Abstract

The dynamic metallurgical characteristics of the selective laser melting (SLM) process offer fabricated materials with non-equilibrium microstructures compared to their cast and wrought counterparts. To date, few studies on the precipitation kinetics of SLM processed heat-treatable alloys have been reported, despite the importance of obtaining such detailed knowledge for optimizing the mechanical properties. In this study, for the first time, the precipitation behavior of an SLM fabricated Al—Mn—Sc alloy was systematically investigated over the temperature range of 300–450 °C. The combination of in-situ synchrotron-based ultra-small angle X-ray scattering (USAXS), small angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) and X-ray diffraction (XRD) revealed the continuous evolution of Al6Mn and Al3Sc precipitates upon isothermal heating in both precipitate structure and morphology, which was confirmed by ex-situ transmission electron microscopy (TEM) studies. A pseudo-delay nucleation and growth phenomenon of the Al3Sc precipitates was observed for the SLM fabricated Al—Mn—Sc alloy. This phenomenon was attributed to the preformed Sc clusters in the as-fabricated condition due to the intrinsic heat treatment effect induced by the unique layer-by-layer building nature of SLM. The growth kinetics for the Al6Mn and Al3Sc precipitates were established based on the in-situ X-ray studies, with the respective activation energies determined to be (74 ± 4) kJ/mol and (63 ± 9) kJ/mol. The role of the precipitate evolution on the final mechanical properties was evaluated by tensile testing, and an observed discontinuous yielding phenomenon was effectively alleviated with increased aging temperatures.

Keywords: Selective laser melting, Aluminum alloy, Scandium, Precipitation kinetics, In situ small angle X-ray scattering

1. Introduction

Selective laser melting (SLM), as one of the most common additive manufacturing (AM) techniques, has attracted growing attention due to its high flexibility for manufacturing geometrically complex parts [1]. By utilizing a high-energy laser beam and a high-precision computer-controlled powder bed platform, the traditional complex structured components that have to be jointed together by welding or fasteners from several individual parts can now be designed into one, and then directly fabricated by SLM [2]. Compared with conventional subtractive manufacturing methods, the layer-by-layer building nature of the SLM process also provides the manufacturing of complex parts with great benefits, such as high material utilization and short lead times. There is now widespread interest to apply the SLM process to new product development and real high value bespoke component manufacturing in many industrial sectors, including aerospace, automotive, electronics and biomedical [3–5].

Due to the highly localised laser beam melting and solidification in the powder bed, the ultrafast cooling rate within the countless molten pools can go up to 105-106 K/s, which endows the SLM fabricated parts with distinctive non-equilibrium microstructures [6]. The rapid solidification rate acts as a fast quenching effect within the molten pool, leading to significantly increased vacancy and dislocation densities within the SLM fabricated materials compared with normal casting processes [7]. Another typical microstructure resulting from the rapid solidification rate of SLM is the metastable cellular structure, which has been frequently reported for Al alloys, steels and high entropy alloys (HEA) [8–10]. Such extraordinary cellular structures are believed to be caused either by dislocation alignment or chemical segregation, both of which are expected to improve the mechanical properties of the SLM fabricated parts [11,12]. Furthermore, due to the layer-by-layer fusion and consolidation of the SLM process, previously deposited layers will experience a periodic thermal cycling of re-heating and re-cooling during the subsequent material building process. In other words, the underlying layers will experience an intrinsic heat treatment effect, leading to the formation of microstructural inhomogeneities and potential precipitation [13]. It is worth noting that such metallurgical features distinguish the SLM process from conventional ingot processing, where the liquid metal is poured into a mould and subsequently solidified by slower continuous cooling without repeated reheating.

Apart from the unique microstructures, the SLM process is still facing critical issues of material availability and limited mechanical properties. This is partly because the majority of existing alloys cannot be successfully printed due to intolerable cracks and/or micro cracks resulting from residual stress accumulation during the cyclic heating and cooling in the SLM process [14]. Aluminum alloys have been regarded as one of the most challenging materials for laser processing due to their high reflectivity, low melting point and more severely, their high susceptibility to hot tearing cracks [15]. As a consequence, most common Al alloys for SLM to date are still based on the near eutectic low performance Al-Si casting alloys, i.e. AlSi7Mg, AlSi10Mg, AlSi12 [8,16,17].

Thanks to the rapid solidification nature of the SLM process, unconventionally large amounts of slow diffusing transition metal and/or rare earth elements can now be placed into solid solution, which is not possible in the traditional ingot metallurgy processes [18]. For example, significant processability and mechanical property improvements have been achieved by introducing Sc into Al alloys for SLM fabrication [19]. Through alloying Sc into an Al-Zn-Mg based alloy, Zhou et al. [20] achieved crack-free samples with an equiaxed-columnar bimodal microstructure after SLM fabrication. The resultant mechanical properties are greatly improved after a normal T6 (solution + aging) heat treatment, with the yield strength reaching about 420 MPa [20]. By increasing the Sc content within the existing commercial Al-Mg-Sc based wrought alloys, ScalmalloyTM 1 was specifically developed for the SLM process [21]. Spierings et al. investigated such alloys in detail and found that the mechanical strength of this SLM fabricated Al—Mg—Sc alloy can be markedly improved by the formation of nano-sized Al3Sc precipitates after a direct aging treatment [22,23]. Further capturing the benefits offered by the rapid solidification rate of the SLM process, Jia et al. developed an Al-Mn-Sc based alloy where an unconventionally high amount of Mn addition led to an unprecedented yield strength of 570 MPa [24]. Due to the high solute partitioning coefficient and the high thermal stability of Mn, it was possible to place a large amount of Mn in solution during SLM, which further elevated the alloy strength via solid solution strengthening without sacrificing the benefits offered by Sc.

The addition of Sc into Al alloys for SLM fabrication has provided great opportunities for controlling the microstructures and improving the mechanical properties, thanks to the precipitation of the Al3Sc phase. To date, dedicated work has been put into investigating the microstructures and mechanical properties of Sc-containing SLM fabricated Al alloys via alloy composition, process parameter and post treatment optimisations [25–28]. However, few studies on the precipitation kinetics during post heat treatment have so far been reported for such alloys after SLM fabrication, despite the importance of obtaining such detailed knowledge for optimizing the mechanical properties. Previously, the precipitation behavior of the Al3Sc phase in Al alloys after conventional casting has been well explained [29–31]. However, as stated above, the rapid solidification rates and the spatially variable thermal histories of SLM processed materials contributed to the resultant complex microstructures, which differ significantly from those in the traditional casting process. Consequently, the precipitation behavior during post heat treatment after the SLM process are still not well known.

In this study, we present a detailed study on the precipitation kinetics of a SLM fabricated Al-Mn-Sc alloy that was specifically developed for the SLM process. In particular, we investigate the precipitation behavior for both the Al-Mn and Al-Sc phases simultaneously through the combined utilization of synchrotron-based in- situ X-ray scattering and diffraction, supplemented by ex-situ electron microscopy for microstructure characterization. The details of phase evolution, precipitation kinetics and mechanical property changes are systematically evaluated. The present study provides a fundamental understanding of the precipitation behavior after the dynamic SLM process, with the ultimate goal of contributing to future heat-treatable alloy design and property optimisations of SLM processed materials.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Sample preparation

Argon gas atomised powders with a composition of Al-4.52Mn-1.32Mg-0.79Sc-0.74Zr-0.05Si-0.07Fe (in wt%) were subjected to SLM fabrication. The SLM fabrication was conducted on a commercial EOS M290 machine, coupled with a 400-W fiber laser at a constant laser spot size of 100 μm. Following process parameter optimization, both cubic shaped (15 × 15 × 15 mm3) and hexagonal prism shaped (70 mm in length and 10 mm in diagonal) samples were built using a laser power of 370 W, laser scan speed of 1000 mm/s, hatch distance of 0.1 mm and a layer thickness of 0.03 mm. The above parameters guaranteed a fabricated sample density of above 99.5%. Post heat treatments for ex-situ experiments were performed in a salt bath with a temperature control of ± 2 °C.

