Abstract

Background:

The mutations of KCNMA1 BK type K+ channel have been identified in patients with various movement disorders. The underlying pathophysiology and corresponding therapeutics are lacking.

Objective:

To report our clinical and biophysical characterizations a novel de novo KCNMA1 variant, as well as an effective therapy for the patient’s dystonia-atonia spells.

Methods:

Combination of phenotypic characterization, therapy and biophysical characterization of the patient and her mutation.

Results:

The patient had more than one hundred dystonia-atonia spells per day with mild cerebellar atrophy. She also had autism spectrum disorder, intellectual disability, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Whole exome sequencing identified a heterozygous de novo BK N536H mutation. Our biophysical characterization demonstrates that N536H is a gain-of-function (GOF) mutation with markedly enhanced voltage dependent activation. Remarkably, administration of dextroamphetamine completely suppressed the dystonia-atonia spells.

Conclusions:

BK N536H is a GOF that causes dystonia and other neurological symptoms. Our stimulant therapy opens a new avenue to mitigate KCNMA1-linked movement disorders.

Keywords: movement disorders, dystonia, KCNMA1, BK channelopathy, stimulants

Introduction

BK also known as Slo1 or KCa1.1 channel is a special type of K+ channel with dual sensitivity to membrane voltage and intracellular Ca2+.1–5 Consistent with its important physiological functions in neurons, 13 mutations of KCNMA1 gene that encodes the BK pore-forming α subunit have been identified in human patients.6–12 Only two have been reported as gain-of-function (GOF) and the others are loss-of-function mutations (LOF). The first BK channelopathy was identified from a family of patients with generalized epilepsy (n=4), paroxysmal nonkinesigenic dyskinesia (PNKD, n=7) or both (n=5).7 Biophysical characterizations demonstrated that the mechanism underlying the D434G mutation is a GOF mutation involving markedly enhanced sensitivity to Ca2+ without affecting its voltage dependence.7, 13–15 Here we report a new de novo KCNMA1 variant N536H from a patient with novel phenotype. Distinct from D434G, the N536H GOF mutation promotes BK channel activation by enhancing its voltage dependence with intact Ca2+ sensing. Interestingly, administration of dextroamphetamine has remarkably and consistently suppressed dystonia and atonia spells.

Subject and Methods

Patient.

Retrospective review of the patient’s findings.

Electrophysiology and Data Analysis.

Electrophysiology and data analysis were the same as our previous publication.13 Briefly, wildtype (WT), N471H and D369G in the mbr5 splice variant of mslo116 (equivalent of N536H and D434G in hSlo1, respectively) were expressed in Xenopus oocytes or HEK293T cells. BK current was recorded by inside-out or outside-out patches as indicated and the conductance-voltage (G-V) relationship was obtained by measuring tail current amplitudes at indicated voltages. Monod-Wyman-Changeux model (MWC model) was used to determine Ca2+ binding affinity. Estimates of the standard error of the mean (SEM) for MWC parameters were determined by individually fitting data from separate experiments. The sensitivity analysis of MWC parameters was included in Supplementary Fig. 1.

