SUMMARY

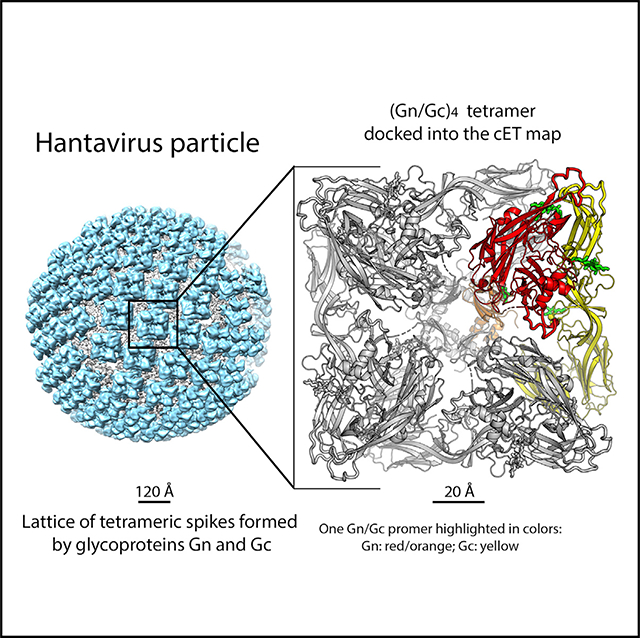

Hantaviruses are rodent-borne viruses causing serious zoonotic outbreaks worldwide for which no treatment is available. Hantavirus particles are pleomorphic and display a characteristic square surface lattice. The envelope glycoproteins Gn and Gc form heterodimers that further assemble into tetrameric spikes, the lattice building blocks. The glycoproteins, which are the sole targets of neutralizing antibodies, drive virus entry via receptor-mediated endocytosis and endosomal membrane fusion. Here we describe the high-resolution X-ray structures of the heterodimer of Gc and the Gn head and of the homotetrameric Gn base. Docking them into an 11.4-Å-resolution cryoelectron tomography map of the hantavirus surface accounted for the complete extramembrane portion of the viral glycoprotein shell and allowed a detailed description of the surface organization of these pleomorphic virions. Our results, which further revealed a built-in mechanism controlling Gc membrane insertion for fusion, pave the way for immunogen design to protect against pathogenic hantaviruses.

In Brief

X-ray structures of the hantavirus surface glycoprotein lattice reveal a built-in mechanism controlling envelope glycoprotein membrane insertion and provide important information for development of immunogen protection against these deadly viruses.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Rodent-borne hantaviruses form a close group of viruses distributed worldwide, classified as Old World hantaviruses and New World hantaviruses (OWHs and NWHs, respectively) based on their geographical distribution and natural reservoirs (Jonsson et al., 2010). They cause life-threatening zoonotic outbreaks of severe pulmonary disease (NWHs) and hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome (OWHs). Despite the severity of these diseases, no efficient treatment is available. Inhalation of aerosols contaminated with infected rodent excreta is the major route of transmission, although person-to-person transmission of a pulmonary syndrome caused by Andes hantavirus (ANDV) has also been reported (Martinez et al., 2005; Padula et al., 1998; Pizarro et al., 2020). NWHs therefore have the potential to adapt to human-to-human airborne transmission routes, increasing their epidemic potential.

The Hantaviridae constitute one of 12 families of segmented negative-strand RNA viruses in the recently established Bunyavirales order (Maes et al., 2019). As in most other members of this order (generically termed bunyaviruses), the viral genome is composed of three negative-polarity, single-stranded RNA segments: small, medium, and large. The medium (M) segment encodes a polyprotein precursor that is matured in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) by signalase cleavage to generate two envelope glycoproteins, Gn and Gc (Figure 1A; Löber et al., 2001). Gn interacts co-translationally with the membrane fusion protein Gc, maintaining it in a metastable pre-fusion conformation within a Gn/Gc heterodimer. The protomers further associate into (Gn/Gc)4 tetrameric spikes that are transported to the site of particle morphogenesis, the Golgi apparatus or the plasma membrane, depending on the virus (Cifuentes-Muñoz et al., 2014). The lateral interactions between adjacent spikes are believed to induce the membrane curvature required for budding of nascent virions (Huiskonen et al., 2010). Hantavirus particles are internalized into target cells via receptor-mediated endocytosis, with the glycoprotein shell reacting to the acidic endosomal pH to drive fusion of viral and cellular membranes through a conformational change of Gc (Acuña et al., 2015; Chiang et al., 2016; Cifuentes-Muñoz et al., 2011; Jin et al., 2002; Mittler et al., 2019; Ramanathan and Jonsson, 2008; Rissanen et al., 2017).

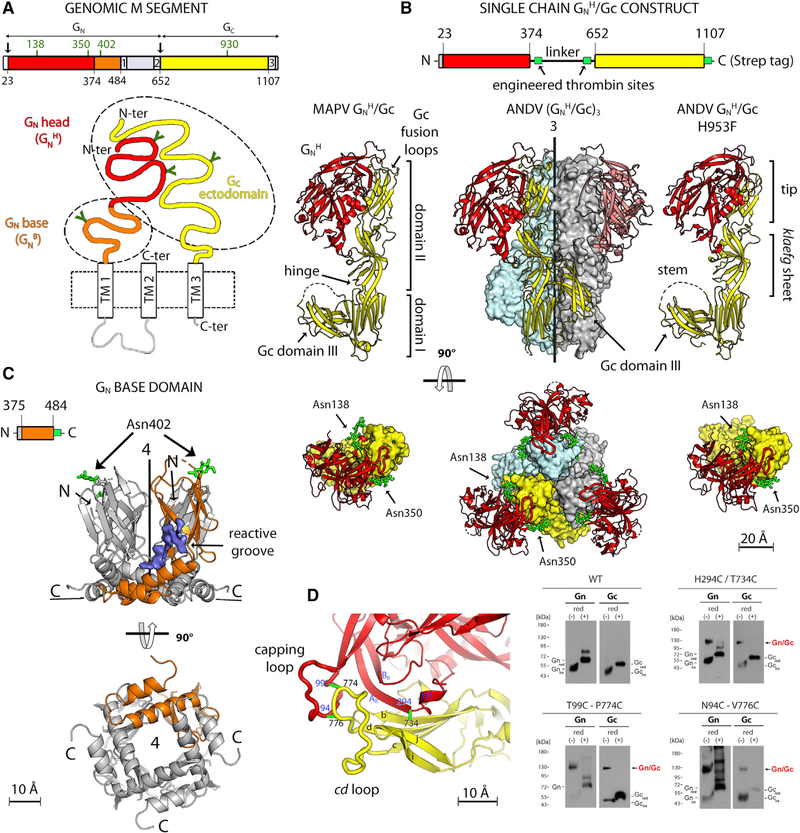

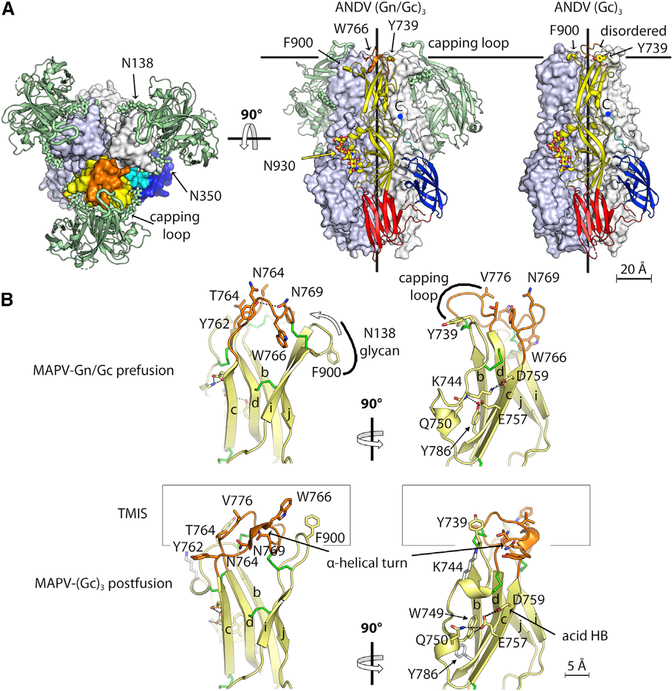

Figure 1. X-Ray Structures of the Hantavirus Glycoproteins.

(A) Domain organization of the hantavirus M segment. The top panel shows a linear diagram colored according to protein domains, with the signalase cleavage site (Gc N terminus) marked by an arrow. Glycosylated asparagines are labeled in green above the open reading frame (ORF). The bottom panel shows a schematic of the Gn/Gc heterodimer, with the viral membrane as a dashed box and TM segments indicated. The ectodomains of Gn and Gc are colored, with N-linked glycans indicated by “Y” symbols. Dashed ovals outline the two separate fragments whose structures were determined here.

(B) Structures of the hantavirus GnH/Gc heterodimer. First row: diagram of the single-chain GnH/Gc construct used for crystallization upon thrombin treatment (engineered thrombin sites are shown in green). The second and third rows show two orthogonal views of MAPV GnH/Gc (left), ANDV (GnH/Gc)3; center), and the ANDV GnH/Gc-H953F mutant (right). In the center panel, the (GnH/Gc)3 trimer is shown with Gc in yellow, gray, and light cyan surfaces and Gn as red ribbons. In the side view (second row), the front Gn chain was omitted for clarity, and the matching Gc chain is shown as yellow ribbons as in the left and right panels. All three panels in this row display Gc domain I in the same orientation. The top view (third row) also shows the glycan chains as green sticks and labeled.

(C) Structure of the ANDV GnB tetramer in side view (top) and bottom view (bottom panel), with one GnB chain highlighted in orange. The glycan attached to N402 in GnB is indicated as green sticks. The density corresponding to an omit map contoured at 1.5 σ is shown in blue, marking a reacting groove that binds a ligand from the supernatant (STAR Methods). We postulate that, in the spike, the Gc stem may run within this groove.

(D) Engineering of inter-chain disulfide bonds. Left panel: close up of the GnH/Gc interface marking the location of pairs of residues mutated to cysteine (connected by green bars and labeled).The right panel shows an SDS-PAGE analysis of VLPs released into the supernatant of cells expressing wild-type ANDV Gn/Gc and the indicated Cys double mutants under reducing and non-reducing conditions (as indicated).

The X-ray structures of the isolated Gn “head” (GnH; comprising the N-terminal two-thirds of the ectodomain; Li et al., 2016; Rissanen et al., 2017) and of the Gc ectodomain (Guardado-Calvo et al., 2016; Willensky et al., 2016) of the Puumala hantavirus (PUUV) and Hantaan hantavirus (HNTV) (both OWHs) have been reported. Gc has been shown to feature the three characteristic β sheet-rich domains (I, II, and III) observed in the class II fusion proteins of flaviviruses (Rey et al., 1995), alphaviruses (Lescar et al., 2001), phleboviruses (Dessau and Modis, 2013), and rubella virus (DuBois et al., 2013). The available structural snapshots of Gc show a monomer in an extended conformation stabilized by an antibody bound to domain II and a Gc trimer in the characteristic post-fusion “hairpin” conformation observed in other viral class II fusion proteins (Bressanelli et al., 2004; Gibbons et al., 2004; Luca et al., 2013; Modis et al., 2004).

