Abstract

Aims

The United Nations warned of COVID-19-related mental health crisis; however, it is unknown whether there is an increase in the prevalence of mental disorders as existing studies lack a reliable baseline analysis or they did not use a diagnostic measure. We aimed to analyse trends in the prevalence of mental disorders prior to and during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

We analysed data from repeated cross-sectional surveys on a representative sample of non-institutionalised Czech adults (18+ years) from both November 2017 (n = 3306; 54% females) and May 2020 (n = 3021; 52% females). We used Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) as the main screening instrument. We calculated descriptive statistics and compared the prevalence of current mood and anxiety disorders, suicide risk and alcohol-related disorders at baseline and right after the first peak of COVID-19 when related lockdown was still in place in CZ. In addition, using logistic regression, we assessed the association between COVID-19-related worries and the presence of mental disorders.

Results

The prevalence of those experiencing symptoms of at least one current mental disorder rose from a baseline of 20.02 (95% CI = 18.64; 21.39) in 2017 to 29.63 (95% CI = 27.9; 31.37) in 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic. The prevalence of both major depressive disorder (3.96, 95% CI = 3.28; 4.62 v. 11.77, 95% CI = 10.56; 12.99); and suicide risk (3.88, 95% CI = 3.21; 4.52 v. 11.88, 95% CI = 10.64; 13.07) tripled and current anxiety disorders almost doubled (7.79, 95% CI = 6.87; 8.7 v. 12.84, 95% CI = 11.6; 14.05). The prevalence of alcohol use disorders in 2020 was approximately the same as in 2017 (10.84, 95% CI = 9.78; 11.89 v. 9.88, 95% CI = 8.74; 10.98); however, there was a significant increase in weekly binge drinking behaviours (4.07% v. 6.39%). Strong worries about both, health or economic consequences of COVID-19, were associated with an increased odds of having a mental disorder (1.63, 95% CI = 1.4; 1.89 and 1.42, 95% CI = 1.23; 1.63 respectively).

Conclusions

This study provides evidence matching concerns that COVID-19-related mental health problems pose a major threat to populations, particularly considering the barriers in service provision posed during lockdown. This finding emphasises an urgent need to scale up mental health promotion and prevention globally.

Key words: Anxiety, depression, COVID-19, mental disorders, prevalence, SARS-CoV-2, suicide risk

Introduction

As COVID-19 became a global pandemic, countries responded with nationwide lockdowns in attempt to slow and prevent further spread of the virus. With over half of the world population on some form of lockdown in April 2020, mental health of populations became a growing concern as individuals faced unprecedented levels of established mental health risk factors including social isolation, stress and anticipated economic hardship (Monroe and Simons, 1991; Mazure, 1998; Hammen, 2004; Ahnquist and Wamala, 2011; Matthews et al., 2016; Herbolsheimer et al., 2018; Economou et al., 2019; Brooks et al., 2020). These risk factors not only disproportionately affect individuals with a history of mental health problems (Hao et al., 2020; Yao et al., 2020), high-risk groups such as health care workers (Kang et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2020; Lu et al., 2020), COVID-19 patients and survivors (Zhang et al., 2020a), individuals with pre-existing chronic diseases (Ohliger et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020b) or unemployed individuals (Zhang et al., 2020b), but also could trigger the onset of mental disorders in previously healthy populations. Alarming statements by public health experts and the United Nations have expressed the concern that COVID-19 could contribute towards a major global mental health crisis (Galea et al., 2020; UN, 2020).

Evidence on the prevalence of COVID-19-related mental health problems is emerging. A nationwide online survey of participants from China recruited through convenience sampling (n = 1210) reported that 16.5% of individuals exhibited severe depressive symptoms, and 28.8% moderate to severe anxiety symptoms (Wang et al., 2020a). Another nationwide online survey using convenient sampling in China estimated that the prevalence of anxiety disorders, depressive symptoms and reduced sleep quality was 35.1, 20.1 and 18.2%, respectively (Huang and Zhao, 2020). An online study (n = 4872) from Wuhan, China, found a 48.3 and 22.6% prevalence of depression and anxiety among the general adult population (Gao et al., 2020). The largest study conducted in China (n = 52 730) found 35% of respondents experienced psychological distress as assessed by the COVID-19 Peritraumatic Distress Index (Qiu et al., 2020). Nationwide studies from Bangladesh (Al Banna et al., 2020) and Taiwan (Wong et al., 2020) showed high prevalence of anxiety and depressive symptoms as well.