Results

Case Descriptions

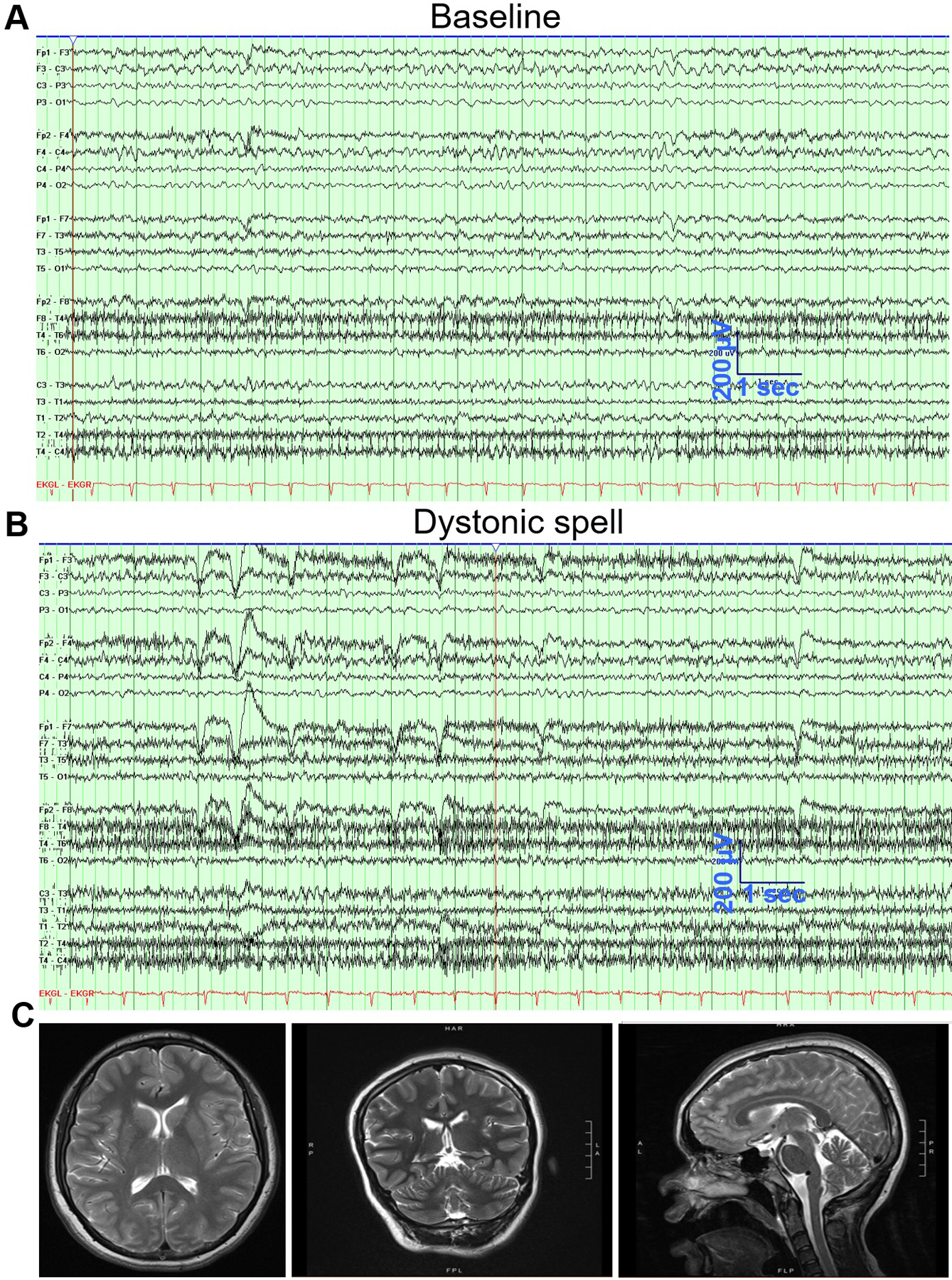

Patient is a 25 yo female diagnosed to have had autism spectrum disorder, dystonia (Supplementary Video 1), and intellectual disability. She said her first word and walked only at the age of two years. At that age she also developed episodes of diffuse loss of tone with dystonic posturing. These episodes lasted 15–20 seconds each and occurred about 100 times daily. The episodes consisted of her falling limp with associated tightened fists, stiffening of the upper extremities, and associated head turning. At times the spells would include a laugh. MRI, EEG and a study for narcolepsy were negative. Over the following years the dystonic component became more prominent. An extensive metabolic workup was negative except for low 5-hydroxindoleacetic acid and homovanillic acid in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Whole exome sequencing demonstrated a heterozygous de novo c.1606A>C N536H mutation in the KCNMA1 gene, resulting in N536H mutation in the BK type Ca2+ activated K+ channel. At four years old, Video EEG demonstrated two spells of slurring and becoming limp. The EEG during and outside these spells was normal. Video EEG at age 14 years demonstrated only diffuse background slowing. At 15 years of age, the patient had 51 episodes documented on video EEG all of which were without EEG correlate. Background showed occasional bifrontal sharps and bifrontal slowing. Video EEG at 18 years of age showed rare generalized spike and wave and rare bifrontal sharps, left more than right with unclear significance and diffuse slowing (Fig. 1A, 1B). There were numerous clinical dystonic events none of which had any EEG correlates while MRI showed mild cerebellar atrophy (Fig. 1C).

