Abstract

CD8+ memory T cells provide anamnestic host defense against intracellular pathogens and cancer immunosurveillance but are also pathogenic in some autoimmune diseases. In mouse skin, there are two unique subsets of CD8+ memory T cells, resident memory cells that reside long-term in steady state skin and recirculating memory cells that are transient. They have distinct mechanisms of recruitment, development, and maintenance in response to skin-derived signals. In this review, we will focus on these mechanisms and the functional relationship of these two types of CD8+ memory cells with host defense and disease.

INTRODUCTION

The estimated number of T cells within human skin is two billion, which is more than the total number of circulating T cells in blood (Clark et al., 2006). T cells in skin can be broadly categorized as γδ T cells and αβ T cells. αβ T cells, which include CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells, make up the vast majority (90–99%) in adult skin (Falini et al., 1989; Groh et al., 1989). Most αβ T cells found in skin are memory cells that expanded in response to previous antigenic stimulation. A relatively recently described subset of memory cells termed resident memory T cells (TRM cells) are long-term residents in both murine and human skin (Gehad et al., 2018; Watanabe et al., 2015). These cells protect against re-exposure to viruses, play an important role in cancer immunosurveillance, and instigate some autoimmune diseases. In addition to TRM cells, there are less well characterized skin-homing circulating memory T cells (sTCIRC cells) that transiently enter skin and exit via lymphatics (Hirai et al., 2019). In this review, we will overview recent findings focusing on cutaneous murine CD8+ memory T-cell development, maintenance, and their importance to health.

CD8+ T-cell migration into inflamed skin

In response to priming in the lymph node by skin-migratory dendritic cells carrying cognate antigen, antigen-specific CD8+ T cells become activated and proliferate (Kashem et al., 2017; Mempel et al., 2004). CD8+ T cells increase expression of LFA-1 (CD11a/CD18), VLA-4, and several chemokine receptors including CCR2–5 and CXCR3 (Santamaria Babi et al., 1995; Thomsen et al., 2003; Weninger et al., 2002). In inflamed skin, endothelial cells increase expression of ICAM-1 and VCAM-1, and keratinocytes and monocytes express chemokines including CCL2–5, CXCL9, and CXCL10 that are ligands for CCR2, CCR5, and CXCR3 (Hickman et al., 2015; Klunker et al., 2003; Swerlick et al., 1992). Together, these signals provide efficient entry of effector CD8+ T cells into inflamed skin (Schön et al., 2003). These mechanisms are not unique to skin homing CD8+ T cells but are likely common mechanisms for the entry of T cells into multiple inflamed tissues (Bromley et al., 2008).

CD8+ T cells expressing E- and P-selectin ligands that allow for intravascular rolling (cutaneous lymphocyte antigen is one of these ligands), CCR8, and/or CCR10 are highly enriched in skin compared with blood in both mouse and human (Homey et al., 2002; Kupper and Fuhlbrigge, 2004; McCully et al., 2015; Schaerli et al., 2004). Thus, they are thought to be an important component for the skin-homing capacity of CD8+ T cells. Mice deficient in E- and P-selectin or their ligands have reduced skin-homing CD8+ T cells in vaccinia virus–infected skin. In addition, blocking the antibody to E- and P-selectin significantly reduced CD8+ T-cell skin infiltration in mice (Hirata et al., 2002; Jiang et al., 2012). Notably, during inflammation, E- and P-selectin are expressed by endothelial cells in other tissues (Kansas, 1996); thus, E- and P-binding CD8+ T cells are not exclusively skin-homing. CCL27, a ligand for CCR10, is constitutively produced by keratinocytes and can also be induced by stimulation with tumor necrosis factor and IL-1β (Homey et al., 2000). CCR10 expression is increased early during CD8+ T-cell expansion in lymph nodes following herpes simplex virus skin infection (Zaid et al., 2017). CCR10−/− T cells can enter but are not maintained efficiently in skin (Zaid et al., 2017). Thus CCR10 is redundant for skin migration but required for epidermal residence. A murine study showed that CCR8 is selectively expressed in skin TRM cells and not found on TRM cells present in other barrier tissues (i.e., gut and lung), suggesting a skin-specific role (Mackay et al., 2013). However, there are no obvious functional consequences of its absence, as CCR8−/− T cells are efficiently recruited into the skin and maintained in mouse epidermis following herpes simplex virus skin infection (Zaid et al., 2017). Keratinocyte-derived factors are reported to induce CCR8 expression by CD8+ T cells (McCully et al., 2012); thus, CCR8 may be redundant for TRM cells for recruitment and maintenance.

TRM cell differentiation and maintenance in skin

Murine CD8+ TRM cells almost exclusively reside in the epidermis where few CD4+ T cells exist, whereas in human epidermis, both CD8+ and CD4+ T cells can be found (Bos et al., 1987; Clark et al., 2006; Foster, 1990; Gebhardt et al., 2011; Watanabe et al., 2015). TRM cells in mouse epidermis are derived from KLRG1− effector cells that are recruited into the skin in response to inflammation, and the precursors are derived from common naïve T-cell precursors of circulating central memory cells in lymph nodes (Gaide et al., 2015; Mackay et al., 2013). CXCR3 on effector T cells can promote TRM cell differentiation in response to viral infection (Hickman et al., 2015; Mackay et al., 2013). Notably, TRM cell differentiation does not require cognate antigen in the skin. Effectors recruited into the skin by epicutaneous application of the chemical sensitizer DNFB efficiently differentiate into TRM cells

(Mackay et al., 2012). If cognate antigen is present in the skin, however, antigen-specific TRM cells are able to efficiently outcompete noneantigen-specific bystander cells (Khan et al., 2016; Muschaweckh et al., 2016). This results in large numbers of antigen-specific TRM cells at sites of prior infection (Enamorado et al., 2017; Jiang et al., 2012). TRM cells, albeit at a lower density, also accumulate at skin locations that have not been subjected to experimental inflammation or infection (Enamorado et al., 2017; Jiang et al., 2012). Thus, TRM cell progenitors do have the capacity to be recruited into the skin at steady-state through mechanisms that remain to be elucidated.

