Abstract

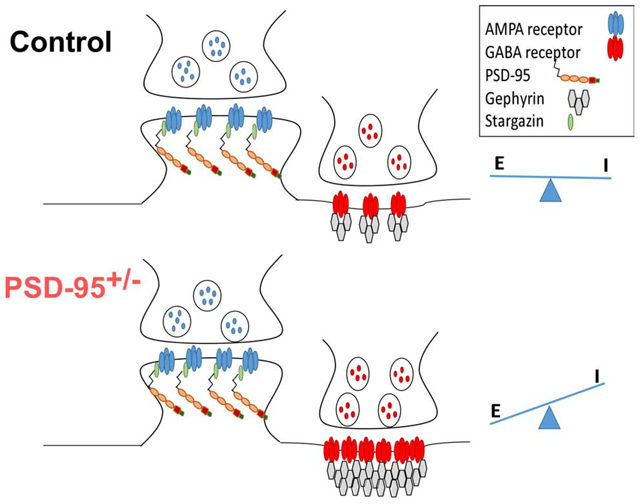

Postsynaptic Density Protein-95 (PSD-95) is a major scaffolding protein in the excitatory synapses in the brain and a critical regulator of synaptic maturation for NMDA and AMPA receptors. PSD-95 deficiency has been linked to cognitive and learning deficits implicated in neurodevelopmental disorders such as autism and schizophrenia. Previous studies have shown that PSD-95 deficiency causes a significant reduction in the excitatory response in the hippocampus. However, little is known about whether PSD-95 deficiency will affect gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA)ergic inhibitory synapses. Using a PSD-95 transgenic mouse model (PSD-95+/−), we studied how PSD-95 deficiency affects GABAA receptor expression and function in the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) during adolescence. Our results showed a significant increase in the GABAA receptor subunit α1. Correspondingly, there are increases in the frequency and amplitude in spontaneous inhibitory postsynaptic currents (sIPSCs) in pyramidal neurons in the mPFC of PSD-95+/− mice, along with a significant increase in evoked IPSCs, leading to a dramatic shift in the excitatory-to-inhibitory balance in PSD-95 deficient mice. Furthermore, PSD-95 deficiency promotes inhibitory synapse function via upregulation and trafficking of NLGN2 and reduced GSK3β activity through tyr-216 phosphorylation. Our study provides novel insights on the effects of GABAergic transmission in the mPFC due to PSD-95 deficiency and its potential link with cognitive and learning deficits associated with psychiatric disorders.

Keywords: PSD-95, inhibitory transmission, GABA receptors, schizophrenia, prefrontal cortex

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

PSD-95, a member of the membrane-associated guanylate kinase (MAGUK) family, is one of the most abundant proteins in the postsynaptic density (PSD) (Coley and Gao, 2018; El-Husseini et al., 2000; Keith and El-Husseini, 2008) and is a major scaffolding protein primarily localized to the PSD of excitatory glutamatergic synapses. PSD-95 is involved in the recruitment and trafficking of both N-methyl-D-aspartic acid receptors (NMDARs) and α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isox-azoleproprionic acid receptors (AMPARs) via direct interaction with stargazin to the postsynaptic membrane (Coley and Gao, 2018; El-Husseini et al., 2000; Keith and El-Husseini, 2008). The effects of PSD-95 deficiency on glutamatergic transmission have been well characterized in transgenic mouse lines within brain regions such as the hippocampus and amygdala (Coley and Gao, 2018; El-Husseini et al., 2000; Keith and El-Husseini, 2008), revealing reductions in AMPAR-mediated current, and increases in NMDAR localization and NMDAR-mediated current (Bustos et al., 2014; Keith and El-Husseini, 2008).

Recent evidence describes PSD-95’s involvement in neuropsychiatric disorders, such as schizophrenia (SCZ) (Bustos et al., 2014; Keith and El-Husseini, 2008). Exome sequencing studies of SCZ patients displayed missense mutations in the Dlg4 gene encoding PSD-95. Additionally, in patients with SCZ, there is a reported ~30% decrease in PSD-95 protein levels in the postmortem prefrontal cortex (PFC) (Catts et al., 2015). The PFC is responsible for coordinating complex cognitive behavior and decision-making processes, and is highly susceptible in SCZ patients (Dienel and Lewis, 2019; Miller and Cohen, 2001). Further studies are paramount to understand the effects of PSD-95 disruption and synaptic function in the PFC.

Previous studies indicated that PSD-95 deficiency enhanced long-term potentiation but had limited effects on NMDAR-mediated currents and subunit expression, as well as spine location and morphology in the CA1 pyramidal neurons (Migaud et al., 1998). However, we and others have found that the effects of PSD95 deficiency on synaptic function and social behavior are age and brain region-specific (Béïque et al., 2006; Coley and Gao, 2019; Feyder et al., 2010; Winkler et al., 2018; Yao et al., 2004). Importantly, most studies investigating PSD-95 deficiency showed alterations in excitatory transmission; the effects on inhibitory transmission are less understood. In fact, there was only one study showing that overexpression of PSD-95 in hippocampal neuronal cultures leads to a reduced number of GABAergic synapses on pyramidal cells, thus increasing the excitatory-to-inhibitory (E/I) synaptic ratio (Prange et al., 2004). Accordingly, knocking down PSD-95 leads to fewer excitatory glutamatergic synaptic contacts and an increased number of inhibitory GABAergic synaptic contacts, thereby decreasing the E/I synaptic ratio (Prange et al., 2004). These results illustrate that PSD-95 plays an important role not only in the function and/or maintenance of glutamatergic synapses but also in GABAergic synapses. However, it remains unknown how PSD-95 deficiency affects GABAergic inhibition in vivo. Using a PSD-95 deficient mouse model (PSD-95+/−), our study revealed that PSD-95 deficiency leads to an increase in GABAergic inhibition in the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), due to an increase in GABAR presence and function, thereby causing a shift in E/I balance towards inhibition. By utilizing whole-cell patch clamp recordings and protein expression analysis, we characterized specific GABAR-subunit expression levels and inhibitory function in response to PSD-95 deficiency. We also examined the direct and indirect molecules associated with GABARs and inhibitory transmission (Tyagarajan and Fritschy, 2014; Yu et al., 2007), that are altered due to PSD-95 deficiency.

Materials and Methods

Animals and Genotyping

PSD-95 heterozygous mice (PSD-95+/−) were acquired from Jackson Laboratory (B6.129-Dlg4tm1Rlh/J). Standard breeding procedures were used to generate PSD-95+/− mice, and their PSD-95+/+ littermates were used as controls. All mice were genotyped with a tail snip and PCR techniques using specific primers of the Dlg4 gene, which encodes PSD-95 (Supplementary Figure 1). All animals used in this project were of the adolescent age (postnatal day 35-40) (Kolb et al., 2012; Spear, 2000). Animals used in this study were housed in a temperature-controlled room on a 12 h light/dark cycle with food and water available ad libitum. All procedures were performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health (NIH) animal use guidelines and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Drexel University College of Medicine.

