Abstract

Purpose

ZEN-3694 is a bromodomain extra-terminal inhibitor (BETi) with activity in androgen signaling inhibitor (ASI)-resistant models. The safety and efficacy of ZEN-3694 plus enzalutamide (ENZ) was evaluated in a phase 1b/2a study in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC).

Experimental Design

Patients had progressive mCRPC with prior resistance to abiraterone (ABI) and/or ENZ. 3+3 dose escalation was followed by dose expansion in parallel cohorts (ZEN-3694 at 48 and 96 mg orally once daily, respectively).

Results

Seventy-five patients were enrolled (N = 26 and 14 in Dose Expansion at low- and high-dose ZEN-3694, respectively). Thirty (40.0%) patients were resistant to ABI, thirty-four (45.3%) to ENZ, and eleven (14.7%) to both. ZEN-3694 dosing ranged from 36 mg to 144 mg daily without reaching an MTD. Fourteen patients (18.7%) experienced grade ≥ 3 toxicities, including three patients with Grade 3 thrombocytopenia (4%). An exposure-dependent decrease in whole blood RNA expression of BETi targets was observed (up to 4-fold mean difference at 4 hours post-ZEN-3694 dose; p ≤ 0.0001). The median radiographic progression-free survival (rPFS) was 9.0 months (95% CI: 4.6, 12.9) and composite median radiographic or clinical progression-free survival was 5.5 months (95% CI: 4.0, 7.8). Median duration of treatment was 3.5 months (range 0 – 34.7+). Lower AR transcriptional activity in baseline tumor biopsies was associated with longer rPFS (median rPFS 10.4 vs. 4.3 months).

Conclusions

ZEN-3694 plus ENZ demonstrated acceptable tolerability and potential efficacy in patients with ASI-resistant mCRPC. Further prospective study is warranted including in mCRPC harboring low AR transcriptional activity.

Introduction

Prostate cancer is the most common malignancy and second leading cause of death among men in the United States.1 Androgen signaling blockade with either androgen receptor (AR) antagonism or CYP17 inhibition improves long-term survival in both metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) and metastatic castration-sensitive disease.2–5 However treatment resistance is universal, and cross resistance between AR antagonists and CYP17 inhibitors limits the clinical utility of these agents when used sequentially.6–10

Multiple mechanisms of therapeutic resistance to AR pathway inhibitors have been described, including amplification of the AR gene and its enhancers, up-regulation of intra-tumoral androgen synthesis, generation of ligand-independent AR splice variants, activation of alternative oncogenic signaling pathways including MYC, trans-differentiation to an AR-independent, neuroendocrine phenotype, and co-option of alternative steroid hormone receptors including the glucocorticoid receptor (GR).11–16 A broad therapeutic approach capable of affecting expression/signaling of multiple pathways may provide a means to reverse resistance and restore sensitivity to AR targeting therapy.

Proteins of the BET bromodomain family are epigenetic readers that bind to acetylated histones through their bromodomains to affect gene transcription.17 They preferentially localize at sites of enhancers of various oncogenes to promote tumorigenesis and progression. ZEN-3694 is an orally bioavailable, second generation, potent pan-BET bromodomain inhibitor that leads to down-regulation of expression of AR-signaling, AR splice variants, MYC, GR, and other oncogenes in multiple CRPC prostate cancer models, and has significant in vivo activity as single agents, with evidence of synergy when combined with enzalutamide.18

We conducted a first-in-human phase 1b/2 dose escalation/expansion study of ZEN-3694 in combination with enzalutamide in patients with mCRPC and prior progression on one or more androgen signaling inhibitor.

METHODS

Patient Population

Patients had histologically confirmed mCRPC with progression at study entry by Prostate Cancer Working Group 2 (PCWG2) criteria.19 Patients were required to have progression on prior abiraterone and/or enzalutamide prior to study entry, no prior docetaxel for the treatment of mCRPC, serum testosterone < 50 ng/dL with maintenance of androgen deprivation therapy during study treatment, ECOG performance status of 0 or 1, adequate organ function including absolute neutrophil count > 1.5 × 109/L, platelet count > 100,000, total bilirubin < 1.5 × ULN, creatinine clearance > 60 ml/min. Patients with uncontrolled hypertension or NYHA class II or higher congestive heart failure were excluded.

Study approval was obtained from the ethics committees at the participating institutions and regulatory authorities. All patients gave written informed consent. The study followed the Declaration of Helsinki and good clinical practice guidelines (NCT02711956).

Study Design and Treatment Schedule

This was a phase 1b/2, multicenter, open-label, combination dose-escalation study of ZEN-3694 in combination with the standard dose of enzalutamide 160 mg daily. Lead-in treatment period with enzalutamide monotherapy (day −14 to day −1) was required in subjects not already receiving enzalutamide at the time of study enrollment. Patients continued treatment until radiographic progression by PCWG2 criteria, unequivocal clinical progression or unacceptable toxicity. PSA progression alone was not used as a criterion for treatment discontinuation.

The starting dose of ZEN-3694 was 36 mg orally once daily. A 3+3 dose-escalation schema was utilized up to a maximum administered dose of 144 mg daily. Dose expansion was subsequently performed in two cohorts in parallel: 1) Low dose: ZEN-3694 at 48 mg daily (N = 14), and 2) High dose ZEN-3694 96 mg daily (N = 26).

A formal interim analysis was not planned, however interim data were reviewed on an ongoing basis. The final planned analyses were performed after 75 patients were enrolled and the database was locked on 06-Feb-2020.

The primary study endpoint was safety and the recommended phase 2 dose of ZEN-3694 in combination with enzalutamide. Secondary endpoints included pharmacokinetic (PK) assessment of ZEN-3694 and enzalutamide, PSA50 response (≥50% decline in PSA from baseline confirmed ≥ 4 weeks later) rate, duration of PSA50 response, and radiographic progression-free survival. Soft tissue radiographic progression and responses were assessed according to RECIST v1.1 criteria. Progression of bone metastases was assessed using PCWG2 criteria. Post-hoc analyses were performed to assess composite progression-free survival, defined as first occurrence of radiographic or clinical progression or death, as well as PSA progression-free survival by PCWG2 criteria. Correlative endpoints included pharmacodynamic assessment of ZEN-3694 in combination with enzalutamide and relationship between tumor genomic/transcriptional profile, protein expression, and clinical variables with clinical outcomes on treatment.

