Abstract

There are no definitive guidelines for management of chronic or refractory immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) in children. Dapsone is an inexpensive and efficacious, yet neglected, therapeutic option for treatment of chronic ITP. We evaluated the efficacy and safety of dapsone in the management of chronic ITP in children. Children with chronic ITP < 14 years with minimum grade 2 bleeds refractory to either splenectomy/rituximab/eltrombopag; who were offered dapsone therapy were retrospectively analyzed. Dapsone intolerance and G6PD deficiency were excluded. Dapsone was started at a dose of 1–2 mg/kg/day. Response to dapsone as per international working group definitions, time to response along with side-effects were noted. Forty-four children enrolled; 29 analyzed. Nineteen were refractory to rituximab, 8 to splenectomy and 6 to eltrombopag. Median age was 9.8 years (3–14) with 16/29 males. Median dapsone dose was 1.59 mg/kg/day (range 1–2.1). Overall response was seen in 21/29 (72%): Complete Response in 7/29 (24%), Partial Response in 14/29 (48%). All responses were sustained for minimum 3 months. Median duration to response was 2.9 months (2–6.6). Median follow up was 28 months (6–73) and relapse rate-21%. Major side effects noted: Methemoglobinemia-01, skin ulceration-02. In three cases dapsone could be tapered and stopped without relapse. Dapsone is an economical and efficacious agent with good safety profile in childhood chronic/refractory ITP.

Keywords: Dapsone, Immune thrombocytopenia, Chronic ITP, Refractory ITP

Introduction

Chronic immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) comprises about 20% of primary ITP in children [1]. In absence of robust guidelines, management of chronic ITP poses challenges to pediatric hematologists. Dapsone is being used in general clinical practice in the management of ITP. More than 80% children with ITP have spontaneous resolution making it difficult to draw any conclusion regarding the efficacy of dapsone in acute or persistent ITP. However, dapsone is an inexpensive and efficacious yet neglected therapeutic option for treatment of chronic ITP [2]. Management of chronic ITP utilizes “tier based” approach. Splenectomy, rituximab, low dose continuous steroids and thrombopoeitin receptor (TPO-R) agonist are proposed tier 1 modalities of management [1]. The treatment with above agents is not only expensive but also has myriad of adverse events. There is paucity of data on use of dapsone as a therapeutic option in chronic ITP in children. We retrospectively evaluated the efficacy and safety of dapsone in the management of chronic ITP in children.

Methods

This retrospective observational study was performed at a tertiary care centre in northern India. Children with chronic ITP (with documented thrombocytopenia of 1 year duration) less than 14 years of age with grade of bleed ≥ 2; refractory to either splenectomy or rituximab or eltrombopag who were offered dapsone therapy between Jan 2010 and Dec 2017 were enrolled in the study. An International Working Group (IWG) definition of “refractory ITP” as a disease that does not respond to or relapses after splenectomy and that requires treatment to reduce clinically significant bleeding as well as a broader definition which encompasses children who not only require treatment to mitigate bleeding risk after splenectomy; but also patients who are unable or disinclined to undergo splenectomy and in whom primary objective is to improve health related quality of life was used [1, 3]. The grade of bleed, as proposed by Buchnan et al., was the most severe grade experienced by child before subjecting the child to dapsone [4]. The consent for splenectomy was denied by parents in children who were treated with rituximab and eltrombopag. Diagnosis of ITP was on the basis of thrombocytopenia in a well looking child with no hepato-splenomegaly after ruling out secondary causes (negative anti nuclear antibodies, HIV-ELISA, and anti-HCV). All children underwent bone marrow analysis which was suggestive of megakaryocytic thrombocytopenia. Male subjects were screened for G6PD deficiency. Children with G6PD deficiency, using concomitant drugs apart from dapsone and requiring discontinuation of dapsone before 6 months of exposure were excluded from final analysis. The rescue therapy with intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) or anti-D or steroids was offered in case of clinically significant bleeds.

Dapsone Therapy

An informed consent was taken from parents/guardians. Dapsone was started at a dose of 1–2 mg/kg/day; rounded to nearest tablet strength. Trial of dapsone was given for a minimum of 6 months. Dapsone was continued for a variable period of time depending on peak response. Responses to dapsone, time to response along with side-effects were noted in patient files during routine visit to follow up clinics. Data for analysis was retrieved from patient files.

