Abstract

In a healthy person, the kidney filters nearly 200 g of glucose per day, almost all of which is reabsorbed. The primary transporter responsible for renal glucose reabsorption is sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2). Based on the impact of SGLT2 to prevent renal glucose wasting, SGLT2 inhibitors have been developed to treat diabetes and are the newest class of glucose-lowering agents approved in the United States. By inhibiting glucose reabsorption in the proximal tubule, these agents promote glycosuria, thereby reducing blood glucose concentrations and often resulting in modest weight loss. Recent work in humans and rodents has demonstrated that the clinical utility of these agents may not be limited to diabetes management: SGLT2 inhibitors have also shown therapeutic promise in improving outcomes in heart failure, atrial fibrillation, and, in preclinical studies, certain cancers. Unfortunately, these benefits are not without risk: SGLT2 inhibitors predispose to euglycemic ketoacidosis in those with type 2 diabetes and, largely for this reason, are not approved to treat type 1 diabetes. The mechanism for each of the beneficial and harmful effects of SGLT2 inhibitors—with the exception of their effect to lower plasma glucose concentrations—is an area of active investigation. In this review, we discuss the mechanisms by which these drugs cause euglycemic ketoacidosis and hyperglucagonemia and stimulate hepatic gluconeogenesis as well as their beneficial effects in cardiovascular disease and cancer. In so doing, we aim to highlight the crucial role for selecting patients for SGLT2 inhibitor therapy and highlight several crucial questions that remain unanswered.

Keywords: SGLT2 inhibitor, diabetes, glucose, lipolysis, diabetic ketoacidosis, heart failure, cancer, dehydration, ketogenesis, glucagon, gluconeogenesis, type 2 diabetes, type 1 diabetes, counterregulation, euglycemic-ketoacidosis, insulinopenia

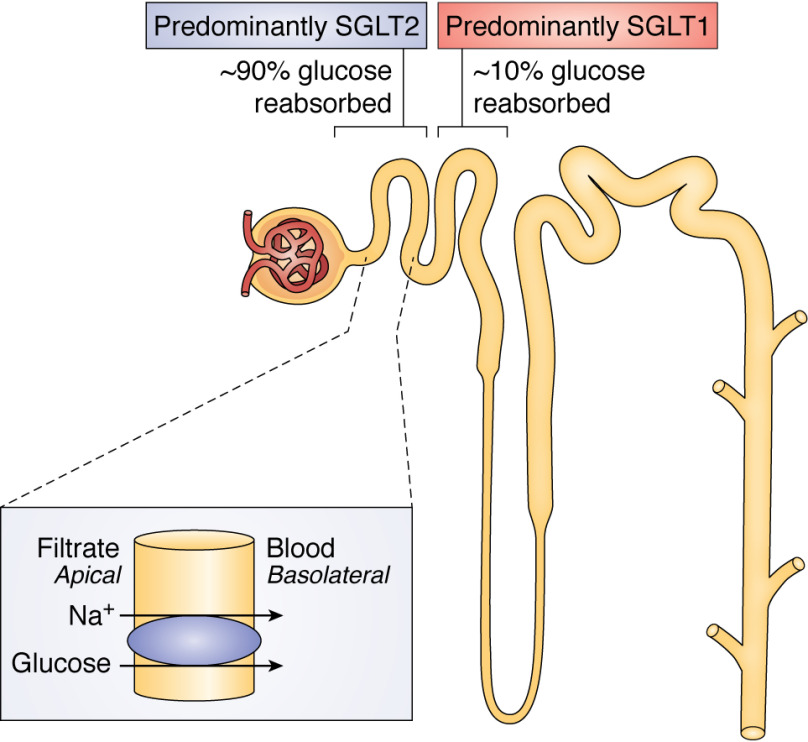

SGLT2, also known as SLC5A2, is the primary glucose transport protein in the proximal segment of the proximal tubule of the nephron (1). SGLT2, found at the apical membrane of the brush border in renal proximal tubule cells (2), is a low-affinity (Km ∼0.4 mm (3)), high-capacity (filtering ∼180 g of glucose/day) glucose transporter that is traditionally considered responsible for 80–97% of renal glucose reabsorption (4–7) (Fig. 1). SGLT2 inhibitors (gliflozins) are a unique class of diabetes drug: these agents are the only approved agents that waste glucose through the urine rather than reducing hepatic glucose output (biguanides), increasing tissue glucose uptake (insulin, sulfonylureas, thiazolidinediones, incretins), or inhibiting intestinal carbohydrate uptake (α-glucosidase inhibitors). Gliflozins are highly selective, competitive inhibitors, offering great promise for treatment of diabetes. However, the use of these agents has been complicated by clinical side effects that can be traced to a lack of full understanding of the corresponding biology. This review explores the current state of the field, capturing open biological and medical questions as well as emerging applications of SGLT2 inhibitors.

Figure 1.

The location of SGLT1 and SGLT2 transporters in the nephron and the mechanism by which SGLT2 inhibitors promote renal glucose wasting.

History and mechanism of SGLT2 inhibitors

Seemingly paradoxically, pharmacokinetics data would suggest that at the concentrations of SGLT2 inhibitors achieved in vivo (<0.5–1.5 μm (8), 3 orders of magnitude higher than the IC50 of ∼1.5 nm (9)), glucose reuptake through SGLT2 would be totally inhibited (predicting an 80–97% reduction in renal glucose reabsorption) (10, 11); however, SGLT2 inhibitors have been shown to inhibit only 30–50% of glucose reabsorption in clinical studies (12). It is likely that increased glucose reabsorption by SGLT1 contributes substantially when SGLT2 is inhibited; the maximal glucose transport capacity of SGLT1 is approximately one-third to one-half that of SGLT2 (3), suggesting that when more glucose is presented in the distal nephron because of SGLT2 inhibition, SGLT1 has the capacity to increase glucose reabsorption. In support of this hypothesis, Powell et al. (13) demonstrated that mice lacking both SGLT1 and SGLT2 exhibited 3-fold greater glycosuria than mice lacking SGLT2 alone. However, the reason for the marked reduction in glycosuria in those treated with these agents, as compared with what would be predicted by pharmacokinetic data on these agents, remains an important unanswered question.

The first SGLT inhibitor, phlorizin, which was later found to inhibit both SGLT1 and SGLT2, was a natural product isolated more than 175 years before the first agent in this class of drugs was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat diabetes. Phlorizin was first derived by de Koninck from the bark of the apple tree (Malus domestica) in 1835 (14). Due to its bitter taste and the previously observed antimalarial properties of extracts from the bark of other trees (Salix alba, the white willow, and Cinchona rubra, from which quinine was isolated), it was first surmised that phlorizin would have antipyretic, antipathogenic properties (15). Subsequent studies failed to confirm this presumption but quickly identified a highly reproducible effect of phlorizin: it increased glucose clearance markedly, causing subjects to produce high volumes of glucose-containing urine (16–18) and lowering blood glucose concentrations in subjects with diabetes (19). Phlorizin was listed in the Merck manual as a glycoside from the 1880s onward. Thus, the discovery of phlorizin and its capacity to promote glycosuria and glucose clearance preceded even the discovery of insulin as a glucose-lowering agent in 1921.

Subsequent studies on phlorizin's mechanism of action demonstrated that the drug inhibits glucose uptake into renal tubule cells (20), suggesting that this agent may exert its antihyperglycemic effect by reducing glucose reabsorption in the kidney. Indeed, phlorizin competitively inhibits SGLT2 at the brush border on the luminal membrane of renal proximal tubular cells, with an affinity for SGLT2 more than 1000 times that of glucose (21), while also inhibiting SGLT1 (22, 23), thereby reducing glucose reuptake throughout the proximal tubule.

These mechanistic insights into the action of phlorizin reinvigorated interest in developing SGLT-inhibiting agents to lower blood glucose in diabetes. Glucose toxicity on the β-cell (i.e. damage to the insulin-producing cells in the pancreas as a consequence of chronically high circulating glucose, which often occurs concordantly with lipotoxicity resulting from increased circulating lipids) has been identified as a key driver of the transition from insulin resistance to diabetes (24, 25). In support of this hypothesis, Rossetti et al. (26, 27) demonstrated that lowering the glucose load presented to the body, and thereby reducing systemic glucose toxicity, improved β-cell function and reversed insulin resistance in partially pancreatectomized, streptozotocin-treated diabetic rats. Subsequent studies of mice with a global genetic knockout of SGLT2 showed similar improvements: db/db SGLT2−/− mice exhibited lower plasma glucose concentrations, improved insulin sensitivity, and enhanced β-cell function (28, 29), which could be attributed to reductions in glucose toxicity without differences in body weight.

These data demonstrating the effect of SGLT inhibition or ablation to reverse systemic glucose toxicity refocused attention on their clinical development. Phlorizin's potential for clinical use was limited by its effects to reduce glucose uptake in the brain (30)—whether by inhibition of SGLTs (31, 32) or SGLT-like channels (33) or by its poor oral bioavailability (34–36). To address these limitations, investigators developed inhibitors specific to SGLT2, the expression of which is confined to the kidney (37). Canagliflozin, the first SGLT2 inhibitor on the market in the United States, was approved by the FDA for type 2 diabetes (T2D) in 2013. This agent and two other SGLT2 inhibitors developed later lower hemoglobin A1c by an average of 0.8 and 0.6% when used as monotherapy and added to combination therapy, respectively (38), in those with poorly controlled T2D. Pharmacokinetic and clinical parameters of the currently approved SGLT2 inhibitors are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Pharmacokinetic and clinical parameters of the three currently approved SGLT2 inhibitors

A1c-lowering effects refer to studies in which the SGLT2 inhibitor was given as an add-on to metformin (compared with metformin alone).

