Abstract

Mitochondria serve a vital role in cellular homeostasis as they regulate cell proliferation and death pathways, which are attributed to mitochondrial bioenergetics, free radicals and metabolism. Alterations in mitochondrial functions have been reported in various diseases, including cancer. Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most common metastatic cancer types with high mortality rates. Although mitochondrial oxidative stress has been associated with CRC, its specific mechanism and contribution to metastatic progression remain poorly understood. Therefore, the aims of the present study were to investigate the role of mitochondria in CRC cells with low and high metastatic potential and to evaluate the contribution of mitochondrial respiratory chain (RC) complexes in oncogenic signaling pathways. The present results demonstrated that cell lines with low metastatic potential were resistant to mitochondrial complex I (C-I)-mediated oxidative stress, and had C-I inhibition with impaired mitochondrial functions. These adaptations enabled cells to cope with higher oxidative stress. Conversely, cells with high metastatic potential demonstrated functional C-I with improved mitochondrial function due to coordinated upregulation of mitochondrial biogenesis and metabolic reprogramming. Pharmacological inhibition of C-I in high metastatic cells resulted in increased sensitivity to cell death and decreased metastatic signaling. The present findings identified the differential regulation of mitochondrial functions in CRC cells, based on CRC metastatic potential. Specifically, it was suggested that a functional C-I is required for high metastatic features of cancer cells, and the role of C-I could be further examined as a potential target in the development of novel therapies for diagnosing high metastatic cancer types.

Keywords: mitochondria, mitochondrial complex I, oxidative stress, colorectal cancer, metastasis, apoptosis

Introduction

Mitochondria are the bioenergetic and metabolic hubs of the cell, and are harbor sites of free radical generation (1). Free radicals can regulate cellular signaling pathways and contribute to cellular proliferation and death mechanisms (2). Changes in mitochondria, such as respiration impairments, oxidative stress and metabolic alterations, affect these signaling pathways and are associated with various diseases, including cancer (3). In cancer, mitochondrial contribution is variable and dependent on the type of cancer, genetic factors, tissue origin and other unknown factors (4). In mitochondria, respiratory chain (RC) complexes are large multi-subunit inner membrane structures that facilitate electron transfer, ATP production via oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) and reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation. Since ROS levels act as signaling molecules to activate cellular pathways, excessive ROS levels can cause oxidative damage and contribute to oncogenic signaling for cancer development (5). Previous studies have reported that oxidative stress is a mitigating factor in metastasis, and the threshold of oxidative stress is crucial in enhancing or decreasing metastatic potential (6,7). From the metabolic perspective, while cancer cells are highly glycolytic (Warburg effect), it is now evident that reprogramming of metabolic pathways serves a critical role in proliferation of cancer cells (8). However, the contribution and role of RC in metabolic reprogramming in cancer progression are yet to be fully elucidated.

Among the five types of mitochondrial RC complexes, mitochondrial complex I (C-I; NADH: Ubiquinone oxidoreductase) is the largest and most prolific ROS producing site, and has been implicated in cancer progression (9–14). C-I alterations are involved in mitochondrial dysfunction in different cancer types, including lung, liver, prostrate breast and colon cancer (14). While the specific role of C-I in promoting or suppressing tumors remains unknown, it largely depends on cancer types and the experimental system (15). Since metastatic processes involve cell migration, invasion and proliferation at distal sites, C-I-mediated changes could serve an important role in regulating metastatic signaling (16). Hence, it is imperative to understand how different RC complexes regulate proliferative pathways and contribute to these pathways at different stages of neoplastic transformations. Such studies are clinically relevant in targeting specific RC complexes, as well as combining therapeutic approaches to specific metastatic conditions and tumor types.

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the fourth most common type of cancer with high incidence (6.1%) and mortality (5.8%) rates across all cancers worldwide according to global cancer statistics 2018 (17). Although mitochondrial alterations have been associated with CRC metastasis, the functionality of different RC complexes, contribution of oxidative stress and the role of metastatic signaling in CRC remain unknown. Therefore, it is clinically relevant to identify therapeutic targets.

The current study aimed to identify specific changes in RC complexes, as well as their contribution to mitochondrial dysfunctions and metabolism in metastatic CRC cells. Using CRC cells with low and high metastatic potentials, the present study aimed to investigate the effect of RC inhibition on cell survival, mitochondrial functions and contribution to metastatic signaling pathways.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

Established CRC cell lines (low metastatic, HT-29 and HCT-15; high metastatic, HCT-116 and COLO-205) were used in the current study. These authenticated cell lines were purchased from the national repository at National Centre for Cell Sciences Pune, and early passage cultures were used for performing all the experiments. Cell culture reagents, including growth media, FBS and antibiotics were purchased from HiMedia Laboratories LLC. HT-29, HCT-15 and COLO-205 cells were maintained in RPMI-1640 medium, while HCT-116 cells were maintained in McCoy's growth medium. The medium was supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% antibiotic-antimycotic solution, and cells were grown at 37°C with 95% humidity in incubator maintaining 5% CO2.

In vitro tumorigenesis assay

Tumorigenic potential was determined using soft agar colony-forming assay (10). Briefly, a bottom layer containing 0.4% agar, 1X growth media and 10% FBS was prepared in 60-mm culture dishes. An overlay media, containing 1,000 cells in 0.3% agarose, 1X growth media and 10% FBS, was added to each plate in triplicate. The cells were incubated for 3–4 weeks at 37°C in a humidified CO2 incubator and given fresh media every 4th day. Colony formation was observed after 3 weeks of plating; bright field images (at 10× magnification) were captured using the CMOS camera application in ChemiDoc Imaging system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). Clones were counted and quantified as relative colony-forming units between CRC cells.

Transwell cell migration assay

The migratory capacity of metastatic cells was measured by their ability to invade through extracellular matrix (ECM), following a previously described protocol (12). Cells (~5,000) were plated in triplicates in 8-µm pore-sized cell culture inserts (BD Labware; BD Biosciences) and supplemented with media without serum. These cell inserts were positioned in 12-well plates containing media with 10% FBS, followed by incubation for 12–16 h at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. Migration of cells was visualized by staining the cells with Hema 3 staining following manufacturer's instructions (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and images were captured at 100× magnification using a microscope (Nikon Eclipse TE2000; Nikon Corporation). Total number of stained and migrated cells were counted, and calculated as relative migration units between CRC cells.

Cell viability measurements

A total of ~5×105 cells/ml were seeded in triplicates in 12-well plates in culture medium and incubated at 37°C for 24 h. Cells were treated with different agents at multiple concentrations [rotenone, 0.05–200 µM; paraquat, 0.025–20 mM; antimycin, 0.25–20 µM; oligomycin, 5–100 µM; H2O2, 0.025–2 mM; N-acetyl cysteine (NAC), 5 mM; all purchased from Sigma-Aldrich) followed by 24 h incubation at 37°C. Cell viability assay was performed by staining the cells with trypan blue (0.4%) for 3 min at room temperature and counting by haemocytometer. Bright field images of cells were captured at ×100 magnification.

Blue native gel electrophoresis and C-I activity assay

Blue native poly acrylamide gel electrophoresis (BN-PAGE) was performed following optimized protocol as published previously (18). Cultured cells were harvested and centrifuged (at 100 × g for 5 min at room temperature), and the pellet was re-suspended in 0.5 ml ice-cold HB buffer (50 mM KPO4; pH: 7.4; 1 mM EDTA; 2.5% glycerol; 250 mM sucrose) containing protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich). Cells were disrupted using a dounce homogenizer at 4°C for 5 min and enriched for mitochondria via differential centrifugation at 4°C (initial spin at 500 × g for 5 min where the supernatant was removed, and respun to pellet the mitochondria at 10,000 × g for 5 min). The mitochondrial pellet was washed twice and re-suspended in a final protein concentration of 2–5 mg/ml in HB buffer. Optimal solubility of mitochondrial super-complexes was achieved using optimized concentration of 8 mg digitonin/mg of protein in HB buffer without EDTA. The samples were incubated on ice for 20 min in a coomassie blue solution (5% coomassie blue G-250 in 750 mM 6-aminocaproic acid) to a ratio of 1:30 v/v. The supernatant (total of 80 µg protein) was then run on a 3–12% Native PAGE (Novex Bis-Tris gel) for 4 h at 80 V and 4°C in the buffer provided by the supplier (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), to resolve the mitochondrial complexes, and the resulting gels were stained with Bio-safe coomassie R-250 (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.) for 30 min at room temperature.

