Abstract

Aim

There is a lack of consensus on the optimal method of performing primary hip arthroplasty in obese patients and limited evidence. This article presents a series of considerations based on the authors’ experiences as well as a review of the literature.

Preoperative Care

In the preoperative phase, an informed consent process is recommended. Weight loss is recommended according to NHS England guidelines, and body habitus should be taken into account. When templating, steps are taken to avoid overestimating the implant size.

Surgical Procedure

During the surgical procedure, specialist bariatric equipment is utilised: bariatric beds, extra supports, hover mattresses, longer scalpels, diathermy, cell saver and minimally invasive surgery equipment. Communication with the anaesthetist and surgical team to anticipate is vital. Intraoperative sizing and imaging, if required, should be considered. Pneumatic foot pumps are preferable for VTE prophylaxis. Regional anaesthesia is preferred due to technical difficulty. IV antibiotics and tranexamic acid are recommended. The anterior and posterior surgical approaches are most frequently used; we advocate posterior. Incisions are extensile and a higher offset is considered intraoperatively, as well as dual mobility and constrained liners to reduce dislocation risk. When closing the wound, Charnely button and sponge should be considered as well as negative pressure wound dressings (iNPWTd) and drains.

Post-operative Considerations

Postoperatively, difficult extubation should be anticipated with ITU/HDU beds available. Epidural anaesthetics for postoperative pain management require higher nursing vigilance. Chemical prophylaxis is recommended.

Conclusion

Despite being technically more difficult with higher risks, functional outcomes are comparable with patients with a normal BMI.

Keywords: Hip arthroplasty, Obesity, Total hip replacement, Technical, Tips tricks

Introduction

28.7% of adults in England are classified as obese [1]. This statistic has increased dramatically from 15 per cent in 1993 and is set to continue at an alarming rate throughout the U.K and worldwide. Obesity is defined as BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2, and subdivided into class I (30 to 34.9 kg/m2), class II (35 to 39.9 kg/m2) and class III (≥ 40 kg/m2), the latter termed ‘morbid obesity’. This poses unique challenges to the orthopaedic surgeon conducting total hip arthroplasty. Obesity has been shown to be directly linked to earlier age onset osteoarthritis leading to an increase in the number of total hip arthroplasties carried out in the National Health Service (NHS). In 2004, 42,796 Hip replacements were carried out in the U.K, this has increased to 92,824 in 2018 [2]. This is set to rise, with predictions that the NHS will need to carry out 439,097 hip replacements in 2035 [3]. Total Hip arthroplasty and revision hip surgery in the obese patient pose unique challenges. These patients typically require more preoperative optimisation, specialised bariatric equipment, are technically more difficult and have a higher risk of complications. As the class of obesity increases, so does the relative risk of requiring a joint replacement. This peaks at a relative risk of approximately 8.5 times for a total hip arthroplasty relative to normal weight individuals in Class III (morbidly) obese patients. Morbidly obese patients will also require total hip arthroplasty 10 years earlier than normal weighted individuals [4]. Despite being technically more difficult with higher risks, namely infection [5–7], functional outcomes are comparable with patients with a normal BMI [8].

Preoperative Care

Weight loss prior to hip arthroplasty should always be recommended, although the evidence is less established in hip arthroplasty compared to that for knee arthroplasty patients. This is supported by guidelines from National Institute Clinical Excellence (NICE), the International Consensus Meeting on musculoskeletal infections and NHS England [9–11]. Weight loss must be a lifestyle long-term choice even after arthroplasty. Sudden weight loss leads to a starvation process and malnutrition which may counter-intuitively increase the risk of infection [12].

Obese patients undergoing total hip arthroplasty should be counselled on the increased risk of anaesthetic and surgery and referral considered to a dietician as a minimum. Referral to a bariatric general surgical team should be considered with a BMI > 40 or > 35 with associated comorbidities such as type 2 diabetes as per the guidance set out by NHS England [10] and NICE [9].

It is important at this stage to define a patient that requires optimisation prior to a planned surgery date and those that are not currently fit for a surgical date to be given. 60% of surgical patients with OSA (obstructive sleep apnoea) are not diagnosed pre operatively [13]. The (STOP) snoring, tiredness, observed apnoea, high BP and (STOPBANG) BMI, age, neck circumference and gender questionnaires are a useful screening tool, primarily, to identify surgical patients with undiagnosed OSA but have also been shown to identify surgical patients with increased risk of a wide range of post-operative complications [14].

Many obese patients with OSA require CPAP (continuous positive airway pressure) patients should bring their own equipment and provide a service history. Ward teams are required to be familiar with set up and use, formal training and skill mix need to be confirmed as a prelude to the highlighted admission date. ECG and echocardiograms are typically requested by the anaesthetic team and a review of the patient’s medications and history.