2.2. In-situ synchrotron small angle X-ray scattering and X-ray diffraction

The in-situ ultra-small angle X-ray scattering (USAXS), small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) and X-ray diffraction (XRD) were conducted at the 9-ID-C beamline of the Advanced Photon Source (APS), Argonne National Laboratory [32]. The X-ray facility has an energy of 21 keV (X-ray wavelength of 0.5904 Å) with a corresponding flux density of 1013 photons/mm2/s. The combined use of USAXS and SAXS enabled the determination of precipitates with a continuous size range from subnm to several micrometres, and meanwhile, the coupled XRD allowed the evaluation of their crystal structure evolution. The scattering intensity of the USAXS data was calibrated on an absolute scale by utilizing the primary calibration capability of the Bonze-Hart type USAXS instrument, enabling a scattering vector (q) measurement range of 10−4 Å−1 to 0.2 Å−1. A beam size of 0.8 mm x 0.8 mm was used for the USAXS measurements. In the high q region, a PILATUS 100 K detector was supplemented by a conventional pin-hole SAXS geometry for better statistics and low scattering background. The SAXS measurements were conducted with a beam size of 0.8 mm x 0.2 mm, covering a q range of approximately 0.05–1.5 Å−1. Finally, the in-situ XRD measurements were conducted with a similar beam size to SAXS, measuring the q range from 1.4 Å−1 to 6.8 Å−1.

For the in-situ X-ray experiments, the as-fabricated cubic samples were sliced to 1 mm thickness via electrical discharge machining (EDM) wire cutting and then carefully polished to a surface finish of about 60 μm. For each set of experiments, the samples were heated to the target temperatures (300 °C, 350 °C, 400 °C and 450 °C in the present study) at a heating rate of 200 °C /min from room temperature. The above in-situ experiments were conducted in a repeated sequence of USAXS, SAXS and XRD, i.e. USAXS measurement for about 120 s, followed by SAXS measurement of 30 s and then XRD measurement of 30 s. Including motor motion and instrumental alignment, each sequence took approximately 5 min.

2.3. Microstructure characterization via ex-situ electron microscopy and atom probe

The grain microstructures of the SLM fabricated Al-Mn-Sc alloy were investigated by electron backscattered diffraction (EBSD), using an Oxford Nordlys Max2 detector in the JEOL 7001F FEG scanning electron microscope (SEM). Bright field (BF) TEM images were captured via an FEI Tecnai G2 T20 transmission electron microscope (TEM) operated at 200 kV. High angle annular dark field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM) images were collected in an aberration corrected FEI Titan G2 microscope operating at 300 kV, equipped with a Super-X detector for the energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) data collection. All the TEM samples in the present study were prepared by standard electrochemical polishing procedures.

The atom probe tomography (APT) was conducted on a Local Electrode Atom Probe (LEAP) Cameca 5000 XR with a pulse repetition rate of 200 kHz, a pulse fraction of 20% and a detection rate of 5 ions per 1000 pulses at a base temperature of 25 K. The needle-shaped APT sample tips were prepared by lift out using a Focused Ion Beam (FIB). The APT data reconstruction and analysis were carried out using IVAS 3.8.2 software. The nearest neighbor (NN) analysis was employed to reveal the solute distribution, and the maximum separation algorithm was applied to identify the clusters [33]. Based on the 3rd order nearest neighbor distribution, the largest deviation between the experimental and the random datasets was found at a dmax of 0.9. The minimum number of solute atoms per cluster was set to Nmin = 5, i.e. clusters containing smaller number of atoms than 5 were regarded as random distributions.

2.4. Property testing

The Vickers hardness measurements were performed on a Dura- min A300 hardness tester with a load of 500 g and a holding time of 10 s. The electrical conductivity (EC) of samples after different isothermal aging time intervals was measured using a Foerster SIGMA-TEST D 2.068 current device at room temperature. Tensile samples with a gauge length of 16 mm and a diameter of 4 mm were tested on a screw-driven Instron machine with a constant cross head moving speed of 0.48 mm/min. Three tensile samples were tested for each condition to assure its repeatability. The engineering stress- strain data were recorded through a 10 mm gauge extensometer until fracture.

3. Results

3.1. Microhardness and electrical conductivity

Fig. 1 shows the microhardness and electrical conductivity evolution of the SLM fabricated Al-Mn-Sc alloy upon isothermal aging treatment in the temperature range of 300–450 °C. Herein, microhardness has long been used to determine the mechanical response to aging condition, electrical conductivity measurements offer another indirect way to understand the precipitation process in Al alloys because it is highly sensitive to the chemical composition of the matrix. As expected, the precipitation kinetics become faster with increasing aging temperature (Fig. 1). The microhardness value increased from 140 HV0.5 in the as fabricated (AF) condition to the peak value of (186 ± 4) HV0.5 after aging for 300 min at 300 °C, and it then remained at a similar level for up to 1440 min (Fig. 1a). On the other hand, as shown in Fig. 1b, the electrical conductivity only showed very minor changes at 300 °C. Upon aging at 350 °C and 400 °C, the microhardness increased to peak values of about (183 ± 4) HV0.5 and (179 ± 6) HV0.5 at 60 min and 30 min, respectively. The measured maximum microhardness value reached (177±6) HV0.5 after aging for only 5 min at 450 °C, indicating the significantly stimulated precipitation kinetics at this temperature. With prolonged aging time, the hardness in the temperature range of 350–450 °C decreased continuously but more rapidly at the higher temperatures, reaching about 170 HV0.5, 152 HV0.5 and 120 HV0.5 after aging for 1440 min at 350 °C, 400 °C and 450 °C, respectively. During isothermal aging in the higher temperature range of 300–450 °C, the electrical conductivity increased significantly, implying higher temperature heat treatments accelerated the decomposition of solid solution to form precipitates. It is worth noting that the rate of increase of the electrical conductivity decreases after aging for 300 min at 400 °C, and similarly after aging for only 60 min at 450 °C. The transition occurs in the overaged condition at an electrical conductivity of 27–28% IACS (International Annealed Copper Standard), indicating a transition in the decomposition of the solid solution.

Fig. 1.

(a) Microhardness and (b) electrical conductivity evolutions of SLM fabricated Al—Mn—Sc alloy during isothermal aging at 300 °C, 350 °C, 400 °C and 450 °C.

3.2. Characterization of precipitate evolution via ex-situ TEM

The phase evolution of the SLM fabricated Al-Mn-Sc alloy during the studied heat treatments was investigated by ex-situ TEM. Typical aging treatments of 300 °C for 300 min, 350 °C for 360 min and 450 ° C for 360 min were selected in this study to compare the microstructure changes. The as-fabricated Al-Mn-Sc alloy showed a columnar-equiaxed bimodal grain microstructure, wherein short rod-shaped primary Al—Mn particles with lengths of approximately 20–300 nm and cuboidal shaped 20–50 nm primary Al3(Sc,Zr) particles were observed (see supplementary material Fig. S1). The Al Mn particles are mainly segregated along the intracrystalline dislocation walls and grain boundaries, while the Al3(Sc,Zr) particles are mainly located within the equiaxed grain regions [24]. Following the above-mentioned heat treatments at 350–450 °C, although the primary particles grow to different extents, only the newly formed secondary Al-Mn and Al-Sc precipitates were further captured in the studied samples. Careful comparison of SAED patterns (data not shown) revealed that newly formed secondary Al Mn and Al Sc precipitates remained their respective crystal structures within the above studied temperature and time ranges.