Response Criteria

Complete response (CR)-Platelet count > 100 × 109/L without bleeds on 2 occasions > 7 days apart; Partial response (PR)-platelet count > 30 × 109/L without bleeds and a greater than twofold increase in platelet count from baseline measured on 2 occasions 7 days apart [3]; No response (NR)-No rise in platelet count or clinically significant bleed requiring rescue therapy. Persistent response was defined as response lasting for minimum 3 months on dapsone therapy. The factors affecting response to dapsone were studied.

Toxicity Criteria

Toxicities were reported as per the National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria (CTCAE version 4.0) [5].

Results

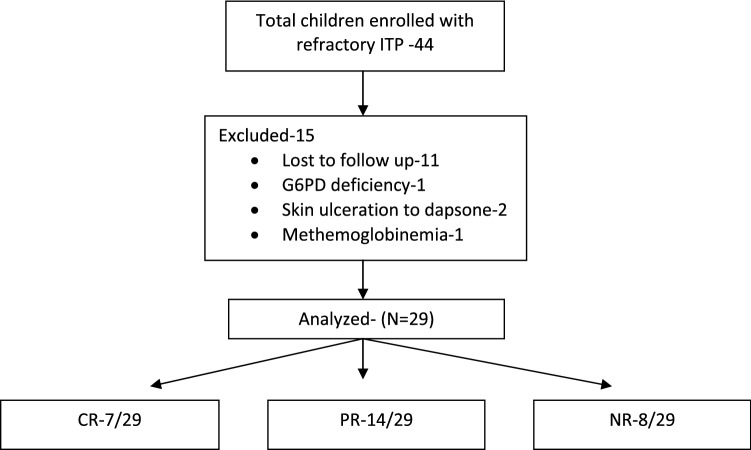

Forty-four children were enrolled and 29 analyzed (Fig. 1). Nineteen cases were refractory to rituximab, eight to splenectomy and six to eltrombopag. Four children were refractory to at least two tier 1 modalities. Four had failed alternative drugs (azathioprine).

Fig. 1.

Patient flow sheet

Baseline Characteristics

The mean age was 9.8 years (range 3–14), with male preponderance(55%). The median platelet count before start of dapsone was 11 × 109/L (range 5–18). Sixty eight percent (20/29) had grade II while 32% (9/29) had grade III/IV grade of maximum bleeding noted before start of dapsone.

Response to Dapsone Therapy

Overall response was seen in 21/29 (72%). CR in 7/29 (24%), PR in 14/29 (48%) and NR in 8/29 (28%). Median duration to response was 2.9 months (2–6.6). All cases had shown a persistent response. Mean dapsone dose used was 1.59 (range 1–2.1). Mean follow-up was 28 months (6–73). One-fifth of the children relapsed on dapsone or after discontinuation of dapsone. Two children who relapsed had CR, while four children had PR.

In three cases dapsone could be tapered and stopped without relapse. They were all male. None of them was subjected to splenectomy. CR was documented for at least 1 year on dapsone therapy before stopping it. Case 1 was 12 year old with grade 2 bleed who had CR after 16 weeks of dapsone and is on follow up for 18 months post cessation of dapsone. Case 2 was 4 year old with grade 2 bleed who was in CR after 13 weeks of therapy and is on follow up for 6 months. Case 3 was 3 year old with history of grade 4 intracranial bleed who had CR after 16 weeks of dapsone and is on follow up for 21 months.

The children with response to dapsone were younger. However response to dapsone was not determined by sex, maximum grade of bleed before start of dapsone, median platelet count at start of dapsone or splenectomy status.

Adverse Effects

Major side effects noted were methemoglobinemia in one and skin ulceration in two cases in first month of exposure to dapsone. No hemolysis was noted. These three cases did not get re-exposure to dapsone and were excluded from final analysis. No adverse effects attributable to dapsone were noted in the analyzed group.

