Abstract

Background:

Combinatory intervention such as high frequency (50–100Hz) excitatory cortical stimulation (ECS) given concurrently with motor rehabilitative training (RT) improves forelimb function, except in severely impaired animals after stroke. Clinical studies suggest that low frequency (<1Hz) inhibitory (ICS) may provide an alternative approach to enhance recovery. Currently, the molecular mediators of CS-induced behavioral effects are unknown. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) has been associated with improved recovery and neural remodeling after stroke and thus may be involved in CS-induced behavioral recovery.

Objective:

To investigate whether inhibitory stimulation during RT improves functional recovery of severely impaired rats, following focal cortical ischemia and if this recovery alters BDNF expression (Study 1) and is dependent upon BDNF binding to TrkB receptors (Study 2).

Methods:

Rats underwent ECS+RT, ICS+RT, or noCS+RT treatment daily for three weeks following a unilateral ischemic lesion to the motor cortex. Electrode placement for stimulation was either placed ipsilateral (ECS) or contralateral (ICS) to the lesion. After treatment, BDNF expression was measured in cortical tissue samples (Study 1). In Study 2, the TrkB inhibitor, ANA-12, was injected prior to treatment daily for 21 days.

Results:

ICS+RT treatment significantly improved impaired forelimb recovery compared to ECS+RT and noCS+RT treatment.

Conclusion:

ICS given concurrently with rehabilitation improves motor recovery in severely impaired animals, and alters cortical BDNF expression; nevertheless, ICS mediated improvements are not dependent upon BDNF binding to TrkB. Conversely, inhibition of TrkB receptors does disrupt motor recovery in ECS+RT treated animals.

Keywords: Stroke, Inhibitory Brain Stimulation, Rehabilitation, BDNF, TrkB inhibition

INTRODUCTION

According to the American Heart Association (2009) [1], stroke is the leading cause of disability within the United States. Motor impairments are some of the most common disabilities and most persistent following stroke [2]. Recovery of motor function is heterogeneous, but several studies conclude that the more severely impaired an individual is early after stroke, the poorer their recovery is likely to be long-term [2, 3]. A promising treatment approach to enhance motor recovery is to combine physical rehabilitation with electrical or magnetic stimulation of the ipsilesional motor cortex [4, 5]. Specifically, research studies indicate that epidural excitatory cortical stimulation (ECS) combined with rehabilitative practice with the impaired limb greatly improves motor recovery compared to rehabilitation alone in primates, rats, and humans [6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14]. However, if initial impairments are severe, ECS does not further enhance motor recovery compared to rehabilitative training (RT) alone in pre-clinical stroke models [10].

Over the past decade, several studies indicate that contralesional inhibitory cortical stimulation (ICS) may be effective when ipsilesional ECS is not [15]. There is growing evidence that contralesional ICS may provide an effective alternative approach to enhance behavioral recovery and is an alternative strategy to manipulate ipsilesional excitability to improve motor outcome. Low frequency (≤1 Hz) repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) of the non-stroke cortex can induce neural inhibition and reduce spasticity and hemiparesis in chronic stroke subjects [15, 16]. Inhibiting the unaffected motor cortex using 1Hz rTMS enhances motor performance of the paretic hand in patients with subcortical chronic stroke and severe post-operative impairments [17]. Thus, it is possible that ICS over the non-stroke motor cortex combined with forelimb RT may improve recovery more effectively than ECS or RT alone when initial impairments are severe. While it is not known in these studies, and is debatable within the field, whether the high-frequency 100 Hz and slow frequency of 1 HZ produced excitatory and inhibitory neural effects, respectively, we use this nomenclature throughout the manuscript.

Despite promising studies suggesting that brain stimulation may augment rehabilitative training after stroke, the underlying molecular mechanisms are unknown. It is likely that brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) may play a key role in recovery of function following stroke and also may be involved in brain stimulation related enhancement of recovery. In clinical studies, a reduction in BDNF in the acute phase after stroke is a factor for poor prognosis in terms of functional status of patients [18]. Animal studies demonstrate that inhibition of BDNF using the injection of antisense oligodeoxynucleotides impairs functional recovery and disrupts motor cortex reorganization [19]. BDNF binding to the TrkB receptor has a synergistic role in motor learning in that the effectiveness of rehabilitation is reliant upon a certain threshold of BDNF expression [20]. Motor cortical reorganization is reliant upon TrkB’s downstream effects on synaptic plasticity, which is vital for recovery of function [21]. While there is evidence that BDNF is necessary for many forms of brain plasticity and BDNF has been strongly implicated in stroke recovery, it is not known whether BDNF is involved in CS-induced motor recovery, although some studies do suggest a role. Brain stimulation can increase activity-dependent expression of BDNF [22, 23]. Previous studies found that daily 5 Hz-rTMS for five days improves BDNF-TrkB signaling in rats by increasing the affinity of BDNF for the TrkB receptors that results in greater density of TrkB receptors within the cortex [22]. Together, these studies suggest that BDNF is an essential molecule for motor improvement following stroke, is important to rehabilitative training related motor improvements and cortical reorganization, and may be enhanced through some forms of brain stimulation.

In the following studies we compared the behavioral effects of ECS over the lesion cortex or ICS over the non-lesion cortex during RT in a rat model of stroke in which post-operative impairments were severe. To begin to uncover possible neurobiological mechanisms underlying CS related recovery of function we investigated whether brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) expression was altered after treatment (Study 1) and if BDNF binding to its tyrosine-phosphorylated (TrkB) receptor was necessary to induce motor recovery.