Fig. 2a, c, e show BF TEM images illustrating the Al-Mn phase evolution for different aging treatments. No significant changes can be observed for the short rod-shaped primary Al-Mn particles after aging at 300 °C for 300 min (Fig. 2a). Furthermore, dislocations formed during the SLM process are still observable after this heat treatment. Upon aging at 350 °C for 360 min, needle-shaped secondary Al-Mn precipitates were observed by TEM. Such precipitates had a typical size of 150 nm in length and 20 nm in width (Fig. 2c). After further aging at 450 °C for 360 min, the Al-Mn precipitates grow into a rectangular plate shape with significantly increased number density (Fig. 2e). Nano-beam diffraction (NBD) and SAED patterns revealed that Al-Mn particles formed after aging at 450 °C possessed a quasicrystalline approximant structure (Fig. 2g and Fig. S2). Further quantitative HAADF-STEM EDS analysis revealed that the Al—Mn particles have a stoichiometry corresponding approximately to Al6Mn (see supplementary material Fig. S3 and Table S1). Such a quasicrystalline approximant structure has been reported in a post heat treated Al-Pd-Cr alloy system [34].

Fig. 2.

(a), (c), (e) BF TEM pictures showing Al6Mn precipitates; (b), (d), (f) HAADF-STEM images showing Al3Sc precipitates. The corresponding heat treatments are 300 °C for 300 min in (a) and (b); 350 °C for 360 min in (c) and (d); 450 °C for 360 min in (e) and (f). A CBED pattern of a Al6Mn precipitate in (e) is shown in (g) revealing 5-fold symmetry. An FFT pattern of the Al3Sc precipitates in (f) is shown in (h).

Fig. 2b, d, f show HAADF STEM images illustrating the Al-Sc phase evolution as a function of aging time and temperature. As shown from the images taken along the <001>Al zone axis, the alternating dark and bright changes corresponding to the Al and Sc atom columns unequivocally confirmed the presence of L12 structured Al3Sc precipitates within the FCC structured Al matrix. No obvious core-shell structures corresponding to the Al3(Sc,Zr) precipitates can be observed. The Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) shown in Fig. 2h that corresponds to the sample aged at 450 °C for 360 min further demonstrates the superlattice reflection (as indicated by the arrow) of the Al3Sc precipitates. The Al3Sc precipitates generally exhibited a highly spherical shape and maintained a high coherency with the Al matrix after the studied heat treatments. The average precipitate size (in diameter) clearly increased after further heat treatment at higher temperatures and/or longer times, increasing from about 3 nm at 300 °C for 300 min to approximately 6 nm at 450 °C for 360 min.

3.3. In-situ USAXS study

Fig. 3 shows the complete sets of the reduced in-situ USAXS data of the SLM fabricated Al-Mn-Sc alloy during isothermal aging at 300 °C, 350 °C, 400 °C and 450 °C, respectively. The scattering curves are color coded on basis of the data acquisition time from the beginning of the experiment, following the scale represented by the color bars. In general, the USAXS spectrum exhibited a three-stage change feature on a log-log plot of intensity I vs. scattering vector q, i.e. with increasing q along the X-axis the scattering intensity firstly showed a decrement followed by a hump region, and then decreased following a power-law slope until reaching the final plateau where the signal reaches background level. Here, q = 4 π sin(θ)/ λ, where λ is the X-ray wavelength (0.5904 Å) and θ is one half of the scattering angle 2θ. Since the scattering vector is inversely proportional to the real space dimensions, the presence of low q scattering corresponds to scattering from the large (hundreds of nm) scattering inhomogeneities. In this case, this might originates from the grains, the primary Al6Mn and the primary Al3(Sc,Zr) phases as shown in Fig. S1.

Fig. 3.

In-situ USAXS data during isothermal aging at (a) 300 °C; (b) 350 °C; (c) 400 °C; (d) 450 °C. The color-coded scattering curves correspond to the acquisition times represented by the colored (in minutes) bars at the right side.(For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

No obvious scattering intensity changes over the q range between 10−4 Å−1 and 10−1 Å−1 were observed during isothermal aging at 300 °C for up to 300 min, indicating high thermal stability of the scattered large structures over this heat treatment regime. Under isothermal heat treatment at higher temperatures (350–450 °C), we observed a monotonic increase of the scattering intensity as a function of the measurement time, suggesting continuous growth of precipitates. The scattering intensity increased rapidly in the initial stages but then gradually slowed down after prolonged aging, as expected in a typical nucleation and growth event. Such an intensity increment is believed to be associated with the volume fraction increase of the scattering inhomogeneities [35]. The Guinier region near 0.001 Å−1 also exhibited a general shift towards lower q values with increasing aging time and temperatures, indicating a general size increase of the underlying scattering inhomogeneities. This could possibly be associated with the continued growth of the Al6Mn precipitates as con- firmed by the ex-situ TEM study in Fig. 2. The scattering intensity, on the other hand, gradually decreased after an initial increase over the q range of about 10−3–10−2 Å−1 during aging at 450 °C. This may be attributed to the continuous transformation of the initially formed small precipitates during in-situ aging into the larger structures through Ostwald ripening after prolonged measurement time [32].

3.4. In-situ SAXS study

The time-dependent in-situ SAXS data were collected subsequently after every USAXS measurement for the SLM fabricated Al-Mn-Sc alloy. The complete in-situ SAXS data sets measured over the temperature range of 300–450 °C are shown in Fig. 4. The general trend for the SAXS data evolution is that the scattering intensity over the q range of about 0.05–0.2 Å−1 increased monotonically as a function of aging time in the temperature range of 300–400 °C. Similar to the USAXS measurements, the rate of the increase of the scattering intensity was initially high and then gradually decreased after prolonged aging time.

Fig. 4.

In-situ SAXS data during isothermal aging at (a) 300 °C; (b) 350 °C; (c) 400 °C; (d) 450 °C. The color-coded scattering curves correspond to the acquisition times represented by the colored bars (in minutes) at the right side. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

During the in-situ SAXS test at 300 °C, the most noticeable intensity change was observed over the q range of about 0.1–0.2 Å−1. The scattering intensity of the two-dimensional SAXS data also showed no dependence on the azimuthal angle, indicating the isotropic nature of the detected precipitates. Upon aging at 350 °C and 400 °C, the intensity increase shifted towards the low q end, implying a size increase of the scattering structures. At 450 °C, the scattering intensity experienced a gradual decrease after an initial increase. Similar to the USAXS data at these temperatures, we suggest that the intensity changes here can be associated with precipitate coarsening through Ostwald ripening, except that these results capture changes in the smaller precipitates [32].

