Abstract

Background:

African Americans are significantly more likely than non-African Americans to have diabetes, chronic kidney disease, and uncontrolled hypertension, increasing their risk for kidney function decline.

Objective:

To compare how African Americans and non-African Americans with diabetes responded to a multifactorial telehealth intervention designed to slow kidney function decline.

Research Design:

Secondary analysis of a randomized trial. Primary care patients (N = 281, 56% African American) were allocated to either: 1) a multifactorial, pharmacist-delivered phone-based telehealth intervention focused on behavioral and medication management of DKD, or 2) an education control.

Measures:

Primary study outcome was change in estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR). Linear mixed models were used to explore the moderating effect of race on the relationship between study arm and eGFR decline over time; mean annual rate of eGFR decline was estimated by race and study arm.

Results:

Findings demonstrated a differential intervention effect on kidney function over time by race (pinteraction=0.005). Among African Americans, the intervention arm had significantly greater preservation of eGFR over time than the control arm (difference in annual rate of eGFR decline = 1.5 ml/min/1.73 m2, 95% CI [0.04, 3.02]). For non-African Americans, the intervention arm had a faster decline in eGFR over time than the control arm (difference in annual rate of eGFR decline = −1.7 ml/min/1.73 m2, 95% CI [−3.3, −0.02]).

Conclusions:

A multifactorial, pharmacist-delivered telehealth intervention for DKD may be more effective for slowing eGFR decline among African Americans than non-African Americans.

Keywords: diabetic kidney disease, racial disparities, telehealth intervention

INTRODUCTION

Type 2 diabetic kidney disease (DKD) is the leading cause of chronic kidney disease (CKD) worldwide (1). The prevalence of diabetes and advanced DKD is particularly high among racial minorities (1–3). Compared to non-African Americans, the high prevalence of DKD in African Americans is partially attributable to the increased prevalence of uncontrolled hypertension (41% vs. 28%), peripheral arterial disease (11.6% vs. 5.5%), and obesity (47% vs. 38%) (4–8). These disparities highlight the need for interventions focusing on modification of self-management behaviors important in DKD – such as medication adherence, diet, and exercise – among African Americans.

The Simultaneous Risk Factor Control Using Telehealth to slOw Progression of Diabetic Kidney Disease study (STOP-DKD, NCT01829256) examined the impact of a pharmacist-delivered medication management and behavioral telehealth intervention on kidney function decline over three years of follow-up in adults with evidence for DKD and poorly controlled hypertension (9). While the main results of this study showed no difference in attenuation of kidney function decline between intervention and control, this secondary analysis sought to determine whether there were differences in intervention response between African Americans and non-African Americans. The objective of this analysis was to understand how telehealth-based approaches might be employed to reduce racial disparities in DKD progression.

METHODS

STOP-DKD participants received usual care by their PCP and entered either: 1) a multifactorial, pharmacist-delivered phone-based telehealth intervention focused on behavioral and medication management, or 2) an education control, consisting of printed DKD management resources (10). All intervention treatment recommendations were protocol-based, and shared with the participant’s PCP via the electronic health record for implementation.

All study procedures and protocols were approved by the Duke University Institutional Review Board. All subjects provided written informed consent.

Participant Eligibility

STOP-DKD participants were recruited from Duke-affiliated primary care clinics. Inclusion criteria included: 1) adult (age ≥ 18 and ≤ 75 years); 2) regular use of the Duke University Health System (≥ 2 primary care visits in 3 prior years); 3) diagnosis of type 2 diabetes (ICD-9 codes 250.x0, 250.x2); 4) at least 2 serum creatinine values available in the 3 prior years, separated by at least 3 months; 5) preserved kidney function (eGFR ≥45 ml/min/1.73m2 on most recent creatinine estimated by calculating an eGFR using the 4-variable Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study [MDRD] equation); 6) evidence of diabetic nephropathy; 7) poorly controlled hypertension (two blood pressure values of SBP ≥ 140mmHg and/or DBP ≥ 90mmHg over 1 year); and 8) prescribed hypertension and diabetes medications.