This study has two central aims: (Study 1) compare the effectiveness of ICS+RT, ECS+RT, and RT alone to enhance motor recovery after stroke in rats with severe impairments and (Study 2) to investigate if BDNF is a primary mediator of CS induced behavioral recovery.

METHODS

Experimental Overview

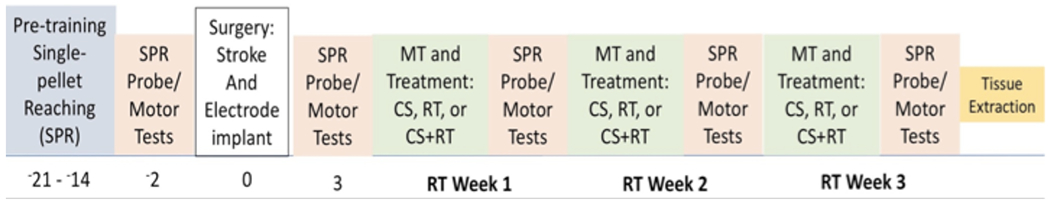

All rats were tamed by gentle handling and trained to reach with their preferred forelimb on the single pellet reaching (SPR) task until they reached a minimum criterion of 50% successful reaches (Figure 1). Ischemic lesions were induced contralateral to the preoperatively trained forelimb and electrodes were implanted according to treatment group assignment. After 3 days of recovery, all animals underwent rehabilitative training (RT), which consisted of practice with the paretic limb on the SPR task 6 days per week for 3 weeks, concurrent with treatment group stimulation protocols. After 3 weeks of treatment, animals were euthanized and tissue was collected for BDNF ELISA analysis. In study 2, we administered either ANA-12 or DMSO-Saline (vehicle) injections 36 hours post-stroke and daily 3 hours before each rehabilitation session (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Timeline of Study. Animals were trained on the SPR to criterion and then assessed using this task before surgeries. Animals received stroke induction and post-operative performance assessments began 3 days after surgery in which the SPR test was given. Animals received rehabilitation for 21 days.

Animals

In Study 1, 76 (4-9 months old, Envigo) and in Study 2, 37 (4 month old, Envigo) Long Evans male rats were housed in pairs, received water ad libitum and were kept on a 12:12 h light:dark cycle. Rats were maintained on a moderate restricted diet (15g-20g per day) to motivate performance on the reaching task. Surgeries were performed at 4 or 9 months. Animals were assigned randomly to treatment conditions with the exception that they were carefully matched for pre-surgery performance and initial severity of lesion induced impairments, assessed on the SPR task. All work was done in accordance with the Medical University of South Carolina Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines.

In study 1, animals were divided into the following three groups: 1) 100 Hz, excitatory stimulation over the stroke cortex concurrent with RT (ECS+RT n = 18), 2) 1 Hz, inhibitory stimulation over the stroke cortex concurrent with RT (ICS+RT, n = 19), 3) RT alone (NoCS+RT, n = 29). In study 1, 10 animals died during surgery or before the completion of the study.

In study 2, animals were divided into six groups: 1) excitatory stimulation + impaired forelimb RT + ANA-12 (ECS+RT+ANA-12, n=5); 2) inhibitory stimulation + impaired forelimb RT + ANA-12 injection (ICS+RT+ANA-12, n=5); 3) no stimulation+ impaired forelimb RT+ ANA-12 (NOCS+RT+ANA-12 n= 5); 4) excitatory stimulation + impaired forelimb RT + VEHICLE (ECS+RT+VEH, n=7); 5) inhibitory stimulation + impaired forelimb RT + VEHICLE injection (ICS+RT+VEH, n=5); 6) no stimulation + impaired forelimb RT + VEHICLE (NOCS+RT+VEH n= 5). In study 2, 5 animals died during surgery or before the completion of the study.

Surgical Procedure

Unilateral ischemic damage of the primary motor cortex (MC) was created by applying endothelin-1, a vasoconstricting peptide (American Peptide, Inc), to the cortical surface of the forelimb area of the sensorimotor cortex [24, 25]. Animals were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal (i.p) injection of ketamine (110 mg/kg; Labcorp, Burlington, NC) and xylazine (70mg/kg; Heartland Vet Supply, Hastings, NE). All animals received buprenorphine (0.5mg/kg S.C.; Med-Vet International, Mettawa, IL) prior to incision for pain. To induce severe reaching impairments, rats were placed in a stereotaxic apparatus, a midline incision was made and a craniotomy was performed over the motor cortex opposite the trained limb (Figure 2). Four and nine month old rats, received a craniotomy at 0.5-1.5 mm posterior and 3-4.5 mm anterior to bregma and 2.0 to 5.0 mm lateral to midline [7] and 3 or 4uL of endothelin-1 (80μM, 0.2 μg/μl in sterile saline; American Peptide, Inc) was topically applied to the exposed MC. For all surgeries, ET1 was applied at approximately 1μl/min, with a 2 min wait between each 1μl of ET-1 application [7, 10]. After the final 1ul of ET-1, the brain was left undisturbed for 10 minutes followed by electrode implantation.

Figure 2.