The hantavirus square surface lattice was initially observed by negative-stain electron microscopy (Martin et al., 1985) and later characterized by cryoelectron tomography (cET) studies on particles of the OWH Tula virus (Huiskonen et al., 2010) and by single-particle averaging of the spikes on HTNV virions (Battisti et al., 2011). The cET studies showed pleomorphic particles with locally ordered lattices of tetrameric (Gn/Gc)4 spikes coating the viral membrane. A model for the organization of Gn and Gc in the lattice was proposed (Hepojoki et al., 2010), in which Gn was located at the spike center and Gc at the periphery, making intra- and inter-spike contacts, respectively. This model was in line with structural studies combining cET, subtomogram averaging (STA), and the X-ray structure of the isolated PUUV GnH (Li et al., 2016). It was further supported by functional studies confirming that the crystallographic 2-fold contacts made by HTNV Gc monomers (Guardado-Calvo et al., 2016) recapitulate the lateral interactions between spikes on particles (Bignon et al., 2019). Despite these advances, the actual organization of the spike and the molecular interactions between Gn and Gc have remained elusive.

Here we report the X-ray structure of the metastable prefusion GnH/Gc heterodimers of ANDV and Maporal virus (MAPV; an NWH closely related to ANDV) to 3.2- and 2.2-Å resolution, respectively. The ANDV complex required a stabilizing mutation in Gc to avoid a spontaneous conformational change into its post-fusion conformation despite bound GnH. We also describe the X-ray structure of the Gn base (GnB; the C-terminal third of the ectodomain) to 1.9-Å resolution, showing that it forms a tight tetramer. These structures unambiguously fit a cET map of the Tula virus Gn/Gc spike refined by STA to 11.4-Å resolution, confirming that the GnH/Gc and GnB conformations captured in the crystals indeed correspond to their active form in the spikes of infectious hantavirus particles and providing a complete model of the surface glycoprotein lattice. Functional studies by targeted mutagenesis further confirmed the detailed picture of the tetrameric spike organization as well as the lateral interactions between spikes. The GnH/Gc structure also revealed that, unlike other class II fusion proteins, GnH release at acid pH induces a further conformational change of the Gc domain II tip to expose non-polar side chains for insertion into the endosomal membrane.

RESULTS

Structural Characterization of the Hantavirus Glycoproteins

We produced the soluble ectodomains of the hantavirus GnH/Gc heterodimer using a single-chain construct in which a soluble linker bypassed the Gn transmembrane (TM) and intraviral/cytosolic segments to connect directly to the Gc N terminus (Figures 1A and 1B). Of the various hantavirus orthologs we tested, only constructs from the related NWHs ANDV and MAPV (accession numbers NP_604472.1 and YP_009362281, respectively) yielded enough protein for structural studies (an amino acid sequence alignment of Gn and Gc from selected hantaviruses is provided in Figure S1). We obtained monoclinic crystals for MAPV GnH/Gc diffracting to 2.2-Å resolution and rhombohedral crystals for ANDV GnH/Gc diffracting to 2.6 Å (Table 1) and determined the structures by molecular replacement. Both displayed GnH attached to the tip of Gc (Figure 1B) but showed two strikingly different overall conformations, with Gc in the ANDV GnH/Gc structure forming the characteristic post-fusion trimer despite having GnH bound. Using the same approach, we produced, in parallel, the C-terminal region of the Gn ectodomain (GnB, aa 375–484) from ANDV. GnB crystallized in an orthorhombic and a tetragonal space group at acidic and neutral pH, respectively. The structure was determined by single-wavelength anomalous dispersion (SAD) and refined to 1.9-Å resolution (Table 1). Both crystals showed an identical intertwined GnB tetramer containing an N-terminal β sandwich (aa 379–446) featuring an immunoglobulin superfamily (IgS) fold, followed by a C-terminal α-helical hairpin (Figure 1C).

Table 1.

Crystallographic Statistics

| ANDV-GnHGc (pH 8.5) | ANDV-GnHGc (H953F) (pH 8.5) | MAPV-GnHGc (pH 8.5) | ANDV-Gc (pH 7.5) | MAPV-Gc (pH 4.6) | HNTV-GnH (pH 7.5) | GnB (pH 4.6) | GnB (pH 7.5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data Collection | ||||||||

| Space group | H 3 | P 63 2 2 | C 1 2 1 | H 32 | H 32 | P21 21 21 | C 2 2 21 | I 4 |

| a (Å) | 130.3 | 188.5 | 120.3 | 92.6 | 90.4 | 53.6 | 90.6 | 67.8 |

| b (Å) | 130.3 | 188.5 | 65.1 | 92.6 | 90.4 | 92.2 | 123.1 | 67.8 |

| c (Å) | 129.5 | 117.3 | 144.9 | 318.5 | 506.4 | 94.0 | 90.1 | 121.9 |

| β (°) | 90 | 90 | 99.7 | 90 | 90 | 90 | 90 | 90 |

| Resolution (Å) | 37.62–2.55 | 49.36–3.20 | 38.07–2.20 | 39.80–2.70 | 39.83–2.40 | 35.34–1.94 | 45.3–1.90 | 37.7–2.35 |

| Last resolution bin (Å) | 2.66–2.55 | 3.42–3.20 | 2.26–2.20 | 2.83–2.70 | 2.49–2.40 | 1.98–1.94 | 1.94–1.90 | 2.43–2.35 |

| Total observations1 | 68,478 (8,692) | 335,389 (59,067) | 258,945 (13,723) | 139,957 (18,675) | 482,431 (52,803) | 289,204 (18,180) | 542,782 (31,473) | 114,803 (10,501) |

| Unique reflections | 25,995 (3,241) | 20,744 (3,657) | 55,909 (4,505) | 14,898 (1,949) | 31,958 (3,310) | 35,256 (2,248) | 39,873 (2,451) | 11,445 (1,080) |

| Completeness (%) | 97.3 (99.8) | 99.8 (99.4) | 99.5 (98.9) | 99.8 (99.9) | 100 (100) | 99.6 (95.6) | 99.8 (97.0) | 99.6 (96.4) |

| Redundancy | 2.6 (2.7) | 16.2 (16.2) | 4.6 (3.0) | 9.4 (9.6) | 15.1 (16.0) | 8.2 (8.1) | 13.6 (12.8) | 10.0 (9.7) |

| < I/σ > | 11.2 (1.4) | 13.5 (1.2) | 11.0 (0.9) | 8.2 (1.2) | 11.1 (1.0) | 14.6 (1.8) | 11.1 (0.9) | 8.1 (1.7) |

| Rsym (%)2 | 5.7 (73.5) | 19.2 (269.5) | 8.2 (114.1) | 13.6 (120) | 16.9 (262) | 7.6 (105) | 11.2 (288) | 18.4 (121) |

| CC1/2 | 99.7 (49.0) | 99.9 (53.2) | 99.7 (33.8) | 99.7 (91.8) | 99.8 (50.6) | 99.9 (65.5) | 99.8 (53.7) | 98.8 (45.5) |

| Refinement | ||||||||

| PDB accession code | 6Y5W | 6Y5F | 6Y62 | 6Y6Q | 6Y68 | 6Y6P | 6YRQ | 6YRB |

| Resolution (Å) | 37.62–2.55 | 49.63–3.20 | 35.14–2.20 | 39.80–2.70 | 39.83–2.40 | 35.35–1.94 | 45.3–1.90 | 37.7–2.35 |

| Last resolution bin (Å) | 2.64–2.55 | 3.36–3.20 | 2.24–2.20 | 2.79–2.70 | 2.44–2.40 | 1.99–1.94 | 1.94–1.90 | 2.58–2.35 |

| No. of reflections | 25,987 (2,465) | 20,680 (2,685) | 55,841 (2,606) | 14,734 (2,625) | 31,948 (2,798) | 35,189 (2,661) | 39,739 (2,560) | 11,444 (2,691) |

| No. of reflections for Rfree | 1,360 (165) | 1,032 (157) | 2,814 (132) | 1,338 (122) | 2,914 (128) | 1,673 (153) | 1,957 (123) | 570 (126) |

| R factor (%)3 | 21.8 (33.0) | 21.4 (34.2) | 19.4 (31.4) | 23.4 (37.7) | 19.6 (32.2) | 16.7 (23.0) | 18.7 (38.2) | 22.6 (29.8) |

| Rfree (%) | 26.1 (35.7) | 26.6 (44.9) | 22.6 (35.8) | 28.7 (34.2) | 23.6 (33.6) | 21.0 (25.2) | 23.0 (42.2) | 26.5 (34.2) |

| No. of protein and sugar atoms (chain A/B/C/D) | 2,776/3144 | 2,809 / 3,201 | 2,801/3,208 | 3,084 | 3,204 | 2,745 | 767/744/772/806 | 803/744 |

| No. of waters/Cd+2/I− | 64 | 1 | 261 | 4 | 83/4 | 202 | 137 | 55/0/6 |

| No. of (PO4)−2/(SO4)−2 atoms | 10/0 | 0/10 | ||||||

| No. of RNA/MPD atoms | 256/32 | 130 | ||||||

| Mean B Value (Å2) | ||||||||

| Protein and sugar (A/B/C/D) | 85.6/57.1 | 104.8/104.0 | 52.3/63.9 | 98.0 | 70.2 | 46.5 | 52/54/53/55 | 46/48 |

| Waters/ Cd+2/I− | 50.0 | 78.6 | 49.4 | 66 | 57.0/125 | 47.6 | 52 | 43/ND/115 |

| (PO4)−2/(SO4)−2 atoms | 161 | 0/152 | ||||||

| RNA/MPD | 53/67 | 52 | ||||||

| RMSDs | ||||||||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.002 | 0.007 | 0.006 | 0.003 | 0.008 | 0.018 | 0.006 | 0.002 |

| Bond angles (°) | 0.56 | 1.111 | 0.707 | 0.600 | 0.935 | 1.419 | 0.923 | 0.546 |

| Ramachandran favored/outliers (%) | 93.6/0.0 | 91.7/0.5 | 95.0/0.0 | 94.3/0.26 | 95.4/0.5 | 94.7/0.3 | 97.1/0.0 | 97.38/0.0 |

Data for the last resolution shell are in parenthesis

Rsym = Σ|Ii - <Ii>|/ Σ Ii, where Ii is the observed intensity and <Ii> is the average intensity obtained from multiple observations of symmetry-related reflections.

