The synthesis of a variety of enantioenriched 1,3-diketospiranes from the corresponding racemic allyl β-ketoesters via an interrupted asymmetric allylic alkylation is disclosed.

The synthesis of a variety of enantioenriched 1,3-diketospiranes from the corresponding racemic allyl β-ketoesters via an interrupted asymmetric allylic alkylation is disclosed.

Abstract

The synthesis of a variety of enantioenriched 1,3-diketospiranes from the corresponding racemic allyl β-ketoesters via an interrupted asymmetric allylic alkylation is disclosed. Substrates possessing pendant aldehydes undergo decarboxylative enolate formation in the presence of a chiral Pd catalyst and subsequently participate in an enantio- and diastereoselective, intramolecular aldol reaction to furnish spirocyclic β-hydroxy ketones which may be oxidized to the corresponding enantioenriched diketospiranes. Additionally, this chemistry has been extended to α-allylcarboxy lactam substrates leading to a formal synthesis of the natural product (–)-isonitramine.

The enantioselective construction of spirocyclic compounds remains an enduring challenge in organic synthesis, and has been the subject of intensive investigation in recent years.1 Owing to their prevalence in bioactive natural products and privileged ligand scaffolds, as well as their potential in drug discovery, methods for the stereoselective preparation of these unique motifs represent powerful technologies in synthetic chemistry.2,3 At present, there are few reliable methods for the direct catalytic, enantioselective synthesis of these valuable building blocks. Of particular interest are spirocyclic compounds bearing a chiral, quaternary carbon as the spiro atom. Due to the difficulty associated with the enantioselective preparation of all-carbon quaternary centers,4 and the added challenge of spirocyclization, a catalytic asymmetric approach to these ring systems represents a significant challenge for modern, asymmetric catalysis.

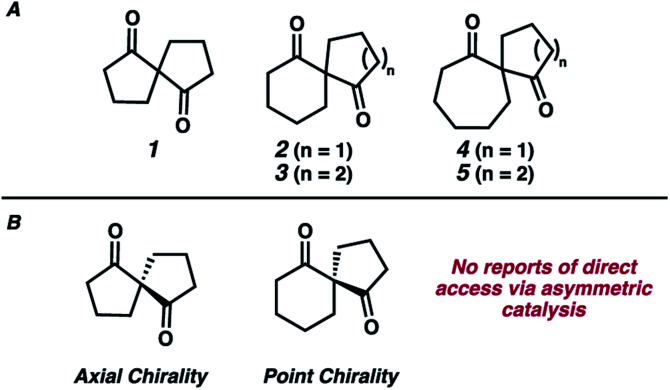

One particularly interesting and underexplored subclass of spirocyclic compounds are 1,3-diketospiranes such as those shown in Fig. 1A. While the preparation of racemic 1,3-diketospiranes such as 1–5 is known and relatively straightforward,5 these scaffolds are significantly more difficult to prepare as single enantiomers.6 Depending upon the identity of each of the rings within the spirocyclic framework, these compounds can possess either axial (e.g.1 and 3, Fig. 1B) or point chirality. Previous enantioselective routes to these motifs have relied almost exclusively on chiral resolution technology or chiral auxiliaries to prepare enantioenriched samples of 1–5, with only 2 examples of asymmetric catalysis being utilized in the context of the synthesis of these compounds.6c,h

Fig. 1. Examples of 1,3-diketospiranes and their stereochemical properties.