Electrode Placement and Cortical Punches. Strokes were induced via topical application of endothelin-1, a vasoconstricting peptide, over the motor cortex opposite the preferred reaching limb. A. Then the craniotomy was enlarged and a bipolar epidural electrode was placed over peri-injury motor cortex(eCS).Or B. Then a craniotomy was made over the forelimb area of the non-infarcted motor cortex and a bipolar epidural electrode was implanted (iCS). 3mm cortical punches medial/lateral to the stroke area were obtained. Cortical punches were obtained on the M1 area of the motor cortex. For ECS and ICS, this is where the electrode is placed.

The intention was to create motor impairments that correlated with lesion size to determine whether inhibitory stimulation would improve forelimb motor recovery in either moderately or severely impaired young adult animals. Stroke size (determined by craniotomy coordinates) was not a reliable determinant of motor impairment. Animals, despite lesion area, resulted in both severe and moderate behavioral impairments as assessed with the single pellet reaching task. Several studies have determined that lesion size and lesion severity do not always correlate, making behavioral post-stroke outcomes a more reliable predictor of functional recovery. Similar to previous studies [10], experimental lesion size differences alone do not necessarily result in quantifiable differences in reaching impairments (at least as performed in these studies). At the end of the study, treatment groups were further divided based upon forelimb impairments demonstrated on the SPR task analyzed treatment effects upon these subgroupings. An impairment score was calculated with the formula: (PostOP-PreOP)*100. Severe impairment (81-100% decrease in reaching success). Separating animals by their impairment levels based on their post-operative reaching success instead of craniotomy size and volume of ET-1 administered was determined to be a sensitive means divide animals into different levels of forelimb reaching impairments.

Each bipolar electrode consisted of 1mm wide by 3mm long platinum strips mounted on a 3mm by 3mm silicon plate (Plastics One Inc., Roanke, VA). The electrode was placed upon the dura surface of the MC and positioned in order to optimize ability to evoke contralateral motor movements.

For all ECS and NoCS groups, the initial craniotomy was enlarged ~1 mm rostrally and medially to expose ipsilesion MC. The electrode contacts were positioned parallel to midline over remaining caudal and rostral forelimb and other motor areas of the MC (Figure 2; [7, 8]). Platinum strips were oriented approximately parallel to midline (Figure 2).

Following all electrode placements, any exposed cortex was covered with a piece of gel-film. To secure the electrode to the skull, skull screws (Plastics One, Inc., Roanke, Va) were placed surrounding the craniotomy to create additional bonding surface. GC FugiCEM2 (GC America, Alsip, IL) and Dental acrylic (Wave SDI Limited Bayswater, Victoria, Australia) and dental cement (GC America, Inc., Alsip, IL) were applied to both the skull and screws. After implantation animals were sutures and then given 3ml of warm Ringers solution (s.c.) (Baxter Inc., Deerfield IL) during recovery. Animals were placed on heating pads (Sunbeam, Boca Raton, FL) after surgery and were given dampened standard food chow.

Rehabilitative Training task and Forelimb Function test

The single-pellet retrieval task (SPR) has been described in detail previously [7, 8, 26, 27] After shaping to determine limb preferences, rats were trained to reach with the preferred limb through a narrow window to retrieve a b-na flavored food pellet (45 mg, Bio-Serve, Frenchtown, NJ) from a well 1 cm from the opening.

In both studies, rats were trained to reach a limb through a narrow window, grasp a pellet, bring the pellet back into the cage and bring it to their mouths—a successful reach. Rats were evaluated for their demonstrated preferred reaching limb and then were trained, for approximately three weeks with that limb. Reaching performance was measured as the percent success of successful reaches [(total successes/total number reach attempts)*100]. Prior to surgery, animals were trained for 30 trials over 15 minutes daily, until they achieved an average of 40-60% success rate. A trial began with the placement of a banana pellet in a well and ended when the animal either grasped the pellet and brought it to their mouth for consumption (successful reach), or dropped the pellet before reaching mouth (drop), or failed to grasp the pellet by knocking the pellet off the tray or missing the pellet after five consecutive attempts (misses). After each trial, a single banana pellet was dropped into the front of the chamber to “reset” the animals reaching posture.

Post-surgery, rats were allowed to recover for three days. On post-stroke Day 4, and then weekly, impaired forelimb function was assessed in Probe Trials. Probe trials consisted assessing the average reaching success during 30 trials or 15 min of SPR. Data presented are the group mean success rates from weekly probe trials and were calculated as: (#successful pellet retrievals/# of reaches)*100.

On Post-surgery Day 5, rats practiced reaching with their impaired forelimb in the SPR task, a well-established form of rehabilitative forelimb training [28] for 6 days/week for 3 weeks. Rehabilitative training trials consisted of 60 trials or 20 minutes, which ever came first.

Stimulation Parameters

Four days after lesion induction, excitatory or inhibitory stimulation was delivered for 21 days during practice on the rehabilitation SPR task. All animals were attached to stimulator cables and placed into the reaching chambers. The stimulation groups in all studies received stimulation that was delivered at 50% of that week’s movement threshold (MT) [7, 9]. Epidural stimulation was delivered as a train of bipolar, continuous pulses at 100Hz for ECS or 1Hz for ICS groups. Electrical stimulation was delivered through bipolar strip electrodes, as described above. For the high-frequency, 100 Hz stimulation current was delivered as a train of continuous biphasic, charge balanced, and asymmetric pulses every 104 μs. Each biphasic, square pulse delivered current every 100 μs (first phase) and then the voltage was off for 9,900 μs (second phase). Stimulation amplitudes were adjusted as needed to accommodate changes in movement thresholds. NoCS rats were attached to the stimulator cables, but no current was delivered.