Rwork = Σ||Fobs(hkl)|-|Fcalc(hkl)||/ Σ|Fobs(hkl)|

The GnH/Gc Heterodimer Features Gc in the Pre-fusion Conformation

Examination of the previously reported cET-STA map of the Tula hantavirus Gn/Gc in situ tetramer at 16-Å resolution (EMDB: EMD-3364; Li et al., 2016), indicated that the X-ray structure of the GnH/Gc heterodimer could not be docked satisfactorily, whereas a good fit was obtained using the mirror image of this map. Although the hand of tomographic reconstructions is uniquely defined (unlike the reconstructions obtained by single-particle cryo-EM), any incompatibility in the convention for the sign of the rotation angles in the various software used for data collection and processing, or the exchange of X and Y axes of the detector, can result in the mirror image of the actual structure. We therefore experimentally established the correct handedness by including human papillomavirus capsids, which have a chiral structure of known handedness, in the sample as reference (STAR Methods; Figures S2A–S2D), demonstrating that the hand of the previously reported map was indeed inverted. We also increased the resolution of the map by using a larger dataset of imaged particles combined with strategies for removing noise and accounting for conformational flexibility of the spike itself. In addition, because purified hantavirus particles display a broken surface lattice, we restricted the dataset to include only regular patches on the virion surface for 3D classification. This strategy allowed us to use it for averaging a subvolume of the lattice containing a central spike and the contacts with its four immediate neighbors. At 11.4-Å resolution, the resulting cET map of the Tula virus particle is representative of the hantavirus pre-fusion spike because of the high sequence identity (Figure S1) of the glycoproteins across hantaviruses (e.g., Tula virus Gn and Gc display 63% and 73% amino acid sequence identity with their ANDV counterparts, respectively). Docking the 2.2-Å-resolution MAPV GnH/Gc structure (Figure 1B, left panel) into the cET map as a rigid body (Figure S3A; Table 2) resulted in a satisfying overall fit, although domain III was partially out of cET density. The 2.6-Å-resolution structure of ANDV GnH/Gc (Figure S3B) did not fit the cET map, as expected, because it has Gc in the post-fusion conformation.

Table 2.

EM Fitting Statistics

| Unconstrained Fittinga | Constrained Fittingb | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC | % Atoms Inside | CC | % Atoms Inside | |

| ANDV GnH/Gc (H953F) | ||||

| Central | 0.888 | 88.9 | 0.861 | 82.8 |

| Neighbor | 0.880 | 80.0 | 0.834 | 69.9 |

| Dimer | 0.884 | 84.5 | 0.857 | 76.3 |

| MAPV GnH/Gc | ||||

| Central | 0.873 | 84.6 | 0.812 | 74.8 |

| Neighbor | 0.867 | 76.5 | 0.814 | 63.9 |

| Dimer | 0.870 | 80.6 | 0.816 | 69.4 |

| ANDV GnB | ||||

| Central | 0.882 | 87.1 | ||

Fitting a protomer of ANDV-GnH/Gc (H953F) or MAPV GnH/Gc.

Fitting a dimer of ANDV-GnH/Gc (H953F) or MAPV GnH/Gc and a tetramer of ANDV GnB.

To trap the ANDV GnH/Gc heterodimer in its pre-fusion form, we inspected the structure of post-fusion Gc to find potential mutations interfering with trimer formation. A similar approach has been used to stabilize the pre-fusion conformation of several class I viral fusion proteins (Krarup et al., 2015; Pallesen et al., 2017; Rutten et al., 2020). We noted that the His953 side chain is involved in a tight network of polar interactions with the side chains of Asp679, Lys833, and Asn955 around the molecular 3-fold axis at the center of the Gc trimer (Figure S4A). We introduced the H953F mutation because the bulkier phenylalanine side chain cannot make the same interactions. Furthermore, the H953F mutant has been shown not to interfere with budding of ANDV virion-like particles (VLPs) (Bignon et al., 2019), indicating that it should not affect the Gc pre-fusion conformation. The ANDV GnH/Gc H953F mutant yielded hexagonal crystals diffracting to 3.2-Å resolution (Table 1), in which GnH/Gc adopted an organization very close to that of wild-type MAPV GnH/Gc (Figure S3C). The two complexes could be aligned with a root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of 5.7 Å between all pairs of equivalent Cα atoms (764 in total), although the individual domains superposed to about 0.5-Å RMSD. The structures differed essentially at the level of the hinge of Gc domain II (in the klaefg β sheet; Figure S3D), at its domain I-proximal end. This region has been shown to adopt variable conformations in other class II fusion proteins; for instance, in flaviviruses (Zhang et al., 2004) and phleboviruses (Halldorsson et al., 2018). When we docked the atomic model of ANDV GnH/Gc H953F into the cET map as a single rigid body, resulting in the statistics displayed in Table 2, the altered conformation at the hinge brought domain III to fit well within cET density (Figure S3C, bottom panel; compare with Figure S3A).

To further validate that the interface observed in the crystals indeed corresponded to that of Gn/Gc heterodimers at the viral surface, we used the DbD2 server (Craig and Dombkowski, 2013) to identify pairs of residues facing each other at the GnH/Gc interface with favorable geometry to form inter-chain disulfide bonds when mutated to cysteine (Figure 1D, left panel). We found that mutants H294C/T734C, T99C/P774C, and N94C/V776C (the numbering corresponds to the polyprotein precursor; Figure S1) did not interfere with efficient VLP formation compared with the wild-type construct. SDS-PAGE analysis (Figure 1D, right panel) showed that, although Gn and Gc from wild-type VLPs migrated as monomers (at ~70 and ~55 kDa, respectively) under reducing and non-reducing conditions, Gn and Gc from VLPs formed by the double mutants migrated similarly only upon reduction. In contrast, in a non-reducing gel, these mutants migrated as a single band, corresponding to an ~130 kDa form that was recognized by anti-Gn and anti-Gc antibodies. The presence of this species, which is absent in wild-type VLPs and dissociates into Gn and Gc monomers by addition of a reducing agent, unambiguously indicated the presence of covalently linked heterodimers on the particles. In conclusion, the match to the cET density and the mutagenesis results strongly support the interpretation that the GnH/Gc complex observed in the crystals reflects interactions present on the viral particles.

An Overall Model of the Spike and the Surface Glycoprotein Lattice

We generated a quasi-atomic model for the reference tetrameric spike by applying 4-fold symmetry operations to the ANDV GnH/Gc H953F atomic model docked as a rigid body into the asymmetric unit of the cET map using Chimera (Pettersen et al., 2004). Likewise, we docked one protomer into the asymmetric unit of an adjacent spike and used the 4-fold axis of the reference spike to generate the asymmetric unit of the remaining neighboring spikes (Figures 2A and 2B), which allowed examination of spike-spike contacts. The quasi-atomic model of the resulting (GnH/Gc)4 tetramer filled most of the spike but left an unaccounted density volume at the membrane-proximal side, where most of the 4-fold contacts appear to take place (Figure S5). In the spike model, the C-terminal end of the crystallized GnH construct pointed into this unoccupied density (Figure 2C), strongly suggesting that it should correspond to GnB (Figure 1A). Indeed, the X-ray structure of the GnB tetramer fit very well as a rigid body within this volume of the map (Figure S5, right panels; Table 2), confirming that GnB contributes the most to the intra-spike tetrameric contacts. The separate docking of the GnH/Gc heterodimer and the GnB tetramer thus yielded a complete model of the external region of the hantavirus spike (Video S1). The locations of the last residue of GnH (Glu374) and the first resolved residue of GnB (Cys379) are within the connectivity range of the intervening four residues in an extended conformation (Figure 2C). The C-terminal end of GnB (Gly484) points toward the viral membrane at a location where there is density for a bundle of TM helices resolved in the 11.4-Å-resolution cET map (Figure S5C).

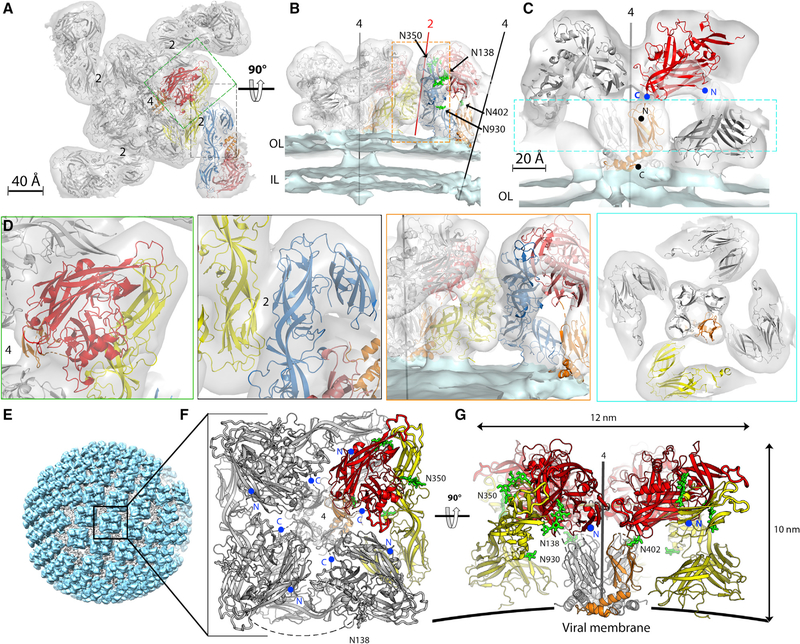

Figure 2. Organization of Hantavirus Gn/Gc Spikes on Virions.

(A) The 11.4-Å-resolution cET-STA map of the Tula virus spike plus the asymmetric unit of its four neighbor spikes viewed from the top, along the 4-fold axis and with the docked X-ray structures of the ANDV GnH/Gc-H953F mutant. One protomer of the spike is colored as in Figure 1. A protomer of the adjacent spike, related by a local 2-fold axis, is highlighted in salmon and blue for GnH and Gc, respectively.

(B) Orthogonal view of the spike with the 4-fold axis in the plane of the figure. The conserved N-linked glycan chains are shown as green sticks and labeled. OL and IL indicate the outer and inner leaflets of the viral membrane, respectively.

(C) Close up of the spike showing the GnB tetramer (for clarity, the Gc moiety in the front was removed). The N and C termini of GnH and GnB are indicated and labeled in blue and black, respectively.

(D) Close ups of selected regions corresponding to the dashed boxes in (A)–(C) to show the quality of the fit, color-framed to match the corresponding boxed areas (dashed lines) in the panels just above (see also Video S1).

(E) Reconstruction of a Tula virus particle generated by back-projecting the 11.4-Å cET/STA density of the spike to the original spike locations on a particle. The resulting surface protein lattice is shown in cyan and the viral membrane in gray.

(F and G) The spike in a top view (F), with one of the four protomers colored as in Figure 1 and the sugar residues in green, and in side view (G). As in (C), the Gc subunit at the forefront (marked by a dashed oval in F) was omitted in (G) to visualize the GnB tetramer at the spike center. The GnH N and C termini are marked as in (C) (only the N-termini in G for clarity).

