Abstract

Background

The purpose of our study was to explore the feasibility of 3D printing navigation template used in total hip arthroplasty (THA) for adult developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH).

Materials and Methods

25 patients who received THA for DDH from February 2014 to May 2018 were randomized into the control or intervention group. Of these patients, 12 received THAs assisted with 3D printing navigation templates, 13 THAs underwent THAs without navigation templates. The mean follow-up was 1.6 (range, 1.2–3.8) years. Clinical scores and radiographic results were evaluated for two groups.

Results

Operating time, intra- and postoperative hemorrhage and Harris Hip Score (HHS) at 6 months postoperatively in the 3D printing group were better than those for patients in the conventional hip replacement group, while infection and implant loosening were 0 in the two groups. There were no significant differences in anteversion angle, abduction angle and the distance from rotation center to the ischial tuberosity line in 3D printing group as compared to the normal side. The abduction angle and the distance from rotation center to the ischial tuberosity line were significantly different between the two sides in the traditional group.

Conclusion

Application of the 3D printing template for THA with DDH can facilitate the surgical procedure and create an ideal artificial acetabulum placement.

Keywords: 3D printing technology, Total hip arthroplasty, Developmental dysplasia of the hip, Navigation template

Introduction

Adult developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH), the leading cause of secondary osteoarthrosis [1, 2], has a femoral head dislocation and acetabular developmental dysplasia. Most patients eventually have to undergo total hip arthroplasty (THA), which provides reliable pain relief and functional improvement to the hip [3, 4]. Performing THA in severe DDH presents many challenges to the surgeon because of the extensive distortions to the native anatomy. DDH patients may have a shallow acetabulum, a straight narrow femoral canal, and associated circumferential soft-tissue deformities [5], as for the true acetabulum, it is small; the anterior wall is relatively thin and the amount of bone is less; the posterolateral wall is very thick [6]. For Crowe III/IV DDH, it is challenging to identify and locate the true acetabulum during the operation. If the acetabular prosthesis is placed improperly, the prosthesis will be easy to loosen due to the lack of support [7]. Traditional total hip arthroplasty does not adequately consider individual difference and often leads to bias in the placement of prosthesis [8, 9]. The precise placement and size selection of cup depend mainly on the experience of the surgeon, so detailed preoperative plans as well as intraoperative techniques are indispensable and any kind of mistakes will affect the surgical results. According to the requirements of precision medicine, a kind of precise and simple surgical procedure is eagerly needed.

Rapid prototyping (RP) technology, an emerging industrial technology, has been developed in the medical field in combination with reverse engineering technology, which enables the precise, individualized treatment. It is especially applicable to DDH with different anatomy morphologies. With detailed preoperative parameter measurement and surgical planning, 3D printing navigation template can effectively reduce errors due to inexperience and poor surgical techniques. Currently, intraoperative guide plates are applied in internal fixation screws and plates, high tibia osteotomy, and total knee arthroplasty [10–12]. The aim of this study was to demonstrate that the utilization of 3D printing guide during complex total hip in DDH improving the radiological and clinical outcomes.

Material and Methods

This randomized, controlled trial was performed from February 2014 to May 2018 in our hospital. Informed consent was obtained from all patients and the study was approved by the ethics committee of The Second Affiliated Hospital of Soochow University. There were no potential conflicts of the study. DDH patients who underwent THA were approached for the study. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) primary THA, (2) single DDH, (3) surgery without osteotomy, (4) the same operators. The exclusion criteria were: (1) born structural abnormality of contralateral acetabulum and (2) Crowe type I. 25 patients enrolled in our study were randomized into the control or intervention group. There were 4 males and 22 females, aged from 40 to 75 years with an average of 61.7 years. The 25 DDH cases included 5 cases of Crowe type II, 14 cases of Crowe type III and 6 cases of Crowe type IV. 12 cases of them underwent THA with the 3D printing navigation plate, the remaining 13 cases underwent the same surgery without the aid of navigation templates. All patients were treated with THA by the same operators. There was no significant difference in terms of gender, age, and Crowe classification between the groups (Table 1). Follow-up was 1.2–3.8 years, with a mean of 1.6 years. A surgeon blindly assessed the postoperative outcomes of the patients.