Patient care begins with the ward team planning and training. Bariatric beds must be made available and staff training to allow familiarisation with equipment use and manual handling techniques is essential. Bed hoists maximum tolerances must be checked to be adequate for the patient. Bariatric chairs and commodes with increased width and load capacity will be required with availability confirmed prior to admission. Hydraulic beds are easier for the ward team to operate and less physically demanding on staff and post-operative patients. A formal risk assessment is recommended for protection of both patient and staff.

For the surgeon, it is not sufficient to recognise the patient’s increased BMI, care should be taken to recognise each patient’s individual body habitus. In men, obesity is more commonly truncal, leaving the limbs proportionally more spared, whereas in women, it trends towards concentration around the hips and lower limbs [15] making complications in obese women’s limbs more prevalent [16, 17]. These factors should be discussed with the patient as part of an informed consent process. The choice of approach is one that should be considered. A larger abdominal apron and higher BMI has been considered by some to be a contraindication for anterior approach [18], whereas others have felt that obesity in itself is a factor to suggest an anterior approach as compared to a more conventional posterior approach [19].

When templating the hip in the obese patient there is a tendency to overestimate the size of the prosthesis. This is magnification due to the increased distance from the patient’s skeleton to the X-ray plate produced by the increased soft tissue envelope. Careful placement of sizing markers on digital radiographs is a key step in avoiding this error. Intraoperative sizing is likely to be more accurate in obese patients with the additional investigation of intraoperative image intensifier use. This may not be the normal procedure for a surgical team and needs clarification at the time of the preoperative WHO check.

Surgical Procedure

Setup

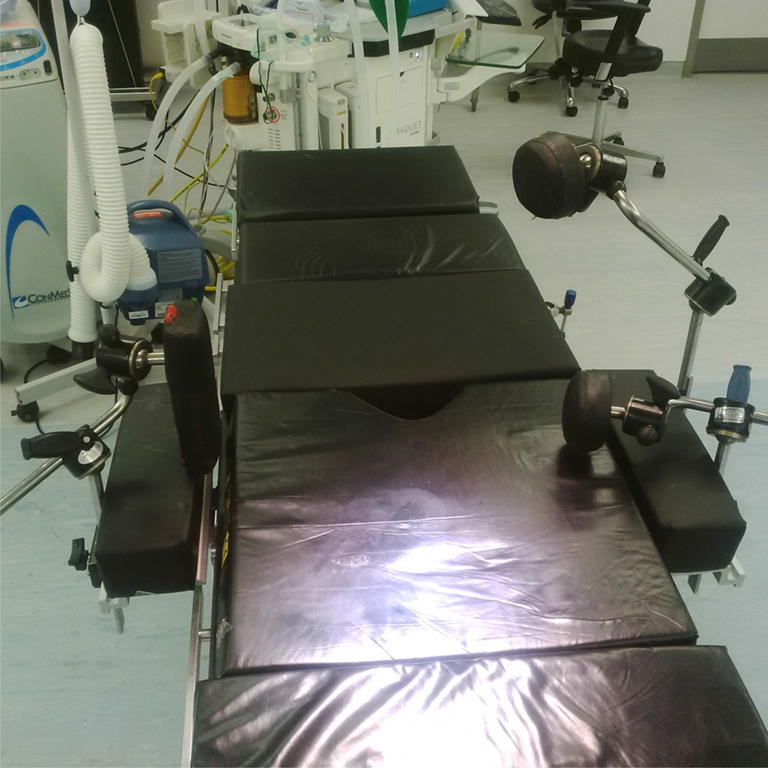

Begins with patient transport to theatre. This will likely require extra personnel for safe transfer. Hover mattresses are often used to transfer the patient in the operative theatre. The use of low friction sheets and matts has become popular but even with these additional equipment items it remains important to have the correct requisite personnel to transfer, turn and position a patient. This often means that additional theatre staffing should be planned for such cases. The operating table should be checked before patient arrival to ensure it is the correct mass, width and position relative to the patient. All mechanical items carry a tolerance limit and these can be exceeded in some larger patients. If this is not understood failure of hydraulic movement and safe balance of a table may be compromised (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Bariatric bed

Antithrombotic stockings are unlikely to be the correct size and cause limited ambulation, often leading to postphlebitic syndrome, more common in obese women [17]. A pneumatic pump can be fitted to the contralateral limb during surgery with the ipsilateral one fitted directly at the conclusion of surgery. Venothrombotic events are more common in the higher BMI patient and hence this diligence is highly recommended [15].

Preoperative formal communication with the anaesthetist is vital, in the obese patient there are many extra challenges with the airway, neck mobility, larynx visibility, reflux and difficult intubation. Obese patients have complex physiology often with multiple comorbidities. The authors recommend that an additional preoperative anaesthetic clinic appointment is made so that preparations are optimised.

Regional Anaesthesia is preferred over general anaesthesia due to the difficulty of tracheal intubation, gastric aspiration and hepatic damage reduced and high risk of Pickwickian carbon dioxide retention in the supine position [20]. Simple preparations including longer spinal needle sets are often required. Regional anaesthesia may be more technically difficult due to the patient’s habitus in recognising anatomical landmarks and more time should be planned for anaesthetic induction [21].