SGLT2 inhibitor–induced euglycemic ketoacidosis

The major risk of serious adverse events in those treated with SGLT2 inhibitors is ketoacidosis, a metabolic acidosis in which unrestrained production of ketone bodies, which are generated in a largely unregulated process through hepatic mitochondrial β-oxidation that occurs primarily as a consequence of increases in white adipose tissue (WAT) lipolysis, promotes a potentially lethal decrease (acidification) in blood pH. Treatment with an SGLT2 inhibitor increases the risk of ketoacidosis by 1.5–5-fold (39–41), with a recent meta-analysis finding an odds ratio for ketoacidosis of 2.13 (42). Notably, up to 70% of ketoacidosis episodes are euglycemic (43, 44), and the fatality rate for euglycemic ketoacidosis precipitated by SGLT2 inhibitors is 3-fold higher than that of all DKA (45, 46). Therefore, the risk of euglycemic ketoacidosis represents a significant, treatment-limiting risk of this class of agents.

Due in large part to the risk of ketoacidosis, SGLT2 inhibitors are prescribed with caution in those with T2D and are not FDA-approved for type 1 diabetes. To reap the glucose-lowering benefits of SGLT2 inhibitors—which avoid the risks of hypoglycemia that exist with insulin and sulfonylureas and the gastrointestinal side effects that can accompany metformin and glucagon-like peptide-1 agonists—there is great interest in understanding the mechanism by which SGLT2 inhibitors predispose to ketoacidosis. Early work focused on a potential role for glucagon in this process. Indeed, hyperglucagonemia—which is a hallmark of diabetic ketoacidosis (47–49)—has been observed in both humans (50–52) and rodents (53–56) following treatment with an SGLT2 inhibitor and has been suggested to play a major role in causing both ketoacidosis and increased hepatic glucose production. The putative role of glucagon in both processes is logical, given glucagon's clearly documented effects to promote hepatic gluconeogenesis (57–60), glycogenolysis (61–63), and intrahepatic lipolysis (57), but the mechanisms by which SGLT2 inhibitors increase circulating glucagon concentrations remains unclear. Whereas some early studies found that dapagliflozin increased glucagon release from the islet due to a direct effect on the α-cell (9, 54, 64), subsequent studies failed to replicate this finding and observed no significant effect of SGLT2 inhibitors to alter glucagon release from isolated islets in vitro (53, 65–67). In concert with this finding, isolated perfused islets from whole-body SGLT2 knockout mice did not exhibit any difference in glucagon secretion (28). These data represent a case in which in vivo data showing an increase in plasma glucagon concentrations in those treated with an SGLT2 inhibitor are dissociated from in vitro data documenting the lack of an effect of SGLT2 inhibitors to promote glucagon secretion from isolated islets and highlight the important of in vivo studies to assess the mechanism(s) by which SGLT2 inhibitors may regulate endocrine function.

WAT lipolysis and SGLT2 inhibitor–induced euglycemic ketoacidosis

An alternative mechanism for the effects of SGLT2 inhibitors to promote ketoacidosis is through stimulation of WAT lipolysis—an effect that likely could not be attributable to hyperglucagonemia, as numerous human (68–73) and rodent studies (57, 74) have argued against direct stimulation of white adipose tissue lipolysis by physiological and pathophysiological, as opposed to pharmacological, doses of glucagon when β-cell function is intact. However, increased WAT lipolysis is a hallmark of diabetic ketoacidosis (49, 75–78). WAT lipolysis promotes ketone production by supplying fatty acids that generate β-hydroxybutyrate, acetoacetate, and acetone as they are oxidized and increase gluconeogenesis due to increased supply of both glycerol (a gluconeogenic precursor that drives gluconeogenesis by a substrate push mechanism (79–81)) and acetyl-CoA (the end product of β-oxidation and an allosteric activator of the rate-controlling gluconeogenic enzyme pyruvate carboxylase (82–84)). Given that both ketogenesis (44, 53, 85–88) and increased rates of endogenous glucose production (51–53, 89–92) are observed after SGLT2 inhibitor treatment in humans and rodents, increased rates of lipolysis are a logical upstream explanation of both phenomena. Indeed, in a recent study, we observed that dapagliflozin more than doubled rates of in vivo WAT lipolysis in awake rats (53).

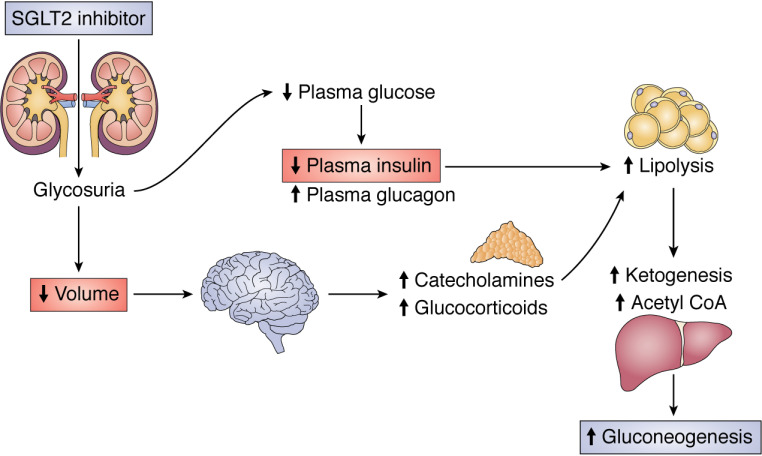

A critical question therefore is how do SGLT2 inhibitors activate WAT lipolysis. It is unlikely that SGLT2 inhibitor–induced WAT lipolysis occurs due to a direct effect of these agents on the adipose tissue, because SGLT2 is not expressed significantly in human adipose tissue (37, 93). We recently hypothesized an alternative mechanism for SGLT2 inhibitor–induced increases in WAT lipolysis causing euglycemic ketoacidosis (53).

We reasoned that dehydration (as occurs in a number of the precipitating causes of DKA, including alcohol use and gastrointestinal illness) may promote WAT lipolysis as a result of increased plasma catecholamine and/or corticosterone concentrations, which, in the setting of insulinopenia (as is expected in those on a low-carbohydrate diet and those experiencing an unplanned interruption of insulin delivery due to an insulin pump malfunction or those who substantially reduce their daily insulin dose due to the glucosuric effect of the SGLT2 inhibitor), results in increased WAT lipolysis, driving both increased gluconeogenesis and ketoacidosis (Fig. 2). Indeed, we found that dehydration increased both plasma catecholamine and corticosterone concentrations, resulting in increased rates of WAT lipolysis and endogenous glucose production (EGP) in both healthy control and diabetic rats—but that the increases in both WAT lipolysis and EGP required concomitant reductions in plasma insulin concentrations. Consistent with this two-hit hypothesis, rats treated with furosemide, which caused diuresis but did not lower plasma glucose or insulin concentrations, did not manifest increased rates of WAT lipolysis or ketogenesis or become ketoacidotic, despite equivalent weight loss due to dehydration. Infusing glucose to normalize plasma insulin concentrations to levels measured in control rats prevented increased rates of WAT lipolysis, increased ketogenesis, and ketoacidosis in dapagliflozin-treated rats (53).

Figure 2.

Two-hit hypothesis for the effect of SGLT2 inhibitors to promote euglycemic ketoacidosis via both predisposing to volume depletion and lowering plasma insulin concentrations.

Increases in rates of endogenous glucose production, which have been documented in rodents (53, 89, 90) and humans (50, 51, 91, 92), are an expected consequence of the increases in plasma glucagon concentrations that have been documented following acute and chronic SGLT2 inhibitor treatment. The increase in plasma glucagon following treatment with an SGLT2 inhibitor, which data reviewed in the previous section argue does not occur due to a direct effect on the α-cell, has been attributed to the glucose-lowering effect of these drugs (94) and may also be attributable to a direct effect of SGLT2 inhibition in the ventromedial hypothalamus, the activity of which has been shown to be critical to the hormonal counterregulatory response to hypoglycemia (95). Consistent with this possibility, blocking glucose utilization via injection of the nonmetabolizable glucose analog 2-deoxyglucose directly into the ventromedial hypothalamus promoted both glucagon and catecholamine secretion in rats (96). These data suggest that increased plasma glucagon concentrations could contribute to increased rates of gluconeogenesis by stimulating intrahepatic lipolysis (57) in this setting. However, a recent study in which subjects were treated with somatostatin to inhibit pancreatic islet hormone secretion of insulin and glucagon and were given an intravenous infusion of replacement basal insulin and glucagon demonstrated an insulin- and glucagon-independent effect of dapagliflozin to increase EGP in humans with T2D (97). In contrast, either blocking catecholamine and corticosterone action or infusing with saline to prevent dehydration fully abrogated the effect of dapagliflozin to increase EGP in rats, despite a lack of any difference in plasma glucagon concentrations (53). Taken together, these data point to a mechanism for SGLT2 inhibitor–induced diabetic ketoacidosis explained by the two-hit hypothesis: dehydration provokes increases in glucocorticoid and catecholamine concentrations, leading to WAT lipolysis in the setting of insulinopenia resulting from lower plasma glucose concentrations as a result of SGLT2 inhibitor–induced glucosuria. Consistent with this hypothesis, Blau et al. (44) found that viral illness (commonly gastroenteritis), alcohol use or abuse, and insulin pump malfunction or insulin dose reduction—each of which can lead to reduced caloric intake and insulin dose reduction—were observed in more than 70% of those who develop euglycemic ketoacidosis on an SGLT2 inhibitor (98–100). However, future studies will be required to mechanistically test whether two hits (insulinopenia and dehydration) are necessary and/or sufficient to promote ketoacidosis in humans treated with SGLT2 inhibitors.

