Abstract

Elevated intraocular pressure is the primary risk factor for glaucoma, yet vascular health and ocular hemodynamics have also been established as important risk factors for the disease. The precise physiological mechanisms and processes by which flow impairment and reduced tissue oxygenation relate to retinal ganglion cell death are not fully known. Mathematical modeling has emerged as a useful tool to help decipher the role of hemodynamic alterations in glaucoma. Several previous models of the retinal microvasculature and tissue have investigated the individual impact of spatial heterogeneity, flow regulation, and oxygen transport on the system. This study combines all three of these components into a heterogeneous mathematical model of retinal arterioles that includes oxygen transport and acute flow regulation in response to changes in pressure, shear stress, and oxygen demand. The metabolic signal (Si) is implemented as a wall-derived signal that reflects the oxygen deficit along the network, and three cases of conduction are considered: no conduction, a constant signal, and a flow-weighted signal. The model shows that the heterogeneity of the downstream signal serves to regulate flow better than a constant conducted response. In fact, the increases in average tissue PO2 due to a flow-weighted signal are often more significant than if the entire level of signal is increased. Such theoretical work supports the importance of the non-uniform structure of the retinal vasculature when assessing the capability and/or dysfunction of blood flow regulation in the retinal microcirculation.

Keywords: Mathematical mode, blood flow regulation, oxygen transport, retina, heterogeneous vascular network

1. Introduction

Primary open angle glaucoma (OAG) is the second-leading cause of blindness worldwide and is characterized by progressive retinal ganglion cell death and irreversible loss of vision. Glaucoma is a heterogeneous disease that differentially affects groups by age, race, and gender, and has high individual variation in associated risk factors [1]. While reduction of intraocular pressure (IOP) remains the only approved therapeutic option, many individuals will develop OAG and/or continue to have disease progression despite low and/or medically lowered IOP. Vascular health and ocular hemodynamics have been well-established as risk variables in many patients [2], yet we do not have a full understanding of retinal blood flow, structure, and ganglion cell health in glaucoma. Previous experimental studies have established relationships between retinal structure and function, while other clinical studies have shown a very significant correlation between retinal function and blood flow/hemodynamics [3, 4]. While there is evidence indicating that glaucomatous damage precedes structural changes, the exact physiological mechanisms and order of events related to ganglion cell death remain poorly understood.

The eye is highly complex, and many ocular tissues and their physiological interactions are difficult to image and observe in vivo. Theoretical modeling has emerged as a valuable tool [1, 5-12] to identify the specific mechanisms that combine to impair retinal blood flow and influence the course of glaucomatous disease. Previous mathematical models of the retinal microvasculature and tissue have been developed that account for some of the factors that influence retinal blood flow and oxygenation (Figure 1). The vessel network supplying the tissue is heterogeneous, with wide variations in vessel size, spacing, density, and path length. The vessel network structure, capacity for flow regulation, and transport processes of oxygen are key factors that affect perfusion and oxygenation of the retina. Some models have considered all of these factors in the context of longer-term structural adaptation in the developing retinal microvasculature [11, 12]. However, acute time frame mathematical models of the retina have included some of these factors, but not all. For example, some modeling studies have accounted for blood flow regulation in the retinal microcirculation [5, 13]; however, these have assumed a uniform structure to the vascular network. Studies that have included a more complex network and tissue structure and/or realistic description of oxygen transport have not accounted for flow regulation [8-10]. The current study models oxygen transport and acute flow regulation in an explicit representation of a retinal network obtained from confocal microscopy images.

Figure 1.

Summary of previous mathematical models of the retina that have included some of the following hemodynamic elements: oxygen transport, acute blood flow regulation, and vessel heterogeneity. The current study combines all three in a model of the retinal microcirculation.

Previous modeling work [14, 15] demonstrated that mechanisms of flow regulation are inherently different in a heterogeneous vascular network than in a uniform network representation. The present study establishes a framework to investigate blood flow regulation and oxygenation in a non-uniform retinal microvasculature. Thus, this model fills a major void by providing an accurate depiction of oxygen delivery to retinal tissue based on flow regulation principles in a realistic network structure.

The model also predicts the role and relative importance of myogenic, shear-dependent, and metabolic response mechanisms in maintaining adequate oxygenation under a range of metabolic and flow regulation conditions. Specifically, for a range of varying levels of tissue oxygen demand, the impact of the myogenic response is examined, and the effectiveness of a range of metabolic responses is explored. Ultimately, by demonstrating the importance of various flow regulation mechanisms in maintaining tissue oxygenation in a realistic, retinal microvascular network with non-uniform structure, this model will have important translational applications in a mechanistic understanding of the origins of flow impairments, structural changes, and glaucomatous vision loss.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Network description

A previous study [9] established a heterogeneous vascular network model of the mouse retina. The positions, diameter, lengths, and connections of the retinal arterioles and venules were based on confocal microscopy images obtained by Ganesan et al. [16]. A capillary network was also defined (as in Ganesan et al. [17]) based on capillary density measurements in retinal tissue. The confocal microscopy images revealed that the retinal arteriolar network of the mouse contains 6 main branches fed by the central retinal artery, and that each of these branches feeds a non-uniform distribution of 4-5 orders of downstream arterioles of various lengths and diameters before reaching a terminal arteriole (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Heterogeneous arteriolar network in the mouse retina (as defined in [9]).