In parallel, a similarly run gel without staining was used for the gel activity assay for C-I following a previously published protocol (19). Both the stained and activity gels were scanned and analyzed using ImageJ software (version 1.8.0; National Institutes of Health), to determine the relative band intensities, which were normalized with total mitochondrial protein levels and calculated as fold change relative to HT-29 bands. Equal loading (80 µg) of mitochondrial protein was confirmed by running a similar aliquot of mitochondrial extract on a separate 12% denaturing gel and western blotting with mitochondrial voltage-dependent anion channel protein (cat. no 4661, Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.).

Western blotting

Protein samples were extracted using RIPA buffer (Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.) and the concentration of protein was determined using a BCA Protein assay kit (Pierce; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The samples (30 µg) were electrophoresed on 12% SDS-PAGE at 120 V for 2 h. The resolved proteins were transferred on PVDF membrane and blocked with 5% non-fat dry milk in TBS-0.5% Tween-20 (TBS-T) for 1 h at room temperature. The membrane was incubated with primary antibodies at dilution of 1:1,000, overnight at 4°C following manufacturer's instructions (Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.). The antibodies against pAKT-Thr (308) (cat. no. 13038), p-AKT-Ser (473) (cat. no. 4060), total AKT (cat. no. 4691), Actin (cat. no. 4970), HIF1-α (cat. no. 36169), cMyc (cat. no. 18583), GAPDH (cat. no. 5174), SOD1 (cat. no. 37385), Beclin-1 (cat. no. 3495) and ATG5 (cat. no. 12994) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. The membrane was washed thrice with TBS-T and then incubated with anti-rabbit IgG horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (cat. no. 7074; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.) at 1:5,000 dilution. Specific bands were detected using super signal west pico-chemi-luminescent substrate kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and imaged on a ChemiDoc Imaging system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). Experiments were performed twice or thrice, and one of the representative images was analyzed for densitometry using ImageJ (version 1.8.0; National Institutes of Health).

Mitochondrial functional analysis

Reactive oxygen species measurement

To measure cellular ROS levels, cell-permeant 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (H2-DCFDA) dye was used as per manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Briefly, 1×106 live cells were re-suspended in Hank's buffered salt solution (HBSS) with H2DCFDA (10 µM) and Hoechst-33342 (10 µg/ml), and incubated at 37°C for 15 min. Cells were then washed, centrifuged at 100 × g for 5 min at room temperature and the resulting pellet was re-suspended in PBS. The fluorescence intensity was measured using HT-BioTek fluorescence plate reader at Excitation/Emission (Ex/Em): 495/529 nm for H2DCFDA and 350/497 nm for Hoechst-33342 at 37°C.

To measure mitochondrial superoxide levels, mitochondrial specific superoxide indicator dye MitoSOX™ Red (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) was used. Equal number of cells (1×106) were re-suspended in HBSS buffer with MitoSOX™ Red (5 µM) and Hoechst-33342 (10 µg/ml), and incubated at 37°C for 15 min. Cells were washed, and the fluorescence (MitoSOX™ Red; Ex/Em, 510/580 nm) was measured using HT-BioTek fluorescence plate reader. Relative values for both measurements were calculated after normalizing with Hoechst-33342 fluorescence. All the experiments were performed in triplicates, and the results are presented as relative mean fluorescence intensity.

ATP measurement

Total ATP content was measured using luciferase-based ATP determination kit according to manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). For ATP measurement, 1×106 cells were harvested, centrifuged at 100 × g for 5 min at room temperature and re-suspended in 100 µl buffer (25 mM Tris; pH 7.4; 150 mM EDTA). The re-suspended cells were boiled at 100°C for 5 min, followed by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 5 min at room temperature. The supernatant was collected, added to the luciferin-luciferase mixture and luminescence was measured in BioTek Synergy HT Multi-detection Microplate reader. The ATP concentration was determined using a standard ATP/luminescence curve ranging from 0.001–10 mM ATP, normalized to total protein and calculated as relative fold change between CRC cells.

Mitochondrial Membrane Potential (MMP) measurement

Similar to ATP measurement, 1×106 cells were incubated with 200 nM MMP indicator dye tetra-methyl-rhodamine methyl ester perchlorate (TMRM) for 15 min at 37°C. Cells were washed and counterstained with Hoechst-33342 (10 µg/ml) for 5 min at 37°C. Fluorescence was recorded for TMRM (Ex/Em, 540/575 nm) using a fluorescence plate reader. Relative values for both measurements were calculated after normalizing to Hoechst-33342 fluorescence. All experiments were performed in triplicates, and the results are presented as relative mean fluorescence intensity.

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) copy number measurement

Total DNA was isolated from 1×106 CRC cells using DNeasy kit (Qiagen China Co., Ltd.). A total of 20 ng of DNA was used for quantitative PCR (qPCR) for mtDNA copy number determination using the Fast SYBR Green Master mix (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) on a 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.. The steps were as follows: 95°C For 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 sec and 60°C for 1 min. Quantitation of mtDNA copy number relative to nuclear DNA was done by amplifying mtDNA (human tRNA leucine1, transcription terminator and 5S-like sequence), and nuclear reference gene (18s ribosomal DNA) as previously described (20). The primer sequences were: mtDNA (Human-tRNA leucine 1, transcription terminator and 5S-like sequence), forward: 5′-CACCCAAGAACAGGGTTTGT-3′ and reverse: 5′-TGGCCATGGGTATGTTGTTAA-3′; nDNA (18s ribosomal DNA), forward: 5′-TAGAGGGACAAGTGGCGTTC-3′ and reverse: 5′-CGCTGAGCCAGTCAGTGT-3′. Relative mtDNA copy number was calculated with normalization to the nuclear DNA (18s ribosomal DNA) copy number using 2−ΔΔCq method (21).

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

For gene expression studies, RNA was isolated from 1×106 non-treated cells or treated with rotenone (100 µM)/paraquat (10 mM) for different time points (0, 3, 6 and 12 h), using RNeasy kit (Qiagen China Co., Ltd.). A total of 1 µg RNA was reversed transcribed into cDNA using the QuantiTect Reverse Transcription kit (Qiagen China Co., Ltd.) at 42°C for 15 min, and 95°C for 3 min. Subsequently qPCR was performed using Fast SYBR Green Master mix following similar PCR conditions as aforementioned. The list of primers used for RT-qPCR of the various genes (PGC1-α, TFAM, β-actin, AKT-1, HIF-1α, cMyc, Survivine, SLC2A1, CA-9, VEGF) is presented in Table SI with relevant references (22–25). In addition, qPCR of C-I subunit genes was performed using mtDNA encoded ND-1,-2,-4, −4L and −6 gene primers as reported by Salehi et al (26). Relative gene expression of target genes was normalized to β-actin expression (reference gene) using 2−ΔΔCq method (21).

Statistical analysis

Graphs were prepared and analyzed using GraphPad Prism 5 software (GraphPad Software, Inc.). Data in graphs are presented as the mean ± SEM. Experiments were performed at least thrice with ≥3 replicates for each condition. Morphological images were representative of ≥3 independent experiments with similar results. Significant statistical differences were measured using unpaired Student's t-test or one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's post hoc test for comparisons between treatment and control groups or by Tukey's test for comparisons among multiple groups. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Properties of cell lines

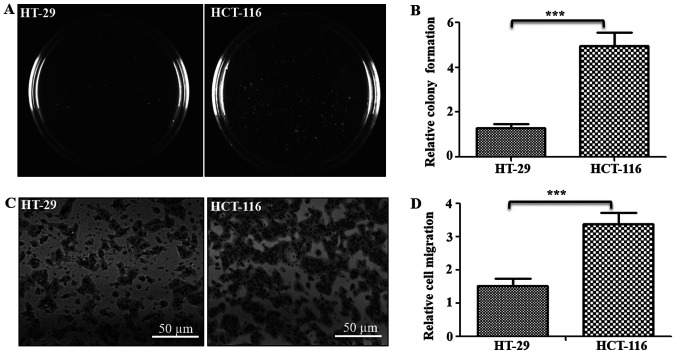

To study the role of mitochondrial functions in the metastatic potential of CRC cells, low metastatic HT-29 and high metastatic HCT-116 CRC lines were used. To confirm whether these cells demonstrate their respective cancer properties, the tumorigenic and metastatic potentials were examined using soft agar and Transwell assays, respectively (Fig. 1). Results of soft agar assay indicated that HCT-116 cells formed ~3.8-fold higher numbers of clones on soft agar compared with HT-29 cells (Fig. 1A and B). Similarly, Transwell assay results identified that the number of cells that migrated through the ECM matrix were ~2.3-fold higher in HCT-116 cells compared with HT-29 cells (Fig. 1C and D). Thus, these assays confirmed the tumorigenic and metastatic potentials of both cells, indicating HT-29 cells as low tumorigenic and metastatic, with HCT-116 cells as highly tumorigenic and metastatic in nature.