Tissue collection and western blot

Western Blot techniques were performed as previously described (Coley and Gao, 2019; Li et al., 2009; Snyder et al., 2013). Isolated mPFC brain region samples were homogenized using a mortar and pestle for 20 strokes in a sucrose buffer (in mM: 320 sucrose, 4-HEPES NaOH buffer, pH 7.4, 2 EGTA, 1 sodium orthovanadate, 0.1 phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 50 sodium fluoride, 10 sodium pyrophosphate, 20 glycerophosphate, with 1 μg/mL leupeptin and 1 μg/ml aprotinin). The homogenized sample was then centrifuged at 1,000 g for 10 min at 4°C to remove large cell fragments and nuclear materials. The resulting supernatant was centrifuged at 15,000 g for 15 min to yield cytoplasmic proteins in the supernatant. The supernatant was discarded and the pellet from this spin was hypo-osmotically lysed and re-suspended in homogenization buffer and incubated for 30 minutes at 4°C with continuous mixing. The mixture was then centrifuged at 25,000 g for 30 min to isolate synaptosomal protein fractions in the pellet.

A bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay was performed to determine protein concentration. The protein sample was mixed with laemmli sample buffer, boiled for 5 min, and separated on a 7.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide electrophoresis gel. Proteins were transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane (Millipore Billerica, MA). The membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat milk and probed with the following antibodies: PSD- 95 (Millipore, 1:2000, Cat# AB9708, RRID:AB_2092543), GABAaR α1 (Abcam, 1:10,000, Cat# ab33299, RRID:AB_732498), GABAaR α2 (Abcam, 1:10,000, Cat# ab72445, RRID:AB_1268929), Gephyrin (Abcam, 1:1,000), Neuroligin 2 (Synaptic Systems, 1:5,000, Cat# 129202, RRID:AB_003011), ErbB4 (Thermo Fischer Scientific, 1:500, Cat# MA1–861, RRID:AB_325379), SynGap1 (Thermo Fischer Scientific, 1:1,000, Cat# PA1–046, RRID:AB_2287112), GŜ (Cell Signaling, 1:1,000, Cat# 9315S, RRID:AB_490890), pGŜ Ser9 (Cell Signaling, 1:500, Cat# 9336S, RRID:AB_331405) and pGŜ Ty (Cell Signaling, 1:500, Cat# 3548, RRID:AB_1549581), with β-actin (Sigma, 1:5000, Sigma-Aldrich Cat# A5316, RRID: AB_476743) as the loading control. The blots were incubated with secondary antibody (Digital, anti-mouse-HRP, 1:1000 and Digital, anti-rabbit-HRP, 1:1000, Kindle Biosciences) and proteins were visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence (GE Healthcare).

Co-Immunoprecipitation

Samples for the Co-Immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) were prepared as described above in Western blot sample preparation. Protein samples were incubated with the antibody of the specific protein that was pulled down overnight. These samples were then incubated with 40 βL of Protein G Magbeads (Genscript, Cat# L00274). The sample tubes were placed in a magnetic rack (Genscript) to allow the beads to separate from the supernatant, which was then discarded. The bead samples were then mixed with the laemmli buffer mix and boiled for 5 min at 90°C. The supernatant was collected and used in the SDS-PAGE and Western blot as described above. The blots were probed using antibodies to Gephyrin (Abcam, 1:2,000, Cat# ab32206, RRID:AB_2112628), PSD-95 (Millipore, 1:5,000), Neuroligin 2 (Synaptic Systems, 1:10,000) and NR2A (Millipore, 1: 5,000, Cat# 04-901, RRID: AB_1163481) for a negative control. For both Western blotting and co-immunoprecipitation, the relative expression of proteins was evaluated by measuring the densitometry with the NIH Image J Pro software. The densitometry of total protein was normalized to actin, whereas phosphorylation of protein was normalized to its respective total protein level. All uncropped representative western blots and co-immunoprecipitation assays was displayed in Supplementary Figure 2. Results are presented as mean ± SEM and significance determined with Student’s t-test.

Whole-Cell Patch Clamp Electrophysiology

Mice were anesthetized with Euthasol-III solution (0.2 mL, i.p., Med-Pharmex, Inc, Pomona, CA) until unresponsive to a toe pinch. Animals were then quickly decapitated, and the prefrontal region of their brain was extracted and placed in an ice-cold sucrose solution (in mM: 87 NaCl, 75 sucrose, 2.5 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 7 MgCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 26 NaHCO3, and 25 dextrose) and bubbled with 95% O2/5% CO2. Coronal slices were made 300 μm thick using the Leica VT-1200 S Vibratome (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany). Once the slices were collected, they were incubated at 37°C in the sucrose solution and bubbled with 95% O2/5% CO2 for 30 minutes. They were then stored at room temperature until being transferred to the recording chamber.

PFC slices were bathed in a heated (35-37°C) recording chamber with oxygenated (95% O2/5% CO2) Ringer’s artificial cortico-spinal fluid (ACSF, in mM: 124 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 26 NaHCO3, and 10 dextrose, pH 7.4). Glass micropipettes were filled with a high chloride cesium-based intracellular solution (in mM: 110 D-gluconic acid, 134 CsCl, MgCl2, 0.2 EGTA, 5 QX-314, 2 Na2ATP, 0.5 Na2GTP, 10 HEPES, at pH 7.3, adjusted with CsOH, Osmolarity ~310 mOsm). Layer 5 pyramidal neurons in the prelimbic region of the mPFC were located with the assistance of infrared differential interference contrast (DIC) to visualize the soma shape using the Zeiss Microscope system. Spontaneous inhibitory postsynaptic currents (sIPSCs) were recorded in the presence of the AMPAR blocker DNQX (20μM), which was added to the bath solution. Neurons were held in voltage clamp at −70 mV for 5 minutes, and the frequency, amplitude, and decay time of resulting negative-going events were recorded. To isolate spontaneous excitatory postsynaptic currents (sEPSCs), the membrane potential was held at −70 mV with Cs+-containing intracellular solution in the presence of picrotoxin (PTX; 50 μM, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, Cat# 124-87-8). A typical sEPSC was selected to create a sample template for the event detections within a 5-min data period. The frequency (number of events) and amplitude of the individual events were examined with Clampfit. We then visually examined the detected events and inspected them to ensure specificity.