In Europe, several waves of the UK Household Longitudinal Study conducted between 2018/2019 and April 2020 (i.e. after approximately 1 month of lockdown in the UK) were compared, and it was demonstrated that the prevalence of clinically significant levels of mental disorders, as measured by the 12-item General Health Questionnaire, increased from 18.9 to 27.3% (Pierce et al., 2020). A nationwide study from Italy using convenience sampling (n = 500) reported that 19.4 and 18.6% of participants experienced mild and moderate-to-severe psychological distress respectively (Moccia et al., 2020). In Spain, respondents (n = 3480) of an online survey reported high prevalence of depression (18.7%), anxiety (21.6%) and post-traumatic stress disorder (15.8%) (González-Sanguino et al., 2020). High prevalence of depression (23.6%) and anxiety (45.1%) were also found in respondents (n = 343) of an online survey in Turkey (Özdin and Özdin, 2020). The nationally representative online survey which reported a baseline comparison comes from Denmark (n = 2458), where the WHO-5 Well-being Index was utilised finding that the Danish population, and especially females, reported lower emotional well-being during the pandemic than in 2016 (Sønderskov et al., 2020). In addition, recently published data from the United States demonstrated elevated levels of mental health problems among US adults; the presence of both, anxiety or depressive symptoms was about three times higher in June 2020 than in the second quarter of 2019, and substance use and suicidal ideation was elevated as well (Czeisler et al., 2020).

While the evidence suggests that COVID-19 is affecting population health negatively, no existing study has measured the prevalence of COVID-19-related mental illness on a nationally representative sample using an established psycho-diagnostic instrument, and existing studies lack a reliable baseline analysis against which it compares the prevalence of mental disorders to. We aimed to conduct a study aligned with the published mental health research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic (Holmes et al., 2020), by assessing differences in the prevalence of current affective, anxiety and alcohol use disorders, and suicide risk screened using an established psycho-diagnostic instrument among a representative sample of Czech adults in 2017 and 2020.

Method

Setting

To assess the prevalence of current mental disorders in the Czech adult non-institutionalised population during the COVID-19 pandemic, we utilised data collected between 6th and 20th May 2020. In Czechia, the COVID-19-related nationwide state of emergency lasted from 12th March to the 17th of May, greatly impacting businesses and workers. During this period, services considered as non-essential by the Government of the Czech Republic were limited and citizens were under stay-at-home orders implemented on 16th March. Restrictions were gradually lifted, with businesses opening in waves according to their size and purpose (see the following reference for detailed introduction and easing of restrictions as well as for a list of essential services: Government of the Czech Republic, 2020). Since the psycho-diagnostic instrument used in this study assess whether the examined symptoms occurred in the period of last 2 weeks or more (see ‘Measurement’ for details), the obtained data reflect the period of the peak of COVID-19-related national emergency and the most severe associated restrictions within Czechia. This was the period immediately following the first peak of COVID-19 in CZ when stay-at-home orders were not in place anymore.

Data and participants

Since face-to-face data collection was not feasible during the state of emergency, we utilised a combination of computer-assisted telephone interviewing (CATI) and computer-assisted web interviewing (CAWI). Individuals aged 18 years and older were eligible to participate. Participants were sampled via randomly emailing (CAWI) or telephoning (CATI) to individuals registered in the online database of a data collection agency, while respecting the distribution of the Czech non-institutionalised adult population. While we obtained data from 3021 respondents, 907 of them were interviewed using CATI (response rate = 43%) and 2114 completed CAWI (response rate = 93%); each of these subsamples were representative for the Czech non-institutionalised adult population in terms of gender, age, education, size and region of residence. As the representativeness was established according to the last census that was conducted in 2011, we asked the data-collecting agency to adjust the sample to be in-line with the more recent distribution of population as per the latest Demographic Yearbook of the Czech Republic (CZSO, 2019). Thus, post-stratification weights were applied to the sample. All respondents provided oral informed consent and, at the end of the interview, they were informed about the emergency hotline providing psychological aid to Czech residents during the COVID-19 pandemic. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the National Institute of Mental Health, Czech Republic (registration number 127/20).

For our baseline analysis, we used data from the 2017 Czech Mental Health Study (CZEMS), which is described in detail elsewhere (Winkler et al., 2018a; Formánek et al., 2019). Briefly, eligibility criteria were the same as in 2020 survey, but the data were collected using the PAPI method and two-staged sampling, with a random sample of participants being selected from a random group of voting districts. The response rate was 75% and the final sample of 3306 respondents was representative of the Czech general population in terms of age, gender, education and region of residence. The description of the 2017 sample is provided in online Supplementary Table 1.

Measurement

In both the 2017 and 2020 surveys, we assessed the presence of mental disorders via the fifth version of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.), a psycho-diagnostic instrument which has demonstrated a high concordance with clinician-assessed diagnosis of mental disorders (Sheehan et al., 1997, 1998). We focused on the prevalence of current (as opposed to life-time) mental disorders; i.e. the presence of examined symptoms within the past 2 weeks for major depressive episode; the past month for panic, posttraumatic stress disorder, social phobia and suicide risk (low, medium or high risk); the past 6 months for generalised anxiety disorder (GAD); and the past 12 months for alcohol use disorders. For agoraphobia, no specific periods are specified in the M.I.N.I.

Since the diagnosis of alcohol use disorders require social dis-functioning (such as not going to work because of alcohol use), the chance of which is limited due to restrictions imposed during the lockdown, we measured also, usual consumption of alcohol (expressed in number of glasses per drinking session and examined separately for beer, wine and spirits) and the frequency of occurrence of binge drinking (at least five glasses of beer, wine or spirits per drinking session) in the last 12 months.