The intensity of current delivered during RT was set at 50% of the lowest amount of current needed to induce involuntary motor movements or the motor threshold (MT). To assess MT, animals in the ECS and ICS treatment groups were attached to electrode leads, then they were placed into a transparent cylinder and electrical current was delivered in three second trains of 1 millisecond, 100 Hz bipolar current pulses which were gradually increased by 5% increments until an involuntary movement was observed in the contralateral paw, head, or neck. The lowest current level to evoke a movement was recorded as that week’s MT. The weekly current level delivered during RT for that week was set at 50% of that week’s MT. In our hands, 1Hz bipolar current pulses could not elicit involuntary motor movements. Thus, to keep consistency and uniformity in the way motor thresholds were obtained, we set ICS current thresholds based upon the same parameters used for the ECS.

BDNF Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

In study 1, After 21 days of RT (24 days post-lesion) and within 1 hour of the last probe trial, all rats were anesthetized with an overdose of .8cc Euthasol (Virbac Solutions) (400mg/ml) and decapitated when breathing stopped. The right and left motor cortex regions were extracted and placed in vials and stored at −80 degrees C. Two cortical punches (3mm each) were obtained from each hemisphere. To assess the concentration of BDNF in ipsilesion and contralesion motor cortex, the concentration of BDNF was measured using ELISA kits (R&D System, location) [29]. The data is normalized to the control rat brains.

ANA-12 Injections

In Study 2, animals received i.p. injections of either ANA-12 (0.5 mg/kg in 17% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) in sterile saline, ip, Sigma) or vehicle (17% DMSO in sterile saline, ip) 4 hours prior to the brain stimulation and rehabilitation session. Animals were injected with an ANA-12 at a dose of .5mg/kg solution of ANA-12 in DMSO because this was found to an optimal dose to induce inhibition of TrkB receptors in the brain for rats [29]. Injections were given 4 hours before rats performed the reaching rehabilitative task to allow for the maximum levels of cortical TrkB inhibition of 30%.

Statistical Analysis

All data are reported as group means with ± standard error of the mean (S.E.M.). Data were considered statistically significant at p ≤ 0.05. Forelimb reaching success during Probe Trials on post-ischemia day 3 (post-op) and after every treatment week (Week 1, 2, and 3) was analyzed using repeated analysis of variance (rANOVA; IBM SPSS Statistics Data Editor Version 18.2). Post-hoc comparisons (Tukey) were used to assess weekly differences between groups. Data from the BDNF ELISA for each hemisphere (ipsilesional and contralesional hemispheres) were analyzed in SPSS using independent t-tests to compare each treatment to age-matched, non-lesion controls.

RESULTS

Study 1. The Comparison of ECS+RT, ICS+RT, and RT alone on Forelimb Recovery and BDNF Concentrations

Forelimb Functional Recovery

As seen in Figure 3A, all groups were trained with their preferred limb to criterion prior to ischemic damage. Following unilateral ET-1 lesion opposite the preferred limb, all groups demonstrated a significant impairment defined here as successfully reaching at less than 20%. There was a significant interaction effect of Group X Week (F(6,189) = 2.363, p≤0.05). We observed a main effect of week, (F(3,189) = 100.631, p≤0.05), suggesting that all groups improved over the course of treatment. There was also an effect of group (F(2,63)=5.126, p≤0.05). Post-hoc tests indicate that ICS is overall a more effective treatment compared to ECS+RT (p≤0.05) and noCS (p≤0.05). As indicated by post-hoc analysis, ICS+RT enhanced motor recovery compared to ECS+RT at week 1 (p≤0.05), at week 2 (p≤0.05) and both ECS+RT (p=0.05) and NoCS+RT (p≤0.05) at week 3. In these severely impaired animals, ICS+RT greatly enhanced reaching performance with the impaired forelimb compared to NoCS and ECS groups.

Figure 3.

A. Percent Successful Retrievals and Recovery Scores ICS+RT improved more than ECS+RT at week 1 (p=.021), at week 2 (p=.035) and both ECS+RT (p=0.026) and NOCS+RT (p=.013) at week 3. When all severely impaired animals are combined, ICS in this model of stroke demonstrates an additive treatment for animals that exhibit greater post-stroke functional deficits.

B. Ipsilesional and Contralesional BDNF Concentrations Cortical punches (3mm) were taken from the primary motor and penumbra areas from stroke and non-stroke hemispheres. Concentrations of BDNF for severely impaired 4 and 9 month rats combined. One-way anova revealed a significant ipsilesional differences between control and ECS+RT (p=.0001). While not significant, there was a trend for an ipsilesional difference between control BDNF levels and NoCS+RT BDNF levels (p=.061). There was also a significant contralesional difference between control and ICS+RT (p=.022). There was also a significant difference between Ipsilesional ICS+RT levels and contralesional ICS+RT levels (p=.045).

Motor Cortical Stimulation Induces BDNF Changes in both the Ipsi-lesional and Contralesional hemisphere

To determine if ICS+RT and ECS+RT differentially alter BDNF protein expression in the motor cortex, we performed an ELISA for BDNF (Fig. 3B). After three weeks of treatment, there were no significant differences between ipsilesional ICS+RT BDNF levels and non-stroke control cortical BDNF levels (t(10)=.299, p>0.05); indicating a possible role of ICS as an additive treatment to RT that increases BDNF levels to pre-stroke levels. However, ECS+RT treated animals had significantly reduced BDNF expression in the ipsilesional cortex compared to non-lesion controls (t(10)=−5.896, p≤.05) indicating ECS+RT’s inability to return BDNF levels to baseline after 3 weeks of treatment after stroke. In the contralesional cortex, ICS+RT resulted in a significant reduction in BDNF expression compared to controls (t(13)=−2.606, p≤0.05) indicating that ICS+RT may downregulate BDNF production in the contralesional hemisphere.