To measure the E/I balance, evoked IPSCs (eIPSCs) and excitatory postsynaptic currents (eEPSCs) were recorded in the same cell. Micropipettes were filled with a potassium-gluconate intracellular solution (in mM: 120 potassium gluconate, 20 KCl, 4 ATP-Na, 0.3 Na2GTP, 5 Naphosphocreatine, 0.1 EGTA, 10 HEPES, pH 7.3, 305 mosmol/l), as we reported recently (Ferguson and Gao, 2018). A stimulating electrode was placed in layer 2/3 about 200-300 μm from the recorded pyramidal neuron in layer 5 of the mPFC. A one-pulse stimulus was given (duration 0.5 ms), with the stimulus strength adjusted so the first eEPSC peak was approximately 50 pA. Cells were first clamped at −60 mV (the reversal potential of Cl− reported is −50.8 mV) to record excitatory currents and then at 0 mV (the reversal potential of EPSC, with 10 μM CPP to block NMDA) for inhibitory currents. The E/I balance ratio was calculated with mean peak eEPSC amplitude divided by the mean peak eIPSC amplitude. The liquid junction potential for these recordings were ~9 mV, but no correction was made for the data presented. The series resistance was monitored by using a hyperpolarization current injection pulse (−0.1 nA) at 150 ms during eEPSC and eIPSC recordings. The recordings were auto-compensated using the auto-compensation function of the MultiClamp 700B program. Additional details of electrophysiology analysis are described in the Supplemental Materials. All data are presented as mean ± standard error. Data between the two groups were analyzed with unpaired Student’s t-tests. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad 5.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA) and a p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

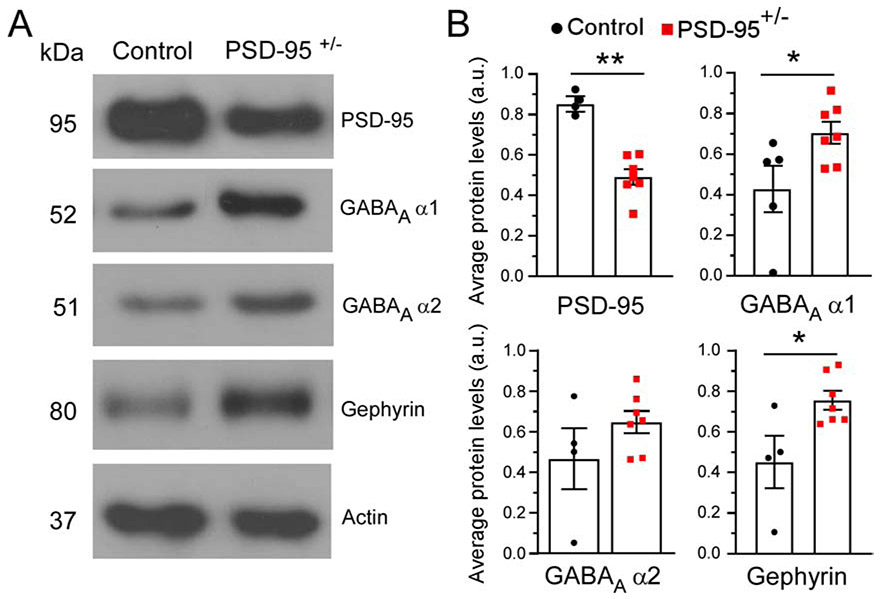

PSD-95+/’ mice exhibit increases in GABAAR subunits and Gephyrin

First, we confirmed the relative protein expression levels of PSD-95 in the mPFC in PSD-95+/− mice. PSD-95 expression was significantly reduced to ~50% in the mPFC of PSD-95+/− mice (p=0.003; CON, 0.85 ± 0.077, n=4; PSD-95+/−, 0.48 ± 0.046, n=6; Figure 1) compared to PSD-95+/+ control mice. Next, we examined whether PSD-95 deficiency alters GABAAR-subunits α1 and α2, widely considered as the most predominate α-subunits in the PFC (Akbarian, 1995; Huntsman et al., 1994). We found no changes in GABAAR α2 subunit between PSD-95+/− and control mice (p=0.204; CON, 0.47 ± 0.151, n=4; PSD-95+/−, 0.65 ± 0.055, n=7; Figure 1). However, we observed a significant increase in GABAAR α1 subunits in PSD-95+/− mice compared to control mice (p=0.038; CON, 0.433 ± 0.1157, n=5; PSD-95+/−, 0.71 ± 0.055, n=7; Figure 1). Additionally, we revealed that the inhibitory scaffolding protein gephyrin, prominently located at the postsynaptic density of inhibitory synapses, is significantly increased in PSD-95+/− mice (p=0.023; CON, 0.45 ± 0.129, n=4; PSD-95+/−, 0.76 ± 0.046, n=7; Figure 1). Together, this data suggest that the reduction in PSD-95 protein levels causes an increase in GABAAR α1 subunit and gephyrin protein expression levels in the mPFC, and thereby indicating an increase in inhibition.

Figure 1. PSD-95 deficiency increases GABAaR α1 subunit expression.

(A) Representative Western blots are shown for PSD-95, GABAA α1, GABAA α2 and Gephyrin at postnatal day 35 for control and PSD-95+/− mice; normalized to actin. (B) Quantitative analysis of protein levels for PSD-95 (p=0.003, CON, n=4, PSD-95+/−, n=6), GABAA α1 (p=0.038, CON, n=5, PSD-95+/−, n=7), GABAA α2 (p=0.204, CON, n=4, PSD-95+/−, n=7) and Gephyrin (p=0.023, CON, n=4, PSD-95+/−, n=7). *p<0.05, **p<0.01.

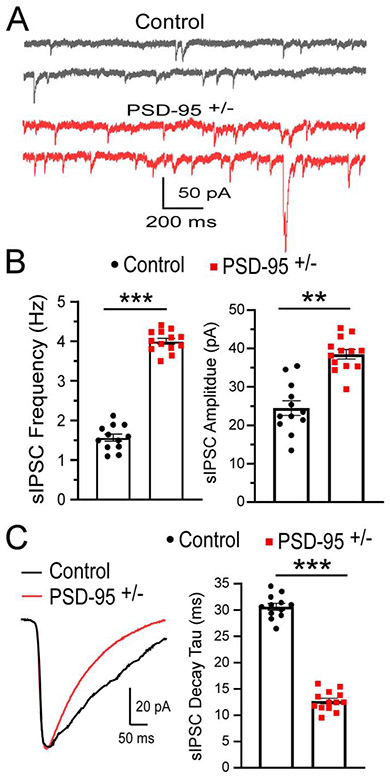

PSD-95 deficiency increases spontaneous inhibitory postsynaptic currents

To assess GABAAR function in PSD-95+/− mice, we utilized whole-cell patch-clamp recordings to measure GABAAR-mediated IPSCs from layer V pyramidal neurons in the mPFC. Our results showed significant increases in both the frequency (p=0.00002; CON, 1.49 ± 0.10 Hz, n=12; PSD-95+/−, 4.07 ± 0.29 Hz, n=13; Figure 2A, B) and amplitude (p=0.003; CON, 22.31 ± 3.374 pA, n=12; PSD-95+/−, 39.56 ± 4.01 pA, n=13; Figure 2A, B) of sIPSCs in PSD-95+/− mice compared to control mice. Interestingly, we observed a significant decrease in sIPSCs decay time in PSD-95+/− mice (p=0.000006; CON, 30.61 ± 2.15, n=12; PSD-95+/−, 12.20 ± 2.06, n=13; Figure 2C). Accordingly, a decrease in decay time indicates fast receptor kinetics, suggesting a high presence of GABAAR subunit α1 (Dixon et al., 2014), and thus is consistent with our western blot analysis. Therefore, our results showed enhanced GABAR function during adolescence in the mPFC in response to PSD-95 deficiency.