In addition, we assessed the following: consumption of prescription drugs (pain killers, sleeping pills, tranquilisers and stimulants) expressed as the number of drug categories consumed on daily basis; professional (i.e. psychiatrist/psychologist/general practitioner) mental health help-seeking in the last 12 months; COVID-19 health and economic-related worries (direct and indirect, see online Supplementary Appendix for details), expressed as the number of items with strong worries (min 0, max 2), and the presence of COVID-19 symptoms. All items were self-reported. The exact wording of COVID-19-related questions and the distribution of responses on these questions is provided in online Supplementary Table 2.

Statistical analysis

First, we calculated descriptive statistics for the sample, expressed as counts and percentages (%) for non-continuous variables, and as means with standard deviations (SD) for continuous variables. Second, we calculated the prevalence of mental disorders for 2017 and 2020. We expressed prevalence as weighted means with 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) estimated via bootstrap method with 10 000 replicates. To address the slightly higher proportion (approximately 2%) of women in the 2017 sample, we employed post-stratification weights for the 2017 dataset.

Finally, we performed logistic regression to assess whether COVID-19-related worries and the self-reported presence of COVID-19 symptoms were associated with the presence of (1) any mental disorder, (2) major depressive episode, (3) suicidality, (4) anxiety disorders and (5) alcohol use disorders in our 2020 sample. We controlled for age, gender, level of education, work status, marital status, size of residence and prescription drugs use in all models. We report results as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% CI, considering associations with p < 0.05 as statistically significant. We report the crude models adjusted for age and gender in online Supplementary Table 3. All analyses were performed using R statistical programming language (version 3.6.0).

Results

Detailed characteristics of both November 2017 and May 2020 samples are provided in Table 1. In 2020, approximately 10% of the sample reported using at least one type of prescription drugs on daily basis, while 1% reported using three to four different types. A considerable number of individuals (6.5%) expressed strong worries on both questions regarding the health consequences of COVID-19. Additionally, 8.5% of participants reported strong worries on both questions focused on the economic consequences of COVID-19. Approximately 2% of individuals reported having been tested (either positively or negatively) for COVID-19; and about 10% of the sample had visited a health professional regarding their mental health within the last 12 months.

Table 1.

Description of the 2017 and 2020 sample (unweighted)

| 2017 | 2020 | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender, n (%) | ||

| Males | 1532 (46.34) | 1440 (47.67) |

| Females | 1774 (53.66) | 1581 (52.33) |

| Age, mean (sd) | 48.82 (17.19) | 46.84 (16.02) |

| Education, n (%) | ||

| Elementary | 278 (8.41) | 180 (5.96) |

| Other than elementary | 3028 (91.59) | 2841 (94.04) |

| Marital status, n (%) | ||

| Other than married/living with a partner | 1314 (39.75) | 1243 (41.15) |

| Married/living with a partner | 1992 (60.25) | 1778 (58.85) |

| Employment status, n (%) | ||

| Employed, student, retired, receiving benefits | 3194 (96.61) | 2917 (96.56) |

| Unemployed | 112 (3.39) | 104 (3.44) |

| Size of residence, n (%) | ||

| 0–4999 | 1264 (38.23) | 1064 (35.22) |

| 5000–19 999 | 609 (18.42) | 573 (18.97) |

| 20 000–99 999 | 725 (21.93) | 671 (22.21) |

| 10 000 and more | 708 (21.42) | 713 (23.6) |

| Daily use of prescription drugs – number of drugs categories, n (%) | ||

| 0 | 3133 (94.77) | 2703 (89.47) |

| 1 | 132 (3.99) | 211 (6.98) |

| 2 | 28 (0.85) | 75 (2.48) |

| 3 | 10 (0.3) | 25 (0.83) |

| 4 | 3 (0.09) | 7 (0.23) |

| COVID-19 health-related worries – number of items with strong worries, n (%) | ||

| 0 | NAa | 2476 (81.96) |

| 1 | NA | 350 (11.59) |

| 2 | NA | 195 (6.45) |

| COVID-19 economic worries – number of items with strong worries, n (%) | ||

| 0 | NA | 2516 (83.28) |

| 1 | NA | 251 (8.31) |

| 2 | NA | 254 (8.41) |

| Presence of COVID-19, n (%) | ||

| Not tested | NA | 2961 (98.01) |

| Tested negative or positive | NA | 60 (1.99) |

| Received treatment in the last 12 months | ||

| No | 3122 (94.43) | 2725 (90.2) |

| Yes | 184 (5.57) | 296 (9.8) |

Not applicable.