An understanding of pharmacokinetics of differing antibiotics and how this relates to overall body mass, fat distribution, kidney function provides prophylactic protection for the elevated BMI patient at higher risk of infection. Drug clearance may be increased in the obese patient, [22] which may lead to underdosing of antibiotics in obese patients undergoing surgery and subsequently infection [22]. In obese patients, Cephalosporins or Penicillin antibiotics are recommended for perioperative prophylaxis in total joint arthroplasty [11, 23]. The recommended dose of 1 g is increased to 2 g in obese patients to account for the increase in clearance [22]. The authors recommend giving intravenous antibiotics on induction, in a combination of Flucloxacillin 2 g and Gentamicin 240 mg. Repeat dosage of Gentamicin is avoided but subsequent 24 h of Flucloxacillin is recommended. Recognition of prolonged surgical time in difficult or revision cases may indicate repeat operative dosage of Flucloxacillin if greater than 3 h of surgical time has elapsed.

The authors use 2–3 gm of Tranexamic acid at induction as it has been shown to reduce the risk of post-operative transfusion in obese patients undergoing arthroplasty [24]. Hip arthroplasty is always longer and involves more extensive soft tissue dissection in the greater BMI patient hence blood loss is predictably increased from the average.

When positioning the patient for hip arthroplasty in the lateral position care must be taken to ensure positioning posts are adequately padded due to soft tissue pressure particularly around the Anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS). Standard supports may not fit, a bariatric clamp may be indicated. The ASIS is supported superiorly and inferiorly with different clamps to distribute the pressure as well as a back support. Padding should also be provided between the knees. The abdomen should as much as possible be left free from compression. Compression leads to increased intra-abdominal pressure and the dangers of reflux/aspiration for the anaesthetic team. This pressure also reduces venous return and, therefore, increases bleeding at the operative site. This is why the lateral decubitus position is well tolerated.

Aseptic technique during preoperative cleaning, thorough surgical site preparation and draping must be practiced to minimise the increased risk of infection in obese patients [11, 23]. The authors recommend preoperative Chlorhexidine (4%) showers, [25, 26] with the addition of a Chlorhexidine cloth to clean skin folds as described by Johnson et al. [27], where colonisation of bacteria is more prevalent in the obese patient. This is followed by two sterile preps on the table intraoperatively using Chlorhexidine alcohol prep.

Approach

The posterior and anterior approach to the hip are most frequently used in obese patients, although no clear consensus exists on the best approach in the obese patient. Some studies have shown successful short term outcomes with the anterior approach due to greater soft tissue preservation and lower dislocation rates [19, 29]. This approach is considered by some, technically difficult with a steep learning curve estimated at between 50 and 100 patients. It would seem unwise to select this approach for such challenging patients if it were not the normal practice of the surgeon.

Additionally, there is an increased risk of post-operative infection and re-operation in obese patients undergoing the anterior approach [30–32]. It is possible the reduced immune response in obese patients and the abdominal pannus contribute to the higher infection rate. However, Antoniadis et al. reported the anterior approach was still a viable option when compared to more extensile posterior approaches with similar complication rates [19]. It may yet prove to be the case that truncal obesity, as demonstrated in males is better addressed by the posterior approach to the hip, whilst buttock and thigh obesity, more demonstrated in females is better served by the anterior approach. This may help rationalise the approach debate.

The posterior approach, used more commonly, is recommended by the authors due to its extensile ability if required. In some extreme circumstances, where the patient’s habitus inhibits a traditional posterior approach or adequate retraction is impossible this can be modified from the same incision to an anterolateral approach. This demonstrates the importance of preoperative planning and the flexibility required by an arthroplasty surgeon.

In Such Cases

It is important to mark the skin incision and to use fixed bony anatomical landmarks such as the greater trochanter or anterior superior iliac spine as a reference, to ensure the patient’s habitus and soft tissue doesn’t distort the incision. In the super-high BMI patient, the surgeon should consider if Image Intensifier assistance should be considered as part of the operative plan for even the skin incision.

The incision is usually larger in the obese patient and extended proximally and distally. This is due to the thickness of soft tissue increasing the distance from the joint and hence affecting the pathway of angulation for cup closure etc. Although in the more average body habitus patient it may not be normal practice for a surgeon to use Image intensifier to confirm cup placement angulation, we do recommend it for the morbid obese patient. This additional check helps to reduce errors caused by patient movement on table and difficulty in access exposure.

When using the posterior approach to the hip, assisting is physically demanding and the assistant should be familiar with the steps involved. The need for two assistants so that physical fatigue can be limited is often considered by the authors.

Basic equipment (i.e., scalpels, diathermy may need to have longer handles to allow safe control and visualisation. Surface landmarks can be harder to palpate and care must be taken identifying them intraoperative image intensifier use has been previously discussed [17].