The model of the spike tetramer further revealed that the N-glycans attached to Asn402 and Asn930 project into internal cavities of the spike (Figures 2B and 2G) and appear to play a stabilizing structural role despite the mobility of the sugar chains. Mutations knocking out glycosylation at these sites have indeed been shown to result in Gn/Gc spike complexes that efficiently reached the Golgi apparatus but were not recognized by certain conformational antibodies (Shi and Elliott, 2004). These observations indicate that the integrity of the (Gn/Gc)4 tetramer may be compromised by the absence of the internal glycan chains, which appear to form a scaffold under the spike surface. The arrangement of Gn and Gc in the spike is also in line with the observation that, in HTNV, the N-linked glycans are of the high-mannose type (Antic et al., 1992; Schmaljohn et al., 1986; Shi and Elliott, 2004) because they appear to be sterically protected from further modification in the Golgi apparatus. Some hantaviruses, such as the Dobrava and Thottapalayam viruses, display additional N-glycosylation motifs in Gn. These other sites are, however, predicted to be exposed at the top of the spike and would project the sugar chains to solvent at the very top, where they would be susceptible to modification to the complex form in the Golgi apparatus.

The quasi-atomic model generated for the hantavirus envelope glycoprotein layer confirmed that the (Gn/Gc)4 spikes are formed essentially by Gn:Gn contacts and that the surface lattice is formed by inter-spike Gc:Gc contacts. The inferred homodimeric Gc:Gc interface is similar to that observed previously in a crystallographic dimer of HNTV Gc crystallized at neutral pH (Figures S4B–S4D; Guardado-Calvo et al., 2016), with an additional contribution from the Gc N-terminal segment, which augments the inner sheet by contributing an additional β-strand (A’0 strand; Figure S1). The relatively small buried surface area (550 Å2 per protomer) suggests that a certain degree of rocking about the inter-spike contacts is allowed, consistent with the pleomorphic nature of the particles. Imposing the exact interactions observed in the crystallographic Gc dimer to the inter-spike contacts resulted in slightly reduced fitting scores in comparison with fitting the individual Gn/Gc protomers (Table 2), possibly because there are more degrees of freedom that could artificially increase the score at this resolution. Overall, our results are in line with the previously reported data showing that mutations guided by the crystallographic HTNV Gc dimer interface affect spike-spike interactions and particle assembly (Bignon et al., 2019).

The model derived previously by docking the X-ray structure of PUUV GnH into the 16-Å resolution Tula virus cET map (Li et al., 2016) with an inverted hand was overall consistent with the new model, with GnH making 4-fold contacts in the spike. The reason is that, at 16-Å resolution, the density at the top of the individual spikes was essentially centrosymmetric, and correction of the hand did not substantially affect the placement of GnH. In contrast, the chirality of the lateral contacts between spikes is quite pronounced, and there was no attempt to dock Gc in that study (Li et al., 2016). A detailed comparison showed that GnH is actually oriented differently in the new spike model, which leads to different exposed surfaces and inter-protomer contacts (compare Figures S2E and S2F). We used our new model of the hantavirus surface glycoprotein lattice to map the available data, most often obtained by Pepscan (Heiskanen et al., 1999; Koch et al., 2003), on sites recognized by monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) targeting different human pathogenic hantaviruses. Most of these data consist of peptides mapping to different regions of the glycoprotein, with some of them corresponding to segments distant from each other in the primary sequence. We found that such segments are brought together in the atomic model to form a continuous patch at the particle surface, indicating the location of the epitope for each mAb. Some of the peptides belong to different protomers but cluster at Gn:Gn and Gc:Gc contact regions at the lattice surface (Figure S2G).

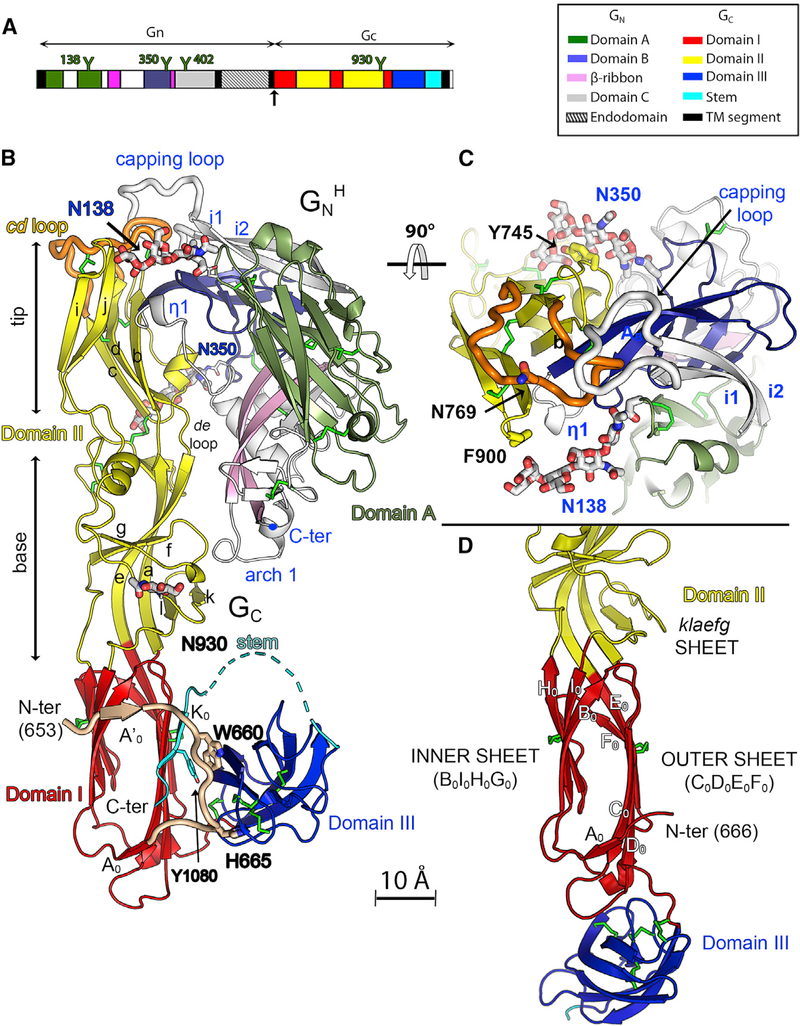

Organization of the GnH/Gc Protomer in the Prefusion Form

As in atypical class II viral fusion protein, the three structured domains of Gc are organized around domain I (red in Figure 3), which is a β sandwich composed of an inner (B0I0HoGo) and an outer (C0D0E0F0) β sheet, where “inner” and “outer” refer to their orientation in the post-fusion trimer (Guardado-Calvo et al., 2016). The D0E0 and H0I0 connections between adjacent domain I β strands form two long excursions (amino acids [aa] 713–804 and 840–949) projecting from one end of the domain I β sandwich to form the elongated domain II (yellow in Figure 3). A flexible linker connects the opposite end of the domain I β sandwich to the IgS domain III (aa 973–1,061, blue in Figure 3), which in turn connects to the C-terminal TM anchor (aa 1,108–1,130) via an extended segment termed “stem” (cyan). Domain II is composed of a domain I-proximal “base” subdomain made of the highly twisted klaefg β sheet (labeled in Figure 1B, right panel) and a couple of short α helices (Figure 2B) and a distal “tip” subdomain composed of the elongated bdc β sheet packing against the ij β hairpin (Figure 2B). The tip exposes the target membrane insertion surface (TMIS) at the distal end of the protein. Unlike the class II fusion proteins from the flaviviruses and alphaviruses, in which the TMIS is composed of a single loop (the cd loop, also called the “fusion loop” and highlighted in orange in Figures 3B and 3C), hantavirus Gc has a tripartite TMIS composed of residues in loops bc (Tyr739), cd (Trp766), and ij (Phe900) (Guardado-Calvo et al., 2016; Guardado-Calvo and Rey, 2017). In the heterodimer, GnH makes extensive interactions with Gc domain II (Figure 3B, top half of the panel). This is the case for the three GnH/Gc structures presented here (Figure 1B), including that with Gc in the post-fusion conformation. The interface between GnH and Gc involves about 1,950–2,050 Å2 of buried surface area (BSA) per polypeptide chain, of which roughly 20% are contacts with N-linked glycans (Figure 3C). The contact regions include conserved surface patches of both glycoproteins (Figure S3E). The Gc pre-fusion conformation is also stabilized by intra-chain interactions between domain III and the domain I outer sheet, which is augmented by an additional β strand (K0, aa 1,077–1,082) formed by residues belonging to the stem (Figure 3B, cyan), and a Gc N-terminal segment (the “N-tail,” aa 652–668, highlighted in light brown in Figure 1B), which is an extension with respect to other viral class II fusion proteins. Three conserved aromatic side chains (W660 and H665 in the N-tail and Y1080 in the stem, labeled in Figure 3B) form a platform interfacing with domain III. The N-tail makes an arch that surrounds domain I, contributing an additional short β strand (A’0) to the domain I inner sheet. The contribution of the stem and the N-tail to the pre-fusion conformation of domain I are features that have not been observed in other viral class II fusion proteins. The previously reported structure of monomeric HTNV Gc at neutral pH, interpreted as displaying a putative “pre-fusion” conformation, had been obtained after controlled proteolysis that cleaved off the stem and therefore lacked the K0 strand (Guardado-Calvo et al., 2016). The N-tail was, in turn, disordered upstream strand A0 (aa 669–672). The absence of these contact sites gave rise to a displaced domain III that resulted in a rod-like Gc molecule in which domains II and III lie at the opposite ends of domain I (Figure 3D). This conformation would be compatible with an extended intermediate form of Gc adopted early during the membrane fusion reaction, as observed in other bunyaviruses (Halldorsson et al., 2018).

Figure 3. The Hantavirus Gn/Gc Pre-fusion Heterodimer.

(A) The single ORF of the hantavirus genomic RNA segment M colored by domains according to the key on the right. N-glycosylation sites are shown as “Y” symbols (ANDV numbering; Figure S1).

(B) The 2.2-Å-resolution X-ray structure of the MAPV GnH/Gc heterodimer colored as in (A), with the disulfide bonds shown in green and the N-glycans displayed as sticks colored according to atom type.

(C) Orthogonal view of the GnH/Gc interface seen from the domain II tip.

(D) Ribbon representation of HNTV Gc monomer (PDB: 5LJY) centered on domain I, showing the extended conformation adopted by Gc in the absence of the stem. Domain I is in the same orientation in (B) and (D). The Gc N-tail in the left panel is highlighted in light brown and displayed as thicker tubes, and the stem is shown in cyan.