Study 2. Effects of TrkB inhibition on CS and RT related motor recovery

Forelimb Functional Recovery

ANA-12 Inhibition

In study 2, we investigated whether BDNF binding to its TrkB receptor is a key mediator of CS or RT treatment in severely impaired animals. Prior to daily CS and RT treatment, animals were injected with either vehicle or ANA-12, a ligand that reduces BDNF binding to the TrkB receptor. We observed a main effect of week, (F(3,78)= 33.564 p≤0.05), suggesting that all groups improved over the course of treatment. Overall, there were no statistically significant differences (rANOVA) between groups over the course of treatment weeks (F(15,78)=1.051, p≤0.05).

TrkB inhibition does not impact forelimb motor recovery in rats receiving just rehabilitative treatment (F(3,30)=1.033, p>0.05) (Fig. 4A) or inhibitory stimulation treatment (F(3,24)=0.212, p>0.05) (Fig. 4B). For animals that received ECS, there was a deviation between animals that received either vehicle or ANA-12 injections (F(3,24)=2.087, p>0.05) (Fig. 4C). While there was no statistically significant group by week effects, there was a significant difference between groups on reaching success when tested at week 3 (p=0.05) and an overall group effect (F(1,8)=5.827, p≤0.05). A recovery score was calculated (Week 3-PostOP) for animals receiving ECS. As seen in Figure 4D, treatment with ANA-12 significantly reduced recovery of reaching success with the impaired forelimb in groups that received ECS+RT treatment (F(1,5)=10.042, p≤0.05). This suggests that BDNF may play a role in motor recovery in the presence of ECS.

Figure 4.

Percent Successful Retrievals and Recovery Scores: Vehicle and ANA-12 Animals. Rats Received ECS or ICS given concurrently with the single pellet reaching task for 3 weeks following ischemic injury. ECS results in no added benefit in aged animals. A. NOCS. There was not a significant interaction effect of Group X Day (F(2,9)=4.32, p=0.655 and there was not a significant interaction of week (p=0.347). B. ICS. There was not a significant interaction effect of Group X Day (F(2,7)=0.583, p=0.570, but there was a significant interaction of week (p=0.031). C. ECS. There was a mean difference at week 3 between groups:(F(1,8)=5.329, p=0.05). D. ECS Mean Difference. There is a mean difference at Week 3 following ECS+RT between Vehicle and ANA-12. A recovery score was calculated (Week 3-PostOP_for animals receiving ECS. There was a mean difference at Week 3 between groups: (F(1,5)=10.042, p=0.025).

Recovery in all TrkB-Inhibited (ANA-12) Groups

We then compared the different CS treatment groups within the subgroup that received ANA-12 injections (Fig. 5). Animals that received ECS+ANA-12 appear to be most detrimentally affected by a TrkB inhibition. Overall, there was a main effect of week, indicating that all groups improved over time (F(3,36)=9.952, p≤0.05). While there was not a significant interaction effect of Week X Group (F(6,36) =1.1062, p >0.05, there was a group effect (F(2,12)=4.133, p≤0.05) indicating a difference in IC+RT treatment compared to ECS+RT Post-hoc comparisons (Tukey) revealed ICS+ −12 had greater motor recovery than ECS+ANA-12 (p≤0.05).

Figure 5.

Percent Successful Retrievals: All ANA-12 Groups. A comparison of the different CS treatment groups within the subgroup that received ANA-12 injections. At week 1, there was a significant difference between ICS+ANA12 and ECS+ANA12 (p=.05). Post hoc comparisons (Tukey) reveal no significant differences between NOCS+ANA12 and ECS+ANA12 (p=0.311) or NOCS+ANA12 and ICS+ANA12 (p=0.512) at week 1.

DISCUSSION

These studies investigated whether inhibitory or excitatory cortical stimulation would enhance the effectiveness of RT in animals with severe initial impairments after a unilateral, focal cortical stroke. As discussed in more detail below, delivering inhibitory (1 Hz) stimulation over the non-infarcted motor cortex concurrent with impaired forelimb reach training (RT) significantly improved motor recovery compared to RT alone or RT concurrent with excitatory stimulation, in severely impaired animals. Similar to previous findings, excitatory ipsilesion stimulation did not further enhance RT effectiveness in animals with severe motor impairments compared to RT alone [10]. Our data also suggests that BDNF expression in the lesion cortex was not altered by RT alone or inhibitory stimulation when combined with RT. Counterintuitively, inhibitory CS also resulted in significantly reduced BDNF expression in the non-infarcted motor cortex compared to lesioned cortex.

On the other hand, after 21 days of 100 HZ bipolar stimulation of the ipsilesion motor cortex, there is a significant reduction in BDNF expression in the remaining motor cortex compared to non-stroke controls. Inhibiting BDNF binding to its TrkB receptor, via the ANA12 ligand, resulted in greater impairment in impaired forelimb reaching success only in subjects that received RT concurrent with ipsilesion 100Hz stimulation.