Safety and Efficacy Assessments

Clinical and laboratory assessments were conducted at baseline and weekly during cycles 1 and 2 (28 day cycle length), every 2 weeks in cycle 3, and then every 4 weeks thereafter. Tumor response monitoring was performed using whole body bone scan and cross-sectional imaging of the chest/abdomen/pelvis at baseline and every 2 cycles thereafter. Adverse events were graded using Common Toxicity Criteria version 4.0.

Pharmacodynamic/Exploratory Assessments

Whole blood RNA for assessment of BET inhibitor target gene expression (MYC, IL-8, CCR1, GPR183, HEXIM1, and IL1RN) was collected pre-dose, 2, 4, 6 and 24 hours post-C1D1 dose.20 Baseline and on-treatment metastatic tumor biopsies of bone or soft tissue were obtained whenever feasible, and were evaluated by RNA-seq and immunohistochemistry (IHC) for protein expression of AR. Quality of the FASTQ files was verified by FASTQC2, and reads were aligned on BaseSpace (https://basespace.illumina.com) using the RNA-Seq alignment App (version 1.1.1) with the default parameters (STAR aligner version 2.5.0b, UCSC hg19 reference genome). Gene expression levels (FPKM) for baseline biopsies were estimated using Cufflinks (version 2.2.1). For the paired biopsies, aligned reads were used as input for DESeq2 (version 1.1.0) to enable pairwise differential gene expression analysis using the default parameters. Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was performed on transcriptional data when available, and previously validated AR, prostate cancer and MYC transcriptional signatures were additionally applied to the transcriptional data.21–22 For the BETi signature, significant genes (p-value <0.05) that were >2-fold down-regulated upon exposure of 0.5uM I-BET762 for 24 hours in LNCaP prostate cancer cells were selected.23 Archival tumor tissue was obtained whenever feasible for analysis of whole transcriptome and exome sequencing.

Pharmacokinetic Assessments

Plasma levels of ZEN-3694, the bioactive first-order metabolite ZEN-3791, and enzalutamide were measured pre-dose and up to 24 hours post-dose on days 1 and 15 of cycle. Plasma concentrations were determined using validated liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry analysis (LC/MS/MS).

RESULTS

Study Population and Patient Disposition

A total of 75 patients were enrolled from December 2016 to April 2019 across 7 investigational sites. Baseline characteristics of the enrolled patients are shown in Table 1. At study entry, 30 (40.0%) of patients had previously experienced disease progression on abiraterone, 34 (45.3%) on enzalutamide, and 11 (14.7%) on both. Twelve (16%) patients experienced prior primary resistance to first-line AR targeted therapy, defined in post-hoc fashion as treatment duration of less than six months. Forty-two (56%) patients had evidence of radiographic and/or clinical progression at study entry.

Table 1:

Baseline Characteristics

| Study Cohort (n=75)* | |

|---|---|

| Median age (range), years | 70 (47–89) |

| ECOG score | |

| 0 | 42 (56%) |

| 1 | 33 (44%) |

| Opioid analgesic use | 18 (24%) |

| Visceral metastases at study entry (%) | 21 (28%) |

| Median PSA, ng/mL (range) | 26.99 (0.15 – 1701.8) |

| Median ALP, U/L (range) | 82 (33 – 487) |

| Median LDH, U/L (range) | 188 (98 – 543) |

| Median Hemoglobin, g/dL (range) | 13.2 (6.4 – 20.2) |

| Halabi risk category24 | |

| Low | 50 (67) |

| Intermediate | 16 (21) |

| High | 8 (11) |

| Unknown | 1 (1) |

| Prior number of systemic cancer treatments (range) | 3 (1–7) |

| Prior resistance to AR targeted therapy (%) | |

| Abiraterone | 30 (40) |

| Enzalutamide | 34 (45) |

| Both | 11 (15) |

| Duration of prior AR targeted therapy (range), months | 14.3 (1.0–58.3) |

| Reason for prior abiraterone or enzalutamide discontinuation | |

| Radiographic progression | 8 (11%) |

| Radiographic and PSA progression | 31 (41%) |

| Clinical and PSA progression | 3 (4%) |

| PSA progression | 33 (44%) |

| Clinical progression | 0 |

ALP, alkaline phosphatase; AR, androgen receptor; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; PSA, prostate-specific antigen.

For data recorded in the clinical database as of the data cutoff date of 07 January 2020.

The median duration of treatment was 3.5 months (range 0 – 34.7+). As of date of data cut-off, 7 patients (9%) remain on treatment without progression, with duration of therapy ranging from 15.0+ – 34.7+ months. Forty-eight patients (64%) discontinued for disease progression; nine patients (12%) discontinued for adverse event, and eleven (16%) withdrew from study.

Safety Results

The proportion of patients who experienced Grade ≥ 3 treatment-related adverse event was 18.7% (n = 14). The most common grade ≥ 3 adverse events (≥ 2 patients) included: nausea (n = 3; 4 %), thrombocytopenia (n = 3; 4%), anemia (n = 2; 2.7%), fatigue (n = 2; 2.7%), and hypophosphatemia (n = 2; 2.7%). There were no clinically significant bleeding events observed on treatment.

The most commonly reported ZEN003694-related AEs (any grade severity, occurring in ≥ 10% of patients, in order of incidence) were: visual symptoms (described as a transitory perception of brighter lights and/or light flashes, with or without visual color tinges, as well as trouble navigating in dim light) (67%), nausea (45%), fatigue (40%), decreased appetite (25%), dysgeusia (20%), thrombocytopenia (15%), and weight decreased (11%) (Table 2). Visual symptoms were Grade 1 in all cases, resolved 60–90 minutes after dosing, were successfully mitigated with implementation of dosing before bedtime, and resulted in no functional consequences upon repeat eye exams throughout study participation.

Table 2.