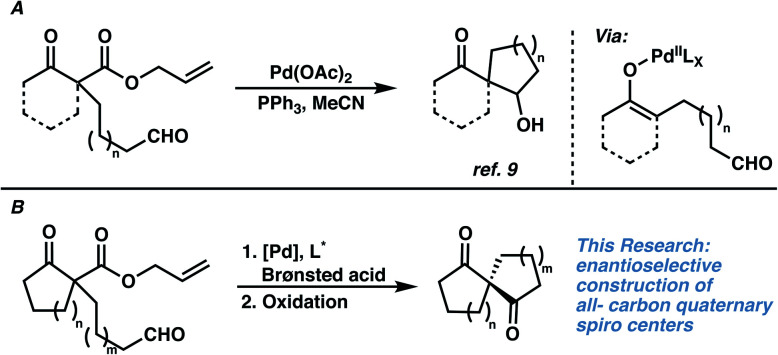

Given our laboratory's longstanding focus on the development of catalytic methods for the asymmetric α-functionalization of carbonyl compounds for the synthesis of quaternary centers, in addition to the lack of currently available stereoselective methods for the synthesis of 1,3-diketospiranes, we became interested in targeting this class of molecules.7,8 As an inspiration, we turned to a seminal report by Tsuji and coworkers (Fig. 2A) detailing a palladium-catalyzed aldol reaction via decarboxylative enolate formation and subsequent intramolecular trapping with a pendant aldehyde. Given our mechanistic understanding of related asymmetric processes wherein chiral Pd-enolates have been implicated, we hypothesized that a chiral Pd-enolate might be able to trap the electrophile in a stereocontrolled fashion. We envisioned that oxidation of the resultant β-hydroxyketone would then furnish the desired enantioenriched 1,3-diketospiranes.

Fig. 2. (A) Previously reported example of an interrupted allylic alkylation reaction. (B) Development of an enantioselective variant, and application to the synthesis of 1,3-diketospiranes.

Our study commenced with the development of an enantioselective variant of Tsuji's intramolecular aldol reaction.9 After examining a wide variety of Pd precatalysts, chiral ligands, and solvents (see ESI for details†), we were delighted to find that exposure of substrate 2a to Pd(OAc)2 and (S)-t-Bu-PHOX in THF delivered diastereomeric spirocycles 2b and 2c, albeit in low yield and moderate diastereo- and enantioselectivity (Table 1, entry 1). Upon further investigation, we found that the addition of a Brønsted acid to the reaction is crucial for good conversion to the desired spirocyclic products (Table 1, entries 2 and 3), and thus reasoned that it must play a critical role in the reaction mechanism.

Table 1. Optimization of the asymmetric spirocyclization.

| |||||

| Entry | Acid | Solvent | % conv. a , b | d.r. (b : c) a | % ee c |

| 1 | None | THF | 48 | 42 : 58 | 72 (53) |

| 2 | Aniline | THF | >99 | 69 : 31 | 58 (23) |

| 3 | Meldrum's acid | THF | >99 | 72 : 28 | 9 (13) |

| 4 d | Acetic acid | THF | — e (77) | 60 : 40 | 74 (45) |

| 5 | Phenol | THF | 71 | 74 : 26 | 81 (30) |

| 6 | Thymol | THF | >99 | 76 : 24 | 81 (31) |

| 7 | 2-Methoxyphenol | THF | >99 | 67 : 33 | 82 (29) |

| 8 | 2,6-Dimethoxyphenol | THF | >99 | 41 : 59 | 84 (44) |

| 9 | 3,5-Dimethoxyphenol | THF | 76 | 63 : 37 | 83 (24) |

| 10 | 3,5-Dimethylphenol | THF | 68 | 74 : 26 | 81 (42) |

| 11 f | 3,5-Dimethylphenol | THF | — e (91) | 75 : 25 h | 83 (47) |

| 12 f , g | 3,5-Dimethylphenol | 1,4-Dioxane | — e (90) | 85 : 15 h | 85 (73) |

aDetermined by GC unless otherwise noted.

bParenthetical value is yield of isolated product.

cDetermined by chiral SFC after transformation to benzoyl ester; parenthetical value is ee of minor diastereomer.

dReaction performed for 37 h.

eConsumption of 2a was monitored by TLC.

fReaction performed at 40 °C.

g15 mol% ligand.

hDetermined by 1H NMR.

