Abstract

Many cellular delivery reagents enter the cytosolic space of cells by escaping the lumen of endocytic organelles and, more specifically, late endosomes. The mechanisms involved in endosomal membrane permeation remain largely unresolved, which impedes the improvement of delivery agents. Herein, we investigate how 3TAT, a branched analog of the cell-penetrating peptide (CPP) TAT, achieves the permeabilization of bilayers containing bis(monoacylglycerol)phosphate (BMP), a lipid found in late endosomes. We establish that the peptide does not induce the leakage of individual lipid bilayers. Instead, leakage requires contact between membranes. Peptide-driven bilayer contacts lead to fusion, lipid mixing, and, critically, peptide encapsulation within proximal bilayers. Notably, this encapsulation is a distinctive property of BMP that explains the specificity of the CPP’s membrane leakage activity. These results therefore support a model of cell penetration that requires both BMP and the vicinity between bilayers, two features unique to BMP-rich and multivesicular late endosomes.

Keywords: cell-penetrating peptides, endosomal escape, cellular delivery, membrane leakage, bis(monoacylglycero)phosphate

eTOC blurb

Endosomal membrane translocation requires encapsulation of cationic CPPs between bilayers brought into close contact. The presence and abundance of the anionic lipid BMP are primary determinants of luminal leakage. Molecular dynamic simulations explain this mechanism through peptide-induced BMP spatial disarrangement and inverted micelle formation.

Introduction

Cellular delivery reagents such as cell penetrating peptides (CPPs) or cationic lipids often enter cells by first trafficking through the endocytic pathway.(Stewart et al., 2018; Stewart et al., 2016) These delivery agents then permeabilize the endosomal membrane to deliver their cargo, e.g., proteins or nucleic acids, into the cytosolic space of cells. The specifics of the endosomal escape process remain unresolved. Yet, this step is critical to the overall cell penetration process, as endocytic uptake alone only leads to entrapment of material in the lumen of endocytic compartments. In the absence of endosomal escape, biomolecules are directed to lysosomes and targeted for degradation. Conversely, cargo that escapes endosomes can enter the cytosol, reach cytoplasmic or nuclear targets, and display a variety of bioactivities. Achieving the endosomal escape of externally-administered biomolecules is therefore critical to the success of gene editing, cellular reprogramming, and cell biology assays, among others. In turn, understanding the endosomal escape process may permit the rational design of efficient cytosolic delivery reagents.

Several reports have indicated that late endosomes may serve as a site of endosomal escape. This is the case for the prototypical CPP TAT, arginine-rich miniature proteins, antisense oligonucleotides, and lipoplexes.(Appelbaum et al., 2012; Brock et al., 2018; Erazo-Oliveras et al., 2014; Steinauer et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2010) Notably, late endosomes are also a portal for the cell entry of toxins and viruses, indicating that cell delivery agents may mimic a mechanism of cell entry that biological species have evolved to exploit.(Gibert et al., 2000; Helenius, 2018; Patel et al., 2016; Zaitseva et al., 2010) Recently, we reported that constructs containing 2 or 3 TAT branches were significantly more prone to escaping late endosomes than constructs with a single TAT unit.(Brock et al., 2018; Erazo-Oliveras et al., 2014)F These constructs include dfTAT, a disulfide bonded dimer of TAT, or 3TAT (Figure S1), a species displaying three TAT sequences branching out from a peptidic scaffold. The high density of arginine residues is critical to these constructs’ ability to disrupt endosomal membranes and enter the cytosolic space of cells.(Najjar et al., 2017) While the majority of monomeric TAT molecules remain trapped inside endosomes after endocytic uptake by human cells, dfTAT and 3TAT are typically capable of escaping from endosomes efficiently. Indeed, the endosomal escape process occurs in nearly 100% of the cells in a culture, with the bulk of the peptide material escaping entrapment by translocating across endosomal membranes into the cytoplasm. Importantly, the endosomal leakage mediated by dfTAT or 3TAT can be used to deliver other molecules into cells. Small molecules, peptides, proteins, or nanoparticles endocytosed by cells while co-incubated with dfTAT or 3TAT accumulate inside endosomes along with the CPPs.(Brock et al., 2018; Erazo-Oliveras et al., 2014; Lian et al., 2017) The molecular cargos and the delivery peptides will then transit along the endocytic pathway and colocalize in the lumen of various endocytic organelles. Upon reaching late endosomes, dfTAT or 3TAT permeabilize these organelles and the cargos escape along with the delivery peptides.(Brock et al., 2018; Erazo-Oliveras et al., 2016) This process does not appear to require interactions between cargo and delivery peptide.(Erazo-Oliveras et al., 2014) Moreover, permeabilization allows the escape of particles with a diameter up to 100 nm, suggesting that large pores may be present during the peptide-mediated membrane leakage event.(Lian et al., 2017) Overall, this dfTAT- or 3TAT-facilitated endosomal escape allows for drastic enhancements in the amount of cargo that reaches the cytosolic space, in turn leading to robust intracellular activities. For example, without dfTAT, small organic molecule or tagged antibody probes distribute inside endosomes upon incubation with cells and show a punctate distribution. When dfTAT is present, these fluorescent molecules enter the cell and bind their intracellular targets, thereby allowing for fluorescence microscopy of subcellular components.(Erazo-Oliveras et al., 2014) Similarly, gene editing enzymes or transcription factors, either tagged with protein transduction domains or unmodified, show little intracellular activity after externally administration.(Erazo-Oliveras et al., 2014) In contrast, upon addition of dfTAT or 3TAT, these proteins reach the nucleus of cells and induce gene recombination or gene expression.(Allen et al., 2019; Brock et al., 2018; Erazo-Oliveras et al., 2014) Recently, dfTAT and 3TAT-like constructs have also been used to successfully deliver probes of the ubiquitination pathway, organelle-specific fluorophores for super resolution microscopy, and Cre recombinase for gene editing applications.(Blum et al., 2019; Hameed et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2019)

Previous results suggest that dfTAT and 3TAT escape from late endosomes, rather than other endocytic organelles.(Brock et al., 2018; Erazo-Oliveras et al., 2016) In one example, cell penetration is inhibited by blocking endocytic trafficking with dominant negative Rab7, which suggests that escape takes place in organelles downstream of early endosomes in the endocytic pathway. The CPPs also induce the cytosolic escape of cargos preloaded into endosomes, but not that of cargos that have accumulated into lysosomes. Additionally, dfTAT does not colocalize with recycling endosomes and does not penetrate cells by trafficking to the trans-Golgi network. Late endosomes differ from other endocytic organelles in that they are multivesicular and highly enriched in bis(monoacylglycerol)phosphate (BMP, also known as lysobisphosphatidic acid or LBPA). In particular, this anionic lipid accounts for up to 77% of total lipid content of intraluminal vesicles.(Chevallier et al., 2008; Hafez et al., 2001; Kobayashi et al., 2002; Kobayashi et al., 1998; Kobayashi et al., 2001) Consistent with the notion that dfTAT and 3TAT permeabilize late endosomes selectively, the CPPs can induce the leakage of bilayers containing BMP, but not of bilayers containing other lipids. Furthermore, an anti-BMP antibody blocks cell penetration in live cells when preincubated with cells.(Brock et al., 2018) Finally, the BMP-specific leakage-inducing activity of the reagents increases with the number of TAT repeats (3TAT>2TAT>>1TAT) and correlates with their cell penetration activity. These results suggest that the polycationic peptides interact with anionic BMP, thereby promoting the leakage of late endosomal membranes. Herein, we investigate the molecular features that make BMP-rich membranes prone to the permeabilization by CPPs. We identify features that are distinct to BMP and that suggest a unique mechanism of cell penetration accounts for the specific permeabilization of late endosomes.

Results

Contacts between BMP-rich bilayers are required for leakage

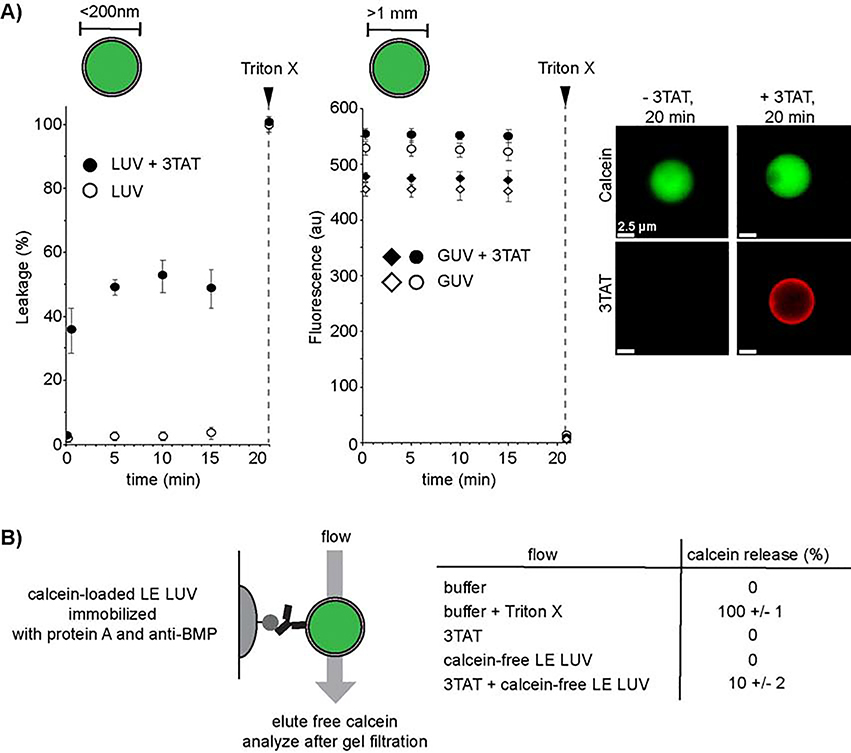

Prior experiments with BMP-containing liposomes (late endosome LUVs, LE LUV) and branched TAT analogs have shown concomitant liposomal fusion, flocculation, and leakage.(Brock et al., 2018) However, it was not clear whether lipid contact was necessary for leakage. To explore this idea, the activities of 3TAT towards LUVs (<200 nm in diameter) and GUVs (>1 μm in diameter) were compared (Figure 1). LUVs are free to contact one another when suspended in solution, while GUVs can settle at the bottom of a microscopy dish and avoid contact with other vesicles. Both LUVs and GUVs were loaded with calcein and the kinetics of leakage were recorded upon addition of 3TAT by measuring the release of calcein from the lumen of the vesicles. Fluorescence spectroscopy was used to measure the release of calcein from LUVs; fluorescence microscopy was used to monitor calcein leakage from individual GUVs. When added to BMP containing LUVs, 3TAT caused the rapid (<5min), albeit incomplete (<50%), release of calcein. In contrast, GUVs treated with 3TAT did not lose their calcein content, as shown by a constant fluorescence intensity over 15 min (Figure 1A). While this supports the notion that bilayer contact may be required for leakage, GUVs and LUVs differ in size and, accordingly, membrane curvature. To exclude size as a factor, we pursued a complementary approach to prevent contact between LUVs. Exploiting the availability of monoclonal anti-BMP antibodies, calcein-loaded LUVs were immobilized on protein A beads (iLUVs) (Figure 1B). A variety of buffers were flowed through the beads and calcein release was monitored. As with the GUVs, addition of 3TAT alone did not lead to leakage of iLUVs. Similar results were obtained with addition of calcein-free LE LUVs alone. However, addition of 3TAT immediately followed by calcein-free LE LUVs induced calcein leakage. These results suggest that contact between LUVs, as mediated by 3TAT, is necessary for leakage. The level of leakage was lower here than when LUVs were suspended in solution, indicating that bead immobilization reduces LUV–LUV contact and resulting leakage.