SGLT2 inhibitors and heart failure

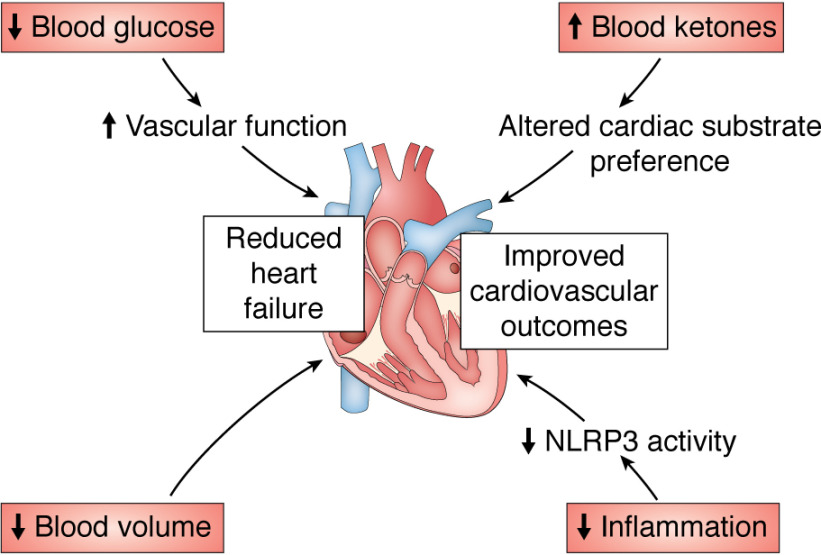

Perhaps the largest potential benefit of SGLT2 inhibitors in terms of morbidity and mortality benefits may be reduced heart failure and cardiovascular death. The EMPA-REG trial first identified an effect of the SGLT2 inhibitor empagliflozin to reduce heart failure incidence and mortality (101–103). This result, although surprising, is consistent with the fact that volume overload is a—if not the—critical predisposing factor to heart failure (104, 105). Encouragingly, multiple trials have demonstrated an effect for SGLT2 inhibitors to reduce overall mortality—and, in particular, both hospitalization and mortality from cardiovascular events—among patients with heart failure (39, 41, 106–113). Multiple hypotheses have emerged to explain the beneficial effect of SGLT2 inhibitors on cardiovascular outcomes (Fig. 3). Diabetes per se increases the risk of cardiovascular events and mortality (114–118), and poorer glucose control in those with diabetes predicts worse heart failure incidence and mortality (119, 120); thus, it is conceivable that the improved glycemic control observed in those on SGLT2 inhibitors could independently contribute to reduced cardiovascular mortality. However, the improvement in cardiovascular outcomes was observed very quickly after initiation of an SGLT2 inhibitor (generally between 3 months and 1 year) (39, 41, 103, 106, 108–111, 113), a time frame likely incompatible with either glucose-lowering or reversal of atherosclerosis as the primary beneficial mechanism. In addition, most studies (107, 112, 113, 121), with one exception (122), indicated that hemoglobin A1c did not correlate with cardiovascular outcomes in those treated with an SGLT2 inhibitor, and cardiovascular benefits were observed in nondiabetic humans (110) and rodents (123–125). These data, in concert with the fact that an SGLT2 inhibitor, canagliflozin, was more effective to improve cardiac outcomes than dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors, sulfonylureas, and GLP-1 agonists (112) despite similar glucose-lowering effects to dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors (38, 126–129) and less efficacy to lower glucose as compared with sulfonylureas (128, 130) and GLP-1 agonists (131, 132), argue against glycemic control as the primary mechanism by which SGLT2 inhibitors reduce cardiovascular risk. It remains an open question—with tremendous clinical relevance—how SGLT2 inhibitors improve cardiovascular function in individuals with diabetes.

Figure 3.

Proposed mechanisms by which SGLT2 inhibitors may reduce heart failure and improve cardiovascular outcomes.

Several competing hypotheses have emerged to explain the efficacy of SGLT2 inhibitors in reducing cardiovascular events and mortality. One intriguing explanation highlights the impact of SGLT2 inhibitors to generate a shift in substrate utilization systemically. Due to the glucose-wasting effect of these agents, SGLT2 inhibitors cause a shift in systemic glucose to fat utilization, as reflected by a decreased respiratory exchange ratio (87, 133–135). A related consequence of increased hepatic fat oxidation is the generation of ketones, which opens the intriguing possibility—which has been speculated about in the literature (136–138)—that a shift to increased ketone metabolism in the heart may yield direct cardiovascular benefits by modulating cardiomyocyte energy metabolism. This idea is supported by the fact that ketone perfusion improves energy generation (139, 140), a finding duplicated in diabetic mice treated with empagliflozin (140). Alternatively, recent work has highlighted an indirect mechanism by which SGLT2 inhibition may achieve improvements in cardiac function: Kim et al. (141) demonstrated that SGLT2 inhibitors reduce activity of the NLR family, pyrin domain-containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome, and that this anti-inflammatory effect may be attributable to increased ketones in concert with reduced insulin concentrations. As activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome worsens heart failure mortality (142), the effects of SGLT2 inhibition to suppress NLRP3 inflammasome activation secondary from reduced insulin and increased ketone concentrations would be predicted to improve outcomes. However, the substantial cardiac benefits observed with SGLT2 inhibitor treatment, despite the rare incidence of clinically significant ketosis, and the fact that ketone metabolism is already high in the failing heart, even without SGLT2 inhibitor treatment (143), highlight the high likelihood that additional mechanisms may also play a role. Because of the diuretic effect and consequent ability to lower blood pressure (129, 144–152), which may occur, at least in part, due to down-regulation of catecholamine activity in renal tissue (152), the clinical data suggest that reductions in blood pressure can partially—but not completely—explain improved cardiovascular outcomes in those on an SGLT2 inhibitor (153).

In concert with the cardiovascular benefits with SGLT2 inhibitor treatment, recent studies have also identified renal benefits associated with these agents. Improved glomerular filtration rates and urine albumin/creatinine ratio, a marker of renal function, have been observed in diabetic human subjects treated for 12–104 weeks with SGLT2 inhibitors (154–157). Additionally, those treated with SGLT2 inhibitors manifest lower rates of acute kidney injury in heart failure (154) and after a myocardial infarction (158). Whereas it is possible, given their mechanism, that the chronic effects of SGLT2 inhibition to improve cardiovascular outcomes are partially dependent on their ability to improve glycemic control in individuals with diabetes, the renal benefits were observed independent of any glucose-lowering effect (154, 156, 157) and, in the acute setting, are likely in large part attributable to the diuretic effect of SGLT2 inhibitors.

SGLT2 inhibitors and cancer

In recent years, investigators have also begun to study the potential effects of SGLT2 inhibitors on cancer in preclinical studies. In vitro studies have demonstrated that SGLT2 inhibitors, at high doses, inhibit cell division in liver (159–161), lung (162, 163), kidney (164), prostate (163), and breast cancer (165, 166) potentially by inhibiting tumor cell glucose uptake (161) and/or oxidation (167). Even more exciting, SGLT2 inhibitors inhibit tumor growth in vivo (159, 161, 164, 166, 168–172) by a mechanism that remains under debate. The finding that primary lung tumors—a tumor type in which SGLT2 inhibitors have been shown to slow tumor growth both in vitro (162, 163) and in vivo (171)—express SGLT2 (173, 174) suggests the possibility of a direct effect of SGLT2 inhibitors to inhibit tumor glucose uptake. Similarly, use of an SGLT-specific radioactive glucose analog, α-methyl-4-deoxy-4-[18F]fluoro-d-glucopyranoside, demonstrates functional SGLT activity in pancreatic and prostate tumors (175), tumor types in which, again, SGLT inhibitors have been shown to reduce cell proliferation in vitro (163, 176). These data suggest that, at least in these tumor types, SGLT2 inhibitors may act directly to reduce tumor glucose uptake. In addition, there is likely an indirect effect of SGLT2 inhibition to slow tumor growth in vivo by reducing circulating insulin as a result of its glucose-lowering effects. We recently showed that treatment with dapagliflozin slows colon and breast tumor growth in obese mice, associated with a 50% reduction in plasma insulin concentrations (168). As high circulating insulin (177) and exogenous insulin treatment (178) have been shown in meta-analyses to correlate with increased cancer risk in humans, and overexpression of the insulin receptor is a marker of cancer and a poor prognostic factor (179–186), the ability of SGLT2 inhibitors to reduce circulating insulin concentrations would be expected to slow tumor growth via this mechanism. Consistent with this hypothesis, chronic subcutaneous insulin infusion abrogated the effect of dapagliflozin to slow tumor growth in both models in our recent mouse study (168). These data do not necessarily contradict the possibility that SGLT2 inhibitors may also directly reduce tumor glucose uptake: it is possible that both mechanisms may be at play, but insulin infusion could compensate for the reduction in tumor glucose uptake through SGLT2, by promoting increases in glucose uptake via GLUT4. Regardless of the mechanism, there is clear justification for a clinical trial to explore the impact of SGLT2 inhibitors on cancer, particularly obesity-associated, insulin-responsive tumors. Surprisingly, at this time, there are only two trials posted on clinicaltrials.gov treating cancer patients with an SGLT2 inhibitor currently recruiting. Based on the wealth of preclinical data suggesting that SGLT2 inhibitors are effective against multiple cancer types with minimal toxicity, this represents an area of as-yet untapped potential to generate a new adjuvant therapeutic approach to cancer treatment.

Conclusion

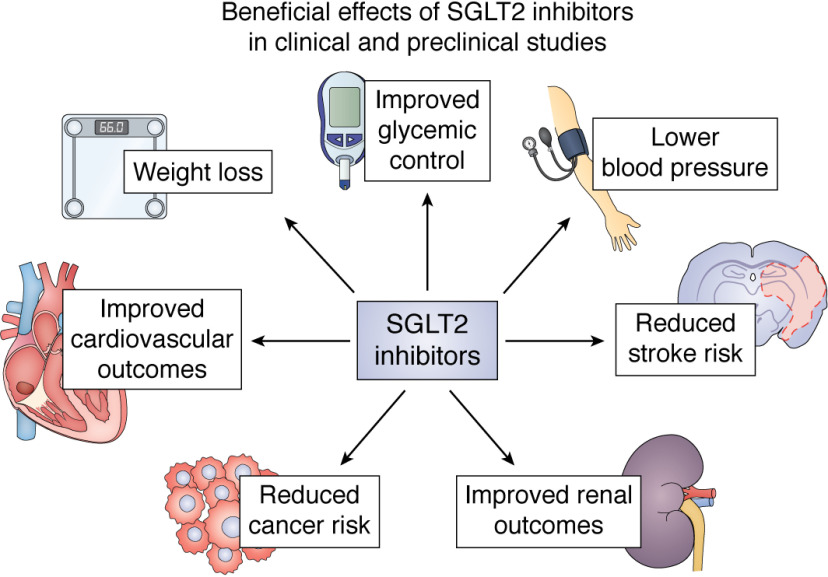

In summary, SGLT2 inhibitors are uniquely well-positioned to improve not only glycemic control in diabetes, but also, and likely independently of a direct effect of hyperglycemia, cardiovascular and renal health and perhaps cancer incidence and outcomes (Fig. 4). Whereas the risk of diabetic ketoacidosis must be considered, advances in understanding the pathogenesis of DKA in those taking an SGLT2 inhibitor as well as patient selection based on those at highest risk of this serious side effect will likely limit its incidence. However, as with any class of therapy, SGLT2 inhibitors must be prescribed carefully while considering potential risks as well as benefits. Mechanistic studies are needed to better understand how SGLT2 inhibitors yield their beneficial effects as well as how and in whom they may cause adverse events.

