomes and their implications for treatment. J. Affect. Disorder 209, 147–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitlin MJ, Mintz J, Sokolski K, Hammen C, Altshuler LL, 2011. Subsyndromal depressive symptoms after symptomatic recovery from mania are associated with delayed functional recovery. J. Clin. Psychiatry [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg JF, Perlis RH, Bowden CL, Thase ME, Miklowitz DJ, Marangell LB, Calabrese JR, Nierenberg AA, Sachs GS, 2009. Manic symptoms during depressive episodes in 1,380 patients with bipolar disorder: findings from the STEP-BD. Am. J. Psychiatry 166, 173–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafeman D, Axelson D, Demeter C, Findling RL, Fristad MA, Kowatch RA, Youngstrom EA, Horwitz SM, Arnold LE, Frazier TW, 2013. Phenomenology of bipolar disorder not otherwise specified in youth: a comparison of clinical characteristics across the spectrum of manic symptoms. Bipolar Disord. 15, 240–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafeman DM, Merranko J, Goldstein TR, Axelson D, Goldstein BI, Monk K, Hickey MB, Sakolsky D, Diler R, Iyengar S, 2017. Assessment of a person-level risk calculator to predict new-onset bipolar spectrum disorder in youth at familial risk. JAMA Psychiatry 74, 841–847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AB, 1975. Four factor index of social status. [Google Scholar]

- Jung T, Wickrama K, 2008. An introduction to latent class growth analysis and growth mixture modeling. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Comp 2, 302–317. [Google Scholar]

- Just N, Abramson LY, Alloy LB, 2001. Remitted depression studies as tests of the cognitive vulnerability hypotheses of depression onset: A critique and conceptual analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev 21, 63–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao U, Flynn C, Moreci P, Williamson D, Ryan N, 1997. Schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children-present and lifetime version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 36, 980–988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keck PE, McElroy SL, Strakowski SM, West SA, Sax KW, Hawkins JM, Bourne ML, Haggard P, 1998. 12-month outcome of patients with bipolar disorder following hospitalization for a manic or mixed episode. Am. J. Psychiatry 155, 646–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller MB, Lavori PW, Friedman B, Nielsen E, Endicott J, McDonald-Scott P, Andreasen NC, 1987. The Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Evaluation: a comprehensive method for assessing outcome in prospective longitudinal studies. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 44, 540–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luby JL, Navsaria N, 2010. Pediatric bipolar disorder: evidence for prodromal states and early markers. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 51, 459–471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miklowitz DJ, Schneck CD, Walshaw PD, Garrett AS, Singh MK, Sugar CA, Chang KD, 2017. Early intervention for youth at high risk for bipolar disorder: A multisite randomized trial of family-focused treatment. Early Interv. Psychiatry 13, 208–216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miklowitz DJ, Schneck CD, Walshaw PD, Singh MK, Sullivan AR, Suddath RL, Forgey-Borlik M, Sugar CA, Chang K, 2020. Family-focused Therapy for Symptomatic Youths at High Risk for Bipolar Disorder A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Psychiatry. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO, 2005. Mplus: Statistical analysis with latent variables: User's guide. Muthén & Muthén; Los Angeles. [Google Scholar]

- Nery FG, Wilson AR, Schneider MR, Strawn JR, Patino LR, McNamara RK, Adler CM, Strakowski SM, DelBello MP, 2020. Medication exposure and predictors of first mood episode in offspring of parents with bipolar disorder: a prospective study. Braz. J. Psychiatry [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen WA, Luckenbaugh DA, Altshuler LL, Suppes T, McElroy SL, Frye MA, Kupka RW, Keck PE Jr, Leverich GS, Post RM, 2004. Correlates of 1-year prospective outcome in bipolar disorder: results from the Stanley Foundation Bipolar Network. Am. J. Psychiatry 161, 1447–1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nylund KL, Asparouhov T, Muthén BO, 2007. Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A Monte Carlo simulation study. Struct. Equ. Modeling 14, 535–569. [Google Scholar]

- Perlis RH, Miyahara S, Marangell LB, Wisniewski SR, Ostacher M, DelBello MP, Bowden CL, Sachs GS, Nierenberg AA, Investigators, S.-B., 2004. Long-term implications of early onset in bipolar disorder: data from the first 1000 participants in the systematic treatment enhancement program for bipolar disorder (STEP-BD). Biol. Psychiatry 55, 875–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Post RM, Leverich GS, Kupka RW, Keck JP, McElroy SL, Altshuler LL, Frye MA, Luckenbaugh DA, Rowe M, Grunze H, 2010. Early-onset bipolar disorder and treatment delay are risk factors for poor outcome in adulthood. J. Clin. Psychiatry 71, 864–872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poznanski EO, Mokros HB, 1996. Children's depression rating scale, revised (CDRS-R). Western Psychological Services; Los Angeles. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds WM, 1987. Suicidal ideation questionnaire (SIQ). Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources. [Google Scholar]

- Rush AJ, 2007. STAR* D: what have we learned? Am. J. Psychiatry 164, 201–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Ibrahim HM, Carmody TJ, Arnow B, Klein DN, Markowitz JC, Ninan PT, Kornstein S, Manber R, 2003. The 16-item quick inventory of depressive symptomatology (QIDS), clinician rating (QIDS-C), and self-report (QIDS-SR): a psychometric evaluation in patients with chronic major depression. Biol. Psychiatry 54, 573–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneck CD, Chang KD, Singh MK, DelBello MP, Miklowitz DJ, 2017. A pharmacologic algorithm for youth who are at high risk for bipolar disorder. J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharm 27, 796–805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D, Gould MS, Brasic J, Ambrosini P, Fisher P, Bird H, Aluwahlia S, 1983. A children's global assessment scale (CGAS). Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 40, 1228–1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, Hergueta T, Baker R, Dunbar GC, 1998. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J. Clin. Psychiatry [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weintraub MJ, Axelson DA, Kowatch RA, Schneck CD, Miklowitz DJ, 2019. Comorbid disorders as moderators of response to family interventions among adolescents with bipolar disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 246, 754–762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weintraub MJ, Schneck CD, Axelson DA, Birmaher B, Kowatch RA, Miklowitz DJ, 2020. Classifying Mood Symptom Trajectories in Adolescents with Bipolar Disorder. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 53, 381–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman MM, Wickramaratne P, Adams P, Wolk S, Verdeli H, Olfson M, 2000. Brief screening for family psychiatric history: the family history screen. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 57, 675–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young R, Biggs J, Ziegler V, Meyer D, 1978. A rating scale for mania: reliability, validity and sensitivity. Brit. J. Psychiatry 133, 429–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]