FIGURE 1.

Electroencephalogram (EEG) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the Case at the age of 18 years. (A) EEG during baseline in wakefulness showing mild diffuse slowing more prominent anteriorly and on the left. Some of the frontal slow waves are sharply contoured. (B) EEG during a dystonic spell showing increase in muscle activity but with no epileptic activity. (C) MRI of the Case shows mild signs of cerebellar atrophy.

Since the patient was initially thought to be having seizures she received multiple antiepileptic drug trials as well as other therapies for potential narcolepsy. Unsuccessful trials included ethosuximide, valproate, phenobarbital, zonisamide, leviteracetam, temazepam, clonazepam, ketogenic diet, gabapentin, carbamazepine, lamotrigine, memantine, and modafinil. Because she was also diagnosed to have attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), the patient was placed, at age 8 years, on dextroamphetamine. This therapy, at doses of 15 mg/day, was associated with complete control of her dystonic episodes from more than hundred per day to none, except on the days when she missed doses because she ran out of, or did not take, the medication. In the absence of dextroamphetamine, her spells recurred initially 5–10 per day and then increased to about 200 per day over the following few days if she continued not to receive the medication. This recurrence has happened multiple times in her history. She thus continues to be on 15 mg of dextroamphetamine daily.

Biophysical characterization of the BK channel mutation.