Figure 2. PSD-95 increases inhibitory response in mPFC.

(A) Representative traces of sIPSCs recorded at −70mV, in the presence of DNQX from control and PSD-95+/− mice at postnatal day 40. (B, C) Summary histograms of sIPSC frequency ± s.e.m (p=0.00002; CON, n=12; PSD-95+/−, n=13), peak amplitude ± s.e.m (p=0.0031; CON, n=12; PSD-95+/−, n=13) and decay ± s.e.m (p=0.000006; CON, n=12; PSD-95+/−, n=13). *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

Furthermore, we examined whether these changes persist into adulthood (>postnatal day 60). We found similar changes, showing PSD-95+/− mice display significant increase in sIPSC amplitude (p=0.020; CON, 25.87 ± 4.79 pA, n=10; PSD-95+/−, 36.93 ± 4.42 pA, n=14) and frequency (p=0.0004; CON, 1.64 ± 0.08 Hz, n=10; PSD-95+/−, 3.49 ± 0.19 Hz, n=14; Supplementary Figure 3). Therefore, we observed no significant differences in inhibitory current between adolescent and adult age groups in PSD-95 deficient mice. We also examined whether PSD-95 deficiency affects AMPAR spontaneous excitatory postsynaptic currents (sEPSCs) in the mPFC. Our results revealed no significant changes in the amplitude (p=0.337, CON, 16.94 ± 1.50 pA, n=12; PSD-95+/−, 15.21 ± 0.97 pA, n=13) or frequency (p=0.223, CON, 2.76 ± 0.38, n=12; PSD-95+/−, 2.21 ± 0.25, n=13) of sEPSCs in PSD-95+/− mice (Supplementary Figure 4). These results indicate PSD-95 deficiency displays no effects on AMPAR excitatory transmission in layer V pyramidal neurons.

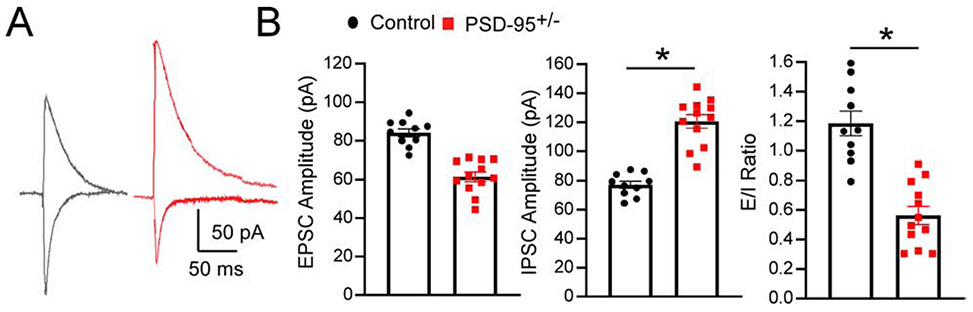

PSD-95 deficiency shifts E/I balance towards inhibition

To investigate the E/I balance in the mPFC in PSD-95 deficient mice, we recorded evoked EPSCs (eEPSCs) and evoked inhibitory postsynaptic currents (eIPSCs). In PSD-95+/− mice, we observed no significant changes in AMPAR-mediated EPSC amplitude (CON, n=10; PSD-95+/−, n=12; p> 0.05); however, we showed a significant increase in GABAR-mediated IPSC amplitude in PSD-95+/− mice compared to control mice (CON, n=10; PSD-95+/−, n=12; p=0.046), resulting in a significant shift of the E/I balance towards inhibition (CON, n=10; PSD-95+/−, n=12; p=0.001; Figure 3). Therefore, these results indicate a dramatic increase in GABAAR-mediated postsynaptic inhibitory response due to PSD-95 deficiency, further corroborating an enhancement of inhibitory transmission within the mPFC.

Figure 3. PSD-95 deficiency decreases E/I balance in mPFC.

(A) Representative traces of evoked EPSCs recorded at −60mV and IPSCs at 0mV in the presence of CPP from control and PSD-95 +/− mice at postnatal day 40. (B-D) Summary histograms of AMPAR-EPSC peak amplitude ± s.e.m ( p=0.103;CON, n=10; PSD-95+/−, n=12), GABAR-IPSC peak amplitude ± s.e.m (p=0.046; CON, n=10; PSD-95+/−, n=12) and EPSC/IPSC ratios measured ± s.e.m (p=0.001; CON, n=10; PSD-95+/−, n=12). *p<0.05, **p<0.01.

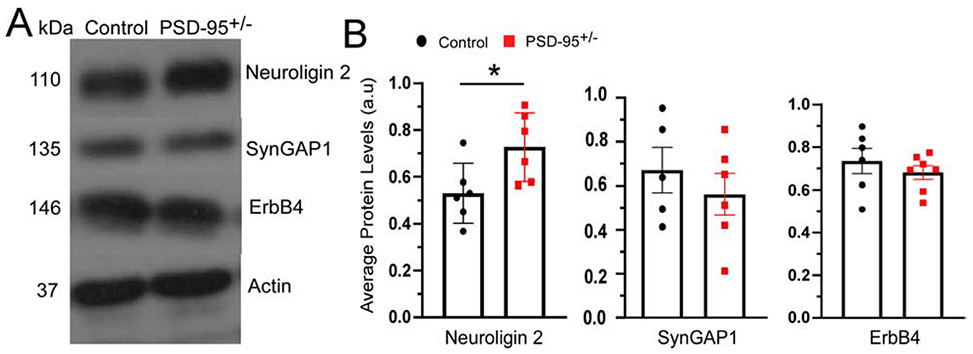

PSD-95 deficiency increases protein expression levels of Neuroligin 2 but not ErbB4 or SynGAP1.

A critical question remained; how does PSD-95 deficiency affect GABAARs that are located at inhibitory synapses? To answer this question, we examined protein expression levels of multiple inhibitory signaling molecules known to interact with PSD-95, such as NLGN2, SynGAP1, and ErbB4 (Coley and Gao, 2018). This exploratory method provided us an understanding of potential downstream molecules that may alter GABAergic inhibition in response to PSD-95 deficiency. Western blot analysis of synaptosomal fragments in the mPFC of PSD-95+/− mice revealed no changes in protein expression levels of SynGAP1 (p=0.337; CON 0.62 ± 0.07, n=5; PSD-95+/− 0.74 ± 0.09, n= 6; Figure 4) and ErbB4 compared to control mice (p=0.755; CON 0.75 ± 0.09, n=6; PSD-95+/− 0.788 ± 0.093, n=7; Figure 4). Interestingly, we found a significant increase in the inhibitory adhesion protein, NLGN2 in PSD-95+/− mice (p=0.033; CON, n=6, 0.53 ± 0.05; PSD-95+/−, n=6, 0.72 ± 0.06; Figure 4). This data suggest that PSD-95 deficiency causes an increase in inhibitory synaptic transmission due to the upregulation of NLGN2.

