Abstract

Genomic DNA is replicated every cell cycle by the programmed activation of replication origins at specific times and chromosomal locations. The factors that define the locations of replication origins and their typical activation times in eukaryotic cells are poorly understood. Previous studies highlighted the role of activating factors and epigenetic modifications in regulating replication initiation. Here we review the role that repressive pathways – and their alleviation – play in establishing the genomic landscape of replication initiation. Several factors mediate this repression, in particular, factors associated with inactive chromatin. Repression can support organized, yet stochastic replication initiation, and its absence could explain instances of rapid and random replication or of re-replication.

Keywords: DNA replication initiation, DNA replication timing, Negative regulation, Chromatin structure

Activation and repression at the basis of biological regulation

The most intuitive way to think of the occurrence of a biological event is in terms of its driving factors. The early days of molecular biology taught us a non-intuitive lesson, that it may be repression, rather than activation, that forms the basis of gene expression regulation. Instead of a positive factor(s) that initiates gene expression, the pioneering work of Jacob and Monod emphasized the power of negative regulation to influence the state of a cell [1]. Thus, relief of repression was shown to be the main event that drives gene activity in the lac operon model. Subsequent research established that gene regulation is mediated by a complex network of interacting factors with positive, negative, and conditional effects.

Interestingly, not long after proposing the operon theory, François Jacob, together with Sydney Brenner and François Cuzin, postulated the “replicon model” to explain the regulation of bacterial chromosome replication [2]. In contrast to the regulation of operon gene expression, replication was proposed to be fundamentally controlled by activation. Accordingly, the replicon model posits a positive factor – the “initiator” – that binds a cis-acting DNA element (see Glossary) – the “replicator” – to initiate DNA synthesis at the bacterial replication origin. While the replicon model proved to be an accurate description of bacterial chromosome replication, the elucidation of how DNA replication is regulated in eukaryotic, and especially metazoan genomes, is still intensely debated. Just like transcription, we now appreciate that replication origins are regulated by a complex mechanism that involves the coordinated activity of multiple factors. But perhaps history, and intuition, have poised us to focus on positive regulators and pay less attention to the importance of negative regulation of DNA replication.

The elusive regulation of mammalian DNA replication initiation

DNA replication, predominantly, initiates at specific sites along eukaryotic genomes [3, 4]. During late mitosis and early G1 phase, specific chromosomal locations are “licensed” by binding of the Origin Recognition Complex (ORC, see Glossary) [3]. ORC serves as a scaffold for the subsequent association of CDC6 and CDT1, which together coordinate the loading of the MCM2–7 replicative helicase complex to form the pre-replication complex (pre-RC) [5]. The activity of cyclin- and DBF4-dependent kinases (S-CDKs and DDK, respectively) at the G1-to-S phase transition trigger the assembly of the pre-initiation complex (pre-IC) by recruiting Treslin/TICCR, RECQL4, MTBP, CDC45, TOPBP1 (or their yeast orthologs) and other proteins to origin sites. Throughout S phase, phosphorylation of MCM subunits by DDK, and of other initiation factors by CDK, results in helicase activation, DNA unwinding, and further recruitment of DNA polymerases and other replication factors; this forms functional replisomes that mediate bidirectional DNA synthesis [3, 6]. Throughout this review, we use “replication initiation” to broadly refer to all three steps (licensing, pre-IC formation, and origin firing). The main factors that define a genome’s replication dynamics are the locations of licensed replication origins, which of the licensed origins ultimately fire in S phase, and the time at which they fire [7]. None of these are well understood. In the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae and closely related species, replication origins are defined by a consensus DNA sequence that serves as the binding site for ORC. ORC also shows sequence preference in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe, where it recognizes AT-rich sequences of ~1 Kb in length [8]. However, the specification of ORC binding and replication origin sites in higher eukaryotes do not seem to show a preference for any specific sequence contexts [4, 9]. Instead, ORC binds promiscuously to any DNA sequence [10–14]. Single-cell and single-molecule studies, such as DNA combing (see Glossary), have revealed that in higher eukaryotes, as in yeasts, origin firing at a given location is stochastic and/or inefficient [15–18]. Nonetheless, molecular experiments and genome-wide measurements of replication dynamics or origin positions indicate that replication initiates at defined chromosomal locations [7]. Thus, it appears that the predictable pattern of replication dynamics emerges from stochastic origin firing across chromosomes, likely because certain genomic regions have a higher likelihood to serve as initiation sites.

The molecular identity of the factors that drive preferential initiation at defined genomic regions in higher eukaryotes has been the subject of intense investigation. Since primary sequence has been ruled out as a main driver, chromatin-mediated protein binding – with an emphasis on activating factors – has emerged as the focal point of the efforts to understand replication origin specificities. Indeed, numerous studies have implicated a host of histone modifications and other DNA-binding factors as required for defining replication origin sites. For example, accessible chromatin has been associated with replication origin sites and early replication, as have histone modifications that promote open chromatin, such as histone tail acetylations [19–25]. However, neither individually nor in combination do these factors provide an accurate prediction of where replication initiates, nor are they sufficient to explain the specific timing at which each replication origin fires. A clear picture has yet to emerge regarding what actually defines the chromosomal sites and timing of replication origin firing.

Molecular mechanisms of replication repression

In addition to positive factors that promote replication initiation, negative regulation of replication initiation has been proposed more than two decades ago [26]. Since then, evidence has been accumulating that negative factors, or repressors, influence origin function and replication activity (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Repressive Regulatory Factors Involved in DNA Replication Initiation.

Shown are some of the known regulators that repress replication activity by interacting with replication initiation factors. Colored shapes represent key components of the replication machinery. Double arrows indicate association, interaction or binding. Single arrows indicate stabilization, activation or catalyzation. Bar-headed arrows indicate negative regulation. DNA methylation and transcription could also repress DNA replication. Abbreviations – ORC: origin recognition complex; ORCA: ORC-associated; MCM: mini-chromosome maintenance complex; DDK: DBF4-dependent kinase; HP1: heterochromatin protein 1; KMT: histone lysine methyltransferase; PP1: protein phosphatase 1.