Figure 1.

Leakage requires liposome contact. A) Comparison of the kinetics of 3TAT-mediated leakage of Large Unilamellar Vesicles (LUVs) and Giant Unilamellar Vesicles (GUVs) encapsulating calcein in their lumen. The lipid composition of LUVs and GUVs was identical and consistent with that of late endosomal membranes (BMP:PC:PE 77:19:4). LUVs were suspended in solution while GUVs are allowed to settle on the surface of a microscopy dish. 3TAT was added at time t = 0 min to a final concentration of 5 μM, which yielded a peptide:lipid ratio of 1:50 in both samples. Leakage was measured at different time points by chromatographically determining the amount of free calcein released from LUV suspension or by monitoring the luminal calcein fluorescence intensity of GUVs by microscopy. Triton X-100 was used a control to determine the amount of maximum calcein release. The LUV data represent the average and corresponding standard deviations of triplicate experiments. The GUV data represent the average intensities of single GUVs over the area of the object. Representative data for 4 individual GUVs are shown and fluorescence microscopy images are provided for a GUV detected before and after 3TAT treatment. B) Leakage of LUVs immobilized to protein A beads. Protein A beads were packed into a column and LUVs encapsulating calcein were captured by the beads by addition of the anti-BMP monoclonal antibody. Solutions of various compositions were flowed through the column and free calcein released and eluted from the beads was quantified chromatographically. Addition of 3TAT (5 μM, peptide:lipid ratio of 1:50) alone, or addition of LUVs devoid of calcein, did not yield calcein leakage. In contrast, the combination of 3TAT followed by calcein-free LUVs caused calcein to leak out of immobilized LUVs.

Leakage is dependent on where fatty acids are conjugated to the bis glycerol phosphate backbone

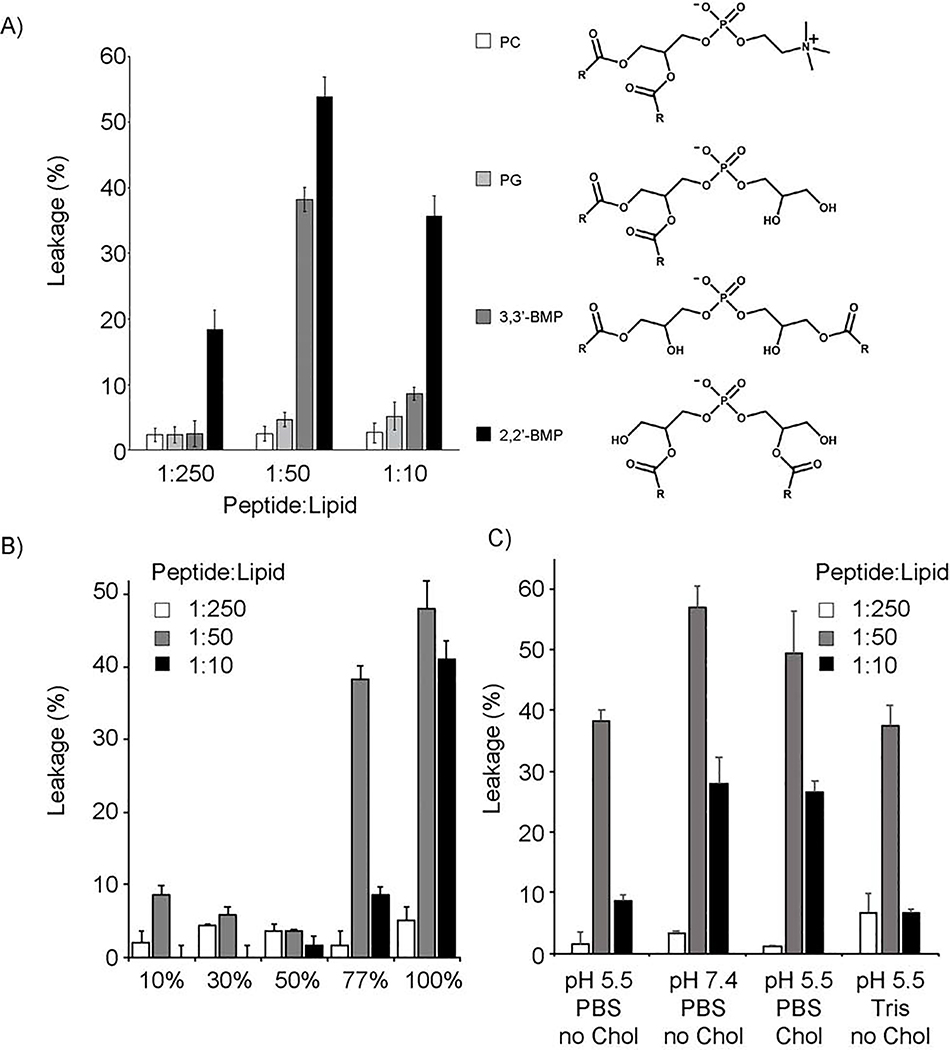

The BMP in late endosomes accounts for approximately 15–20 mol% of total phospholipid concentration.(Kobayashi et al., 1998) Within late endosomal membranes, BMP exists in two forms, 2,2’-BMP and 3,3’-BMP, with each lipid predominantly in dioleoyl conjugate form (18:1).(Gruenberg, 2020) The 2,2’-BMP isomer is thought to be the main form of BMP in the cell.(Gruenberg, 2020) However, 2,2’-BMP converts to 3,3’-BMP at acidic pH, rendering the cellular abundance of this lipid unclear. Moreover, the proportion of BMP present within the late endosomal membranes may vary locally. More specifically, intraluminal vesicles are enriched in this lipid in comparison to the limiting membrane (an abundance of up to 77% being present in some late endosome subfractions).(Kobayashi et al., 2002) Notably, BMP can spontaneously form multivesicular structures at pH 5.5, the approximate pH of late endosomes. This behavior is not observed at pH 7.0, indicating that BMP bilayers, and their ability to undergo fusion or fission, may be pH dependent.(Matsuo et al., 2004) Finally, while late endosomes play an important role in cholesterol homeostasis, the distribution of cholesterol among the various late endosome membranes is unclear.(Gruenberg, 2020) In principle, these parameters can modulate the biophysical properties of endosomal membranes and, hence, the escape of 3TAT. As such, we tested how membrane composition impacts 3TAT-mediated leakage in the LE LUV model system (Figure 2). First, 3TAT-mediated leakage was assessed with LUVs containing phosphatidylcholine (PC), phosphatidyl glycerol (PG), and 3,3’-BMP or 2,2’-BMP (77:19:4 X/PC/PE composition, where X is either PC, PG, 3,3’-BMP or 2,2’-BMP). PC is a zwitterionic lipid and PC LUVs were used as controls. PG and 3,3’-BMP/2,2’-BMP are anionic regioisomers that differ only in the connectivity of the fatty acid side chains (Figure 2A). 3TAT did not mediate the leakage of PC LUVs and displayed low activity against PG LUVs. In contrast, LUVs containing 3,3’-BMP/2,2’-BMP underwent partial leakage when exposed to 3TAT, with 2,2’-BMP LUVs being more susceptible to the peptide-mediated membrane disruption. Notably, the leakage of both types of LUVs diminishes at high peptide:lipid ratios, indicating that peptide-coated LUVs may repel each other as their surface becomes saturated with cationic charges (the zeta potential of the liposomes go from negative to neutral to positive as the peptide concentration is increased as previously reported).(Brock et al., 2018) Next, LUVs containing various percentages of 3,3’-BMP were treated with 3TAT. LUVs containing 50% BMP or less were relatively stable in the presence of 3TAT. In contrast, 77% and 100% BMP LUVs are leaky when exposed to 3TAT. Together, these data indicate that leakage and percentage of BMP are not linearly correlated. Instead, a threshold BMP content is required for leakage. In contrast, the pH of the leakage assay, the nature of the buffering agent (PBS versus Tris), and the presence of cholesterol (19 mol% vs 0 mol%) in the bilayer each had a moderate effect on 3TAT-mediated leakage. Of note, leakage achieved at pH 7.4 was higher than that obtained at pH 5.5, indicating that the acidic pH of late endosomes may inhibit leakage rather than stimulate it (the partial protonation of the BMP phosphate group and diminished electrostatic interactions with 3TAT may account for this effect).

Figure 2.

The presence of BMP and its abundance are primary determinants of leakage outcome. A) Effect of lipid composition on 3TAT-mediated leakage. LUVs were prepared with a lipid composition of X:PC:PE (77:19:4), X being either the zwitterionic lipid PC or the 3 anionic regioisomers PG, 3,3’-BMP and 2,2’-BMP. The fatty acid present in all lipids was oleic acid [18:1]. The release of free calcein upon treatment with 3TAT at the peptide:lipid ratios indicated was measured for each LUV suspensions. The fraction of LUV-bound peptide is 100% for all LUVs at 1:50 peptide:lipid ratios (as determined by sedimentation). B) Effect of the abundance of 3,3’-BMP in the bilayer on membrane leakage. LUVs were prepared with a lipid composition of BMP:PC:PE (X:96-X:4), with X being varied from 10% to 77%. LUVs exclusively containing 3,3’-BMP were also prepared. Free calcein leakage was quantified at the 3TAT:lipid ratios indicated. C) Effect of pH, cholesterol and buffer composition on leakage. The calcein leakage of 3,3’-BMP LUVs (BMP:PC:PE 77:19:4 or BMP:Chol:PE 77:19:4) treated with 3TAT was determined in PBS buffer at a pH of either 5.5 or 7.4, or in Tris buffer at pH 5.5.

