Abstract

Background:

Multimorbidity is rising in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). However, the evidence on its epidemiology from LMICs settings is limited and the available literature has not been synthesized as yet.

Objectives:

To review the available evidence on the epidemiology of multimorbidity in LMICs.

Methods:

PubMed, Scopus, PsycINFO and Grey literature databases were searched. We followed the PRISMA-ScR reporting guideline.

Results:

Of 33, 110 articles retrieved, 76 studies were eligible for the epidemiology of multimorbidity. Of these 76 studies, 66 (86.8%) were individual country studies. Fifty-two (78.8%) of which were confined to only six middle-income countries: Brazil, China, South Africa, India, Mexico and Iran. The majority (n = 68, 89.5%) of the studies were crosssectional in nature. The sample size varied from 103 to 242, 952. The largest proportion (n = 33, 43.4%) of the studies enrolled adults. Marked variations existed in defining and measuring multimorbidity. The prevalence of multimorbidity in LMICs ranged from 3.2% to 90.5%.

Conclusion and Recommendations:

Studies on the epidemiology of multimorbidity in LMICs are limited and the available ones are concentrated in few countries. Despite variations in measurement and definition, studies consistently reported high prevalence of multimorbidity. Further research is urgently required to better understand the epidemiology of multimorbidity and define the best possible interventions to improve outcomes of patients with multimorbidity in LMICs.

Keywords: Multimorbidity, LMICs, scoping, epidemiology

Introduction

Multimorbidity often refers to the presence of two or more or three or more chronic conditions in a given individual.1,2 Multimorbidity is a growing issue and posing a major challenge to health care systems around the world.3 Global prevalence estimates ranged from 12.9% (in the general population) to 95.1% (among people 65 years and older).4 A large difference in the prevalence of multimorbidity was observed across studies conducted both in primary care (3.5% to 98.5%) and in the general population (13.1% to 71.8%).5 Evidence shows a rising trend in the prevalence of multimorbidity in the low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).3

Demographic changes such as population aging is contributing for the development of multimorbidity of chronic conditions.3 Multimorbidity is also socially patterned, where a higher prevalence is observed among socioeconomically deprived populations than their wealthier counterparts in high income countries (HICs).6,7 Similarly, women are more likely than men to have higher odds of multimorbidity.4,8 Individual lifestyle factors including obesity,9 physical inactivity,10,11 harmful use of alcohol,12 and psychosocial factors, such as negative life events and believing in external locus of control are also factors associated with multimorbidity.13,14

Living with multimorbidity is associated with disability, lower quality of life, premature mortality, greater use of health care service resources and unplanned hospital admissions.1,15 Management of multimorbidity is much more complicated and demanding for the health system, patients and their families compared to those patients living with a single chronic condition.16,17 Furthermore, the rapid emergence of infections such as COVID-19 are fueling the complexity and posing a huge burden to the health system and worsening outcomes of patients with preexisting chronic diseases and multimorbidity.18,19

The impact of multimorbidity might even further increase in LMICs where health systems are overwhelmed by the burden of communicable diseases (such as HIV, TB and Malaria) and maternal, neonatal and nutritional health problems.2 On the other hand, health systems in LMICs are largely configured with conventional one-size fits all chronic disease care, rather than designing a model of care for every possible combination of chronic conditions.6 As a result, patients receive fragmented, inefficient and ineffective care, which could lead to conflicting medical advice and preventable hospitalizations and mortality.20

The development of health delivery models that adequately respond to this complex situation in LMICs requires clarity on the epidemiology within the context. However, there is paucity of evidence on the magnitude, distribution and patterns of multimorbidity. The objectives of this study were to review the available evidence on the epidemiology of multimorbidity and to identify gaps in evidence in LMICs.

Methods

Design

We followed the methods suggested by Arksey and O’Malley for conducting scoping reviews21 and adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist and reporting guideline22 (Supplemental file-4). Our detailed review protocol has been published elsewhere.23 In summary, we followed the following steps: (1) identifying the research question; (2) identifying relevant studies; (3) selecting studies; (4) charting the data; (5) collating, summarizing and reporting the results.

Data bases and search strategy

PubMed (MEDLINE), Scopus, PsycINFO and Cochrane databases were searched to identify articles. For grey literature, we searched WorldCat, Open Grey, Global Index Medicus and Latin American & Caribbean Health Sciences Literature (LILACS) databases. The search terms used for epidemiology of multimorbidity included ‘comorbidity’ OR ‘co-morbidity’ OR ‘multimorbidity’ OR ‘multiple chronic conditions’ AND ‘chronic disease’ OR ‘noncommunicable diseases’ OR ‘non-communicable diseases’ AND ‘low-and middle-income countries.’ We used the World Bank Country and Lending Groups list of LMICs for 2019–2020 (https://blogs.worldbank.org/opendata/new-country-classifications-income-level-2019-2020) and the detailed search strategy is shown in Supplemental file-1.

In addition, we reviewed the reference lists of all the included studies and identified relevant studies in the final synthesis. Search results were downloaded into an EndNote library and citation manager for easy review and removal of duplicates. To enhance accuracy and completeness of our search, we employed elements of the Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies (PRESS EBC Elements).24 There was no restriction on publication date and both published and unpublished papers were considered. Our search ended on August 5th, 2019.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

We included studies if they made any statement about the epidemiology of multimorbidity in LMICs. The search was limited to papers written in English. Exclusion criteria included studies from HICs, study protocols, commentaries, editorials and case reports. The full search strategy is shown in the supplemental file submitted with this manuscript (Supplemental file 1) and also published elsewhere.23

Study selection

A two-stage screening process was employed to select relevant studies from those identified in our search. First, two authors (FAE and BA) removed duplicates and screened titles of the studies to select articles relevant for abstract review together. In stage two, we reviewed abstracts independently to identify studies relevant for full-text review. We assessed inter-rater reliability (using Cohen’s Kappa) of screened abstracts between the two reviewers. The two investigators (FAE and BA) independently reviewed the full-text of articles to determine their eligibility based on the inclusion criteria. When there was disagreement on inclusion of a specific article for full-text review, the article was reviewed a second time by both reviewers together and a consensus decision reached.

A spread sheet was used to extract pertinent information from the included articles. The information captured from each relevant article included primary author, year of publication, country/ies of origin, aim of the study, study design, study setting, population age group, sample size, number and types of disease conditions used to define multimorbidity, data sources, method of data collection, intervention detail (if any), outcome assessed (if any), key results and overall limitation of the study. The spreadsheet is attached as a supplemental file (Supplemental file-2).

Analysis

We described studies in terms of their geographic location, methodologies employed to define and measure multimorbidity, findings and limitations. We synthesized evidence based on the following themes: (1) epidemiology of multimorbidity, (2) methodological approaches on studying epidemiology of multimorbidity and (3) knowledge gaps in the LMIC context. The breadth of current literature within the epidemiology of multimorbidity in LMICs was mapped and the methodologies underpinning multimorbidity research were summarized.