Figure 4.

Beneficial effects of SGLT2 inhibitors that have been observed in clinical and preclinical studies. Mechanistic trials to explain how these improvements may occur and how they may be interrelated are ongoing.

Funding and additional information—This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R00 CA215315, R01 DK113984, R01 DK116774, R01 DK119968, R01 DK114793, RC2 DK120534, and P30 DK045735 and an investigator-initiated award from AstraZeneca. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Conflict of interest—G. I. S. serves on the advisory boards for Merck, AstraZeneca, and Janssen Research and Development and receives investigator-initiated support from Merck and AstraZeneca, who manufacture SGLT2 inhibitors. G. I. S. is also a Scientific Co-Founder of TLC, Inc.

- SGLT

- sodium-glucose cotransporter

- FDA

- Food and Drug Administration

- DKA

- diabetic ketoacidosis

- T2D

- type 2 diabetes

- WAT

- white adipose tissue

- EGP

- endogenous glucose production.

References

- 1. Ransick A., Lindstrom N. O., Liu J., Zhu Q., Guo J. J., Alvarado G. F., Kim A. D., Black H. G., Kim J., and McMahon A. P. (2019) Single-cell profiling reveals sex, lineage, and regional diversity in the mouse kidney. Dev. Cell 51, 399–413.e7 10.1016/j.devcel.2019.10.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Horiba N., Masuda S., Takeuchi A., Takeuchi D., Okuda M., and Inui K. (2003) Cloning and characterization of a novel Na+-dependent glucose transporter (NaGLT1) in rat kidney. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 14669–14676 10.1074/jbc.M212240200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Abdul-Ghani M. A., DeFronzo R. A., and Norton L. (2013) Novel hypothesis to explain why SGLT2 inhibitors inhibit only 30–50% of filtered glucose load in humans. Diabetes 62, 3324–3328 10.2337/db13-0604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Vallon V., Platt K. A., Cunard R., Schroth J., Whaley J., Thomson S. C., Koepsell H., and Rieg T. (2011) SGLT2 mediates glucose reabsorption in the early proximal tubule. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 22, 104–112 10.1681/ASN.2010030246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Vallon V., and Thomson S. C. (2017) Targeting renal glucose reabsorption to treat hyperglycaemia: the pleiotropic effects of SGLT2 inhibition. Diabetologia 60, 215–225 10.1007/s00125-016-4157-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wright E. M., Loo D. D., and Hirayama B. A. (2011) Biology of human sodium glucose transporters. Physiol. Rev. 91, 733–794 10.1152/physrev.00055.2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Abdul-Ghani M. A., Norton L., and Defronzo R. A. (2011) Role of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT 2) inhibitors in the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Endocr. Rev. 32, 515–531 10.1210/er.2010-0029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kasichayanula S., Liu X., Lacreta F., Griffen S. C., and Boulton D. W. (2014) Clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of dapagliflozin, a selective inhibitor of sodium-glucose co-transporter type 2. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 53, 17–27 10.1007/s40262-013-0104-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pedersen M. G., Ahlstedt I., El Hachmane M. F., and Göpel S. O. (2016) Dapagliflozin stimulates glucagon secretion at high glucose: experiments and mathematical simulations of human A-cells. Sci. Rep. 6, 31214 10.1038/srep31214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Komoroski B., Vachharajani N., Boulton D., Kornhauser D., Geraldes M., Li L., and Pfister M. (2009) Dapagliflozin, a novel SGLT2 inhibitor, induces dose-dependent glucosuria in healthy subjects. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 85, 520–526 10.1038/clpt.2008.251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sha S., Devineni D., Ghosh A., Polidori D., Chien S., Wexler D., Shalayda K., Demarest K., and Rothenberg P. (2011) Canagliflozin, a novel inhibitor of sodium glucose co-transporter 2, dose dependently reduces calculated renal threshold for glucose excretion and increases urinary glucose excretion in healthy subjects. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 13, 669–672 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2011.01406.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Veltkamp S. A., Kadokura T., Krauwinkel W. J., and Smulders R. A. (2011) Effect of Ipragliflozin (ASP1941), a novel selective sodium-dependent glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitor, on urinary glucose excretion in healthy subjects. Clin. Drug Investig. 31, 839–851 10.1007/BF03256922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Powell D. R., DaCosta C. M., Gay J., Ding Z. M., Smith M., Greer J., Doree D., Jeter-Jones S., Mseeh F., Rodriguez L. A., Harris A., Buhring L., Platt K. A., Vogel P., Brommage R., et al. (2013) Improved glycemic control in mice lacking Sglt1 and Sglt2. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 304, E117–E130 10.1152/ajpendo.00439.2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Petersen C. (1835) Analyse des phloridzins. Ann. Acad. Sci. Fr. 15, 178–178 10.1002/jlac.18350150210 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15. de Koninck L. (1836) Observations sur les proprietes febrifuges de la phloridzine. Soc. Med. Gand 75, 110 [Google Scholar]

- 16. von Mering J. (1886) Ueber kunstlichen diabetes. Centralbl. Med. Wiss. xxii, 531 [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jolliffe N., Shannon J. A., and Smith H. W. (1932) The excretion of urine in the dog. I. The use of non-metabolized sugars in the measurement of glomerular filtrate. Am. J. Physiol. 100, 301–312 10.1152/ajplegacy.1932.100.2.301 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chasis H., Jolliffe N., and Smith H. W. (1933) The action of phlorizin on the excretion of glucose, xylose, sucrose, creatinine and urea by man. J. Clin. Invest. 12, 1083–1090 10.1172/JCI100559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Achard C., and Delamare V. (1899) The bark of the apple root, phlorizin, reduces diabetic hyperglycemia. Soc. Medic. Des Hospitaux 379–393 [Google Scholar]