The fluidity of BMP bilayers does not account for permeabilization propensity

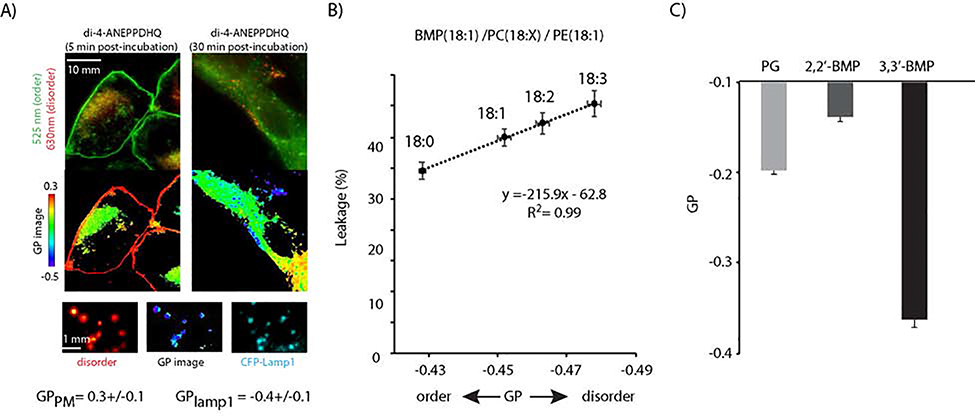

The clear differences observed between PG and 3,3’-BMP or 2,2’-BMP indicate that a major determinant of membrane leakage is the structure of BMP itself. We next tested the working hypothesis that BMP and PG generate bilayers with distinct biophysical properties. In particular, the unusual shape of BMP prompted us to investigate whether the lipid packing and fluidity of BMP bilayers are responsible for the leakage propensity of these membranes. This notion is partially supported by the fact that intracellular membranes are more fluid than the plasma membrane of cells.(Niko et al., 2016; Owen et al., 2011) Specifically, we confirmed that this increased fluidity extends to endocytic organelles, including late endosomes/lysosomes. This was demonstrated by labeling late endosomes and lysosomes with the markers Lamp1 or Lysotracker followed by measuring membrane fluidity using the lipid packing probe Di-4-ANEPPDHQ (Figure 3A).(Satpute-Krishnan et al., 2014) Accordingly, we next tested whether increasing the fluidity of BMP bilayers would correlate with an increase in leakage. For these experiments, 3,3’-BMP bilayers were doped with PC containing fatty acids with increased unsaturation – specifically, C18:0, C18:1, C18:2, and C18:3 (BMP variants with these fatty acids are not commercially available). As expected, the fluidity of the bilayer increased with unsaturated fatty acid content, as determined using Di-4-ANEPPDHQ and the derived generalized polarization (GP) values (Figure 3B). Notably, the leakage observed upon treatment with 3TAT correlated positively with increased fluidity. Next, the fluidity of PG, 3,3’-BMP or 2,2’-BMP bilayers were compared, using Di-4-ANEPPDHQ as a reporter. Surprisingly, while 3,3’-BMP LUVs were more disordered than PG LUVs, the 2’2-BMP bilayers were the most ordered based on this assay (Figure 3C). Given that 2’2-BMP and 3,3’-BMP bilayers are leaky when treated with 3TAT, while PG bilayers are not, these data suggest that membrane fluidity alone does not account for why BMP LUVs are leaky when PG LUVs are not.

Figure 3.

A) Assessment of the lipid order of endosomal membranes with the polarity sensitive probe di-4-ANEPPDHQ. Imaging was performed 5 min after incubation with the cells so as to observe the localization of di-4-ANEPPDHQ at the plasma membrane, and at 30 min after incubation to promote the endocytic internalization of the probe. Experiments were performed in cells transfected with CFP-Lamp1, a marker of late endosomes and lysosomes. Fluorescence images are pseudocolored green for emission of the probe at 525 nm, red for emission at 630 nm, and with a red to blue color palette for the calculated generalized polarization. The di-4-ANEPPDHQ 630 nm emission and high GP values are reflective of membrane order while 525 nm and low GP values are indicative of membrane disorder. CFP-Lamp1 is pseudocolored cyan in magnified images that highlight co-localization of organelles with low GP values and late-endosomes or lysosomes. B) Positive correlation between 3TAT-mediated LUV leakage and lipid bilayer disorder. LUVs composed of BMP/PC/PE (77:19:4) and encapsulating calcein were prepared. The fluidity of the bilayers was modulated by incorporating PC variants that contain the fatty acids with increasing unsaturation (18:0, 18:1, 18:2, and 18:3). The lipid order was measured with di-4-ANEPPDHQ and quantified with its corresponding GP value. Leakage was quantified by measuring the amount of free calcein released upon treatment with 3TAT (5 μM, peptide/lipid 1:50). The data represent the averages and corresponding standard deviations from triplicate experiments. C) Comparison of the lipid bilayer order of LUVs composed of X:PC:PE (77:19:4), X being the 3 anionic regioisomers PG, 3,3’-BMP and 2,2’-BMP. GP values were established spectroscopically with di-4-ANEPPDHQ. The data represent the averages and corresponding standard deviations from triplicate experiments

CPP-induced lipid bilayer fusion is similar between PG and BMP LUVs

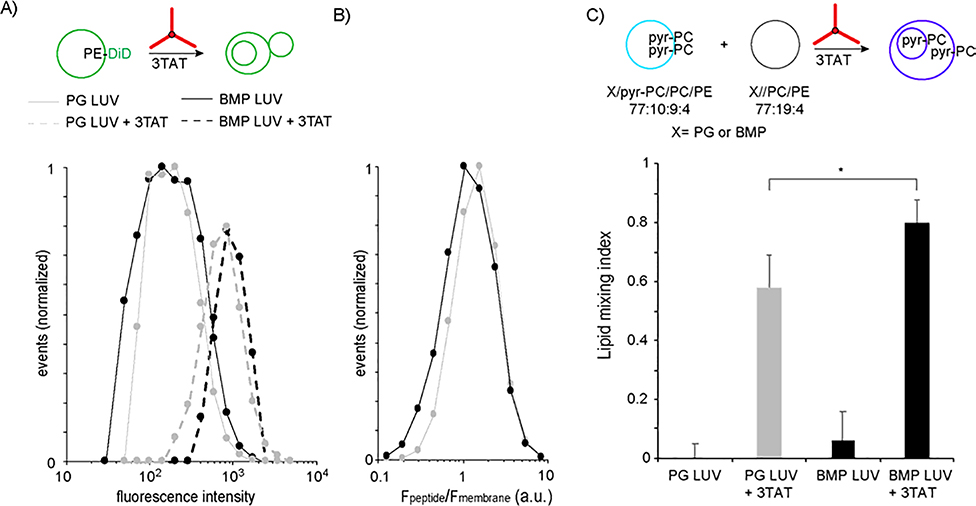

Because leakage requires bilayer contact, we sought to identify differences in 3TAT-induced membrane contact between PG and BMP LUVs. First, LUVs were analyzed by Burst Analysis Spectroscopy (BAS), a technique that detects fluorescent vesicles at a single particle level (Figure 4A).(Brock et al., 2018; Brooks et al., 2015; Puchalla et al., 2008b) PG and BMP LUVs were doped with 0.03% DiD-PE and detected by BAS using the green fluorescent DiD signal. The distribution of the DiD fluorescence signal, which is proportional to the amount of bilayer present in a particle, was then established for all events detected. Based on this analysis, the fluorescence signal of PG and BMP LUVs increases to a similar extent when exposed to 3TAT. This suggests that both types of vesicles are recruited by 3TAT to form structures with higher membrane content. To determine whether these structures involve lipid mixing between LUVs, we next used a pyrene excimer assay (Figure 4B).(Erazo-Oliveras et al., 2016) For this assay, LUVs doped with pyrene-PC were prepared and mixed with unlabeled LUVs at a 1:1 ratio. Fusion between the two types of LUVs results in the dilution of pyrene-PC in the bilayer and in the reduction of fluorescence emission originating from pyrene excimers. Based on this assay, lipid mixing and membrane fusion take place upon addition of 3TAT whether the CPP is added to PG or BMP LUVs. Moreover, the amount of lipid mixing detected is relatively comparable, BMP being only slightly more prone to fusion than PG. This suggests that 3TAT indiscriminately triggers the mixing and fusion of bilayers containing these lipids.

Figure 4.

3TAT causes the aggregation and fusion of PG and BMP LUVs to similar extents. A). LUVs doped with PE-DiD (0.03% total lipid) and treated with 3TAT (5 mM, peptide/lipid 1:50) were analyzed by Burst Analysis Spectroscopy. Fluorescence bursts from individual DiD-labeled liposomes in each sample were detected and quantified. Each fluorescent event is binned based on its fluorescence intensity and the overall population distribution is represented. The x-axis is a logarithmic scale of DiD fluorescence burst amplitude (which is directly proportional to membrane content and liposome size). The data represented are the compilation of triplicates. B) Quantification of 3TAT binding to LUVs by Burst Analysis Spectroscopy. Peptide binding to individual liposomes was assessed in 2 color BAS experiments by measuring the ratio of the fluorescence of the peptide (Fpeptide, TMR signal) to the fluorescence of the membrane (Fmembrane, DiD signal) obtained for each burst event detected during a BAS measurement. The data represented are the compilation of triplicates. C) Quantification of 3TAT-mediated lipid mixing using a pyrene excimer dilution assay. LUVs doped with 10% pyrene-PC were mixed with equivalent LUVs lacking pyrene-PC at a 1:1 ratio. Lipid mixing between LUVs leads to a dilution of pyrene excimers in the bilayer and to an increase in blue-shifted emission by monomeric pyrene. Lipid mixing was quantified by recording the fluorescence spectra of pyrene before and after addition of 3TAT. Membrane fusion is reported as a lipid mixing index, where 1 is the normalized monomer-to-excimer ratio obtained for LUVs prepared with 5% pyrene-PC. The data shown are the averages and corresponding standard deviations of triplicates.