Results

Characteristics of included studies

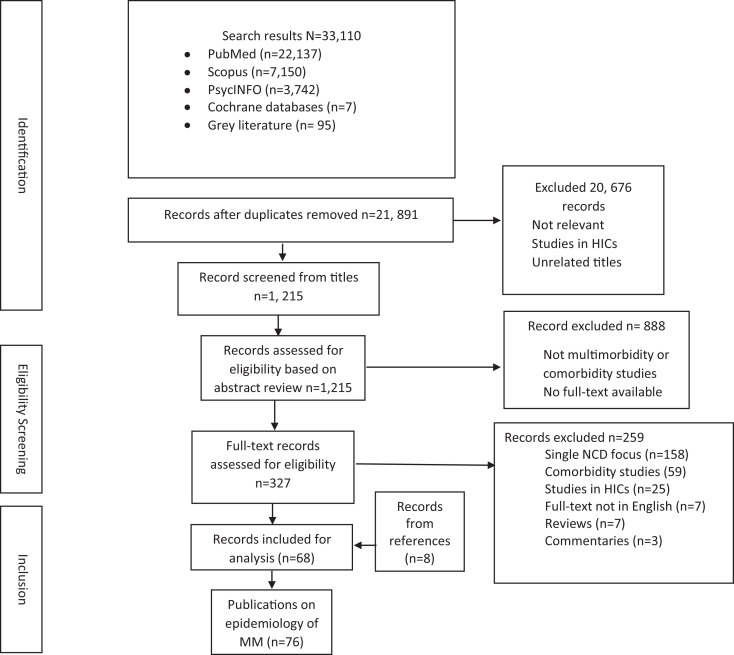

The searches yielded a total of 33,110 articles. Of these 11,240 records were duplicates and removed. Upon screening the titles, 20,676 records were further removed and 1,215 articles were retained for abstract reading. Following an abstract review by both authors independently, 327 articles (all published) were found to be eligible by both or either of the reviewers for a full-text review. The two reviewers agreed on the inclusion of 310 of the 327 articles included for the full text review (Cohen’s kappa 0.87). Having reviewed the full-texts of studies independently, we further excluded 259 articles. Two full-text articles by Chang and colleagues25,26 were re-reviewed together because reviewers did not initially agree on keeping both studies for the final inclusion. We resolved the disagreement through discussion and decided to include both articles for data charting. We reviewed the reference list of all the included 68 articles and identified eight more studies relevant for inclusion giving a total of 76 studies included for studying the epidemiology of multimorbidity. Reasons for exclusion of the remaining articles included focus on a single noncommunicable disease (NCD), comorbidity studies (studies that assessed the presence of a specific additional morbidity in people with a chronic NCD), articles written in languages other than English, and studies in HICs based on the recent classification (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) flowchart of the literature search.

Among the included publications, the first paper was published in 2010.27 Most of the studies (n = 46, 60.5%) had a primary purpose of reporting the prevalence and patterns of multimorbidity. Of the total 76 studies, 52 (68.4%) were conducted in only six middle-income countries: Brazil,27–42 China,43–54 South Africa,25,26,55–64 India,65–72 Mexico73,74 and Iran.75,76 Studies based on multicountry data (n = 11) were based on data obtained from the World Health Organization’s (WHO’s) Study on Global Ageing and Adult Health (SAGE) and World Health Surveys.77–80 Other individual studies were conducted in Indonesia,81 Serbia,82 Bangladesh,83 Malaysia,84 Vietnam,85 Argentina86 and Armenia.87 Six more individual studies were conducted in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) including Ghana,88 Nigeria,89 Burkina Faso,90 Zimbabwe,91 Ethiopia92 and Malawi93 (Supplemental file-2 and 3).

The majority (n = 66, 86.8%) of the studies were cross-sectional and the remaining 10 studies31,44,50,56,75,76,84,87,89,94 were cohorts by design. Most (n = 47, 61.8%) of the studies were population based and 22 (29%) were facility based, while the remaining seven (9%) were community based studies. The sample size of the included studies varied from 103 to 242,952 and included both males and females (Supplemental file-3). The S-3 contains the description of 76 studies included for studying epidemiology of multimorbidity in LMICs.

Regarding data sources, a significant number of studies were conducted based on data primarily collected for other studies, such as the WHO’s SAGE data,25,26,55,67,68,95,96 World Health Survey data77–80,97 or national health survey data31,35,49,52,54,56,57,62,70,82,83,98 or other types of data such as electronic medical records.50,58,59,73,75,76,82 Four pairs of studies used common data to answer different objectives: Chang et al.25,26, Pati et al.69,72, Alimohammadian et al.75,76 and Stubbs et al.78,79 Only 29 (38%) studies used data primarily collected for multimorbidity studies (Table 1).

Table 1.

Age group, number of conditions considered and data sources used to define and measure multimorbidity in LMICs.

| Age group in years | Authors | Number of conditions considered | Authors | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All ages | 47,58 | 3–6 | 28,33,43,55,56,58–62,68,77,85,93 | Data sources used | Authors |

| ≥13 | 64 | 8–12 | 25–27,30–32,36,38,41,44,57,63,67, 71,73–76,78–80,83,86,91,95–99 | Data primary collected for multimorbidity studies | 28,30,32–34,36–40,42,43,45,47, 48,51,59–61,63,65,66,71,72,74, 90,92,93,100 |

| ≥15 | 34,54,56,62 | 13–20 | 29,35,37,40,42,45,48,49,51–53,64–66,72,81,82,84,86,88,90,94 | ||

Survey data from electronic records

|

77–80,97 |

||||

| ≥18 | 27,30,31,33,37,39,41, 43,53,60,61,63, 65–69,71,72,77–80, 86,88,91–93,96–100 | 21–40 | 34,39,46,47,50,54,89,92,100 |

|

25,26,55,67,68,95,96,99 |

| 18–64 | 42 |

|

27,29,35,41,44,46,49,52,53,56, 57,62,70,75,76,81–84,86,94,98 | ||

| ≥20 | 38,44,82 | Medical records | 31,50,58,60,64,73,88,89,91 | ||

| 24–69 | 35 | ||||

| ≥40 | 25,26,55,59,81,87 | ||||

| 40–75 | 75,76 | ||||

| ≥45 | 49,50 | ||||

| ≥50 | 95 | ||||

| ≥60 | 28,29,32,40,46,48,51, 52,57,70,73,74,83–85,90 | ||||

| 60–79 | 36 | ||||

| ≥65 | 89,94 | ||||

| ≥80 | 45 |

Definition and measurement of multimorbidity

While most studies (n = 56, 73.7%) defined multimorbidity as the presence of two or more chronic conditions, some studies30,34,38–40,50,57,101 used the presence of three or more chronic conditions as their definition. All studies used simple counting of the number of chronic conditions from a list of individual diseases with the list varying substantially from one study to another. Researchers listed a minimum of three33,93 and a maximum of 4050 chronic conditions to determine presence of multimorbidity. The largest proportion of the studies (n = 28, 39%) used from 8–12 chronic conditions to determine multimorbidity (Table-1). However, no study used weighted multimorbidity indices such as the Charlson index which is useful in predicting outcomes that have immediate importance to patients, including disease severity and mortality102 (Supplemental file-3).

Studies used different approaches to diagnose chronic conditions in their study participants. Self-report was the main method (n = 33, 43.4%), followed by a combination of self-report and physical or mental assessment (n = 25, 32.9%), review of medical or electronic records31,46,50,58,60,64,73,85,89,91 and direct physical assessment alone63,85,90,99 (Supplemental file-3).