Discussion

In 1988, dapsone responsive thrombocytopenia was noted serendipitously in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus; encouraging dapsone use in ITP [6]. Majority of children with ITP have spontaneous resolution within 1 year of onset, therefore it becomes difficult to justify the efficacy of dapsone in acute or persistent ITP. Dapsone is one of the oldest and safest agents in management of chronic ITP [2]. The data regarding effectiveness of dapsone in pediatric age group is largely restricted to case reports and small case series. The efficacy of dapsone ranges from 9 to 50% in chronic ITP [7–10].

Therapeutic agents used in management of chronic ITP include low dose prolonged steroids, splenectomy, rituximab and TPO-R agonist. Splenectomy remains gold standard with a response rate of 50–70% [1]. Splenectomy poses prolonged risks including infection and cardiovascular complications particularly in children [11]. After introduction of rituximab and TPO-R agonist the indications of splenectomy in childhood ITP have become more stringent [1]. Rituximab and TPO-R agonist are expensive and associated with significant side-effects. In our cohort the commonest agent tried was rituximab (in nearly two-thirds) followed by splenectomy and eltrombopag. In our study, less than one-fourth of patient underwent splenectomy. Similar low splenectomy rates were reported in other studies (Table 1).

Table 1.

| Damodar et al. [10] | Durand et al. [12] | Patel et al. [9] | This study | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study design | Retrospective | Retrospective | Retrospective | Retrospective |

| ITP type | Chronic |

5-Acute ITP 2-Chronic ITP |

All ITP | Chronic |

| Splenectomy | 4/35 | 1/7 | NA | 8/29 |

| Average dose (mg/kg) | 2.15 | NA | 1.57 | 1.59 |

| Number of pediatric patients | 35 | 7 | 12 | 29 |

| Mean age (years) (range) | 8.1 (3–15) | 6–15 | 7.9 (2.5–15) | 9.8 (3–14) |

| Mean duration of ITP (months) (range) | 21.8 (6–132) |

Acute: 2–6 Chronic: 51–102 |

23.4 (0.5–73) | > 12 |

| Overall responseb (%) | 23 (65.7) | 3/7 (42.8) | 6/11 (54.5) | 21/29 (72) |

| Complete response (%) | 17 (48.5) | 3/7 (42.8) | 5/11 (45.5) | 7/29 (24) |

| Partial response (%) | 6 (17.1) | – | 1/11 (9.1) | 14/29 (48) |

| No response (%) | 12 (34.4) | 2/7 (28)a | 5/11 (45.5) | 8/29 (28) |

| Average time to response (months) | 3.5 | 3.7 (1–9) | 1.8 (0.5–3.5) | 2.9 (2–6.6) |

| Relapse rate (%) | 15.5 | 100 | 33.3 | 21% |

| CCR/persistent responsec | 31.4 | NA | NA | 72% |

aDapsone was discontinued in 2 patients

bDapsone response was defined as platelets surpassing 50 × 109/L and at least twice the initial level [12]. Dapsone response: PR-if the increase in the platelet count was between 50 and 100 × 109/L; CR-if the increase in the platelet count was > 100 × 109/L [10]

cCCR-continuous CR > 6 months [10]

ITP Immune thrombocytopenia, NA not available

Our cohort had higher mean age with higher overall response rate, though the CR rates were lesser (Table 1). Conflicting definitions for responses may explain these differences. Average time to response across all studies is around 3 months; therefore a minimal 3–6 month of dapsone trial is warranted before labeling it ineffective. A prolonged exposure of dapsone may be required for sustained response as the relapse rate ranges from 21 to 100% and less than 10% of the patients may continue to be responsive after discontinuation of dapsone (Table 1).

Toxicities of dapsone include hemolysis in G6PD deficient individuals, gastro-intestinal intolerance, methemoglobinemia, agranulocytosis and hypersensitivity [2]. In most of the studies, dapsone was found to be a safe drug which rarely requires discontinuation [7–10].

Mechanism of action of dapsone in chronic ITP is still not clear. Induction of low grade hemolysis interfering with platelet destruction in reticulo-endothelial system and suppression of anti-platelet antibodies have been widely propagated [7, 12]. Previous studies to demonstrate a fall in hemoglobin with dapsone administration had conflicting results [7, 10]. The reasons for sustained response to dapsone also cannot be explained by above studies and is still speculative.