3TAT-mediated lipid mixing of BMP bilayers leads to direct bilayer to bilayer contact

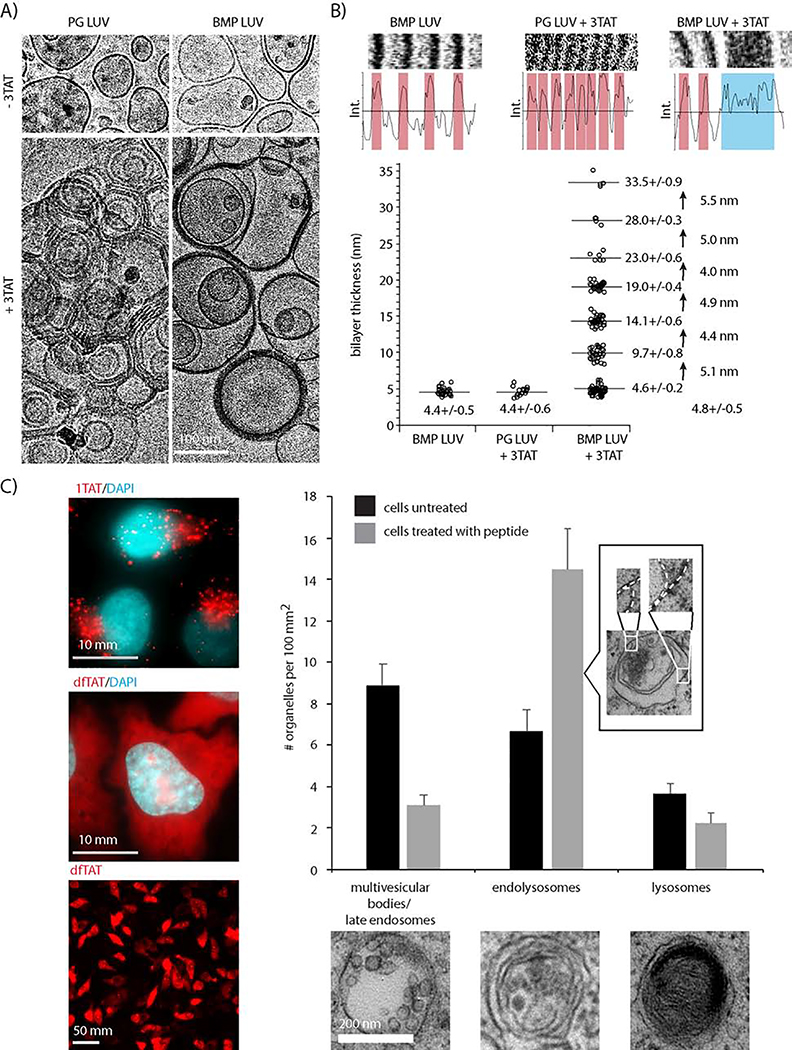

To assess 3TAT modification of BMP and PG bilayers, untreated and peptide-treated LUVs were imaged by cryogenic electron microscopy (Figure 5A). In the absence of peptide, LUVs are primarily unilamellar with a diameter ranging from 50–200 nm. Individual LUVs are also dispersed and interstitial space between LUVs is visible even when particles are imaged at high densities (see BMP LUV condition in Figure 5). In contrast, exposure of both BMP and PG LUVs to 3TAT leads to the formation of multilamellar structures which cluster. Consistent with the BAS data, these structures contain increased membrane content per particle. Clustered PG particles, despite their close proximity, display an interstitial gap between bilayers, indicating that lipid leaflets are not in direct contact. Notably, BMP bilayers that come in contact after 3TAT exposure often display an uninterrupted dark contrast that spans the thickness of several bilayers (Figure 5B). Thick BMP bilayers do not show any interstitial space and their thickness increases by increment of approximately 4.8 nm, the average thickness of individual bilayers being 4.6+/−0.4 nm (Figure 5B, Figure S2). Together, these data indicate no detectable separation of BMP bilayers following interacting with the CPP.

Figure 5.

A) 3TAT LUVs restructuring. PG or BMP LUVs were treated with 3TAT peptides (peptide/lipid 1:50), sedimented and imaged by cryo-electron microscopy. Untreated LUVs were imaged as a control. B) Quantification of the thickness of the bilayers present in cryo-EM images. Representative magnified images and accompanying intensity profiles are shown. Bilayers with discernable interstitial spaces are highlighted in pink while bilayers in contact and with no discernable interstitial spaces are highlighted in blue. Data points represent single bilayer thickness measurements performed over 5 images in duplicate experiments, the corresponding averages and standard deviations obtained from these measurements being provided. Membranes of BMP LUVs treated with 3TAT have a thickness that increases in increments corresponding to the addition of single bilayers. C) Examination of endocytic organelles by transmission electron microscopy in cells treated with dfTAT. Cells were treated with dfTAT (5 μM, 1hr) and cytosolic penetration was confirmed by fluorescence microscopy. Images shown are an overlay of dfTAT, pseudocolored red, and the nuclear stain Hoechst 33342, pseudocolored cyan. Cells incubated with the poorly endosomolytic peptide 1TAT are shown for comparison, endosomal entrapment of the peptide being indicated by its punctate distribution. Images obtained at 100X magnification show dfTAT distributes throughout the cell and stains nucleoli (highlighted with white arrows). Images obtained at 10X imaging show that nucleolar staining is observed in 90% of the cells in the population. Cells were then fixed, embedded in resin, and thin sections were imaged by TEM. The cross sections of ten cells were images for each condition and the number of organelles displaying the morphology of MVBs and late endosomes, endolysosomes, and lysosomes were counted. The data presented are the average and corresponding standard deviations of duplicate experiments.

We previously reported that the monoclonal anti-BMP antibody blocks cell penetration of dfTAT and its macromolecular cargo.(Erazo-Oliveras et al., 2014) Here, we found that anti-BMP mAb also inhibits 3TAT (Figure S3 and S4). It does so without reducing the amount of peptide endocytosed and without preventing the CPPs from reaching late endosomes. This suggests that the mAb blocks the peptides at the site of endosomal escape without reducing the accumulation of CPP in these organelles (Figure S3).Furthermore, anti-BMP mAb inhibits the leakage of LE LUVs (Figure S3). Specifically, the mAb does not block peptide–LUV binding (sub-stoichiometric mAb concentration; mAb:peptide:BMP ~1:5:250) but inhibits lipid mixing. Overall, these data establish that the results obtained with LE LUVs are consistent with the activities of the CPPs in live cells. To further assess the cellular relevance of the CPP-mediated membrane restructuring observed in vitro, we next compared the morphology of endocytic organelles upon peptide treatment. In this assay, we chose to use dfTAT as this CPP displays equivalent membrane permeabilization and endosomal escape activities as 3TAT, but with less cytotoxicity.(Brock et al., 2018; Erazo-Oliveras et al., 2016) HeLa cells were treated with dfTAT and successful cytosolic delivery was determined by fluorescence microscopy (Figure 5C, nucleolar accumulation of the peptide is used to validate intracellular localization). Cells were then fixed and imaged by transmission electron microscopy. Given that previous results indicated that endosomal escape takes place at late endosomes, organelles that display the morphology of these multivesicular vesicles were used for comparison (Figure 5C).(Brock et al., 2018; Erazo-Oliveras et al., 2016; Huotari and Helenius, 2011) In untreated cells, organelles containing intraluminal vesicles (ILVs) were identifiable at a density of 9/100 μm2. In contrast, these organelles were relatively absent in cells treated with peptide (3/100 μm2). Conversely, endolysosomes, the product of the fusion between late endosomes and lysosomes, were observed more frequently in peptide-treated cells than in their untreated counterparts (14 versus 7/100 μm2, respectively). Notably, these organelles contain multiple membranes in close proximity with one another, indicating that the bilayer contact observed in vitro is a plausible cellular phenomenon (Figure 5C). These observations support the notion that organelles containing ILVs are modified by peptide treatment and suggest that, upon peptide-mediated leakage, they undergo fusion with lysosomes to form endolysosomes.

BMP has a propensity to encapsulate a CPP that PG does not have

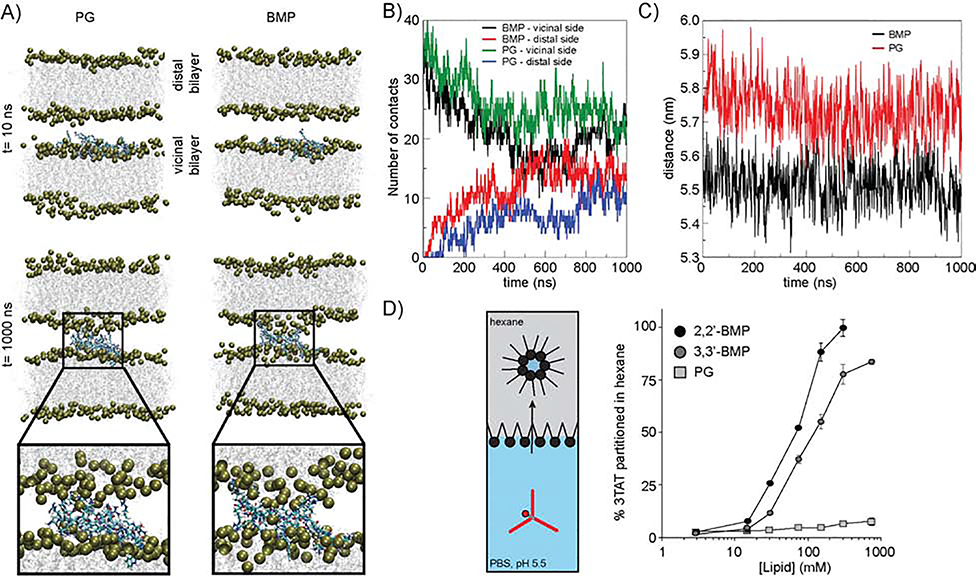

Extensive all-atom molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were used to obtain atomistic-level details on the distinct interactions of 3TAT with PG and BMP membranes. For these simulations, a double bilayer system was established wherein 3TAT is bound to a bilayer and placed in proximity to a second equilibrated bilayer (Figure 6A, Figure S5). The number of contacts between the arginine residues of 3TAT and the adjacent bilayers, as well as the distance between the bilayers, were then monitored over time (Figure 6B and 6C). Based on these analyses, 3TAT is capable of reaching a distal bilayer containing either PG or BMP. This results in an increase in contact points between peptide and distal lipid heads, as well as a reduction in the distance between the bilayer. Notably, these effects are more rapid and more pronounced for BMP than for PG within the timescale of MD simulations. Moreover, once 3TAT bridges two bilayers, BMP appears to more extensively surround the peptide than PG (magnified snapshot, Figure 6A). In particular, BMP shows a propensity for extending outside the bilayer, as if pulled out by the peptide, while PG remains anchored into the bilayer.

Figure 6.

A) Side view of BMP and PG double bilayers at the start and after 1000 ns of semi-isotropic NPT simulations. Water is omitted, while the lipids are shown in the ghost representation. Phosphorus atoms of the phosphate head groups are depicted as yellow spheres whereas 3TAT is shown in licorice. B) Time evolution of a number of contacts between the arginine residues of 3TAT (CZ atoms) and lipid head (P atoms) during 1000 ns. Contacts are calculated taking into account P atoms of lipids belonging to both the vicinal and distal side. Cutoff value used to calculate number of contacts was set to 0.6 nm. C) Evolution of the distance in z-direction between centers of mass of the two bilayers. D) Partitioning assay monitoring the transfer of 3TAT from PBS into hexane in the presence of either PG, 2,2’-BMP, or 3,3’-BMP.

To determine whether the BMP propensity for 3TAT encapsulation could be detected empirically, we tested 2,2’-BMP, 3,3’-BMP and PG in a partitioning assay. For this assay, 3TAT (3 μM) was added to PBS at pH 5.5. Increasing concentrations of BMP and PG lipids were added to hexane, a solvent used to mimic the inner hydrophobic region of a bilayer. Two equal volumes of the non-miscible solvents were then combined, mixed, and equilibrated. Aqueous and organic phases were then separated and the transfer of 3TAT into the hexane phase was monitored using the TMR fluorescence emission of the peptide (Figure 6D). When mixed in the presence of PG, 3TAT remained primarily in the aqueous phase. In contrast, both 2,2’-BMP and 3,3’-BMP were capable of transferring 3TAT into hexane. This process presumably requires the shielding of the cationic charges of the peptide by the anionic lipids and formation of inverted micelles or micelle-like structures. The onset of this phenomenon likely resembles the MD simulation snapshots of Figure 6A. Notably, the propensity of 2,2’-BMP to encapsulate 3TAT and transfer the peptide into hexane is higher than that of 3,3’-BMP. This, in turn, correlates positively with the leakage propensity observed in Figure 2A.