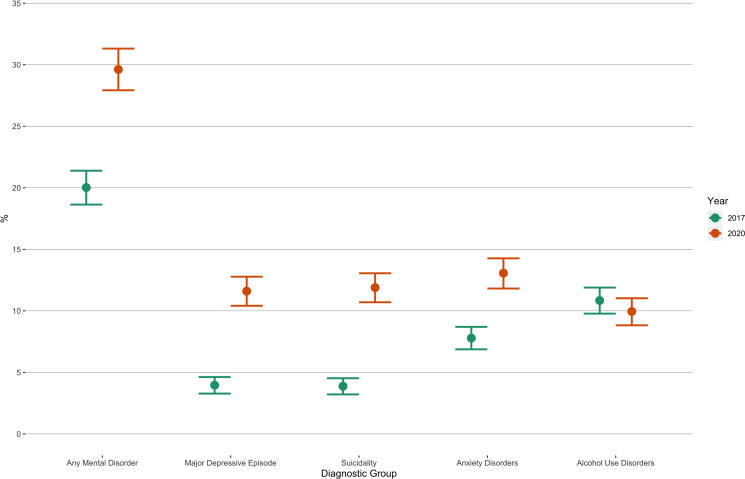

A detailed comparison of prevalence in 2017 and 2020 is presented in Table 2 and is graphically displayed in Fig. 1. The proportion of those experiencing symptoms of at least one current mental disorder increased during the COVID-19 pandemic by more than 10% (20.02, 95% CI = 18.64; 21.39 v. 29.63, 95% CI = 27.9; 31.37) when compared to the baseline in November 2017. While the prevalence of current affective disorders increased by almost 12.5% (6.57, 95% CI = 5.71; 7.4 v. 18.58, 95% CI = 17.09; 20.05), the prevalence of current anxiety disorders increased by approximately 6% (7.79, 95% CI = 6.87; 8.7 v. 12.84, 95% CI = 11.6; 14.05). The prevalence of alcohol use disorders in 2020 was approximately the same as in 2017 (10.84, 95% CI = 9.78; 11.89 v. 9.88, 95% CI = 8.74; 10.98); however, there was a significant increase in consumption of alcohol as measured by both, the number of glasses per drinking session for all examined beverages (beer 1.62 v. 1.8, wine 1.41 v. 1.62 and spirits 1.24 v. 1.32) as well as the number of individuals who binge drank at least once per week (4.07 v. 6.39%).

Table 2.

Prevalence of mental disorders per study years

| 2017 | 2020 | |

|---|---|---|

| Any mental disorder | 20.02 (18.64; 21.39) | 29.63 (27.9; 31.37) |

| Affective disorders | 6.57 (5.71; 7.4) | 18.58 (17.09; 20.05) |

| Anxiety disorders | 7.79 (6.87; 8.7) | 12.84 (11.6; 14.05) |

| Alcohol use disorders | 10.84 (9.78; 11.89) | 9.88 (8.74; 10.98) |

| Affective disorders | ||

| Major depressive episode | 3.96 (3.28; 4.62) | 11.77 (10.56; 12.99) |

| Suicidality | 3.88 (3.21; 4.52) | 11.88 (10.64; 13.07) |

| Anxiety disorders | ||

| Panic disorder | 0.21 (0.04; 0.36) | 0.88 (0.53; 1.18) |

| Generalised anxiety disorder | 3.14 (2.52; 3.72) | 5.17 (4.31; 5.95) |

| Agoraphobia | 5.16 (4.4; 5.91) | 7.99 (6.99; 9) |

| Social phobia | 1.67 (1.22; 2.09) | 2.53 (1.94; 3.07) |

| Posttraumatic stress disorder | 0.96 (0.61; 1.28) | 1.7 (1.23; 2.15) |

| Alcohol use disorder | ||

| Alcohol abuse | 9.42 (8.39; 10.41) | 7.85 (6.85; 8.79) |

| Alcohol dependence | 6.61 (5.72; 7.48) | 4.25 (3.49; 5) |

The results are expressed as weighted proportions (%) with weighted 95% CIs.

Fig. 1.

Prevalence of mental disorders among non-institutionalized adults in the Czech Republic: November 2017 and May 2020.

The main results of the logistic regression are provided in Table 3, and the results containing all associations in online Supplementary Table 4. Both strong worries from health and economic consequences of COVID-19 were associated with an increased risk for fulfilling the criteria of at least one mental disorder (1.63, 95% CI = 1.4; 1.89 and 1.42, 95% CI = 1.23; 1.63 respectively), major depressive episode (1.66, 95% CI = 1.38; 1.99 and 1.44, 95% CI = 1.21; 1.71), risk of suicide (1.43, 95% CI = 1.19; 1.72 and 1.37, 95% CI = 1.15; 1.62) and anxiety disorders (1.7, 95% CI = 1.42; 2.02 and 1.43, 95% CI = 1.2; 1.69). However, we found no statistically significant association between alcohol use disorders and health or economic COVID-19 worries. Having been tested (either negatively or positively) for COVID-19 was associated with elevated risk of at least one mental disorder (2.13, 95% CI = 1.21; 3.73), risk of suicide (2.36, 95% CI = 1.23; 4.32) and anxiety disorders (2.11, 95% CI = 1.08; 3.95), but not for major depressive episode or alcohol use disorders.

Table 3.