As discussed more fully below, these results suggest that while BDNF may not be a key mediator of ICS enhancement of RT-related functional motor improvements.

We report that inhibitory stimulation over the non-infarcted motor cortex combined with impaired forelimb reach training (ICS+RT) resulted in a significant improvement in forelimb functional recovery compared to ECS+RT or RT alone. Animal studies have shown that the contralesional cortex may be highly involved in recovery of function, as indicated by greater contralesional cortical activation in strokes that produce more damage to the ipsilesional hemisphere [30, 31]. Previous studies also suggest that when the lesion is large, and thus likely to produce greater impairments, the contralesional hemisphere is important in reestablishing lost functions [32]. Following unilateral stroke, damage-related alterations in transcallosal inhibition can alter the balance of inter-cortical activity such that the ipsilesional cortex becomes hypoexcitable and the non-lesion cortex is hyper-excitable [33]. In humans, after a unilateral cortical stroke impaired limb activity results in a greater BOLD signal in the non-lesion hemisphere compared to the lesion hemisphere [34]. Based upon these prior studies, it is our hypothesis that 1Hz stimulation over the contralesional cortex may improve the effectiveness of RT by reducing the non-lesion cortex hyper-excitability and thus reducing transcallosal inhibition of the stroke cortex. However, we did not measure cortical excitability in these studies and thus these are hypothetical explanations. Future studies are needed to investigate this potential explanation.

We found that 1 HZ CS delivered over the contralesional motor cortex during daily RT improved forelimb function and increased BDNF levels in the ipsilesional cortex to control, non-lesion levels. The ICS over the contralesional cortex likely releases ipsilesional inhibition, resulting in reduced activation of ipsilesional GABAergic interneurons and subsequently disinhibiting pyramidal cells (Murphy et al., 2016). This in turn may permit greater RT-induced activation of motor cortical neurons and thus may result in greater BDNF expression. It is also possible that BDNF is not related to the behaviors being tested or be related to glial cell expression. Glial cells in resting states release neurotrophic factors to help maintain homeostasis. It is possible that after injury, once glia become chronically activated, they no longer contribute to BDNF production, thus dampening any potential effects from ANA-12. However, this was not measured in these studies and further studies are needed. These studies do add to a growing body of literature attempting to elucidate when the contralesional hemisphere may provide a more positive role in stroke recovery.

One of the questions we sought to investigate was the relationship between motor recovery, treatment, and BDNF levels in the motor cortical regions. We found that ICS+RT induced improvements in functional motor recovery which was related to changes in both ipsilesional and contralesional BDNF concentrations. Within the ipsilesional cortex, there is not a significant difference between ICS+RT and control (non-stroke animals) BDNF levels. On the other hand, we also found that contralesional BDNF levels in the ICS+RT group were reduced compared to contralesional control BDNF levels. With further investigation, it is plausible that inhibitory stimulation to the non-stroke contralesional cortex could be down regulating the over excitation within the cortex and thus BDNF production, resulting in greater excitation and BDNF synthesis in the ipsilesional cortex. This is important since previous studies have already reported that motor rehabilitative tasks are only effective in improving recovery when BDNF levels are increased [35]. Our findings fit with previous findings that relate motor recovery with increases in BDNF levels and further suggests that effective rehabilitative motor training increases BDNF concentration levels.

We investigated whether the slight elevations in BDNF concentrations and improvements in functional recovery after treatment would be diminished if BDNF binding to its TrkB receptor was inhibited by pre-treating animals with the TrkB antagonist ANA-12. While we did not verify the rate of TrkB receptor antagonism in these studies, based upon several previous investigations ANA-12 administered at this dose inhibits 30% of TrkB binding. We found that TrkB inhibition negatively influences animals receiving ECS+RT and not ICS+RT or NoCS+RT. It is possible that ipsilesional high frequency stimulation delivered early after ischemia could exacerbate neuronal vulnerability in an area already undergoing cell death and dysfunction and may further reduce stroke related declines in BDNF expression [31]. Thus, the combination of excitatory stimulation and reduced BDNF/TrkB signaling could produce a more detrimental environment and limit the ability for RT related recovery to occur.

Alternatively, low frequency stimulation over the contralesional (noninfarcted) cortex may not further exacerbate lesion-related cellular dysfunction. The contralesional hemisphere is not subject to the same diminished neuronal plasticity and neurotrophic factors that are in the ipsilesional cortex, making inhibition of TrkB not as detrimental in producing deficits in motor recovery in animals that are receiving stimulation to this area.

Conclusions

We hypothesized that unlike excitatory ipsi-infarct cortical stimulation, inhibitory stimulation combined with impaired forelimb rehabilitation would significantly improve motor recovery in animals with severe impairments. We also hypothesized that effective CS may affect or be related to cortical BDNF. Using a combination of sensitive behavioral tasks and assays to investigate the role of inhibitory stimulation on behavioral outcome following stroke, we report that inhibitory stimulation of the non-lesion motor cortex concurrent with forelimb rehabilitative training enhances forelimb motor recovery in severely impaired rats following experimental stroke. Our data also suggests that inhibitory stimulation alters BDNF cortical expression and may be related to ICS-related motor improvements. We also report that the addition of ipsilesion high frequency stimulation combined with partial inhibition of TrkB receptors early after stroke, may exacerbate lesion induced motor impairments or inhibit RT-induced motor recovery. Together, these studies do suggest that ICS was more effective than ECS as an adjunctive treatment for stroke recovery. We also provide promising data supporting the role of BDNF in motor recovery and indications that the location and frequency of CS may play a role or be dependent upon BDNF expression.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work is supported by the NIH BluePrint D-SPAN Award (F99/K00) (SK). This work is also supported by The Delaware-CTR ACCEL Institutional Development Award (IDeA) from the (NIGMS/NIH U54-GM104941), NC NM4R (P2CHD086844), COBRE in Stroke Recovery (P20 GM109040), and MUSC’s NIH training grants (R25 GM072643, TL1 TR001451 and TL1 TR000061) (DLA).