Summary of All Grades Treatment-related Adverse Events by Dose Level of ZEN-3694

| 36mg QD n=4 | 48 mg QD n=21 | 6Dmg QD n=6 | 72mg QD n=6 | 96mg QD n=31 | 120mg QD N=4 | 144mg QD N=3 | TOTAL n=75 (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood creatinine Increased | 2 | 3 | 5 (6.7) | |||||

| Constipation | 1 | 3 | 4 (5.3) | |||||

| Decreased Appetite | 2 | 2 | 1 | 10 | 3 | 2 | 20 (26.7) | |

| Diarrhea | 1 | 5 | 6(8) | |||||

| Dizziness | 1 | 3 | 4 (5.3) | |||||

| Dysgeusia | 2 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 1 | 3 | 16 (21.3) | |

| Dyspepsia | 1 | 2 | 3(4) | |||||

| Fatigue | 1 | 8 | 1 | 2 | 13 | 3 | 1 | 29 (38.7) |

| Nasal congestion | 3 | 3(4) | ||||||

| Nausea | 7 | 2 | 3 | 17 | 3 | 2 | 34 (45.3) | |

| Photopsia | 1 | 3 | 4 (5.3) | |||||

| Photosensitivity | 2 | 3 | 5 (6.7) | |||||

| Rash | 3 | 3(4) | ||||||

| Rash maculopapular | 3 | 1 | 1 | 5 (6.7) | ||||

| Taste disorder | 1 | 1 | 3 | 5 (6.7) | ||||

| Thrombocytopenia | 1 | 1 | 2 | 6 | 1 | 11 (14.7) | ||

| Vision blurred | 2 | 1 | 3(4) | |||||

| Visual symptoms | 3 | 12 | 4 | 6 | 17 | 4 | 2 | 48 (64) |

| Vomiting | 1 | 3 | 1 | 5 (6.7) | ||||

| Weight loss & Abnormal WL | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 8(10.7) |

Visual symptoms defined as a transitory perception of bright lights and/or light flashes with or without visual color tinges

Dose reductions and/or treatment discontinuation due to adverse events were required in 24/75 (32%) of patients. The percentage of patients requiring dose reduction and/or discontinuation ranged from 10%−35% for doses from 36 mg – 96 mg/day, in contrast to 75% and 100% at ZEN-3694 dose levels of 120 and 144 mg/day, respectively (Supplementary Table 1). The class of adverse events leading to dose reduction and/or discontinuation were related to GI toxicities in 83% of occurrences.

Determination of Maximum Tolerated Dose and Recommended Phase 2 Dose

In the dose escalation, 35 patients were enrolled across dose levels ranging from 36 to 144 mg daily. The maximal tolerated dose was not reached. One patient experienced a dose-limiting toxicity at the 96 mg/day dose level (Grade 3 nausea necessitating missing > 25% of scheduled doses in cycle 1). Based on the aggregate of pharmacodynamic data indicating dose exposure-dependent down-regulation of BETi target gene expression with a plateau of effect at doses above 96 mg/day, the high percentage of patients requiring dose interruptions/reductions at doses above 96 mg/day, and a comparable PK/PD effect with pre-clinical models treated at efficacious doses, 96 mg/day was chosen as the recommended phase 2 dose of ZEN-3694 for Dose Expansion (N = 26). An additional Dose Expansion cohort of 48 mg/day (N = 14) was also enrolled, to better characterize the exposure-effect relationship.

Pharmacokinetic Analyses

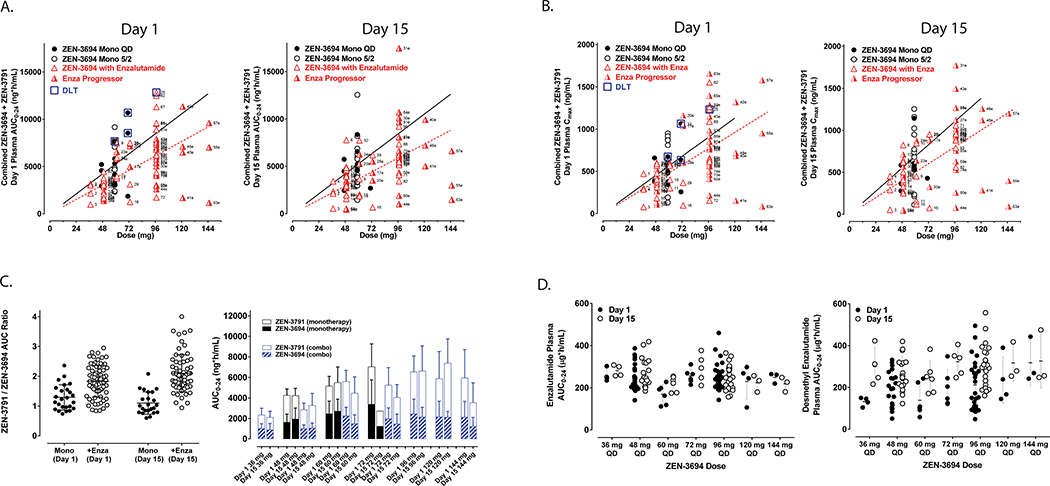

The AUC0–24 and the Cmax of combined ZEN-3694 (parent compound) + ZEN-3791 (active metabolite), on Day 1 and Day 15 of cycle 1, are shown in Figure 1A and Figure 1B, respectively. Less than dose proportional increase in exposure was observed at doses higher than 96 mg daily. The estimated Tmax and half-life of ZEN-3694+ZEN-3791 were 2h and 5–6h, respectively. The ratio of ZEN-3791 metabolite to parent compound ZEN-3694 was increased on Day 15 compared to Day 1, likely related to enzalutamide-mediated induction of CYP3A4 metabolism (Figure 1C). The observed plasma concentrations of ZEN-3694 + ZEN-3791 were similar to ZEN-3694 monotherapy pharmacokinetics previously reported.24 Likewise, there was no significant impact of ZEN-3694 on enzalutamide and desmethyl enzalutamide concentrations (Figure 1D).

Figure 1. Pharmacokinetic analyses.

A and B. Area-under-the-curve (AUC) from 0 to 24 hours (AUC0–24) and maximum serum concentration, respectively, of ZEN-3694 + ZEN-3791 (first generation active metabolite) serum concentration on day 1 and day 15 of cycle 1 (red triangles). Overlaid AUC0–24 data from the monotherapy trial of ZEN-369423 are shown for dose levels 48 and 72 mg daily (black circles). C. Ratio of ZEN-3791 (first generation active metabolite) vs. ZEN-3694 (parent compound) from the prior monotherapy trial23 and in combination with enzalutamide on day 1 and day 15 of cycle 1. D. Steady-state serum concentration of enzalutamide and desmethylenzalutamide following 14 day lead-in of enzalutamide (day −14 to day −1), by ZEN-3694 dose level.