3.5. Structural evolution from the in-situ XRD study

Fig. 5a shows the representative XRD patterns measured in the as-fabricated condition as well as after in-situ heating for 300 min at the different temperatures. Apart from the strong diffraction peaks corresponding to the Al matrix, only a very minor peak (at q ≈ 2.9 Å−1) was observed in the as-fabricated condition. It is reasonable to conclude that such a secondary phase, although present in a very small volume fraction, has already formed during the SLM process. No obvious peak changes can be observed after aging for up to 300 min at 300 °C. Upon further aging at 350–450 °C, more diffraction peaks were captured, with the corresponding diffraction peak intensity increase with the aging temperature indicating an increase of the corresponding phase volume fraction. In this study, as mentioned above, the ex-situ TEM studies have confirmed that only two new phases (Al6Mn with a quasicrystal approximant structure and Al3Sc with an L12 structure) were detected after the studied heat treatment (Fig. 2). More importantly, they still maintained their respective original structures after the prolonged heat treatment. To identify such phases, we calculated the lattice spacings corresponding to the peak positions in the XRD spectrum and compared them with the known crystallographic lattice parameters and atomic positions from the International center for Diffraction Data database [36]. It is clear that diffraction peaks corresponding to the Al3Sc phase can be identified considering a slight peak shift induced by the thermal expansion at the elevated measurement temperatures. The other diffraction peaks can then be reasonably assigned to Al6Mn. This can be supported by the good lattice spacings matching based on the measurement of h ≈ 4.798 nm−1 distance (corresponding to 0.208 nm of D-spacings) in the NBD pattern (Fig. 2g) and the calculation from the diffraction peak at the position of q ≈ 3.02 Å−1 (calculated to be 0.208 nm of D-spacings) in the XRD pattern (Fig 5a).

Fig. 5.

(a) XRD patterns acquired at different process conditions for the SLM fabricated Al—Mn—Sc alloy. The purple vertical lines refer to the calculated peak positions for the Al3Sc phase. (b) A complete in-situ XRD dataset acquired during isothermal aging at 400 °C. The inset picture in (b) highlights the peak pointed out by the black arrow that corresponds to the Al6Mn phase.

Fig. 5b gives an example of a complete data set of the XRD patterns collected during in-situ heating at 400 °C. The measurement time is schematically indicated by the color coded arrow. The inset picture shows a magnification of one of the Al6Mn peaks. As expected, the Al6Mn peak intensity shows a monotonic increase with aging time, accompanied by a decrease of the FCC peaks. The intensity increased monotonically as a function of aging time from about 3 min to 600 min, indicating a gradual increase of the volume fraction of the detected Al6Mn phase. On the other hand, no obvious peak position shift was observed for all the detected phases upon in-situ heating at the above studied temperatures, suggesting that the formed phases maintained the same atomic structure.

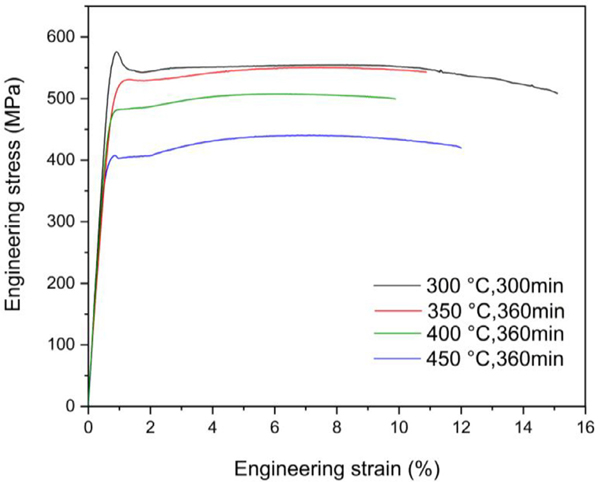

3.4. Mechanical property evolution

The mechanical properties of the SLM-fabricated Al-Mn-Sc alloy after the representative isothermal aging treatments were evaluated by tensile testing. Fig. 6 shows the resulting typical engineering stress–strain curves. To show the repeatability of the obtained results, the corresponding mechanical properties are summarised in Table 1. The yield strengths decreased gradually with increasing aging temperature and time, i.e. the alloy achieved a yield strength of 571 MPa after heat treatment at 300 °C for 300 min, and decreased to about 481 MPa and 399 MPa after aging for 360 min at 400 °C and 450 °C, respectively. Noticeably, the yield drop phenomenon detected in the heat-treated sample at 300 °C can be significantly alleviated upon further aging at higher temperatures. Herein, the discontinuous yielding followed by a long plateau is believed to be associated with Lüders band propagation, and such a phenomenon have been frequently observed in the Sc and/or Zr containing Al alloys after SLM fabrication [20,23,37,38]. Besides, as summarised in Table 1, the SLM fabricated Al-Mn-Sc alloy exhibited more obvious work hardening after aging at elevated temperatures. The underlying mechanisms for the above mechanical property evolutions will be discussed in the following section.

Fig. 6.

Typical engineering stress-strain curves for the SLM fabricated Al—Mn—Sc alloy after the representative heat treatments.

Table 1.

Tensile properties after the representative heat treatments of the SLM fabricated Al—Mn—Sc alloy. The errors represent the variations from the mean values.

| Heat treatment | Yield strength (MPa) | Tensile strength (MPa) | Elongation (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 300 °C, 300 min | 571 ± 4 | 573 ± 3 | 16 ± 1 |

| 350 °C, 360 min | 540 ± 10 | 558 ± 5 | 7 ± 3 |

| 400 °C, 360 min | 482 ± 3 | 513 ± 5 | 9 ± 1 |

| 450 °C, 360 min | 399 ± 3 | 440 ±1 | 13 ± 1 |

4. Discussion

4.1. Analysis of the Al6Mn phase evolution kinetics

The studied Al-Mn-Sc alloy was developed based on the utilization of the rapid solidification nature of the SLM process, in which unconventionally high amounts of Mn were placed into solution in the Al matrix [39]. The decomposition of this solid solution upon post heat treatment results in various changes of material properties, including mechanical properties and electrical conductivity. This has been demonstrated through monitoring the correlative evolutions of microhardness and electrical conductivity in this study. It is interesting to note that the electrical conductivity changes were dominated by the decomposition of Mn instead of Sc, indicating that the Mn atoms scatter valence electrons differently to Sc atoms (Fig. 1). One can then use electrical conductivity evolution as an index for the Mn solute decomposition during the post heat treatment. For instance, the electrical conductivity only showed minor changes after aging for 300 min at 300 °C, suggesting that Mn-related precipitation was not effectively activated in this condition. This can be further supported by the TEM and in-situ XRD studies where no obvious secondary Mn phase precipitation or associated XRD peaks were observed. Upon further testing at higher temperatures (350–450 °C), the electrical conductivity increased significantly, and the precipitation of a high number density of Al6Mn particles was revealed by TEM studies (Fig. 2). Moreover, diffraction peak changes of the Al6Mn phase were also captured by in-situ XRD measurement at such temperatures (Fig. 5a and 5b).

To evaluate the Al6Mn phase evolution kinetics, the in-situ high resolution XRD data were utilised as it provides a useful tool for monitoring the specific phase changes. The XRD peak intensity was normalised with incident flux for each measurement so as to eliminate the influence of the X-ray intensity variation at different measurement [40]. As highlighted in the inset picture in Fig. 5b, we selected one of the diffraction peaks at q ≈ 2.815 Å−1 that corresponds to the Al6Mn phase for further analysis. It is worth noting that while no obvious peak center changes were observed along the whole measurement time regime, the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of this peak did show a continuous decrease with prolonged aging time (see supplementary material Fig. S4). This suggests that the lattice parameter of the Al6Mn phase is stable during the measurement while the precipitate is indeed growing [41]. We then integrated the time-dependent XRD peak intensity (all at the peak position of q ≈ 2.815) of the samples measured at 350 °C, 400 °C and 450 °C, respectively (Fig. 7). The integrated peak intensity can be used as an indication for the phase precipitation and growth, where the continuous evolution of the intensities is associated with the phase evolution kinetics. The integrated peak intensity growth demonstrated a strong dependence on the testing temperature, i.e. higher temperatures lead to faster intensity growth and shorter times to reach steady state.

Fig. 7.

Evolution of the integrated XRD peak intensities during isothermal aging at 350 °C, 400 °C and 450 °C. The integrated peak position at q ≈ 2.815 A−1 corresponds to the Al6Mn phase. The black curves represent fitting using the exponential decay function.