Abbreviations:

- ANA-12

N [2-[(2-oxoazepan-3-yl)carbomoyl]phenyl]-1-benzothiophene-2-carboxamide

- BDNF

Brain Derived Neurotrophic Factor

- CNS

central nervous system

- CS

Cortical Stimulation

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- ELISA

enzyme- linked immunosorbent assay

- ECS

Excitatory Cortical Stimulation

- ET-1

Endothelin-1

- GABA

y-aminobutyric acid

- Hz

hertz

- IACUC

Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee

- ICS

Inhibitory Cortical Stimulation

- LTD

Long Term Depression

- LTP

Long Term Potentiation

- ML

medial lateral

- NGF

nerve growth factor

- RT

Rehabilitative Training

- Sc

subcutaneous

- SPR

Single Pellet Reaching Task

- TMS

Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation

- TrkB

Tropomyosin-related Kinase B

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: “Disclaimer: This article was prepared while DeAnna L. Adkins was employed at the Medical University of South Carolina. The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of the National Institutes of Health, the Department of Health and Human Services, or the United States government.”

Declarations of Interest: none

References

- [1].American Heart Association. Impact of Stroke (Stroke Statistics). 2012. [cited 2013 July 15]; Available from: http://www.strokeassociation.org/STROKEORG/AboutStroke/Impact-of-Stroke-Stroke-statistics_UCM_310728_Article.jsp

- [2].Hatem SM, Saussez G, Della Faille M, Prist V, Zhang X, Dispa D, & Bleyenheuft Y (2016). Rehabilitation of Motor Function after Stroke: A Multiple Systematic Review Focused on Techniques to Stimulate Upper Extremity Recovery. Frontiers in human neuroscience, 10, 442. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2016.00442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Bonita R, Beaglehole R (1988). Recovery of motor function after stroke. Stroke 19, 1497–1500. 10.1161/01.STR.19.12.1497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Hosomi K, Seymour B, Saitoh Y (2015). Modulating the pain network—neurostimulation for central poststroke pain. Nat. Rev. Neurol 11 290–299. 10.1038/nrneurol.2015.58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Claflin ES, Krishnan C, Khot SP. Emerging treatments for motor rehabilitation after stroke. Neurohospitalist. 2015;5(2):77–88. doi: 10.1177/1941874414561023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Plautz EJ, Barbay S, Frost SB, et al. Effects of Subdural Monopolar Cortical Stimulation Paired With Rehabilitative Training on Behavioral and Neurophysiological Recovery After Cortical Ischemic Stroke in Adult Squirrel Monkeys. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2016;30(2): 159–172. doi: 10.1177/1545968315619701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Adkins-Muir DL, Jones TA. Cortical electrical stimulation combined with rehabilitative training: enhanced functional recovery and dendritic plasticity following focal cortical ischemia in rats. Neurol Res. 2003;25:780–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Kleim JA, Brunean R, VandenBerg P, MacDonald E, Mulrooney R, Pocock D, Motor cortex stimulation enhances motor recovery and reduces peri-infarct dysfunction following ischemic insult. Neurol Res. 2003;25:789–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Teskey GC, Saveyn A, Steppe., Kathy McGuire M A. Cortical stimulation improves skilled forelimb use follooing a focal ischemic infarct in the rat. Neurol Res, 2003. 25(8): p. 794–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Adkins DL, Hsu JE, and Jones TA, Motor cortical stimulation promotes synaptic plasticity and behavioral improvements following sensorimotor cortex lesions. Experimental Neurology, 2008. 212(1): p. 14–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Jones TA and Adkins DL, Motor System Reorganization After Stroke: Stimulating and Training Toward Perfection. Physiology, 2015. 30(5): p. 358–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].O’Bryant AJ, et al. , Enduring Poststroke Motor Functional Improvements by a Well-Timed Combination of Motor Rehabilitative Training and Cortical Stimulation in Rats. Neurorehabilitation and neural repair, 2016. 30(2): p. 143–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Plow EB, Carey JR, Nudo RJ, Pascual-Leone A (2009). Invasive cortical stimulation to promote recovery of function after stroke: a critical appraisal. Stroke 40 1926–1931. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.540823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Mally K, Dinya E (2008). Recovery of motor disability spasticity in post-stroke after repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS). Brain Res Bull. 2008 July 1;76(4):388–95. doi: 10.1016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Nowak DA, Grefkes C, Dafotakis M, Eickhoff S, Küst J, Karbe H, Fink GR. (2008). Effects of low-frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation of the contralesional primary motor cortex on movement kinematics and neural activity in subcortical stroke. Arch Neurol. 2008 June;65(6):741–7. doi: 10.1001/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Takeuchi N, Tada T, Toshima M, Chuma T, Matsuo Y, Ikoma K. (2008). Inhibition of the unaffected motor cortex by 1 Hz repetitive transcranical magnetic stimulation enhances motor performance and training effect of the paretic hand in patients with chronic stroke. J Rehabil Med. 2008 April;40(4):298–303. doi: 10.2340/16501977-0181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Lasek-Bal A, Jędrzejowska-Szypułka H, Różycka J, Bal W, Holecki M, Duława J, & Lewin-Kowalik J (2015). Low Concentration of BDNF in the Acute Phase of Ischemic Stroke as a Factor in Poor Prognosis in Terms of Functional Status of Patients. Medical Science Monitor : International Medical Journal of Experimental and Clinical Research, 21, 3900–3905. 10.12659/MSM.895358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].VandenBerg PM, Bruneau RM, Thomas N, Kleim JA. BDNF is required for maintaining motor map integrity in adult cerebral cortex. Soc Neurosci Abstr. 2004;681:5 [Google Scholar]