Figure 4. PSD-95 deficiency increases Neuroligin 2 expression in mPFC.

(A) Representative Western blots are shown for Neuroligin 2, SynGap 1 and ErbB4 at postnatal day 40 for control and PSD-95+/− mice; normalized to actin. (B) Quantitative analysis of protein levels for Neuroligin 2 ± s.e.m (p=0.033, CON, n=6, PSD-95+/−, n=6), SynGap 1± s.e.m (p=0.337, CON, n=5, PSD-95+/−, n= 6) and ErbB4 ± s.e.m (p=0.755, CON, n=6, PSD-95+/−, n=7). ). *p<0.05.

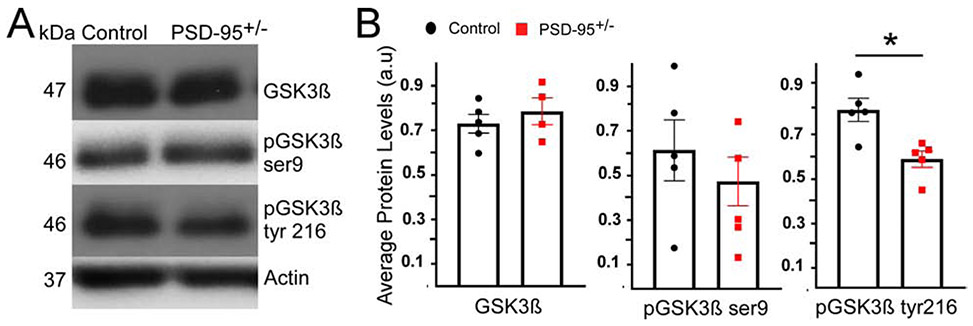

PSD-95 deficiency decreases GSK3β phosphorylation at tyrosine 216 residue

Next, we examined whether PSD-95 deficiency affects GSK3β, a prominent and highly abundant intracellular kinase involved in a variety of roles, including inhibitory transmission (Li et al., 2012). At inhibitory synapses, GSK3β attenuates gephyrin activity via phosphorylation (Tyagarajan et al., 2011), and thereby indirectly influences GABAR recruitment and stabilization at the postsynaptic membrane. As described above, PSD-95 deficiency causes an upregulation in gephyrin; therefore, we expected a decrease in GSK3β protein expression levels, thereby disinhibiting gephyrin recruitment of GABARs. Using western blot analysis, we showed no significant changes in total GSK3β protein levels in PSD-95+/− mice compared to control mice (p=0.688; CON 0.73 ± 0.04, n=5; PSD-95+/− 0.76 ± 0.08, n=4; Figure 5). However, since total GSK3β protein levels do not represent its activity, we explored specific residues of GSK3β, serine 9 and tyrosine 216, that upon phosphorylation are known to regulate GSK3β activity (Beurel et al., 2015; Krishnankutty et al., 2017; Tyagarajan et al., 2011). For instance, serine 9 phosphorylation of GSK3β reduces its activity; alternatively, tyrosine 216 phosphorylation causes an increase in GSK3β activity (Beurel et al., 2015; Tyagarajan et al., 2011). Our results showed no changes in GSK3β -serine 9 in PSD-95+/− mice (p=0.269; CON 0.62 ± 0.14, n=5; PSD-95+/− 0.41 ± 0.11, n=5; Figure 5). However, we found a significant decrease in GSK3β -tyrosine 216 expression in PSD-95+/− mice compared to control mice, indicating a reduction in GSK3β activity (p=0.029; CON 0.80 ± 0.05, n=5; PSD-95+/− 0.61 ± 0.05, n=5; Figure 5). This data identifies a potential target and intracellular mechanism describing GSK3βs influence on the inhibitory scaffolding protein gephyrin, and subsequent recruitment of GABARs in response to PSD-95 deficiency.

Figure 5. PSD-95 deficiency decreases GSK3β-tyr216 phosphorylation.

(A) Representative Western blots are shown for GSK3β, pGSK3β tyr 216 and pGSK3β ser9 at postnatal day 40 for control and PSD-95+/− mice; normalized to total GSK3β protein levels. (B) Quantitative analysis of protein levels for total GSK3β ± s.e.m (p=0.688, CON, n=5, PSD-95+/−, n=4), pGSK3β tyr 216 ± s.e.m (p=0.029, CON, n=5, PSD-95+/−, n=5) and pGSK3β ser9± s.e.m (p=0.267, CON, n=5, PSD-95+/−, n=5). *p<0.05.

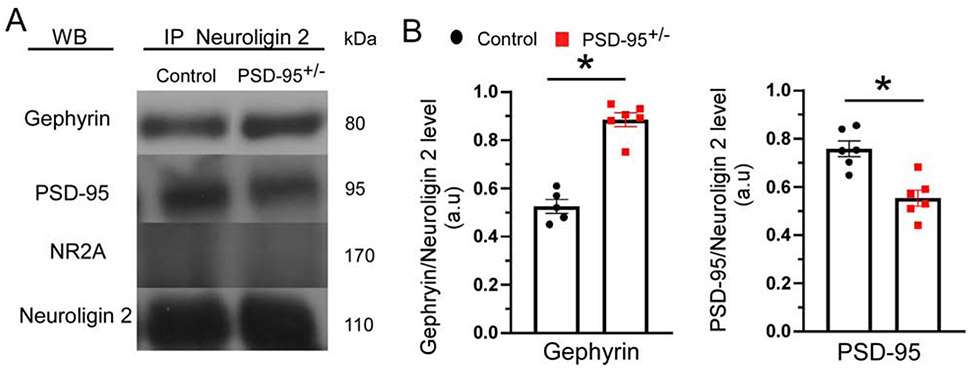

PSD-95 deficiency alters interactions between Neuroligin 2 and Gephyrin

We then assessed whether PSD-95 deficiency alters the interactions between PSD-95 and NLGN2, as well as Gephyrin and NLGN2. At inhibitory synapses, NLGN2/gephyrin interactions are critical for stabilization and localization of GABAARs to the postsynaptic membrane, while PSD-95/NLGN2 complexes facilitate interactions of NMDAR’s, K+ channels, and β-neurexins, at GABAergic synapses (Huang and Scheiffele, 2008; Irie et al., 1997; Tyagarajan and Fritschy, 2014). Utilizing co-immunoprecipitation assays, we showed a significant increase in the interaction of NLGN2 and gephyrin in PSD-95+/− mice compared to control mice (p=0.001; CON, 0.63 ± 0.04, n=5; PSD-95+/−, 0.86 ± 0.04, n=7; Figure 6). Furthermore, we revealed a significant decrease in the interaction of NLGN2 and PSD-95 in PSD-95+/− mice, indicating a reduction in PSD-95/NLGN2 complexes (p=0.016; CON, 0.81 ± 0.03, n=5; PSD-95+/−, 0.66 ± 0.05, n=7; Figure 6). This data suggest that PSD-95 deficiency causes an increase in NLG2/Gephyrin interaction that likely contribute to the increase in GABAARs presence and function.