Exclusion criteria included: lack of telephone access; lack of proficiency in English; residency in a nursing home/long-term care facility or receipt of home health care; impaired hearing/speech/vision; participation in another clinical trial (pharmaceutical or behavioral); plans to leave the area within 3 years; pancreatic insufficiency or diabetes secondary to pancreatitis; alcohol abuse (>14 alcoholic beverages per week); diagnosis of non-diabetic kidney disease; active malignancy; life-threatening illness and probable death within 4 years; secondary hypertension; pregnancy and/or breastfeeding; long-term or chronic dialysis; dementia; and receipt of renal transplant.

Randomization

Two-arm randomization was stratified by eGFR (eGFR 45–60 ml/min/1.73m2 vs. > 60 ml/min/1.73m2) and race (African American vs. non-African American).

Study Outcome

The primary outcome was estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) at 36 months, calculated using the CKD-EPI creatinine equation (11).

Additional Measures

Anthropometric measurements, biospecimen labs, self-reported demographics, and survey data were collected at baseline and yearly follow-up visits for three years.

For these analyses, race was dichotomized into African American and non-African American (White/Caucasian, Asian, American Indian/Alaska, Native, or Other) due to a majority of participants self-reporting African American or White/Caucasian race.

Analyses

Demographics and baseline characteristics were summarized using descriptive statistics. Differences were assessed using two-sample t-tests for continuous variables and chi-squared tests for categorical variables. All analyses were conducted on an intention-to-treat basis.

A multivariable linear mixed model with a random intercept for participant was used to examine the intervention’s differential effects on eGFR decline over time by race. Fixed effects included indicator variables for intervention and African American race, a continuous time variable, and all two- and three-way interaction terms between these variables. A common baseline across study arms within race was not assumed due to small differences in eGFR between arms at baseline. The three-way intervention by race by time interaction term was used to test the overall effect of race by arm over time. Appropriate contrasts of the estimated parameters were constructed and tested to estimate the annual rate of eGFR decline within each arm by race subgroups, and to compare the rates of decline between arms within race subgroups. We also adjusted the primary model by baseline eGFR to determine if results were sensitive to baseline differences in eGFR between the race groups. We also assessed missingness in exploratory analyses and performed multiple imputation to determine if our results were sensitive to missing outcome data.

In order to corroborate findings from the primary analysis, we also constructed a linear mixed effects model with a categorical time variable. With baseline visit as reference, the three indicator functions corresponded to follow-up at 12, 24, and 36 months. Fixed effects included all two- and three-way interaction terms between treatment arm, race, and visit indicator variables. Similarly, we estimated mean eGFR at each visit for each arm by race subgroups, and compared mean eGFR across arms within race subgroup over time.

Analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and R 3.4.4 (R core Team, Vienna, Austria). Hypothesis tests were two-sided. No adjustment for multiple testing was performed.

RESULTS

Participant population

Among the 281 individuals in this study, 52% were male and mean (SD) age was 62 (8.8) years; 55.5% (n=156) self-reported African American race, 41.3% (n=116) non-Hispanic white, and 3.2% (n=9) some other race (e.g., Asian, American Indian/Alaska, Native, or Other). At baseline, mean (SD) eGFR was 81 (21.7) ml/min/1.73 m2 overall, 85 (22.6) among African Americans and 75 (19.3) among non-African Americans.

Compared to non-African Americans, African Americans were younger (61 vs. 64 years), more likely to be female (54% vs. 42%), have an annual income <$60k (64% vs. 47%), less likely to be medication adherent (39% vs. 29%), and had slightly higher systolic (136 vs. 132 mmHg) and diastolic (80 vs. 72 mmHg) blood pressure at baseline. The racial subgroups were otherwise similar at baseline (Table 1).

Table 1.