Among diseases and conditions considered for the definition of multimorbidity, Diabetes mellitus (DM) was the most frequently listed condition (in 68 studies, 94.4%). Hypertension was listed in 60 (83.3%) studies, followed by COPD (40 studies), arthritis (39 studies), heart diseases and stroke (38 studies each), cancer and depression (33 studies each), asthma (30 studies) and angina (27 studies) (Table 2). The full list of conditions considered is indicated in Supplemental file-2.

Table 2.

The top 25 list of conditions considered for measuring multimorbidity in LMICs.

| Disease type/condition | Number of studies listing the condition (n = 72) | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Diabetes mellitus | 68 | 94.4 |

| Hypertension | 60 | 83.3 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) | 40 | 55.6 |

| Arthritis | 39 | 54.2 |

| Heart diseases (heart failure and myocardial infarction) | 38 | 52.8 |

| Stroke | 38 | 52.8 |

| Cancer | 33 | 45.8 |

| Depression | 33 | 45.8 |

| Asthma | 30 | 41.7 |

| Angina | 27 | 37.5 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 22 | 30.6 |

| High cholesterol/dyslipidemia | 20 | 27.8 |

| Chronic liver disease | 18 | 25.0 |

| Visual impairment | 18 | 25.0 |

| TB | 17 | 23.6 |

| Hearing problem | 12 | 16.7 |

| Osteoporosis | 8 | 11.1 |

| HIV | 8 | 11.1 |

| Rheumatism | 7 | 9.7 |

| Anemia | 5 | 6.9 |

| Chronic back pain | 5 | 6.9 |

| Obesity | 5 | 6.9 |

| Endotulism | 5 | 6.9 |

| Psychosis | 4 | 5.6 |

| Anxiety | 2 | 2.8 |

Patterns of multimorbidity

The leading four domains of multimorbidity identified were cardio-metabolic (hypertension, heart attack, angina, heart failure, stroke, diabetes, hyperlipidemia and obesity), respiratory (asthma and COPD), mental (depression, anxiety) and musculoskeletal (arthritis, rheumatism and osteoporosis) (Supplemental file-2). Regarding the patterns of disease combinations (clusters of conditions), the most prevalent conditions were co-occurring with each other (dyads). For example, hypertension was mostly clustered with diabetes, heart disease, COPD, depression, arthritis, stroke or hypercholesterolemia.37–40,52,53,59,81,93,99,100 Similarly, diabetes was commonly clustered with hypertension, angina, obesity, depression, COPD, asthma or arthritis.37–40,52,53,56,59,81,93,99,100 A combination of three or more of these and other conditions were also reported.26,30,31,37,38,49,60,63,71

Prevalence of multimorbidity

The prevalence of multimorbidity ranged from 3.2% (93) to 90.5%.52 The prevalence rates varied depending on population age and the number of conditions considered. For example, the study by Price and colleagues in Malawi93 enrolled participants from the general population and only considered three disease conditions, whereas, the study by Wang and colleagues in China52 was conducted among elderly (≥60 years) and included a list of 16 different disease conditions. Prevalence of multimorbidity seemed to have a pattern of increasing prevalence with increasing age. It ranged from 3.2% (93) to 67.8%37 among adults aged 18 or older, 19.4%76 to 80%59 among people aged 40 and older, and 27.3%74 to 90.5% in participants aged 60 and older.52 The prevalence in the general population was also found to be higher in females (25%–52.2%) (54, 75) than males (13.4%–38.6%).75,85

Correlates of multimorbidity

All studies that analyzed correlates of multimorbidity (n = 43, 56.6%) identified advanced age to be strongly associated with multimorbidity. Forty-one (95.3%) of these 43 studies found female sex to be a risk factor for multimorbidity. In a few studies,63,100 however, males were found to be more affected than females. Similarly, the association between socioeconomic status and multimorbidity was not consistent. For example, while being wealthy was a risk factor in some studies,25,39,62,66,68,70,72,81,92,93 being poor was a risk factor in others.34,38,40,49,53,54,78 In a few studies, higher levels of education were associated with increased risk of multimorbidity.39,63,72

Discussion

This scoping review summarizes the evidence on the epidemiology of multimorbidity in LMICs. We also described knowledge gaps in the epidemiology and measurement of multimorbidity, as well as areas of focus for future research, policy and practice in LMICs.

Evidence on the epidemiology of multimorbidity in LMICs is limited although the region bears 80% of the global burden of NCDs.103 This finding is consistent with a recent review by Xu and colleagues (3) that reported only 5% of multimorbidity research studies originated in LMICs. The imbalance in the research output was also characterized by the wide interval in year of publication of the first paper on multimorbidity between HICs in 1976104 and LMICs in 2010.27

Moreover, not only were LMICs less represented in multimorbidity research, but also most of (n = 52, 68.4%) the available studies in LMICs were confined to only six middle-income countries (Brazil, China, South Africa, India, Mexico and Iran). This skewed distribution of multimorbidity studies demonstrates that there is a lack of focus on studying the phenomenon in other LMICs where it is likely to be more prevalent.26

Marked variation exists among studies with respect to the methodologies employed to define and measure multimorbidity. Studies were heterogeneous in terms of age of the participants involved, the type and number of chronic conditions considered and sources of data used to define multimorbidity. Use of different methodologies resulted in differences in the prevalence estimates and difficulty in comparing and pooling the results. The two most important factors playing a role in varying prevalence estimates in this review were age of the population enrolled and the number of conditions considered for defining multimorbidity. Consistent with studies in HICs,4,105 a constant increase in multimorbidity prevalence was observed in studies which involved participants aged 60 years or more26,38,39,46,49,74,84 and among studies including 12 or more conditions on their list.38,39,72 Evidence in HICs has shown that a list of 12–20 conditions is an appropriate threshold to estimate multimorbidity prevalence in a stable way.5 The majority of studies (n = 51, 70.9%) included in this review used 8–20 health conditions to define multimorbidity.

The debate on the types of chronic conditions to consider and whether risk factors, such hypercholesteremia, high blood pressure and obesity, and symptoms such as pain and anemia, should be included in the list for identifying multimorbidity has not been settled globally.5 The type and list of conditions considered in this review were not consistent across the studies reviewed either. However, recent recommendations have highlighted the inclusion of chronic conditions posing a significant burden to the given population. Inclusion of chronic infections such as HIV in the list to define multimorbidity has also been emphasized.106,107

As shown above, the prevalence in LMICs varies from 3.2% to 90.5% which is comparable to the findings from HICs (3.5%–100%).11 In the face of a struggle against communicable, maternal, neonatal and nutritional health problems, the emergence of multimorbidity in low and middle income countries portends a rise in a quadruple burden of disease for the health care systems.108–110

Consistent with other studies,11,111 the most prevalent conditions identified across the studies reviewed include diabetes, hypertension, COPD, arthritis, heart disease, stroke, cancer and depression. Most of these diseases shaped the patterns of multimorbidity. The nature of the clusters of conditions were mostly concordant; that is, diseases having common risk factors or that follow common pathological pathways co-existed. For example, hypertension was clustered with other cardiometabolic conditions such as diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, heart diseases and stroke. Similarly, diabetes was commonly clustered with hypertension, angina, obesity and heart diseases. Clusters are important predictors of several health and functional outcomes and understanding their nature is helpful for prevention and management of multimorbidity.112