- 20. Alvarado F., and Crane R. K. (1962) Phlorizin as a competitive inhibitor of the active transport of sugars by hamster small intestine, in vitro. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 56, 170–172 10.1016/0006-3002(62)90543-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Vick H., Diedrich D. F., and Baumann K. (1973) Reevaluation of renal tubular glucose transport inhibition by phlorizin analogs. Am. J. Physiol. 224, 552–557 10.1152/ajplegacy.1973.224.3.552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Smith C. D., Hirayama B. A., and Wright E. M. (1992) Baculovirus-mediated expression of the Na+/glucose cotransporter in Sf9 cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1104, 151–159 10.1016/0005-2736(92)90144-B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Panayotova-Heiermann M., Loo D. D., and Wright E. M. (1995) Kinetics of steady-state currents and charge movements associated with the rat Na+/glucose cotransporter. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 27099–27105 10.1074/jbc.270.45.27099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Weir G. C. (2020) Glucolipotoxicity, β-cells, and diabetes: the emperor has no clothes. Diabetes 69, 273–278 10.2337/db19-0138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lytrivi M., Castell A. L., Poitout V., and Cnop M. (2020) Recent insights into mechanisms of β-cell lipo- and glucolipotoxicity in type 2 diabetes. J. Mol. Biol. 432, 1514–1534 10.1016/j.jmb.2019.09.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rossetti L., Smith D., Shulman G. I., Papachristou D., and DeFronzo R. A. (1987) Correction of hyperglycemia with phlorizin normalizes tissue sensitivity to insulin in diabetic rats. J. Clin. Invest. 79, 1510–1515 10.1172/JCI112981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rossetti L., Shulman G. I., Zawalich W., and DeFronzo R. A. (1987) Effect of chronic hyperglycemia on in vivo insulin secretion in partially pancreatectomized rats. J. Clin. Invest. 80, 1037–1044 10.1172/JCI113157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jurczak M. J., Lee H. Y., Birkenfeld A. L., Jornayvaz F. R., Frederick D. W., Pongratz R. L., Zhao X., Moeckel G. W., Samuel V. T., Whaley J. M., Shulman G. I., and Kibbey R. G. (2011) SGLT2 deletion improves glucose homeostasis and preserves pancreatic beta-cell function. Diabetes 60, 890–898 10.2337/db10-1328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jurczak M. J., Saini S., Ioja S., Costa D. K., Udeh N., Zhao X., Whaley J. M., and Kibbey R. G. (2018) SGLT2 knockout prevents hyperglycemia and is associated with reduced pancreatic β-cell death in genetically obese mice. Islets 10, 181–189 10.1080/19382014.2018.1503027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Betz A. L., Drewes L. R., and Gilboe D. D. (1975) Inhibition of glucose transport into brain by phlorizin, phloretin and glucose analogues. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 406, 505–515 10.1016/0005-2736(75)90028-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yu A. S., Hirayama B. A., Timbol G., Liu J., Basarah E., Kepe V., Satyamurthy N., Huang S. C., Wright E. M., and Barrio J. R. (2010) Functional expression of SGLTs in rat brain. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 299, C1277–C1284 10.1152/ajpcell.00296.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yu A. S., Hirayama B. A., Timbol G., Liu J., Diez-Sampedro A., Kepe V., Satyamurthy N., Huang S. C., Wright E. M., and Barrio J. R. (2013) Regional distribution of SGLT activity in rat brain in vivo. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 304, C240–C247 10.1152/ajpcell.00317.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Matsuoka T., Nishizaki T., and Kisby G. E. (1998) Na+-dependent and phlorizin-inhibitable transport of glucose and cycasin in brain endothelial cells. J. Neurochem. 70, 772–777 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.70020772.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mather A., and Pollock C. (2010) Renal glucose transporters: novel targets for hyperglycemia management. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 6, 307–311 10.1038/nrneph.2010.38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Crespy V., Aprikian O., Morand C., Besson C., Manach C., Demigné C., and Rémésy C. (2001) Bioavailability of phloretin and phloridzin in rats. J. Nutr. 131, 3227–3230 10.1093/jn/131.12.3227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wang Z., Gao Z., Wang A., Jia L., Zhang X., Fang M., Yi K., Li Q., and Hu H. (2019) Comparative oral and intravenous pharmacokinetics of phlorizin in rats having type 2 diabetes and in normal rats based on phase II metabolism. Food Funct. 10, 1582–1594 10.1039/c8fo02242a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chen J., Williams S., Ho S., Loraine H., Hagan D., Whaley J. M., and Feder J. N. (2010) Quantitative PCR tissue expression profiling of the human SGLT2 gene and related family members. Diabetes Ther. 1, 57–92 10.1007/s13300-010-0006-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Vasilakou D., Karagiannis T., Athanasiadou E., Mainou M., Liakos A., Bekiari E., Sarigianni M., Matthews D. R., and Tsapas A. (2013) Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors for type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Intern. Med. 159, 262–274 10.7326/0003-4819-159-4-201308200-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Neal B., Perkovic V., Mahaffey K. W., de Zeeuw D., Fulcher G., Erondu N., Shaw W., Law G., Desai M., and Matthews D. R. and CANVAS Program Collaborative Group (2017) Canagliflozin and cardiovascular and renal events in type 2 diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 377, 644–657 10.1056/NEJMoa1611925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Perkovic V., Jardine M. J., Neal B., Bompoint S., Heerspink H. J. L., Charytan D. M., Edwards R., Agarwal R., Bakris G., Bull S., Cannon C. P., Capuano G., Chu P. L., de Zeeuw D., Greene T., et al. (2019) Canagliflozin and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N. Engl. J. Med. 380, 2295–2306 10.1056/NEJMoa1811744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wiviott S. D., Raz I., Bonaca M. P., Mosenzon O., Kato E. T., Cahn A., Silverman M. G., Zelniker T. A., Kuder J. F., Murphy S. A., Bhatt D. L., Leiter L. A., McGuire D. K., Wilding J. P. H., Ruff C. T., et al. (2019) Dapagliflozin and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 380, 347–357 10.1056/NEJMoa1812389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Liu J., Li L., Li S., Wang Y., Qin X., Deng K., Liu Y., Zou K., and Sun X. (2020) Sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitors and the risk of diabetic ketoacidosis in patients with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 22, 1619–1627 10.1111/dom.14075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Peters A. L., Buschur E. O., Buse J. B., Cohan P., Diner J. C., and Hirsch I. B. (2015) Euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis: a potential complication of treatment with sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibition. Diabetes Care 38, 1687–1693 10.2337/dc15-0843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Blau J. E., Tella S. H., Taylor S. I., and Rother K. I. (2017) Ketoacidosis associated with SGLT2 inhibitor treatment: analysis of FAERS data. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 33, e2924 10.1002/dmrr.2924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Benoit S. R., Zhang Y., Geiss L. S., Gregg E. W., and Albright A. (2018) Trends in diabetic ketoacidosis hospitalizations and in-hospital mortality—United States, 2000–2014. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 67, 362–365 10.15585/mmwr.mm6712a3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Dizon S., Keely E. J., Malcolm J., and Arnaout A. (2017) Insights into the recognition and management of SGLT2-inhibitor-associated ketoacidosis: it's not just euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis. Can. J. Diabetes 41, 499–503 10.1016/j.jcjd.2017.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Müller W. A., Faloona G. R., and Unger R. H. (1973) Hyperglucagonemia in diabetic ketoacidosis: its prevalence and significance. Am. J. Med. 54, 52–57 10.1016/0002-9343(73)90083-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Unger R. H., and Orci L. (1977) Role of glucagon in diabetes. Arch. Intern. Med. 137, 482–491 10.1001/archinte.1977.03630160050012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Miles J. M., Rizza R. A., Haymond M. W., and Gerich J. E. (1980) Effects of acute insulin deficiency on glucose and ketone body turnover in man: evidence for the primacy of overproduction of glucose and ketone bodies in the genesis of diabetic ketoacidosis. Diabetes 29, 926–930 10.2337/diab.29.11.926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ferrannini E., Muscelli E., Frascerra S., Baldi S., Mari A., Heise T., Broedl U. C., and Woerle H. J. (2014) Metabolic response to sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibition in type 2 diabetic patients. J. Clin. Invest. 124, 499–508 10.1172/JCI72227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Merovci A., Solis-Herrera C., Daniele G., Eldor R., Fiorentino T. V., Tripathy D., Xiong J., Perez Z., Norton L., Abdul-Ghani M. A., and DeFronzo R. A. (2014) Dapagliflozin improves muscle insulin sensitivity but enhances endogenous glucose production. J. Clin. Invest. 124, 509–514 10.1172/JCI70704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Martinez R., Al-Jobori H., Ali A. M., Adams J., Abdul-Ghani M., Triplitt C., DeFronzo R. A., and Cersosimo E. (2018) Endogenous glucose production and hormonal changes in response to canagliflozin and liraglutide combination therapy. Diabetes 67, 1182–1189 10.2337/db17-1278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Perry R. J., Rabin-Court A., Song J. D., Cardone R. L., Wang Y., Kibbey R. G., and Shulman G. I. (2019) Dehydration and insulinopenia are necessary and sufficient for euglycemic ketoacidosis in SGLT2 inhibitor-treated rats. Nat. Commun. 10, 548 10.1038/s41467-019-08466-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Bonner C., Kerr-Conte J., Gmyr V., Queniat G., Moerman E., Thévenet J., Beaucamps C., Delalleau N., Popescu I., Malaisse W. J., Sener A., Deprez B., Abderrahmani A., Staels B., and Pattou F. (2015) Inhibition of the glucose transporter SGLT2 with dapagliflozin in pancreatic α cells triggers glucagon secretion. Nat. Med. 21, 512–517 10.1038/nm.3828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Suga T., Kikuchi O., Kobayashi M., Matsui S., Yokota-Hashimoto H., Wada E., Kohno D., Sasaki T., Takeuchi K., Kakizaki S., Yamada M., and Kitamura T. (2019) SGLT1 in pancreatic α cells regulates glucagon secretion in mice, possibly explaining the distinct effects of SGLT2 inhibitors on plasma glucagon levels. Mol. Metab. 19, 1–12 10.1016/j.molmet.2018.10.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Fujikawa T., Berglund E. D., Patel V. R., Ramadori G., Vianna C. R., Vong L., Thorel F., Chera S., Herrera P. L., Lowell B. B., Elmquist J. K., Baldi P., and Coppari R. (2013) Leptin engages a hypothalamic neurocircuitry to permit survival in the absence of insulin. Cell Metab. 18, 431–444 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.08.