The most characteristic markers of skin TRM cells in both human and mouse are CD69 and CD103, and most epidermal TRM cells coexpress these markers, although some of these cells also express CD49a or CCR6, which predict the IFN-γ or IL-17a production potential of TRM cells, respectively (Cheuk et al., 2017; Linehan et al., 2018; Mackay et al., 2013; Watanabe et al., 2015). CD8+ T cells deficient in either CD69 or CD103 cannot differentiate or be maintained as TRM cells in mice (Mackay et al., 2013). However, the dependence on CD69 and CD103 is not absolute, as TRM cells lacking these markers can be found in other tissues (Steinert et al., 2015). Effector CD8+ T cells upregulate CD69 following entry into infected or inflamed skin. T cells lacking CD69 are able to enter the epidermis shortly after viral infection but are unable to persist in the skin beyond nine days (Mackay et al., 2015a, 2013; Walsh et al., 2019). The requirement for CD69 is likely because of its function inhibiting S1PR1-mediated tissue egress (Shiow et al., 2006; Skon et al., 2013). As TRM cells mature, they begin to express the transcription factors HOBIT and BLIMP1 that are known to suppress expression of the transcription factor KLF2, resulting in a lower expression of S1PR1 (Mackay et al., 2016; Skon et al., 2013). Thus, CD69 is not just a marker but is also required for TRM cell retention in the epidermis during a developmental window, although it may not be required by fully differentiated TRM cells.

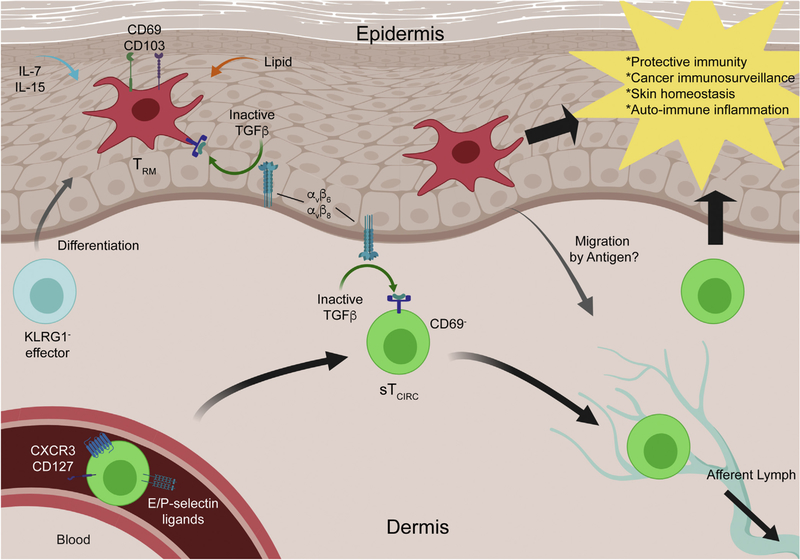

CD103 expression by TRM cells is induced upon entry into the epidermis and is dependent on the cytokine transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) (Casey et al., 2012; El-Asady et al., 2005; Mackay et al., 2013). TGF-β is synthesized in an inactive form that requires activation for bioactivity (Worthington et al., 2011). In the epidermis, TGF-β from an unknown cell type is activated by either integrin αvβ6 or αvβ8 expressed by keratinocytes (Mohammed et al., 2016; Yang et al., 2007). In mice genetically lacking both integrins in skin, CD8+ T cells enter the epidermis following skin inflammation but TRM cells fail to increase expression of CD103 and are absent at late time points. Similarly, αvβ6-blocking monoclonal antibodies partially deplete TRM cells (Mohammed et al., 2016). CD8+ T cells lacking CD103 are also able to enter the epidermis but TRM cells fail to persist long-term (Mackay et al., 2013; Zaid et al., 2017). CD103 is also known as αe integrin; it pairs with β7 and binds E-cadherin expressed by keratinocytes. Thus, it seems likely that TRM cells require TGF-β–einduced CD103 to anchor onto keratinocytes and persist within the epidermis (Zaid et al., 2017) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. CD8+ memory T cells in the murine skin.

KLRG1− effector CD8+ T cells are progenitors of CD8+ TRM cells. They are recruited to the skin by local inflammation and unknown, inflammation-independent mechanisms. CD8+ TRM cells express CD69 and CD103, and both are necessary for either development or maintenance. It is suggested that they can migrate out of the skin upon antigen re-encounter. sTCIRC cells can be identified by E- or P-selectin binding and KLRG1−CD127+ or CXCR3+CX3CR1dim-mid in the blood circulation. They are CD69− in the skin and return to circulation through afferent lymphatics. Both memory cells require keratinocyte-mediated activation of TGF-β through αvβ6 and αvβ8 integrins for persistence. TRM cells are also shown to require IL-7, IL-15, and lipid uptake for maintenance. sTCIRC cell, skin-homing circulating memory T cell; TGF-β, transforming growth factor-β; TRM cell, resident memory T cell.

The mechanisms used by TRM cells to persist in the epidermis are of particular interest, as strategies to inhibit these pathways could have clinical utility in the context of TRM cell–mediated autoimmune disease. TRM cells require the cytokines IL-7 and IL-15 that are likely produced by keratinocytes in hair follicles (Adachi et al., 2015; Mackay et al., 2013; Richmond et al., 2018). This may also be true in humans, as human CCR8+ TRM cells respond to IL-7 and IL-15 for homeostatic proliferation (McCully et al., 2018). Antibody blockade of IL-15 receptor has successfully reduced the numbers of epidermal TRM cells in mice (Richmond et al., 2018). TRM cells have also been shown to have a dependence on fatty acid uptake via FABP4 and FABP5 unlike circulating memory cells, possibly as a metabolic adaption to the skin microenvironment (Pan et al., 2017). Selective blockade of fatty acid uptake and IL-15, CD103, and TGF-β activation are all promising approaches to selectively deplete TRM cells.