Figure 1.

Tumorigenic and metastatic potential of colorectal cancer cells. (A) Soft agar assay was performed to measure the tumorigenic potential of cells. The colonies were imaged and counted after 3 weeks, and representative images of one of the three experiments are shown. (B) Total number of colonies were counted and represented as relative colony units. (C) Cell migration was analyzed using Transwell assay (triplicate/line), and cells that migrated to the lower surface were stained and imaged. Scale bar, 50 µm. (D) Number of cells migrated and stained was counted and represented relative migration units. ***P<0.001 vs. HT-29 cells.

Resistance to C-I inhibition in low metastatic cells

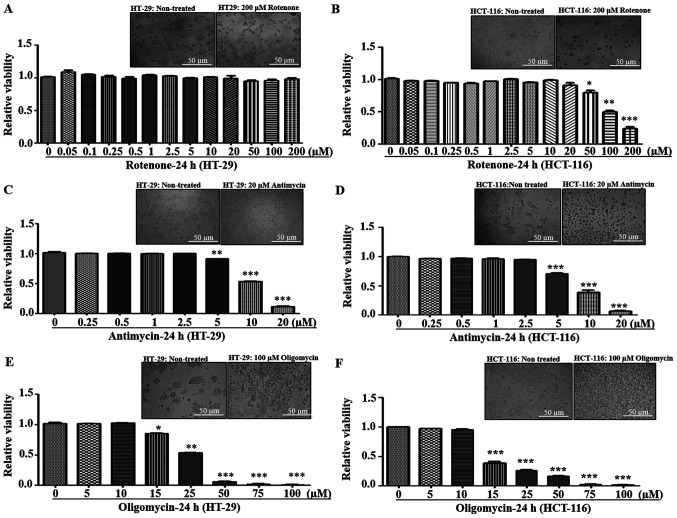

In mitochondria, C-I and Complex III (C-III) are considered as the major producers of superoxide anions among RC complexes, and inhibition of these complexes results in an increased mitochondrial oxidative stress (27–29). The present study investigated the effect of mitochondrial oxidative stress via pharmacological inhibition of these complexes by measuring cellular viability of metastatic cells. Rotenone is a C-I inhibitor that acts by blocking the transfer of electrons from iron-sulfur centers in C-I to ubiquinone, which results in the inhibition of OXPHOS, limited ATP production and increased free radical production (30). Similarly, antimycin-A is a C-III inhibitor that binds to the quinone reduction site of C-III, leading to increased superoxide production (31). Cells were treated with different concentrations of rotenone and antimycin-A to measure the effect of C-I and C-III inhibition on cellular viability, respectively. It was found that both HT-29 and HCT-116 cells were tolerant to lower concentrations of rotenone (0–20 µM). However, at >20 µM concentration, HCT-116 cells demonstrated increased sensitivity and cell death, while HT-29 cells had resistance up to 200 mM (Fig. 2A and B). With regards to antimycin, both cell lines exhibited a similar trend of declined viability at ≥5 µM (Fig. 2C and D).

Figure 2.

Effect of mitochondrial respiratory chain inhibitors on cell viability. (A) HT-29 and (B) HCT-116 cells were treated with varying concentrations of the Complex I inhibitor rotenone (0.05–200 µM) for 24 h. (C) HT-29 and (D) HCT-116 cells were treated with varying concentrations of the Complex III inhibitor antimycin (0.25–20 µM) for 24 h. (E) HT-29 and (F) HCT-116 cells were treated with varying concentrations of the Complex V inhibitor oligomycin (5–100 µM) for 24 h. Bright field images of cells were captured at ×100 magnification, and representative images for control and treatment are provided to indicate morphological changes at the highest concentration for various inhibitors. Cellular viability was measured via trypan Blue staining and calculated relative to non-treated cells. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 vs. 0 µM of rotenone/antimycin/oligomycin.

Since electron transfer via RC complexes is associated with ATP production, the effect of ATP synthase [Complex-V (C-V)] inhibition using oligomycin was examined. Oligomycin is an inhibitor of C-V that functions by inducing conformational change in the F0 subunit and impairs binding with substrate at the catalytic sites, leading to ATP depletion (32). Both HT-29 and HCT-116 cell lines demonstrated similar sensitivity to C-V inhibition, with decreased viabilities at ≥15 µM oligomycin concentrations (Fig. 2E and F). Overall, in response to different RC inhibitors, low metastatic HT-29 cells had significant resistance towards rotenone treatment compared with high metastatic cells, indicating possible C-I abnormalities.

Resistance of low metastatic cells to C-I inhibition was assessed via repeatedly measuring cell viability after paraquat treatment, another C-I inhibitor. Paraquat is reduced by C-I to form paraquat cation radicals, which react with oxygen to form superoxide (28). C-I inhibition was similar in both the inhibitors (rotenone and paraquat); HT-29 cells were resistant to higher concentration of paraquat compared with HCT-116 cells, and could tolerate concentrations up to 20 mM without decreasing cell viability (Fig. S1). Thus, the investigation of RC inhibitors on cell viability suggested that low metastatic HT-29 cells were tolerant to higher concentrations of C-I inhibitors (Rotenone and paraquat) compared with high metastatic cells, which indicated a compromised or non-functional C-I in HT-29 cells.

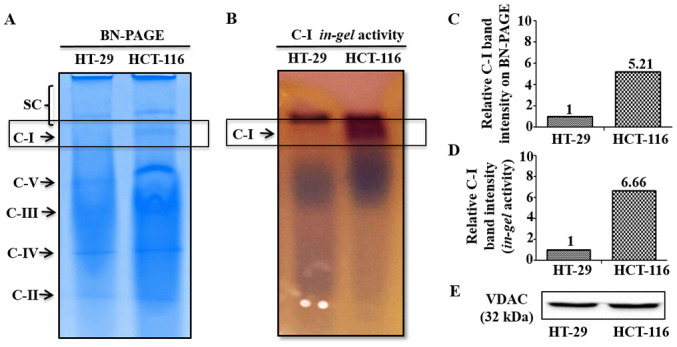

Upregulated C-I and mitochondrial functions in high metastatic cells

In order to investigate potential differences in C-I functionality between low and high metastatic cells that may contribute to their sensitivity to C-I inhibition, C-I assembly and activity were analyzed using BN-PAGE and C-I in-gel activity assay, respectively. These measurements were performed in the isolated mitochondria from low and high metastatic cells. BN-PAGE results demonstrated an enhanced C-I assembly via increased expression of C-I specific band in HCT-116 cells, while its corresponding band was almost absent in HT-29 cells (Fig. 3A and C). Similarly, functional activity of assembled C-I was higher in HCT-116 compared with HT-29 cells as indicated by increased staining of C-I band in C-I specific in-gel activity assay (Fig. 3B and D). Equal loading of mitochondrial preparation for BN-PAGE/in-gel assay from these cells was confirmed by western blotting of similar aliquot with mitochondrial marker protein VDAC as loading control (Fig. 3E).

Figure 3.

Mitochondrial C-I assembly and activity analysis. (A) BN-PAGE was performed in the isolated mitochondrial preparation of cultured cells. (B) C-I activity was measured using in gel C-I activity assay. Relative band intensities of C-I on (C) BN-PAGE and (D) in-gel assay were quantitated using ImageJ and normalized with total mitochondrial protein loaded (80 µg). (E) Equal loading of mitochondrial proteins is shown by immunoblotting results of an aliquot of the same samples used for BN-PAGE/in-gel assay, with mitochondrial marker protein VDAC. C-, complex; VDAC, Voltage-dependent anion channel; BN-PAGE, Blue native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis.

To assess whether this upregulation of C-I was a common feature in other high metastatic cells, two different CRC cells, HCT-15 and COLO-205, with low and high metastatic potential, respectively (33), were used. C-I functionality was determined by measuring the gene expression profile of mtDNA encoded C-I genes. mtDNA encodes seven C-I subunit genes (ND-1, −2, −3, −4, −4L, −5 and −6) (13), and RT-qPCR analysis was performed to detect the mRNA expression of 5 of these subunit genes (except ND-3 and ND-5 genes) in metastatic cells. Significantly higher expression levels of C-I genes were identified in high metastatic COLO-205 cells, compared with low metastatic HCT-15 cells (Fig. S2A), which confirmed C-I upregulation in high metastatic cells.