Pharmacodynamic Analyses

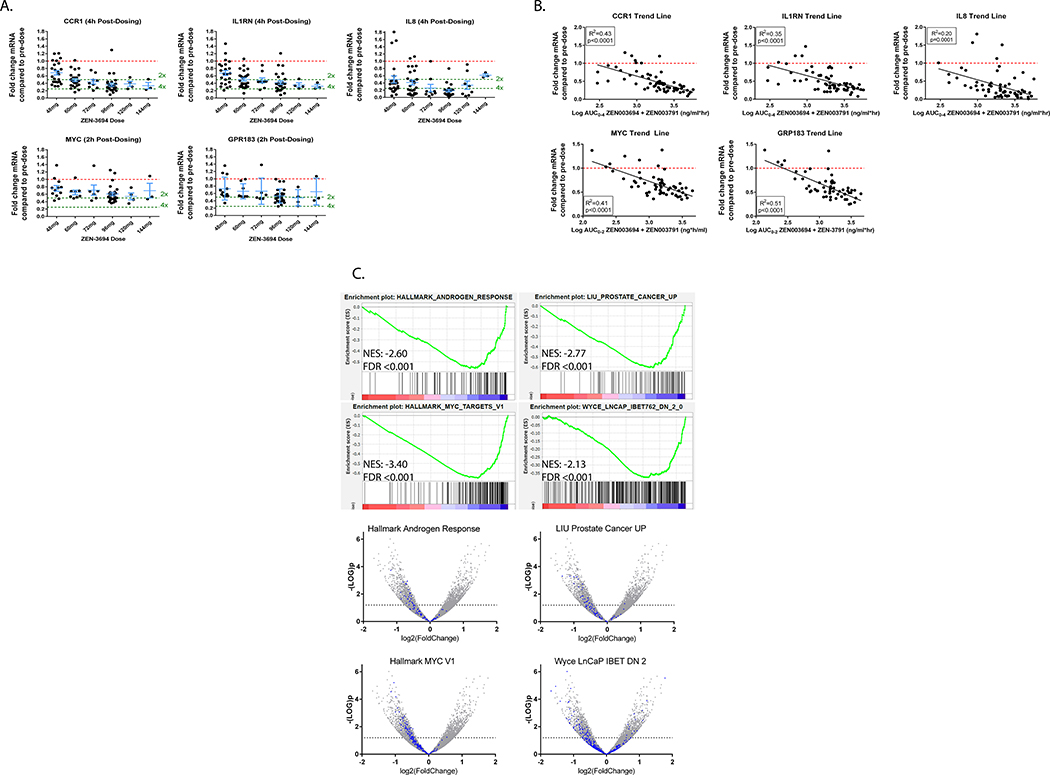

Pre- and up to 24 hour post-dose whole blood RNA analyses were available from 69 patients enrolled on study. There was a dose-dependent 2–4 fold decrease in the whole blood mRNA levels of the BET inhibitor target genes MYC, IL-8, CCR1, GPR183, and IL1RN (Figure 2A) upon treatment with ZEN-3694, which was sustained for at least 8 hours. Decrease in expression of BET inhibitor target genes appeared to plateau at ZEN-3694 dose levels ≥ 96 mg. There was a direct correlation between cumulative exposure to ZEN-3694 + ZEN-3791 (AUC0–2 for MYC and GPR183, and AUC0–4 for CCR1, IL1RN, and IL-8) with down-regulation of whole blood mRNA levels of the BET inhibitor target genes (R2 ranging from 0.20 to 0.51, p values ≤ 0.0001) (Figure 2B).

Figure 2. Pharmacodynamic assessments.

A. Fold-change from baseline in whole blood RNA expression of BET inhibitor target genes CCR1, IL1RN, IL-8, MYC, and GPR183 by ZEN-3694 dose level. B. Correlation between fold change from baseline in whole blood RNA expression of BET inhibitor target genes with AUC0–24 of ZEN-3694 + ZEN-3791 indicates strong PK-PD relationship. C. Gene set enrichment analysis of change from baseline in gene expression by RNA-Seq in paired metastatic tumor biopsies. Down-regulation of MYC signaling pathway is observed in on-treatment versus baseline tumor biopsy.

Four patients had evaluable paired metastatic tumor biopsies obtained at baseline and on-treatment (median duration of treatment eight weeks prior to on-treatment biopsy). Time after the last ZEN-3694 + enzalutamide dosing prior to the biopsy ranged from 3.5 to 24 hours. The limited sample size precluded ability to perform statistical analyses of change in expression by dose level. However, on gene set enrichment analyses looking at changes between on-treatment versus pre-treatment samples, there were strong indications of down-regulation of expression of MYC and AR-signaling on-treatment compared to baseline biopsies were detected, as well as down-regulation of BET-dependent genes previously identified in LnCaP cells treated with the I-BET762 BET inhibitor23 (Figure 2C).