The GnH conformation in the complex is essentially the same as that observed in the structures of isolated GnH from PUUV and HTNV reported previously (Li et al., 2016; Rissanen et al., 2017), except for three loops, disordered in those structures, that are involved in interactions with Gc in the heterodimer. Many features of the Gn/Gc complex are reminiscent of the alphavirus p62/E1 glycoprotein heterodimer (Voss et al., 2010). p62 and Gn present three IgS domains (domains A, B, and C) dispersed around a central β ribbon structure (Figure S6). The β ribbon consists of a long, twisted β hairpin encircled by several “arches” that in Gn are more elaborate than in p62, displaying various insertions with additional secondary structure elements. Despite the overall similarity, Gn domains A and B are dispersed differently with respect to each other compared with p62 and have developed different insertions into the core domains to interact within the heterodimer. These differences notwithstanding, in both cases they engage domain II of their partner fusion protein by interacting with the b strand and with the de loop, and both feature an IgS domain C immediately downstream of the β ribbon. Furthermore, the alphavirus icosahedral surface glycoprotein lattice is maintained by intra-spike contacts made exclusively by p62, whereas the in ter-spike 2-fold contacts are mediated by E1 only, just as in the hantavirus Gn/Gc square surface lattice. These similarities indicate that, in addition to E1 and Gc being homologs, Gn and p62 are also evolutionarily related despite having diverged further in structure.

One of the three main Gn regions contacting Gc is the “η1 loop” centered on a 3/10 helical turn (η1 helix, aa 289–291) in the MAPV structure. This loop encompasses a polypeptide segment (aa 277–299) featuring the highly conserved stretch 281-GEDHD-285 across the Orthohantavirus genus (Figure S1). The C-terminal end of the η1 loop forms β strand AB (Figures S3F–S3H) running parallel to β strand b of Gc domain II. A second contact site with Gc involves the Gn arch surrounding the β ribbon (arch 1, aa 202–208, labeled in Figure 3B), which interacts with the fg and kl loops in the hinge region of Gc domain II (Figure 3B). The third set of important interactions is made by the tip of a long β hairpin (i1-i2 hairpin, Figure 3B, top, and Figure 3C), which stands out as an insertion into Gn domain A (Figure S6). The i1-i2 loop at the tip of this β hairpin caps the cd and bc loops of Gc, and we accordingly called it the “capping loop” (aa 88–99). This loop adopts several conformations in the absence of Gc, as shown by the structures of isolated GnH crystallized at different pH values, none of which corresponds to the conformation seen here in the complex with Gc (Figure S3I). A striking additional inter-chain interaction is mediated by the two Gn conserved glycan chains attached at positions N138 and N350, which embrace the tip of domain II (Figure 3C), interacting, respectively, with the side chains of Phe900 and Tyr745, both residues forming part of the Gc TMIS. Removal of either of these glycosylation sites in HTNV has been shown to give rise to defects in intracellular transport of the glycoprotein complex (Shi and Elliott, 2004).

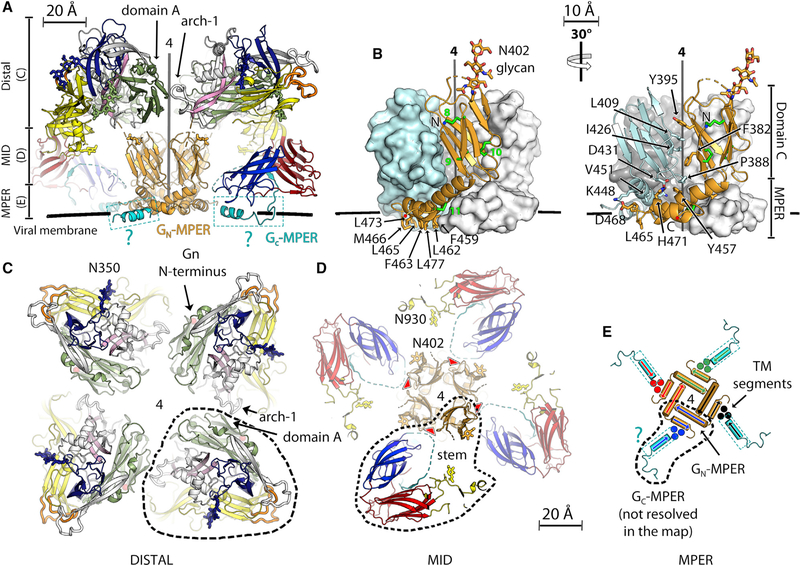

The Intra-spike Interfaces

The quasi-atomic model of the spike shows that the GnH:GnH contacts at the membrane-distal side of the spike are limited to 200 Å2 BSA per protomer and are mediated by the conserved GFC β sheet of domain A and the arch 1 region from the clockwise protomer seen from the top (Figures 4A and 4C). In contrast, the GnB moiety, at the membrane-proximal side, makes most of the Gn:Gn interactions stabilizing the tetrameric spike (Figures 4B, 4D, and 4E). GnB is formed by domain C (aa 379–446), a seven-stranded IgS β sandwich followed by a viral membrane-proximal external region (MPER) (Figure 4B) composed of two amphipathic α helices that form a disulfide-linked α-helical hairpin. The Gn MPER wraps around domain C from an adjacent protomer (Figure 4B) to make an intertwined, compact GnB tetramer with 1,000 A2 of BSA per protomer, distributed equally between domain C and the MPER. Accordingly, a construct containing only domain C (i.e., lacking the Gn MPER) behaved as monomeric in solution (data not shown). Most of the residues that shape the tetrameric interface are conserved across hantaviruses (Figure S1). The base of the tetramer exposes a hydrophobic surface composed of 28 conserved hydrophobic residues (seven per protomer; Figure 4B) facing the viral membrane.

Figure 4. Inter-chain Contacts Stabilizing the Hantavirus Spike.

(A) Side view of the spike, omitting the front Gc subunit for clarity. The four protomers are colored as in Figure 3, with GnB shown in orange. The Gc-MPER, not resolved in the structure, was modeled as an α helix (colored cyan) to indicate its putative location in the lipid head region of the membrane’s outer layer (indicated schematically by a thick black line).

(B) X-ray structure of GnB. Disulfide bonds are indicated in the front protomer as green sticks and numbered. The side chains of non-polar residues of the MPER exposed to the viral membrane are shown as sticks and labeled on the left, whereas the right panel shows the interactions between two protomers with interfacial residues highlighted.

(C–E) Slices of the spike model normal to the 4-fold axis, corresponding to the regions indicated in the vertical bar at the left of (A). A dashed outline follows the contour of one spike protomer along the three radial sections displayed.

(C) Contacts in the membrane-distal region (the spike’s “crown”). The Asn350 glycan is shown as blue sticks.

(D) The spike’s “midregion,” displaying two glycans attached to Asn402 and Asn930 that fill the internal cavities under the spike crown. The segment of the Gc stem that is disordered in the X-ray structure (dotted line in Figure 3B) projects into a cET density volume in close proximity with the reactive groove (red arrowheads) at the GnB tetramer interface (indicated in blue in Figure 1C).

(E) The membrane-proximal region. The two amphipathic helices of the Gn MPER (at the GnB C terminus) and the predicted Gc MPER, which precede the TM segments, form a supporting platform embedded in the OL of the viral membrane. The approximate locations of the three TM segments per protomer are indicated by full blue circles. The directionality of the helices is indicated by arrows. A thin dashed rectangle surrounding theGc MPER helix and the cyan question mark were added to indicate that this segment was not resolved in the X-ray structure.

The GnH/Gc crystals displayed clear density for the Gc stem except for its N-terminal segment (aa 1,063–1,076) between domain III and the K0 strand (Figure 3B). It is possible that this segment of the stem requires GnB to become structured. The crystals of the GnB tetramer included a ligand running within a polar groove between two GnB protomers that was present in both crystal forms and that we interpreted as a short RNA oligonucleotide. This ligand, whose density is displayed as a purple surface in Figure 1C, top panel, copurified with the protein and is not likely to be biologically relevant. However, it revealed the existence of a reactive, positively charged groove along the sides of the GnB tetramer (Figures 1C and 4D), running radially and well placed to accommodate the Glu1066 side chain in the polar N-terminal segment of the Gc stem in the context of the spike, further strengthening the interactions within the tetrameric spike. In the alphavirus p62/E1 complex, the corresponding region of the E1 stem has also been shown to be structured in interaction with p62 domain C (Voss et al., 2010).

The C-terminal part of the stem (aa 1,092–1,107, between the K0 strand and the TM segment; Figure S1) is also disordered in the GnH/Gc crystals. The Psipred server (Buchan and Jones, 2019) predicts this Gc MPER to contain an amphipathic α helix. This segment of 15 amino acids can easily span the 25-Å distance intervening between the last ordered stem residue in the Gc model and the cET density for the Gc TM segment (Figure 4A; Video S1). The Gc MPER would lie parallel to and partially embedded in the viral membrane outer leaflet. At 11-Å resolution it is not resolved in the cET map. Similar MPERs have been described for other class II fusion proteins just upstream of the TM segment (for instance, the envelope protein of dengue virus; Zhang et al., 2013) but also for the class I envelope trimer of HIV (Fu et al., 2018) and the class III fusion protein gB of herpes simplex virus (Cooper et al., 2018). Mutations in this region, such as S1094L, which would increase the Gc MPER amphipathic character, have been reported to increase the infectivity of recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus particles bearing HNTV Gn/Gc glycoproteins (Slough et al., 2019), suggesting that the interaction of the Gc MPER with membranes may affect viral infectivity. Together, the Gn and Gc MPERs appear to form a platform under the spike, interfacing with the viral membrane (Figures 4A and 4E). The compound effect of embedding all or most of these amphipathic helices in the outer leaflet of the lipid bilayer would be expected to significantly affect the curvature of the viral membrane (Martyna et al., 2017).

The Fusogenic Conformational Change of Gc

To better understand the structural reorganization that takes place to drive membrane fusion for entry, we also made constructs of the isolated MAPVand ANDV Gc ectodomains and obtained crystals diffracting to 2.7- and 2.4-Å resolution, respectively (Table 1). The resulting structures revealed Gc in its post-fusion conformation (Figure 5A, central and right panels) even when crystallized at neutral pH, as was the case with the HTNV and PUUV post-fusion Gc trimers reported earlier (Guardado-Calvo et al., 2016; Willensky et al., 2016). Comparison of the pre- and post-fusion conformations of Gc confirmed that the most conspicuous changes are the drastic relocation of domain III and the stem as well as an altered topology of the β strands composing the outer and inner sheets of domain I (Figures S7A and S7E). Similar changes have been reported for the class II fusion proteins from this and other virus families in the pre- and post-fusion forms of domain I (Bressanelli et al., 2004; Gibbons et al., 2004; Halldorsson et al., 2016; Modis et al., 2004).

Figure 5. Conformational Change of the Gc Domain II Tip for TMIS Formation.