After surveying a variety of Brønsted acids, we found that phenols performed best, with 3,5-dimethylphenol providing the highest combination of yield and enantioselectivity. Thus, the use of Pd(OAc)2 (10 mol%) with (S)-t-Bu-PHOX and 3,5-dimethylphenol as the Brønsted acid in 1,4-dioxane (0.1 M) at 40 °C proved optimal (entry 12), furnishing spirocyclic β-hydroxy ketones 2b and 2c in 90% isolated yield, 85% ee (major diastereomer 2b) in an 85:15 d.r.10

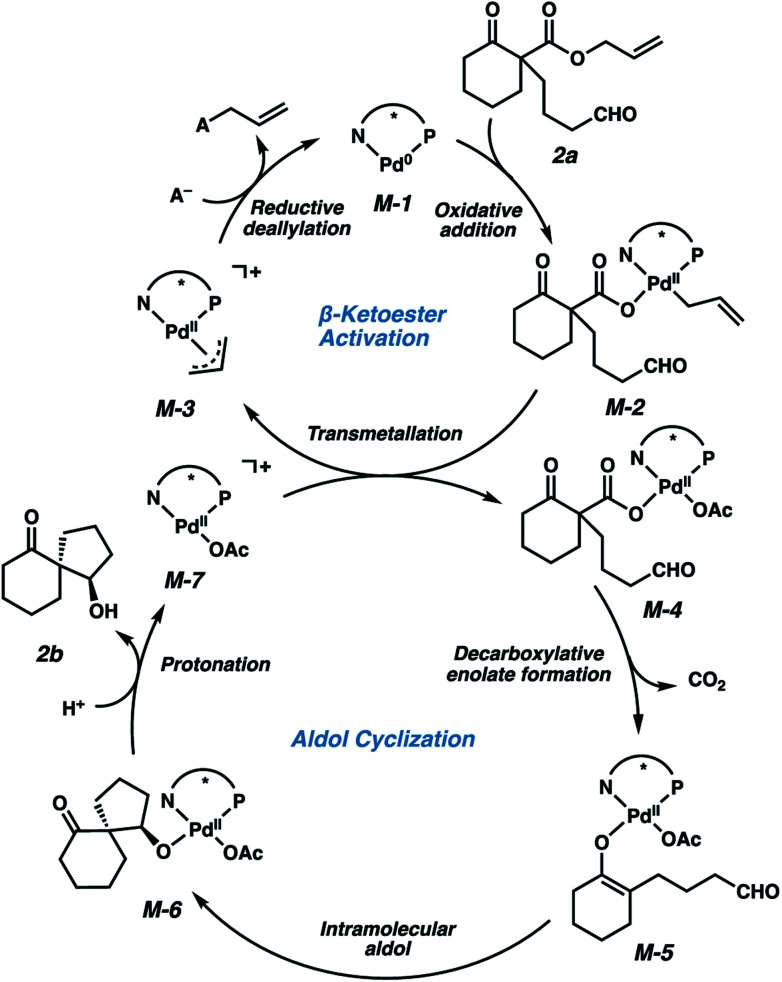

We envision that the catalytic cycle (Fig. 3) commences with oxidative deallylation of β-ketoester 2a by a Pd(0) (M-1) species to furnish Pd(ii) carboxylate M-2. A transmetalation onto Pd(ii) species M-7 generates a new Pd(ii) carboxylate (M-4) that can then undergo rate-limiting decarboxylative enolate formation.11 Enolate M-5 then undergoes an intramolecular aldol cyclization to Pd(ii) alkoxide M-6, which enantioselectively sets the stereochemistry at the quaternary spiro atom. At this point, the Brønsted acid (i.e., H+) serves to protonate the resulting alkoxide, releasing the product (2b), and regenerating Pd(ii) species M-7 while the conjugate base (i.e., A–) acts as a nucleophile by reductive deallylation of M-3 to regenerate Pd(0) species M-1.12 This proposed cycle accounts for the critical role of the Brønsted acid observed in this reaction, as well as the fact that a Pd(ii) precatalyst may be employed. We envision that only a small excess of phosphine ligand is required to produce a limited amount of Pd(0) species M-1, to enter the β-ketoester activation cycle.

Fig. 3. Mechanistic proposal including Brønsted acid-mediated catalyst turnover (A– represents conjugate base of the Brønsted acid additive).