Efficacy Analyses

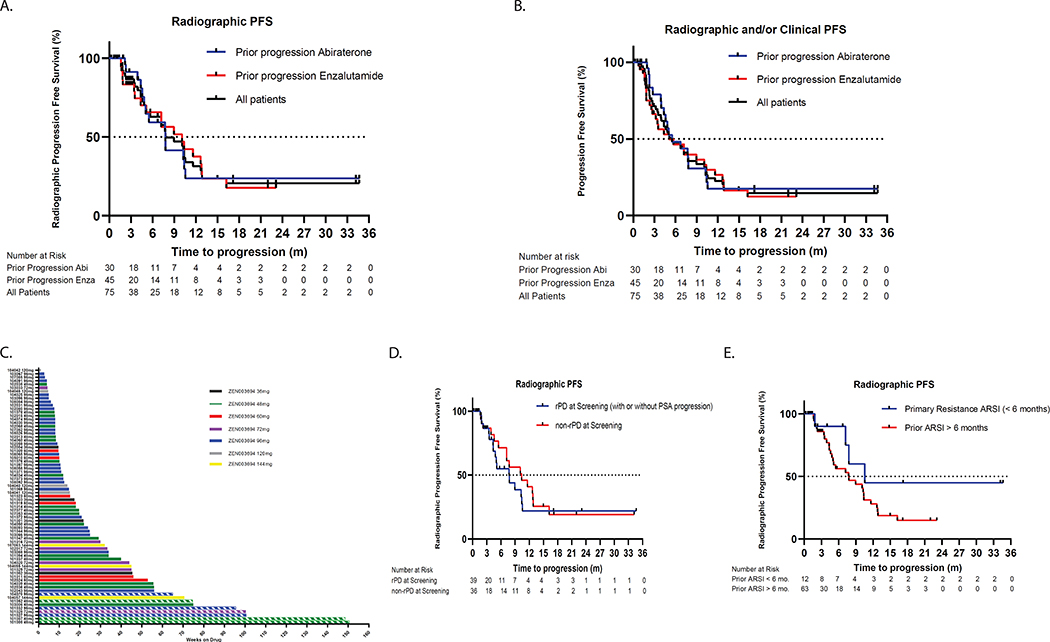

The median radiographic progression-free survival (rPFS) in the overall cohort was 9.0 months (95% CI: 4.6, 12.9), with 7.8 months for patients that had progressed on abiraterone (95% CI: 4.9, 10.6) and 10.1 months for patients that had progressed on enzalutamide (95% CI: 4.4, 12.9) (Figure 3A). Composite median radiographic or clinical progression-free survival was 5.5 months (95% CI: 4.0, 7.8) in the overall cohort, and 5.5 months (95% CI: 4.4, 7.8) and 5.1 months (95% CI: 3.2, 10.1) in those with prior progression on abiraterone and enzalutamide, respectively (Figure 3B). Thirteen (17%) and four (5%) patients remained on treatment for greater than 12 and 24 months without progression, respectively (Figure 3C). In patients with radiographic progression at the time of study entry, the median rPFS was 7.8 months (95% CI: 4.4, 10.6) (Figure 3D) and composite PFS was 4.8 months (95% CI: 3.5, 7.7). An analysis of the subset of patients with primary resistance to prior first-line AR targeted therapy (N = 12), defined by progression within 6 months of treatment initiation, demonstrated an on-treatment median rPFS of 10.6 months (95% CI (7.5, not reached) (Figure 3E). Using a more stringent cut-off of primary resistance of progression within 16 weeks of prior first-line AR targeted therapy (N = 5) likewise demonstrated prolonged median rPFS (median rPFS 22.4 months, 95% CI: 7.8, not reached) and composite PFS (median PFS 10.6 months, 95% CI: 4.0, not reached) in this subset of patients (Supplementary Figure 1A and 1B).

Figure 3. Radiographic progression-free survival and duration of treatment.

A. Kaplan-Meier curve demonstrating radiographic progression-free survival by PCWG2 criteria in all evaluable study participants (black curve), patients with prior enzalutamide progression (blue curve), or prior abiraterone progression (green curve). B. Kaplan-Meier curve demonstrating composite progression-free survival (time to first clinical or radiographic progression) in C. Swimmer’s plot showing duration of treatment, with color labels by ZEN-3694 dose level (hashed line = treatment ongoing). D and E. Kaplan-Meier curves showing radiographic progression-free survival in subsets of patients with radiographic progression or primary resistance to prior androgen signaling inhibitor, respectively.

Of the four exceptional responders who remained on treatment for greater than 24 months duration, three had radiographic progression at study entry, two had progressed on prior enzalutamide, and one of the four patients experienced an objective radiographic response on enzalutamide + ZEN-3694 (Supplementary Table 2).

Six patients (8%) experienced a greater than fifty percent decline from baseline in serum PSA by PCWG2 criteria (PSA50 response), including two patients with prior progression on enzalutamide monotherapy. All PSA responses were confirmed on repeat measurement. Four patients (5.3%) experienced a greater than ninety percent decline in serum PSA from baseline on study treatment. PSA50 responses were sustained in the majority of cases with median duration of PSA50 response of 21.1 months (95% CI (19.0, 23.2). The median PSA progression-free survival was 3.2 months (95% CI: 3.2, 5.1) in the overall study cohort and 3.2 months (95% CI: 2.8, 6.4) in those with PSA-only progression at study entry. There were no substantial differences with respect to rPFS, composite PFS, or PSA PFS noted between 48- and 96 mg- Dose Expansion cohorts.

Additionally, in a subset of patients (N = 21), there was a transient increase of > 2 ng/mL and 25% above baseline in serum PSA within the first 12 weeks of treatment with subsequent plateau in serum PSA level (Supplementary Figure 2A). Patients with transient PSA increase as defined above appeared to derive sustained clinical benefit with median rPFS of 10.1 months (95% CI: 5.6, 11.7). In contrast, patients whose serum PSA consistently rose beyond the 12 week time point (N = 21) experienced a median rPFS of 7.2 months (95% CI: 3.9, 9.0) (Supplementary Figure 2B).