The present study adds a flow regulation component to the heterogeneous arteriolar network model of oxygen transport described in Fry et al. [9]. Diameters, lengths, and positions of vessels in the arteriolar network are taken directly from Fry et al. [9]; all values are reproduced in Table 1 and correspond to reference (control) state conditions. Because the capillary network in [9] was generated with averaged parameters, it produced a large homogeneous network structure that vastly increased computation time and lacked the realistic heterogeneity obtained from the confocal images that produced the arteriolar network. Thus, the capillary network was not included in this study, to focus on the effects of the explicit heterogeneous structure of the arteriolar network on flow regulation.

Table 1.

Order, initial (reference) diameter, and quantity of arterioles in the vascular network.

| Network | Order | Diameter (μm) | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Artery 1 | 1 | 5.75 | 61 |

| 2 | 7.71 | 32 | |

| 3 | 10.28 | 15 | |

| 4 | 14.42 | 6 | |

| 5 | 21.16 | 4 | |

| Artery 2 | 1 | 5.75 | 221 |

| 2 | 7.94 | 75 | |

| 3 | 11.54 | 25 | |

| 4 | 18.86 | 10 | |

| 5 | 30.42 | 7 | |

| Artery 3 | 1 | 5.75 | 136 |

| 2 | 7.87 | 48 | |

| 3 | 12.18 | 12 | |

| 4 | 17.98 | 9 | |

| 5 | 26.84 | 6 | |

| Artery 4 | 1 | 5.75 | 126 |

| 2 | 7.79 | 39 | |

| 3 | 11.65 | 14 | |

| 4 | 22.91 | 7 | |

| Artery 5 | 1 | 5.75 | 102 |

| 2 | 8.03 | 48 | |

| 3 | 11.47 | 12 | |

| 4 | 16.01 | 9 | |

| 5 | 24.02 | 6 | |

| Artery 6 | 1 | 5.75 | 147 |

| 2 | 8.01 | 69 | |

| 3 | 11.05 | 13 | |

| 4 | 19.56 | 4 | |

| 5 | 28.48 | 4 |

2.2. Blood flow

The vascular network is represented as a directed graph where each edge corresponds to a blood vessel segment with a specific diameter and length. Flow through each vessel is driven by pressure and follows Poiseuille’s Law: , where Q is the flow rate in an individual vessel, ΔP is the pressure drop along the vessel, D is the vessel diameter, L is the length of the vessel, and μ is the apparent viscosity, which is assumed to depend on vessel diameter and hematocrit (HD), as described in [18, 19]:

| (1) |

where

and

Flows, pressures, hematocrits, and apparent viscosities are calculated for each vessel segment of the network using an iterative scheme of two parts (described in detail in Fry et al. [9]): (1) Inflow and outflow pressure for the network are specified (inflow pressure is 40 mmHg and outflow pressure is 24 mmHg), and the conservation of flow yields a system of linear equations where the unknowns are the pressures at each node; the system is solved using successive over-relaxation to obtain pressures at each node, and flows are also calculated (assuming constant viscosity); (2) Hematocrit and apparent viscosity are calculated in each segment using the flows and pressures found in part (1) and assuming conservation of red blood cell flow rate and plasma flow rate at each node. The two schemes are alternately applied until convergence. These blood flow rates and pressures are calculated throughout the network initially using the measured vessel diameters from Table 1. Subsequently, they are re-calculated throughout the flow regulation procedure (see Section 2.4) every time a vessel diameter is changed.

2.3. Green’s function model (O2 transport)

In a heterogeneous network, oxygen is delivered to tissue via multiple vessels, and thus a simplified oxygen transport model (such as a Krogh-cylinder model) may not adequately describe the distribution of tissue partial pressure of oxygen (PO2). In particular, simplified models have been shown to underestimate the degree of hypoxia in a tissue bed [20, 21]. In this study, a more realistic transport model (called the Green’s function model) is used which allows for the diffusive exchange of oxygen among the tissue and all vessels in the network.

To describe the steady-state diffusion of oxygen in the tissue, the following governing equation is used:

| (2) |

where PO2 is the partial pressure of O2, Ddiff is the diffusion coefficient, α is the solubility of O2 in tissue, and M(PO2) is the O2 consumption rate in the tissue. The oxygen consumption rate in tissue is assumed to depend on PO2 as follows:

| (3) |

where M0 is the maximum tissue oxygen demand and P0 is the PO2 at which the consumption rate is half-maximal. Ddiffα is set to 6 × 10−10 cm3 O2/cm/s/mmHg, and P0 is set to 10 mmHg [22], M0 is varied in this study between 1 cm3 O2/100 cm3/min (baseline) and 4 cm3 O2/100 cm3/min.

To solve Equation 2, a Green’s function method [20] is used where the vessels are represented as discrete oxygen sources and the tissue points are represented as discrete oxygen sinks. The tissue PO2 is then determined as the superposition of the oxygen fields resulting from the sources and sinks. This method takes into account diffusive interactions among all tissue and vessels in the network. In addition, the method is computationally efficient, since the number of unknowns needed to compute the oxygen field in the problem is reduced compared to other approaches and much of the computation can be parallelized.

Convective oxygen transport in the blood is also simulated, including the nonlinear binding of oxygen to hemoglobin. Specifically, the convective O2 transport rate along a vessel segment is given by

| (4) |

where Q is the blood flow rate, HD is the discharge hematocrit, C0 is the concentration of hemoglobin-bound oxygen in a fully-saturated red blood cell, Pb is the blood PO2, αb is the solubility of oxygen in blood, and S(Pb) is the oxyhemoglobin saturation.