First, although the ORC itself exhibits non-specific DNA binding, chromatin appears to repress its binding throughout many genomic regions. For example, although sequence-based (ARS) assays (see Glossary) predict 798 active origins across the S. cerevisiae genome, only 269 of those show evidence of ORC binding in vivo [27]. In-vitro, replication assays with chromatinized templates showed that chromatin enforces replication origin specificity by repressing non-specific ORC binding and MCM loading [28–30]. In human cells, excessive ORC loading during G1 is prevented by fine-tuning chromatin relaxation through KMT5A (PR-Set7/ SET8)-dependent monomethylation of H4K20 [31]. It appears that chromatin can confer specificity by repressing activity across most of the genome; the regions less subject to this repression could be more likely to give rise to active origins. For example, nucleosome-free regions are a main feature of replication origins [32, 33].

Intriguingly, ORC itself has been implicated as a component of repressive chromatin and as required for its formation. Specifically, Drosophila, Xenopus and human ORC associate with heterochromatin and HP1 (heterochromatin protein 1) [34, 35], which recognizes repressive histone H3K9 methylation and spreads heterochromatin [36]. In addition, ORC has been shown in human cells to bind to the three most prominent transcriptional repressive histone lysine methylations – H3K9me3, H3K27me3 and H4K20me3 [37]. These interactions also involve ORCA (ORC-associated)/LRWD1, a protein conserved in higher eukaryotes that stabilizes ORC on chromatin and facilitates pre-RC assembly [38, 39]. ORCA co-localizes with ORC at heterochromatic regions, binds H3K9me3 and a complex of histone methyltransferases (including the H3K9 methyltransferase G9A), and is required for heterochromatin organization via facilitation of H3K9 di- and trimethylation [37, 40].

In budding yeast as well, ORC is involved in the formation of heterochromatin and is required for silencing [41, 42]. The MCM complex is also bound to some heterochomatic sites, even in the absence of origin firing [43]. The functions of ORC in replication and heterochromatin may be separable [44], and at least at some loci, weak ORC-DNA interactions are conducive to replication while stronger interactions promote heterochromatin formation [45]. However, in the fission yeast S. pombe, early replication of pericentromeric regions and the mating type locus is mediated by the HP1 counterpart, Swi6, which interacts with DDK at these sites [46]. Thus, it appears that heterochromatin components can, at least in certain situations, promote replication initiation and early replication.

Sir proteins represent a further link between heterochromatin proteins and replication origins. In budding yeast, the histone deacetylase Sir2, and the heterochromatic nucleosome binding protein, Sir3, are negative regulators of DNA replication at the level of pre-RC assembly [47]. Sir proteins are recruited to DNA via ORC and other replication factors [48]. Despite being typically described as components of repressive (and late-replicating) chromatin, they were recently shown to act on the 2–4 nucleosomes, immediately adjacent to early replication origins, where they inhibit MCM complex loading [49].

Another emerging replication repressor is RIF1. Originally identified as a telomeric protein in yeast, RIF1 has since emerged as perhaps the strongest negative (and arguably the only so far) regulator of DNA replication timing from yeast to humans [50, 51]. In particular, while RIF1 has a positive role in stabilizing ORC1 and promoting origin licensing in G1 cells [52], its main effect appears to be repression of replication. In yeast [53], flies [54], and mammalian cells [55], RIF1 inactivation appears to predominantly relieve repression of late replication origin firing, causing advanced firing of many origins. Concomitantly, some normally early origins appear to become delayed in RIF1-mutated cells, which may be a secondary effect related to competition among the excess of advanced (and thus early-firing) origins for limited replication factors [55]. Rif1 represses replication by directing Protein Phosphatase 1 (PP1) to reverse Cdc7-mediated phosphorylation of the MCM complex [52, 56–61]. Recently, RIF1 was found to inhibit replication fork progression in Drosophila [62] and to restart and/or protect stalled replication forks in yeast, mouse and humans [63–65]. Interestingly, at least in the rDNA region of budding yeast, Rif1 appears to work together with Sir2 to repress replication [66].

Repression of pre-IC formation and origin firing has been well described to occur under genotoxic stress via activation of cell cycle checkpoints [67–69]. However, accumulating evidence suggests that these same checkpoint pathways can be active and repress pre-IC formation and origin firing, even in normal cell cycles [70, 71]. For example, in Xenopus laevis egg extracts, ATR kinase inhibitors induce excessive origin firing during unperturbed DNA replication [71]. This effect has been shown to be mediated, at least in part, by ATR/CHK1 stabilizing the RIF1-PP1 interaction [72]. In turn, ATR is activated by TOPBP1, which by doing so represses the activity of dormant replication origins while being an integral part of the pre-IC. Human cells expressing a mutant TOPBP1 that loses its ATR-activation domain have increased number of fired origins [73]. Similarly, human Chk1 phosphorylates Treslin/TICCR, which inhibits CDC45 loading and pre-IC formation during normal cell cycles [70, 74]. This inhibiting phosphorylation occurs on a metazoan-specific C-terminal domain that also binds the acetylated histone binding proteins BRD2 and BRD4 [20]. It remains to be determined whether CHK1-mediated replication repression through Treslin/TICCR and via RIF1 are mechanistically related to each other. Taken together, several central cellular pathways, such as checkpoint responses and RIF1, may contribute to the shaping of the replication initiation landscape by functioning as replication repressors.

A few other notable factors have been implicated as negative regulators of replication. These include the NCOA4 transcriptional coactivator, which interacts with MCM and represses replication origin activation [75]; DNA methylation, which is repressive for replication initiation across many genomic regions including at imprinted genes, where it is associated with both gene silencing and allele-specific replication delays [76]; and other factors such as CTCF and cohesin subunits, which delay local replication timing when bound to DNA [77]. Recent evidence also suggests that transcription in G1 might itself suppress replication origin firing within genes [78, 79].

Synergy among inhibitory histone modifications promotes replication initiation

Another mode of replication repression, related to histone modifications, is emerging as having a potentially fundamental role in shaping the replication initiation landscape. As noted above, histone acetylation, which is often associated with accessible chromatin, has been implicated in promoting replication initiation and early replication across species [23–25]. However, histone modifications that are generally thought to be repressive may also be involved in specification of human replication initiation activity.