It is globally known that additional life-years constitute an additional opportunity for acquiring other chronic conditions.4 Studies show that with increasing age, numerous underlying physiological changes occur. These include gradual accumulation of a wide variety of molecular and cellular damage that leads to a risk of chronic diseases with an increased chance of experiencing more than one chronic condition at the same time.113 However, the rise in the prevalence of multimorbidity starts around the age of 40,6 and the absolute number of individuals with multimorbidity is often higher in those under 65 years with a flattening of the odds of multimorbidity after 70 years of age.7

Most studies in our review have shown that there was higher prevalence of multimorbidity among females than males. The higher likelihood of multimorbidity in women is congruent with findings in HICs.114 This may due to the fact that females have a longer chance of survival,115 have higher consultation rates leading to higher rates of diagnosis116 or there is a difference in the prevalence of the underlying conditions included in multimorbidity definitions.4

The effect of socioeconomic status on multimorbidity was inconclusive in our review. While studies in India,72 South Africa26,63 and Malawi93 reported that multimorbidity is higher among wealthy individuals, studies in Iran,75,76 China49 and Brazil38 reported multimorbidity to be higher among people living with low socioeconomic status (SES). Low health care-seeking behavior and probability of underdiagnoses might have contributed to hide the real picture of multimorbidity in the rapidly emerging and urbanizing population of India and African countries.72 However, in HIC studies, multimorbidity is more common and occurring at an earlier age in areas of high socioeconomic deprivation than their wealthier counterparts.7,117,118

Multimorbidity impacts both patients and the health care systems in many ways.6,7,119,120 The effect on individuals include death at younger age,121–123 impairments of physical and social functioning,7,124 poor quality of life,125–127 mental health problems,7,78 high cost of care128 and higher rates of adverse effects of treatment and complex interventions.129 In LMICs, however, there is a limited body of evidence on the impacts of multimorbidity on patient-centered outcomes, such as health related quality of life (HRQoL) and functionality.6,130

The evidence base on the most effective ways to treat patients living with several medical conditions is sparse in LMICs.106 Therefore, it is likely that patients with multimorbidity face accumulating and overwhelming complexity resulting from the sum of uncoordinated responses to each of their problems.131–133 Adding to this, the current emergence of COVID-19 is demanding a change in the way patients with chronic conditions and multimorbidity are managed and followed.18,19 Furthermore, the risk of dying due to COVID-19 is high among people living with chronic conditions and multimorbidity.134

Implication for research, policy and practice

The knowledge base on the epidemiology of multimorbidity is not yet substantial and not evenly distributed among LMICs. The current literature is highly heterogeneous in methodology and has a range of limitations. Most studies were cross-sectional surveys and were based on data obtained primarily collected for other studies.135 Longitudinal studies are required to better estimate the risk, understand the onset of multimorbidity and explain the causative pathways.136 Estimating multimorbidity among patients visiting primary health care services is also possible.5 However, the epidemiological denominator in the health care setting may not necessarily represent the underlining characteristics of the general population.137 Although providing a precise list of conditions suitable for the LMICs context is beyond the scope of this review, considering a list of 8 to 12 chronic conditions that are highly prevalent and burdensome to the given society would help comparing and pooling prevalence estimates.

Employing standardized tools and a blend of methods including self-report, direct physical assessment, and complementing these data sources with medical records and prescription data, can help to capture the real picture of existing conditions.138 Integrating biomarker data into other measures of multiple chronic condition may have also notable advantages particularly for individuals with undiagnosed conditions.130 A simple count of chronic conditions is not sufficient,4,5,139 but employing validated weighted scales would help understand the overall burden and patterns of clustering of chronic conditions.5 Moreover, determining HRQoL, functionality and lived experiences of people with multiple chronic conditions is instrumental to design effective interventions in LMICs.106,140

It is imperative to define the best possible model of health care for people with multimorbidity in LMICs.107 Multimorbidity should drive a shift in the way health policies are developed and guide the health care system in tackling this challenge.20,141 In this sense, it is clear that priority should be directed to reorient and strengthen the primary care services.142 The provision of patient-centered care in which all health care providers work together with patients to ensure coordination, consistency and continuity of care over time is essential.143,144 The development of clinical practice guidelines should fuel a reform in the academic curriculum and continuing training programs to accommodate the new scenario in health professions’ education.

Strengths and limitations of this review

This is the first scoping review conducted in LMICs and provides a comprehensive insight into the nature and distribution of multimorbidity studies in LMICs. We have clearly identified the existing knowledge gap in terms of the epidemiology and management approaches of multimorbidity in LMICs. However, only including publications written in English may represent a segment of the research conducted in LMICs. Nevertheless, a particular effort was made to employ a comprehensive search strategy and navigate through a wide set of databases and identify all relevant studies in LMICs.

Conclusion and recommendations

Studies on the epidemiology of multimorbidity in LMICs are limited, while published studies are concentrated in only a few countries. The lag in studying multimorbidity in LMICs may have also contributed to the delay in designing effective interventions for those living with multimorbidity. Further research is urgently required to better understand the epidemiology of multimorbidity in LMICs. Furthermore, understanding models of multimorbidity care is an important next step in research in the context of growing prevalence of multimorbidity and its complex relationship with chronic infectious diseases, and the fact that the conventional health care is inadequate to meet the needs of patients with multiple chronic conditions warrants urgent research interventions.

Supplemental material

Supplemental Material, Search_terms_and_databases_searched_(Supplementary_file-1),_Epidemiology_of_MM_in_LMICs for Multimorbidity of chronic non-communicable diseases in low- and middle-income countries: A scoping review by Fantu Abebe, Marguerite Schneider, Biksegn Asrat and Fentie Ambaw in Journal of Comorbidity

Supplementary_file-2_(Data_extraction__Scoping_review_of_Multimorbdity_studies_in_LMICs)_rev_June14 for Multimorbidity of chronic non-communicable diseases in low- and middle-income countries: A scoping review by Fantu Abebe, Marguerite Schneider, Biksegn Asrat and Fentie Ambaw in Journal of Comorbidity

Supplementary_File_(S-3)_for_the_scoping_review_Rev_June_14 for Multimorbidity of chronic non-communicable diseases in low- and middle-income countries: A scoping review by Fantu Abebe, Marguerite Schneider, Biksegn Asrat and Fentie Ambaw in Journal of Comorbidity

Supplemental Material, Supp._file_-4_PRISMA-ScR-Fillable-Checklist-1 for Multimorbidity of chronic non-communicable diseases in low- and middle-income countries: A scoping review by Fantu Abebe, Marguerite Schneider, Biksegn Asrat and Fentie Ambaw in Journal of Comorbidity

Acknowledgement

We thank Bahir Dar University and Jhpiego-Ethiopia for the facilities we have used while conducting this study.

Abbreviations

- LMICs

Low-and middle-income countries

- HICS

High income countries

- NCDs

Non-communicable diseases

- ICD

International classification of diseases

- ICPC

International classification of primary care

- HRQoL

Health related quality of life

- COPD

Chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases

- HIV

Human immunodeficiency virus

- TB

Tuberculosis

- STI

Sexually transmitted infections

- SSA

Sub-Saharan Africa

Footnotes

Author contributions: FAE and FAG contributed in generating the concept of the review. FAE extracted the data, and carried out the analysis and drafted the manuscript. BA helped with data extraction. FAG and MS critically revised the analysis and write up contributing important intellectual content. All authors critically reviewed and approved the final manuscript for submission.