It is assumed that the oxyhemoglobin saturation is related to blood PO2 by a Hill equation:

| (5) |

where P50 = 41.5 mmHg and n = 3.5 for mice [23]. By conservation of oxygen, in each vessel segment,

| (6) |

where s is the distance along the segment, and qv(s) is the rate of diffusive O2 efflux per unit vessel length. To calculate the source and sink strengths in the Green’s function method, it is assumed that both the PO2 and the O2 flux at the blood-tissue interface are continuous. This gives

| (7) |

where rv is the vessel radius, Pv is the tissue PO2 at the interface with the blood vessel, r is the distance from the center of the vessel, and θ is the angle around the vessel circumference [20]. To represent intravascular resistance to radial oxygen diffusion, it is assumed that Pv(s) = Pb(s) – Kqv(s), where K is a constant that depends on the vessel diameter [24, 25].

2.4. Blood flow regulation

A previous model of oxygen transport in the retina [9] is extended here to include flow regulation in response to changes in pressure, shear stress, and oxygen demand. Although the current study focuses on myogenic (pressure), shear, and metabolic responses, the model provides a framework to which additional regulatory mechanisms could be added, such as neurovascular coupling (which has been identified as an important contributor to flow regulation in the retina). The total circumferential tension (T) developed in a vessel wall to balance the transmural pressure across the vessel wall is defined via the Law of Laplace:

| (8) |

As established in previous wall mechanics models [26, 27], this tension can be modeled as the sum of passive tension (Tpass) and active tension () to yield total tension (Ttotal):

| (9) |

Passive tension (Tpass, Eq. 10) is generated from the structural components of the vessel wall and is modeled as an exponential function of vessel diameter (D), where D0 represents the passive diameter of the vessels at 100 mmHg. The value of D0 can be obtained from Eq. 10 by setting D = D0 and P = 100 mmHg; namely, .

| (10) |

Active tension is generated from the contraction of smooth muscle cells and is modeled as the product of the maximally active tension (, Eq. 11) that a muscle can generate (assumed to be a Gaussian function of diameter) and the vascular smooth muscle activation or tone (A).

| (11) |

Vascular smooth muscle activation is modeled using a sigmoidal function of a stimulus function that varies between 0 and 1 (Atotal, Eq. 12) and depends on a stimulus for tone (Stone, Eq. 13), which is modeled as a linear combination of the myogenic (pressure) response, shear stress response, and conducted metabolic response.

| (12) |

| (13) |

where T is defined in Eq. 8, wall shear stress is a function of diameter and flow (Q) and is given by and and Smeta is described below.

The myogenic response (CmyoTtotal) is the intrinsic ability of the vasculature to constrict as pressure is increased. An increase in wall shear stress (Cshearτwall) that results from an increase in flow (Q) causes vasodilation (decreased tone). The metabolic signal (CmetaSmeta) is implemented as a wall-derived signal that reflects the oxygen deficit along the network. The final term of Stone is a constant () that accounts for all other mechanisms that affect smooth muscle tone but that are not explicitly modeled via mechanistic descriptions in this study. In the reference (control) state, all arteriolar diameters are given by the values obtained from the confocal microscopy images (see Table 1). Activation is assumed to be 0.5 in each vessel in the control state (i.e., 50% activation), which allows for the greatest dilation or constriction of vessels outside of control conditions. The constant is chosen so that Stone = 0 and thus activation is 0.5 in the control state. Following a simulated change in tissue oxygen demand, the steady state values of the arteriolar diameters (Di) and activation levels (Ai) are then determined by integrating the following system of differential equations:

| (14) |

| (15) |

At each time step, as the diameters change, flows, pressures, and oxygen levels are recalculated using the procedures from Section 2.2 and Section 2.3.

Parameter values for equations 1-15 are listed in Table 3 along with their source. A limitation of this study is that the parameters are taken from a variety of sources that represent multiple species and tissue types; however, several parameters are diameter dependent and thus can be applied directly to the mouse retina. Additionally, many parameters represent blood characteristics that are assumed to be similar across species. A few parameters are calculated or estimated; for example, Cmeta is chosen in order to yield similar results from a wall-derived signal as was obtained previously for an ATP-dependent metabolic signal [5]. The notation of the parameters (e.g., the use of primes in the superscripts) is consistent with notation from the previous models upon which this study is based and simply denote different parameter names.

Table 3.

Parameter values for O2 transport, conducted metabolic response, and wall tension

| Description | Parameter | Value | Unit | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxygen capacity of RBCs | C0 | 0.5 | cm3 O2/cm3 | [28] |

| Inflow Discharge hematocrit | HD | 0.4 | - | [29] |

| Inflow PO2 of blood | Pb | 84.4 | mmHg | [9] |

| Krogh diffusion coefficient | Ddiffα | 6 x 10−10 | cm3 O2/cm/s/mmHg | [30, 31] |