Logit regression models: an association of COVID-19-related covariates and the presence of mental disorders

| Any mental disorder | Major depressive episode | Suicidality | Anxiety disorders | Alcohol use disorders | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COVID-19 health-related worries | 1.63 (1.4; 1.89)*** | 1.66 (1.38; 1.99)*** | 1.43 (1.19; 1.72)*** | 1.7 (1.42; 2.02)*** | 1.12 (0.88; 1.41) |

| COVID-19 economic worries | 1.42 (1.23; 1.63)*** | 1.44 (1.21; 1.71)*** | 1.37 (1.15; 1.62)*** | 1.43 (1.2; 1.69)*** | 1.13 (0.91; 1.38) |

| Presence of COVID-19 | |||||

| Not tested | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Tested negative or positive | 2.13 (1.21; 3.73)* | 1.75 (0.87; 3.34) | 2.36 (1.23; 4.32)* | 2.11 (1.08; 3.95)* | 0.96 (0.39; 2.07) |

Models adjusted for age, gender, level of education, marital status, employment status, size of residence and use of prescription drugs. The results are expressed as ORs with 95% CIs.

*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Discussion

Our results confirm that the concerns expressed by experts and previous studies expressing mental health-related consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic pose a major threat to population health are real and alarming in the context of Czechia. We found an approximate 10% increase in the proportion of Czech adults fulfilling the criteria of at least one current mental disorder during the COVID-19 pandemic in May 2020 as compared to the baseline in November 2017.

The prevalence of affective disorders and anxiety disorders both increased, by 12.5 and 7%, respectively. While the prevalence of alcohol use disorders remained similar, the consumption of alcohol measured by both, number of glasses of beer, alcohol and spirits and binge drinking, was higher during the COVID-19 pandemics than prior. Strong worries related to health and economic consequences of COVID-19 were associated with considerably higher odds for at least one mental disorder, major depressive episode, suicide risk or anxiety disorders. In addition, having been tested for COVID-19, irrespective of test result (negatively or positively), was associated with a higher chance of scoring positively for at least one mental disorder and suicidality.

The sustained prevalence of alcohol use disorders at baseline and during the pandemic might partially be explained by limited possibilities of social dis-functioning during the lockdown, which is a diagnostic criterion of alcohol use disorders. For other mental disorders, the lockdown and other restrictive measures resulted in increased chances of positive scoring, because they had direct impact on population functioning and might negatively influence interest in hobbies or social activities, feelings of detachedness or isolation, feelings of tiredness, sleeping habits, or appetite, which are all symptoms used by M.I.N.I. to identify a presence of current mental disorder.

The sharp increase in the prevalence of current mental disorders supports the notion that population mental health is highly receptive to socio-economic factors. Similar phenomena have been researched in the context of the negative influence of the last financial crisis on completed suicides across Europe (Fountoulakis et al., 2014), and seem to be supported by emerging evidence related to the COVID-19 pandemics as well (Mamun and Ullah, 2020). The current study demonstrates significantly higher odds of current mental disorders among individuals who expressed health or economic worries associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. This supports a model of mental health problems existing along a continuum (Patel et al., 2018), where a considerable amount of the population experiences mild symptoms, leaving the population exceptionally vulnerable during stressful situations.

The increase in the prevalence of mental disorders from 2017 to 2020 in the Czech context should be interpreted taking into consideration the reform of mental health care and national efforts towards the deinstitutionalisation of mental health care (Winkler et al., 2017). As this study includes only community-dwelling participants, it might be argued that some confounding might occur because of an increased number of individuals with mental illness being based in the community. However this is largely unlikely as the target population for deinstitutionalisation are patients with psychosis (Winkler et al., 2018b), which were not included in the current study, and at most, patients with comorbidities in mental health diagnosis could be represented and contribute to the increased prevalence of people with mental illness in 2020 as compared to the 2017 baseline sample.

This study has several limitations. First, since this is not a cohort study, we could not assess whether the COVID-19 pandemic led to the development of mental disorders in individuals with no history of mental disorders. In addition, the baseline data collection was conducted in November 2017, which is about two and half year before the COVID-19 data collection, and this might increase a chance of confounding. Second, due to the extraordinary epidemiological situation caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, we were not able to collect data by means of a face-to-face interviewing, instead relying on CAWI and CATI methods. The use of these methods may have introduced selection bias as some demographics (i.e. individuals without phone and/or internet access) could not participate. Third, while assessing a presence of GAD, the psycho-diagnostic tool M.I.N.I. asks the following question: ‘Is the patient's anxiety restricted exclusively to, or better explained by, any disorder prior to this point?’ This question is intended for clinicians, and it makes sense when all of the modules of MINI are used, which was not the case in 2020. Hence, we relaxed this criterion, and this has led to a relatively high prevalence of GAD in both of our samples. Fourth, since the data were collected after the strictest lockdown measures had loosened, the full extent of COVID-related mental health problems may not be represented. Consequently, it is likely that at the peak of the pandemic and associated lockdown, mental health symptoms were even higher. In China, this was found in a study reporting the progression of mental health symptoms at multiple points over COVID-19, showing that the highest levels of mental health problems presented during the peak of virus spread and associated lockdowns (Wang et al., 2020a, 2020b). However, the study benefits from a considerably large number of participants, obtained using rigorous sampling, representative of the Czech adult general population. Second, we were able to compare our results to a baseline dataset collected prior to COVID-19, which measured the prevalence of mental illness using the same instrument on a similar population. Third, data collection for this study was finalised prior to the lifting of the most severe restrictions imposed by the government in response to COVID-19. Thus, the results of the study should be interpreted with existing contextual confounders within the Czech context, but are likely not biased by a return to society with new norms and regulations surrounding distancing and functioning.