(A) The post-fusion conformation. The left and central panels show a top view (along the 3-fold axis) and a side view of the ANDV (Gn/Gc)3 trimer, with Gc in the characteristic post-fusion hairpin conformation displayed in surface representation and Gn shown as green ribbons. One Gc subunit is colored by domains, with Tyr739, Trp766, and Phe900 of the TMIS displayed and labeled. For clarity, the Gn polypeptide chain in the front was omitted in the side view. N-linked glycans are shown as thick sticks. The right panel shows the structure of the ANDV Gc post-fusion trimer crystallized at pH 7.5 and depicted as in the central panel. The horizontal bar indicates the target membrane into which the TMIS would insert.

(B) The tip of MAPV Gc domain II showing the organization of the bc, cd, and ij loops in the pre-fusion (top) and post-fusion (bottom) conformations, from the 2.2- and 2.4-Å resolution structures, respectively (Table 1). The left and right panels show two orthogonal views, as indicated. Side chains important for target membrane insertion and forming the polar network around Glu757-Asp759 are highlighted. In the pre-fusion conformation, the bc and ij loops are buried by the Gn N138 glycan and the capping loop, respectively, as indicated.

Unlike the class II fusion proteins studied so far, the domain II tip in the pre-fusion form adopts an alternative conformation, stabilized by Gn, in which the TMIS is not formed (Figure 5B). The side chains of three key residues of the TMIS (Trp766, Tyr745, and Phe900, which have been shown previously to be crucial for Gc binding to target membranes [Guardado-Calvo et al., 2016]) are not exposed. The observed reorganization of the tip mainly affects the cd loop, which, in the post-fusion form, makes an α-helical turn exposing the side chain of Trp766 and burying that of Asn769. In contrast, in the pre-fusion form, the Trp766 side chain is buried and that of Asn769 is exposed to solvent (Figures 5B and S7D). This rearrangement results in a drop in surface hydrophobicity at this critical membrane-interacting region. The remaining non-polar side chains are covered by the capping loop of Gn, which cloaks part of the cd loop and the bc loop, and the N138 glycan, which stacks against Phe900 and covers the ij loop.

What controls the observed reorganization of the tip is unknown, but the unusual carboxylate/carboxylic acid hydrogen bond between the side chains of the strictly conserved Glu757 and Asp759 (Guardado-Calvo et al., 2016) is likely to play a role. We observed that this acid hydrogen bond is required for structuring the tip of domain II in the post-fusion conformation. The presence of Gn reshapes the bc loop so that the neighboring Lys744 makes a hydrogen bond/salt bridge with Asp759, preventing formation of the acidic hydrogen bond and precluding the cd loop from exposing Trp766 (Figure S7F). How the changes in the bc loop are transmitted to the cd and ij loops remains an open question.

DISCUSSION

Our study revealed the organization of the hantavirus surface glycoprotein lattice by describing the X-ray structures of ANDV and MAPV GnH/Gc heterodimers featuring Gc in the pre-fusion conformation, the conserved tetrameric GnB of ANDV, and their rigid body fitting into an 11.4-Å resolution cET map of Tula hantavirus. Given the high amino acid sequence similarity between the envelope glycoproteins, the model presented here is expected to be valid for all hantaviruses. The GnH/Gc structures also revealed the role played by the N-terminal tail and stem of Gc in stabilizing the interaction between domains I and III in the metastable pre-fusion form. In addition, the effect of Gn in the conformation of the Gc tip revealed the way Gn protects from premature TMIS formation. These features have not been observed previously in other class II fusion proteins. Because the domain II tip displays clear amino acid sequence conservation with its counterpart in nairoviruses and orthobunyaviruses, the observed protection mechanism can potentially be extrapolated to the fusion machinery of these more distant human pathogenic bunyaviruses.

The evolutionary history of the class II fusion proteins remains enigmatic. They have been identified in positive- and negativesense single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) viruses as well as in multiple and varied eukaryotic organisms, where they drive fusion of gametes and somatic cells (Fedry et al., 2017; Pérez-Vargas et al., 2014). Their complex but highly conserved 3D fold is strong evidence of common ancestry despite the absence of any remnants of sequence conservation (Modis, 2014). We show here that the similarity in the viral proteins extends beyond the actual fusion effector protein to include the accompanying protein, as in the case of alphaviruses and hantaviruses. Indeed, despite major differences, we found that the overall organization of the hantavirus spike showed striking parallels with that of the alphavirus spike. These include the roles of domains A and C of Gn, which, like their counterparts in alphavirus p62, make intra-spike contacts, whereas Gc, like its alphavirus E1 counterpart, provides lateral contacts between spikes. The flavivirus example also shows that, in some cases, the accompanying protein has been substituted during evolution, as seems to be the case with the flavivirus prM/E heterodimer (Li et al., 2008). Even in this case, the accompanying protein prM binds to the domain II tip by interacting with β strand b in an apparently universal fashion.

The quasi-atomic model of the spike presented here provides a framework to understand an accumulating body of data on hantavirus biology. The conserved N-linked glycans, which were observed to be buried in the spike and remain high mannose in released viral particles, are a prime example. Our structures support the hypothesis that the tetrameric spikes form early in the ER, before they are transported to the Golgi apparatus. The sugar chains are then not accessible to the glycosyl transferases that modify the glycan chains buried within the tetramer. As the sugar chains are buried, they are not used as a shield to evade the immune system as in other viruses, nor as cellular attachment factors as in alphaviruses, flaviviruses, or phleboviruses (Watanabe et al., 2019). Rather, the glycans appear to play an intrinsic structural role by forming an internal scaffold.

Previous studies have reported a dynamic behavior of hantavirus spikes, which exhibit a temperature-dependent equilibrium between two conformational states that co-exist at physiological temperatures (Bignon et al., 2019), a process called “breathing”: the closed form, which does not bind membranes at neutral pH but is functional in acidic pH-induced membrane fusion, and the open form, which binds membranes even at neutral pH but is unable to drive membrane fusion upon exposure to acidic pH. The structure of the GnH/Gc heterodimer presented in this manuscript appears to reflect the closed form because the capping loop partially shields the TMIS, and the Trp766 side chain is buried. The open form probably results from partial dissociation of the heterodimer, leading to a change in the conformation of the cd loop in Gc and its interaction with membranes. It has been hypothesized that spike breathing may provide advantages to establish persistent infection in rodents by exposing decoy epitopes that elicit a poorly neutralizing response (Bignon et al., 2019). In line with this hypothesis, neutralizing antibodies isolated from mice (Xu et al., 2002) and bank voles (Lundkvist and Niklasson, 1992) that were immunized with inactivated HNTV- and PUUV-infected tissues, respectively, recognize epitopes occluded in the closed form (Figures S2E–S2G) but can be transiently exposed as the spike breathes.

The atomic model of the hantavirus spike paves the way for development of novel immunogens. For a certain category of enveloped viruses, designing subunit vaccines using the recombinant fusion glycoprotein ectodomain for immunization has been complicated by the spontaneous and irreversible switch to the post-fusion form, which does not expose the relevant epitopes targeted by neutralizing antibodies. One example is the respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) fusion glycoprotein, which requires mutagenesis to stabilize its pre-fusion conformation (Krarup et al., 2015) and expose the right epitopes to elicit strongly neutralizing antibodies. We found a similar situation with the ANDV GnH/Gc complex, and we describe one way of interfering with adoption of the post-fusion form by introducing the H953F mutation. We also validated our model of the spike by designing disulfide bridges crosslinking the Gn/Gc protomer, providing proof of principle that such additional stabilization is feasible. Our results make it possible to further investigate inter-protomer disulfide bonds to stabilize the overall spike tetramer as a potential next-generation immunogen. Because spike “breathing” has been demonstrated in ANDV and other hantaviruses that cause severe disease in humans, envelope glycoproteins engineered as proposed here should provide superior immunogens for eliciting highly potent neutralizing antibodies targeting the closed form of the spike.

STAR★METHODS

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead Contact

Further information and request for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact Felix A. Rey (rey@pasteur.fr).

Materials Availability

The unique/stable reagents generated in this study are available from the Lead Contact with a completed Materials Transfer Agreement.

Data and Code Availability

The atomic coordinates and structure factors of the X-ray structures have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (https://www.pdb.org) with accession codes 6Y5W, 6Y5F, 6Y62,6Y68,6Y6Q, 6Y6P, 6YRB, and 6YRQ. The cET map has been deposited in the Electron Microscopy Data Bank (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/pdbe/emdb/) with accession number EMD-11236. Atomic coordinates of the tetrameric spike quasi-atomic model have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank with the accession code 6ZJM. The previously reported “inverted” map EMD-3364 has been redeposited with accession code EMD-4867. The scripts used to process the cryo-ET data are available at https://github.com/OPIC-Oxford/TomoPreprocess (TomoPreprocess) and https://github.com/OPIC-Oxford/PatchFinder (PatchFinder).

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Cell lines

Drosophila S2 cells (ThermoFisher) line was derived from a primary culture of late stage Drosophila melanogaster embryos. They were grown at 28C in serum-free insect cell medium (GE Healthcare HyClone). 293FT cells (Thermo Fisher Scientific) is a female human embryonic kidney cell line. They were grown at 37C with 8% CO2 in DMEM medium (ThermoFisher) supplemented with 10% FCS. Vero E6 cells (CRL-1587) were purchased from ATCC and culture in DMEM media (Sigma) supplemented with 3% fetal calf serum (FCS).

METHOD DETAILS

Protein expression and purification

In order to obtain a soluble Gn/Gc complex amenable to crystallize, we followed the approach used to crystallize the alphavirus p62/E1 glycoprotein heterodimer ectodomains (Li et al., 2010; Voss et al., 2010). The strategy involved making single-chain constructs spanning the ectodomains of both glycoproteins, in this case the hantavirus Gn and Gc, bypassing the TM segments in the precursor polyprotein by a soluble, flexible linker. The linker we used was 43-amino acids long in total with aa sequence GGSGLVPRGSGGGSGGGSWSHPQFEKGGGTGGGTLVPRGSGTGG. It contained two thrombin cleavage sites (underlined) at either end and a strep-tag sequence (in bold) in the middle, separated by flexible GGGS or GGGT repeats. To optimize protein production and help in the purification, we cloned synthetic codon-optimized genes for expression in Drosophila cells (Genscript) into a modified pMT/BiP plasmid (Invitrogen, hereafter termed pT350), which translates the protein in frame with an enterokinase cleavage site and a double strep-tag at the C-terminal end of the Gc sequence.

The plasmids generated were used to obtain stable transfectants of Drosophila S2 cells together with the pCoPuro plasmid (ratio 1:20) for puromycin selection. The stable cell lines were selected and maintained in serum-free insect cell medium (GE Healthcare HyClone) containing 7 μg/ml puromycin. Cultures of 1 l were grown in spinner flasks in serum-free insect cell medium (GE Healthcare HyClone) supplemented with 1% penicillin/streptomycin antibiotics to about 1 × 107 cells/mL, and the protein expression was induced with 4 μM CdCl2. After 5 days, the S2 media supernatant was concentrated to 40 mL and supplemented with 10 μg/mL avidin and 0.1M Tris-HCl pH 8.0, centrifuged 30 minutes at 20,000 g and purified by strep-tactin affinity chromatography followed size exclusion chromatography using a Superdex 200 10/30 column (GE Healthcare) in 10 mM Tris-HCl 8.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1mM EDTA (hereafter buffer TN).