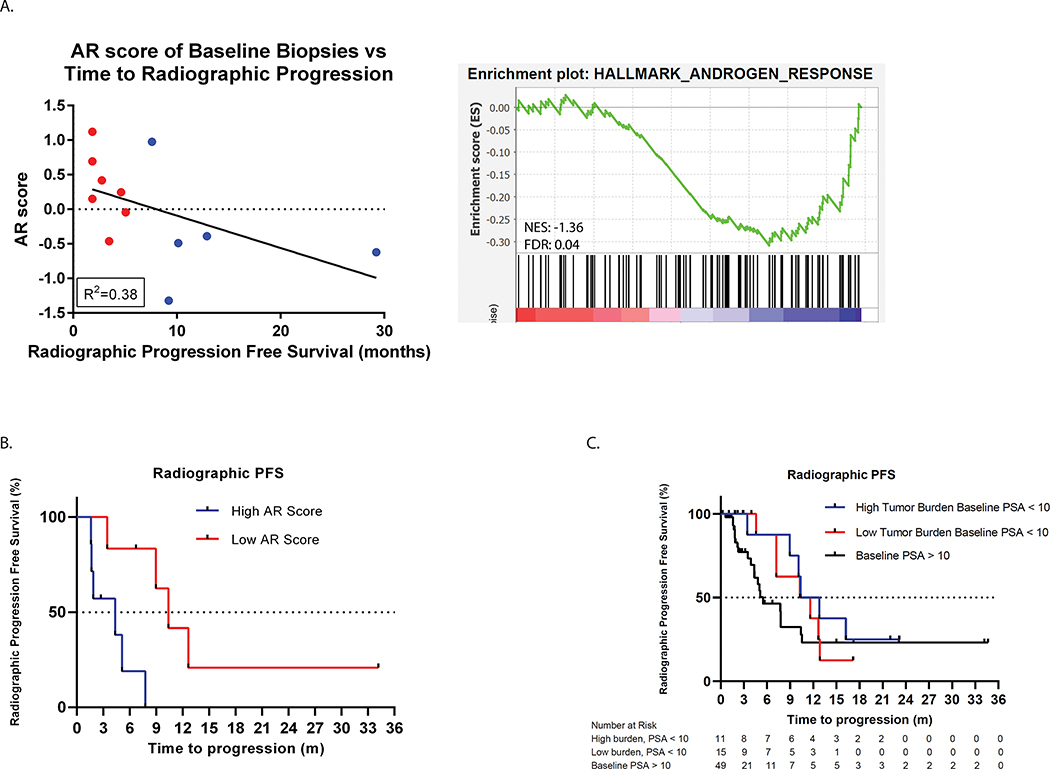

Predictors of Prolonged Clinical Benefit with ZEN-3694 + Enzalutamide

Exploratory analyses were performed with available genomic and transcriptional data from baseline tumor biopsies to evaluate association with subsequent time to progression on treatment. Interestingly, patients whose baseline metastatic tumor biopsies (N = 13) harbored lower canonical AR transcriptional activity, as assessed by 5-gene score25 as well as the HALLMARK_ANDROGEN_RESPONSE signature, experienced a longer median time to progression (TTP) (median TTP 19 vs. 45 weeks) (Figure 4A and B). In support of the notion that tumors with lower canonical AR activity might be more responsive to BET inhibition, we observed a trend towards prolonged time to progression amongst patients meeting clinical criteria for aggressive variant prostate cancer (e.g. low serum PSA < 10 ng/mL with concomitant high disease burden (visceral metastases and/or > 10 bone metastases)26. The median TTP in patients with aggressive variant disease was 11.6 months (95% CI: 7.2, 12.8) vs. 5.5 months (95% CI: 2.3, 10.6, p = 0.24) in those without aggressive variant clinical features at baseline (Figure 4C).

Figure 4. AR signaling score and clinical outcomes.

A. Lower AR activity level in baseline tumor biopsies is correlated with longer time on study (R2=0.38) using either the 5-gene AR score (left) or the HALLMARK_ANDROGEN_RESPONSE (right) signatures. For the hallmark signature, baseline gene expression of biopsies from patients with radiographic progression prior to 24 weeks vs. greater than 24 weeks were compared (FDR = 0.04). B. Kaplan-Meier curve showing significant increase in time to median radiographic progression free survival in patients with lower AR signaling compared to patients with higher AR signaling score (median rPFS 10.4 months in tumors with low AR score vs. 4.3 months in tumors with high AR activity). C. Patients with high tumor burden and lower baseline PSA levels (< 10 ng/mL) (blue curve) demonstrate longer PFS than patients with higher baseline PSA (> 10 ng/mL) levels.

DISCUSSION

Our results demonstrate that the pan-BET bromodomain inhibitor ZEN-3694 has acceptable tolerability and encouraging preliminary efficacy data in combination with enzalutamide in patients with mCRPC. The median radiographic progression-free survival in the overall cohort was 9 months, and over 10 months in those with prior progression on enzalutamide monotherapy. ZEN-3694 + enzalutamide treatment led to a 2–4 fold reduction in the expression of BET target genes including MYC, which was sustained throughout the 24 hour dosing interval. Based on the aggregate of the safety, efficacy, and evidence of robust down-regulation of expression of BET-dependent target genes, ZEN-3694 96 mg daily has been selected as the recommended phase 2 dose to move forward in further clinical development in combination with enzalutamide. The clinical and pharmacodynamic data provide clinical evidence that BET inhibition may be able to abrogate resistance mechanisms and re-sensitize patients to AR-signaling inhibitors.

The prolonged PFS observed in the current study in relevant subsets, including those with radiographic progression at study entry, primary resistance to prior AR targeted therapy, as well as those with prior progression on enzalutamide monotherapy, is consistent with an additive or potentially synergistic interaction between enzalutamide and ZEN-3694. The baseline characteristics of the study cohort are representative of other studies in the post-androgen receptor signaling inhibitor mCRPC setting, including nearly one-third of patients with intermediate or high risk disease by Halabi prognostic model27, and a quarter of which who required opioid analgesics at study entry. These features argue against the possibility of enrichment of better than average risk group contributing significantly to the prolonged PFS observed on treatment. Taken together, the data support a randomized study to evaluate for the magnitude of benefit of ZEN-3694 in combination with enzalutamide.

With the caveat of cross-trial comparisons, the median PFS observed with ZEN-3694 + enzalutamide in the current study compares favorably to outcomes observed with sequential AR targeting in mCRPC with abiraterone followed by enzalutamide, or vice versa, in prior studies. In the prospective SWITCH phase 2 crossover study, the median PFS of second line enzalutamide and abiraterone were 3.5 and 1.7 months, respectively.6 Similarly, median progression-free survival with second-line AR targeting therapy have been less than 8 months in most retrospective series.9 Caution should be applied to over-interpretation of these cross-trial comparisons, and a randomized trial will be necessary to assess the individual contribution of ZEN-3694 added to enzalutamide in mCRPC.