STOP-DKD Baseline Sample Characteristics, Overall and Stratified by Race

| Baseline Characteristics* | Overall (n = 281) |

Non-AA (n = 125) |

AA (n = 156) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 62 (8.8) | 64 (8.1) | 61 (9.2) | <0.001 |

| Male, N (%) | 145 (51.6) | 73 (58.4) | 72 (46.2) | 0.05 |

| African American, N (%) | 156 (55.5) | 0 (0) | 156 (100) | |

| Education, N (%) | 0.69 | |||

| High School or less | 90 (32.0) | 37 (29.6) | 53 (34.0) | |

| Some college or technical school | 94 (33.5) | 44 (35.2) | 50 (32.1) | |

| College graduate or more | 95 (33.8) | 44 (35.2) | 51 (32.7) | |

| Retired or disabled, N (% yes) | 170 (60.5) | 79 (63.2) | 91 (58.3) | 0.56 |

| Household Income, N (%) | 0.01 | |||

| Less than $60,000 | 159 (56.6) | 59 (47.2) | 100 (64.1) | |

| Greater than $60,000 | 112 (39.9) | 63 (50.4) | 49 (31.4) | |

| Health Insurance, N (% yes) | 273 (97.2) | 123 (98.4) | 150 (96.2) | 0.88 |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 35.7 (7.9) | 35.3 (7.9) | 36.0 (7.9) | 0.47 |

| Medication Adherence Score†, mean (SD) | 1.7 (1.6) | 1.5 (1.6) | 1.9 (1.6) | 0.05 |

| Medication Non-adherent† (MM>2), N (% yes) | 97 (34.5) | 36 (28.8) | 61 (39.1) | 0.08 |

| Depressive Symptoms‡ (PHQ≥2), N (% yes) | 54 (19.2) | 27 (21.6) | 27 (17.3) | 0.48 |

| Cystatin C, mean (SD) | 1.1 (0.30) | 1.2 (0.34) | 1.0 (0.25) | <0.001 |

| Potassium, mean (SD) | 4.4 (0.47) | 4.5 (0.46) | 4.3 (0.44) | 0.01 |

| Systolic Blood Pressure, mean (SD) | 134 (19.5) | 132 (18.3) | 136 (20.2) | 0.04 |

| Diastolic Blood Pressure, mean (SD) | 76 (13.5) | 72 (12.1) | 80 (13.9) | <0.001 |

| Creatinine, mean (SD) | 1.0 (0.29) | 1.0 (0.31) | 1.0 (0.28) | 0.8 |

| ACR, mean (SD) | 186 (539.8) | 191 (668.8) | 182 (407.2) | 0.9 |

| Albuminuria (ACR≥30), N (%) | 135 (48.0) | 63 (50.4) | 72 (46.2) | 0.67 |

| eGFR by Creatinine, mean (SD) | 81 (21.7) | 75 (19.3) | 85 (22.6) | <0.001 |

| CKD Awareness§, N (% yes) | 19 (6.8) | 10 (8.0) | 9 (5.8) | 0.34 |

| A1c, mean (SD) | 8.0 (1.8) | 7.8 (1.6) | 8.1 (2.0) | 0.12 |

| A1c Categorized, N (%) | 0.06 | |||

| 5 ≤ A1c < 7 | 95 (33.8) | 41 (32.8) | 54 (34.6) | |

| 7 ≤ A1c < 8.5 | 97 (34.5) | 52 (41.6) | 45 (28.9) | |

| 8.5 ≤ A1c ≤ 15.1 | 88 (31.3) | 32 (25.6) | 56 (35.9) | |

| Out of control A1c||, N (% yes) | 126 (44.8) | 54 (43.2) | 72 (46.2) | 0.67 |

Abbreviations: BMI: Body Mass Index (kg/m2), MM: Morisky Medication Score, PHQ: Patient Health Questionnaire, ACR: Albumin Creatinine Ratio (mg/g), eGFR: Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate (ml/min/1.73m2), CKD: Chronic Kidney Disease

Two participants in the African American group were missing data for education level, employment status, health insurance status, medication adherence, depressive symptoms, and CKD awareness. For household income, seven participants in the African American group were either missing data, refused response, or did not know and three participants in the non-African American group did not know. Seven participants in the African American subgroup and three participants in the non-African American group were missing data for albuminuria. One participant in the African American group was missing data for A1c. Those with missing data were included in the percentage calculations.