Skin recirculating memory CD8+ T cells

In addition to TRM cells that are long-term residents of the skin, there is a population of CD8+ memory cells that circulate between skin and lymphoid tissues (e.g., lymph node and spleen) (sTCIRC cells) (Hirai et al., 2019) (Table 1). These cells are induced efficiently by epicutaneous vaccinia virus infection but not by intravenous infection. They express E- and P-selectin ligands and are a subset of classic circulating memory CD8+ T cells identified as KLRG1−CD127+ or CXCR3+CX3CR1dim-mid in lymphoid tissues and blood. Under steady-state conditions and in the absence of antigen, sTCIRC cells enter the skin via G protein-coupled receptors (i.e., chemokine receptors) and likely E- and P-selectin ligands because uninflamed skin endothelial cells constitutively express E-selectin (Keelan et al., 1994). sTCIRC cells do not express CD69 and use S1PR1 to exit the skin through lymphatics. Unexpectedly, sTCIRC cells share with TRM cells a requirement for keratinocyte-mediated activation of TGF-β for their long-term persistence. Vaccinia virus–specific sTCIRC cells are lost after transfer into mice lacking TGF-β–activating integrins in the skin. On the other hand, memory CD8+ T cells that cannot respond to TGF-β persist following systemic Listeria infection, suggesting that TGF-β is not a general requirement of circulating CD8+ memory cells; it is only required for sTCIRC cell persistence in skin (Hirai et al., 2019; Ma and Zhang, 2015).

Table 1.

Comparison of Two Unique Subsets of CD8+ Memory T Cells in Murine Skin

| Characteristic | TRM cells | sTCIRC cells |

|---|---|---|

| Steady state residency | Resident in skin | Transiently in skin |

| Markers in skin | CD69+CD103+ | CD69− |

| Requirement for TGF-β | Yes | Yes |

| Host defense to viral reinfection | Yes | Yes |

| Function for skin homeostasis | Yes | ? |

| Longevity | Yes | ? |

| Terminally differentiated | No? | No? |

Abbreviations: sTCIRC cell, skin-homing circulating memory T cell; TGF-β, transforming growth factor-β; TRM cell, resident memory T cell.

During steady state conditions, sTCIRC and TRM cells appear to be distinct and independent populations of memory cells. Parabiosis experiments joining naïve mice with mice previously infected with vaccinia virus that house large numbers of TRM cells in their epidermis have elegantly demonstrated that epidermal TRM cells do not seed distant skin sites and sTCIRC cells do not differentiate into TRM cells in the steady state (Enamorado et al., 2017; Jiang et al., 2012). However, in vaccinia virus–infected mice, skin sites distant from the location of infection do accumulate TRM cells (Enamorado et al., 2017; Jiang et al., 2012). Because TRM cells do not migrate through the epidermis (Zaid et al., 2014), there may be TRM cell precursors that can seed distant skin sites in the absence of local inflammation. In the context of re-encounter with antigen in skin, circulating memory cells can form skin TRM cells (Enamorado et al., 2017; Park et al., 2018b). This likely also occurs following inflammation in the absence of antigen (Beura et al., 2018a). Finally, it is becoming clear that TRM cells may have the capacity to exit peripheral tissues in certain contexts. Following antigen encounter, TRM cells were observed exiting skin and became lymph node resident memory cells (Beura et al., 2018b). Though the biological significance of this work remains unclear and it was not observed by another group using a herpes simplex virus model (Park et al., 2018b), it is likely TRM cells are not terminally differentiated and may, under specific conditions, contribute to other populations of memory cells.

Function of resident and recirculating memory CD8+ T cells

TRM cells provide a very strong anamnestic host defense against re-encounter with viruses such as vaccinia virus and herpes simplex virus (Gebhardt et al., 2009; Jiang et al., 2012). TRM cells themselves directly provide antiviral immunity, and the strength of protection correlates with the density of TRM cells (Mackay et al., 2015b; Park et al., 2018b). During viral infection, sTCIRC cells also support host defense (Hirai et al., 2019). TRM cells, however, provide a faster and more potent host defense, likely because of their position at the site of infection (Gaide et al., 2015; Jiang et al., 2012). TRM cells also possess a potent alarm function that recruits circulating memory cells to the site of infection and activates local innate and adaptive effectors to provide protection against even antigenically unrelated viruses (Ariotti et al., 2014; Schenkel et al., 2013; Schenkel et al., 2014).

In addition to providing antiviral host defense, TRM cells provide immunosurveillance that protects against melanoma development. In mice, melanoma-specific TRM cells actively suppress growth in undetectable melanoma lesions, thereby establishing a melanoma-immune equilibrium in mice (Park et al., 2018a). Deletion of TRM cells disrupts this equilibrium and allows for melanoma outgrowth. In addition, TRM cells associated with vitiligo in a mouse model are protective against melanoma, which is consistent with the observation that vitiligo is a positive prognostic factor in patients with melanoma (Malik et al., 2017). Interestingly, tumor-infiltrated CD8+ T cells share a core tissue-residency gene expression signature with TRM cells that is associated with RUNX3 activity. Runx3-deficient T cells cannot accumulate in melanoma tumors (Milner et al., 2017). Thus, it appears that tumor-infiltrated CD8+ T cells are closely related to TRM cells. Circulating CD8+ memory cells also provide protection against melanoma (Enamorado et al., 2017). Although most studies have focused on melanoma, it is likely that TRM and sTCIRC cells also participate in immunosurveillance of other malignant neoplasms (Afanasiev et al., 2013; Oguejiofor et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2013).

TRM cells and skin microbiome

Murine epidermis is populated by two types of T cells under steady state conditions, TRM cells and γδ dendritic epidermal T cells (DETCs). At birth, DETCs dominate the epidermal niche, but as TRM cells are recruited into the epidermis through microbial exposure, they begin to displace DETCs. The murine epidermal niche appears to have a maximum T-cell density it can support, because the numbers of TRM cells and DETCs are regulated to maintain an invariable total number of T cells in the epidermis (Zaid et al., 2014). Once DETCs are displaced by TRM cells, they do not return as they develop only during the embryonic period (Havran and Allison, 1988; Havran and Allison, 1990). Thus with increasing age and microbial colonization comes accumulation of antigen experience that results in increased TRM cell density. Naïve specific pathogenefree mice have more γδ T cells than αβ T cells in both the epidermis and dermis (Sumaria et al., 2011). In contrast, “dirty mice” that are made by cohousing specific pathogen–free mice with pet shop mice have far fewer skin γδ T cells than αβ T cells and mimic human skin (Beura et al., 2016; Falini et al., 1989; Groh et al., 1989). Specific pathogen–free mice that undergo association with the human skin commensal Staphylococcus epidermidis develop antigen specific skin TRM cells expressing IL-17A (Linehan et al., 2018; Naik et al., 2012; Naik et al., 2015). IL-17A from S. epidermidis–specific TRM cells augments innate host defense against unrelated pathogens such as Candida albicans and can release type 2 cytokines under specific conditions (Harrison et al., 2018; Naik et al., 2015). Notably, these TRM cells also promote wound healing, a function also attributed to DETCs (Harrison et al., 2018; Linehan et al., 2018; Nielsen et al., 2017). Thus, in addition to providing host defense, S. epidermidis–specific TRM cells also have an important role in maintaining skin homeostasis.

CD8+ memory cells promote vitiligo and alopecia areata

Vitiligo and alopecia areata are type 1 CD8+ T cell–driven autoimmune skin diseases in which perforin- and granzyme B–mediated death of melanocytes and follicular keratinocytes, respectively, leads to loss of pigmentation and terminal hairs (Deng et al., 2019; Gilhar et al., 2016; Islam et al., 2015; Riding and Harris, 2019; Trüeb and Dias, 2018; Willemsen et al., 2019). Both of these disorders feature focal well-demarcated lesions that persist long term in specific locations. The fixed and protracted inflammation characteristic of vitiligo and alopecia areata is illustrative of long-term persistence of pathogenic CD8 TRM cells in skin, but circulating memory cells also have important contributions to the pathogenesis of these diseases (Clark, 2015).

Melanocyte-specific CD69+CD103+ TRM cells are highly enriched in the epidermis of both mouse and human vitiligo skin relative to healthy skin (Boniface et al., 2018; Richmond et al., 2018), and CD8+ T cells isolated from lesional skin of patients with vitiligo can transfer disease to unaffected autologous skin, implicating TRM cells in disease initiation (Riding and Harris, 2019). Although melanocyte-specific CD8+ T cells are detectable in the blood of both patients with vitiligo and healthy controls, only patients with vitiligo exhibit HLA-A2*0201 MART1−, gp100-, and tyrosinase pentamer–positive cells in skin, indicating that the presence of circulating melanocyte-specific T cells alone is not sufficient to induce vitiligo (Ogg et al., 1998; Richmond et al., 2013; van den Boorn et al., 2009).

Interference with tissue-derived TRM-cell developmental and survival signals is a rational design for new therapeutics. In mice and humans, locally produced IL-15 supports the generation of cutaneous TRM cells, and melanocyte-specific murine TRM cells express the IL-15 receptor β chain CD122 to a greater degree than non–melanocyte-reactive TRM cells (Adachi et al., 2015; Cheuk et al., 2017; Mackay et al., 2015b; Richmond et al., 2018; Skon et al., 2013). Short-term treatment with anti-CD122 antibody in a mouse model of vitiligo resulted in reduced TRM cells and lasting repigmentation of vitiligo lesions (Richmond et al., 2018). Interventions that prevent entry of circulating memory CD8+ T cells into skin also ameliorate established disease (Richmond et al., 2019). Thus, in mice, both TRM and circulating memory CD8+ T cells (likely sTCIRC cells) participate in disease pathogenesis.

Alopecia areata is CD8+ T cell–dependent but is a complex, polygenic disease with clear contributions by CD4+ T cells, other NKG2D+ cells, keratinocytes, fibroblasts, mast cells, dendritic cells, and B cells (Gilhar et al., 2012). As is the case with vitiligo, skin grafts and CD8+ T cells purified from lesional human skin can transfer disease (Gilhar et al., 1998; Silva and Sundberg, 2013). However, induction of alopecia occurs at sites both adjacent to and distant from grafted skin (Silva and Sundberg, 2013), and local deposition of CD8+ T cells derived from the lymph nodes and spleen of diseased mice were sufficient to induce alopecia areata in healthy mice (McElwee et al., 2005). Thus, TRM cells contribute to alopecia areata, but sTCIRC cells also appear to have an important pathogenic role.

Interference with cytokine signaling (antibody-mediated IFNγ/IL-2 blockade), TRM cell survival (antibody-mediated CD122 blockade), and T-cell costimulation (CTLA-4 Ig) have all been explored as treatment options for vitiligo and alopecia areata (Gilhar et al., 2016). One of the most promising new therapies, however, for both alopecia areata and vitiligo is blockade of Jaks, which are signaling molecules downstream of many pro-inflammatory cytokine receptors. IL-15 and IFNγ signaling both require Jak1 (Ghoreschi et al., 2009; Hong and Van Kaer, 1999). Patients with alopecia areata treated with tofactitinib, a small molecule inhibitor with relative selectivity for Jak1/3 over Jak2, or ruxolitinib, a Jak1/2 inhibitor, eliminated the IFNγ transcriptional signature in alopecia areata lesions and reduced peribulbar CD8+ T-cell infiltration (Kennedy Crispin et al., 2016; Xing et al., 2014). Most patients experienced near complete hair regrowth within 3–6 months of onset of treatment, which was steadily lost following cessation of therapy (Jabbari et al., 2015; Kennedy Crispin et al., 2016; Mackay-Wiggan et al., 2016; Xing et al., 2014). Tofacitinib has also shown efficacy in the treatment of vitiligo (Craiglow and King, 2015; Damsky and King, 2017; Kim et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2017). Reduction of CD8+ T-cell number in treatment-responsive skin occurred following tofacitinib treatment, but blood auto-reactive CD8+ T cells were not decreased (Liu et al., 2017). One of the challenges to determining functional specialization of T cells in skin is that circulating memory CD8+ T cells may have the capacity to repopulate epidermal TRM cells following TRM cell–depleting therapy. Thus, successful strategies to induce long-lasting remission of vitiligo and alopecia areata may need to efficiently target both TRM and circulating memory CD8+ T cells.

Future directions for intervention to skin memory CD8+ T cells

Several lines of evidence from murine models underscore the importance of cutaneous memory CD8+ T cells in host defense, cancer immunosurveillance, and autoimmune inflammation. Mounting evidence suggests that these roles translate to human skin biology. However, many key questions about skin CD8+ memory T cells remain. An important question is to what extent observations made in mice exemplify human skin both in homeostasis and in disease states. There are clearly similarities but also some differences that must be defined. Another important concept is how CD8+ T cells compete and communicate with other T cells, dendritic cells, and innate lymphoid cells within the epidermal niche. In mice, there is competition between DETCs and TRM cells, but whether TRM cells of different specificities compete and whether this can be dysregulated perhaps in the tumor microenvironment is unclear. In addition, the cutaneous microbiome clearly affects skin memory CD8+ T cells, but the details of these interactions and whether the microbiome can be manipulated for therapeutic benefit are only just beginning to be explored. There is also emerging evidence that TRM cells may have the capacity to exit the skin and reside in lymphoid and possibly other tissues. Finally, efforts to manipulate skin memory CD8+ T cells, either to augment their numbers to enhance host defense (Schenkel et al., 2016; Vezys et al., 2009) or deplete them for treatment of autoimmune disease are only just beginning, but appear to be promising strategies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the members of the Kaplan laboratory for helpful discussions. TH was supported by JSPS Overseas Research Fellowships; SKW is supported by a Dermatology Foundation Career Development Award and Research Grants from National Psoriasis Foundation and American Skin Association; DHK by NIH R01AR060744.

Abbreviations:

- DETC

dendritic epidermal T cell

- sTCIRC cell

skin-homing circulating memory T cell

- TGF-β

transforming growth factor-β

- TRM cell

resident memory T cell

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors state no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- Adachi T, Kobayashi T, Sugihara E, Yamada T, Ikuta K, Pittaluga S, et al. Hair follicle-derived IL-7 and IL-15 mediate skin-resident memory T cell homeostasis and lymphoma. Nat Med 2015;21:1272–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afanasiev OK, Nagase K, Simonson W, Vandeven N, Blom A, Koelle DM, et al. Vascular E-selectin expression correlates with CD8 lymphocyte infiltration and improved outcome in Merkel cell carcinoma. J Invest Dermatol 2013;133:2065–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ariotti S, Hogenbirk MA, Dijkgraaf FE, Visser LL, Hoekstra ME, Song JY, et al. Skin-resident memory CD8+ T cells trigger a state of tissue-wide pathogen alert. Science 2014;346:101–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beura LK, Hamilton SE, Bi K, Schenkel JM, Odumade OA, Casey KA, et al. Normalizing the environment recapitulates adult human immune traits in laboratory mice. Nature 2016;532:512–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beura LK, Mitchell JS, Thompson EA, Schenkel JM, Mohammed J, Wijeyesinghe S, et al. Intravital mucosal imaging of CD8+ resident memory T cells shows tissue-autonomous recall responses that amplify secondary memory. Nat Immunol 2018a;19:173–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beura LK, Wijeyesinghe S, Thompson EA, Macchietto MG, Rosato PC, Pierson MJ, et al. T cells in nonlymphoid tissues give rise to lymph-node-resident memory T cells. Immunity 2018b;48:327–38.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boniface K, Jacquemin C, Darrigade AS, Dessarthe B, Martins C, Boukhedouni N, et al. Vitiligo skin is imprinted with resident memory CD8 T cells expressing CXCR3. J Invest Dermatol 2018;138:355–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bos JD, Zonneveld I, Das PK, Krieg SR, van der Loos CM, Kapsenberg ML. The skin immune system (SIS): distribution and immunophenotype of lymphocyte subpopulations in normal human skin. J Invest Dermatol 1987;88:569–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bromley SK, Mempel TR, Luster AD. Orchestrating the orchestrators: chemokines in control of T cell traffic. Nat Immunol 2008;9:970–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey KA, Fraser KA, Schenkel JM, Moran A, Abt MC, Beura LK, et al. Antigen-independent differentiation and maintenance of effector-like resident memory T cells in tissues. J Immunol 2012;188:4866–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheuk S, Schlums H, Gallais Sérézal I, Martini E, Chiang SC, Marquardt N, et al. CD49a expression defines tissue-resident CD8+ T cells poised for cytotoxic function in human skin. Immunity 2017;46:287–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark RA. Resident memory T cells in human health and disease. Sci Transl Med 2015;269:269rv1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark RA, Chong B, Mirchandani N, Brinster NK, Yamanaka K-I, Dowgiert RK, et al. The vast majority of CLA T cells are resident in normal skin. J Immunol 2006;176:4431–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craiglow BG, King BA. Tofacitinib citrate for the treatment of vitiligo: A pathogenesis-directed therapy. JAMA Dermatol 2015;151:1110–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damsky W, King BA. JAK inhibitors in dermatology: the promise of a new drug class. J Am Acad Dermatol 2017;76:736–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng Q, Luo Y, Chang C, Wu H, Ding Y, Xiao R. The emerging epigenetic role of CD8+T cells in autoimmune diseases: A systematic review. Front Immunol 2019;10:856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Asady R, Yuan R, Liu K, Wang D, Gress RE, Lucas PJ, et al. TGF-{beta}-dependent CD103 expression by CD8(+) T cells promotes selective destruction of the host intestinal epithelium during graft-versus-host disease. J Exp Med 2005;201:1647–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enamorado M, Iborra S, Priego E, Cueto FJ, Quintana JA, Martínez-Cano S, et al. Enhanced anti-tumour immunity requires the interplay between resident and circulating memory CD8+ T cells. Nat Commun 2017;8: 16073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falini B, Flenghi L, Pileri S, Pelicci P, Fagioli M, Martelli MF, et al. Distribution of T cells bearing different forms of the T cell receptor gamma/delta in normal and pathological human tissues. J Immunol 1989;143:2480–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster CA, Yokozeki H, Rappersberger K, Koning F, Volc-Platzer B, Rieger A, et al. Human epidermal T cells predominantly belong to the lineage expressing alpha/beta T cell receptor. J Exp Med 1990;171:997–1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaide O, Emerson RO, Jiang X, Gulati N, Nizza S, Desmarais C, et al. Common clonal origin of central and resident memory T cells following skin immunization. Nat Med 2015;21:647–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebhardt T, Wakim LM, Eidsmo L, Reading PC, Heath WR, Carbone FR. Memory T cells in nonlymphoid tissue that provide enhanced local immunity during infection with herpes simplex virus. Nat Immunol 2009;10: 524–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebhardt T, Whitney PG, Zaid A, Mackay LK, Brooks AG, Heath WR, et al. Different patterns of peripheral migration by memory CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Nature 2011;477:216–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehad A, Teague JE, Matos TR, Huang V, Yang C, Watanabe R, et al. A primary role for human central memory cells in tissue immunosurveillance. Blood Adv 2018;2:292–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghoreschi K, Laurence A, O’Shea JJ. Janus kinases in immune cell signaling. Immunol Rev 2009;228:273–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilhar A, Etzioni A, Paus R. Alopecia areata. N Engl J Med 2012;366: 1515–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilhar A, Schrum AG, Etzioni A, Waldmann H, Paus R. Alopecia areata: animal models illuminate autoimmune pathogenesis and novel immunotherapeutic strategies. Autoimmun Rev 2016;15:726–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilhar A, Ullmann Y, Berkutzki T, Assy B, Kalish RS. Autoimmune hair loss (alopecia areata) transferred by T lymphocytes to human scalp explants on SCID mice. J Clin Invest 1998;101:62–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groh V, Porcelli S, Fabbi M, Lanier LL, Picker LJ, Anderson T, et al. Human lymphocytes bearing T cell receptor gamma/delta are phenotypically diverse and evenly distributed throughout the lymphoid system. J Exp Med 1989;169:1277–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison OJ, Linehan JL, Shih H-Y, Bouladoux N, Han S-J, Smelkinson M, et al. Commensal-specific T cell plasticity promotes rapid tissue adaptation to injury. Science 2018;363:eaat6280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havran WL, Allison JP. Developmentally ordered appearance of thymocytes expressing different T-cell antigen receptors. Nature 1988;335:443–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havran WL, Allison JP. Origin of Thy-1 + dendritic epidermal cells of adult mice from fetal thymic precursors. Nature 1990;344:68–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickman HD, Reynoso GV, Ngudiankama BF, Cush SS, Gibbs J, Bennink JR, et al. CXCR3 chemokine receptor enables local CD8(+) T cell migration for the destruction of virus-infected cells. Immunity 2015;42:524–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirai T, Zenke Y, Yang Y, Bartholin L, Beura LK, Masopust D, et al. Keratinocyte-mediated activation of the cytokine TGF-β Maintains Skin Recirculating Memory CD8+ T cells. Immunity 2019;50:1249–61.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirata T, Furie BC, Furie B. P-, E-, and L-selectin mediate migration of activated CD8+ T lymphocytes into inflamed skin. J Immunol 2002;169: 4307–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homey B, Alenius H, Müller A, Soto H, Bowman EP, Yuan W, et al. CCL27-CCR10 interactions regulate T cell-mediated skin inflammation. Nat Med 2002;8:157–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homey B, Wang W, Soto H, Buchanan ME, Wiesenborn A, Catron D, et al. Cutting edge: the orphan chemokine receptor G protein-coupled receptor-2 (GPR-2, CCR10) binds the skin-associated chemokine CCL27 (CTACK/ALP/ILC). J Immunol 2000;164:3465–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong S, Van Kaer L. Immune privilege: keeping an eye on natural killer T cells. J Exp Med 1999;190:1197–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam N, Leung PSC, Huntley AC, Gershwin ME. The autoimmune basis of alopecia areata: a comprehensive review. Autoimmun Rev 2015;14:81–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jabbari A, Dai Z, Xing L, Cerise JE, Ramot Y, Berkun Y, et al. Reversal of alopecia areata following treatment with the JAK1/2 inhibitor Baricitinib. EBioMedicine 2015;2:351–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X, Clark RA, Liu L, Wagers AJ, Fuhlbrigge RC, Kupper TS. Skin infection generates non-migratory memory CD8 TRM cells providing global skin immunity. Nature 2012;483:227–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kansas GS. Selectins and their ligands: current concepts and controversies. Blood 1996;88:3259–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashem SW, Haniffa M, Kaplan DH. Antigen-presenting cells in the skin. Annu Rev Immunol 2017;35:469–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keelan ETM, Licence ST, Peters AM, Binns RM, Haskard DO. Characterization of E-selectin expression in vivo with use of a radiolabeled monoclonal antibody. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 1994;266:H279–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy Crispin M, Ko JM, Craiglow BG, Li S, Shankar G, Urban JR, et al. Safety and efficacy of the JAK inhibitor tofacitinib citrate in patients with alopecia areata. JCI Insight 2016;1:e89776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan TN, Mooster JL, Kilgore AM, Osborn JF, Nolz JC. Local antigen in nonlymphoid tissue promotes resident memory CD8 T cell formation during viral infection. J Exp Med 2016;213:951–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SR, Heaton H, Liu LY, King BA. Rapid repigmentation of vitiligo using tofacitinib plus low-dose, narrowband UV-B phototherapy. JAMA Dermatol 2018;154:370–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klunker S, Trautmann A, Akdis M, Verhagen J, Schmid-Grendelmeier P, Blaser K, et al. A second step of chemotaxis after transendothelial migration: keratinocytes undergoing apoptosis release IFN-gamma-inducible protein 10, monokine induced by IFN-gamma, and IFN-gamma-inducible alpha-chemoattractant for T cell chemotaxis toward epidermis in atopic dermatitis. J Immunol 2003;171:1078–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupper TS, Fuhlbrigge RC. Immune surveillance in the skin: mechanisms and clinical consequences. Nat Rev Immunol 2004;4:211–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan JL, Harrison OJ, Han S-J, Byrd AL, Vujkovic-Cvijin I, Villarino AV, et al. Non-classical immunity controls microbiota impact on skin immunity and tissue repair. Cell 2018;172:784–6.e18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu LY, Strassner JP, Refat MA, Harris JE, King BA. Repigmentation in vitiligo using the Janus kinase inhibitor tofacitinib may require concomitant light exposure. J Am Acad Dermatol 2017;77:675–82.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma C, Zhang N. Transforming growth factor-β signaling is constantly shaping memory T-cell population. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2015;112: 11013–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackay LK, Braun A, Macleod BL, Collins N, Tebartz C, Bedoui S, et al. Cutting edge: CD69 interference with sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor function regulates peripheral T cell retention. J Immunol 2015a;194: 2059–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackay LK, Minnich M, Kragten NAM, Liao Y, Nota B, Seillet C, et al. Hobit and Blimp 1 instruct a universal transcriptional program of tissue residency in lymphocytes. Science 2016;352:459–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackay LK, Rahimpour A, Ma JZ, Collins N, Stock AT, Hafon ML, et al. The developmental pathway for CD103( )CD8 tissue-resident memory T cells of skin. Nat Immunol 2013;14:1294–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackay LK, Stock AT, Ma JZ, Jones CM, Kent SJ, Mueller SN, et al. Long-lived epithelial immunity by tissue-resident memory T (TRM) cells in the absence of persisting local antigen presentation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2012;109: 7037–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackay LK, Wynne-Jones E, Freestone D, Pellicci DG, Mielke LA, Newman DM, et al. T-box transcription factors combine with the cytokines TGF-β and IL-15 to control tissue-resident memory T cell fate. Immunity 2015b;43:1101–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackay-Wiggan J, Jabbari A, Nguyen N, Cerise JE, Clark C, Ulerio G, et al. Oral Ruxolitinib induces hair regrowth in patients with moderate-to-severe alopecia areata. JCI Insight 2016;1:e89790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malik BT, Byrne KT, Vella JL, Zhang P, Shabaneh TB, Steinberg SM, et al. Resident memory T cells in the skin mediate durable immunity to melanoma. Sci Immunol 2017;2:eaam6346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCully ML, Collins PJ, Hughes TR, Thomas CP, Billen J, O’Donnell VB, et al. Skin metabolites define a new paradigm in the localization of skin tropic memory T cells. J Immunol 2015;195:96–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCully ML, Ladell K, Andrews R, Jones RE, Miners KL, Roger L, et al. CCR8 expression defines tissue-resident memory T cells in human skin. J Immunol 2018;200:1639–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCully ML, Ladell K, Hakobyan S, Mansel RE, Price DA, Moser B. Epidermis instructs skin homing receptor expression in human T cells. Blood 2012;120:4591–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McElwee KJ, Freyschmidt-Paul P, Hoffmann R, Kissling S, Hummel S, Vitacolonna M, et al. Transfer of CD8 cells induces localized hair loss whereas CD4+/CD25 cells promote systemic alopecia areata and CD4+/CD25 cells blockade disease onset in the C3H/HeJ mouse model. J Invest Dermatol 2005;124:947–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mempel TR, Henrickson SE, Von Andrian UH. T-cell priming by dendritic cells in lymph nodes occurs in three distinct phases. Nature 2004;427: 154–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milner JJ, Toma C, Yu B, Zhang K, Omilusik K, Phan AT, et al. Runx3 programs CD8 T cell residency in non-lymphoid tissues and tumours. Nature 2017;552:253–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed J, Beura LK, Bobr A, Astry B, Chicoine B, Kashem SW, et al. Stromal cells control the epithelial residence of DCs and memory T cells by regulated activation of TGF-β. Nat Immunol 2016;17: 414–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muschaweckh A, Buchholz VR, Fellenzer A, Hessel C, König PA, Tao S, et al. Antigen-dependent competition shapes the local repertoire of tissue-resident memory CD8+ T cells. J Exp Med 2016;213:3075–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naik S, Bouladoux N, Linehan JL, Han S-J, Harrison OJ, Wilhelm C, et al. Commensal-dendritic-cell interaction specifies a unique protective skin immune signature. Nature 2015;520:104–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naik S, Bouladoux N, Wilhelm C, Molloy MJ, Salcedo R, Kastenmuller W, et al. Compartmentalized control of skin immunity by resident commensals. Science 2012;337:1115–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen MM, Witherden DA, Havran WL. γδ T cells in homeostasis and host defence of epithelial barrier tissues. Nat