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: We have not received funding for this work. Fentie Ambaw and Biksegn Asrat receive support from AMARI (African Mental Health Research Initiative), which is funded through the DELTAS Africa initiative (DEL-15-01). The DELTAS Africa initiative is an independent funding scheme of the African Academia of Sciences (AAS)’s Alliance for accelerating excellence in Science in Africa (AESA) and supported by the New Partnership for Africa’s Development Planning and Coordinating Agency (NEPAD Agency) with funding from the Wellcome Trust (DEL-15-01) and the UK government. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily those of the AAS, NEPAD Agency, Wellcome Trust or the UK government.

ORCID iD: Fantu Abebe  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4440-028X

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4440-028X

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Aiden H. Multimorbidity. Understanding the challenge. A report for the Richmond Group of Charities. Report, January 2018.

- 2. WHO. Multimorbidity: technical series on safer primary care. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Xu X, Mishra GD, Jones M. Mapping the global research landscape and knowledge gaps on multimorbidity: a bibliometric study. J Global Health 2017; 7(1): 010414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Violan C, Foguet-Boreu Q, Flores-Mateo G, et al. Prevalence, determinants and patterns of multimorbidity in primary care: a systematic review of observational studies. PLoS One 2014; 9(7): e102149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fortin M, Stewart M, Poitras M-E, et al. A systematic review of prevalence studies on multimorbidity: toward a more uniform methodology. Ann Fam Med 2012; 10: 142–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mercer S, Salisbury C, Fortin M. ABC of multimorbidity. 1st ed Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Barnett K, Mercer SW, Norbury M, et al. Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: a cross-sectional study. Lancet 2012; 380(9836): 37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Alimohammadian M, Majidi A, Yaseri M, et al. Multimorbidity as an important issue among women: results of a gender difference investigation in a large population-based cross-sectional study in West Asia. BMJ Open 2017; 7(5): e013548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Xu X, Mishra GD, Jones M. Evidence on multimorbidity from definition to intervention: an overview of systematic reviews. Ageing Res Rev 2017; 37: 53–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Xu X, Mishra GD, Dobson AJ, et al. Progression of diabetes, heart disease, and stroke multimorbidity in middle-aged women: a 20-year cohort study. PLoS Med 2018; 15(3): e1002516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Xu X, Mishra GD, Jones M. Evidence on multimorbidity from definition to intervention: an overview of systematic reviews. Ageing Res Rev 2017; 37: 53–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mounce LTA, Campbell JL, Henley WE, et al. Predicting incident multimorbidity. Ann Family Med 2018; 16(4): 322–329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. France EF, Wyke S, Gunn JM, et al. Multimorbidity in primary care: a systematic review of prospective cohort studies. Br J Gen Pract 2012; 62(597): e297–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Akker MVD, Buntinx F, Metsemakers JFM, et al. Multimorbidity in general practice: prevalence, incidence, and determinants of co-occurring chronic and recurrent diseases. J Clin Epidemiol 1998; 51(5): 367–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Doessing A, Burau V. Care coordination of multimorbidity: a scoping study. J Comorbid 2015; 5: 15–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Charities TRGo. Just one thing after another’ Living with multiple conditions: A report from the Taskforce on Multiple Conditions. Report, October 2018.

- 17. Boyd CM, Fortin M. Future of multimorbidity research: How should understanding of multimorbidity inform health system design? Public Health Rev 2010; 32(2): 451–474. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ailabouni NJ, Hilmer SN, Kalisch L, et al. COVID-19 pandemic: considerations for safe medication use in older adults with multimorbidity and polypharmacy. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2020; 16(12): 2181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Guan W-J, Liang W-H, Zhao Y, et al. Comorbidity and its impact on 1590 patients with Covid-19 in China: a nationwide analysis. Eur Respir J 2020; 55(5): 2000547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Heide IVD, Snoeijs S, Melchiorre MG, et al. Innovating care for people with multiple chronic conditions in Europe. Technical Report, 2015.