Conclusions

This study provides data showing that projections and warnings of COVID-19-related mental health problems are backed by evidence, and are justified and warrant attention and action. Our study was conducted when the Czech government was lifting up restrictive measures and heading towards the end of state-of-emergency. This time also corresponds to improving epidemiological situation in continental Europe. It is possible that the prevalence of mental disorders in the general adult population could be higher during the culmination of the first peak, since the confusion and uncertainties were strongest then. However; with the threat of a second wave of COVID-19, services will need to be assessed, adapted and scaled to both meet the increased prevalence of individuals with mental health problems, and to adhere to new societal standards which parallel the pandemic including physical distancing measures, and lockdowns. Considering the existing treatment gap for mental disorders in the Czech context ranging from 61% for affective to 93% for alcohol use disorders in 2017 (Kagstrom et al., 2019), the increase in mental health problems poses additional burden on national efforts for comprehensive service provision and mental health reform initiatives.

Our findings showing doubling and tripling of the prevalence of common mental illnesses, which are in line with findings from UK (Pierce et al., 2020) and USA (Czeisler et al., 2020) also emphasise an urgent need to scale up mental health promotion and prevention globally, which includes integrating strategies to change mental health care in the wake of COVID-19 (Moreno et al., 2020). E-mental health has proved promising in delivering effective care to populations in diverse settings across the globe and scalable e-health interventions could be a major tool in meeting the surge of people with mental health problems (Wind et al., 2020). Continued mental health monitoring, early identification of at-risk individuals and ensuring accessible treatment for those with mental health problems will be vital aspects in service provision (Brooks et al., 2020; DePierro et al., 2020). On-going research assessing the prevalence, severity and progress in addressing mental health of populations will be necessary to track developments and inform priorities in mitigating the effects of COVID-19-related mental health consequences (Moreno et al., 2020).

Acknowledgements

None.

Author contributions

Petr Winkler initiated, planned and designed the study, coordinated the study, conducted the literature review and led the writing of the manuscript. Tomas Formanek planned and designed the study, conducted the statistical analyses, contributed to the literature review and wrote a substantial part of the manuscript. Karolina Mlada contributed to both designing the study and to the statistical analyses. Anna Kagstrom contributed to the literature review and writing of the manuscript. Zuzana Mohrova contributed to the statistical analysis. All authors, including Pavel Mohr and Ladislav Csémy, contributed to the interpretation of the results and to the writing of the manuscript.

Financial support

The study was supported by the project the project ‘Sustainability for the National Institute of Mental Health’, LO1611, Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic under the NPU I programme. The funder had no role whatsoever in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report and in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Ethical standards

Ethical approval was obtained from the ethical committee of the National Institute of Mental Health, Czech Republic.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796020000888.

click here to view supplementary material

Data

Data are not available publicly because of government regulations; however, data will be made available upon a reasonable request. Similarly, the R code will be made available upon a reasonable request.

Conflict of interest

Authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Ahnquist J and Wamala SP (2011) Economic hardships in adulthood and mental health in Sweden. the Swedish National Public Health Survey 2009. BMC Public Health 11, 788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al Banna MH, Sayeed A, Kundu S, Christopher E, Hasan MT, Begum MR, Dola STI, Hassan MM, Chowdhury S and Khan MSI (2020) The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of the adult population in Bangladesh: a nationwide cross-sectional study. International Journal of Environmental Health Research, 10.1080/09603123.2020.1802409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, Woodland L, Wessely S, Greenberg N and Rubin GJ (2020) The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. The Lancet 395, 912–920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czeisler MÉ, Lane RI, Petrosky E, Wiley JF, Christensen A, Njai R, Weaver MD, Robbins R, Facer-Childs ER, Barger LK, Czeisler CA, Howard ME and Rajaratnam SMW (2020) Mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic – United States, June 24–30, 2020. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 69, 1049–1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CZSO (2019) Demographic Yearbook of the Czech Republic 2018. Prague: Czech Statistical Office. [Google Scholar]