Table 1.

Comparison of general information relating to the template-guided group and traditional operation group. (M = male; F = female; L = left; R = right)

| Age | Gender | Side | Crowe classification | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Years | M | F | L | R | I | II | III | IV | |

| 3D printing group (n = 12) | 59.8 ± 11.1 | 2 | 10 | 8 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 6 | 4 |

| Traditional operation group (n = 13) | 65.5 ± 10.8 | 2 | 11 | 10 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 8 | 3 |

| Value | P = 0.246 | P = 0.93 | P = 0.568 | P = 0.823 | |||||

3D Printing

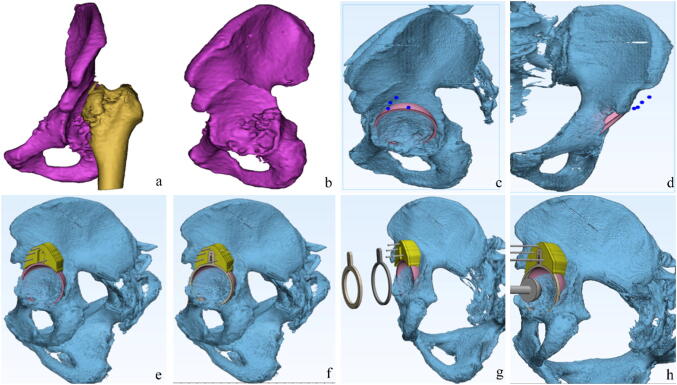

DICOM data obtained by CT scan of patient's pelvis were imported into Mimics15.0 software (Materialise, Leuven, Belgium) to produce a 3D reconstruction of the pelvis (Fig. 1). With the reference to the contralateral acetabulum center, the true acetabulum at the ill side was identified, the cup angle was set according to the contralateral acetabular angle, and the size of the acetabular cup would not break through the anterior and posterior walls of the affected true acetabulum. A ring parallel to the rime of the acetabular cup was designed, which was 2 mm larger than the diameter of the cup, this ring represented the position and size of the cup. The irregular bone surface of the false acetabulum was used as a bony landmark and the base template with reverse modeling was designed to fit the landmark. The base and the ring were detachable with a card slot (Fig. 1). The data were saved as STL format and loaded into the 3D printer, while the template and pelvis model were produced using the fused deposition molding (FDM) method of RP technology. The printing material was polylactide.

Fig. 1.

Preoperative design and template preparation. a, b DICOM data were imported into Mimics software for 3D reconstruction. The femur was removed. c, d The true acetabulum was identified according to the contralateral side, the cup size and angle were also designed. e The base was designed with reverse modeling which matched with the false acetabulum. f The ring was designed to fall on the same level of the cup and 2 mm larger than the diameter of the cup, the base and the ring were detachable with a card slot. g The concentric rings growing in size could be designed, if the osteophytes were too many to put the final ring. h The reamer was at the center of the ring

Operation

Simulated operation was performed on the pelvis model (Fig. 2). The surgeon who participated in the design of the guide performed all operations via a direct lateral approach. The soft tissue surrounding the false acetabulum was cleaned up to expose the bone structure and the base of the guide was completely matched with the false acetabulum and fixed by 3 K-wires. The ring was installed into the card slots on the base, the ring pointed to the true acetabulum, then the acetabular reamer was placed at the center of the ring to shape the prosthetic shell. When the reamer diameter was 2 mm smaller than that of the ring, the guide was taken off and the Trident acetabular component (Stryker; Mahwah, NJ) was placed in the same direction as the ring (Fig. 3). Followed by the completion of acetabular processing, the femur side was treated routinely until the THA was completed (Fig. 4).

Fig. 2.

Simulating operation. a 3D printing guide plate components. b The plate was installed with Kirschner wire. c, d The acetabulum was reamed step by step, the reamer was parallel to and at the center of the ring

Fig. 3.

Operation. a The ring was pointed to the true acetabulum. b The acetabulum was stepwise reamed

Fig. 4.