- 21. Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2005; 8(1): 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tricco AC, Erin Lillie M, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018; 169(7): 467–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Eyowas FA, Schneider M, Yirdaw BA, et al. Multimorbidity of chronic noncommunicable diseases and its models of care in low- and middle-income countries: a scoping review protocol. BMJ Open 2019; 9: e033320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. CADTH. PRESS—Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies: 2015 Guideline Explanation and Elaboration (PRESS E&E). 2016. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25. Chang AY, Gomez-Olive FX, Manne-Goehler J, et al. Multimorbidity and care for hypertension, diabetes and HIV among older adults in rural South Africa. Bull World Health Organ 2019; 97(1): 10–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chang AY, Gómez-Olivé FX, Payne C, et al. Chronic multimorbidity among older adults in rural South Africa. BMJ Global Health 2019; 4(4): e001386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Andrade LH, Benseñor IM, Viana MC, et al. Clustering of psychiatric and somatic illnesses in the general population: multimorbidity and socioeconomic correlates. Braz J Med Biol Res 2010; 43(5): 483–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Alves EVDC, Flesch LD, Cachioni M, et al. The double vulnerability of elderly caregivers: multimorbidity and perceived burden and their associations with frailty. Rev Bras Geriatr Gerontol 2018; 21(3): 301–311. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Amaral TLM, Amaral CDA, Lima NSD, et al. Multimorbidade, depressão e qualidade de vida em idosos atendidos pela Estratégia de Saúde da Família em Senador Guiomard, Acre, Brasil. Ciênc Saúde Coletiva 2018; 23(9): 3077–3084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Araujo MEA, Silva MT, Galvao TF, et al. Prevalence and patterns of multimorbidity in Amazon region of Brazil and associated determinants: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2018; 8(11): e023398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Castilho JL, Escuder MM, Veloso V, et al. Trends and predictors of non-communicable disease multimorbidity among adults living with HIV and receiving antiretroviral therapy in Brazil. J Int AIDS Soc 2019; 22: e25233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cavalcanti G, Doring M, Portella MR, et al. Multimorbidity associated with polypharmacy and negative self-perception of health. Rev Bras Geriatr Gerontol (Online) 2017; 20(5): 634–642. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Christofoletti M, Streb AR, Duca GFD. Body mass index as a predictor of multimorbidity in the Brazilian population. Rev Bras Cineantropom Desempenho Hum 2018; 20(6): 555–565. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Costa CDS, Flores TR, Wendt A, et al. Inequalities in multimorbidity among elderly: a population-based study in a city in Southern Brazil. Cadernos De Saude Publica 2018; 34(11): e00040718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Jantsch AG, Alves RFS, Faerstein E. Educational inequality in Rio de Janeiro and its impact on multimorbidity: evidence from the Pró-Saúde study. A cross-sectional analysis. Säo Paulo Med J 2018; 136(1): 51–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Leal Neto JDS, Barbosa AR, Meneghini V. Diseases and chronic health conditions, multimorbidity and body mass index in older adults. Rev Bras Cineantropom Desempenho Hum 2016; 18(5): 509–519. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nunes BP, Batista SRR, Andrade FBD, et al. Multimorbidity: the Brazilian longitudinal study of aging (ELSI-Brazil). Rev Saude Publica 2018; 52(2): 10s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Nunes BP, Camargo-Figuera FA, Guttier M, et al. Multimorbidity in adults from a Southern Brazilian city: occurrence and patterns. Int J Pub Health 2016; 61(9): 1013–1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Nunes BP, Chiavegatto Filho ADP, Pati S, et al. Contextual and individual inequalities of multimorbidity in Brazilian adults: a cross-sectional national-based study. BMJ Open 2017; 7(6): e015885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Nunes BP, Thume E, Facchini LA. Multimorbidity in older adults: magnitude and challenges for the Brazilian health system. BMC Public Health 2015; 15: 1172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Rzewuska M, de Azevedo-Marques JM, Coxon D, et al. Epidemiology of multimorbidity within the Brazilian adult general population: evidence from the 2013 National Health Survey (PNS 2013). PLoS One 2017; 12(2): e0171813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wang YP, Nunes BP, Coelho BM, et al. Multilevel analysis of the patterns of physical-mental multimorbidity in general population of Sao Paulo Metropolitan Area, Brazil. Sci Rep 2019; 9(1): 2390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wong MC, Liu J, Zhou S, et al. The association between multimorbidity and poor adherence with cardiovascular medications. Int J Cardiol 2014; 177(2): 477–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ruel G, Shi Z, Zhen S, et al. Association between nutrition and the evolution of multimorbidity: the importance of fruits and vegetables and whole grain products. Clin Nutrit (Edinburgh, Scotland) 2014; 33(3): 513–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Su P, Ding H, Zhang W, et al. The association of multimorbidity and disability in a community-based sample of elderly aged 80 or older in Shanghai, China. BMC Geriatr 2016; 16(1): 178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Chen H, Chen Y, Cui B. The association of multimorbidity with healthcare expenditure among the elderly patients in Beijing, China. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2018; 79: 32–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Wang HH, Wang JJ, Wong SY, et al. Epidemiology of multimorbidity in China and implications for the healthcare system: cross-sectional survey among 162,464 community household residents in Southern China. BMC Med 2014; 12: 188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wang XX, Chen ZB, Chen XJ, et al. Functional status and annual hospitalization in multimorbid and non-multimorbid older adults: a cross-sectional study in Southern China. Health Quality Life Outcomes 2018; 16(1): 33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Chen H, Cheng M, Zhuang Y, et al. Multimorbidity among middle-aged and older persons in urban China: prevalence, characteristics and health service utilization. Geriatr Geront Int 2018; 18(10): 1447–1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lai FTT, Wong SYS, Yip BHK, et al. Multimorbidity in middle age predicts more subsequent hospital admissions than in older age: a nine-year retrospective cohort study of 121,188 discharged in-patients. Eur J Int Med 2019; 61: 103–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Gu J, Chao J, Chen W, et al. Multimorbidity in the community-dwelling elderly in urban China. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2017; 68: 62–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Wang R, Yan Z, Liang Y, et al. Prevalence and patterns of chronic disease pairs and multimorbidity among older Chinese adults living in a rural area. PLoS One 2015; 10(9): e0138521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Wang SB, D’Arcy C, Yu YQ, et al. Prevalence and patterns of multimorbidity in Northeastern China: a cross-sectional study. Public Health 2015; 129(11): 1539–1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Chung RY, Mercer S, Lai FT, et al. Socioeconomic determinants of multimorbidity: a population-based household survey of Hong Kong Chinese. PLoS One 2015; 10(10): e0140040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Gaziano TA, Abrahams-Gessel S, Gomez-Olive FX, et al. Cardiometabolic risk in a population of older adults with multiple co-morbidities in rural South Africa: the HAALSI (Health and Aging in Africa: longitudinal studies of INDEPTH communities) study. BMC Public Health 2017; 17: 206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Weimann A, Dai D, Oni T. A cross-sectional and spatial analysis of the prevalence of multimorbidity and its association with socioeconomic disadvantage in South Africa: a comparison between 2008 and 2012. Soc Sci Med (1982) 2016; 163: 144–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Ataguba JE-O. Inequalities in multimorbidity in South Africa. Int J Equity Health 2013; 12: 64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Lalkhen H, Mash R. Multimorbidity in non-communicable diseases in South African primary healthcare. SAMJ, S Afr Med J 2015; 105(2): 134–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Folb N, Timmerman V, Levitt NS, et al. Multimorbidity, control and treatment of noncommunicable diseases among primary healthcare attenders in the Western Cape, South Africa. S Afr Med J 2015; 105(8): 642–647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Oni T, Youngblood E, Boulle A, et al. Patterns of HIV, TB, and non-communicable disease multi-morbidity in peri-urban South Africa—a cross sectional study. BMC Infect Dis 2015; 15: 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Petersen I, Rathod S, Kathree T, et al. Risk correlates for physical-mental multimorbidities in South Africa: a cross-sectional study. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci 2019; 28: 418–426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Alaba O, Chola L. The social determinants of multimorbidity in South Africa. Int J Equity Health 2013; 12: 63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Peltzer K. Tuberculosis non-communicable disease comorbidity and multimorbidity in public primary care patients in South Africa. Afr J Prim Health Care Family Med 2018; 10(1): e1–e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Roche S, de Vries E. Multimorbidity in a large district hospital: a descriptive cross-sectional study. SAMJ S Afr Med J 2017; 107(12): 1110–1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Pati S, Hussain MA, Swain S, et al. Development and validation of a questionnaire to assess multimorbidity in primary care: an Indian experience. London: Hindawi Publishing Corporation, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Pati S, Swain S, Knottnerus JA, et al. Health related quality of life in multimorbidity: a primary-care based study from Odisha, India. Health Qual Life Outcome 2019; 17: 116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Agrawal G, Patel SK, Agarwal AK. Lifestyle health risk factors and multiple non-communicable diseases among the adult population in India: a cross-sectional study. J Public Health (Germany) 2016; 24(4): 317–324. [Google Scholar]

- 68. Pati S, Agrawal S, Swain S, et al. Non communicable disease multimorbidity and associated health care utilization and expenditures in India: cross-sectional study. BMC Health Ser Res 2014; 14(1): 451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Pati S, Swain S, Metsemakers J, et al. Pattern and severity of multimorbidity among patients attending primary care settings in Odisha, India. PLoS One 2017; 12(9): e0183966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Mini GK, Thankappan KR. Pattern, correlates and implications of non-communicable disease multimorbidity among older adults in selected Indian states: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2017; 7(3): e013529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Pati S, Bhattacharya S, Swain S. Prevalence and patterns of multimorbidity among human immunodeficiency virus positive people in Odisha, India: an exploratory study. J Clin Diagn Res 2017; 11(6): Lc10–lc3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Pati S, Swain S, Hussain MA, et al. Prevalence, correlates, and outcomes of multimorbidity among patients attending primary care in Odisha, India. Ann Family Med 2015; 13(5): 446–450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Mino-León D, Reyes-Morales H, Doubova SV, et al. Multimorbidity patterns in older adults: an approach to the complex interrelationships among chronic diseases. Arch Med Res 2017; 48(1): 121–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Islas-Granillo H, Medina-Solís CE, Márquez-Corona ML, et al. Prevalence of multimorbidity in subjects aged ≥60 years in a developing country. Clin Interven Aging 2018; 13: 1129–1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Alimohammadian M, Majidi A, Yaseri M, et al. Multimorbidity as an important issue among women: results of a gender difference investigation in a large population-based cross-sectional study in West Asia. BMJ Open 2017; 7(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Ahmadi B, Alimohammadian M, Yaseri M, et al. Multimorbidity: epidemiology and risk factors in the Golestan cohort study, Iran: a cross-sectional analysis. Medicine (United States) 2016; 95(7): e2756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Afshar S, Roderick PJ, Kowal P, et al. Global patterns of multimorbidity: a comparison of 28 countries using the world health surveys. Appl Demograp Series 2016; 8: 381–402. [Google Scholar]