Medication adhere was assessed using an 8-item measure of self-report adherence. Questions were reverse-scored such that higher scores indicated poorer medication adherence (40). Medication non-adherence was defined by a total score >2.

Depression was assessed using the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2), which evaluates the frequency of depressed mood and anhedonia over the previous two weeks (41). Scores ranged from 0 to 6, with a score of ≥2 indicating depressive symptoms.

CKD awareness was assessed by the question, “Have you ever been told by a doctor or other health professional that you had weak or failing kidneys? Do not include kidney stones, bladder infections, or incontinence.” Responses were dichotomized as yes (CKD aware) or no (CKD unaware) (42).

Out of control HbA1c defined as ≥8%

Differences in eGFR decline

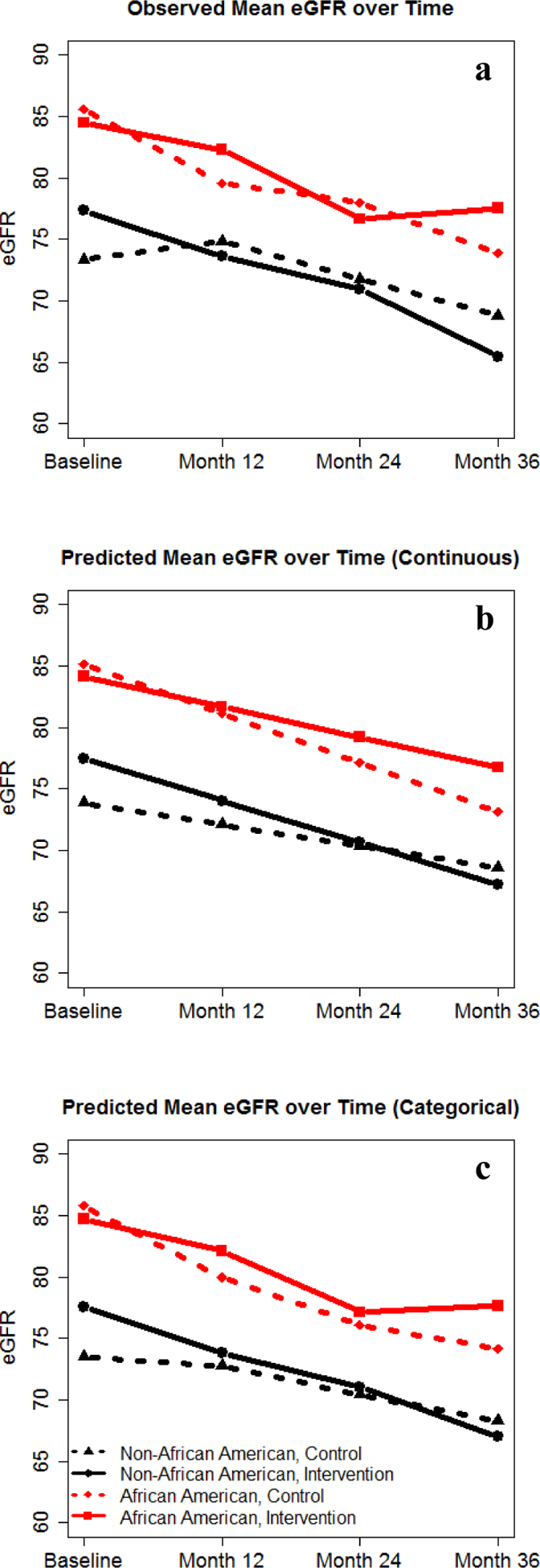

At each time point, African Americans had higher eGFR compared to non-African Americans (Figure 1a, 1b). In multivariable mixed models, African Americans receiving the intervention had slower mean rate of annual decline in eGFR than control (−2.5 mL/min/1.73m2, 95% CI [−3.5, −1.4] vs. −4.0, 95% CI [−5.1, −2.9]) while non-African Americans receiving the intervention had faster decline than control (−3.4, 95% CI [−4.6, −2.3] vs. −1.8, 95% CI [−2.9, −0.6]) (Table 2). There was evidence for a differential intervention effect over time between the racial subgroups (pinteraction=0.005). Results did not change substantively with baseline adjustment for eGFR or multiple imputation (results not shown).

Figure 1.

Observed and predicted mean eGFR over time. Abbreviation: eGFR: Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate (ml/min/1.73m2). a) Observed mean eGFR over time, b) Primary Analysis: Model Predicted eGFR over Time (Continuous), c) Secondary Analysis: Model Predicted eGFR over Time (Categorical).