Individual histone H3 trimethylation marks on lysines 4, 9, and 36 are typically linked to repressed replication. H3K9me3 is predominantly associated with repressive heterochromatin and replication repression [80] (although it has also been observed in the bodies of actively transcribed genes, where it recruits HP1γ to promote efficient transcriptional elongation [81]). H3K4me3, although enriched at active promoters and correlated with early replication, has also been suggested to repress origin firing. Elevation of H3K4me3 at replication origins is associated with origin activation failures, reduced DNA synthesis, and a lengthened S phase [82]. H3K36me3 was also shown to be inhibitory for origin firing in budding yeast [83]. Nonetheless, H3K9me3 KDM4 demethylases appear to alleviate replication repression and promote pre-IC formation and origin firing [84]. Similarly, H3K4me3 demethylation by KDM5C was shown to be a required step for proper pre-IC assembly and origin firing [82].

Other histone marks and combinations may also have dual influences on replication initiation, functioning as either repressors or activators, depending on the presence of other epigenetic modifications and potentially depending on genomic context. For example, H4K20me1 represses replication licensing in G1 by maintaining compact chromatin at the M-to-G1 transition [31]. On the other hand, H4K20me1 and H4K20me3 (which themselves are associated with pericentromeric heterochromatin and imprinting control regions) have been implicated in promoting pre-RC formation. For example, artificial tethering of the KMT5A H4K20 mono-methyltransferase to a specific genomic locus promotes pre-RC formation, and inhibition of KMT5A alters replication origin firing and replication fork progression [85, 86]. H4K20me2 recruits ORC1 [87] (through its BAH domain; [88]), while H4K20me3 recruits ORCA/LRWD1 to specific genomic loci [89]. Another example is mouse chromocenters. These constitutive heterochromatic regions are enriched with H3K9me3, poor in histone acetylation, and replicate late. However, ectopic hyperacetylation of these regions lead to their early replication [90], suggestive of a synergistic interaction between H3K9me3 and histone acetylations that promotes replication.

Work from a number of groups has shown that combinations of trimethylations on H3K4, H3K9, and H3K36 can exert a cross-talk through their tri-demethylases that facilitates site-specific replication origin firing [91, 92]. Specifically, H3K4me3 serves as a “landing pad” for the KDM4 family of histone lysine tri-demethylases that target H3K9me3 and H3K36me3 [92–94]. KDM4 proteins, in turn, bind the replication machinery, including ORC, the MCM complex, PCNA and DNA polymerases [84, 91]. KDM4D, which demethylates H3K9me3, is essential for pre-IC formation and origin firing, and interacts with replication proteins during the G1 and S phase. Its depletion causes reduced or delayed binding of CDC45, PCNA, and DNA polymerase δ to DNA [84]. In addition to their role in replication initiation, KDM4 proteins also affect replication elongation. Fork speed is substantially reduced in KDM4D-depleted cells [84]. H3K4me3 itself is a substrate for KDM5 histone demethylases [93], of which KDM5C binds H3K9me3 [95]. KDM5C, which is predominantly expressed during the S phase (but also lowly expressed during G1), also plays an essential role in pre-IC assembly and loading of the PCNA polymerase clamp and the CDC45 replication factor onto DNA [82]. In addition, HP1, while recognizing methylated H3K9, also associates with the H3K36 demethylases KDM2A and KDM4A [96, 97]. Together, the activities of histone H3 methyltransferases and demethylases and consequently, levels of H3K4me3, H3K9me3 and H3K36me3 comprise a delicate system that controls pre-IC formation and origin firing (Figure 2). While it is conceivable that open chromatin is what ultimately enables replication initiation as a passive function of histone modification states, it has also been suggested that direct interactions of histone lysine demethylases with the replication machinery is the crucial driver of replication in these chromatin contexts [91]. Although many details remain to be elucidated, together these lines of evidence point to combinations of individually repressive (or weakly activating) histone modifications synergizing to robustly promote pre-IC formation and origin firing.

Figure 2. Trimethylations on Lysines 4, 9, and 36 of Histone H3 and their Demethylases are Essential for Pre-IC Formation and Origin Firing.

Single arrows indicate facilitation of recruitment or stimulation. Double arrows indicate association, recognition, or binding. Bar-headed arrows indicate demethylation. Abbreviations – KDM: histone demethylase, HP1: heterochromatin protein 1; ORC: origin recognition complex, MCM: mini-chromosome maintenance complex; CDC45: cell division cycle protein 45; PCNA: proliferating cell nuclear antigen.