Discussion

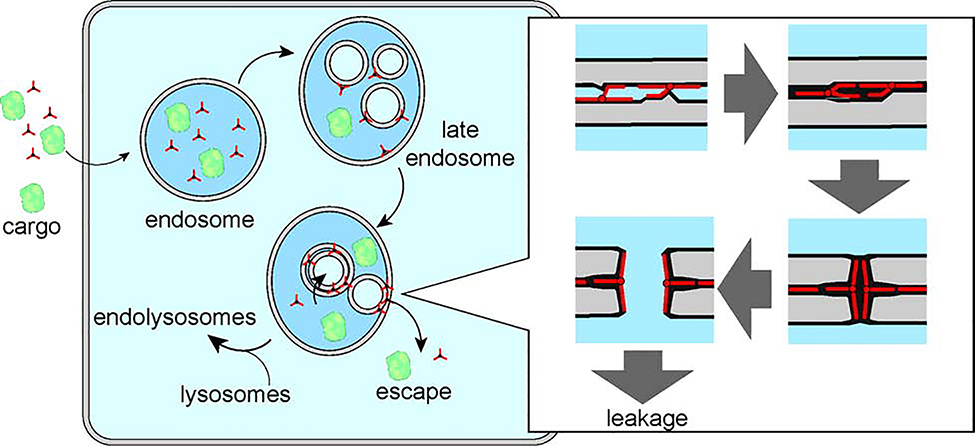

Based on the results presented herein, we propose a model for how dfTAT or 3TAT permeabilizes the membranes of late endosomes to enter the cytosol of live human cells (Figure 7). This model relies on three previously established factors: (1) late endosomes contain intraluminal vesicles (ILVs); (2) ILVs are rich in the lipid BMP; and (3) dfTAT and 3TAT mediate the transport of large cargos across the membranes of late endosomes.(Brock et al., 2018; Erazo-Oliveras et al., 2014; Erazo-Oliveras et al., 2016; Gruenberg, 2020) As the CPPs transit the endocytic pathway, the peptides reach late endosomes and bind to the luminal bilayer of ILVs, a process driven by the electrostatic interactions between the cationic peptide and anionic BMP.(Brock et al., 2018) The surface of the bilayer is then neutralized, and BMP-rich surfaces that would otherwise repulse each other can now come in closer contact. This phenomenon is also likely amplified by the fact that the peptide can distally reach from one surface to another, acting as a bridge between bilayers.

Figure 7.

Model of endosomal escape and cytosolic penetration of 3TAT in human cells. CPPs like 3TAT (three-pointed star) are endocytosed by cells, along with co-incubated cargos. Peptide and cargo traffic together along the endocytic pathway until reaching late endosomes. In these organelles, the CPP encounters intraluminal vesicles that are enriched in the lipid BMP. The peptide promotes the contact between these vesicles, along with fusion and lipid mixing. In turn, BMP encapsulates the CPP, thereby opening pores at membrane-contact sites. These pores are large enough to accommodate macromolecules, as previously reported.(Allen et al., 2019; Brock et al., 2018; Erazo-Oliveras et al., 2014) Membrane translocation is presumably driven by the concentration gradients of peptide and cargo. Translocation may take place at the limiting membrane (which would give direct access to the cytosol), or at intraluminal vesicles (which could be potentially followed by peptide-independent back fusion, an endogenous process). The illustration presented shows an example of how a cargo can translocate into the cytosol by crossing 3 bilayer contact sites.

While the liposomes used in our in vitro assays contain only lipids, ILVs comprise a variety of surface proteins that are likely to modulate contact between vesicles. For instance, the luminal domain of such proteins will create steric hindrance that may prevent direct contact between the lipid bilayers of ILVs. Given that proteins may diffuse laterally in the plane of the bilayer, we assume that patches of bilayers devoid of proteins may form locally. Such patches may in turn act as ILV–ILV contact sites. Lipid mixing and fusion of ILVs follows. However, as exemplified with PG liposomes, this alone is insufficient to induce leakage. Instead, once vesicles have fused, bilayer contacts persist. CPPs are interposed between two bilayers – as the number of peptide-lipid interactions increase, bulk water is excluded from the interstitial space. The contiguous bilayers form thick membrane systems, as seen by cryo-EM, thereby generating a hydrophobic environment in which the peptides are encapsulated by BMP. Here, the lipids at the contact sites shield the charges of the peptide by forming inverted micelle-like structures. These inverted micelles may diffuse within the adjoined bilayers and coalesce within one another.

We hypothesize that the leakage occurs at this stage of inverted micelle fusion back into the limiting endosomal membrane. Indeed, as BMP-peptide clusters increase in size within the bilayer, the peptides may now extend across the bilayers and reach the aqueous milieu. In turn, pores lined with peptide may open, thereby allowing the passage of macromolecules across the membrane of fused ILVs. In principle, CPP-permeabilized late endosomes may then mediate the cytosolic transfer of cargo in two different ways. In the first scenario, the limiting membrane of the organelle, fused to ILVs, is itself permeable, and cargo transfer occurs at this site directly. In the second scenario, cargos penetrate the lumen of ILVs; they are then delivered to the cytosol by back fusion of the ILVs to the limiting membrane. Based on our results, it appears that a high local density of BMP dictates the likely site of permeation. Cyro-EM examination of endosomal organelles post-delivery did not allow us to distinguish between the two, as we did not directly visualize late endosomes containing membranes with obvious signs of rupture. Instead, these experiments suggest that permeabilized late endosomes are converted to endolysosomes. It is likely that this conversion is initiated by membrane repair responses.(Andrews and Corrotte, 2018; Palm-Apergi et al., 2009; Scheffer et al., 2014; Skowyra et al., 2018)

A central aspect of the membrane permeabilization mechanism reported herein is the biophysical properties of BMP. Some of the unique characteristics of BMP have already been highlighted in the literature.(Gruenberg, 2020) Notably, BMP can promote the formation of multivesicular structures in liposomes, with this lipid possibly playing a role in the multivesicular organization of late endosomes.(Matsuo et al., 2004) BMP has also been reported to display a pH-dependent fusion activity, which has been suggested to participate in the back fusion of ILVs to the limiting membrane of late endosomes. These properties are attributed to the unusual fatty acid organization with respect to the glycerol moieties of the lipid, which presumably provides BMP with an inverted cone shape and flexibility that can assist membrane fusion. Taken together, the unique shape and flexibility of BMP can explain why BMP bilayers are leaky upon CPP treatment and why PG bilayers, which contain a lipid with an expected cylindrical shape, are not. Importantly, no significant differences are detected between BMP and PG in their fusogenicity in response to CPP binding.

Moreover, while increasing the fluidity of the bilayer increases its propensity for leakage, we do not detect a correlation between the fluidity of PG, 2,2’-BMP, and 3,3’-BMP, as measured with di-4-ANEPPDHQ, and the leakage of bilayers containing these lipids. Instead, a major difference between PG and BMP appears to relate to their respective ability to pull out of a bilayer and surround a CPP. This event was first observed by the formation of coalesced lipid bilayers (cryo-EM) and supported by MD simulations presented in this work. It was also measured experimentally in a partitioning assay that shows that 2,2’-BMP and 3,3’-BMP were able to carry the peptide into a hydrophobic environment. Notably, the propensity of the lipids to transport 3TAT into hexane positively correlated with their respective propensity for leakage.

Our previous studies indicated that the cell penetration activity of constructs like dfTAT and 3TAT is dramatically more pronounced than that of their monomeric counterpart, TAT.(Brock et al., 2018; Erazo-Oliveras et al., 2014; Erazo-Oliveras et al., 2016) dfTAT and 3TAT escape from late endosomes and, concomitantly, make BMP-containing membranes leaky. In contrast, TAT does not penetrate cells at levels detectable in our assays nor does it promote the leakage of BMP liposomes. However, Melikov and co-workers have reported that TAT could induce the leaky fusion of BMP/PC liposomes.(Yang et al., 2010) In addition, Shepartz and co-workers have also established that TAT can escape from late endosomes, albeit inefficiently.(Appelbaum et al., 2012) The same authors have also reported that other arginine-rich peptides escape these organelles.(Steinauer et al., 2019) Overall, our interpretation is that TAT, dfTAT, 3TAT, and potentially other arginine rich-species, follow similar mechanisms of cell entry and share similar biophysical activities. In particular, BMP is a likely interacting partner for all these cationic species once they traffic through the endocytic pathway and reach late endosomes. However, what presumably differs from one CPP to another is the efficiency with which they escape endosomes.

We propose that this activity depends on whether the peptide can bring the membranes of ILVs into contact and on whether it can form pores in adjacent bilayers. In principle, TAT is capable of achieving bilayer contact, even if only at relatively low levels. In contrast, dfTAT and 3TAT are efficient at these processes, though the molecular origin of this difference remains unknown. Note that dfTAT and 3TAT consist of several TAT peptides linked to one another – it is therefore possible that these constructs gain activity by simply increasing the local concentration of the otherwise weakly active TAT unit. However, in our assays, increasing the concentration of TAT, which may produce a high effective concentration, does not improve the membrane permeation of the peptide either in cell culture or in vitro.(Brock et al., 2018) Surprisingly, we have also observed that increasing the number of arginine residues in linear peptides (as opposed to branched constructs) favors direct plasma membrane translocation rather than cell entry via endocytosis.(Wang et al., 2016) In this regard, it should be noted that Jungwirth and co-coworkers have recently proposed that arginine-rich peptides translocate the plasma membrane of cells via membrane contacts and fusion pores. The authors attribute this activity to the CPP interacting with phosphatidyl serine; we have proposed that oxidized lipids may serve as additional interacting partners.(Allolio et al., 2018; Wang and Pellois, 2016; Wang et al., 2016) This, in turn, suggests that membrane fusion may confer permeability at various locations in cells. The topology and arginine distribution of the CPP, along with the distribution of encapsulation-prone lipids such as BMP, may then determine the location of these events. Furthermore, these factors may also contribute to the gain of activity observed for dfTAT and 3TAT.(Appelbaum et al., 2012; Vazdar et al., 2018) We expect that additional simulations of the peptides at membrane contact sites, along with structure-activity studies, may further reveal what makes these CPPs prone to endosomal escape. This, in turn, should aid the development of future generation of cell delivery agents.

STAR Methods

Resource Availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Dr. Jean-Philippe Pellois (pellois@tamu.edu).

Materials availability

No new reagents were generated for this study, however reagents generated by our lab are available upon request. All other reagents are available commercially as designated in the key resources table.

KEY RESOURCES TABLE.