Table 2.

Predicted annual rate of eGFR decline for each racial subgroup

| Intervention Predicted Rate [95% CI] | Control Predicted Rate [95% CI] | Difference in Annual Rate for Intervention vs. Control (95% CI); p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| African American | −2.5 [−3.5, −1.4] | −4.0 [−5.1, −2.9] | 1.5 [0.04, 3.02]; 0.044 |

| Non-African American | −3.4 [−4.6, −2.3] | −1.8 [−2.9, −0.6] | −1.7 [−3.3, −0.02]; 0.047 |

Similar results were seen with time modeled categorically (Figure 1c). The between-arm difference in eGFR decline from baseline between racial subgroups was significantly different at 36 months (p = 0.006), but not at 12 months (p = 0.059) or 24 months (p = 0.11) (Table 3, 4). African Americans in the intervention had the highest predicted mean eGFR at 36 months of all race by intervention arms.

Table 3.

Predicted mean eGFR and estimated differences in eGFR (95% CI) between study arms over time

| eGFR (ml/min/1.73 m2)/ Subgroup/Time Point | Intervention Predicted Mean [95% CI] | Control Predicted Mean [95% CI] | Difference in eGFR for Intervention vs. Control (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| African American | |||

| Baseline | 84.5 [79.1, 89.3] | 85.6 [80.9, 90.3] | −1.1 [−7.8, 5.6] |

| 12 months | 81.9 [77.1, 86.7] | 79.8 [74.9, 84.6] | 2.1 [−4.7, 9.0] |

| 24 months | 76.9 [72.0, 81.9] | 75.9 [70.9, 80.8] | 1.1 [−6.0, 8.1] |

| 36 months | 77.4 [72.4, 82.4] | 73.9 [68.9, 79.0] | 3.5 [−3.7, 10.6] |

| Non-African American | |||

| Baseline | 77.3 [72.0, 82.7] | 73.3 [68.1, 78.6] | 4.0 [−3.5, 11.5] |

| 12 months | 73.6 [68.1, 79.1] | 72.6 [67.2, 78.0] | 1.0 [−6.7, 8.7] |

| 24 months | 70.8 [65.2, 76.4] | 70.2 [64.7, 75.6] | 0.6 [−7.2, 8.5] |

| 36 months | 66.7 [61.1, 72.4] | 68.0 [62.5, 73.6] | −1.3 [−9.2, 6.6] |

Table 4.