Diathermy should be readily available and used throughout the procedure due to increased bleeding in the obese patient [33] as well as cell saver, tranexamic acid and careful anaesthetic blood pressure control to minimise blood loss.

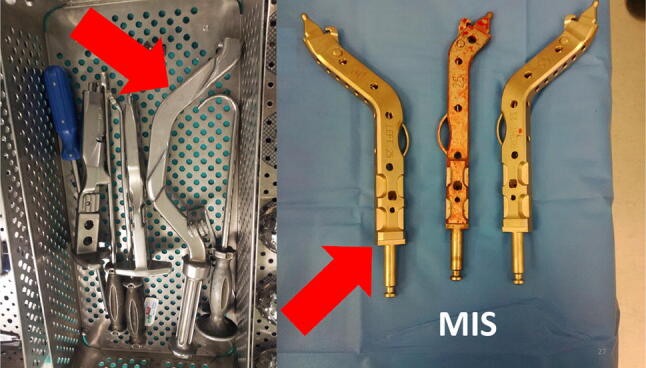

Minimally invasive surgery (MIS) technique tools should be made available and used where necessary in the obese patient such as MIS retractors and angled acetabular reamers [34]. This increases visualisation during the procedure and also minimises trauma to the soft tissues, decreasing both post-operative pain and poor soft tissue healing (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Minimally invasive surgery tools

Implants

Some implants are contraindicated in the obese patient. In a review of 200,054 patient records from the UK national joint registry, 25 implants were recorded in THR. Of the implants reviewed, 5 were contraindicated or advised against on obesity, leading to 10,745 patients (16%) receiving non recommended implants in obesity [35]. When choosing an implant care should be taken to read the manufacturers recommendations and any weight restriction given.

The Get it Right First Time (GIRFT) report by the British Orthopaedic Association (BOA) recognised the need to standardize the use of total hip replacement implants in the National Health Service in the UK, with a move towards cemented femoral implants [36].

There is no clear evidence in the literature that implant choice is affected in obese patients for total hip replacement. Few studies detail implant choice and in those that do, most studies include cemented prosthesis [37–39].

In one study, 2140 consecutive uncemented total hip replacements in the obese patient showed acceptable mid-terms survivor rates [40]. The ABGII Stryker ltd [41] femoral stem and cup was used with Hydroxyapatite coating.

The authors recommend the choice of a polished taper slip cemented femoral implant, when this is in line with the GIRFT report. The focus in the UK has been on age and bone quality being the drivers of implant choice. Although this may appear to be technically easier to perform in the obese patient with more reproducible results, particular attention is drawn to the need for avoidance of Valgus/Varus stem placement within the cement mantle that will lead to early failure. In appropriately aged patients, with a good quality Dorr Class A or B femur uncemented Titanium HA coated stems do maintain a role. There is no clear evidence that cup choice is affected in the obese patient. Method of implant fixation to bone should then be more considered regards surgeon experience and familiarity. Similarly, there is no evidence that cementing technique need be altered in the obese patient.

Standard liners may increase the risk of dislocation in the obese patient. Hernigou et al. found that at 7 year follow up in obese patients, 9% with standard liners had dislocated compared to 2% with dual mobility cups [41]. This is not just due to the mechanics of head/neck ration but due to extra-articular soft tissue impingement (thigh circumference) resulting in great lever-out forces at the hip joint. Dual mobility or constrained liners have been shown to reduce the rate of dislocations and should be considered [42]. However, constrained liners are mainly reserved for revisions following recurrent dislocation and there is no available evidence regarding the mid and long-term outcomes for these in obese patients. They have also been linked to early than hoped acetabular loosening, this is due to the benefit of constraint depending on limited range of movement increasing force transmission to the bone/cup interface due to impingement of the stem neck on the liner construct. Whereas dual mobility cups show good osseous integration as well as reduced dislocation and are, therefore, recommended by the authors [43]. They allow 80% of the range of movement to occur at the standard femoral head/dual mobility head interface, at that point of maximum excursion, impingement is avoided by the dual mobility head providing the last 20% of range of movement between itself and the cup.

This ability for two surface movements reduces the shear force transmission on the Polyethylene dual mobility head. This is felt to have a particular advantage in the penetrative wear profile of the obese patient.

Dislocation avoidance is always a combination of careful implant positioning and optimising the choice of femoral and acetabular offset to produce combined offset, leg length, vertical hip centre, head/neck ratio and head size (jump distance) [44]. A higher offset neck may also be considered in the obese patient, as it has been shown to reduce the risk of dislocation [45].