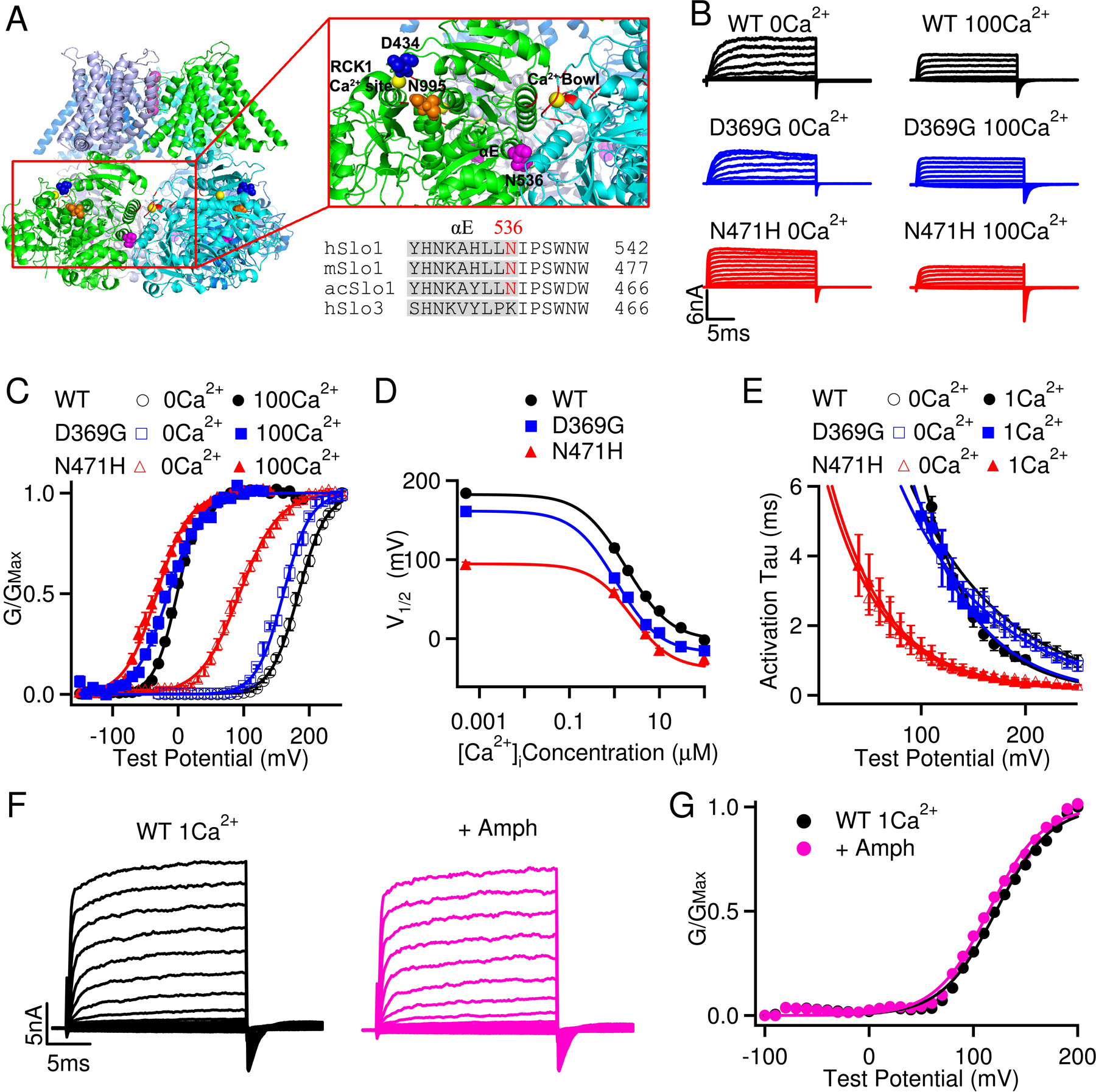

The residue Asn 536 (N536) in human Slo1 (hSlo1) channel is highly conserved in BK channels of different species (Fig. 2A). Different from the GOF mutation D434G that resides in the vicinity of the RCK1 Ca2+ site,7 N536 is located at the interface of two adjacent subunits, distal from the Ca2+ bowl and the RCK1 Ca2+ binding sites (Fig. 2A). To investigate the effects of N536H on BK channel activation, we characterized the biophysical properties of N471H of mouse BK (mSlo1) channels (equivalent of N536H in hSlo1) (Fig. 2B). We found that N471H dramatically shifts the G-V relationship toward hyperpolarizing voltages in all Ca2+ concentrations tested, with −89.9 mV shift of the half-maximal activation voltage (V1/2) in 0 [Ca2+]i and −30.6 mV in 100 μM [Ca2+]i (Fig. 2C, 2D). The shifts indicate that the mutation increases BK channel activity at any given physiological voltage. The mutation has not obvious effect on the G-V slope, indicating that N471H enhances BK channel activation without affecting voltage sensitivity. N471H also greatly accelerates BK channel activation kinetics (Fig. 2B, 2E). Fitting the G-V relations in different [Ca2+]i with the MWC model17 suggests that Ca2+ binds to the mutant channel with a similar affinity as to the WT channel at the closed conformation but with a lower affinity at the open conformation (MWC model fitting parameters for WT: L(0)=(6.2 ± 1.3)x104, z=1.6 ± 0.1, KC=8.2 ± 0.7 μM, KO=0.50 ± 0.04 μM; for D369G: L(0)= (5.5 ± 1.9)x103, z=1.3 ± 0.1, KC=3.5 ± 0.4 μM, KO=0.38 ± 0.05 μM and for N471H: L(0)=59 ± 150, z=1.06 ± 0.03, KC=6.6 ± 1.7 μM, KO=1.43 ± 0.29 μM). N471H reduced L(0) by ~1,000 times as compared to the WT, while the mutation altered Ca2+ affinities only less than 2 folds. These results quantitatively reflect the characteristics shown in current recordings (Fig. 2B–E) such that the GOF phenotype of N471H mainly stems from enhanced voltage dependence.13 Our current study thus identified a new molecular mechanism that a GOF BK channel mutation N536H on voltage dependent activation leads to a series of neurological symptoms in the patient. Interestingly, extracellular application of 10 μM amphetamine does not inhibit BK channel activation (Fig. 2F, 2G), suggesting that the therapeutic effect of amphetamine on suppressing the patient’s dystonia spells likely stems from its indirect effect on the dopamine system.

FIGURE 2:

N536H is a gain-of-function mutation of BK channel with markedly enhanced voltage sensitivity. (A) N536 in human BK channel (hSlo1) is conserved in the BK channels of different species and is located at the C-terminus of the αE helix in the RCK1 domain (the Ca2+ bound Aplysia californica Slo1 structure, PDB: 5TJI). Ca2+ ions are shown as yellow balls; the Ca2+ binding residues in the RCK1 site and the Ca2+ bowl are shown in red; N536, D434 and N995 are shown as purple, blue and orange spheres, respectively. h, human; m, mouse, ac, Aplysia californica. (B) Macroscopic currents of wildtype (WT), D369G (equivalent of D434G in hSlo1) and N471H (equivalent of N536H in hSlo1) mutant mSlo1 BK channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes. The raw traces were elicited by voltage pulses from −30 to 250 mV in 0 [Ca2+]i and from −200 to 100 mV in 100 μM [Ca2+]i with 20 mV increments. The voltages before and after the pulses were −50 and −80 mV, respectively. Notice the difference in voltage protocol for currents in 0 and 100 μM [Ca2+]i. The voltage after the testing pulses was −120 mV for N471H in 100 μM [Ca2+]i. (C) Conductance-voltage (G-V) curves for the WT, D369G, and N471H channels in 0 [Ca2+]i and 100μM [Ca2+]i. Solid lines are fits to the Boltzmann relation with V1/2 and slope factor for WT at 0 [Ca2+]i: 183.4 ± 3.2 mV and 20.6 ± 2.9 mV and at 100μM [Ca2+]i: −2.0 ± 1.4 mV and 17.6 ± 1.8 mV; for D369G at 0 [Ca2+]i: 161.0 ± 2.2 mV and 20.5 ± 3.5 mV and at 100μM [Ca2+]i: −15.2 ± 2.9 mV and 25.2 ± 4.5 mV; for the N471H at 0 [Ca2+]i: 93.5 ± 5.6 mV and 30.1 ± 4.9 mV and at 100μM [Ca2+]i: −32.6± 5.1 mV and 24.7 ± 4.4 mV. (D) Plots of V1/2 vs [Ca2+]i to evaluate the Ca2+- and voltage-dependence of the WT, D369G and N471H mSlo1 channels. V1/2 is the voltage where the open probability is half maximal, and the relation is computed based on the fittings of G-V relations with the Monod-Wyman-Changeux (MWC) model PO=1/(1+L0*exp(−zeoV/kT)*((1+C/KC)/ (1+C/KO))^4), where PO is the channel’s open probability, L0 is the steady-state equilibrium constant from open to close channels ([C0]/[O0]) without Ca2+ binding at 0 mV and C is free Ca2+ concentration in solution, KC and KO are the dissociation constants of Ca2+ in the closed and open states, respectively. (E) The activation time courses (Tau) at various voltages. Tau values were obtained by fitting the current traces with a single exponential function for both WT, D369G and N471H channels at 0 [Ca2+]i and 1μM [Ca2+]i. The solid lines are fittings of the data with an exponential function. (F) Macroscopic currents of WT mSlo1 BK channels expressed in HEK293T cells in the absence and presence of 10 μM amphetamine perfused from extracellular side. The raw traces were elicited by voltage pulses from −100 to 200 mV in 1μM [Ca2+]i by outside-out patches. (G) G-V relationship for the WT channels in the absence and presence of 10 μM amphetamine. Solid lines are fits to the Boltzmann relation with V1/2 122.7 ± 4.2 mV and 119.2 ± 3.9 mV in the absence and presence of amphetamine, respectively.