| Solubility of oxygen in blood | αb | 3.1x10−5 | cm3 O2/cm3/mmHg | [32] |

| Intravascular resistance | K | 0.730-2.45 | mmHg·μm·s/μm3 O2 | [25] |

| Oxygen demand | M0 | 1 – 4 | cm3 O2/100 cm3/min | varied |

| Michaelis constant for O2 consumption | P0 | 10 | mmHg | [22] |

| Constant conducted wall signal | S* | 0-0.1 | - | varied |

| Length constant | L0 | 1 | cm | [5] |

| Time constant for diameter | τd | 1 | s | [33] |

| Time constant for activation | τa | 60 | s | [34] |

| VSM activation sensitivity | Cmyo | 1.37/D0 | cm/dyn | [14] |

| VSM shear stress sensitivity | Cshear | 0.0258 | cm2/dyn | [5] |

| VSM metabolic sensitivity | Cmeta | 1000 | 1/μM/cm | [14] |

| VSM constant | C’’tone | 0.592 −10.5 | - | calculated |

| Passive tension strength | Cpass | 5.67·D0 | dyn/cm | [14] |

| Passive tension sensitivity | C’pass | −0.0270·D0 + 12.5 | - | [14] |

| Max active peak tension | Cact | 1.30·D01.48 | dyn/cm | [14] |

| Max active length dependence | C’act | −0.00146·D0 + 1.13 | - | [14] |

| Max active tension range | C”act | −0.00146·D0 + 0.308 | - | [14] |

| Passive reference diameter | D0 | 13.2 to 41.4 | μm | calculated |

To compute the metabolic response (Smeta) in Eq. 13, an averaged value of the signal generated along the length of the vessel is used. The value of Smeta for a vessel results from two components: (i) the signal from the outflow node of the vessel (Smeta,out), exponentially decayed along the length of the vessel; and (ii) the local signal rate (Sloc) generated at every point along the vessel, and exponentially decayed along the remaining length of the vessel. Thus, Smeta can be computed for a particular vessel as:

| (16) |

where L is the length of the vessel and L0 is the length constant for decay (assumed here to be L0 = 1 cm). The metabolic signal generated at each point along the vessel (Sloc) is given in Eq. 17. The signal represents the local oxygen deficit and is inversely related to the local PO2. As shown in Eq. 17, the signal is also proportional to the difference between the oxygen demand (M0) and the oxygen consumption rate (M(PO2)).

| (17) |

In a full microvascular network that includes the downstream capillaries and venules, metabolic responses would be generated by all vessels and conducted upstream to influence arteriolar tone. In such a network, the outflowing nodes of the full network would be assigned a metabolic response signal value (Smeta,out) of 0. However, since the outflowing nodes of the network in this study are arterioles (which in reality would be connected to downstream capillaries that generate conducted responses), the outflowing arteriolar nodes should be assigned a nonzero value of Smeta,out. Thus, the effect of assigning different values of Smeta,out to the outflow arteriolar nodes is investigated in this study. Three cases are considered: (1) Smeta,out = 0 (i.e., no downstream conducted response); (2) Smeta,out = S*, where S* is a constant value (i.e., a constant downstream conducted response at each arteriolar outflowing node); and (3) Smeta,out = S*nbc,out(Qi/Qtot), where nbc,out is the total number of outflowing arteriolar nodes, Qi is the flow rate in the ith outflow vessel, and Qtot is the total flow rate in the network (i.e., a conducted response at each arteriolar outflowing node weighted by the flow rate in the vessel). Simulations are run for a range of tissue O2 demand under varying blood flow regulation conditions. Blood and tissue PO2 is predicted by the model for the arteriolar network.

3. Results

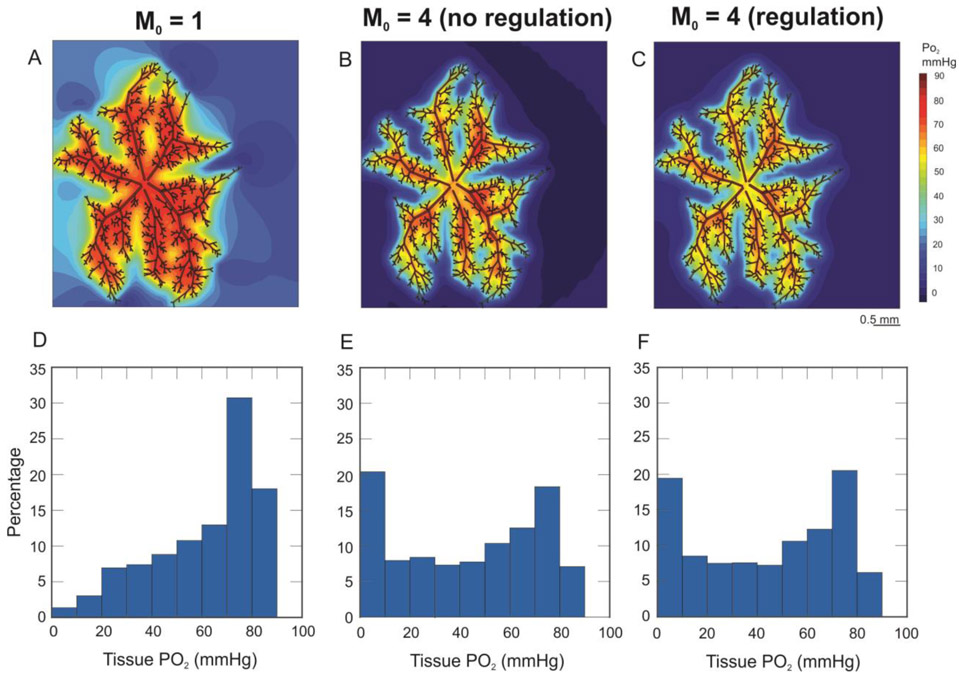

Figure 3 shows model predicted levels of tissue PO2 for low oxygen demand (M0 = 1 cm3 O2/100 cm3/min, panels A and D) and high oxygen demand (M0 = 4 cm3 O2/100 cm3/min, panels B, C, E, and F). The metabolic response is absent in panels B and E and present in panels C and F. Given that the incoming blood to the arteriolar retinal circulation is assumed to be well-oxygenated, the PO2 in some portions of the network is predicted to be relatively high; however, the average tissue PO2 levels predicted by the model vary between 42.62 mmHg and 59.73 mmHg (depending on assumed tissue oxygen demand) and are thus in the range of experimental studies of the superficial layer of the retina [35-37]. The contour plots in panels A-C and the histograms in panels D-F indicate that a fourfold increase in tissue oxygen demand leads to large reductions in tissue PO2. Panels E and F indicate that inclusion of the metabolic regulation response leads to a moderate decrease in the fraction of tissue PO2 < 10 mmHg.