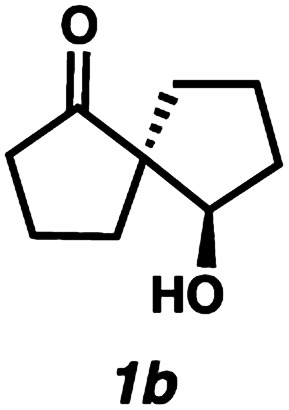

With optimal conditions for the spirocyclization in hand, we next turned our attention to the application of this reaction toward the synthesis of various 1,3-diketospiranes. Cyclic allyl β-ketoesters of varying core ring sizes possessing aldehydes with different tether lengths were synthesized and subjected to the optimized spirocyclization conditions. We found that the conditions developed performed generally well across various ring sizes and tether lengths providing spirocyclic β-hydroxyketones in high yields and with high enantioselectivity, albeit with moderate diastereoselectivity. The diastereomeric mixtures obtained were generally difficult to separate by flash chromatography, and thus, these mixtures were treated directly with DMP to furnish the desired enantioenriched 1,3-diketospiranes. Importantly, following oxidation, the modest diastereomeric mixtures converged to enantioenriched diketones, demonstrating that the primary enantiocontrol is occurring at the quaternary center by differentiation of the enantiotopic faces of the enolate. Additionally, recrystallization of spiro[4.4]nonanedione 1 and spiro[5.5]undecanedione 3 in hexanes provided these products in excellent levels of enantioenrichment (94% and 95% ee, respectively). The relative configurations of the spiro β-hydroxyketone diastereomers 1b/c, 2e/f, and 3b/c (Table 2, entries 1, 2 and 4) were determined by comparing chemical shifts to literature values,6f while absolute configuration of the quaternary carbon atom in 1 and 2 (entries 1 and 2) was determined by comparing optical rotations with reported literature values.6a,f

Table 2. Enantioselective synthesis of 1,3-diketospiranes.

| ||||||

| Entry | Aldol product | % yield | d.r. a | Oxidized product b | % yield | % ee c |

| 1 |

|

77 | 72 : 28 |

|

88 | 83 (95) d |

| 2 |

|

84 | 67 : 33 |

|

88 | 73 |

| 3 |

|

90 | 85 : 15 |

|

93 | 84 |

| 4 |

|

82 | 76 : 24 |

|

82 | 84 (94) d |

| 5 |

|

92 | 66 : 34 |

|

93 | 81 |

| 6 |

|

76 | 67 : 33 | — | — | 84 e |

| 7 |

|

94 | 62 : 38 | — | — | 72 f |

aDetermined by 1H NMR.

bOxidized with DMP.

cDetermined by chiral GC.

dAfter recrystallization from hexane.

eDetermined by chiral SFC after transformation to benzoyl ester.

fDetermined by SFC.

Given the success of our protocol for the synthesis of 1,3-diketospiranes, we next became interested in expanding the scope of this procedure for the preparation of other spirocyclic 1,3-dicarbonyl systems. As N-protected lactams have previously been shown to perform exceptionally well in our Pd-catalyzed asymmetric allylic alkylation reactions,8c and owing to the prevalence of N-heterocyclic spirocycles in natural products and bioactive molecules, we turned our attention to this class of substrates.

Gratifyingly, we found that, after switching to thymol or acetic acid as the Brønsted acid, aldehyde-containing N-benzoyl lactams 7a–10a (Table 3) proved competent substrates for our spirocyclization protocol. Lactam substrates generally furnish outstanding yields of diastereomeric mixtures of spirocyclic β-hydroxy lactams in up to 78 : 22 dr. Importantly, the diastereomers of this substrate class are readily separable by flash column chromatography on silica. While the pyrrolidinone substrates provide the corresponding azaspirocycles 7b/c and 8b/c in high yield, the dr's and ee's are diminished (entries 1 and 2). By contrast, the major diastereomers of the 6,5-azaspirocycle 9b (entry 3) and the 6,6-azaspirocycle 10b (entry 4) could be prepared with excellent ee, while the minor diastereomers 9 and 10c were obtained in only moderate ee.