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Perry R. J., Zhang D., Guerra M. T., Brill A. L., Goedeke L., Nasiri A. R., Rabin-Court A., Wang Y., Peng L., Dufour S., Zhang Y., Zhang X. M., Butrico G. M., Toussaint K., Nozaki Y., et al. (2020) Glucagon stimulates gluconeogenesis by INSP3R1-mediated hepatic lipolysis. Nature 579, 279–283 10.1038/s41586-020-2074-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Exton J. H., Jefferson L. S. Jr., Butcher R. W., and Park C. R. (1966) Gluconeogenesis in the perfused liver. The effects of fasting, alloxan diabetes, glucagon, epinephrine, adenosine 3',5'-monophosphate and insulin. Am. J. Med. 40, 709–715 10.1016/0002-9343(66)90151-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Exton J. H., and Park C. R. (1966) The stimulation of gluconeogenesis from lactate by epinephrine, glucagon, cyclic 3',5'-adenylate in the perfused rat liver. Pharmacol. Rev. 18, 181–188 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Exton J. H., and Park C. R. (1968) Control of gluconeogenesis in liver. II. Effects of glucagon, catecholamines, and adenosine 3',5'-monophosphate on gluconeogenesis in the perfused rat liver. J. Biol. Chem. 243, 4189–4196 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Sutherland E. W., and Cori C. F. (1948) Influence of insulin preparations on glycogenolysis in liver slices. J. Biol. Chem. 172, 737–750 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Sokal J. E., Sarcione E. J., and Henderson A. M. (1964) Relative potency of glucagon and epinephrine as hepatic glycogenolytic agents: studies with the isolated perfused rat liver. Endocrinology 74, 930–938 10.1210/endo-74-6-930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Jakob A., and Diem S. (1974) Activation of glycogenolysis in perfused rat livers by glucagon and metabolic inhibitors. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 362, 469–479 10.1016/0304-4165(74)90142-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Solini A., Sebastiani G., Nigi L., Santini E., Rossi C., and Dotta F. (2017) Dapagliflozin modulates glucagon secretion in an SGLT2-independent manner in murine alpha cells. Diabetes Metab. 43, 512–520 10.1016/j.diabet.2017.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Kuhre R. E., Ghiasi S. M., Adriaenssens A. E., Wewer Albrechtsen N. J., Andersen D. B., Aivazidis A., Chen L., Mandrup-Poulsen T., Ørskov C., Gribble F. M., Reimann F., Wierup N., Tyrberg B., and Holst J. J. (2019) No direct effect of SGLT2 activity on glucagon secretion. Diabetologia 62, 1011–1023 10.1007/s00125-019-4849-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Vergari E., Knudsen J. G., Ramracheya R., Salehi A., Zhang Q., Adam J., Asterholm I. W., Benrick A., Briant L. J. B., Chibalina M. V., Gribble F. M., Hamilton A., Hastoy B., Reimann F., Rorsman N. J. G., et al. (2019) Insulin inhibits glucagon release by SGLT2-induced stimulation of somatostatin secretion. Nat. Commun. 10, 139 10.1038/s41467-018-08193-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Knudsen J. G., Hamilton A., Ramracheya R., Tarasov A. I., Brereton M., Haythorne E., Chibalina M. V., Spegel P., Mulder H., Zhang Q., Ashcroft F. M., Adam J., and Rorsman P. (2019) Dysregulation of glucagon secretion by hyperglycemia-induced sodium-dependent reduction of ATP production. Cell Metab. 29, 430–442e434 10.1016/j.cmet.2018.10.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Gerich J. E., Lorenzi M., Bier D. M., Tsalikian E., Schneider V., Karam J. H., and Forsham P. H. (1976) Effects of physiologic levels of glucagon and growth hormone on human carbohydrate and lipid metabolism: studies involving administration of exogenous hormone during suppression of endogenous hormone secretion with somatostatin. J. Clin. Invest. 57, 875–884 10.1172/JCI108364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Wu M. S., Jeng C. Y., Hollenbeck C. B., Chen Y. D., Jaspan J., and Reaven G. M. (1990) Does glucagon increase plasma free fatty acid concentration in humans with normal glucose tolerance? J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 70, 410–416 10.1210/jcem-70-2-410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Jensen M. D., Heiling V. J., and Miles J. M. (1991) Effects of glucagon on free fatty acid metabolism in humans. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 72, 308–315 10.1210/jcem-72-2-308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Jeng C. Y., Sheu W. H., Jaspan J. B., Polonsky K. S., Chen Y. D., and Reaven G. M. (1993) Glucagon does not increase plasma free fatty acid and glycerol concentrations in patients with noninsulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 77, 6–10 10.1210/jcem.77.1.8100832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Gravholt C. H., Møller N., Jensen M. D., Christiansen J. S., and Schmitz O. (2001) Physiological levels of glucagon do not influence lipolysis in abdominal adipose tissue as assessed by microdialysis. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 86, 2085–2089 10.1210/jcem.86.5.7460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Bertin E., Arner P., Bolinder J., and Hagström-Toft E. (2001) Action of glucagon and glucagon-like peptide-1-(7-36) amide on lipolysis in human subcutaneous adipose tissue and skeletal muscle in vivo. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 86, 1229–1234 10.1210/jcem.86.3.7330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Hagen J. H. (1961) Effect of glucagon on the metabolism of adipose tissue. J. Biol. Chem. 236, 1023–1027 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Perry R. J., Peng L., Abulizi A., Kennedy L., Cline G. W., and Shulman G. I. (2017) Mechanism for leptin's acute insulin-independent effect to reverse diabetic ketoacidosis. J. Clin. Invest. 127, 657–669 10.1172/JCI88477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Perry R. J., Zhang X. M., Zhang D., Kumashiro N., Camporez J. P., Cline G. W., Rothman D. L., and Shulman G. I. (2014) Leptin reverses diabetes by suppression of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. Nat. Med. 20, 759–763 10.1038/nm.3579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Miles J. M., Haymond M. W., Nissen S. L., and Gerich J. E. (1983) Effects of free fatty acid availability, glucagon excess, and insulin deficiency on ketone body production in postabsorptive man. J. Clin. Invest. 71, 1554–1561 10.1172/jci110911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Voss T. S., Vendelbo M. H., Kampmann U., Pedersen S. B., Nielsen T. S., Johannsen M., Svart M. V., Jessen N., and Møller N. (2019) Substrate metabolism, hormone and cytokine levels and adipose tissue signalling in individuals with type 1 diabetes after insulin withdrawal and subsequent insulin therapy to model the initiating steps of ketoacidosis. Diabetologia 62, 494–503 10.1007/s00125-018-4785-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Previs S. F., Cline G. W., and Shulman G. I. (1999) A critical evaluation of mass isotopomer distribution analysis of gluconeogenesis in vivo. Am. J. Physiol. 277, E154–E160 10.1152/ajpendo.1999.277.1.E154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Shaw W. A., Issekutz T. B., and Issekutz B. Jr (1976) Gluconeogenesis from glycerol at rest and during exercise in normal, diabetic, and methylprednisolone-treated dogs. Metabolism 25, 329–339 10.1016/0026-0495(76)90091-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Landau B. R., Wahren J., Previs S. F., Ekberg K., Chandramouli V., and Brunengraber H. (1996) Glycerol production and utilization in humans: sites and quantitation. Am. J. Physiol. 271, E1110–E1117 10.1152/ajpendo.1996.271.6.E1110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Scrutton M. C., Keech D. B., and Utter M. F. (1965) Pyruvate carboxylase. IV. Partial reactions and the locus of activation by acetyl coenzyme A. J. Biol. Chem. 240, 574–581 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Utter M. F., Keech D. B., and Scrutton M. C. (1964) A possible role for acetyl CoA in the control of gluconeogenesis. Adv. Enzyme Regul. 2, 49–68 10.1016/S0065-2571(64)80005-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Perry R. J., Camporez J. G., Kursawe R., Titchenell P. M., Zhang D., Perry C. J., Jurczak M. J., Abudukadier A., Han M. S., Zhang X. M., Ruan H. B., Yang X., Caprio S., Kaech S. M., Sul H. S., et al. (2015) Hepatic acetyl CoA links adipose tissue inflammation to hepatic insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Cell 160, 745–758 10.1016/j.cell.2015.01.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Kaku K., Watada H., Iwamoto Y., Utsunomiya K., Terauchi Y., Tobe K., Tanizawa Y., Araki E., Ueda M., Suganami H., and Watanabe D. and Tofogliflozin 003 Study Group (2014) Efficacy and safety of monotherapy with the novel sodium/glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitor tofogliflozin in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a combined Phase 2 and 3 randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, parallel-group comparative study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 13, 65 10.1186/1475-2840-13-65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Ruderman N. B., Ross P. S., Berger M., and Goodman M. N. (1974) Regulation of glucose and ketone-body metabolism in brain of anaesthetized rats. Biochem. J. 138, 1–10 10.1042/bj1380001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Yokono M., Takasu T., Hayashizaki Y., Mitsuoka K., Kihara R., Muramatsu Y., Miyoshi S., Tahara A., Kurosaki E., Li Q., Tomiyama H., Sasamata M., Shibasaki M., and Uchiyama Y. (2014) SGLT2 selective inhibitor ipragliflozin reduces body fat mass by increasing fatty acid oxidation in high-fat diet-induced obese rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 727, 66–74 10.1016/j.ejphar.2014.01.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Taylor S. I., Blau J. E., and Rother K. I. (2015) SGLT2 inhibitors may predispose to ketoacidosis. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 100, 2849–2852 10.1210/jc.2015-1884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Solis-Herrera C., Daniele G., Alatrach M., Agyin C., Triplitt C., Adams J., Patel R., Gastaldelli A., Honka H., Chen X., Abdul-Ghani M., Cersosimo E., Del Prato S., and DeFronzo R. (2020) Increase in endogenous glucose production with SGLT2 inhibition is unchanged by renal denervation and correlates strongly with the increase in urinary glucose excretion. Diabetes Care 43, 1065–1069 10.2337/dc19-2177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. O'Brien T. P., Jenkins E. C., Estes S. K., Castaneda A. V., Ueta K., Farmer T. D., Puglisi A. E., Swift L. L., Printz R. L., and Shiota M. (2017) Correcting postprandial hyperglycemia in Zucker diabetic fatty rats with an SGLT2 inhibitor restores glucose effectiveness in the liver and reduces insulin resistance in skeletal muscle. Diabetes 66, 1172–1184 10.2337/db16-1410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Ferrannini E., Baldi S., Frascerra S., Astiarraga B., Heise T., Bizzotto R., Mari A., Pieber T. R., and Muscelli E. (2016) Shift to fatty substrate utilization in response to sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibition in subjects without diabetes and patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 65, 1190–1195 10.2337/db15-1356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Muscelli E., Astiarraga B., Barsotti E., Mari A., Schliess F., Nosek L., Heise T., Broedl U. C., Woerle H. J., and Ferrannini E. (2016) Metabolic consequences of acute and chronic empagliflozin administration in treatment-naive and metformin pretreated patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia 59, 700–708 10.1007/s00125-015-3845-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Uhlén M., Fagerberg L., Hallström B. M., Lindskog C., Oksvold P., Mardinoglu A., Sivertsson A., Kampf C., Sjöstedt E., Asplund A., Olsson I., Edlund K., Lundberg E., Navani S., Szigyarto C. A., et al. (2015) Proteomics: tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science 347, 1260419 10.1126/science.1260419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Lundkvist P., Pereira M. J., Kamble P. G., Katsogiannos P., Langkilde A. M., Esterline R., Johnsson E., and Eriksson J. W. (2019) Glucagon levels during short-term SGLT2 inhibition are largely regulated by glucose changes in patients with type 2 diabetes. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 104, 193–201 10.1210/jc.2018-00969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Borg W. P., During M. J., Sherwin R. S., Borg M. A., Brines M. L., and Shulman G. I. (1994) Ventromedial hypothalamic lesions in rats suppress counterregulatory responses to hypoglycemia. J. Clin. Invest. 93, 1677–1682 10.1172/JCI117150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Borg M. A., Sherwin R. S., Borg W. P., Tamborlane W. V., and Shulman G. I. (1997) Local ventromedial hypothalamus glucose perfusion blocks counterregulation during systemic hypoglycemia in awake rats. J. Clin. Invest. 99, 361–365 10.1172/JCI119165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Alatrach M., Laichuthai N., Martinez R., Agyin C., Ali A. M., Al-Jobori H., Lavynenko O., Adams J., Triplitt C., DeFronzo R., Cersosimo E., and Abdul-Ghani M. (2020) Evidence against an important role of plasma insulin and glucagon concentrations in the increase in EGP caused by SGLT2 inhibitors. Diabetes 69, 681–688 10.2337/db19-0770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Burke K. R., Schumacher C. A., and Harpe S. E. (2017) SGLT2 Inhibitors: a systematic review of diabetic ketoacidosis and related risk factors in the primary literature. Pharmacotherapy 37, 187–194 10.1002/phar.1881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Limenta M., Ho C. S. C., Poh J. W. W., Goh S. Y., and Toh D. S. L. (2019) Adverse drug reaction profile of SGLT2 inhibitor-associated diabetic ketosis/ketoacidosis in Singapore and their precipitating factors. Clin. Drug Investig. 39, 683–690 10.1007/s40261-019-00794-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Erondu N., Desai M., Ways K., and Meininger G. (2015) Diabetic ketoacidosis and related events in the canagliflozin type 2 diabetes clinical program. Diabetes Care 38, 1680–1686 10.2337/dc15-1251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Fitchett D., Inzucchi S. E., Lachin J. M., Wanner C., van de Borne P., Mattheus M., Johansen O. E., Woerle H. J., Broedl U. C., George J. T., Zinman B., and EMPA-REG OUTCOME Investigators (2018) Cardiovascular mortality reduction with empagliflozin in patients with type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 71, 364–367 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.11.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Verma S., Mazer C. D., Bhatt D. L., Raj S. R., Yan A. T., Verma A., Ferrannini E., Simons G., Lee J., Zinman B., George J. T., and Fitchett D. (2019) Empagliflozin and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and left ventricular hypertrophy: a subanalysis of the EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial. Diabetes Care 42, e42–e44 10.2337/dc18-1959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Zinman B., Wanner C., Lachin J. M., Fitchett D., Bluhmki E., Hantel S., Mattheus M., Devins T., Johansen O. E., Woerle H. J., Broedl U. C., Inzucchi S. E., and EMPA-REG OUTCOME Investigators (2015) Empagliflozin, cardiovascular outcomes, and mortality in type 2 diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 373, 2117–2128 10.1056/NEJMoa1504720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Miller W. L. (2016) Fluid volume overload and congestion in heart failure: time to reconsider pathophysiology and how volume is assessed. Circ. Heart Fail. 9, e002922 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.115.002922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Reddy Y. N. V., Melenovsky V., Redfield M. M., Nishimura R. A., and Borlaug B. A. (2016) High-output heart failure: a 15-year experience. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 68, 473–482 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.05.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. McMurray J. J. V., Solomon S. D., Inzucchi S. E., Køber L., Kosiborod M. N., Martinez F. A., Ponikowski P., Sabatine M. S., Anand I. S., Bělohlávek J., Böhm M., Chiang C.-E., Chopra V. K., de Boer R. A., Desai A. S., et al. (2019) Dapagliflozin in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction. N. Engl. J. Med. 381, 1995–2008 10.1056/NEJMoa1911303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Inzucchi S. E., Zinman B., Fitchett D., Wanner C., Ferrannini E., Schumacher M., Schmoor C., Ohneberg K., Johansen O. E., George J. T., Hantel S., Bluhmki E., and Lachin J. M. (2018) How does empagliflozin reduce cardiovascular mortality? Insights from a mediation analysis of the EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial. Diabetes Care 41, 356–363 10.2337/dc17-1096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Mahaffey K. W., Neal B., Perkovic V., de Zeeuw D., Fulcher G., Erondu N., Shaw W., Fabbrini E., Sun T., Li Q., Desai M., and Matthews D. R. and CANVAS Program Collaborative Group (2018) Canagliflozin for primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular events: results from the CANVAS Program (Canagliflozin Cardiovascular Assessment Study). Circulation 137, 323–334 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.032038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Kato E. T., Silverman M. G., Mosenzon O., Zelniker T. A., Cahn A., Furtado R. H. M., Kuder J., Murphy S. A., Bhatt D. L., Leiter L. A., McGuire D. K., Wilding J. P. H., Bonaca M. P., Ruff C. T., Desai A. S., et al. (2019) Effect of dapagliflozin on heart failure and mortality in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Circulation 139, 2528–2536 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.040130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Nassif M. E., Windsor S. L., Tang F., Khariton Y., Husain M., Inzucchi S. E., McGuire D. K., Pitt B., Scirica B. M., Austin B., Drazner M. H., Fong M. W., Givertz M. M., Gordon R. A., Jermyn R., et al. (2019) Dapagliflozin effects on biomarkers, symptoms, and functional status in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: the DEFINE-HF trial. Circulation 140, 1463–1476 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.042929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Matsutani D., Sakamoto M., Kayama Y., Takeda N., Horiuchi R., and Utsunomiya K. (2018) Effect of canagliflozin on left ventricular diastolic function in patients with type 2 diabetes. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 17, 73 10.1186/s12933-018-0717-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Patorno E., Goldfine A. B., Schneeweiss S., Everett B. M., Glynn R. J., Liu J., and Kim S. C. (2018) Cardiovascular outcomes associated with canagliflozin versus other non-gliflozin antidiabetic drugs: population based cohort study. BMJ 360, k119 10.1136/bmj.k119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Inzucchi S. E., Kosiborod M., Fitchett D., Wanner C., Hehnke U., Kaspers S., George J. T., and Zinman B. (2018) Improvement in cardiovascular outcomes with empagliflozin is independent of glycemic control. Circulation 138, 1904–1907 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.035759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Cubbon R. M., Woolston A., Adams B., Gale C. P., Gilthorpe M. S., Baxter P. D., Kearney L. C., Mercer B., Rajwani A., Batin P. D., Kahn M., Sapsford R. J., Witte K. K., and Kearney M. T. (2014) Prospective development and validation of a model to predict heart failure hospitalisation. Heart 100, 923–929 10.1136/heartjnl-2013-305294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Green J. B., Bethel M. A., Armstrong P. W., Buse J. B., Engel S. S., Garg J., Josse R., Kaufman K. D., Koglin J., Korn S., Lachin J. M., McGuire D. K., Pencina M. J., Standl E., Stein P. P., et al. (2015) Effect of sitagliptin on cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 373, 232–242 10.1056/NEJMoa1501352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Gotsman I., Shauer A., Lotan C., and Keren A. (2014) Impaired fasting glucose: a predictor of reduced survival in patients with heart failure. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 16, 1190–1198 10.1002/ejhf.146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Verma S., Sharma A., Zinman B., Ofstad A. P., Fitchett D., Brueckmann M., Wanner C., Zwiener I., George J. T., Inzucchi S. E., Butler J., and Mazer C. D. (2020) Empagliflozin reduces the risk of mortality and hospitalization for heart failure across thrombolysis in myocardial infarction risk score for heart failure in diabetes categories: post hoc analysis of the EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 22, 1141–1150 10.1111/dom.14015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Rawshani A., Rawshani A., and Gudbjörnsdottir S. (2017) Mortality and cardiovascular disease in type 1 and type 2 diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 377, 300–301 10.1056/NEJMc1706292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Engoren M., Schwann T. A., Arslanian-Engoren C., Maile M., and Habib R. H. (2013) U-shape association between hemoglobin A1c and late mortality in patients with heart failure after cardiac surgery. Am. J. Cardiol. 111, 1209–1213 10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.12.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Matsushita K., Blecker S., Pazin-Filho A., Bertoni A., Chang P. P., Coresh J., and Selvin E. (2010) The association of hemoglobin a1c with incident heart failure among people without diabetes: the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Diabetes 59, 2020–2026 10.2337/db10-0165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Zelniker T. A., Bonaca M. P., Furtado R. H. M., Mosenzon O., Kuder J. F., Murphy S. A., Bhatt D. L., Leiter L. A., McGuire D. K., Wilding J. P. H., Budaj A., Kiss R. G., Padilla F., Gause-Nilsson I., Langkilde A. M., et al. (2020) Effect of dapagliflozin on atrial fibrillation in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: insights from the DECLARE-TIMI 58 trial. Circulation 141, 1227–1234 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.044183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Shao H., Shi L., and Fonseca V. A. (2020) Using the BRAVO risk engine to predict cardiovascular outcomes in clinical trials with sodium-glucose transporter 2 inhibitors. Diabetes Care 43, 1530–1536 10.2337/dc20-0227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Cappetta D., De Angelis A., Ciuffreda L. P., Coppini R., Cozzolino A., Miccichè A., Dell'Aversana C., D'Amario D., Cianflone E., Scavone C., Santini L., Palandri C., Naviglio S., Crea F., Rota M., et al. (2020) Amelioration of diastolic dysfunction by dapagliflozin in a non-diabetic model involves coronary endothelium. Pharmacol. Res. 157, 104781 10.1016/j.phrs.2020.104781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Takasu T., and Takakura S. (2019) Effect of ipragliflozin, an SGLT2 inhibitor, on cardiac histopathological changes in a non-diabetic rat model of cardiomyopathy. Life Sci. 230, 19–27 10.1016/j.lfs.2019.05.