Rev Immunol 2017;17:733–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogg GS, Rod Dunbar P, Romero P, Chen JL, Cerundolo V. High frequency of skin-homing melanocyte-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes in autoimmune vitiligo. J Exp Med 1998;188:1203–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oguejiofor K, Hall J, Slater C, Betts G, Hall G, Slevin N, et al. Stromal infiltration of CD8 T cells is associated with improved clinical outcome in HPV-positive oropharyngeal squamous carcinoma. Br J Cancer 2015;113: 886–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan Y, Tian T, Park CO, Lofftus SY, Mei S, Liu X, et al. Survival of tissue-resident memory T cells requires exogenous lipid uptake and metabolism. Nature 2017;543:252–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SL, Buzzai A, Rautela J, Hor JL, Hochheiser K, Effern M, et al. Tissue-resident memory CD8 T cells promote melanoma-immune equilibrium in skin. Nature 2018a;565:366–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SL, Zaid A, Hor JL, Christo SN, Prier JE, Davies B, et al. Local proliferation maintains a stable pool of tissue-resident memory T cells after antiviral recall responses. Nat Immunol 2018b;19:183–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richmond JM, Frisoli ML, Harris JE. Innate immune mechanisms in vitiligo: danger from within. Curr Opin Immunol 2013;25:676–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richmond JM, Strassner JP, Rashighi M, Agarwal P, Garg M, Essien KI, et al. Resident memory and recirculating memory T cells cooperate to maintain disease in a mouse model of vitiligo. J Invest Dermatol 2019;139: 769–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richmond JM, Strassner JP, Zapata L, Garg M, Riding RL, Refat MA, et al. Antibody blockade of IL-15 signaling has the potential to durably reverse vitiligo. Sci Transl Med 2018;10:eaam7710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riding RL, Harris JE. The role of memory CD8 T cells in vitiligo. J Immunol 2019;203:11–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santamaria Babi LF, Moser R, Perez Soler MT, Picker LJ, Blaser K, Hauser C. Migration of skin-homing T cells across cytokine-activated human endothelial cell layers involves interaction of the cutaneous lymphocyte-associated antigen (CLA), the very late antigen-4 (VLA-4), and the lymphocyte function-associated antigen-1 (LFA-1). J Immunol 1995;154: 1543e50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaerli P, Ebert L, Willimann K, Blaser A, Roos RS, Loetscher P, et al. A skin-selective homing mechanism for human immune surveillance T cells. J Exp Med 2004;199:1265–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenkel JM, Fraser KA, Beura LK, Pauken KE, Vezys V, Masopust D. Resident memory CD8 T cells trigger protective innate and adaptive immune responses. Science 2014;346:98–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenkel JM, Fraser KA, Casey KA, Beura LK, Pauken KE, Vezys V, et al. IL-15-independent maintenance of tissue-resident and boosted effector memory CD8 T cells. J Immunol 2016;196:3920–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenkel JM, Fraser KA, Vezys V, Masopust D. Sensing and alarm function of resident memory CD8⁺ T cells. Nat Immunol 2013;14:509–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schön MP, Zollner TM, Boehncke WH. The molecular basis of lymphocyte recruitment to the skin: clues for pathogenesis and selective therapies of inflammatory disorders. J Invest Dermatol 2003;121:951–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiow LR, Rosen DB, Brdicková N, Xu Y, An J, Lanier LL, et al. CD69 acts downstream of interferon-alpha/beta to inhibit S1P1 and lymphocyte egress from lymphoid organs. Nature 2006;440:540–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva KA, Sundberg JP. Surgical methods for full-thickness skin grafts to induce alopecia areata in C3H/HeJ mice. Comp Med 2013;63:392–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skon CN, Lee JY, Anderson KG, Masopust D, Hogquist KA, Jameson SC. Transcriptional downregulation of S1pr1 is required for the establishment of resident memory CD8+ T cells. Nat Immunol 2013;14: 1285–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinert EM, Schenkel JM, Fraser KA, Beura LK, Manlove LS, Igyártó BZ, et al. Quantifying memory CD8 T cells reveals regionalization of immunosurveillance. Cell 2015;161:737–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumaria N, Roediger B, Ng LG, Qin J, Pinto R, Cavanagh LL, et al. Cutaneous immunosurveillance by self-renewing dermal γδ T cells. J Exp Med 2011;208:505–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swerlick RA, Lee KH, Li LJ, Sepp NT, Caughman SW, Lawley TJ. Regulation of vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 on human dermal microvascular endothelial cells. J Immunol 1992;149:698–705. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomsen AR, Nansen A, Madsen AN, Bartholdy C, Christensen JP. Regulation of T cell migration during viral infection: role of adhesion molecules and chemokines. Immunol Lett 2003;85:119–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trüeb RM, Dias MFRG. Alopecia areata: a comprehensive review of pathogenesis and management. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2018;54: 68–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Boorn JG, Konijnenberg D, Dellemijn TAM, van der Veen JP, Bos JD, Melief CJM, et al. Autoimmune destruction of skin melanocytes by perilesional T cells from vitiligo patients. J Invest Dermatol 2009;129: 2220–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vezys V, Yates A, Casey KA, Lanier G, Ahmed R, Antia R, et al. Memory CD8 T-cell compartment grows in size with immunological experience. Nature 2009;457:196–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh DA, da Silva HB, Beura LK, Peng C, Hamilton SE, Masopust D, et al. The functional requirement for CD69 in establishment of resident memory CD8 T cells varies with tissue location. J Immunol 2019;203: 946–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe R, Gehad A, Yang C, Scott LL, Teague JE, Schlapbach C, et al. Human skin is protected by four functionally and phenotypically discrete populations of resident and recirculating memory T cells. Sci Transl Med 2015;7:279:279ra39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weninger W, Manjunath N, von A, UH. Migration and differentiation of CD8+ T cells. Immunol Rev 2002;186:221–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willemsen M, Linkute R, Luiten RM, Matos TR. Skin-resident memory T cells as a potential new therapeutic target in vitiligo and melanoma. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res 2019;32:612–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worthington JJ, Klementowicz JE, Travis MA. TGFβ: a sleeping giant awoken by integrins. Trends Biochem Sci 2011;36:47–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing L, Dai Z, Jabbari A, Cerise JE, Higgins CA, Gong W, et al. Alopecia areata is driven by cytotoxic T lymphocytes and is reversed by JAK inhibition. Nat Med 2014;20:1043–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z, Mu Z, Dabovic B, Jurukovski V, Yu D, Sung J, et al. Absence of integrin-mediated TGFbeta1 activation in vivo recapitulates the phenotype of TGFbeta1-null mice. J Cell Biol 2007;176:787–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaid A, Hor JL, Christo SN, Groom JR, Heath WR, Mackay LK, et al. Chemokine receptor–dependent control of skin tissue–resident memory T cell formation. J Immunol 2017;199:2451–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaid A, Mackay LK, Rahimpour A, Braun A, Veldhoen M, Carbone FR, et al. Persistence of skin-resident memory T cells within an epidermal niche. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2014;111:5307–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S, Fujita H, Mitsui H, Yanofsky VR, Fuentes-Duculan J, Pettersen JS, et al. Increased Tc22 and Treg/CD8 ratio contribute to aggressive growth of transplant associated squamous cell carcinoma. PLOS ONE 2013;8:e62154.23667456 [Google Scholar]