Table 3. Enantioselective synthesis of spirocyclic β-hydroxy lactams.

| |||||

| Entry | Products |

% yield | d.r. (b : c) | % ee a of b, c | |

| 1 |

|

|

94 | 50 : 50 | 55, 31 |

| 2 |

|

|

87 | 67 : 33 | 77, 32 |

| 3 b |

|

|

91 | 78 : 22 | 89, 79 |

| 4 |

|

|

93 | 58 : 42 | 93, 69 |

aDetermined by chiral SFC.

bAcetic acid used as Brønsted acid.

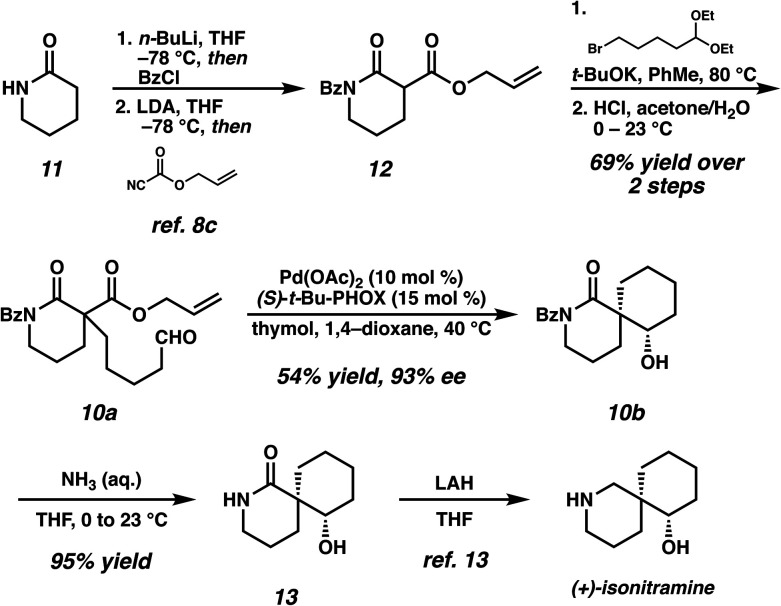

Debenzoylation of 6,6-azaspirocycle 10b furnishes lactam 13, a synthetic intermediate previously employed in the synthesis of the alkaloid (–)-isonitramine8f,13 thus completing a 7-step enantioselective synthesis of this natural product (Scheme 1). Furthermore, the stereochemistry of 13 (and thus of 10b) could be confirmed by chemical correlation with this known intermediate (Scheme 1). The absolute and relative stereochemistry of all other azaspirocycles has been determined in analogy to compound 8b (Table 3, entry 2), which was determined by X-ray diffraction.

Scheme 1. Formal synthesis of (–)-isonitramine.

In conclusion, we have reported a catalytic, enantioselective method for the construction of spirocyclic compounds containing all-carbon quaternary centers. This transformation provides unprecedented access to enantioenriched 1,3-diketospiranes of several sizes as well as spirocyclic β-hydroxy lactams which are useful for natural product synthesis, as evidenced by our application of this chemistry to the synthesis of (–)-isonitramine in 7 steps from commercially available starting materials. We envision that this method will be applicable to a wide range of potential target molecules, as well as provide access to a variety of valuable chiral building blocks.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This manuscript is dedicated to the memory of Prof. Teruaki Mukaiyama. The authors wish to thank NIH-NIGMS (R01GM080269), Astellas Pharma, Inc. (postdoctoral fellowship to K. I.), the Alfried Krupp von Bohlen and Halbach Foundation (fellowship to M. W.) and Amgen, Inc. (graduate fellowship to S. B.). We also thank Dr Scott C. Virgil for his support with chromatographic analysis, high-resolution mass analysis, and assistance during the crystallization process.