- 78. Stubbs B, Koyanagi A, Veronese N, et al. Physical multimorbidity and psychosis: comprehensive cross sectional analysis including 242,952 people across 48 low- and middle-income countries. BMC Med 2016; 14(1): 189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Stubbs B, Vancampfort D, Veronese N, et al. Depression and physical health multimorbidity: primary data and country-wide meta-analysis of population data from 190 593 people across 43 low- and middle-income countries. Psychol Med 2017; 47(12): 2107–2117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Vancampfort D, Koyanagi A, Ward PB, et al. Chronic physical conditions, multimorbidity and physical activity across 46 low- and middle-income countries. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2017; 14(1): 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Hussain MA, Huxley RR, Mamun AA. Multimorbidity prevalence and pattern in Indonesian adults: an exploratory study using national survey data. BMJ Open 2015; 5: e009810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Jankovic J, Mirkovic M, Jovic-Vranes A, et al. Association between non-communicable disease multimorbidity and health care utilization in a middle-income country: population-based study. Public Health 2018; 155: 35–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Khanam MA, Streatfield PK, Kabir ZN, et al. Prevalence and patterns of multimorbidity among elderly people in rural Bangladesh: a cross-sectional study. J Health Popul Nutr 2011; 29(4): 406–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Hussin NM, Shahar S, Din NC, et al. Incidence and predictors of multimorbidity among a multiethnic population in Malaysia: a community-based longitudinal study. Aging Clin Exp Res 2019; 31(2): 215–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Ha NT, Le NH, Khanal V, et al. Multimorbidity and its social determinants among older people in southern provinces, Vietnam. Int J Equity Health 2015; 14(1): 50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Olivares DEV, Chambi FRV, Chañi EMM, et al. Risk factors for chronic diseases and multimorbidity in a primary care context of Central Argentina: a web-based interactive and cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2017; 14(3): 251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Demirchyan A, Khachadourian V, Armenian HK, et al. Short and long term determinants of incident multimorbidity in a cohort of 1988 earthquake survivors in Armenia. Int J Equity Health 2013; 12(1): 68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Nimako BA, Baiden F, Sackey SO, et al. Multimorbidity of chronic diseases among adult patients presenting to an inner-city clinic in Ghana. Global Health 2013; 9: 61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Nwani PO, Isah AO. Chronic diseases and multimorbidity among elderly patients admitted in the medical wards of a Nigerian tertiary hospital. J Clin Gerontol Geriatr 2016; 7(3): 83–86. [Google Scholar]

- 90. Hien H, Berthé A, Drabo MK, et al. Prevalence and patterns of multimorbidity among the elderly in Burkina Faso: cross-sectional study. Trop Med Int Health 2014; 19(11): 1328–1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Magodoro IM, Esterhuizen TM, Chivese T. A cross-sectional, facility based study of comorbid non-communicable diseases among adults living with HIV infection in Zimbabwe. BMC Res Notes 2016; 9: 379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Woldesemayat EM, Kassa A, Gari T, et al. Chronic diseases multi-morbidity among adult patients at Hawassa University Comprehensive Specialized Hospital. BMC Public Health 2018; 18(1): 352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Price AJ, Crampin AC, Amberbir A, et al. Prevalence of obesity, hypertension, and diabetes, and cascade of care in sub-Saharan Africa: a cross-sectional, population-based study in rural and urban Malawi. Lancet Diabet Endocrinol 2018; 6(3): 208–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Bao J, Chua K-C, Prina M, et al. Multimorbidity and care dependence in older adults: a longitudinal analysis of findings from the 10/66 study. MC Public Health 2019; 19: 585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Koyanagi A, Lara E, Stubbs B, et al. Chronic physical conditions, multimorbidity, and mild cognitive impairment in low- and middle-income countries. J Am Geriatr Soc 2018; 66: 721–727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Agrawal S, Agrawal PK. Association between body mass index and prevalence of multimorbidity in low-and middle-income countries: a cross-sectional study. Int J Med Public Health 2016; 6(2): 73–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Vancampfort D, Smith L, Stubbs B, et al. Associations between active travel and physical multi-morbidity in six low- and middle-income countries among community dwelling older adults: a cross-sectional study. PLoS One 2018; 13(8): e0203277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Macinko J, Andrade FCD, Nunes BP, et al. Primary care and multimorbidity in six Latin American and Caribbean countries. Rev Panam Salud Pública 2019; 43: e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Arokiasamy P, Uttamacharya U, Jain K, et al. The impact of multimorbidity on adult physical and mental health in low- and middle-income countries: What does the study on global ageing and adult health (SAGE) reveal? BMC Med 2015; 13: 178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Pengpid S, Peltzer K. Multimorbidity in chronic conditions: public primary care patients in four greater Mekong countries. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2017; 14(9): 1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Nunes BP, Flores TR, Mielke GI, et al. Multimorbidity and mortality in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2016; 67: 130–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Charlson ME, Pompei P, Lales K, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987; 40(5): 373–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Hunter DJ, Reddy KS. Noncommunicable diseases. N Engl J Med 2013; 369(14): 1336–1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Brandlmeier P. Multimorbidity among elderly patients in an urban general practice. ZFA Zeitschrift fur Allgemeinmedizin 1976; 52(25): 1269–1275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Garin N, Koyanagi A, Chatterji S, et al. Global multimorbidity patterns: a cross-sectional, population-based, multi-country study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2016; 71(2): 205–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. AMS. Advancing research to tackle multimorbidity: the UK and LMIC perspectives. Premstätten: AMS, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 107. Beran D. Difficulties facing the provision of care for multimorbidity in low-income countries. Comorbidity of mental and physical disorders. Key issues in mental health. Berlin: S. Karger AG, 2014. p. 33–41. [Google Scholar]