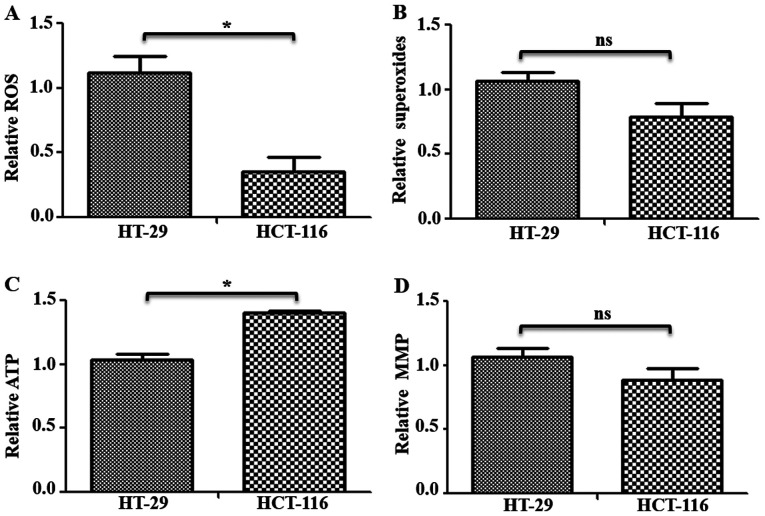

C-I is the major entry point for electrons in electron transfer chain, and its inhibition may cause changes in free radicals and mitochondrial functions (10,12). Therefore, to investigate the status of mitochondrial functions in these cells, ROS, mitochondrial superoxides, ATP and MMP levels were measured in HT-29 and HCT-116 cells. Total ROS levels were measured using H2DCFDA, which remains non-fluorescent until oxidized to the highly fluorescent 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein radicals. Compared with HT-29 cells, HCT-116 cells had significantly lower levels (~0.76-fold lower) of total ROS (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, mitochondrial superoxide levels were measured using indicator dye MitoSOX™ Red, which is oxidized by mitochondrial superoxides. While a decrease in mitochondrial superoxide levels was observed in HCT-116 cells, it was not significantly different compared with HT-29 cells (Fig. 4B). Measurement of total ATP in these cells identified a ~0.36-fold significantly higher ATP content in HCT-116 compared with HT-29 cells (Fig. 4C). However, there was no significant difference in MMP levels (Fig. 4D). Similar changes in mitochondrial functions were observed when examined in additional CRC cells (Fig. S2B).

Figure 4.

Functional status of mitochondria in colorectal cancer cells. Cells (~1×106) were used for mitochondrial functional analysis. (A) Total ROS levels were measured via staining with 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate, and (B) mitochondrial superoxide levels were measured using MitoSOX™ Red staining followed by measurement on fluorescence plate reader. In both cases, cells were counterstained with Hoechst-33342 and used for normalization. (C) Total cellular ATP content was measured in cells with a luciferase-based ATP detection kit, and normalized with total protein levels. (D) MMP was measured after tetramethylrhodamine methyl ester perchlorate staining and normalization using Hoechs-33342 reading. *P<0.05. ns, not significant; ROS, reactive oxygen species; MMP, Mitochondrial Membrane Potential.

Therefore, the results suggested that C-I assembly and activity were worse in low metastatic cells, while C-I was upregulated in high metastatic cells, which may contribute to improved mitochondrial functions, such as decreased oxidative stress, increased ATP levels and enhanced cellular proliferation.

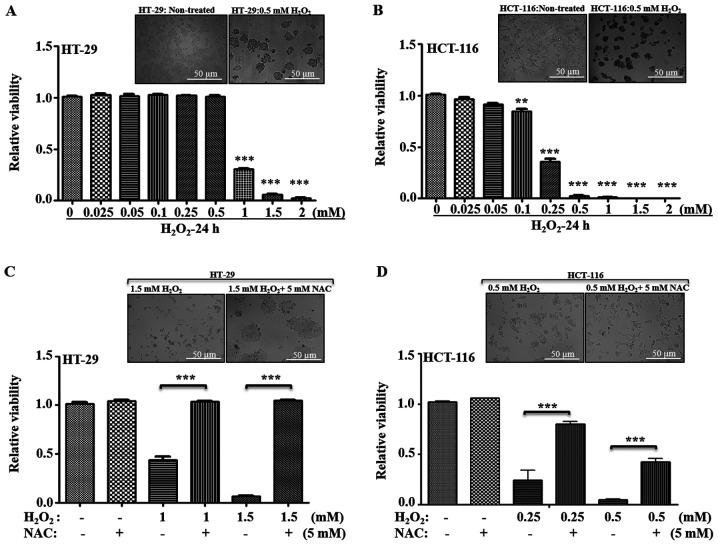

Increased sensitivity to oxidative stress in high metastatic cells

Various chemotherapeutic agents can induce cell death in tumor cells via generation of oxidative stress. To further evaluate whether the metastatic potential of CRC cells depends upon changes in C-I and mitochondrial functionality via their response to higher oxidative stress, their susceptibility towards a general oxidative stress agent, H2O2, was examined. H2O2 is a well-studied oxidative stress-inducing agent, where transient exposure triggers apoptosis in a variety of mammalian cells (34–37). Thus, low and high metastatic cells were treated with varied concentration of H2O2, and their viability was measured (Fig. 5A and B). In HT-29 cells, no significant cell death was observed from 0.025–0.5 mM H2O2 concentrations; a significant decrease in viability was observed at ≥1 mM (Fig. 5B). Compared with HT-29, HCT-116 cells demonstrated a higher sensitivity to H2O2-induced cell death at ≥0.1 mM; with a ~0.40-fold viability at 0.25 mM, and <0.05-fold viability at ≥0.5 mM concentrations of H2O2 (Fig. 5A and B).

Figure 5.

Effect of oxidative stress on cellular viability. (A) HT-29 and (B) HCT-116 cells were treated with varying concentrations of H2O2 for 24 h, and viability was measured using trypan blue staining. The relative fold changes in the viability was calculated considering control as 1 and compared with viability of cells at different H2O2 concentrations. Representative bright field images are provided for non-treated and 0.5 mM H2O2 treated cells. Similarity, the effect of antioxidant (NAC: 5 mM) on (C) HT-29 and (D) HCT-116 cell survival, with or without the H2O2 at given concentrations, was measured and compared with their non-treated control. Representative images indicate the recovery of cells after NAC treatment. Scale bar, 50 µm. **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 vs. 0 mM H2O2/at indicated H2O2 concentrations without NAC. NAC, N-acetyl cysteine.

The general antioxidant NAC was used in combination with H2O2, and cellular viability was measured to examine whether the cells differed in their response to recovery after oxidative stress. Inhibitory concentrations of H2O2 for HT-29 cells (1–1.5 mM H2O2) and for HCT-116 cells (0.25–0.5 mM H2O2) were used with or without 5 mM NAC, and cellular viability was measured. It was identified that, with regards to HT-29 cells, antioxidant treatment significantly restored the viability, while HCT-116 cells demonstrated only partial recovery at the given inhibitory concentrations (Fig. 5C and D). Therefore, these results suggested that low metastatic cells were more tolerant to higher oxidative stress, and high metastatic cells were more sensitive to oxidative stress-induced cell death.

Elevated mitochondrial biogenesis in high metastatic cells

HCT-116 cells had increased C-I function and relatively improved mitochondrial functionality, such as lower levels of ROS and higher ATP levels, compared with HT-29 cells (Figs. 3 and 4A), suggesting an association between effective C-I activity and proliferative signaling pathways, which may contribute to tumor aggressiveness. To understand how high metastatic cells maintain a functional C-I, it was evaluated whether high metastatic cells upregulate the compensatory pathway of mitochondrial biogenesis.

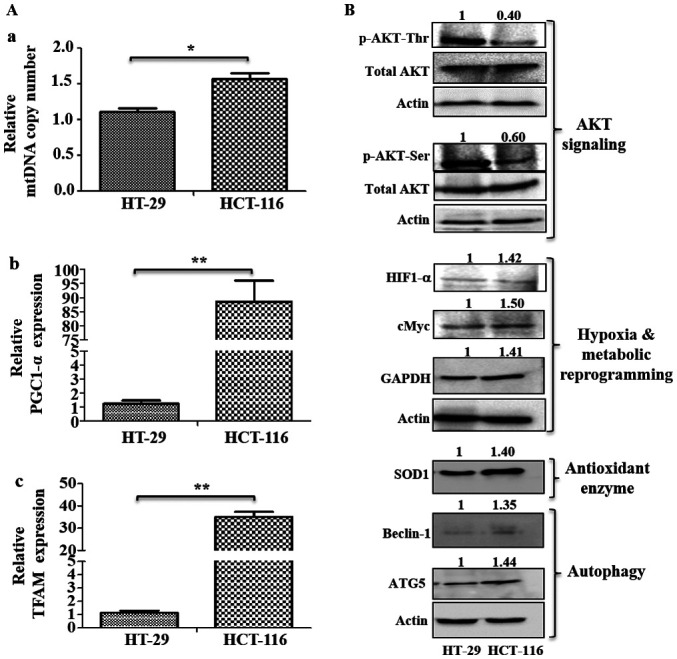

Measurement of mtDNA copy number is an important aspect of mitochondrial biogenesis and reflects the mitochondrial requirements for cellular function (38). Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator α (PGC1-α), is a major regulator of the mitochondrial biogenesis, which stimulates transcription of numerous mitochondrial genes via mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM), a key regulator in mtDNA replication and transcription (39). The present study measured mtDNA copy number and mitochondrial biogenesis markers to determine mitochondrial requirements during metastasis (Fig. 6A). It was found that HCT-116 cells had higher mtDNA copy numbers compared with HT-29 cells (Fig. 6A-a). RT-qPCR analysis also identified significantly higher expression levels of mitochondrial biogenesis markers (PGC1-α and TFAM) in HCT-116 cells compared with HT-29 cells (Fig. 6A-b and c), indicating an increase in mitochondrial numbers and biogenesis. Similarly, enhanced mitochondrial copy number, biogenesis and transcription were observed in other high metastatic cell lines (Fig. S2C).

Figure 6.

Analysis of mitochondrial biogenesis and signaling pathways. (A) Mitochondrial biogenesis was measured via mtDNA copy number and mRNA expression of mitochondrial biogenesis markers. (A-a) Changes in mtDNA copy number were determined using the SYBR green qPCR method. mRNA expression levels of (A-b) mitochondrial biogenesis marker PGC1-α and (A-c) TFAM were analyzed using reverse transcription-quantitative PCR. (B) Immunoblotting was performed to analyze the expression levels of p-AKT (Ser 478 and Thr 308), HIF1-α, cMyc, GAPDH, SOD1, Beclin-1 and ATG5. Values represent relative band intensities of protein that were measured by densitometry, normalized with actin loading control and presented as relative to HT-29. p-AKT (Ser 478 and Thr 308) proteins were normalized with total AKT as well as actin, and other proteins were normalized with β-actin as loading control. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01. p-, phosphorylated; HIF1-α, hypoxia inducible factor 1 subunit α; SOD1, superoxide dismutase 1; ATG5, autophagy related 5; PGC1-α, Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator α; TFAM, mitochondrial transcription factor A; mtDNA, mitochondrial DNA.

Investigation of metastatic signaling based on metastatic potential

HT-29 cells had relatively higher levels of p-AKT at both Ser473 and Thr308 residues compared with HCT-116 cells (Fig. 6B). However, HCT-116 cells had upregulated expression levels of HIF1-α, cMyc, GAPDH, the antioxidant enzyme SOD1 and autophagy markers (Beclin-1 and ATG5), compared with HT-29 cells (Fig. 6B).

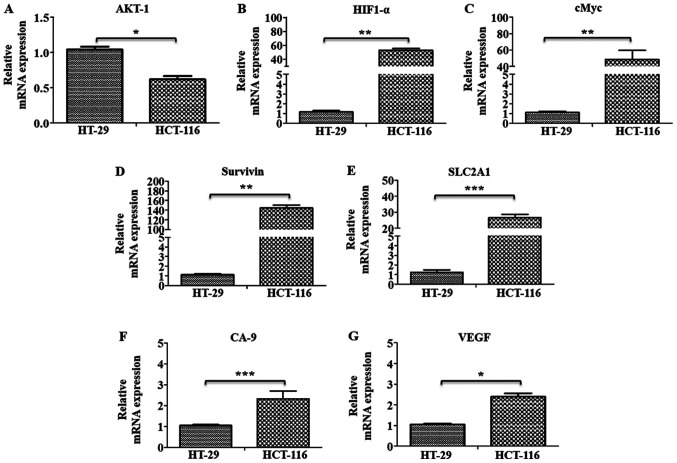

The gene expression levels of marker proteins of major pathways, such as oncogenic signaling (AKT-1), hypoxia (HIF1-α) and metabolic reprogramming (cMyc and GAPDH), were further examined using RT-qPCR analysis, along with the HIF1-α target genes SLC2A1, Survivin, CA-9 and VEGF in these cells. All these markers, (except AKT-1), were found to be significantly upregulated in HCT-116 cells compared with HT-29 cells, indicating their involvement in metastatic progression in these cells (Fig. 7A-G).

Figure 7.

Gene expression profiling of oncogenic and metastatic marker genes. mRNA expression levels of (A) AKT-1, (B) HIF1-α, (C) cMyc, (D) Survivin, (E) SLC2A1, (F) CA-9 and (G) VEGF genes were analyzed using SYBR green-based reverse transcription-quantitative PCR. Results are presented as the fold change in the mRNA expression relative to HT-29. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001. HIF1-α, hypoxia inducible factor 1 subunit α; SLC2A1, solute carrier family 2 member 1; CA-9, carbonic anhydrase-9.

Pharmacological inhibition of C-I in high metastatic cells blocks metastatic signaling

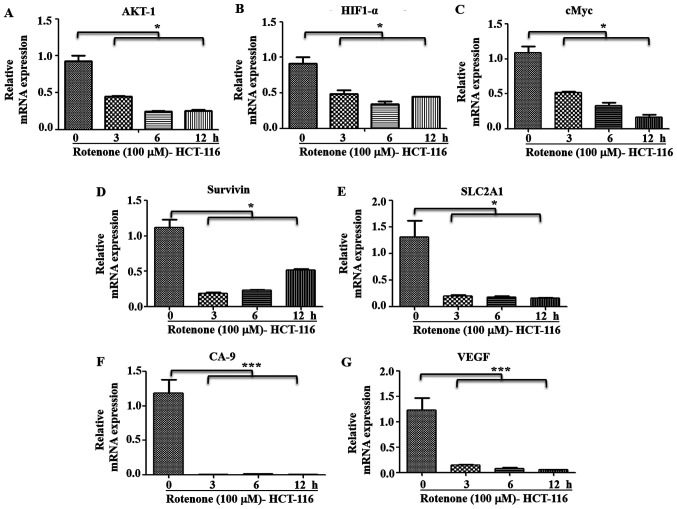

It was observed that metastatic HCT-116 cells demonstrated a functional C-I and pharmacological inhibition of C-I, and these cells had higher sensitivity to C-I-induced cell death compared with HT-29 cells (Figs. 2B and S1B). It was hypothesized that C-I recovery may serve an important role in the transition to the metastatic stage by enhancing metastatic signaling. Thus, the effect of C-I inhibition on metastatic signaling in high metastatic cells was also studied. HCT-116 cells were treated with inhibitory concentration of rotenone (100 µM), and early time points (0, 3, 6 and 12 h) were selected for measuring gene expression profile of metastatic pathways. It was identified that rotenone treatment significantly decreased the mRNA expression levels of AKT-1, HIF1-α, cMyc, SLC2A1, Survivin, GAPDH, CA-9 and VEGF compared with non-treated controls (Fig. 8A-G). In addition, paraquat treatment in these cells with similar conditions resulted in a similar pattern of decreased gene expression levels of these markers, as compared with the control group cells (Fig. S3A-G).

Figure 8.

Effect of C-I inhibition on metastatic signaling. HCT-116 cells were treated with rotenone (100 µM) for indicated time points, and RNA was used for reverse transcription-quantitative PCR. mRNA expression levels of (A) AKT-1, (B) HIF1-α, (C) cMyc, (D) Survivin, (E) SLC2A1, (F) CA-9 and (G) VEGF genes were analyzed using SYBR green dye. Fold changes were calculated relative to non-treated control at 0 h. *P<0.05 and ***P<0.001. HIF1-α, hypoxia inducible factor 1 subunit α; SLC2A1, solute carrier family 2 member 1; CA-9, carbonic anhydrase-9.

These results suggested that the functional C-I was restored or re-activated in high metastatic cells to maintain or activate oncogenic and metastatic signaling. Moreover, it was indicated that pharmacological inhibition of C-I in high metastatic cells resulted in a decrease in these signaling pathways leading to cell death, thus implicating C-I as a therapeutic target for highly metastatic conditions.

Discussion

Cancer metastasis includes the migration, invasion and survival of cancer cells in the circulation, followed by their proliferation at distal sites (40). Moreover, this is a highly complex process in which cancer cells modify their metabolic requirements for growth and proliferation to achieve metastasis (41). It has been proposed that mitochondria are implicated in the malignant transformation of healthy cells mainly by three major mechanisms: i) By generating ROS or oxidative stress, which may cause oncogenic mutations and activation of oncogenic signaling (42); ii) reprogramming of mitochondrial metabolic pathways, leading to accumulation of onco-metabolites (43); and iii) resistance to mitochondrial permeability transition-driven cell death (44). Among these mechanisms, oxidative stress has been examined extensively, and several studies have reported that oxidative stress serves a major role in malignant transformation of primary tumors and enhances their metastatic potential (6,7,16). However, the precise role of ROS is debatable as the threshold levels of ROS vary between cancer cell types, cancer cell responses and signaling mechanisms to ROS insults.

Mitochondrial RC complexes, mainly C-I and C-III, are involved in generating the majority of free radicals from mitochondria (27,29). Thus, it is important to understand the specific changes in these RC complexes, as well as their contribution in altering the mitochondrial functions and associated signaling pathways. Since CRC rapidly progresses to metastatic phase, the present study used CRC cells with different metastatic potential as in vitro model systems. The current report investigated the effect of mitochondrial stress on respiratory complexes, to understand the functional changes in these complexes and their contribution in metastatic signaling.

The metastatic properties of CRC cells were validated in vitro, and it was demonstrated that HCT-116 cells were more aggressive and metastatic in nature compared with HT-29 cells. Although healthy colon cells would be a more appropriate choice for comparison with low and high metastasis, due to non-availability of these cells and the present focus on comparing low and high metastasis, a known pair of low (HT-29) and high metastatic cells (HCT-116) were selected for the current study. The response of these cells towards mitochondrial RC inhibition and their adaptability of higher oxidative stress were investigated.

Since ROS are generated by leakage of electrons from RC complexes, the present study examined the effect of RC inhibition primarily via C-I and C-III, which are major contributors of mitochondrial oxidative stress-induced cell death in mammalian cells (27,29). Low metastatic HT-29 cells were found to be more resistant to C-I inhibition compared with HCT-116 cells, suggesting a higher threshold for C-I mediated oxidative stress in low metastatic conditions. These findings were further corroborated by increased tolerance and improved adaptation to additional oxidative stress by low metastatic cells, as evidenced by their resistance to higher concentrations of H2O2 and significant recovery after antioxidant treatment compared with other cells. In general, increasing oxidative stress beyond the threshold in cancer cells has been key for current cancer therapeutics to induce targeted cancer cell death (45). However, in multiple types of tumors, including prostate, melanoma and breast cancer, the increased metastatic ability of tumor cells is positively associated with their intracellular ROS levels (46), and exogenous treatment of ROS can enhance certain stages of metastasis (47). The present results suggested a higher tolerance to oxidative stress in low metastatic conditions compared with in high metastatic conditions. Furthermore, inducing apoptosis by enhancing oxidative stress may not be an effective strategy in early stages, as it may significantly enhance cytotoxicity in healthy cells and contribute to detrimental outcomes.

Previous studies have reported that partial impairment of C-I due to heteroplasmic mtDNA mutation in C-I subunit gene increases tumorigenic potential via ROS-mediated oncogenic activation (10,12). An inhibitory effect on tumorigenesis is observed when these C-I defects are severe during conditions of homoplasmic mtDNA mutations in the same C-I subunit gene (10). Moreover, other studies on nuclear encoded C-I subunits or assembly proteins revealed that these C-I associated proteins act as tumor suppressors (48–50). However, there is no consensus on the role of C-I subunits, as several findings observed the upregulation of these proteins in tumor samples (51,52), which may be due to their differential involvement during metastatic process (15). The present study demonstrated that C-I sassembly and activity were inhibited in low metastatic cells compared with high metastatic cells, indicating that inhibited C-I may limit the cellular ability for rapid metastatic transformations. Analysis of mitochondrial functions demonstrated that low metastatic cells with C-I inhibition had increased ROS levels and decreased ATP levels.

The metastatic process involves cell proliferation at distal sites, adaptation to low oxygen environment, metabolic reprogramming and activation of cellular recycling machinery; thus, the contribution of different component of these signaling pathways in metastatic cells was investigated. Mitochondrial alteration, specifically activated via C-I defects, is associated with activation of AKT, which inhibits apoptotic proteins, leading to cell survival in stressed conditions (10,53). The current study further identified that increased phosphorylation of AKT in low metastatic conditions may provide a survival advantage, specifically to oxidatively-stressed and energy-deprived cells, acting as an adaptive response. This finding was in line with previous reports, which suggested that AKT upregulation is an early event in colon carcinogenesis and is more common in sporadic cases compared with microsatellite instability-high colon cancer cases (54,55). AKT is differentially regulated in CRC, and specifically, the AKT-1 isoform has opposite and inhibitory effect on metastasis compared with other isoforms (56). In the current study, the mRNA expression profiling of AKT-1 and immunoblotting results indicated that low metastatic cells demonstrated increased oncogenic AKT signaling compared with high metastatic cells. Thus, it was hypothesized that while this enhanced AKT signaling may contribute to local cellular proliferation and cellular adaptation of low metastatic cells to high oxidative stress, it may be insufficient for metastatic progression. In addition, this process may involve metabolic alterations and activation of angiogenic pathways for adaptation to microenvironment at distal sites. High metastatic cells had increased mitochondrial biogenesis to restore C-I and mitochondrial functions, and C-I and mitochondrial functions were compromised during early metastasis, as observed in low metastatic cells.

Similarly, during metastatic transformation, cells experience low oxygen levels, and therefore, stabilize hypoxia inducible transcription factors, such as hypoxia inducible factor 1 subunit α (HIF1-α), which activates several downstream targets, including the glucose transporter solute carrier family 2 member 1 (SLC2A1) (57), Survivin for anti-apoptosis (58) and angiogenic factors, such as carbonic anhydrase-9 (CA-9) (59) and VEGF (60), which are associated with tumor invasion and metastasis. The cMyc oncogene, an important transcription factor, is a key regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis and targets 100s of mitochondrial genes (61). Oncogenic activation of cMyc is reported to increase biosynthetic and respiratory capacity, and contribute to upregulating glycolytic and mitochondrial metabolism for enhanced metastatic potential (61). Although mitochondrial biogenesis and HIF1-α expression are inversely related in certain cancer types, a positive correlation between these factors has also been revealed during cMyc activation and confers metabolic advantages to tumor cells, which tend to exist in a hypoxic microenvironment (62). The present study observed a synergistic role of mitochondrial biogenesis, cMyc and HIF1-α in high metastatic cells that may explain the restoration of C-I expression and activity, decreasing ROS levels and partially improving ATP levels, thus indicating their role in enhancing metastatic activity. Furthermore, gene expression analysis identified the upregulation of HIF1-α targeted genes, such as the glucose transporter SLC2A1, the anti-apoptotic protein Survivin and the metastatic markers, VEGF and CA-9, suggesting a metabolic reprogramming mechanism in high metastatic cells that may contribute to their aggressiveness.

The current study demonstrated a direct association of C-I functions in metastatic signaling, as inhibition of C-I in high metastatic cells resulted in a decrease in oncogenic and metastatic signaling, leading to a decline in cellular viability. Therefore, the results highlighted the role of functional C-I in the survival of high metastatic cells. Highly metastatic cells demonstrate aggressive features and can survive under harsh environments, including oxidative stress (63), and the current study observed elevated levels of the antioxidant enzyme SOD1, which is known to scavenge cytoplasmic free radicals (64). This partly explains the lower levels of ROS in high metastatic cells compared with low metastatic cells. In addition, the upregulation of the autophagy-indicator proteins Beclin-1 and ATG5 was found in high metastatic cells. Autophagy has reported to serve an important role in different stages of metastasis (65). Specifically in CRC, autophagy exerts a pro-active effect as revealed by increased expression of Beclin-1 (66) and inhibition of ATG5, which results in an inhibitory effect on tumorigenesis both in vitro and in vivo (67). Therefore, upregulation of these proteins in high metastatic cells indicates a positive contribution of autophagy in metastasis, possibly by enhanced clearance of damaged mitochondria via mitophagy, but this requires further investigation.

There are certain limitations to the present study, including the lack of investigation into the specific components of these signaling pathways associated with C-I functionality and the absence of in vivo experiments. The effect of complex IV (C-IV) inhibition, could not be determined due to potential hazard and regulatory restriction on the use of C-IV inhibitor potassium cyanide. The upregulation of autophagy proteins indicated the role of autophagy in metastasis. However, the role of selective clearance of mitochondria via mitophagy requires further investigation. Therefore, additional studies are required to identify molecular mechanism of C-I targeting molecules and their potential use in developing effective therapies for highly fatal metastatic cancer types.

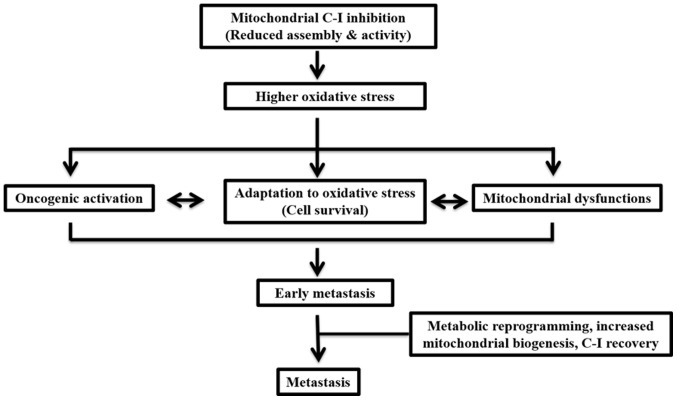

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that, during early metastasis, impairments in C-I may contribute to enhanced ROS levels, which may lead to cellular adaptation via activation of cell survival pathways (Fig. 9). In a state of high metastasis, cells may be reprogrammed via a coordinated upregulation of mitochondrial biogenesis and cMyc to restore C-I and the overall mitochondrial functions required for their aggressive features. The current results also suggested that threshold levels of ROS depend on C-I activity and the level of metastasis. Therefore, these should be considered when selecting therapies for cancer, as the threshold and adaptation for oxidative stress are different in early and late phases of metastasis, and can change the outcome of the disease after pro- or anti-oxidant therapies. Moreover, a functional role of C-I was identified, and suggested C-I as a potential therapeutic target for highly metastatic cancer types that are otherwise resistant to chemotherapy.

Figure 9.

Schematic presentation of the major conclusion of the current study. Functionally compromised C-I leads to increased oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction and oncogenic activation. Together these contribute to the adaptation of cancer cells against oxidative stress in the early metastatic phase. Subsequently, metabolic reprogramming and increased mitochondrial biogenesis with C-I recovery may contribute to enhanced metastatic activity. C-, complex.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr Lia R. Edmunds (University of Pittsburgh) for proofreading the manuscript.

Funding

Funding was received from Science and Engineering Research Board (grant nos. SB/YS/LS-95/2013 and CRG/2018/001559) and DBT Bio-CARe grant (grant no. BT/P19357/BIC/101/927/2016). NKR was supported by junior research fellowship [grant no. 16-6 (Dec.2017)/2018] from CSIR-UGC.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

NKR, SM and SKS planned and performed the experiments, complied and analyzed the data. MT, ST and LKS were involved in study design, planning of experiments, data analysis and interpretation and writing the manuscript. RH helped in performing experiments on additional cell lines to validate the findings. VKS was involved in statistical analysis and revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Zorov DB, Juhaszova M, Sollott SJ. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) and ROS-induced ROS release. Physiol Rev. 2014;94:909–950. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00026.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simon HU, Haj-Yehia A, Levi-Schaffer F. Role of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in apoptosis induction. Apoptosis. 2000;5:415–418. doi: 10.1023/A:1009616228304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wallace DC. Mitochondria as chi. Genetics. 2008;179:727–735. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.91769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vyas S, Zaganjor E, Haigis MC. Mitochondria and cancer. Cell. 2016;166:555–566. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schieber M, Chandel NS. ROS function in redox signaling and oxidative stress. Curr Biol. 2014;24:R453–R462. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.03.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Le Gal K, Ibrahim MX, Wiel C, Sayin VI, Akula MK, Karlsson C, Dalin MG, Akyürek LM, Lindahl P, Nilsson J, Bergo MO. Antioxidants can increase melanoma metastasis in mice. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7:308re8. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aad3740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Piskounova E, Agathocleous M, Murphy MM, Hu Z, Huddlestun SE, Zhao Z, Leitch AM, Johnson TM, DeBerardinis RJ, Morrison SJ. Oxidative stress inhibits distant metastasis by human melanoma cells. Nature. 2015;527:186–191. doi: 10.1038/nature15726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ward PS, Thompson CB. Metabolic reprogramming: A cancer hallmark even warburg did not anticipate. Cancer Cell. 2012;21:297–308. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lu J, Sharma LK, Bai Y. Implications of mitochondrial DNA mutations and mitochondrial dysfunction in tumorigenesis. Cell Res. 2009;19:802–815. doi: 10.1038/cr.2009.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Park JS, Sharma LK, Li H, Xiang R, Holstein D, Wu J, Lechleiter J, Naylor SL, Deng JJ, Lu J, Bai Y. A heteroplasmic, not homoplasmic, mitochondrial DNA mutation promotes tumorigenesis via alteration in reactive oxygen species generation and apoptosis. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:1578–1589. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Santidrian AF, Matsuno-Yagi A, Ritland M, Seo BB, LeBoeuf SE, Gay LJ, Yagi T, Felding-Habermann B. Mitochondrial complex I activity and NAD+/NADH balance regulate breast cancer progression. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:1068–1081. doi: 10.1172/JCI64264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sharma LK, Fang H, Liu J, Vartak R, Deng J, Bai Y. Mitochondrial respiratory complex I dysfunction promotes tumorigenesis through ROS alteration and AKT activation. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:4605–4616. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sharma LK, Lu J, Bai Y. Mitochondrial respiratory complex I: Structure, function and implication in human diseases. Curr Med Chem. 2009;16:1266–1277. doi: 10.2174/092986709787846578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Urra FA, Munoz F, Lovy A, Cardenas C. The mitochondrial complex(I)ty of cancer. Front Oncol. 2017;7:118. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2017.00118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leone G, Abla H, Gasparre G, Porcelli AM, Iommarini L. The oncojanus paradigm of respiratory complex I. Genes (Basel) 2018;9:243. doi: 10.3390/genes9050243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gill JG, Piskounova E, Morrison SJ. Cancer, oxidative stress, and metastasis. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2016;81:163–175. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2016.81.030791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Edmunds LR, Sharma L, Wang H, Kang A, d'Souza S, Lu J, McLaughlin M, Dolezal JM, Gao X, Weintraub ST, et al. c-Myc and AMPK control cellular energy levels by cooperatively regulating mitochondrial structure and function. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0134049. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0134049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wittig I, Karas M, Schagger H. High resolution clear native electrophoresis for in-gel functional assays and fluorescence studies of membrane protein complexes. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2007;6:1215–1225. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M700076-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fang H, Liu X, Shen L, Li F, Liu Y, Chi H, Miao H, Lu J, Bai Y. Role of mtDNA haplogroups in the prevalence of knee osteoarthritis in a southern Chinese population. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15:2646–2659. doi: 10.3390/ijms15022646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:1101–1108. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li QF, Wang XR, Yang YW, Lin H. Hypoxia upregulates hypoxia inducible factor (HIF)-3alpha expression in lung epithelial cells: Characterization and comparison with HIF-1alpha. Cell Res. 2006;16:548–558. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7310072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Onishi Y, Ueha T, Kawamoto T, Hara H, Toda M, Harada R, Minoda M, Kurosaka M, Akisue T. Regulation of mitochondrial proliferation by PGC-1α induces cellular apoptosis in musculoskeletal malignancies. Sci Rep. 2014;4:3916. doi: 10.1038/srep03916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spandidos A, Wang X, Wang H, Seed B. PrimerBank: A resource of human and mouse PCR primer pairs for gene expression detection and quantification. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D792–D799. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wheaton WW, Weinberg SE, Hamanaka RB, Soberanes S, Sullivan LB, Anso E, Glasauer A, Dufour E, Mutlu GM, Budigner GS, Chandel NS. Metformin inhibits mitochondrial complex I of cancer cells to reduce tumorigenesis. Elife. 2014;3:e02242. doi: 10.7554/eLife.02242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salehi MH, Kamalidehghan B, Houshmand M, Meng GY, Sadeghizadeh M, Aryani O, Nafissi S. Gene expression profiling of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) complex I in Friedreich ataxia (FRDA) patients. PLoS One. 2014;9:e94069. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen Q, Vazquez EJ, Moghaddas S, Hoppel CL, Lesnefsky EJ. Production of reactive oxygen species by mitochondria: Central role of complex III. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:36027–36031. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304854200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cocheme HM, Murphy MP. Complex I is the major site of mitochondrial superoxide production by paraquat. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:1786–1798. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708597200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dröse S, Brandt U. Molecular mechanisms of superoxide production by the mitochondrial respiratory chain. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2012;748:145–169. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-3573-0_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Palmer G, Horgan DJ, Tisdale H, Singer TP, Beinert H. Studies on the respiratory chain-linked reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide dehydrogenase. XIV. Location of the sites of inhibition of rotenone, barbiturates, and piericidin by means of electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy. J Biol Chem. 1968;243:844–847. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang LS, Cobessi D, Tung EY, Berry EA. Binding of the respiratory chain inhibitor antimycin to the mitochondrial bc1 complex: A new crystal structure reveals an altered intramolecular hydrogen-bonding pattern. J Mol Biol. 2005;351:573–597. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.05.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Penefsky HS. Mechanism of inhibition of mitochondrial adenosine triphosphatase by dicyclohexylcarbodiimide and oligomycin: Relationship to ATP synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:1589–1593. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.6.1589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Trainer DL, Kline T, McCabe FL, Faucette LF, Field J, Chaikin M, Anzano M, Rieman D, Hoffstein S, Li DJ, et al. Biological characterization and oncogene expression in human colorectal carcinoma cell lines. Int J Cancer. 1988;41:287–296. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910410221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Singh M, Sharma H, Singh N. Hydrogen peroxide induces apoptosis in HeLa cells through mitochondrial pathway. Mitochondrion. 2007;7:367–373. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Viola HM, Arthur PG, Hool LC. Transient exposure to hydrogen peroxide causes an increase in mitochondria-derived superoxide as a result of sustained alteration in L-type Ca2+ channel function in the absence of apoptosis in ventricular myocytes. Circ Res. 2007;100:1036–1044. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000263010.19273.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Whittemore ER, Loo DT, Watt JA, Cotman CW. A detailed analysis of hydrogen peroxide-induced cell death in primary neuronal culture. Neuroscience. 1995;67:921–932. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00108-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xiang J, Wan C, Guo R, Guo D. Is hydrogen peroxide a suitable apoptosis inducer for all cell types? Biomed Res Int. 2016;2016:7343965. doi: 10.1155/2016/7343965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Clay Montier LL, Deng JJ, Bai Y. Number matters: Control of mammalian mitochondrial DNA copy number. J Genet Genomics. 2009;36:125–131. doi: 10.1016/S1673-8527(08)60099-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Virbasius JV, Scarpulla RC. Activation of the human mitochondrial transcription factor A gene by nuclear respiratory factors: A potential regulatory link between nuclear and mitochondrial gene expression in organelle biogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:1309–1313. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.4.1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van Zijl F, Krupitza G, Mikulits W. Initial steps of metastasis: Cell invasion and endothelial transmigration. Mutat Res. 2011;728:23–34. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Phan LM, Yeung SC, Lee MH. Cancer metabolic reprogramming: Importance, main features, and potentials for precise targeted anti-cancer therapies. Cancer Biol Med. 2014;11:1–19. doi: 10.7497/j.issn.2095-3941.2014.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sabharwal SS, Schumacker PT. Mitochondrial ROS in cancer: Initiators, amplifiers or an Achilles' heel? Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14:709–721. doi: 10.1038/nrc3803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sullivan LB, Gui DY, Vander Heiden MG. Altered metabolite levels in cancer: Implications for tumour biology and cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2016;16:680–693. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Izzo V, Bravo-San Pedro JM, Sica V, Kroemer G, Galluzzi L. Mitochondrial permeability transition: New findings and persisting uncertainties. Trends Cell Biol. 2016;26:655–667. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2016.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang J, Yi J. Cancer cell killing via ROS: To increase or decrease, that is the question. Cancer Biol Ther. 2008;7:1875–1884. doi: 10.4161/cbt.7.12.7067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lim SD, Sun C, Lambeth JD, Marshall F, Amin M, Chung L, Petros JA, Arnold RS. Increased Nox1 and hydrogen peroxide in prostate cancer. Prostate. 2005;62:200–207. doi: 10.1002/pros.20137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jing X, Ueki N, Cheng J, Imanishi H, Hada T. Induction of apoptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines by emodin. Jpn J Cancer Res. 2002;93:874–882. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2002.tb01332.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.He X, Zhou A, Lu H, Chen Y, Huang G, Yue X, Zhao P, Wu Y. Suppression of mitochondrial complex I influences cell metastatic properties. PLoS One. 2013;8:e61677. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kalakonda S, Nallar SC, Jaber S, Keay SK, Rorke E, Munivenkatappa R, Lindner DJ, Fiskum GM, Kalvakolanu DV. Monoallelic loss of tumor suppressor GRIM-19 promotes tumorigenesis in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:E4213–E4222. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1303760110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li LD, Sun HF, Liu XX, Gao SP, Jiang HL, Hu X, Jin W. Down-regulation of NDUFB9 promotes breast cancer cell proliferation, metastasis by mediating mitochondrial metabolism. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0144441. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0144441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Su CY, Chang YC, Yang CJ, Huang MS, Hsiao M. The opposite prognostic effect of NDUFS1 and NDUFS8 in lung cancer reflects the oncojanus role of mitochondrial complex I. Sci Rep. 2016;6:31357. doi: 10.1038/srep31357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Suhane S, Berel D, Ramanujan VK. Biomarker signatures of mitochondrial NDUFS3 in invasive breast carcinoma. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;412:590–595. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pelicano H, Xu RH, Du M, Feng L, Sasaki R, Carew JS, Hu Y, Ramdas L, Hu L, Keating MJ, et al. Mitochondrial respiration defects in cancer cells cause activation of Akt survival pathway through a redox-mediated mechanism. J Cell Biol. 2006;175:913–923. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200512100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Agarwal E, Brattain MG, Chowdhury S. Cell survival and metastasis regulation by Akt signaling in colorectal cancer. Cell Signal. 2013;25:1711–1719. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2013.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Roy HK, Olusola BF, Clemens DL, Karolski WJ, Ratashak A, Lynch HT, Smyrk TC. AKT proto-oncogene overexpression is an early event during sporadic colon carcinogenesis. Carcinogenesis. 2002;23:201–205. doi: 10.1093/carcin/23.1.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ericson K, Gan C, Cheong I, Rago C, Samuels Y, Velculescu VE, Kinzler KW, Huso DL, Vogelstein B, Papadopoulos N. Genetic inactivation of AKT1, AKT2, and PDPK1 in human colorectal cancer cells clarifies their roles in tumor growth regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:2598–2603. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914018107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chen C, Pore N, Behrooz A, Ismail-Beigi F, Maity A. Regulation of glut1 mRNA by hypoxia-inducible factor-1. Interaction between H-ras and hypoxia. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:9519–9525. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010144200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chen P, Zhu J, Liu DY, Li HY, Xu N, Hou M. Over-expression of survivin and VEGF in small-cell lung cancer may predict the poorer prognosis. Med Oncol. 2014;31:775. doi: 10.1007/s12032-013-0775-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Loncaster JA, Harris AL, Davidson SE, Logue JP, Hunter RD, Wycoff CC, Pastorek J, Ratcliffe PJ, Stratford IJ, West CM. Carbonic anhydrase (CA IX) expression, a potential new intrinsic marker of hypoxia: Correlations with tumor oxygen measurements and prognosis in locally advanced carcinoma of the cervix. Cancer Res. 2001;61:6394–6399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shweiki D, Itin A, Soffer D, Keshet E. Vascular endothelial growth factor induced by hypoxia may mediate hypoxia-initiated angiogenesis. Nature. 1992;359:843–845. doi: 10.1038/359843a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Li F, Wang Y, Zeller KI, Potter JJ, Wonsey DR, O'Donnell KA, Kim JW, Yustein JT, Lee LA, Dang CV. Myc stimulates nuclearly encoded mitochondrial genes and mitochondrial biogenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:6225–6234. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.14.6225-6234.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dang CV, Kim JW, Gao P, Yustein J. The interplay between MYC and HIF in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:51–56. doi: 10.1038/nrc2274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kumari S, Badana AK, Gavara MM, Gugalavath S, Malla R. Reactive oxygen species: A key constituent in cancer survival. Biomark Insights. 2018;13:1177271918755391. doi: 10.1177/1177271918755391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Che M, Wang R, Li X, Wang HY, Zheng XFS. Expanding roles of superoxide dismutases in cell regulation and cancer. Drug Discov Today. 2016;21:143–149. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2015.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mowers EE, Sharifi MN, Macleod KF. Autophagy in cancer metastasis. Oncogene. 2017;36:1619–1630. doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ahn CH, Jeong EG, Lee JW, Kim MS, Kim SH, Kim SS, Yoo NJ, Lee SH. Expression of beclin-1, an autophagy-related protein, in gastric and colorectal cancers. APMIS. 2007;115:1344–1349. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2007.00858.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sakitani K, Hirata Y, Hikiba Y, Hayakawa Y, Ihara S, Suzuki H, Suzuki N, Serizawa T, Kinoshita H, Sakamoto K, et al. Inhibition of autophagy exerts anti-colon cancer effects via apoptosis induced by p53 activation and ER stress. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:795. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1789-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.