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Anti-BMP | Echelon Biosciences | Cat: Z-PLBPA |

| Bacterial and Virus Strains | ||

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| 3TAT | This paper | N/A |

| 3,3’-DOBMP | Avanti Polar Lipids | Cat: 857135 |

| 2,2’-DOBMP | Echelon Biosciences | Cat: L-B181 |

| 18:1 (Δ9-Cis) PC (DOPC) | Avanti Polar Lipids | Cat: 850375 |

| DOPE | Avanti Polar Lipids | Cat: 850725 |

| Cholesterol | Avanti Polar Lipids | Cat: 700000 |

| 18:0 PC (DSPC) | Avanti Polar Lipids | Cat: 850365 |

| 18:2 (Cis) PC (DLPC) | Avanti Polar Lipids | Cat: 850385 |

| 18:3 (Cis) PCC | Avanti Polar Lipids | Cat: 850395 |

| 10-Pyrene-PC | Thermo Fisher | Cat: A32320 |

| Di-4-ANEPPDHQ | Thermo Fisher | Cat: D36802 |

| Experimental Models: Cell Lines | ||

| HeLa | ATCC | RRID: CVCL_0030 |

| CHO-k1 | ATCC | RRID: CVCL_0214 |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| CFP-Lamp1 | Satpute-Krishnan et al., 2014 | N/A |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| GROMACS 2018 | Hess et al., 2008 | http://www.gromacs.org/ |

| CHARMM-GUI | Jo et al., 2008 | http://www.charmm-gui.org/ |

| Packmol | Martínez et al., 2009 | http://m3g.iqm.unicamp.br/packmol/home.shtml |

| Slidebook 4.0 | 3i | https://www.intelligent-imaging.com/ |

| ImageJ GP calculation macro | Owen et al., 2011 | https://imagej.net/Fiji/Downloads#Source_code |

Data and code availability

All protocols and conditions regarding molecular simulations used in this article are detailed in this publication below.

Experimental Model and Subject Details

HeLa cells

Hela cells (female)(RRID: CVCL_0030) were maintained in 60mm plastic tissue culture treated dishes at 37°C and 5% CO2. Cells were grown in DMEM media supplemented with 10% FBS and penicillin/streptomycin and were split using 0.5% trypsin following two washes with PBS. Cells were purchased and authenticated directly from ATCC and were confirmed to be mycoplasma free using the MycoAlert kit (Lonza).

CHO-K1 cells

CHO-K1 cells (female)(RRID: CVCL_0214) were maintained in 60mm plastic tissue culture treated dishes at 37°C and 5% CO2. Cells were grown in FK12 media supplemented with 10% FBS and penicillin/streptomycin and were split using 0.5% trypsin following two washes with PBS. Cells were purchased and authenticated directly from ATCC and were confirmed to be mycoplasma free using the MycoAlert kit (Lonza).

Method Details

Peptide preparationPeptides were synthesized via SPPS on Rink amide MBHA resin (Novabiochem) using Fmoc chemistry. Fmoc was deprotected using two treatments with 20% piperidine in dimethylformamide (DMF) (Fisher Scientific) for 5 and 15 minutes, respectively. Couplings occurred for 4 hours using a mixture of the Fmoc-protected amino acid (4 mmol), HCTU (Novabiochem) (3.9 mmol) and diisopropylethylamine (DIEA) (Sigma-Aldrich) (10 mmol) dissolved in DMF. Once synthesis was completed, peptide scaffolds were labeled using a mixture of 5(6)-TAMRA (Sigma Aldrich), HCTU and DIEA (3, 2.9 and 7.5 eq., respectively) in DMF that was allowed to react overnight at room temperature under dry N2. For the non-fluorescent variant, nf3TAT, the scaffold’s N-terminus underwent anhydride-mediated acetylation. Once the N-termini of 3TAT and nf3TAT were labeled, Mtt was cleaved using 1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) (Fisher Scientific) and 2% tri-isopropylsilane (TIS) (Sigma-Aldrich) in dichloromethane (DCM). Following MTT deprotection, coupling of the TAT branches was conducted using solutions of Fmoc-amino acid (9 mmol), HCTU (8.7 mmol) and DIEA (22.5 mmol, respectively) in DMF and allowed to react for 16–24 hours. Upon completion, the N-terminal Fmoc of the peptides was removed as previously and the resin washed and dried in vacuo. Peptides were fully deprotected and liberated from the resin by treatment with 2.5% H2O, 2.5% TIS and 95% for 3 hours. Upon completion, crude peptide products were precipitated into cold, anhydrous diethyl ether (Fisher Scientific). Precipitates were lyophilized, resuspended in 0.1% TFA in H2O then analyzed and purified by reverse-phase HPLC. RP-HPLC analysis was performed using an Agilent 1200 series instrument equipped with a Biobasic-18 C18 column (Thermo Scientific) (5 μm particle size, 4.6 × 250 mm) and a diode array detector to read absorbance at λ = 214, 556 nm. Purification was performed on an Ultimate 3000 HPLC (Thermo Scientific) equipped with a Biobasic-18 C18 column (Thermo Scientific) (10 μm particle size, 21.2 × 250 mm) and a multiple wavelength detector set to 214 and 556 nm. These runs consisted of gradients using 0.1% aqueous TFA (solvent A) and 90% acetonitrile, 9.9% H2O and 0.1% TFA (solvent B). Correct peptide products were confirmed via MALDI-TOF using a Shimadzu/Kratos instrument (AXIMA-CFR). Unless otherwise stated, chemicals were purchased from ThermoFisher or Sigma. Lipids were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids. DiD-PE was obtained from Vybrant.

Vesicle preparation

Lipid mixtures dissolved in chloroform varied depending on each application. Compositions included LE (77:19:4 3,3’-DOBMP, DOPC, DOPE), substituting the 3,3’-DOBMP component of the LE mixture (77:19:4 DOX, DOPC, DOPE where X = DOPC, DOPG, 2,2’-DOBMP), varying BMP content while maintaining net charge (77-X:X:19:4 3,3’-BMP, DOPG, DOPC, DOPE where 10% = 10:67:19:4 3,3’-BMP, DOPG, DOPC, DOPE), substitution of DOPC with cholesterol (77:19:4 3,3’-DOBMP, Chol, DOPE), or varying in extent of fatty acid unsaturation (77:19:4 2,2’- or 3,3’-DOBMP, DXPC, DOPE where X = stearic acid [18:0], oleic acid [18:1], linoleic acid [18:2], or α-linoleic acid [18:3]). For lipid mixing assays, PG and BMP LUVs doped with 5% or 10% pyrene-PC were generated (10% py-PC LE LUVs = 77:10:9:4 2,2’-X, β-Py-C10-HPC, DOPE where X = 3,3’-DOBMP or DOPG). In each case, a lipid film was formed (250 nmol) by evaporation of chloroform in vacuo overnight. Lipid films were then allowed to swell in LUV buffer (10 mM sodium phosphate, 100 mM NaCl, pH = 7.4) for 15 min at 37°C with brief vortex agitation every 5 min. For leakage assays, swelling buffer contained 70 mM calcein. For lipid packing assays, swelling buffer contained 0.5 mol% Di-4-ANEPPDHQ (Thermo). Ten freeze/thaw cycles were then performed (thawing performed at temperatures 20°C above the highest Tc of lipids used) followed by extrusion through a 100 nm membrane (Whatman). Non-encapsulated calcein was separated from loaded liposomes through gel filtration.

GUVs were prepared via polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) gel-assisted formation. A 5% w/v PVA (40 kDa) solution was made by dissolving PVA into GUV buffer (10 mM sodium phosphate, 100 mM NaCL, 250 mM sucrose, pH 5.5 or 7.4) by stirring at 100°C for 30 min. The solution was aliquoted as a thin layer (500 μL) into the wells of a plastic 12-well plate and allowed to form a gel by incubation at 50°C for 1 hr. The lipids that compose LE GUVs (77:19:4 X/DOPC/DOPE where X = 2,2’-BMP or 3,3’-BMP) were dissolved in CHCl3 and 20 μL (62.5 nmol) lipid mixture was deposited in a thin layer on top of the PVA gel. Chloroform was then completely removed by evaporation in vacuo for 1 hr. GUVs were formed by addition of 0.5–1 mL of GUV buffer (pH 7.4) containing calcein (70 mM) to the dried lipid films for 2–5 min at room temperature. Upon completion, GUV formation and encapsulation of calcein was evaluated by fluorescence microscopy using an Olympus IX-81 inverted microscope. Fluorescence microscopy images were captured using a 100× objective and a Rolera-MGI Plus (Qimaging). Filters used in fluorescence imaging included a FITC (λex/em = 450–490, 500–550 nm) and RFP (λex/em = 535–580, 570–670 nm) filter cubes (Chroma Technology).

LUV leakage assays

Calcein-loaded LUVs ([Lipid] = 250 μM) composed of various lipid compositions were treated with 3TAT at 1:250, 1:50, or 1:10 peptide-to-lipid ratios of 3TAT (1, 5, or 25 μM, respectively) in PBS (10 mM sodium phosphate, 100 mM NaCl, pH = 5.5 or 7.4) or Tris (10 mM Tris-HCl, 100 mM NaCl, pH 5.5). Where peptide-to-lipid ratio is not indicated, LUVs were treated with 5 μM 3TAT. The LUVs and peptide were allowed to incubate for 1 hr at room temperature. For time-course leakage assays, the reaction was only allowed to occur for each indicated time point. Following incubation, liberated calcein was separated from LUVs and lipid debris by gel filtration and the absorbance was measured via an UltiMate MWD-3000 (Thermo). Normalization of leakage was performed by comparison to leakage recorded by liposomes treated with 1% Triton X-100.

GUV pulse-chase leakage assays

GUVs in GUV buffer lacking sucrose ([Lipid] = 50 μM) were mixed with 3TAT (1 μM) and then added to an optical glass 8-well plate (Nunc). Fluorescence images were captured of 3TAT-treated GUVs at indicated time points to detect leakage of calcein (FITC filter cube) and binding of peptide (RFP filter cube). Fluorescence intensity values reported are an average of the total intensity of calcein signal of the GUV at each indicated time point measured using SlideBook software.

LUV immobilization and leakage assay

A HiTrap protein A HP column (GE Healthcare) was loaded with 50 μg of anti-BMP (Echelon Biosciences). The antibody-loaded column was then treated with calcein-encapsulated BMP LUVs (250 μM lipid). Then, the immobilized BMP LUVs were treated with either LUV buffer (negative control), 0.2% Triton X-100 in LUV buffer (positive control), 3TAT (5 μM), calcein-free BMP LUVs (250 μM), or 3TAT (5 μM) immediately followed by calcein-free LUVs (250 μM) where indicated. Leakage of the immobilized LUVs’ calcein cargo was detected by absorbance using an Ultimate MWD-3000 as before. Leakage was then normalized to the positive and negative controls to yield a leakage percentage.

Lipid partitioning assays

Lipid films (corresponding to a final concentration of 3–3000 μM) composed of DOBMP or DOPG were dried in vacuo overnight. The following day, lipid films were resuspended via vortex mixing at the phase interface between 75 μL LUV buffer (pH 5.5) and 150 μL hexanes. Lipid partitioning was initiated upon the addition and mixing (via pipetting) of 3TAT to a final aqueous concentration of 3 μM. Phase separation was assisted by centrifugation at 2,000×g for 1 min. The hexane phase was then transferred to a 96-well plate, and the fluorescence of 3TAT was measured via a Tecan Infinite M200 Pro plate reader (λex = 556±9 nm, λem = 583±20 nm). The values were reported by normalization to a positive partioning control (fluorescence from aqueous 3 μM 3TAT) and negative partioning control (hexane alone).

Lipid packing assays

For in vitro lipid packing experiments, Di-4-ANEPPDHQ-labeled BMP or PG LE LUVs (250 μM) in LE LUV buffer (pH 5.5) were mixed with 10 μM 3TAT. Immediately following, lipid packing was determined by measuring the fluorescence of Di-4-ANEPPDHQ via a Tecan Infinite M200 PRO plate reader (λex = 488±9 nm, λem1 = 560±20 nm, λem2 = 650±20 nm). GP was then calculated with the following formula: GP = (I560 − I650) / (I560 + I650) (248,257). ΔGP was calculated by subtracting the GP of untreated BMP or PG LE LUVs from the GP of BMP or PG LE LUVs treated with 3TAT.

For lipid packing measurements in cells, CHO-K1 cells were cultured to a confluency of 70–100% on glass-bottom 8-well culture plates (Fisher). The cells were first treated with 5 μM Di-4-ANEPPDHQ in F12K medium (HyClone) containing 10% FBS for 45 min. This solution was removed, and the cells were washed twice with L15 medium (HyClone). Where indicated, cells were then treated with 10 μM 3TAT in L15 medium for 30 min. Following incubation, cells were washed twice with L15 containing heparin (1 mg/mL), once with L15, and then incubated in L15 + 10% FBS for imaging. Fluorescence microscopy was conducted using an Olympus IX-81 inverted microscope equipped with a 100× objective and heated stage (37°C). Images were captured using a Rolera-XR back-illuminated electron-multiplying CCD camera (Qimaging). Filters used in fluorescence imaging included DAPI (λex/λem = 300–388, 425–488 nm), FITC (Di-4-ANEPPDHQ channel 1) (λex/λem = 465–500, 510–560 nm) and IFRET (Di-4-ANEPPDHQ channel 2) (λex/λem = 450–490, 590–670 nm) filter cubes (Chroma Technology). GP was calculated via a macro for ImageJ.(Owen et al., 2011)

Lipid mixing assays

For lipid mixing assays, PG or BMP LUVs were mixed with their 10% py-PC PG or BMP LUV counterpart in a 1:1 ratio to a total lipid concentration of 500 μM. Where indicated, nf3TAT was added to the liposome mixture to a final concentration of 10 μM and a 1:50 peptide-to-lipid ratio. Fluorescence intensity was acquired of pyrene monomers and excimers (λex = 340 nm; λem(monomer) = 372 nm; λex(excimer) = 470 nm.) The extent of lipid mixing was determined by pyrene excimer dilution by taking the ratio of fluorescence intensity of the monomer over the fluorescence intensity of the excimer compared to that of positive and negative controls. The negative control consisted of 10% py-PC LUVs plus non-doped LUVs in the absence of peptide. The positive control consisted of 5% py-PC LUVs plus non-doped LUVs in the absence of peptide. The experimental determined ratio of monomer-to-excimer were then normalized to these controls to score lipid mixing via a lipid mixing index.

BAS experiments

BAS measurements are taken with a custom-built, multi-channel confocal microscope, as previously described (Brooks et al., 2015; Puchalla et al., 2008a). Built on a research quality, vibrationally isolated 4’ x 8’ optical table, the system is constructed around a Nikon Eclipse Ti-U inverted microscope base with a 60x/1.4NA CFI Plan Fluor oil-immersion objective. The microscope base is outfitted with a precision, 2-axis stepper motor sample stage (Optiscan II; Prior) and a custom-designed confocal optical bench with three independent detection channels. Each detection channel is configured with an optimized band-pass filter set for wavelength selection and a low-noise, single photon counting APD unit (SPCM-AQRH-15; Excelitas). Photon pulses are collected and time stamped with either a multichannel hardware correlator (correlator.com) or high speed TTL counting board (NI9402; National Instruments). Sample excitation is provided by a diode laser (642 nm; Omicron) and a diode-pumped solid-state laser (561 nm; Lasos). The free-space beams of each laser are each coupled to a 3-channel fiber combiner (PSK-000843; Gould Technologies) and the combined output is directed into the sample objective with a custom, triple-window dichroic filter (Chroma). Each laser is addressable from the integrated control and data acquisition software, custom developed using LabView (National Instruments).

Liposomes, diluted to 2.5 μM in LUV Buffer pH 5.5, were mixed with 3TAT (1–12.5 nM). Each sample was spotted onto a BSA-blocked glass coverslip held in a custom cassette. The coverslip cassette was clamped to a high-precision, computer controlled, 2-axis translation stage connected to a customized microscope system. For all experiments, dual excitation was employed with 50 μW input power (measured at the back of the objective) for both 488 nm and 561 nm lasers. For each experimental run, 5 min of fluorescence burst data was recorded and each experiment was repeated a minimum of three times. The TMR/DiD was calculated from the raw burst that were coincident in both channels.

Cryo-EM and image processing

BMP LUVs treated with 3TAT, and PG LUVs treated with 3TAT were frozen in vitreous ice on a Quantfoil R2/1 holey carbon grid with a FEI Vitrobot respectively. Cryo-EM images were acquired on a K2 Summit Direct-detection camera (Gatan) in the electron-counting mode using a TECNAI F20 cryo-electron microscope (FEI) operated at 200 kV. A nominal magnification of 19000x or 7800x was used, giving a pixel size of 1.87 Å/pixel or 4.8 Å/pixel, respectively. Bilayer thickness was measured using ImageJ.

Transmission Electron Microscopy

At 3 μM, 3TAT is able to successfully permeabilize endosomes and promote efficient cytosolic delivery in approximately 50% of cells while being non-toxic (<5% cell death). Increasing the incubation concentration of the peptide improves delivery efficiency but also promotes cell death. In contrast, dfTAT (at 5 μM) achieves cytosolic delivery in more than 95% of cells with less than 5% toxicity.(Erazo-Oliveras et al., 2014) Therefore, we used dfTAT instead of 3TAT to prepare samples for transmission electron microscopy, so as to image cells that have undergone endosomal leakage while avoiding the caveat of having dead cells contaminating the sample. HeLa cells were plated on Lab-Tek Permanox chamber slides (Milipore Sigma C7182). Cells were treated with peptide for 1 h then fixed with Trump’s fixative (McDowell & Trump, 1976) for 1 h at room temperature. Subsequent processing was performed using a Pelco Biowave microwave processor (Ted Pella, Inc., Redding, CA) equipped with ColdSpot technology. The chiller was set to 20°C and a vacuum was used for all fixation and washing steps. Slides were fixed at 150W power with a 1–3-1–2 cycle (1 min on, 3 min off, 1 min on, 2 min off), followed by 10 s on, 20 s off, and 10 s on at 650W. Slides were washed three times in Trump’s buffer (1 min, 150W), then washed twice in water (1 min, 150W). Cells were post-fixed with 1% OsO4 (2 min on, 2 min off for 5 cycles, 100W), followed by a water wash (1 min, 150W). Samples were stained with uranyl acetate for 30 min at room temperature in the dark, rinsed twice in water (1 min, 150W), followed by dehydration using the following percentages of ethanol concentrations: 30%, 50%, 70%, 90%, 100%, 100%, 100% (1 min, 150W, no vacuum). Samples were embedded in a modified Quetol/Spurr’s resin mixed 1:1 with ethanol (3 min, 150W), followed by resin only three times (3 min, 200W, in vacuo). Samples were set in a 60°C oven for 36 hr to polymerize. Once polymerization was complete, the slide was separated from the chambers, leaving a monolayer of cells on the face of resin blocks. Ultrathin sections (60–90 nm thick) were cut parallel with the face of the block on Leica UC7 ultramicrotome and picked on 200 mesh copper grids. The grids were then stained with 2% uranyl acetate for 5 min, and Reynolds’ lead citrate for 5 min. Images were processed on ImageJ. Multivesicular bodies, late endosomes, endolysosomes and lysosomes were identified by morphology.(Huotari and Helenius, 2011) Their numbers were counted manually using as set of 5 images per cell. Each experiment was duplicated and 5 cells were imaged for each experiment. The number of organelles present was normalized to the overall cell area imaged, as determined on ImageJ.

Parametrization and simulation parameters

In order to obtain atomistic level of details of 3TAT interaction with POPG and BMP membranes, respectively, we performed extensive all-atom molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. In this regard, we used Slipids force field to describe POPG and 2,2’-BMP (BMP in following text), while we parameterized 3TAT protein using Amberff99SB force field.(Enkavi et al., 2017; Hornak et al., 2006; Jambeck and Lyubartsev, 2012a, b) Bonded and non-bonded parameters of central lysine residue were used to describe non-standard residue appearing in 3TAT, namely bridging lysine (LM), only head group of this residue being re-parameterized according to Amberff99SB force field scheme. Water was described using TIP3P model, while parameters for counterions (sodium ions) were described using improved and AMBER force fields consistent parameter set.(Joung and Cheatham, 2008) The simulations were performed in GROMACS 2018 with a time step of 2 fs (leap-frog algorithm), van der Waals and short-range Coulomb cut-offs of 1.2 nm, three-dimensional periodic boundary conditions, and applying the particle mesh Ewald procedure used to properly treat long-range electrostatic interactions.(Hess et al., 2008) A Nosé-Hoover thermostat with a coupling constant of 0.5 ps was utilized to maintain the temperature at 310 K.(Essmann et al., 1995; Hoover, 1985; Nosé, 1984; NosÉ, 2002) Two temperature coupling groups were introduced in all performed MD simulations, first consisting of all protein and lipid atoms, with the second one containing all water and counterion atoms, thus ensuring proper heating of the system. Furthermore, Parrinello-Rahman barostat with a semi-isotropic coupling scheme and a coupling constant of 2 ps was employed to keep the system at a constant pressure of 1 bar.(Parrinello and Rahman, 1980, 1981) Moreover, LINCS constraint algorithm was used to constrain the length of all bonds present in the system. Finally, both energy and pressure long-range dispersion corrections were taken into account.

System setup

We prepared two different system setups for both lipid-protein combinations (POPG–3TAT and BMP–3TAT), namely single bilayer and double bilayer setup. Initially, we used CHARMM-GUI and Packmol to create single bilayer systems corresponding to POPG and BMP membranes, respectively.(Jo et al., 2008; Martínez et al., 2009) Both systems consist of 192 lipid molecules (96 lipids per layer), one 3TAT protein, approximately 29000 water molecules and 164 sodium counterions (charge of 3TAT is q=+28e). Starting POPG–3TAT and BMP–3TAT simulation box dimensions were 8.3×8.3×18.0 and 8.6×8.6×18.3 nm3, respectively. Both single bilayer systems were minimized using steepest descent method and relaxed following standard procedure (position restraints on both protein and lipid atoms were set to 1000, 400 and 200 kJmol−1nm−2, with 100, 100 and 200 ps simulation times, respectively). Afterwards, 110 ns of unrestrained NPT simulations (see details above) were propagated, with first 10 ns omitted from the analysis, as this constitutes initial equilibration period. On the other hand, double bilayer systems (POPG–3TAT–POPG and BMP–3TAT–BMP) were prepared starting from corresponding equilibrated single bilayer systems. More precisely, equilibrated single bilayer was, for both cases, duplicated and shifted by ≈ 2.5 nm in the z-direction (direction normal to bilayers). The resulting systems consist of two lipid bilayers (192 lipids in each bilayer), 4940 water molecules, 160 sodium ions and 3TAT protein in the inner region, with the remainder of water molecules (≈ 11000) and 196 sodium ions belonging to the outer region (see Figure S5). Both POPG and BMP double bilayer simulations were first propagated for 2 ns with 1000 kJmol−1nm−2 position restraints on protein atoms and lipid head groups. Production MD was performed without restraints in NPT ensemble (see details above) for 1 μs.

Quantification and Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed in Microsoft Excel. Standard deviations were calculated using the STDDEV.S function to calculate the standard deviation of a given sample. To determine comparative significance, Microsoft Excel’s two-sample t-test assuming equal variances was performed where applicable and standard “star” nomenclature was used to report probability of a type I error (*:p<0.05/**:p<0.01/***:p<0.001). Values reported in experiments are the mean of triplicate assays results (n=3) unless otherwise specified. Statistical details of individual experiments can be found in the corresponding figure legends including when standard deviations were taken.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

CPP-mediated leakage of membranes mimicking late endosomes requires bilayer contact.

The presence and abundance of BMP are primary determinants of leakage.

CPPs promote leakage by being encapsulated by BMP at contact sites.

BMP uniquely promotes CPP encapsulation which leads to escape from late endosomes.

Significance Paragraph.

In this work, a unique mechanism by which an analog of the prototypical cell-penetrating peptide (CPP) TAT enters human cells is derived from a combination of cell-based assays, in vitro experiments with lipid bilayer models, and computational simulations. The proposed mechanism explains how the CPP causes the specific leakage of late endosomes and the subsequent release of endosomally-entrapped macromolecular cargos. The CPP interacts with bis(monoacylglycerol)phosphate (BMP), an anionic lipid found in late endosomes. This interaction leads to the formation of bilayer contact sites between adjacent intraluminal vesicles. BMP is uniquely able to encapsulate the CPP, an event that opens pores at contact sites.

The mechanism described herein departs from other models of membrane translocation. In contrast to the idea that CPPs cross single bilayers, this work shows that membrane translocation requires the encapsulation of CPPs between multiple bilayers brought into close contact. This perspective provides an explanation for the unresolved phenomenon of endosomal escape, establishes a framework for why certain CPPs are efficient at entering cells while others are not, and provides a molecular foundation for the design of future cellular delivery tools.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by award R01GM110137 (J.-P.P.), R01GM11405 (H.R.), and R21AI137696 (J.Z.) from the US National Institute of General Medical Sciences. The authors also acknowledge support from the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (grant RP190655, J.-P.P.), the National Science Foundation (grant 1902392, J.Z.), the Welch Foundation grant (A-1863, J.Z.). Z. B. and M. V. thank the Croatian Science Foundation, project no. IP-2019-04-3804. We thank the computer cluster Isabella located in SRCE - University of Zagreb, Croatia, University Computing Centre for computational resources. We thank the Microscopy and Imaging Center at Texas A&M University for providing instrumentation for cryo-EM data collection. We also thank Christoph Allolio for useful discussions on MD simulations. We thank Dr. Justine deGruyter for editing the manuscript.

Footnotes

Competing Financial Interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Allen J, Najjar K, Erazo-Oliveras A, Kondow-McConaghy HM, Brock DJ, Graham K, Hager EC, Marschall ALJ, Dubel S, Juliano RL, et al. (2019). Cytosolic Delivery of Macromolecules in Live Human Cells Using the Combined Endosomal Escape Activities of a Small Molecule and Cell Penetrating Peptides. ACS Chemical Biology 14, 2641–2651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allolio C, Magarkar A, Jurkiewicz P, Baxova K, Javanainen M, Mason PE, Sachl R, Cebecauer M, Hof M, Horinek D, et al. (2018). Arginine-rich cell-penetrating peptides induce membrane multilamellarity and subsequently enter via formation of a fusion pore. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115, 11923–11928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews NW, and Corrotte M (2018). Plasma membrane repair. Curr Biol 28, R392–R397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appelbaum JS, LaRochelle JR, Smith BA, Balkin DM, Holub JM, and Schepartz A (2012). Arginine topology controls escape of minimally cationic proteins from early endosomes to the cytoplasm. Chemistry & biology 19, 819–830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blum AP, Nelles DA, Hidalgo FJ, Touve MA, Sim DS, Madrigal AA, Yeo GW, and Gianneschi NC (2019). Peptide Brush Polymers for Efficient Delivery of a Gene Editing Protein to Stem Cells. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 58, 15646–15649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brock DJ, Kustigian L, Jiang M, Graham K, Wang TY, Erazo-Oliveras A, Najjar K, Zhang J, Rye H, and Pellois JP (2018). Efficient cell delivery mediated by lipid-specific endosomal escape of supercharged branched peptides. Traffic (Copenhagen, Denmark) 19, 421–435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks A, Shoup D, Kustigian L, Puchalla J, Carr CM, and Rye HS (2015). Single particle fluorescence burst analysis of epsin induced membrane fission. PLoS One 10, e0119563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevallier J, Chamoun Z, Jiang G, Prestwich G, Sakai N, Matile S, Parton RG, and Gruenberg J (2008). Lysobisphosphatidic acid controls endosomal cholesterol levels. J Biol Chem 283, 27871–27880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enkavi G, Mikkolainen H, Gungor B, Ikonen E, and Vattulainen I (2017). Concerted regulation of npc2 binding to endosomal/lysosomal membranes by bis(monoacylglycero)phosphate and sphingomyelin. PLoS Comput Biol 13, e1005831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erazo-Oliveras A, Najjar K, Dayani L, Wang T-Y, Johnson GA, and Pellois J-P (2014). Protein delivery into live cells by incubation with an endosomolytic agent. Nat Meth 11, 861–867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erazo-Oliveras A, Najjar K, Truong D, Wang TY, Brock DJ, Prater AR, and Pellois JP (2016). The Late Endosome and Its Lipid BMP Act as Gateways for Efficient Cytosolic Access of the Delivery Agent dfTAT and Its Macromolecular Cargos. Cell Chem Biol 23, 598–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essmann U, Perera L, Berkowitz ML, Darden T, Lee H, and Pedersen LG (1995). A smooth particle mesh Ewald method. The Journal of Chemical Physics 103, 8577–8593. [Google Scholar]

- Gibert M, Petit L, Raffestin S, Okabe A, and Popoff MR (2000). Clostridium perfringens iota-toxin requires activation of both binding and enzymatic components for cytopathic activity. Infect Immun 68, 3848–3853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruenberg J (2020). Life in the lumen: The multivesicular endosome. Traffic (Copenhagen, Denmark) 21, 76–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafez IM, Maurer N, and Cullis PR (2001). On the mechanism whereby cationic lipids promote intracellular delivery of polynucleic acids. Gene Ther 8, 1188–1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hameed DS, Sapmaz A, Gjonaj L, Merkx R, and Ovaa H (2018). Enhanced Delivery of Synthetic Labelled Ubiquitin into Live Cells by Using Next-Generation Ub-TAT Conjugates. Chembiochem : a European journal of chemical biology 19, 2553–2557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helenius A (2018). Virus Entry: Looking Back and Moving Forward. J Mol Biol 430, 1853–1862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess B, Kutzner C, van der Spoel D, and Lindahl E (2008). GROMACS 4: Algorithms for Highly Efficient, Load-Balanced, and Scalable Molecular Simulation. J Chem Theory Comput 4, 435–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoover WG (1985). Canonical dynamics: Equilibrium phase-space distributions. Phys Rev A Gen Phys 31, 1695–1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornak V, Abel R, Okur A, Strockbine B, Roitberg A, and Simmerling C (2006). Comparison of multiple Amber force fields and development of improved protein backbone parameters. Proteins 65, 712–725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huotari J, and Helenius A (2011). Endosome maturation. EMBO J 30, 3481–3500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jambeck JP, and Lyubartsev AP (2012a). Derivation and systematic validation of a refined all-atom force field for phosphatidylcholine lipids. J Phys Chem B 116, 3164–3179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jambeck JP, and Lyubartsev AP (2012b). An Extension and Further Validation of an All-Atomistic Force Field for Biological Membranes. J Chem Theory Comput 8, 2938–2948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo S, Kim T, Iyer VG, and Im W (2008). CHARMM-GUI: A web-based graphical user interface for CHARMM. Journal of Computational Chemistry 29, 1859–1865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joung IS, and Cheatham TE 3rd (2008). Determination of alkali and halide monovalent ion parameters for use in explicitly solvated biomolecular simulations. J Phys Chem B 112, 9020–9041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi T, Beuchat MH, Chevallier J, Makino A, Mayran N, Escola JM, Lebrand C, Cosson P, Kobayashi T, and Gruenberg J (2002). Separation and characterization of late endosomal membrane domains. J Biol Chem 277, 32157–32164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi T, Stang E, Fang KS, de Moerloose P, Parton RG, and Gruenberg J (1998). A lipid associated with the antiphospholipid syndrome regulates endosome structure and function. Nature 392, 193–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi T, Startchev K, Whitney AJ, and Gruenber J (2001). Localization of lysobisphosphatidic acid-rich membrane domains in late endosomes. Biological chemistry 382, 483–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lian X, Erazo-Oliveras A, Pellois JP, and Zhou HC (2017). High efficiency and long-term intracellular activity of an enzymatic nanofactory based on metal-organic frameworks. Nat Commun 8, 2075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez L, Andrade R, Birgin EG, and Martínez JM (2009). PACKMOL: A package for building initial configurations for molecular dynamics simulations. Journal of Computational Chemistry 30, 2157–2164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuo H, Chevallier J, Mayran N, Le Blanc I, Ferguson C, Faure J, Blanc NS, Matile S, Dubochet J, Sadoul R, et al. (2004). Role of LBPA and Alix in multivesicular liposome formation and endosome organization. Science 303, 531–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najjar K, Erazo-Oliveras A, Mosior JW, Whitlock MJ, Rostane I, Cinclair JM, and Pellois JP (2017). Unlocking Endosomal Entrapment with Supercharged Arginine-Rich Peptides. Bioconjug Chem 28, 2932–2941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]