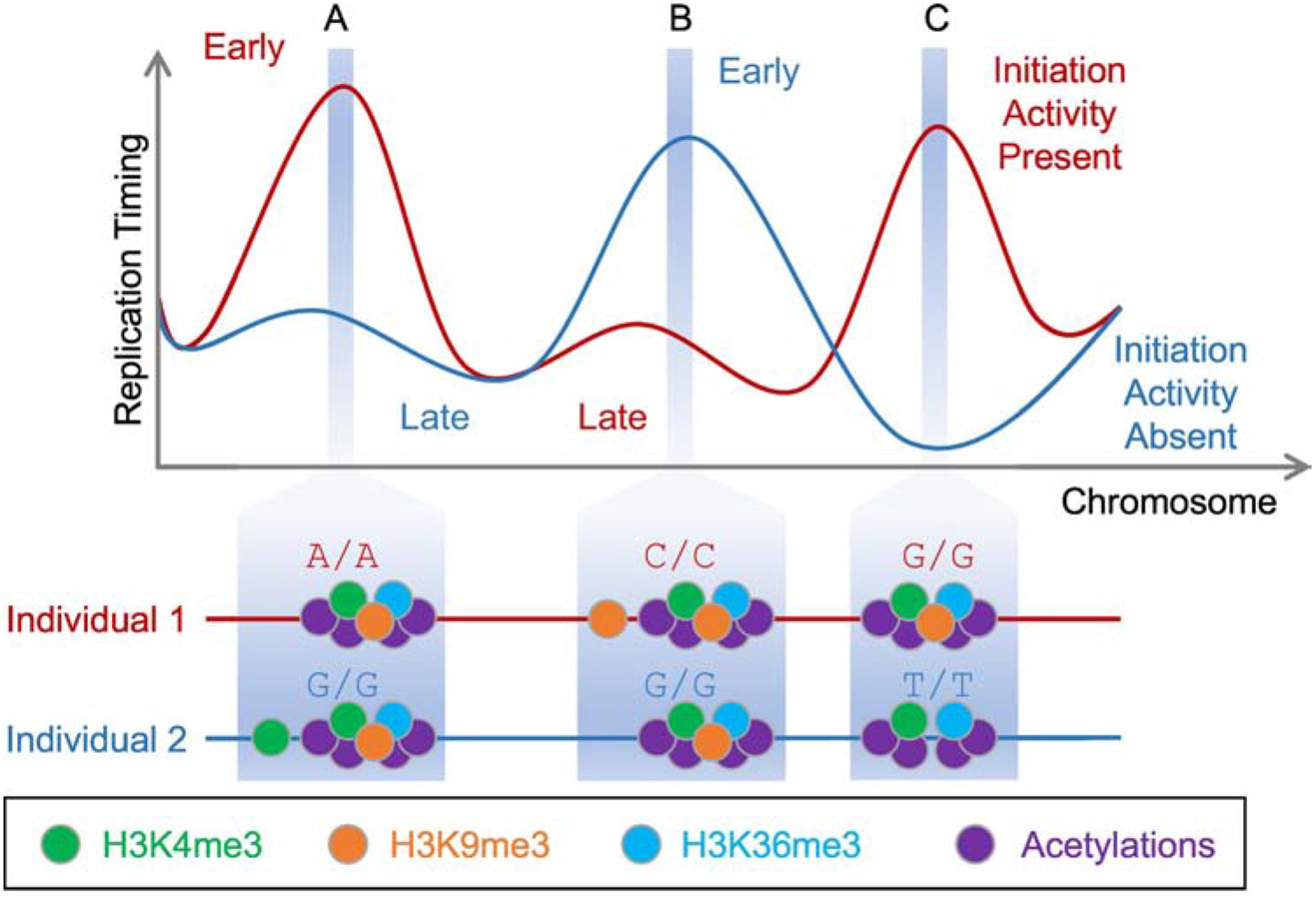

Emerging evidence suggests that this interaction mode, i.e., combinations of repressive histone modifications synergizing to promote replication, may be widespread across the genome and perhaps is even a general principle of human replication initiation. By studying cis-acting DNA sequences that associate with replication timing variation among people (rtQTLs) [98], a set of histone modifications were recently identified that correlate with both the locations of initiation sites as well as with replication timing. Histone methylation, in particular H3K4me3, H3K9me3 and H3K36me3, were individually repressive for replication and tended to associate with late origin activation. However, the combination of all three trimethylations at the same genomic loci was strongly associated with early replication (Figure 3). Furthermore, the presence of these three trimethylation marks on a background of general histone tail hyperacetylation accurately predicted the locations of the majority of active replication initiation sites across three different human cell types [77]. Thus, the genomic landscape of replication initiation may be determined in large part through the patterns of repressive chromatin marks and their combinations.

Figure 3. Combinations of Repressive Histone Modifications Specify Replication Initiation Sites.

Three replication initiation sites (A–C) are shown, in which combination of histone modifications – illustrated here as inter-individual genetic variation – affect replication activity and timing [77]. The two individuals illustrated in the figure have contrasting initiation activities because they carry different genotypes (i.e., genetic variants) at loci impacting abundance of histone trimethylations. Trimethylations of H3K4, H3K9 and H3K36 are individually repressive for early replication (A and B). However, when co-existing at the same genomic loci, and especially in combination with histone acetylations (C), they specify and strongly promote replication initiation.

A model of replication dynamics specified by alleviation of repression

The aforementioned evidence suggest that in addition to activating pathways, repression may play an integral part in DNA replication regulation, potentially at many genomic loci. We propose that specific combinations or patterns of fundamentally repressive mechanisms could interact with activating mechanisms to support an organized spatiotemporal program of DNA replication. This would apply to all steps of replication initiation, but perhaps more specifically to pre-IC formation and origin firing. Thus, replication can be poised for activation throughout the majority of the genome, yet restricted from doing so through various repressive mechanisms. At specific genomic loci, which harbor particular combinations of activating and repressive signals in specific conformations, replication initiation could be allowed to proceed effectively. The outcome is high specificity and selectivity of initiation sites, with the exact combination of activating and repressive factors ultimately determining whether a given site initiates replication, when, and how often. Initiation does not need to occur by a single mechanism under this model; instead, it is possible that several different combinations and genomic orientations of various chromatin factors could support replication initiation, perhaps with different efficiencies. An attractive possibility is that the active removal of repressive signals – rather than their mere absence – plays an important role in promoting replication. This is supported by the findings that several histone demethylases are required for replication activity, recruit proteins involved in pre-IC formation and origin firing, their overexpression induces re-replication, and their depletion causes replication defects [82, 84, 91, 92].

Taken together, we propose the counter-intuitive model, in which replication initiation is the default state, and specificity is fundamentally obtained via repression. Instead of a “no-replication” null, replication initiation is the default state in S phase. The replication machinery can then target, e.g., any open regions of chromatin, but is limited by repressive factors. Interactions between these repressive mechanisms, and potentially their active removal, is what ultimately enables replication to initiate. This leads to site-specific yet sequence-non-specific replication initiation in humans and likely other eukaryotes. Such a model would predict an inherently more complex regulatory system than if replication initiation was solely controlled by activating mechanisms (Figure 4). Various origins across the genome will have different levels and combinations of activating and repressive factors. Thus, for example, overexpression of limiting activating factors [99, 100] would have disproportional effects on different replication origins.

Figure 4. Repression Provides Flexibility for Replication Timing Regulation.

A model based predominately on activators (top) would predict a relatively simple, all-or-none activation mode. This model is less consistent with varying degrees of activation times and efficiencies. In contrast, a model that also incorporates repressors (bottom) enables higher flexibility and provides more opportunities for a complex initiation landscape. While individual repressors have a negative effect on replication, combinations of several repressors and activators can synergistically promote replication initiation. Arrows indicate facilitation of recruitment of replication origin proteins and/or activating factors. Bar-headed arrows indicate alleviation of repression. An intermediate model (not shown) would invoke a set of activators operating in a combinatorial manner. However, such a model is less parsimonious with fine-tuned replication initiation, mostly due to the enhanced regulatory mode configurations enabled by repression and the greater range of combinatorial modes enabled by two types of regulators. A model that incorporates repressive regulators also appears more consistent with cases of unordered replication and of re-replication.