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Sayour A. A., Korkmaz-Icöz S., Loganathan S., Ruppert M., Sayour V. N., Oláh A., Benke K., Brune M., Benkő R., Horváth E. M., Karck M., Merkely B., Radovits T., and Szabó G. (2019) Acute canagliflozin treatment protects against in vivo myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury in non-diabetic male rats and enhances endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation. J. Transl. Med. 17, 127 10.1186/s12967-019-1881-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Yang J., Tian Q., Tang Y., Shah A. K., Zhang R., Chen G., Zhang Y., Rajpathak S., and Hong T. (2018) Meta-analysis of HbA1c-lowering efficacy of dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors in combination with insulin in T2DM patients. Diabetes 67, 2302-PUB 10.2337/db18-2302-PUB [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Wu D., Li L., and Liu C. (2014) Efficacy and safety of dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors and metformin as initial combination therapy and as monotherapy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 16, 30–37 10.1111/dom.12174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Sherifali D., Nerenberg K., Pullenayegum E., Cheng J. E., and Gerstein H. C. (2010) The effect of oral antidiabetic agents on A1C levels: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Care 33, 1859–1864 10.2337/dc09-1727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Shao S. C., Chang K. C., Lin S. J., Chien R. N., Hung M. J., Chan Y. Y., Kao Yang Y. H., and Lai E. C. (2020) Favorable pleiotropic effects of sodium glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors: head-to-head comparisons with dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors in type 2 diabetes patients. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 19, 17 10.1186/s12933-020-0990-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Hirst J. A., Farmer A. J., Dyar A., Lung T. W., and Stevens R. J. (2013) Estimating the effect of sulfonylurea on HbA1c in diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetologia 56, 973–984 10.1007/s00125-013-2856-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Trujillo J. M., Nuffer W., and Ellis S. L. (2015) GLP-1 receptor agonists: a review of head-to-head clinical studies. Ther. Adv. Endocrinol. Metab. 6, 19–28 10.1177/2042018814559725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Kayaniyil S., Lozano-Ortega G., Bennett H. A., Johnsson K., Shaunik A., Grandy S., and Kartman B. (2016) A network meta-analysis comparing exenatide once weekly with other GLP-1 receptor agonists for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Ther. 7, 27–43 10.1007/s13300-016-0155-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Hoenig M., Clark M., Schaeffer D. J., and Reiche D. (2018) Effects of the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor velagliflozin, a new drug with therapeutic potential to treat diabetes in cats. J. Vet. Pharmacol. Ther. 41, 266–273 10.1111/jvp.12467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Liang Y., Arakawa K., Ueta K., Matsushita Y., Kuriyama C., Martin T., Du F., Liu Y., Xu J., Conway B., Conway J., Polidori D., Ways K., and Demarest K. (2012) Effect of canagliflozin on renal threshold for glucose, glycemia, and body weight in normal and diabetic animal models. PLoS ONE 7, e30555 10.1371/journal.pone.0030555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135. Osataphan S., Macchi C., Singhal G., Chimene-Weiss J., Sales V., Kozuka C., Dreyfuss J. M., Pan H., Tangcharoenpaisan Y., Morningstar J., Gerszten R., and Patti M. E. (2019) SGLT2 inhibition reprograms systemic metabolism via FGF21-dependent and -independent mechanisms. JCI Insight 4, 10.1172/jci.insight.123130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136. Mudaliar S., Alloju S., and Henry R. R. (2016) Can a shift in fuel energetics explain the beneficial cardiorenal outcomes in the EMPA-REG OUTCOME study? A unifying hypothesis. Diabetes Care 39, 1115–1122 10.2337/dc16-0542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137. Ferrannini E., Mark M., and Mayoux E. (2016) CV protection in the EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial: a “thrifty substrate” hypothesis. Diabetes Care 39, 1108–1114 10.2337/dc16-0330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138. Maejima Y. (2019) SGLT2 inhibitors play a salutary role in heart failure via modulation of the mitochondrial function. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 6, 186 10.3389/fmed.2019.00186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139. Ho K. L., Zhang L., Wagg C., Al Batran R., Gopal K., Levasseur J., Leone T., Dyck J. R. B., Ussher J. R., Muoio D. M., Kelly D. P., and Lopaschuk G. D. (2019) Increased ketone body oxidation provides additional energy for the failing heart without improving cardiac efficiency. Cardiovasc. Res. 115, 1606–1616 10.1093/cvr/cvz045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140. Verma S., Rawat S., Ho K. L., Wagg C. S., Zhang L., Teoh H., Dyck J. E., Uddin G. M., Oudit G. Y., Mayoux E., Lehrke M., Marx N., and Lopaschuk G. D. (2018) Empagliflozin increases cardiac energy production in diabetes: novel translational insights into the heart failure benefits of SGLT2 inhibitors. JACC Basic Transl. Sci. 3, 575–587 10.1016/j.jacbts.2018.07.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141. Kim S. R., Lee S. G., Kim S. H., Kim J. H., Choi E., Cho W., Rim J. H., Hwang I., Lee C. J., Lee M., Oh C. M., Jeon J. Y., Gee H. Y., Kim J. H., Lee B. W., et al. (2020) SGLT2 inhibition modulates NLRP3 inflammasome activity via ketones and insulin in diabetes with cardiovascular disease. Nat. Commun. 11, 2127 10.1038/s41467-020-15983-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142. Butts B., Gary R. A., Dunbar S. B., and Butler J. (2015) The importance of NLRP3 inflammasome in heart failure. J. Card. Fail. 21, 586–593 10.1016/j.cardfail.2015.04.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143. Lopaschuk G. D., and Verma S. (2016) Empagliflozin's fuel hypothesis: not so soon. Cell Metab. 24, 200–202 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.07.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144. Heymsfield S. B., Raji A., Gallo S., Liu J., Pong A., Hannachi H., and Terra S. G. (2020) Efficacy and safety of ertugliflozin in patients with overweight and obesity with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Obesity (Silver Spring) 28, 724–732 10.1002/oby.22748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145. Liu J., Tarasenko L., Pong A., Huyck S., Patel S., Hickman A., Mancuso J. P., Ellison M. C., Gantz I., and Terra S. G. (2020) Efficacy and safety of ertugliflozin in Hispanic/Latino patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 36, 1097–1106 10.1080/03007995.2020.1760227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146. Liu J., Tarasenko L., Pong A., Huyck S., Wu L., Patel S., Hickman A., Mancuso J. P., Gantz I., and Terra S. G. (2020) Efficacy and safety of ertugliflozin across racial groups in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 36, 1277–1284 10.1080/03007995.2020.1760228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147. Masuda T., Muto S., Fukuda K., Watanabe M., Ohara K., Koepsell H., Vallon V., and Nagata D. (2020) Osmotic diuresis by SGLT2 inhibition stimulates vasopressin-induced water reabsorption to maintain body fluid volume. Physiol. Rep. 8, e14360 10.14814/phy2.14360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148. Mazidi M., Rezaie P., Gao H. K., and Kengne A. P. (2017) Effect of sodium-glucose cotransport-2 inhibitors on blood pressure in people with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 43 randomized control trials with 22 528 patients. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 6, e004007 10.1161/jaha.116.004007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149. Baker W. L., Buckley L. F., Kelly M. S., Bucheit J. D., Parod E. D., Brown R., Carbone S., Abbate A., and Dixon D. L. (2017) Effects of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors on 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 6, e005686 10.1161/jaha.117.005686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150. Oliva R. V., and Bakris G. L. (2014) Blood pressure effects of sodium-glucose co-transport 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors. J. Am. Soc. Hypertens. 8, 330–339 10.1016/j.jash.2014.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151. Townsend R. R., Machin I., Ren J., Trujillo A., Kawaguchi M., Vijapurkar U., Damaraju C. V., and Pfeifer M. (2016) Reductions in mean 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure after 6-week treatment with canagliflozin in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and hypertension. J. Clin. Hypertens. (Greenwich) 18, 43–52 10.1111/jch.12747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152. Herat L. Y., Magno A. L., Rudnicka C., Hricova J., Carnagarin R., Ward N. C., Arcambal A., Kiuchi M. G., Head G. A., Schlaich M. P., and Matthews V. B. (2020) SGLT2 inhibitor-induced sympathoinhibition: a novel mechanism for cardiorenal protection. JACC Basic Transl. Sci. 5, 169–179 10.1016/j.jacbts.2019.11.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153. Shen Y., Zhou J., Shi L., Nauman E., Katzmarzyk P. T., Price-Haywood E. G., Horswell R., Chu S., Yang S., Bazzano A. N., Nigam S., and Hu G. (2020) Effectiveness of sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitors on ischaemic heart disease. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 22, 1197–1206 10.1111/dom.14025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154. Sugiyama S., Jinnouchi H., Yoshida A., Hieshima K., Kurinami N., Jinnouchi K., Tanaka M., Suzuki T., Miyamoto F., Kajiwara K., and Jinnouchi T. (2019) Renoprotective effects of additional SGLT2 inhibitor therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and chronic kidney disease stages 3b–4: a real world report from a Japanese specialized diabetes care center. J. Clin. Med. Res. 11, 267–274 10.14740/jocmr3761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155. Kadowaki T., Nangaku M., Hantel S., Okamura T., von Eynatten M., Wanner C., and Koitka-Weber A. (2019) Empagliflozin and kidney outcomes in Asian patients with type 2 diabetes and established cardiovascular disease: results from the EMPA-REG OUTCOME((R)) trial. J. Diabetes Investig. 10, 760–770 10.1111/jdi.12971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156. Sugiyama S., Jinnouchi H., Kurinami N., Hieshima K., Yoshida A., Jinnouchi K., Tanaka M., Nishimura H., Suzuki T., Miyamoto F., Kajiwara K., and Jinnouchi T. (2018) Impact of dapagliflozin therapy on renal protection and kidney morphology in patients with uncontrolled type 2 diabetes mellitus. J. Clin. Med. Res. 10, 466–477 10.14740/jocmr3419w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157. Dekkers C. C. J., Wheeler D. C., Sjöstrom C. D., Stefansson B. V., Cain V., and Heerspink H. J. L. (2018) Effects of the sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitor dapagliflozin in patients with type 2 diabetes and Stages 3b–4 chronic kidney disease. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 33, 2005–2011 10.1093/ndt/gfx350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158. Kuno A., Kimura Y., Mizuno M., Oshima H., Sato T., Moniwa N., Tanaka M., Yano T., Tanno M., Miki T., and Miura T. (2020) Empagliflozin attenuates acute kidney injury after myocardial infarction in diabetic rats. Sci. Rep. 10, 7238 10.1038/s41598-020-64380-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159. Jojima T., Wakamatsu S., Kase M., Iijima T., Maejima Y., Shimomura K., Kogai T., Tomaru T., Usui I., and Aso Y. (2019) The SGLT2 inhibitor canagliflozin prevents carcinogenesis in a mouse model of diabetes and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis-related hepatocarcinogenesis: association with SGLT2 expression in hepatocellular carcinoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 5237 10.3390/ijms20205237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]