Footnotes

†Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available. CCDC 1999209. For ESI and crystallographic data in CIF or other electronic format see DOI: 10.1039/d0sc02366c

References

- For reviews of enantioselective synthesis of spirocyclic compounds, see: ; (a) Rios R. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012;41:1060. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15156h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Franz A. K., Hanhan N. V., Ball-Jones N. R. ACS Catal. 2013;3:540. [Google Scholar]; (c) Ball-Jones N. R., Badillo J. J., Franz A. K. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2012;10:5165. doi: 10.1039/c2ob25184a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Trost B. M., Brennan M. Synthesis. 2009;18:3003. [Google Scholar]; (e) Cheng D., Ishihara Y., Tan B., Barbas III C. F. ACS Catal. 2014;4:743. [Google Scholar]

- For general reviews of synthetic strategies toward spirocycles, see: ; (a) Smith L. K., Baxendale I. R. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2015;13:9907. doi: 10.1039/c5ob01524c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Krapcho A. P. Synthesis. 1974;6:383. [Google Scholar]; (c) Sannigrahi M. Tetrahedron. 1999;55:9007. [Google Scholar]; (d) Pradhan R., Patra M., Behera A. K., Mishra B. K., Behera R. K. Tetrahedron. 2006;62:779. [Google Scholar]; (e) Galliford C. V., Scheidt K. A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007;46:8748. doi: 10.1002/anie.200701342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Kotha S., Deb A. C., Lahiri K., Manivannan E. Synthesis. 2009;2:165. [Google Scholar]; (g) Zhuo C.-X., Zheng C., You S.-L. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014;47:2558. doi: 10.1021/ar500167f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) D'yakonov V. A., Trapeznikova O. A., de Meijere A., Dzhemilev U. M. Chem. Rev. 2014;114:5775. doi: 10.1021/cr400291c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For synthesis of selected spirocyclic natural products, see: ; (a) Lerchner A., Carreira E. M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:14826. doi: 10.1021/ja027906k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Trost B. M., Brennan M. K. Org. Lett. 2006;8:2027. doi: 10.1021/ol060298j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Doi T., Iijima Y., Takasaki M., Takahashi T. J. Org. Chem. 2007;72:3667. doi: 10.1021/jo062546v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For reviews of enantioselective synthesis of all-carbon quaternary stereocenters, see: ; (a) Fuji K. Chem. Rev. 1993;93:2037. [Google Scholar]; (b) Corey E. J., Guzman-Perez A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1998;37:388. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19980302)37:4<388::AID-ANIE388>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Christoffers J., Mann A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2001;40:4591. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20011217)40:24<4591::aid-anie4591>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Denissova I., Barriault L. Tetrahedron. 2003;59:10105. [Google Scholar]; (e) Douglas C. J., Overman L. E. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2004;101:5363. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307113101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Christoffers J., Baro A. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2005;347:1473. [Google Scholar]; (g) Trost B. M., Jiang C. Synthesis. 2006;3:369. [Google Scholar]; (h) Cozzi P. G., Hilgraf R., Zimmermann N. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2007;2007:5969. [Google Scholar]; (i) Prakash J., Marek I. Chem. Commun. 2011;47:4593. doi: 10.1039/c0cc05222a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Quasdorf K. W., Overman L. E. Nature. 2014;516:181. doi: 10.1038/nature14007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (k) Liu Y., Han S.-H., Liu W.-B., Stoltz B. M. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015;48:740. doi: 10.1021/ar5004658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (l) Feng J., Holmes M., Krische M. J. Chem. Rev. 2017;117:12564. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (m) Pierrot D., Marek I. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019;59:36. doi: 10.1002/anie.201903188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For examples of racemic syntheses of 1,3-diketospiranes, see: ; (a) Gerlach H., Muller W. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1972;11:1030. [Google Scholar]; (b) Wheeler T. N., Jackson C. A., Young K. H. J. Org. Chem. 1973;39:1318. [Google Scholar]; (c) Carruthers W., Orridge A. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1. 1977;21:2411. [Google Scholar]