Figure 3.

Contour plots and histograms of predicted PO2 levels in the arteriolar network and surrounding tissue for low O2 demand (M0 = 1 cm3 O2/100 cm3/min, panels A and D), high O2 demand with no metabolic response (M0 = 4 cm3 O2/100 cm3/min, panels B and E), and high O2 demand with the metabolic response included (M0 = 4 cm3 O2/100 cm3/min, panels C and F).

Figures 4A and 4B give the model-predicted average tissue PO2 (reported as the integral mean of the predicted PO2 over the tissue domain) and fraction of tissue < 5 mmHg, respectively, for M0 values of 1, 2, and 4 cm3 O2/100 cm3/min with the following combinations of regulatory mechanisms: (i) all responses are on (All on); (ii) shear and metabolic on, but myogenic off (No Myo); (iii) myogenic on, but shear and metabolic off (Only Myo); and (iv) all responses off (All off). In general, as in Figure 3, the model predicts that an increase in tissue oxygen demand leads to a decrease in average tissue PO2 and an increase in the fraction of tissue < 5 mmHg. A cutoff value of 5 mmHg is chosen to represent hypoxia in the arteriolar network (rather than 1 mmHg) because arterioles are fairly well-oxygenated. Since the arterioles supply downstream tissue, any pathway in the arteriolar network with PO2 less than 5 mmHg will likely supply areas downstream at risk of hypoxia < 1 mmHg. Figure 4A indicates that for varying levels of tissue O2 demand, the difference in average tissue PO2 is negligible between the cases with and without blood flow regulation included. However, when M0 = 2 cm3 O2/100 cm3/min, the predicted average tissue PO2 is considerably lower when only the myogenic response is on. Similarly, when M0 = 2 cm3 O2/100 cm3/min, the highest predicted fraction of tissue < 5 mmHg occurs when only the myogenic response is on. Figure 4B indicates that for M0 = 2 cm3 O2/100 cm3/min and M0 = 4 cm3 O2/100 cm3/min, the lowest predicted fraction of tissue < 5 mmHg occurs when only the metabolic and shear responses are on (i.e., when the myogenic response is off).

Figure 4.

A. Average tissue PO2 (in mmHg) vs. tissue oxygen demand (M0, in cm3 O2/100 cm3/min), for the following four cases: no regulatory response (All off, purple), only the myogenic response (Only Myo, yellow), all responses except the myogenic response (No Myo, red), and all regulatory responses (All on, blue). B. Tissue hypoxic fraction vs. tissue oxygen demand for the same four cases defined in panel A.

To investigate the effect of the myogenic response on metabolic flow regulation, the weight of the metabolic response (Cmeta) is varied in the presence or absence of the myogenic response. Figure 5 shows the predicted difference in average tissue PO2 between the case of all responses active (i.e., myogenic, shear, and metabolic responses included, All on) and the case of an inactive myogenic response (i.e., only shear and metabolic responses included, No Myo) for two different values of Cmeta (assuming M0 = 2 cm3 O2/100 cm3/min). At the baseline value of Cmeta, the predicted difference between the two cases is negligible (0.16 mmHg); however, when the assumed contribution of the metabolic response was reduced by 90%, the difference between the two cases is much larger (3.31 mmHg), suggesting that a larger metabolic response helps to dampen a possibly negative contribution to flow regulation by the myogenic response.

Figure 5.

Average tissue PO2 difference between the case of all responses active (i.e., myogenic, shear, and metabolic responses included, All on) and the case of an inactive myogenic response (i.e., only shear and metabolic responses included, No Myo). Left: metabolic response strength, Cmeta, is set to 10% of baseline. Right: Cmeta is at the baseline level. Here, M0 = 2 cm3 O2/100 cm3/min.

As indicated in the Methods, conducted metabolic signals are produced by the vessels in the network in response to local PO2 levels and generate a metabolic flow regulation response. The response generated by each vessel is a function of both the partial pressure of oxygen at the vessel (Sloc) and the signal conducted from downstream vessels (Smeta,out). To investigate the effect of downstream conducted signals on blood flow regulation in the arterioles, simulations were run for three choices of Smeta,out to the outflowing arteriolar nodes: (1) zero at all outflows; (2) a constant value (S*) at all outflows; and (3) a flow-weighted value at all outflows.

Figures 6A and 6B show predicted average tissue PO2 and fraction of tissue < 5 mmHg for M0 values of 1, 2, and 4 cm3 O2/100 cm3/min for these three different prescribed values of downstream conducted response signal (Smeta,out,i) at outflowing vessels i: Smeta,out,i = 0 (no downstream response); Smeta,out,i = S* (constant downstream response in each vessel); or Smeta,out,i = S*nbcoutQi/Qtot (flow-weighted downstream response in each vessel). For all values of M0 the predicted average tissue PO2 is highest (and predicted tissue hypoxic fraction is lowest) when the downstream signal at each outflowing vessel is weighted by the flow rate in the vessel.

Figure 6.