The PSA50 response rate with the combination of ZEN-3694 plus enzalutamide was less than 10% in the study, and median PSA progression-free survival was less than 4 months. Though this may reflect lack of additive benefit of ZEN-3694 in combination with enzalutamide, decline in serum PSA and PSA progression-free survival may not be the best metrics to gauge efficacy of BET bromodomain inhibitors including ZEN-3694. In fact, a subset of patients experienced transient early rises in serum PSA by week 8 of treatment, which were associated with longer time to progression. In addition, tumors harboring lower AR activity at baseline appeared to derive more clinical benefit from treatment. Finally, those with low serum PSA in relation to metastatic disease burden, a clinical profile consistent with small cell/neuroendocrine prostate cancer, may also have longer radiographic progression-free survival compared to those with higher baseline serum PSA levels. Though these observations are hypothesis-generating and require prospective validation, it raises the intriguing possibility that BET bromodomain inhibitors may restore dependency on AR-signaling in tumors that are less reliant on AR prior to BETi or that BETi is blocking important AR-independent survival mechanisms, such as MYC, which has been shown to be critical for BETi effects in CRPC.13,28,29 AR-independent mCRPC is becoming more prevalent with the earlier application of AR-signaling inhibitors, and is associated with shortened survival and unmet need to develop novel therapeutic approaches.30

The acceptable toxicity profile of ZEN-3694 in combination with enzalutamide stands in contrast to the results observed with several other recent BET inhibitors reported in the literature which have been limited by thrombocytopenia and GI toxicities.31,32 In the current study, there was substantially less thrombocytopenia observed. Gastrointestinal toxicities were not as prevalent or severe as prior studies and were manageable with early institution of anti-emetics and dose reductions, if necessary. The reasons underlying the potentially more favorable toxicity profile observed in current study, as compared with other BET inhibitors, may relate to patient factors such as excluding prior chemotherapy for mCRPC. Further, it is possible that a pharmacokinetic interaction with ZEN-3694 and enzalutamide may have accelerated production of the first-generation active metabolite ZEN-3791, which may have a more favorable toxicity profile. The differential toxicity compared with other BET inhibitors does not appear to relate to differences in potency, given the robust down-regulation of BETi target genes observed in the current study.

There were several limitations of the study, including the limited number of baseline and on-treatment paired biopsies precluding the ability to identify a consistent predictive biomarker with a high degree of statistical confidence. The non-randomized nature of the dose expansion portion of the study also limits our ability to draw definitive conclusions regarding the potential additive benefit of ZEN-3694, though evidence of contribution is provided by favorable comparison to contemporary controls from other studies as outlined above. AR-V7 splice variant status in circulating tumor cells, a validated resistance mechanism to AR targeted therapy that may be down-regulated with BETi treatment, was not reliably captured in this study in a sufficient number of patients to permit evaluation. Finally, there did not appear to be a relationship between dose level and efficacy outcomes, potentially related to fairly broad inter-patient variability in ZEN-3694 exposure, limited sample size, and limited single agent activity of ZEN-3694.

With the shift in application of potent AR targeted therapy in earlier castration-sensitive settings, there is an increasing medical need to develop therapies that reverse therapeutic resistance and restore dependency on AR signaling. The preliminary data provided by the Phase 1b/2 study of ZEN-3694 plus enzalutamide provides strong justification to further investigate in a prospective, randomized study.

Supplementary Material

Statement of Translational Relevance.

BET bromodomain inhibitors (BETi) demonstrate in vivo activity in enzalutamide-resistant prostate cancer models via down-regulation of bypass signaling pathways including MYC. Clinical translation of BETi as a therapeutic strategy in metastatic castration resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) has heretofore been limited by significant toxicity including risk of thrombocytopenia. In the current phase 1a/2b study of the pan-BETi ZEN-3694 in combination with enzalutamide in 75 patients with abiraterone and/or enzalutamide-resistant mCRPC, the combination was well tolerated without reaching a maximally tolerated dose. Less than 5% of patients experienced a grade ≥ 3 thrombocytopenia. Robust, dose-dependent, and sustained down-regulation of expression of BET inhibitor target genes including MYC was observed using a whole blood RNA assay. Encouraging efficacy was observed including a median radiographic progression-free survival of over 10 months in those with prior progression on enzalutamide monotherapy. Clinical benefit was particularly pronounced in high-risk subgroups including those with an aggressive variant clinical phenotype as well as those with lower androgen receptor (AR) transcriptional activity in baseline tumor biopsies. A randomized study is planned with ZEN-3694 at the recommended phase 2 dose of 96 mg orally once daily in combination with enzalutamide in mCRPC with prior progression on enzalutamide or abiraterone.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The financial support and study drug supply was provided by Zenith Epigenetics. R.A. received funding from the Prostate Cancer Foundation and the Department of Defense Prostate Cancer Research Program grant W81XWH1820039. W.A. is funded by NIH National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Support Grant (P30CA008748) and Prostate Cancer SPORE (P50CA092629), the Department of Defense Physician Research Award W81XWH-17-1-0124, and the Prostate Cancer Foundation. J.J.A. received funding from grant P50 CA097186. J.J.A is currently employed by the University of Michigan. FYF received funding from the Prostate Cancer Foundation.

Footnotes

Disclosures:

RA has received consulting income from Janssen Biotech, Merck, AstraZeneca; research funding to his institution from Zenith Epigenetics; honoraria for speaker’s fee from Dendreon and Clovis Oncology

MTS has received research funding to his institution from Janssen Biotech, AstraZeneca, Zenith Epigenetics, Pfizer, Madison Vaccines, and Hoffman-La Roche.

AP has received consulting income from Pfizer; founder and equity holder Athos Therapeutics; equity holder in Allogene, Urogen, and Clovis; serves on scientific advisory board for Attica Biosciences.

EC, SA, MS, LB, and SL are employed by drug manufacturer and sponsor Zenith Epigenetics, Ltd.

FYF has received research funding from Zenith Epigenetics; consulting income from Astellas, Blue Earth, Bayer, Clovis, Celgene, Janssen, Sanofi; and is co-founder of PFS Genomics.

WA has received consulting income from Clovis Oncology, Janssen Biotech, MORE Health, ORIC Pharmaceuticals, Daiichi Sankyo; research funding to his institution from AstraZeneca, Zenith Epigenetics, Clovis Oncology, and GlaxoSmithKline; honorarium from CARET

JJA has received consulting income from Janssen Biotech and Merck; honoraria for speaker’s fees from Astella.