To determine the kinetic rates, the integrated peak intensity evolution was then modelled as a function of the aging time by using a simple exponential-decay function:

| (1) |

where t is the heating time and k is a temperature dependent rate. The least-square fits that are represented by the solid black lines captured the observed kinetics well (Fig. 7). The fitting parameters for different temperatures are summarised in Table 2. On the basis of the achieved temperature-dependent kinetic rates, as shown in Fig. 8, an Arrhenius analysis was then performed. The activation energy for the growth of the Al6Mn phase is extracted for the SLM fabricated Al-Mn-Sc alloy, which is determined to be (74 ± 4) kJ/mol ((0.76 ± 0.04) eV/atom). The calculated activation energy is noted to be significantly lower than the activation energy for lattice diffusion of Mn in Al matrix (211.5 kJ/mol), suggesting that the growth of Al6Mn precipitates is not governed by long-range volume diffusion [42]. Furthermore, it is worth noting that the calculated activation energy is also much lower than that of the plasma sprayed (1.33 eV/atom) Al-2.9Mn (wt%) alloys over a similar testing temperature regime [43]. One possible reason might be the higher concentration of the supersaturated Mn in solid solution in the current Al-Mn-Sc alloy, leading to a more pronounced decomposition of Mn for nucleation and growth. On the other hand, the dislocations introduced during the SLM process and the large area fraction of refined grain boundaries, can all work as faster diffusion channels to contribute to the rapid diffusion and growth of the Al6Mn phase upon post heat treatment [44].

Table 2.

The Al6Mn precipitates growth parameters during isothermal aging at different temperatures.

| Temperature (°C) | I0 (× 103) | K (min−1) (× 103) |

|---|---|---|

| 350 °C | 1.42 ± 0.01 | 2.95 ± 0.03 |

| 400 °C | 2.08 ± 0.01 | 9.3 ± 0.2 |

| 450 °C | 4.71 ± 0.02 | 21 ± 12 |

Fig. 8.

Arrhenius analysis for the Al6Mn phase growth kinetics.

4.2. Al3Sc nucleation and growth kinetics

The decomposition of the supersaturated Sc in solution can form a large number density of nano-sized Al3Sc precipitates upon post heat treatment, giving significant precipitation strengthening to the base alloy [45]. As shown in Fig. 1a, the microhardness of the SLM fabricated Al—Mn—Sc alloy increased from 140 HV0.5 in the as-fabricated condition to 187 HV0.5 after heat treatment at 300 °C for 300 min. The HAADF-STEM study revealed the formation of L12 structured Al3Sc precipitates with an absence of other precipitates (Fig. 2). Indeed, by using atom probe tomography (APT), our previous study demonstrated that the dissolved Sc solutes precipitated out while other solutes remained in solution after the above heat treatment [24].

The precipitation of the Al3Sc phase was successfully captured by in-situ SAXS, where the scattering intensity clearly changed during the isothermal heating at 300 °C (Fig. 4a). To elucidate the evolution kinetics of the Al3Sc precipitates, detailed SAXS data reduction and analyses were conducted with the small angle scattering analysis software of Irena in the Igor Pro-environment [46]. In this study, given the small precipitate size (approximately 3 nm) evidenced from the above HAADF STEM study, it is reasonable to assume that the formed Al3Sc precipitates possessed a spherical shape (Fig. 2). We then constructed a scattering model to interpret the SAXS data based on the above assumption. Fig. 9 shows an illustration of the developed model, where the last set of the in-situ SAXS data that was acquired after isothermal aging for 300 min at 300 °C is given as an example. The scattering baseline was acquired for the same sample before the in-situ heating and it was assumed to be consistent across the entire isothermal aging study. The excess scattering that was derived by subtracting the scattering baseline from the real-time scattering was then attributed to the nucleation and growth of the Al3Sc precipitates. The time-evolution of size and volume fraction of the Al3Sc precipitates was then extracted from all the in-situ SAXS datasets acquired at 300 °C on the basis of the above model analysis (Fig. 10). After aging for 300 min at 300 °C, the Al3Sc precipitate size reached an average value of about 3 nm and a volume fraction of approximately 1.7%, both of which are in good agreement with the HAADF-STEM study and the previous APT study [24]. This demonstrates the validity and the capability of the model.

Fig. 9.

An illustration of the SAXS model used in the data analysis. The data selected was acquired after aging at 300 °C for 300 min. The excess scattering is obtained by subtracting the scattering baseline from the acquired data.

Fig. 10.

The time-dependent (a) diameter and (b) volume fraction evolutions of the Al3Sc precipitates during aging at 300 °C.

As shown in Fig. 10a and 10b, the first noticeable phenomenon observed is that the diameter of the Al3Sc precipitates experienced an initial rapid growth from about 1.5 nm at 4 min to 2.5 nm at 14 min. Interestingly, the volume fraction experienced a similar rapid growth trend. After dividing the volume fraction by the average precipitate volume at each data acquisition time, it is not difficult to find that the precipitate number density exhibited inconspicuous changes in this short aging period. Nevertheless, one should still bear in mind that it is possible that nucleation might have already been activated by this stage, although the precipitates are possibly too small to be captured due to limitations in the signal-to-noise ratio in the SAXS setup. To our surprise, further aging from 14 min to 50 min revealed that the volume fraction of the Al3Sc precipitates increased rapidly, while the average precipitates diameter only experienced negligible changes. As a consequence, the Al3Sc precipitate number density must be increased. Thus, it is not difficult to deduce that the newly nucleated Al3Sc precipitates affected the overall average precipitate size, but they must have grown to a certain size that can be effectively captured by SAXS in the present study. With further prolonged aging time, the precipitate size and volume fraction increased simultaneously, indicating that precipitate growth dominated this stage.

For solid-state precipitation in a traditional solution treated alloy, the precipitate number density normally experiences a significant increase once the nucleation barrier is overcome upon artificial aging treatment [47]. In this study, the nucleation of Al3Sc precipitates experienced a pseudo-delay evolvement, with the precipitate number density remaining constant initially and then increasing rapidly before the steady-state growth stage. Such nucleation behavior distinguishes the precipitation of SLM processed Sc containing Al alloys from the continuous precipitation in conventional ingot metallurgy [47]. To unveil the underlying reason for the above unconventional precipitation phenomenon, we further investigated the microstructures in the as-SLM fabricated Al-Mn-Sc alloy by APT. The 3rd order nearest neighbor Sc solute atom distance curves from the experimental and the corresponding reference random datasets are shown in Fig. 11a. The deviations between the experimental and the random curves reveal a non-random distributions of Sc solute atoms. In other words, a Sc-rich clustering tendency is exhibited in the as SLM fabricated condition. Based on the nearest neighbor distribution algorithms (see methods), the 3D distribution of the reconstructed Sc-rich (and ScH2 resulting from artefacts) clusters in the as-fabricated condition are shown in Fig. 11b. As stated earlier, during the layer-by-layer material deposition in the SLM process, the heat input will introduce an intrinsic heat treatment effect to the adjacent scan tracks and the previously solidified layers [13,48]. This triggers the diffusion of Sc atoms through the lattice, accelerated by vacancies introduced by the rapid solidification rate of the SLM process, and leading to the formation of small Sc-rich clusters. Herein, we hypothesize that the preformed clusters change the nucleation procedure observed in the present study. Upon post heat treatment, the preformed Sc-rich clusters act as precursors for further precipitate growth through the diffusion of Sc, which facilitates the concurrent increase in precipitates size and volume fraction during the initial stage. On the other hand, the Sc atoms remaining in solid solution still need to overcome an activation energy barrier for precipitate nucleation, although the excess vacancies, dislocations and grain boundaries introduced during the SLM process are expected to help reduce such barrier [49]. The dynamic evolution of these precipitates that form due to different precipitation mechanisms determines the average precipitate size and volume fraction evolution that is captured by the in-situ SAXS (bearing in mind the technique resolution).