Figure 6. PSD-95 deficiency increases the gephyrin/Neuroligin 2 association and decreases PSD-95/Neuroligin 2 association.

(A) Representative Western blots are shown for gephyrin, PSD-95, and NR2A at postnatal day 40 for control and PSD-95+/− mice; normalized to Neuroligin 2. (B) Quantitative analysis of protein levels (n=5-6, *p<0.05).

Discussion

PSD-95 is a highly abundant scaffolding protein responsible for synaptic maturation of excitatory synapses; however, the effects on inhibitory synaptic transmission remain unexplored. Our study is the first to examine the effects on inhibition in response to PSD-95 deficiency within the mPFC. We utilized a PSD-95+/− mouse, which exhibits ~50% PSD-95 protein levels, to model PSD-95 deficiency, and thereby represents similarities reported within SCZ patients, describing a ~30% reduction of PSD-95 protein levels (Catts et al., 2015). More importantly, we specifically examined the mPFC in PSD-95+/− mice during the adolescent age range (P35-40), as this region and age are highly susceptible to SCZ patients (Danielyan and Nasrallah, 2009; Ohnuma et al., 2000).

Our results showed that PSD-95 deficiency caused a significant increase in expression levels of GABAAR α1 subunits; however, no changes in α2 subunits. GABAARs, primarily composed of five subunits, two of which are from the alpha family (α1-5) (Charych et al., 2009), predominantly express α1 and α2 subunits in the PFC (Michels and Moss, 2007). Since our results displayed an increase in GABAAR α1 subunits in PSD-95+/− mice, and no change in α2 subunits, we suggest that there is an increase in the overall number of GABAARS located at the synapse; therefore, ruling out a shift in α1- α2 subunits. Furthermore, we observed a significant increase in the inhibitory scaffolding protein gephyrin in PSD-95+/− mice. This data suggest an increase in recruitment and stabilization of GABAARs. Our study showed a change in the molecular composition of GABAARs and gephyrin in response to PSD-95 deficiency, and thus provided a framework to investigate inhibitory transmission.

Previous studies examining PSD-95 deficiency revealed significant decreases in AMPAR/NMDAR-mediated current ratio within the juvenile mouse hippocampus and visual cortex (<P25) (Béïque et al., 2006; Yu et al., 2007). In another study, investigators utilized shRNAs to knockdown PSD-95 in cultured CA1 hippocampus pyramidal neurons and showed a significant decrease in both AMPA- and NMDA-EPSCs (Ehrlich et al., 2007). Although we noticed protein level changes in GABAAR α1 subunits, it was not indicative of functional differences in pyramidal neurons. We therefore, measured inhibitory postsynaptic currents in layer V pyramidal neurons and found an increase in GABAAR-mediated current. This change was likely attributable to the increase in GABAARs at the postsynaptic site, and more specifically, an increase in the α1-subunit. Therefore, the increase in α1-subunits could explain an increase in GABAAR transmission (Michels and Moss, 2007). Furthermore, our results are consistent with the findings from the previous report (Prange et al., 2004), as they showed a decrease in IPSC frequency due to PSD-95 overexpression. We also observed a decrease in decay time in sIPSCs in PSD-95 deficient mice, suggesting GABAARs are opening and closing at a faster rate, and this fast inhibitory transmission is mediated via α1-subunits (Labrakakis et al., 2014). Therefore, in response to PSD-95 deficiency, GABAAR function and kinetics have significantly increased due to GABAAR α1-subunits.

E/I balance deficits have been proposed as the etiology of cognitive symptoms and social deficits in psychiatric diseases, such as schizophrenia and autism (Antoine et al., 2019; Bicks et al., 2015; Ferguson and Gao, 2018; Selimbeyoglu et al., 2017; Yizhar et al., 2011). We observed a shift in E/I balance towards inhibition in layer V pyramidal neurons in the mPFC when PSD-95 is knocked down. More specifically, we revealed a significant increase in evoked IPSCs, indicating more inhibitory input to layer V pyramidal neurons. Instead, no change was observed in evoked EPSCs, suggesting that the major influence in E/I balance shift was attributable to the increase in inhibitory transmission. While other studies report changes in glutamatergic transmission when PSD-95 is knocked out or overexpressed (El-Husseini et al., 2000; Prange et al., 2004); our heterozygous model, containing ~50% PSD-95 reduction, showed no changes in spontaneous excitatory transmission during the adolescent period. This data suggest no significant changes in AMPAR-mediated EPSCs in response to knocking down PSD-95 in the mPFC. It is likely a ~50% reduction in PSD-95 protein levels does not significantly influence recruitment and stabilization of AMPARs. Indeed, other scaffold proteins such as SAP-97 (known to bind AMPARs) would act as a compensatory response in the absence of PSD-95, thereby providing sufficient excitatory transmission.

How does the increase in inhibition occur? NLGN2 is a cell adhesion molecule that is responsible for binding and maintaining the presynaptic terminal to the postsynaptic site at inhibitory synapses, and is thereby critical for efficient GABAergic transmission (Gibson et al., 2009; Huang and Scheiffele, 2008; Varoqueaux et al., 2004) and synapse development (Li et al., 2017). Furthermore, NLGN2 directly interacts with associated proteins linked to PSD-95 (Coley and Gao, 2018; Irie et al., 1997; Poulopoulos et al., 2009; Prange et al., 2004); therefore, it was likely that NLGN2 would be affected in response to PSD-95 deficiency. Indeed, measuring protein expression levels of NLGN2 within a PSD-95 deficient model, we revealed a significant upregulation in NLGN2 protein levels in PSD-95+/− mice. This is interesting since we observed an increase in GABAARs and gephyrin, which are known to bind to NLGN2 (Huang and Scheiffele, 2008; Panzanelli et al., 2017; Poulopoulos et al., 2009). Thus, NLGN2 may have been overcompensated for proper stabilization and localization of these inhibitory molecules in response to PSD-95 deficiency.

Furthermore, we found that total GSK3β protein levels within PSD-95+/− mice were unchanged compared to control mice. Upon initial discovery, this finding was not expected as phosphorylation by GSK3β on gephyrin decreases gephyrin stability in the postsynaptic site, which leads to reduced scaffolding of GABARs (Tyagarajan et al., 2011). However, GSK3β undergoes autophosphorylation to regulate enzymatic activity and can be phosphorylated primarily at two residues, serine 9 (Ser9) and tyrosine 216 (Tyr216) (Beurel et al., 2015). Ser9, when phosphorylated, causes a decrease in GSK3β activity (Beurel et al., 2015), whereas Tyr216 causes an increase in GSK3β activity upon phosphorylation (Krishnankutty et al., 2017). Our results showed a significant decrease in phosphorylated GSK3β at Tyr216 residue in PSD-95+/− mice, indicating an attenuation of GSK3β activity. Decreased activity of GSK3β will allow gephyrin to stabilize in the postsynaptic site which would subsequently lead to increased stabilization of GABAARs. Activation of GSK3β is dependent upon phosphorylation of Tyr216 (Krishnankutty et al., 2017); however, the mechanisms that regulate GSK3β at Tyr216 are not fully understood. Further experiments need to be conducted to elucidate how PSD-95 deficiency diminishes GSK3β activity via Tyr216 residue.