- For preparations of enantioenriched 1,3-diketospiranes, see: ; (a) Gerlach H. Helv. Chim. Acta. 1968;51:1587. [Google Scholar]; (b) Hawkins E. G. E., Large R. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1. 1973:2169. [Google Scholar]; (c) Hayashi T., Kanehira K., Hagihara T., Kumada M. J. Org. Chem. 1988;53:113. [Google Scholar]; (d) Brunner R., Gerlach H. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 1994;5:1613. [Google Scholar]; (e) Nieman J. A., Parvez M., Keay B. A. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 1993;4:1973. [Google Scholar]; (f) Suemune H., Maeda K., Kato K., Sakai K. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1. 1994:3441. [Google Scholar]; (g) Han Z., Wang Z., Ding K. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2011;353:1584. [Google Scholar]; (h) Tsukamoto H., Kawase A., Doi T. Chem. Commun. 2015;51:8027. doi: 10.1039/c5cc02176f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For accounts and reviews of palladium-catalyzed allylic alkylation chemistry, see: ; (a) Trost B. M., Van Vranken D. L. Chem. Rev. 1996;96:395. doi: 10.1021/cr9409804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Trost B. M. Acc. Chem. Res. 1996;29:355. [Google Scholar]; (c) Helmchen G. J. Organomet. Chem. 1999;576:203. [Google Scholar]; (d) Trost B. M. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2002;50:1. doi: 10.1248/cpb.50.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Gräning T., Schmalz H.-G. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2003;42:2580. doi: 10.1002/anie.200301644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Trost B. M. J. Org. Chem. 2004;69:5813. doi: 10.1021/jo0491004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) You S.-L., Dai L.-X. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006;45:5246. doi: 10.1002/anie.200601889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Mohr J. T., Stoltz B. M. Chem.–Asian J. 2007;2:1476. doi: 10.1002/asia.200700183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Lu Z., Ma S. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008;47:258. doi: 10.1002/anie.200605113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Behenna D. C., Mohr J. T., Sherden N. H., Marinescu S. C., Harned A. W., Tani K., Seto M., Ma S., Novák Z., Krout M. R., McFadden R. M., Roizen J. L., Enquist Jr J. A., White D. E., Levine S. R., Petrova K. V., Iwashita A., Virgil S. C., Stoltz B. M. Chem.–Eur. J. 2011;17:14199. doi: 10.1002/chem.201003383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (k) Weaver J. D., Recio III A., Grenning A. J., Tunge J. A. Chem. Rev. 2011;111:1846. doi: 10.1021/cr1002744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (l) Hong A. Y., Stoltz B. M. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2013;2013:2745. doi: 10.1002/ejoc.201201761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (m) Liu Y., Han S.-J., Liu W.-B., Stoltz B. M. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015;48:740. doi: 10.1021/ar5004658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Behenna D. C., Stoltz B. M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:15044. doi: 10.1021/ja044812x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Trost B. M., Xu J., Schmidt T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:18343. doi: 10.1021/ja9053948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Behenna D. C., Liu Y., Yurino T., Kim J., White D. E., Virgil S. C., Stoltz B. M. Nat. Chem. 2012;4:130. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Reeves C. M., Eidamshaus C., Kim J., Stoltz B. M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013;52:6718. doi: 10.1002/anie.201301815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Korch K. M., Eidamshaus C., Behenna D. C., Nam S., Horne D., Stoltz B. M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015;54:179. doi: 10.1002/anie.201408609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Numajiri Y., Pritchett B. P., Chiyoda K., Stoltz B. M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:1040. doi: 10.1021/ja512124c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Craig II R. A., Loskot S. A., Mohr J. T., Behenna D. C., Harned A. M., Stoltz B. M. Org. Lett. 2015;17:5160. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b02376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nokami J., Mandai T., Watanabe H., Ohyama H., Tsuji J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989;111:4126. [Google Scholar]

- See ESI for experimental details, full optimization of the reaction conditions, and the synthesis of substrates

- Sherden N. H., Behenna D. C., Virgil S. C., Stoltz B. M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009;48:6840. doi: 10.1002/anie.200902575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varying amounts of the corresponding allyl phenyl ether have been observed and isolated suggesting that allylic alkylation of the phenol is the terminal fate of the allyl unit in these catalytic reactions

- Keppens M., De Kimpe N. J. Org. Chem. 1995;60:3916. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.