Fig. 11.

(a) A 3NN histogram analysis revealing the deviation between experimental and the random distributions of Sc atoms in the as-SLM fabricated condition; (b) 3D APT reconstruction showing the Sc-rich (and ScH2 caused by artefact) clusters.

The Al3Sc precipitate growth kinetics were also investigated by integrating the diffraction peaks at q ≈ 3.41 Å−1 that correspond to this phase based on the simultaneously achieved in-situ XRD data. By utilizing the methodology described in Section 4.1, the temperature dependent growth kinetics for the Al3Sc precipitates can be determined (see supplementary material Fig. S5 and Table S2). The Arrhenius analysis revealed an activation energy of (63 ± 9) kJ/mol, which converts to about (0.65 ± 0.09) eV/atom for the Al3Sc precipitates. This value is significantly lower than the activation energy required for Sc lattice diffusion in the Al matrix, which is determined to be about 173 kJ/mol [50]. Compared with the larger barrier for the long-range volume diffusion of Sc in Al, the solute mobility can be markedly accelerated by the lattice defects introduced by the SLM process, such as vacancies, dislocations and fine grain boundaries [49]. Furthermore, it is believed that the intrinsically formed Sc-rich clusters act as precursors for precipitate growth, leading to the significantly reduced energy requirements for Al3Sc precipitates growth.

The intrinsic heat treatment induced clusters can be regarded as a unique feature of the track-by-track and layer-by-layer SLM building process [13,24,48]. It is expected that the dynamic precipitation of such clusters can be tuned by changing the process control, including laser parameters, scan strategies and substrate temperatures. As a consequence, larger number density and more uniform distributions of such preformed clusters can be potentially achieved to strengthen the SLM synthesised alloy without a further post heat treatment. This will be further investigated in future.

4.3. Precipitate evolution effect on mechanical properties

The tensile testing curves exhibited an obvious yield strength decrease upon increasing the aging treatment temperature and time (Fig. 6). For the SLM fabricated Al-Mn-Sc alloy, it is believed that grain boundary strengthening, precipitation hardening (mainly from Al3Sc precipitates) and solid solution strengthening (mainly from Mn and Mg solutes) are the dominant strengthening mechanisms [24]. The grain structures were evaluated by EBSD after isothermal aging treatment at 300 °C for 300 min, 350 °C for 360 min and 450 °C for 360 min. As can be seen from Fig. 12, the SLM-fabricated Al-Mn-Sc alloy maintained the columnar-equiaxed bimodal microstructures, with no obvious recrystallization or grain coarsening after the various aging treatments. By zooming into the ultrafine grain areas, the statistics from more than 1000 grains show that the average grain size hardly changed across the above heat treatment regime (Fig. 12d). We suggest that the high thermal stability of the grain structure can be attributed to the thermally stable Al6Mn and Al3Sc particles, which act as strong grain growth inhibitors to avoid recrystallization and/or grain growth [51]. On this basis, possible contributions from grain size changes to yield strength variations can be ruled out. During aging at the higher temperatures of 350 °C and 450 °C, HAADF-STEM studies confirmed the growth of Al3Sc precipitates and the concurrently decreasing number density. The effective obstacles in the spatial distribution are thereby reduced to effectively impede dislocation movement. On the other hand, the decomposition of the Mn-rich solid solution released the local lattice strain field induced by the solid solution, thereby making it easier for dislocations to move [52]. Thus, the yield strength decrease upon aging at higher temperatures can be attributed to the decomposition of the Mn-rich solid solution and to the coarsening of the Al3Sc precipitates.

Fig. 12.

EBSD images showing the grain size distributions of the SLM-fabricated Al—Mn—Sc alloy after aging at (a) 300 °C for 300 min; (b) 350 °C for 360 min; (c) 450 °C for 360 min. (d) The selected fine equiaxed grain size distribution from more than 1000 grains for different process conditions.

Another noticeable mechanical behavior change is that the yield drop phenomenon can be significantly alleviated upon heat treatment at higher temperatures. A discontinuous yielding phenomenon has been frequently reported in the Sc and/or Zr modified Al alloys after SLM fabrication, and in each case the common feature of ultrafine grains was observed [19,22,36,37]. A previous study showed that the discontinuous yielding become more distinct as the grain size is reduced to the submicron level [53]. The underlying reason was attributed to the lack of mobile dislocations as the ultrafine grain boundary areas stimulated the dynamic recovery rate by promoting dislocation annihilation [53,54]. In the present study, the ultrafine equiaxed grains still maintained their distribution and size in the sub-micrometer regime after the higher temperature heat treatments as compared to those at 300 °C for 300 min (Fig. 12). To elucidate the underlying mechanisms, we conducted further TEM studies on fractured tensile test samples. Fig. 13a and 13b show the dislocation distribution for the sample heat treated at 300 °C for 300 min and 350 °C for 360 min, respectively. The dislocations showed uniform distributions in the heat-treated condition at 300 °C. On the contrary, dislocations accumulated around the long needle-shaped Al6Mn precipitates (as pointed out by the red arrows) for the 350 °C heat treated samples. With the decomposition of the Mn-rich solid solution, it is believed that dislocation cores being impeded by the solute atoms can move more freely, and meanwhile contributing to the nucleation of more mobile dislocations upon deformation. The resulting increase in the mobile dislocation densities can on the one hand compensate the rapid dynamic recovery of dislocations at the ultrafine grain boundaries. On the other hand, due to the non-shearable Al6Mn precipitates, geometrically necessary dislocations can be effectively stored during material deformation, which reduces the dislocation annihilation rate and simultaneously improves the work hardening [55,56]. Indeed, introducing such non-shearable precipitates might be one effective way to alleviate the discontinuous yielding caused by the formation of ultrafine grains. Moreover, the utilization of shearable and non- shearable precipitates with controllable distribution and geometry in engineering materials is also expected to provide good combinations of both strength and fracture toughness [57]. This can be considered for future alloy design of SLM fabricated Sc and/or Zr containing Al alloys.

Fig. 13.

BF TEM images from gauge section of fractured samples showing (a) uniform distribution of dislocations and (b) the needle-shaped Al6Mn particles blocking dislocations. The tensile samples were aged at 300 °C for 300 min in (a) and 350 °C for 360 min in (b) before tensile testing.

5. Conclusions

This study presents findings about the precipitation kinetics and the role of precipitation on the final mechanical properties of an SLM fabricated Al-Mn-Sc alloy. The following main conclusions can be drawn:

The precipitation of the Al3Sc phase markedly improved the hardness and strength during the aging treatment at 300 °C, while the decomposition of the Mn-rich solid solution significantly improved the electrical conductivity in the aging temperature range of 350–450 °C. This led to the formation of an Al6Mn phase in the SLM fabricated Al—Mn—Sc alloy. HAADF STEM studies revealed the presence of L12 structured Al3Sc precipitates, the average size of which increased from 3 nm after 300 min at 300 ° C to approximately 6 nm after 360 min at 450 °C.

The evolution of the Al3Sc precipitates during aging at 300 °C was successfully captured by the in-situ SAXS study, from which the time-evolutions of the Al3Sc precipitates size and volume fraction were extracted based on a constructed model. The Al3Sc precipitates exhibited a pseudo-delay nucleation behavior, which was found to be due to the presence of Sc clusters in the as SLM fabricated Al-Mn-Sc alloy. This precipitation behavior of the SLM processed Sc containing Al alloy is distinctly different from conventional ingot metallurgy.