Our cohort with chronic ITP fulfills newer cut-off duration of 1 year and response criterion as given by IWG [3]. Our study also encompasses a wider definition and strict inclusion criteria of refractory ITP compared to previous studies where the population was heterogeneous. Majority of ITP resolve spontaneously, therefore a control arm in our study would have been ideal. Spontaneous remission rates described in chronic ITP in children is around 16% at 1–2 year and 30–50% at 5 years after diagnosis [13]. A response rate of 72% in our study therefore, may not be solely ascribed to spontaneous remission. A high loss to follow up rate was attributed to non-static nature of our study population.

In resource-poor settings, dapsone is an economical and efficacious drug with good safety profile in childhood chronic ITP. It may not only be used as a bridge therapy before splenectomy; but also as a long-term agent instead of other costlier agents. Response to dapsone is sustained but a prolonged exposure is required. Large controlled prospective trials are required to extract maximum therapeutic benefit out of dapsone.

Abbreviations

- ITP

Immune thrombocytopenic purpura

- TPO-R

Thrombopoeitin receptor

- G6PD

Glucose 6 phosphate dehydrogenase

- CR

Complete response

- PR

Partial response

- NR

No response

- IWG

International working group

- CTCAE

Common terminology criteria for adverse events

- HRQoL

Health related quality of life

Author’s Contribution

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by SK. The first draft of the manuscript was written by SK and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

Being a retrospective observational study for an established drug use in a particular condition the ethics committee approval was not warranted.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from parents/guardians of all individual participants included in the study at the time of enrollment.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Cuker A, Neunert CE. How I treat refractory immune thrombocytopenia. Blood. 2016;128(12):1547–1554. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-03-603365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rodrigo C, Gooneratne L. Dapsone for primary immune thrombocytopenia in adults and children: an evidence-based review. J Thromb Haemost. 2013;11(11):1946–1953. doi: 10.1111/jth.12371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rodeghiero F, Stasi R, Gernsheimer T, Michel M, Provan D, Arnold DM, et al. Standardization of terminology, definitions and outcome criteria in immune thrombocytopenic purpura of adults and children: report from an international working group. Blood. 2009;113(11):2386–2393. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-162503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buchanan GR, Adix L. Grading of hemorrhage in children with idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. J Pediatr. 2002;141(5):683–688. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2002.128547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Cancer Institute, National Institute of Health. Common terminology criteria for adverse events (2010) https://evs.nci.nih.gov/ftp1/CTCAE/CTCAE_4.03/CTCAE_4.03_2010-06-14_QuickReference_5x7.pdf

- 6.Moss C, Hamilton PJ. Thrombocytopenia in systemic lupus erythematosus responsive to dapsone. BMJ. 1988;297(6643):266. doi: 10.1136/bmj.297.6643.266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Godeau B, Durand JM, Roudot-Thoraval F, Tennezé A, Oksenhendler E, Kaplanski G, et al. Dapsone for chronic autoimmune thrombocytopenic purpura: a report of 66 cases. Br J Haematol. 1997;97(2):336–339. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1997.412687.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oo T, Hill QA. Disappointing response to dapsone as second line therapy for primary ITP: a case series. Ann Hematol. 2015;94(6):1053–1054. doi: 10.1007/s00277-014-2285-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patel AP, Patil AS. Dapsone for immune thrombocytopenic purpura in children and adults. Platelets. 2015;26(2):164–167. doi: 10.3109/09537104.2014.886677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Damodar S, Viswabandya A, George B, Mathews V, Chandy M, Srivastava A. Dapsone for chronic idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura in children and adults—a report on 90 patients. Eur J Haematol. 2005;75(4):328–331. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2005.00545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chaturvedi S, Arnold DM, McCrae KR. Splenectomy for immune thrombocytopenia: down but not out. Blood. 2018;131:1172–1182. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-09-742353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Durand JM, Lefèvre P, Hovette P, Mongin M, Soubeyrand J. Dapsone for idiopathic autoimmune thrombocytopenic purpura in elderly patients. Br J Haematol. 1991;78(3):459–460. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1991.tb04467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bansal D, Bhamare TA, Trehan A, Ahluwalia J, Varma N, Marwaha RK. Outcome of chronic idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura in children. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2010;54(3):403–407. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]