- [19].McCullough MJ, Peplinski NG, Kinnell KR, Spitsbergen JM (2011). Glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor protein content in rat skeletal muscle is altered by increased physical activity in vivo and invitro. Neuroscience, 174: 234–244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Alcántara S, Frisén J, del Ri JA, Soriano E, Barbacid M, Silos-Santiago I. TrkB signaling is required for postnatal survival of CNS neurons and protects hippocampal and motor neurons from axotomy-induced cell death. J Neurosci. 1997;17:3623–3633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Wang HY, Crupi D, Liu J, Stucky A, Cruciata G, Di Rocco A, Friedman E, Quartarone A, Ghilardi MF. [2011] Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation enhances BDNF-TrkB signaling in both brain and lymphocyte. J Neurosci. 2011 July 27;31(30):11044–54. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2125-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Sleiman SF, Henry J2,3,4,5, Al-Haddad R1, El Hayek L1, Abou Haidar E1, Stringer T2,3,4,5, Ulja D2,3,4,5, Karuppagounder SS6,7, Holson EB8,9, Ratan RR6,7, Ninan I2,3,4,5, Chao MV2,3,4,5. Exercise promotes the expression of brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) through the action of the ketone body β-hydroxybutyrate. Elife. 2016. June 2;5 10.7554/eLife.15092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Macrae I, Robinson M, Graham D, Reid J, McCulloch J. 1993. Endothelin- 1-induced reductions in cerebral blood flow: Dose dependency, time course, and neuropathological consequences. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 13:276–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Fuxe K, Bjelke B, Andbjer B, Grahn H, Rimondini R, Agnati L. 1997. Endothelin-1 induced lesions of the fronto-parietal cortex of the rat: A possible model of focal cortical ischemia. NeuroReport 8:2623–2629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Whishaw IQ, Pellis SM, Gorny BP. Skilled reaching in rats and humans: evidence for parallel development or homology. Behav Brain Res 47: 59–70, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].McKenna JE, Whishaw IQ. Journal of Neuroscience 1 March 1999, 19 (5) 1885–1894; DOI: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-05-01885.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Whishaw IQ, Suchowersky O, Davis L, Sarna J, Metz GA, Pellis SM. Impairment of pronation, supination, and body co-ordination in reach-to-grasp tasks in human Parkinson’s disease (PD) reveals homology to deficits in animal models. Behav Brain Res. 2002;133:165–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Boger HA et al. “Effects of brain-derived neurotrophic factor on dopaminergic function and motor behavior during aging.” Genes, brain, and behavior vol. 10,2 (2011): 186–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2010.00654.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Cazorla M1, Prémont J, Mann A, Girard N, Kellendonk C, Rognan D. Identification of a low-molecular weight TrkB antagonist with anxiolytic and antidepressant activity in mice. J Clin Invest. 2011. May;121(5):1846–57. doi: 10.1172/JCI43992. Epub 2011 Apr 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Dijkhuizen RM1, Singhal AB, Mandeville JB, Wu O, Halpern EF, Finklestein SP, Rosen BR, Lo EH. Correlation between brain reorganization, ischemic damage, and neurologic status after transient focal cerebral ischemia in rats: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. J Neurosci. 2003. January 15;23(2):510–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Schaechter JD1, Perdue KL. Enhanced cortical activation in the contralesional hemisphere of chronic stroke patients in response to motor skill challenge. Cereb Cortex. 2008. March;18(3):638–47. Epub 2007 Jun 29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Pino GD, Maravita A, Zollo L3, Guglielmelli E, Di Lazzaro V. Augmentation-related brain plasticity. Front Syst Neurosci. 2014. June 11;8:109. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2014.00109. eCollection 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Murase N, Duque J, Mazzocchio R, Cohen LG. Influence of interhemispheric interactions on motor function in chronic stroke. Ann Neurol. 2004. March;55(3):400–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Cramer SC, Nelles G, Benson RR, Kaplan JD, Parker RA, Kwong KK, Kennedy DN, Finklestein SP, Rosen BR. A functional MRI study of subjects recovered from hemiparetic stroke. Stroke. 1997;28:2518–2527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Murphy SC, Palmer LM, Nyffeler T, Müri RM, Larkum ME. Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) inhibits cortical dendrites. Elife. 2016;5:e13598 Published 2016 Mar 18. doi: 10.7554/eLife.13598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].MacLellan CL, Keough MB, Granter-Button S, Chernenko GA, Butt S, Corbett D. A critical threshold of rehabilitation involving brain-derived neurotrophic factor is required for poststroke recovery. Neurorehabilitation and Neural Repair. 2011;25(8):740–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]