Biological implications of replication regulation by repression

Regulation of DNA replication dynamics by repressive mechanisms entails several noteworthy implications. Some of them could provide new explanations for several phenomena that remain difficult to explain. At its most simplistic level, a repression-based model could explain how heterochromatin, which is generally refractory to DNA and RNA synthesis, is nonetheless fully replicated during normal S phases, including from embedded replication origins (as opposed to passively from nearby origins) [101]. Thus, the repressive factors that mediate heterochromatin also take part in mediating replication, albeit late in S phase.

Repression could also be more consistent with the excess of replication origins that are licensed but never activated [102]. Indeed, a (de-)repression mechanism for selection of active origins would predict that many more origins would be licensed than those that actually get activated. The observations that replication origin firing is stochastic despite appearing organized on a genomic level [103] could also be more easily reconcilable by invoking a complex system of activation and repression by many factors operating synergistically. Delicate combinatorial regulation offers more opportunities for small changes to influence the final outcome, thus is more consistent with stochastic replication initiation that nonetheless adheres to a spatiotemporal “program” hard-wired into the epigenome (see Glossary). The combination of activation and repression also offers more possibilities to realize different emergent properties of regulatory network motifs (see Glossary) [104], although a better understanding of replication regulation will be required before it can be ascribed specific regulatory modes as such. Interactions between several repressive and activating factors provides more combinatorial complexity, and more room for a variety of emergent spatiotemporal modes of replication initiation.

An interesting implication of regulation by repression is what might happen upon its loss. Under an activation-centric model of replication, loss of regulation would mean no replication at all (or rather, very inefficient replication). In contrast, if replication initiation proceeds by default, once cells enter S phase, and is normally repressed to provide specificity and order, then loss of regulation would be expected to lead to promiscuous replication initiation across the genome that is only limited by the availability of replication factors. Replication could then be unordered and seemingly random with respect to time and genomic space. Indeed, replication is known to be rapid and unstructured in early embryos of flies, frogs and fish [105–107]. A recent study in Xenopus laevis implicated the eviction of histone H1 by components of the histone chaperone FACT as enabling rapid unordered replication in embryos, while the presence of H1 suppressed replication and rendered it organized in somatic cells [108]. In flies, unstructured embryonic replication seems to be mediated by the absence of RIF1 repression of DNA replication [54]. RIF1 loss in human embryonic stem cell lines also causes a loss of the replication program [109]. Similarly, the female inactive X chromosome, which has an unusual facultative heterochromatin structure, replicates rapidly and randomly, without any apparent structure in human cells [98, 110, 111]. Repression of replication would predict that it would be possible to lose the replication timing program while still efficiently replicating an entire chromosome or the entire genome.

While loss of repression leading to random replication may be part of some normal developmental programs, at a more extreme level the failure to repress replication origins could lead to repeated activation of the same origin more than once within the same S phase. In other words, if repression is at the heart of replication initiation regulation, it might provide more opportunities for abnormal site-specific re-replication. Thus, despite the robust mechanisms that limit genome replication to once per cell cycle [112], mis-regulation of repressive mechanisms may lead to aberrant re-replication and copy number gains of specific genomic loci. The clearest example for this is the overexpression of the KDM4 tri-demethylases of H3K9me3 and H3K36me3 [91, 92]. Similarly, genetically bypassing the normal degradation of the histone 4 lysine 20 mono-methyltransferase KMT5A during S phase causes an increase in H4K20 methylation at origins and DNA re-replication [85, 113]. Aberrant re-replication may be even further promoted by increased levels of H4K20me3 [89]. Last, preventing SUMOylation of ORC2 at centromeres leads to diminished recruitment of KDM5A, elevated levels of H3K4me3, and re-replication [114].

Concluding Remarks

The factors that shape the landscape of DNA replication initiation in eukaryotic cells are not well understood. Here we have proposed that this landscape fundamentally depends on a combination of factors, some of which directly promote replication initiation at specific genomic locations while others repress initiation at the same or other locations. Moreover, repressive factors may become activating through interactions with enzymes that operate on repressive signals, while at the same time recruiting components of the replication machinery to DNA. We propose that these modes of replication initiation that are founded on repressive principles are responsible for a larger fraction of the replication landscape than typically thought. Considering replication initiation from the perspective of negative regulation would inform new directions of research into the factors that regulate DNA replication. It also has potential implications to the genomic, epigenomic and cellular manifestations of DNA replication dynamics. While there is much to learn about the regulation of replication dynamics (see Outstanding Questions), further research will continue to reveal the role of repressive mechanisms in shaping genomic replication patterns. Taken together, this review highlights previously underappreciated effects of negative regulators in replication initiation, and proposes a model for the regulation of replication dynamics that incorporates repressive factors and alleviation thereof.

Outstanding Questions.

What determines the locations of DNA replication origins in higher eukaryotes?

What determines the time of activation of DNA replication origins in eukaryotic species?

Is there a single mechanism for replication origin specification and activation, or rather many alternative ways to activate an origin?

How does chromatin structure influence DNA replication initiation? Is it sufficient to explain the replication landscape? And are there chromatin states that function specifically to regulate DNA replication?

Highlights.

DNA replication initiation in eukaryotic cells is mediated by a complex system, but its spatiotemporal regulation remains poorly understood.

While factors that promote replication are typically invoked to explain initiation patterns, evidence is accumulating for the involvement of a variety of repressive factors as well.

Combinations of repressive histone modifications may function in synergistic ways to promote site-specific replication initiation, possibly through the activity of histone mark erasers.

Considering both activation and repression as central to replication initiation could have important implications for the interpretation of DNA replication biology.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dashiell Massey, Matthew Edwards and Alexa Bracci for helpful comments on the manuscript. Work in the Koren lab is supported by the National Institutes of Health (award 1DP2GM123495) and the National Science Foundation (award MCB-1921341). The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Glossary:

- Cis-acting DNA element

DNA sequences that exert effects (in our case, replication initiation) locally, on the genomic regions in which they reside.

- DNA combing

A molecular technique in which labeled DNA is stretched on glass slides and visualized on a single-molecular level to identify patterns of replication initiation and progression.