- Depierro J, Lowe S and Katz C (2020) Lessons learned from 9/11: mental health perspectives on the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Research 288, 113024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Economou M, Peppou LE, Souliotis K, Konstantakopoulos G, Papaslanis T, Kontoangelos K, Nikolaidi S and Stefanis N (2019) An association of economic hardship with depression and suicidality in times of recession in Greece. Psychiatry Research 279, 172–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Formánek T, Kagström A, Cermakova P, Csémy L, Mladá K and Winkler P (2019) Prevalence of mental disorders and associated disability: results from the cross-sectional Czech mental health study (CZEMS). European Psychiatry 60, 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fountoulakis KN, Kawohl W, Theodorakis PN, Kerkhof AJ, Navickas A, Höschl C, Lecic-Tosevski D, Sorel E, Rancans E, Palova E, Juckel G, Isacsson G, Korosec Jagodic H, Botezat-Antonescu I, Warnke I, Rybakowski J, Azorin JM, Cookson J, Waddington J, Pregelj P, Demyttenaere K, Hranov LG, Stevovic LI, Pezawas L, Adida M, Figuera ML, Pompili M, Jakovljević M, Vichi M, Perugi G, Andreassen O, Vukovic O, Mavrogiorgou P, Varnik P, Bech P, Dome P, Winkler P, Salokangas RKR, From T, Danileviciute V, Gonda X, Rihmer Z, Benhalima JF, Grady A, Kloster Leadholm AK, Soendergaard S, Nordt C and Lopez-Ibor J (2014) Relationship of suicide rates to economic variables in Europe: 2000–2011. The British Journal of Psychiatry 205, 486–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galea S, Merchant RM and Lurie N (2020) The mental health consequences of COVID-19 and physical distancing: the need for prevention and early intervention. JAMA Internal Medicine 180, 817–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao J, Zheng P, Jia Y, Chen H, Mao Y, Chen S, Wang Y, Fu H and Dai J (2020) Mental health problems and social media exposure during COVID-19 outbreak. PLoS ONE 15, e0231924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Sanguino C, Ausín B, Ángelcastellanos M, Saiz J, López-Gómez A, Ugidos C and Muñoz M (2020) Mental health consequences during the initial stage of the 2020 coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) in Spain. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity 87, 172–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Government of the Czech Republic (2020) Measures adopted by the Czech Government against the coronavirus. Available at https://www.vlada.cz/en/media-centrum/aktualne/measures-adopted-by-the-czech-government-against-coronavirus-180545/ (Accessed 3 June 2020).

- Hammen C (2004). Stress and depression. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology 1, 293–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao F, Tan W, Jiang L, Zhang L, Zhao X, Zou Y, Hu Y, Luo X, Jiang X, McIntyre RS and Tran B (2020) Do psychiatric patients experience more psychiatric symptoms during COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown? A case-control study with service and research implications for immunopsychiatry. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity 87, 100–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbolsheimer F, Ungar N and Peter R (2018) Why is social isolation among older adults associated with depressive symptoms? The mediating role of out-of-home physical activity. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine 25, 649–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes EA, O'Connor RC, Perry VH, Tracey I, Wessely S, Arseneault L, Ballard C, Christensen H, Cohen Silver R, Everall I, Ford T, John A, Kabir T, King K, Madan I, Michie S, Przybylski AK, Shafran R, Sweeney A, Worthman CM, Yardley L, Cowan K, Cope C, Hotopf M and Bullmore, E (2020) Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: a call for action for mental health science. The Lancet Psychiatry 7, 547–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y and Zhao N (2020) Chinese Mental health burden during the COVID-19 pandemic. Asian Journal of Psychiatry 51, 102052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Kagstrom A, Alexova A, Tuskova E, Csajbók Z, Schomerus G, Formanek T, Mladá K, Winkler P and Cermakova P (2019) The treatment gap for mental disorders and associated factors in the Czech Republic. European Psychiatry 59, 37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang L, Ma S, Chen M, Yang J, Wang Y, Li R, Yao L, Bai H, Cai Z and Yang BX (2020) Impact on mental health and perceptions of psychological care among medical and nursing staff in Wuhan during the 2019 novel coronavirus disease outbreak: a cross-sectional study. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity 87, 11–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Zhou M, Zhu X, Gu X, Ma Z and Zhang W (2020) Risk and protective factors for chronic pain following inguinal hernia repair: a retrospective study. Journal of Anesthesia 34, 330–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu W, Wang H, Lin Y and Li L (2020) Psychological status of medical workforce during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. Psychiatry Research 288, 112936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamun MA and Ullah I (2020) COVID-19 suicides in Pakistan, dying off not COVID-19 fear but poverty? – The forthcoming economic challenges for a developing country. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity 87, 163–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews T, Danese A, Wertz J, Odgers CL, Ambler A, Moffitt TE and Arseneault L (2016) Social isolation, loneliness and depression in young adulthood: a behavioural genetic analysis. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 51, 339–348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazure CM (1998) Life stressors as risk factors in depression. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice 5, 291–313. [Google Scholar]