REFERENCES

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, and Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 2020;70(1):7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ryan CJ, Smith MR, de Bono JS, et al. Abiraterone in metastatic prostate cancer without previous chemotherapy. N Engl J Med 2013; 368:138–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beer TM, Armstrong AJ, Rathkopf DE, et al. Enzalutamide in metastatic prostate cancer before chemotherapy. N Engl J Med 2014; 371: 424–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fizazi K, Tran N, Fein L, et al. Abiraterone acetate plus prednisone in patients with newly diagnosed high-risk metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer (LATITUDE): final overall survival analysis of a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncology 2019;20:686–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chi KN, Agarwal N, Anders B, et al. Apalutamide for metastatic castation-sensitive prostate cancer. New Engl J Med 2019:381:13–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khalaf DJ, Annala M, Taavitsainen S, et al. Optimal sequencing of enzalutamide and abiraterone acetate plus prednisone in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: a multicentre, randomised, open-label, phase 2, crossover trial. Lancet Oncology 2019;20:1730–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Attard G, Borre M, Gurney H, et al. Abiraterone alone or in combination with enzalutamide in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer with rising prostate-specific antigen during enzalutamide treatment. J Clin Oncol 2018;36:2639–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Bono JS, Chowdhury S, Feyerabend S, et al. Antitumour activity and safety of enzalutamide in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer previously treated with abiraterone acetate plus prednisone for ≥ 24 weeks in Europe. European Urology 2018;74:37–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mori K, Miura N, Mostafaei H, et al. Sequential therapy of abiraterone and enzalutamide in castration-resistant prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prostate Cancer and Prostatic Diseases 2020. [published online 09 March 2020]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morris MJ, Heller G, Bryce AH, et al. Alliance A031201: a phase III trial of enzalutamide versus enzalutamide, abiraterone, and prednisone for metastatic castration resistant prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol 2019;37, no. 15_suppl (May 20, 2019) 5008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Antonarakis ES, Lu C, Wang H, et al. AR-V7 and resistance to enzalutamide and abiraterone in prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 2014;371:1028–1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Montgomery RB, Mostaghel EA, Vessella R, et al. Maintenance of intratumoral androgens in metastatic prostate cancer: a mechanism for castration-resistant tumor growth. Cancer Res 2008;68:4447–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Quigley DA, Dang HX, Zhao SG, et al. Genomic Hallmarks and Structural Variation in Metastatic Prostate Cancer. Cell 2018;175:889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aggarwal R, Huang J, Alumkal JJ, et al. Clinical and Genomic Characterization of Treatment-Emergent Small-Cell Neuroendocrine Prostate Cancer: A Multi-institutional Prospective Study. J Clin Oncol 2018;36:2492–2503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arora VK, Schenkein E, Murali R, et al. Glucocorticoid receptor confers resistance to antiandrogens by bypassing androgen receptor blockade. Cell 2013;155:1309–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shah N, Wang P, Wongvipat J, et al. Regulation of the glucocorticoid receptor via a BET-dependent enhancer drives antiandrogen resistance in prostate cancer. Elife 2017;6:e27861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mertz JA, Conery AR, Bryant BM, et al. Targeting MYC dependence in cancer by inhibiting BET bromodomains. PNAS 2011;108:16669–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Attwell S, Jahagirdar R, Norek K, et al. Preclinical characterization of ZEN-3694, a novel BET bromodomain inhibitor entering phase I studies for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) In CANCER RESEARCH 2016; (Vol. 76). 615 CHESTNUT ST, 17TH FLOOR, PHILADELPHIA, PA: 19106–4404 USA: AMER ASSOC CANCER RESEARCH. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scher HI, Halabi S, Tannock I, et al. Design and end points of clinical trials for patients with progressive prostate cancer and castrate levels of testosterone: recommendations of the Prostate Cancer Clinical Trials Working Group. J Clin Oncol 2008; 26:1148–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tsujikawa L, Norek K, Calosing C, et al. Abstract LB-038: Preclinical development and clinical validation of a whole blood pharmacodynamic marker assay for the BET bromodomain inhibitor ZEN-3694 in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer patients. Cancer Research 2017;77, Issue 13 Supplement, pp. LB–038. [Google Scholar]

- 21.The Molecular Signatures Database v7.0 (Broad Institute). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu P, Ramachandran S, Ali Seyed M, et al. Sex-determining region Y box 4 is a transforming oncogene in human prostate cancer cells. Cancer research 2006;66(8):4011–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wyce A, Degenhardt Y, Bai Y, et al. Inhibition of BET bromodomain proteins as a therapeutic approach in prostate cancer. Oncotarget 2013;4:2419–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aggarwal R, Abida W, Schweizer M, et al. CTo95: A phase Ib/IIa study of the BET bromodomain inhibitor ZEN-3694 in combination with enzalutamide in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC). In Proceedings of the AACR Meeting; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miao L, Yang L, Li R, Rodrigues DN, Crespo M, Hsieh JT, … Raj GV (2017). Disrupting Androgen Receptor Signaling Induces Snail-Mediated Epithelial-Mesenchymal Plasticity in Prostate Cancer. Cancer research, 77(11), 3101–3112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Corn PG, Heath EI, Zurita A, et al. Cabazitaxel plus carboplatin for the treatment of men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancers: a randomised, open-label, phase 1–2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2019;20(10):1432–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Halabi S, Lin C, Kelly WK, et al. Updated prognostic model for predicting overall survival in first-line chemotherapy for patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:671–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coleman DJ, Gao L, Schwartzman J, et al. Maintenance of MYC expression promotes do novo resistance to BET bromodomain inhibition in castration-resistant prostate cancer. Science Reports 2019;9:3823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Coleman DJ, Gao L, King CJ, et al. BET bromodomain inhibition blocks the function of a critical AR-independent master regulatory network in lethal prostate cancer. Oncogene 2019;38:5658–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aggarwal R, Huang J, Alumkal JJ, et al. Clinical and genomic characterization of treatment-emergent small cell neuroendocrine prostate cancer: a multi-institutional prospective study. J Clin Oncol 2018;36:2942–2503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Piha-Paul S, Hann CL, French CA, et al. Phase 1 study of molibresib (GSK525762), a bromodomain and extra-terminal domain protein inhibitor, in NUT carcinoma and other solid tumors. JNCI Cancer Spectrum [published online 06 November 2019]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Patel MR, Garcia-Manero G, Paquette R, et al. Phase 1 dose escalation and expansion study to determine safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of the BET inhibitor FT-1101 as a single agent in patients with relapsed or refractory hematologic malignancies. Blood, 2019;134(suppl 1):3907. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.