Since we observed several alterations in protein expression of inhibitory molecules in the PSD-95 deficient mouse, we wanted to examine direct interactions via co-immunoprecipitation assays. Therefore, we targeted NLGN2, as it binds directly with gephyrin and is critical for inhibitory transmission (Poulopoulos et al., 2009). Not surprisingly, we observed an increase in interaction between NLGN2 and gephyrin in PSD-95+/− mice. More interestingly, we noticed a decrease in interaction between PSD-95 and NLGN2 in PSD-95 deficient mice. NLGN2 is primarily localized to inhibitory synapses, while PSD-95 is predominantly located at excitatory synapses; however, NLGN2 can traffic between synapses (Hoon et al., 2009; Levinson et al., 2005; Prange et al., 2004). Therefore, we hypothesize that PSD-95 deficiency increases GABAergic transmission due to the upregulation and trafficking of NLGN2 from excitatory synapse to inhibitory synapses.

Altogether, these novel findings are a critical contribution to the field as we showed PSD- 95 deficiency leads to an increase in GABAergic inhibitory transmission likely due to the upregulation in Gephyrin and NLGN2 within the mPFC. This data could suggest that PSD-95 deficiency contributes to the pathophysiology in SCZ patients as it relates to PFC hypofrontality. However, a previous study utilized a similar PSD-95 heterozygous mouse model and revealed PSD-95+/− mice exhibit hypersocial behavior, contradicting SCZ and ASD phenotypes (Winkler et al., 2018). Indeed, assessing behavioral phenotypes in a heterozygous PSD-95+/− mouse model remains a caveat, as other regions involved in sociability such as the amygdala, hypothalamus, and nucleus accumbens (NAc) are likely differentially affected due to PSD-95 deficiency. Furthermore, since the PFC projects to multiple brain regions (Bolkan et al., 2017; Ferguson and Gao, 2018), a decreased output could disrupt many behavioral attributes. Therefore, future studies may consist of delineating the behavioral effects in conjunction with mPFC-associated neural circuits in response to PSD-95 deficiency.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

PSD-95+/− regulates GABAAR expression and function in the neocortex.

PSD-95+/− induces a significant increase in the GABAAR subunit α1.

PSD-95+/− induces increases in spontaneous IPSCs in prefrontal neurons.

PSD-95+/− induces a decrease in E/I balance in prefrontal neurons.

PSD-95+/− promotes an increase in inhibitory synaptic proteins NLGN2 and GSK3β.

Acknowledgments

This study is supported by the NIH/NINDS F99NS105185 to AAC and NIH/NIMH R01MH085666 to WJG.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interests

