Anesthesiologists and Intensivists are at the forefront, managing patients afflicted with covid 19 and are facing extremely challenging working conditions. These specialties are expected to take care of patients at different areas of hospital like emergency department, operation theatre, ICU, resuscitation etc., Work in these areas demands accurate and timely intervention and any delay can be disastrous. The nature of closed and often constrained working environment puts them at great risk of contracting infection. Furthermore, aerosol generating procedures like endotracheal intubation and suctioning are regularly performed at these areas.

The Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) seems to be the only savior under these circumstances. The PPE entails a full body cover from head to toe, goggles covering eyes, face shield, an N95 mask. Though the PPE protects us from COVID-19, working with a PPE on is a challenging task as one faces heat, dehydration, inability to eat or drink anything etc., All these problems have been very well highlighted in the literature and media. One problem which often escapes attention is that of difficulty in communication while one is wearing a PPE.

Anesthesiologists work in an environment where there is lot of interdependence on fellow colleagues, surgical colleagues, junior staff, staff nurses and anesthesia technicians. Directed communication and closed-loop communication is particularly important in these extremely sensitive areas for proper co-ordination and co-operation.[1] Effective communication relies on clarity ('keeping it clear'), brevity ('keeping it brief)', empathy ('how will it feel to receive this?'), with provision for a feedback loop.[2] The verbal communication is often supplemented by communication through body language, body gestures and facial expressions.[3]

All these modes of communication become extremely difficult while wearing a PPE. One's voice becomes muffled with an N 95 mask on, face shield acts further as a barrier and even facial and bodily gestures cannot be recognized. This necessitates speaking loudly, repetition of messages and there can be errors in understanding. Any misinterpretation of communication due to PPE may result in hazardous situation and even wrong or delayed administration of treatment. Having an alternative to verbal communication, thus seems to be desirable to reduce chances of error.