- 108. Foreman KJ, Marquez N, Dolgert A, et al. Forecasting life expectancy, years of life lost, and all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 250 causes of death: reference and alternative scenarios for 2016–40 for 195 countries and territories. Lancet 2018; 392(10159): 2052–2090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Agyepong IA, Sewankambo N, Binagwaho A, et al. The path to longer and healthier lives for all Africans by 2030: the Lancet Commission on the future of health in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet. 2017; 390(10114): 2803–2859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Mayosi BM, Flisher AJ, Lalloo UG, et al. The burden of non-communicable diseases in South Africa. Health in South Africa 2009; 374(9693): P934–947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Prados-Torres A, Calderon-Larranaga A, et al. Multimorbidity patterns: a systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol 2014; 67(3): 254–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Olaya B, Moneta MV, Caballero FF, et al. Latent class analysis of multimorbidity patterns and associated outcomes in Spanish older adults: a prospective cohort study. BMC Geriatrics 2017; 17(1): 186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. WHO. World report on ageing and health. Geneva: World health organization, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 114. King DE, Xiang J, Pilkerton CS. Multimorbidity trends in United States adults, 1988-2014. J Am Board Fam Med: JABFM 2018; 31(4): 503–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Prados-Torres A, Poblador-Plou B, Gimeno-Miguel A, et al. Cohort profile: the epidemiology of chronic diseases and multimorbidity. The EpiChron cohort study. Int J Epidemiol 2018; 47(2): 382–384f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Zemedikun DT, Gray LJ, Khunti K, et al. Patterns of multimorbidity in middle-aged and older adults: an analysis of the UK Biobank data. Mayo Clin Proc 2018; 93(7): 857–866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Smith SM, Soubhi H, Fortin M, et al. Managing patients with multimorbidity: systematic review of interventions in primary care and community settings. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed) 2012; 345: e5205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Mercer SW, Zhou Y, Humphris GM, et al. Multimorbidity and socioeconomic deprivation in primary care consultations. Ann Fam Med 2018; 16(2): 127–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Poitras ME, Maltais ME, Bestard-Denomme L, et al. What are the effective elements in patient-centered and multimorbidity care? A scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res 2018; 18(1): 446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Rijken M, Hujala A, van Ginneken E, et al. Managing multimorbidity: profiles of integrated care approaches targeting people with multiple chronic conditions in Europe. Health Policy (Amsterdam, Netherlands) 2018; 122(1): 44–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Olaya B, Domenech-Abella J, Moneta MV, et al. All-cause mortality and multimorbidity in older adults: the role of social support and loneliness. Exp Gerontol 2017; 99: 120–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Wei MY, Mukamal KJ. Multimorbidity, mortality, and long-term physical functioning in 3 prospective cohorts of community-dwelling adults. Am J Epidemiol 2018; 187(1): 103–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Martin-Lesende I, Recalde E, Viviane-Wunderling P, et al. Mortality in a cohort of complex patients with chronic illnesses and multimorbidity: a descriptive longitudinal study. BMC Palliat Care. 2016; 15: 42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Wijlhuizen GJ, Perenboom RJ, Garre FG, et al. Impact of multimorbidity on functioning: evaluating the ICF core set approach in an empirical study of people with rheumatic diseases. J Rehabil Med 2012; 44(8): 664–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Fortin M, Lapointe L, Hudon C, et al. Multimorbidity and quality of life in primary care: a systematic review. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2004; 2: 51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Hunger M, Thorand B, Schunk M, et al. Multimorbidity and health-related quality of life in the older population: results from the German KORA-age study. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2011; 9: 53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Jitta DJ, DeJongste MJ, Kliphuis CM, et al. Multimorbidity, the predominant predictor of quality-of-life, following successful spinal cord stimulation for angina pectoris. Neuromodulation 2011; 14(1): 13–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Picco L, Achilla E, Abdin E, et al. Economic burden of multimorbidity among older adults: impact on healthcare and societal costs. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016; 16: 173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Boyd CM, McNabney MK, Brandt N, et al. Guiding principles for the care of older adults with multimorbidity: an approach for clinicians: American Geriatrics Society Expert Panel on the Care of Older Adults with Multimorbidity. J Am Geriatr Soc 2012; 60(10): E1–E25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Bromley CM-LS. Beyond a boundary–conceptualising and measuring multiple health conditions in the Scottish population. Edinburgh: Scotland University of Edinburgh, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 131. François-Pierre G, Wilson MG, Lavis JN, et al. Citizen brief: improving care and support for people with multiple chronic health conditions in Ontario. Hamilton: McMaster Health Forum, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 132. Wilson MG, Lavis JN, Gauvin F-P. Designing integrated approaches to support people with multimorbidity: key messages from systematic reviews, health system leaders and citizens. Health Policy 2016; 12(2): e91. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Boehmer KR, Abu Dabrh AM, Gionfriddo MR, et al. Does the chronic care model meet the emerging needs of people living with multimorbidity? A systematic review and thematic synthesis. PLoS One 2018; 13(2): e0190852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Lai AG, Pasea L, Banerjee A, et al. Estimating excess mortality in people with cancer and multimorbidity in the COVID-19 emergency. 2020. doi: 10.1101/2020.05.27.20083287

- 135. Fortin M, Almirall J, Nicholson K. Development of a research tool to document self-reported chronic conditions in primary care. J Comorbid 2017; 7(1): 117–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136. AMS. Multimorbidity: a priority for global health research. Premstätten: AMS, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 137. Huntley AL, Johnson R, Purdy S, et al. Measures of multimorbidity and morbidity burden for use in primary care and community settings: a systematic review and guide. Ann Fam Med 2012; 10(2): 134–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138. Calderon-Larranaga A, Vetrano DL, Onder G, et al. Assessing and measuring chronic multimorbidity in the older population: a proposal for its operationalization. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2017; 72(10): 1417–1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139. Wallace E, McDowell R, Bennett K, et al. Comparison of count-based multimorbidity measures in predicting emergency admission and functional decline in older community-dwelling adults: a prospective cohort study. BMJ Open 2016; 6: e013089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140. Calderon-Larranaga A, Vetrano DL, Ferrucci L, et al. Multimorbidity and functional impairment: bidirectional interplay, synergistic effects and common pathways. J Int Med 2019; 285(3): 255–271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141. Hurst JR, Dickhaus J, Maulik PK, et al. Global Alliance for Chronic Disease researchers’ statement on multimorbidity. Lancet 2018; 6(12): e1270–1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142. Calderon-Larranaga A, Fratiglioni L. Multimorbidity research at the crossroads: developing the scientific evidence for clinical practice and health policy. J Int Med 2019; 285(3): 251–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143. Valderas JM, Gangannagaripalli J, Nolte E, et al. Quality of care assessment for people with multimorbidity, scoping review. 2019; 285(3): 289–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144. Fortin M, Hudon C, Bayliss EA, et al. Multimorbidity’s many challenges: time to focus on the needs of this vulnerable and growing population. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed) 2007; 334: 1016–1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Material, Search_terms_and_databases_searched_(Supplementary_file-1),_Epidemiology_of_MM_in_LMICs for Multimorbidity of chronic non-communicable diseases in low- and middle-income countries: A scoping review by Fantu Abebe, Marguerite Schneider, Biksegn Asrat and Fentie Ambaw in Journal of Comorbidity

Supplementary_file-2_(Data_extraction__Scoping_review_of_Multimorbdity_studies_in_LMICs)_rev_June14 for Multimorbidity of chronic non-communicable diseases in low- and middle-income countries: A scoping review by Fantu Abebe, Marguerite Schneider, Biksegn Asrat and Fentie Ambaw in Journal of Comorbidity

Supplementary_File_(S-3)_for_the_scoping_review_Rev_June_14 for Multimorbidity of chronic non-communicable diseases in low- and middle-income countries: A scoping review by Fantu Abebe, Marguerite Schneider, Biksegn Asrat and Fentie Ambaw in Journal of Comorbidity

Supplemental Material, Supp._file_-4_PRISMA-ScR-Fillable-Checklist-1 for Multimorbidity of chronic non-communicable diseases in low- and middle-income countries: A scoping review by Fantu Abebe, Marguerite Schneider, Biksegn Asrat and Fentie Ambaw in Journal of Comorbidity