Closure

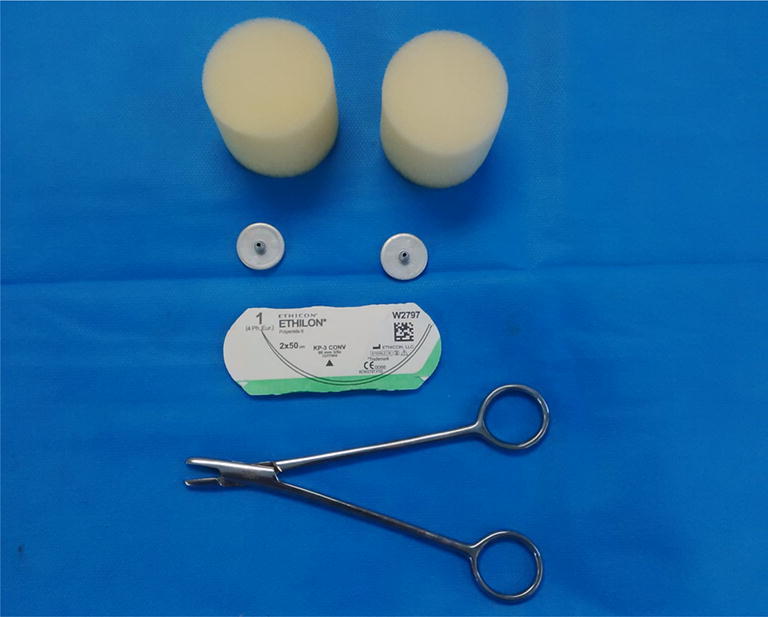

When suturing, Charnley sponge and buttons are used by the authors as deep tension sutures for the obese patient. The deep tension sutures help to stabilise the adipose layer. This reduces shearing and promotes more rapid wound adhesion. The use of drains although unfashionable allows suction adhesion of the adipose layer in combination with the deep tension sutures, hence reducing haematoma formation and dead space collection (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Charnley Button and Sponge

A further recommendation is use of incisional negative pressure wound therapy dressings (iNPWTd) such as PICO by Smith & Nephew Healthcare Ltd (Hull, United Kingdom) [46]. This method allows exudate to be more rapidly removed from the wound surface, increased exudate is a more common problem in the larger more extensive wounds of the obese and may continue for a protracted period of time [23, 47].

Post-operative Considerations

Difficult extubation of the obese patient with an ITU/HDU bed post-operatively should be anticipated [48]. Epidural anaesthetics for post-operative pain management require higher nursing vigilance due to the likelihood of developing pressure sores and neurapraxias in heavier limbs.

Pain relief may be more difficult to achieve in the obese patients as higher dosing is required of analgesia [49]. We recommend a multi-disciplinary approach utilising the Anaesthetic, Orthopaedic and Acute pain teams to achieve adequate analgesia.

Obese patients may be more restricted post-operatively in their rehabilitation and achieving functional milestones [50].

The evidence regarding length of stay in obese patients undergoing hip arthroplasty is not clear. In some studies it was not increased, [51], whilst in others, it was increased [52–54]. This may indicate the sub-specialist nature of this patient cohort.

Close coordination is required with the physiotherapist and occupational therapist team to ensure a safe and timely discharge with an appropriate package of care.

It is important to note that, overall, costs will be higher for the morbidly obese patient [51, 52]. It may be that recognition of this factor is required in procedure coding and provider renumeration.

The risk of readmission in the obese patient, increases with each BMI category when revision rates were reviewed in one study [55]. The probability of deep infection, mortality and periprosthetic fracture is higher in morbidly obese patients [8].

Super Obese

A new sub-classification of patients with BMI > 50 kg/m2 specified as “Super obese” was described by Schwarzkopf et al. [56]. The prevalence of super obese patients undergoing total hip arthroplasty increased by 120% between 2000 and 2010 in the USA [57]. Super obese patients still benefit from improved clinical and functional outcomes, [8]; however, their risk of in-hospital complications may be increased by up to 8.44 times [56]. The risk of complications in super obese patients is greater than even those in revision surgery, with a significantly greater risk of venous thromboembolism, infection, blood transfusion, medical complications, dislocation, readmission and early revision total hip arthroplasty [8]. The length of stay is also increased in the super obese by 13.8% for every 5 units above a BMI of 45 [56].

Complications

These factors may help to provide clear guidance during the preoperative informed consent process to both patient and surgeon:

Venothrombolic Events

Obesity is recognised as a risk factor for venothromboembolic events [15, 58]. Each patient should be risk assessed and selection of thromboembolic prophylaxis should be individualized. In addition to mechanical prophylaxis such as pneumatic pumps already described, VTE prophylaxis should include chemical prophylaxis such as a low molecular weight heparin (LMWH), this should be based on the ideal body weight rather that the total body weight [15].

Dislocation

Hip dislocation may be up to 4.42 times more prevalent in obese than non-obese patients with correctly positioned components [59]. This is likely a result of weaker muscles and poor muscle tone around the hip in obese patients which contributes to greater axial instability via a piston effect and joint separation [43].

Periprosthetic Surgical Site Infection

Obese patients have increased rates of infection after total hip arthroplasty [5–7]. Contributing factors include prolonged surgical time, poor adipose tissue vascularity, demanding surgical exposures, physiologically compromised immunity and inadequate prophylactic antibiotic dosing [22].