The temperature-dependent growth kinetics for the precipitation and growth of the Al6Mn and Al3Sc phases were established on the basis of in-situ X-ray studies. The respective activation energies were determined to be (74 ± 4) kJ/mol and (63 ± 9) kJ/mol, both of which are significantly lower than the corresponding activation energies for long-range volume diffusion of Mn and Sc atoms in the Al lattice. It is believed that the unique microstructural features of the SLM processed Al-Mn-Sc alloy, including excess vacancies, high density of dislocations, ultrafine grain structure and the preformed clusters, all accelerated the diffusion rate and/or contributed to the rapid precipitation and growth of the respective phases.

The precipitation and evolution of the Al6Mn and Al3Sc phases significantly influenced the final mechanical properties. The bimodal columnar-equiaxed grain structure in the as SLM fabricated condition was maintained even after aging at 450 °C due to the high thermal stability and strong grain growth inhibition capability of the Al6Mn and Al3Sc phases. By increasing the aging temperature, although the yield strength decreased, the discontinuous yielding phenomenon was found to be alleviated due to the loss of Mn from solution resulting in the formation of non- shearable Al6Mn particles.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by the Australian Research Council grant IH130100008 “Industrial Transformation Research Hub for Transforming Australia’s Manufacturing Industry through High Value Additive Manufacturing”. The authors acknowledge use of the facilities at the Monash Centre for Additive Manufacturing (MCAM) and the Monash Centre for Electron Microscopy (MCEM). Use of the Advanced Photon Source, an Office of Science User Facility operated for the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory, was supported by the U.S. DOE under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357. The authors thank P. Kuünrnsteiner for assistance with the preliminary APT analysis work. M.L. Sui thanks the financial support from the National Natural Science Fund for Innovative Research Groups (Grant No. 51621003) and Beijing municipal Found for Scientific Innovation (PXM2019_014204_500031).

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Supplementary materials

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.actamat.2020.04.015.

Certain commercial equipment, instruments, software or materials are identified in this paper to foster understanding. Such identification does not imply recommendation or endorsement by the Department of Commerce or the National Institute of Standards and Technology, nor does it imply that the materials or equipment identified are necessarily the best available for the purpose.

References

- [1].Herzog D, Seyda V, Wycisk E, Emmelmann C, Additive manufacturing of metals, Acta Mater. 117 (2016) 371–392. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Chapter 14 inedited by Rometsch P, Jia Q, Yang KV, Wu X, Aluminum alloys for selective laser melting-towards improved performance. Chapter 14 in in: Froes Francis H., Boyer Rod (Eds.), Additive Manufacturing for the Aerospace Industry, Elsevier, 2019. edited by. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Yap CY, Chua CK, Dong ZL, Liu ZH, Zhang DQ, Loh LE, Sing SL, Review of selective laser melting: materials and applications, Appl. Phys. Rev. 041101 (2015) 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Gasser A, Backes G, Kelbassa I, Weisheit A, Wissenbach K, Laser metal deposition (LMD) and selective laser melting (SLM) in turbo-engine applications, Laser Tech. J. 2 (2010) 58–63. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Bose S, Ke DX, Sahasrabudhe H, Bandyopadhyay A, Additive manufacturing of biomaterials, Prog. Mater. Sci. 93 (2018) 45–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Lewandowski JJ, Seifi M, Metal additive manufacturing: a review of mechanical properties, Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 46 (2016) 152–186. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Gorsse S, Hutchinson C, Goune M´, Banerjee R, Additive manufacturing of metals: a brief review of the characteristic microstructures and properties of steels, Ti-6Al-4V and high-entropy alloys, Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 18 (2017) 584–610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Thijs L, Kempen K, Kruth JP, Humbeeck JV, Fine-structured aluminium products with controllable texture by selective laser melting of pre-alloyed AlSi10Mg powder, Acta Mater. 61 (2013) 1809–1819. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Wang YM, Voisin T, McKeown JT, Ye J, Calta NP, Li Z, Zeng Z, Zhang Y, Chen W, Roehling TT, Ott RT, Additively manufactured hierarchical stainless steels with high strength and ductility, Nat. Mater. 17 (2018) 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Zhu ZG, Nguyen QB, Ng FL, An XH, Liao XZ, Liaw PK, Nai SML, Wei J, Hierarchical microstructure and strengthening mechanisms of a CoCrFeNiMn high entropy alloy additively manufactured by selective laser melting, Scr. Mater. 154 (2018) 20–24. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Prashanth KG, Eckert J, Formation of metastable cellular microstructures in selective laser melted alloys, J. Alloy Compd. 707 (2017) 27–34. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Liu LF, Ding QQ, Zhong Y, Zou J, Wu J, Chiu YL, Li JX, Zhang Z, Yu Q, Shen ZJ, Dislocation network in additive manufactured steel breaks strength-ductility trade-off, Mater. Today 21 (2018) 354–361. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Kürnsteiner P, Wilms MB, Weisheit A, Barriobero-Vila P, Jägle EA, Raabe D, Massive nanoprecipitation in a Fe 19Ni xAl maraging steel triggered by the intrinsic heat treatment during laser metal deposition, Acta Mater. 129 (2017) 52–60. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Johnson L, Mahmoudi M, Zhang B, Seede R, Huang XQ, Maier JT, Maier HJ, Karaman I, Elwany A, Arróyave R, Assessing printability maps in additive manufacturing of metal alloys, Acta Mater. 176 (2019) 199–210. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Olakanmi EO, Cochrane RF, Dalgarno KW, A review on selective laser sintering/melting (SLS/SLM) of aluminium alloy powders: processing, microstructure, and properties, Prog. Mater. Sci. 74 (2015) 401–477. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Li XP, Wang XJ, Saunders M, Suvorova A, Zhang LC, Liu YJ, Fang MH, Huang ZH, Sercombe TB, A selective laser melting and solution heat treatment refined Al-12Si alloy with a controllable ultrafine eutectic microstructure and 25% tensile ductility, Acta Mater. 95 (2015) 74–82. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Rao H, Giet S, Yang K, Wu X, Davies C, The influence of processing parameters on aluminium alloy A357 manufactured by selective laser melting, Mater. Des. 109 (2016) 334–346. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Jia Q, Rometsch P, Cao S, Zhang K, Huang A, Wu X, Characterisation of AlScZr and AlErZr alloys processed by rapid laser melting, Scr. Mater. 151 (2018) 42–46. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Koutny D, Skulina D, Pantělejev L, Paloušek D, Lenczowski B, Palm F, Nick A, Processing of Al Sc aluminum alloy using SLM technology, Proc. CIRP 74 (2018) 44–48. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Zhou L, Pan H, Hyer H, Park S, Bai Y, McWilliams B, Cho K, Sohn Y, Microstructure and tensile property of a novel AlZnMgScZr alloy additively manufactured by gas atomization and laser powder bed fusion, Scr. Mater. 158 (2019) 24–28. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Palm F, Schmidtke K, Exceptional grain refinement in directly built up Sc-modified AlMg alloys is promising a quantum leap in ultimate light weight design, in: Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Trends in Welding Research 2012, 108, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Spierings AB, Dawson K, Heeling T, Uggowitzer PJ, Schäublin R, Palm F, Wegener K, Microstructural features of Sc- and Zr-modified Al-Mg alloys processed by selective laser melting, Mater. Des. 115 (2017) 52–63. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Spierings AB, Dawson K, Kern K, Palm F, Wegener K, SLM-processed Sc- and Zr- modified Al Mg alloy: mechanical properties and microstructural effects of heat treatment, Mat. Sci. Eng. A 701 (2017) 264–273. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Jia Q, Rometsch P, Kürnsteiner P, Chao Q, Huang A, Weyland M, Bourgeois L, Wu X, Selective laser melting of a high strength Al-Mn-Sc alloy: alloy design and strengthening mechanism, Acta Mater. 171 (2019) 108–118. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Li RD, Wang MB, Yuan TC, Song B, Chen C, Zhou KC, Cao P, Selective laser melting of a novel Sc and Zr modified Al-6.2Mg alloy: processing, microstructure, and properties, Powder Technol. 319 (2017) 117–128. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Awd M, Tenkamp J, Hirtler M, Siddique S, Bambach M, Walther F, Comparison of microstructure and mechanical properties of scalmalloy® produced by selective laser melting and laser metal deposition, Materials (Basel) 11 (2018) 1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Li RD, Chen H, Zhu HB, Wang MB, Chen C, Yuan TC, Effect of aging treatment on the microstructure and mechanical properties of Al-3.02-Mg-0.2Sc-0.1Zr alloy printed by selective laser melting, Mater. Des. 168 (2019) 107668. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Spierings AB, Dawson K, Uggowitzer PJ, Wegener K, Influence of SLM scan-speed on microstructure, precipitation of Al3Sc particles and mechanical properties in Sc- and Zr-modified Al-Mg alloys, Mater. Des. 140 (2018) 134–143. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Taendl J, Orthacker A, Amenitsch H, Kothleitner G, Poletti C, Influence of the degree of scandium supersaturation on the precipitation kinetics of rapidly solidified Al-Mg-Sc-Zr alloys, Acta Mater. 117 (2016) 43–50. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Clouet E, Lae L, Epicier T, Lefebvre W, Nastar M, Deschamps A, Complex precipitation pathways in multi-component alloys, Nat. Mater. 5 (2006) 482–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Clouet E, Barbu A, Using cluster dynamics to model electrical resistivity measurements in precipitating AlSc alloys, Acta Mater. 55 (2007) 391–400. [Google Scholar]