Predicted differential effect of STOP-DKD compared to control over time among African Americans vs. Non-African Americans

| Change from Baseline (Difference in eGFR for Intervention vs. Control) [95% CI] | Difference in Change (AA – non-AA) [95% CI]; p-value | |

|---|---|---|

| 12 months | ||

| AA | 3.2 [−1.1, 7.5] | 6.2 [−0.2, 12.7]; 0.059 |

| Non-AA | −3.0 [−7.8, 1.8] | |

| 24 months | ||

| AA | 2.2 [−2.4, 6.7] | 5.5 [−1.3, 12.3]; 0.11 |

| Non-AA | −3.4 [−8.4, 1.7] | |

| 36 months | ||

| AA | 4.6 [−0.2, 9.3] | 9.9 [2.9, 16.9]; 0.006 |

| Non-AA | −5.3 [−10.5, −0.1] |

DISCUSSION

This secondary analysis examined racial differences in the effects of a multifactorial telehealth intervention focused on behavioral and medication management among adults with DKD and hypertension. Our analyses suggested the intervention was more effective among African Americans than non-African Americans. African Americans receiving the intervention experienced a lower rate of eGFR decline compared to control. The categorical time model showed this difference may take time to develop, suggesting that reductions in kidney function decline may accumulate over time. Even so, African Americans in the intervention experienced a clinically significant decline in eGFR of 2.5mL/min/1.73m2 per year, suggesting a more intensive approach may be needed for preservation of eGFR.

Our findings suggest that interventions targeting multiple modifiable behaviors, such as medication adherence, may attenuate some racial disparities in the burden of DKD. Despite similar prevalence of overall DKD across races in the United States, advanced DKD and contributing conditions such as hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and obesity, disproportionately affect racial minorities (4–8, 12–16). Interventions like STOP-DKD, while perhaps not designed specifically to address racial disparities, may help bridge these disparities by targeting key factors involved in DKD progression, including uncontrolled hypertension, diabetes self-management, health behaviors and knowledge, communication skills, medication use, and side effects.

These results are consistent with prior reports on differential racial responses in blood pressure reduction in response to hypertension self-management and dietary interventions (17–19). Our results, in conjunction with this body of literature, suggest lifestyle interventions are generally more efficacious among African Americans than non-African Americans (17, 20, 21). However, it is not entirely clear which factors mediate these differences.

One possible explanation for the differential racial responses to lifestyle interventions may stem from disparities in social determinants of health. Socioeconomic factors, such as limited education, lack of health care access, and low income, are strong predictors for ESRD development (22–26). Behavioral actions and cultural beliefs affect lifestyle factors such as diet, exercise, and medication adherence, as well as patient perception of disease and social support (27–31). Compared to non-African Americans, African Americans have less health insurance coverage and education, and are more likely to live in poverty, lack continuity in health care, and struggle with medication adherence (22, 32–34). These factors negatively impact access to health care, kidney transplants, and mortality in patients with ESRD (35–39).

In our study, African Americans had lower adherence to medication use and lower household income at baseline. African Americans also trended toward having less awareness of their CKD status at baseline. STOP-DKD and similar multifactorial interventions directly address these barriers by improving access to care, engagement with health behaviors, and knowledge, and by providing added medication management support for hypertension and comorbid conditions. Addressing these health disparities may help explain the racial differences observed in this study and others (17–19). Of note, there were no statistically significant differences in intervention adherence, as African Americans and non-African Americans completed a median of 32 and 33 (out of 36) encounters with the pharmacist, respectively. These results further suggest that similar levels of engagement with multifactorial interventions like STOP-DKD may disproportionately benefit African Americans.

Of note, this analysis suggested that non-Africans receiving the intervention paradoxically fared worse than those receiving the educational control. Given the borderline statistical significance of this finding, it is possible this within-subgroup difference may represent Type 1 error. Alternatively, there may be a threshold at which interventions like STOP-DKD become detrimental in populations with good access to care at baseline; it is possible that increased telehealth contact could potentially lead to fatigue, disengagement, and worse outcomes (26). Additional research will be needed to confirm this finding and to understand how telehealth interventions should be tailored for specific populations.

This study has several limitations. STOP-DKD was not designed to detect differential subgroup responses to the intervention, limiting our ability to definitively conclude a differential racial effect. The presence of missing data in our analyses could also influence conclusions regarding baseline differences, although our sensitivity analysis with multiple imputation provides some reassurance against this possibility. Additionally, it is unclear which multifactorial intervention components were most beneficial, and why these may have disproportionately affected African Americans compared to non-African Americans.