Initially, we produced a single chain containing the complete ectodomains of Gn (aa 21–484) and Gc (aa 652–1107) of Andes virus (strain Chile-9717869, NCBI code NP_604472.1). The majority of the protein obtained with this construct formed heterogeneous aggregates from which we could not obtain crystals. We therefore generated a different construct with the linker described above joining the Gn head (GnH, aa 21–374; Figure S1A; Li et al., 2016; Rissanen et al., 2017) to the complete Gc ectodomain. Drosophila Schneider 2 cells stably transfected with the GnH/Gc construct secreted large amounts of protein, which were purified using affinity and size exclusion chromatography (SEC). The proteins behaved mostly as monomers in solution as assessed by multi-angle light scattering (MALS) (data not shown). Using the same approach, we produced GnH/Gc heterodimers from two hantavirus orthologs, Maporal virus (MAPV, strain HV-97021050, NCBI code YP_009362281.1) and from Longquan virus (LQNV, strain Longquan-Ra-90, NCBI code AGI62346.1). We also introduced the H953F mutation in Gc of the Andes virus construct to destabilize its transition to the post-fusion form (as explained in the text). The aa sequence identity of the polyprotein precursor of Andes viruses with MAPV and LQNV is 85% and 40%, respectively. All constructs yielded large amount of soluble GnH/Gc secreted into the cell’s supernatant. The LQNV construct led to the secretion of large molecular weight aggregates only, whose characterization we did not pursue.

We used the same plasmid for S2 cells expression to produce the isolated HNTV GnH (strain 76–118, UniprotKB code P08668.1), the complete ANDV and MAPV Gc ectodomains, ANDV GnB (aa. 375–484) and the isolated ANDV Gn domain C (aa 375–450). All these constructs secreted large amounts of protein that could be purified to homogeneity by affinity and size exclusion chromatography.

Crystallization and structure determination

GnH/Gc heterodimers

The fractions eluted from the SEC run corresponding to monomeric ANDV-GnH/Gc, ANDV-GnH/Gc-H953F, and MAPV-GnH/Gc were concentrated to 7 mg/mL using a Vivaspin centricon in 10 mM Tris-HCl 8.5, 150 mM NaCl (buffer TN). The flexible linker joining GnH and Gc was removed by adding 1 unit of biotinylated thrombin (Novagen) per mg of protein, and the mixture was incubated for 5 days at 4°C until the digestion was completed as judged by SDS-PAGE. These samples were used without further purification in crystallization trials at 18°C using the sitting-drop vapor diffusion method. Crystals of ANDV-GnH/Gc grew in the presence of 15%–16% (w/v) PEG 3350, 125–400 mM potassium acetate, those of ANDV-GnH/Gc-H953F in 2.4M (NH4)2HPO4, 0.1 M Tris-HCl pH 8.5, and those of MAPV-GnH/Gc in 0.1 M MgCl2, 0.1 M Tris pH 8.5 and 17% (w/v) PEG 20000. Crystals were flash-frozen by immersion into a cryo-protectant containing the crystallization solution supplemented with 20% (v/v) glycerol, followed by rapid transfer into liquid nitrogen.

The structure of ANDV-GnH/Gc was solved by molecular replacement (MR) with Phaser from the suite PHENIX (Liebschner et al., 2019) using PUUV GnH (PDB code 5FXU) and HNTV-Gc (5lJY) as search models. The final model was built by combining real space model building in Coot (Emsley et al., 2010) with reciprocal space refinement with phenix.refine. The final model, which was validated with Molprobity (Williams et al., 2018), contained aa 23–374 of Gn and 659–1069 of Gc with two disordered regions: aa 124–126 (loop i2DA) and 697–702 (loop C0D0). The structures of ANDV-GnH/Gc-H953F, and MAPV-Gn H/Gc were obtained by MR using the structure of ANDV-Gn H/Gc as search model. The final model of ANDV-GnH/Gc-H953F contains aa 22–374 in Gn and 661–1092 in Gc, with a break at Gc residues 1063–1076 (the N-terminal part of the stem). The structure of MAPV-GnH/Gc contains aa 22–374 in Gn and 653–1083 in Gc; the N-terminal part of the stem (residues 1065–1076) was also disordered.

Gc postfusion trimers

The protein from the SEC factions corresponding to monomers of ANDV-Gc and MAPV-Gc was concentrated to around 10 mg/mL in TN buffer and used in crystallization experiments. Crystals of MAPV-Gc appeared in an acidic condition containing 30% (v/v) PEG 400, 0.1 M CdCl2, 0.1M Na-acetate pH 4.6. The structures were determined by MR using HNTV-Gc (5LJZ) as initial model, showed the characteristic post-fusion trimeric conformation of Gc around a crystallographic 3-fold axis. The final model contains aa 657–1069 without internal breaks. Crystals of proteolyzed ANDV-GnH/Gc were grown in a condition containing 16% (w/v) PEG 4000, 10% (v/v) 2-propanol, 0.2M (NH4)2SO4, 0.1M HEPES pH 7.5. The final model contains aa 659–1069 and showed density for almost all the residues but three short breaks: 697–700 (loop C0D0), 765–766 and 775–778 (loop cd).

ANDV GnB crystals

The purified protein was concentrated to around 7 mg/mL in TN buffer for crystallization trials. Crystals appeared after 2–4 months at 18°C in two different conditions: 30% (v/v) MPD, 20 mM CaCl2, 0.1 M Na-acetate pH 4.6 (hereafter termed the acidic condition), and 35% (v/v) MPD, 0.2M NaCl, 0.1 M HEPES pH 7.5 (the neutral pH condition). Crystals growing in the acidic condition belonged to orthorhombic C2221 space group and diffracted to 1.9 Å resolution. The Mathews coefficient (Kantardjieff and Rupp, 2003) indicated 4 molecules in the asymmetric unit, and a self-rotation function clearly indicated the presence of a non-crystallographic 4-fold axis. Crystals grown in the neutral pH condition belonged to the tetragonal space group I4 with two molecules in the asymmetric unit and diffracted to 2.4 Å resolution. We used experimental phasing with sodium iodide to determine their structure, as we found no good search model for MR. We soaked crystals for 20 minutes in mother liquor supplemented with 500 mM Nal before plunging them directly into liquid nitrogen. In order to optimize the anomalous signal, we collected a highly redundant dataset merging three independent datasets collected from two different crystals using a kappa goniometer. The final SAD dataset showed anomalous signal up to 3.6 Å. Substructure determination and phasing were carried out using the SHELX suite (Sheldrick, 2010) and an initial model was built using Phenix AutoBuild (Terwilliger et al., 2008). The final model was obtained by combining real space model building in Coot with reciprocal space refinement using phenix.refine. It contains aa 379–483 without Ramachandran outliers. Unexpectely, we found clear density between protomers in the tetramer that could be assigned a short RNA oligonucleotide (3 pyrimidine nucleotides). We used this model to solve the structure of the crystals grown at acidic pH by molecular replacement. The structure showed 4 molecules in the asymmetric unit forming a tetramer virtually identical to that observed at neutral pH, including the presence of the RNA oligo between protomers.

Crystals of HTNV GnH at neutral pH

The reported structures of HNTV GnH were derived from crystals grown at acidic pH (Rissanen et al., 2017). We determined the HTNV GnH structure at neutral pH by concentrating the purified protein in TN buffer and made crystallization experiments at 18°C. We obtained crystals diffracting to 1.9 Å growing at pH 7.5 in a condition containing 25% (w/v) PEG 6000, 0.1M LiCl, 0.1M HEPES pH 7.5, and 20% (v/v) glycerol. We determined the structure using PUUV GnH (5FXU) as search model. The resulting HTNV GnH structure resolved aa 20–373 with a single internal break in the η1 loop (aa 281–290).

The X-ray diffraction data reported in this manuscript were recorded at beamlines Proxima I and II at the Synchrotron Soleil (St. Aubin, France). The statistics of all the crystals and refinement are provided in Table 1.

Amino acid sequence conservation analyses

The conservation scores per residue shown in Figures S1 and S3 were obtained by using the program Espript (Robert and Gouet, 2014) and a multiple sequence alignment generated by Clustal omega (Sievers et al., 2011) using a set of 69 hantavirus M segment sequences extracted from (Zhang et al., 2013). The GenBank accession numbers for the sequences used in the analysis are: JX465398, JX465397, JX465402, JX465399, JX465400, JX465401, JF784178, NC_010708, EF641799, EF641806, HQ834696, FJ539167, EU929073, EU929074, HM015219, EF543526, JX465390, JX465391, JX465392, JX465393, JX465394, JX465395, JX465403, Y00386, AF143675, AB620029, AY675353, AB027115, GF796031, AY168577, AJ410616, GQ205412, AY961616, JQ082301, AF288298, GU592827, EF990916, L08756, GQ274938, HM756287, AB297666, AB433850, EF198413, AJ011648, EU072489, AJ011647, EU072488, Z69993, X55129, L36930, DQ177347, L39950, DQ284451, DQ285047, AB620104, AB620107, U26828, AB620101, U36801, U36802, AF030551, L33474, L37903, AF291703, AF028024, AF005728, FJ608550, AY363179, AF307323.

VLP expression and design of Gn/Gc cysteine mutants

For ANDV VLP expression we used the plasmid pI.18/GPC that encodes the full-length glycoprotein precursor of ANDV strain CHI- 7913 under the control of the cytomegalovirus promotor (Cifuentes-Muñoz et al., 2011). Site-directed mutagenesis was done by DNA synthesis and sub-cloning into pI.18/GPC using intrinsic restriction sites (GenScript). Briefly, 293FT cells (Thermo Fisher Scientific) maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS were grown in 100 mm plates and calcium-transfected with the pI.18/GPC wild-type or the different mutant constructs. 48 h later the cell surface proteins were labeled with biotin in order to separate the biotinylated (surface proteins) from non-biotinylated (intracellular proteins) fractions using a cell surface protein isolation kit (Pierce). For protein detection, two western blots were made separately for each of three independent VLP preparations, using primary anti-Gc monoclonal antibodies 2H4/F6 and 5D11/G7 (Cifuentes-Muñoz et al., 2011; Godoy et al., 2009), anti-Gn monoclonal antibody 6B9/F5 (Cifuentes-Muñoz et al., 2011) or anti-β-actin Mab (Sigma) were used at 1:2.500 and subsequently detected with an anti-mouse immunoglobulin horseradish peroxidase conjugate (Thermo Fisher Scientific) 1:5.000 and a chemiluminescent substrate (Pierce). All these antibodies were previously characterized (Cifuentes-Muñoz et al., 2011). For Gn/Gc VLP production, the supernatant of transfected 293FT cells were harvested at 48 h post-transfection and concentrated as previously established (Acuña et al., 2015).