Discussion

Here we report a new KCNMA1 GOF mutation c.1606A>C N536H on voltage dependent activation from a patient with severe dystonia spells that were well controlled by dextroamphetamine. Other than dystonia spells, our patient also has had ADHD, autism spectrum disorder and intellectual disability. Interestingly, these neurological defects were not reported from the 13-patient family carrying the heterozygous GOF mutation D434G.7 Although our patient had rare epileptiform activity after the age of 15 years, none of her tens of spells recorded on Video EEG had any EEG correlate (Fig. 1B) and she failed all administered antiepileptic medications. The patients with D434G mutation had paroxysmal nonkinesigenic dyskinesia-3 with or without epilepsy.7 Thus, other than the similarity of occurrence of dyskinesia, our patient exhibits differences in her symptoms from patients with D434G mutation. This suggests that the two GOF KCNMA1 mutations may employ different pathophysiological mechanisms to induce distinct symptoms. Indeed, our biophysical characterizations suggest that N536H and D434G enhance BK channel activation through distinct molecular mechanisms (Fig. 2). N536H enhances BK channel activation by promoting voltage dependent activation without affecting its Ca2+ dependent activation. D434G, on the other hand, specifically enhances BK channel Ca2+ activation with minimal alterations in its voltage activation (Fig. 2).13, 15 Our previous study showed that D434G, which is spatially close to the RCK1 Ca2+ binding site, increases Ca2+ sensitivity by enhancing the allosteric coupling between Ca2+ binding and channel gate opening.7, 13 In contrast, N536 is located at the cytosolic αE helix, at the interface between two neighboring subunits (Fig. 2A), suggesting that N536H may enhance BK channel voltage dependent activation through alteration of the allosteric coupling between the cytosolic C-terminal domain and the voltage sensor domain in cell membrane.18

Another de novo GOF variant in KCNMA1 (c.2984 A > G (p.N995S) was recently reported in the patients from two independent families, who had absence epilepsy in early childhood but did not develop paroxysmal dyskinesia.8 Subsequent biophysical characterization showed that N995S, similar to N536H, also specifically increases voltage sensitivity without affecting Ca2+-dependent activation.8, 19 N995 is located at the C-terminal end of the channel and is spatially distal from N536 and the voltage sensor (Fig. 2A). It is not clear how N536H and N995S allosterically enhance BK channel voltage dependent activation at molecular level. It is also intriguing that even though both N536H and N995S specially promote BK channel voltage dependent activation, the patients carrying these variants do not exhibit identical symptoms. Among the two N995S patients, only one patient showed developmental delay. Both patients did not exhibit signs of movement disorders, autism spectrum disorder, intellectual disability and ADHD. These questions impose urgent need to further dissect the pathophysiological mechanisms of the BK channel GOF mutations using in vitro assays and in vivo animal models.

Remarkably, when our patient was treated for her ADHD with daily administration of the stimulant dextroamphetamine, this therapy effectively suppressed her dystonia-atonia spells. Our in vitro experiment shows that amphetamine does not inhibit BK channel activation (Fig. 2F, 2G). Given a previous study shows that methamphetamine can reduce BK channel surface expression in dopaminergic neurons,20 amphetamine likely exerts its effect through the dopamine system to curb the patient’s dystonia spells. Future studies are needed to uncover the neurological mechanism of dextroamphetamine in controlling such spells and examine whether administration of stimulants could be a general therapeutic option to treat other KCNMA1-linked channelopathies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We are grateful to Drs. William Wetsel and Ping Dong for their generous help to this work. This work was supported by grants from the Duke Institute for Brain Sciences (to H.Y. & M.A.M.), a donation from CureAHC Foundation (to M.A.M.) and NIH-R01 HL142301 (to J.C.).

Footnotes

Potential Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

References:

- 1.Lee US, Cui J. BK channel activation: structural and functional insights. Trends Neurosci 2010;33(9):415–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhou Y, Yang H, Cui J, Lingle CJ. Threading the biophysics of mammalian Slo1 channels onto structures of an invertebrate Slo1 channel. The Journal of general physiology 2017;149(11):985–1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salkoff L, Butler A, Ferreira G, Santi C, Wei A. High-conductance potassium channels of the SLO family. Nature reviews Neuroscience 2006;7(12):921–931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Contreras GF, Castillo K, Enrique N, et al. A BK (Slo1) channel journey from molecule to physiology. Channels 2013;7(6):442–458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang H, Zhang G, Cui J. BK channels: multiple sensors, one activation gate. Frontiers in physiology 2015;6:29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bailey CS, Moldenhauer HJ, Park SM, Keros S, Meredith AL. KCNMA1-linked channelopathy. The Journal of general physiology 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Du W, Bautista JF, Yang H, et al. Calcium-sensitive potassium channelopathy in human epilepsy and paroxysmal movement disorder. Nature genetics 2005;37(7):733–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li X, Poschmann S, Chen Q, et al. De novo BK channel variant causes epilepsy by affecting voltage gating but not Ca(2+) sensitivity. European journal of human genetics : EJHG 2018;26(2):220–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liang L, Li X, Moutton S, et al. De novo loss-of-function KCNMA1 variants are associated with a new multiple malformation syndrome and a broad spectrum of developmental and neurological phenotypes. Hum Mol Genet 2019;28(17):2937–2951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tabarki B, AlMajhad N, AlHashem A, Shaheen R, Alkuraya FS. Homozygous KCNMA1 mutation as a cause of cerebellar atrophy, developmental delay and seizures. Human genetics 2016;135(11):1295–1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yesil G, Aralasmak A, Akyuz E, Icagasioglu D, Uygur Sahin T, Bayram Y. Expanding the Phenotype of Homozygous KCNMA1 Mutations; Dyskinesia, Epilepsy, Intellectual Disability, Cerebellar and Corticospinal Tract Atrophy. Balkan medical journal 2018;35(4):336–339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang ZB, Tian MQ, Gao K, Jiang YW, Wu Y. De novo KCNMA1 mutations in children with early-onset paroxysmal dyskinesia and developmental delay. Movement disorders : official journal of the Movement Disorder Society 2015;30(9):1290–1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang J, Krishnamoorthy G, Saxena A, et al. An epilepsy/dyskinesia-associated mutation enhances BK channel activation by potentiating Ca2+ sensing. Neuron 2010;66(6):871–883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Diez-Sampedro A, Silverman WR, Bautista JF, Richerson GB. Mechanism of increased open probability by a mutation of the BK channel. Journal of neurophysiology 2006;96(3):1507–1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang B, Rothberg BS, Brenner R. Mechanism of increased BK channel activation from a channel mutation that causes epilepsy. The Journal of general physiology 2009;133(3):283–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Butler A, Tsunoda S, McCobb DP, Wei A, Salkoff L. mSlo, a complex mouse gene encoding “maxi” calcium-activated potassium channels. Science 1993;261(5118):221–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cox DH, Cui J, Aldrich RW. Allosteric gating of a large conductance Ca-activated K+ channel. The Journal of general physiology 1997;110(3):257–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang G, Geng Y, Jin Y, et al. Deletion of cytosolic gating ring decreases gate and voltage sensor coupling in BK channels. The Journal of general physiology 2017;149(3):373–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moldenhauer HJ, Matychak KK, Meredith AL. Comparative Gain-of-Function Effects of the KCNMA1-N999S Mutation on Human BK Channel Properties. Journal of neurophysiology 2019: 10.1152/jn.00626.02019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin M, Sambo D, Khoshbouei H. Methamphetamine Regulation of Firing Activity of Dopamine Neurons. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 2016;36(40):10376–10391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.