The frequency of periprosthetic infection has previously been reported as higher in obese patients [8], twice as high in patients with severe obesity and fourfold greater in morbidly obese patients [60].

Aseptic Loosening of Implant

The load across the hip joint is dependent on the patient’s weight [50, 60]. The joint reaction forces are increased in obese patients, it is not clear if this leads to increased wear [50, 60]. Some studies have shown no difference [50] [60] and others have shown an increased incidence of osteolysis [61, 62]. Goodnough et al. reported that obesity was an independent risk factor for aseptic loosening at a rate of 30% (18% in non-obese) within 5 years of implantation [62]. Electricwala et al. showed that preoperatively obese patients had a 4.7 times increased risk of early revision as a result of osteolysis after elective primary total hip arthroplasty [61].

Conclusion

Total hip arthroplasty in the obese patient requires more preoperative optimisation, specialised bariatric equipment, is technically more difficult and has a higher risk of complications. The surgeon should take necessary additional steps to plan for this, starting with careful preoperative optimisation and an informed consent process outlining these additional risks. During the surgical procedure, specialist bariatric equipment should be considered including bariatric beds, extra supports, hover mattresses, longer scalpels, diathermy and minimally invasive surgery equipment. It is important to communicate with the anaesthetist and surgical team and anticipate problems. Extra assistants and intraoperative imaging should be considered. When closing the wound, Charnely button and sponge should be considered as well as iNPWTd. Although the obese patient undergoing total hip arthroplasty requires special precautions and considerations, they can achieve satisfactory functional outcomes and an end result satisfying for all.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical standard statement

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by the any of the authors.

Informed consent

For this type of study informed consent is not required.

Contributor Information

John-Henry Rhind, Email: rhind99@doctors.org.uk.

Camilla Baker, Email: Camillabaker@hotmail.co.uk.

Philip John Roberts, Email: pjr67@hotmail.co.uk.

References

- 1.NHS Health Survey England,” 2017. [Online]. Retrived from https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/health-survey-for-england/2017.

- 2.H. Q. I. Partnership, “16th Annual Report National Joint Registry for England, Wales, Northern Ireland and the Isle of Man,” 2019.

- 3.Culliford D, Maskell J, Judge A, Cooper C, Prieto-Alhambra D, Arden N. Future projections of total hip and knee arthroplasty in the UK: Results from the UK Clinical Practice Research Datalink. Osteoarthritis and Cartlidge Journal. 2015;23:594–600. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2014.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Changulani M, Kalairajah Y, Peel T, Field R. The relationship between obesity and the age at which hip and knee replacement is undertaken. J Bone Joint Surg. 2008;90:360–363. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.90B3.19782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Malinzak R, Ritter M, Berend M. Morbidly obese, diabetic, younger, and unilateral joint arthroplasty patients have elevated total joint arthroplasty infection rates. The Journal of arthroplasty. 2009;24(6):84–88. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2009.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dowsey M, Choong P. Obesity is a major risk factor for prosthetic infection after primary hip arthroplasty. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 2008;466:153–158. doi: 10.1007/s11999-007-0016-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rajgopal R, Martin R, Howard J, Somerville L, MacDonald S, Bourne R. Outcomes and complications of total hip replacement in super-obese patients. The Bone & Joint Journal. 2013;95(6):758–763. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.95B6.31438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barrett M, Prasad A, Boyce LL. Total hip arthroplasty outcomes in morbidly obese patients: A systematic review. EFORT Open Reviews. 2018;3(9):507–512. doi: 10.1302/2058-5241.3.180011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.NICE, “NICE Guidelines Obesity,” 2006. [Online]. Retrieved from https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg189/evidence/obesity-update-appendix-p-pdf-6960327450.

- 10.NHS England guidelines Obesity,” 2016. [Online]. Retrieved from https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/appndx-7-obesity-surgery-guid.pdf.