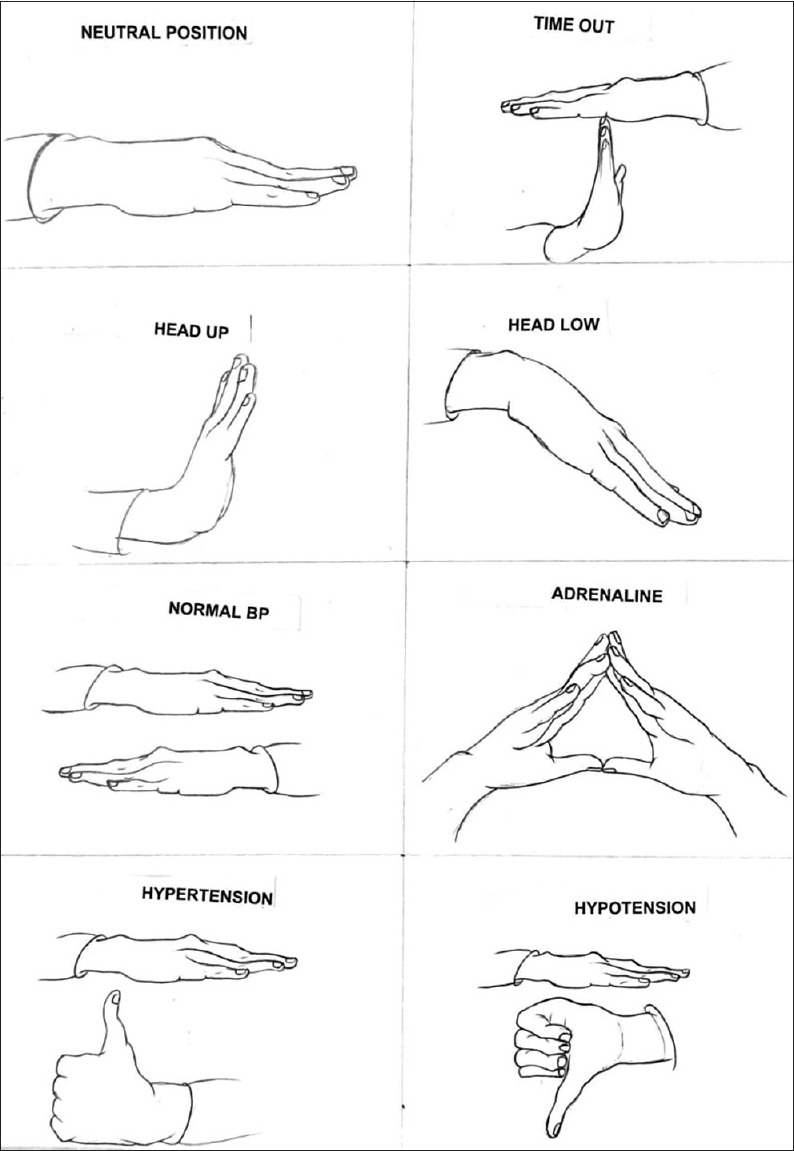

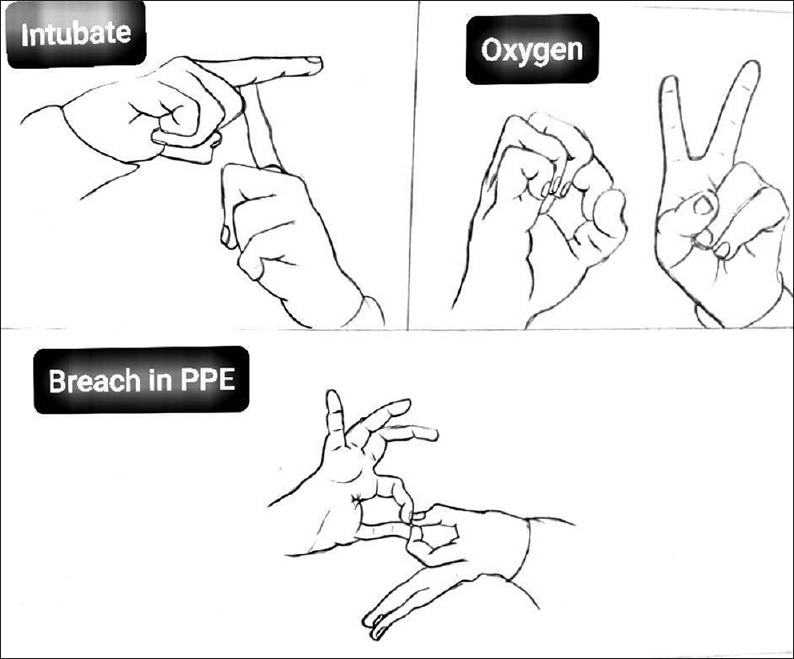

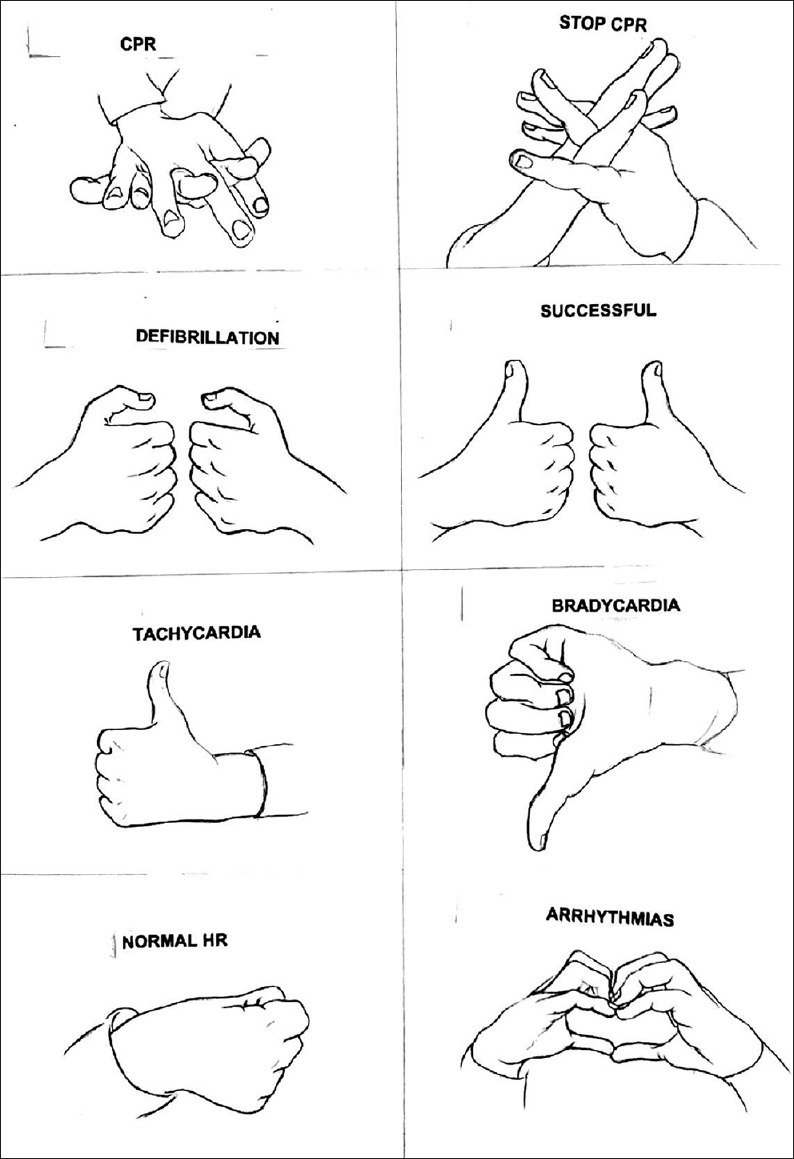

Socrates, the world renowned Greek philosopher, had said:”If we hadn't a voice or a tongue, and wanted to express things to one another, wouldn't we try to make signs by moving our hands, head, and the rest of our body, just as dumb people do at present” Under the present circumstances, we probably need to take lesson from this teaching and adapt ourselves. Using sign language while wearing a PPE, has the potential to reduce errors related to communication, but it is important to have a uniform sign code for commonly encountered conditions. In this context, we propose following signs, some of which may already be in use at some places [Figures 1-3]. It is equally important to discuss and teach these signs to co-workers and ancillary staff for optimal results.

Figure 1.

Signs for common clinical situations

Figure 3.

Signs for common clinical situations

Figure 2.

Signs for common clinical situations

We seem to be living in a new world order now with a new normal. It is the responsibility of each one of us to adapt to these changes so as to safeguard ourselves and our co-workers without compromising on the patients' safety. This probably is the time to contrive actions with hands to deliver important instructions during these times of covid pandemic.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Davies JM. Team communication in the operating room. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2005;49:898–901. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2005.00636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Awad SS, Fagan SP, Bellows C, Albo D, Green-Rashad B, De la Garza M, et al. Bridging the communication gap in the operating room with medical team training. Am J Surg. 2005;190:770–4. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2005.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jones CPL, Fawker-Corbett J, Groom P, Morton B, Lister C, Mercer SJ. Human factors in preventing complications in anaesthesia: A systematic review. Anaesthesia. 2018;73(Suppl 1):12–24. doi: 10.1111/anae.14136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]