Panels A and B: Plots of average tissue PO2 (in mmHg) and tissue hypoxic fraction vs. oxygen demand (in cm3 O2/100 cm3/min), for the following three cases: no downstream metabolic signal (S* = 0, blue), fixed downstream metabolic signal (S* = 0.01, red), and flow-weighted downstream metabolic signal (yellow). Panels C and D: Plots of average tissue PO2 and tissue hypoxic fraction vs. weight of downstream metabolic signal (S*), for the fixed signal (blue) and flow-weighted signal (red) cases (with M0 = 4 cm3 O2/100 cm3/min). Points a, b, and c are labeled to illustrate the impact of a flow-weighted signal compared to an increase in signal strength (see text).

Figures 6C and 6D show predicted average tissue PO2 and fraction of tissue < 5 mmHg for S* values of 0.001, 0.01, and 0.1, assuming the signal is fixed or flow-weighted. As S* is increased, there is a moderate increase in the average tissue PO2 and moderate decrease in tissue hypoxic fraction in all cases. Interestingly, the model predicts that it is always better to have a flow-weighted signal than a fixed signal for effective oxygenation in a heterogeneous network. Specifically, for all values of S*, the predicted average tissue PO2 is higher and predicted tissue hypoxic fraction is lower if a flow-weighted signal is used. For some values of S*, it is even better to have a flow-weighted signal than a larger fixed signal; to see this more clearly, notice that when S* = 0.01, there is a much greater increase in average PO2 between the fixed and flow-weighted prediction (points (a) and (b) in Figure 6C) than for an increase in the fixed signal by a factor of ten (points (a) and (c) in Figure 6C).

4. Discussion

A critical void exists in understanding the interplay of retinal blood flow and metabolism, tissue structure, and function. This lack of knowledge has significant impact in ocular pathologies such as glaucoma where retinal homeostasis and ganglion cell preservation are intertwined. Difficulty in imaging internal eye structures has been a prohibitive obstacle to advancing disease management, and mathematical modeling represents a novel approach to revealing the mechanism(s) involved in glaucoma pathophysiology. In working to solve this enigma, the present study provides a comprehensive model of the retina that combines oxygen transport and flow regulation within a heterogeneous description of the retinal arteriolar network.

The model predicts a large spread in tissue PO2, and a shifted PO2 distribution, when the tissue oxygen demand is increased (Fig. 3) both with and without blood flow regulation included. It might seem erroneous that panels E and F of Figure 3 predict only a minor change in the tissue PO2 distribution with the inclusion of the metabolic regulation response. However, this is expected, since the current model only accounts for the arteriolar network, where all PO2 levels are relatively high compared to the rest of the microcirculation. Since the metabolic response is assumed to be inversely related to the PO2, these arteriolar PO2 levels do not elicit major metabolic regulation responses. And, it is important to note that Figure 3 is generated assuming no downstream metabolic signal (Smeta,out,i = 0). Inclusion in the model of downstream microvessels (either explicitly or implicitly, as in Figure 6) will lead to the generation of metabolic signals conducted upstream to the terminal arterioles that should elicit larger diameter and flow changes than were simulated in this study.

A useful feature of mathematical models is the ability to simulate different combinations of active or inactive blood flow regulation mechanisms. Figure 4A shows that the model predicts a lower average tissue PO2 for moderate tissue O2 demand (M0 = 2 cm3 O2/100 cm3/min) when only the myogenic response is included in the model, compared to the case when no regulation responses are included. Further, Figure 4B shows that the model predicts a lower fraction of tissue < 5 mmHg for M0 = 2 cm3 O2/100 cm3/min and M0 = 4 cm3 O2/100 cm3/min when the myogenic response is turned off, compared to when it is turned on. Together, Figures 4A and 4B indicate that the myogenic response may have a detrimental effect on blood flow regulation in response to changing oxygen demand.

The effects of the myogenic response on metabolic flow regulation were investigated further by simulating the cases of an active or inactive myogenic response while also varying the strength of the metabolic response. Figure 5 indicates that a smaller strength of the metabolic response (Cmeta) leads to a larger difference between the cases with and without the myogenic response included. This prediction seems to indicate that a larger contribution from the metabolic response helps to blunt possible detrimental effects of the myogenic response. The vascular health and autoregulatory ability of a given person have been shown to vary greatly and be reduced in glaucoma patients specifically [5, 38-40]. Therefore, the ability (or lack thereof) of the metabolic response to mitigate myogenic involvement is a novel and highly impactful observation that may explain, in part, the individual variation in OAG disease susceptibility. In the future, neurovascular coupling mechanisms that mediate the functional hyperemia response in the retina [41] should be added to the model to provide an even more complete description of retinal flow regulation.

A current limitation of the model is that the full retinal microcirculation is not being represented, only the arteriolar network. In a full arteriovenous network, the outflow nodes would correspond to the end of the network. In this study, the outflow nodes correspond to terminal arterioles, with an implied downstream set of capillaries and venules. In a full network, the downstream capillaries and venules would generate a metabolic signal that propagates upstream to the arterioles. In an attempt to capture this effect in the current model construct, three different metabolic signals are simulated at the terminal arterioles. Case (1) assumes that the outflow node values of Smeta,out are all zero. This case essentially implies that the arteriolar network exists in isolation. This is a very unlikely situation, given that the arteriolar network comprises only the beginning of a full microvascular network. However, given a lack of downstream data, this case was used as the default. Case (2) assumes that the outflow node values of Smeta,out are all nonzero and constant. This case implies that a nonzero signal is being generated downstream and conducted upstream to the arteriolar outflows. This case is more realistic than Case (1) since it is very reasonable to assume that there should be a nonzero signal propagated upstream. However, given the lack of data on the strength of this signal, different values of Smeta,out were simulated. Not surprisingly, as Smeta,out was increased, moderate increases in average tissue PO2 and decreases in tissue hypoxic fraction were predicted (Fig. 6C and 6D). Case (3) assumes that the signal is flow-dependent so that outflow vessel nodes with larger flow rates receive larger signals. The justification for this is that outflowing vessels with larger flow rates supply larger downstream areas, which should produce larger signals. Results from simulations using a flow-weighted signal value (Fig. 6) predict that a flow-weighted signal produces higher average tissue PO2 and lower tissue hypoxic fraction throughout the network.