- 11.Parvizi J, Gehrke T, Chen A. Proceedings of the international consensus on periprosthetic joint infection. The Bone & Joint Journal. 2013;95(11):1450–1452. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.95B11.33135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Macallan D. Malnutrition and infection. Medicine. 2005;33:14–16. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh M, Liao P, Kobah S, Wijeysundera D, Shapiro C, Chung F. Proportion of surgical patients with undiagnosed obstructive sleep apnoea. British Journal Anaesthesia. 2013;110(4):629–636. doi: 10.1093/bja/aes465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chung F, Abdullah H, Liao P. STOP-bang questionnaire a practical approach to screen for obstructive sleep apnea. CHEST Journal. 2016;149:631–638. doi: 10.1378/chest.15-0903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lang L, Parekh K, Tsui B, Maze M. Perioperative management of the obese surgical patient. British Medical Bulletin. 2017;124(1):135–155. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldx041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haynes J, Nam D, Barrack R. Obesity in total hip arthroplasty. Bone & Joint Journal. 2017;99:31–36. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.99B1.BJJ-2016-0346.R1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Booth R. Total knee arthroplasty in the obese patient: Tips and quips. Journal of Arthroplasty. 2002;17(4):69. doi: 10.1054/arth.2002.33265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sang W, Zhu L, Ma J. The influence of body mass index and hip anatomy on direct anterior approach total hip replacement. Medical Principles and Practice. 2016;25(6):555–560. doi: 10.1159/000447455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Antoniadis A. Is direct anterior approach a credible option for severely obese patients undergoing total hip arthroplasty? A matched-control, retrospective, clinical study. The Journal of arthroplasty. 2018;33(8):2535–2540. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2018.03.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shenkman Z, Shir Y, Brodsky JB. Perioperative management of the obese patient. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 1993;70(3):349–359. doi: 10.1093/bja/70.3.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kadry B, Press C, Alosh H. Obesity increases operating room times in patients undergoing primary hip arthroplasty: A retrospective cohort analysis. PeerJ. 2014;2:e530. doi: 10.7717/peerj.530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Janson B, Thursky K. Dosing of antibiotics in obesity. Curr Opin Infected Dis. 2012;25(6):634–649. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e328359a4c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parvizi J, Shohat N, Gerkhe T. Prevention of periprosthetic joint infection. Bone Joint Journal. 2017;99:4. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.99B4.BJJ-2016-1212.R1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meftah M, White P, Kirschenbaum I. Tranexamic acid reduces blood loss during joint replacement in obese patients, bone and joint. Surgical Technology International. 2019;34:451–455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jakobsson J, Perlkvist A, Wann-Hansson C. Searching for evidence regarding using preoperative disinfection showers to prevent surgical site infections: A systematic review. Worldviews on Evidence Based Nursing. 2011;8(3):143–152. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-6787.2010.00201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Darouiche R, Wall J, Itani K. Chlorhexidine–alcohol versus povidone– iodine for surgical-site antisepsis. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;362:18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson A, Daley J, Zywiel M, Delanois R, Mont M. Preoperative chlorhexidine preparation and the incidence of surgical site infections after hip arthroplasty. The Journal of Arthroplasty. 2010;25:6. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2010.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kapadia B, Johnson A, Daley J, Issa K, Mont M. Pre-admission cutaneous chlorhexidine preparation reduces surgical site infections in total hip arthroplasty. The Journal of Arthroplasty. 2012;28(3):490–493. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2012.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zawadsky N. early outcomes of obese patients undergoing total hip arthroplasty: Comparison of anterior and posterior approaches. Orthopaedic Proceedings. 2018;2018(101):83. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Russo M, Macdonell R, Paulus M, Keller J, Zawadsky M. Increased complications in obese patients undergoing direct anterior total hip arthroplasty. The Journal of Arthroplasty. 2015;30(8):1384–1387. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2015.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Watts C, Houdek M, Wagner E, Sculco P, Chalmers B, Taunton M. High risk of wound complications following direct anterior total hip arthroplasty in obese patients. Journal of Arthroplasty. 2015;30(12):2296–2298. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2015.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Christensen C, Karthikeyan T, Jacobs C. Greater prevalence of wound complications requiring reoperation with direct anterior approach total hip arthroplasty. Journal of Arthroplasty. 2014;29(9):1839–1841. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2014.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bowditch M, Villar R. Do obese patients bleed more? Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. 1999;81(3):198. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.N. Siddiqui, P. Mohandas, S. Muirhead-Allwood and T. Nuthall, “A review of minimally invasive hip replacement surgery—current practice and the way forward,” Current Orthopaedics, pp. 247-254, 2005.

- 35.Craik J, Bircher M, Rickman M. Hip and knee arthroplasty implants contraindicated in obesity. RCS Annals. 2016;98(5):295–299. doi: 10.1308/rcsann.2016.0103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.T. Briggs (2015) A national review of adult elective orthopaedic services in England GETTING IT RIGHT FIRST TIME. Retrieved May 11, 2015, from https://gettingitrightfirsttime.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/GIRFT-National-Report-Mar15-Web.pdf

- 37.Jackson M, Sexton S, Yeung W, Walter W, Walter B, Zicat B. The effect of obesity on the mid-term survival and clinical outcome of cementless total hip replacement,”. The Bone & Joint Journal. 2009;91:1296–1300. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.91B10.22544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tai S, Imbuldeniya A, Munir S, et al. The effect of obesity on the clinical, functional and radiological outcome of cementless total hip replacement: A case-matched study with a minimum 10-year follow-up. The Journal of Arthroplasty. 2014;29:9. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2014.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chee Y, Teoh K, Sabnis B, Ballantyne J. Total hip replacement in morbidly obese patients with osteoarthritis. The Bone & Joint Journal. 2010;92:8. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.92B8.22764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McCalden R, Charron K, MacDonald S, Bourne R, Naudie D. Does morbid obesity affect the outcome of total hip replacement? The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 2011;93(3):321–325. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.93B3.25876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stryker, “ABG® II Cementless,” [Online]. Retrieved from https://www.strykermeded.com/media/1998/abg-ii-cementless-surgical-technique.pdf.