Preoperative and postoperative X-ray

Clinical and Radiological Evaluation

Every patient was evaluated for operation time, intraoperative hemorrhage, postoperative drainage and Harris scores as well as CT images were used to assess the abduction and anteversion angle of the acetabulum (present the transverse view to measure the anteversion and the coronal view to measure the inclination) along with the distance from the hip center to ischial tuberosity line.

Statistical Analysis

SPSS 17.0 statistical software (SPSS Inc., USA) was applied. All measuring data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Continuous data were compared using independent samples t test and intra-group comparison before and after the surgery with paired t test. Ordinal data were compared using χ2 test. P value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The operation time (57.8 ± 3.73 m vs 62.1 ± 4.19 m), intraoperative bleeding (169 ± 34.1 ml vs 219 ± 38.0 ml) and postoperative hemorrhage (130 ± 27.2 ml vs 219. ± 37.4 ml) in the 3D printing group were lower than those in the traditional group (P < 0.05) and 6 months postoperative Harris scores in the 3D printing group were higher than those of the traditional group (93.9 ± 2.87 vs 91.8 ± 3.69, P = 0.009). Postoperative infection and loosening rates were 0 in two groups (Table 2). There was no statistical difference in the angles (abduction angle 42.25° ± 4.55° vs 43.60° ± 4.18°; anteversion angle 17.30° ± 5.12° vs 22.70° ± 4.03°) or positions (distance from hip center to ischial tuberosity line 80.84 ± 6.21 mm vs 78.77 ± 4.69 mm) between bilateral acetabulums in the 3D printing group, while in the traditional group, the anteversion angles (15.01° ± 5.68° vs 13.01° ± 5.62°, P = 0.015) and the cup positions (82.92 ± 5.73 mm vs 76.60 ± 2.83 mm, P = 0.002) at the ill side were larger than the healthy side. However, there was no statistical difference in abduction angles (38.60° ± 3.25° vs 43.30° ± 6.24°, P = 0.487) between bilateral acetabulums in the traditional group (Table 3).

Table 2.

Clinical variables in patients after surgery

| Operation time (m) | Intraoperative hemorrhage (ml) | Postoperative drainage (ml) | Infection | Loosening | Harris score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3D printing group | 57.8 ± 3.73 | 169 ± 34.1 | 130 ± 27.2 | 0 | 0 | 93.9 ± 2.87 |

| Traditional operation group | 62.1 ± 4.19 | 219 ± 38.0 | 219 ± 37.4 | 0 | 0 | 91.8 ± 3.69 |

| Value | P = 0.008 | P = 0.002 | P = 0.000 | P = 0.009 |

Table 3.

Analysis of bilateral joint angle after hip replacement

| Ipsilateral side (mm/°) | Contralateral side (mm/°) | t value | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3D printing group | ||||

| Abduction angle | 42.25 ± 4.55 | 43.60 ± 4.18 | 0.720 | 0.487 |

| Anteversion angle | 17.30 ± 5.12 | 22.70 ± 4.03 | − 1.315 | 0.215 |

| Distance from rotation center to ischial tuberosity connection | 80.84 ± 6.21 | 78.77 ± 4.69 | 0.919 | 0.368 |

| Traditional operation group | ||||

| Abduction angle | 38.60 ± 3.25 | 43.30 ± 6.24 | 2.888 | 0.487 |

| Anteversion angle | 15.01 ± 5.68 | 13.01 ± 5.62 | − 2.844 | 0.015 |

| Distance from rotation center to ischial tuberosity line | 82.92 ± 5.73 | 76.60 ± 2.83 | 3.423 | 0.002 |

Discussion

For DDH patients especially with a high dislocation, THA with placement of an acetabular cup in the false acetabulum cannot prevent limb shortening and the high prosthesis loosening rate; in contrast, placement of the acetabular cup in the true acetabulum can restore a normal anatomic center, balance low limb length, and improve abductor strength and gait [13]. In patients with DDH, high femoral dislocation and complex acetabular morphologies complicate the preoperative evaluation and surgical planning. Using 3D printing technology to print an actual-sized pelvic model, the surgeons can fully understand the anatomic abnormalities and develop a more complete surgical plan. Hurson et al. [14] described that using 3D models to evaluate the acetabulum in 20 patients, they changed the original surgical plan in 2 of the cases after studying full-scale models. With the development of digital medical and 3D printing technology, orthopedic treatments are moving towards individualization, precision and minimally invasion [15]. 3D printing guide plate produced by reverse modeling and RP technology has been widely used in orthopedics [16–18], so many groups have attempted to use navigation template on complex THA, Small et al. [19] designed a patient-specific instrumentation (PSI) to identify the true acetabular cup and a peripheral pin was used to guide the surgeon. Zhang et al. [20] created a guide pin used in Crowe I DDH, but they must use a hollow center acetabular reamer to drill and shape the prosthetic socket. Wang et al. [21] used arc-shaped PSI on Crowe type II/III DDH patients, however, we think a circular guide plate may provide higher accuracy than other technologies and our technique can be widely used in various types of DDH with no additional aid instrument.

In the previous work of Yan et al. [22], the team has measured the anatomic morphological abnormalities in the DDH based on 3D reconstruction of CT scans and found that the hips were individualized, also the true acetabulum was hard to identify during surgery. Based on the research, this study designed a guide plate which located the true acetabulum based on the false acetabulum, so that the base and the ring designed with a detachable card slot connection could be easily placed. If there were more osteophytes around the true acetabulum, it would be difficult to place the actual ring, the concentric rings growing in size could be designed, as the osteophytes were removed by reamer, a larger ring was changed stepwise until it was perfectly matched with the set cup size. The tricks made the operation easy, reduced soft tissue separating and operation time, as well as hemorrhage during and after the surgery. The postoperative CT images shown that the placement of cup in the 3D group was more accurate. Other researchers used 3D guide plate for individualized osteotomy in total knee arthroplasty, while the cadaveric test showed that individualized osteotomy was more accurate [23]. In addition, the higher postoperative Harris scores in the guide group indirectly suggested that the position and angle of acetabular cup were closer to the patients' physiological structures and biomechanics. The 3D printing guide used in THA could accelerate the patients’ recovery and improve life quality.

Failed hip arthroplasties are often shown as infection and aseptic loosening. Therefore, we compared the data between the two groups, infection and loosening rate were 0 in two groups, for which we consider the following reasons: small sample size, short follow-up. More cases and longer follow-up need to be carried out in the future, as it is believed that with shorter operation time and more accurate prosthesis placement, the 3D printing navigation template method carries no added risks for loosening and infections.

Conclusion

Based on the study, the 3D printing template technique could carry out the preoperative plan accurately and quickly and the location of acetabular cup in single DDH was more accurate than conventional methods. The technique could also accelerate the patients’ rehabilitation.

Acknowledgements

Funds: Science and Technology Foundation of Nantong City (GJZ16103).

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The Hospital General Universitario Ethic’s Committee approved the protocol.

Informed consent

All patients gave their informed consent for the inclusion in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Liang Yan and Peng Wang contributed equally to this work and should be considered co-first authors.

References

- 1.Sanchez-Sotelo J, Berry DJ, Trousdale RT, et al. Surgical treatment of developmental dysplasia of the hip in adults: II. Arthroplasty options. Journal of American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2002;10(5):334–344. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200209000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahmed E, Ibrahim EG, Ayman B. Total hip arthroplasty with subtrochanteric osteotomy in neglected dysplastic hip. International Orthopaedics. 2015;39(1):27–33. doi: 10.1007/s00264-014-2554-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eisler T, Svensson O, Tengstrom A, et al. Patient expectation and satisfaction in revision total hip arthroplasty. Journal of Arthroplasty. 2002;17(4):457–462. doi: 10.1054/arth.2002.31245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wroblewski BM. Current trends in revision of total hip arthroplasty. International Orthopaedics. 1984;8(2):89–93. doi: 10.1007/BF00265830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hartofilakidis G, Karachalios T. Total hip arthroplasty for congenital hip disease. J Bone Jt Surg. 2004;86(2):242–250. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200402000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dandachli W, Kannan V, Richards R, et al. Analysis of cover of the femoral head in normal and dysplastic hips: new CT-based technique. J Bone Jt Surg. 2008;90(11):1428–1434. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.90B11.20073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Argenson JN, Ryembault E, Flecher X, et al. Three-dimensional anatomy of the hip in osteoarthritis after developmental dysplasia. J Bone Jt Surg. 2005;87(9):1192–1196. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.87B9.15928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vulcano E, Murena L, Falvo DA, et al. Bone marrow aspirate and bone allograft to treat acetabular bone defects in revision total hip arthroplasty: preliminary report. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2013;17(16):2240–2249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen J, Zhu W, Zhang Z, et al. Efficacy of celecoxib for acute pain management following total hip arthroplasty in elderly patients: a prospective, randomized, placebo-control trial. Exp Ther Med. 2015;10(2):737–742. doi: 10.3892/etm.2015.2512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaneyama S, Sugawara T, Sumi M. Safe and accurate midcervical pedicle screw insertion procedure with the patient-specific screw guide template system. Spine. 2015;40(6):341–348. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000000772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen H, Wang G, Li R, et al. A novel navigation template for fixation of acetabular posterior column fractures with antegrade lag screws: design and application. International Orthopaedics. 2016;40(4):827–834. doi: 10.1007/s00264-015-2813-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen H, Wu D, Yang H, et al. Clinical use of 3D printing guide plate in posterior lumbar pedicle screw fixation. Medical Science Monitor. 2015;18(21):3948–3954. doi: 10.12659/MSM.895597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stans AA, Pagnano MW, Shaughnessy WJ, et al. Results of total hip arthroplasty for Crowe Type III developmental hip dysplasia. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 1998;348:149–157. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199803000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hurson C, Tansey A, O'Donnchadha B, et al. Rapid prototyping in the assessment, classification and preoperative planning of acetabular fractures. Injury. 2007;38(10):1158–1162. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2007.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ma L, Zhou Y, Zhu Y. 3D-printed guiding templates for improved osteosarcoma resection. Sci Rep. 2016;21(6):23335. doi: 10.1038/srep23335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kunz M, Rudan JF, Xenoyannis GL. Computer-assisted hip resurfacing using individualized drill templates. Journal of Arthroplasty. 2010;25(4):600–606. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2009.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kunz M, Balaketheeswaran S, Ellis RE, et al. The influence of osteophyte depiction in CT for patient-specific guided hip resurfacing procedures. International Journal of Computer Assisted Radiology and Surgery. 2015;10(6):717–726. doi: 10.1007/s11548-015-1200-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hananouchi T, Saito M, Koyama T, et al. Tailor-made surgical guide reduces incidence of outliers of cup placement. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 2010;468(4):1088–1095. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-0994-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Small T, Krebs V, Molloy R, et al. Comparison of acetabular shell position using patient specific instruments vs. standard surgical instruments: a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Arthroplasty. 2014;29(5):1030–1037. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2013.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang YZ, Chen B, Lu S, et al. Preliminary application of computer-assisted patient-specific acetabular navigational template for total hip arthroplasty in adult single development dysplasia of the hip. Int J Med Robot. 2011;7(4):469–474. doi: 10.1002/rcs.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang C, Xiao H, Yang W, et al. Accuracy and practicability of a patient-specific guide using acetabular superolateral rim during THA in Crowe II/III DDH patients: a retrospective study. J Orthop Surg Res. 2019;14(1):19. doi: 10.1186/s13018-018-1029-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yan L, Wang P, Tang C, et al. Effect of acetabular tilt angle on acetabular version in adults with developmental dysplasia of the hip. Zhongguo Xiu Fu Chong Jian Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2017;31(6):647–652. doi: 10.7507/1002-1892.201610040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lu S, Xu YQ, Zhang YZ, et al. A novel computer-assisted drill guide template for lumbar pedicle screw placement: a cadaveric and clinical study. Int J Med Robot. 2009;5(2):184–191. doi: 10.1002/rcs.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]