- Moccia L, Janiri D, Pepe M, Dattoli L, Molinaro M, De Martin V, Chieffo D, Janiri L, Fiorillo A and Sani G (2020) Affective temperament, attachment style, and the psychological impact of the COVID-19 outbreak: an early report on the Italian general population. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity 87, 75–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monroe SM and Simons AD (1991) Diathesis-stress theories in the context of life stress research: Implications for the depressive disorders. Psychological Bulletin 110, 406–425. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.110.3.406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno C, Wykes T, Galderisi S, Nordentoft M, Crossley N, Cannon M, Correll CU, Byrne L, Carr S, Chen EYH, Gorwood P, Johnson S, Kärkkäinen H, Krystal JH, Lee J, Lieberman J, López-Jaramillo C, Männikkö M, Phillips MR, Uchida H, Vieta E, Vita A and Arango C (2020) How mental health care should change as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet Psychiatry 7, 813–824. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30307-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohliger E, Umpierrez E, Buehler L, Ohliger AW, Magister S, Vallier H and Hirschfeld AG (2020) Mental health of orthopaedic trauma patients during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic. International Orthopaedics, 1–5. doi: 10.1007/s00264-020-04711-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Özdin S and Özdin BŞ (2020) Levels and predictors of anxiety, depression and health anxiety during COVID-19 pandemic in Turkish society: the importance of gender. International Journal of Social Psychiatry 66, 504–511. doi: 10.1177/0020764020927051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel V, Saxena S, Lund C, Thornicroft G, Baingana F, Bolton P, Chisholm D, Collins PY, Coope JL, Eaton J and Herrman H (2018) The lancet commission on global mental health and sustainable development. The Lancet 392, 1553–1598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce M, Hope H, Ford T, Hatch S, Hotopf M, John A, Kontopantelis E, Webb R, Wessely S, McManus S and Abel KM (2020) Mental health before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal probability sample survey of the UK population. The Lancet Psychiatry 7, 883–892. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30308-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu J, Shen B, Zhao M, Wang Z, Xie B and Xu Y (2020) A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: implications and policy recommendations. General Psychiatry 33, e100213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Janavs J, Weiller E, Keskiner A, Schinka J, Knapp E, Sheehan MF and Dunbar GC (1997) The validity of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) according to the SCID-P and its reliability. European Psychiatry 12, 232–241. [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, Hergueta T, Baker R and Dunbar GC (1998) The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 59, 22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sønderskov KM, Dinesen PT, Santini ZI and Østergaard SD (2020) The depressive state of Denmark during the COVID-19 pandemic. Acta Neuropsychiatrica 32, 226–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UN (2020) Policy brief: COVID-19 and the Need for Action on Mental Health.

- Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, Tan Y, Xu L, McIntyre RS, Choo FN, Tran B, Ho R and Sharma VK (2020a) A longitudinal study on the mental health of general population during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity 87, 40–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Duan Z, Ma Z, Mao Y, Li X, Wilson A, Qin H, Ou J, Peng K, Zhou F, Li C, Liu Z and Chen R (2020b) Epidemiology of mental health problems among patients with cancer during COVID-19 pandemic. Translational Psychiatry 10, 263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wind TR, Rijkeboer M, Andersson G and Riper H (2020) The COVID-19 pandemic: the ‘black swan’ for mental health care and a turning point for e-health. Internet Interventions 20. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2020.100317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler P, Krupchanka D, Roberts T, Kondratova L, Machů V, Höschl C, Sartorius N, Van Voren R, Aizberg O, Bitter I, Cerga-Pashoja A, Deljkovic A, Fanaj N, Germanavicius A, Hinkov H, Hovsepyan A, Ismayilov FN, Ivezic SS, Jarema M, Jordanova V, Kukić S, Makhashvili N, Šarotar BN, Plevachuk O, Smirnova D, Voinescu BI, Vrublevska J and Thornicroft G (2017) A blind spot on the global mental health map: a scoping review of 25 years’ development of mental health care for people with severe mental illnesses in central and Eastern Europe. The Lancet Psychiatry 4, 634–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler P, Formánek T, Mladá K and Cermakova P (2018a) The CZEch Mental health Study (CZEMS): study rationale, design, and methods. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 27, e1728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler P, Koeser L, Kondrátová L, Broulíková HM, Páv M, Kališová L, Barrett B and McCrone P (2018b) Cost-effectiveness of care for people with psychosis in the community and psychiatric hospitals in the Czech Republic: an economic analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry 5, 1023–1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong LP, Hung CC, Alias H and Lee TSH (2020) Anxiety symptoms and preventive measures during the COVID-19 outbreak in Taiwan. BMC Psychiatry 20, pp. 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao H, Chen JH and Xu YF (2020) Patients with mental health disorders in the COVID-19 epidemic. The Lancet Psychiatry 7, e21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Lu H, Zeng H, Zhang S, Du Q, Jiang T and Du B (2020a) The differential psychological distress of populations affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity 87, 49–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang SX, Wang Y, Rauch A and Wei F (2020b) Unprecedented disruption of lives and work: health, distress and life satisfaction of working adults in China one month into the COVID-19 outbreak. Psychiatry Research 112958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796020000888.

click here to view supplementary material

Data Availability Statement

Data are not available publicly because of government regulations; however, data will be made available upon a reasonable request. Similarly, the R code will be made available upon a reasonable request.