- 42.Hernigou P, Trousselier M, Roubineau F. Dual-mobility or constrained liners are more effective than preoperative bariatric surgery in prevention of tha dislocation. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 2016;474(10):2202–2210. doi: 10.1007/s11999-016-4859-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maisongrosse P, Lepage B, Cavaignac E, Pailhe R, Reina N, Chiron P, Laffosse J. Obesity is no longer a risk factor for dislocation after total hip arthroplasty with a double-mobility cup. International Orthopaedics. 2015;39(7):1251–1258. doi: 10.1007/s00264-014-2612-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bunn A, Clifford C, Darryl D. Effect of head diameter on passive and active dynamic hip dislocation. Journal of Orthopaedic Research. 2014;32(11):1525–1531. doi: 10.1002/jor.22659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Elkins M, Daniel M, Pederson D. Morbid obesity may increase dislocation in total hip patients: A biomechanical analysis. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 2012;471:971–980. doi: 10.1007/s11999-012-2512-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.S. &. Nephew, “Smith & Nephew PICO,” [Online]. https://www.smith-nephew.com/key-products/advanced-wound-management/pico/.

- 47.Karlakki S, Hamad A, Whittall C, Graham N, Bannerjee R, Kuiper J. Incisional negative pressure wound therapy dressings (iNPWTd) in routine primary hip and knee arthroplasties A randomised controlled trial. Bone & Joint Research. 2016;5:328–337. doi: 10.1302/2046-3758.58.BJR-2016-0022.R1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vasarhelyi E, Macdonald S. The influence of obesity on total joint arthroplasty. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 2012;94:100–102. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.94B11.30619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Popescu W, Schwartz J. Perioperative considerations for the morbidly obese patient. Advances in Anesthesia. 2007;25:59–77. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Andrew J, Palan J, Kurup H, Gibson P, Murray D, Beard D. Obesity in total hip replacement. Journal Bone Joint Surgery. 2008;90:424–429. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.90B4.20522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Batsis J, Naessens J, Keegan M. Impact of body mass on hospital resource use in total hip arthroplasty. Public Health Nutrition. 2009;12(8):1122–1132. doi: 10.1017/S1368980009005072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kremers M, Visscher S, Kremers W, Naessens J, Lewallen D. Obesity increases length of stay and direct medical costs in total hip arthroplasty. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 2014;472(4):1232–1239. doi: 10.1007/s11999-013-3316-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bradley B, Griffiths S, Stewart K, Higgins G, Hockings M, Isaac D. The effect of obesity and increasing age on operative time and length of stay in primary hip and knee arthroplasty. The Journal of Arthroplasty. 2014;29(10):1906–1910. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2014.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vincent H, Weng J, Vincent K. Effect of obesity on inpatient rehabilitation outcomes after total hip arthroplasty. Obesity. 2007;15(2):522–530. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jeschke E, Citak M, Gunster C. Obesity increases the risk of postoperative complications and revision rates following primary total hip arthroplasty: An analysis of 131,576 total hip arthroplasty cases. Journal Arthroplasty. 2018;33(7):2287–2292. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2018.02.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schwarzkopf R, Thompson S, Adwar S, Liublinska V, Slover J. Postoperative complication rates in the “super-obese” hip and knee arthroplasty population. Journal of Arthroplasty. 2012;27(3):397–401. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2011.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Meller M, Toossi N, Gonzalez M, Son M, Lau E, Johanson N. Surgical risks and costs of care are greater in patients who are super obese and undergoing THA. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 2016;474(11):2472–2481. doi: 10.1007/s11999-016-5039-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhang J, Chen Z, Zheng J, Breusch S, Tian J. Risk factors for venous thromboembolism after total hip and total knee arthroplasty: A meta-analysis. Archives of Orthopaedic and Trauma Surgery. 2015;135(6):759–772. doi: 10.1007/s00402-015-2208-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Davis A, Wood A, Keenan A, Brenkel I, Ballantyne J. Does body mass index affect clinical outcome post-operatively and at five years after primary unilateral total hip replacement performed for osteoarthritis? A multivariate analysis of prospective data. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. British Volume. 2011;93(9):1178–1182. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.93B9.26873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lubbeke A, Moons K, Garavaglia G, Hoffmeyer P. Outcomes of obese and nonobese patients undergoing revision total hip arthroplasty. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2008;59(5):138–145. doi: 10.1002/art.23562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Electricwala A, Narkbunnam R, Huddleston J, Maloney W, Goodman S, Amanatullah D. Obesity is associated with early total hip revision for aseptic loosening. Journal Arthroplasty. 2016;31(9):217–220. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2016.02.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Goognough L, Finlay A, Huddleston J, Goodman S, Maloney W, Amantullah D. Obesity is independently associated with early aseptic loosening in primary total hip arthroplasty. Journal Arthroplasty. 2018;33(3):882–886. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2017.09.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]