Tula virus growth and purification

Tula virus (TULV, strain Moravia) was cultivated on Vero E6 cells (ATCC 94 CRL-1586), as previously described (Huiskonen et al., 2010). Four days post infection (dpi), the growth medium (DMEM, Sigma) was replaced by medium supplemented with 3% fetal calf serum (FCS). At 5, 6 and 7 dpi the virus-containing medium was collected and clarified by centrifugation (3,000 × g for 30 min) to remove large cell debris. The medium was then concentrated 100-fold using a 100-kDa cut-off filter (Amicon) and placed on top of a25%–65% sucrose density gradient (in standard buffer [20 mM Tris and 100 mM NaCI pH 7.0]) in aSW32.1 tube (Beckman Coulter), and the virus was banded by ultracentrifugation (SW32 Ti rotor, 25,000 rpm, 4°C, 12 h). Virus-containing fractions were pooled and diluted 1:1 in 20 mM Tris and 100 mM NaCI before pelleting by ultracentrifugation (Beckman Coulter TLS 55 rotor, 50,000 rpm, 4°C, 2 h). The virus pellet was resuspended in the standard buffer.

An aliquot (3 μl) of each sample was applied to 1.2-pm hole carbon grids (C-flat, Protochips) that were then floated on a droplet of standard buffer to remove residual sucrose. An aliquot (3 μl) of 6-nm gold fiducial markers was added to enable tilt series alignment. The sample was then vitrified by plunge freezing to liquid ethane-propane mixture by using a vitrification apparatus (CP3, Leica).

Chirality of the hantavirus spike

To experimentally assess the hand of the Tula virus cET map, we prepared EM grids as previously described with Tula virus particles premixed with a sample of recombinantly produced human papillomavirus type 16 (HPV16) pseudovirus capsids (a kind gift from Dr. Kay Grünewald). HPV particles are chiral, and their hand is known from previous studies (Conway and Meyers, 2009) and can be used as reference. We collected a total of 7 tilt series from −45 to 45 degrees in 5-degree increments with a dose of 5.5 e−/Å2 per tilt. For each tilt image, we acquired 8 movie frames at a calibrated magnification of × 37,037, corresponding to a pixel size of 1.35 Å. The defocus ranged from 3 μm to 4 μm between the tilt series. We reconstructed the tomograms as described in the paragraph below. We did STA of both TULV spikes and HPV particles in Dynamo following exactly the same workflow, using initial references low pass filtered at 50 Å to limit model bias. We imposed icosahedral symmetry for HPV averaging using as reference the EMD-5991 map (Lee et al., 2015) and C4 symmetry for TULV averaging using as reference EMD-3364 (Li et al., 2016). Because of potential template bias, we did multiple refinements changing the hand of the reference, or using a centrosymmetric map obtained by averaging the reference map with its mirror image, thereby eliminating any potential template bias. For HPV, the procedure using the centrosymmetric reference converged to the correct hand, while using the mirror image it did not. For Tula virus, the procedure converged to the same hand in all cases (Figure S2).

EM Data Acquisition and Processing

To improve the resolution of the TULV cET map, we collected additional datasets using aTecnai F30 “Polara” transmission electron microscope (FEI) operated at 300 kV and at liquid nitrogen temperature. We used SerialEM (Mastronarde, 2005) to acquire images on a direct electron detector (K2 Summit; Gatan) mounted behind an energy filter (QIF Quantum LS; Gatan). The dataset included a total of 49 tilt series from −30 to 60 degrees in 3-degree increments with a dose of 4.7 e−/Å2 per tilt. Each tilt image was composed of 6 movie frames at a calibrated magnification of × 25,000, corresponding to a pixel size of 2 Å. The defocus ranged from 2.5 μm to 4.0 μm between the tilt series. Movie frames were aligned and averaged using motioncor2 to correct for beam induced motion (Zheng et al., 2017). Contrast transfer function (CTF) parameters were estimated using CTFFIND4 (Rohou and Grigorieff, 2015) and a dose-weighting filter was applied to the images according to their accumulated electron dose as described previously (Grant and Grigorieff, 2015). These pre-processing steps were carried out using a custom set of scripts named “tomo_preprocess” (https://github.com/OPIC-Oxford/TomoPreprocess). Tilt images were then aligned using gold fiducial markers in IMOD (Kremer et al., 1996), corrected for the effect of CTF by phase flipping and used to reconstruct the tomograms by weighted back projection in IMOD (Mastronarde and Held, 2017). Subtomogram averaging was performed in Dynamo (Castaño-Díez et al., 2012). Initial particles for this refinement were created by modeling the surface of the membrane using the Dynamo’s tomoview function and defining their initial orientation normal to this surface. These initial ‘seeds’ were more densely populated than the true spikes and overlapping spikes were removed based on cross-correlation after each iteration in the refinement. Refinements were carried out with C4 symmetry using the existing Tula virus spike map as a reference (EMD-3364). The map was low-pass filtered to 50 Å resolution to avoid model bias. A custom script (PatchFinder; available at https://github.com/OPIC-Oxford/PatchFinder) was used to restrict the dataset to only those particles that having regular glycoprotein surface patches. The script locates the eight closest spikes for each particle, and these are classified as interacting neighbors only if their lattice constraints are within set tolerances (maximum 49-Å and 25-degree deviation from expected location). Spikes were defined as being part of a lattice if they had at least three interacting neighbors. The final dataset was subjected to 3D classification in RELION (Bharat and Scheres, 2016) before further refinement in Dynamo. The amplitudes of the final maps were weighted to correct for the effect of dose-weighting of the original images using a custom script (available on request). The final reconstruction, comprised of ~18,064 subvolumes, was filtered to 11.4 Å as determined by FSC (0.143 threshold). The threshold value for the rendered isosurface was determined according to the molecular weight of the viral ectodomain proteins assuming an average protein density of 0.81 Da/Å3.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Two separate western-blots were performed on each of the three independent preparations (n = 3) of each sample as described in the STAR Methods section.

Supplementary Material

KEY RESOURCES TABLE.

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Anti-Gc monoclonal antibody 2H4/F6 | Godoy et al., 2009 | N/A |

| Anti-Gc monoclonal antibody 5D11/G7 | Cifuentes-Muñoz et al., 2011 | N/A |

| Anti-Gn monoclonal antibody 6B9/F5 | Cifuentes-Muñoz et al., 2011 | N/A |

| Anti-β-actin monoclonal antibody | Sigma | Cat #A2228 |

| Anti-mouse immunoglobulin horseradish peroxidase conjugate | ThermoFischer | Cat #32230 |

| Bacterial and Virus Strains | ||

| Tula virus Moravian strain 5302 | Huiskonen et al., 2010 | N/A |

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| Thrombin | Novagen | Cat #69671-3 |

| Serum-free insect cell medium | Hyclone | Cat #SH30913.02 |

| Cell surface protein isolation kit | Pierce | Cat#89881 |

| DMEM medium | Sigma | Cat #11995073 |

| Deposited Data | ||

| Tula virus CryoET maps | This paper | EMD: 11236 |

| Tula virus CryoET maps | This paper | EMD: 4867 |

| Atomic coordinates and structure factors for ANDV-GnHGc | This paper | PDB: 6Y5W |

| Atomic coordinates and structure factors for ANDV-GnHGc (H953F) | This paper | PDB: 6Y5F |

| Atomic coordinates and structure factors for MAPV-GnHGc | This paper | PDB: 6Y62 |

| Atomic coordinates and structure factors forANDV-Gc | This paper | PDB: 6Y6Q |

| Atomic coordinates and structure factors for MAPV-Gc | This paper | PDB: 6Y68 |

| Atomic coordinates and structure factors for HNTV-GnH | This paper | PDB: 6Y6P |

| Atomic coordinates and structure factors for ANDV-GnB (pH 4.6) | This paper | PDB: 6YRQ |

| Atomic coordinates and structure factors for ANDV-GnB (pH 7.5) | This paper | PDB: 6YRB |

| Atomic coordinates of the tetrameric spike quasi-atomic model | This paper | PDB: 6ZJM |

| Experimental Models: Cell Lines | ||

| Drosophila S2 cells | ThermoFischer | Cat #R69007 |

| 293FT cells | ThermoFischer | Cat #R79007 |

| Vero E6 cells | ATCC | CRL-1587 |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| pT350-MAPV GnH/Gc | Genscript | N/A |

| pT350-ANDV GnH/Gc | Genscript | N/A |

| pT350-ANDV GnH/Gc (H953F) | Genscript | N/A |

| pT350-ANDV GnB | Genscript | N/A |

| pT350-ANDV Gc | Genscript | N/A |

| pT350-MAPV Gc | Genscript | N/A |

| pT350-HNTV GnH | Genscript | N/A |

| pI.18/ANDV GPC | Cifuentes-Muñoz et al., 2011 | N/A |

| pI.18/ANDV GPC H294C-T734C | Genscript | N/A |

| pI.18/ANDV GPC T99C-P774C | Genscript | N/A |

| pI.18/ANDV GPC N94C-V776C | Genscript | N/A |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| Phenix suite | Liebschner et al., 2019 | https://www.phenix-online.org/ |

| Coot | Emsley et al., 2010 | https://www2.mrc-lmb.cam.ac.uk/personal/pemsley/coot/ |

| Molprobity | Williams et al., 2018 | http://molprobity.biochem.duke.edu/ |

| ESPript | Sievers et al., 2011 | http://espript.ibcp.fr/ESPript/ESPript/ |

| SerialEM | Mastronarde, 2005 | https://bio3d.colorado.edu/SerialEM/ |

| CTFind4 | Rohou and Grigorieff, 2015 | https://grigoriefflab.umassmed.edu/software_download |

| IMOD | Kremer et al., 1996 | https://bio3d.colorado.edu/imod/ |

| Dynamo | Castaño-Díez et al., 2012 | https://wiki.dynamo.biozentrum.unibas.ch/w/index.php/Main_Page |

| Relion | Bharat and Scheres, 2016 | https://www3.mrc-lmb.cam.ac.uk/relion/index.php?title=Main_Page |

| Other | ||

| C-flat grids | Protochips | Cat #CF-1.2/1.3-3CU-50 |

| Superdex 200 | GE-Healthcare | Cat #GE29321905 |

| Streptrap HP | GE-Healthcare | Cat # 29-0486-53 |

Highlights.

Atomic model of the hantavirus square surface glycoprotein lattice

Organization of the homotetrameric Gn base at atomic resolution

Control mechanism of Gc fusion loop exposure exerted by Gn on the spikes

Evolutionary links between alphaviruses and hantaviruses revealed by the glycoproteins

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS