Abstract

Poor prognosis for glioblastoma (GBM) is a consequence of the aggressive and infiltrative nature of gliomas where individual cells migrate away from the main tumor to distant sites, making complete surgical resection and treatment difficult. In this manuscript, we characterize an invasive pediatric glioma model and determine if nanoparticles linked to a peptide recognizing the GBM tumor biomarker PTPmu can specifically target both the main tumor and invasive cancer cells in adult and pediatric glioma models. Using both iron and lipid-based nanoparticles, we demonstrate by magnetic resonance imaging, optical imaging, histology, and iron quantification that PTPmu-targeted nanoparticles effectively label adult gliomas. Using PTPmu-targeted nanoparticles in a newly characterized orthotopic pediatric SJ-GBM2 model, we demonstrate individual tumor cell labeling both within the solid tumor margins and at invasive and dispersive sites.

Keywords: receptor type protein tyrosine phosphatase, PTPmu, glioblastoma, glioma, nanoparticle, tumor targeting, magnetic resonance contrast agent

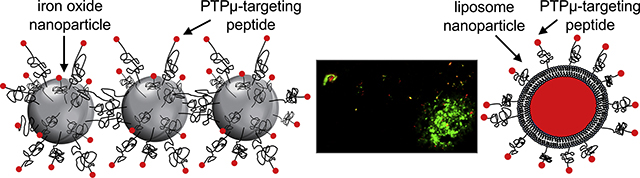

Graphical Abstract

Two PTPμ-targeting nanoparticles were developed to recognize tumor associated fragments of the receptor protein tyrosine phosphatase PTPμ in adult and pediatric glioma. When used as an intravenous labeling agent, the PTPμ-targeting liposomal nanoparticle (red) recognized invading pediatric glioma cells (green) that had migrated away from the main tumor mass, observable in tissue sections taken from a pediatric intracranial glioma tumor model.

Introduction

Pediatric brain tumors are the deadliest form of childhood cancer and the most common solid tumor of children aged 0–14 (1). While survival rates of many childhood brain cancers have increased over the past 40 years, survival rates for the highest-grade brain tumor, high-grade glioma including glioblastoma (GBM), have not improved (1, 2). For adults with GBM, the outlook is equally bleak, with current best practice treatment estimating a 14.6-month median survival timeframe (3). While maximal resection of the gadolinium-enhancing part of the brain tumor improves survival (4), it is widely recognized that microscopic invading cells outside of solid tumor margins remain and can cause up to a 97% recurrence rate in pediatric and adult patients (4). In contrast to the leakier and more angiogenic vessels associated with other cancers, drugs introduced systematically to treat GBM have limited effectiveness because of their inability to breach the impermeable blood brain barrier (BBB). While there is some degree of permeability within the solid tumor of a GBM, the BBB is maintained at invasive and distal dispersion sites causing a poor therapeutic index for standard chemotherapeutic treatments.

The dispersive and invasive cells characteristic of GBM contribute substantially to the high mortality associated with this disease (4). Thus, we focus on detecting and effectively targeting therapies to these cells using animal models that recapitulate the invasive growth characteristics of human GBM. Previously, we examined orthotopic adult brain tumor models using cryo-imaging and three-dimensional reconstructions of the entire brain (5). We described several adult GBM models, two of which we used in this study: the human glioma U-87 MG cell line and the rodent CNS-1 cell line (5). U-87 MG orthotopic xenograft tumors have highly proliferative main tumor masses with limited dispersal of tumor cells on blood vessels beyond the main tumor margins and no migration on white matter tracts (5). In contrast, the CNS-1 models are highly vascularized with necrotic cores and individual CNS-1 tumor cells exhibiting extensive dispersal along both white matter tracts and blood vessels (5).

To facilitate tumor targeting, we characterized a platform of molecular imaging agents that recognize a proteolytic fragment of the cell adhesion molecule PTPμ as a molecular marker of the main tumor and invasive cells in adult GBM (6–10). PTPμ is a transmembrane receptor-like protein tyrosine phosphatase that mediates homophilic cell–cell adhesion. In adult brain tumors, full-length PTPμ is proteolytically processed generating an extracellular fragment (11, 12) that serves as a biomarker for tumors (9, 10). A series of peptides, designated SBK peptides, were designed and conjugated to fluorophores to generate agents that recognize the PTPμ biomarker (10). The PTPμ agents cross the BBB to label intracranial tumors, and are stable for hours (10). Using an intracranial animal model of GBM, we three-dimensionally cryo-reconstructed whole brains and observed that the PTPμ agent can label up to 99% of all tumor cells including the main tumor mass as well as cells at the tumor margin (6). Furthermore, the PTPμ agent labels the main tumor and tumor margins successfully identifying invasive cells that have dispersed up to 4 mm away (6).

Herein, we describe new tumor targeting agents created by coupling the SBK peptides to a liposomal nanoparticle or an iron oxide-based nanoparticle. Liposomes were generated using common methods as described below. The iron oxide nanoparticle is comprised of three iron oxide (IO) nanospheres chemically linked into a linear, chain-like assembly (13, 14). The flexible, chain-like structure of this nanoparticle, termed nanochain, confers several attributes that make it an ideal agent for targeting invasive brain tumors (13–19). On one hand, this nanoparticle is visible in vivo using quantitative T2 magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) methods due to its IO content. Furthermore, the nanochain possesses a unique ability to survey the tumor endothelium by virtue of its rod-like oblong shape, which allows it to tumble out of the circulation due to torque forces within the blood (20). In addition, its high-aspect ratio makes it less likely to be endocytosed by macrophages either in the circulation or in tissues (20). The efficacy of nanochain targeting has been previously demonstrated by coating the nanochain particles with either a fibronectin, P-selectin or an αvβ3 integrin peptide targeting strategy (15, 18, 21). These targeted nanochains achieve rapid deposition on the vascular bed of glioma sites establishing well-distributed reservoirs on the endothelium of brain tumors for potential drug delivery (15, 18, 21).

In this manuscript, we also describe the development of a pediatric model of glioma using the cell line SJ-GBM2 derived from a pediatric GBM cell line. Using cryo-imaging and 3-D reconstruction, we characterized the progression of this pediatric brain tumor model by analyzing the growth and migration of individual cells along the vasculature and white matter tracts of the brain. Finally, we demonstrate that both the adult and pediatric models of GBM can be labeled with the PTPμ-targeted nanoparticles. Our studies show that PTPμ-targeted nanoparticles label pediatric and adult GBM tumor cells in the brain rapidly and with site specificity, even deep in interstitial and invasive tumor sites.

Methods

Orthotopic Xenograft Intracranial Adult and Pediatric Tumors

NIH athymic nude female mice (NCr-nu/+, NCr-nu/nu) were bred in the Athymic Animal Core Facility and housed in the Case Center for Imaging Research at Case Western Reserve University according to the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved animal protocols. Human U-87 MG glioma cells were obtained from American Type Culture Collection. CNS-1 rodent glioma cells were obtained from Mariano S. Viapiano (22). SJ-GBM2 cells were derived from a post-mortem 5-year old female patient with GBM (23, 24) and were obtained from Children’s Oncology Group Cell Line & Xenograft Repository. Where indicated, cells were infected with lentivirus to express green fluorescent protein (GFP) (25) or m-Cherry and intracranial implantation of tumor cells was performed as described (5). Briefly, mice 6 to 7 weeks of age were anesthetized and fitted into a stereotaxic rodent frame (David Kopf Instruments, Tujunga, California). A small burr hole was made 0.7 mm anterior and 2 mm lateral from bregma. Cells were harvested for intracranial implantation and deposited into the right striatum at a depth of −3 mm from the dura using a 10 μL syringe. A total of 2 × 105 U-87 MG cells, 4.5 × 104 CNS-1 cells, or 3 × 105 SJ-GBM2 cells were injected. Mice were imaged as described below then sacrificed 8–21 days post tumor implant. Brain tissue was collected for either iron quantification or histological processing.

Synthesis of Iron Oxide Nanoparticles

Iron oxide nanoparticles were synthesized using a co-precipitation method of Fe2+ and Fe3+ ions in the presence of sodium hydroxide as described (21, 26). Briefly, an iron chloride mixture consisting of 1 mol FeCl3.6H2O: 2 mol FeCl2.4H2O was reconstituted in water then dissociated in 0.4 M HCl solution and added to a solution of 0.5 M NaOH at 80°C in the presence of an inert gas. The resultant iron oxide nanoparticles were cleaned via magnetic separation and subsequently washed until a stable ferrofluid was established. To prevent agglomeration of the iron oxide nanoparticles, the particles were coated with citric acid. The solution was heated to 80°C for 2 h under a constant flow of nitrogen gas. Large uncoated particles were removed through multiple centrifugation steps. The nanoparticles were concentrated and excess citric acid was removed.

Citric acid coated iron oxide nanoparticles (CA-IOs) were functionalized using either silane-PEG-NH2 or silane-PEG-COOH (PEG, MW: 2000). Prior to functionalization, CA-IOs were concentrated and the pH was adjusted to 11. A 1:1 ratio by mass of silane-PEG-NH2 to CA-IOs was reacted. The nanoparticle solution was heated to covalently link the CA-IO with the silane group of the polymer. The functionalized iron oxide nanoparticles (Fe3O4-silane-PEG-NH2 or IO-NH2) were concentrated and stored at 4°C. Similar procedures were used to develop carboxylic acid functionalized iron oxide nanoparticles (IO-COOH) (21, 26).

The mono-functionalized iron oxide nanoparticles, IO-NH2 and IO-COOH, were first transferred from water to organic phase in dimethylformamide (DMF). The carboxylic functional group on the IO-COOH was activated with N,N’-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide. To develop the nanochain particle, a ~ 2:1 ratio of IO-NH2 to activated IO-COOH was mixed together and allowed to react for 30 min. The reaction was stopped by capping the activated carboxylic acids with ethylenediamine. The resultant nanochains were transferred back into water phase by magnetic separation and multiple washes (21, 26).

Functionalization of Chain-like Nanoparticles

Using sulfo-SMCC chemistry (26), we chemically linked the amine-functionalized nanochain linked to sulfo -SMCC then conjugated to the terminal thiol group added to the SBK2 peptide. SBK2 is the targeting peptide that binds to the PTPμ biomarker found in both invasive and distal infiltrating regions of brain tumors (6, 10). Available amine functional groups on the nanoparticle were linked to sulfo-SMCC then SBK2 in a 1:2:3 molar ratio of available functional groups for a total reaction time of 2.5 h. To remove excess reactants and peptides, the functionalized nanochains were dialyzed against 1x PBS in a 100 kDa molecular cut-off dialysis bag.

Synthesis of Liposome Nanoparticles

100 nm liposomes were developed using common mechanical dispersion methods previously established in our lab (27, 28). Briefly, a lipid composition of DPPC, DSPE, cholesterol and DSPE-PEG (2000)-NH2 was dissolved in ethanol in a 52:3:40:5 molar ratio. To formulate the 100 nm liposomes, lipid sheets formed in ethanol were hydrated with PBS at 60oC followed by extrusion in a Lipex Biomembranes Extruder (Northern Lipids, Vancouver, Canada) to reach the 100 nm size. For fluorescence imaging studies, an Alexa-647 fluorophore was directly conjugated to the DSPE lipid prior to lipid hydration via NHS chemistry in organic conditions. Sulfo-SMCC chemistry was also used for the conjugation of the liposome to an N-terminal cysteine added to SBK2 for the generation of the liposome nanoparticles (27, 28).

Visualization of PTPμ-targeted Liposome Nanoparticles

Live mice bearing either pediatric SJ-GBM2 or adult CNS-1 intracranial glioma tumors were injected via lateral tail vein using previously described methods (6) with Alexa Fluor 647-loaded-SBK2-liposomal nanoparticles. After a 2 h interval for clearance of unbound nanoparticles, the animals were sacrificed, and brains were excised for ex vivo optical imaging and histology.

Quantitative T2 Magnetic Resonance Imaging

The MRI studies were performed using a Bruker Biospec 7.0T preclinical MRI scanner (Bruker Corp., Billerica, MA, USA) with a 35 mm inner diameter mouse radiofrequency (RF) coil. Mice bearing SJ-GBM2 cells were scanned from 14–21 days post tumor cell implantation, and U-87 MG orthotopic brain tumors were scanned 8 days post tumor cell implantation using a conventional T2 MRI mapping acquisition.

Iron oxide nanoparticle injected animals bearing U-87 MG tumors were imaged live for MRI. Tumor bearing mice were catheterized prior to the imaging study. Polyurethane tubing (0.014”ID x 0.033” OD) (SAI Infusion Technologies, Lake Villa, IL) was connected to a 1 mL syringe pre-loaded with nanoparticles at a dose of 20 mg Fe/kg body weight in 1x PBS solution. After mice were anesthetized with a 2% isoflurane-oxygen mixture in an induction chamber, tail veins were catheterized using a 26-gauge veterinary catheter, and connected to the pre-loaded tubing described above. The animals were moved into the magnet in the prone position and kept under inhalation anesthesia with 1.5% isoflurane-oxygen via a nose cone. A respiratory sensor connected to a monitoring system (SA Instruments, Stony Brook, NY) was placed on the back of the animal to monitor rate and depth of respiration. Body temperature was maintained at 35 ± 2 °C by blowing warm air into the magnet through a feedback control system.

For each mouse, T2-weighted MRI images were obtained using a rapid acquisition with relaxation enhancement (RARE) sequence (TR/TE = 3000 ms/24 ms, resolution = 0.0117 × 0.0117 cm/pixel, field of view = 30 × 30 mm, and one signal average, slice thickness of 0.70 mm) to select the appropriate imaging slices for the T2 relaxation time mapping acquisition. For quantitative T2 mapping, multiple high resolution T2-weighted MRI image sets were acquired over the entire mouse brain using repeated RARE MRI acquisitions with varying echo times of 16, 40, 60, and 80 ms (repetition time = 4500 ms, resolution = 0.0117 × 0.0117 cm FOV = 30 × 30 mm, slice thickness = 0.7 mm, matrix = 256 × 256, 1 signal average). The total acquisition time for a set of 4 T2-weighted MRI scans was approximately 30 min (i.e., 1 set of T2 maps every 30 min). After an initial set of images, the agent was injected and the T2 mapping procedure was repeated every 30 min for 90 min post-injection. The MRI data for each mouse were imported into Matlab (The Mathworks, Natick, MA) and T2 maps were calculated for each mouse using established monoexponential relaxation models (29).

Evaluation of Contrast Enhancement in Orthotopic Xenograft Mouse Glioma Models

Mean T2 relaxation time values were obtained for each tumor at each successive imaging time point using a region of interest (ROI) analysis. For each mouse, an ROI was drawn around the tumor using the T2 relaxation time map generated at the first post-injection timepoint when tumor enhancement was greatest. A second ROI was selected in the contralateral side of the brain for comparison. Both ROIs were then applied to all of the pre-contrast and post-contrast T2 maps for each mouse. The percent change in tumor R2 = 1/T2 from baseline (precontrast) was calculated for each mouse at each imaging timepoint.

Ex vivo Imaging of Brain Tumors

Ex vivo imaging was performed 2 h after injection of the nanoparticles to allow for clearance of unbound nanoparticles, the animals were sacrificed, and brains were excised for imaging with the Maestro™ FLEX In Vivo Imaging System (Cambridge Research & Instrumentation (CRi), Woburn, MA) as previously described (10). Excised whole brains were imaged using filters appropriate for GFP (tumor cells) as described (10) and Alexa Fluor 647 (nanoparticle).

Ex Vivo Iron Quantification in Brain Tumors

Brain tumor-bearing mice (8 days post-tumor inoculation) were injected intravenously with iron oxide nanochain particles at a dose of 20 mg Fe/kg and sacrificed 2 h post-nanoparticle injection. The concentration of nanochains in tissue was determined by direct quantification of iron ex vivo. Briefly, mice were transcardially perfused with heparinized PBS following sacrifice. Brain-tumor bearing tissue was removed, dried and dissolved in aqua regia, a 1:4 volumetric ratio of nitric acid to hydrochloric acid. Tissues were digested for 48 h while stirring then diluted in deionized water and centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 20 min. The supernatant was collected and passed through a 0.45 μm syringe filter. The iron concentration was directly measured using a Two Varian FS220 Atomic Absorption spectrometer (Department of Chemistry, Case Western Reserve University). Mean (+/− SD) was obtained from n = 4 for both PTPμ-targeted and untargeted nanochains.

Histology

Imaging experiments were performed 14–21 days post-tumor cell implantation for SJ-GBM2 cells, 8 days for U-87 MG and 8–9 days for CNS-1 cells to allow for optimal tumor growth, before sacrifice. For cryo-sectioning, brain tissue was harvested. Tissues were placed in 30% sucrose for 48 h followed by embedding in Optimal Cutting Temperature (OCT) medium at −80oC for an additional 48 h prior to cryo-sectioning (5, 6).

To identify the vasculature in tissue sections, an anti-CD31 primary antibody (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) was used followed by a secondary antibody tagged with Alexa Fluor 568 for fluorescent imaging. Sections were counterstained with DAPI nuclear stain or with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and mounted with Ecomount (Biocare, Pacheco, CA, USA) and imaged. GFP-infected tumors cells were detected using the GFP marker. Tissue sections were imaged at 10x and 20x using a Zeiss Axio Observer Z1 motorized inverted fluorescent microscope. Larger images were constructed using the Axio Vision software’s automatic Mosaic tiling feature. Iron oxide nanochain particles were detected using a Prussian Blue stain as previously described (26) and imaged under brightfield.

Paraffin sections were also generated for histochemistry. Brain tissue was harvested, fixed in formalin and embedded in paraffin.

Cryo-imaging of tumor tissue

Five brains for the SJ-GBM2 cell type were analyzed using the CryoViz™ (BioInVision Inc., Mayfield Village, OH) cryo-imaging system and software. The OCT-embedded tissues were sectioned at 10–20 μm thickness. Alternate sections were imaged with an in-plane pixel size of 10.2 μm with brightfield or fluorescence illumination. Methodologies for segmentation and visualization post imaging have been described elsewhere (5, 6). Three-dimensional volumes of tumor were rendered using Amira software (Visual Imaging, San Diego, CA). Pseudo-colors were chosen for best contrast: green (main tumor), red (vasculature), yellow (migrating cells) and gray (white matter tracts).

Results

In vivo imaging of PTPμ-targeted nanoparticles in intracranial tumors

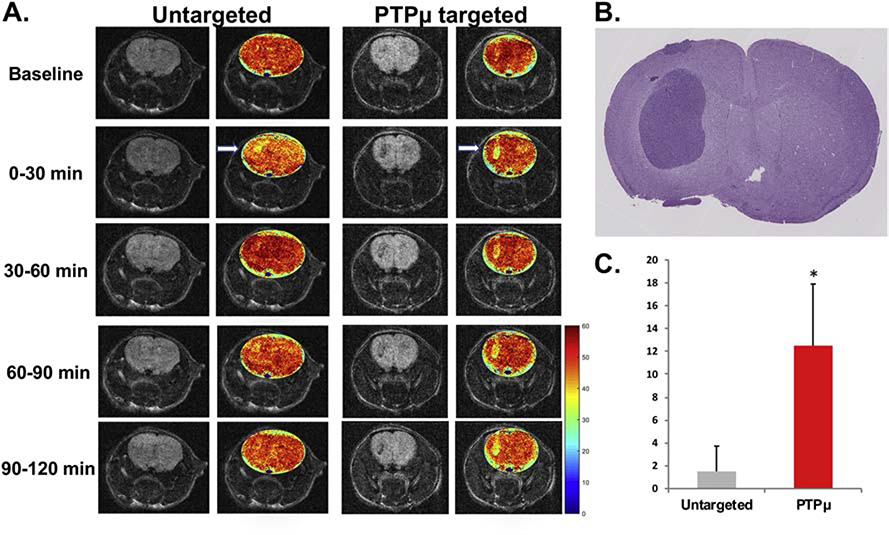

We developed nanochains that target the vascular bed of tumors (Figure 1) and can be used as T2 weighted contrast agents in MRI because of the iron oxide content. To definitively demonstrate that the PTPμ-targeted nanoparticle can label tumors in live animals we analyzed the presence of the nanochain using MRI. Mice with 8 d U-87 MG intracranial tumors were examined using T2-weighted and T2 mapping MRI methods to detect the PTPμ-targeted and untargeted nanochains. For this approach, U-87 MG intracranial tumors were ideal because of the large tumor mass observed at this time point (5) with minimal endogenous tumor contrast at baseline from iron in blood (Figure 2, A). Quantitative T2 mapping was used to directly compare the T2 signal induced by PTPμ-targeted or untargeted nanoparticles in both tumor-bearing and normal brain tissue over time (Figure 2). The PTPμ-targeted nanochains highlighted the intracranial tumor within 30 min, with a high level of contrast remaining for up to 120 min in contrast to untargeted nanochains that only highlighted the tumor during the 0–30 min time frame before rapidly declining to baseline levels (Figure 2, A). A histological section of a representative U-87 MG tumor is shown for reference (Figure 2, B). As a quantitative comparison, the percent change in R2 = 1/T2 was significantly greater in intracranial tumors labeled with the PTPμ-targeted nanochains compared to the untargeted nanochains, indicative of increased tumoral iron accumulation for the PTPμ-targeted nanochains (Figure 2, C, p=0.035). These data show the sustained binding of the PTPμ-targeted nanochains for up to 2 h.

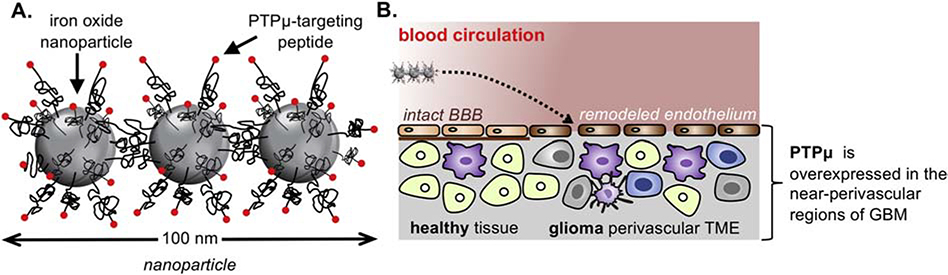

Figure 1.

Illustration of the nanochain particle and its therapeutic effect on brain tumors. (A) Schematic of a linear nanochain particle composed of three iron oxide (IO) nanospheres decorated with the PTPμ-targeted agent. (B) Illustration of the successful delivery of drugs to perivascular tumor microenvironment (TME) via vascular targeting of the PTPμ-targeted nanochain.

Figure 2.

The PTPμ-targeted nanochain shows in vivo binding to U-87 MG intracranial tumors and T2-weighted contrast enhancement. (A) Representative T2 weighted 2D images of U-87 MG orthotopic tumors before (Baseline) and during 30 min increments up to 120 min after intravenous injection of untargeted nanochain or PTPμ-targeted nanochain (n= 4/condition) with pseudo-colored T2 relaxation time map overlays to show contrast uptake. White arrow indicates tumor. Color coded scale bar indicates T2 relaxation time in milliseconds. (B) H & E stained histological section from a representative U-87 MG tumor is shown. (C) Quantification of change in T2 relaxation time (R2 = 1/T2) of U-87 MG intracranial tumor following intravenous administration of the PTPμ-targeted or untargeted iron nanochain (n = 4/condition]. Data shown represent normalized mean percent change in R2 +/− SEM (R2 = 1/T2). Asterisk represents statistical significance, p-value = 0.035. Note the increased percent change in R2 for tumors following administration of the PTPμ-targeted contrast agent.

PTPμ-targeted nanoparticle labeling of adult intracranial GBM tumors

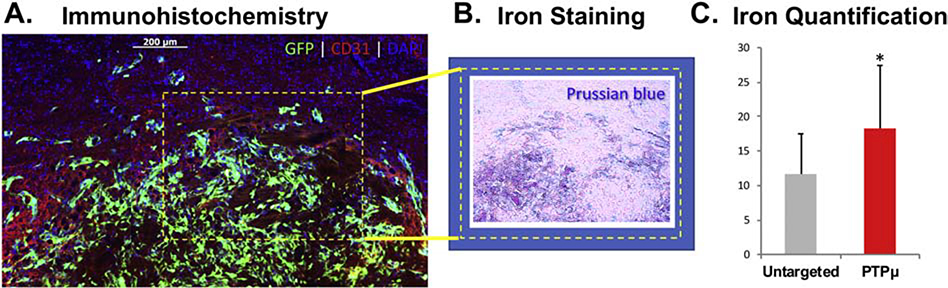

Next, we examined the ability of these nanochains to target more invasive tumors such as CNS-1 tumors. Based on the data presented in Figure 2, PTPμ-targeted or untargeted nanoparticles were injected and allowed to circulate for 2 h in mice with 8 d GFP-labeled CNS-1 intracranial tumors before analysis. Serial sections were used to identify and compare the location of nanoparticles in relation to the GFP-expressing tumor cells and the CD31-positive endothelial cells in the tumor microenvironment, along with Prussian-blue staining to confirm the presence of the iron oxide-containing nanoparticles. We observed co-localization of GFP labeled tumor cells with CD31 positive endothelial cells (Figure 3, A), and Prussian blue staining in the same region (Figure 3, B). In addition, tumors were analyzed for the presence of iron using atomic absorption spectroscopy. Significantly more iron was detected in CNS-1 tumors from mice injected with the PTPμ-targeted nanoparticles compared to those injected with untargeted nanoparticles (Figure 3, C, p=0.027).

Figure 3.

Nanochain labeling of CNS-1 xenografted brain tumors with iron staining and quantification. (A) Sections from mouse brains containing xenografts of GFP-expressing CNS-1 cells treated with the PTPμ-targeted nanochains indicate the high level of colocalization of the GFP-expressing cells with immunohistochemically labeled blood vessels (CD31) and nuclei (DAPI). (B) Prussian blue staining of an adjacent section demonstrates the presence of the iron-oxide containing nanochains in the vicinity of the tumor cells. (C) Iron amounts detected by atomic absorption spectroscopy after 2 h in the brains of mice administered untargeted or PTPμ-targeted nanochains. Significantly more iron accumulated in the brains of mice treated with PTPμ-targeted nanochains compared to untargeted nanochains [n = 4 mice per condition]. Data shown represent mean Fe mass/tissue mass μg/g +/− SEM. Asterisk represents statistical significance, p-value = 0.027.

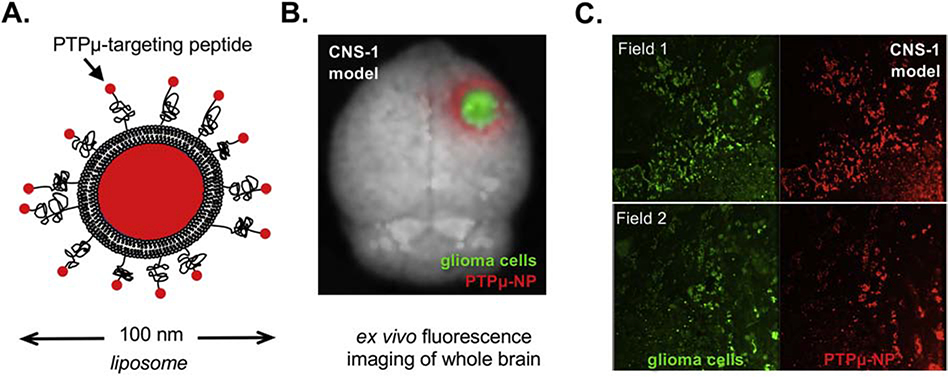

Based on the design of the nanoparticle and the expression of PTPμ in the tumor microenvironment and along vascular beds, we hypothesized that the PTPμ-targeted nanoparticles would highlight the perivascular tumor microenvironment (Figure 1). A PTPμ-targeted nanoparticle adapted to include a liposome capable of carrying a therapeutic drug cargo was tested for its ability to target gliomas (Figure 4, A). Ex vivo whole brain fluorescence imaging was used to identify the GFP positive tumor cells in conjunction with Alexa 647-loaded PTPμ-targeted nanoparticles (Figure 4, B). The fluorescent liposomal Alexa 647 is localized around the GFP tumor margins as visible in the intracranial CNS-1 tumors (Figure 4, B). Histological sections of the CNS-1 tumors demonstrate an overlap between the GFP-labeled glioma cells and the PTPμ-targeted nanoparticles (Figure 4, C).

Figure 4.

PTPμ-targeted nanoparticles label adult glioma tumor cells. (A) Schematic of PTPμ-targeted nanoparticle incorporating liposomes. (B) Mouse brains containing xenografts of GFP-expressing CNS-1 cells were imaged following in vivo labeling with the PTPμ-targeted liposome nanoparticle. The PTPμ-targeted nanoparticle (red) completely overlaps the GFP-expressing CNS-1 cells (green). (C) Sections of CNS-1 xenografted brains from two different fields of view (field 1 and field 2) for the same animal show overlap of GFP and fluorescent nanoparticle signal.

Growth characterization of pediatric GBM orthotopic xenograft model

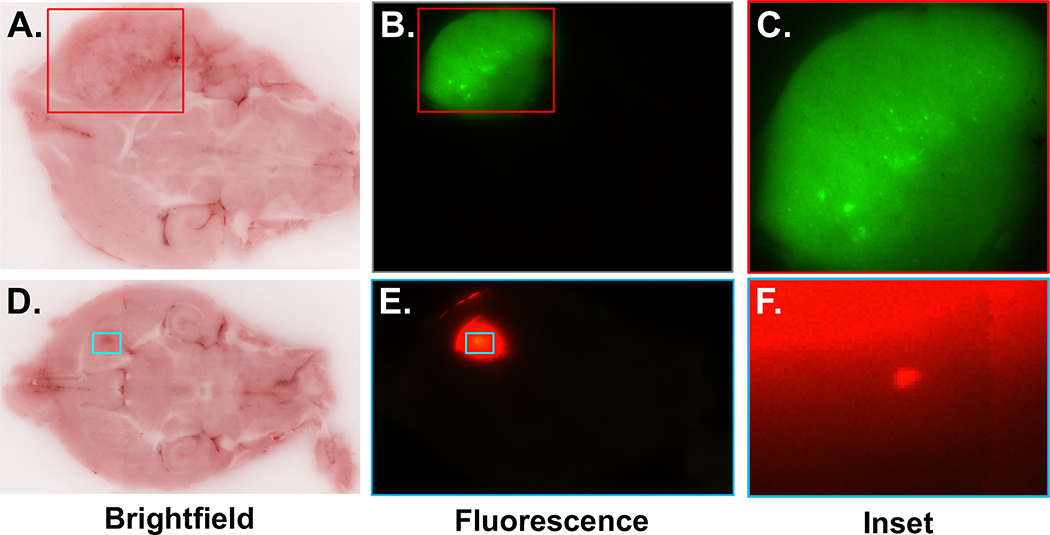

To test the ability of PTPμ-targeted nanoparticles to highlight glioma cells in pediatric GBM models, we first evaluated the growth characteristics of the pediatric SJ-GBM2 cell line after implanting the immortalized pediatric glioma cells intracranially into athymic mice. Using cryo-imaging and three-dimensional reconstructions of the brain we characterized SJ-GBM2 tumors 14 and 21 days after implantation. Cryo-image analysis uses bright-field images of the block face for overall brain anatomy and captures co-registered fluorescent images of the same field-of-view to detect the GFP-expressing or m-Cherry expressing SJ-GBM2 cells (Figure 5) (30). At 21 days, both the GFP and m-Cherry expressing SJ-GBM2 cells formed large tumors (green and red, respectively) in this tumor model as visualized in the intact brains (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Mouse brains containing xenografts of GFP-expressing SJ-GBM2 cells were cryo-imaged. (A) The brightfield block face image from one section is shown in panel. (B) A fluorescent image of the block face is shown. (C) The region marked by the rectangle (inset) in panel B is shown magnified. (D-F) Similar views are shown for a second SJ-GBM2 21-day tumor using cells labeled with m-Cherry.

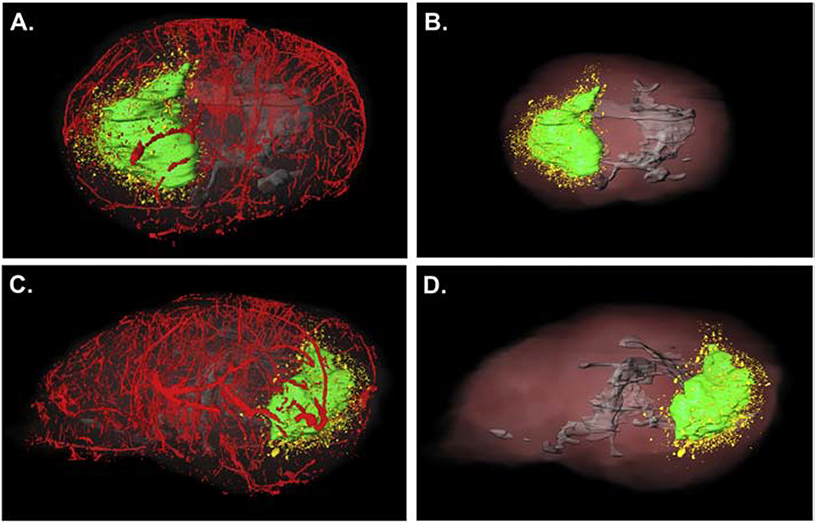

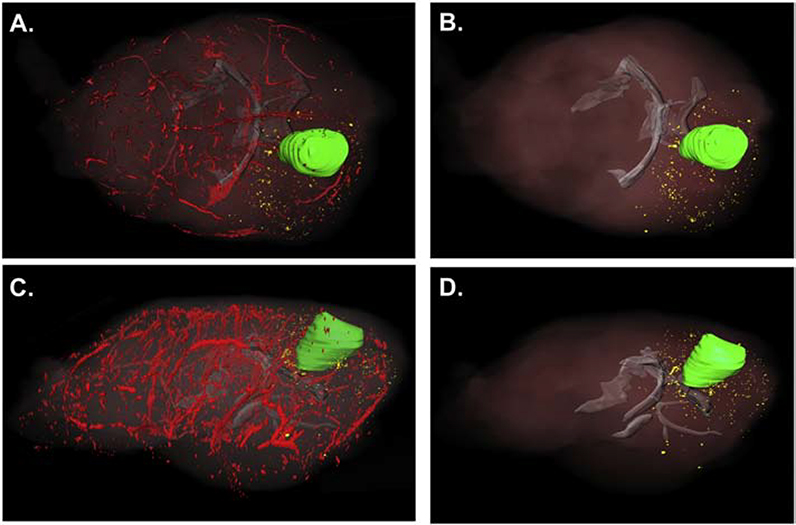

For 3-D analysis, 3-D volumes were created for the vasculature (pseudocolored red), white matter (pseudocolored gray) and the main tumor mass (pseudocolored green). Dispersive glioma cells no longer connected in any dimension to the main tumor were pseudocolored yellow. Multiple specimens were analyzed using this technique, and representative examples are shown. We observed that the SJ-GBM2 cells generated a large tumor mass (represented in green in Figures 6–7), with dispersive cells that migrated away from the main tumor. In Figures 6–7, the results from two different brains show that the dispersive SJ-GBM2 cells grow in close proximity to blood vessels. The SJ-GBM2 cells can also be seen migrating along white matter tracts (Figures 6–7).

Figure 6.

Three-dimensional reconstruction of an SJ-GBM2 tumor indicates large tumor mass with extensive cell invasion. A mouse brain containing xenografts of GFP-expressing SJ-GBM2 cells was cryo-imaged and reconstructed in 3 dimensions to show the main tumor mass (pseudo-colored green), dispersive cells (pseudo-colored yellow), vasculature (pseudocolored red) and white matter tracts (pseudocolored gray). (A) Dorsal view of a tumor indicates highly proliferative main tumor mass with extensive migration away from the main tumor mass. Lateral view of the same tumor is indicated in (C). Three-dimensional reconstruction demonstrates invasion along white matter tracts (shown in gray) of tumor cells (B, dorsal view, and D, lateral view of the same tumor).

Figure 7.

Three-dimensional reconstruction of a different 21-day SJ-GBM2 tumor indicates large tumor mass with extensive cell invasion. Mouse brains containing xenografts of mCherry-expressing SJ-GBM2 cells were cryo-imaged and reconstructed in 3 dimensions to show the main tumor mass (pseudo-colored green), dispersive cells (pseudo-colored yellow), vasculature (pseudocolored red) and white matter tracts (pseudocolored gray). (A) Dorsal view of a tumor indicates highly proliferative main tumor mass with extensive migration away from the main tumor mass. Lateral view of the same tumor is indicated in (C). Three-dimensional reconstruction demonstrates invasion along white matter tracts (shown in gray) of tumor cells (B, D).

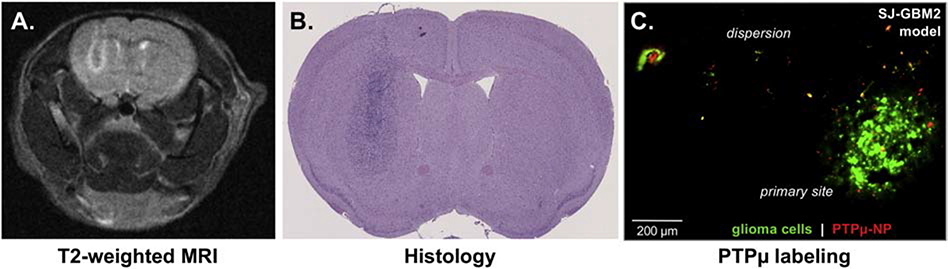

SJ-GBM2 tumors were evaluated using T2-weighted MRI (Figure 8, A), and histologically with H&E (Figure 8, B) to again demonstrate large tumors were created with this pediatric model. Finally, we evaluated the ability of the PTPμ-targeted nanoparticle to label the pediatric GBM cells following injection in vivo. The PTPμ-targeted nanoparticle labeled distinct areas of the tumor margin and individual invasive glioma cells, including some a millimeter away from the main tumor (Figure 8, C).

Figure 8.

Targeting of an orthotopic pediatric GBM model. (A) A non-contrast T2-weighted image of a day 21 SJ-GBM2 tumor. (B) H&E stained section of the same SJ-GBM2 tumor. (C) A histological section from GFP-expressing SJ-GBM2 tumor following in vivo labeling with Alexa Fluor 647-loaded-PTPμ-nanoparticle. The PTPμ-targeted nanoparticles label invasive individual tumor cells outside the main tumor mass. Scale bar = 200 μM.

Discussion

Our results demonstrate that targeting of PTPμ in the tumor perivasculature and tumor microenvironment can rapidly and with a high degree of specificity label adult intracranial tumors in vivo. This is supported by our in vivo studies using MR imaging, ex vivo studies using whole brain fluorescence imaging of the nanoparticle and tumor cells, and histologically in tissue sections and by iron-oxide staining for the nanoparticle.

Appropriate pediatric GBM models are lacking, and development of these models is greatly needed to evaluate new therapeutic approaches. With this goal in mind, we characterized a pediatric model of GBM by placing SJ-GBM2 cells orthotopically into athymic mice. This is particularly important since pediatric glioma is genetically and epigenetically distinct from adult glioma (31). In pediatric GBM, unlike adult GBM, H3F3 K27 and G34 mutations are prevalent along with TP53 mutations while virtually no IDH1 mutations exist except for in a subset of adolescent patients (32–34). Animal models that reflect the distinct genetic characteristics of pediatric GBM are needed. We demonstrate here that the SJ-GBM2 model recapitulates several key features of pediatric GBM growth, specifically its proliferative and infiltrative nature, making it a useful tool for future studies.

Using this model, we further demonstrate that the PTPμ-targeted nanoparticles label individual invasive tumor cells outside the main tumor. These results are consistent with our previous PTPμ-targeted studies using small molecule fluorescent and MRI-based contrast agents. Cumulatively, our data suggest that PTPμ targeting can specifically guide and sensitively deliver theranostic agents to tumor sites in vivo in both pediatric and adult brain tumor models.

The ultimate goal of this research is to deliver a toxic payload to the tumor via a targeted nanoparticle. By combining the iron oxide nanochain and the liposome together into one nanochain-liposome, we can create an agent to deliver on-command, rapid drug release by mechanically disrupting the drug loaded liposome using an external low-power radiofrequency field (RF) (13–19). Application of the RF directly to the site of cancer, where there is significant particle accumulation, facilitates drug delivery directly into the tumor and perivascular regions harboring tumor cells, allowing for penetration even at invasive sites. By combining the on-command drug release capability with molecular targeting to proteolyzed PTPμ, both adult and pediatric glioma could be more effectively treated. Proteolysis of cell adhesion molecules (CAMs) is a generalizable mechanism that may be an important step in the loss of contact inhibition observed in cancer (35–37). The development of peptide binding agents to other CAMs and/or RPTPs in addition to those to PTPμ may be another effective means of targeting theranostics to the tumor microenvironment (37).

Acknowledgements

We thank Elizabeth Doolittle for technical assistance with the liposome studies and Cathy Doller from the Visual Sciences Research Center Core for assistance with histology. We also acknowledge the support of the Light Microscopy Imaging Core of the School of Medicine and the technical support of Richard Lee.

Funding: This research was funded by Alex’s Lemonade Stand Foundation, Flashes of Hope, I Care I Cure Childhood Cancer Foundation, Tabitha Yee-May Lou Endowment Fund for Brain Cancer Research, the Alma and Harry Templeton Medical Research Foundation, and the Char and Chuck Fowler Family Foundation. Additional funding and support were obtained from the National Institutes of Health sponsored Case Comprehensive Cancer Center, their Cancer Imaging Program and their cores (P30CA043703), the Visual Sciences Research Center (P30EY11373) as well as the Light Microscopy Imaging Core (S10OD024981). G. C., M.L. were supported by a fellowship from the NIH Interdisciplinary Biomedical Imaging Training Program (T32EB007509) administered by the Department of Biomedical Engineering at Case Western Reserve University.

Abbreviations

- BBB

blood brain barrier

- IO-COOH

carboxylic acid functionalized iron oxide nanoparticles

- CAMs

cell adhesion molecules

- CA-IOs

Citric acid coated iron oxide nanoparticles

- DMF

dimethylformamide

- IO-NH2

functionalized iron oxide nanoparticles

- GBM

glioblastoma

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- H&E

hematoxylin and eosin

- IO

iron oxide

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- OCT

Optimal Cutting Temperature medium

- RF

radiofrequency

- RARE

rapid acquisition with relaxation enhancement sequence

- PTPmu or PTPμ

Receptor protein tyrosine phosphatase mu

- ROI

region of interest

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: B. Scott, M. Gargesha, and D. Roy are employees of BioInVision Inc. No other conflicts of interest exist.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ostrom QT, de Blank PM, Kruchko C, Petersen CM, Liao P, Finlay JL, et al. Alex’s Lemonade Stand Foundation Infant and Childhood Primary Brain and Central Nervous System Tumors Diagnosed in the United States in 2007–2011. Neuro-Oncology. 2015;16(Suppl 10):x1–x36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pollack IF, Agnihotri S, Broniscer A. Childhood brain tumors: current management, biological insights, and future directions. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2019;23(3):261–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, Weller M, Fisher B, Taphoorn MJ, et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(10):987–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Finlay JL, Boyett JM, Yates AJ, Wisoff JH, Milstein JM, Geyer JR, et al. Randomized phase III trial in childhood high-grade astrocytoma comparing vincristine, lomustine, and prednisone with the eight-drugs-in-1-day regimen. Childrens Cancer Group. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13(1):112–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burden-Gulley SM, Qutaish MQ, Sullivant KE, Lu H, Wang J, Craig SE, et al. Novel cryo-imaging of the glioma tumor microenvironment reveals migration and dispersal pathways in vivid three-dimensional detail. Cancer Res. 2011;71(17):5932–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burden-Gulley SM, Qutaish MQ, Sullivant KE, Tan M, Craig SE, Basilion JP, et al. Single cell molecular recognition of migrating and invading tumor cells using a targeted fluorescent probe to receptor PTPmu. Int J Cancer. 2013;132(7):1624–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burden-Gulley SM, Zhou Z, Craig SE, Lu ZR, Brady-Kalnay SM. Molecular Magnetic Resonance Imaging of Tumors with a PTPmu Targeted Contrast Agent. Transl Oncol 2013;6(3):329–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johansen ML, Gao Y, Hutnick MA, Craig SEL, Pokorski JK, Flask CA, et al. Quantitative Molecular Imaging with a Single Gd-Based Contrast Agent Reveals Specific Tumor Binding and Retention in Vivo. Anal Chem. 2017;89(11):5932–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johansen ML, Vincent J, Gittleman H, Craig SE, Couce M, Sloan AE, et al. A PTPmu Biomarker is Associated with Increased Survival in Gliomas. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2019;20(10). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burden-Gulley SM, Gates TJ, Burgoyne AM, Cutter JL, Lodowski DT, Robinson S, et al. A novel molecular diagnostic of glioblastomas: detection of an extracellular fragment of protein tyrosine phosphatase mu. Neoplasia. 2010;12(4):305–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burgoyne AM, Phillips-Mason PJ, Burden-Gulley SM, Robinson S, Sloan AE, Miller RH, et al. Proteolytic cleavage of protein tyrosine phosphatase mu regulates glioblastoma cell migration. Cancer Res. 2009;69(17):6960–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Phillips-Mason PJ, Craig SE, Brady-Kalnay SM. A protease storm cleaves a cell-cell adhesion molecule in cancer: multiple proteases converge to regulate PTPmu in glioma cells. J Cell Biochem. 2014;115(9):1609–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peiris PM, Bauer L, Toy R, Tran E, Pansky J, Doolittle E, et al. Enhanced Delivery of Chemotherapy to Tumors Using a Multicomponent Nanochain with Radio-Frequency-Tunable Drug Release. ACS Nano. 2012;6(5):4157–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peiris PM, Schmidt E, Calabrese M, Karathanasis E. Assembly of linear nano-chains from iron oxide nanospheres with asymmetric surface chemistry. PLoS One. 2011;6(1):e15927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peiris PM, Abramowski A, McGinnity J, Doolittle E, Toy R, Gopalakrishnan R, et al. Treatment of Invasive Brain Tumors Using a Chain-like Nanoparticle. Cancer Res. 2015;75(7):1356–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peiris PM, Tam M, Vicente P, Abramowski A, Toy R, Bauer L, et al. On-command drug release from nanochains inhibits growth of breast tumors. Pharm Res. 2014;31(6):1460–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peiris PM, Toy R, Abramowski A, Vicente P, Tucci S, Bauer L, et al. Treatment of cancer micrometastasis using a multicomponent chain-like nanoparticle. J Control Release. 2014;173:51–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peiris PM, Toy R, Doolittle E, Pansky J, Abramowski A, Tam M, et al. Imaging metastasis using an integrin-targeting chain-shaped nanoparticle. ACS Nano. 2012;6(10):8783–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karathanasis E, Ghaghada KB. Crossing the barrier: treatment of brain tumors using nanochain particles. Wiley interdisciplinary reviews Nanomedicine and nanobiotechnology. 2016;8(5):678–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Atukorale PU, Covarrubias G, Bauer L, Karathanasis E. Vascular targeting of nanoparticles for molecular imaging of diseased endothelium. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2017;113:141–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perera VS, Covarrubias G, Lorkowski M, Atukorale P, Rao A, Raghunathan S, et al. One-pot synthesis of nanochain particles for targeting brain tumors. Nanoscale. 2017;9(27):9659–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kruse CA, Molleston MC, Parks EP, Schiltz PM, Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK, Hickey WF. A rat glioma model, CNS-1, with invasive characteristics similar to those of human gliomas: a comparison to 9L gliosarcoma. J Neurooncol. 1994;22(3):191–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kang MH, Smith MA, Morton CL, Keshelava N, Houghton PJ, Reynolds CP. National Cancer Institute pediatric preclinical testing program: model description for in vitro cytotoxicity testing. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;56(2):239–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Houghton PJ, Cheshire PJ, Hallman JD 2nd, Lutz L, Friedman HS, Danks MK, et al. Efficacy of topoisomerase I inhibitors, topotecan and irinotecan, administered at low dose levels in protracted schedules to mice bearing xenografts of human tumors. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1995;36(5):393–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tyagi M, Karn J. CBF-1 promotes transcriptional silencing during the establishment of HIV-1 latency. EMBO J. 2007;26(24):4985–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Covarrubias G, Cha A, Rahmy A, Lorkowski M, Perera V, Erokwu BO, et al. Imaging breast cancer using a dual-ligand nanochain particle. PLoS One. 2018;13(10):e0204296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Covarrubias G, He F, Raghunathan S, Turan O, Peiris PM, Schiemann WP, et al. Effective treatment of cancer metastasis using a dual-ligand nanoparticle. PLoS One. 2019;14(7):e0220474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peiris PM, He F, Covarrubias G, Raghunathan S, Turan O, Lorkowski M, et al. Precise targeting of cancer metastasis using multi-ligand nanoparticles incorporating four different ligands. Nanoscale. 2018;10(15):6861–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jakob PM, Hillenbrand CM, Wang T, Schultz G, Hahn D, Haase A. Rapid quantitative lung (1)H T(1) mapping. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2001;14(6):795–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qutaish MQ, Sullivant KE, Burden-Gulley SM, Lu H, Roy D, Wang J, et al. Cryo-image analysis of tumor cell migration, invasion, and dispersal in a mouse xenograft model of human glioblastoma multiforme. Mol Imaging Biol 2012;14(5):572–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fangusaro J Pediatric High Grade Glioma: a Review and Update on Tumor Clinical Characteristics and Biology. Frontiers in Oncology. 2012;2:105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pollack IF, Hamilton RL, Sobol RW, Nikiforova MN, Lyons-Weiler MA, LaFramboise WA, et al. IDH1 mutations are common in malignant gliomas arising in adolescents: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Childs Nerv Syst. 2011;27(1):87–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sturm D, Witt H, Hovestadt V, Khuong-Quang DA, Jones DT, Konermann C, et al. Hotspot mutations in H3F3A and IDH1 define distinct epigenetic and biological subgroups of glioblastoma. Cancer Cell. 2012;22(4):425–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schwartzentruber J, Korshunov A, Liu XY, Jones DT, Pfaff E, Jacob K, et al. Driver mutations in histone H3.3 and chromatin remodelling genes in paediatric glioblastoma. Nature. 2012;482(7384):226–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Craig SE, Brady-Kalnay SM. Cancer cells cut homophilic cell adhesion molecules and run. Cancer Res. 2011;71(2):303–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Craig SE, Brady-Kalnay SM. Regulation of development and cancer by the R2B subfamily of RPTPs and the implications of proteolysis. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2015;37:108–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Craig SE, Brady-Kalnay SM. Tumor-derived extracellular fragments of receptor protein tyrosine phosphatases (RPTPs) as cancer molecular diagnostic tools. Anticancer Agents Med Chem 2011;11(1):133–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]