- Epigenome

The collection of chemical modifications to DNA and to histone amino-acid residues. Examples include DNA methylation and histone lysine acetylation. The epigenome plays a critical role in many biological processes, e.g., gene expression and DNA replication.

- Origin Recognition Complex (ORC)

A protein complex that binds DNA replication origins in eukaryotes. It includes six subunits (ORC1–6) and has ATPase activity.

- Regulatory network motifs

Recurrent sub-graph patterns of regulatory interactions between proteins, for example positive feedback, or feed-forward loops.

- Sequence-based (ARS) assays

An assay in which candidate DNA sequences are inserted into an episomal plasmid and tested for their ability to confer autonomous replication of those plasmids in cells.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Jacob F and Monod J (1961) Genetic regulatory mechanisms in the synthesis of proteins. J Mol Biol 3 (3), 318–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jacob F et al. (1963) On the Regulation of DNA Replication in Bacteria. Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quant Biol 28, 329–348. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fragkos M et al. (2015) DNA replication origin activation in space and time. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 16, 360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prioleau M-N and MacAlpine DM (2016) DNA replication origins—where do we begin? Genes Dev 30 (15), 1683–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chong JPJ et al. (1995) Purification of an MCM-containing complex as a component of the DNA replication licensing system. Nature 375 (6530), 418–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boos D and Ferreira P (2019) Origin Firing Regulations to Control Genome Replication Timing. Genes 10 (3), 199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hulke ML et al. (2020) Genomic methods for measuring DNA replication dynamics. Chromosome Res 28 (1), 49–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Segurado M et al. (2003) Genome-wide distribution of DNA replication origins at A+T-rich islands in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. EMBO reports 4 (11), 1048–1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Comoglio F et al. (2015) High-resolution profiling of Drosophila replication start sites reveals a DNA shape and chromatin signature of metazoan origins. Cell reports 11 (5), 821–834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blow JJ et al. (2001) Replication origins in Xenopus egg extract Are 5–15 kilobases apart and are activated in clusters that fire at different times. The Journal of cell biology 152 (1), 15–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gros J et al. (2014) Origin plasticity during budding yeast DNA replication in vitro. The EMBO Journal 33 (6), 621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.MacAlpine HK et al. (2010) Drosophila ORC localizes to open chromatin and marks sites of cohesin complex loading. Genome Res 20 (2), 201–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vashee S et al. (2003) Sequence-independent DNA binding and replication initiation by the human origin recognition complex. Genes Dev 17 (15), 1894–1908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.On KF et al. (2014) Prereplicative complexes assembled in vitro support origin‐dependent and independent DNA replication. The EMBO Journal 33 (6), 605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patel PK et al. (2005) DNA Replication Origins Fire Stochastically in Fission Yeast. Molecular Biology of the Cell 17 (1), 308–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Czajkowsky DM et al. (2008) DNA Combing Reveals Intrinsic Temporal Disorder in the Replication of Yeast Chromosome VI. J Mol Biol 375 (1), 12–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frum RA et al. (2009) Temporal differences in DNA replication during the S phase using single fiber analysis of normal human fibroblasts and glioblastoma T98G cells. Cell Cycle 8 (19), 3133–3148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cayrou C et al. (2011) Genome-scale analysis of metazoan replication origins reveals their organization in specific but flexible sites defined by conserved features. Genome Res 21 (9), 1438–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miotto B and Struhl K (2008) HBO1 histone acetylase is a coactivator of the replication licensing factor Cdt1. Genes Dev 22 (19), 2633–2638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sansam CG et al. (2018) A mechanism for epigenetic control of DNA replication. Genes Dev 32 (3–4), 224–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goren A et al. (2008) DNA replication timing of the human beta-globin domain is controlled by histone modification at the origin. Genes Dev 22 (10), 1319–1324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aggarwal BD and Calvi BR (2004) Chromatin regulates origin activity in Drosophila follicle cells. Nature 430 (6997), 372–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vogelauer M et al. (2002) Histone Acetylation Regulates the Time of Replication Origin Firing. Mol Cell 10 (5), 1223–1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu J et al. (2012) Analysis of model replication origins in Drosophila reveals new aspects of the chromatin landscape and its relationship to origin activity and the prereplicative complex. Molecular biology of the cell 23 (1), 200–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kemp MG et al. (2005) The histone deacetylase inhibitor trichostatin A alters the pattern of DNA replication origin activity in human cells. Nucleic Acids Res 33 (1), 325–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Friedman KL et al. (1996) Multiple determinants controlling activation of yeast replication origins late in S phase. Genes Dev 10 (13), 1595–1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Belsky JA et al. (2015) Genome-wide chromatin footprinting reveals changes in replication origin architecture induced by pre-RC assembly. Genes Dev 29 (2), 212–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kurat CF et al. (2017) Chromatin Controls DNA Replication Origin Selection, Lagging-Strand Synthesis, and Replication Fork Rates. Mol Cell 65 (1), 117–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Devbhandari S et al. (2017) Chromatin Constrains the Initiation and Elongation of DNA Replication. Mol Cell 65 (1), 131–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Azmi IF et al. (2017) Nucleosomes influence multiple steps during replication initiation. eLife 6, e22512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shoaib M et al. (2018) Histone H4K20 methylation mediated chromatin compaction threshold ensures genome integrity by limiting DNA replication licensing. Nature Communications 9 (1), 3704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cayrou C et al. (2015) The chromatin environment shapes DNA replication origin organization and defines origin classes. Genome Res 25 (12), 1873–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eaton ML et al. (2010) Conserved nucleosome positioning defines replication origins. Genes Dev 24 (8), 748–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chakraborty A et al. (2011) “ORCanization” on heterochromatin: Linking DNA replication initiation to chromatin organization. Epigenetics 6 (6), 665–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pak DTS et al. (1997) Association of the Origin Recognition Complex with Heterochromatin and HP1 in Higher Eukaryotes. Cell 91 (3), 311–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bannister AJ et al. (2001) Selective recognition of methylated lysine 9 on histone H3 by