Importantly, the predicted improvement in oxygenation using a flow-weighted signal instead of a constant signal is often greater than the predicted improvement in oxygenation with an increase in the value of the signal. That is, the model predicts that, for some values of S*, the heterogeneity of the signal is at least as, if not more, important as the strength of the signal. This indicates that the heterogeneity of the downstream conducted responses serves to regulate flow better than a constant conducted response, further supporting the importance of considering the non-uniform structure of the retinal arteriolar microvasculature when trying to understand how and to what extent blood flow regulation is working in the microcirculation. This finding has significant implications for ophthalmic pathologies such as glaucoma where retinal metabolism and homeostasis are determinants of ganglion cell health and vision preservation.

A theoretical modeling approach has the significant advantage of encapsulating all retinal regions compared to singular zone assessment from traditional modalities including metabolic probes. The selective placement of probes only reveals PO2 within a defined segment, allowing hidden pockets of hypoxia to remain unseen. Importantly, glaucomatous changes to structure and ganglion cell death occur non-uniformly, often within isolated segments while other tissue remains unaltered. This study overcomes this significant assessment limitation by providing a comprehensive model of retinal blood flow regulation and oxygen status across the entire heterogeneous retinal arteriolar circuit. Model results give insight into the spatial distribution of oxygenation at a particular depth, rather than simply an average value provided by a probe that may not capture the spread of PO2 levels at that depth. The ability to provide oxygen status across the retina without extrapolating singular tissue assessment to the whole network is highly impactful in understanding slow moving chronic disturbances to retina homeostasis.

Ultimately, this model provides an important step in predicting oxygen transport and blood flow regulation in a heterogeneous description of the retinal microvasculature. To relate the predictions of the model more closely to outcomes in humans, the arteriolar network will be adapted to human parameters and structure (e.g., humans have 4 main branches off of the central retinal artery, compared to 6 in the mouse). In addition, inclusion of a more explicit representation of the downstream microvessels will allow for predictions of tissue PO2 downstream of the arterioles, and, more importantly, provide more accurate predictions of downstream conducted metabolic signals (including effects of the downstream PO2 distribution). Overall, results from this mathematical model have significant implications for ocular functionality and pathologies involving retinal hemodynamics and metabolism.

Table 2.

Variable names, descriptions, and units for the model

| Description | Variable | Unit | Initial value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vessel diameter | D | μm | See Table 1 |

| Vascular smooth muscle (VSM) activation | A | - | 0.5 |

Highlights.

Retinal flow regulation and O2 transport are modeled in a realistic vascular network.

Flow regulation is modeled in response to pressure, shear stress, and oxygen demand.

Simulations predict tissue PO2 under varying blood flow regulation conditions.

Model predicts myogenic response has detrimental effects on metabolic flow regulation.

Heterogeneous metabolic responses better regulate blood flow than uniform responses.

Acknowledgments

AH and BS acknowledge Research to Prevent Blindness.

Funding

JA gratefully acknowledges NSF DMS-1654019 and NSF DMS-1852146. JA, BF, AH, and BS gratefully acknowledge NIH R01EY030851.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author Disclosure Statement

There are no conflicts of interest. Dr. Alon Harris would like to disclose that he receives remuneration from AdOM for serving as a consultant and board member, and from Thea for a speaking engagement. Dr. Harris also holds an ownership interest in AdOM, Luseed, Oxymap, and QuLent.