These analyses add to the growing literature suggesting differential racial responses to targeted interventions, and may extend this literature to eGFR decline in individuals with DKD, a highly consequential outcome. Our findings highlight the need for patient-centered, multifactorial interventions capable of adequately addressing the needs of high-risk populations for kidney failure.

Acknowledgements:

Sources of Funding: Research reported in this publication was supported by funding from the National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive, and Kidney Disease (NIDDK) (1R01DK93938 and P30DK096493). EAK is supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (TL1 TR002555). CJD is supported by a grant from NIDDK (K23-DK099385 and R01-DK09398). HBB is supported by a Senior Career Scientist Award VA HSR&D 08-027 and a grant from NIDDK (R34 DK102166). CAD is partially supported by UL1TR001117 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. ASA is supported by the National Institutes of Health (T32DK007012). UDP was supported by R01DK093938, R34DK102166, and P30DK096493 prior to joining Gilead Sciences in 2016. MJC is supported by a Career Development Award (CDA 13-261) from VA Health Services Research & Development.

Conflicts of Interest: Drs. Diamantidis, Bosworth, Davenport, Alexopoulos, Pendergast, Crowley, and Ms. Kobe and Oakes have no conflicts of interest to disclose. Dr. Patel is employed by Gilead Sciences.

Disclaimer: The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Duke University, the United States Department of Veteran Affairs, or the United States government.

Footnotes

NIH trial registry number: NCT01829256

REFERENCES

- 1.Saran R, Robinson B, Abbott KC, et al. US Renal Data System 2017 Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of Kidney Disease in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis 2018;71:A7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Golden SH, Brown A, Cauley JA, et al. Health disparities in endocrine disorders: biological, clinical, and nonclinical factors--an Endocrine Society scientific statement. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012;97:E1579–1639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Menke A, Casagrande S, Geiss L, et al. Prevalence of and Trends in Diabetes Among Adults in the United States, 1988–2012. JAMA 2015;314:1021–1029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tziomalos K, Athyros VG. Diabetic Nephropathy: New Risk Factors and Improvements in Diagnosis. Rev Diabet Stud 2015;12:110–118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. 2017. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/factsheets/factsheet_nhanes.pdf. Accessed April 26, 2019.,

- 6.Hertz RP, Unger AN, Cornell JA, et al. Racial disparities in hypertension prevalence, awareness, and management. Arch Intern Med 2005;165:2098–2104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Allison MA, Ho E, Denenberg JO, et al. Ethnic-specific prevalence of peripheral arterial disease in the United States. Am J Prev Med 2007;32:328–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevalence of coronary heart disease--United States, 2006–2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2011;60:1377–1381 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diamantidis CJ, Bosworth HB, Oakes MM, et al. Simultaneous Risk Factor Control Using Telehealth to slOw Progression of Diabetic Kidney Disease (STOP-DKD) study: Protocol and baseline characteristics of a randomized controlled trial. Contemp Clin Trials 2018;69:28–39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. National Kidney Disease Education Program.