the HP1 chromo domain. Nature 410 (6824), 120–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vermeulen M et al. (2010) Quantitative Interaction Proteomics and Genome-wide Profiling of Epigenetic Histone Marks and Their Readers. Cell 142 (6), 967–980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shen Z et al. (2010) A WD-repeat protein stabilizes ORC binding to chromatin. Mol Cell 40 (1), 99–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang Y et al. (2016) Temporal association of ORCA/LRWD1 to late-firing origins during G1 dictates heterochromatin replication and organization. Nucleic Acids Res 45 (5), 2490–2502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Giri S et al. (2015) The preRC protein ORCA organizes heterochromatin by assembling histone H3 lysine 9 methyltransferases on chromatin. eLife 4, e06496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bell SP et al. (1993) Yeast origin recognition complex functions in transcription silencing and DNA replication. Science 262 (5141), 1844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Foss M et al. (1993) Origin recognition complex (ORC) in transcriptional silencing and DNA replication in S. cerevisiae. Science 262 (5141), 1838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wyrick JJ et al. (2001) Genome-Wide Distribution of ORC and MCM Proteins in S. cerevisiae: High-Resolution Mapping of Replication Origins. Science 294 (5550), 2357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Müller P et al. (2010) The conserved bromo-adjacent homology domain of yeast Orc1 functions in the selection of DNA replication origins within chromatin. Genes Dev 24 (13), 1418–1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Palacios DeBeer MA et al. (2003) Differential DNA affinity specifies roles for the origin recognition complex in budding yeast heterochromatin. Genes Dev 17 (15), 1817–1822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hayashi MT et al. (2009) The heterochromatin protein Swi6/HP1 activates replication origins at the pericentromeric region and silent mating-type locus. Nat Cell Biol 11 (3), 357–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pappas DL et al. (2004) The NAD+-dependent Sir2p histone deacetylase is a negative regulator of chromosomal DNA replication. Genes Dev 18 (7), 769–781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Popova VV et al. (2018) Nonreplicative functions of the origin recognition complex. Nucleus 9 (1), 460–473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hoggard TA et al. (2018) Yeast heterochromatin regulators Sir2 and Sir3 act directly at euchromatic DNA replication origins. PLoS Genet 14 (5), e1007418–e1007418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cornacchia D et al. (2012) Mouse Rif1 is a key regulator of the replication-timing programme in mammalian cells. The EMBO journal 31 (18), 3678–3690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yamazaki S et al. (2012) Rif1 regulates the replication timing domains on the human genome. The EMBO journal 31 (18), 3667–3677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hiraga S-I et al. (2017) Human RIF1 and protein phosphatase 1 stimulate DNA replication origin licensing but suppress origin activation. EMBO reports 18 (3), 403–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Peace JM et al. (2014) Rif1 regulates initiation timing of late replication origins throughout the S. cerevisiae genome. PloS one 9 (5), e98501–e98501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Seller CA and O’Farrell PH (2018) Rif1 prolongs the embryonic S phase at the Drosophila mid-blastula transition. PLoS Biol 16 (5), e2005687–e2005687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Foti R et al. (2016) Nuclear Architecture Organized by Rif1 Underpins the Replication-Timing Program. Mol Cell 61 (2), 260–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hiraga S. i. et al. (2014) Rif1 controls DNA replication by directing Protein Phosphatase 1 to reverse Cdc7-mediated phosphorylation of the MCM complex. Genes Dev 28 (4), 372–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sreesankar E et al. (2015) Drosophila Rif1 is an essential gene and controls late developmental events by direct interaction with PP1–87B. Scientific Reports 5 (1), 10679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mattarocci S et al. (2014) Rif1 Controls DNA Replication Timing in Yeast through the PP1 Phosphatase Glc7. Cell Reports 7 (1), 62–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Alver RC et al. (2017) Reversal of DDK-Mediated MCM Phosphorylation by Rif1-PP1 Regulates Replication Initiation and Replisome Stability Independently of ATR/Chk1. Cell Reports 18 (10), 2508–2520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sukackaite R et al. (2017) Mouse Rif1 is a regulatory subunit of protein phosphatase 1 (PP1). Scientific Reports 7 (1), 2119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Davé A et al. (2014) Protein phosphatase 1 recruitment by Rif1 regulates DNA replication origin firing by counteracting DDK activity. Cell reports 7 (1), 53–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Munden A et al. (2018) Rif1 inhibits replication fork progression and controls DNA copy number in Drosophila. eLife 7, e39140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mukherjee C et al. (2019) RIF1 promotes replication fork protection and efficient restart to maintain genome stability. Nature Communications 10 (1), 3287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Garzón J et al. (2019) Human RIF1-Protein Phosphatase 1 Prevents Degradation and Breakage of Nascent DNA on Replication Stalling. Cell reports 27 (9), 2558–2566.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hiraga S. i. et al. (2018) Budding yeast Rif1 binds to replication origins and protects DNA at blocked replication forks. EMBO reports 19 (9), e46222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Shyian M et al. (2016) Budding Yeast Rif1 Controls Genome Integrity by Inhibiting rDNA Replication. PLoS Genet 12 (11), e1006414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lopez-Mosqueda J et al. (2010) Damage-induced phosphorylation of Sld3 is important to block late origin firing. Nature 467 (7314), 479–483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Costanzo V et al. (2003) An ATR- and Cdc7-Dependent DNA Damage Checkpoint that Inhibits Initiation of DNA Replication. Mol Cell 11 (1), 203–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zegerman P and Diffley JFX (2010) Checkpoint-dependent inhibition of DNA replication initiation by Sld3 and Dbf4 phosphorylation. Nature 467 (7314), 474–478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Guo C et al. (2015) Interaction of Chk1 with Treslin negatively regulates the initiation of chromosomal DNA replication. Mol Cell 57 (3), 492–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shechter D et al. (2004) ATR and ATM regulate the timing of DNA replication origin firing. Nat Cell Biol 6 (7), 648–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Moiseeva TN et al. (2019) An ATR and CHK1 kinase signaling mechanism that limits origin firing during unperturbed DNA replication. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 116 (27), 13374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sokka M et al. (2018) The ATR-Activation Domain of TopBP1 Is Required for the Suppression of Origin Firing during the S Phase. International journal of molecular sciences 19 (8), 2376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Syljuåsen RG et al. (2005) Inhibition of Human Chk1 Causes Increased Initiation of DNA Replication, Phosphorylation of ATR Targets, and DNA Breakage. Mol Cell Biol 25 (9), 3553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bellelli R et al. (2014) NCOA4 Transcriptional Coactivator Inhibits Activation of DNA Replication Origins. Mol Cell 55 (1), 123–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kitsberg D et al. (1993) Allele-specific replication timing of imprinted gene regions. Nature 364 (6436), 459–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ding Q et al. (2020) The Genetic Architecture of DNA Replication Timing in Human Pluripotent Stem Cells. bioRxiv, 2020.05.08.085324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Macheret M and Halazonetis TD (2018) Intragenic origins due to short G1 phases underlie oncogene-induced DNA replication stress. Nature 555 (7694), 112–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Nieduszynski CA et al. (2005) The requirement of yeast replication origins for pre-replication complex proteins is modulated by transcription. Nucleic Acids Res 33 (8), 2410–2420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Julienne H et al. (2013) Human genome replication proceeds through four chromatin states. PLoS Comput Biol 9 (10), e1003233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Vakoc CR et al. (2005) Histone H3 Lysine 9 Methylation and HP1gamma Are Associated with Transcription Elongation through Mammalian Chromatin. Mol Cell 19 (3), 381–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Rondinelli B et al. (2015) H3K4me3 demethylation by the histone demethylase KDM5C/JARID1C promotes DNA replication origin firing. Nucleic Acids Res 43 (5), 2560–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Pryde F et al. (2009) H3 k36 methylation helps determine the timing of cdc45 association with replication origins. PLoS One 4 (6), e5882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wu R et al. (2016) H3K9me3 demethylase Kdm4d facilitates the formation of pre-initiative complex and regulates DNA replication. Nucleic Acids Res 45 (1), 169–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Tardat M et al. (2010) The histone H4 Lys 20 methyltransferase PR-Set7 regulates replication origins in mammalian cells. Nat Cell Biol 12 (11), 1086–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Tardat M et al. (2007) PR-Set7-dependent lysine methylation ensures genome replication and stability through S phase. The Journal of cell biology 179 (7), 1413–1426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Long H et al. (2020) H2A.Z facilitates licensing and activation of early replication origins. Nature 577 (7791), 576–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kuo AJ et al. (2012) The BAH domain of ORC1 links H4K20me2 to DNA replication licensing and Meier–Gorlin syndrome. Nature 484, 115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Beck DB et al. (2012) The role of PR-Set7 in replication licensing depends on Suv4–20h. Genes Dev 26 (23), 2580–2589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Casas-Delucchi CS et al. (2012) Histone hypoacetylation is required to maintain late replication timing of constitutive heterochromatin. Nucleic Acids Res 40 (1), 159–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Black Joshua C. et al. (2013) KDM4A Lysine Demethylase Induces Site-Specific Copy Gain and Rereplication of Regions Amplified in Tumors. Cell 154 (3), 541–555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Mishra S et al. (2018) Cross-talk between Lysine-Modifying Enzymes Controls Site-Specific DNA Amplifications. Cell 174 (4), 803–817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Labbé RM et al. (2013) Histone lysine demethylase (KDM) subfamily 4: structures, functions and therapeutic potential. American journal of translational research 6 (1), 1–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Huang Y et al. (2006) Recognition of Histone H3 Lysine-4 Methylation by the Double Tudor Domain of JMJD2A. Science 312 (5774), 748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Iwase S et al. (2007) The X-Linked Mental Retardation Gene SMCX/JARID1C Defines a Family of Histone H3 Lysine 4 Demethylases. Cell 128 (6), 1077–1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lin C-H et al. (2008) Heterochromatin protein 1a stimulates histone H3 lysine 36 demethylation by the Drosophila KDM4A demethylase. Mol Cell 32 (5), 696–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Vacík T et al. (2018) KDM2A/B lysine demethylases and their alternative isoforms in development and disease. Nucleus 9 (1), 431–441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Koren A et al. (2014) Genetic variation in human DNA replication timing. Cell 159 (5), 1015–1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Mantiero D et al. (2011) Limiting replication initiation factors execute the temporal programme of origin firing in budding yeast. The EMBO journal 30 (23), 4805–4814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Collart C et al. (2013) Titration of four replication factors is essential for the Xenopus laevis midblastula transition. Science (New York, N.Y.) 341 (6148), 893–896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Massey DJ et al. (2019) Next-Generation Sequencing Enables Spatiotemporal Resolution of Human Centromere Replication Timing. Genes 10 (4), 269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.McIntosh D and Blow JJ (2012) Dormant origins, the licensing checkpoint, and the response to replicative stresses. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology 4 (10), a012955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Bechhoefer J and Rhind N (2012) Replication timing and its emergence from stochastic processes. Trends in genetics : TIG 28 (8), 374–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Alon U (2007) Network motifs: theory and experimental approaches. Nat Rev Genet 8 (6), 450–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Siefert JC et al. (2017) DNA replication timing during development anticipates transcriptional programs and parallels enhancer activation. Genome Res. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Hyrien O et al. (1995) Transition in Specification of Embryonic Metazoan DNA Replication Origins. Science 270 (5238), 994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Sasaki T et al. (1999) Specification of regions of DNA replication initiation during embryogenesis in the 65-kilobase DNApolalpha-dE2F locus of Drosophila melanogaster. Mol Cell Biol 19 (1), 547–555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Falbo L et al. (2020) SSRP1-mediated histone H1 eviction promotes replication origin assembly and accelerated development. Nat Commun 11 (1), 1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Klein KN et al. (2019) Replication timing maintains the global epigenetic state in human cells. bioRxiv, 2019.12.28.890020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Koren A and McCarroll SA (2014) Random replication of the inactive X chromosome. Genome Res 24 (1), 64–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Koren A (2014) DNA replication timing: Coordinating genome stability with genome regulation on the X chromosome and beyond. Bioessays 36 (10), 997–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Arias EE and Walter JC (2007) Strength in numbers: preventing rereplication via multiple mechanisms in eukaryotic cells. Genes Dev 21 (5), 497–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Brustel J et al. (2017) Histone H4K20 tri-methylation at late-firing origins ensures timely heterochromatin replication. EMBO J 36 (18), 2726–2741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Huang C et al. (2016) SUMOylated ORC2 Recruits a Histone Demethylase to Regulate Centromeric Histone Modification and Genomic Stability. Cell Rep 15 (1), 147–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]