The authors report no competing interests or biomedical financial interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Akbarian S, 1995. GABAA receptor subunit gene expression in human prefrontal cortex: comparison of schizophrenics and controls. Cereb. Cortex 5, 550–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoine MW, Langberg T, Schnepel P, Feldman DE, 2019. Increased Excitation- Inhibition Ratio Stabilizes Synapse and Circuit Excitability in Four Autism Mouse Models. Neuron 101, 648–661.e644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Béïque J-C, Lin D-T, Kang M-G, Aizawa H, Takamiya K, Huganir RL, 2006. Synapse-specific regulation of AMPA receptor function by PSD-95. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 103, 19535–19540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beurel E, Grieco SF, Jope RS, 2015. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK3): regulation, actions, and diseases. Pharmacol Ther 148, 114–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bicks LK, Koike H, Akbarian S, Morishita H, 2015. Prefrontal cortex and social cognition in mouse and man. Frontiers in Psychology 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolkan SS, Stujenske JM, Parnaudeau S, Spellman TJ, Rauffenbart C, Abbas AI, Harris AZ, Gordon JA, Kellendonk C, 2017. Thalamic projections sustain prefrontal activity during working memory maintenance. Nat Neurosci 20, 987–996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bustos FJ, Varela-Nallar L, Campos M, Henriquez B, Phillips M, Opazo C, Aguayo LG, Montecino M, Constantine-Paton M, Inestrosa NC, van Zundert B, 2014. PSD95 Suppresses Dendritic Arbor Development in Mature Hippocampal Neurons by Occluding the Clustering of NR2B-NMDA Receptors. PLOS ONE 9, e94037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catts VS, Derminio DS, Hahn CG, Weickert CS, 2015. Postsynaptic density levels of the NMDA receptor NR1 subunit and PSD-95 protein in prefrontal cortex from people with schizophrenia. NPJ Schizophr 1, 15037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charych EI, Liu F, Moss SJ, Brandon NJ, 2009. GABA(A) receptors and their associated proteins: implications in the etiology and treatment of schizophrenia and related disorders. Neuropharmacology 57, 481–495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coley AA, Gao W-J, 2019. PSD-95 deficiency disrupts PFC-associated function and behavior during neurodevelopment. Scientific Reports 9, 9486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coley AA, Gao WJ, 2018. PSD95: A synaptic protein implicated in schizophrenia or autism? Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 82, 187–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danielyan A, Nasrallah HA, 2009. Neurological disorders in schizophrenia. Psychiatr Clin North Am 32, 719–757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dienel SJ, Lewis DA, 2019. Alterations in cortical interneurons and cognitive function in schizophrenia. Neurobiol Dis 131, 104208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon C, Sah P, Lynch JW, Keramidas A, 2014. GABAA receptor alpha and gamma subunits shape synaptic currents via different mechanisms. J Biol Chem 289, 5399–5411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich I, Klein M, Rumpel S, Malinow R, 2007. PSD-95 is required for activity-driven synapse stabilization. PNAS 104, 4176–4181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Husseini AE, Schnell E, Chetkovich DM, Nicoll RA, Bredt DS, 2000. PSD-95 involvement in maturation of excitatory synapses. Science 290, 1364–1368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson BR, Gao WJ, 2018. Thalamic Control of Cognition and Social Behavior Via Regulation of Gamma-Aminobutyric Acidergic Signaling and Excitation/Inhibition Balance in the Medial Prefrontal Cortex. Biol Psychiatry 83, 657–669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feyder M, Karlsson RM, Mathur P, Lyman M, Bock R, Momenan R, Munasinghe J, Scattoni ML, Ihne J, Camp M, Graybeal C, Strathdee D, Begg A, Alvarez VA, Kirsch P, Rietschel M, Cichon S, Walter H, Meyer-Lindenberg A, Grant SG, Holmes A, 2010. Association of mouse Dlg4 (PSD-95) gene deletion and human DLG4 gene variation with phenotypes relevant to autism spectrum disorders and Williams' syndrome. Am J Psychiatry 167, 1508–1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson JR, Huber KM, Sudhof TC, 2009. Neuroligin-2 deletion selectively decreases inhibitory synaptic transmission originating from fast-spiking but not from somatostatin-positive interneurons. J Neurosci 29, 13883–13897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoon M, Bauer G, Fritschy JM, Moser T, Falkenburger BH, Varoqueaux F, 2009. Neuroligin 2 controls the maturation of GABAergic synapses and information processing in the retina. J Neurosci 29, 8039–8050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang ZJ, Scheiffele P, 2008. GABA and neuroligin signaling: linking synaptic activity and adhesion in inhibitory synapse development. Curr Opin Neurobiol 18, 77–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huntsman MM, Isackson PJ, Jones EG, 1994. Lamina-specific expression and activity-dependent regulation of seven GABAA receptor subunit mRNAs in monkey visual cortex. J Neurosci 14, 2236–2259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irie M, Hata Y, Takeuchi M, Ichtchenko K, Toyoda A, Hirao K, Takai Y, Rosahl TW, Sudhof TC, 1997. Binding of neuroligins to PSD-95. Science 277, 1511–1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keith D, El-Husseini A, 2008. Excitation Control: Balancing PSD-95 Function at the Synapse. Front Mol Neurosci 1, 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolb B, Mychasiuk R, Muhammad A, Li Y, Frost DO, Gibb R, 2012. Experience and the developing prefrontal cortex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 109, 17186–17193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnankutty A, Kimura T, Saito T, Aoyagi K, Asada A, Takahashi S-I, Ando K, Ohara-Imaizumi M, Ishiguro K, Hisanaga S. i., 2017. In vivo regulation of glycogen synthase kinase 3β activity in neurons and brains. Scientific Reports 7, 8602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labrakakis C, Rudolph U, De Koninck Y, 2014. The heterogeneity in GABAA receptor-mediated IPSC kinetics reflects heterogeneity of subunit composition among inhibitory and excitatory interneurons in spinal lamina II. Frontiers in cellular neuroscience 8, 424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levinson JN, Chery N, Huang K, Wong TP, Gerrow K, Kang R, Prange O, Wang YT, El-Husseini A, 2005. Neuroligins mediate excitatory and inhibitory synapse formation: involvement of PSD-95 and neurexin-1beta in neuroligin-induced synaptic specificity. J Biol Chem 280, 17312–17319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Han W, Pelkey KA, Duan J, Mao X, Wang YX, Craig MT, Dong L, Petralia RS, McBain CJ, Lu W, 2017. Molecular Dissection of Neuroligin 2 and Slitrk3 Reveals an Essential Framework for GABAergic Synapse Development. Neuron 96, 808–826.e808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li YC, Wang MJ, Gao WJ, 2012. Hyperdopaminergic modulation of inhibitory transmission is dependent on GSK-3beta signaling-mediated trafficking of GABA(A) receptors. J Neurochem 122, 308–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li YC, Xi D, Roman J, Huang YQ, Gao WJ, 2009. Activation of glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta is required for hyperdopamine and D2 receptor-mediated inhibition of synaptic NMDA receptor function in the rat prefrontal cortex. J Neurosci 29, 15551–15563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michels G, Moss SJ, 2007. GABAA receptors: properties and trafficking. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol 42, 3–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Migaud M, Charlesworth P, Dempster M, Webster LC, Watabe AM, Makhinson M, He Y, Ramsay MF, Morris RG, Morrison JH, O’Dell TJ, Grant SG, 1998. Enhanced long-term potentiation and impaired learning in mice with mutant postsynaptic density-95 protein. Nature 396, 433–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller EK, Cohen JD, 2001. An integrative theory of prefrontal cortex function. Annu Rev Neurosci 24, 167–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohnuma T, Kato H, Arai H, Faull RL, McKenna PJ, Emson PC, 2000. Gene expression of PSD95 in prefrontal cortex and hippocampus in schizophrenia. Neuroreport 11, 3133–3137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panzanelli P, Fruh S, Fritschy JM, 2017. Differential role of GABAA receptors and neuroligin 2 for perisomatic GABAergic synapse formation in the hippocampus. Brain Struct Funct 222, 4149–4161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulopoulos A, Aramuni G, Meyer G, Soykan T, Hoon M, Papadopoulos T, Zhang M, Paarmann I, Fuchs C, Harvey K, Jedlicka P, Schwarzacher SW, Betz H, Harvey RJ, Brose N, Zhang W, Varoqueaux F, 2009. Neuroligin 2 drives postsynaptic assembly at perisomatic inhibitory synapses through gephyrin and collybistin. Neuron 63, 628–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prange O, Wong TP, Gerrow K, Wang YT, El-Husseini A, 2004. A balance between excitatory and inhibitory synapses is controlled by PSD-95 and neuroligin. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 101, 13915–13920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selimbeyoglu A, Kim CK, Inoue M, Lee SY, Hong ASO, Kauvar I, Ramakrishnan C, Fenno LE, Davidson TJ, Wright M, Deisseroth K, 2017. Modulation of prefrontal cortex excitation/inhibition balance rescues social behavior in CNTNAP2-deficient mice. Sci Transl Med 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder MA, Adelman AE, Gao W-J, 2013. Gestational methylazoxymethanol exposure leads to NMDAR dysfunction in hippocampus during early development and lasting deficits in learning. Neuropsychopharmacology 38, 328–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spear LP, 2000. The adolescent brain and age-related behavioral manifestations. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 24, 417–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyagarajan SK, Fritschy JM, 2014. Gephyrin: a master regulator of neuronal function? Nat Rev Neurosci 15, 141–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyagarajan SK, Ghosh H, Yévenes GE, Nikonenko I, Ebeling C, Schwerdel C, Sidler C, Zeilhofer HU, Gerrits B, Muller D, Fritschy JM, 2011. Regulation of GABAergic synapse formation and plasticity by GSK3β-dependent phosphorylation of gephyrin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108, 379–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varoqueaux F, Jamain S, Brose N, 2004. Neuroligin 2 is exclusively localized to inhibitory synapses. Eur J Cell Biol 83, 449–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler D, Daher F, Wustefeld L, Hammerschmidt K, Poggi G, Seelbach A, Krueger-Burg D, Vafadari B, Ronnenberg A, Liu Y, Kaczmarek L, Schluter OM, Ehrenreich H, Dere E, 2018. Hypersocial behavior and biological redundancy in mice with reduced expression of PSD95 or PSD93. Behav Brain Res 352, 35–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao WD, Gainetdinov RR, Arbuckle MI, Sotnikova TD, Cyr M, Beaulieu JM, Torres GE, Grant SG, Caron MG, 2004. Identification of PSD-95 as a regulator of dopamine-mediated synaptic and behavioral plasticity. Neuron 41, 625–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yizhar O, Fenno LE, Prigge M, Schneider F, Davidson TJ, O'Shea DJ, Sohal VS, Goshen I, Finkelstein J, Paz JT, Stehfest K, Fudim R, Ramakrishnan C, Huguenard JR, Hegemann P, Deisseroth K, 2011. Neocortical excitation/inhibition balance in information processing and social dysfunction. Nature 477, 171–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu W, Jiang M, Miralles CP, Li R, Chen G, De Bias AL, 2007. Gephyrin clustering is required for the stability of GABAergic synapses. Mol Cell Neurosci 36, 484–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.