References

- 1.Harris A, et al. , Ocular blood flow as a clinical observation: Value, limitations and data analysis. Prog Retin Eye Res, 2020: p. 100841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weinreb RN, Harris A, Ocular blood flow in glaucoma, in World Glaucoma Association Consensus Series. 2009, Kugler Publications: Amsterdam, the Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hwang JC, et al. , Relationship among visual field, blood flow, and neural structure measurements in glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 2012. 53(6): p. 3020–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yarmohammadi A, et al. , Relationship between Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography Vessel Density and Severity of Visual Field Loss in Glaucoma. Ophthalmology, 2016. 123(12): p. 2498–2508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arciero J, et al. , Theoretical analysis of vascular regulatory mechanisms contributing to retinal blood flow autoregulation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 2013. 54(8): p. 5584–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guidoboni G, et al. , Mathematical modeling approaches in the study of glaucoma disparities among people of African and European descents. J Coupled Syst Multiscale Dyn, 2013. 1(1): p. 1–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guidoboni G, et al. , Intraocular pressure, blood pressure, and retinal blood flow autoregulation: a mathematical model to clarify their relationship and clinical relevance. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 2014. 55(7): p. 4105–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Causin P, et al. , Blood flow mechanics and oxygen transport and delivery in the retinal microcirculation: multiscale mathematical modeling and numerical simulation. Biomech Model Mechanobiol, 2016. 15(3): p. 525–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fry BC, et al. , Predicting retinal tissue oxygenation using an image-based theoretical model. Math Biosci, 2018. 305: p. 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu D, et al. , Computational analysis of oxygen transport in the retinal arterial network. Curr Eye Res, 2009. 34(11): p. 945–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McDougall SR, et al. , A hybrid discrete-continuum mathematical model of pattern prediction in the developing retinal vasculature. Bull Math Biol, 2012. 74(10): p. 2272–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Watson MG, et al. , Dynamics of angiogenesis during murine retinal development: a coupled in vivo and in silico study. J R Soc Interface, 2012. 9(74): p. 2351–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carichino L, et al. , A theoretical investigation of the increase in venous oxygen saturation levels in glaucoma patients. IOVS, 2015. 56(7). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fry BC, Roy TK, and Secomb TW, Capillary recruitment in a theoretical model for blood flow regulation in heterogeneous microvessel networks. Physiol Rep, 2013. 1(3): p. e00050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roy TK, Pries AR, and T.W. Secomb, Theoretical comparison of wall-derived and erythrocyte-derived mechanisms for metabolic flow regulation in heterogeneous microvascular networks. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol, 2012. 302(10): p. H1945–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ganesan P, He S, and Xu H, Development of an image-based network model of retinal vasculature. Ann Biomed Eng, 2010. 38(4): p. 1566–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ganesan P, He S, and Xu H, Development of an image-based model for capillary vasculature of retina. Comput Methods Programs Biomed, 2011. 102(1): p. 35–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pries AR, Secomb TW, Blood flow in microvascular networks, in Handbook of Physiology: Section 2, The Cardiovascular System, vol. IV, Mircrocirculation, Tuma RF, Duran WN, Ley K, Editor. 2008, Academic Press: San Diego, CA: p. 3–36. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pries AR, et al. , Blood flow in microvascular networks. Experiments and simulation. Circ Res, 1990. 67(4): p. 826–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Secomb TW, et al. , Green's function methods for analysis of oxygen delivery to tissue by microvascular networks. Ann Biomed Eng, 2004. 32(11): p. 1519–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Secomb TW, et al. , Analysis of oxygen transport to tumor tissue by microvascular networks. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 1993. 25(3): p. 481–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Golub AS and Pittman RN, Oxygen dependence of respiration in rat spinotrapezius muscle in situ. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol, 2012. 303(1): p. H47–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gray LH and Steadman JM, Determination of the Oxyhaemoglobin Dissociation Curves for Mouse and Rat Blood. J Physiol, 1964. 175: p. 161–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Secomb TW and Hsu R, Simulation of O2 transport in skeletal muscle: diffusive exchange between arterioles and capillaries. Am J Physiol, 1994. 267(3 Pt 2): p. H1214–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hellums JD, et al. , Simulation of intraluminal gas transport processes in the microcirculation. Ann Biomed Eng, 1996. 24(1): p. 1–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carlson BE, Arciero JC, and Secomb TW, Theoretical model of blood flow autoregulation: roles of myogenic, shear-dependent, and metabolic responses. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol, 2008. 295(4): p. H1572–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arciero JC, Carlson BE, and Secomb TW, Theoretical model of metabolic blood flow regulation: roles of ATP release by red blood cells and conducted responses. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol, 2008. 295(4): p. H1562–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McGuire BJ and Secomb TW, A theoretical model for oxygen transport in skeletal muscle under conditions of high oxygen demand. J Appl Physiol (1985), 2001. 91(5): p. 2255–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pries AR, Secomb TW, and Gaehtgens P, Biophysical aspects of blood flow in the microvasculature. Cardiovasc Res, 1996. 32(4): p. 654–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ellsworth ML, Popel AS, and Pittman RN, Assessment and impact of heterogeneities of convective oxygen transport parameters in capillaries of striated muscle: experimental and theoretical. Microvasc Res, 1988. 35(3): p. 341–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bentley TB, Meng H, and Pittman RN, Temperature dependence of oxygen diffusion and consumption in mammalian striated muscle. Am J Physiol, 1993. 264(6 Pt 2): p. H1825–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Celaya-Alcala JT, et al. , Simulation of oxygen transport and estimation of tissue perfusion in extensive microvascular networks: Application to cerebral cortex. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab, 2020: p. 271678X20927100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johnson PC, The myogenic response, in Handbook of Physiology. The Cardiovascular System. Vascular Smooth Muscle 1980, Am. Physiol. Soc: Bethesda, MD: p. 409–442. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Falcone JC, Davis MJ, and Meininger GA, Endothelial independence of myogenic response in isolated skeletal muscle arterioles. Am J Physiol, 1991. 260(1 Pt 2): p. H130–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yu DY and Cringle SJ, Oxygen distribution in the mouse retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 2006. 47(3): p. 1109–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Linsenmeier RA and Zhang HF, Retinal oxygen: from animals to humans. Prog Retin Eye Res, 2017. 58: p. 115–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shonat RD and Kight AC, Oxygen tension imaging in the mouse retina. Ann Biomed Eng, 2003. 31(9): p. 1084–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Evans DW, et al. , Glaucoma patients demonstrate faulty autoregulation of ocular blood flow during posture change. Br J Ophthalmol, 1999. 83(7): p. 809–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moore D, et al. , Dysfunctional regulation of ocular blood flow: A risk factor for glaucoma? Clin Ophthalmol, 2008. 2(4): p. 849–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Prada D, et al. , Autoregulation and neurovascular coupling in the optic nerve head. Surv Ophthalmol, 2016. 61(2): p. 164–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Newman EA, Functional hyperemia and mechanisms of neurovascular coupling in the retinal vasculature. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab, 2013. 33(11): p. 1685–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]