- 11.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 2009;150:604–612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coresh J, Astor BC, Greene T, et al. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease and decreased kidney function in the adult US population: Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Am J Kidney Dis 2003;41:1–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duru OK, Li S, Jurkovitz C, et al. Race and sex differences in hypertension control in CKD: results from the Kidney Early Evaluation Program (KEEP). Am J Kidney Dis 2008;51:192–198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hsu CY, Lin F, Vittinghoff E, et al. Racial differences in the progression from chronic renal insufficiency to end-stage renal disease in the United States. J Am Soc Nephrol 2003;14:2902–2907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Muthuppalaniappan VM, Yaqoob MM. Ethnic/Race Diversity and Diabetic Kidney Disease. J Clin Med 2015;4:1561–1565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peralta CA, Katz R, DeBoer I, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in kidney function decline among persons without chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 2011;22:1327–1334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bosworth HB, Olsen MK, Grubber JM, et al. Racial differences in two self-management hypertension interventions. Am J Med 2011;124:468 e461–468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jackson GL, Oddone EZ, Olsen MK, et al. Racial differences in the effect of a telephone-delivered hypertension disease management program. J Gen Intern Med 2012;27:1682–1689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Svetkey LP, Simons-Morton D, Vollmer WM, et al. Effects of dietary patterns on blood pressure: subgroup analysis of the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) randomized clinical trial. Arch Intern Med 1999;159:285–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Appel LJ, Champagne CM, Harsha DW, et al. Effects of comprehensive lifestyle modification on blood pressure control: main results of the PREMIER clinical trial. JAMA 2003;289:2083–2093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Svetkey LP, Stevens VJ, Brantley PJ, et al. Comparison of strategies for sustaining weight loss: the weight loss maintenance randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2008;299:1139–1148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Norris KC, Agodoa LY. Unraveling the racial disparities associated with kidney disease. Kidney Int 2005;68:914–924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cunningham C, Stanley F. Indigenous by definition, experience, or world view. BMJ 2003;327:403–404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferguson R, Morrissey E. Risk factors for end-stage renal disease among minorities. Transplant Proc 1993;25:2415–2420 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krop JS, Coresh J, Chambless LE, et al. A community-based study of explanatory factors for the excess risk for early renal function decline in blacks vs whites with diabetes: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study. Arch Intern Med 1999;159:1777–1783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perneger TV, Whelton PK, Klag MJ. Race and end-stage renal disease. Socioeconomic status and access to health care as mediating factors. Arch Intern Med 1995;155:1201–1208 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Borzecki AM, Oliveria SA, Berlowitz DR. Barriers to hypertension control. Am Heart J 2005;149:785–794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chobanian AV. Shattuck Lecture. The hypertension paradox--more uncontrolled disease despite improved therapy. N Engl J Med 2009;361:878–887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Elmer PJ, Obarzanek E, Vollmer WM, et al. Effects of comprehensive lifestyle modification on diet, weight, physical fitness, and blood pressure control: 18-month results of a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2006;144:485–495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Forman JP, Stampfer MJ, Curhan GC. Diet and lifestyle risk factors associated with incident hypertension in women. JAMA 2009;302:401–411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Naik AD, Kallen MA, Walder A, et al. Improving hypertension control in diabetes mellitus: the effects of collaborative and proactive health communication. Circulation 2008;117:1361–1368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Williams DR, Mohammed SA, Leavell J, et al. Race, socioeconomic status, and health: complexities, ongoing challenges, and research opportunities. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2010;1186:69–101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bulatao RA, Anderson NB, National Research Council (U.S.). Panel on Race Ethnicity and Health in Later Life Understanding racial and ethnic differences in health in late life : a research agenda. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2004 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gerber BS, Cho YI, Arozullah AM, et al. Racial differences in medication adherence: A cross-sectional study of Medicare enrollees. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother 2010;8:136–145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alexander GC, Sehgal AR. Barriers to cadaveric renal transplantation among blacks, women, and the poor. JAMA 1998;280:1148–1152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kasiske BL, London W, Ellison MD. Race and socioeconomic factors influencing early placement on the kidney transplant waiting list. J Am Soc Nephrol 1998;9:2142–2147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Perneger TV, Klag MJ, Whelton PK. Race and socioeconomic status in hypertension and renal disease. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 1995;4:235–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Port FK, Wolfe RA, Levin NW, et al. Income and survival in chronic dialysis patients. ASAIO Trans 1990;36:M154–157 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wolfe RA, Ashby VB, Milford EL, et al. Differences in access to cadaveric renal transplantation in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis 2000;36:1025–1033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Morisky DE, Ang A, Krousel-Wood M, et al. Predictive validity of a medication adherence measure in an outpatient setting. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2008;10:348–354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 41.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care 2003;41:1284–1292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Chronic Kidney Disease Surveillance System - United States. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/kidneydisease/index.html