- [32].Ilavsky J, Zhang F, Andrews RN, Serio J, Kuzmenko I, Jemian PR, Levine LE, Allen AJ, Development of combined microstructure and structure characterization facility for in situ and operando studies at the advanced photon source, J. Appl. Cryst. 51 (2018) 867–882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Cerezo A, Davin L, Aspects of the observation of clusters in the 3-dimensional atom probe, Surf. Interface Anal. 39 (2017) 184–188. [Google Scholar]

- [34].Sun W, Yubuta K, Hiraga K, The crystal structure of a new crystalline phase in the Al-Pd-Cr alloy system, studied by high resolution electron microscopy, Phil. Mag. B 71 (1995) 71–80. [Google Scholar]

- [35].Deschamps A, Militzer M, Precipitation kinetics and strengthening of a Fe-0.8 wt% Cu alloy, ISIJ Int. 41 (2001) 196–205. [Google Scholar]

- [36].Belsky A, Hellenbrandt M, Karen VL, Luksch P, New developments in the inorganic crystal structure database (ICSD): accessibility in support of materials research and design, Acta Cryst. Sect. B Struct. Sci. 58 (2002) 364–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Zhang H, Zhu H, Nie X, Yin J, Hu Z, Zeng X, Effect of zirconium addition on crack, microstructure and mechanical behavior of selective laser melted Al Cu Mg alloy, Scr. Mater. 134 (2017) 6–10. [Google Scholar]

- [38].Holden Hyer Le Zhou, Park S, Pan H, Bai Y, Katherine P R, Yongho S, Microstructure and mechanical properties of Zr-modified aluminum alloy 5083 manufactured by laser powder bed fusion, Addit. Manuf. 28 (2019) 485–496. [Google Scholar]

- [39].Jia Q, Rometsch P, Cao S, Zhang K, Wu X, Towards a high strength aluminium alloy development methodology for selective laser melting, Mater. Des. 174 (2019) 107775. [Google Scholar]

- [40].Shenoy G, Viccaro P, Mills DM, Characteristics of the 7-GeV Advanced Photon Source: a Guide for Users, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- [41].Zhang F, Levine LE, Allen AJ, Campbell CE, Creuziger AA, Kazantseva N, Ilavsky J, In situ structural characterization of ageing kinetics in aluminium alloy 2024 across angstrom-to-micrometer length scales, Acta Mater. 111 (2016) 385–398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Liebermann A, Rapidly Solidified Alloys: Processes-Structures-Properties-Applications, CRC Press, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- [43].Karnowsky MM, Moss M, Stein C, The activation energy for the precipitation of Al6Mn in plasma-sprayed Al-2.9wt% Mn alloy, Scr. Metall. 8 (1974) 513–518. [Google Scholar]

- [44].Shechtman D, Jo Schaefer R, Biancaniello FS, Precipitation in rapidly solidified Al-Mn alloys, Metall. Trans. A 15 (1984) 1987–1997. [Google Scholar]

- [45].Røyset J, Ryum N, Scandium in aluminium alloys, Int. Mater. Rev. 50 (2005) 19–44. [Google Scholar]

- [46].Ilavsky J, Jemian PR, Irena: tool suite for modeling and analysis of small angle scattering, J. Appl. Cryst. 42 (2009) 347–353. [Google Scholar]

- [47].Porter DA, Easterling KE, Sherif MY, Phase Transformations in Metals and Alloys, 3rd Edition, CRC Press, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- [48].Jägle EA, Sheng Z, Wu L, Lu L, Risse J, Weisheit A, Raabe D, Precipitation reactions in age-hardenable alloys during laser additive manufacturing, JOM 68 (2016) 943–949. [Google Scholar]

- [49].Novotny GM, Ardell AJ, Precipitation of Al3Sc in binary Al-Sc alloys, Mater. Sci. Eng. A 318 (2001) 144–154. [Google Scholar]

- [50].Marquis EA, Seidman DN, Nanoscale structural evolution of Al3Sc precipitates in Al(Sc) alloys, Acta Mater. 49 (2001) 1909–1919. [Google Scholar]

- [51].Vlach M, Stulíková I, Smola B, Kekule T, Kudrnová H, Danis S, Gemma R, Ocenasek V, Málek J, Tanprayoon D, Neubert V, Precipitation in cold-rolled Al-Sc-Zr and Al-Mn-Sc-Zr alloys prepared by powder metallurgy, Mater. Char. 86 (2013) 59–68. [Google Scholar]

- [52].Varvenne C, Leyson GPM, Ghazisaeidi M, Curtin WA, Solute strengthening in random alloys, Acta Mater. 124 (2017) 660–683. [Google Scholar]

- [53].Yu CY, Kao PW, Chang CP, Transition of tensile deformation behaviors in ultrafine-grained aluminium, Acta Mater. 53 (2005) 4019–4028. [Google Scholar]

- [54].Wang YM, Ma E, Strain hardening, strain rate sensitivity, and ductility of nanostructured metals, Mat. Sci. Eng. A 375-377 (2004) 46–52. [Google Scholar]

- [55].Zhao YH, Liao XZ, Cheng S, Ma E, Zhu YT, Simultaneously increasing the ductility and strength of nanostructured alloys, Adv. Mater. 18 (2006) 2280–2283. [Google Scholar]

- [56].Cheng S, Zhao YH, Zhu YT, Ma E, Optimizing the strength and ductility of fine structured 2024 Al alloy by nano-precipitation, Acta Mater. 55 (2007) 5822–5832. [Google Scholar]

- [57].da Costa Teixeira J, Bourgeois L, Sinclair C, Hutchinson C, The effect of shear-resistant, plate-shaped precipitates on the work hardening of Al alloys: towards a prediction of the strength-elongation correlation, Acta Mater. 57 (2009) 6075–6089. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.